ABSTRACT

This paper explores pig husbandry across the Aegean and Anatolia based on zooarchaeological data and ancient texts. The western Anatolian citadel of Kaymakçı is the departure point for discussion, as it sits in the Mycenaean-Hittite interaction zone and provides a uniquely large assemblage of pig bones. NISP, mortality, and biometric data from 38 additional sites across Greece and Anatolia allows observation of intra- and interregional variation in the role of pigs in subsistence economies, pig management, and pig size characteristics. Results show that, first, pig abundance at Kaymakçı matches Mycenaean and northern Aegean sites more closely than central, southern, and southeastern Anatolian sites; second, pig mortality data and biometry suggest multiple husbandry strategies and pig populations at Kaymakçı, but other explanations cannot yet be excluded; and, third, for the Aegean and Anatolia during the Late Bronze Age more generally, pig data suggests pluriformity, which challenges the use of “pig principles” in this region.

Introduction

In early state societies, domestic animals supported growing populations, enabled the accumulation of wealth, fueled hierarchical systems, and fulfilled symbolic roles (e.g., DeFrance Citation2009; Russell Citation2011; Zeder Citation1991). Late Bronze Age (LBA, ca. 1650–1200 b.c.) societies in Greece and Anatolia met the growing demand for animal resources by centralizing and intensifying their animal economies, resulting in large-scale production and distribution of meat, wool, hides, working oxen, and other animal goods (Halstead Citation1993, Citation2011; Shelton Citation2010; Berthon Citation2017). The ubiquity of sheep, goats, and cattle in LBA texts and faunal assemblages suggests that these animals formed the backbone of Mycenaean and Hittite economies (e.g., Halstead Citation1999; Dörfler et al. Citation2011). Pigs, although highly efficient meat providers, were not always a recognized part of these economic systems. Pigs feature sporadically in the Mycenaean and Hittite texts, and their bones occur less frequently in faunal assemblages than sheep, goat, and cattle bones (Trantalidou Citation1990; Halstead Citation1999; Dörfler et al. Citation2011).

For Near Eastern early state societies, the scarcity of pig bones has been explained by “pig principles,” summarized by Hesse and Wapnish (Citation1998, 125–126). These include the unattractiveness of pigs in centralized systems, physiological/behavioral complications of pig herding, and a pork taboo (Zeder Citation1991, Citation1998; Redding Citation1991, Citation2015). Pigs were instead considered a more suitable food source for rural and/or remote settlements, which relied on locally and loosely organized forms of subsistence (e.g., Zeder Citation1991, Citation1998; Price, Grossman, and Paulette Citation2017). Only recently, studies in northern Mesopotamia demonstrated that the economic importance of pigs was wider spread across early urban contexts than previously thought (Grigson Citation2007; Berthon Citation2014; Price and Evin Citation2017; Gaastra, Greenfield, and Greenfield Citationin press).

The “pig principles” appear to have explicitly and implicitly shaped pig research in both the Aegean and Anatolia (e.g., Arbuckle Citation2009; Berthon Citation2014; Fillios Citation2007; Grigson Citation2007; Macheridis Citation2018). Together with the relatively small numbers of pig bones, excavations predominantly taking place at large settlements, and ancient texts emphasizing administrative concerns only (Halstead Citation1999, Citation2003), pigs in the Aegean and Anatolian LBA have therefore received little scholarly attention. It is, however, unclear whether the “pig principles” are applicable to the Aegean and Anatolia. Investigating this issue becomes more pressing from the Middle Bronze Age onwards, firstly because Greece and Anatolia have recently become hot spots for ancient DNA (aDNA) studies investigating the introduction of European pigs into Anatolia and the Levant in the Bronze Age (e.g., Ottoni et al. Citation2013; Frantz et al. Citation2019), and secondly because much remains unknown about husbandry strategies in Greece and Anatolia prior to the heavily debated environmental and political changes around 1200 b.c. (e.g., Drake Citation2012; Kaniewski et al. Citation2013; Knapp and Manning Citation2016). At the same time, investigating pig husbandry in this region has become more feasible. Zooarchaeological methods are advancing, with the potential to extract more information from less material, and recent and ongoing excavations increase the quantity of faunal assemblages available for regional comparison.

The pig bones retrieved from recent excavations at the LBA citadel of Kaymakçı in western Anatolia form a unique starting point to address the characteristics of pig husbandry in this region. Kaymakçı is a key site in this investigation for two reasons. Firstly, Kaymakçı is the largest currently known and excavated citadel site in western Anatolia, and it provides an intermediary point of investigation for animal husbandry across the Aegean and Anatolia because of its location in the Hittite-Mycenaean interaction interface (Roosevelt et al. Citation2015, Citation2018). Secondly, work at Kaymakçı has followed high standards for faunal recovery and analysis (Roosevelt et al. Citation2018).

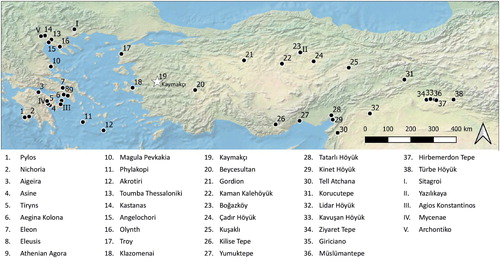

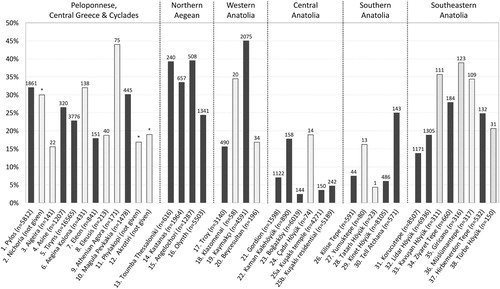

We recently demonstrated how animal subsistence in Kaymakçı depended on mixed husbandry, fishing, hunting, and, to a lesser degree, fowling, but pig exploitation was a dominant component (Roosevelt et al. Citation2018). This is intriguing, because Kaymakçı’s environs could well have sustained pastoralist systems with large sheep, goat, and cattle herds, a feature often associated with large regional Bronze Age centers in southwest Asia (e.g., Arbuckle and Hammer Citation2019). In this paper, we examine the characteristics of pig husbandry in Kaymakçı and extend our analysis to an exploration of pig husbandry in 38 archaeological sites across LBA Greece and Anatolia (; see Supplemental Material 1 for references to sites). We embed our study in an overview of textual references to pigs and previous zooarchaeological research on pig husbandry in the region. Relative abundance, kill-off, and biometric data allow us to investigate the role of pigs in subsistence, strategies to manage them, and the appearance of pig populations, whereas the synthesis of textual references allows us to reflect on the applicability of “pig principles” in the Aegean and Anatolia. Results show, first, that pig abundance at Kaymakçı matches Mycenaean and northern Aegean sites more closely than central, southern, and southeastern Anatolian sites; second, mortality data and biometry suggest multiple husbandry strategies and pluriform pig populations at Kaymakçı, though other explanations cannot yet be excluded; and, third, pluriformity of pig husbandry appears to be characteristic for LBA Anatolia and Greece more generally, which challenges the assumptions of the “pig principles.”

Late Bronze Age Pig Husbandry in Text and Bone

Mycenaean and northern Greece

Mycenaean texts mention sheep and goats frequently and in flocks of thousands (Halstead Citation1999). Because texts mention pigs considerably less frequently, they give the impression that pigs were a less numerous livestock (Halstead Citation1993, Citation1999). The zooarchaeological evidence suggests otherwise. Roughly half of the meat consumed at important Mycenaean centers such as Nichoria, Tiryns, and Pylos derived from pigs and cattle (Halstead Citation1993, Citation1999, Citation2003). How meat was produced, however, differed among the centers. At Tiryns, three quarters of the pig population was culled immaturely (Trantalidou Citation1990; von den Driesch and Boessneck Citation1990). At Pylos, most pigs were adult when culled, and, based on canine counts, males outnumbered females by 2.5:1 (Nobis Citation1993), precluding intensive pork exploitation strategies. This evidence has been alternatively interpreted as mismanagement or lack of know-how (Nobis Citation1993).

Pigs in Linear B texts from Pylos, Tiryns, and Mycenae are specified by age and sex (male, female, possible castrates; Rougemont Citation2006). The written record is also clear about centers levying pigs for slaughter, pig fat, and pig hides from small local authorities as taxation, suggesting at least some pigs were produced away from regional centers and provisioned to the cities (Halstead Citation2011). Fattened pigs (sialos = “fattened animal,” a-se-so-si = “fattening,” (h)opa = “to apply to,” SUS + KI = “fattened pig”) were allocated to banquets, festivities, and offerings, underlining that pigs fulfilled symbolic, as well as economic, roles (Rougemont Citation2006; Halstead and Isaakidou Citation2017). Archaeological evidence for pig offerings and cult meals were found at Ayios Konstantinos (Hamilakis and Konsolaki Citation2004), in the Cult Center complex at Mycenae (Price, Krigbaum, and Shelton Citation2017), and possibly in the Palace of Nestor at Pylos (Isaakidou et al. Citation2002).

Texts detail diets to fatten pigs, which include barley and other vegetal ingredients (Rougemont Citation2006). Isotope analysis of pig remains in Mycenaean Greece may provide interesting insights into these fattening practices. In Mycenae, δ15N values in pig bones from the Cult Center indicate a vegetal diet for sacrificial pigs, whereas the elevated δ15N values of the pigs from the industrial residence of the Petsas House are consistent with an enriched diet (Price, Krigbaum, and Shelton Citation2017). Whereas differences in δ15N may indicate dietary differences between wild boar and domestic pigs, vegetal diets may likewise designate controlled fattening practices (Price, Krigbaum, and Shelton Citation2017) or herding. The enriched diets of Petsas House pigs indicate they were likely scavenging on settlement waste or reared in households (e.g., Hamilton, Hedges, and Robinson Citation2009; Balasse et al. Citation2018). Household rearing of pigs in Greece was also suggested for Akrotiri by Gamble (Citation1978, 752; Citation1982).

Subsistence in northern Greece, where no texts have been found, differed from the Mycenaean mainland, relying more on wild animals and mixed animal husbandry in which pigs were very common (Becker Citation1986; Creuzieux et al. Citation2014; Vasileiadou Citation2009). In Archontiko and Thessaloniki Toumba, differential access of pigs to herbivorous and omnivorous diets, inferred from δ15N values, suggests different pig husbandry systems may have co-existed locally (Nitsch et al. Citation2017).

Central and southeastern Anatolia

In the Hittite realm, the scarcity of pig bones has led scholars to suggest that pig husbandry was limited (Dörfler et al. Citation2011). Especially at the Hittite capital of Boğazköy and the large cult center at Kuşaklı, pig bones were rare (less than 5% of identified specimens; von den Driesch and Vagedes Citation1997; von den Driesch and Pöllath Citation2004). As recently suggested by Berthon (Citation2017), Hittite pig husbandry may have been more varied. Pigs were, for example, reared and consumed at Kaman Kalehöyük (17% of identified specimens; Hongo Citation1996, 67), a large agricultural center (Hongo Citation1996, 154; Fairbairn and Omura Citation2005). The frequencies of pig bones appear low in sites south of the Hittite heartland, too, between 4–16% (Baker Citation2008; Ikram, Çakırlar, and Kabiatar Citationforthcoming; Minniti Citation2014; Silibolatlaz and Serdar Girginer Citation2018), but on the southern and southeastern fringes of the Hittite realm, in Alalakh, Lidar Höyük, and Korucutepe, pig bones appear to occur more frequently (14–25%) (Boessneck and von den Driesch Citation1975; Çakırlar et al. Citation2014; Kussinger Citation1988). Beyond the eastern border of the Hittite realm, Berthon (Citation2014) reported a structural inclusion of pigs (between 20–40%) in subsistence strategies at Mitannian centers in rural and well-watered areas.

Although pig bones are rare in most Hittite assemblages, Hittite texts provide ample information about the social connotations, economic uses, husbandry strategies, and symbolic roles of pigs in the Hittite world (Hoffner Citation1974, 64). The Hittite Law Code prohibited physical contact with and consumption of pigs that scavenged on street waste, whereas other pigs were reared on grain and kept in special enclosures to produce fat and meat (LÚMEŠ SIPAD.ŠAḪ) (Collins Citation2006; Hoffner Citation1974, 65; Klengel Citation2007). Price lists for pig fat (Ì.ŠAḪ.DÙG.GA = “good pork fat”, 1 shekel), used in perfume production and medicine, suggest pig fat trade was important enough to be centrally administered (Alparslan Citation2013, 511; Klengel Citation2007, 161). Pig management also required central regulation: pig theft and damage to fields caused by pigs were fined (Collins Citation2006; Klengel Citation2007).

Piglet sacrifice (or clay/bread substitutes) appears to have been a favored medium during festivals and magic rituals to heal diseases and impurity, stimulate fertility and arability, absolve law offenders, and ward off evil (Hoffner Citation1974; Collins Citation2006; Mouton Citation2017). In some cases, black-coated piglets were specifically prescribed (Collins Citation2006). A piglet burial at Yazılıkaya probably represents one of these ritual uses (Hauptmann Citation1975).

Western Anatolia

Western Anatolia was an important interaction zone for cultural exchange, competition, and conflict between the Mycenaean and Hittite worlds (e.g., Mountjoy Citation1998; Greaves Citation2012; Roosevelt et al. Citation2018). Local kingdoms in western Anatolia negotiated diplomatic relations with Hittite and Mycenaean traders and troops, though much remains unknown about the cultural affiliations and habits of the people that lived in the region itself. Archaeological investigations into the LBA in western Anatolia long lagged behind those in Greece and central Anatolia, but recent and ongoing excavations are slowly shedding new light on this interaction zone (e.g., Dedeoğlu and Abay Citation2014; Erkanal Citation2008; Günel Citation2010; Mangaloğlu-Votruba Citation2015; Meriç and Öz Citation2015; Pavúk Citation2014; Roosevelt and Luke Citation2017).

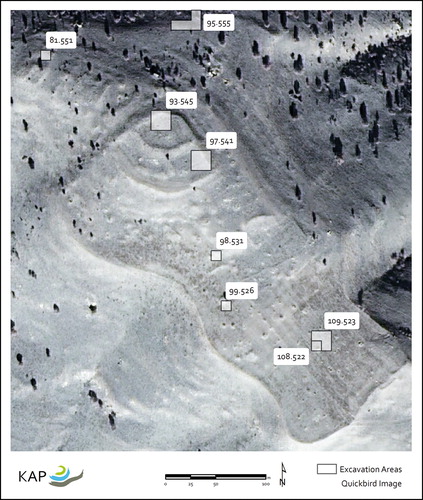

The Kaymakçı Archaeological Project (KAP) plays a leading role in reconstructing protohistoric western Anatolia. If current understandings of LBA historical geography are correct, the Marmara Lake basin and the Gediz River valley, which Kaymakçı overlooks (), composed the core of the Seha River Land, an indigenous kingdom of the Arzawa Lands of western Anatolia that eventually became a Hittite vassal around the 14th century b.c. (Hawkins Citation1998; Mac Sweeney Citation2010; Gander Citation2017). According to the Boğazköy archives, the kings of the Seha River Land continuously negotiated a buffer position between Hittite and Ahhiyawan (or Mycenaean) interests in western Anatolia (Bryce Citation1989, Citation2012; Roosevelt Citation2010; Roosevelt and Luke Citation2017). Kaymakçı is at present the best candidate for their capital.

Figure 2. View from the inner citadel of Kaymakçı to the southeast, with the Marmara Lake basin to the left and Gediz River Valley to the right (© Gygaia Projects).

Excavations at Kaymakçı

Kaymakçı is just one of 34 sites dating to the 2nd millennium b.c. located in the Marmara Lake Basin (Luke et al. Citation2015). Most of these sites are small and dispersed across the landscape with no clear relation to each other. Five clustered settlement nodes in the lowlands, however, and six fortified citadels in the uplands were observed (Luke and Roosevelt Citation2016, Citation2017; Roosevelt and Luke Citation2017). Kaymakçı is the largest (8.6 ha) of these citadels and possibly in western Anatolia. The size and the complexity of the settlement plan suggests hierarchical and functional differentiation, setting it apart from other citadels in the region (Roosevelt et al. Citation2018).

Excavations at Kaymakçı commenced in 2014 to explore the chronology, spatial organization, production activities, interregional interactions, paleoenvironment, and subsistence economies of the site, with particular attention to its intermediary position between the Hittite and Mycenaean worlds (Roosevelt et al. Citation2018). Kaymakçı is the only excavation in this area focusing on the Middle and Late Bronze Ages. Creating robust primary datasets with reproducible environmental data (e.g., archaeobotanical and zooarchaeological), which were notably scarce in the archaeology of the Gediz River Valley, is one of the primary aims of the project (Roosevelt et al. Citation2018).

For the nearby Iron Age city of Sardis, ancient Greek authors have written that the rivers and lakes of Lydia abounded in wild fish, fowl, and other game and that sheep, goats, and cattle grazed in fields in valleys and highland pastures (Roosevelt Citation2009, 53–54, 70). Preliminary reports on fauna at Sardis concur with this depiction (e.g., Deniz, Çalışlar, and Özgüden Citation1964; Hanfmann and Foss Citation1983, 6) and suggest that the Gediz Valley supported a wide variety of wild animals and plants and allowed multiple strategies for animal husbandry.

Material and Methods

Kaymakçı

Faunal samples primarily derive from waste deposits in the inner citadel, the southern terrace, and around the fortification wall excavated between 2014 and 2017 (, ); from a selection of these deposits additional samples were excavated and studied in 2018 and 2019. We excluded animal remains from symbolic contexts; in the case of pigs, this concerned piglets found in relation to intramural human infant burials (Roosevelt et al. Citation2018). Analyzed animal bones were collected through handpicking and dry sieving (4 mm mesh) to minimize recovery bias against medium-sized and small vertebrates (Payne Citation1972). Consistent percentages of unidentified specimens per area suggest that handpicked and sieved samples were similarly fragmented, but percentages of unidentified specimens were generally higher for samples from around the settlement’s fortification wall, possibly due to heavier fragmentation caused by downslope wash.

Figure 3. Plan of the citadel of Kaymakçı showing the eight excavation areas opened from 2014–2017 (© Gygaia Projects).

Table 1. Overview of identified specimens per excavation area.

Samples were studied using a comparative collection containing several pigs, sheep, and goats of neonate, juvenile, and adult ages, cattle, roe-, red-, and fallow deer, marten, dog, fox, hare, carp, catfish, and various identification manuals (e.g., Schmidt Citation1972). We recorded taxonomy, element, side, completeness, sex (canine morphology; Schmidt Citation1972), tooth wear stages following Grant (Citation1982), epiphyseal fusion (unfused, fusion line visible, fusion line not visible), biometric dimensions (following von den Driesch Citation1976; Payne and Bull Citation1988), traces of pathological conditions, and taphonomic markers. Elements with diagnostic features such as articular surfaces (sensu Watson Citation1979) were identified to species when possible.

Data analysis aimed to estimate relative abundance, reveal kill-off patterns, and reconstruct body and molar size for pigs. Relative abundance of taxa was calculated based on the Number of Identified Specimens (NISP) (Davis Citation1987, 35) to infer the economic significance of taxa. Kill-off patterns were reconstructed based on tooth wear and epiphyseal fusion using Lemoine and colleagues (Citation2014) and Zeder, Lemoine, and Payne (Citation2015); ages of perinatal pigs were estimated using Habermehl (Citation1975). Seasonality was inferred following Wright and colleagues (Citation2014). Differential targeting of sexes was investigated through counts of sexually dimorphic canines and body size.

Investigating bone and tooth size in archaeological populations is useful in determining the presence of domestic and wild animals and sex ratios at culling (Payne and Bull Citation1988; Albarella and Payne Citation2005). As bone dimensions are influenced by growth and sexual dimorphism, they can be used to estimate sex ratios within a single population (Payne and Bull Citation1988; Albarella and Payne Citation2005). Tooth dimensions can detect variation between populations more reliably than bone measurements, as teeth dimensions are less affected by age, sex, and health, and preserve better; however, severe wear and developmental problems may distort tooth size, and wild and domestic sizes may overlap (e.g., Payne and Bull Citation1988; Albarella Citation2002; Albarella and Payne Citation2005; Albarella, Dobney, and Rowley-Conwy Citation2009; Evin et al. Citation2013, Citation2015; Balasse et al. Citation2016). Here we excluded measurements of immature bones to minimize the effects of growth.

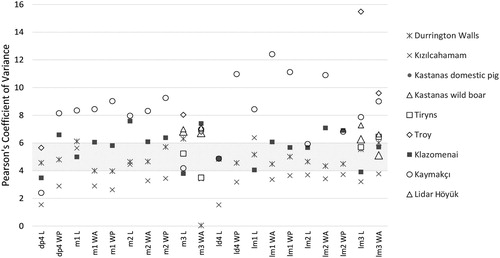

Measurements were computed into Logarithmic Size Indices (LSI = log(x/m)), sensu Meadow (Citation1999), where x represents the specimen measurement and m represents the dimension of a standard, in this case the average size of modern central Anatolian male and female wild boar (Payne and Bull Citation1988). Size characteristics of the population were assessed through the shape and spread of LSI distributions. The presence of different size groups was investigated with cluster analysis of raw measurements; for this, a Gaussian Mixture analysis was run in R, which uses a probabilistic model-fitting algorithm to estimate clusters based on a Bayesian Information Criterion (mclust; Scrucca et al. Citation2016). Finally, we estimated the range of variation within Kaymakçı’s pig teeth measurements through Pearson’s Coefficient of Variation (CV = s/x¯). CV values between 4 and 6, reflecting normal genetic and phenotypic variation within a single animal population, were expected (Simpson et al. Citation1960, 259–265; Albarella and Payne Citation2005; Albarella, Dobney, and Rowley-Conwy Citation2009).

Comparative data

Comparative analysis is based on published zooarchaeological data from Greece and Turkey and primary data from Kaymakçı, Troy, and Klazomenai in western Anatolia and Gordion in central Anatolia. To get an impression about the relative and differential importance of pigs in diet and economy across Greece and Turkey, we looked at the relative abundance of pig bones (in comparison to sheep, goats, and cattle) in terms of NISP. For this, we took the quantitative units “specimen count,” “fragment count,” and “Fundzahl” used by various researchers to mean NISP. These units are traditionally well-published across various faunal studies in Greece and Anatolia and therefore altogether provide the largest comparative dataset. The disadvantages of using this type of data with different sample sizes coming from varied contexts and generated by different analysts are well-known (Cannon Citation2013), but there are simply no other comparative datasets to rely on. To mitigate biases imposed by contextual differences, data from known sanctuary and burial contexts were excluded, and only assemblages representing settlement waste were included in the analysis.

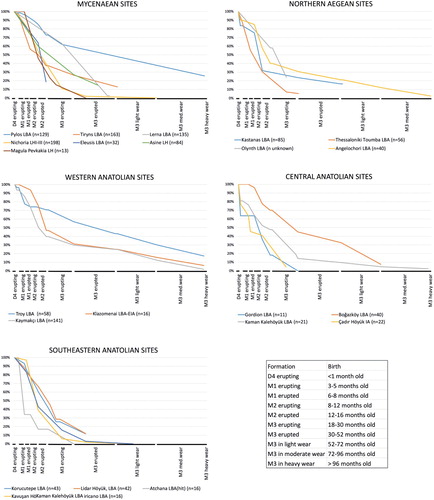

Summaries of kill-off and biometric data complemented the NISP data. Different recording techniques prohibited direct comparison, but tooth eruption and wear-based mortality data from 24 sites could be converted to Lemoine and colleagues’ simplified A-system (Citation2014). For publications pre-dating Grant’s tooth wear scheme (Citation1982), tooth eruption (erupting or erupted) and wear data (light, moderate, or heavy) were directly converted to this system. When pig mortality was presented only in age categories, these were compared to Payne stages (Payne Citation1987) and matched to Lemoine and colleagues’ simplified A-system (Citation2014).

Teeth and bone measurement data were available for 22 sites. Issues such as small sample size, inter-analyst measurement error, differing measurement procedures, and characteristics of assemblages can obstruct reconstructing size (Albarella Citation2002). Smaller samples were included for the sake of completeness. Measurements for Kastanas and Sitagroi were published for the EBA–EIA as a single period; these measurements were interpreted with caution, because throughout the Bronze Age, a size decline in pigs is observed in the northern Aegean (Becker Citation1986; Gardeisen Citation2010). Raw measurements were transformed into LSI values as explained above. Differences in size distributions of post-cranial bones and molars were tested using one-way ANOVAs (α = 0.05). Finally, the CV value was calculated for molar size to investigate intra-population variation for sites with > 50 measurements (Kastanas, Tiryns, Troy, Klazomenai, Kaymakçı, and Lidar Höyük). CV for molar measurements at Neolithic Durrington Walls and the Kızılcahamam modern wild boar were added as reference assemblages.

Results

Kaymakçı

relative abundance

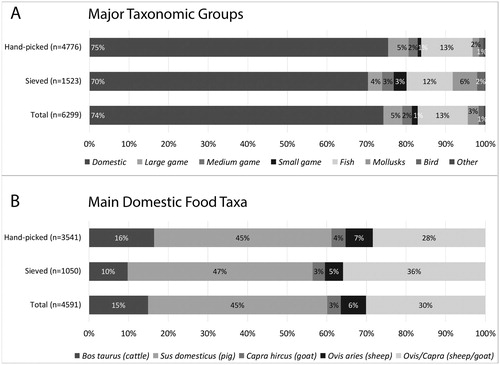

Remains of domestic taxa form 75–82% of the identified specimens in Kaymakçı’s hand-collected and dry-sieved assemblage, including pigs (Sus scrofa domesticus), sheep (Ovis aries), goats (Capra hircus), cattle (Bos taurus), and a small number of equids (Equus spp.) and dogs (Canis familiaris) (). Wild taxa represent 18–25% of the total NISP. Large game (63–65%) consists mostly of fallow deer (Dama dama) and red deer (Cervus elaphus). Other identified wild taxa include hare (Lepus europaeus), wild boar (Sus scrofa), fox (Vulpes vulpes), marten (Martes martes), and tortoise (Testudo sp.). Additionally, a mandible and tibia fragment of a brown bear (Ursus arctos) and a tibia and first phalanx of a large felid were retrieved from the inner citadel area 93.545. Fish remains make up 7–9% of the identified specimens and could be identified as either carp (Cyprinidae) or catfish (Siluridae). Of the identified mollusks, 32–42% are land snails; fresh-water mussels (Unionidae) and marine taxa also occur (see also Roosevelt et al. Citation2018). These relative amounts suggest that while the animal-based economy and diet at Kaymakçı depended primarily on husbandry, wild resources complemented farming substantially.

Of the main domesticates, remains of domestic pig (see the section on size below) dominate the specimen counts in both hand-picked and sieved samples from all excavation areas (NISP and Diagnostic Zone counts) by 45–47% () and occur in similar abundance over all excavation areas. Fetal and neonate pigs were twice as common in sieved samples as hand-picked samples (respectively, 10% and 4.5%). Sheep and goats are the second-most abundant at 38–44%, with sheep identified more often than goat by a ratio of 1.8:1. Cattle remains are least frequent, with 16% in hand-picked samples and 9% in sieved samples. Sheep and goat husbandry at Kaymakçı targeted mixed wool/fleece, milk, and meat, whereas the longevity of cattle indicated their value as working animals rather than as primarily meat stock (Roosevelt et al. Citation2018).

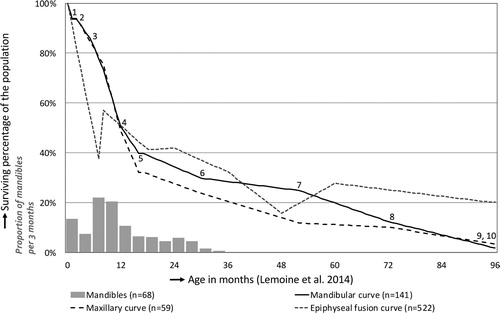

culling strategies

Mortality based on epiphyseal fusion shows a steep decline of the pig population from birth until 1.5 years old (). After this, the population declines at a slower pace. Mortality rates based on mandibular and maxillary tooth eruption and wear show a similar pattern: 60% of the pig population was culled during Lemoine and colleagues’ simplified A-system-stages 1–5, followed by a slow decline during stages 5–10. Season-of-death data, recorded in three month intervals for the first three years, demonstrates heightened mortality of 6–12 month-old pigs. If these pigs were born in spring, such culling may have taken place during autumn and winter. For 12–36 month-old pigs, specific mortality seasons were not detected.

Figure 5. Mortality data for pigs based on epiphyseal fusion (Zeder, Lemoine, and Payne Citation2015) and mandibular and maxillary tooth eruption and wear (classified A-system of Lemoine et al. Citation2014). Grey bars represent the season of death over the first three years, following Wright and colleagues (Citation2014).

The emphasis on culling young pigs at Kaymakçı indicates intensive husbandry, a strategy that generally includes culling immature pigs for (tender) pork while reserving more females than males for reproduction (Redding Citation1991, Citation2015). The ratios of male to female pig canines in the Kaymakçı assemblage are equal, however, with 17 male and 17 female specimens recorded. Not included in the mortality data in are 117 remains of fetal and neonate individuals, which were most frequently retrieved from the inner citadel (Areas 93.545 and 97.541) and the southern terrace (Area 99.526) (Supplemental Material 2). The abundance of these suggests that pregnant sows were kept within the settlement perimeter.

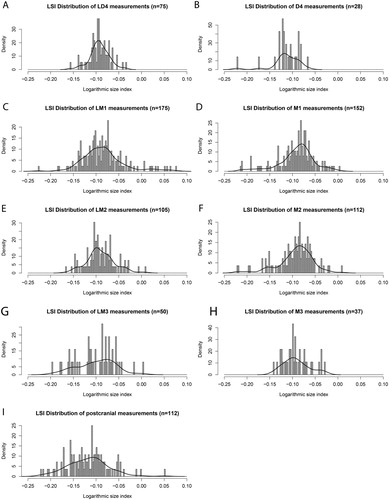

postcranial bone and molar size

Postcranial bone and tooth size indices indicate that nearly all pig specimens were of domestic size (). Wild boar-sized specimens occur sparsely. The postcranial bone size distribution is left-skewed and overlaps with the smaller sized molars in the assemblage. This indicates that most pigs were small-bodied, representing either a larger portion of females or possibly young animals, because early fusing elements are common in the assemblage (). The molar size distributions resemble the postcranial size shape and range. Most molar dimensions fall between -0.12 and -0.05, with left tails ranging between -0.12 and -0.20. Molars larger than -0.05 are infrequent, but more often occur in first molars than second and third, suggesting animals of this size were culled before their second and third molars were formed (). Whereas these larger sized animals may represent males or wild suids, neither the left tails observed in the upper molars and first and second lower molars nor the additional modes in the second and lower third molar distributions formed by these smaller specimens are distinct.

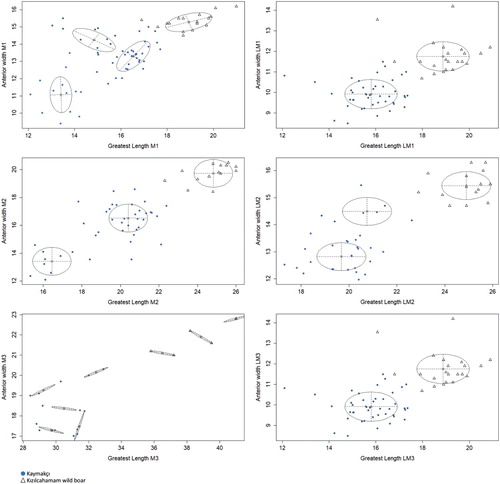

gaussian mixture and pearson’s coefficient of variation

Gaussian mixture analysis defines multiple clusters in Kaymakçı’s pig molar dimensions for all molars except the lower first molar, suggesting that the domestic-sized pig molars of Kaymakçı are phenotypically heterogeneous (). Minimal overlap among molar dimensions and clear distance between modern wild boar and Kaymakçı’s specimens make it difficult to interpret the apparent patterns as related to the presence of one domestic and one wild boar population. These different domestic-sized pig clusters are difficult to explain as sexual dimorphism, as overlap between the clusters is low, and molar size is supposedly only modestly sexually dimorphic in wild boar and domestic pig populations (Albarella and Payne Citation2005; Evin et al. Citation2015; Payne and Bull Citation1988). The Gaussian mixture analysis therefore appears to display separate domestic pig populations. Pearson’s CV values for molars concur with this inference, as most CV values fall between 8 and 12, exceeding normal variation expected within a single population (Supplemental Material 3). Only the CV values for deciduous and permanent upper third molar lengths fall within the boundaries of a single population; width measurements for these elements, however, also show CV values of 8–11.

Comparative data

relative abundance

The relative abundance of pigs across various assemblages are displayed in . Although sample sizes vary strongly, regional trends can be discerned. Proportions of pig bones in Mycenaean assemblages vary between 15–33%. The northern Aegean assemblages contain overall larger proportions of pigs (Toumba Thessaloniki: 38%; Kastanas: 34%; Anchelochori: 40%; Olynth: 24%). In western Anatolia, pig bones form 16–17% of domesticates at Troy and Beycesultan; however, the proportion of pigs at Kaymakçı (48%) and Klazomenai (35%) show values comparable to Mycenaean and northern Aegean assemblages. In central Anatolia, pigs are overall scarcer at Gordion (7%) and nearly absent at the Hittite centers of Boğazköy and Kuşaklı (2–4%), though the assemblages at Kaman-Kalehöyük and Çadır Höyük contain 17–18% pig remains. Proportions of pig bones remain low (< 8%) in southern Anatolia (8%), except at Yumuktepe (16%), Tell Atchana (25%), and Lidar Höyük (18%). In southeastern Anatolia, pig abundance increases regionally (between 16–38% in all assemblages).

culling strategies

Kill-off patterns vary across and within regions, ranging from steady declines in pig population throughout the first two years to gradually decreasing populations (). In the Mycenaean heartland, at Nichoria, Tiryns, Eleusis, Magula Pevkakia, and Asine, over 50% of the pigs were culled before third molars started erupting, suggesting most pigs were killed between 0–16 months old (following Lemoine et al. Citation2014). From Nichoria and Magula Pevkakia, no pigs beyond this age were reported. In contrast, the majority of pigs at Pylos were culled as adults.

Figure 9. Dentition-based pig mortality data for various LBA assemblages from Greece and Anatolia. Age estimations follow Lemoine and colleagues (2014).

In the northern Aegean, the sharp decline of pig population between 0 and 16 months at Thessaloniki Toumba is similar to most Mycenaean sites. However, at Olynth, Anchelochori, and Kastanas, larger portions of the pig populations reached adulthood. At Olynth, culling targeted juveniles and subadults, not infants. In Anchelochori and Kastanas, some pigs were culled (or died) as piglets, but intensive culling did not start before the lower second molar started erupting (8–12 months), possibly indicative of autumn/winter culling.

The situation in western Anatolia is different from Greece, as considerably larger portions of the populations reached adulthood. In Klazomenai, culling strategies were similar to Kaymakçı, focusing on pigs between 8–16 months. In Troy, however, pigs were targeted during the first half year of their life, but after that time, culling was spread over pigs of adult ages.

In central Anatolia, at Gordion, Çadır Höyük, and Kaman-Kalehöyük, 20–40% of the pigs were young piglets, and the remainder of the population was culled before the third molar erupted. Boğazköy’s assemblage differs: roughly half the pigs found in the assemblage had erupted third molars, and no remains of piglets younger than half a year old were recorded.

Southern and southeastern Anatolian sites uniformly show declining pig populations at young ages, with erupted third molars witnessed in only 10% of the population. Minor deviations are visible in the timing of culling activity. At Kavuşan Höyük and Giriciano, culling was directed at animals with erupting second molars (8–12 months old); at Korucutepe and Lidar Höyük, culling was spread evenly over pigs aged 0–2 years old, while at Tell Atchana, pigs aged 6–12 months old appear to have been targeted.

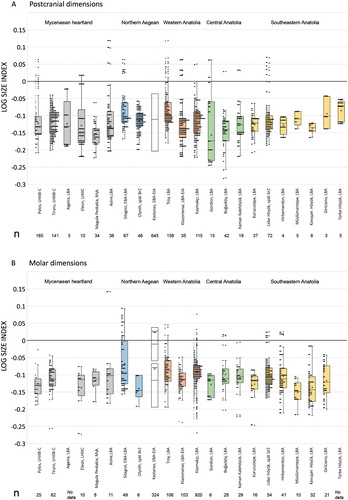

postcranial bone and molar size

Logarithmic size indices indicate that compared to modern Anatolian wild boar, all assemblages from southeastern Anatolia to Greece are dominated by remains from morphologically domestic pigs (; see Supplemental Material 4 for ANOVA). Wild boar-sized individuals are sparsely present in assemblages from Pylos, Asine, Troy, Kaymakçı, Gordion, Boğazköy, Lidar Höyük, and Hirbemerdon Tepe. The assemblages from Sitagroi and Kastanas include more wild boar, but measurements for these sites were published as lump samples spanning the EBA–EIA. Mycenaean pigs are uniform in body and molar sizes, except at Magula Pevkakia, where pigs were significantly smaller-bodied than at Tiryns and Pylos (p = 0.0017; p = 0.0000). Additionally, the mean size is smaller than the median for Magula Pevkakia, but also for Eleon, Asine, and Pylos. This skewing towards smaller individuals could suggest an overrepresentation of females, but may also be a result of young culling ages. In contrast, the closeness of the mean to the median at Tiryns, and the bimodal postcranial distribution for this site, despite intensive culling activity, suggests the Tiryns assemblage contains both males and females.

Figure 10. Boxplots and histograms of logarithmic size indices of pig measurements recorded at 2nd and 1st millennium b.c. sites in Greece and Turkey. The second and third quartiles are colored and separated by the median; x displays the mean. A) Postcranial measurements; B) Molar measurements. EBA = Early Bronze Age; LBA = Late Bronze Age; LHIIIB = Late Helladic IIIB; LHIIIC = Late Helladic IIIC; Spät BrZ = Späte Bronzezeit. Kastanas data is available as descriptive statistics only.

Discussing general trends in size for the northern Aegean is not possible, because LBA measurements were only published from Olynth. Olynth measurements are similar to those from Mycenaean Greece. Measurements in the multi-period sample from Sitagroi are significantly larger than those from Olynth (molar p = 0.022; postcranial p = 0.0005), reflecting diachronic variability in body and molar size.

In western Anatolia, postcranial and molar dimensions display inconsistent patterns. Pigs at Troy are generally larger-bodied than pigs at Klazomenai (p < 0.001), but molar size at Troy and Klazomenai is similar. The size range of pig bones and molars at Kaymakçı overlaps with both these sites, though, on average, molars are larger at Kaymakçı than at Troy and Klazomenai (p = 0.01; p < 0.001).

The mean body size of central Anatolian pigs appears smaller than pigs from other regions. This difference is significant for pigs in the Hittite capital Boğazköy (Pylos: p = 0.024; Tiryns: p = 0.001; Troy: p < 0.001; Kaymakçı: p = 0.04; and, Lidar Höyük: p = 0.001), and pigs are also smaller in Gordion than at Tiryns (p = 0.025) and Troy (p > 0.001). This difference may partially be due to the occurrence of some very small specimens in Boğazköy and Gordion. Petite pigs also occurred in small numbers in Greek Magula Pevkakia and Eleon and western Anatolian Klazomenai and Kaymakçı, but they are more numerous in Gordion and Boğazköy. Von den Driesch and Vagedes (Citation1997, 131) noted that at Kuşaklı, pig bones were even smaller than at Boğazköy, but they did not provide measurements. Despite body size variation, molar size in Hittite pigs does not substantially vary from other sites, except between Gordion and Kaman Kalehöyük, where molars are smaller than at Kaymakçı (p = 0.020; p = 0.019).

Sample sizes from southern and southeastern Anatolian sites were generally small. Postcranial measurements for pigs in these regions show no significant differences to other Anatolian sites. Molar sizes vary, however. Pig teeth at Müslümantepe and Kavuşan Höyük are significantly smaller than most western and central Anatolian sites and sites in their proximity (e.g., to Lidar Höyük [p < 0.001; p < 0.000], Hirbemerdon Tepe [p = 0.013; p = 0.011]) and Turbe Höyük (to Müslümantepe, p = 0.027).

pearson’s coefficient of variation

Comparison of Pearson’s Coefficient of Variation (CV) for pig molars from selected LBA assemblages, archaeological reference data from Durrington Walls (UK), and reference data from modern wild boar from Kızılcahamam are displayed in . For these reference assemblages, as well as the LBA assemblages from Kastanas and Tiryns, CVs adhere to normal phenotypic variation expected within a taxonomic group. The LBA assemblages from Klazomenai and Lidar Höyük show slightly elevated values for the majority of the measurements, with CV increasing up to 7.5. Lower third molar measurements in Troy vary strongly too, but, based on the occurrence of wild boar-sized bones in the assemblage, it is possible that wild boar and domestic specimens mingled. The CV of 8–12 for pigs at Kaymakçı contrasts strongly with the reference and LBA pig assemblages, underlining that this is an unusual phenomenon that cannot be explained by sample size alone.

Discussion

Pigs at Kaymakçı

Across large LBA centers in the Aegean, Anatolia, and Mesopotamia, the role of pig husbandry varied and usually did not exceed the economic importance of sheep, goat, and cattle. The layout of Kaymakçı resembles these centers in several ways, most notably in its concentric fortifications. Even though Kaymakçı was intermediary to Hittite and Mycenaean politics and exchange, the animal economy in Kaymakçı differed. Although the economy contained elements of mixed sheep, goat, and cattle husbandry, it was largely dominated by pig husbandry.

Pigs at Kaymakçı must have been a frequent sight in both the built and the natural environment. The large number of young pigs in the assemblage may have been locally bred, procured off-site, or provisioned to the settlement. The large number of perinatal piglets suggests some (pregnant) pigs were kept within the confines of the settlement, possibly on a household level and/or roaming the streets, whereas the presence of adult male and female pigs of various ages suggests other pigs were loosely, probably extensively, managed. It is possible that one, or both, of these husbandry systems were related to autumn/winter activity, when dependency on protein from juvenile pigs of 8–12 months (born in spring) became more pressing, or preferred, in alternation with summer activity, when fat-rich protein could be procured from fish (Griffin Citation1998). When food is abundant, pigs can, however, farrow at a younger age and more than once a year (e.g., Massei et al. Citation1997; Albarella, Manconi, and Trentacoste Citation2011), which, in the case of free-ranging sounders (typically consisting of a few sows and their numerous offspring), may have overpopulated the valley and necessitated crowd-control of animals in these age groups.

These different husbandry strategies are reflected in the excessive variation in body and molar size, which indicates pigs in Kaymakçı were phenotypically pluriform. CV values indicate that molar dimensions are too diverse to occur within a single animal population, and the Gaussian mixture analysis identified more than one phenotypic group within Kaymakçı’s pigs. Whereas body size is known to vary considerably as a result of age, sexual dimorphism, nutrition, and husbandry conditions, molar size is typically determined by genetic disposition. The variation in molar size is therefore likely to reflect genetic variation, which can appear by combination and/or hybridization of more than one population through selective breeding, domestication, and/or feralization (e.g., Evin et al. Citation2015; Rowley-Conwy and Zeder Citation2014; Balasse et al. Citation2016; Price and Evin Citation2017).

Size is one of the first characteristics researchers look at to distinguish between wild boar and domestic pig populations in archaeological assemblages. Discerning the presence of wild boar in Kaymakçı is problematic, however, because wild boar size baselines for Mesolithic, Bronze Age, and modern western Anatolia still need to be developed, and the sizes of wild and domestic pigs can overlap (Payne and Bull Citation1988; Mayer, Novak, and Brisbin Jr Citation1998; Evin et al. Citation2013). Large dimensions reported from the northern Aegean, the early Neolithic in northwestern Anatolia, and modern wild boar in central Anatolia (Bökönyi Citation1986; Payne and Bull Citation1988; Boessneck and von den Driesch Citation1979) suggest that boar in this region can become substantially larger than Kaymakçı’s pigs. Therefore, we are currently left to assume that size variation at Kaymakçı occurs within domestic pigs and that our data thus reveals heterogenous, if not different, domestic populations.

The size variation in Kaymakçı’s assemblage may correspond to intensive and extensive pig husbandry practiced in parallel. Extensively managed pigs tend to become generally larger because they can express natural breeding and feeding behavior and interbreed with wild boar (e.g., Evin et al. Citation2015). The concept of different pig husbandry styles was not unknown in LBA Anatolia. Hittite texts describe pigs kept in enclosures, as well as courtyard pigs and pigs scavenging streets (Collins Citation2006; Klengel Citation2007). Different husbandry styles affected the economic value of these pigs. Grain-fed pigs were prized double that of courtyard pigs, while in Boğazköy-Hattusa, street-scavengers were considered impure (Hoffner Citation1974). As previous zooarchaeological studies have not yet filled out this picture from the texts, the zooarchaeological identification of multiple populations of pigs at Kaymakçı might be the first to reflect such a conceptual and practical division of domestic pig populations in Anatolia. The reason why this manifests so clearly at Kaymakçı is likely because of the large sample size and fine-grained analysis. Differential breeding and husbandry practices resulting in different animal varieties have, however, been reported outside Anatolia for sheep and cattle in LBA–EIA Italy (Gaastra Citation2014) and for pigs in ancient Egypt and Bronze Age Switzerland (Bertini and Cruz-Rivera Citation2014; Bopp-Ito et al. Citation2018).

Additionally, it is possible that the variation in Kaymakci’s pigs results from mixing with non-local pig populations. Western Anatolia is the most plausible entry point for pigs with European haplotypes which appear in Anatolia and the Levant from the Middle Bronze Age onwards (Ottoni et al. Citation2013). The phenotypic heterogeneity in Kaymakçı’s pigs might reflect such an introduction. The slightly elevated CV values in Klazomenai, known for its Mycenaean connections (Vaessen Citation2016), and Lidar Höyük, where the first pig specimen with a European haplotype was identified in Middle Bronze Age layers (Ottoni et al. Citation2013), could likewise reflect such introductions. Pigs from LBA western Anatolia have, however, not yet been analyzed in studies mapping ancient pig genetics (e.g., Frantz et al. Citation2019; Ottoni et al. Citation2013), leaving this option currently open.

Late Bronze Age pig husbandry in the Aegean and Anatolia

Pigs were an integral part of Mycenaean economies, an essential component of subsistence in the northern Aegean and western Anatolia, variably rare in the Hittite realm and southern Anatolia, and well-incorporated in southeastern Anatolian economies. These regional differences cannot be explained by environmental variation alone. Pig physiology can constrain husbandry in hot and arid conditions (Spinka Citation2009), but our study region is characterized by sufficient water availability, vegetation, and temperate climates. Coastal and mountainous microclimates in the Mycenaean heartland provided ample woodlands and water sources (Zerefos and Zerefos Citation1978). In the northern Aegean, alluvial and coastal plains created elaborate forest cover (Becker Citation1986; Becker and Kroll Citation2008). The mild sea climate in western Anatolia similarly created a suitable habitat, with interchanging park landscapes and oak canopy (Zeist and Bottema Citation1991). In central Anatolia, seasonal differences in temperature and humidity are stronger, but in the north, where the sites included in our study are located, vegetation cover is varied and precipitation higher (Zeist and Bottema Citation1991; von den Driesch and Vagedes Citation1997). The humid southern coast of Anatolia was covered with olive trees and evergreen oak. In Bronze Age southeastern Anatolia, deciduous woodlands and medium temperatures prevailed (Zeist and Bottema Citation1991). These conditions are all suitable habitats for wild and domestic pigs.

Without large-scale environmental constraints limiting pig husbandry potential in Greece and Anatolia, variations in the economic importance and role of pigs appear to result from economic choices and cultural preferences. In most Mycenaean sites, pig husbandry was local and aimed at pork from young piglets, probably year-round. The culling activity and petite size of pigs at Magula Pevkakia, Eleon, and Asine indicate intensive husbandry. At Magula Pevkakia and Nichoria, the lack of reproductive adults might represent provisioning, as indicated by Linear B texts (Rougemont Citation2006). Interestingly, provisioning of pigs to palatial centers is less evident at palatial centers themselves, such as Tiryns and Pylos. At Tiryns, many pigs were culled during their first year, yet the presence of both male and female adults is uncharacteristic of intensive pork production (von den Driesch and Boessneck Citation1990). At Pylos, Nobis (Citation1993) reported that the majority of domestic pigs were adults of various ages. In combination with the interest in Pylos for wild boar, the inhabitants apparently procured full-grown pigs through provisioning, extensive husbandry, and/or hunting. Both these palatial sites thus demonstrate demands for a mix of pig products.

In the northern Aegean, animal husbandry reflects the egalitarian, autonomous nature of this region suggested by Andreou (Citation2001, 160). Pigs were vital components of subsistence strategies. At Kastanas and Anchelochori (Becker Citation1986; Creuzieux et al. Citation2014), culling may have intensified over the autumn and winter, and extensive husbandry strategies enabled many pigs to survive into adulthood. In contrast, pigs were more closely controlled at Thessaloniki Toumba (Vasileiadou Citation2009). No mortality data was available for Olynth, but males and females in this assemblage were equally represented (Becker and Kroll Citation2008). Tooth sizes of pigs in Olynth conform to pigs on the Greek mainland, but the pigs in Olynth were bigger-bodied, suggesting that they were extensively managed as well.

Pig husbandry in western Anatolia strongly varied between Troy, Klazomenai, and Kaymakçı. Piglets were culled both very young or as full adults at Troy, and the large body size suggests pigs at Troy were likely free-ranging or feral. At Klazomenai, pigs are considerably smaller-bodied and -toothed. At Kaymakçı, we demonstrated above that the larger and smaller pigs are unlikely to manifest in a single population and that intensive and extensive husbandry may have co-existed. Culling patterns at Klazomenai and Kaymakçı strongly resemble each other, suggesting the practice of extensive husbandry at both sites.

The scarcity of pigs in Hittite settlements already observed by Dörfler and colleagues (Citation2011) is reflected in our data, as central Anatolian assemblages contain fewer pig bones than assemblages from outside the borders of the Hittite heartland. Within the Hittite realm, pig husbandry shows variation (Berthon Citation2017). For all sites except Boğazköy, mortality data indicate intensive pig husbandry, which suggests that pig husbandry was more common than is indicated by the relative abundance of pig bones alone. Pigs in Hittite assemblages are small, raising the question of whether size may relate to the conceptual division of Hittite pigs discussed above. At Boğazköy, this consideration might be relevant, as kill-off patterns show that the majority of pigs were full-grown (von den Driesch and Boessneck Citation1981). Might this anomalous pattern in Boğazköy be related to scavenging urban pigs that perished within the settlement, or is it perhaps evidence of intensively controlled, grain-fed pigs raised for lard? Available evidence cannot yet resolve such questions.

In southern Anatolia, pig bones are rare. For these sites, fine-grained data is not available. In Tell Atchana and Lidar Höyük, however, pigs were numerous and culled young. Across the eastern border of the Hittite Empire, pigs were also common. Berthon (Citation2014) suggests that high frequencies of pigs in the villages along the Tigris and Euphrates reflect differential access to regional economic animal products. Pigs are, however, equally common in the regional center of Ziyaret Tepe. Size variation in pig molars is quite large in this small region, but sample sizes are too small to detect clear patterns. Culling patterns were unanimously intensive at all sites, suggesting a structural inclusion of pork in the diet of both villages and cities.

Comparing these different regions shows three major patterns. Firstly, the number of pig bones across Greece and Anatolia are relatively high, except in Hittite central Anatolia, but even there, pigs were a common sight. Secondly, intensive culling appears common in the Mycenaean and Hittite realms and southeastern Anatolia, whereas extensive strategies appear to be the norm in northern Greece and western Anatolia. Thirdly, and somewhat at odds with reconstructed culling strategies, the high variation in pig size in Anatolia contrasts with the uniform size of Greek pigs. This might mirror a wider range of husbandry strategies in Anatolia. However, high variability in size might alternatively reflect the co-existence, possibly mixing, of different phenotypes that may or may not be husbanded in different ways, as a result of intensive interactions of LBA Anatolia, intra- and interregional.

Understanding LBA pig husbandry in the Aegean and Anatolia remains hampered by the varying quality of published faunal data. The differential chronological and contextual resolution with which they have been presented does not allow investigating patterns that may be caused by the functional and organizational differences between sites, especially after 1400 b.c. In the Mycenaean world, animal husbandry may have changed during the rise and demise of palatial economies (Shelton Citation2010), whereas in central Anatolia, the expansion of the Hittite Empire combined a multitude of different traditions with differing attitudes towards pigs (Collins Citation2006). Towards the final phase of the LBA, environmental changes and socio-political instability may have likewise affected agricultural stability on local and regional scales (e.g., Drake Citation2012).

Pig principles in LBA Greece and Anatolia

The “pig principles” posit that pigs were an unattractive resource in urban, centralized animal economies in Mesopotamia and suggest that pig rearing and consumption were largely bound to households and rural areas (Hesse and Wapnish Citation1998). Pig husbandry at Kaymakçı and comparative regional data suggest that the “pig principles” do not fit the context of early state societies in Greece and Anatolia.

Kaymakçı takes a unique position in this analysis, as a large citadel in western Anatolia, intermediary to the predominantly Hittite central Anatolia and Mycenaean Aegean. Pig husbandry here diverges from expectations of large centers for two reasons. First, unlike many other LBA sites, pigs formed a primary component of subsistence. Secondly, intensive pig husbandry, characteristic of LBA citadels in Greece and Anatolia, and extensive strategies, characteristic for western Anatolia and the northern Aegean, co-existed here. The practice of extensive husbandry does not necessarily imply that Kaymakçı had no central system(s) of animal husbandry, but that the “pig principles” do not sufficiently apply to Kaymakçı.

The “pig principles” do not fit the large centers of LBA Greece and Anatolia well either. Pig husbandry in Greece and Anatolia was not limited to rural households. Pig bones are abundant in nearly all assemblages from large centers, except at Hittite sites. Even for the Hittite realm, however, both historical texts and mortality data suggest that pigs were incorporated in centrally regulated, specialized production. Texts specify objectives for specialized pig husbandry, including meat and lard production, and the production of pigs designated for feasts, festivals, and rituals. It is very likely that these specialized productions co-existed with other systems, such as household pig keeping, but data from smaller centers are rare in Greece and Anatolia. These multiple systems demonstrate that LBA pig husbandry in Greece and Anatolia can best be understood as a story of multiple pig husbandries, shaped by the complex social, ritual, and economic demands of LBA societies.

Conclusion

In Kaymakçı, pigs were a common sight both within and outside the built environment. Culling patterns suggest both intensive and extensive pig husbandry were vital to the economy at this LBA center. These husbandry strategies and the heterogeneous size of pigs in Kaymakçı suggest pig husbandry and pigs themselves were pluriform. Further investigation is necessary to address whether this previously unattested phenomenon in LBA Anatolia reflects co-existing husbandry strategies, the region’s dynamic cultural interactions involving introductions of new animal varieties, or the high quality of our data.

Our bottom-up exploration of pig data across LBA Greece and Anatolia likewise reveals considerable variability in pig husbandry purposes and strategies within and across sub-regions. This variation in LBA pig husbandry in Greece and Anatolia is not entirely surprising in light of Mycenaean and Hittite texts that describe multiple social connotations and economic uses for pigs. The zooarchaeological identification of multiple pig husbandries and pig varieties in Kaymakçı, which probably reflects the co-existence of conceptual and practical meanings for pigs as seen in texts, might be a first. However, it may just as well only show that many features of past pig husbandry remain invisible when the utility of pigs is only measured by pig bone frequencies in archaeological assemblages and pig mentions in ancient texts.

The variation in pig husbandries revealed in this study complicates the application of the “pig principles” as an explanatory model for LBA Greece and Anatolia and shows that more nuanced approaches are necessary to understand pig husbandry in this region. Future pig studies will, in our opinion, benefit from combining traditional zooarchaeological methods on well-contextualized assemblages with developing techniques to trace palaeo-genomes, morphotypes, and diet studies to further explore the socio-economic, environmental, and cultural dynamics of LBA pig husbandry across the Aegean and Anatolia.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (46.7 KB)Acknowledgements

This study was made possible by the support of Koç University’s Research Center for Anatolian Civilizations, the Netherlands Institute in Turkey, and the Groningen Institute of Archaeology, and the financial support of the National Endowment for the Humanities (Award RZ5155613), National Science Foundation (Award BCS-1261363), Institute for Aegean Prehistory, Loeb Classical Library Foundation, Merops Foundation, Boston University Vecchiotti Archaeology Fund, Catharine van Tussenbroek/Anneke Clason Zooarchaeology Grant, and the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO), under Ph.D. Grant project no. PGW.18.039 “Pigs, people and politics in the Late Bronze Age-Early Iron Age Aegean: Archaeological pig data as a proxy for socioeconomic and political relations in ancient societies.” For permissions and general assistance, sincere thanks are made to the General Directorate of Cultural Heritage and Museums of Turkey’s Ministry of Culture and Tourism and its annual representatives, the director and staff of the Manisa Museum of Archaeology and Ethnography, and all participants of the Kaymakçı Archaeological Project who collectively make such work possible. We thank Allowen Evin for her recommendations for data analysis. For general support and guidance on the manuscript and assistance with initial zooarchaeological field recording in 2014–2018, respectively, we offer specific thanks to C. Luke and to zooarchaeology trainees D. de Groene, E. Gizem Ayten, A. DiBattista, C. Mikeska, J. Kooistra, and H. Lau. Finally, we thank M. Zeder and H.-P. Uerpmann for granting us the use of their data.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on Contributors

Francesca G. Slim (M.A. [Res] 2018, University of Groningen) is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Groningen. Her Ph.D. focuses on human-pig relationships in the Aegean and Anatolia during the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age. Her research interests include the sociality of human-animal interactions, animal health and pathologies, and the zooarchaeology of the Hellenistic, Bronze Age, and Iron Age Aegean and Mediterranean.

Canan Çakırlar (Ph.D. 2007, University of Tübingen) is a senior lecturer at the Department of Archaeology at the University of Groningen. She is also the director of the zooarchaeology lab and collections at the Groningen Institute of Archaeology and serves on the International Committee of the International Council of Archaeozoology and the Managing Committee of the Association of Environmental Archaeology. Her research interests include the Neolithic and the subsequent spread of animal husbandry across western Anatolia and into southeastern Europe, marine resource exploitation in the ancient Mediterranean, and forms of human-animal interactions in early state societies in southwestern Asia.

Christopher H. Roosevelt (Ph.D. 2003, Cornell University) is a Professor of Archaeology and History of Art and Director of the Research Center for Anatolian Civilizations at Koç University, Director of the Kaymakçı Archaeological Project, and Co-Director of Gygaia Projects. His research interests include archaeological and spatial technologies and the archaeology of Bronze and Iron Age Anatolia and the eastern Mediterranean.

ORCID

Francesca G. Slim http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9885-6744

Canan Çakırlar http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7994-0091

Christopher H. Roosevelt http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4302-4788

References

- Albarella, U. 2002. “Size Matters: How and Why Biometry is Still Important in Zooarchaeology.” In Bones and the Man. Studies in Honor of Don Brothwell, edited by K. Dobney and T. O’Connor, 51–62. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Albarella, U., K. Dobney, and P. Rowley-Conwy. 2009. “Size and Shape of the Eurasian Wild Boar (Sus scrofa), with a View to the Reconstruction of its Holocene History.” Environmental Archaeology 14 (2): 103–136.

- Albarella, U., F. Manconi, and A. Trentacoste. 2011. “A Week on the Plateau: pig Husbandry, Mobility and Resource Exploitation in Central Sardinia.” In Ethnozooarchaeology. The Present and Past of Human-Animal Relationships, edited by Umberto Albarella and Angela Trentacoste, 143–159. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Albarella, U., and S. Payne. 2005. “Neolithic Pigs from Durrington Walls, Wiltshire, England: A Biometrical Database.” Journal of Archaeological Science 32 (4): 589–599.

- Alparslan, M. 2013. “Bir Imparatorlugu Ayakta Tutabilmek Ekonomi ve Ticaret - Sustaining an Empire: Economy and Trade.” In Hititler: Bir Anadolu Imparatorlugu. Hittites: An Anatolian Empire, edited by M. Doğan-Alparslan, 506–517. Yapi Kredi Yayinlari.

- Andreou, S. 2001. “Exploring the Patterns of Power in Bronze Age Settlements of Northern Greece.” In Urbanism in the Aegean Bronze Age, Sheffield Studies in Aegean Archaeology, edited by K. Branigan, 160–173. Sheffield Academic Press.

- Arbuckle, B. 2009. “Chalcolithic Caprines, Dark Age Dairy, and Byzantine Beef: A First Look at Animal Exploitation at Middle and Late Holocene Çadır Höyük, North Central Turkey.” Anatolica XXXV: 179–224.

- Arbuckle, B. S., and E. L. Hammer. 2019. “The Rise of Pastoralism in the Ancient Near East.” Journal of Archaeological Research 27: 391. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10814-018-9124-8.

- Baker, P. 2008. “Economy, Environment and Society at Kilise Tepe, Southern Central Turkey–Faunal Remains from the 1994–1998 Excavations.” Publications de la Maison de l'Orient et de la Méditerranée 49 (1): 407–430.

- Balasse, M., T. Cucchi, A. Evin, A. Bălăşescu, D. Frémondeau, and M.-P. Horard-Herbin. 2018. “Wild Game or Farm Animal? Tracking Human-Pig Relationships in Ancient Times through Stable Isotope Analysis.” In Hybrid Communities. Biosocial Approaches to Domestication and Other Trans-Species Relationships, edited by C. Stéphanov and J. D. Vigne, 81–96. London: Routledge Studies in Anthropology.

- Balasse, M., A. Evin, C. Tornero, V. Radu, D. Fiorillo, D. Popovici, R. Andreescu, K. Dobney, T. Cucchi, A. Bălăşescu, et al. 2016. “Wild, Domestic and Feral? Investigating the Status of Suids in the Romanian Gumelniţa (5th mil. cal BC) with Biogeochemistry and Geometric Morphometrics.” Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 42: 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaa.2016.02.002.

- Becker, C. 1986. “Kastanas: Ausgrabungen in einem Siedlungshügel der Bronze-und Eisenzeit makedoniens 1975–1979. Die Tierknochenfunde.” PhD diss. Volker Spiess.

- Becker, C., and H. Kroll. 2008. Das Prähistorische Olynth, Band 22. Prähistorische Archäologie in Südosteuropa. Raden/Westfalen: Verlag Marie Leidorf GmbH.

- Berthon, R. 2014. “Small But Varied. The Role of Rural Settlements in the Diversification of Subsistence Practices as Evidenced in the Upper Tigris River Area (Southeastern Turkey) During the Second and First Millennia BCE.” Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies 2 (4): 317–329.

- Berthon, R. 2017. “Herding for the Kingdom, Herding for the Empire. The Contribution of Zooarchaeology to the Knowledge of Hittite Economy.” Byzas 23: 175–184.

- Bertini, L., and E. Cruz-Rivera. 2014. “The Size of Ancient Egyptian Pigs.” Bioarchaeology of the Near East 8: 83–107.

- Boessneck, J., and A. von den Driesch. 1975. “Tierknochenfunde vom Korucutepe bei Elazığ in Ostanatolieri.” In Korucutepe: Final Report on the Excavations of the Universities of Chicago, California (Los Angeles) and Amsterdam in the Keban Reservoir, Eastern Anatolia, 1968–1970, vol. 1, edited by M. N. van Loon, 1–220. Amsterdam/Oxford/New York.

- Boessneck, J., and A. von den Driesch. 1979. Die Tierknochenfunde aus der Neolithischen Siedlung auf dem Fikirtepe bei Kadiköy am Marmarameer. München: Universität München, Institut für Palaeoanatomie, Domestikationsforschung und Geschichte der Tiermedizin.

- Bopp-Ito, M., T. Cucchi, A. Evin, B. Stopp, and J. Schibler. 2018. “Phenotypic Diversity in Bronze Age Pigs from the Alpine and Central Plateau Regions of Switzerland.” Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 21: 38–46.

- Bökönyi, S. 1986. “The Faunal Remains.” In Excavations at Sitagroi 1, Vol. 1, edited by C. Renfrew, M. Gimbutas, and E. S. Elster, 63–96. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press.

- Bryce, T. R. 1989. “The Nature of Mycenaean Involvement in Western Anatolia.” Historia: Zeitschrift Für Alte Geschichte H1: 1–21.

- Bryce, T. R. 2012. “The Late Bronze Age in the West and the Aegean.” In The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia: (10,000–323 BCE), edited by G. McMahon and S. Steadman. Oxford University Press.

- Cannon, M. D. 2013. “NISP, Bone Fragmentation, and the Measurement of Taxonomic Abundance.” Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 20 (3): 397–419.

- Collins, B. J. 2006. “Pigs at the Gate: Hittite Pig Sacrifice in its Eastern Mediterranean Context.” Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions 6 (1): 155–188.

- Creuzieux, A., A. Gardeisen, E. Stefani, G. Touchais, R. Laffineur, and F. Rougemont. 2014. “L’Exploitation du Monde Animal en Grèce Septentrionale Durant le Bronze Récent: L’Exemple D’Angelochori.” In Physis. L’Environmet Naturel et la Relation Homme-Milieu Dans le Monde Égéen Protohistorique, 409–414. Leuven/Liege, Peeters.

- Çakırlar, C., L. Gourichon, S. Pilaar Birch, R. Berthon, M. Akar, and K. Aslıhan Yener. 2014. “Provisioning an Urban Center Under Foreign Occupation: Zooarchaeological Insights in the Hittite Presence in Late Fourteenth-Century BCE Alalakh.” Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies 2 (4): 259–276.

- Davis, S. J. M. 1987. The Archaeology of Animals. London: Routledge.

- Dedeoğlu, F., and E. Abay. 2014. “Beycesultan Höyük Excavation Project: New Archaeological Evidence from Late Bronze Age Layers.” Arkeoloji Dergisi 19: 1–39.

- DeFrance, S. D. 2009. “Zooarchaeology in Complex Societies: Political Economy, Status, and Ideology.” Journal of Archaeological Research 17 (2): 105–168.

- Deniz, E., T. Çalışlar, and T. Özgüden. 1964. “Osteological Investigations of the Animal Remains Recovered from the Excavations of Ancient Sardis.” Anatolia 8: 49–64.

- Dörfler, W., C. Herking, R. Neef, P. Pasternak, and A. von den Driesch. 2011. “Environment and Economy in Hittite Anatolia.” In Insights into Hittite History and Archaeology, Colloquia Antiqua 2, edited by H. Genz and D. P. Mielke, 99–124. Walpole: Peeters.

- Drake, B. L. 2012. “The Influence of Climatic Change on the Late Bronze Age Collapse and the Greek Dark Ages.” Journal of Archaeological Science 39: 1862–1870.

- Erkanal, H. 2008. “Geç Tunç Çağı’nda Liman Tepe.” In Batı Anadolu ve Doğu Akdeniz Geç Tunç Çağı Kültürleri Üzerine Yeni Araştırmalar, edited by A. Erkanal-Öktü, S. Günel, and U. Deniz, 91–100. Ankara: Hacettepe Üniversitesi Yayınları.

- Evin, A., T. Cucchi, A. Cardini, U. S. Vidarsdottir, G. Larson, and K. Dobney. 2013. “The Long and Winding Road: Identifying Pig Domestication through Molar Size and Shape.” Journal of Archaeological Science 40 (1): 735–743.

- Evin, A., K. Dobney, R. Schafberg, J. Owen, U. S. Vidarsdottir, G. Larson, and T. Cucchi. 2015. “Phenotype and Animal Domestication: A Study of Dental Variation between Domestic, Wild, Captive, Hybrid and Insular Sus scrofa.” BMC Evolutionary Biology 15: 6.

- Fairbairn, A., and S. Omura. 2005. “Archaeological Identification and Significance of ÉSAG (Agricultural Storage Pits) at Kaman-Kalehöyük, Central Anatolia.” Anatolian Studies 55: 15–23. doi:10.1017/S0066154600000636.

- Fillios, M. A. 2007. “Measuring Complexity in Early Bronze Age Greece: The Pig as a Proxy Indicator of Socio-Economic Structures.” PhD diss. John and Erica Hedges Ltd.

- Frantz, L. A. F., J. Haile, A. T. Lin, A. Scheu, C. Geörg, N. Benecke, M. Alexander, et al. 2019. “Ancient Pigs Reveal a Near-Complete Genomic Turnover Following their Introduction to Europe.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116 (35): 17231–17238. doi:10.1073/pnas.1901169116.

- Gaastra, J. S. 2014. “Shipping Sheep or Creating Cattle: Domestic Size Changes with Greek Colonisation in Magna Graecia.” Journal of Archaeological Science 52: 483–496.

- Gaastra, J. S., H. J. Greenfield, and T. Greenfield. In press. “Constraint, Complexity and Consumption: Zooarchaeological Meta-Analysis Shows Regional Patterns of Resilience across the Metal Ages in the Near East.” Quaternary International, Available online: 23 May 2019. DOI: 10.17632/ks2df7fw59.1.

- Gamble, C. S. 1978. “The Bronze Age Animal Economy from Akrotiri: A Preliminary Analysis.” In Thera and the Aegean World I, edited by C. Doumas, 745–753. London: Thera Foundation.

- Gamble, C. S. 1982. “Animal Husbandry, Population and Urbanisation.” In An Island Polity: The Archaeology of Exploitation on Melos, edited by C. Renfrew and J. Wagstaff, 161–71. Cambridge: Cambridge University.

- Gander, M. 2017. “The West: Philology.” In Handbook of Oriental Studies. Hittite Landscape and Geography, edited by M. Weeden and L. Z. Ullmann, 262–280. Leiden: Brill.

- Gardeisen, A. 2010. “Approche Comparative de Contextes du Bronze Moyen à Travers les Données de L’archéozoologie.” In Mesohelladika, la Grèce Continentale au Bronze Moyen, Mar 2006, Athènes, Grèce. Bulletin de Correspondence Hellénique Supplément52, edited by A. Philippa-Touchais, G. Touchais, S. Voutsaki, and J. Wright, 721–732. Athens: École Française d’Athènes.

- Grant, A. 1982. “The Use of Tooth Wear as a Guide to the Age of Domestic Animals.” In Ageing and Sexing Animal Bones from Archaeological Sites, edited by B. Wilson, C. Grigson, and S. Payne, 91–108.

- Greaves, A. M. 2012. “The Greeks in Western Anatolia.” In The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia: (10,000–323 BCE), edited by G. McMahon and S. Steadman. Oxford University Press.

- Griffin, P. B. 1998. “An Ethnographic View of the Pig in Selected Traditional Southeast Asian Societies.” In Ancestors for the Pigs. MASCA Research Papers in Science and Archaeology, edited by S. M. Nelson, 27–75. UPenn Museum of Archaeology.

- Grigson, C. 2007. “Culture, Ecology, and Pigs from the 5th to the 3rd Millennium BC Around the Fertile Crescent.” In Pigs and Humans: 10,000 Years of Interaction, edited by U. Albarella, K. Dobney, A. Ervynck, and P. Rowley-Conwy, 83–108. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Günel, S. 2010. “Mycenaean Cultural Impact on the Çine (Marsyas) Plain, Southwest Anatolia: the Evidence from Çine-Tepecik.” Anatolian Studies 60: 25–49.

- Habermehl, K. H. 1975. Altersbestimmung Haus- und Labortieren. Berlin: Verlag Paul Parey.

- Halstead, P. 1993. “The Mycenaean Palatial Economy: Making the Most of the Gaps in the Evidence.” Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 38: 57–86.

- Halstead, P. 1999. “Texts, Bones and Herders: Approaches to Animal Husbandry in Late Bronze Age Greece.” Minos 33–34: 149–189.

- Halstead, P. 2003. “Texts and Bones: Contrasting Linear B and Archaeozoological Evidence for Animal Exploitation in Mycenaean Southern Greece.” In Zooarchaoelogy in Greece: Recent Advances, Britisch School at Athens Studies, Vol.9, edited by E. Kotjabopoulou, Y. Hamilakis, P. Halstead, C. Gamble, and P. Elefanti, 257–261. London: British School at Athens.

- Halstead, P. 2011. “Redistribution in Aegean Palatial Societies. Terminology, Scale, and Significance.” American Journal of Archaeology 115 (2): 229–235.

- Halstead, P., and V. Isaakidou. 2017. “Sheep, Sacrifices, and Symbols: Animals in Later Bronze Age Greece.” In The Oxford Handbook of Zooarchaeology, edited by U. Albarella, M. Rizzetto, H. Russ, K. Vickers, and S. Viner-Daniels, 114–126. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hamilakis, Y., and E. Konsolaki. 2004. “Pigs for the Gods: Burnt Animal Sacrifices as Embodied Rituals at a Mycenaean Sanctuary.” Oxford Journal of Archaeology 23 (2): 135–151.

- Hamilton, J., R. E. M. Hedges, and M. Robinson. 2009. “Rooting for Pigfruit: Pig Feeding in Neolithic and Iron Age Britain Compared.” Antiquity 83 (322): 998–1011.

- Hanfmann, G. M. A., and C. Foss. 1983. “The City and Its Environment.” In Sardis from Prehistoric to Roman Times. Results of the Archaeological Exploration of Sardis, 1958–1975, edited by G. M. A. Hanfmann, 1–16. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Hauptmann, H. 1975. “Die Felsspalte D.” In Das Hethitische Felsheiligtum Yazılıkaya, edited by K. Bittel. Berlin: Gebrüder Mann Verlag.

- Hawkins, J. D. 1998. “Tarkasnawa, King of Mira: ‘Tarkondemos,’ Boğazköy Sealings and Karabel.” Anatolian Studies 48: 1–31.

- Hesse, B., and P. Wapnish. 1998. “Pig Use and Abuse in the Ancient Levant: Ethnoreligious Boundary- Building with Swine.” In Ancestors for the Pigs: Pigs in Prehistory, MASCA Research Papers in Science and Archaeology 15, edited by S. Nelson, 123–135. Philadelphia: Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Pennsylvania.

- Hoffner, H. A. 1974. “Alimenta Hethaeorum, Food Production in Hittite Asia Minor.” In Am Orient Ser 55. New Haven: American Oriental Society.

- Hongo, H. 1996. “Patterns of Animal Husbandry in Central Anatolia from the Second Millennium BC through the Middle Ages: Faunal Remains from Kaman-Kalehoyuk, Turkey.” PhD diss. Harvard University.

- Ikram, S., C. Çakırlar, and R. Kabatiar. Forthcoming. “The Fauna of Kinet Höyük.” JEMAHS.

- Isaakidou, V., P. Halstead, J. Davis, and S. Stocker. 2002. “Burnt Animal Sacrifice at the Mycenaean ‘Palace of Nestor’, Pylos.” Antiquity 76 (291): 86–92.

- Kaniewski, D., E. Van Campo, J. Guiot, S. Le Burel, and T. Otto. 2013. “Environmental Roots of the Late Bronze Age Crisis.” PLoS ONE 8 (8): e71004.

- Klengel, H. 2007. “Studien zur Hethitischen Wirtschaft, 3: Tierwirtschaft und Jagd.” Altorientalische Forschungen 34 (1–2): 154–173.

- Knapp, A. B., and S. W. Manning. 2016. “Crisis in Context: The End of the Late Bronze Age in the Eastern Mediterranean.” American Journal of Archaeology 120 (1): 99–149.

- Kussinger, S. 1988. “Tierknochenfunde vom Lidar Höyük (Südostanatolien).” Unpublished PhD diss. University of Munich.

- Lemoine, X., M. A. Zeder, K. J. Bishop, and S. Rufolo. 2014. “A New System for Computing Dentition-Based Age Profiles in Sus Scrofa.” Journal of Archaeological Science 47: 179–193.

- Luke, C., and C. H. Roosevelt. 2016. “Memory and Meaning in Bin Tepe, the Lydian Cemetery of a ‘Thousand Mounds.” In Tumulus as Sema: Proceedings of an International Conference on Space, Politics, Culture, and Religion in the First Millennium BC, edited by O. Henry and U. Kelp, 407–28. TOPOI Excellence Cluster Series 27. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Luke, C., and C. H. Roosevelt. 2017. “Cup-marks and Citadels: Evidence for Libation in 2nd-Millenium BCE Western Anatolia.” BASOR 378: 1–23.

- Luke, C., C. H. Roosevelt, P. J. Cobb, and W. Çilingiroğlu. 2015. “Composing Communities: Chalcolithic through Iron Age Survey Ceramics in the Marmara Lake Basin, Western Turkey.” Journal of Field Archaeology 40 (4): 428–449.

- Mac Sweeney, N. 2010. “Hittites and Arzawans: A View from Western Anatolia.” Anatolian Studies 60: 7–24.

- Macheridis, S. 2018. “Waste Management, Animals and Society. A Social Zooarchaeological Study of Bronze Age Asine.” PhD diss. Lund University.

- Mangaloğlu-Votruba, S. 2015. “Liman Tepe During the Late Bronze Age.” In NOSTOI: Indigenous Culture, Migration and Integration in the Aegean Islands and Western Anatolia During the Late Bronze and Early Iron Age, edited by N. C. Stampolidis, Ç Maner, and K. Kopanias, 647–68. Istanbul: Koç University Press.

- Massei, G., P. V. Genov, B. W. Staines, and M. L. Gorman. 1997. “Factors Influencing Home Range and Activity of Wild Boar (Sus scrofa) in a Mediterranean Coastal Area.” Journal of Zoology 242: 411–423.

- Mayer, J. J., M. Novak, and I. L. Brisbin Jr. 1998. “Evaluation of Molar Size as a Basis for Distinguishing Wild Boar from Domestic Swine: Employing the Present to Decipher the Past.” In Ancestors for the Pigs. MASCA Research Papers in Science and Archaeology, edited by S. M. Nelson, 39–53. UPenn Museum of Archaeology.

- Meadow, R. H. 1999. “The Use of Size Index Scaling Techniques for Research on Archaeozoological Collections from the Middle East.” In Historia Animalium ex Ossibus: Beiträge auf Paläoanatomie, Archäologie, Ägyptologie, Ethnologie und Geschichte der Tiermedizin, edited by C. Becker, H. Manhart, J. Peters, and J. Schibler, 285–300. Rahden/Westf: Verlag Marie Leidorf.

- Meriç, R., and A. K. Öz. 2015. “Bademgediği Tepe (Puranda) Near Metropolis.” In NOSTOI: Indigenous Culture, Migration and Integration in the Aegean Islands and Western Anatolia During the Late Bronze and Early Iron Age, edited by N. C. Stampolidis, Ç Maner, and K. Kopanias, 609–26. Istanbul: Koç University Press.