ABSTRACT

This paper presents an empirically grounded conceptual framework for the various dimensions of scholar-activism based on 15 in-depth interviews with prominent communication scholar-activists. It theorizes about the meanings, practices, challenges, and opportunities encompassed by this type of scholarship from the perspective of those in the field. Our participants see scholar-activism as a fluid concept that comprises a range of goals, methods, and activities. They view scholar-activism as distinct from overlapping terms such as engaged scholarship, public scholarship, critical communication, participatory action research, and community organizing. Despite differences in labels, there is a relatively unified sense of the practices, challenges, and opportunities related to scholar-activism. The main dimensions of communication scholar-activism that emerge from the data are that it is: community-driven, social justice-oriented, action-oriented, grounded in co-creation of knowledge, interdisciplinary, long term in nature, challenging of the status quo, driven by intrinsic motivators, and boundary-blurring.

With rising threats on academic freedom, the re-emergence of authoritarianism, and widening socio-economic inequalities during this global pandemic, supporting the work of scholar-activists is not just significant but vital. Given the centrality of communication to activism, community initiatives, and social movements, it is not surprising to note the increased relevance of and growing interest in scholar-activism in the communication discipline. Many would argue that activism has a natural home within universities as critical public-service institutions, but academia’s relationship with communities is complicated. Balancing the tension of being both a scholar and an activist within academia is challenging. Despite the many contemporary global social issues and the assumed natural role of higher education in addressing them, several institutions tend ‘to abandon this civic mission’ (Frey & Carragee, Citation2007, p. 2). Indeed, academia is often rightly perceived as an ‘ivory tower,’ self-serving and starkly separated from its surrounding communities.

While communication scholars are, without a doubt, interested in making a difference through their scholarship, a key question is whose interests are being served and which communities benefit from their scholarship. The overarching commonality between those who consider themselves scholar-activists is the desire to make a difference, although what exactly this looks like is highly debated (Dempsey et al., Citation2011; Frey, Citation2009). This persistent debate creates fractures among different bodies of scholarship who share this common goal, warranting the clarity we seek through this project. It is essential for early-career scholars and those who wish to engage in communication scholar-activism to understand what it entails, what challenges and opportunities such scholarship bring with it, and what strategies and benefits motivate communication scholar-activists.

This study makes several significant contributions to communication scholar-activism. First, we offer a new conceptual framework delineating nine dimensions that clarify definitions, meanings, practices, challenges, and benefits of communication scholar-activism. Second, it contributes to ongoing debates in communication about using the term ‘activist’ by clarifying how it is similar to and different from other related concepts such as engaged scholar and critical scholar. Third, unlike most prior theorizing in this area, our framework is grounded in empirical data from in-depth qualitative interviews based on real-world experiences and insights from 15 prominent communication scholar-activists. Finally, our study’s findings highlight that despite slight differences in labels, there are significant similarities in the practices that scholar-activists engage in, allowing communication scholar-activists to craft a shared identity that enhances their collective political power and helps legitimize this work. Doing so also has institutional benefits in facilitating conversations within professional organizations and other academic spaces about policy changes needed to support better hiring, evaluation, tenure, and promotion practices relating to communication scholar-activists.

Communication scholar-activism: meanings and practices

Scholar-activism is fraught with many debates, including the term ‘activism’ itself and what types of scholarship should fall under this banner. Debates about what constitutes true scholar-activism (Dempsey et al., Citation2011) are ongoing and productive conversations continue to be had about what can be considered ‘impact,’ ‘intervention,’ and ‘community’ (Freedman, Citation2017), as well as who scholar-activists serve and to what end. For example, as Dutta notes, ‘How we define the community as academics working on issues of social justice might, in reality, differ dramatically from the multiple often competing definitions of the community that community members might articulate’ (Dempsey et al., Citation2011, p. 262). Similarly, different bodies of literature have treated these concepts in several different ways.

Communication scholar-activism is rooted in a long history of critical scholarship within communication (see Fuchs, Citation2016; Jansen, Citation2002). It has traditionally sought to facilitate what Kellner and Kim (Citation2010) describe as ‘individual development and social transformation for a more egalitarian and just society’ (p. 3). Critical communication scholarship, which includes feminism, postcolonialism, political economy, and queer studies, directly addresses power structures that seek to oppress marginalized individuals. These literature bodies attempt to reveal power inequities within our society and foster emancipatory potential to bring about change through meaningful scholarship. These critical frameworks are often used to guide communication scholar-activist research in addressing power inequities and creating change in marginalized communities (e.g. Ahmed, Citation2017; Asante & Asante, Citation1988; Castañeda & Krupczynski, Citation2017; Cloud, Citation2007; De Jong et al., Citation2005; Dutta, Citation2011; Citation2020; Johnson, Citation2017; Pavarala & Malik, Citation2007).

Because the point of communication scholar-activism is to address power inequities and make a difference, there is also an agreement that some type of community-based intervention is necessary. To capture this, Frey and Carragee (Citation2007) offer ‘communication activism for social justice scholarship’ as a term to describe the work done by those scholar-activists who engage in first-person social justice scholarship, with a clear desire for social justice. This first-person research is defined as making a difference through research, meaning the researcher intervenes and engages with a historically marginalized community to facilitate change. Likewise, Rodino-Colocino (Citation2011) uses the term participatory-advocacy to describe activist-scholarship that is critical and takes a first-person perspective by participating in community change. This definition is different from third-person social justice scholarship, where difference is made from research through observations about social justice, without intervening or engaging with the community. This distinction is critical to our conceptualization of the term communication scholar-activism, which is more closely aligned with third-person rather than first-person social justice scholarship.

Apart from critical approaches, communication scholar-activism is also rooted in applied communication scholarship that goes beyond theorizing knowledge to seeking real-world solutions to social issues. Although qualitative and interpretive methods are frequently used for communication activist-scholarship, this is not to say that empirical quantitative methods are not also essential for bringing about social change. Intervention or program evaluation research has often used multiple empirical methods to address several critical social issues, especially within health communication and media education contexts (Dutta, Citation2011; Citation2020; Ramasubramanian & Banjo, Citation2020).

There is also overlap between communication scholar-activism and participatory action research (PAR), although the latter comes out of the education discipline. PAR stems from Freire’s (Citation1969) work on critical pedagogy, which promoted democratic means in educating about social justice. It sought to ‘fully engage students in a transformative, liberating, and humanizing process of learning by working ‘with’ (and ‘in solidarity with’) students’ (Rodino-Colocino, Citation2011, p. 1702). In the same vein, like scholar-activists, PAR academics seek to collaborate with community members to solve real-world problems relating to social inequalities (Kindon et al., Citation2007; Lopez, Citation2015). PAR is not very common in the communication discipline, although media scholars have utilized it somewhat. What differentiates PAR from scholar-activism is how it is driven by a specific political ideology such as democracy. Scholar-activism focuses on issues of power more broadly, while PAR has a clear political or ideological orientation.

Another related term is public scholarship, which considers research to be a public good and can engage with a broad range of different communities. Here the ‘public’ typically involves non-academic ‘lay’ audiences. While the notion of public scholarship is often tied to public intellectualism, the public scholarship also includes collaborations and connections with and through several types of publics, such as nonprofits, government agencies, and community organizations (Mitchell, Citation2008). The goal is to make scholarly research available and accessible to a broader public beyond academia and to listen to citizens’ voices in shaping academic research. Public scholarship is often associated with scholarship done in and through public media, including blogs, personal websites, Twitter, and other open mediated forums. However, Waisbord (Citation2019) conceptualizes public scholarship as a broader term that encompasses scholar-activists and public intellectuals who use public platforms to engage with a wider audience.

Another term that is very similar to public scholarship is engaged scholarship, which encompasses a wide range of research that seeks to impact communities outside academia (Barinaga & Parker, Citation2013; Connaughton et al., Citation2017). In particular, organizational communication scholars have embraced this moniker for their research. As Barge and Shockley-Zalabak (Citation2008) explain, this research orientation seeks to put theory and practice in conversation through a knowledge production process between practitioners and academics. However, as Carragee and Frey (Citation2016) note, engaged scholarship ‘has become such an elastic term that it can refer to virtually any interaction that occurs between communication scholars and those outside the academy and doesn’t necessarily have to have a focus on social justice or address the needs of marginalized groups’ (p. 3975). Unlike scholar-activism and PAR, engaged scholarship does not require direct engagement with participants throughout the research process and is not necessarily social justice-oriented. Based on the literature on these existing terms and definitions related to communication scholar-activism outlined above, the first two research questions posed in our study are:

RQ1: How do communication scholar-activists define scholar-activism?

RQ2: What are the practices that encompass communication scholar-activism?

Communication scholar-activism: challenges and opportunities

Although being a scholar-activist can be fulfilling, it can also be challenging (Chatterton, Citation2008; Young et al., Citation2010). Rigorous scholar-activism that is community-based and participatory takes sustained time and effort (Hotze, Citation2011; Stringer, Citation2013). Co-creating shared creative solutions for positive social change through collaboration often means being aware of privilege and positionality. It involves constant negotiations to accommodate various stakeholders such as community leaders, nonprofit organizations, and academia (Barge & Shockley-Zalabak, Citation2008). Also, scholar-activists have to balance the expectations, values, objectives, and priorities of universities with those of communities.

Skinner et al. (Citation2015) discuss three dimensions along which activist and academic fields differ: temporal, political, and economical. Activist organizing has a different temporal logic that is often much more spontaneous and unpredictable than academic rhythms constrained by teaching schedules. The professional codes, values, and ethics within one’s academic disciplines might be valued differently between academic and activist roles. And finally, the economic dimension refers to material resources such as space, labor, and funding that may or may not be shared by the two domains of activism and scholarship. These differences can both enable and constrain the practices of scholar-activists. Scholar-activists have to navigate these tensions across temporal, political, and economic dimensions in their activities, identities, and engagement.

Despite these challenges, communication scholar-activism provides opportunities to create meaningful knowledge that can benefit the individual scholar-activist, the communication discipline, academia in general, and the communities they engage with. Scholar-activists are in a unique position to highlight the vital work of activist practices and their valuable forms of knowledge production (Frey & Carragee, Citation2007). Part of this is the ability to publish in various outlets for different publics, including other academics, practitioners, and community groups (Dempsey et al., Citation2011). Academics may also have access to additional material resources, including various forms of funding and grants, which may not be available to community groups. At the very least, scholars offer a different perspective to community and activist groups, which helps foster a more collaborative and nuanced approach to addressing oppressive structures. Similarly, community-based activist work can also enhance teaching through service learning projects and active collaborative learning. The various challenges and opportunities that exist in addressing this overarching goal lead us to our third research question:

RQ3: What are the challenges and opportunities experienced by communication scholar-activists?

Method

In total, 15 noteworthy communication scholar-activists were interviewed. Our participants offered incredible depth and detail into this topic. The participants in this study are experts who are specifically known for their community-engaged communication initiatives, their innovative approaches to teaching and research, and social justice work at the local, national, and international levels. Their social justice-driven research involves many types of initiatives, including community art projects, environmental justice, health activism, media literacy, racial justice, youth leadership programming, and labor movements.

Our participants varied in race, ethnicity, gender, rank, and field of study (see ). The labels reported in the table are based on participants’ self-identification identity markers. The initial round of interviews was based on a convenience sample drawn from a conference panel on media activism. The sample was expanded through the snowball technique to be more representative of all communication scholar-activists. One of the scholars interviewed ultimately did not identify as an activist or as someone doing social justice scholarship, so we decided to exclude that interview from our final analysis. While we originally wanted to explicitly name all the experts in our study who are prominent communication scholar-activists, we decided to maintain anonymity to offer them an opportunity to speak freely on a topic that is at times controversial. Likewise, we allowed our participants to choose their pseudonyms. It’s also important to note that the researchers also identify as scholar-activists. Although we have a vested interest in the topic and were able to relate to participants’ experiences, we allowed our interviewees to share their experiences freely and ensured that we covered the many facets of scholar-activism, not simply those personally relatable to us.

Table 1. Participant information.

Interview procedures

After receiving IRB approval, in-depth interviews were conducted with our participants and lasted between 45 min and 2 h. The conversations were facilitated using a semi-structured interview guide. This method allowed participants the opportunity to guide the interviews beyond the constructed questions. Interview questions sought to parse out the relationship between scholarship and activism in theory and practice. Questions included: Do you consider yourself an activist? Why or why not? What draws you to service, outreach, and activism? How do you negotiate your role as both a researcher/teacher and activist? How do you balance your responsibilities with research, teaching, service, and outreach? What is particularly beneficial or challenging about being in academia as a scholar-activist? What do you find most rewarding about this kind of work? What is least rewarding? What do you find most challenging? What is the least challenging? Interviews were conducted via Skype, over the phone, or in person. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

We used an iterative process to analyze transcriptions. Existing literature on scholar-activism guided theme identification, but additional themes also emerged organically (Tracy, Citation2013). The two researchers initially coded the transcripts independently to identify first-level codes. Then, researchers compared first-level codes and a ‘consensus process’ (Harry et al., Citation2005; Redden & Way, Citation2017) was utilized to identify meaningful common codes. Agreed-upon codes were turned into a shared codebook. Codes included: definitions/components of scholar-activism, opportunities for scholar activists, challenges for scholar-activists, and practices/responsibilities. Transcriptions were once again coded, identifying important themes that answered our research questions. Audio recordings, verbatim transcripts, and participant checks were used to maintain rigor and resonance.

Findings

What emerged from our interviews were ‘real-life’ stories that helped us refine what existing scholarship says and what it means to do this work in practice. Our participants’ experiences shed light on what ‘scholar-activism’ means to them, the specific practices they engage in, the challenges they face in their work, and what motivates them as scholar-activists.

Communication scholar-activism: meanings

We begin by exploring whether or not participants self-identify as scholar-activists and whether they felt the term activist was the right way to describe their scholarship. Our participants theorized scholar-activism as a fluid and flexible concept. They conceptualized it as a continuum, representing a spectrum of where the identity of scholar-activists can fall. While some identified with the term ‘activist,’ others used slightly different words such as engaged scholar and organizer to characterize their work. Our participants make clear distinctions between scholar-activism and traditional activism ‘on the ground.’ While our participants recognized activism could encompass a range of scholarship, they also noted that not everything should fall under this banner. When asked, ‘Do you consider yourself an activist?’ many different answers followed. For example, as Grace explained:

As an activist, I don’t envision myself as someone who goes into a community or into an organization and tells them what I think they need to know or uses my academic credentials or prowess to challenge their lives and their structures. As an activist and in dialogic form, I envision myself working with people to create a space where they can name their world in order to change it and reflexively I know that I have power in that process.

There's some people who are activists and then go into the University, but really they're activists in academic guise. And then there are people who are academics who want to use some of their work to support activism. So it's kind of like this continuum, so I do stuff with a lot of activists. I mean, I’m not out there organizing … I guess in some ways I am [an activist].

I’m not a traditional activist. I’m not out on the protest line on the weekends … If we think of it on a spectrum, I guess I do fall in there, but I’m certainly not a traditional activist, where I’m directly involved with a lot of activist groups and organizations.

Activism tends to be a bunch of people or a few people, usually not a majority of people, organizing themselves on an issue and trying to make change on an issue. An organizer, as a counterpoint, is somebody who wants to build as much collective power amongst communities and organize those communities to build power … And so, the emphasis is more on building a bunch of people into a project, into a base that’s going to make change versus a smaller group of people who are intervening on a particular issue. And I find, in the historical record, that when people in mass are organized is when real change happens.

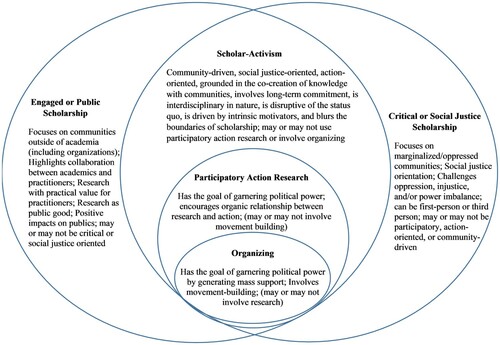

I would say in the spaces that I've been talking about engaged scholarship, it’s a little bit less explicitly politicized because … you could be engaged a lot of ways … There's no particular political, ideological orientation other than that you're involved with the community, and maybe, you want to think about what they're getting out of it at some level. Whereas participatory action research, from what I've seen, there's a little bit more of a political ideology there that aligns with certain kinds of ideas about, you know, progressive or even radical ideology and trying to involve the scholarship there. So to me, then, we can think of them as a Venn diagram, circle type thing and they also overlap in a way, but participatory action research, that was the framework that I kind of saw myself.

Communication scholar-activism: practices

These scholars are immersed in many different types of research. They work with various communities, including elementary students, young adults, activist groups, and nonprofits. Their theoretical groundings also span the communication discipline, touching on dialogue, narrative/storytelling, framing, conflict, social movements, and decolonization. While many of the scholars we interviewed do research at the intersection of media and communication, most do interdisciplinary work that is hard to confine to one label. Despite how scholar-activists in our study labeled themselves, it became clear that there were many parallels in their goals, the types of communities they engage with, how they engage with communities, and the larger power structures they seek to address with their work.

Community-driven

When it comes to defining effective scholar-activism practices, our participants’ explanations overwhelmingly centered on one thing ‒ community. Communities are fully engaged in the research process and help co-create knowledge. They are positively impacted by and are given due credit for their research involvement. Although there are many different communities that scholars can engage with, without a meaningful connection to the community they choose to study, scholars run the risk of treating their participants ‘as objects, not subjects,’ to use the words of one of our participants, Noelani. These driving forces lead to a particular set of practices that our participants feel is integral to the type of work they deem scholar-activism.

To effectively facilitate change, it is essential to work with communities to design research studies and interventions. As Kawai described, this means doing work that is beyond ‘prescribing things.’ In regards to their work, they added:

So, my work would not be what it is without community. And I'm talking about the community beyond academic institutions. Beyond the ivory tower. So, I need the community to do my work and the community needs me. We need each other and it's a mutually beneficial and interdependent, and inextricable relationship.

Social justice-oriented

The participants emphasized that it is their passion to help communities marginalized by larger power structures and bring about change, what Noelani described as ‘bring in the decolonization context.’ However, this can be difficult because, as Kawai explained:

If you ask an activist what's wrong with the world, they'll talk for days. You ask them what world do you want to live in? Crickets. Because we're taught to deconstruct systems of power. We're not taught to rebuild in its wake.

[We are] wanting to develop scholarship for social change and wanting to develop scholarship that can somehow make an intervention. And improving the lives of people and the ways in which we're engaging with each other … . … disrupting systems of oppression, challenging the status quo, and questioning why things are done in particular ways and how those ways, again, limited the access and opportunities for certain kinds of populations.

Action-oriented

Our participants wanted to serve historically marginalized communities but were keen that their work should positively impact the ground on these groups. As Sofia said:

It's not just simply scholarship for scholarship's sake, but scholarship that can really take a more active approach in shifting the kind of conversations and various practices that are happening in both local communities and universities, and outside of those as well.

Grounded in co-creation of knowledge

In the same vein, scholar-activists should study these communities and include them throughout the entire research process as much as possible. As our participant, Lacey, said: ‘You should think about how the knowledge that you were co-creating makes its way back to the communities that you’re serving, that you’re not just publishing in an academic journal.’ Although ‘scholar-activism’ requires a relationship with communities, it does not mean that the community does not desire what we know to be ‘traditional scholarship.’ For example, as Kate explained of her research, ‘Actually some of the work that I’ve done that was most appreciated by some of the groups was very traditional scholarship. They just didn’t have anyone to do traditional scholarship for them … And what they wanted was, ‘Can you tell us, we think we’re not represented in TV news. Are we represented? Yes or no? And how are we represented.’ But the key here is that the communities decided for themselves what they needed; the scholars did not prescribe what they thought was best.

A related goal of scholar-activism is promoting different types of knowledge production that go beyond the traditional articles in mainstream journals or, as Sofia described, ‘challenging heteronormative traditional Western models of how we do research.’ Part of this is recognizing the knowledge produced by non-academics as essential to scholarship and scholarship in-and-of-itself. Anna described seeing the communities she works with as ‘legitimate social actors.’ Part of her role as an activist is to ‘value [their] knowledge, not as a material that you're going to analyze but value the knowledge, [just] the knowledge that they produce.’ And as Noelani added, her research aimed to ‘center this different kind of way of knowing demonstrates, I think, activism in a way that is resistant to all of those aforementioned hegemonic kind of ways of oppressing peoples.’ This includes validating the knowledge of marginalized groups as scholars.

Interdisciplinary

Participants said that the qualities of communication as a discipline make it an ideal lens for understanding scholar-activism. Communication is inherently interdisciplinary (or transdisciplinary) in nature. Since it is influenced by and influences so many different disciplines, scholar-activism can thrive. Communication lies at the center of all community initiatives and social movements. As Kate put it, ‘Anytime you try to create a social change … you have to communicate.’ For example, Kawai, whose work is heavily influenced by art and creative writing, explained the freedom they feel to do work that captures all of their interests as a communication scholar. As they noted, ‘I'm a comm scholar … It's really been liberating. I get to do whatever I want because now I see how everything I do is connected … I would have a lot more trouble if I were in biology or something.’

As Adam added, communication scholars can serve as interpreters across multiple fields and backgrounds, given the discipline’s interdisciplinarity. He explained:

Where I work is full of people who have those kinds of neither fish nor fowl backgrounds and are therefore able to act as translators. I'm one of the rare ones … that actually has a degree in communication … [But] they're bringing those perspectives to bear on issues that are central to communication studies … in ways that I think more hermeneutically trained scholars would not do in the same way.

What is also unique about communication is that it promotes a skill essential for absolutely everything human beings do, including activism. As Kate explained:

Anytime you try to create a social change, you end up, you have to communicate. I mean, whether you’re trying to find out what issues are in people’s minds or you’re trying to document a social problem, or you’re trying to get people to discuss and see if they can come up with a shared definition of a problem or you plan an outreach campaign to talk to others about it or to advocate for a point of view or a strategic plan. It’s all communication once you decide that you want to take on a particular inequality. I mean even fundraising to build the work.

Challenges and opportunities faced by communication scholar-activists

The conversations we had with our participants revealed the multitude of opportunities and challenges that accompany scholar-activist work. In this section, we discuss its long-term nature, how it disrupts the status quo, is often motivated by intrinsic rewards in the absence of external rewards, and blurs research, teaching, and service requirements.

Requires long-term involvement

Scholar-activist projects involve a commitment to long-term engagement with the communities they work with. As Lacey noted of working with faculty who are interested in activist-scholarship:

I mean, what we’re really trying to start educating faculty on is that we don’t want to have short-term projects, to begin with. That doesn’t build sustainability, that doesn’t build a strong community in the long-run, so you might have an idea for a project, but think about how that could change over time, how it could meet community needs in different ways, that you’re not just building short-term, 6-month relationships, but you’re thinking about these in the long-term, over years.

As Keith explained of the basic requirements of such work, ‘Least rewarding is you’re running in every direction, trying to write and research, trying to build political projects, trying to have a personal life. It’s a lot. So, I don’t know if that’s least rewarding, but sometimes you feel like you’re being pulled in multiple directions.’

Challenges the status quo

Activism disrupts the status quo, including challenging the notions of what is considered ‘traditional’ scholarship. Scholar-activism is often devalued and pushed to the margins as not ‘serious’ and ‘legitimate’ scholarship. While self-doubt and a sense of being underappreciated are not unique to scholar-activists, it is undoubtedly a challenge that communication scholar-activists have to navigate since they often do cutting-edge scholarship, which by definition, challenges the mainstream. Many of the professors we interviewed highlighted the pushback they receive from other scholars about this type of work and the required amount of rigor. As Lacey described:

What I do hear a lot is, ‘That’s not academic research. That’s great community service. That’s great that you’re trying to make our community a better place, but you know, where is the academic rigor in that?’ I do hear that. But I hear that even in my field … I think academia is in a transitional period too, where we’re trying to figure out how much of this community activism is still academic research. I would argue, it can totally be academic research if we say it is.

I mean, it's, it's imposter syndrome all the way. Right? Like, I'm not that good of an activist, because I haven't gotten arrested. Or I'm not that great of a researcher because I haven't gotten this many awards. Like, we constantly devalue our production because it doesn't look like we think it's supposed to look.

Scholar-activism has consequences, sometimes dangerous ones. With the re-emergence of fascism, populism, and right-wing authoritarianism worldwide, scholar-activists experience a greater sense of threat and risk in their work. Sam describes it as ‘the assault on universities, the distrust of academic work, the sort of wide opposition to anything that sounds like critical thinking in, you know, many pockets of American society.’ For example, as Adam described of his own experience:

[Given my personal identity,] [t]here are all kinds of really good reasons to be concerned about my safety, about my reputation, about my privacy … If you look at what's happening in authoritarian regimes around the world, you know, and the crackdown on academics, especially leftist academics. In Brazil, they just go into the universities and arrest them.

Despite these challenges, these scholars also shared the many opportunities and benefits of engaging in such work. Although scholar-activists’ challenges differed slightly in terms of topic and theoretical lens, they shared commonalities in their reasons for engaging in social justice-driven work.

Driven by intrinsic motivation

As these scholars overwhelmingly pointed out, there are very few professional rewards for doing this type of scholarship. If there is no intrinsic motivation and personal drive for engaging, it simply is not worth it. As Beth explained:

The rewards in doing that type of work are totally intrinsic. You're not getting rewarded from the university for it. You know some people do things, and I'm not being critical or judgmental at all, some people will do things because it earns them more money. This does not do that. Some people might do things because it puts them in a higher position. This work does not do that. So it's really, the motivations have to be internal to do this.

I don't think that everyone should be doing this work. I think the people who should be doing this work are the ones whose hearts are in it. And the ones who have the capacity to do it, and the ones who are dedicated to doing it well … I raise an eyebrow to anyone who studies populations that they're not connected to, in ways that don't speak, or I guess in ways that don't generate the capacity for those communities to do their own work.

Blurs the boundaries of scholarship

An often-cited strategy for accomplishing the many tasks associated with being a scholar-activist is what one of our participants aptly named ‘blurring the boundaries of scholarship.’ Participants highlighted that their roles as researchers, teachers, and activists were not distinct but complementary and, if embraced strategically, helped them thrive and derive meaning from being a ‘scholar-activist.’ As Grace described, ‘I think in my finest moments, the boundaries are blurred … So, in my finest moments, I think that it’s living the life of the mind and the heart and the body, as a teacher, scholar, citizen.’ Keith shared a similar sentiment and highlighted the ways in which these multiple roles can actually help produce more meaningful work. He added:

My research is better, it’s deeper, I think it’s more profound and stronger because of the relationships I have beyond the academy, the work I’m committed to beyond the academy, the multiple voices and communities that form beyond the academy. It makes my research stronger and then it makes my teaching stronger, again, because I’m engaging in a much broader world that I’m able to bring to the classroom. And my work in the classroom, my work in the academy and my research make my practice and social movement work stronger. So, in each case, I think what’s most rewarding is there’s a greater depth in the work I’m able to do.

Because I'm not compartmentalizing, because I get to be my whole self in my work now, it's actually much easier. It was harder to balance feeling like I had to do these research projects because they were looked at as legitimate research. I barely had any time to do my art, which means I was stifling my own creative expression … [Now], when I go to my studio to paint, I don't feel like I'm wasting time anymore. I am doing research. And so, a lot of it was a matter of me just engaging in some cognitive restructuring. Like, let's reimagine what we're doing as a productive and effective tool that is connected to teaching and research, in-service versus, you know, a waste of time.

A conceptual framework for communication scholar-activism

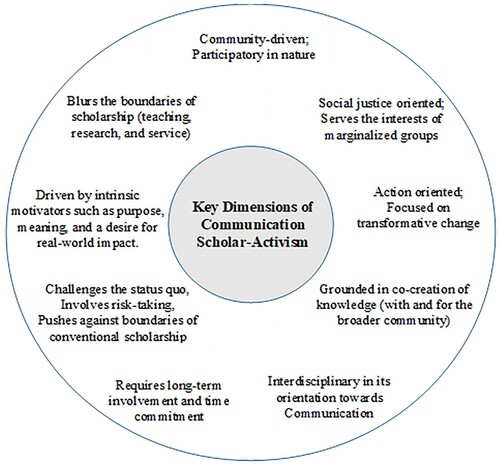

Building on our interview data with communication scholar-activists, we propose a conceptual framework for theorizing about communication scholar-activism. The key dimensions are summarized below:

Community-driven: Scholar-activists engage directly with a community, not simply for a community. Their work is not just community-based but is community-driven.

Social justice-oriented: Scholar-activists’ goals are to reduce social inequalities, challenge hierarchies, and question injustices among marginalized communities.

Action-oriented: Scholar-activists are deeply committed to taking concrete, actionable steps to bring about real-world transformations in the communities they serve.

Grounded in the co-creation of knowledge: Scholar-activists see their work as having both academic and social impact. They create knowledge with and for broader audiences beyond traditional academics. A key element of such knowledge production is the community participants’ active involvement in co-creating knowledge in inclusive ways.

Interdisciplinary. Scholar-activists see communication as central to activism and the interdisciplinary nature of communication as offering flexibility in the types of intellectual histories and theoretical frameworks one can utilize to further scholar-activism.

Requires long-term involvement. Scholar-activists build long-term relationships of trust, transparency, and support with communities, which involve time commitment and continuity.

Challenges the status quo. Scholar-activists’ work challenges the status quo and questions traditional ideas about what is considered scholarship. Doing so could, at times, be risky and dangerous, leading to negative psychological and professional impacts on scholar-activists.

Driven by intrinsic motivation. Scholar-activists are primarily driven by intrinsic motivators such as meaning, purpose, a desire for ‘real-world’ impact, personal connections with social issues, and authentic relationships with community members and organizations that help nourish their whole selves – professionally and personally.

Blurs the boundaries of scholarship. Scholar-activists bring their whole selves into their work: scholars, teachers, activists, artists, and citizens. They challenge the rigid boundaries of scholarship by blurring, blending, and merging various aspects of their work in meaningful, synergistic, and strategic ways.

To provide additional clarity to the contested meanings and definitions relating to communication scholar-activism, we use these dimensions along with the empirical data from our findings to situate scholar-activism within the larger disciplinary conversations on engaged/public scholarship and critical/social justice scholarship.

clarifies that communication scholar-activism combines both engaged/public scholarship and critical/social justice scholarship. Engaged/public scholarship is similar to communication scholar-activism in that both are characterized by collaborations between academia and communities outside of academia (Barinaga & Parker, Citation2013; Connaughton et al., Citation2017). Engaged scholarship can involve full participation of communities in the research process, but again, this is not required in all scholarships under this banner. While engaged/public scholarship can be driven by critical theory, it is not necessary. However, scholar-activism must necessarily be social justice-oriented. In other words, scholar-activism is critical social-justice-oriented engaged/public scholarship. We note, though, that different scholar-activists might have slightly different conceptualizations of what social justice looks like and how to best advocate for that social justice for various causes and communities.

Scholar-activism shared many characteristics with critical/social justice scholarship, such as focusing on marginalized communities, a social justice-orientation, and the goal of challenging injustices. While more traditional forms of critical scholarship use a ‘third-person-perspective,’ communication scholar-activism is action-oriented, community-driven, and involves the co-creation of knowledge with the involved communities. In other words, communication scholar-activism is community-driven and action-oriented critical social justice scholarship.

Organizing is another term that our participants mentioned. Like scholar-activism, organizing also emphasizes a ‘first-person-perspective’ and full collaboration with the communities of interest. However, organizing also involves movement-building and has the goal of garnering political power and mass support. The participants who mentioned organizing were also those influenced by PAR. Organizing and PAR both focus on political power and actionable change. However, organizing does not always involve research or scholarship, integral to both PAR and scholar-activism. Like scholar-activism, PAR has a social justice-orientation, requires engagement with participants throughout the research process, and involves an organic relationship between action and research. Scholar-activism need not always use PAR as its approach. While PAR is driven by a particular political or ideological orientation, scholar-activism addresses power more broadly.

Discussion

This paper builds on existing research on communication scholar-activism (e.g. Cloud, Citation2007; Dempsey et al., Citation2011; Frey & Carragee, Citation2007) by proposing a new data-driven conceptual framework to theorize better and understand what communication scholar-activism is through the use of experiential data. As illustrated here, their on-the-ground perspectives add more depth and clarification than can be found by reviewing past work in the abstract.

The framework we present does naturally overlap with some characteristics of engaged scholarship, critical communication studies, public scholarship, and social justice scholarship. Yet, our conceptualization expands on these related bodies of work to provide more nuance and clarity in the practices that scholar-activists engage in. For example, we distinguish between community-based and community-driven scholarship, noting that communication scholar-activism is the latter. Likewise, we offer co-creation of knowledge, long-term involvement, intrinsic motivation, and blurring of boundaries of scholarship as essential aspects of scholar-activism, which prior scholarship has not yet explored in-depth. We also add to the existing literature by offering additional characteristics unique to scholar-activism based on scholar-activists’ motivations and challenges.

The current ‘silo-ed’ way of thinking about these interrelated bodies of work and the existing ambiguity of terms can work against scholar-activist work. Higher education institutions often have a more challenging time understanding what scholar-activists do, which impacts the types of organizational support and resources made available to scholar-activists (Quaye et al., Citation2017). Providing a coherent and comprehensive conceptual framework clarifies where communication scholar-activism is situated within the discipline and can make space for greater cross-area collaboration and engagement.

Likewise, the labels that communication scholar-activists use to define themselves are not value-neutral. The strategic essentialism of the term ‘scholar-activism’ can have political power for scholar-activists and provide a sense of shared unified identity or solidarity (Routledge & Derickson, Citation2015). However, we also recognize that just like with the term ‘political organizing,’ it is possible that ‘scholar-activism’ is seen as too political in some contexts, including higher education. As a result, scholar-activists can choose to be strategic about what labels they use and whether or not their practices are identified as scholar-activism according to our framework. This is why it is also critical to make a difference between labels and practices.

Beyond the theoretical and conceptual contributions, our study also has practical implications for aspiring communication scholars and those new to scholar-activism within our discipline. The nine key dimensions that we delineate for communication scholar-activism (see ) offer valuable insights about the scope of the work, the range of activities, types of projects, expectations, motivations, and challenges that characterize such work. For our participants, communication scholar-activism brought personal satisfaction and a sense of purpose even though they had to contend with challenges such as long-term commitment, self-doubt, devaluing of their scholarship, and pushback from those in power. Despite the many challenges and constraints, it was still clear that each of these scholar-activists felt that continuing the work is imperative, and this is an essential part of what drives their passion for their job as academics. However, communication scholar-activism is not and need not be everyone’s cup of tea. One needs to assess their strengths, training, ethical values, resources, costs, institutional support, risks, and motivations in doing this work.

To be sure, there are many other issues and topics within communication scholar-activism that need further exploration and inquiry. We discussed organizational fit and the constraints of tenure with our interviewees; however, given space constraints, this paper has not been able to explore systemic challenges relating to hiring, tenure, promotion, and advancement. Several structural conditions need to be addressed to provide better institutional support for communication scholar-activists. Future research should consider the scholar-activist’s academic positionality, the structures of power within higher education that co-opt activist movements, and the limits on possibilities for social transformation within existing systems. Similarly, although it is not the direct focus here, it is essential to note that the scholar-activist’s identity and positionality within communities are also critical contextual elements that shape motivations, experiences, challenges, and benefits for engaging in scholar-activism. Future publications need to explore the complexities of place, identity, and socio-political contexts in influencing scholar-activism. For instance, although we included communication scholars from various backgrounds in this study, they were predominantly from within the U.S.A., which limits the theorizing based on experiences within this socio-political context. The current research makes significant conceptual and practical contributions, especially for emerging communication scholar-activists considering getting involved in this growing subfield within the discipline.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ahmed, S. (2017). Living a feminist life. Duke University Press.

- Asante, M. K., & Asante, M. K. (1988). Afrocentricity. Africa World Press.

- Barge, J. K., & Shockley-Zalabak, P. (2008). Engaged scholarship and the creation of organizational knowledge. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 36(3), 251–265. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00909880802172277

- Barinaga, R., & Parker, P. S. (2013). Community-engaged scholarship: Opening spaces for transformative politics (introduction to the special issue). TAMARA Journal for Critical Organization Inquiry, 11(4), 5–11. https://tamarajournal.com/index.php/tamara/article/view/349

- Carragee, K. M., & Frey, L. R. (2016). Communication activism research: Engaged communication scholarship for social justice. International Journal of Communication, 10, 3975–3999.

- Castañeda, M., & Krupczynski, J. (2017). Civic engagement in diverse Latinx communities. Peter Lang.

- Chatterton, P. (2008). Demand the possible: Journeys in changing our world as a public activist-scholar. Antipode, 40(3), 421–427. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2008.00609.x

- Cloud, D. (2007). Making histories: Radical rhetoric and the labor of the scholar. JAC, 27(1/2), 351–365.

- Connaughton, S. L., Linabary, J. R., Krishna, A., Kuang, K., Anaele, A., Vibber, K. S., Yakova, L., & Jones, C. (2017). Explicating the relationally attentive approach to conducting engaged communication scholarship. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 45(5), 517–536. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00909882.2017.1382707

- De Jong, W., Shaw, M., & Stammers, N. (2005). Global activism, global media. Pluto Press.

- Dempsey, S., Dutta, M., Frey, L. R., Goodall, H. L., Madison, D. S., Mercieca, J., Nakayama, T., & Miller, K. (2011). What is the role of the communication discipline in social justice, community engagement, and public scholarship? A visit to the CM café. Communication Monographs, 78(2), 256–271. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2011.565062

- Dutta, M. J. (2011). Communicating social change: Structure, culture, and agency. Routledge.

- Dutta, M. J. (2020). Communication, culture and social change: Meaning, co-option, and resistance. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Freedman, D. (2017). Put a ring on it! Why we need more commitment in media scholarship. Javnost: The Public, 24(2), 186–197. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13183222.2017.1287963

- Freire, P. (1969). Pedagogıa del oprimido. Siglo XXI.

- Frey, L. R. (2009). What a difference more difference-making communication scholarship might make: Making a difference from and through communication research. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 37(2), 205–214. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00909880902792321

- Frey, L. R., & Carragee, K. M. (2007). Communication activism: Communication for social change. Hampton Press.

- Fuchs, C. (2016). Critical theory of communication. University of Westminster Press.

- Harry, B., Sturges, K. M., & Klinger, J. K. (2005). Mapping the process: An exemplar of process and challenge in grounded theory analysis. Educational Researcher, 34(2), 3–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X034002003

- Hotze, T. (2011). Identifying the challenges in community-based participatory research collaboration. The Virtual Mentor, 13(2), 105–108.

- Jansen, S. C. (2002). Critical communication theory: Power, media, gender, and technology. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Johnson, A. (2017). A communication approach to social justice: Midwest college campus protests. Howard Journal of Communications, 28(2), 212–215. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10646175.2017.1283261

- Kellner, D., & Kim, G. (2010). Youtube, critical pedagogy, and media activism. Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies, 32(1), 3–36. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10714410903482658

- Kindon, S., Pain, R., & Kesby, M. (2007). Participatory action research approaches and methods: Connecting people, participation, and place. Routledge.

- Lopez, L. K. (2015). A media campaign for ourselves: Building organizational media capacity through participatory action research. Journal of Media Practice, 16(3), 228–244. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14682753.2015.1116756

- Mitchell, K. (2008). Practicing public scholarship: Experiences and possibilities beyond the academy. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Pavarala, V., & Malik, K. (2007). Other voices: The struggle for community radio in India. Sage Publications.

- Quaye, S. J., Shaw, M. D., & Hill, D. C. (2017). Blending scholar and activist identities: Establishing the need for scholar-activism. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 10(4), 381–399. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000060

- Ramasubramanian, S., & Banjo, O. O. (2020). Critical media effects framework: Bridging critical cultural communication and media effects through power, intersectionality, context, and agency. Journal of Communication, 70(3), 379–400. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqaa014

- Redden, S. M., & Way, A. K. (2017). ‘Adults don’t understand’: Exploring how teens use dialectical frameworks to navigate webs of tensions in online life. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 45(1), 21–41. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00909882.2016.1248465

- Rodino-Colocino, M. (2011). Getting to “not especially strange”: Embracing participatory-advocacy communication research for social justice. International Journal of Communication, 5, 1699–1711.

- Routledge, P., & Derickson, K. D. (2015). Situated solidarities and the practice of scholar-activism. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 33(3), 391–407. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775815594308

- Skinner, D., Hackett, R., & Poyntz, S. R. (2015). Media activism and the academy, three cases: Media democracy day, open media, and NewsWatch Canada. Studies in Social Justice, 9(1), 86–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.26522/ssj.v9i1.1155

- Stringer, E. T. (2013). Action research. Sage Publications.

- Tracy, S. (2013). Qualitative research methods: Collective evidence, crafting analysis, communicating impact. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Waisbord, S. (2019). The communication manifesto. Wiley Press.

- Young, A. M., Battaglia, A., & Cloud, D. L. (2010). (Un)Disciplining the scholar-activist: Policing the boundaries of political engagement. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 96(4), 427–435. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00335630.2010.521179