Abstract

SUMMARY: This paper examines the contemporary role of the gravedigger, their day-to-day working practices, and how these tasks can impact the archaeological record. The study was undertaken through conducting semi-structured interviews with 16 practising and recently retired gravediggers from in and around Bristol. These interviews revealed that gravediggers not only dig graves but also facilitate funerals, bury coffins, reopen graves for subsequent burials, exhume human remains and curate material culture both within the graves and around the grave plots. The gravediggers also perform important emotional labour in their interactions with the dead and with their families. This evidence demonstrates that gravediggers heavily impact the archaeological record in cemetery contexts and play an important part in the social organisation around funerary practices in the British Isles. Although this role has likely changed considerably over time, these interviews still demonstrate that present-day archaeologists must consider the role and impact of gravediggers when analysing post-medieval cemetery landscapes. In addition, this information can act as guidance for future archaeologists when excavating cemetery sites and churchyards.

INTRODUCTION

The ways in which people handle and commemorate their dead is fundamentally important in understanding the culture and society in which they are embedded in both the past and present (Parker-Pearson Citation1993). The role of the dead and how they are treated also has a great impact on the living. It has been recognised that the treatment of dead bodies intersects with the role of gender, class, religion, and ontological conceptualisations of death (Parker-Pearson Citation1993). Furthermore, dead bodies can act with considerable social agency and can have active ‘political lives’ (Verdery Citation1999). Archaeologists have expended considerable time and effort to understand the role of death, funerary processes, and dead bodies due to their role in reflecting and informing the norms of the groups they exist within.

The study of death and dying has prompted the creation of many sub-disciplines in the field of archaeology. ‘Funerary Archaeology’ has become an umbrella term encompassing a wide range of archaeological fields: to name a few, osteoarchaeologists and bioarchaeologists analyse human remains in anatomical detail to uncover the link between biology and culture; Archaeothanatologists uncover information regarding the taphonomy of bodies and necrogeographers interpret the spatial and cultural elements of the mortuary landscape (Duday, Capriani and Pearce Citation2009). Additionally, historians, genealogists and historical archaeologists employ a wide range of documentary and material culture evidence in order to understand cemeteries and their inhabitants within their shifting socio-economic contexts over time (Alaimo Pacyga Citation2023).

Post-medieval archaeologists however do not seem to have acknowledged one of the most significant roles in the deposition of the dead, the gravedigger. Instead, documenting the gravedigger’s role has been left to popular literature (Shipley Citation2009, Citation2022). This oversight is perhaps most self-evident in the common assertion that ‘the dead do not bury themselves’. This saying is usually taken to mean that it is the living, in the sense of the deceased’s kinship group and wider community, who exercise the most agency in this process, rather than the final wishes of the deceased themselves. This interpretation ignores the gravedigger, whose as it will be shown here plays a significant role in deciding where the body will be laid to rest who is the final living person to physically interact with the coffin, and who curates the grave goods and wider burial landscape long after the bereaved have ceased to visit. Therefore, if archaeologists wish to understand burial practices and wider relationships with death in the post-medieval period, the role of the gravedigger cannot be ignored. The purpose of this study is therefore to describe gravediggers’ roles and impact on the archaeological record in detail, in order to centre them within post-medieval funerary archaeological discussion and thereby assist contemporary and future archaeologists in better understanding cemetery landscapes.

Understanding the daily working practices of gravediggers is vital to archaeologists if they are to fully grasp and understand the archaeological record at cemetery sites now and in future. It is actually gravediggers themselves who are ultimately responsible for the organising and planning within the cemetery landscape, deciding (with local managerial oversight) where each grave plot should be located. They are also the ones who dig the graves, using knowledge gained experientially and through word of mouth to do so safely and at scale. They also possess the experience and knowledge of particular site conditions, including any problematic areas to be avoided. Altogether gravediggers and their activities have been to date excluded from the archaeological discourse, a surprising omission as it is they who are quite literally making the cuts and fills which will be excavated by future archaeologists.

This project will therefore present gravediggers’ own accounts of their day-to-day practices and relate these to the impact of their activities on the archaeological record. It will be argued that it is vital for post-medieval archaeologists to consider the role of gravediggers in their own interpretations of cemetery landscapes. This practice includes, but goes beyond, the purely physical impact of the gravediggers’ work activities upon the archaeological record, to include also the intangible socio-cultural and emotional dynamics which have profoundly shaped the cemetery landscape over time (Barnard Citation1990; Reimers Citation1999; Strange Citation2003; Buckham Citation2003; Francis, Kellehar, and Neophytou 2005; Rugg Citation2013; Parker and McVeigh Citation2013; Maddrell and Sidaway Citation2016; Sprackland Citation2020). While some of these dynamics directly and clearly impact the future physical record, others do not always leave an obvious physical trace; however the latter are also included here, in acknowledgement of the equal importance of the cemetery’s intangible cultural heritage (UNESCO Citation2024). Thus future archaeologists are invited to consider cemeteries holistically as social, emotional and spiritual, as well as physical spaces.

Future archaeologists can also use the information presented in this study to integrate the gravedigger’s perspective into their methodologies when excavating post-medieval cemeteries. This means taking into account the ways in which gravediggers typically impact the archaeological record. Alternatively, if the archaeological evidence appears to contradict the gravedigging practices known to have been typical, then archaeologists may be able to determine the reasons for such variation. Additionally, the description within this study of the intangible, emotional and socio-cultural techniques and behaviours of the gravediggers will enable future archaeologists to engage with concepts such as Geertz’s ‘thick description’ (Geertz Citation1973) in their interpretations. This will in turn allow cemeteries to be fully recovered as not only physical, but also emotionally charged landscapes of mourning and commemoration.

THE ROLE OF GRAVEDIGGERS IN CEMETERY STUDIES

In order to understand the role of the gravedigger both historically and today in the British Isles it is important firstly to understand the changing nature of burials and the associated changing role of gravediggers.

Christianity became the dominant religion in the British Isles from the seventh Century AD, and with it inhumation the preferred means of disposal of the deceased, often taking place in formal graveyards next to the church building (Daniell and Thompson Citation1999, 76–77). There is some literary and pictorial evidence of gravediggers during the Middle Ages and beyond; perhaps most famously, the clown-like gravediggers in Shakespeare’s Hamlet (Shakespeare Citation2003, 188–197). There are also pictorial depictions from the 1450s of bodies being buried (Memphis Brooks Museum of Arts 2022), and from the post-medieval period (Dalziel 19th cent.; Butler Citation1832; Holman Hunt 1865, Schwabe Citation1895). As well as digging graves, the role of a medieval sexton could include ringing the church bells, locking and unlocking the church building, and even looking after the choir books (Orme Citation2021, 83).

Burial remained the predominant method of disposing of the dead throughout the medieval and into the post-medieval period (Daniell Citation1998). However, the nature of living and therefore death changed drastically during this period. The process of urbanisation following the industrial revolution had a major impact on the demography of the British Isles, with both a rapidly increasing population and large numbers moving from the countryside to cities (Rugg Citation1999, 215–220). This urban population boom compounded by poor sanitary infrastructure led to major mortality episodes such as the cholera epidemics of 1831–1832 and 1848–1849 (Rugg Citation1999, 216–217). This in turn led to overcrowding of the churchyards, as highlighted by George Alfred Walker in his 1839 Gatherings from Graveyards report. Although written for dramatic effect, Walker’s work succeeded in drawing public attention to the state of the over-crowded inner-city cemeteries (Rugg Citation1999, 220). The point was further emphasised by Edwin Chadwick’s 1842 report The Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population which described the poor working conditions in overcrowded urban church graveyards and cited these as a significant cause of moral and physical degradation for gravediggers (Chadwick Citation1842). Chadwick’s report also described, though briefly, some working practices at the cemeteries and interviewed several gravediggers (Rugg Citation1999, 220). Eventually reforms, beginning in the 1840s, allocated the responsibility for cemetery operations to localised, mainly secular Burial Boards, including the authority to open their own sites (Cemeteries Clauses Act Citation1847). These new sites were usually constructed in the semi-rural suburbs and were often landscaped in line with an emerging aesthetic of naturalistic landscape design (Loudon [Citation1843] 2019; Penny Citation1974; Curl Citation1975, Citation1980, Citation1983, Citation2000; Brooks Citation1989; Tarlow Citation2000; Jones Citation2007; Udall Citation2019). These new garden style cemeteries may or perhaps may not have engendered changes in gravedigging practices, but again this is yet to be researched in any depth or detail.

The practice of cremation rapidly rose to prominence from the late nineteenth century and into the twentieth century, amidst an increasingly secularised climate and a concerted effort by certain medical experts to encourage cremation as being more a economical and hygienic practice than burial (Jupp Citation2006, 46–70). The Cremation Act 1902 legalised cremation in Great Britain, and thence cremation gradually increased in popularity until it overtook burial as the most popular method of disposal after World War Two (Jupp Citation2006, 125–156; Jupp and Walter Citation1999, 264–266). This impacted grave digging practices in terms of a shift from burying coffins toward burying urns and scattering ashes (Jupp Citation2006). Natural burials have also increased in popularity since the 1990s with c.200 natural burial sites in operation by 2011 (Davies and Rumble Citation2012, 1–2). This has also impacted cemetery management practices, with some sites allocating space for this type of burial, and has also impacted grave digging practices with the planting of trees over graves instead of headstones, and alternative ways to dig graves and pile spoilFootnote1 being developed (Davies and Rumble Citation2012, 19–37; Hockey et al. Citation2012).

Multiculturalism has been another recent, important influence upon burial practices. Increased levels of migration have resulted in faith groups other than Christianity now making up a significant proportion of the British population. This in turn has caused shifts in funerary practices reflecting the religious and cultural requirements of these groups (Panayi Citation2010, 37–45). The specifics of this impact on the role of the gravedigger, and their experiences in navigating these cultural differences has also not been researched. Here again is why the experiences of gravediggers are important to record.

It is also important to consider that, due to the increasing mechanisation of gravedigging processes, the individuals interviewed in this study are likely to be one of the last generations of gravediggers for whom hand-digging graves is the norm. This means that it is essential for archaeologists to record the gravedigger’s day-to-day practices and the impact of these upon the archaeological record of cemeteries. Furthermore, due to the length of time that ‘gravedigger’ has been a defined role this fact is likely to be relevant to a large range of archaeologists studying different periods.

Within the wider field of cemetery studies since the 1970s, an abundance of research had been carried out on the nature and uses of cemeteries, their development over time and the role of material culture (Penny Citation1974; Curl Citation1975, Citation1980, Citation1983, Citation2000; Brooks Citation1989; Rugg Citation1998a, 1988b, Citation2000; Worpole Citation2003; Johnson Citation2008; Sørenson Citation2009; Woodthorpe Citation2011; McClymont, Citation2016). There is even a Museum of Sepulchral Culture in Kessel (Germany) which focuses on topics of dying, death, burial, mourning and remembrance (www.sepulkralmuseum.de). However frontline cemetery staff have largely been absent from this discourse, with any academic attention tending to be negative (Saunders Citation1995; Hussein & Rugg Citation2003). One seminal study focusing on the ‘below-ground’ changes of a cemetery landscape was conducted by Anthony (Citation2016) in Assistens Cemetery, Copenhagen. This comprehensively charted the practices at a modern Danish cemetery and the related archaeological footprint that is left by different activities. Anthony found that gravediggers did indeed leave a considerable impact on the funerary record and exercised significant autonomy in deciding both day-to-day and long-term changes to the cemetery (Anthony Citation2016, 283–338). Also in a Danish context, Nielsen (Citation2021) has concluded that gravediggers play a significant role in customers’ grave plot choices. However no comparable, nor comprehensive studies have yet been conducted in the UK. The Assistens study also raised several questions about gravedigging practices which require clarification. For example, do gravediggers intentionally manipulate previously buried individuals or is this the incidental byproduct of other work activities (Anthony Citation2016, 175)? This project will seek to answer these questions and focus more explicitly on the gravediggers’ own experiences.

METHODOLOGY

For the study, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 16 working and retired gravediggers, plus a member of administrative staff and a first-level manager for the City of Bristol Burial Authority. The Burial Authority operates and maintains seven garden-style cemeteries, together with one modern lawn-style cemetery: Arnos Vale, Greenbank, Avonview, Shirehampton, Canford, Brislington, Ridgeway Park, Henbury (all garden style cemeteries opened between 1836 and 1920 and inherited from previous operators) and South Bristol (a lawn style cemetery opened in 1972Footnote2 by the then-named Bristol Corporation). The latter remains the main working cemetery for Bristol today, while the rest either only accept re-openers,Footnote3 or do not allow any new burials at all but still require maintenance. Several of the gravediggers interviewed also worked in the Burial Authority’s crematoria. The gravediggers interviewed possessed occupational experience ranging between a few months to over 30 years. This means the more experienced gravediggers could recall information dating back to the 1970s and beyond. The interviewees were questioned about five key stages of the gravedigging process: selecting a burial plot; digging out; ‘taking a grave’Footnote4 on the day; site maintenance; and finally, re-openers and exhumations.Footnote5 Additionally, interviewees were asked about the emotional labour they carried out, in order to capture the lived experience of working with dead bodies and with the relatives of the deceased. These oral histories and the burial practices disclosed therein are then considered and explored in relation to their impact upon a cemetery’s archaeological record, both for the present day, and for the benefit of future archaeologists. Autoethnographic contributions supplied by Dr. Stuart Prior, who, as well as originating the project, worked as a gravedigger for Yeovil Town Council for six years at Yeovil District Cemetery on Preston Road in the 1980s, will also be included.

The semi-structured interviews and autoethnographic methods were chosen in order to foreground the gravediggers’ voices and day to day practices. By using interviews, this voice can be presented directly. Interviews were also chosen because traditions of gravedigging practice are often transmitted orally as learned ‘on the job’. Thus a purely textural analysis would be likely to miss out on a great deal of key information including the less tangible, affective aspects of the role. By using interviews all of these aspects of gravediggers’ daily working practice can be captured.

Documents outlining burial practices will also be referred to in order to incorporate the relevant legal requirements, together with best practices for cemetery management as codified by the industry itself. The Local Authorities’ Cemeteries Order (hereafter LACO) 1977 is the most comprehensive piece of burial legislation and will be used to refer to gravedigger’s legal obligations. This is important to consider in this study as gravediggers cannot undertake their duties without explicit knowledge of and working in relation to these guidelines. However, due to the sometimes amorphous nature of the task descriptions within LACO, in reality gravediggers have to interpret them and create their own practices and guidelines for specific aspects of their work. The Institute of Cemetery and Crematorium Management (hereafter ICCM)’s 2014 Charter for the Bereaved will also be referenced in order to include the industry’s collective understanding of its own best practices.

RESULTS

SELECTING A BURIAL PLOT

LACO (1977, s.10) confers upon Burial Authorities the right to grant exclusive rights of burials in a specific plot, and the ICCM Charter states that ‘it may be possible to select the location of the grave’ (ICCM Citation2014, 11). However, neither details how this process should function. This means the cemetery staff must handle the sensitivities of the grave. The interviewees all attested to a potential conflict that can arise when the bereaved mistakenly believe that the grave plot is being purchased ‘in perpetuity’, rather than that they are simply paying for the right of interment for a fixed period of time. This can create a difficult situation for the gravediggers, many of whom described needing to manage the expectations of the bereaved parties in this regard in an emotionally sensitive way. If they do not, this can create difficult situations in the future wherein there can be conflict between the bereaved and gravediggers about managing the burial plot. The gravediggers also all displayed understanding that this potential conflict between the bereaved and cemetery staff could lead to formal complaints and negative publicity in the media, and thus damage to the service’s public reputation.

Detailed recording of grave locations and occupants is a legal requirement (LACO 1977, s. 11). Burial plots antedating 1977 can therefore be located with relative ease, since accurate records of who is interred where are generally readily available. Historical records, however, are often incomplete, especially at older cemeteries, where record keeping was often more ad hoc and indeed records have sometimes been lost altogether. Hence our interviewees stressed the importance of experiential site knowledge gained orally from colleagues. This ‘learning on the job’ imparts on new gravediggers the relative locations of key grave plots that are not adequately recorded in the site archives. It also enables topographical knowledge to be shared about the site itself, including where bedrock, thick tree roots, high and low water tables, and potentially troublesome areas of animal activity, such as rabbit burrows or badger setts, are all located.

‘Yeah, yeah, I can still remember different things about the cemetery. Even ones years ago you just get to know and you just remember things like that.’

The ways in which grave plots are laid out and selected varies in different types of cemeteries. Lawn cemeteries are typically laid out in a fan shape proceeding from the section corner. This both maximises the number of grave plots that can be laid out, and allows heavy items such as portacabins and JCB diggers to be kept on stable, un-dug land. In garden cemeteries, grave plots are laid out alongside walkways and selected by customers on an ad hoc basis. In both cases a vital part of the staff’s duties is taking prospective customers on a guided walk around the cemetery and encouraging them to pick a plot from a pre-chosen group based on (in order of priority) safety concerns, ease and efficiency of digging and customer preference including any economic factors. These attributes presented and suggested by the gravedigger are certainly an important aspect of why the customer buys a grave plot (Nielsen, Citation2021). However, several gravediggers described how some customers also had more personal reasons for their choices.

‘Sometimes people will come and choose the little plot they want to put their ashes (or indeed have a burial). A lot of men will say “We want it just near the City Ground.” That he was a City fan and somebody wanted to see Ashton Court. Some want to see the suspension bridge. Everybody’s different. Everybody’s different.’

The selection of a grave plot, then, is a decision mediated by two actors, the customer, and the gravedigger. This demonstrates the considerable agency that gravediggers possess, in addition to the customer’s choice, in determining where graves should be dug and subsequently how the wider cemetery landscape develops. Several gravediggers also suggested that at certain cemeteries customers were given less agency to choose and buy their plot.

‘Well you can buy future use graves as such. But I think they are probably trying to put a stop to that because if you imagine that is the plot where the graves are and there are all kind of graves there. If you buy one, if you choose in the middle, all the rest get used years down the line someone has got to come in and dig that possibly by hand because you can’t get the digger in with all the headstones around.’

This demonstrates that the increasing adoption of machine digging in recent years has led to increased management of the customer’s choice of grave plot, and thus the increasing influence gravediggers now exercise upon the overall lay-out of the cemetery landscape. Future archaeologists should therefore consider these intangible, and to date poorly recorded, dynamics of the gravedigger’s day to day work when interpreting burial grounds.

Several of the interviewees also attested to the role that cultural and religious practices of the bereaved play in selecting an appropriate burial plot. These included specific areas for Muslim, Chinese and Polish individuals. Though most of these areas were known by the ethnicity of the groups that were buried there, e.g. ‘The Polish area’ or the ‘Muslim area’, many were known by their given letter code. At the studied cemeteries, the word ‘Muslim’ itself was avoided by the gravediggers in the belief that saying the word would mean the immediate (because Muslims require same-day burial) requirement to dig a grave. While one or two pre-dug graves are, in an example of skilled anticipation, usually kept ready, gravediggers may still be required to work overtime in order to meet a sudden demand. In several of the cemeteries the exclusion of certain words in relation to the planning of grave plots are also extended to violent words. For example, in one cemetery each area is designated an alphabetical letter, but the letter ‘K’ is excluded from this. The gravediggers explained this is because the letter K was seen to represent the word ‘kill’ and so was therefore bad luck. This evidences the existence of a rich set of unwritten occupational oral traditions which interact with the physical structures of cemetery landscapes.

DIGGING OUT

‘It’s hard to explain just how difficult and physically demanding the digging outFootnote6 and backfillingFootnote7 of a grave actually is. It takes an enormous amount of effort and energy to cut the sod, remove the turf and begin digging down, all the while checking that you have the dimensions of the grave cut correctly and that the sides of the grave do not begin to slope-in the further down you dig. It’s also difficult to capture in words the feeling of those early morning bitter cold winters, where your hands are frozen solid and you actually relish digging just to warm up a little on those freezing cold frosty mornings, or indeed the sweltering summers where the sunshine is relentless and the dust and hay-fever atrocious, but where you can take shelter in the bottom of the grave-cut out of the heat for the sun for a while. Then there’s the humid autumns, where you can’t decide which clothes you should be wearing, because you’re too hot one moment and too cold the next, and you frequently remove your jacket to dig, only to don it again a few moments later when the heavens open and you are soaked to the skin. At times like these it’s better to be at the bottom of the grave out of the wind and rain, leaving your digging partner (banksman) exposed at the top of the grave to shovel away the discarded spoil. Before limitations were imposed upon the depth of grave cuts, standing 9 or even 12 feet down at the bottom of a grave with a patch of coffin-shaped sky above your head, with no way out but a long ladder, was troubling, but also part and parcel of your hard day’s work.’

This quote typifies something articulated by all of our gravedigger interviewees; the raw physical exertion of digging out a grave. The weather also presents a challenge with extreme heat and cold making the task both more exhausting and presenting physical challenges such as the ground hardening in the cold in winter. Several of the gravediggers also attested to the surreal sensory experience of digging at the bottom of a grave due to the darkness with the only light provided by a coffin shaped hole between 6 and 12 ft above.

The law requires that coffins are interred no less than three feet below the surface (or two feet if the coffin is of ‘perishable material’) below the ground surface. It also requires at least six inches of soil to be placed vertically between each internment (LACO 1977, schedule 2 (2–3); see also Rugg Citation2013, 386–388). Despite this, several of our interviewees stated that these laws were insufficient for their day-to-day processes of grave digging. This means that processes of learning on the job and the experience shared by word of mouth is essential, as well as the ability to skilfully anticipate any potential problems. Since the 1950s, the standard depth of a grave in Bristol cemeteries has been 6 ft 3 inches deep (6'3") (Bristol Cemetery Committee Citation1954–1963, 24; ICCM Citation2014, 13) which the gravediggers call a ‘new for two’ (the grave being cut deep enough to accommodate two coffins). Historically, however, graves were often excavated to depths of 12 ft or even more, at significant physical risk to and emotional toll upon the gravedigger.

Hard ground and bedrock are also problems frequently encountered when digging a grave, hence why in December 1933 the Bristol burial authority agreed to trial mechanical drills in an effort to tackle this problem (Bristol Cemetery Committee Citation1927–1940, 236–237, 239). Drills and other jackhammers are still frequently used to break hard ground. Several gravediggers also recalled accounts of past gravediggers using explosives to break bedrock and hard ground. Though none of the gravediggers had ever personally done this, the ‘time when’ narrative was recounted with confidence and nostalgic pride, evincing shared professional values of autonomy and skill accumulated through collective experience over time.

‘Well that was, you go out with the older blokes or the more experienced ones and they teach, one thing I will say is that they did certain aspects of it they did teach me very well I must admit like doing a hand grave which they taught me to do the ribbing,Footnote8 they taught me how to do it properly and I think that’s good as I taught two blokes where I work now at Canford to do the ribbing. I’ve showed them exactly how I did it, so I said to them if I show you how to do it properly, whether you do it properly after I’ve showed you is entirely up to you but I’ve shown you how to do it properly.’

The material culture used to dig graves is very similar to that used historically (for example see ‘Old Scarlett’ AKA Robert Scarlett (d.1593), a gravedigger at Peterborough Cathedral whose memorial monument depicts the tools of his trade such as spades, shovels, picks and mattocks (). These tools are often modified for the specific task of digging graves. For example, wooden shafts are frequently removed from shovels and metal shafts added, whilst still retaining the wooden handle, in order to cause the shovel to become warmer with the user’s body heat and so make it easier to use in cold weather.

FIG. 1 Tools used for digging out graves. Several of these have been modified, for example by the addition of elongated handles.

‘What you do is doctor the handles if they’re wood, and put a metal bar in and keep them like that’

‘years ago when I first started, you’d see all these blokes with these metal shovels and that and you think oh I bet that’s cold. Then you’d have this wooden one and you’d be cold all day long with your gloves on, and they’d be all suddenly with no gloves on. You’d think what’s going on there.’

Shovel handles can also be extended, in order to make it easier to shovel spoil out of deep graves, whilst small spades and shovels are employed to dig the little graves required for child burials. Specially made wooden or metal boxes are employed to store the spoil. Wooden, metal and hydraulic sidings (akin to ribbing) are used to stop graves from collapsing, in addition to ‘grave frames’, which are coffin shaped metal frames that are inserted into a grave after it is opened to ensure that it keeps its shape as digging continues downwards (). Metal grave lids have also been created by gravediggers to prevent people and animals from falling into open graves (). Custom ‘headstone boxes’ have additionally been fashioned to fit over headstones when using a JCB digger to avoid damaging the surrounding headstones (). Thus the gravediggers demonstrated an in-depth understanding of certain practical problems that are frequently encountered when digging a new grave, and have created customised items of material culture in order to resolve these issues.

Hand-dug graves are usually cut from the head end outwards. Since lawn cemeteries are usually arranged in a fan shape, the spoil can be placed on the grave’s unused side in a specially made box. This assists in preventing grave collapse and helps the cemetery look less industrial by avoiding the visible display of large piles of spoil (a frequent complaint of visitors when a new grave is cut). If a new grave is cut on a plot without space next to it, the spoil will have to be placed on a neighbouring grave plot. While the ICCM Charter for the Bereaved attempts to manage the expectations of cemetery visitors in this respect (ICCM Citation2014, 13–14, 71–72) several of our interviewees attested to this as a particular point of complaint by families.

‘90% of people don’t like that at all but it’s got to be done like you know I mean there are times when we can take it all away, there are times when we do take all the soil away but we can’t do that every single time otherwise you could spend half the day just moving soil and doing nothing else you know, we do try and, again if we look on their headstone and we see there’s an anniversary coming up or they died on that day’

To mitigate this, gravediggers typically attempt to avoid doing this on popular visiting days such as the anniversary of the death and on public holidays.

There is no legal guidance in when and how to shore up the grave-sides to prevent collapse, the risk of which our interviewees evinced a keen appreciation. In the absence of legislation, or of specific industry guidance (ICCM Citation2014, 13, 73–74) gravediggers have therefore developed their own methods of mitigating the risk of injury to themselves or for visitors to a grave in case of collapse. This first requires proficiency in detecting the first sign of collapse, working in pairs with one acting as banksman.Footnote9

‘after five years of working in the job I had a serious accident at work, where I was buried alive in a grave! This happened after a wet Bank Holiday weekend in August, where upon my return to work the side of a grave I had been digging collapsed and took me down with it, and the shoring fell in on top of me, which dislocated my right leg. It took over an hour to dig me out of the grave, and I was on crutches for around six months afterwards.’

Once the grave is fully dug a coffin shaped grave frame is placed into the hole in order to ensure that the cut grave keeps its shape. After this a lockable lid is placed over the grave to prevent any person or animal falling in (ICCM Citation2014, 13). This is another example of the workers’ skilled anticipation of potential problems, and in resolving them with innovative intangible and tangible working practices; some of which leave physical traces in the archaeological record but others of which have been unrecorded until now.

Several of the gravediggers also explained how the gravedigging process varies due to varying cultural and religious requirements. For example, when digging Muslim graves, a wooden ‘tomb’ inside the grave cut ensures that no soil can touch the coffin when it is placed within the grave. This demonstrates the gravediggers’ thorough understanding of the funerary practices of different cultures, and the measures taken to cater for them which leave varying degrees of physical trace behind.

‘What we do with them see is we build boxes, because there’s only one burial in there, so we build a box by four foot wide, and drill walls around it. Put a bead in the middle of it and what happens is then the coffin gets lowered in the ground, then they put a board on top where we put the beading around. Then they fill it with soil. It’s just the way how they do it.’

A similar underground ‘tomb’ is often constructed for GRT (Gypsy, Roma, Traveller) people, though usually made from brick and built inside the grave-cut by a skilled bricklayer or mason (ICCM Citation2014, 19). These graves are built to contain a single individual, and possess a much larger than normal profile in order to accommodate all the brickwork.

Increasingly, the digging of graves has been subject to mechanisation, a process which as noted above began in Bristol during the 1930s, and has accelerated since the 1980s. Graves are now mainly dug using JCBs and other mechanical diggers, except in older cemeteries where the rows of graves are too narrow and/or the monuments too elaborate to fit mechanical diggers between plots without (often prohibitively expensive) specialist equipment. When graves can be machine dug, a (usually) 36-inch bucket is employed to evenly cut an appropriately sized hole for the coffin according to the specifications sent by the funeral director. This means that, as standard, gravediggers are now provided with training to obtain a machine driver’s (CBT) licence. This use of machinery is rapidly becoming the default way of digging graves, due to the increased speed and ease of use. Consequently, gravediggers who have been in the job for less time tend to see this technique as the norm, while older gravediggers possess much more experience of hand-digging graves.

‘I mean, nowadays they think, don’t quote me, that most are just dug for two now. Six foot, and it is done with a digger now isn’t it? A JCB or a mini digger, where when we done it back in the ‘80’s it was all hand dug.’

‘So it’s a little bit easier now than what we had it in our day.’

The hand-digging of graves is, however, still viewed as a rite of passage in the job. Hand-digging can be safer and is frequently employed when digging re-openers and exhuming bodies, and/or in legacyFootnote10 cemeteries. Overall, gravediggers have developed a highly sophisticated set of methods for safely and efficiently digging graves based on experiential knowledge. This consequently will have a significant impact on the archaeological record of cemeteries as it creates the cuts and fills which may later be excavated by archaeologists.

TAKING A GRAVE

On the funeral day itself, gravediggers must carefully navigate the often conflicting roles of presenting to the public an appearance of decorum and respect on the one hand, whilst also concerning themselves with the very practical considerations of managing a crowd of people and of safely moving a large heavy item around the site (the coffin) and into the ground, despite any adverse conditions.

Before the funeral party arrives the grave cover is removed, and any remaining safety checks are undertaken. Due to the high-water table at several of the sites covered by this study, accumulated water may need to be bailed out. Remedial fill may also need to be shovelled out. Several of the interviewees also recounted stories of last-minute issues needing to be resolved before the funeral parties arrived. One example was a grave which had been dug in the wrong place, and so the gravediggers had to quickly dig out a new one just before the party arrived. This illustrates the importance of maintaining an appearance of decorum and quiet dignity regardless of the logistical problems that may arise ‘behind the scenes’. Grass mats are then placed around the grave to cover the disturbed, muddy ground (ICCM Citation2014, 12, 14; Frisby Citation2019, 117). This practice gives material expression to the intangible emotional labour performed by the gravediggers in order to render the experience as easy as possible for the bereaved, in this case by mitigating through disguise the gross materiality of the grave. The same effect is also achieved by placing wooden planks by the graveside, which also provide stable footing for the coffin-bearers (ICCM Citation2014, 14). The gravediggers change into ‘smart’ clothes in order to show dignity and respect (ICCM Citation2014, 14). Several of the interviewees described the high stakes involved in performing the funeral to a high aesthetic standard, given the potential for upset and complaints. Normally a gravedigger greets the funerary party and cross-checks the paperwork with the funeral director. They then guide the coffin bearers toward the correct grave (ICCM Citation2014, 14). Several of the gravediggers described the importance of emotional labour at this point, in comforting the families.

Our interviewees recounted several occasions where problems and accidents had occurred at this point in the proceedings, and described the frequent use of humour to defuse such situations. While this could be a risky strategy were the humour to be perceived as insensitive and upsetting, the following recounts an occasion upon which it succeeded in easing an otherwise difficult situation:

‘There was a time we was down the crematorium and he said, “where’s the vicar?” And he said, “I left him in the pub. I thought he was coming with someone else”. “No”, he said, “go and get him”. So he jumps in the hearse, off he goes, the coffin comes straight out the back window, drops on the floor. God it was hilarious.” “They were laughing their heads off. It was just hilarious. They picked it up and put it in’

The gravediggers then remain on standby throughout the proceedings, usually standing to one side and making an effort to remain inconspicuous (ICCM Citation2014, 14). To begin proceedings at the graveside, the coffin is rested on top of putlogs (wooden spars) at the end of the grave. Webbing or tape is then slid through the coffin handles, and the bearers lift the coffin. The putlogs are then removed, and at a pre-agreed signal the bearers step up to the grave and slowly lower the coffin into the grave itself (ICCM Citation2014, 14). Several of the gravediggers described the fear at this critical moment of a ‘sticky’—the coffin becoming stuck partway down into the grave whilst being lowered. In October 1934 Bristol’s Town Clerk submitted to the Cemetery Committee ‘a letter from Mr. A.J. Davey in which he complained that when his wife was buried at Avonview Cemetery the grave was not large enough and a grave digger jumped on the coffin and was handed a crowbar to use as a lever to get the coffin down into the grave’ (Bristol Cemetery Committee Citation1927–1940, 274). While neither the original complaint nor the Town Clerk’s response following the Committee’s discussion can be located, this minute nonetheless hints strongly at the distress and embarrassment such incidents can cause. Our present-day gravedigger interviewees were inclined to blame funeral directors for supplying incorrect coffin measurements, and stated how, as a preemptive measure, it was customary to dig out extra grave space as a preemptive measure; an intangible piece of collective professional experience which will have left physical traces in the form of graves dug slightly too large for their occupants.

After the ceremony the grave is then immediately backfilled, usually by the gravediggers (ICCM Citation2014, 14). This can take up to two hours depending upon the soil type. That said, some cultural groups (notably the Afro-Caribbean community, Muslim, Plymouth Brethren and GRT) prefer to backfill their own graves as a tribute of affection and care for the deceased (ICCM Citation2014, 14, 46, 74). Depending on the quality of backfill this practice may or may not subsequently be apparent in the archaeological record; however what these cases do—again—exemplify is the gravedigger’s critical, yet often intangible professional role as an emotional facilitator. At Muslim burials furthermore, often the mourners open the coffin and change the body’s position to face East. This sudden, unsolicited confrontation with a dead body can be distressing for gravediggers, for whom a distance from the gross materiality of death—exemplified by the comment that ‘I bury boxes not bodies’—is a necessary emotional boundary which enables them to perform their professional roles.

However it is the performance of children’s burials at which the gravedigger’s role as emotional, as well as physical, labourer comes most to the fore. This task is described by gravediggers as being especially emotionally taxing, from digging the grave to apprehension about assisting on the day:

‘I know a guy who’s retired now you’ll find it’s usually the baby funerals that tend to upset people more than anything and I know one of the chaps now, he’s retired a few years back now, again he started there the same time as me within a month, and one of the baby funerals the vicar didn’t lower the … he didn’t want to lower the coffin; he asked my colleague to carry the coffin down the stairs because we’re 20 odd stairs below ground, the crematory at Canford, and he just carried the coffin down and he broke down. And that was it for him. That was like … if the coffin was lowered he said he’d have been fine but because he had to physically then get involved and ‘yeah, alright, I’ll carry it down’. He said that was enough for him then, it made him realise, I suppose, what it was all about.’

Only the grave cut, and perhaps even some vestiges of a tiny coffin, will be evident to future archaeologists; the diminutive nature of these physical remains belying the amount of intangible emotional labour on the part of those who dug the grave out and placed the coffin at the time.

Another type of burial which diverges from a standard grave burial, in both its tangible and intangible aspects, is the use of crypts. In these situations, a gravedigger must climb down inside the crypt itself ready to receive the coffin. This is often described as being a deeply unpleasant and difficult job to perform, since the gravedigger is crouched for a long time in a foul smelling, dark place very physically close to decomposing bodies in their coffins. When the new coffin is lowered in, the gravedigger must reach out and pull the coffin into the crypt between their legs. Several of our interviewees recounted a ‘time when’ story of the funeral party not realising that someone was in the crypt, and therefore becoming scared upon seeing hands reach out of the crypt to take the coffin. It has therefore now become standard practice to brief the bereaved beforehand about what to expect—another example of emotional management.

Gravediggers also play a key role in the curation of any material culture which may be placed into the grave. The interviewees all attested to mourners throwing flowers, money, clothing, cigarettes, bottles of alcohol and drugs and associated paraphernalia into the graves. Often the gravediggers allow the mourners to do this, but will then subsequently select certain objects such as the bottles of alcohol for removal, citing the health and safety risk. Our interviews show that, although it is the bereaved who choose what is placed into the graves during the funerals, it is the gravediggers who ultimately curate these objects for the short, medium and longer term archaeological record. Archaeologists should therefore be wary of assumptions that the selection and/or layout of grave goods is solely determined by the deceased and/or bereaved.

Furthermore, future archaeologists should consider the possibility that gravediggers may themselves have added to the material culture found within any grave cut (Anthony Citation2016). This could include the accidental loss while working of personal items such as coins, clay pipes, buckles, buttons, lace-tags, pins, hook-tags, pottery or glassware, or perhaps the intentional discarding of broken tools or miscellaneous found objects such as bones. Interpretations like this are only possible if the gravedigger’s place and role in cemetery contexts is considered.

SITE MAINTENANCE

Burial law (LACO 1977, s. 4(1)) is ambiguous in its stipulation that Burial Authorities must maintain cemeteries ‘in good order’. How exactly this standard is defined and enacted on a daily basis—and thus its legacy within the tangible and intangible archaeological record—is therefore largely left to frontline staff. Following the burial, and due to air-pockets in the back-filled soil, soil type and weather conditions permitting a grave usually takes around six months to settle before a headstone can be erected. The grave may need topping up frequently with more soil as the ground sinks and settles (ICCM Citation2014, 15). Leftover soil from current digs in other parts of the site is often used, explaining why future archaeologists will find mixed soil types (e.g. clay in an area of otherwise sandy soil, or vice versa). This should be done for the entire settlement period, but in practice, due to time and staffing limitations, priority is given to those areas of the cemetery which are most frequently visited. Coffin collapse is another common cause of sinkage, and many interviewees lamented that contemporary coffins were poorly constructed compared to older ones. As with the use of explosives to break bedrock (above), these comments evinced an intangible, but nonetheless powerful nostalgic pride in the hard work and craftsmanship of their predecessors and a desire to uphold this professional legacy by backfilling graves correctly in order to negate the impact of poorly made present-day coffins.

While previous studies have noted that it is important for people to leave objects at the gravesides of their loved ones and tend the grass around the grave (Thomas Citation2006; Jorgensen-Earp and Lanzilotti Citation1998; Søfting, Dyregrov and Dyregrov Citation2016), the gravedigger’s curatorial role in this regard has been less considered. In yet another instance of intangible emotional labour, sympathy for the bereaved leads the gravediggers to attempt to strike a balance between demonstrating ‘respect’ on the one hand, and the need effectively to maintain the cemetery on the other. Therefore it is the gravediggers and bereaved jointly who negotiate what material culture is left by the graveside, as well as what is left in the grave-cut itself (see above). This is a significant finding for archaeologists, highlighting as it does the gravedigger’s probable curatorial role in terms of the selection and placement of above-ground funerary deposits at historic burial grounds too. It is also not without difficulty, since aesthetic sensibilities can be a point of significant contention and constant re-negotiation between the gravediggers and visitors to the cemetery (Woodthorpe, Citation2011; ICCM Citation2014, 17). In particular, many of the gravediggers attested to an increasing trend for visitors to leave objects upon and next to graves (). These can include plastic or wooden windmills, teddy bears, LED lights, toy prams, bottles of alcohol, cigarette lighters and even an imitation marijuana leaf. Many of the gravediggers we interviewed expressed this tension in terms of a decline over time in aesthetic sensibilities, noting also practical concerns about how the items got in the way of mowers and strimmers, and that they therefore occasionally would move objects:

FIG. 5 Graves surrounded by material culture placed there by the bereaved, which is then curated, by necessity, by the gravediggers.

‘People we bury now I think are more relaxed. People in the olden days, you could have a certain thing and that was that. You couldn’t put anything else on it. But now I think because it’s just one headstone, people tend then to push, I’ll have this, I’ll have that. And you’ve got to be hard if you’re going to be in this job. If you’re weak, people will run over you.’

Furthermore visitors (according to the gravediggers) often blamed the loss of treasured items on the cemetery staff. One example of this was the visitor who blamed them for removing flowers from their family member’s grave, when in fact it was simply due to deer eating the flowers as evidenced by hoof marks in the snow.

Several gravediggers also described how they exercised greater leniency with regard to tributes on the graves of children and babies ():

‘In a way that is allowed more so because obviously nobody wants to lose a kid do they. They appreciate

that would be too sensitive to move teddy bears and stuff like that.’

Responsibility for maintaining the headstone itself technically falls to the burial rights holder (ICCM Citation2014, 22, 71). However, in practice many headstones have fallen into disrepair, particularly at older cemeteries. Given the aesthetic, maintenance (ICCM Citation2014: and—especially—safety (BBC Citation2003) concerns these present, the law affords Burial Authorities considerable powers to remove such monuments (LACO 1977, s. 16). While the obligation upon Burial Authorities to publicise an intention to remove headstones is specified in some detail (LACO 1977, schedule 3) how the removals themselves should be carried out is not addressed. Our interviewees described breaking monuments up with metal bars, before throwing the pieces into the graves below on top of the coffin and backfilling. Often coffins were broken in the process, and the body therein exposed. The role of clearing monuments is archaeologically significant, demonstrating the extent of the gravedigger’s role in curating the material environment of cemeteries for future generations. Beyond this, there is also the intangible, emotional impact upon the individual gravedigger concerned. Our interviewees described clearing gravestones as an upsetting task, and struggling to reconcile its destructive nature with the normally respectful and emotionally empathetic nature of their roles ():

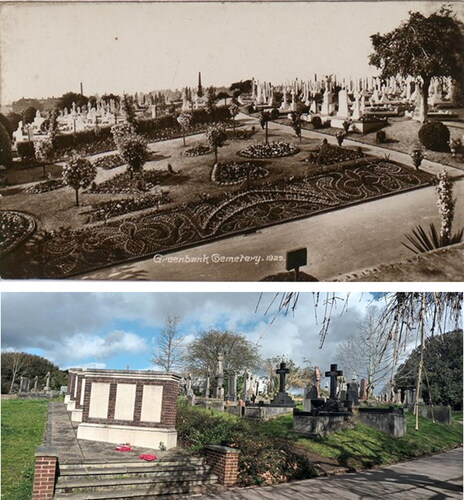

FIG. 7 Top is a postcard of Greenbank cemetery sections A(l) and B(r) 1929, depicting densely packed memorials and formal garden in foreground (image courtesy of Bristol Archives, 43207/14/3). Compare with bottom: Greenbank cemetery 2024, post clearance and with a war memorial now occupying the former garden area.

‘I look back at it now and I think I hope he is not up there and looking down on me.’

REOPENERS AND EXHUMATIONS

The process to reopen an existing grave in order to inter a further individual also leaves marks in both the tangible and intangible archaeological records. The law requires that coffins are interred no less than six inches vertically apart from one another, with two feet between the final coffin and the surface to avoid disturbance to the grave by animals (if the coffin is of ‘perishable material’, or three feet otherwise) (LACO 1977, schedule 2 (2–3). Once a request for a reopener is received, together with evidence for the ‘grave rights’Footnote11 The burial records are checked to determine the location of the grave. However, these records are often very incomplete, particularly for older sites. This means that, as noted earlier, much of the knowledge of where different graves are located is handed down orally between generations of gravediggers and is learned experientially. This is yet another example of how the gravediggers’ in-depth knowledge of the cemeteries is essential to the task. The task of reopening a grave also exhibits the gravediggers’ skills in excavation, since it relies on sophisticated digging techniques and the ability to detect subtle changes in the soil matrix.

Whether digging by hand or by machine, the grave is first excavated from the centre outwards, de-turfing and checking for changes in the soil colour/texture which indicate the position of the original grave cut. The friable grave-fill is then excavated. This reveals the previous cut of the grave, which several of the interviewees claimed was normally cut to a high standard with very straight sides. This is another example of the gravedigger’s showing admiration for the professional skill of past gravediggers. That said, there were also accounts of discovering past gravediggers’ poor workmanship, such as graves having been backfilled with large stones and/or dug insufficiently deep, meaning that there was not enough space to bury another individual within the grave. Such graves will then require a ‘capping’ with concrete in order to prevent animals from disturbing them. The family are then normally informed that the grave is not usable for further burials and offered another grave plot gratis for subsequent additional burials.

Shoring is then placed into the grave to prevent collapse, and the gravediggers continue to excavate until either a change in the soil colour is noticeable (the soil tends to turns a copper green colour about 6–8” above the previous coffin, due to the gases released during decomposition) or, and more commonly, they notice the smell of the previous internment. Thus reopeners are occasions in which gravediggers must interact viscerally with dead bodies rather than merely boxes (see above). Several of the interviewees explicitly stated that they usually tried to ignore the fact that they were interacting directly with the dead:

‘You just switch off from it. You just concentrate on your job, as simple as that.’

‘Sometimes when it back fills, it just leaves a pocket underneath so it don’t all drop down. Because it goes so hard before the coffin drops or anything, there’s a void and you can be digging down there and the amount of times I’ve gone flat straight down there and there’s a skull behind you and you go oh sugar.’

‘Opening up a grave and removing an individual is an emotive and contentious act in which to participate. The gravedigger is placed under scrutiny by a home office or police representative and thus feels that a professional job must be undertaken in the most difficult of circumstances. These exhumations are normally undertaken undercover of darkness or at least hidden from public view in a tent or similar, and the smell combined with the accompanying scrutiny can make for an uncomfortable set of circumstances. Here the gravediggers must rise to the challenge and undertake the work to professional standards utilising all the tools and techniques at their disposal. It is rare as a gravedigger to catch sight of a corpse, and many gravediggers tend not to think about the body in the coffin, but rather look upon the job simply as ‘burying a box’, however with exhumations this is one situation where the body may become visible as coffins, affected by age and damp, can crumble and fall apart exposing the deceased, and if this happens it takes a strong stomach to ignore what can be seen and smelt, and if the job is to be completed to the satisfaction of the attending officials, the body and as much of the coffin that can be removed must make its way safely into the shell-coffin. The smell may linger for days on the gravediggers’ clothes, and their clothes may need a good wash afterwards, but they are still expected to treat the situation with professional decorum utilising all of their accrued skills. The role of the gravedigger may be tough, but most gravediggers would agree that the quiet solitude of the cemetery - normally without a boss peering over one’s shoulder - and the hard physical labour undertaken each day, is still ‘a job worth doing.’

While exhumations may leave more or less physical marks in the ground, in this and all the other accounts our interviewees gave, it is the intangible aspects of performing an exhumation—the professionalism under scrutiny, the sights and smells, and ultimately the pride in a difficult job well done which are to the fore, and should therefore be borne in mind by future archaeologists.

ACCIDENTAL DISTURBANCE OF THE BURIAL RECORD BY GRAVEDIGGERS

Throughout the study it became increasingly obvious that one of the topics that the gravediggers were reluctant to discuss was the accidental disturbance of dead bodies and therefore the impacting of the burial record. This reluctance is likely due to the high standard of professionalism that the gravediggers take pride in and also fear of any negative publicity. However, Stuart Prior can provide us with several examples of how gravediggers can accidentally interact with dead bodies.

‘So basically, I was in the grave. I was digging down to do a re-opener. So, there was somebody in that grave already, but they should have been way below the level at which I was digging….and I thought somebody had thrown in one of those ceramic flowerpots because you could see this white thing at the end of the grave. So, I bent down and grabbed it, pulled it out, and it was someone’s head. Because what we were seeing was the shiny dome of the top of the head. So I suddenly was standing there in the grave with a human head in my hands. I was like oh my gosh it should have been down another 6 inches below where I was. I basically had to try and put it back in as best I could and obviously, in doing so I detached any of the bones that were attached to the base of the skull. So that’s one instance of where I directly interacted with a deceased person and subsequently impacted the burial record. So, if archaeologists excavate that in the future, there is going to be an obvious disturbance of that burial.’

This demonstrates that often these accidental interactions with human remains are the result of previous mistakes by gravediggers. In this instance the earlier gravediggers did not bury the first coffin deeply enough, resulting in this particular burial impacting significantly upon the archaeological record. Although the disturbance and intercutting of graves is prevalent and well-attested in older churchyards (Tarlow Citation2010, 94) this phenomenon has been recorded less frequently in garden cemeteries simply because few have been excavated thus far. The evidence highlighted by the study with regard to the accidental interaction between gravediggers and the deceased is thus an important interpretative tool that future archaeologists can use when interpreting disturbed burials at these sites. Stuart Prior provides us with another example.

‘I was digging another re-.opener. It was a re-opener for a husband and wife. The husband had died first. Subsequently I was digging to reopen the grave for the wife. I was down about three and a half to four feet. I stood on top of what I knew was the coffin, because you could actually feel it under your feet. Then the coffin collapsed. The cemetery was on a slope. So, the coffin had rotted and become damp and I was stood on what I thought was a solid area. Now the problem is when the coffin lid collapses under your feet, the coffin boards act like an ankle breaker trap so you can’t pull your feet out. My workmates were trying to pull me out from up above and yet they couldn’t get me out. So that burial was accidentally disturbed because the coffin lid collapsed, and I went in with it. We try our best as gravediggers not to impact the burial record, but sometimes you’ve got no choice.’

This impacted the burial record by likely moving or manipulating the body within the coffin and also by damaging material culture in the form of the coffin itself. Stuart Prior then continues to describe how he and the other gravediggers improvised material culture to be able to bury another coffin in the grave.

‘Every time I tried to pull my foot out, more and more soil was going in, so we needed to stop the coffin from filling with soil, debris and detritus. So, in the work-shed nearby there was a plastic ‘for sale’ house sign made of corrugated plastic. I managed to get my foot out and I put this sign in the grave. I covered over the hole, I backfilled in an inch or two of soil so that we were able to still have the depth to bury the next coffin. So, when future archaeologists dig up that grave, they are going to find between the two bodies a ‘for sale’ sign for a house. So, there’s actual physical evidence of the disturbance of that grave.’

This is another example of gravediggers using ingenuity to problem solve and resolve issues caused by poor past workmanship. Employing the plastic house sign to stop the spoil from filling up the lower coffin and allowing the second coffin to be buried involved the addition of new material culture to the grave. Therefore future archaeologists cannot assume that all material culture within a grave is contemporaneous with the original interment. Once again, this demonstrates gravediggers’ significant impact on the burial records of these cemeteries, and how accurate archaeological interpretations of these sites are impossible without considering the role of gravediggers.

Other mistakes on the gravedigger’s part will potentially be observable by future archaeologists. An example of this is the accidental disturbance of human remains when digging re-openers. As noted above it is not uncommon for previous coffins to have been buried at too shallow a depth, and for gravediggers to subsequently fall through the coffin lids. This would leave a distinctive impact on both the coffin and body within it, such as the movement of body parts or the crushing of the ribs and other delicate bones. There are several reasons why bodies and coffin lids could have been disturbed post-interment, ranging from natural movement with soil and water, to human interaction. However, by acknowledging that gravediggers falling through collapsing coffin lids is a recognised and recorded phenomena, this can be included in the list of possible reasons when determining causality.

Anachronistic burials, where older remains are reburied at sites which postdate them, are another aspect of gravediggers’ duties which impact in hitherto overlooked ways upon the archaeological record. Indeed, this is an example of direct interaction between the present-day cemetery staff and archaeological projects. Stuart Prior gives an example:

‘When archaeologists were digging prior to the construction of a new shopping centre in Yeovil, The Quedam, they found a 17th century lead lined coffin. They took that lead coffin and they brought it up to the cemetery. We then had to dig a massive hole for this coffin because it’s huge. So basically, you’ve got a burial from the 17th century inserted into a Victorian cemetery. So that’s going to be the earliest burial that future archaeologists will find at the cemetery and they’re going to be scratching their heads thinking well, why is this really early burial in a cemetery that wasn’t even open yet? So that’s a real direct example of the gravedigger’s relationship with archaeology. Ultimately, future archaeologists will only be able to clearly understand what happened if the burial records that we made (of that plot) survives.’

DISCUSSION

SIGNIFICANCE FOR ARCHAEOLOGISTS

This research has provided evidence of the gravedigger’s instrumental role in the formation of cemetery landscapes, which is a process undertaken in negotiation with the families of deceased individuals, and in accordance with burial legislation (and industry guidance) where the latter exists. Gravediggers clearly play a leading role in deciding where graves should be located within the cemetery, digging the actual grave cuts, mediating the interment and taking care of the graves post-interment. Since these sites may be excavated by archaeologists in future, this evidence is essential for current and future interpretations of cemetery landscapes. Indeed, if archaeologists are able fully to understand the tools and techniques employed by gravediggers, they will be able to identify and interpret the archaeological record more accurately. This applies to excavations in all periods and types of burial grounds, including churchyards, Victorian/early twentieth century garden cemeteries and contemporary lawn cemeteries.

Additionally, this study has shown how the working practices of gravediggers includes intangible emotional labour, which influences to a considerable degree the way in which they work, and thus the nature of their impact upon the future archaeological record. Examples of this include the creation of different types of funerary monuments for members of different religious and cultural groups, and permitting the greater deposition of material culture in and around children’s graves. However, many of such practices will not be manifest at all, at least not in the physical archaeological record. This means that in order for future archaeologists to have accurate, informed, and humanistic interpretations of these cemetery landscapes they must consider the gravedigger not just as a mere passive functionary but as a key agent amidst landscapes rich with human emotion and memory.

This study furthermore highlights the existence of a set of customised material culture, which has been specifically developed by gravediggers for the purpose of achieving their daily tasks in a safe, efficient and compassionate manner. This ranges from specially elongated spades and shovels, to grave frames and shoring panels, lids, soil and headstone boxes. As at Assistens Cemetery in Denmark (Anthony Citation2016) these items constitute a distinctive assemblage of material culture within cemetery sites, and it is imperative that their functions are recognised by archaeologists who wish accurately to identify material culture at these sites and the in/tangible practices which lie behind them. Furthermore, this research also highlights the curatorial role played by gravediggers in managing the objects left both within the grave cuts themselves (whether at the time of interment or later during reopening), and in and around grave plots post-interment. Although nominally it is mourners who place objects in and on graves, it is actually the gravediggers who are ultimately responsible for what is allowed to remain and its placement. This means that gravediggers play a key, hitherto unacknowledged, role in defining and curating the archaeological record within cemeteries. It can also be argued that gravediggers have a significant impact on the human remains that are excavated from cemetery sites, since their activities digging, backfilling, topping up and reopening graves can impact the human remains within, and can on occasion even be responsible for the movement of human remains within the grave cuts themselves. While the movement of existing burials within and between cemeteries has been noted (Institute of Field Archaeology Citation2004; Anthony Citation2016, 284–289; Council for British Archaeology Citation2017). However the accidental disturbance of human remains in situ requires more research (Crangle 2015, 2–3) and it is therefore of great importance that gravediggers and their activities are fully considered in this, since they play a key role in the manipulation of bodies and body parts.

This study furthermore reveals that gravediggers exercise considerable professional autonomy in deciding how to decommission and destroy funerary monuments. This means that gravediggers impact the overall cemetery landscape as well as individual graves, and in so doing help to shape the archaeological record. The considerable material impact of gravediggers’ work upon cemeteries means that archaeologists cannot accurately study post-medieval cemeteries if they do not consider the role of gravediggers at these burial sites.

Gravediggers also play a key role in organising the layout of graves in cemeteries. Their influence in this respect will be clearly observable in the future archaeological record, which will allow for a broad categorisation of the cemetery (e.g. garden or lawn). Additionally, the gravediggers interviewed described how, beyond the (limited) stipulations of burial legislation, they exercise considerable agency and knowledge about where graves are dug, and which parts of the cemetery should be avoided for various reasons. This knowledge is learned ‘on the job’ and conveyed verbally. This means that when gravediggers show customers potential burial plots they steer the latter toward safer, more efficiently dug and maintained plots. This means that if archaeologists in future see apparent disruptions or ‘missing’ graves in the layout of these cemeteries, then they will be able to determine that this is likely due to gravedigger actions. As already discussed above, gravediggers also actively facilitate the interment of individuals in the appropriate section of the cemetery, in accordance with cultural and/or religious requirements.

This study also reveals that gravediggers are highly knowledgeable about the cultural and religious funerary practices of the various groups they encounter in the course of their work. Gravediggers understand the exact burial specifications required by each group, and adapt their practices to these. This could for example be by digging the graves to certain orientations and/or depths, or by building tomb-like—but hidden—structures within the grave cuts themselves to particular specifications. The gravediggers also possess sophisticated knowledge of the practices of the different groups that they encounter on funeral days and how to facilitate and coordinate these different types of burials. This knowledge further extends to aspects of site maintenance, with many of our interviewees recounting complex information about what kinds of material culture different groups typically leave within and around graves. Gravediggers should therefore be recognised as possessing not just practical knowledge of how to manage cemeteries, but also as repositories of knowledge about the intangible funerary practices which will have shaped the future archaeological record.

CONCLUSION

Through this study, a valuable corpus of information about the role and the daily activities of gravediggers in a UK context has been gathered. This evidence is of considerable relevance to both present-day and future archaeologists, as it has shown the significant role and autonomy that gravediggers possess in materially impacting the archaeological record within burial grounds. This is achieved through the selection of grave plots, digging the graves, creation of material culture, facilitation of funerals according to cultural and/or faith requirements, backfilling of graves, reopeners, exhumations, their ongoing curation of material culture and the management (including sometimes destruction) of funerary monuments. This study also highlights the degree of emotional labour required of gravediggers, from comforting and displaying respect to bereaved families to understanding and facilitating the requirements of various cultural and religious groups, and how this directly or indirectly impacts what will later be seen on or below the ground. Since gravediggers have been at work in the British Isles for at least a millennium if not more, any future archaeological analysis of burial grounds must therefore consider the role of gravediggers and their impacts upon these landscapes.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Spoil is the term utilised for excess soil removed from a grave cut.

2 Crematorium opened 1971, with burials accepted from 1972.

3 A Re-opener is a secondary burial in an already established grave plot.

4 Taking a grave is the act of overseeing the graveside service, checking that all goes to plan with the burial, that the coffin fits into the grave-cut, dealing with the backfilling etc, as well as being mindful of any family/cultural/religious wishes, additionally ensuring adherence to Health & Safety Policy and relevant Codes of Practice.

5 Exhumation is the action of digging up something buried, especially a corpse.

6 Digging out is the act of cutting and preparing a grave for burial.

7 Backfilling is the act of filling a grave back in once burial has taken place.

8 Ribbing is the planks of wood or metal struts used to support the grave-sides, preventing collapse.

9 The banksman works atop the gravecut, shovelling upcast spoil from the graveside into a soil box, or if an excavator/JCB is employed, carefully monitoring the machine bucket for any obstructions; additionally monitoring regulated standards, such as those laid down by the UK’s Health and Safety Executive.

10 A legacy cemetery in this context means one that is no longer accepting new burials (except for the occasional re-opener) as it is deemed to be full.

11 Documentation, usually in the form of a certificate, proving the customer’s right to inter a body in the plot concerned. As noted above this does not equate to purchase of the land, which continues to be owned by the Burial Authority—although in practice the two largely have become erroneously conflated in popular belief (ICCM 2014, 13, 18).

References

- An Act to amend the Burial Acts 1857 [online] (20 & 21 Vict., chapter 81). UK Government. Accessed April 11, 2024. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Vict/20-21/81/contents.

- Alaimo Pacyga J. 2023. “A Biography of Place: Thinking Between Text, Practice, and Space at the Mission of St. Joseph, Senegal.” Historical Archaeology 57: 912–931.

- Anthony, S. 2016. Materialising Modern Cemeteries: Archaeological Narratives of Assistens Cemetery Copenhagen. Lund: Media-Tryckt.

- Barnard, S. M. 1990. To Prove I’m Not Forgot: Living and Dying in a Victorian City. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation). 2003. “Graveyard Tragedy Family Compensated.” Accessed February 27, 2024. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/north_yorkshire/3077062.stm

- Bristol Cemetery Committee Minutes. 1927–1940. Bristol Record Office: BRO M/BCC/CEM/2.

- Bristol Cemetery Committee Minutes. 1954–1963. Bristol Record Office: BRO M/BCC/CEM/4.

- Brooks, C. 1989. Mortal Remains: The History and Present State of the Victorian and Edwardian Cemetery. Exeter: Wheaton.

- Buckham, S. 2003. “Commemoration as an Expression of Personal Relationships and Group Identities: A Case Study of York Cemetery.” Mortality 8 (2): 160–175. doi:10.1080/1357627031000087406

- Butler, E. 1832. “George Tappin, the Grave Digger.” Accessed March 10, 2024. http://collections.readingmuseum.org.uk/index.asp?page=record&mwsquery=%7Btotopic%7D=%7BEarly%20portraits:%20highlights%7D&filename=REDMG&hitsStart=7

- Cemeteries Clauses Act. 1847. An Act for Consolidating in One Act Certain Provisions Usually Contained in Acts Authorising the Making of Cemeteries, 10 & 11 Vict. c. 65, 9 Jul 1847.

- Chadwick. (1842) 1965. Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain. Reprint, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Council for British Archaeology. 2017. “Guidance for Best Practice for the Treatment of Human Remains Excavated from Christian Burial Grounds in England.” Accessed March 10, 2024. https://apabe.archaeologyuk.org/pdf/APABE_ToHREfCBG_FINAL_WEB.pdf

- Crangle, J. N. and University of Sheffield. 2016. “A Study of Post-Depositional Funerary Practices in Medieval England.” Diss., University of Sheffield.

- Curl, J. S. 1975. “The Architecture and Planning of the Nineteenth-Century Cemetery.” Garden History 3 (3): 13–41. doi:10.2307/1586489

- Curl, J. S. 1980. Death and Architecture. Stroud: Sutton Publishing.

- Curl, J. S. 1983. “John Claudius Loudon and the Garden Cemetery Movement.” Garden History 11 (2): 133–156. doi:10.2307/1586841

- Curl, J. S. 2000. The Victorian Celebration of Death. Stroud: Sutton Publishing.

- Dalziel, E. 19th. Cent (Date Unknown). Grave Digger. https://harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/244577

- Daniell, C. 1998. Death and Burial in Medieval England 1066–1550. Hoboken: Routledge.