Abstract

This editorial provides an introduction to OAWAL: Open Access Workflows for Academic Librarians. The intention for this crowdsourcing project is outlined along with the major topics of discussion. In conclusion, the editorial outlines next steps and future plans of the authors for the OAWAL project.

OAWAL: Open Access Workflows for Academic Librarians (Emery & Stone, Citation2014) grew out of recognition that open access (OA) publishing is not a trend or a fad but an ongoing model of content publication that librarians will be managing increasingly over the advent of the 21st century. The intention is to make OAWAL an openly accessible wiki/blog site for librarians working on the management of open access workflow within their given institutions. The website is currently constructed to be a base that librarians can build on to create context-sensitive workflows. To this end, OAWAL is agnostic regarding the route to open access; it describes and discusses multiple business models for open access publishing, and it does not promote any one given model or business plan. The six draft sections are the beginning building blocks; it is intended that these are built on with the help of library and information science professionals—through in-person comments via this blog, Twitter, Facebook, at conferences, and also via online crowdsourcing. The authors would greatly appreciate constructive criticism and suggestions on how to improve the website and its sections for information professionals and, to this end, comments have been enabled within each section. As OAWAL develops, it is hoped that a variety of workflows will be developed that can be shared with the library and information science community at large. While the website is open to all feedback, the OAWAL website was not created to be prescriptive of any one specific business model or philosophical arguments over business model selection. Furthermore, any commentary that appears as a promotion for specific publishers or vendors, or tools that do not further the topic of the section, will also not be sustained.

In order to provide the reader with an overview, the following outline provides a description of the six sections of OAWAL, as they currently stand on the website.

ADVOCACY

This section focuses on how to develop the message on open access publication to various stakeholders within the academic community. Buy-in for open access has to start at an organizational level. Once this is achieved, the message to promote open access publication both in publishing/research as well as in instruction to students in order to capture content can begin in earnest. The message needs to be consistent to constituents in all areas on campus—mandates or policies may or may not be the way to gain the greatest buy-in from the community. The promotion and value of the repository follows the initial advocacy for publication and use of open access materials. To show the dedication and seriousness within the library setting, establishing funding streams to promote both the publication and use of open access materials is essential. Repositioning of staff within an organization also shows the overall commitment to the process of making open access content a priority on campus. Embracing and acknowledging open access publishing as a viable publication model as a local community is the greatest advocacy any library and information professional can engage in.

The sections covered in “Advocacy” are:

Internal Library Message on Open Access

Communication of OA Opportunities to Your Academic Community

Mandates/Policies

Promotion of Your Repository

Budgeting for Open Access Publication

Reconfiguration of Staff

WORKFLOWS

Repository managers have been using workflows for many years in order to explain and encourage researchers to self-archive; however, the advent and take up of gold open access by funders, universities, academics, and publishers have provided new challenges to the “traditional” green workflow. Gold open access brings in new players, such as the funders and university research offices; it also changes the role of academics in the process. In addition, tracking of all open access publishing, especially the publishing that may have the greatest impact at a given institution, is a growing need. Understanding the interplay between upfront purchased content and subscribed content continues to be a struggle, and this is made increasingly more difficult in different areas or departments at your institution that have responsibility for different payment models.

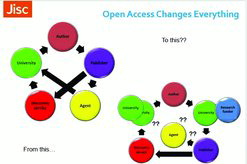

Workflows are a fast-changing area of open access and repository management. This section is possibly the most frequently updated as we learn from the implementation of new policies and best practice emerges, particularly around handling article processing charges (APC) and national research funder policies. The changes in the workflow that are caused by the introductions of APCs and funder mandates are described by Jacobs (Citation2014) and illustrated in ; as can be seen, not all of the implications for members of the scholarly information supply chain are known. Jacobs notes that universities have new obligations and opportunities and that it will take some time before all of the implications for funder mandates at a national scale become clear—it is anticipated that the Netherlands will be the next country to mandate open access (Harwood, Citation2014). OAWAL hopes to be able to expand on the new “touch points” that Jacobs describes, both in this “Workflows” section and also in the “Standards” section.

The sections covered in “Workflows” are:

The “traditional” green model

Gold Open Access

Funder mandates/policies for green and gold

The effect of gold on workflows and staffing

Pure gold vs. hybrid journals

APC processing services

STANDARDS

Open access publishing is driving a complete new set of standards from version of publication to identifiers for authors, funding bodies, and data management. These are all standards that have been developed in the past five years, and as such, they continue to be refined and further developed as new considerations arise over open access management and tracking. Some standards have been fairly widely adopted, such as ORCID, whereas other standards such as CrossMark have been slow to gain traction in the research communities at large. In addition, new usage standards for open access publications, applicable to both repositories as well as to the traditional publishing platforms, are being developed and implemented. In some cases, the library and information community is well apprised of the standards in use; however, in other cases these standards are so new that many are unaware of them.

This section looks at these new and emerging standards in more detail. As both OAWAL and these standards develop, it is hoped that the community will expand each of the sections and include best practices and examples of adoption.

shows the six parts of the “Standards” section and indicates which standards can be applied in which community.

Table 1 Standards With Reference to Each Community

LIBRARY AS PUBLISHER

As Amherst College librarian Bryn Geffert said, “It's time for libraries to begin producing for themselves what they can no longer afford to purchase and what they can no longer count on university presses to produce” (Amherst College, Citation2012).

One outcome of the rise of the open access movement is the establishment of a new breed of university presses, particularly in the United States and United Kingdom. Thomas (Citation2006) found a “growing number of library directors oversee the university press at their institution,” citing Massachusetts Institute of Technology, New York University, Northwestern University, Penn State University, and Stanford University as examples. By late 2007 the Association of Research Libraries (ARL) had commissioned a survey of its membership, finding that 44% of the 80 respondents were engaged in delivering “publisher services,” and 21% were currently planning developments. In a 2008 report to ARL, Hahn (Citation2008) indicated that 88% of those that offered publishing services were publishing journals, and 71% were publishing monographs—many of these were library–press collaborations. Seventy-nine percent also reported publishing conference proceedings. Mullins et al. (Citation2012) found that by 2012 there were a number of library publishing programs in existence publishing journals, conference proceedings, technical reports, and monographs.

More recently, some libraries, such as Amherst College, Massachusetts, have launched new ventures to publish peer-reviewed books in the humanities and the social sciences. Elsewhere there have been a number of library-led projects to establish scholarly open access journals and conference proceedings, such as Huddersfield Open Access Publishing and SAS Journals, which were funded as part of the campus-based publishing strand of the Jisc Digital Infrastructure program (Stone, Citation2011). Most recently the University College London (UCL) in the UK announced the launch of a new university press (University College London, Citation2014).

This section of OAWAL takes its inspiration from a series of minicase studies published as an editorial in Serials Review (Perry, Borchert, Deliyannides, Kosavic, & Kennison, Citation2011) in addition to a number of case studies in the U.S., such as Purdue University (open access journals), Georgia Institute of Technology (conference proceedings), and the University of Utah (monographs), and those described earlier in the UK. The aim is to grow the section as new case studies and best practice comes to light.

The six parts in this section look at the new university presses in more depth, such as the many different ways in which libraries act as publishers from hosting services to full publishing. There is a definite crossover between the expertise of eresource librarians and that of librarians involved in library publishing programs. A positive outcome of OAWAL would be to further define these criteria. Finally the section looks at the challenges and sustainability of these operations. Again, as further case studies come to light, it is hoped that OAWAL can put a series of best practice recommendations together.

CREATIVE COMMONS

This section of OAWAL has been adapted from the Guide to Creative Commons for Humanities and Social Science monograph authors (Collins, Milloy, & Stone, Citation2013), which was peer reviewed by UK academics, checked by legal experts (English law), approved by Creative Commons and part funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, and is an example of Creative Commons licensing in action!

Creative Commons (CC) is an international not-for-profit organization that aims to improve clarity about what people can do with published content. CC licences are used by all kinds of content creators—photographers, musicians, artists, Wikipedia contributors, and people collecting data, to give just a few examples. For researchers, this generally means academic books or journal articles. Creative Commons licences are available in three different versions: a simplified version; a legal version, which is the actual license; and a machine-readable license. The simplified and machine-readable versions link to the full version.

This section covers the following issues regarding Creative Commons and attempts to clarify some common misunderstandings of the license in relation to Open Access:

The link between CC licenses and open access

Copyright and Creative Commons

Funder mandates

Third Party rights and author rights

Commercial Use Questions

Benefits of publishing with a Creative Commons license.

DISCOVERY

One of the biggest complaints about all academic content and open access content in particular is an inability to discover it through standardized means. Many open access journals and other publications are not part of the standard abstracting and indexing services, and when they are, they are often not versioned correctly. In addition, there is a sense among some academics and library administrators that there is little need to curate open access content that has not been created locally. In many ways, librarians sabotage themselves by not including essential metadata in their repository entries to help aid in the discoverability of their content. In the Sage white paper, Sommerville and Conrad (Citation2014) note that discoverability can best be defined as:

Successful integration into librarians’ infrastructure for content

Integration across discovery channels

Relevant results found

Smooth authentication and usability

These points readily apply to open access content as well as commercially purchased content. This section includes the following:

Addition of global OA Content to library catalogs & discovery systems

Participation in OAISter

Necessary Metadata

Exposure of local repository on Google

Indexing of gold OA journals and the need for OA designation

Usage data (including PIRUS, IRUS-UK, COUNTER 4)

CONCLUSION

Since its launch in early March 2014, feedback on OAWAL has been very encouraging. The authors facilitated a lively roundtable discussion at the 2014 Electronic Resources & Libraries (ER&L) Conference. At this event the overall concept of OAWAL was introduced. In addition, the authors discussed the need for a place to describe the various areas of open access management that librarians and information professionals are now engaged in at their respective institutions. Each section was described, and specific feedback was sought on each topic. Suggestions were made around the mandates/policies section of advocacy along with the need to include a section on advocacy for financial models currently being utilized, metadata needed for tracking access, and funding of article processing charges within workflows. Participants also discussed whether this information could be supplied from other standards or workflow being developed by Knowledege Bases and Related Tools (KBART) and the Global Open Knowledgebase (GOoKb) project. It was noted that the CrossMark indicator is embedded on PDF versions and that this should be made clearer in the description of CrossMark and that work was underway to address the deduplication of ORCIDs that researchers may be inadvertently creating. Discussion turned to preservation and the need for a clearer mention of Portico and LOCKSS (Lots of Copies Keep Stuff Safe) in the preservation of content. Finally, there were hopes that OAWAL could indicate the current growth rates of open access publication. All in all, this was a very successful in-person meeting, and it is hoped that at future library and information science events, the conversation can be carried further.

The authors have had numerous emails of support from around the world, including Australia, the United States, South Africa, and Jisc and SCONUL (Society of College, National and University Libraries) in the UK. These comments have already led to various edits to OAWAL and the addition of workflows, such as guidelines targeted at academic institutions in developing countries from Stellenbosch University, South Africa.

The authors would also like to see where OAWAL overlaps with work already in progress by organizations such as California Digital Library, SPARC (Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition), and Jisc. Further discussions at conferences and workshops are planned in 2014/2015, and the authors hope to encourage collaboration in the form of crowdsourcing in order to provide a resource for the library and information science community.

REFERENCES

- Amherst College. (2012, December 5). Amherst College to launch first open-access, digital academic press devoted to the liberal arts. Retrieved from https://www.amherst.edu/aboutamherst/news/news_releases/2012/12/node/445320

- Collins, E., Milloy C., & Stone, G. (2013). Guide to Creative Commons for humanities and social science monograph authors. Working Paper. London, England: Jisc Collections. Retrieved from http://oapen-uk.jiscebooks.org/files/2011/01/CC-Guide-for-HSS-Monograph-Authors-CC-BY.pdf

- Emery, J., & Stone, G. (2014). OAWAL: Open Access workflows for academic librarians. Retrieved from https://library3.hud.ac.uk/blogs/oawal/

- Hahn, K.L. (2008). Research library publishing services: New options for university publishing. Washington, DC: Association of Research Libraries. Retrieved from http://www.arl.org/storage/documents/publications/research-library-publishing-services-mar08.pdf

- Harwood, P. (2014, April). Unearthing gold: Hard labour for publishers and universities? . Paper presented at the UKSG 37th Annual Conference and Exhibition, Harrogate, UK.

- Jacobs, N. (2014, February). Open Access changes everything. Paper presented at the 2014 Annual Conference of the Association of Subscription Agents and Intermediaries, London, UK.

- Mullins, J.L., Murray-Rust, C., Ogburn, J.L., Crow, R., Ivins, O., Mower, A., … Watkinson, C. (2012). Library publishing services: Strategies for success: Final research report. Washington, DC: SPARC. Retrieved from http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/purduepress_ebooks/24/

- Perry, A.M., Borchert, C.A., Deliyannides, T.S., Kosavic, A., & Kennison, R.R. (2011). Libraries as journal publishers. Serials Review, 37(3), 196–204. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.serrev.2011.06.006.

- Sommerville, M.M., & Conrad, L.Y. (2014). Collaborative improvements in the discoverability of scholarly content: Accomplishments, aspirations, and opportunities. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Retrieved from http://www.sagepub.com/repository/binaries/pdf/improvementsindiscoverability.pdf

- Stone, G. (2011). Huddersfield open access publishing. Information Services and Use, 31(3/4), 215–223. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/ISU-2012-0651

- Thomas, S.E. (2006). Publishing solutions for contemporary scholars: The library as innovator and partner. Publishing Research Quarterly, 22(2), 27–37. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12109-006-0013-5

- University College London. (2014). UCL Press. Retrieved from http://www.ucl.ac.uk/library/ucl-press/