Abstract

Embodied transnationalism is characterized by intimate experiences of human-made political borders that define, limit, and restrict flows of the “Other.” In the Quarantined Across Borders collection, contributors from immigrant and diasporic backgrounds address the material and discursive differences in how they experience the pandemic in terms of a public health crisis and public policy response that intersects racialized gender, class, citizenship status, and profession.

Quarantine. The word implies strict isolation, tight boundaries, or imposed confinement because of contagion – a communication of disease. The ‘Quarantined Across Borders’ (QAB) collection of personal essays features embodied and evocative narratives about the COVID-19 pandemic when authors use quarantine – as a mode of temporality, as a metaphor, and as a place-making marker of resilience and belonging – to describe connected experiences within borderland, immigrant, and diasporic communities. As editors, this collection echoes our experiences as women of color and immigrant scholars who navigate multiple cultures, identities, and spaces where our Brown and Black bodies have been scrutinized, restricted, or confined as contagion, long before the coronavirus came to our campuses.

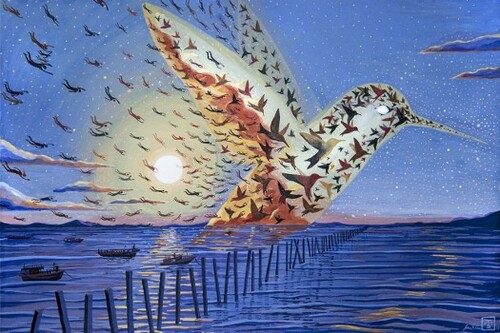

More than a hundred different species and colors of hummingbirds have been migrating from Central America across the Sonoran desert and back for thousands of years. The migratory journey of the hummingbird is an ancient cycle that outlives every border drawn by nation-states. Similar to the hummingbirds, the immigration of Black and Brown people of color is driven by the radical imagination of a future free of borders, incarceration and white-supremacy. As Black and Brown migrants and refugees soar and sail on their ships across the border, their bodies transform into hummingbirds. The friction of their solidarity forms a monumental hummingbird – the migrant justice movement – a living community that breathes, soars and imagines together. Our heart is beating three hundred times a minute. This piece was commissioned by Culture Strike for their campaign of the same name. It was partially inspired by the work done by Colibri Center For The Human Rights, an organization that works to end migrant death and related suffering on the US/Mexico border. Jessie X Snow (Citation2015). Reproduced with permission from the author. http://jessxsnow.com/UNTIL-WE-ALL-ARE-FREE

QAB is informed by transnational feminist thought whose intersectional approaches, developed by women of color, privilege experience to generate theory in the flesh and politically-imaginative knowledge forms to bear witness, incite, and move across communication and the academy (Anzaldúa, Citation2012; Calafell, Citation2007; Durham, Citation2020; Flores, Citation2019). For editors whose autoethnographic-informed research contributes to media effects (Ramasubramanian & Banjo, Citation2020), critical cultural studies (Durham, Citation2014), and organizational communication (Cruz & Sodeke, Citation2020), the QAB collection highlights the significance of centering the personal in applied communication as well. Srividya Ramasubramanian, for example, developed and curated a summer blog series called Quarantined Across Borders, as part of her nonprofit, Media Rise, which featured 84 short personal stories representing immigrant experiences from more than 30 countries. It was her creative-intellectual response to the rising coronavirus cases that not only brought together first-time bloggers and emerging communication scholars, but it also called attention to the unique experiences of immigrants under shelter-in-place, lockdown, and quarantine policies during the pandemic. The QAB blog series received more than 10,700 views within three months of its June 2020 launch.

Our roots/routes

Ramasubramanian created the series after reflecting on her transcontinental experience as a Brown Indian-American mother-scholar who left all that was familiar to her when she flew to a strange new country years ago as a new graduate. As a professor living in Texas today, Ramasubramanian recognizes the QAB blog series and the edited collection as a way to bridge gaps across borders and to build communities of care within and outside the academy. She would create these initiatives while worrying about and mourning the deaths of loved ones in coronavirus-ravaged Chennai. She would host virtual dialogues on COVID-19 inequalities and racial microaggressions while also checking in on international students separated from families. She would edit essays in-between caring for immuno-compromised family members and supporting unhoused immigrants in pandemic-hit Texas.

Ramasubramanian created the series after reflecting on her transcontinental experience as a Brown Indian-American mother-scholar who left all that was familiar to her when she flew to a strange new country years ago as a new graduate. As a professor living in Texas today, Ramasubramanian recognizes the QAB blog series and the edited collection as a way to bridge gaps across borders and to build communities of care within and outside the academy. She would create these initiatives while worrying about and mourning the deaths of loved ones in coronavirus-ravaged Chennai. She would host virtual dialogues on COVID-19 inequalities and racial microaggressions while also checking in on international students separated from families. She would edit essays in-between caring for immuno-compromised family members and supporting unhoused immigrants in pandemic-hit Texas.

The blog series reconnected Ramasubramanian with series and collection co-editors Aisha Durham and Joelle Cruz, whose distinct yet overlapping routes and roots as women of color helped to facilitate the cross-cultural conversations about COVID-19, quarantine, and diasporic and immigrant communities. Durham dealt with COVID-19 death blows, watching her masked family mourn loved ones from a virtual funeral feed in Florida. She would edit submissions in-between comforting family diagnosed and friends living with the sudden death of a parent from coronavirus. The precarity of Black life – from the pandemic and political unrest – is unsettling. Durham returned to her hooksian homeplace. The asthmatic-autoimmune-suppressed Black feminist settled in her gated-but-unguaranteed-safe home to edit essays and write with protesting Black students and faculty; she settled in her locked-but-not-police-proofed car snaking the same maskless-filled Trump stump-speech stadium for virus testing. In either case, gendered racism has compounded the personal, familial, and communal health of Black people during the pandemic.

The blog series reconnected Ramasubramanian with series and collection co-editors Aisha Durham and Joelle Cruz, whose distinct yet overlapping routes and roots as women of color helped to facilitate the cross-cultural conversations about COVID-19, quarantine, and diasporic and immigrant communities. Durham dealt with COVID-19 death blows, watching her masked family mourn loved ones from a virtual funeral feed in Florida. She would edit submissions in-between comforting family diagnosed and friends living with the sudden death of a parent from coronavirus. The precarity of Black life – from the pandemic and political unrest – is unsettling. Durham returned to her hooksian homeplace. The asthmatic-autoimmune-suppressed Black feminist settled in her gated-but-unguaranteed-safe home to edit essays and write with protesting Black students and faculty; she settled in her locked-but-not-police-proofed car snaking the same maskless-filled Trump stump-speech stadium for virus testing. In either case, gendered racism has compounded the personal, familial, and communal health of Black people during the pandemic.

Like Durham, Joëlle Cruz is a Black woman. Of Ivorian and French descent, she is all too familiar with immigration processes in the United States. She migrated here 12 years ago for graduate school and remained in the country after securing a faculty position. A green card holder at this point, she has held multiple students and work visas as well as a temporary work permit. She sees herself as a transnational subject, with roots in Africa, Europe, and North America. Given her positionality, Cruz has been impacted by COVID-19 as she is unable to travel both to France and Côte d'Ivoire to visit family and attend important events, including a wedding. She finds herself currently ‘locked in’ in Colorado. And, it is with this intimate feminist lens that Ramasubramanian, Durham, and Cruz circle from the self-outward – reaching back and reaching out to explore privilege, precarity, pain, and possibility across distinct yet connected communities under quarantine.

Like Durham, Joëlle Cruz is a Black woman. Of Ivorian and French descent, she is all too familiar with immigration processes in the United States. She migrated here 12 years ago for graduate school and remained in the country after securing a faculty position. A green card holder at this point, she has held multiple students and work visas as well as a temporary work permit. She sees herself as a transnational subject, with roots in Africa, Europe, and North America. Given her positionality, Cruz has been impacted by COVID-19 as she is unable to travel both to France and Côte d'Ivoire to visit family and attend important events, including a wedding. She finds herself currently ‘locked in’ in Colorado. And, it is with this intimate feminist lens that Ramasubramanian, Durham, and Cruz circle from the self-outward – reaching back and reaching out to explore privilege, precarity, pain, and possibility across distinct yet connected communities under quarantine.

Embodied transnationalism

There is no continent that escapes coronavirus. By year’s end, COVID-19 will kill almost two million people globally (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, Citation2020). Behind the body count are human beings. The QAB collection honors the experiences of feelings, relationships, and dreams of lovers and loved ones. It serves as an online applied communication intervention for collective healing and public memory-making. We are grateful to serve as guest editors of the inaugural ‘Communication Intervention’ for the Journal of Applied Communication Research. ‘Communication Intervention’ is an appropriate online multimedia forum where we could expand earlier conversations about coronavirus and community with rich multimedia content to enrich reader engagement with COVID-19 and closely connect with readers about the intimacies of quarantine.

In curating the collection, we identified different tapestries that make up QAB. The central thread is embodied transnationalism. Embodied transnationalism is characterized by intimate experiences of human-made political borders that define, limit, and restrict flows of the ‘Other.’ In the collection, contributors from immigrant and diasporic backgrounds address the material and discursive differences in how they experience the pandemic in terms of a public health crisis and public policy response that intersects racialized gender, class, citizenship status, and profession. Here, embodied transnationalism is contextual, situated, political, and temporal. In addition to marking the place-making aspect of quarantine as immigrant and diasporic persons, contributors consider the discursive construction of mediated and face-to-face communication, the real and the virtual, and humankind and nature. In each essay, the contributors address the ways borders can separate and create new connections rooted in embodied transnationalism.

Overview of the essays

For many contributors, the pandemic poses a deeper exploration of marginalization for communities of color. At different moments, we are racially marked as bodies that are alien, diseased, and dangerous. The language of ‘lockdown’ and ‘shelter-in-place’ can be especially triggering for communities of color who are disproportionately incarcerated and detained by state authorities. In the United States of America, for example, the Trump administration has aggressively promoted anti-immigrant policies such as family separation, forced sterilization, indefinite detention, travel bans, and a southern border wall to restrict the movement of migrants. Due to systemic discrimination as a ‘pre-existing condition,’ the COVID-19 pandemic had compounding impacts on those with precarious citizenship.

Yagnya Valkya Misra, for example, describes the political-economic impact of the pandemic on Indian migrant laborers walking from cities to rural hometowns. That Misra peers from the window to watch migrants on the move is a class distinction that Valentina Aduen Ramirez underscores in her essay. Ramirez describes the precarity and vulnerability of citizenship as a Colombian-American witnessing discrimination of her Latina friend, deemed an essential worker yet demeaned as ‘disposable’ after contracting coronavirus. Like Misra and Ramirez, Ryan Arron D’Souza explores the complexity of precarity and privilege as a person of color performing the banality of ‘normal routines’ as a consumer rather than as the essential worker that Ramirez describes. D’Souza highlights racial positional precarity for Black and Brown bodies, who are perceived as threats when wearing masks under U.S. antiblack racist and racist regimes. Together, these essays invite us to consider who can shelter-in-place or quarantine, and how we can share a similar racialized space with different experiences of displacement and confinement under the pandemic.

The immigrant and diasporic body that D’Souza, Misra, and Ramirez identify is not just displaced but is framed as a racialized threat. David Oh draws on his experiences as a Korean-American when he connects the ‘yellow peril’ stereotype with the Asian body as a site of disease to address increased anti-Asian violence, including microaggressions in the white academy. Satveer Kaur-Gill extends this discussion within a Singaporean context when addressing the stigmatization of the epidemic(ed) migrant travelers. Kaur-Gill analyzes mediated frames of ‘virus natives’ as ‘biopolitical sites for exclusion.’ These are space-specific frames, considering Emi Kanemoto and Sasha Allgayer provide an intercultural conversation comparing their mask-wearing experiences in Bosnia–Herzegovina and the United States where they are seen as a symbol of disease and threat, with Japan, where facemasks have historically been protective signs of care.

While the space-specific conversations about shelter-in-place and quarantine are associated with closure, QAB contributors also offer new possibilities for theorizing – forming communities and building resilience. Emi Kanemoto and Sasha Allgayer do so with dialogic collaborative autoethnography. They echo other contributors who suture embodied transnationalism by theorizing the pandemic from their flesh. They use narrative, poetics, and dialogue to make sense of borders and belonging. Take Diana Kasem. Kasem reframes the quarantine period as a time for regeneration – reflecting on the displacement of Syrian refugees due to civil war. She talks about how technology such as documentaries and video games can be used as a way to ‘talk back’ and build resilience among immigrant communities. Similarly, Newly Paul also sees the quarantine as a time to bring a sense of community, connection, and comfort. She does so by connecting with other Bengali food-lovers and trying out recipes that remind them of their home. Similar to Kasem and Paul, Weisong Gao and Marilia Kaisar see shelter-in-place as a time for critical reflection. Gao argues that the pandemic is a fundamental cross-continental experience that can reconfigure diasporic subjectivities while Kaisar explores disconnecting in a hypermediated world, theorizing in-betweenness as she connects back with nature.

Concluding thoughts

Collectively, the personal essays invite us to see QAB as a mismatched narrative quilt textured by the distinct experiences of immigrant and diasporic communities that creatively story embodied theory. It is a patchwork of our everyday experiences in a global pandemic. It is a diasporic diary, a glimpse into our souls, and a poetic salve for coping with chronic trauma. It is an archive of collective memory, a collage of cultural snapshots, and a shared space for sensemaking. Through public archiving and collaborative storytelling, we hope this community-based communication intervention affirms minoritized experiences, centers immigrant perspectives, and brings about collective healing.

If the quarantine has taught us anything, it is that we need to extend more grace and kindness to one another. Despite limited energies, competing priorities, and increased care labor, these contributors have created time and space for these essays. It has reaffirmed the importance of writing our histories from our own perspectives as minoritized scholars and citizens. From the contributors and the collaborative effort to produce this collection, we know quarantine can be a generative moment that helps us redefine, reframe, and re-imagine theorizing from the flesh. As Moraga and Anzaldúa state, ‘A theory in the flesh means one where the physical realities of our lives – our skin color, the land or concrete we grew up on, our sexual longings – all fuse to create a politics born out of necessity’ (Citation1981, p. 23). In a way, the authors of these essays all weave theoretical insights from the positionality of their diasporic bodies. In doing so, they invite us to draw strength, hope, and healing from their stories. We hope they inspire us to work collectively toward a more just, equitable, healthy, and humane world, during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic.

Acknowledgments

We want to take this opportunity to thank Dr Mohan Dutta for carving space for us to curate this collection. Thanks to Ondine Godtschalk, Emily Riewestahl, Anthony R. Ramirez, Olivia Osteen, and Miranda Calderon for their editorial and production assistance. Special thanks to the Melbern Glasscock Center for Humanities and the Texas A&M digital librarians for their support for the initial blog series. Most of all, our thanks to all the authors for their contributions and to the online Media Rise Community group for their support for this project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Anzaldúa, G. (2012). Borderlands/La Frontera: The new mestiza. 25th Anniversary. Aunt Lute Books.

- Calafell, B. M. (2007). Latina/o communication studies: Theorizing performance. Peter Lang.

- Cruz, J. M., & Sodeke, C. U. (2020). Debunking eurocentrism in organizational communication theory: Marginality and liquidities in postcolonial contexts. Communication Theory. https://doi.org/10.1093/ct/qtz038

- Durham, A. (2014). At home with hip hop feminism: Performances in communication and culture. Peter Lang Publishing Group.

- Durham, A. (2020). Black feminist thought, intersectionality, and intercultural communication. In S. Eguchi, B. Calafell, & S. Abdi (Eds.), Intersectionality: Race, intercultural communication, and politics (pp. 45–57). Lexington Books.

- Flores, L. A. (2019). At the intersections: Feminist border theory. Women’s Studies in Communication, 42(2), 113–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/07491409.2019.1605127

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. (2020, November 8). COVID-19 projections. University of Washington. https://covid19.healthdata.org/global?view=total-deaths&tab=trend

- Jessie X Snow. (2015). Until we all are free. http://jessxsnow.com/UNTIL-WE-ALL-ARE-FREE

- Moraga, C., & Anzaldúa, G. (1981). Theory in the flesh. In G. Anzaldúa & C. Moraga (Eds.), This bridge called my back: Writings by radical women of color (pp. 23–24). Persaphone Editions.

- Ramasubramanian, S., & Banjo, O. O. (2020). Critical media effects framework: Bridging critical cultural communication and media effects through power, intersectionality, context, and agency. Journal of Communication, 70(3), 379–400. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqaa014