Abstract

What is the effect of gender on the deliberative process of judging? Drawing on previous research on female leaders’ inclination to foster a more inclusive and collaborative decision-making process, we argue that decision making takes more time in a collegial court when female justices preside over decisional panels. Analyzing an original data set on cases decided by the Norwegian Supreme Court between 2008 and 2019, we find that when a woman is the presiding justice, the duration of case disposition time increases. This effect, however, persists for only eight days. Our finding suggests that institutional practices take effect over gendered effects.

Introduction

What affects the amount of time judges on a collegial court spend disposing cases? While a significant body of literature has investigated this question by treating the case disposition time as a matter of judicial (in)efficiency (Bielen and Marneffe Citation2017; Cauthen and Latzer Citation2008; Christensen and Szmer Citation2012; Szmer, Christensen, and Kuersten Citation2012), a growing but still scattered set of studies have taken a different perspective, forging the conceptual link of case disposition time with small-group dynamics and considering it a characteristic manifestation of the extent of bargaining and compromise among judges before they arrive at a final judgment (Maltzman, Spriggs, and Wahlbeck Citation2000; Nie, Waltenburg, and McLauchlan Citation2019; Palmer and Brenner Citation1990; Rathjen Citation1980). These studies have found that the duration of case disposition time can indeed be explained by factors that tap into the amount of effort required to build a consensus in collegial courts, including case complexity, case salience, the ideological heterogeneity among judges, and the ideological proximity of judges to their external audiences. What is missing in these studies, however, is the role of judicial leadership. This is unfortunate, considering that a long line of research has demonstrated the impact of chief justices’ idiosyncratic leadership styles on various aspects of case disposition such as opinion assignment, deliberation dynamics, and workload management (Corley, Steigerwalt, and Ward Citation2013; Hendershot et al. Citation2013).

In this article, we begin to fill the gap by studying how female leadership in a collegial court influences the levels of bargaining and compromise among judges as indicated by the amount of time they spend disposing cases. Our focus on the gendered aspect of judicial leadership is informed by a significant line of inquiry into the role of sex in judicial decision making. Scholars have found that in certain types of cases female judges tend to vote in favor of the plaintiffs (Boyd Citation2016; Johnson, Songer, and Jilani Citation2011; Moyer and Haire Citation2015; Moyer and Tankersley Citation2012; Songer, Davis, and Haire Citation1994) and affect how their male colleagues judge (Boyd, Epstein, and Martin Citation2010; Songer, Radieva, and Reid Citation2016). Evidence has also shown that female or minority dominated panels on the US courts of appeals produce majority opinions with broader issue coverage (Haire, Moyer, and Treier Citation2013). More closely related to our research is a burgeoning literature that has systematically examined how the distinct leadership style of women judges bears on not only legal outcomes, for example, case settlement in trial courts (Boyd Citation2013), but also the processes of judging in collegial courts through which the majority coalitions are built and unanimous decisions are formed (Leonard and Ross Citation2020). We continue with this latter process-oriented approach and examine the impact of female leadership on the amount of time required to hammer out divergent views in the actual processes of panel deliberations.

Theoretically, we argue that it will take longer for a collegial court to render a final decision on the merits when a woman is responsible for managing the processing of a case. This theoretical expectation builds on the well-established differences in the leadership styles of men and women in the existing literature. More specifically, women tend to follow a democratic leadership style that encourages a more inclusive deliberative environment. Women leaders are also more likely to adopt an integrative approach of dispute resolution that fosters collaboration and consensus among group members. Women leaders’ inclination to consider more voices and their devotion to achieving communal goals are even more pronounced in collegial decision-making bodies where the norm of consensus is prevalent. Because encouraging and accommodating more voices and finding common ground between usually starkly opposing views involve substantial efforts and time, it follows that the duration of time taken to render a decision on the merits in collegial courts will be longer when women judges take the leading position.

Empirically, we analyze an original data set of 1,552 decisions handed down between 2008 and 2019 by the Norwegian Supreme Court’s rotating, five-member merits panels. One major analytical advantage provided by the case of the Norwegian Supreme Court is the considerable variation in the gender of presiding justices across rotating panels and years (see our detailed explanation below). Findings from our event history analyses of the duration of case disposition time show that panel deliberations take more time when a woman is the presiding justice, but this gendered pattern of decisional time dissipated after slightly more than one week. This nuanced finding adds to our understanding of the significant but time-bounded impact of female leadership on the deliberative operations of collegial institutions.

By articulating the theoretical linkage between female leadership and richer panel deliberations and demonstrating its observable manifestation in longer decisional time, our study makes three major contributions to the literature on judicial politics. First, we add to the large literature on case disposition time by examining the impact of leadership style that has long been considered to shape the processes of judicial decision making. Second, and relatedly, this study speaks to a burgeoning literature on gendered judging. Although these studies have greatly improved our understanding of whether and under what circumstances sex influences judicial outcomes, we know considerably less about how gender differences might affect the “give-and-take processes of decision making” among judges on collegial courts (Haire, Moyer, and Treier Citation2013, 307). Our analysis sheds important light on the effect of gendered leadership on the decisional process rather than the vote on the merits. Finally, by situating our analysis in the context of the Norwegian Supreme Court, we extend empirical work on judicial politics beyond the American judicial system, thereby helping to break the binds that tie the development of systematic understandings of legal institutions to “the inevitable peculiarities of the U.S. context” (Atkins Citation1991, 881).

Female leadership and the duration of case disposition time

Decision making in groups pervades in many political institutions in which elected or unelected officials make collective decisions on a range of public policy issues. Group decision making has been lauded for its potential to reduce uncertainties in policy making by bringing in diverse perspectives and a wider range of information. Scholars have thus considered group decision making essentially as an undertaking of information gathering and processing. Although members involved in group decision making make different levels of individual contributions, their influence in the decisional operations and outcomes vary by “an assortment of individual and group factors, as well as environmental pressures inherent in organizational and situational specifics” (Robertson Citation1980, 169). In particular, the leadership of groups might exert a disproportionate impact as the leader is responsible for managing the intake of information, molding the decisional procedures, and shepherding the generation of outputs for decision making.

This is certainly the case for appellate courts. Composed of a small group of esteemed judicial experts, they are perhaps the quintessential collective decision-making bodies. Although the vote of the chief judge or justice on such a collegial court does not “weigh” more than the votes of the court’s other members, the attributes associated with the position allow a chief’s leadership style to shape the behavior of the court (Corley, Steigerwalt, and Ward Citation2013; Hendershot et al. Citation2013). Accordingly, leadership styles have been linked to changes in patterns of unanimity (Calderia and Zorn Citation1998; Walker, Epstein, and Dixon Citation1988), the nature of intra-court relations (Danelski Citation1989; Walker, Epstein, and Dixon Citation1988), the shaping of the prevailing deliberative style (Corley, Steigerwalt, and Ward Citation2013), and the institution’s processing efficiency (Flango, Ducat, and McKnight Citation1986). What is more, the effects of differences in the leadership styles of a chief judge or justice on a court appear to extend beyond the American case. Leadership effects on patterns of unanimity, for example, have been found on the highest courts of Canada (Johnson, Songer, and Jilani Citation2011; Ostberg, Wetstein, and Ducat Citation2004), Norway (Bentsen 2018), and, anecdotally, Australia (Smyth Citation2002).Footnote1 Smyth (Citation2002) also provides some qualitative evidence demonstrating the effect the chief justice has on the prevailing deliberative style on the Australian High Court.

Drawing on insights from a rich body of literature on the intersection between politics and gender, recent studies have investigated how judicial decision making is influenced by the different leadership styles between men and women that are more generalizable than the idiosyncratic leadership styles of individual chief justices. For example, Boyd (Citation2013) shows that women district court judges are better able to forge a compromise and reach negotiated settlements than are their male counterparts.Footnote2 Similarly, Leonard and Ross (Citation2020), examining the effect of women leaders on state supreme courts, find that when a woman is the opinion author the size of the majority coalition is larger.

The theoretical explanations provided by Boyd (Citation2013) as well as Leonard and Ross (Citation2020) integrate multiple strands of social psychology, management, and legislative politics research on the content and impact of gendered leadership (Eagly and Johannesen-Schmidt Citation2001; Eagly and Johnson Citation1990; Eagly, Makhijani, and Klonsky Citation1992; Kathlene Citation1994; Rosener Citation1990; Rosenthal Citation1997; Citation1998b). Due to the richness of this body of literature, here we highlight two characteristics of female leaders’ management styles that are most relevant to understanding the determinants of case disposition time.

Female leaders as diversity and equity promoters

One such characteristic is female leaders’ tendency to cultivate a more democratic and inclusive decision-making environment. This tendency flows from the feminine gender roles that are characterized by communal rather than agentic attributes. According to Eagly and Johannesen-Schmidt (Citation2001, 783), men are primarily associated with agentic attributes such as being independent, dominant, competitive, and controlling, whereas women are characterized as more communal such that women tend to display interpersonal, helpful, empathetic, and nurturant personalities. When applied to leadership settings, the marked contrast between communal and agentic attributes leads to the expectation that compared with men, who manifest autocratic and directive leadership tendencies, women are more likely to follow democratic and participative leadership styles (Eagly and Johannesen-Schmidt Citation2001, 787; Eagly and Johnson Citation1990; Vroom and Yetton Citation1973). A democratic and participative policy-making environment enables a fuller engagement with group members, the sharing of information by participants with varying levels of status, and an open discussion of divergent opinions.

Indeed, many studies of legislative and judicial politics find that women politicians are more democratic and egalitarian than their male counterparts. For example, analyzing legislators’ speech behavior in committee hearings, Kathlene (Citation1994, 572) finds that while male chairs adopt a hierarchical and directive approach when conducting hearings, in that they are more likely to include personal opinions and guide participants toward discussions of topics they find especially interesting, female chairs tend to “act as facilitators of the hearings,” “acknowledging all voices” from committee members and witnesses. Likewise, Rosenthal (Citation1997; Citation1998b) finds that women committee chairs in state legislatures are more likely to use inclusive leadership strategies, “involv[ing] people in the legislative process” (Rosenthal Citation1997, 594) and “invit[ing] open discussion of disagreements” (Rosenthal Citation1998a, 858). O'Brien (Citation2018) observes a similar gender gap in trial judges’ consideration of testimony provided by expert witnesses in civil rights cases. Specifically, he finds that due to feminine behavioral norms of “prioritiz[ing] community and interdependence,” female judges are more likely to admit expert witness testimony (O'Brien Citation2018, 136).

Female leaders as consensus builders

In addition to being more democratic and inclusive, another characteristic associated with women leadership styles is the adoption of an integrative strategy to foster collaboration and seek consensus among disputing parties (Jewell and Whicker Citation1994; Reingold Citation1996; Rosenthal Citation1997). In contrast to male politicians’ transactional leadership strategies that focus on individual gains and dominance, Rosenthal (Citation1998b, 4) notes that feminine, integrative leadership styles emphasize “collaboration and consensus and see politics as something more than satisfying particular interests.” In practice, it is hard to separate cultivating a democratic and inclusive decision-making environment from facilitating consensus-building among stakeholders. But in theory these two aspects of feminine leadership styles correspond to different dimensions of deliberative operations – the former emphasizing procedure-oriented objectives; the latter, results-oriented objectives.

An extensive body of political science research has found that women leaders are consensus builders and facilitators of within-group collaboration. Analyzing rates at which executive orders are issued in Latin American countries between 2000 and 2014, Shair-Rosenfield and Stoyan (Citation2018) find that female presidents are less likely to rule by issuing executive decrees, a key indicator of unilateral action, even when they enjoy high approval ratings. Women’s behavioral strengths in collaborating and building consensus are found to help women legislators “keep their sponsored bills alive through later stages of the legislative process” (Volden, Wiseman, and Wittmer Citation2013, 326). Moreover, as noted above, the presence of women leaders in courtrooms increases the chance of other justices supporting the majority opinion in US state supreme courts (Leonard and Ross Citation2020) and the likelihood as well as the speed of facilitating a compromise between disputing parties in civil rights and tort cases in the US federal district courts (Boyd Citation2013).

The female leadership style that emphasizes a more democratic and collaborative decision-making environment would have a bearing on the group deliberative dynamics in a collegial court and thus the amount of time it takes the court to render merits decisions. Specifically, when a women judge leads the court’s deliberative processes, members with a disadvantaged status – such as women, under-represented minorities, or less experienced judges – are expected to participate more actively in group discussions. Furthermore, conflicting views and opinions are more likely to be fully discussed and adopted in final decisional outputs. Taken together, then, the drawing of multiple voices and the hammering out of disagreements toward compromise are expected to prolong decision-making processes (Boyd Citation2013; Maltzman, Spriggs, and Wahlbeck Citation2000; Nie, Waltenburg, and McLauchlan Citation2019). It is not surprising that the top-down, hierarchical leadership styles are commonly associated with faster but also riskier decisions, whereas the interpersonal and consensus-oriented leadership styles are often associated with more thorough and thus more time-consuming discussions (Martin Citation2018).

In the next section, we take up the empirical task of testing our primary research hypothesis derived from our theoretical discussions – that is, decisional panels with women leaders will expend more time producing a decision.

Empirical design – the case of the Norwegian Supreme Court

The merits process and the presiding justice

We place our empirical analysis in the context of the Norwegian Supreme Court. Norway’s Supreme Court comprises 20 justices – one chief justice and 19 (associate) justices. It is a court of general appellate jurisdiction and renders final decisions on appeals from the nation’s six intermediate courts of review in civil, criminal, administrative, and constitutional law. Since 2008, and thus throughout the full time period we examine here, the Court has had near complete discretionary jurisdiction, and it makes good use of this power. In the 12 years we analyze here, an average of 2,174 appeals against judgments and orders were made to it each year, and the rotating three-member Appeals Selection Committee, the Court’s gatekeeping institution, grants full merits review to only about 10 to 15 percent of appeals against judgments annually. These are the relatively few cases the Court has identified as facilitating its twin goals of clarifying and developing the law (Grendstad et al. Citation2020).

Although the Court occasionally hears cases on their merits in Grand Chamber or en banc proceedings,Footnote3 the great bulk of appeals are randomly assigned to be heard in the Court’s two rotating five-justice panels. The assignment of justices to these decisional panels has been characterized as a “controlled lottery,” a quasi-random procedure that first ranks the 10 justices, available for service in any given week, according to seniority and then allocates the justices alternately to the two panels in order to secure the greatest range of seniority possible on each panel. Minor panel turnover occurs every week and substantial panel turnover occurs every five weeks following the Court’s internal rotation schedule of its 20 justices; as a result, the same panel typically will hear and decide only one or two cases.Footnote4

The panel’s most senior justice (or the chief justice if present) becomes the presiding justice and takes charge of the management of the case once oral arguments start.Footnote5 Reaching the status of the most senior justice on the panel typically occurs after having served around seven to ten years on the Court (Grendstad and Skiple Citation2021; Sunde Citation2015). As the title suggests, the presiding justice has a central role in an appeal’s progression through the merits process. Prior to oral arguments, the presiding justice is briefed on the legal elements and questions presented in the appeal by a justice serving on the Appeals Selection Committee. Once oral arguments begin, the presiding justice orchestrates those proceedings – summarizing for the litigants any unique elements in the panel’s composition, case-related forms of procedure, and finally introducing the parties and case – before turning the proceedings over to the appellant’s advocate.

Following oral arguments, where the justices rarely interrupt the advocates’ arguments (Meland, Westrheim, and Grendstad Citation2022), the presiding justice administers the panel’s deliberations. At the Court, sayings among the justices are that the ultimate test of a justice occurs when filling the role of presiding justice and that during the deliberations “the Court really comes alive” (Sunde Citation2015, 178). A key task of the presiding justice is first to summarize the case and to offer his or her views on the merits, thereby setting the tone for the conference’s discussion. In essence, the presiding justice presents orally the draft of what he or she recommends to be the written decision of the Court (Schei Citation2015). After 25 years on the Court, Justice Liv Gjølstad stated that as the presiding justice in deliberations, “I never cease to marvel at the importance of approach, emphasis and assessment of the context [of the case] and the strength of being many people who all contribute. The cases often have a core which it is important to refine and present as simply as possible. The work is intense while it is in progress” (Norges Høyesterett Citation2014, 32).Footnote6

Following the presiding justice and in descending order of seniority, the other justices offer their views of the case. Discussions of a case may proceed through several rounds with the presiding justice managing the extended deliberations. Deliberations end when a majority of the panel has arrived at a tentative agreement regarding an appeal’s disposition. Tentative votes are then cast, a date is loosely scheduled for the Court’s decision on the appeal to be announced, and the designated author of the Court’s opinion, already being identified by the Court’s schedule, starts writing the decision (Grendstad et al. Citation2020, 29-30, 32-34).

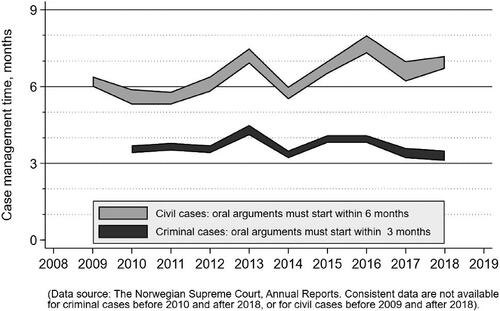

There are statutory requirements that the lower courts hand down a decision in a criminal case within three months and in a civil case within six months of the case being filed at the court,Footnote7 and the Supreme Court has set its internal rules to commence oral arguments on appeals granted review within these same time frames. Based on the Court’s annual reports, however, it is clear that the Court regularly misses the three-month and six-month goals for criminal and civil appeals, respectively (see ). To offer more concrete quantities, the average time elapsed from oral arguments to final decision is 10 days for criminal appeals and 17 days for civil appeals. not only displays where in the decision-making process our analysis takes place, it also demonstrates that the Court is under strain to deliver on its case management goals. Obviously, this strain is passed on to the presiding justice who is responsible for the case management during the decision-making process.

Analytical advantages

The Norwegian Supreme Court provides an ideal venue to examine the effect of female leadership for four main reasons. First, Norway’s commitment to egalitarianism yields sufficient observations to systematically analyze the effect of women on the Court’s deliberative processes.Footnote8 Norway has long emphasized the active participation of women in its political life. For example, over the last 30 years around 40% of the members of the parliament – The Storting – are women (Allern, Karlsen, and Narud Citation2019), and recently slightly less than half of the political parties had female party leaders. Since 1981 two women have served as prime minister for a total of 18 years: Gro Harlem Brundtland (Labour) and Erna Solberg (Conservative). Meanwhile, women of various political parties have held a significant number of government portfolios. Not surprisingly, then, the presence of women on Norway’s High Bench is notable. Currently, eight of the 20 justices (40%) are women, including the current chief justice, Toril Marie Øie. But gender issues are not uncontested. In November 2015, after the deadline for applying for the vacant position as chief justice on the Supreme Court, a newspaper quoted from a book by one of the male applicants, an associate justice on the Court, who had written that the policy goal of gender balance among judges has led to a professional deterioration among judges since well-qualified male lawyers refrained from applying (Lohne and Bjorklund Citation2015).

Second, assignment to the panels – both of the justices and the appeals – militates against any systematic differences in the decisional contexts of male and female presiding justices. The “controlled lottery” that is used to compose the merits panels helps to minimize systematic bias in panel composition across male and female presiding justices. As a result, any systematic differences between men and women presiding justices in the amount of processing time taken on a case are not likely to be a consequence of biased panel composition associated with the gender of the presiding justice. Similarly, the random assignment of appeals to the decisional panels means that there are few if any systematic differences in the types of cases for which male and female presiding justices manage the deliberative process.

Third, as we discuss in more detail below, the complexity of a case certainly affects the time necessary for a collegial court to render a final decision on its merits. In Norway, the Supreme Court adjusts the time for oral arguments according to the complexity of the case. Scholars have demonstrated that the amount of time the Court sets for oral arguments is a reliable and valid ex ante measure of case complexity for the Norwegian Supreme Court (Bentsen et al. Citation2021). Our use of this measure helps to ensure the causal order of the relationships we are modeling. To put it concretely, our use of this ex ante measure of case complexity allows us to test the effect of case complexity on the time to render the merits decision rather than whether aspects of the merits decision affect complexity (Goelzhauser, Kassow, and Rice Citation2021). Other, more conventional measures of complexity use elements of the merits decision itself (Maltzman, Spriggs, and Wahlbeck Citation2000; Maltzman and Wahlbeck Citation1996) to measure complexity and thus weaken any causal claims regarding the effect of complexity on the decision (Bentsen et al. Citation2021).

Finally, by locating our empirical analysis in the Norwegian Supreme Court, we are able to transport the study of the effect of leadership style on the operations and outputs of judicial institutions beyond the US context (Boyd Citation2013; Leonard and Ross Citation2020; Norris and Tankersley Citation2018). This adds to the generalizable power of our results.

Data and measures

Dependent variable

We analyze an original data set of all 1,552 decisions decided between 2008 and 2019 by the Norwegian Supreme Court in panels of five justices.Footnote9 Information has been collected from the Supreme Court itself and the comprehensive legal database Lovdata.Footnote10 The dependent variable in our analysis is the duration of case disposition time, measured by the number of days between the date of oral argument and the date when a final decision was announced. If oral arguments last for more than one day, the first day of oral arguments is used as the start date. As noted above, we conceptualize the duration of case disposition time as the amount of effort a collegial court expends deciding the merits of cases. Because the High Court’s deliberations are held in empty chambers and are far from the public’s gaze, the duration of case disposition time serves as an observable indicator for analyzing the deliberative dynamics in a collegial court.

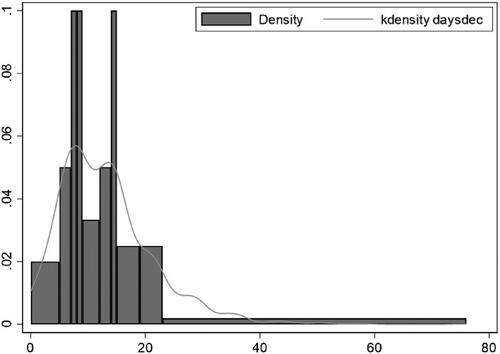

presents an equal probability histogram plot of the dependent variable (Cox Citation2004). As shown in this figure, there is substantial variation in the duration of case disposition time on the Norwegian Supreme Court. It takes the Court on average 14 days to render a final decision. The standard deviation of our dependent variable is 8.3. Half of the cases were decided within 12 days, and 97% of the cases were decided within one month. Only a very small fraction of the cases stays in the Court system for an extended period of time, up to two and one-half months.

Independent variable

The main independent variable we use to explain the duration of case disposition is whether the presiding justice on a panel is a woman. We identify the sex of justices based on their names and official biographical information. The variable female presiding justice takes the value of 1 if a presiding justice on a panel is female, and 0 otherwise. Eight of the 15 female justices in our data had experience as presiding justice (a similar proportion to that of males: 14 out of 29). Given the quasi-randomness of case allocation and panel composition, female leadership is not assigned to manage cases and panels that inherently require more or less time to reach a merits decision. In our sample, 556, or 36 percent, of the cases are decided in a panel with a female presiding justice. From 2008 to 2019, 35.8 percent of the presiding justices were female, an average that generally matches the overall presence of women serving as Supreme Court justices.

Controls

We consider a battery of controls.Footnote11 Perhaps one of the most important characteristics of the decisional environment to affect the amount of processing time is the complexity of the case itself (Christensen and Szmer Citation2012; Nie, Waltenburg, and McLauchlan Citation2019). Complex cases are unlikely to present an obvious legal solution. They provide opportunities for the justices’ preferences to enter into the decisional process. With those preferences, differences among the justices are likely to arise, agreement is more difficult to achieve, and consequently, more time is needed to render a final decision (Baum Citation1997; Grendstad, Shaffer, and Waltenburg Citation2015, 66). To operationalize case complexity, we use the amount of time the Court sets for oral arguments. As discussed above, one unique institutional feature of the Norwegian Supreme Court is that it anticipates the difficulty in resolving legal disputes in all cases and allocates the time for oral arguments accordingly. Bentsen et al.'s (Citation2021) model shows that the amount of time set for oral arguments on the Norwegian Supreme Court is indeed associated with a range of case characteristics that tap into legal difficulty, including criminal and civil cases, and thus demonstrates the validity of using time for oral arguments as an ex ante measure of case complexity. Our measure of case complexity also provides an extra control for the non-perfect randomness in panel compositions. Hence, cases are comparable for male and female presiding justices.

Apart from case characteristics that would engender disagreements among justices, we control for levels of heterogeneity among justices (Maltzman, Spriggs, and Wahlbeck Citation2000; Nie, Waltenburg, and McLauchlan Citation2019). A more heterogenous group of justices means a more divergent set of views and thus, more effort and time for the presiding justice to make accommodations. One direct measure of opinion heterogeneity is the number of voices on a panel. We counted the number of justices who wrote dissents or concurrences in a case and added the count to the justice who voiced the court’s majority opinion. Moreover, we account for justices’ experience measured by the number of years a justice has served on the high bench. Specifically, we compute the average years of judicial experience and heterogeneity (i.e., the standard deviation) of judicial experience on a panel.

Additionally, we consider a set of identity or role-based aspects of group heterogeneity. First, based on the justices’ former careers, we use two variables: the number of former law professors and the number of former lawyers having worked in the Government’s prestigious Legislation Department at the Ministry of Justice. Law professors engage more easily in disputatious deliberations (Bentsen 2018; Corley, Steigerwalt, and Ward Citation2013), judicial activism (Kinander Citation2002; Robberstad Citation2016) and may contribute to longer decisional time by taking things into account that are “irrelevant” (Arold Citation2010, 64). Since lawyers at the Legislation Department decide “what the law is” (Skarpnes Citation1986, 195), justices recruited from this division of the Ministry of Justice may well continue to take time explaining to the other justices what the law means when deciding cases on the Court. Second, the Supreme Court temporarily hires interim justices to fill short-term vacancies, sometimes considered a type of audition (Grendstad, Shaffer, and Waltenburg Citation2015). Consequently, we include a variable that notes the presence of interim justice on the panel to test whether less experienced justices – the low justices on the totem pole – slow down time to decision.

Lastly, we control for the idiosyncratic management styles of chief justices and any docket-size pressures that might constrain the Court’s institutional capability. Research has found that chief justices can have a profound impact on shaping the overall operations of the Court. Our data set, covering the years 2008 to 2019, spans the bulk of the Tore Schei Court (he was chief justice from 2002 to February 2016), and all of the Toril Marie Øie Court for which we have data available (she became chief justice in March 2016). Schei had a penchant for efficiency and a difficulty with hiding his impatience (Gjølstad and Tjomsland Citation2016). Shortly after being tapped as chief justice, he improved case processing time, reduced backlogs and turned the Court into a “well-oiled machine” (Sunde Citation2015, 338). Toril Marie Øie’s fewer years as chief justice have provided less data with which to draw a clear leadership profile. Based on her twelve years as associate justice (NTB Citation2016; Sunde Citation2015), prognostications would include her working for a socially inclusive Court and having a knack for building coalitions from a center-based position of law. Thus, we include Chief term, a binary variable to control for their leadership, 1 for Mr. Schei and 0 for Ms. Øie. To measure the Court’s workload constraints, we follow Cauthen and Latzer (Citation2008) and use the log amount of appeals for a given Court term. Our variables are summarized in .

Table 1. Summary statistics.

Methods and results

Due to the duration nature of our dependent variable, we follow conventional modeling practices (Boyd Citation2013) and use the Cox proportional hazards model to analyze the effect of female presiding justice on the case disposition time on the Norwegian Supreme Court (Cox Citation1972). The duration models we specify examine the hazard rate of a case being rendered as a final decision, or the likelihood of a case leaving the Court system given that all other cases stay in it. Regarding the interpretation of regression coefficients in our models, a positive (negative) coefficient indicates that as the independent variable increases, the duration of a case being decided becomes shorter (longer), or the hazard of a case being decided increases (decreases). In Cox proportional hazards models, it is necessary to test the proportional hazards assumption for each independent variable, holding that the effect of an independent variable on the hazard is constant over time. If the proportional hazards assumption is violated, we then interact the culpable independent variable with the natural logarithm of case disposition time (Box-Steffensmeier and Jones Citation2004). Finally, we adjust for the clustering of cases at the Court-term level.

reports our regression results. We adopt a stepwise modeling strategy. Model 1 is the baseline model in which we include only the presiding female justice variable. In Model 2, we re-run the analysis with the addition of case complexity. In Model 3, we include an additional set of variables that measure panel-level heterogeneity, including opinion heterogeneity, the average judicial experience, the heterogeneity of judicial experience, the number of former law professors, the number of former lawyers at the Government’s Legislation Department, and the presence of interim justice. In Model 4, we further account for the two different chief terms and the Court’s workload to complete the joint analysis of our key independent variable and all the controls. Across the four different model specifications, regression results are largely consistent. Thus, we rely on our complete model, or Model 4, to interpret our results.

Table 2. Regression results from models of the duration of case disposition time.

First, the primary hypothesis we test is that the presence of female leadership promotes more thorough and thus longer group deliberations. Findings from our analyses lend partial support to this hypothesis. Specifically, as indicated by the negative coefficient on female presiding justice, the effect of having a female presiding justice decreases the hazard of a case being rendered a final decision, or increases the duration of case disposition time. However, this negative effect on the hazard of a case being decided changes over time, as demonstrated by the positive coefficient associated with the time-varying component of female presiding justice.

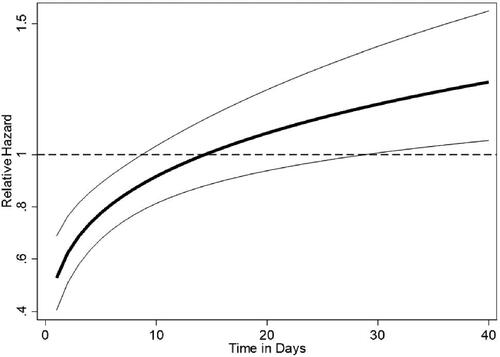

To aid in interpreting the substantive effect of female presiding justice, in we plot the changing effects of female presiding justice on the Court’s adjudicatory speed over time, holding all other variables constant. Specifically, plots the relative hazard, or the change in hazard ratio when the sex of the presiding justice switches from male to female (Licht Citation2011). As shown in this figure, cases decided by panels with female presiding justices were initially 47% less likely to be decided earlier than those headed by male justices. The positive effect of female presiding justice on the duration of case disposition time maintains from day 1 through day 8, and then becomes insignificant on and after day 9. Not until day 28 does the effect of female presiding justice switch sign from negative to positive, indicating that for those particular cases, panels presided over by a female justice were actually decided more quickly. It bears noting, however, that in our sample, fewer than five percent of the cases were decided in more than 28 days, while one third of the cases were decided within eight days. Thus, we concede that in approximately two-thirds of all cases in our data set a panel with a female presiding justice was no more likely to result in longer decisional time than those presided over by a male justice.

Figure 3. Relative hazard of female presiding justice.

Note. The solid line represent the relative hazard of switching from male presiding justice (=0) to female presiding justice (=1). Thin lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. The effect of female presiding justice on case disposition time is insignificant when the confidence intervals cover the value of 1.

The above findings generally show that the gender of presiding justices in a collegial court makes an important difference in group deliberative dynamics, as evidenced by the amount of time it takes the court to decide a case. But the prolonging effect of female leadership is less persistent than we expected, suggesting that institutional pressures to resolve cases eventually overwhelm leadership styles that emphasize integration, collaboration, and consensus. Based upon these findings, it appears that after just over a week, the leadership styles associated with men and women do not exert systematic differences in the processing time taken to resolve a case.

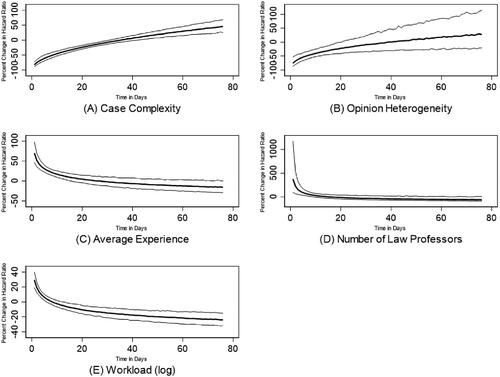

Next, turning our attention to the controls, we find that the coefficient for case complexity is negative and statistically significant. Consistent with prior research on the US Courts of Appeals (Cauthen and Latzer Citation2008; Christensen and Szmer Citation2012), this finding suggests that it takes more time for the Norwegian Supreme Court to render a final decision on more difficult cases. But similar to the effect of female presiding justice, the effect of case complexity on the Court’s decisional time wears off as time progresses. Panel (A) in charts the percentage changes in hazard ratios when we move from the mean to one standard deviation above the mean in case complexity (Licht Citation2011). Substantively, compared to cases with average levels of complexity, more complex cases are associated with an 82% decrease in the probability of being decided. The positive impact of case complexity on the duration of case disposition time wears off very slowly and becomes insignificant on day 31. However, case complexity starts to exert a negative impact on adjudicatory speed after day 42, suggesting that after an extended period of time allocated to panel deliberation, justices as a group quicken their speed of rendering a final decision.

Figure 4. First difference summary of the effects of controls with time-varying components.

Note. Solid lines represent the median change based on a random draw of 1000 estimates from Model 4 in , and thin lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. For continuous variables including case complexity, average experience, and workload (log), the plots depict the first difference for a move from the mean to one standard deviation above the mean. For categorical variables including opinion heterogeneity and the number of law professors, the plots depict the first difference for a move from the minimum to the maximum. The effect of controls is statistically insignificant when confidence intervals include zero.

We also find that higher levels of opinion heterogeneity increase the duration of the Court’s decisional time, although this effect wanes as time progresses. Panel (B) in provides a graphical summary of the percent change in hazard ratio when we shift the value of opinion heterogeneity from the minimum to the maximum. Specifically, the likelihood of a case being decided decreases by 75% initially. And the prolonging effect of opinion heterogeneity on decisional time maintains through day 19 and then becomes insignificant afterwards.

Likewise, judicial experience has a significant bearing on the duration of case disposition time. The positive coefficient for average judicial experience indicates that in a panel composed with more experienced justices, the Court’s adjudicatory speed is faster, despite the fact that such an effect holds for only about two weeks (see Panel C in ). Relatedly, controlling for the mean judicial experience on a panel, we do not find a significant effect of the experiential heterogeneity on the speed of decision-making on the Court. For other dimensions of panel-level heterogeneity, only the number of former law professors attains conventional statistical significance. As shown in Panel (D) in , the shift from having no law professor to having four law professors on a panel results in a striking 372 percent increase in the probability of a case being decided at the initial period of time. After nine days, this effect no longer maintains. Contrary to our expectations, then, the presence of law professors speeds up case disposition time, at least initially. Perhaps law professors, given their professional training, are able to dispose of the legally “easy” cases more quickly than their counterparts.

Although Toril Marie Øie has served as chief justice for close to four years of the twelve years included in our current data set, we find that the time to decision during those four Court sessions was greater than that recorded for the Court during Tore Schei’s tenure as chief justice. While the gender of the chief justice may have influenced the number of days spent on a case, it appears likely that gender is conflated with the differing judicial contexts during Øie and Schei’s terms as chief justice. There is considerable evidence that Chief Justice Schei was confronted with a perceived need to process a substantial backlog of cases (Grendstad et al. Citation2020). Efficiency, not more time-consuming deliberation, became a priority. Given Mr. Schei’s reputed impatience and penchant for efficiency, the backlog of cases decided during his Court were adjudicated more quickly, as reflected in the positive coefficient associated with the chief-term variable. In other words, the more cases to be decided, the faster the justices decided them. Then, as time progressed and the Court faced fewer appeals, justices were no longer rushed to decide cases (see Panel E in ).

Alternative explanation

The preceding analysis has shown that the presence of women presiding justices has a prolonging, albeit short-term, effect on the duration of case disposition time. We posited that the theoretical rationale underlying this effect is women leaders’ inclination to promote inclusivity and consensus. But an alternative, certainly less pleasant, explanation is that women presiding justices are less adept at managing the group deliberation process than their male counterparts do, perhaps due to their lack of experience, decisiveness, and/or diminished self-confidence. Here, we provide additional qualitative and quantitative evidence to further support our posited explanation.

Qualitatively, we revisited our anonymous deep-background interviews with former and current justices on the Court on our ongoing research project and, moreover, we approached two former justices, specifically probing them on their views on the nature of any differences between male and female presiding justices. While it has been recognized that efficiency is an overarching concern in the adjudication process, the consensus among all was that male and female presiding justices do not show systematic differences in administrative efficiencies. Aside from efficiency concerns, a willingness to include or accommodate multiple positions has been identified to affect the time-to-decision. In particular, in support of our preferred explanation, several justices noted that women justices appear to be more empathetic and open to different positions and conclusions.

Quantitatively, we conduct additional analyses to address the concern that male and female presiding justices might not be equipped with the same level of such leadership qualities as confidence and decisiveness. Because these attributes are hard to observe and thus operationalize in our empirical setting, we use certain background experiences as proxies. By using this approach, we assume that prior legal experiences external and/or internal to the Court play an important role in nurturing and improving leadership skills for a presiding justice. We rely on three variables in our data set that directly measure justices’ prior legal careers and their tenure on the Court and use them to augment our full model specified in the preceding section. Specifically, for a presiding justice in each case, we include in the augmented model whether he or she is a former law professor, whether he or she is a former staff member having worked in the government’s Legislation Department, and the number of years he or she have served on the Court. Reassuringly, none of these variables attain statistical significance at the conventional .05 level.Footnote12 Taken together, the additional qualitative and quantitative evidence we provide appear to be more consistent with the gendered leadership explanation we articulated.

Discussion and conclusion

A large body of literature has analyzed whether and how the distinct voices and perspectives of women judges and lawyers influence case outcomes and judicial outputs. In this article we push the boundaries of inquiry in the literature by exploring how gendered leadership affects the decisional process in collegial courts, something that remains an inherent puzzle in light of the formative role group deliberations play in producing merits decisions. Considering the closed-door nature of judicial deliberations, we analyze the duration of case disposition time, an important indicator of the levels of bargaining and compromise among judges during case deliberations in collegial courts (Nie, Waltenburg, and McLauchlan Citation2019). Focusing on female leaders’ predisposition to promote a more democratic and consensus-driven decision-making environment, we hypothesize that it takes more time for a collegial court to decide a case with the presence of a female leader. We place our hypothesis testing in the context of the Norwegian Supreme Court due to the substantial variation in female leadership across panels and years on the Court. Findings from our analysis show that cases with female presiding justices are indeed decided more slowly but only for slightly more than one week, the duration for which about one-third of the cases in our data set were disposed of. For the remaining cases that were not yet removed from the Court’s docket, the difference between male and female leadership styles appears to matter little.

Why does the presence of female presiding justices have only a short-term impact on the number days to decision? Drawing on insights from a long line of research on institutionalism – “formal or informal procedures, routines, norms and conventions embedded in the organizational structure of the polity” (Hall and Taylor Citation1996, 938) - we argue that the Court’s general and deeply established procedures exert a major influence on the manner in which deliberation takes place, irrespective of the presiding justice’s gender. These institutional rules and practices are not simply “mirrors of social forces” (March and Olsen Citation1983, 739) but an autonomous force unto themselves that constrains the behavior or preferences of individual justices.

Echoing March and Olsen’s point that “theories of political structure assume action is the fulfillment of duties and obligations” (1984, 741), we identify two institutional realities that could limit the impact of female leadership on the duration of case disposition time. The first reality is the volume of cases the Supreme Court must address. It is not too great a logical stretch to presume that the greater the number of cases, the more likely institutional pressures would mount that they be decided more quickly. Indeed, that Chief Justice Schei moved diligently through the backlog the Court confronted is evidenced by the volume of cases expedited during his tenure. In the first six years of the period under study here, the number of cases ranged from 126 to 171, averaging 147 cases per year. During the last six years the comparable figures range from 103 to 121, averaging 112 cases per year – a nearly 25 percent drop in the number of cases needing to be decided. With a heavy caseload, time to decision appears to have been reduced. Indeed, the results reported above indicate that a high workload decreases the time to decision. However, in a manner similar to that observed for the gender of the presiding justice, the effect of caseload is time-varying. After a certain number of days to decision, with a smaller volume of cases still staying in the Court, it takes more time for the five-member panel to reach a decision.

The second important institutional reality is the Court’s self-imposed obligation to dispose of criminal and civil appeals within certain time windows. Although in recent years, the Court has regularly failed to dispose of appeals within its specified time frame (see ), that this institutional duty exists eventually overwhelms a choice-based leadership style that emphasizes consensus and collaboration. To put it simply, although female presiding justices may want to include all the members of the decisional panel in the final merits opinion, the combination of a running clock and an institutional expectation that an appeal will be resolved within a specified amount of time (not to mention the steady drumbeat of new appeals arriving in the Court) eventually have their way. The practical need to clear cases constrains any ongoing emphasis on collaboration and integration.

In closing, we should note that institutional procedures are not impervious to change because political or social conditions can lay the groundwork for their alterations. For example, in the post-World War II period, no law school professor was permanently appointed until Carsten Smith became the chief justice in 1991.Footnote13 Today, might the significant presence of former law professors result in changes in the decision-making process over the last three decades? Apparently, this matters for decisions rendered over longer time periods. Or perhaps appointing justices with quite diverse opinions would inflate the time to decision. With specific reference to our central hypothesis regarding the effect of female presiding justices, entering the new millennium, women were being appointed to the Supreme Court in ever increasing numbers. After racking up high levels of seniority, their leadership may have shifted the case management style such that all justices, female and male alike, now have converged to a more shared perspective. If such a transformation has taken place, it remains incomplete given that we find a significant impact of the gender of the presiding justice on the time to decision.

Acknowledgments

An early version of this paper was presented at the workshop The Politics of Law and Courts at the 2021 Nordic Political Science Association virtual conference 10-13 August, Reykjavik, Iceland. We especially thank Johan Lindholm and Øyvind Stiansen for useful comments. We also thank Jørn Øyrehagen Sunde and Christopher Haugli Sørensen for providing information to our inquires. And we thank two anonymous referees for critical comments on and earlier version of this article. Replication datafiles can be found at: https://doi.org/10.18710/5NP4DG

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 Using more sophisticated regression procedures, however, Smyth finds that the “variations in the level of dissenting and single judgments under different Chief Justices are not statistically significant” (2002, 261).

2 And paradoxically do so more quickly.

3 Grand Chamber (including the chief justice and 10 randomly drawn justices) and en banc hearings occur when an appeal is “deemed of special importance” or concerns an “extraordinary case,” respectively (The Court Act, Section 5).

4 An empirical examination of the “controlled lottery” process indicates that only 22.5 percent of the five-justice panels are composed in complete accordance with the Court’s stated procedures, see Grendstad and Skiple (Citation2021). Some of the deviations are attributed to justices having opinion-writing assignments, which may relieve the justice from serving on the next panel, and conflicts of interest, according to Chief Justice Toril Marie Øie, qtd. in Letvik (Citation2021).

5 The Court Act, Section 4 and Section 123.

6 Translated by the authors.

7 Bills before the Storting (various years, e.g., St.prp.nr.1 (2007-2008), page 22). Also see the Criminal Procedure Act, Section 328 and the Dispute Act, sections 9-4 and 11-6.

8 Norway is frequently identified as the most democratic nation in the world (https://freedomhouse.org/country/norway/freedom-world/2020; last accessed June 23, 2021).

9 We exclude marginal types of decisions, including resolutions and reassessments, which account for the reduction from 1,576 decisions to 1,552 decisions, a reduction amounting to about 1.5% of all decisions. Among the 1,552 decisions, nine observations are removed from our event history analysis (see details below) because they were decided on the same day of the oral argument.

11 We opt for excluding a justice’s ideology for both theoretical and analytical reasons. Theoretically, there is little prior reason to expect that a presiding justice’s ideology would affect his or her quality of leadership, leadership style, and thus the time-to-decision. Analytically, the studies that have found that ideology affects the decisional behavior of Norway’s Supreme Court justices have observed that effect on economic cases pitting private interests against the government over a longer time series than we analyze here (see, for example, Grendstad, Shaffer, and Waltenburg Citation2015; Skiple et al. Citation2016). Additionally, a more recent and rigorous study of the decisional behavior of Norwegian Supreme Court justices found that deference to the public party rather than ideology was systematically associated with the justices’ voting cleavages (Skiple, Bentsen, and Hanretty Citation2020). And finally, the measure of ideology that has been used is an indirect proxy for preferences – the nature of the appointing government. That measure is further attenuated by the appointment process that has been in place since 2002. This process uses an independent Judicial Appointment Board, which vets and ranks the candidates for a vacancy. The Board makes a recommendation to the Ministry of Justice, and appointment by the King in council is eventually made.

12 Based on the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and the Akaike information criterion (AIC), the full model we specified in the preceding section is preferred. See results in in the Appendix.

13 A number of law professors had been temporarily appointed and reappointed to the Court as interim justices.

References

- Allern, Elin H., Rune Karlsen, and Hanne M. Narud. 2019. “Kvinnerepresentasjon og Parlamentariske Posisjoner [the Representation of Women and Parliamentarian Positions].” Tidsskrift for Kjønnsforskning 43 (3):230–45. doi:10.18261/issn.1891-1781-2019-03-07.

- Arold, Nina-Louisa. 2010. “The Melting Pot or the Salad Bowl Revisited. Rendezvouz of Legal Cultures at the European Court of Human Rights.” In Rendezvous of European Legal Cultures, edited by Jørn Ø. Sunde and Knut E. Skodvin. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

- Atkins, Burton M. 1991. “Party Capability Theory as an Explanation for Intervention Behavior in the English Court of Appeal.” American Journal of Political Science 35 (4):881–903. doi: 10.2307/2111498.

- Baum, Larry. 1997. The Puzzle of Judicial Behavior. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Bentsen, Henrik L. 2018. “Court Leadership, Agenda Transformation, and Judicial Dissent: A European Case of a "Mysterious Demise of Consensual Norms.” Journal of Law and Courts 6 (1):189–213. doi: 10.1086/695555.

- Bentsen, Henrik L., Gunnar Grendstad, William R. Shaffer, and Eric N. Waltenburg. 2021. “A High Court Plays the Accordion: Validating Ex Ante Case Complexity on Oral Arguments.” Justice System Journal 42 (2):130–49. doi: 10.1080/0098261X.2021.1881667.

- Bielen, Samantha, and Wim Marneffe. 2017. “Are Courts to Blame for Delays in Belgian Civil Procedures?: A Decomposition of Case Duration.” Justice System Journal 38 (4):399–420. doi: 10.1080/0098261X.2017.1331772.

- Box-Steffensmeier, Janet M., and Bradford S. Jones. 2004. Event History Modeling: A Guide for Social Scientists. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Boyd, Christina L. 2013. “She'll Settle It?” Journal of Law and Courts 1 (2):193–219. doi: 10.1086/670723.

- Boyd, Christina L. 2016. “Representation on the Courts? The Effects of Trial Judges’ Sex and Race.” Political Research Quarterly 69 (4):788–99. doi: 10.1177/1065912916663653.

- Boyd, Christina L., Lee Epstein, and Andrew D. Martin. 2010. “Untangling the Causal Effects of Sex on Judging.” American Journal of Political Science 54 (2):389–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00437.x.

- Calderia, Gregory A., and Christopher J. W. Zorn. 1998. “Of Time and Consensual Norms in the Supreme Court.” American Journal of Political Science 42 (3):874–902. doi: 10.2307/2991733.

- Cauthen, James N. G, and Barry Latzer. 2008. “Why so Long? Explaining Processing Time in Capital Appeals.” Justice System Journal 29 (3):298–312.

- Christensen, Robert K, and John Szmer. 2012. “Examining the Efficiency of the U.S. Courts of Appeals: Pathologies and Prescriptions.” International Review of Law and Economics 32 (1):30–7. doi: 10.1016/j.irle.2011.12.004.

- Corley, Pamela C., Amy Steigerwalt, and Artemus Ward. 2013. The Puzzle of Unanimity: Consensus on the United States Supreme Court. Stanford, CA: Stanford Law Books.

- Cox, D. R. 1972. “Regression Models and Life Tables.” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological) 34 (2):187–220. doi: 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1972.tb00899.x.

- Cox, Nicholas J. 2004. “Speaking Stata: Graphing Distributions.” The Stata Journal: Promoting Communications on Statistics and Stata 4 (1):66–88. doi: 10.1177/1536867X0100400106.

- Danelski, David J. 1989. “The Influence of the Chief Justice in the Decisional Process of the Supreme Court.” In American Court Systems, edited by G. Sheldon and A. Sarat. New York: Longman.

- Eagly, Alice H, and Mary C. Johannesen-Schmidt. 2001. “The Leadership Styles of Women and Men.” Journal of Social Issues 57 (4):781–97. doi: 10.1111/0022-4537.00241.

- Eagly, Alice H, and Blair T. Johnson. 1990. “Gender and Leadership Style: A Meta-Analysis.” Psychological Bulletin 108 (2):233–56. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.2.233.

- Eagly, Alice H., Mona G. Makhijani, and Bruce G. Klonsky. 1992. “Gender and the Evaluation of Leaders: A Meta-Analysis.” Psychological Bulletin 111 (1):3–22. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.1.3.

- Flango, Victor E., Craig R. Ducat, and R. N. McKnight. 1986. “Measuring Leadership through Opinion Assignments in Two State Supreme Courts.” In Judicial Conflict and Consensus: Behavioral Studies of American Appellate Courts, edited by S. Goldman and C. M. Lamb. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky.

- Gjølstad, Liv, and Steinar Tjomsland. 2016. “Tore Schei 70 år.” In Rettsavklaring og Rettsutvikling. Festskrift Til Tore Schei, edited by Magnus Matningsdal, Jens E. A. Skoghøy, Toril M. Øie and Gunnar Bergby. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Goelzhauser, Greg, Benjamin J. Kassow, and Douglas Rice. 2021. “Measuring Supreme Court Case Complexity.” The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 38 (1):92–118. doi: 10.1093/jleo/ewaa027.

- Grendstad, Gunnar, William R. Shaffer, Jørn Ø. Sunde, and Eric N. Waltneburg. 2020. Proactive and Powerful: Law Clerks and the Institutionalization of the Norwegian Supreme Court. The Hague: Eleven International Publishing.

- Grendstad, Gunnar, William R. Shaffer, and Eric N. Waltenburg. 2015. Policy Making in an Independent Judiciary: The Norwegian Supreme Court, Colchester. Colchester, UK: ECPR Press.

- Grendstad, Gunnar, and Jon K. Skiple. 2021. “Tilfeldighetsprinsippet i Norges Høyesterett: Fordelingen av Saker Mellom Dommere og Fordelingen av Dommere på Avdeling. En Empirisk Undersøkelse.” Tidsskrift for Rettsvitenskap 134 (1):46–76. doi:10.18261/issn.1504-3096-2021-01-02.

- Haire, Susan B., Laura P. Moyer, and Shawn Treier. 2013. “Diversity, Deliberation, and Judicial Opinion Writing.” Journal of Law and Courts 1 (2):303–30. doi: 10.1086/670724.

- Hall, Peter A, and Rosemary C. Taylor. 1996. “Political Science and the Three New Institutionalisms.” Political Studies 44 (5):936–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.1996.tb00343.x.

- Hendershot, Marcus E., Mark S. Hurwitz, Drew N. Lanier, and Richard L. Pacelle. 2013. “Dissensual Decision Making.” Political Research Quarterly 66 (2):467–81. doi: 10.1177/1065912912436880.

- Jewell, M., and M. L. Whicker. 1994. Legislative Leadership in the American States. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Johnson, Susan W., Donald R. Songer, and Nadia A. Jilani. 2011. “Judge Gender, Critical Mass, and Decision Making in the Appellate Courts of Canada.” Journal of Women, Politics & Policy 32 (3):237–60. doi: 10.1080/1554477X.2011.589293.

- Kathlene, Lyn. 1994. “Power and Influence in State Legislative Policymaking: The Interaction of Gender and Position in Committee Hearing Debates.” American Political Science Review 88 (3):560–76. doi: 10.2307/2944795.

- Kinander, Morten. 2002. “Trenger Man Egentlig Reelle Hensyn.” Lov og Rett 41 (4):224–41. doi:10.18261/ISSN1504-3061-2002-04-03.

- Leonard, Meghan E., and Joseph V. Ross. 2020. “Gender Diversity, Women’s Leadership, and Consensus in State Supreme Courts.” Journal of Women, Politics & Policy 41 (3):278–302. doi: 10.1080/1554477X.2019.1698213.

- Letvik, Tore. 2021. “Forskere Stiller Spørsmål Ved Fordeling av Saker i Høyesterett.” Juristen. https://juristen.no/nyheter/2021/06/forskere-stiller-sp%C3%B8rsm%C3%A5l-ved-fordeling-av-saker-i-h%C3%B8yesterett (Accessed July 14, 2022).

- Licht, Amanda A. 2011. “Change Comes with Time: Substantive Interpretation of Nonproportional Hazards in Event History Analysis.” Political Analysis 19 (2):227–43. doi: 10.1093/pan/mpq039.

- Lohne, Lone, and Ingrid Bjorklund. 2015. “Mener Kjønnskvotering Senker Nivået.” Dagens Naeringsliv. November 28, pp. 1,6-7.

- Maltzman, Forrest, James F. Spriggs II, and Paul J. Wahlbeck. 2000. Crafting Law on the Supreme Court. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Maltzman, Forrest, and Paul J. Wahlbeck. 1996. “May It Please the Chief? Opinion Assignments in the Rehnquist Court.” American Journal of Political Science 40 (2):421–43. doi:10.2307/2111631.

- March, James G., and Johan P. Olsen. 1983. “The New Institutionalism: Organizational Factors in Political Life.” American Political Science Review 78 (3):734–49. doi: 10.2307/1961840.

- Martin, James R. Jr. 2018. “Consensus Builders? The Influence of Female Cabinet Ministers on the Duration of Parliamentary Governments.” Politics & Policy 46 (4):630–52. doi: 10.1111/polp.12266.

- Meland, Ida M. S., Welat A. Westrheim, and Gunnar Grendstad. 2022. “Spørsmål og Dialog i Muntlige Forhandlinger i Norges Høyesterett.” Lov og Rett 61 (2):117–28. doi:10.18261/lor.61.2.5.

- Moyer, Laura P., and Susan Haire. 2015. “Trailblazers and Those That Followed: Personal Experiences, Gender, and Judicial Empathy.” Law & Society Review 49 (3):665–89. doi: 10.1111/lasr.12150.

- Moyer, Laura P., and Holley Tankersley. 2012. “Judicial Innovation and Sexual Harassment Doctrine in the U.S. Courts of Appeals.” Political Research Quarterly 65 (4):784–98. doi: 10.1177/1065912911411097.

- Nie, Mintao, Eric N. Waltenburg, and William P. McLauchlan. 2019. “Time Chart of the Justices Revisited: An Analysis of the Influences on the Time It Takes to Compose the Majority Opinion on the U.S. Supreme Court.” Justice System Journal 40 (1):54–75. doi: 10.1080/0098261X.2019.1596044.

- Norges, Høyesterett. 2014. Høyesteretts Årsmelding 2013. Oslo.

- Norris, Mikel, and Holley Tankersley. 2018. “Women Rule: Gendered Leadership and State Supreme Court Chief Justice Selection.” Journal of Women, Politics & Policy 39 (1):104–25. doi: 10.1080/1554477X.2017.1375789.

- NTB. 2016. “Øie er Pragmatisk og i Sentrum, Men Ikke Ufarlig.” February 19.

- O'Brien, Timothy L. 2018. “Gender, Expert Advice, and Judicial Gatekeeping in the United States.” Social Science Research 72:134–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2018.02.011.

- Ostberg, C. L., Matthew E. Wetstein, and Craig R. Ducat. 2004. “Leaders, Followers, and Outsiders: Task and Social Leadership on the Canadian Supreme Court in the Early 'Nineties.” Polity 36 (3):505–28. doi: 10.1086/POLv36n3ms3235388.

- Palmer, Jan, and Saul Brenner. 1990. “Determinants of the Amount of Time Taken by the Vinson Court to Process Its Full-Opinion Cases.” Journal of Supreme Court History 15:142–51.

- Rathjen, Gregory J. 1980. “Time and Dissension on the United States Supreme Court.” Ohio Northern University Law Review 7:227–58.

- Reingold, Beth. 1996. “Conflict and Cooperation: Legislative Strategies and Concepts of Power among Female and Male State Legislators.” The Journal of Politics 58 (2):464–84. doi: 10.2307/2960235.

- Robberstad, Anna. 2016. “Viljen Til å Skape Lov og Grunnlov.” Lov og Rett 55 (1):49–64. doi: 10.18261/issn.1504-3061-2016-01-04.

- Robertson, Roby D. 1980. “Small Group Decision Making: The Uncertain Role of Information in Reducing Uncertainty.” Political Behavior 2 (2):163–88. doi: 10.1007/BF00989889.

- Rosener, Judy B. 1990. “Ways Women Lead.” Harvard Business Review 68 (6):119–25.

- Rosenthal, Cindy S. 1997. “A View of Their Own: Women's Committee Leadership Styles and State Legislatures.” Policy Studies Journal 25 (4):585–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0072.1997.tb00043.x.

- Rosenthal, Cindy S. 1998a. “Determinants of Collaborative Leadership: Civic Engagement, Gender or Organizational Norms?” Political Research Quarterly 51 (4):847–68. doi: 10.1177/106591299805100401.

- Rosenthal, Cindy S. 1998b. When Women Lead: Integrative Leadership in State Legislatures. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Schei, Tore. 2015. “Norges Høyesterett Ved 200-Årsjubileet.” In Lov, Sannhet, Rett. Norges Høyesterett 200 år, edited by Tore Schei, Jens E. A. Skoghøy, and Toril M. Øie, 1–42. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Shair-Rosenfield, Sarah, and Alissandra T. Stoyan. 2018. “Gendered Opportunities and Constraints: How Executive Sex and Approval Influence Executive Decree Issuance.” Political Research Quarterly 71 (3):586–99. doi: 10.1177/1065912917750279.

- Skarpnes, Oluf. 1986. “Minner Fra Lovavlelingen.” In Festskrift Lovavdelingen - 100 år, 1885-1985, edited by Helge O. Bugge, Kirsti Coward, and Stein Rognlien. Oslo: Universeitsforlaget.

- Skiple, Jon K., Henrik L. Bentsen, and Chris Hanretty. 2020. “The Government Deference Dimension of Judicial Decision Making: Evidence from the Supreme Court of Norway.” Scandinavian Political Studies 43 (4):264–85. doi: 10.1111/1467-9477.12176.

- Skiple, Jon K., Gunnar Grendstad, William R. Shaffer, and Eric N. Waltenburg. 2016. “Supreme Court Justices’ Economic Behavior. A Multi-Level Model Analysis.” Scandinavian Political Studies 39 (1):73–94. doi: 10.1111/1467-9477.12060.

- Smyth, Russell. 2002. “Historical Consensual Norms in the High Court.” Australian Journal of Political Science 37 (2):255–66. doi: 10.1080/10361140220148133.

- Songer, Donald R., Sue Davis, and Susan Haire. 1994. “A Reappraisal of Diversification in the Federal Courts: Gender Effects in the Courts of Appeals.” The Journal of Politics 56 (2):425–39. doi: 10.2307/2132146.

- Songer, Donald R., Miroslava Radieva, and Rebecca Reid. 2016. “Gender Diversity in the Intermediate Appellate Courts of Canada.” Justice System Journal 37 (1):4–19. doi: 10.1080/0098261X.2015.1083816.

- Sunde, Jørn Ø. 2015. Høgsteretts Historie 1965–2015 - At Dømme i Sidste Instans. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

- Szmer, John, Robert K. Christensen, and Ashlyn Kuersten. 2012. “The Efficiency of Federal Appellate Decisions: An Examination of Published and Unpublished Opinions.” Justice System Journal 33 (3):318–38.

- Volden, Craig, Alan E. Wiseman, and Dana E. Wittmer. 2013. “When Are Women More Effective Lawmakers than Men?” American Journal of Political Science 57 (2):326–41. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12010.

- Vroom, Victor H., and Philip W. Yetton. 1973. Leadership and Decision-Making. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Walker, Thomas G., Lee Epstein, and William J. Dixon. 1988. “On the Mysterious Demise of Consensual Norms in the United States Supreme Court.” The Journal of Politics 50 (2):361–89. doi: 10.2307/2131799.

Appendix

Table A1. Regression results from models of the duration of case disposition time. The first column reproduce Model 4; the second column adds three experience-related variables.