ABSTRACT

The growing use of the internet, especially in urban centres, has made social media the contemporary discursive battleground for Muslims to dispute their cultural and political subjectivities. Muslim womanhood, particularly, has always been a concept under constant scrutiny. Previously, narratives about the ideal Muslim women were dominated by male preachers in mosques and public seminars. Nonetheless, social media has given Muslim women a platform to express what their cultural identity entails, the problems they experience, and their aspirations. This paper analyses the cyberspace activism strategy used by so-called controversial Muslim women group to express their political subjectivity within the Muslims community. This paper focuses on the Instagram account of Cadar Garis Lucu, a self-proclaimed feminist niqabi (face-veiled) community. Content analysis of Cadar Garis Lucu’s Instagram posts and in-depth interviews with its members revealed their three discursive strategies: emphasising authenticity – that their choice of face veiling is their own choice; appealing to moderate Indonesian Muslims’ interpretations of religion as an expression of love and plurality; and utilising collaborations with other similarly moderate religious social media accounts, to further justify face-veiled as a part of moderate Islam in Indonesia.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

In modern Indonesia, the concept of Muslim identity is a subject of intense conversation and deliberation. Indonesia has the world’s largest Muslim society, with over 229 million people, or about 87% of its total population. At the beginning of 2022, 57.9% of Indonesia’s population resided in urban regions, while 42.1% resided in rural areas and with 204,7 million internet users, Indonesia concluded 73.7 percent internet penetration rate (DataReportal, Hootsuite, Citation2022). One of the most prevalent practices among Indonesian Muslims, especially in urban areas, is to display their religious activities and traits on social media to the extent that their online lives might be viewed as pious efforts to increase their religiosity (Slama, Citation2018; Weng, Citation2018). Urban Muslims also experience ‘spiritual anxiety’ (Rakhmani, Citation2016) in which they desire a more Islamic form of behaviours and lifestyles in order to be proper, ideal Muslims, and it often manifested in seeking moral guidance through media content such as television shows. In the present day of digital era, urban Muslims rely more on social media such as the One Day One Juz movement that refers to the use of WhatsApp groups as a community to read and memorise the Quran together (Nisa, Citation2018); the use of Islamic dating app such as Muzmatch.com which is often branded as ‘Tinder for Muslims’ (Hasan, Citation2021); as well as Islamic web series on YouTube that embody Islamic values in their story plots (Dwifatma, Citation2018). Social media platforms' technological features allow for personal expression and discussions on Islam, promoting a more personalised interpretation of piety ().

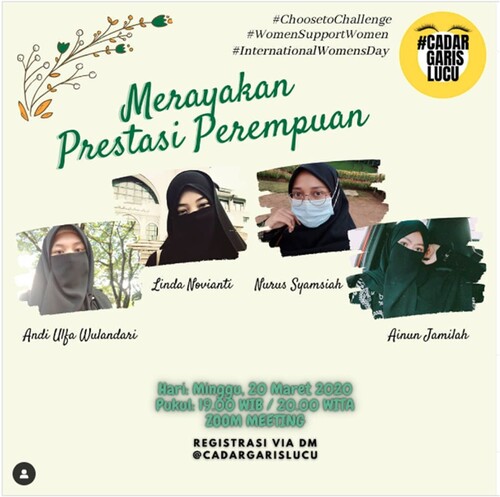

Figure 1. CGL’s post for celebrating International Women’s Day. Source: Cadar Garis Lucu Instagram account.

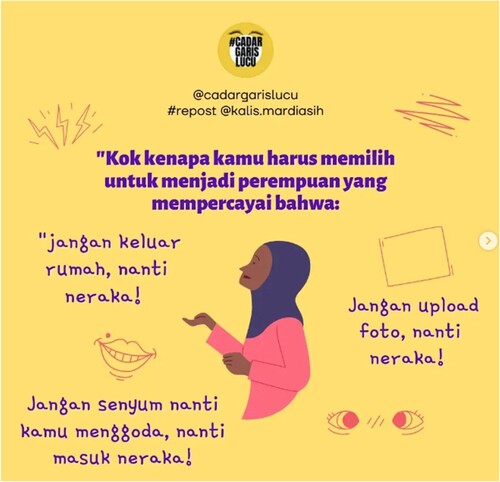

Figure 2. CGL’s post quoting a progressive young Muslim activist, Kalis Mardiasih. Source: Cadar Garis Lucu Instagram account.

Figure 3. Ainun post a wefie with in a Buddhist religious site with friends. Source: Cadar Garis Lucu Instagram account.

The Islamic revival in Indonesia is a component of a broader religious resurgence in modern Asia (Hefner, Citation2010). From Catholic Philippines transitioning to Pentecostal Christianity, the rise of meditation movements in Vietnam, to the growing population of Buddhists in China. Social media functions as a platform for different piety movements, allowing individuals to publicly display their piety, engage with others, and influence each other. In the Arab world, a group of young, middle-class, pious urban Muslims on Instagram known as GUMmies (Global Urban Muslims) demonstrate to their million followers how to live a modern, global lifestyle in an Islamic manner (Zaid et al., Citation2022). Studies suggested that Islam’s contemporary expressions rely heavily on digital media (Bunt, Citation2018) in which ‘faith, command, and control are manifest across complex systems of Muslim beliefs’ (p. 1).

Around these times of the rise of digital Islam and the post-Soeharto years, research suggested a ‘conservative turn’ (Bruinessen, Citation2013) in Indonesia’s mainstream Islam, where conservative refers to religious views that essentially comply to existing dogmas and social structure, including gender roles. In this circumstance, religious minorities and women are the most vulnerable groups (Pollard, Citation2021). Over the last two decades, more than 700 sharia (Islamic law)-based legislation have been enacted and at least 64 mandatory hijab regulations requiring women to wear hijab (headscarf) in public areas. This rule is also applied in some public schools and among female civil officials. In some towns, women are subject to night time curfews and are prohibited from wearing long pants because it accentuates the shape of their legs. The fact that these regulations, despite being controversial, are still enforced and even supported suggests idealized conceptions of Muslim(woman)hood.

In fact, even before social media, the Indonesian ‘ideal woman’ has always been a concept under constant scrutiny. During Soeharto’s 32-year presidency from 1965–1966 to 1998, known as the New Order, it was one of the things that the state carefully fabricated. The Soeharto administration often compared the state to a body, and members of society to limbs, each with its own function. For women, that function is to be wives and mothers, referring to the concept of ‘state ibuism’ (Suryakusuma, Citation2021) to describe this explicit patriarchal doctrine. Although the role of the state has diminished as a result of reform and democratization, Suryakusuma posited that religion has taken the role in domesticating women.

‘ … the state no longer has a monopoly on women’s social construction. It can now be interpreted in a variety of ways. The dominant social construction is now more “Islamic,” or at least the version of Islam desired by Islamic conservatives, which requires women to be submissive and in a subordinate position.’ (2021, p. xxix)

At this point, conservative Muslims see New Order’s encouragement for women’s education and employment as the embodiment of western liberalism values that are incompatible with Islamic moral standards. Career women have been referred to as ‘creatures of a third gender’ by an Islamic books author interviewed by Brenner for her research, because they pursue careers in a masculine world rather than ‘following their naturally feminine character’ (p. 103) which is more suitable for childbearing, childbearing, and homemaking.

In contrast to the authoritarian role of the state during the Soeharto era, disciplining religion occurs organically through non-coercive platform, such as social media. Since urban Muslims frequently use social media, particularly to encourage the cultivation of piety in their social circle, it becomes one of the key platforms in idealizations of Muslim womanhood. ‘Cultivation of piety’ is borrowed from Saba Mahmood’s work on women’s piety movement in Cairo, Egypt, as part of the global Islamic revival movement. An ethnographic observation of women Islamic study groups in Cairo mosques and discovered that shalat (praying) has become an embodied ritual (Mahmood, Citation2011) acquired by a process of regulated actions, leading to individuals taking self-empowered practical activities like practicing patience, showing kindness to others, and experiencing peace of mind. Mahmood referred to this concept as ‘cultivation of piety’, in which piety is defined as ‘ … being close to God: a manner of being and acting that suffused all of one’s acts, both religious and worldly in character’ (p. 830).

On the other hand, some studies criticized Mahmood’s approach for being too narrowly focused on religious study groups (Schielke, Citation2010). Too much research focuses on committed Muslims in consciously pious settings which contributes to the perception of Islam as ‘revivalist movements’ (p. 2), and not enough on the majority of regular Muslims who engage in activities outside of religious contexts and may not consistently demonstrate religious devotion in their everyday routines. The Muslim women in Mahmood’s research, for instance, have not participated in any media-consuming activities, or at least Mahmood did not investigate this aspect. In reality, it is difficult to find contemporary, urban Muslims, who do not engage in media consumption and, in this digital era, have an online presence. Investigating religious subjectivity, therefore, also means investigating regular Muslims’ (social) media consumption as part of their everyday lives.

It is important to note that many recent studies conducted by Indonesian women researchers offer analysis that differ from a Western liberal feminism viewpoint in assessing Muslim women’s agency against the patriarchal system. Young urban Muslim women’s use of the fashionable veils (known as ‘Hijabers’) is actually a way for them to redefine themselves (Beta, Citation2014) as members of modern, transnational society by ‘putting obvious symbols of religiousness at the service of a decidedly cosmopolitan outlook’ (p. 386). Hijabers also use social media platforms such as Instagram to present themselves as not only pious Muslim women, but also as modern and self-assured individuals (Pramiyanti, Citation2019) who ‘challenged the stereotype of being voiceless, oppressed, and backward Muslim women’ (p. 4). This research focuses on the Instagram account of Cadar Garis Lucu, a self-proclaimed feminist niqabi (face-veiled) community. Face-veiled is a longer version of hijab that covers the head, face, neck, and below the chest, showing only the eyes, which has been associated as an attribute of conservatism which often contradicted liberal feminism values. However, both the founder and the account, Ainun Jamilah and Cadar Garis Lucu, positioned themselves as feminists. They often post about gender equality, religious tolerance, and breaking the stereotype of oppressed, voiceless, Muslim women.

The choice of name was influenced by the other two popular social media accounts, NU Garis Lucu and Muhammadiyah Garis Lucu. Both are campaigns by young Muslims inside their respective organisations to dispel the idea that Muslims are extremists. They employ Garis Lucu (‘the humorous one’) as a challenge to Garis Keras (‘the radical one’). Cadar Garis Lucu followed in their footsteps, as the name was fairly popular. There are social media accounts of Katolik Garis Lucu, Hindu Garis Lucu, etc., proving that the ‘Garis Lucu’ phenomena is not exclusive to the Muslim community. While NU Garis Lucu and Muhammadiyah Garis Lucu live up to their names by releasing a great deal of humorous content, Cadar Garis Lucu provides a more secure environment for Muslim women to explore their political subjectivity with topics like what constitutes syar’i (in accordance to Islamic law) clothing, whether women are permitted to take and post selfies, seek higher education, and have office jobs. By exploring Cadar Garis Lucu’s cyberspace activism, this study argues that the use of social media by urban Muslim women, particularly in encouraging them to examine their own political subjectivity, is one of the most important platforms for the maturing of the Muslim women discourse.

Analytical framework

The political subjectivity of Muslim women in Indonesia

There are a rising number of studies on the religious subjectivity of Muslim women in Indonesia, and their findings differ significantly from the so-called liberal, Western perspective (Beta, Citation2019; Rinaldo, Citation2014). Instead of disputing whether religious activities are liberating or oppressive for women, these studies seek to determine what women benefit from these practises. These studies, which are conducted primarily by women academics, demonstrate that religious practises do not necessarily imply that Indonesian Muslim women are oppressed and backwards; rather, it is a sort of self-cultivation of piety (Mahmood, Citation2001).

Furthermore, studies on Muslim activists in Indonesia suggest that piety has become public, in a sense that piety can be expressed not only through ritual practices but also participation in the public sphere (Rinaldo, Citation2010). In other words, being religious is no longer solely a matter of one’s own experience, but also of one’s exposure to politics and the associated worldviews. This project centres on the aforementioned kind of political subjectivity, which is primarily mediated by social media. The Islamic resurgence has inspired piety movements that enable Muslim women to engage directly with the nation-state, such as advocating against and/or supporting hijab regulation. Building on this, we explore cyberspace activism via social media platforms to look at how ‘ … practices of Islamic piety can contribute to women’s political agency’ (p. 423). Rinaldo’s research indicates that Muslim activists’ political agendas tend to be polarised between gender equality (represented in the study by Rahima, a CSO closely affiliated with NU) and Islamizing Indonesia (represented by Partai Keadilan Sejahtera or PKS, an Islamist political party). Building on this, Cadar Garis Lucu has quite distinctive position. Their choice of clothes is highly conservative if not radical, yet their values and ambitions are rather progressive. It is intriguing to consider how a group that resembles PKS yet thinks and acts like Rahima would plan their political subjectivity through social media presence.

Cyberspace activism

Cyberspace activism here refers to the use of digital technologies and online platforms for mobilising, organising, and advocating for social and political change. Cyberactivists (or digital activists) mobilise their followers using social media platforms. While the platforms do not necessarily engender an ideal space for active public participation, as Lim (Citation2013) has argued, cyberactivism has allowed more people to in civic and political matters as well as social change.

Methodology

Research subject

The Cadar Garis Lucu (CGL) community was formed by Ainun Jamilah, Nurus Syamsiyah, Andi Ulfa Ulandari, Ruwidah Anwar, Linda Novianti, and Misranti Daiyah in 2020. They all met in an online discussion group for face-veiled community. As did many Indonesians, they created a WhatsApp (WA) group to coordinate the event. The WA group remained even though the event had concluded because they felt connected and shared the same beliefs. At the time, Ainun was hesitant to formally establish a community since she did not want others to believe that face-veiled women exclusively preferred to socialize among themselves.

Ainun met with Sarjoko, the secretary-general of Jaringan Gusdurian in March 2021. Jaringan Gusdurian is a civil society organisation (CSO) that supports the principles and values of the late Indonesian president Abdurrahman ‘Gus Dur’ Wahid, a staunch supporter for religious tolerance and democracy. Sarjoko urged Ainun and her face-veiled friends to establish a commune after learning about them. Ainun’s initial suggestion for the community’s name was ‘Feminis Bercadar’ (The Face-Veiled Feminists) because in their group chat, gender issues were the primary topic of conversation. The term was later deemed somewhat objectionable because ‘feminist’ is not widely supported by the Muslim community. Sarjoko then suggested ‘Garis Lucu,’ referring to the unauthorised yet popular social media account of Nahdlatul Ulama’s youth community, NU Garis Lucu. NU Garis Lucu is well-known for using humour, primarily regarding their own community, to promote a more casual approach to religion (Fadhli, Citation2020). They used memes, funny videos, photographs, and Gus Dur’s anecdotes to attract 927,000 Twitter followers and 847,000 Instagram followers (Ramadhan, Citation2021). Sarjoko reassured Ainun that the term ‘Garis Lucu’ (the humorous one) as opposed to ‘Garis Keras’ (the radical one) is not exclusive to NU, since many religious youth communities use it, such as Katolik Garis Lucu, Muhammadiyah Garis Lucu, Hindu Garis Lucu, etc.

As an organisation born during a pandemic, Cadar Garis Lucu conducts all of its operations online. Zoom is used for meetings, while WhatsApp groups and Instagram Direct Messages are utilised for conversations. The majority of their work methods are irregular and reactive to current events. Their advocacy focuses on religious toleration and gender equality. The normal workflow consists of a WhatsApp or Instagram discussion in response to a current issue or in support of a particular topic, followed by the development of a narrative and publication. Ainun, who is a significant part of Cadar Garis Lucu’s media presence, is active on Instagram, making it their primary outlet. Ainun can post for Cadar Garis Lucu while maintaining her own account. Instagram was picked because of its technological characteristics that made it simple to submit photos and videos with lengthy captions. Since each member resides in a different city, ranging from Makassar, South Sulawesi, Jogjakarta, Bandung, to Jakarta, they find it much more convenient to complete all tasks online. Cadar Garis Lucu also do not do recruitment. Except for one Christian member, who will be discussed later in the findings section, the members are all co-founders of the organisation.

Data collection and analysis

Content analysis and semi-structured interviews are employed to collect data for this study. Content analysis techniques was used to understand the compositional patterns and themes emergent in Cadar Garis Lucu’s posts. The patterns and themes were then examined in relation to the discursive constructions (Rose, Citation2016) around cadar in Indonesia. We compile a listing of all of Cadar Garis Lucu’s Instagram posts between 10 February 2021 and August 2021 (six months). Instagram is chosen not only as one of the most popular social media platforms in Indonesia, but also as the primary platform for Cadar Garis Lucu’s advocacy. Using Google Sheet, we catalogued the post’s URL, date, type (video/single image/slider image/slider video/slider image-video), subject, dominating colours, notable items, and notes (visual, caption, comments). We then classify data into four major themes and integrate it with semi-structured interview results for additional analysis.

This study intends not only to give an analysis of visual and linguistic content, but also to shed light on the human actors involved in the discourse. To comprehend the agency of Muslim women and their religious political subjectivity, we conducted semi-structured interviews with members of the Cadar Garis Lucu. The semi-structured interview is a data gathering method that focuses on the experiences and viewpoints of the research participants regarding their daily lives (Brinkmann & Kvale, Citation2018). Before asking interviewees, open-ended questions based on a methodical assessment of the literature, interviewers will establish rapport with them. It is not as free-flowing as daily conversation, but it is also not as rigid as closed-questionnaire, making it perfect for probing deeper into the experiences and opinions of participants in a more relaxed yet structured manner.

We used the snowball sampling technique to recruit participants, starting with CGL’s founder, Ainun Jamilah. Then, we asked Ainun to recommend CGL members who she believes will contribute to the discussion. We ended up interviewing four co-founders of CGL and one newly recruited Christian member. Our questions for them include why they choose to join and build organisations such as CGL, what motivates them to do so, what values they hope to instill in the Islamic discourse in Indonesia, and what they gain from their activism. As a secular Muslim educated in a secular urban institution interacting with feminists who use Islamic sources to inform their understanding of gender equality for this project (Nurmila, Citation2011), we believe that semi-structured interviews are the most effective method for gaining a thorough understanding of their thought processes.

Findings

The content analysis of Cadar Garis Lucu’s Instagram postings over a six-month period, paired with semi-structured interviews with the group’s members, uncovered the following four major themes descripted below.

Negotiating stigma

Cadar Garis Lucu’s Instagram account showcases the founder’s intent to break the stigma of face veiling practices amongst Muslim women in Indonesia. The fact that Ainun was initially hesitant to build a community demonstrates that the stigma is not simply something they feel from the outside but is also instilled within them.

‘Wherever I go, people would look at me funny … they think I must be part of a terrorist organization or something. Before I met Mas Sarjoko (of Jaringan Gusdurian – author), I was reluctant to form a community. I personally do not like being lumped into one category only, which is face-veiled Muslim women. I do not want people to think that we only want to be with our kind. I want to show that we are inclusive, tolerant, people.’

Ainun Jamilah – personal interview

The terms used here clearly showcases CGL’s interest in establishing face-veiled women also as feminists with similar interests with other feminists out there. Women’s empowerment is, in fact, one of CGL’s primary activism goals. When CGL criticised the coercion of veil in numerous Indonesian cities, they received one of the harshest repercussions. As stated by Human Rights Watch, the coercion has traumatised a great number of schoolgirls and women in the public realm who were forced to wear something they did not prefer.

‘Occasionally we found Instagram comments saying we have crossed the lines. How can niqabi women reject the hijab rule? They failed to see our point. We do not reject hijab … we reject using violence to coerce that rule.’

Ainun Jamilah – personal interview

Authenticity against/for neoliberal sense of self

Cadar Garis Lucu posts show strong detachment attempt of face-veil from patriarchal values. For example, CGL denounced the concept of early-marriage firmly and occasionally faced criticism for it. This, we suggest, is one of the key ways CGL makes claim to its different positioning as a face-veiled Muslim women’s group.

‘We would tell people that early-marriage is not always the best choice for women and they think that means we encourage young Muslims to go on a date. We don’t. We just believe that it is better for women to study, work, travel, discover themselves, instead of being shackled into marriage so early.’

Andi Ulfa Wulandari – personal interview

‘Now Ainun has found herself as what she calls an independent woman, she does not interpret her veil as a religious symbol let alone a measure of the faith and piety of a Muslim woman, but as a form of freedom for a woman to choose clothes that she believes are comfortable to wear, as one of the products cultures.’Footnote2

Another representative instance was a post summarising an event CGL organised to challenge the stigma of women’s religious expressions. The post caption reads:

‘God sees you as a human, not the identities attached to your body. So, you should also see other humans as humans, not based on the identities that make them different from you. Do and act your role and responsibilities as a human for other humans. You should not dehumanise others because the identities attached to you are different from theirs. You are a whole person, fully aware, not just a follower of this and that.’ Footnote3

Religion as an expression of love

Plurality is another concept that is significant in Cadar Garis Lucu’s works. Multiple CGL posts on religion serve as a statement of love, respect, and solidarity with Indonesia’s religious minority. This may be the reason why Gusdurian’s Sarjoko supported and encouraged Ainun and her companions to build a community at the first place, as religious tolerance and respect for minorities in Indonesia are the guiding ideals of Gus Dur and NU. Ainun is frequently observed taking photos with individuals of different religions in front of religious sites as symbols of Islam’s love and tolerance for those of other faiths. This is significant since face-veiled Muslims are frequently seen as antagonistic towards ‘regular’ Muslims (non-niqabi), much less Christians or Buddhists.

In addition, CGL also hosted online events and Instagram Live sessions in conversation with fellow young Muslim women and others from different religious backgrounds. One instance was CGL’s celebration of Buddhist’s Waisak’s day with an event titled ‘Waisak dan Perempuan’. In the video of the event, Ainun Jamilah conversed with Nath Kho on Buddhist practices. The conversation went on to discuss Buddhist interpretations of gender equality which Ainun, learning from Nath, seemed to appreciate.

In 2021, CGL recruited its first Christian member, Anastasia. Ruwidah Anwar, one of the founders, met Anastasia at a seminar hosted by Muda-Mudi Lintas Iman organization. Anastasia, who has a background in psychology, is invited to join the team so she may contribute her knowledge in CGL posts narratives.

‘I am interested in CGL’s values. It didn’t feel weird to be around them because we were friends first. I love talking to the rest of CGL members because we share the same principles. I’d like to think that I am here not only because I am Christian but also because I can contribute something with my psychology education background.’

Anastasia – personal interview

Networks with similar accounts

In a networked culture, online communities are developed not only when there is ongoing communication or expanding online membership, but also when people are emotionally invested in the organization (Campbell & Tsuria, Citation2021). This definition emphasizes both the physical and philosophical aspects of an online community. As a community born from a pandemic, CGL benefits from this model of a networked society. Their online cooperation with progressive and moderate Islamic CSOs like as Mubadalah, Gusdurian, and NU Garis Lucu are frequently highlighted in their online posts. Collaborations of this nature assist CGL in branding themselves as part of an inclusive and moderate Islam, a strategy that Ainun had adopted for some time prior to establishing CGL.

‘I have been branding myself as an inclusive, tolerant, and gender-sensitive Muslim woman, even though I do not look like it … what with my face-veil and all. I try to gather with people from all backgrounds, all religions, and I am happy that the network I’ve built got me and my friends to where we are right now.’

Ainun Jamilah – personal interview

‘The CGL network really fascinates me. I want to know them, collaborate with them, because from their friends and colleagues I got a picture of what kind of organization they build. It makes me want to be part of that kind of movement, even though I am not a Muslim.’

Anastasia – personal interview

Discussion

Individuals’ capacity to become producers of religious narratives and to participate in assessing and controlling religious practice is dramatically enhanced by social media (Lövheim, Citation2021). It is an ideal platform for self-expression and discussion, including on religious issues, due to the low barrier to entry and interactive features. Cadar Garis Lucu utilize social media for their cyberspace activism as a so-called controversial Muslim women group to express their political subjectivity within the Muslims community. The founders do so by deploying three discursive strategies as discussed below.

First is by highlighting authenticity – that their choice of face veiling is their own choice. On the one hand, the idealised ‘authentic self’ could be perceived as a neoliberal response to contemporary interpretations Islamic norms in Indonesia. On the other hand, as niqab or face veiling are often seen as closer to radicalised versions of Islam (seen as dangerous and backwards by the government and many moderate Muslims in Indonesia), Cadar Garis Lucu’s effort to connect the face-veiling practice to feminist interpretations of Muslim womanhood can be seen as subversive to popular Islamic interpretations of how Muslim women should dress in Indonesia. In other words, the authenticity of the self, according to CGL, should be the grounds from which a woman’s religious expression is understood.

Second, as demonstrated in the caption discussed previously, they appeal to Nahdlatul Ulama and many moderate Indonesian Muslims’ interpretations of religion as an expression of love and, thus, the significance of the commitment to plurality. These are represented in Cadar Garis Lucu’s multiple posts on the importance of solidarity with religious minorities in Indonesia. CGL posted a popular quote by Jalaluddin Rumi, a sufi scholar whose writings on love and Islam regained significance at present time. Another post discussed the importance of celebrating differences between religious beliefs.

This strategy is also represented in the recruitment of their first Christian member. This, we suggest, fortifies the founders’ claim that their own practices of face veiling should be seen as part of the plural expressions of religiousness. Third, Cadar Garis Lucu made use of their collaborations with other similarly moderate religious social media accounts such as Mubadalah, Gusdurian, and NU Garis Lucu. CGL reposted, for instance, a video by Gusdurian Makassar. They also organised events with speakers from Mubadalah and a quote from NU Garis Lucu. By positioning themselves as friends and collaborators, the account provides further justification that niqab can be a part of more moderate Islam in Indonesia.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Andina Dwifatma

Andina Dwifatma is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Faculty of Arts, School of Social Sciences in Monash University, Australia. She is also a lecturer at the School of Communication, Atma Jaya Catholic University of Indonesia.

Annisa R. Beta

Annisa R. Beta is a lecturer at the School of Culture and Communication, University of Melbourne, Australia.

Notes

References

- Beta, A. R. (2014). Hijabers: How young urban Muslim women redefine themselves in Indonesia. International Communication Gazette, 76(4–5), 377–389. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048514524103

- Beta, A. R. (2019). Commerce, piety and politics: Indonesian young Muslim women’s groups as religious influencers. New Media & Society, 21(10), 2140–2159. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819838774

- Brenner, S. (2018). Islam and gender politics in late new order Indonesia. In A. C. Willford & K. M. George (Eds.), Spirited politics: Religion and public life in contemporary Southeast Asia (pp. 93–118). Cornell University Press.

- Brinkmann, S., & Kvale, S. (2018). Doing interviews. Sage.

- Bruinessen, M. v. (2013). In M. v. Bruinessen, & P. Muse (Eds.), Contemporary developments in Indonesian Islam : Explaining the “conservative turn.” Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

- Bunt, G. R.. (2018). Hashtag Islam: How Cyber-Islamic environments are transforming religious authority. University of North Carolina Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.51499781469643182_bunt.

- Campbell, H. A., & Tsuria, R. (Eds.). (2021). Digital religion: Understanding religious practice in digital media (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429295683.

- DataReportal, Hootsuite, We Are Social. (2022). “Digital 2022: Global Overview Report.” https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2022-global-overview-report

- Dwifatma, A. (2018). Oposisi Biner Representasi Perempuan Dan Laki-Laki Dalam Webseries Istri Paruh Waktu Di Youtube. Wacana: Jurnal Ilmiah Ilmu Komunikasi, 17(2), 217–227. https://doi.org/10.32509/wacana.v17i2.647

- Fadhli, H. A. 2020. Membaca NU garis lucu (NUGL) sebagai upaya pencegahan faham radikalisme Di kalangan remaja Indonesia. DINAMIKA : Jurnal Kajian Pendidikan dan Keislaman, 5(2), 21–38. https://doi.org/10.32764/dinamika.v5i2.731

- Harris, A. (2004). Future girl: Young women in the twenty-first century. Routledge.

- Hasan, F. (2021). Keep it halal! A smartphone ethnography of Muslim dating. Journal of Religion, Media and Digital Culture, 10(1), 135–154. https://doi.org/10.1163/21659214-bja10042

- Hefner, R. W. (2010). Religious resurgence in contemporary Asia: Southeast Asian perspectives on capitalism, the state, and the new piety. The Journal of Asian Studies, 69(4), 1031–1047. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021911810002901

- Lim, M. (2013). Many clicks but little sticks: Social media activism in Indonesia. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 43(4), 636–657. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2013.769386

- Lövheim, M., & Lundmark, E. (2021). Identity. In H. A. Campbell & R. Tsuria (Eds.), Digital religion: Understanding religious practice in digital media (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429295683.

- Mahmood, S. (2001). Rehearsed spontaneity and the conventionality of ritual: Disciplines of Şalat. American Ethnologist, 28(4), 827–853. https://doi.org/10.1525/ae.2001.28.4.827

- Mahmood, S. (2011). Politics of piety. Princeton University Press.

- Nisa, E. F. (2013). The internet subculture of Indonesian face-veiled women. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 16(3), 241–255. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877912474534

- Nisa, E. F. (2018). Social media and the birth of an Islamic social movement: ODOJ (One Day One Juz) in contemporary Indonesia. Indonesia and the Malay World, 46(134), 24–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639811.2017.1416758

- Nisa, E. F. (2022). Face-veiled women in contemporary Indonesia. Taylor & Francis.

- Nurmila, N. (2011). The influence of global Muslim feminism on Indonesian Muslim feminist discourse. Al-Jami'ah: Journal of Islamic Studies, 49(1), 33–64. https://doi.org/10.14421/ajis.2011.491.33-64

- Pollard, R. (2021). New culture wars worsen political slide in Indonesia. Bloomberg Asia Edition. 2021. https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2021-11-22/indonesia-s-jokowi-needs-calling-out-over-culture-wars-and-rising-populism?s=08. Article issued at November 23, 2021 at 10:00 AM GMT+11

- Pramiyanti, A. (2019). Being me on Instagram: How Indonesian hijabers reframed the nexus of piety and modernity. Queensland University of Technology.

- Rakhmani, I. (2016). Mainstreaming Islam in Indonesia. Palgrave Macmillan US. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-54880-1.

- Ramadhan, A. J. 2021. Deradikalisasi Agama Melalui Permainan Bahasa Satire-Humor Pada Akun Twitter NU Garis Lucu. UIN Sunan Ampel Surabaya.

- Rinaldo, R. (2010). The Islamic revival and women’s political subjectivity in Indonesia. In Women’s studies international forum Vol 33 (pp. 422–431). Elsevier.

- Rinaldo, R. (2014). Pious and critical: Muslim women activists and the question of agency. Gender & Society, 28(6), 824–846. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243214549352

- Rose, G. (2016). Visual methodologies: An introduction to researching with visual materials (Fourth Edition). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Schielke, S. (2010). Second thoughts about the anthropology of Islam, or how to make sense of grand schemes in everyday life. ZMO Working Papers, 2, 1–16.

- Slama, M. (2018). Practising Islam through social media in Indonesia. Indonesia and the Malay World, 46(134), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639811.2018.1416798

- Suryakusuma, J. (2021). Ibuisme Negara: Konstruksi Sosial Keperempuanan Orde Baru (2nd ed.). Komunitas Bambu.

- Weng, H. W. (2018). On-offline Dakwah: Social media and Islamic preaching in Malaysia and Indonesia. In K. Radde-Antweiler & X. Zeiler (Eds.), Mediatized religion in Asia (1st ed., pp. 89–104). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315170275-9

- Zaid, B., Fedtke, J., Shin, D. D., El Kadoussi, A., & Ibahrine, M. (2022). Digital Islam and Muslim millennials: How social media influencers reimagine religious authority and Islamic practices. Religions (Basel, Switzerland), 13(4), 335. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13040335