ABSTRACT

This contribution synthesizes the results of the Kutaisi Archaeological Landscape Project (KALP), focusing on the analysis of the development of settlement patterns in the Colchis lowlands during the 2nd and 1st millennia b.c. The targeted excavations carried out within the urban center of Kutaisi provide new information regarding earthen architectural practices, raw material procurement, and defensive structures that characterized the area in the Late Bronze and Early Iron Ages. The three sites identified within the Kutaisi urban area, Gabashvili, Dateshidze, and Bagrati, are analyzed in detail to provide fresh insights on settlement structure and typology. They also present distinctive vernacular architectural traditions that make the role of Kutaisi in the region essential to understanding Late Bronze/Early Iron Age building practices, their continuity over time, and their environmental sustainability.

Introduction

The Kutaisi Archaeological Landscape Project (KALP), directed by Jacek Hamburg and Roland Isakadze (National Agency for Cultural Heritage Preservation of Georgia), is a long-term historical landscape development project investigating the socio-economic and political nature of the Kutaisi polity from the Bronze Age to the Middle Ages. In the first four years of the project (2017–2020), KALP focused on investigating the communities who lived in the region during the Late Bronze and Early Iron Ages through a combination of surveys in and around Kutaisi and targeted excavations at three sites: Gabashvili, Dateshidze, and Bagrati. These have been identified as settlements with a long continuity of occupation within the borders of the Kutaisi urban zone. The Dateshidze and Gabashvili hills dated from the Late Bronze Age to the Classical period (14th/13th–1st centuries b.c.), while the Bagrati citadel presents archaeological remains dating from the transition between the Middle and Late Bronze Ages to the 19th century a.d. Previous archaeological research conducted by the Archaeological Research Centre of the Georgian Academy of Science (1984–1990) under the direction of O. Lanchava identified the sites of Gabashvili and Dateshidze as Early Iron Age and focused its efforts on the Pre-Classical (9th/8th–5th century b.c.) and Classical (below, at the southern foot of the Gabashvili hill; 4th–1st century b.c.) levels of Kutaisi (for a complete history of the excavation, see Hamburg and Isakadze Citation2018, 137–143; Lordkipanidze, Lanchava, and Lordkipanidze Citation1994, 27–34). The KALP excavations in these three areas provided evidence of diachronic Bronze Age occupation and distinctive findings related to vernacular architectural traditions (see Hamburg and Isakadze Citation2018; Hamburg et al. Citation2019). This contribution analyses the preliminary architectural data within the broad context of Late Bronze/Early Iron Age (LBA/EIA) settlement typologies in western Georgia in order to shed light on the relationship between the communities, architecture, and the natural environment. Our main research goal, focusing on determining the political organization and socio-cultural nature of the Bronze Age community living in Kutaisi, was two-fold: first, we investigated the difference between external and indigenous views of the Colchis inhabitants during the Late Bronze and Early Iron Ages through both historical sources and archaeological data. Second, we analyzed the archaeological evidence to define the settlement typology and architectural characteristics based on previously published data and the new discoveries made by KALP. Therefore, we employed two different perspectives: a regional scale to understand the settlement typologies and compare Kutaisi with the other Late Bronze/Early Iron Age settlements in the region and an intracity scale to investigate the Kutaisi case study as a diachronic settlement environment.

Research Background

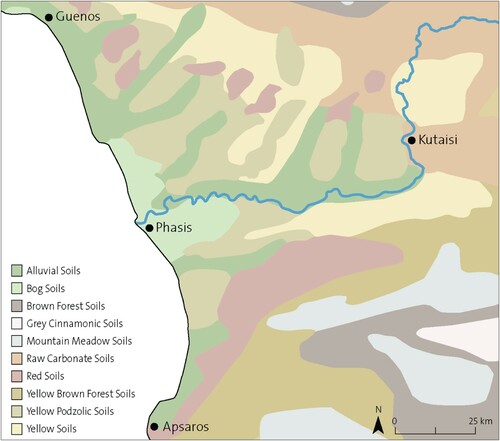

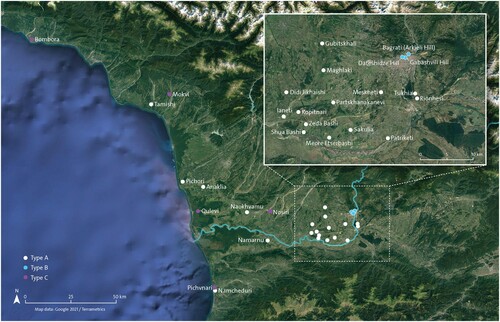

Colchis is the ancient name of the region now known as western Georgia, which includes the valley of the river Rioni (ancient Phasis), the eastern shore of the Black Sea, the Imereti region, and the Abkhazia region, extending to the southwest to the estuary of the river Chorokhi. Melikishvili (Citation1959, 62) was one of the first modern scholars to propose a comprehensive identification of this broad area, going well beyond the valley of the Rioni to incorporate the southwestern region of the Great Caucasus Range, the area west of the Adjaran, and the Lesser Caucasus mountains. The Greek name Colchis (Κολχίς) was first used to describe this geographic area in the works of Aeschylus and Pindar (Aeschylus Προμηθϵὺς Δϵσμώτης 415; Pindar Pythian 4). Greek writers described Colchis (Κολχίδα) in rich detail, including its mythical king Aeetes (Αἰήτης) and the royal city of Aya (Αἶα) (Herodotus Historiae 1.2.2; Apollonius Rhodius Argonautica 2.417), but did not make any references to a Colchian nation or large political units. In Greek mythology, Colchis was associated with the Golden Fleece and was known as the home of Medea, as a land of fabulous wealth and magic, and as the destination of the famous expedition of the Argonauts, but no additional information was given to the readers regarding its social organization. Historically, the legendary fame of Colchis primarily stemmed from its wealth of raw resources and its role as an important transit area for trade networks; thus, in the 7th century b.c., Greeks from Miletus first colonized the eastern shores of the Black Sea to extend their trade network of agricultural products and shipbuilding materials such as timber, flax, pitch, and wax (Strabo Geographica 11.2.17; Gamkrelidze Citation2012, 43; Tsetskhladze Citation1999, 101–107; Citation2016, 78; Citation2019, 24–28, table 5). After the 6th century b.c., Colchis fell under the nominal authority of the Persian Achaemenid Empire, and then, during the 1st century b.c., into the hands of Mithradates VI Eupator, King of Pontus, finally becoming a Roman province in the 1st century a.d. (for the periodization and history of Colchis, see Braund Citation1994, 122–151, 171–204; for the wider Caucasus perspective, see Hammer Citation2014) ().

Figure 1. Map of Colchis with the yellow lines indicating the extent of Colchian culture (Drawing by M. Holappa; data source: Google Earth and Terrametrics 2021).

This article demonstrates the effectiveness of an interdisciplinary approach to the study of settlement typology and architecture; originally based on environmental behavioral studies (EBS) methods, our approach combines building archaeology, historical research, and environmental studies (Rapoport Citation1969, Citation2006). This theoretical framework has adapted some key concepts from human behavioral ecology, such as variation of raw material sources and intensification, and from behavioral archaeology, such as flow models and behavioral chains, by combining data from environmental and social analysis (Bird and O’Connell Citation2006; Borgerhoff Mulder Citation2013; Kennett and Winterhalder Citation2006; Schiffer Citation1999, Citation2004, Citation2016). Therefore, this contribution investigates cultural and environmental factors that affected human behaviors and choices at the site of Kutaisi but with a narrow focus on architecture and the built environment. The building archaeology focused on the analysis of the Bronze and Iron Age architectural materials found in the excavations of Gabashvili, Dateshidze, and Bagrati, the three archaeological sites at the heart of Kutaisi. The historical research highlighted the external perception of contemporary travellers towards the Colchis people and their traditional vernacular culture, while the environmental studies provided the foundations to understand the human exploitation of the natural landscape during the creation of specific settlements.

The application of EBS theory in the analysis of LBA/EIA architecture of communities in the Colchis lowlands highlights how people in various settlements adapted the available natural resources in a socially meaningful way to create original and often heterogeneous domestic spaces. Rapoport (Citation1987) argued that environment, design, and culture are not separate and distinct concepts but rather are three factors that enable the interpretation of architecture as part of material culture. Domestic and public spaces then become the conduit to investigate people’s relationship with natural resources and the built environment. Thus, identifying the source and use of raw materials is one of the essential elements of understanding the Late Bronze and Early Iron Age community’s transformation of the built environment based on their cultural norms. Once available sources are defined, the differences or similarities in architectural forms and construction can help us infer the cultural aspects (Blanton Citation1994; Rapoport Citation1969). For instance, in the Colchis lowlands, within the often-generalized category of “earthen materials,” there was actually a variety of different techniques—such as wattle and daub, tauf, and brick architecture—which indicates the presence of multiple communities of practice and distinctive local architectural traditions.

Who were the Ancient People of Colchis? An Integrated Perspective from Historical Sources

The use of the term “Colchian culture” among scholars raises pertinent questions: who were the Colchians? Were they a tribe? Or a group of tribes? Were they people who created some kind of polity or organized community in the Bronze and Early Iron Age? While early studies defined Colchis as the first Caucasian polity to achieve unification (Lordkipanidze Citation1989; Toumanoff Citation1967, 69, 84), a more grounded approach to the archaeological evidence presents quite a different scenario. David Braund (Citation1994) discussed how the term “Colchians” is used as the collective noun for the early proto-Kartvelian tribes that populated the eastern coast of the Black Sea during the Classical period. Archaeological data support his interpretation and indicate the presence of a generally consistent material culture dating back to the Early Bronze Age (Proto-Colchian period), as reflected in architecture, metallurgy, and pottery (i.e., shapes and decorations), and persisting until the Greek colonization/Classical period (G. Kvirkvelia, personal communication 2020; Apakidze Citation2008, 331–332). On the other hand, an in-depth analysis of the material culture of western Georgia provides us with clear evidence of a degree of local autonomous development and regionalization within the Colchian culture, well exemplified, for instance, by Colchian asymmetrical axes and vessel decorations (Apakidze Citation2008, 331–339; Lordkipanidze and Mikeladze Citation1981, 294, 299). In the border regions of Abkhazia and Svanetia, the deep influence of northern Caucasian cultures is visible in the manufacture of axes that display elements typical of the steppe regions (Baramidze Citation1977; Gobejishvili Citation2014; Shnirelman Citation2001, 132, 201–225). Similarly, continuous contacts between the Colchian and northern Caucasian Koban cultures led to the creation of a striking bronze-casting technique in the Colchian-Koban joint style and a similar technique in metal engraving stressing the highland-lowland interaction (Erb-Satullo, Gilmour, and Khakhutaishvili Citation2017; Ho and Erb-Satullo Citation2021; Kohl and Trifonov Citation2014, 1591).

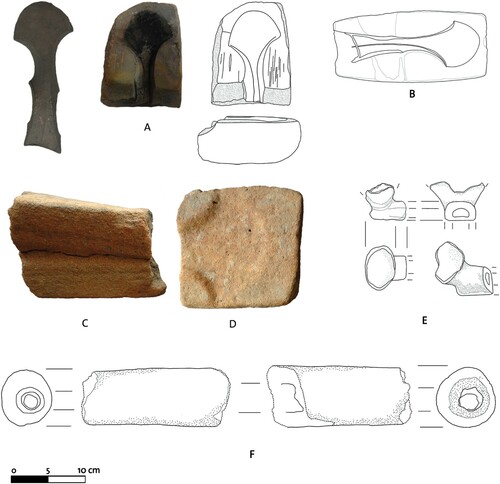

Research suggests a multi-scalar perspective on Colchian materials, indicating the presence of local, regionalized original production traditions existing within a generally similar overall environment that allowed scholars to create the over-arching label “Colchian”, a conceptual simplification that suggests a continuous material culture with strong regional characteristics that do not define ethnicity. The archaeological evidence from metalwork and ceramics provides us with enough examples of regionalization to allow us to re-address the narratives of the Georgian Late Bronze/Early Iron Age (Apakidze Citation2008, 331–339; Ho and Erb-Satullo Citation2021; Kohl and Trifonov Citation2014, 1591; Lordkipanidze and Mikeladze Citation1981, 294, 299) (). On the other hand, one line of evidence that has been little explored in this regard is settlement typology and architecture, and this study will hopefully represent the initial steps towards including these aspects in the discussion of Colchian culture. It is essential to stress that this label has no ethnic connotation, but is rather a geographical reference, and in this article is employed to describe the material culture of the people living in the Colchis lowlands in the Late Bronze and Early Iron Age period. This clarification is relevant due to the scarcity of indigenous epigraphic evidence that can provide any emic perspective on the ethnic definition of the Bronze and Iron Age communities living in Colchis (Harris Citation1976; Laguens Citation1988).

Figure 2. Casting moulds found in Kutaisi. A) Casting mould found in trench 7 (the moat), level 18, and an example of an axe (inv. no. A-54/10) found in 1939 in Dimi village (Georgia) of a similar form which can be obtained by this type of casting mould; B) casting mould found in trench 10 (the moat), level 9; C) casting mould discovered as an accidental find in 2016 on the Dateshidze Hill, located not far to the southwest of trench 9 and used to cast a spearhead; D) casting mould found by the Georgian Expedition in 1985 near the location of trenches 7 and 10 on Dateshidze Hill; E) broken crucible found in trench 10; and, F) fragment of a tuyere found in trench 7. (Photo credit: R. Bieńkowski, Sh. Buadze, processing by J. Hamburg, M.Holappa, drawing by K. Pawłowska).

Historical sources for the Early Iron Age and later periods are thus mainly provided by foreigners—Urartians, Assyrians, Greeks, and Romans—providing us with an external perspective on the Colchian people, who are described as a cultural mosaic. Among later Classical writers, Strabo (64 or 63 b.c.–ca. a.d. 24) wrote about the city of Phasis, located near the river of the same name, describing it as the market harbor of the Colchian people due to its strategic position between the river, the lake, and the sea (Strabo Geographica 11.2.17). A second important city with Greek ancestry was Dioskurias, also mentioned by Strabo, who noted that representatives of numerous tribes went to the city to buy salt in the summer (Strabo Geographica 11.5.6). Representatives of over 70 local (Colchian) tribes came to trade in the main city market. Likewise, Pliny the Elder wrote that Dioskurias was a Colchian city inhabited by almost 300 tribes, speaking so many different languages that business was conducted with the help of 130 translators (Pliny Historiae Naturalis 6.5.15). Xenophon, who personally knew the Caucasus and the local tribes, distinguished many different peoples living in a quite narrow region between the Black Sea and the Caucasus Mountains. Among the tribes he reported were the Taochi, Chalybians, Phasians, Macronians, and Colchians (Xenophon Anabasis 4.6.5– 4.8.25). Some classical texts mention a political organization of Colchis with a division into skeptuchoi (local elite authorities), and the tribes had their own rulers, such as Arrian of Nicomedia, but this applies to a later phase of Colchis’ history (Arrian of Nicomedia Periplus Ponti Euxini 15). However, this political organization referred to a late period and cannot be projected back into the LBA/EIA. Evidence for any kind of centralized authority in these earlier periods is lacking.

Early information from Urartian and Assyrian sources offers a contemporary external perspective of Colchis. Urartian sources indicate the use of the name Qulkha (Qulḫa) to identify the region of Colchis (Bremmer Citation2007, 9–38; Dyakonov and Kashkay Citation1981, 68–69; Lordkipanidze Citation1991, 110; Sagona Citation2018, 450; Salvini Citation1995, 70). A minority of interpretations place Qulkha in the Kars province of modern Turkey (Köroǧlu Citation2001, 717–741; Citation2005, 99–106). More relevantly, the word “Qulkha” is preceded in the text by the determinative KUR, meaning “land” (as opposed to the determinative URU, which means “city”), or by the masculine personal determinative m, which was used for the name of an ethnic group in Urartian writing (Haratyunyan Citation2001, 407–411). Salvini (Citation2002, 45) points out that an equivalency between the determinatives KUR and m can also be found in the spelling of other so-called “Transcaucasian states.” The first mention of the land of Qulkha is during the campaigns of the Urartian king Sarduri II (764–735 b.c.; see Salvini Citation2008, see CTU 1 A 08-03, translation: http://oracc.org/ecut/Q007048/).

While the closest Urartian neighbor to the north was Diauekhi (Diaueḫi), likely a federation of proto-Kartvelian tribes, from these textual sources, it seems that Qulkha was located quite far north from the Urartian core, among other foreign tribes (Burney and Lang Citation1975, 274; Haratyunyan Citation1998, 233–246; Koberidze Citation1929; Suny Citation1994, 6; Vakhnadze, Guruli, and Bakhtadze Citation1993, 172). The Diauekhi are also identified by Shalmaneser III (as Dayaeni/Dayani) as being located near the Urartian land (RIMA 3: A.0.102.8; A.0.102.12; A.0.102.23; A.0.102.28; A.0.102.29; A.0.102.30; A.0.102.31; A.0.102.32; A.0.102.33).1 The possible identification of the Diauekhi as the Taochi people would also position them as one of the tribes that inhabited the southern fringes of Colchis (Kavtaradze Citation2002, 80; Russell Citation1984). Evidence suggests that the Diauekhi federation occupied vast lands in the Artvin and Ardahan provinces of Turkey, including the basin and the estuary of the river Chorokhi, eastwards towards the Çıldır Lake, and southward including the Pasinler Plain (see Burney and Lang Citation1971, 136; Dinçol and Dinçol Citation1992, 112; Haratyunyan Citation2001, 523; Melikishvili Citation1959, 176–177; Russell Citation1984, 171–201; Sagona and Sagona Citation2004, 29; Salvini Citation2002, 38). These descriptions support the hypothesis that the Diauekhi were not just a single tribe but likely a federation of tribes united against the strong expansion of the Urartian and Assyrian kingdoms. The earliest hint of the complexity of the social makeup of Colchis comes from the Assyrian king Tukulti-Ninurta I (1243–1207 b.c.), who records “40 kings of the Upper Sea,” which is the Assyrian way of referring to the Black Sea (scil., the “Upper Sea” in Assyrian texts may refer to Lake Van or the Black Sea or the Mediterranean Sea. There are a few cases where the Caspian Sea is also referred to by the same term. It was assumed that all three seas are connected; RIMA 1: A.0.78.4; A.0.78.5; A.0.78.6; A.0.78.18; A.0.78.20; A.0.78.23; A.0.78.24; A.0.78.26).2 The royal annals of the Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser I (1114–1076 b.c.) described a campaign in which the king faced two federations of tribes in the north. According to the text, the Assyrian army crossed multiple lands with obvious Hurrian-Urartian toponyms and took a bridge across the Euphrates. Here, they faced a coalition of 22,000 soldiers led by the “kings of 23 lands,” which included the Diauekhi (RIMA 2: A.0.87.1, translation http://oracc.org/riao/Q005926/).3

When Tiglath-Pileser I defeated this coalition, he faced a second federation of enemies, including lands that extended even further north towards Colchis. This time, the federation was headed by “60 kings of Nairi,” not counting those who came to their aid. However, they also retreated before the Assyrian army. Tiglath-Pileser I reported that “I drove them away with my arrow to the Upper Sea” (i-na zi-qít mul-mul-li-ia a-di A.AB.BA; RIMA 2, A.0.87.1).4 The retreat of the kings of Nairi seemed to occur along the estuary of the Chorokhi River, already in the area of Colchis (Dyakonov Citation1968, 124).

These early records, as well as the accounts from classical authors, indicate that the Colchis region was a heterogeneous political reality fragmented among multiple tribes, a view that seems to find confirmation in the archaeological data so far discovered. Even in Roman times, the history of Colchis was marked by political and tribal fragmentation (see Arrian of Nicomedia Periplus Ponti Euxini 15; Diodorus Siculus Bibliotheca Historica 14.30.3; Lordkipanidze and Mikeladze Citation1988, 116; Tsetskhladze Citation1999, 103–117). We argue that, based on ancient sources combined with archaeological evidence that suggests the general similarity of Colchian material culture, the political organization of Late Bronze and Early Iron Age communities living within Colchis was also seemingly tribal during this period, lacking the cohesion of a single unified polity. This would explain the high degree of regionalization referenced in the texts, but it seems that the different tribes shared an overall ideology and/or social identity that would still justify the classification of their different regional productions as that of a single over-arching Colchian culture.

Environmental Perspective: The Natural Landscape of the Colchis Lowlands

Hippocrates (470–360 b.c.) gave the first documented account of the natural environment of the Colchis Plain in his work Πϵρί ἀέρων, ὑδάτων, τόπων (tr. On Airs, Waters, and Places). He described marshy and swampy lands with numerous canals and ditches, presenting these anthropic works as integral parts of the Colchian landscape. Hippocrates also portrayed the domestic architecture as being closely connected with the natural environment. Although his description is too general to offer any indication of the specific materials used, the archaeological record indicates the use of distinctive construction techniques in earthen and wooden architecture (i.e., type of soil, quality of reed, use of plaster in the interior, and typology of roofing) and house forms (i.e., circular vs. rectangular and agglutinative vs. nucleic) that also indicate a regionalization in architectural traditions. The environmental conditions of a region are one of the central factors that affect the availability of raw material sources for architecture and also have a possible impact on the development of building forms (Rapoport Citation1969, Citation1990). Therefore, understanding the Colchis environment in the Late Bronze and Early Iron Age is of the utmost importance in ascertaining the role that the environment played alongside culture in the creation of settlement typology and house forms.

The Colchis lowlands, with Kutaisi at its center, is situated in a humid subtropical climate zone that includes a coastal wetland facing the Black Sea, numerous valleys created by the rich hydrography, and an elevated fertile hinterland and is characterized by hot humid summers and cold winters (Bondyrev, Davitashvili, and Singh Citation2015; Braund Citation2012). A series of anthropogenic changes that took place over the last century have deeply affected the natural landscape of the Colchis valleys, specifically around the Rioni River, through the creation of a series of irrigation and drainage canals meant to improve agricultural conditions and a program of progressive deforestation likewise meant to provide more extensive farmlands (Bondyrev, Davitashvili, and Singh Citation2015, 100, 122, 210).

The geological landscape around the Colchis plain is characterized by a variety of soils of Cretaceous and Quaternary origins, having acquired its current form during the last Glacial maximum (Laermanns et al. Citation2018, 454–455). Among the geological sediments in the Colchis lowlands, red and yellow soils are prevalent and divided into the bog marshy soils, mountain meadow grey cinnamomic soils, and alluvial soils, both saturated and carbonates (Bondyrev, Davitashvili, and Singh Citation2015, 216–218; Machavariani Citation2008; Sagona Citation2018, 43; Urushadze, Tarasashvili, and Urushadze Citation2000). The natural geography of the area during the Bronze and Early Iron Age included fertile alluvial plains with soft foothills and highlands, naturally covered with a forest of oak, elm, basswoods, beech, lapin, pines, chestnut, and coniferous species (Bondyrev, Davitashvili, and Singh Citation2015, 122; Connor Citation2011; Connor, Thomas, and Kvavadze Citation2007). The presence of extensive wetlands in the mid-Holocene and the gradual transformation from open lagoons to alluvial plains between the 4th and mid-2nd millennia b.c. created favorable conditions for the human occupation of the Colchian plains during the mid-2nd millennium b.c. (Laermanns Citation2018, 88) ().

Figure 3. Geological map of the Colchis Valley (Drawing by M. Holappa after Urushadze Citation1999).

On the hydrological level, the Rioni River was the main navigable river of Colchis (Gamkrelidze Citation2012, 42). The mass artificial deforestation of the 19th and early 20th centuries a.d. has significantly lowered the base level of the Rioni, which has in turn negatively impacted navigation in the region. During the Late Bronze/Early Iron Age, the Colchis lowlands enjoyed very similar climatic characteristics, but due to the lack of extensive anthropogenic interventions, the natural extent of the marshy areas around the Rioni was more extensive. These marshy areas provided reed and soil for construction, and the availability of abundant forests around the highlands provided wood, while easily accessible quarries of limestone around Kutaisi and the riverbed supplied stone (Gamkrelidze Citation2012, 216). The mild climate of the Bronze Age may also have had a role in increasing sedentary occupation in western Georgia (Laermanns et al. Citation2018; Lordkipanidze Citation1991).

Chronology and the Complexity of Dating the 1st Millennium b.c. in the Colchis Lowlands

The Bronze and Early Iron Age chronology of western Georgia was originally established by B. A. Kuftin, who conducted rigorous stratigraphic excavations at multi-occupational sites (Kuftin Citation1950, 193–238). Based on the comparative results from the first excavated settlements—Naokhvamu I and II, Pichori, and Tamishi—this system currently provides the base timeline for dating the archaeological remains from all Colchian settlements, separating Colchian culture into two basic periods: Proto-Colchian and Ancient Colchian. Pichori, which is situated on the Black Sea near the estuary of the Inguri River, presents an undisturbed stratigraphic sequence that indicates the existence of a continuous culture extending from the first half of the 3rd millennium b.c. to the time of Greek colonization (Baramidze Citation1998, Citation1999; Smith Citation2005). Some of the key archaeological finds identified at Pichori—such as wooden and wattle and daub architecture, black polished pottery, and advanced metallurgical techniques—are easily comparable with the finds from numerous Late Bronze and Early Iron Age Colchian sites (Sagona Citation2018, 450). The terminology highlights a cultural continuation between these two periods and indicates the presence of a long cultural tradition starting in the Early Bronze Age (since ca. 2700 b.c.). A revised chronology based on the development phases of bronze/iron metallurgy and pottery sequences further subdivided these two periods (including up to ten different phases) () (see Apakidze Citation2008, 326–331; Baramidze Citation1998, 17–30, 59–66; Gogadze Citation1984, 28–54; Jibladze Citation1997; Citation2002, 17–21; Mikeladze Citation1974, 49–57; Citation1990, 19–22, 36–39, table 37). According to these latest studies, the basic chronology dates the Proto-Colchian period to 2700–1700/1600 b.c., corresponding to the Early and Middle Bronze Age, and the Ancient Colchian period to 1700/1600–700/600 b.c., corresponding to the Late Bronze/Early Iron Age (Apakidze Citation2002, 15–16, 75–76; Citation2008, 329–330; Jibladze Citation2002, 17–21; Kohl and Trifonov Citation2014, 1591; Sagona Citation2018, 450). Some scholars also distinguish a final period of Colchian culture, called Early Classical Colchian, as the period of the first arrival of the Greeks on the Black Sea shores, when the Milesian colonies were first established (700/600–170/150 b.c.).

Table 1. Chronology of western Georgia. The problem of the transition between the Late Bronze and Early Iron Age in Caucasian chronology is discussed further in Hamburg and Pawłowska Citation2017, 601–602 and Apakidze Citation2008.

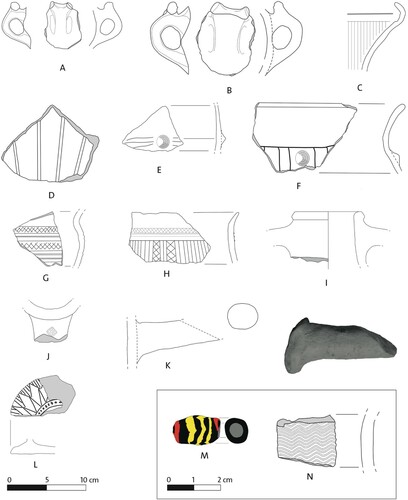

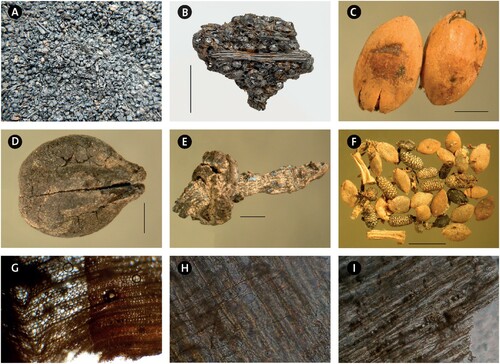

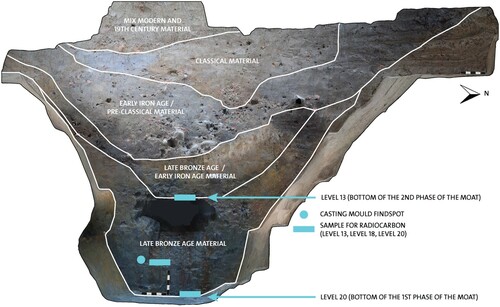

At Kutaisi, the analysis of the pottery from the trenches at the Gabashvili and Dateshidze hills pinpoints the initial occupation during the Ancient Colchian IIB period (900–710 b.c., according to Apakidze Citation2008, 330–335) as the main phase of moat use (Hamburg et al. Citation2019, 49–54) (). However, the first set of radiocarbon dates obtained from organic material found in the moat indicates more heterogeneous results, with an occupation of 1400–1000 b.c. (, ). Additional analyses are currently underway, but for the purposes of this article, we documented a continuous occupation during the Late Bronze/Early Iron Age (Ancient Colchian period), 1600–700/600 b.c., based on pottery analysis and current radiocarbon dating.

Figure 4. Kutaisi pottery and small finds: A–B) Dateshidze, trench 7, horn-like decoration; C–D) Dateshidze, trench 7, fluted decoration; E) Gabashvili, trench 2, fluted decoration with applied conical knob; F) Dateshidze, trench 7, applied decoration, conical knob; G–H) Dateshidze, Trench 7, incised cross-hatching decoration interlaced with burnished lines; I–J) Dateshidze, Trench 7, Colchian amphora with stamped handle; K) Dateshidze, trench 7, handle fragment of an imported amphora; L) Dateshidze, trench 7, lid fragment with incised decoration; M) Dateshidze, Trench 7, glass bead (330–70 b.c.); and, N) Dateshidze, trench 7, fragment of a conical mug (Drawing by K. Pawłowska; processing by A. Kaliszewska and M. Holappa; pottery analysis by A. Kaliszewska).

Figure 5. Organic materials. A–C) Millet (Panicum miliaceum): A) assemblage of charred remains, B) charred lump with millet, and C) waterlogged glumes. D–E) Grape (Vitis vinifera): D) seed (pipe) and E) stalk of fruit. F) Group of diasporas: common nettle (Urtica dioica) and St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum) included. G) Wood of Pinus sp., transversal section with a resin canal in the field of view—32x. H) Wood of Pinus sp., radial section with pinoid pits in the cross-field—160x. I) Wood of Pinus sp., tangential section with sectioned rays—63x. Scale bar = 1 mm. (Photo credit and paleobotanical analysis: M. Badura and G. Skrzyński; processing by M. Holappa).

Table 2. First set of 14C dates calibrated with the OxCal v4.4 software (IntCal20 Northern Hemisphere). Note: *Archaeobotanical analysis and selection of samples for radiocarbon studies by Associate Prof. Monika Badura (Department of Plant Ecology, University of Gdańsk, Poland).

Archaeological Evidence for the Late Bronze/Early Iron Age Colchian Settlement Type in the Colchis

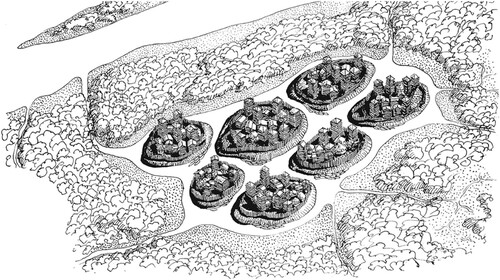

The landscape of Late Bronze/Early Iron Age Colchis was dominated by settlements located on natural or artificial hills. These anthropic mounds are small and middle-sized, circular and/or oval-shaped mounds (Apakidze Citation2005; Sagona Citation2018, 451–452). At first glance, these constructions resemble the earth kurgans of the eastern Georgian landscape or the tell sites in western Asia. Tells, however, refer to mounds that develop through a gradual stratification of successive occupational layers and are mostly made of decayed mudbricks (Lorenzon Citation2021a; Menze, Ur, and Sherratt Citation2006). The Colchis mounds are anthropic constructions consisting of semi-conical earth formations created by massive earth displacement. This type of settlement elevation provided protection against moisture and ensured a stronger defensive position, while also providing a good field of view (). The majority of the excavated mounds present two distinct occupational phases, one dated to the Late Bronze/Early Iron Age and a second occupational phase dated to the Pre-Classical/Classical period (6th–4th centuries b.c.), with no earlier but scattered later occupation attested (Apakidze Citation2005, 175; Hughes Citation2015; Laermanns Citation2018, 87–88). We do observe a few exceptions to these patterns, such as at Naokhvamu, which has one occupation level dated to the Late Bronze/Early Iron Age, and the sites of Pichori, Patriketi, or Namcheduri, which indicate a long continuity of occupation comprising strata from the Proto-Colchian, Ancient Colchian, and Early Classical periods (Kuftin Citation1950; Mikeladze and Khakhutaishvili Citation1985, 11–19). These anthropic mounds are usually of modest size, with Patriketi, located southeast of Kutaisi, being the highest mound of the region at 9 m above ground level. The lowest mounds are almost invisible, with an average height of only 50 cm (Apakidze Citation2005, 175), but on average, Colchis mounds measure approximately 4 m above the modern ground level and present a diameter usually not exceeding 100 m. The largest known mound of the region, Namarnu, is unique with its diameter of 160 m (Mikeladze Citation1982, 34).

Colchian mounds are clustered in three main areas: around the Black Sea shore, on the vast and flat plains between the rivers Inguri and Ghubistskali, and in the area around Kutaisi, within a 30 km radius from the city center (). This latter concentration of settlements was investigated by the KALP project during the 2019–2020 field surveys, which identified new settlements to the west and south of the city center.5 The average surface area of the settlements identified ranges from 0.2–4.5 ha, with the smallest of the cluster measuring just 40 m in diameter, while the largest measures approximately 125 m. The aforementioned Patriketi mound is also part of this concentration. In an adaptation of Apakidze’s initial classification of settlement typology (Citation2005, 178–180), we separated these mound settlements into three different types (see ). Type A is located on an artificially raised hilltop created in the flat and open part of the valley. The settlements are close to rivers or local streams and are surrounded by a system of moats and canals and sometimes also by an earth embankment. Type B is located on natural hills, but unfortunately these have received little attention so far and have been left practically unexplored. Type C is located on river banks and along the Black Sea coast. They are mostly unfortified, such as Bombora, Mokvi, Nosiri I and II, or Qulevi (Gabelia Citation1984, 5; Gogadze Citation1982, 7–9; Mikeladze et al. Citation1974, 28–29). Type C also includes a sub-type called dune settlements, which are located directly on the coastal dunes, such as Pichvnari near Namcheduri.

Figure 7. Map of the Colchian settlements mentioned in the text, divided by type with a focus on the Kutaisi region (Drawing by M. Holappa; data source: Google Earth and Terrametrics 2021).

Within the Kutaisi urban center, the anthropic accumulation associated with the development of the modern city has resulted in the Late Bronze Age levels being located approximate 5 m below the current ground level (Hamburg and Isakadze Citation2018, 146; Isakadze, Hamburg, and Buadze Citation2019, 278–283). This is one of the main reasons why previous archaeological work in the area has not documented the Late Bronze Age levels, as the reports mentioned trenches of “only” 2–3 m in depth (unpublished archaeological reports made by O. Lanchava, G. Kvirkvelia, and D. Berdzeneshvili 1984–1990, courtesy of Kutaisi State Historical Museum archives). The settlements around Kutaisi belong to Types A and B, a fact which is central to understanding the development of the settlement pattern in Colchis during the Late Bronze/Early Iron Age. The majority of the settlements belong to Type A and represent a unique combination of anthropic raised platforms and river canal networks. The wooden platforms were essential to creating an occupational level above the excessively moist soil of the alluvial plain, while the canal system connected the individual settlements and provided stable access to the river. The inhabitants also strengthened the settlements by building architectural structures with a strong defensive role, such as palisades, and by excavating moats that roughly encircled the entire settlement (Sagona Citation2018, 426, 452–453). New geoarchaeological data and aerial images confirmed that the construction materials for these anthropic mounds were likely procured from the area directly surrounding the mounds (Laermanns Citation2018, 87). Defensive architecture from the wide Caucasus presents quite similar characteristics, such as hilltop fortresses and walled complexes (for detailed descriptions, see Hammer Citation2014; Lindsay and Greene Citation2013; Narimanishvili Citation2019; Smith Citation2005), but the distinctive combination of hilltops and natural/artificial canals and moats is a unique characteristic of the Colchis lowlands, indicating a cultural adaptation to specific environmental conditions (Sagona Citation2018, 452–453).

Once the artificial earthen mound was erected, the community constructed a wooden platform made of planks, on top of which houses, towers, and other communal structures were built (Muskhelishvili, Murvanidze, and Jibladze Citation2008; Sagona Citation2018, 456–457). Wooden poles driven into the swampy soil and bound together created a series of pillars for the platform, while horizontally laid timbers created a stable base. One of the best examples of this technique is the site of Anaklia II, which, with its remarkable degree of preservation, illustrates how the elevated wooden platforms prevented buildings from flooding and made them moisture resistant by avoiding direct contact with the soil (Muskhelishvili, Murvanidze, and Jibladze Citation2008; Sagona Citation2018, 456). The platform size corresponded to the occupation area of the buildings and was usually smaller than the earth mound. Settlement expansion was accomplished by erecting new artificial mounds near the core settlement rather than expanding the original mound, as identified by KALP at the site of Maghlaki and by previous studies at Namarnu (Grigolia Citation1973, 51).

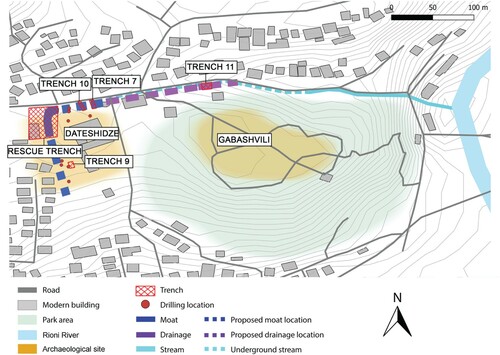

The KALP excavation project, building upon the previous investigations conducted in the area, focuses on the Middle and Late Bronze/Early Iron Age levels within the mound settlements in the Kutaisi urban center, the Gabashvili and Dateshidze hills (Hamburg and Isakadze Citation2018; Lordkipanidze, Lanchava, and Lordkipanidze Citation1994) (). It is possible that during the Bronze Age, the currently separated hills were joined as one settlement, but the modern urban transformations of the city have deeply impacted the landscape, creating two separate mounds. This hypothesis is further supported by the discovery of one defensive moat that encircles both hills with an annexed channel leading to the Rioni River. The moat location highlighted in is based on excavations and surface topography and is further supported by the geoarchaeological drillings made in collaboration with a team of geologists led by Leszek Łęczyński from the Faculty of Oceanography and Geography (Geophysics Laboratory) of the University of Gdańsk in 2021. Unlike the majority of Late Bronze/Early Iron Age settlements of the region classified as Type A, the Gabashvili/Dateshidze settlement is not located on an artificially created mound but belongs to the minority of Type B settlements situated on natural hillocks. We have not discovered any remains of a wooden platform, which would not have occurred on a natural hill settlement, but we were able to identify remains of building and defensive architecture ().

Figure 8. Map of Kutaisi with the moat, excavation, and survey areas (Drawing by R. Bieńkowski, A. Kaliszewska, J. Hamburg, M. Holappa; basic data source: QGIS 3.20).

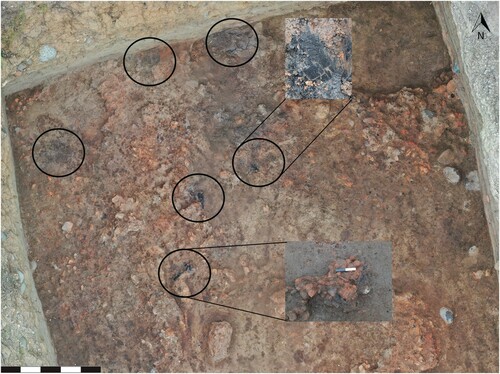

Figure 9. Wooden architectural evidence in trench 9 with the wooden beams found in situ indicated with black circles (Photo credit: J. Hamburg).

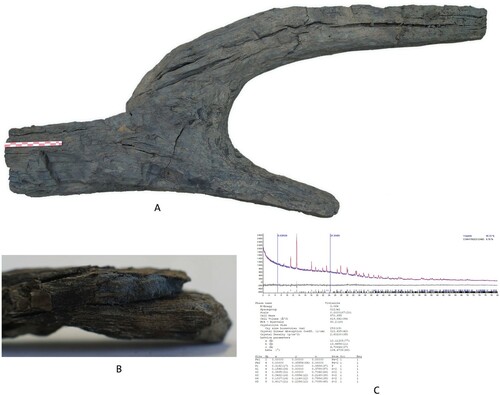

The defensive architecture consisted of a wide moat, embankments, and possibly wooden defensive structures such as palisades, similar to the evidence discovered in the excavation of the Namcheduri settlement (Mikeladze and Khakhutaishvili Citation1985, 20; Sagona Citation2018, 453). Data from aerial imagery, surveys, geoarchaeological drillings, and archaeological excavations seem to indicate that the defensive moat was usually dug further away from the end of the slope, thus including within the defense system areas used for agricultural work. This hypothesis has been validated by the recovery of agricultural tools in these flat areas and, in Kutaisi, by the discovery of a wooden plough found in the subsurface layer of the moat (rescue trench dug for the construction of a sewage treatment plant) on Dateshidze hill (Hamburg and Isakadze Citation2018, 142, fig. 5; Lanchava et al. Citation2018, 137–143) (). For the purposes of this research, we defined a moat as being a wide defensive ditch, surrounding a fortified settlement, purposefully excavated, and filled with water for defensive purposes. The moat seems to have been excavated in one go and then maintained over time, but the current KALP excavation in this area may shed further light on whether this was the case for the full length of the moat and not just trenches 7 and 10, which are currently presented in this paper.

Figure 10. Wooden plough (A) and wood of Pinus sp. (B) with traces of vivianite and C) relative x-ray diffraction graph (Photo of the plough by Sh. Buadze; microphoto of the vivianite traces and x-ray analysis made by P. Bylina).

Likewise, earthen building materials found in the moat filling during the 2019 season in Kutaisi (Gabashvili and Dateshidze hills) attested to the existence of multi-material architectural structures in the immediate vicinity of the moat, likely a system of palisades and watchtowers. The single moat around the Gabashvili/Dateshidze hill settlement was 4.90–5.75 m deep and of variable width, from 8–10 m (Hamburg et al. Citation2019, 48). Analyses of the bluish-violet sediment on organic material (mainly wood) performed by the Warsaw University of Technology showed the presence of vivianite (see ). The appearance of this mineral indicates the continuous presence of standing water in the moat (McGowan and Prangnell Citation2006, 93–111; P. Bylina, personal communication 2020). The KALP survey indicated that the settlements around Kutaisi (i.e., Sakulia, Maghlaki, Zeda Bashi, Partskhanakanevi, and Ianeti) were surrounded by a single moat of an average depth of 4 m and variable width (i.e., from 5 m at Ianeti to 35 m wide at Maghlaki I). The presence of a double moat, with the two moats either located quite close to each other and separated by an embankment (e.g., Kopitnari) or dug at a certain distance to provide farmland for the communities in the area between (i.e., Namarnu, Anaklia, and Nosiri) is attested, although this has only been documented in a minority of settlements (Grigolia Citation1973, 50–51). The canal system was connected to the moat and functioned as a drainage system by regulating the water supply to the farmlands near the settlement, as well as to the moat itself. The canals also connected the moat to nearby rivers, creating a comfortable transportation route between settlements. The marshy environment of Bronze Age Colchis favored the use of water routes as the most convenient and efficient communication and trade network. For instance, around Pichori, the canal system connected four different mound settlements and provided water from the local river to each moat (Baramidze Citation1998, 46). A similar network solution has been discovered at Namarnu, where five mounds were linked through canals and then connected to the river Pichori (Grigolia Citation1973, 50). In the 2020 field season, KALP discovered a similar network between the small and large hills of Maghlaki, and there are also traces of a second canal network connecting this site with the nearby Gubistskhali River. In the Gabashvili/Dateshidze settlement, KALP also identified a drainage mechanism set in place around the moat, which was implemented through a canal system. The only function of the channel discovered in 2019, which connected directly to the moat, seems to have been to drain excess water down the slope towards the Rioni River, preventing the moat from overflowing and causing damage to the nearby farmland. The difference in depth between the base of the moat (trench 7) and the channel (trench 11) was 17.5 m, which guaranteed a sufficiently steep slope to ensure drainage when needed (). Unlike the moat excavation in trenches 7 and 10, limited organic materials and pottery were discovered in the excavation of the drainage channel (trench 11), and there was no detection of vivianite on the organic material.

Figure 11. Profile of the moat found in 2018 near Gabashvili/Dateshidze settlement, trench 7 (Photo credit: R. Bieńkowski; processing by M. Holappa and J. Hamburg).

While it has been challenging to reconstruct the internal layout of these settlements, the archaeological evidence attests that Bronze Age buildings in the Colchis were built mostly from wood and earth (Muskhelishvili, Murvanidze, and Jibladze Citation2008; Sagona Citation2018, 456; Vickers and Kakhidze Citation2001). Anaklia II displays a complex built environment characterized by wooden architecture built on top of a platform measuring 20–25 m2 in which buildings constructed with timber were insulated through the use of earthen building materials (Muskhelishvili, Murvanidze, and Jibladze Citation2008).

An Introduction to Late Bronze Age Colchian Architecture and Building Systems in Kutaisi

The Bronze and Early Iron Age architecture from the mound and hilltop settlements in the Colchis lowlands can be divided into two categories: 1) free-standing wattle and daub architecture, present to some degree in the majority of the settlements and 2) wooden architecture. Both techniques were used on rectangular and/or square buildings with an interior division into multiple rooms (Apakidze Citation2005; Sagona Citation1993, 454–465; Citation2018, 233). The vernacular architecture of Colchis did not rely on mudbricks or ashlar; instead, they made extensive use of wood, small stones, and plastic earthen materials (PEM) in construction (on PEM, a typology of earthen building materials of flexible use, see Devolder and Lorenzon Citation2019). Within the broad definition of wattle and daub and wooden architecture, it is essential to distinguish meaningful differences in manufacturing and construction techniques that reflect the diverse architectural traditions within the region. Simply put, the type of soil, the type of wood, and the type of vines employed to link the wattle to the wooden beams are all important and distinctive elements of each architectural tradition, a choice mitigated by the environment, as well as socio-cultural factors (Lorenzon Citation2021b; Rapoport Citation1969, 47).

To better recognize these differences and be able to gauge the level of craftsmanship, social constraints, and skilled labor involved in Bronze/Early Iron Age building processes, a comprehensive understanding of the chaîne opératoire and building materials involved in the different sub-genres of the Colchis wattle and daub and wooden architecture is paramount (Aurenche Citation1981; Duru Citation1996; Lorenzon Citation2021a). The building materials documented during surveys and excavations highlight some of the relevant traditional construction and manufacturing choices.

The use of stone

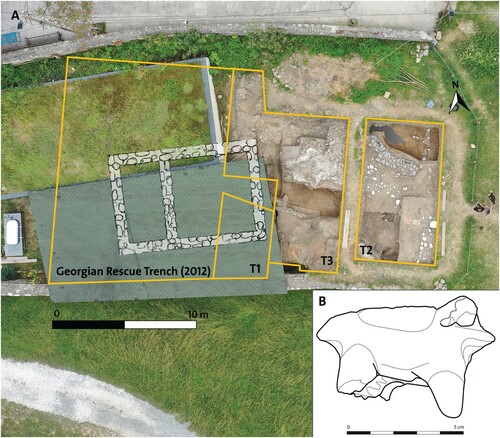

In the Colchis lowlands during the Late Bronze/Early Iron Age, the use of stones was limited to foundations and sometimes stone socles in order to prevent capillary humidity, a marked difference from the increased incidence of stone architecture that characterized eastern Georgia in the Middle Ages and modern periods (Sagona Citation2018, 379). Although the use of stone foundations is quite rare and, according to Georgian archaeologists, reserved for religious or other public buildings (R. Isakadze and G. Kvirkvelia, personal communication 2020), the use of a limited amount of limestone that was originally collected from the Rioni riverbed was documented in a building foundation at the site of Gabashvili, but these stones were used without any dressing or cutting. In 2019, at the site of Bagrati, we recorded the use of stones as a shallow stone socle made of two courses to support a wooden superstructure, while clay figurines were found within the structure, indicating a likely religious function for the architecture (B). A similar structure was found during the research at Gabashvili (unpublished archaeological reports made by O. Lanchava, G. Kvirkvelia, and D. Berdzeneshvili 1984–1990, courtesy of Kutaisi State Historical Museum archives). These stones were joined together by mud mortar, created with local red soil and limited vegetal inclusions.

The use of organic material: wood and vegetal fibers

Wooden logs were employed to a different extent in both construction techniques used in Colchis. Timber was used as vertical and horizontal supports in wooden architecture and as a frame in the wattle and daub constructions. Analysis of the wooden material recovered from Anaklia II indicated that the wood was locally sourced from the nearby forests, cut into rounded wooden beams, and then employed as key architectural elements after having been debarked and seasoned (Muskhelishvili, Murvanidze, and Jibladze Citation2008). Ethnographic research on vernacular architecture indicated that the wooden logs were likely first positioned horizontally to create four perpendicular walls, the perimetral walls of the structure. Then, logs would have been superimposed on one another and joined at the corner through a notch and pass corner (Kipiani and Amashukeli Citation1995, 19–21, pl. I). The slanted roof may have been constructed from wooden beams covered in thatch or possibly by the progressive shortening of the wooden beams in elevation, thus creating a pseudo corbelled vault with logs (Kipiani and Amashukeli Citation1995, 19–21). The resulting spaces between the beams were filled by mud plaster in order to create an insulation effect and protect the occupants from cold and humidity (B). Wooden beams were recovered in situ at the site of Dateshidze, thus providing concrete evidence of this technique during the Late Bronze Age/Early Iron Age (see ).

Figure 13. A) Wattle and daub fragment, trench 3, level 5; B) earthen building materials from trench 9, level 4; C–D) triangular earthen building material with a beam impression from trench 2, indicating the use of wooden elements in level 18 wall elevation; E) wattle and daub fragment, trench 9, level 5; F–G) earthen building materials from trench 10, level 2, cutting of the moat (F) and level 3 (G); and, H) wattle and daub from trench 9, level 5 (Photo credit: M. Lorenzon).

In the wattle and daub technique, wooden posts were located at the corner of the buildings to create the perimeter for the structure and also alongside the length of the wall to guarantee structural stability and as an anchor to attach the wattle, which was created with reed (Friesem, Wattez, and Onfray Citation2017; Wright Citation2009, 118–121). In Dateshidze/Gabashvili and Bagrati, most of the wooden beams used in wattle and daub were likely sourced from local species, such as the oaks used in the moat defensive structure.6 These were employed as vertical supports by creating a rounded beam of approximately 20 cm in diameter. Wooden posts were inserted into the ground, or into the foundation, by creating a pointed end. Rounded wooden beams were also used to create the ceiling structures, but in this case, the diameter of the supporting beams could exceed 20 cm. The space between the wooden posts was filled with a wattle structure consisting of an interwoven mesh of reeds, branches, or twigs (D). The construction of the wattle was clearly visible in the impressions left on the daub at Dateshidze (H). In the Colchis lowlands, reeds were usually collected in the marshy areas, as they grew naturally in the waterlogged environment, but small branches could also be used (Gamkrelidze Citation2012, 216). The thickness of the branches could vary from 2–4 cm in diameter, as recorded in Dateshidze. A certain flexibility is required of the reeds so that they can be woven to create the vertical wall skeleton, which is then covered with daub (A, H).

The use of soil

Sediments employed in earthen building materials were used for the creation of daub, PEM/mud plaster, and mortar used to bind together stones in foundation trenches. The soil originates from the alluvial sediments of the Rioni, a mix of clayish red soil with a small silt percentage. The sediment mixture used for the daub is often enriched with organic matter but to a lesser degree than traditional plaster manufacture. In the chaîne opératoire, once the sediment is collected, it is mixed with vegetal temper, consisting of chaff and other aggregates (i.e., sand and gravel) to obtain a viscous mixture that can be thrown or pressed against the wattle to create a 3–4 cm layer on the external and internal surface of the wall from the ground to the roof level (Aurenche Citation1981, 88; Kruger Citation2015). PEM/mud plaster with a high vegetal temper concentration was used to plaster wattle and daub and wooden architecture (see ). In this latter case, PEM was often employed to fill the interstices between beams. Mud plaster mixed with lime could also be used as floor plaster, and it was also painted with different colors when used on the internal walls (Sagona Citation2018, 233).

Bronze and Iron Age Earthen Building Materials from Kutaisi

KALP conducted archaeological excavations in three different areas of Kutaisi—Dateshidze, Gabashvili, and Bagrati—resulting in numerous finds of earthen building materials (see ). These latter were incredibly well preserved, due to the destruction of the buildings in a conflagration, and can provide new information on Bronze and Iron Age construction techniques in Kutaisi. This study points to the presence of three distinctive architectural techniques that were implemented synchronically: wattle and daub, PEM with a rubble foundation and/or small stone socle, and mud plaster employed as an insulation buffer in wooden architecture. Additional earthen building materials may have been associated with roofing structures, as preliminary evidence also indicates the extensive use of vegetal fibers and earth in ceilings.

Earthen materials recovered from trenches 2 and 3 at Bagrati include fragments of mud plaster used to insulate a wooden construction. Numerous PEM triangular pieces show clear indications of beam impressions, supporting the theory of the use of PEM in the sealing of wooden structures for temperature control and humidity protection. The quantity of material recovered from trench 2 indicates that the structure could have been no more than one storey in height. Trench 3 presents a more composite picture, with building materials of diverse natures and periods (Ottoman, Byzantine, and Late Bronze/Early Iron Age). The Iron Age levels present an abundance of triangular PEM and signs of mud plaster and PEM used alongside wooden architecture.

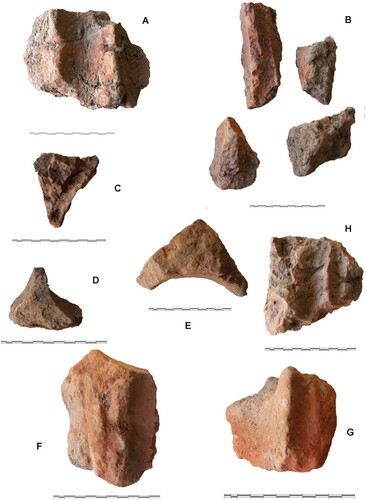

The excavations on the hills of Dateshidze and Gabashvili, based on trenches 9 and 10, provided additional earthen building materials, as well as more information on the settlement typology. Trench 9 was located in the area of School No. 20, the previous location of a basin. A huge cluster of burned wooden beams and earthen building materials was found under a 1.5 m thick recent occupation deposit, mainly linked to the construction of the school’s infrastructure. The architectural finds still in situ documented a building and its collapse (). The excavation area is located near the moat on its northwestern inner side. In addition to the architecture, black Colchian pottery, the remains of a large storage jar, and a bronze arrowhead of foreign provenance were also recovered in this trench. The extension of the excavation area around the southern side of the building identified and highlighted the presence of a domestic area nearby, suggesting that the buildings were not constructed so as to be tightly attached to each other. A limited sondage carried out in the southwestern side of trench 9 provided a high concentration of earthen building materials and diagnostic pottery, such as vessels with animal horn-like motifs on the handle and beakers with a pointed base, typical of Late Bronze/Early Iron Age Colchian culture (Apakidze Citation2008, 335–337, 359–360, 364-5, 367, figs. 10, 11, 15, 16, 18). In addition, we recovered tuyeres and bronze and iron slag, likely evidence of metallurgical activity (see ). The majority of the earthen building materials from trench 9 were fragments of daub, indicating that the architecture identified could have had a wall elevation made of wattle and daub. Extensive traces of reed impressions seem to indicate that the daub structure was created not by interwoven reeds but by reeds laid parallel and likely tied together with a vine. The fragments of daub indicate the use of the local clayish soil and vegetal temper in the form of cereal chaff, which seems to suggest the use of agricultural soils after the time of threshing as a likely source for raw materials. A few PEM fragments identified as ceiling elements indicated the presence of wooden beams that supported a sloped, possibly thatched roof.

Figure 14. Trench 9 with traces of earthen building materials and wooden architecture visible during the excavation in Dateshidze (Photo credit: R. Bieńkowski).

Trench 10 was located at the intersection of the hills with the ancient moat, near the entrance of School No. 20. Late Bronze and Early Iron Age materials were discovered under 2 m of modern occupational deposits. Diagnostic Late Bronze and Early Iron Age Colchian pottery was identified in the fill of the moat, in addition to one example of an imported Greek vessel (6th–4th century b.c.), a fragment of a Colchian amphora, and a stone mould for axes with asymmetrical blades (see ). Trench 10 also contained a large quantity of earthen materials, PEM, and daub fragments, with numerous wooden beam impressions indicating the presence of an articulated architectural structure made of wattle and daub. The wattle was manufactured with parallel reeds/canes of 2.5 cm diameter tied with vines. The PEM and mud plaster fragments were well preserved, even inside the moat, due to the conflagration, and indicated the presence of extensive wooden architecture in the area around the moat, possibly a defensive structure (C–D).

Before the Greeks: A Preliminary Analysis of Colchian Architectural and Settlement Practices in Kutaisi

The KALP contribution provided new data to better understand LBA/EIA settlement typologies around Kutaisi based on the comparison with previously excavated settlements in western Georgia and sheds light on the complex relationship between communities and the natural environment. Our analysis indicates that, although Colchian lowlands are characterized by similarity in material culture, the political organization of these communities was likely tribal, lacking the cohesion of a single, unified political entity. We also highlight a distinct cultural component in the settlement pattern around Kutaisi in which hilltop defensive architecture is integrated with moats and canals, evidencing the LBA/EIA community’s adaptation and exploitation of their natural environment.

The analysis of the settlement typology and building techniques used in the Colchis lowlands indicates that there was regionalization in both, although there are strong similarities between Bronze and Iron Age settlement patterns due not only to environmental constraints (i.e., the marshy land) but also to a clear commonality in tradition, as indicated by the evidence recorded by KALP. The analysis of the settlement pattern of the Kutaisi landscape, including the sites of Gabashvili, Dateshidze, and Bagrati, highlights several aspects. First, Kutaisi is the first Type B settlement identified in the area that has been systematically excavated. Our survey and excavation data shows that there are two separate sites within the boundaries of the city: the settlement of the Gabashvili/Dateshidze hills and a second site located near the medieval Bagrat III Cathedral (Bagrati), which was likely a religious center, as evidenced by the stone foundations of the building and the clay figurines found in situ. Second, the survey highlighted the development of Type A settlements in the area around Kutaisi, some of which have a nucleated character; i.e., development occurs around one mound.

All of the settlements that have been identified were surrounded by a moat (of either one or two lines) and possibly wooden fortifications, highlighting the defensive character of the settlements. A few sites show traces of a network of canals connecting the moats with nearby rivers, confirming the existence of water routes between the settlements. Third, KALP confirmed the existence of a single moat surrounding the Late Bronze and Early Iron Age settlement of Gabashvili/Dateshidze; the moat measured approximately 10 m in width and was part of a more complex system of defenses articulated around wooden and earthen architecture palisades. This discovery tightly links Kutaisi settlements with the architectural cultural practices of the region, showing an integrated defensive system that combined wooden and earthen architecture with water management systems. The discovery of the drainage channel indicates that some of these waterways were not used for transport but only for drainage purposes, providing new insight into water management during the LBA/EIA. Fourth, laboratory results of radiocarbon dating on the material discovered in the moat at Gabashvili/Dateshidze indicate that the Colchian sites may be older than previously assumed. Finally, earthen building materials, specifically PEM, were extensively used in domestic and defensive architecture in conjunction with wooden logs. These materials indicate a strong vernacular tradition within Gabashvili/Dateshidze, which is slightly different from Bagrati, raising questions about craft specialization and standardization of practices in public building and defense structures. This analysis of the earthen building materials recovered in Bagrati shows strong similarities to the Bronze Age construction techniques identified in the Gabashvili/Dateshidze hills. The few wooden beam impressions seem to indicate the presence of a vernacular structure built with wooden logs that overlapped the area of trenches 1 and 3. This structure had stone foundations, but the northern part of the wall was situated directly on bedrock. The foundation trench indicates a construction process that made use of river stones for the foundation, bonded together by mud mortar, which created a levelled surface for the wooden wall elevation.

The finds from both trenches 9 and 10 in the Gabashvili/Dateshidze mound settlement indicate that the main raw material source for the daub was the neogenic clayish soil of the local alluvium. The survey identified at least two possible local sources of material procurement—one particularly rich in iron and another with a high combination of iron and manganese—but further geoarchaeological analysis is needed to be able to pinpoint the Bronze/Iron Age source exactly. The high incidence of the use of cereal chaff as vegetal temper in the daub, PEM, and mud plaster also provides us with information about agriculture practices, as the chaff used in earthen building materials was identified as an agriculture by-product, specifically from barley and millet, indicating an opportunistic use of raw materials.

However, the question remains as to what induced people to live in houses built on marshland. Most probably, the Colchian residents began to build their dwellings on the marshy lands, since such settlements were almost inaccessible, built along the river, and easy to defend. The lidar studies that will be carried out during the next field season will hopefully help us answer these questions and determine the extent and types of connectivity between the marshland sites in the region.

Authors’ Contributions

J. H. and M. L. developed the conceptual framework; J. H. conducted the survey, archaeological fieldwork, settlement analysis, and historical research; M. L. conducted the archaeological fieldwork, architectural analysis, and study of earthen building material; and, J. H. and M. L. developed the interpretation and wrote the paper.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Associate Prof. Roland Isakadze, Dr. Guram Kvirkvelia, Associate Prof. Monika Badura, Associate Prof. Leszek Łęczyński, Dr. Rick Bonnie, Dr. Maria Gabriella Micale, and Ms. Agnieszka Kaliszewska for providing insightful comments that helped us improve this article. We are also grateful to Mrs Maija Holappa, Mr. Rafał Bieńkowski, and Mr. Giorgi Lezhava, who helped with the images. Finally, we thank the Polish National Foundation for funding a grant to Mr. Hamburg to conduct research and allowing Dr. Lorenzon to take part in KALP (formerly EKAL). This allowed the authors to collaborate in person on this article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jacek Hamburg

Jacek Hamburg (M.A. 2013, University of Warsaw) is the Chancellor of the Science Station at the Krukowski Polish-Georgian Interdisciplinary Research Center and a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Warsaw. Mr. Hamburg focuses on the archaeology of the Late Bronze Age in the Caucasus and Middle East. He is directing multiple archaeological projects in the territory of Georgia and is a member of other joint excavation projects working in Israel and Cyprus. His field of expertise is archaeometallurgy. Since 2017, he has been researching residues related to the Colchian culture.

Marta Lorenzon

Marta Lorenzon (Ph.D. 2017, University of Edinburgh) is a University Researcher at the Centre of Excellence in Ancient Near Eastern Empires, University of Helsinki. Lorenzon has a background in Mediterranean archaeology with a core expertise in architectural anthropology, building archaeology, and geoarchaeology. She has conducted research at numerous sites in Europe, the Americas, and Asia with a research focus on architecture, identity construction, and the relationship between the natural and built environment. She is the PI of “Building sustainability: Investigating earthen architecture and social practices in the Ancient Near East” and “Building Identities in Border Areas: cultures, narratives and architecture,” funded by the University of Helsinki.

Notes

1 Based on A. Kirk Grayson, Assyrian Rulers of the Early First Millennium b.c. II (858–745 b.c.) (RIMA 3), Toronto, 1996.

2 Catalogue nos., again, based on A. Kirk Grayson, Assyrian Rulers of the Third and Second Millennia b.c. (to 1115 b.c.) (RIMA 1), Toronto, 1987.

3 Based on A. Kirk Grayson, Assyrian Rulers of the Early First Millennium b.c. I (1114–859 b.c.) (RIMA 2), Toronto, 1991.

4 Based on A. Kirk Grayson, Assyrian Rulers of the Early First Millennium b.c. I (1114–859 b.c.) (RIMA 2), Toronto, 1991.

5 All sites south and west of Kutaisi: Maghlaki (I and II), Partskhanakanevi, Ianeti, Kopitnari, Zeda Bashi, Shua Bashi, Etserbashi, Sakulia, Meskheti, Patriketi, Rionhesi, Gubitskhali hill, Oktomberi, and Tsikhia (I and II); only a couple of them are new (some were known but neither surveyed nor excavated, i.e., were untouched by archaeologists).

6 Preliminary identification in the field of moat wooden materials was carried out by our archaeobotanist, Associate Prof. Monika Badura from the University of Gdańsk, Poland.

References

- Aeschylus. Προμηθϵὺς Δϵσμώτης.

- Apakidze, J. 2002. Gvianbrinjaosa da Adrerkinis Khanis Kokhuri Kulturis Kronologia. Istoriis Metsnierebata Doktoris Sametsniero Khariskhis Mosapoveblad Tsarmodgenili Disertacia. Sakartvelos Metsnierebata Akademiis Arkeologiuri Kvlevis Tsentri. Tbilisi: Mecniereba.

- Apakidze, J. 2005. “Towards the Study of Late Bronze and Early Iron Age Settlement and Settlement Systems of the Colchian Culture in Western Georgia.” Archäologische Mitteilungen aus Iranund Turan 37: 175–187.

- Apakidze, J. 2008. “Ancient Colchian Pottery from Georgia.” In Ceramics in Transitions: Chalcolithic Through Iron Age in the Highlands of the Southern Caucasus and Anatolia, edited by K. S. Rubinson, and A. Sagona, 323–368. Leuven: Peeters.

- Apollonius Rhodius. Argonautica.

- Arrian. Periplus Ponti Euxini.

- Aurenche, O. 1981. La Maison Orientale: L'Architecture du Proche Orient Ancien des Origines au Milieu du Quatrième Millénaire. Paris: Paul Geuthner.

- Baramidze, M. 1977. Merheul'skij Mogil'nik. Tbilisi: Mecniereba.

- Baramidze, M. 1998. “Vostochnoe Prichernomor’e vo II – pervoi polovine I tys. do n.e.(osnovnye problemy).” Doctor of Historical Sciences diss., Tbilisi.

- Baramidze, M. 1999. Nekotorye Problem Arkheologii Zapadnogo Zakavkaz’ya v III – I tys. Do n.e. Razyskaniya po Istorii Abkhazii. Tbilisi: Mecniereba.

- Bird, D. W., and J. F. O’Connell. 2006. “Behavioral Ecology and Archaeology.” Journal of Archaeological Research 14 (2): 143–188. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10814-006-9003-6.

- Blanton, R. E. 1994. Houses and Households: A Comparative Study. New York: Springer Science & Business Media.

- Bondyrev, I. V., Z. V. Davitashvili, and V. P. Singh. 2015. The Geography of Georgia: Problems and Perspectives. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-05413-1.

- Borgerhoff Mulder, M. 2013. “Human Behavioral Ecology—Necessary but Not Sufficient for the Evolutionary Analysis of Human Behavior.” Behavioral Ecology 24 (5): 1042–1043. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/ars223.

- Braund, D. C. 1994. Georgia in Antiquity. A History of Colchis and Transcaucasian Iberia, 550 BC-AD 562. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Braund, D. C. 2012. “Colchis.” In The Oxford Classical Dictionary, edited by S. Hornblower, A. Spawforth, and E. Eidinow. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Accessed December 22, 2020. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/https://doi.org/10.1093/acref/9780199545568.001.0001/acref-9780199545568-e-1720?rskey=jzwFUB&result=1736.

- Bremmer, J. N. 2007. “The Myth of the Golden Fleece.” Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions 6: 9–38.

- Burney, C., and D. M. Lang. 1971. The Peoples of the Hills: Ancient Ararat and Caucasus. History of Civilization series. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Burney, C., and D. M. Lang. 1975. Die Bergvölker Vorderasiens. Armenien und der Kaukasus von der Vorzeit bis zum Mongolensturm. Essen: Magnus.

- Connor, S. E. 2011. A Promethean Legacy: Late Quaternary Vegetation History of Southern Georgia, The Caucasus. Ancient Near Eastern Studies, Supplement 34. Leuven: Peeters.

- Connor, S. E., I. Thomas, and E. V. Kvavadze. 2007. “A 5600-Yr History of Changing Vegetation, Sea Levels and Human Impacts from the Black Sea Coast of Georgia.” The Holocene 17 (1): 25–36.

- Devolder, M., and M. Lorenzon. 2019. “Minoan Master Builders? A Diachronic Study of Mudbrick Architecture in the Bronze Age Palace at Malia (Crete).” Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique 143 (1): 63–123.

- Dinçol, A. M., and B. Dinçol. 1992. Die Urartäische Inschrift aus Hanak. Ankara: FS Sedat Alp.

- Diodorus Siculus. Bibliotheca historica.

- Duru, R. 1996. “The Neolithic Transition from Village to Town in the Lake District.” In Housing and Settlement in Anatolia: A Historical Perspective, edited by M. Sozen, and Y. Sey, 49–59. Istanbul: Turkiye Ekonomik ve Toplumsal Tarih Vakfi.

- Dyakonov, I. M. 1968. “Glava II. Istoriya Armyanskogo Nagor'ya v Epokhu Bronzy i Rannego Zheleza.” In Predystoriya Armyanskogo Naroda. Istoriya Armyanskogo Nagorya s 1500 po 500 g. do n. e. Khetty, Luviytsy, Protoarmyane. Yerevan: Akademia Nauk Armianskogo, SSR Publ.

- Dyakonov, I. M., and S. M. Kashkay. 1981. Répertoire Géographique des Textes Cunéiformes 9, Geographical Names According to Urartian Texts. Wiesbaden: Reichert.

- Erb-Satullo, N. L., B. J. Gilmour, and N. Khakhutaishvili. 2017. “Copper Production Landscapes of the South Caucasus.” Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 47: 109–126.

- Friesem, D. E., J. Wattez, and M. Onfray. 2017. “Earth Construction Materials.” In Archaeological Soil and Sediment Micromorphology, edited by C. Nicosia, and G. Stoops, 99–110. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Gabelia, A. N. 1984. Poseleniya Kolkhidskoy Kul'tury (na Materialakh Abkhazii). Moskva: Institut Arkheologii Akademii Nauk SSSR 1984.

- Gamkrelidze, G. 2012. Researches in Iberia-Colchology (History and Archaeology of Ancient Georgia). Tbilisi: Georgian National Museum, Otar Lordkipanidze Centre of Archaeology

- Gobejishvili, N. 2014. Samarkhta Konstrukcia da Dakrdzalvis Tsesi Kolkhuri da Kobanuri Kulturebis Mikhedvit. Tbilisi: Georgian National Museum.

- Gogadze, E. 1982. Kolkhetis Brinjaosa da Adreuli Rkinis Khanis Namosakhlarta Kultura. Tbilisi: Metsniereba.

- Gogadze, E. 1984. K voprosy o khronologii i periodizatsii pamjatnikov kolkhidskoi kultury, Sakartvelos sakhelmtsipo muzeumis moambe. Bulletin of the State Museum of Georgia, XL-B: 28–52.

- Grigolia, G. 1973. “Barbarosebis Didi Kalakis Lokalizatsiisatvis.” Jeglis megobari 33: 50–58.

- Hamburg, J., M. Badura, G. Skrzyński, A. Kaliszewska, and R. Bieńkowski. 2019. “Preliminary Results of Archaeological and Archaeobotanical Investigation of the Defensive Moat Found in Kutaisi (Western Georgia).” Pro Georgia: Journal of Kartvelological Studies 29: 43–62.

- Hamburg, J., and R. Isakadze. 2018. “Preliminary Report of 2017 Polish-Georgian Archaeological Expedition at Gabashvili Hill and Its Surroundings Area (Kutaisi, Western Georgia).” Pro Georgia: Journal of Kartvelological Studies 28: 137–155.

- Hamburg, J., and K. Pawłowska. 2017. “Metal Garment Elements from the Late Bronze Age – Early Iron Age Cemetery at Beshtasheni (Eastern Georgia).” Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean 26: 601–618.

- Hammer, E. 2014. “Highland Fortress-Polities and Their Settlement Systems in the Southern Caucasus.” Antiquity 88: 757–774.

- Haratyunyan, B. A. 1998. “K Voprosu ob Etnicheskoy Prinadlezhnosti Naseleniya Basseyna Reki Chorokh v VII—IV vv. do n. E.” Istoriko-filologicheskiy zhurnal 1–2: 233–246.

- Haratyunyan, B. A. 2001. Korpus Urartskikh Klinoobraznykh Nadpisey. Yerevan: Gitutyun.

- Harris, M. 1976. “History and Significance of the EMIC/ETIC Distinction.” Annual review of anthropology 5 (1): 329–350.

- Herodotus. 1920. Historiae = Herodotus, with an English Translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Hippocrates. Πϵρὶ ἀέρων, ὑδάτων, τόπων.

- Ho, J. W., and N. L. Erb-Satullo. 2021. “Spatial investigation of technological choice and recycling in copper-base metallurgy of the South Caucasus.” Archaeometry.

- Hughes, R. 2015. “The Archaeology of a Colchian Landscape: Results of the Eastern Vani Survey.” Unpublished PhD diss., Department of Classical Art and Archaeology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

- Isakadze, R., J. Hamburg, and Sh. Buadze. 2019. “Kartul-polonuri Ekspeditsiis Mier 2018 Tcels Kutaisshi Chatarebuli Arqeologiuri Kvlevebis Mokle Angarishi.” In 2018 Tcels Chatarebuli Arqeologiuri Gatxrebis Mokle Angarishebis Krebuli, 278–283. Tbilisi.

- Jibladze, L. 1997. Kolkhetis Dadoblis Brinjaos Khanis Namosakhlarta Stratigrafia, Kronologia da Periodizatsia / Chronology, Stratigraphy and Periodization of the Bronze Age Settlements in the Colchian Lowland. Tbilisi: Sakartvelo.

- Jibladze, L. 2002. Kolkhetis Dadoblis dz. ts. III-II Atastsleubis Namosakhlerbi / The 3rd and 2nd Millennium BC Settlements from the Colchian Lowland. Tbilisi: sakartvelos metsnierebata akademiis arkeologiuri kvlevis centri / Center of Archaeological Studies, Georgian Academy of Sciences.

- Kavtaradze, G. L. 2002. “An Attempt to Interpret Some Anatolian and Caucasian Ethnonyms of the Classical Sources.” Sprache und Kultur 3: 68–83.

- Kennett, D. J., and B. Winterhalder2006. Behavioral Ecology and the Transition to Agriculture (Vol. 1). Univ of California Press.

- Kipiani, G., and N. Amashukeli. 1995. “Колхские” и “Фригийские” дома. Vitruvius II, I, 4 5. “Colchian” and “Phrygian” houses. Translated from Georgian. Shalva Amiranashvili State Museum of Art of Georgia.

- Koberidze, G. 1929. “Diaokhi: Georgian Prehistory.” In Historischer Schul-Atlas, edited by F. W. Putzgers. Leipzig: Velhagen & Klasing.

- Kohl, P. L., and V. Trifonov. 2014. “The Prehistory of the Caucasus: Internal Developments and External Interactions.” In The Cambridge World Prehistory, edited by C. Renfrew, and P. G. Bahn, 1571–1595. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Köroǧlu, K. 2001. “Urartu Krallığının Kuzey Yayımı ve Qulha ülkesinin Tarihi Coğrafyası.” Belleten 64: 717–741.

- Köroǧlu, K. 2005. “The Northern Border of the Urartian Kingdom.” In Altan Çilingiroǧlu/G. Darbyshire (Hrsg.), Anatolian Iron Ages 5, Proceedings of the 5th Anatolian Iron Ages Colloquium Van, 6.–10. August 2001. Ankara Monograph 3, 99–106. Ankara: British Institute of Archaeology.

- Kruger, R. P. 2015. “A Burning Question or, Some Half-Baked Ideas: Patterns of Sintered Daub Creation and Dispersal in a Modern Wattle and Daub Structure and Their Implications for Archaeological Interpretation.” Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 22 (3): 883–912.

- Kuftin, B. A. 1950. Materialy k Arkheologii Kolkhidy, vol. 2: Arkheologicheskie Izyskaniia v Rionskoi Nizmennosti i na Chernomorskom Poberezhʹi. Tbilisi: Tekhnika da shroma.

- Laermanns, H. 2018. “A Palaeogeographic and Geoarchaeologic Study on the Colchian Plain Along the Black Sea Coast of Georgia.” PhD diss., Universität zu Köln.

- Laermanns, H., G. Kirkitadze, S. M. May, D. Kelterbaum, S. Opitz, A. Heisterkamp, G. Basilaia, M. Elashvili, and H. Brückner. 2018. “Bronze Age Settlement Mounds on the Colchian Plain at the Black Sea Coast of Georgia: A Geoarchaeological Perspective.” Geoarchaeology 33 (4): 453–469.

- Laguens, A. G. 1988. “la Distinción Emic-Etic en Arqueología.” Boletín de Antropología Americana 17: 133–144.

- Lanchava, O., R. Iskadze, J. Hamburg, Sh. Buadze, R. Bieńkowski, A. Kaliszewska, and K. Pawłowska. 2018. “kutaisis Kartul-Polonuri Ekspeditsiiis 2017 Tslis Arkeologiuri Samushaoebis Angarishi.” In 2017 Ts’els Chat’arebuli Arkeologiuri Gatkhrebis Mok’le Angarishebis K’rebuli, 137–143. Tbilisi.