Abstract

The role of marginal areas in the dynamic relations between mobile and sedentary groups in Early Bronze Age Levant is examined through the site cluster of Mitzpe Shalem. This morphologically anomalous cluster was discovered and excavated more than 50 years ago, yet its function has not been subject to rigorous archaeological analysis. A holistic reconsideration of various aspects of the site cluster, including its geographic situation, morphology and artifact distributions, suggests an inter-cultural engagement centre with ties to multiple socio-cultural spheres. An integrative analysis of the remains indicates that encounters at the cluster were oriented around a transformative ritual performance.

Introduction

The study of regionalism and connectivity in the Levantine Early Bronze Age (EBA) usually revolves around comparative analysis of settlement patterns and material-cultural trajectories within and between regions (e.g., Getzov et al. Citation2001; Greenberg Citation2002; Harrison Citation1997; Paz Citation2003; Philip Citation2001; Portugali and Gophna Citation1993; Rast Citation2001; Yekutiei Citation2000). This type of regional archaeology stems directly from the nature of archaeological data produced in the settled zones of the southern Levant, which derive from excavations of deeply stratified sites, supplemented by the results of regional settlement surveys. Marginal areas, less favourable for sustaining large permanent populations, may provide a very different perspective on EBA connectivity. In these regions, profusion of task-specific and (often) chronologically constrained sites may facilitate investigation of aspects related to mobility, cultural exchange and inter-regional encounters (Philip Citation2003; Yekutieli Citation2004a).

The Judean Desert, a local arid region in the rain shadow of the Cis-Jordanian Highlands, has often been viewed as an inaccessible and inhospitable region, offering archaeologists only rare and ostensibly miraculous discoveries of ‘treasures’ in remote caves. Yet, recent investigations have unearthed data indicative of a complex sequence of human activity from the late prehistoric periods, encompassing a variety of socio-cultural phenomena inter-connected with broader developmental changes in the surrounding regions (e.g., Avner et al. Citation2011; Davidovich Citation2012; Citation2013; Citation2014; Davidovich et al. Citation2014; Yekutieli Citation2004b; Citation2006a; Citation2006b; Citation2009). Among these has been the discovery of refuge episodes in the Late Chalcolithic and Early Bronze (EB) IB periods (Davidovich Citation2012; Citation2013), as well as the identification of traces of an EB II–III caravan route passing near the south-western shore of the Dead Sea (Yekutieli Citation2009). Contemporaneous with the appearance of the first urbanized communities in the southern Levant, these finds testify to the connectivity of the Judean Desert with emergent structures of corporate agency and identity, regional economics and exchange networks, territoriality and power relations.

Little attention has been given to assessing the extent of integration of human EBA activity in the Judean Desert within wider socio-structural developments in surrounding regions, probably in part due to the absence of substantial datasets that might function as viable proxies. The Mitzpe Shalem site cluster, located in the north-eastern Judean Desert, offers a unique opportunity for investigation of EBA connectivity. It sheds light on processes of inter-cultural engagement between communities to the south-east and north-west of the Dead Sea Basin: encounters organized around corporate activities that integrated and reinvented shared materialities of ritual practice.

The Mitzpe Shalem cluster

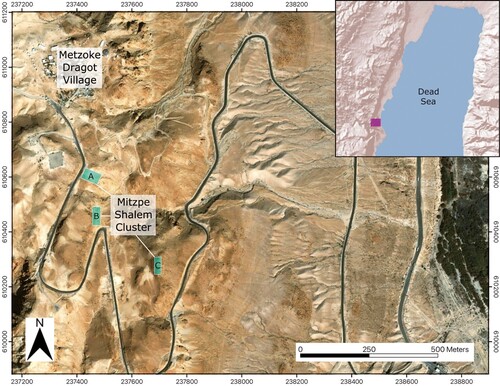

The cluster lies in the upper section of the western escarpment of the Dead Sea Basin (; Bar-Adon Citation1989: 50–82), situated c. 32 km south of Jericho (Tell es-Sultan), 23 km south-east of Beth Lehem, 39 km north-west of Bâb edh-Dhrâʿ, and 42 km north-east of Arad. The elements of the cluster were discovered during investigations carried out in the area between 1965 and 1975, initially by Ian Blake and subsequently by Pesach Bar-Adon; it was almost completely excavated by the latter. Despite its many distinctive features, the cluster has received only modest attention in research literature, mostly focused on its assemblage of tabular scrapers — the greatest quantity known from any single EBA site (over 400 according to Greenhut in Bar-Adon Citation1989; published discussions include e.g., Manclossi and Rosen Citation2022: 159, 172; Milevski Citation2013; Rosen Citation1997: 71–80). Important aspects of the cluster’s geography and overall profile have been under-emphasized. Moreover, due to its limited publication being in Hebrew, the site is almost entirely absent from EBA scholarship, and even from detailed discussions of tabular scraper distributions (e.g., Fujii Citation2011; Müller-Neuhof Citation2013; Quintero et al. Citation2002). This paper reassesses the site cluster through reconsideration of its geographic, morphological and artifactual traits, providing improved cultural contextualization the ritual activities at this unique cluster.

Cluster layout and environment

The area of the Dead Sea Escarpment in which the site cluster is located, north of Wadi Murabba’at, is one of the only sections along the western shore of the lake where the escarpment is broken and graduated, without a continuous vertical or near-vertical cliff, as a result of a series of parallel faults (; Mor and Burg Citation2000). The escarpment is divided into several natural terraces with broad slopes, separated by rocky bluffs. The area is utilized by one of the most comfortable routes that ascends the escarpment, an ancient path called Naqab Turabi/Trayba in Arabic, leading upwards from ‘Ain Turabi/Trayba to the desert uplands in the direction of the Herodium, Bethlehem and Jerusalem. ‘Ain Turabi is the southernmost freshwater spring in the oasis of ‘Ain Ghweir, the second-largest in volumetric flow along the western shore of the Dead Sea (Ben-Itzhak and Gvirtzman Citation2005). The summit of the ascent is located c. 150 m north of Site A, and its upper section passes c. 200 m north of Site B. Although there is no direct physical link between the sites and the route, and indeed the sites are not situated on an ancient pathway, this expedient ascent from the Dead Sea coast to the Judean Desert plateau was likely a major factor in the determination of the cluster’s location.

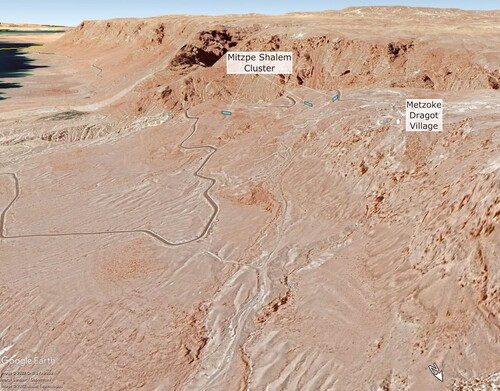

The precise topographic situation of the sites is no less important than their broader context. Site A is on a small hillock at the uppermost segment of the escarpment, a topographic context shared by many other sites of various types at the eastern edge of the Judean Desert plateau (; cf. Bar-Adon Citation1972). In contrast, Site B, which contained the highest concentration of archaeological materials and features within the cluster, is in the centre of a steep incline c. 40 m below the upper edge of the escarpment and c. 100 m south-east of Site A, on a narrow terrace, 2–7 m wide, within a rocky bluff (). Site B is accessible by a narrow pedestrian descent on the steep slope from Site A, or from the summit of Naqab Turabi. Several stone revetments, still observable, may have supported built footpaths (Bar-Adon Citation1989: 51). Site C is c. 300 m south-east of Site B, on a narrow ridge built up of large dolomitic boulders. A small valley separates Site C from the slope of Site B, while the escarpment continues its steep descent to the east ().

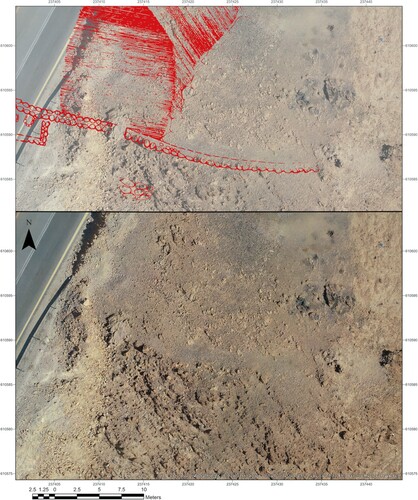

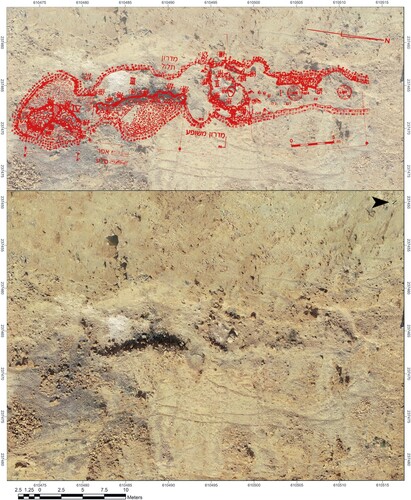

Figure 3 Aerial drone photography of the site cluster. The upper left image shows Site A, looking north. The upper right image shows Site B, looking south. The lower image shows Site A in the foreground, looking south-east towards Site C, while Site B is concealed from Site A, beyond a curve in the hillside.

The area between the sites lacks evidence of human activity, except for traces of footpaths. All three sites have impressive views of the Jordanian Highlands, while there is relatively limited visibility of the immediate environs, especially at Site B. Both sites A and B are visible from Site C, and both Sites A and C also have a panoramic perspective of the western side of the Dead Sea coast, but there is no direct sightline between sites A and B, despite their proximity to one another. Site B is situated immediately south of a curve in the hillside, a curve that creates a point of concealment from Site A, and is laid out along a ledge that follows a north–south axis such that no part of the site can be seen from Site A (). This straight ledge faces site C, and is on a slightly higher elevation than the latter. The topographic locations of sites B and C are unique among Judean Desert sites and imply a distinct function within the cluster.

Exploration of the site cluster

Some elements of the cluster were identified by Blake in the 1960s (Blake Citation1966: 564–65; Citation1967). The site that he explored, probably Site B, was known to local Bedouin as ramad (رماد), meaning ‘ashes’, a name testifying to burnt greyish sediments associated with this site, and sites A and C. Blake opened a small test trench in an undisturbed area of the site (see photograph in Bar-Adon Citation1972: 134, site 153e) and uncovered pottery and chipped stone fragments, including many tabular scraper pieces, some with incisions on the cortical face (Blake Citation1967: fig. 7). Pottery included painted bowl rims, burnished juglets, loop handles and body sherds with painted ‘net pattern’ decoration. The finds were initially dated to the EB I (Blake Citation1966: 565) but later assigned a broader chronological range encompassing the entire EBA (Blake Citation1967). Blake suggested an industrial or domestic function for the site and proposed that the early 3rd millennium BC inhabitants practiced desert agriculture. Blake’s excavation was never published.

Bar-Adon’s 1967 survey of the northern Judean Desert included, for the second time, field observations in the vicinity of the site cluster. Bar-Adon documented the principal features of Site A: a wall, approximately 60 metres long, on an east–west orientation, with attached architectural elements, and a charred surface to its north (site 662 in journal entries, 153d in the 1972 publication). In February 1972, Bar-Adon identified Site C, with burnt layers, as at Sites A and B, and coarse sherds that he initially dated to the Chalcolithic period.

In May 1972, Bar-Adon began excavations at Site B, continuing intermittently for 3 months — 28 work days in total (2–12 participants each day). The excavation was performed with no clear methodology and minimal documentation — apparently only journal entries and finds lists. No precise spatial units were allocated, and portions of the site were explored extemporaneously without clear definition. No basic units of archaeological recording (e.g., loci, baskets, wall numbers) are present in the journal entries or publication. The site was crudely divided into four spaces, with bounds only vaguely defined. Rough sketches and descriptions in journal entries pertaining to spatial and stratigraphic aspects are dense and crowded with internal numbering systems. Only in rare instances can features in the journals be related to those published.

From December 1974–February 1975, Bar-Adon directed similar excavations at Site C. Twelve days of fieldwork were conducted by 2–8 participants per day. As at Site B, the excavation lacked precise sub-divisions, and spatial and stratigraphic documentation is even more sparse.

No further exploration of the site cluster has been conducted since Bar-Adon’s excavations. There is no record of excavations at Site A in either the journal entries or publication. Bar-Adon prepared a short report on the excavation and ceramic assemblages as part of a Hebrew monograph summarizing his work along the western shore of the Dead Sea (Bar-Adon Citation1989), but died before completing it. Greenhut eventually completed this publication while preparing a concise report on the tabular scrapers (Greenhut in Bar-Adon Citation1989: 60–78), and re-examined the various features of the cluster. By that time, road construction had destroyed the western half of Site A.

Layouts and features

Prior to consideration of the cluster as an integrative domain of activity, it is important to understand the unique properties of each of the sites. All three have distinct profiles and features.

Site A

The main feature at Site A is a straight wall c. 60 m in length, built of 3–4 courses of field stones and oriented east–west along the southern edge of a small hillock (). Bar-Adon’s plans indicate that the wall ran continuously between, and perpendicular to, a rocky bluff to the west and a steep descent to the east. Its western section was cut by a modern road. North of the wall, a large deposit of grey sediment and burnt stone fragments was identified, covering c. 400 m2. In a small sounding, the deposit was found to continue to a depth of 0.2–0.4 m. South of the wall, in its western section, two adjacent rectilinear architectural units (5 × 4 m and 4 × 6 m respectively) were identified by Bar-Adon, bounded on their northern side by the long wall. These units were destroyed by the modern road mentioned above. Bar-Adon interpreted built elements at the site as a ‘hearth’ and ‘silo’ (Citation1989: 51). It is unclear to which elements these interpretations refer, or on what basis they were defined.

Figure 4 Orthophoto of Site A. The upper image is a superimposition of Bar-Adon’s site plan (Citation1989: fig 2).

Site B

Site B is complex, and its layout seems to have been determined to a significant extent by the natural morphology of the rocky ledge on which it is situated, thus it is composed of a series of narrow activity areas spread along a c. 38 m north–south axis (). Bar-Adon defined 4 areas, ordered southwards: I, a burnt area in the north of the site; II, a ‘platform’; III, a surface; IV, a second burnt area at the southern extent. Areas I and IV were described as closely comparable to the burnt layer at Site A. Area II included built features — a raised stone pavement (called a ‘platform’ by Bar-Adon Citation1989: 52) encircled by low walls, composed of a single course of fieldstones, and adjacently a rectilinear installation (dubbed a ‘silo’ by Bar-Adon) composed of three stone walls abutting the near-vertical face of the upper incline. Area III was composed of a surface supported by a slightly sloping stone revetment c. 6 m high. Area divisions are not mentioned in field journals, which refer to parts of Site B by various terms: ‘installations’, ‘hills’, ‘surfaces’, ‘floors’, etc. It is often unclear which terms refer to which features, and occasionally the same terms are used for different areas of the site.

Figure 5 Orthophoto of Site B. The upper image is a superimposition of Bar-Adon’s site plan (Citation1989: fig. 2).

Journals record that ashy sediments were visible on the surface in some areas, but in others were covered by light-coloured sediment and stones, forming slight rises dubbed ‘hills’. The depth of accumulation varied across the site but reached as much as 1 m in places. The depth of burnt sediments in areas I and IV is cited in the publication as 0.2–0.3 m and 0.7–0.8 m respectively (Bar-Adon Citation1989: 54). The rectilinear installation in Area II, with walls preserved to a height of 0.6 m, was entirely exposed during excavation. The scale of accumulation is also evident in quantities of excavated sediments deposited on the slope below Site B.

Site C

Site C lacks architectural elements and is mainly composed of a single area of accumulation spread over c. 100 m2 and a few other pockets of accumulation between large boulders. The accumulation exceeded 0.5 m in some places. The main area of the site is situated c. 15 m north-west of the peak of the ridge. Journal entries document the presence of boulder fragments that collapsed onto burnt layers and were removed during excavation.

Despite the low spatial and stratigraphic resolution recorded at the site cluster, it is possible to make a few general observations. Firstly, architectural remains are limited, and activity areas are not necessarily bounded by architecture. Secondly, the sites are characterized by deep accumuluations of sediment (especially at Site B) and, by implication, a substantial phase of activities, either intensivly over a short period, or in repeated visits over a considerable period. Finally, the most characteristic archaeological features of the three sites are distinctive burnt sediment layers. To clarify the nature of activities and formation processes that created these deposits, the burnt layers must be sampled and subjected to scientific sedimentological analysis, but it can already be noted that these sediments contain little material culture (e.g., pottery, flint) relative to other areas.

Finds

Material culture remains from the cluster are mainly pottery and flint, along with a few small finds. Most of the ceramic assemblage was accessed for the present study and all of the published indicative pottery was identified, as well as additional unpublished fragments. Around 50% of the vessels recorded in the finds lists were successfully identified by registration number; considered as a sample of the total assemblage, all finds identified were subjected to quantitative analysis. Lists provided spatial information at the resolution of Bar-Adon’s sub-divisions of site B, which allowed approximate spatial analysis. Occasionally the lists even offered finer detail, specifying whether artefacts came from within the rectilinear ‘installation’, or adjacent to it, or from the ‘platform’ at Site B, Area II. Similar quantitative and spatial analyses were performed on the flint assemblage, although for this the authors relied entirely on finds lists and illustrations, as the assemblage itself has, regrettably, not been located.

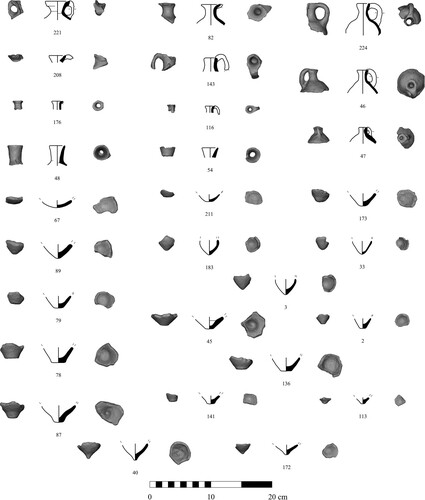

Pottery

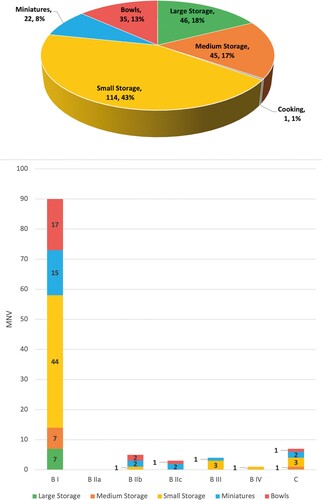

Some 1394 sherds were examined from the Mitzpe Shalem cluster, and a minimum number of 268 vessels were identified. The ceramic assemblage from Mitzpe Shalem mainly contains small (diam. < 10 cm) and miniature (diam. < 5 cm) closed storage containers (juglets, bottles and amphoriskoi) which make up 51% of vessels. There is a relatively low proportion of medium and large closed vessels for storage (17% and 18% respectively), and an extremely low proportion (1%) of cooking vessels (holemouth jars). Small, rough serving wares account for 13% of vessels.

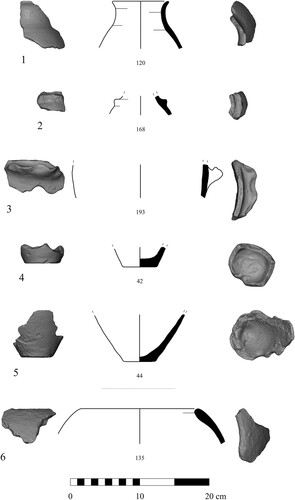

Storage jars (). Very few indicative sherds belong to large or medium closed vessels, and little typological commentary can be formulated based on the few available examples. One wavy, ledge-handle (:3) probably belongs to a large storage jar. The three deep-folded indentations are typologically characteristic of the EB II period, with examples present at sites throughout the surrounding regions, from the northern Negev, coastal plain, Shephelah, Judean Hills and south Jordan. The only close parallel for a vestigial ledge-handle fragment, positioned immediately below the neck, was identified in pottery from EB IB Bâb edh-Dhrâʿ (see , :2). The only rim fragment (:1) belongs to a medium-sized storage jar with an outward-inclined neck, typical of EB I–II contexts in general. Two plain base fragments (:4–5), also from medium storage jars, are not typologically significant, and may belong to medium-sized jars or jugs from any EBA phase.

Table 1 Ceramic descriptions and typological parallels

Cooking vessels (:6). A single indicative sherd belongs to a thickened-rim holemouth jar. The very large, poorly sorted, angular grains of calcite observable in the fabric matrix are typical of EB I–II examples from sites in the Negev, including Arad, but are found at sites throughout the southern Levant west of the Jordan Valley (see ). As stated, it is the absence of holemouth jar forms (generally, one of the most common types in south Levantine EBA assemblages) that is noteworthy at Mitzpe Shalem, potentially testifying to a specialized overall function and a lack of activities associated with everyday life.

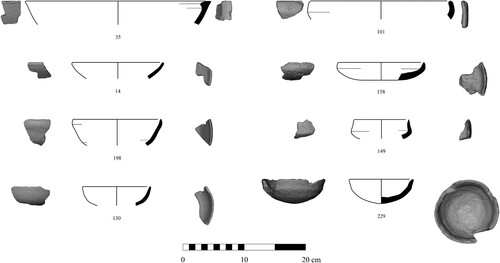

Bowls (). Bowls show little typological variation, and are mainly small, plain, globular forms typical of the EBA period in general (:2,3,5,7; ). A lamp-bowl with slight carination near the sharpened rim (:8), and a carinated platter with a sharpened rim (:4) have close parallels at sites in the EB I–II Lower Jordan Valley and northern Negev, as well as at Bâb edh-Dhrâʿ in the south-eastern Dead Sea plain (see ). A single deep, red-slipped carinated bowl with an outward-curving, near-vertically-inclined wall (:6) is of a type present in large numbers at EB I–II Tell el-Far’ah North and EB II–III Jericho (see ). Red-slipped hammer-rim bowls (:1) of the type represented in the assemblage are present in EB I–II contexts throughout the region (see ).

Juglets/miniature vessels (). The greatest typological variation in the ceramic assemblage exists among the small and miniature storage containers, which also constitute the largest group represented. Small and miniature vessels were classed in the same group, due to the unlikelihood of a contextual distinction in their function at the cluster. Body shapes include globular (:1,2,3,9,12,13) and drop-shaped (:5,6) forms, and a few lemon-shaped vessels (:15,16,17,18). Most vessels have a single loop-handle, roughly formed and rising slightly above the height of the rim (:1–9). A small number have knob decorations, or lug handles. A single fragment of a miniature tube handle was identified (not illustrated). There is one complete miniature loop-handled juglet with red slip, and a complete miniature amphoriskos with two small loop handles on either side of a narrow neck (). Parallels to the latter were present in tombs at ʿAi, Jericho and Bâb edh-Dhrâʿ, as well as a very close parallel in Layer II Tell Arad (see ). Bases include curved (:12–14), plain flat (:19–23), pointed (:15–18), and small flat ‘button’ types (:24–28). At Bâb edh-Dhrâʿ, a typological progression was demonstrated from curved and plain flat bases in the EB II, to pointed and button base types diagnostic of the EB III period (Schaub and Rast Citation1989: 429–40; figs 256–257). The same approximate chronological progression is observable in tombs at Jericho (compare tombs A 108 and A 127 with tomb D 12 — Kenyon Citation1960: figs 23, 25, 34–35, 37). Likewise, pointed and button base types are absent from EB II Arad and mortuary contexts at ʿAi and Tel el-Far’ah North (Amiran Citation1978: pls 14, 25, 30; Callaway Citation1964: pls 14, 16; De Vaux and Steve Citation1948: fig. 120). Given that the pointed and button base represent a minority, it is reasonable to conclude that most of the small and miniature closed vessels date to the EB II period, with a small number dating to early EB III.

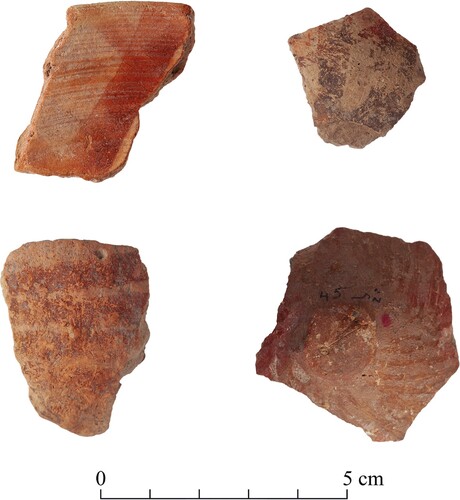

Varia. A few body sherds with red/brown band painted decoration were identified in the assemblage (). The bands are characterized by stripes and approximately hatched patterns, although the width and directions are heterogenous and uneven. They most closely resemble ‘splash’ and ‘drip’ styles found at sites in the central and southern Lower Jordan Valley, and are most prevalent in EB IA (Milevski Citation2011: 76, fig. 3.11). An alternative parallel is the line-group pottery identified at EB IB Tel Arad and Bâb edh-Dhrâʿ. More precise geometric net patterns are found in EB II assemblages (e.g., Bâb edh-Dhrâʿ — Schaub and Rast Citation1989: 428–30, fig. 256; ʿAi — Callaway Citation1964: pls XI, XVI) but, as stated, these do not correspond well to the crude and uneven lines observed on the Mitzpe Shalem ceramics. The low frequency and small size of these painted fragments (without morphologically indicative elements) restrain chronological interpretation.

Spatial distribution. Regrettably only 116 out of 268 vessels could be associated with approximate spatial information. None were listed as having been located at Site A. Of the 116 vessels, 108 were exposed in excavations at Site B, and the remaining eight were from Site C. This may partly reflect the more limited excavation undertaken at Site C, but also, perhaps, a bias in the preservation of spatial data. The eight vessels from Site C included a painted bowl rim fragment, the base fragment of a medium-sized vessel, three juglet fragments and two fragments of miniature vessels. One fragment was functionally indistinct. Despite potential biases, even among these eight vessels, the proportional functional distribution of pottery from Site C approximately equals that of the entire cluster ().

Figure 11 Functional distribution of the ceramic assemblage overall (pie chart) and by area (bar chart).

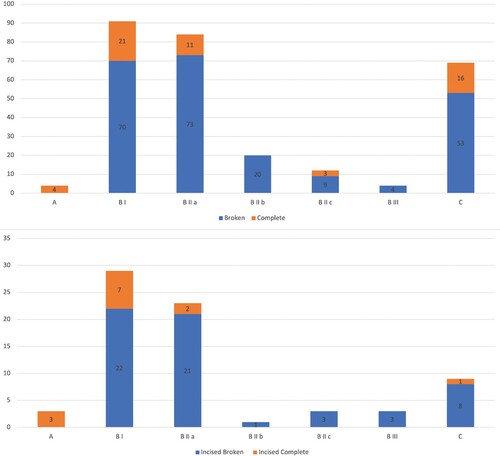

At Site B, the distribution of vessels is dramatically weighted towards Area I (90 out of 108 vessels; 83.3%; B I in ). Only a handful of vessels were associated with the rectilinear ‘installation’ in Area II (three small/miniature vessels and two bowls; 4.6%; B IIb in ). Three vessels were associated with the ‘platform’ area (one bowl and two miniatures; 2.8%; B IIc in ), four with the Area III ‘surface’ (all small/miniature vessels; 3.7%; B III in ), and a single juglet fragment was associated with burnt layers in Area IV (0.9%; B IV in ). In Area B I, the proportional functional distribution of vessels mimics that of the whole cluster (), only with a more extreme minority of large and medium storage vessels, both constituting a mere 8%. Miniature and small storage types constitute 65% of vessels from B I (16% and 49% respectively).

Overview. The ceramic assemblage from Mitzpe Shalem is extremely unusual in its functional composition. Low frequencies of domestic vessel types, such as cooking and serving wares (excepting small bowls), clearly indicate that the typical range of activities characterizing permanent or temporary settlement were not represented at the cluster. At sedentary sites, cooking and serving vessels usually constitute 30–60% of assemblages, while at nomadic campsites their proportions range from 60–90% (see Atkins Citation2021: fig. 8.4; Atkins and Yekutieli Citation2022: fig. 4.1b). EB I sites in North Sinai, which apparently functioned as trading stations between Egypt and the south-western Levant, contained low numbers of cooking and serving wares, but, conversely, large and medium-sized storage vessels were dominant (Atkins Citation2021: 168, fig. 8.4; Yekutieli Citation2002). The proportionally low quantities of storage vessels in the Mitzpe Shalem assemblage seem to preclude either long-term habitation or significant exchange of large-volume stored goods (e.g., agricultural products).

The overall functional distribution of the pottery is neither domestically nor economically oriented. Its most significant aspect is the dominance of small and miniature closed vessels, which most closely parallels assemblages from EBA tombs, although in these contexts large serving vessels are usually present in significant quantities (e.g., Jericho — Kenyon Citation1960; ʿAi — Callaway Citation1964; Bâb edh-Dhrâʿ — Schaub and Rast Citation1989). Nonetheless, this strong typological correspondence is indicative of symbolically charged practices, conceptually analogous to corporate social phenomena experienced during mortuary rites. Symbolic activities are the most credible explanation for the ceramic assemblage profile, in light of other interpretative proxies from the cluster (see discussion below).

The ceramic assemblage exhibits cultural connectivity with regions to the north and south; particular dominance of typological connections with sites in the central and southern Lower Jordan Valley, and Bâb edh-Dhrâʿ in the south-eastern Dead Sea Plain. Distinct components within the assemblage correspond with each, indicating a convergence of cultural elements at Mitzpe Shalem. This correlation agrees, approximately, with the results of petrographic analyses conducted at the time of publication, which traced likely sources for clays to either Jordan or the north end of the Dead Sea (Goren Citation1989). Given the lack of evidence for commercial or exchange activities, this convergence is best explained by encounters between actors from at least two cultural spheres.

Chipped stone

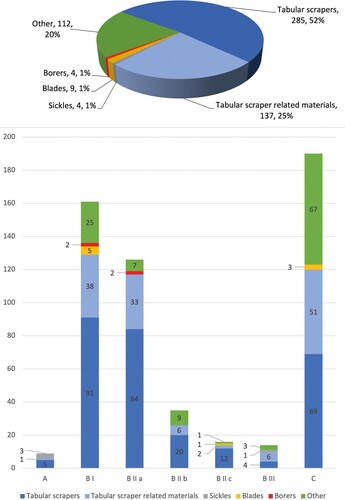

As stated, the most extensively discussed aspect of material culture from Mitzpe Shalem is the chipped stone assemblage, in particular tabular scrapers (e.g., Manclossi and Rosen Citation2022: 159, 172; Milevski Citation2013; Rosen Citation1997: 71–80). The published assemblage (Greenhut in Bar-Adon Citation1989) included only tabular scrapers, with no reference to additional items, whether fragmentary artefactual material or complete tools. Yet, finds lists record a variety of materials, albeit with a clear dominance of tabular scrapers and tabular scraper fragments ().

Figure 12 Functional distribution of flint tools, as recorded in Bar-Adon’s unpublished finds lists and illustrated here: overall (pie chart) and by area (bar chart).

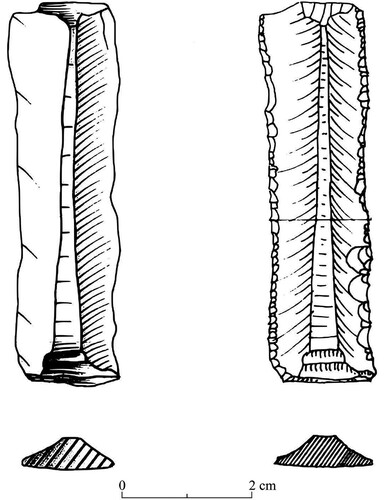

The finds lists’ record 551 items. Nine blades, four sickle blades and four borers are identified. Of these items, two sickles were drawn, and are Canaanean blade segments, one with serrations on both edges, the other with straight cutting edges (). Without access to the artefacts, it is impossible to know whether the blades have glossy edges. The nearest EBA centre of production for Canaanean sickle blades is Fatzael in the Lower Jordan Valley (Zutovski and Bar Citation2017). Canaanean blades were also present at EB II Arad (Schick Citation1978) and EB I Bâb edh-Dhrâʿ (McConaughey Citation2003), while manufacturing sites have been identified at Tel Sera in the northern Negev, and Gat Guvrin where dozens of cores were found (Milevski Citation2011: 94; Oren Citation2001; Perrot Citation1961). Of the chipped stone artefacts 112 were small ‘fragments’ or ‘tools’, lacking clear definition in finds lists. Their spatial distribution indicates that they may belong to the ‘tabular scraper related materials’ group (), perhaps including items so small as to evade interpretation. The finds lists seem to lack almost any record of flint artefacts that were not finished tools or fragments of finished tools (e.g., debitage, cores), albeit with the possibility that some of the ‘fragments’ represent production waste or debitage resulting from tool modifications. The registered assemblage may be partly a result of collection bias, but it still seems that finished tools, and specifically tabular scrapers, were predominant in the flint assemblage.

Figure 13 Canaanean blades from Mitzpe Shalem, illustrations from Bar-Adon’s unpublished documentation.

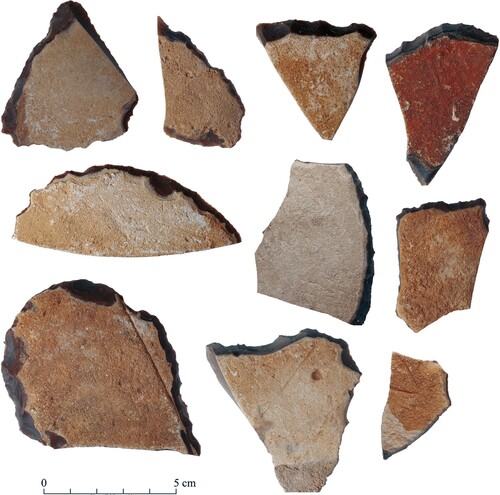

Tabular scrapers () — 422 items were identified in finds lists as either tabular scrapers or related materials described in nebulous terms, such as ‘tabular flake’ and ‘tabular tool fragment’. Many of the tabular scrapers are accompanied by additional descriptions, although these too are unclear and ambiguous: many are listed as ‘tabular side scrapers’, while several appear as ‘elongated tongue-shaped tabular scrapers’. Of the 284 items clearly defined as tabular scrapers, 55 (19.4%) are listed as complete () while the remainder were broken. Based on an initial analysis of the tabular scrapers from Mitzpe Shalem, Shoh Yamada observed repeated patterns in fracture points that indicated they were broken deliberately, that, along with a lack of use-wear polish that suggested non-utilitarian function, suggested to him that the tools were ritually ‘cancelled’ (Citation2006; pers. comm.). Manclossi and Rosen (Citation2022: 59–61) noted that the large quantities of broken tools, and the precise central fracture points, support Shoh’s hypothesis (Citation2006).

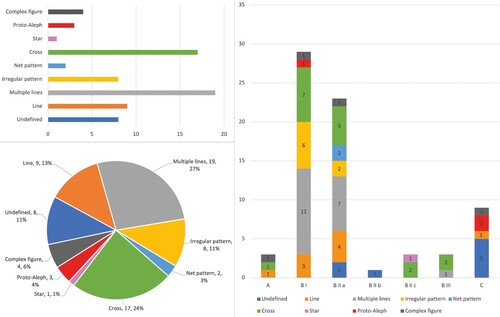

Incised symbols — according to the lists, 71 tabular scrapers have cortical incisions, in a range of types: single line, multiple lines, irregular pattern, net pattern, cross, star, proto-aleph and complex figure (). The most common type is a multiple lines symbol (N = 19, 27%), a type widespread on tabular scrapers at other EBA sites in the Lower Jordan Valley, south-eastern Dead Sea plain, Judean Lowlands, Negev and South Sinai (Manclossi and Rosen Citation2022: fig. 4.2). Examples of cross symbols, the second most common type at Mitzpe Shalem (N = 17, 24%), are also common at EBA sites from the South Sinai to the Galilee region (Manclossi and Rosen Citation2022: fig. 4.3). Other types represented at the cluster — the single line (N = 9, 13%) and irregular pattern incisions (N = 8, 11%) — are widespread at sites in the Judean Hills, Lower Jordan Valley, Galilee, Golan Heights and northern Jordan. Interestingly, these types are virtually unrepresented at southern sites (except the single line type at Arad). Most of the rarer incision types at Mitzpe Shalem (proto-Alephs, stars, complex figures; see ) are likewise rare regionally, although there is little identifiable pattern in their geographic distributions. Net pattern incisions are widespread, but rare at Mitzpe Shalem (Manclossi and Rosen Citation2022: figs 4.2, 4.3, 4.4). A typological development has been proposed, with more complex iconographic types appearing later (e.g, Milevski Citation2011: 98), although such a progression is difficult to demonstrate through sequencing of securely dated contexts.

Figure 16 Tabular scraper incisions type distribution analysis: (left pie and bar charts) distribution of tabular scraper incision types in entire assemblage; (right bar chart) intra-site distribution of tabular scraper incision types.

Parallels to symbol types found on tabular scrapers have been identified on EBA pot marks, incised pebbles and stelae from Egypt to northern Jordan; they have been interpreted as signs that embody concepts that transcended boundaries of the EBA world (Manclossi and Rosen Citation2022: 50–52, fig. 4.6). Their absence from production sites seems to preclude the possibility that the symbols might be manufacturer’s marks, although their idiosyncrasy is indicative of an association with personal practices related to identity, or even ownership (Manclossi and Rosen Citation2022: 46, 50; Milevski Citation2011: 98; Rosen Citation1997: 75). In the finds lists 58 incised tabular scrapers are listed as broken and 13 as complete (). Archived illustrations from Bar-Adon’s excavations demonstrate that at least 36 of the broken scrapers (>62% of the broken examples) were fractured on incised symbols in such a way that obfuscates their form. This can credibly be interpreted as deliberate defacement, or other symbolically charged practices related to the symbols.

Spatial distribution — the spatial distribution of chipped-stone artefact types in areas at the site cluster is shown in (defined according to Bar-Adon’s spatial divisions using information from finds lists). The low number of items from Site A is, at least, partly due to limited excavation of the site. At Site B, there is a clear concentration of material in Area I, the northern burnt layers, and from the immediately adjacent rectilinear installation, Area IIa. There is an overall decline in frequency from north to south at Site B, with a complete absence of documented items from burnt layers in Area IV. In Area II, far more chipped-stone artefacts were found within the rectilinear installation than in the immediately adjacent Area IIb or the IIc platform. The 84 tabular scrapers from the small built unit can only be described as a cache. Area III (indistinguishable from Area IId in finds lists), despite constituting approximately one third of the surface area at Site B, contained only 14 chipped-stone artefacts (mostly flakes and nondescript items). A large proportion of the materials were retrieved from Site C (N = 190, 34.5%).

The same overall spatial pattern can be observed in the tabular scraper component specifically (see also ), with high frequencies at Site B, Areas I (N = 91, 32.0%) and IIa (N = 84, 29.6%), and at Site C (N = 69, 24.3%). The proportion of incised examples is significantly lower at Site C (N = 9, 12.7%), with even higher proportions at B I (N = 29, 40.8%) and B IIa (N = 23, 32.4%). Among these, nearly all net pattern incisions were retrieved from Site C (N = 5), along with two proto-alephs, one complex figure, and one single line (). In other words, the rarest incision types are unusually strongly represented at site C. At Site B, incision types broadly follow the same distribution pattern as the overall distribution of chipped stone, with high frequencies in Area I and IIa, and low frequencies in the other areas. Notably, Area B IIb (adjacent to the rectilinear installation) contained only a single undefined incision. The only star incision came from Site B IIc (the platform area). The sample from Site A is small and subject to collection bias, although a tabular scraper with a complex figure incision retrieved from the site is noteworthy.

Overview — even without access to the materials, excavation documentation reveals a clear dominance of tabular scrapers in the chipped stone assemblage. This may, in part, be due to the ‘pretty piece syndrome’ (Rosen Citation1997: 37), a collection bias emphasizing large, easily visible, or aesthetically pleasing artefacts. Nonetheless, raw numbers of tabular scrapers dramatically exceed that from any other known sites and testify to a unique site profile. Functionally, this profile was apparently unrelated to tabular scraper production and/or exchange, given the likelihood of deliberate on-site destruction of most of the scrapers. Mitzpe Shalem was clearly the final destination in the use life of the majority of these tools.

Incised symbols types include, essentially, the full range known regionally, in approximately the same distributions according to proclivity/rarity. Noteworthy is the presence of both single line incisions and irregular pattern incisions, for which parallels are only documented in cultural spheres to the north. That the symbols present on tabular scrapers were so prevalent throughout the EBA world as shared concepts, found also as potmarks, and in other contexts, raises the possibility of their function as transcultural devices in practices of encounter (discussed further below).

Activities at Mitzpe Shalem resulted in concentrated deposits of chipped stone in Area I at Site B, in a cache in the Area IIa rectilinear installation, and at Site C. This parallels the high concentration of ceramic material at B I, as well as its presence in Areas B II and C. On the other hand, contexts in which pottery is relatively rare (e.g., B IV) also yielded only small quantities of chipped stone.

Small finds

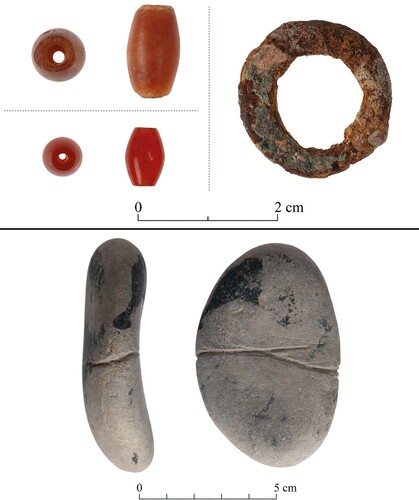

A few small finds were noted in the original Hebrew publication of the cluster, including an amber bead and small ‘copper tool’ fragments. These were not present in the finds’ lists, although two red agate beads are listed. Two beads (4 mm diam. and 3 mm diam.) were identified in the stored materials, as well as a small copper ring (2 cm diam.) and an incised pebble (). One of the beads is from Area B I, and the other from the nearby rectilinear installation (B IIa). They are probably both carnelian, not agate or amber. Carnelian beads are known at EB I–III sites, but are most common in the EB I period, with particularly large numbers identified at Bâb edh-Dhrâʿ and in two tombs at Jericho (Kenyon Citation1965: 19–26; Milevski Citation2011: 171; Wilkinson Citation1989).

Dating

As stated above, upon its discovery Blake dated Site B to the EB I period, later amending his interpretation to span the entire EBA. During excavations at Site B, Bar-Adon was inclined, based on the appearance of coarse potsherds, towards a Chalcolithic date, but he later became persuaded of an EBA component in material culture from the cluster. It was during preparation of excavated materials for publication that his dating was limited to the EB I–III, due to the lack of any indicative Chalcolithic material, and the presence of large numbers of incised tabular scrapers. Use of tabular scrapers, the main component in the chipped stone assemblage, spans the entire Pottery Neolithic to EB III periods, but incised tabular scrapers are only present in EB I–III contexts (Manclossi and Rosen Citation2022: 17; Rosen Citation1997: 75).

Without radiocarbon dates, it is difficult to establish a secure dating for the cluster. Most of the ceramics have typological parallels from the EB II period (most examples have parallels that span either the EB I–II or II–III periods for specific types), although the pointed base and button base juglets only have parallels from the EB III period. Conversely, closest parallels for the few red-painted sherds are dated to the EB I period. It is therefore tentatively suggested, that the main phase of activities at the cluster was in the EB II, with continuity into the early EB III period. Yekutieli (Citation2006b: 120–21) has noted a close comparability between the ceramics of Mitzpe Shalem and EB II–III pottery from surveys in the area of Nahal Zohar, south of En Boqeq. No sherds indicative of the EB Ib1 ‘Erani C’ horizon were identified at Mitzpe Shalem, while such types were relatively common in caves in the Judean desert and have been interpreted to represent an episode of temporary refuge in this phase (Davidovich Citation2012). The lack of these types at Mitzpe Shalem indicates that there was no activity phase contemporaneous with, or in any way related to, these cave occupations. Notwithstanding, based on typological parallels alone, it is possible that the first phase of activities at Mitzpe Shalem dates to the final phase of the EB I.

Discussion

Both Blake and Bar-Adon believed that the Mitzpe Shalem cluster fulfilled a primarily industrial function, although this interpretation is absent from documentation from Bar-Adon’s excavations. Blake even proposed that stone revetments near Site B constituted terracing for desert agriculture (Blake Citation1967). The publication of Bar-Adon’s excavations does not contain even a cursory discussion of the cluster’s functional profile, but isolated comments reveal that by this point Bar-Adon and the finds specialists (Greenhut — chipped stone; Goren — petrography) were inclined to view Mitzpe Shalem as a ritual centre (e.g., Goren Citation1989: 78). Nonetheless, interpretative elements in descriptions of the cluster illustrate that domestic and/or economic activities were still considered aspects of the overall profile (e.g., references to silos, ovens and other installations in Bar-Adon Citation1989: 51–54).

The geographic, spatial, morphological and material culture characteristics of the cluster are unique among sites of the EBA southern Levant. Existing excavated materials and documentation from excavations, although limited, provide clear parameters for more detailed interpretation.

Firstly, there is no possibility that the cluster was either sedentary or domestic in character. The geographic and topographic situation of the sites, and their architectural features, do not fit the profile of permanent sedentary life or temporary encampment. The sites lack structures that might potentially serve as dwellings, with the possible exception of a single, small rectilinear unit at Site A. There is no basis to the interpretation of any features as either agricultural silos, or domestic cooking installations. The scattered preserved sections of wall between Sites A and B, and the narrow ledges that they support, could not contribute to effective agricultural terracing, and are much more credibly explained as revetments to footpaths. The ceramic assemblage, as stated, is unusual and not characteristic of sedentary or semi-sedentary life, with low proportions of storage and serving wares, and a near absence of cooking vessels. The depth of sediment in several areas, particularly at Site B, is indicative of extensive use, but the data does not support an interpretation of prolonged habitation, therefore, cultural remains must have accumulated over numerous repeat visits relating to a particular set of activities.

Likewise, an industrial interpretation of the cluster does not stand up to critical scrutiny. The EBA tabular scraper production system is well documented (Manclossi and Rosen Citation2022: 66–84), with workshops located in close proximity to outcrops of primarily Eocene flint nodules in the Negev Highlands, South Sinai, the Hamad of eastern Jordan and the Jafr Basin in south-eastern Jordan (Abe Citation2008; Fujii Citation1998; Citation1999; Citation2000; Citation2001; Citation2002; Citation2003; Citation2011; Kozloff Citation1972; Müller-Neuhof Citation2006; Citation2013; Quintero et al. Citation2002; Rosen Citation1983; Wasse and Rollefson Citation2005). No such outcrops are known from the Judean Desert or adjacent regions, and neither raw flint nodules nor blanks for tabular scraper production have been identified at Mitzpe Shalem.

Since all the ceramic fabrics identified by petrographic analysis were sourced outside of the immediate environs of Mitzpe Shalem (Goren Citation1989), a ceramic workshop at the cluster can be ruled out. The small finds, copper and carnelian, were also clearly not manufactured on site. There is no evidence for exploitation of local minerals, such as Dead Sea asphalt or salt. All these factors, in tandem with the lack of installations or waste products, render an industrial interpretation untenable.

Further, the cluster does not fit the profile of a waystation. The comfortable ascent of Naqab Turabi passes north of the site cluster, with no apparent connection between the route and the sites. Moreover, the architectural features and material assemblage from the sites bear no resemblance to that of a waystation, with no identifiable shelters and a relative lack of cooking pots or large serving wares (cf. Yekutieli Citation2006b: 111–13 regarding site 48-4, a waystation on the EBA Zohar Ascent). The proximity of the cluster to the Naqab Turabi is significant nonetheless, and it is likely that people who were already familiar with the comfortable ascent in the area chose the location of Mitzpe Shalem, for whatever reason, to conduct certain activities apparently disconnected from the practicalities of travel.

Mitzpe Shalem as an intercultural liminal space

With no credible ‘utilitarian’ explanations for the unique overall profile of Mitzpe Shalem, an interpretation of ‘ritual practice’ best explains aspects of its geographic situation, layout and material culture components that are indicative of symbolically charged activities:

the unique promontory position of Site C;

the long, narrow ledge on which Site B is laid out, in the middle of a very steep incline, unique among EBA sites of the Judean desert;

the concealed position of Site B, relative to Site A, beginning at the exact point that the hillside curves out of sight;

the relative visibility of Site C in relation to Sites A and B, giving the impression of an intentional focal point;

the broad burnt areas at all three sites, composed of several layers of sediments and burnt stones, indicative of many repeat events;

the circular platform at Site B with a central pillar(?), adjacent to a small rectilinear stone unit built into the cliff face, that contained a large cache of tabular scrapers;

the functional profile of the ceramic assemblage, strongly oriented towards small and miniature storage vessels, the majority of the parallels for which originate in EBA tombs;

the very large numbers of tabular scrapers, most of which were, apparently, intentionally broken, in many cases defacing symbols incised on the cortex.

The unique and ostensibly non-utilitarian character of the Mitzpe Shalem cluster can be read as ‘ritual anti-structure’, a mode of interpretation innovated by Turner, that emphasizes transformational aspects of ritual practices and process (Turner Citation1969; Citation1982; Citation1985). Turner viewed rituals intended to redress systemic societal tensions as dramas, or ‘performances’, that established and maintained cohesion, and explained these dramas in terms related to conflict. The first stage in the rituals, which Turner called the ‘breach’ (Citation1985: 180), involved an action or practice that brought participants out of the normal social order, into a place of ‘crisis’. The ‘crisis’ was another term for Turner’s concept of liminality, which was a socio-psychological state in which the structures of society have fragmented, and radically different or even reverse realities can exist (Citation1969: 95–96). What Turner called ‘redressive action’ was then required within the liminal context, which would provide ‘a distanced replication and critique of events’ through ritualized performance (Citation1985: 180). This would be followed either by reintegration of participants into a socially cohesive unit, or the acceptance of ‘irreconcilable schism’.

While the interconnectivity of EBA urban centres in the regions surrounding the Dead Sea Basin may not have been so complex, nor paradoxical, as the internal structures of the Ndembu society studied by Turner, Mitzpe Shalem is amenable to interpretation based on his concept of liminality. The location of the cluster, apparently intentionally distanced from the locales of EBA everyday life, fits well with Turner’s conception of liminal spaces as contexts in which separation from normal life was a necessity. The cluster’s incongruity within the wider EBA world, and its simultaneous material connectedness to cultural spheres to the north and south, may be viewed as a physical signature of ‘anti-structure’. This involves a ritualized inversion or deconstruction of accepted norms. The cluster may have functioned as a liminal space for symbolic encounters between representatives from distinct socio-political entities, most likely centred on the south-eastern Dead Sea region (Bâb edh-Dhrâʿ) to the south, and the Lower Jordan Valley (Jericho) to the north.

Elements of cross-cultural symbolic practices were incorporated into activities at Mitzpe Shalem. Tabular scrapers were incised with symbols whose meaning was familiar to and shared by the participants, and subsequently, at some stage in the performance of the ritual, the objects were broken and the shared symbols along with them — one physical expression of the liminal anti-structure process into which participants had entered. Small and miniature votive vessels, commonly incorporated into funerary rites at sites in both the north and south, were re-contextualized at Mitzpe Shalem and their social meaning either adjusted or transformed. As stated above, the votive vessels identified at Mitzpe Shalem are very rare in non-mortuary contexts, and the high frequency of such vessels at the cluster is indicative of activities that were extremely incongruous to the habitus of participants, representing a clear break from structure.

Encounters may have been held to settle disputes, establish treaties, exchange marital obligations, or reaffirm the status of leaders. The clear parallels between the material culture assemblage from the Mitzpe Shalem cluster and contemporary tombs may imply that the sites fulfilled some mortuary role. But given the absence of human remains or burials at Mitzpe Shalem, or at any contemporary site in the surrounding region, the cluster’s association with funerary rituals remains enigmatic, and should be the subject of further study. Notwithstanding, the cluster’s affinity with mortuary contexts contributes to the impression of its liminality, in that it exists within a socio-cultural arena shared by points of transition between the worlds of the living and the dead.

The three sites of the Mitzpe Shalem cluster seem each to have fulfilled distinct roles within the ritual performance. Site A seems to be the most likely gathering point of the three, situated in the highest point of the escarpment, in an accessible location with high visibility on the surrounding area. Sites B and C were probably the main nodes of ritual practices involving numerous material elements that were brought to the sites (pottery vessels, tabular scrapers). Within site B itself, the arrangement of the site, the fragmentary architectural remains, and the concentrations of artefactual material in certain spaces indicate a sub-division oriented around the performance of particular practices in each area. The location of site B, at a point of concealment from site A, but directly facing site C, may represent the physical ‘gateway’ to the liminal space of ritual practice. Site C seems to be at a physical ‘focal point’ in the landscape, directly facing sites A and B. Practices at site C may have represented the climax of the ritual performance, with onlookers at sites A and B observing and responding, perhaps by means of simultaneous and related practices involving the same material culture elements, and probably accompanied by physical and oral expressions that are impossible to reconstruct.

A more detailed understanding of specific dynamics within the ritual process at Mitzpe Shalem demands fresh sampling and laboratory analyses, integrating advanced scientific techniques including sedimentology, residue analysis, use-wear analysis, and more. Nonetheless the reconsideration of the cluster presented here already highlights its extraordinary traits as a unique ritual context within the EBA world, with evidence pointing to intercultural encounters connecting socio-cultural spheres to the north and south through corporate ritual performances. The Mitzpe Shalem cluster offers a new interpretative direction for the EBA Judean Desert as a desert frontier zone — an uninhabited and liminal environment, in which unique practices could exist. These practices, among other things, emerged through processes of connectivity between disparate worlds, and are an expression of their connectedness.

Acknowledgements

Sincere thanks to the staff of the Israel Antiquities Authority for providing access to archaeological materials from Mitzpe Shalem, and to Doron Bar-Adon for providing access to field journals and other documentary materials that belonged to his father, Pesach Bar-Adon.

References

- Abe, M. 2008. The Development of Urbanism and Pastoral Nomads in the Southern Levant — Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age Stone Tool Production Industries and Flint Mines in the Jafr Basin, Southern Jordan. PhD. University of Liverpool.

- Amiran, R. 1978. Early Arad I, The Chalcolithic and Early Bronze City. First–Fifth Seasons of Excavations, 1962–1966. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society.

- Atkins, S. 2021. The Role of Negev Highland Pastoral Nomadic Societies in Interactions Between Nilotic and South-west Levantine Groups During the 4th and Early 3rd Millennia BC. PhD. Ben Gurion University of the Negev.

- Atkins, S. and Yekutieli, Y. 2022. Correlating Egyptian-Levantine connectivity in ceramic assemblage profiles: between Tel ‘Erani and Miẓpe Sede Ḥafir. In, Golani, A., Varga, D., Tchekhanovets, Y. and Birkenfeld, M. (eds), Archaeological Excavations and Research Studies in Southern Israel, Collected Papers Volume 5, 18th Annual Southern Conference: 29–48. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority.

- Avner, U., Shalmon, B., Hadas, G., Porat, R. and Kolska-Horwitz, L. 2011. Carnivore traps in the Negev and Judean Desert (Israel): function, location and chronology. In, Brugel, J.-P., Gardeisen, A., and Zucker, A. (eds), Prédateurs dans tous leurs états: Évolution, Biodiversité, Interactions, Mythes, Symboles: 253–68. Antibes: ADPCA.

- Bar-Adon, P. 1972. Surveys in the Judean Desert and Jericho Valley. In, Kochavi, M. and Ovadiah, R. (eds), Judaea, Samaria and the Golan. Archaeological Survey, 1967–1968: 92–152. Jerusalem: Carta.

- Bar-Adon, P. 1989. Mizpe Shalem. In, Bar- Adon, P. (ed.), Excavations in the Judean Desert. ‘Atiqot 9: 50–60.

- Ben-Itzhak, L. and Gvirtzman, H. 2005. Groundwater flow along and across structural folding: an example from the Judean Desert, Israel. Journal of Hydrology 312: 51–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2005.02.009

- Betts, A .V. G. 1992. Excavations at Tell Um Hammad 1982–1984. The Early Assemblages (EB I–II). Excavations and Explorations in the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Blake, I. M. 1966. Chronique archéologique: rivage occidental de la Mer Morte. Revue Biblique 73: 564–66.

- Blake, I. M. 1967. Dead Sea sites of the ‘utter wilderness’. The Illustrated London News, March 4: 27–29.

- Callaway, J. A. 1964. Pottery from the Tombs at ʿAi et-Tell. Monograph Series/Colt Archaeological Institute 2. London: Quaritch.

- Callaway, J. A. 1972. The Early Bronze Age Sanctuary at Ai (et-Tell). London: Quaritch.

- Callaway, J. A. 1980. The Early Bronze Age Citadel and Lower City at Ai (et-Tell). Cambridge, MA: American Schools of Oriental Research.

- Davidovich, U. 2012. The Early Bronze IB in the Judean Desert caves. Tel Aviv 39: 3–12. doi: 10.1179/033443512X13226621280462

- Davidovich, U. 2013. The Chalcolithic–Early Bronze transition: a view from the Judean Desert caves. Paléorient 39(1): 125–38. doi: 10.3406/paleo.2013.5491

- Davidovich, U. 2014. The Judean Desert during the Chalcolithic, Bronze and Iron Age (Sixth–First Millennia BCE): Desert and Sown Relations in Light of Activity Patterns in a Defined Desert Environment. PhD. The Hebrew University.

- Davidovich, U., Goldsmith, Y., Porat, R. and Porat, N. 2014. Dating and interpreting desert structures: the enclosures of the Judean Desert, southern Levant, re-evaluated. Archaeometry 56: 878–97. doi: 10.1111/arcm.12056

- De Vaux, R. 1951. La troisième campagne de fouilles à Tell el-Far’ah, près Naplouse. Revue Biblique 58: 393–430.

- De Vaux, R. 1955. Les fouilles de Tell el-Far’ah, près Naplouse. Cinquième campagne. Rapport préliminaire. Revue Biblique 62: 541–89.

- De Vaux, R. and Steve, A. M. 1948. La seconde campagne de fouilles à Tell el-Far’ah, près Naplouse. Rapport préliminaire. Revue Biblique 55: 544–580.

- Fujii, S. 1998. Qa’abu Tulayha West: an interim report of the 1997 season. Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 42: 123–40.

- Fujii, S. 1999. Qa’abu Tulayha West: an interim report of the 1998 Season. Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 43: 69–89.

- Fujii, S. 2000. Qa’abu Tulayha West: an interim report of the 1999 Season. Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 44: 149–71.

- Fujii, S. 2001. Qa’abu Tulayha West: an interim report of the fourth season. Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 45: 15–49.

- Fujii, S. 2002. Qa’abu Tulayha West: an interim report of the fifth season. Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 46: 19–37.

- Fujii, S. 2003. Qa’abu Tulayha West: an interim report of the sixth and final season. Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 47: 195–223.

- Fujii, S. 2011. ‘Lost Property’ at Wadi Qusayr 173: evidence for the transportation of tabular scrapers in the Jafr Basin, southern Jordan. Levant 43: 1–14. doi: 10.1179/007589111X12966443320738

- Getzov, N., Paz, Y. and Gophna, R. 2001. Shifting Urban Landscapes During the Early Bronze Age in the Land of Israel. Tel Aviv: Ramot Publishing.

- Gophna, R. 1996. Excavations at Tel Dalit: An Early Bronze Age Walled Town in Central Israel. Ramot: Tel Aviv University.

- Goren, Y. 1989. Ceramic technology and archaeological aspects. In, Bar-Adon, P. (ed.), Mizpe Shalem. Excavations in the Judean Desert. ‘Atiqot 9: 78–82.

- Greenberg, R. 2002. Early Urbanizations in the Levant: A Regional Narrative. London: Leicester University Press.

- Harrison, T. P. 1997. Shifting patterns of settlement in the highlands of central Jordan during the Early Bronze Age. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 306: 1–37. doi: 10.2307/1357546

- Kenyon, K. 1960. Excavations at Jericho. Volume One: The Tombs Excavated in 1952–1954. London: British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem.

- Kenyon, K. 1965. Excavations at Jericho. Volume Two: The Tombs Excavated in 1954–1955. London: British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem.

- Kenyon, K. and Holland, T. A. 1982. Jericho IV: The Pottery Type Series and Other Finds. Oxford: British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem/Oxford university Press.

- Kozloff, B. 1972. A brief note on the lithic industries of Sinai. Museum Ha’aretz Yearbook 15/16: 35–49.

- Manclossi, F. and Rosen, S. A. 2022. Flint Trade in the Protohistoric Levant: The Complexities and Implications of Tabular Scraper Exchange in the Levantine Protohistoric Periods. New York: Routledge.

- McConaughey, M. 2003. Chipped stone tools at Bâb edh-Dhrâʿ. In, Rast, W. E. and Schaub, R. T. (eds), Bâb edh-Dhrâ’: Excavations at the Town Site (1975–1981): 473–512. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

- Milevski, I. 2011. Early Bronze Age Goods Exchange in the Southern Levant: A Marxist Perspective. Approaches to Anthropological Archaeology. London: Equinox.

- Milevski, I. 2013. The exchange of flint tools in the southern Levant during the Early Bronze Age. Lithic Technology 38(3): 202–19. doi: 10.1179/0197726113Z.00000000021

- Mor, U. and Burg, A. 2000. Mitzpe Shalem Sheet 12-III. Geological Map of Israel 1:50,000. Jerusalem: Geological Survey.

- Müller-Neuhof, B. 2006. Tabular scraper quarry sites in the Wadi ar-Ruweishid region (N/E Jordan). Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 50: 373–83.

- Müller-Neuhof, B. 2013. Southwest Asian Late Chalcolithic/Early Bronze Age demand for ‘big-tools’: specialized flint exploitation beyond the fringes of settled regions. Lithic Technology 38: 220–36. doi: 10.1179/0197726113Z.00000000022

- Oren, E. 2001. Sharia (Tell esh-), Sera (Tel). In, Negev, A., and Gibson, S. (eds), Archaeological Encyclopedia of the Holy Land. 458–59. New York: Continuum.

- Paz Y. 2003. The Golan ‘Enclosures’ and the Urbanization Process in the Central and Southern Golan During the Early Bronze Age. PhD. University of Tel Aviv (Hebrew, English abstract).

- Perrot, J. 1961. Gat-Govrin. Israel Exploration Journal 11: 76.

- Philip, G. 2001. The Early Bronze I–III Ages. In, Adams, R. B. and Bienkowski, P. (eds), The Archaeology of Jordan: 163–232. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press.

- Philip, G. 2003. The Early Bronze Age of the southern Levant: a landscape approach. Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 16: 103–32. doi: 10.1558/jmea.v16i1.103

- Portugali, Y. and Gophna, R. 1993. Crisis, progress and urbanization: the transition from Early Bronze Age I to Early Bronze Age II in Palestine. Tel Aviv 20: 164–87. doi: 10.1179/tav.1993.1993.2.164

- Quintero, L., Wilke, P. and Rollefson, G. 2002. From flint mine to fan scraper: the Late Prehistoric Jafr industrial complex. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriential Research 327: 17–48. doi: 10.2307/1357856

- Rast, W. E. 2001. Early Bronze Age state formation in the southeast Dead Sea plain, Jordan. In, Wolff, S. R. (ed.), Studies in the Archaeology of Israel and Neighboring Lands in Memory of Douglas L. Esse: 519–33. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 59. Chicago: The Oriental Institute.

- Rosen, S. A. 1983. The tabular scraper trade: a model for material culture dispersion. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 249: 79–86. doi: 10.2307/1356563

- Rosen, S. A. 1997. Lithics After the Stone Age: A Handbook of Stone Tools from the Levant. Walnut Creek: AltaMira.

- Schaub, R. T. and Rast, W. E. 1989. Bâb edh-Dhrâʿ: Excavations in the Cemetery Directed by Paul W. Lapp (1965–67). Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

- Schick, T. 1978. Flint implements. In, Amiran, R., Paran, U., Shiloh, Y., Tsafrir, Y., Brown, R. and Ben-Tor, A. (eds), Early Arad: 58–63. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society.

- Shoh, Y. 2006. Cancelled Tools? Functions of Chalcolithic/Early Bronze Scrapers in the Southern Levant. Public lecture delivered at the Institute of Archaeology, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

- Turner, V. 1969. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. London: Routledge.

- Turner, V. 1982. From Ritual to Theatre. New York: Performing Arts Journal Publications.

- Turner, V. 1985. On the Edge of the Bush: Anthropology as Experience. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press.

- Wasse, A. and Rollefson, G. 2005. The Wadi Sirhan project: report on the 2002 archaeological reconnaissance of Wadi Hudruj and Jabal Thawra, Jordan. Levant 37: 1–20 doi: 10.1179/lev.2005.37.1.1

- Wilkinson, A. 1989. Jewelry beads. In, Schaub, R. T. and Rast, W. E. (eds), Bâb edh-Dhrâʿ: Excavations in the Cemetery Directed by Paul W. Lapp (1965–67): 302–10. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

- Yekutieli, Y. 2000. Early Bronze Age I pottery in southwestern Canaan. In, Philip, G. and Baird, D. (eds), Ceramics and Change in the Early Bronze Age of the Southern Levant: 129–52. Levantine Archaeology 2. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press.

- Yekutieli, Y. 2002. Settlement and subsistence patterns in North Sinai during the fifth to third millennia BCE. In, van den Brink, E. C. M. and Levy, T. E. (eds), Egypt and the Levant, Interrelations From the 4th Through the Early 3rd Millennium BCE: 422–33. London: Leicester University Press.

- Yekutieli, Y. 2004a. The desert, the sown, and the Egyptian colony. Ägypten und Levante 14: 163–71.

- Yekutieli, Y. 2004b. Landscape of control: an Early Bronze Age ascent in the southern Judean Desert. Ancient Near Eastern Studies 41: 5–37. doi: 10.2143/ANES.41.0.562919

- Yekutieli, Y. 2006a. Is somebody watching you? Ancient surveillance systems in the southern Judean Desert. Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 19: 65–89. doi: 10.1558/jmea.2006.19.1.65

- Yekutieli, Y. 2006b. Aspects of an Early Bronze Age II–III polity in the Dead Sea region. In, Bienkowski, P. and Galor, K. (eds), Crossing the Rift: Resources, Routes, Settlement Patterns and Interaction in the Wadi Arabah: 103–24. Levant Supplementary Series 3. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Yekutieli, Y. 2009. The Har Hemar site: a northern outpost on the desert margin? Tel Aviv 36: 218–40. doi: 10.1179/033443509x12506723940811

- Zutovski, K. and Bar, S. 2017. Canaanean blade knapping waste pit from Fazael 4, Israel. Lithic Technology, DOI: 10.1080/01977261.2017.1347337.