Abstract

The structure and organisation of the machinery of government are key to the ambitions of political coalitions. When portfolio allocation and agencification are a function of political choice, political volatility should also affect the internal structure of government administrations. This study tests the effects of political turnover of individual ministers and of the political ideology of coalitions on a dataset of intra-ministerial changes in Dutch ministries between 1980 and 2014. Findings indicate that the turnover of political heads of departments and the shifts in policy preferences between successive coalitions indeed affects the internal structure of ministerial departments. Political variables have a strong impact, particularly changes in the left–right position of the government. A clear pattern for how precisely politics affect the structural design of public organisations remains absent, in spite of the robustness of the findings. Most ministries experience significant effect of executive turnover, sometimes increasing the hazards of intra-organisational transitions and sometimes increasing stability. It turns out that ministers can substantially re-arrange their organisations in line with their policy preferences but do not necessarily do so. Sometimes the effect of liberal ideology dominates, sometimes the effect of the policy preferences with respect to a specific domain prevails.

The structure and organisation of the machinery of government is key to the ambitions of political coalitions for a variety of reasons. Not only does the machinery of government form the main tool of elected politicians to exercise control, to formulate and to implement their preferred policy programmes, but it also signals the agenda and policy priorities of the incumbent government to the public (Hammond Citation1986; Mortensen and Green-Pedersen Citation2015; Tosun Citation2018). Moreover, with certain structural designs incumbent politicians attempt to hardwire their favoured policies and increase the transaction costs for their future opponents should they attempt to ‘kill’ their programmes (Lewis Citation2002; Moe Citation1995). When a new coalition gains control over the government machinery after elections, reorganising the central government lends politicians tools to – not seldom symbolically, however – herald new policies and programmes (Pollitt and Bouckaert Citation2011). Finally, the organisation of central government defines how well incumbent coalitions can steer and coordinate complex and interdependent policy programmes (Bouckaert et al. Citation2010).

The study of the machinery of government has gained traction among political science and public administration scholars in parliamentary systems. While the relationship between (conservative or neo-liberal) political ideology and the organisation of central government was central to New Public Management (NPM) studies (Aucoin Citation1986; Pollitt and Bouckaert Citation2011), institutionalist analyses of the ‘machinery of government’ emerged in the studies on Westminster parliamentary systems in particular. These studies point at the importance of political and administrative drivers, especially the role of the prime minister and bureaucratic (self-)interests such as bureau-shaping (Davis et al. Citation1999; Pollitt Citation1984; White and Dunleavy Citation2010). In contrast to most Americanist studies, the Westminster-oriented machinery of government studies are qualitative case studies on the role of political drivers as regards portfolio redesign. Though these Westminster studies acknowledge the role of political parties, cabinet ministers or cabinet policy positions, they do not systematically analyse the influence of political factors on structural changes in government bureaucracies.

Recently, political science scholars have given more systematic and careful attention to the political dynamics at the intersection of politics and bureaucracy. Mortensen and Green-Pedersen (Citation2015), taking Hammond’s (Citation1986) basic premise that the structure of a public bureaucracy reflects the agenda of the incumbent coalition, examined issue attention and parliamentary agenda-setting processes as the most important drivers of ministerial design. They examined the effects of political agendas on ministerial reforms in Danish central government. More precisely, Mortensen and Green-Pedersen examined the creation and termination of entire ministries as a function of the length of parliamentary debates on specific issues. They found that substantial changes in political attention to certain issues indeed influenced the number of ministries. While their study confirms the relationship between political ideology and ministerial design, their study is limited to the Danish parliamentary system where the presence of single-party minority governments allows for models on direct effects of agenda-setting processes on the number of ministries. Whereas Mortensen and Green-Pedersen examined portfolio design as a function of agenda dynamics, Sieberer et al. (Citation2019) examined the politics of portfolio design as a function of coalition formation dynamics. In a comparative study comprising in nine Western European parliamentary systems, they estimated the effects of changes in the partisan composition of the cabinet, a change of the prime minister, a change of cabinet policy positions, and the number of parties in cabinet on the change between competencies among ministries or between the heads of ministries. The authors found that the design of ministerial portfolios will most likely change within one year after the partisan composition of the cabinet has changed or after the appointment of a new prime minister. Changes in the ideological position of subsequent cabinets or the number of effective governmental parties had a negative but very weak effect on portfolio redesign. Both studies of Mortensen and Green-Pedersen (Citation2015) and Sieberer et al. (Citation2019) confirm herewith U.S. theories of structural choice politics that the structure of central government is a function of political logics (Lewis Citation2002; Moe Citation1995).

In our study, we aim to build further on these insights by examining politics as the driver of changes in the structure and organisation of central government. We will examine the effects of political change on the structure and organisation of ministries. We look at political changes at two levels: a change in the composition of a coalition and a change in the party of the minister heading a ministry. In addition, we will also include portfolio re-designs within ministerial departments. Our argument is that when the structure and organisation of central government is a function of political choice, this should also be the case for the internal structure of government agencies. To this end, we look at its effects on different levels of structural reform: not only at the ministerial portfolio level, but also the directorates-general and sub-directorates below.

For our first aim, to estimate the effects of ideological preferences at different levels of executive government on structural change, we have developed models with minister-level and cabinet-level political preferences. Our minister-level measure examines the turnover of the political executive that is heading a ministry to one from a different political party (with, arguably, a different ideological position). The minister-level variable serves as an adjustment to the existing models by accounting for the fact that in certain cabinet models, individual ministers enjoy a high amount of autonomy as regards the management and design of their own portfolios (Andeweg Citation2000). Theoretically, our study expands the previous studies by zooming in on the influence of ministers. While our variables are causally ‘closer’ to the dependent variable than Mortensen and Green-Pedersen (Citation2015), we do not run the risk of overestimating the single role of the prime minister as in the Westminster studies, and go a level deeper than the Sieberer et al.’s (Citation2019) study by including the individual minister level.

Next, because we realise that individual ministers do not operate only guided by the ideological positions of their political party, we take into account the average position of the coalition. We therefore look at the effects of the particular ideological policy position (for instance on expanding military policy) of the incumbent coalition on structural changes in specific domains (ministry of Defense). Then we zoom out further, by looking at the differences between rightwing and leftwing coalitions in terms of how shifts between left and right affect structural changes of government.

For our second aim, we will focus on the politics of structure inside central government ministries, instead of focusing merely on the structure and government of central government. In prevailing studies, focus has been on explaining changes at the level of entire ministries: mergers, fissures, or termination of entire ministerial departments and portfolios. Existing studies on portfolio allocation included the transfer of divisions between ministries when new portfolios are formed or existing ones dissolved, but they did not study the effects of political factors on intra-departmental changes directly. There has been scant attention to the politics of structural choice that occurs inside public organisations. Ministries may retain their names and legal status uninterruptedly over longer periods of time. Studying administrative reorganisation at the ministry level, will therefore merely signal the persistent need of their functions, i.e. social welfare, financial regulation, or defense. It will conceal to observers the changes that take place under the surface of organisations, i.e. the more subtle shifts within a policy domain. Mortensen and Green-Pedersen (Citation2015) and Tosun (Citation2018) have shown that the design of ministries indeed reflects policy changes not only by name changes of administrative units but also by mergers or splits within ministerial organisations. What is less known, is how ministerial policy preferences influence levels below the apex of ministerial departments (see also Lichtmannegger Citation2019). What lies beneath, hence are the structural changes within ministries that may be very consequential for the policy domain governed. If Hammond's ‘structure equals agenda’ is right, the political ideology of the governing political parties should affect these structural changes directly.

The theoretical refinement, however, comes at an empirical cost. In order to study the estimated effects of the two levels of the executive, we limit ourselves to the case study of the Netherlands. Portfolio design in the Netherlands is the resultant of a process of coalition and cabinet formation where multiple parties are involved. Portfolios are allocated on the basis of a mix of electoral results and bargaining among parties. As Sieberer et al. (Citation2019: 1) already show how ‘the makeup of ministries is often reformed in the context of coalition formation’. Unlike some of foreign counterparts, the Dutch prime minister does not have the (final) authority to decide on the allocation of the portfolio among parties and ministers and merely acts as a primus inter pares (Andeweg Citation2000). Given the combination of the facts that Dutch cabinets are subjected to the principle of collective decision-making as well as to the principle of non-interventionism between ministers, which lends them a substantial degree of autonomy on matters that are exclusively within their own domain of competence, it is a good case to study the two-level decision-making structure with regard to portfolio allocation.

In sum, we aim to dig deeper on two fronts: First, we look at both the effects of ideology shifts caused by turnover of political executives heading each department, and at ideology shifts between coalitions. Second, we argue that this influence becomes visible not only in portfolio allocation but through transitions within Ministerial departments at the level of Directorates-General and the sub-directorates below. To this end, we test the effects of political turnover and political ideology at the individual minister level on a dataset of intra-ministerial changes in the Dutch ministerial departments that existed between 1980 and 2014. The dataset contains observation on transition events experienced by 2682 ministerial divisions and sub-divisions – directorate generals and directorates respectively – of all ministries that have existed during the period of study.1 The structure of this paper is as follows. First, we will discuss the prevailing literatures and formulate our hypotheses. Second, we will illustrate from our dataset the types of intra-ministerial changes that we have studied. Third, the design of the research, data and method, is explained. The fourth section presents the findings and the paper ends with a discussion, followed by a conclusion.

Political effects on ministerial design

The design of administrative agencies is a function of political choice. In multiparty parliamentary systems, general elections are followed by the formation of a coalition government. The game ends with the design and allocation of ministerial portfolios among parties and the appointment of individual office-holders to the resultant ministries. Political parties that have managed to become part of the government will bargain for the ministerial portfolios that are closest to their most preferred policy issues (Laver and Shepsle Citation1994; Druckman and Warwick Citation2005). Incoming coalitions bargain over the (re-)allocation of portfolios between coalition partners. After the distribution of portfolios, the parties’ leadership appoint ministers tasked to implement their party’s part in the coalition agreement within their ministries. But portfolios are not carved in stone; they can be shaped and reshaped. Over a longer time span we can see mergers and fissures of ministries often accompanied by changes of ministerial names. Hence, ministries need not remain the same over a longer period; each new incoming cabinet can reshuffle ministries, rename them and then reorganise the units within ministries. Important determinants of this process are changes regarding political parties’ preferences, issue and agenda dynamics, changing cabinet ideologies, the composition of the cabinet, and the role of the prime minister (Mortensen and Green-Pedersen Citation2015; Sieberer et al. Citation2019; Tosun Citation2018; White and Dunleavy Citation2010).

However, while these studies underscore the importance of political factors, they do not systematically address the fact that structural changes can be the outcome of the preferences of either the party of the individual office-holder heading a ministry, or the incumbent coalition. Existing studies conceive of the process of ministerial design as the outcome of a cabinet formation process and neglect the autonomous space that individual ministers may have to redesign their ministries in line with the preferences of their specific party. The leadership of coalition parties delegates the implementation of the government programme to the cabinet as a collective actor, but individual ministers heading specific ministries have ample discretion to fine tune the internal design of their ministries in accordance to their parties’ programme. The assignment of ministerial portfolios to political parties is a first step for cabinet coalitions to re-shape governmental policies, but in order to substantially alter policies, ministers may substantially reorganise the lower levels within a ministry as well. The changes to ministerial portfolios may be accompanied by changes to directorates-general and/or their subordinate divisions. These changes can vary from name changes to entire overhauls of directorates-general and divisions. At these levels, a minister can reorganise the administration without parliamentary approval. Yet, these pockets of sub-units contain the core of the policy-making machinery of ministries. It is at those levels where the policy preferences of cabinet coalitions and individual parties can be cast into the form of an agenda through the design of the departmental structure (Hammond Citation1986). In more general terms, the government agreement is an incomplete contract imposed on cabinet whose details are determined by individual ministers who act as the delegatees of their party (Andeweg Citation2000; Thies Citation2001).

We assume that the Manifesto’s data reflect the combined ideological preferences of the coalition on a given policy domain central to a ministry. We also take the ideological preference of a political party as the indicator of the agenda of the individual executive from that particular party, when he/she starts leading a Ministerial department. To illustrate, if the political party of a new Minister is in favour of expansion of Education (as opposed to his/her predecessor who represents a different political party ideology), we expect that the number of organisational transitions (hence, its hazard rate) within the Department of Education will increase.

It is our expectation, then, that political preference changes at both the cabinet level and at the level of the office-holder who is appointed to head a specific ministry will affect the internal design of ministerial departments, and not only the redesign of portfolios at the ministry level. Hence, we will examine the relationship between political turnover at the level of individual ministers and structural changes within ministries (cf. Bertelli and Sinclair Citation2018; Boin et al. Citation2010; Davis et al. Citation1999; Götz et al. Citation2018; Greasley and Hanretty Citation2016; James et al. Citation2016; Laegreid et al. Citation2010; Lewis Citation2002; MacCarthaigh Citation2014, O’Leary Citation2015; Pollitt Citation1984; Sieberer et al. Citation2019). We start with the influence of political choice at the individual level and zoom out to look at the effects of the coalition’s policy preferences and then the influence of the coalition’s rightwing versus leftwing signature. This leads to the following hypotheses:

H1: If there is political turnover of the individual executive heading the ministry, whereby the successor represents a different political party than the previous minister, the hazard rate of administrative units within that ministry will increase.

Our second hypothesis concerns the effects a change in cabinet may have on the hazard rate of administrative organisations. We hypothesise that the domain-specific ideological position of incoming government coalitions is likely to be reflected in organisational transitions (i.e. name changes, merger, split, abolition or privatisation of individual public organisations or their sub-units) within specific Ministries.

H2: If the average policy preference of the coalition with respect to a particular ministry’s policy domain changes from one incumbent government to another, the hazard rate of administrative units within that particular ministry will increase.

In line with Lewis (Citation2002), and Götz et al. (2015) we also expect that some more generic ideological characteristics of government matter across the board for all ministries. Rightwing ideology has a likely effect on administrative survival across all Ministries, since it favours free markets, economic incentives, economic orthodoxy and law and order (to name a few more rightwing aspects) over market regulation, economic planning, protectionism, nationalisation and expansion of state provisions in for instance welfare and education (at the left side of the political landscape). The effect is not by definition negative though, it merely implies organisational change rather than downsizing of government. Both Götz et al. (2015) and Greasley and Hanretty (Citation2016) find that leftwing governments are less inclined to terminate public organisations than rightwing governments, unless budgetary pressure increases. We therefore hypothesise that ideology matters, either rightwing or leftwing, for the organisational hazard rates in all departments.

H3: If the preferences of political parties in the coalition change from rightwing to leftwing or vice versa, the hazard rate of administrative organisations within ministerial departments will increase.

Machinery changes in Dutch central government

We are testing the hypotheses on a dataset of ministerial changes in the Netherlands between 1980 and 2014. The Netherlands is a parliamentary democracy. Executive authority rests with the cabinet. The cabinet is chaired by the prime minister, as a first among equals, and consists of 10–20 ministers and a similar number of junior ministers, appointed by and usually from the political parties that form a governing coalition after the parliamentary elections. Most ministers head a ministerial department, though some ministers do not have their ‘own’ executive organisation (such as the Minister for Developmental Aid, who resides at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs). Ministerial portfolios are typically re-allocated and redesigned in the formation process of a new coalition after parliamentary elections. An important feature of the Dutch case for the present study is the presence of ministerial autonomy, exemplified by the ‘non-intervention’ principle (Andeweg Citation2000). After cabinet formation and the allocation of ministerial portfolios over the coalition parties, party leadership appoints individual ministers to individual ministries. Ministers have discretionary powers to reorganise their ministries without interference of other ministers, including the prime minister, as long as organisational changes do not involve transfers of units between ministries. This feature of the Dutch central government system allows us to examine the effects of cabinet- and minister-level changes on the structure and design of ministerial departments as two interlinked but analytically separate drivers of change.

The Dutch case is also interesting because it has a number of characteristics that allow for the study of the effect of political volatility on administrative structure. According to Sieberer et al. (Citation2019), the Netherlands shows a high number of Ministerial reforms when compared to eight other European democracies. It regularly has changing coalition governments which makes the effect of changes in composition of government both feasible to study and likely to occur. It has a more or less stable political landscape represented in its various coalitions. It has no tradition of patronage, or Ministerial cabinets that make administrative organisation likely as the result of mobility of upper-echelon staff with every move of their political chief. Finally, its administrative reorganisation requires only Royal or Ministerial decrees (depending on level of reorganisation), which disables the effect of veto players and makes the relation between political preferences and administrative change more clear and straightforward (Sieberer et al. Citation2019).

After national elections, ministerial portfolio reshuffles and major reorganisations of ministerial departments take place when a new government is installed. Yet, intra-ministerial reorganisations and transitions occur on a more frequent basis. To illustrate this, we take a closer look at a particular individual department, such as the Ministry of Economic Affairs. Major transitions within the ministry from an energy-producing department to a regulator of private-sector competition took place after turnover of political executives. The centre/rightwing coalition of prime minister Ruud Lubbers (Lubbers I, 1982–1986) put a conservative-liberal at the helm of the Economic Affairs Department, later succeeded by a conservative Christian-Democrat who had a long career as civil servant in the Ministry of Economics. In those years, organisational units such as ‘sub-directorate mining and coal’ were replaced by ‘sub-directorate energy-saving and diversification’ and ‘energy policy and mining’. These transitions indicated a new policy strategy regarding energy production and use: moving away from fossil fuels and a production-orientation towards alternative energy sources, energy efficiency and governance. Ultimately, the policy shift visible in departmental transitions was formalised in the Electricity Law of 1989, which separated production from consumption (Agterbosch et al. Citation2004), and the Multi-Year Agreements (Meerjarenafspraken) with industry on Energy efficiency which the Ministry initiated in 1992 (Court of Audit Citation2015). This re-orientation is further illustrated by the next round of administrative changes. A new Minister from the liberal party D66 entered the scene in 1994 and introduced novel research programmes and policy initiatives on increased competition in the Dutch energy market (Ministry of Economic Affairs Citation1995). Around the turn of the century, again under the reign of a liberal (now conservative) minister, changes become visible in the names and composition of DGs and sub-directorates. The Directorate-General (up until now called ‘DG Energy’) and its sub-directorates all changed from energy-producing sub-directorates (with illustrative names such as ‘electricity’, ‘oil and gas’) to market regulating units (now named ‘energy market’, ‘energy strategy and use’, ‘energy production’). The policy-makers clearly shifted from producing to regulating. They pushed the envelope even further when the DG that governed the energy market merged with the DG regulating Telecom in 2007. These organisational units had little else in common than the fact that they were both regulating private market commodities.

Similar shifts are visible in the Ministry of Housing, where the Directorate-General Volkshuisvesting (which means ‘Housing’ in the sense of providing houses) turned into the DG Wonen (which means ‘Living’ in the sense of residing in a house) in 2003, after a conservative-liberal minister took over from a social democrat (cf. Ekkers and Helderman Citation2010). Its sub-directorates meanwhile changed their names related to ‘building’, to organisational labels such as ‘city and region’ and ‘information management’. These examples not only illustrate how political turnover goes hand in hand with organisational restructuring, but also how liberal agendas on (welfare) state retrenchment become visible in changes within Ministries (ibid.).

Research design

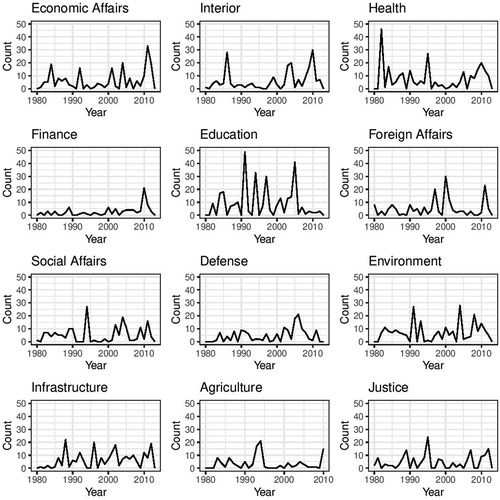

We test the above hypotheses across administrative reorganisations in 12 ministries of the Netherlands from 1980 to 2014. Our dataset, developed as part of the SOG-PRO project, records the year that each organisational entity within a ministry experiences a transition that signals an administrative reorganisation for that entity (see also Bertels and Schulze-Gabrechten Citation2020). For the 12 ministries (see ), we include all entities at both one and two hierarchical levels below the ministry itself (directorates and sub-directorates). The dataset contains an entry for each entity for every year that it exists, beginning in the year of its creation (or 1980 if it existed prior to the sampled period) and ending in the year that it experiences a transition. Transitions comprise pure eliminations, name changes, hierarchical level transfers, lateral transfers (e.g. the transfer of a sub-directorate from one directorate to another), splits, secessions, mergers, absorptions, and other more complex reorganisations involving several entities transitioning to multiple successors.2 In our models we pool all these transitions: any transition is considered the end of a unit phase. The main reason for pooling is that we are here primarily interested in observable effects of political change. Due the fact that the Dutch government does not release data on budget or personnel sizes at the level of individual sub-units, we remain agnostic about the weight of each transition. That is, a name change may signal a more substantial policy change than the merger of two or more units.3 For the same and some other practical reasons, pooling of transitions has been common practice in virtually every prevailing study of agency termination and survival (cf. Kuipers et al. Citation2018). When one or more entities emerge from a transition (as from a split, for example), we consider these to be newly created entities. As a result of this construction, our dependent variable for administrative reorganisation is coded zero for every year that an entity exists until the year it experiences a transition, when it is coded one. The year after an entity receives a code of one it drops out of the dataset. displays the number of entities per year that experience an end transition for each ministry.

Table 1. Dutch names of ministries and CMP sources.

We include several independent variables to test the above hypotheses. To test the first hypothesis, we employ a binary political turnover variable that is equal to one for an entity if the political executive heading its parent ministry comes from a different party than the political executive in the previous year. Thus, if the political executive does not change or if the succeeding executive comes from the same party, the variable is coded zero. We obtained this information from the website ‘www.parliament.com’ of the Parliamentary Documentation Centre (PDC, now independent but originally part of Leiden University – currently still partnering with Leiden University, Maastricht University, the Documentation Centre for Political Parties and the Centre for Parliamentary History in the ‘Montesquieu Institute’. In order to test H2, we include variables for 8 of the 12 ministries that express the weighted party position of incumbent coalition on particular issues relevant to that ministry. These are drawn from Comparative Manifestos Project data4 and are identical for all entities within a specific ministry. For four ministries, we did not identify appropriate domain-specific variables from the Comparative Manifestos Project dataset and so do not test H2 for these ministries.

In order to measure the ideological preferences of the entire government in a given year (identical for all entities existing in that year) for H3, we use the RILE (Right–Left) index from the Comparative Manifestos Project by averaging the RILE score across coalition partners and using a party’s seat share from the previous election as weights. This index estimates parties on a right–left political dimension, with positive scores indicating rightwing positions, and negative scores indicating leftwing positions. For European countries without a communist past, such as the Netherlands, this is a reasonably valid indicator of ideological position (Mölder Citation2016). The precise specification for each is provided in and figures showing the annual number of transitions for each ministry alongside changes in the main explanatory variables are included in the Online Appendix.

To test the hypotheses, we run a series of logistic regression models with one model for each ministry. Using logistic regression to estimate what is essentially survival data are particularly appropriate in our case because without knowledge of the precise date at which transitions occur, we instead model for each year the probability that a transition occurs. The close relationship between estimates obtained from such a model and those obtained by a Cox regression model has been established (Efron Citation1988). We include an entity’s age (in years) since creation (which could be its actual creation or the year in which a new entity succeeded from another as a result of a name change or some other transition) and the annual unemployment rate as control variables. Controlling for age has been shown to reduce the bias of coefficient estimates when using logistic regression for event history analysis (Ngwa et al. Citation2016). To allow for flexibility in duration dependence, we use natural cubic splines for age unless doing so does not change the results of the model, in which case we use the more parsimonious linear duration dependence (Beck et al. Citation1998).

We additionally control for the effect of unemployment, in line with previous studies (Sieberer et al. Citation2019). For instance, Greasley and Hanretty (Citation2016) state that in times of recession dismantling government organisations is unlikely because it will increase unemployment (cf. Kuipers et al. Citation2018). Because our entities are dependent on each other hierarchically (that is, an entity may experience a transition while its parent entity also experiences a transition and such a coincidence of events violates the independence of observations), we cluster the standard errors of our estimates by the highest hierarchical level. The Online Appendix includes correlation matrices for the variables in each model.

Results

reports the results for the 12 models (one model for each ministry). Figures in the Online Appendix display the substantive significance of all statistically significant model coefficients through predicted probability plots (plots of the predicted probability that an entity experiences a transition against the independent variable). Most of these plots reveal relatively modest substantive effects, with several notable exceptions indicated here. In 9 of the 12 models, the effect of the political ideology of the government (as measured by its average RILE index score) on the probability that an entity experiences a transition is statistically significant (p < 0.05). For eight of these models the effect is positive, indicating that the more right on the right–left scale of the parties in government, the greater the probability that an event experiences a transition. For both Social Affairs and Health, the size of the effect is relatively large, with an increase of 50% and 70%, respectively, in the probability of transition across the range of the RILE score. In the case of Education and Culture, the effect is negative and substantively large, indicating the opposite relationship, which is to say that the probability of transition increases the more leftwing the parties in government (by 70% across the range of the score). For the Environment, Agriculture and Justice ministries, the effect is not significant. These ministries are typically held by ministers from the same political party (nearly always liberal ministers for Justice, nearly always Christian-Democrats for Agriculture), and so it is possible that the influence of politics on administrative reorganisations within those ministries is less volatile. Overall, however, the patterns show considerable support for H3.

Table 2. Fixed effects logistic regression of units experiencing end transitions.

Regarding the influence of political turnover of the individual executive heading the ministry on the hazard rate of administrative organisations (H1), we found significant effects in 8 of the 12 models (p < 0.05). The direction of the effect can be either positive or negative, indicating that political turnover of the executive heading the ministry may be associated with increasing the probability of entities experiencing transitions or with decreasing this probability, a finding that is partially at odds with the direction we expected. On the one hand, the effects of turnover for Finance, Foreign Affairs, Social Affairs, Defense, and Environment and Housing are all positive and thus in the expected direction. Political turnover of the executive is associated with an increase in the probability that an entity in that ministry experiences a transition. On the other hand, the effects of turnover for Economic Affairs, Education and Culture, and Infrastructure are all negative. In these cases, turnover lowers the probability of transition, perhaps indicating the resilience of the structures in these ministries to political interference. These effects are independent of the effects of the government’s political ideology, however, and in all three of these ministries, a more rightwing government was associated with a higher probability of transition for its entities. For Interior, Health, Agriculture, and Justice, turnover neither raised nor lowered the probability that an entity experienced a transition. It could be that the latter three are somewhat less partisan departments than others, because professional identity (doctors run health policy, farmers run agriculture, jurists run justice) prevails over party politics.

When we turn to results that are specific to a ministry’s policy area (H2), we rely on a shift of the position of the incoming coalition towards a particular policy area or issue. We do not test for policy area effects in the Economic Affairs, Interior, Health, and Finance ministries because we did not identify variables from the Comparative Manifestos Project dataset that were specific and appropriate for those ministries, as indicated above. For the remaining ministries, some policy area-specific results were significant. A positive position of the coalition towards technology and infrastructure raised the likelihood of transitions for existing entities in the Ministry of Infrastructure. Yet, positive positions could also decrease the likelihood of transition. For the Ministry of Education and Culture, a positive culture position lowered the probability that an entity experienced a transition (by 50% across the range of this variable) and resulted in longer durations of existing units. Likewise, for entities in the Ministry of Defense and in the Ministry of Agriculture, a more positive position towards defense and agriculture increased organisational longevity and decreased the likelihood of transition in the respective ministries. The different directions of the policy area findings are thus somewhat puzzling, as a positive position towards an issue may lead to either more administrative reorganisation or to a continuation of existing structures.

Annual unemployment rates as a control variable produce significant results for 6 out of 12 departments: a negative relationship exists between increased unemployment and the likelihood of transitions in the ministries of Interior, Finance, Education, Foreign Affairs, Defense and Infrastructure. This means that in times of higher unemployment, the hazard rate of these specific administrative organisations is lower. Although the results point in the same direction (a negative influence between unemployment and transition hazard), the subset of ministries significantly affected does not represent a group that shares many similarities. The finding does support the argument by Greasley and Hanretty (Citation2016) that governments perhaps hesitate to reorganise the public sector when unemployment, in general, is already on the rise.

The models also controlled for age of administrative units as an independent variable (as a linear term or using more flexible splines), and found a positive result for 11 out of 12 ministries (all departments except Finance). The older the administrative unit, the higher the likelihood that it will soon experience a transition: no liability of newness within administrative organisations.

In terms of model fit, we use heat map statistics to diagnose model misspecification problems (Esarey and Pierce Citation2012). In three of the models (those for Finance, Education and Culture, and Agriculture), the predicted probabilities deviate significantly from the empirical probabilities, indicating that some important factor explaining the dependent variable has been left out of the model. The complexity of structural change within ministries cannot be attributed to major political factors alone. The remaining nine models are well-specified according to this test.

Discussion and conclusion

The main finding in this paper is that the internal structure of public organisations is affected by politics. We may infer that the politics of structural choice does not halt at the boundaries of public organisations, but continues inside public organisations themselves. The ordering of divisions and sub-divisions, as we learned from previous studies on bureaucratic structure, affects the way in which decisions are made in public organisations, what outcomes are likely to be produced, and how organisational agendas are set (Hammond Citation1986, Citation1993; Hong and Park Citation2019). We realise, however, that the transitions that we observe are the transitions that political executives were able to implement. The observed transitions are either implemented with support of the ministerial bureaucracies or in spite of their resistance. Bureaucratic agents have preferences for certain structures themselves and it is likely that the transitions we were able to observe come with (unknown) reform costs. Thus, if we would have had the data to model bureaucratic resistance, we should have expected a moderated effect of political bargaining on the internal structure of administrative agencies.

We have examined in three different ways how politics affect the internal structure of organisations: the effects of party-political turnover of the executive leading a Ministerial department (H1), the effects of party-political policy positions per ministry on intra-organisational structure (H2) and the effects of rightwing ideology of the coalition government on intra-organisational structure (H3). Our findings strongly support H3: it reflects the standard wisdom that since the start of the liberal reform era of the 1980s, rightwing governments were most pursuant of administrative reorganisations. In 8 of 12 ministries under rightwing governments, the probability of a transition increased. Even when there was no political turnover, but simply a continuation of rightwing rule, rightwing government meant a decrease in the number of units within these eight ministries. The decrease was either caused through disbanding, merging, or privatising units within the ministry. The downsizing occurred in ministries with large spending portfolios, such as Health Care, Social Affairs, Defense, Infrastructure, and Interior Affairs. Not all ministries that experienced a decrease in units under rightwing governments are spending departments though, rightwing rule also affected the Ministries of Foreign Affairs, Economic Affairs and Finance.

Second, our findings support hypothesis one, that political change, measured as a turnover between successive ministers representing different political parties with different ideological positions, too has an effect on the internal structure of public organisations. Though our results are robust they are less conclusive than in the case of political ideology. We have an almost equal share of ministries for which turnover has a positive, negative and no effect. Only four out of the seven ministries for which we found a significant effect of turnover experience increased probabilities of transition as a consequence of turnover: the ministries of Foreign Affairs, Social Affairs, Environment and Housing, and Defense. Whereas the findings on the former four ministries are in the expected direction, turnover significantly decreases the probability of transition at three other ministries: Economic Affairs, Education and Culture and Infrastructure. This mixed finding is puzzling, especially since ministries, by design and location, are not protected against the effects of turnover. Ministries and their sub-divisions are not insulated and their units can be terminated by executive decree. To understand why turnover decreases the odds of transition requires further analysis, thereby focusing on the specific (sub)divisions within the relevant ministries: why did some change and others not?

Finally, particular policy positions of the coalition (H2) matter too for the internal structure of ministries, but here the findings are multi-faceted. We find groups of ministries for which a positive position towards the (expansion of) the policy either increases or decreases the odds of transitions; and there is a group of ministries for which the policy position has no significant effect. In combination with the left–right ideological position of the government and the change of domain-specific policy positions, we can make certain interesting inferences. We find that Environment and Housing and Infrastructure are ministries where the probabilities for transitions have increased under governments that are rightwing and have positive policy positions as regards environment and housing and infrastructure, respectively. By the same token, the odds for transition at Defense increase under rightwing governments but decrease under governments with a positive position vis-à-vis defense. In other words, sometimes the effect of liberal ideology dominates, sometimes instead it is the effect of the policy preferences with respect to a specific domain that dominates.

Overall, we can infer that political variables have a strong impact on the internal structure and organisation of ministries. The results for the effect of the policy positions are robust for six out of eight Ministries. Except for the left–right position of the government, we find no clear pattern for how precisely politics affect the structural design of public organisations. Ministries experience significant effect of executive turnover, sometimes increasing the hazards of intra-organisational transitions and sometimes increasing stability. There are also ministries where we find no effect. Ergo, minister can substantially re-arrange their organisations in line with their policy preferences but do not necessarily do so. This, we believe, brings us to the caveats of our current study – and the points that we need to delve into deeper in future projects.

First, although they are from the same organisational genus, ministries present a disparate group of public organisations due to their portfolios. Each ministry operates in a different environment and the variation between ministries’ environment is substantial. Ministries for example differ in terms of the nature and number of stakeholders, complexity of technology, internationalisation, and political salience of the issue.

Second, ministries are holding companies (Hood and Dunsire Citation1981) as each contains divisions that may address very different kinds of policy issues. The structure and organisation of ministries is the outcome of partisan bargaining between potential coalition partners. The final outcomes of the bargaining process are more reflective of compromises instead of a rational allocation of policy areas. This means that ministries may harbour wide-ranging policy areas with substantially different political logics.

Third, we only looked at party-political variables and have not taken into account that bureaucratic politics may also to a large extent account for the intra-organisation design and distribution of (sub)divisions. Bureaucratic interests, budget allocations, and the role of bureau chiefs therein is very important and can go quite against party-political preferences (see Boin et al. Citation2017; Van Witteloostuijn et al. Citation2018). Turf and bureau-shaping politics have not been accounted for in our models.

Given the key importance of organisational structure for the realisation of political ambitions outlined in the introduction, we argue that looking into intra-organisational transitions will yield rich insights. We have detected meaningful patterns that could be related further to critical junctures in the organisation’s policy environment, to outcomes of coalition bargaining and to the power of bureau chiefs. International comparison is furthermore imperative to see if these patterns hold across different types of political and administrative systems (Kuipers et al. Citation2018). This study indicates that the study of the central government apparatus needs to include what lies beneath.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1.1 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sanneke Kuipers

Sanneke Kuipers is Associate Professor at Leiden University’s Institute of Security and Global Affairs, Faculty of Governance and Global Affairs. She teaches and publishes on crisis management, accountability, comparative politics, and organisational survival. She is chief editor of Risk, Hazards and Crisis in Public Policy (Wiley) and associate editor of the Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Crisis Analysis (OUP).

Kutsal Yesilkagit

Kutsal Yesilkagit is Professor at Leiden University’s Institute of Public Administration, Faculty of Governance and Global Affairs. He teaches and publishes on politics of bureaucracy, international governance, and regulatory governance. His articles have appeared in the Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, Public Administration, Governance and the Journal of European Public Policy, among others.

Brendan Carroll

Brendan J. Carroll is Assistant Professor at Leiden University’s Institute of Public Administration, Faculty of Governance and Global Affairs. He teaches and publishes on comparative public policy, structures of EU and national governance, and interest group advocacy/lobbying. His articles have appeared in the British Journal of Political Science, European Journal of Political Research and Public Organization Review, among others.

Notes

1 Excluded were the Ministry of Generic Affairs because structural transitions within this ministry could not be related to political preferences, and the Ministry of Culture which existed only as a separate entity between 1980-1982.

2 Additional details about the construction of this dataset can be found in the codebook, available on request from the authors.

3 The pooling of all transitions may thus lead to an overestimate of the overall degree of administrative change. While this affects the descriptive overview, its effect on the multivariate analyses is more limited because the overestimation should be consistent across ministries.

5 ‘Per###’ refers to Comparative Manifestos Project variable codes.

6 From 2010, environment and housing are absorbed by infrastructure.

7 From 2010, agriculture is absorbed by economic affairs.

References

- Agterbosch, S., W. Vermeulen, and P. Glasbergen (2004). ‘Implementation of Wind Energy in the Netherlands: The Importance of the Social-Institutional Setting’, Energy Policy, 32:18, 2049–66.

- Andeweg, R. B. (2000). ‘Ministers as Double Agents? The Delegation Process between Cabinet and Ministers’, European Journal of Political Research, 37:3, 377–95.

- Aucoin, P. (1986). ‘Organizational Change in the Machinery of the Canadian Government: From Rational Management to Brokerage Politics’, Canadian Journal of Political Science, 19:1, 3–27.

- Beck, N., J. Katz, and R. Tucker (1998). ‘Taking Time Seriously: Time-Series-Cross-Section Analysis with a Binary Dependent Variable’, American Journal of Political Science, 42:4, 1260–88.

- Bertelli, A., and J. Sinclair (2018). ‘Democratic Accountability and the Politics of Mass Administrative Reorganization’, British Journal of Political Science, 48:3, 691–711.

- Bertels, J., and L. Schulze-Gabrechten (2020). ‘Mapping the Black Box of Intraministerial Organization: An Analytical Approach to Explore Structural Diversity Below the Portfolio Level’, Governance.

- Boin, A., S. Kuipers, and M. Steenbergen (2010). ‘The Life and Death of Public Organizations: A Question of Design?’Governance, 23:3, 385–410.

- Boin, A., C. Kofman, J. Kuilman, S. Kuipers, and A. van Witteloostuijn (2017). ‘Does Organizational Adaptation Really Matter? How Mission Change Affects the Survival of US Federal Independent Agencies, 1933–2011’, Governance, 30:4, 663–86.

- Bouckaert, G., B. G. Peters, and K. Verhoest (2010). The Coordination of Public Sector Organizations: Shifting Patterns of Public Management. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Court of Audit (2015). Energiebeleid: Op Weg naar Samenhang, Terugblik op Tien Jaar Rekenkamer Onderzoek naar Energiebeleid [Energy Policy Towards Cohesion: Reflection on Ten Years Court of Audit Studies on Energy Policy]. The Hague: SDU.

- Davis, G., P. Weller, E. Craswell, and S. Eggins (1999). ‘What Drives Machinery of Government Change? Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom, 1950–1997’, Public Administration, 77:1, 7–50.

- Ministry of Economic Affairs. (1995). Derde Energie Nota [Third Energy Memo]. The Hague: SDU.

- Druckman, J. N., and P. V. Warwick (2005). ‘The Missing Piece: Measuring Portfolio Salience in Western European Parliamentary Democracies’, European Journal of Political Research, 44:1, 17–42.

- Efron, B. (1988). ‘Logistic Regression, Survival Analysis, and the Kaplan-Meier Curve’, Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83:402, 414–25.

- Ekkers, P., and J. K. Helderman (2010). Van Volkshuisvesting naar Woonbeleid [From Housing to Living Policy]. The Hague: SDU.

- Esarey, J., and A. Pierce (2012). ‘Assessing Fit Quality and Testing for Misspecification in Binary-Dependent Variable Models’, Political Analysis, 20:4, 480–500.

- Götz, A., F. Grotz, and T. Weber (2018). ‘Party Government and Administrative Reform: Evidence from the German Lander’, Administration & Society, 50:6, 778–811.

- Greasley, S., and C. Hanretty (2016). ‘Credibility and Agency Termination under Parliamentarism’, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 26:1, 159–73.

- Hammond, T. H. (1986). ‘Agenda Control, Organizational Structure, and Bureaucratic Politics’, American Journal of Political Science, 30:2, 379–420.

- Hammond, T. H. (1993). ‘Toward a General Theory of Hierarchy: Books, Bureaucrats, Basketball Tournaments, and the Administrative Structure of the Nation State’, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 3:1, 120–45.

- Hong, S., and N. Park (2019). ‘Administrative Reorganization as a Signal: Bounded Rationality, Agency Merger, and Salience of Policy Issues’, Governance, 32:3, 421–39.

- Hood, C., and A. Dunsire (1981). Bureaumetrics: The Quantitative Comparison of British Central Government Agencies. Westmead: Gower.

- James, O., N. Petrovsky, A. Moseley, and G. A. Boyne (2016). ‘The Politics of Agency Death: Ministers and the Survival of Government Agencies in a Parliamentary System’, British Journal of Political Science, 46:4, 763–84.

- Kuipers, S., K. Yesilkagit, and B. Carroll (2018). ‘Coming to Terms with Termination of Public Organizations’, Public Organization Review, 18:2, 263–78.

- Laegreid, P., V. Rolland, P. G. Roness, and J.-E. Agotnes (2010). ‘The Structural Anatomy of the Norwegian State 1985–2017’, in P. Laegreid and K. Verhoest (eds.), Governance of Public Sector Organizations. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 21–43.

- Laver, M., and K. A. Shepsle (1994). Cabinet Ministers and Parliamentary Government. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lewis, D. E. (2002). ‘The Politics of Agency Termination: Confronting the Myth of Agency Immortality’, The Journal of Politics, 64:1, 89–107.

- Lichtmannegger, C. (2019). ‘Task Environment Matters for Intraministerial Change: The Interaction of International Environment, Organizational and Opportunity Factors’, International Journal of Public Administration, 42:4, 320–33.

- MacCarthaigh, M. (2014). ‘Agency Termination in Ireland: Culls and Bonfires, or Life after Death?’ Public Administration, 92:4, 1017–37.

- Moe, T. M. (1995). ‘The Politics of Structural Choice: Toward a Theory of Public Bureaucracy’, in O. E. Williamson (ed.), Organisation Theory: From Chester Barnard to the Present and Beyond (exp. ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press, 116–53.

- Mölder, M. (2016). ‘The Validity of the RILE Left-Right Index as a Measure of Party Policy’, Party Politics, 22:1, 37–48.

- Mortensen, P. B., and C. Green-Pedersen (2015). ‘Institutional Effects of Changes in Political Attention: Explaining Organizational Changes in the Top Bureaucracy’, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 25:1, 165–89.

- Ngwa, J. S., H. J. Cabral, D. M. Cheng, M. J. Pencina, D. R. Gagnon, M. P. LaValley, and L. A. Cupples (2016). ‘A Comparison of Time Dependent Cox Regression, Pooled Logistic Regression and Cross Sectional Pooling with Simulations and an Application to the Framingham Heart Study’, BMC Medical Research Methodology, 16:1, 148–59.

- O’Leary, C. (2015). ‘Agency Termination in the UK: What Explains the ‘Bonfire of the Quangos?’ West European Politics, 38:6, 1327–44.

- Pollitt, C. (1984). Manipulating the Machine: Changing the Pattern of Ministerial Departments 1960–1983. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- Pollitt, C., and G. Bouckaert (2011). Public Management Reform a Comparative Analysis: New Public Management, Governance, and the Neo-Weberian State (3rd ed.). Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press.

- Sieberer, U., T. Meyer, H. Bäck, A. Ceron, A. Falcó-Gimeno, I. Guinaudeau, and T. Persson (2019). ‘The Political Dynamics of Portfolio Design in European Democracies’, British Journal of Political Science, 1–16.

- Thies, M. F. (2001). ‘Keeping Tab on Others. The Logic of Delegation in Coalition Governments’, American Journal of Political Science, 45:3, 580–96.

- Tosun, J. (2018). ‘Investigating Ministry Names for Comparative Policy Analysis: Lessons from Energy Governance’, Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis, 20:3, 324–35.

- Van Witteloostuijn, A., A. Boin, C. Kofman, J. Kuilman, and S. Kuipers (2018). ‘Explaining the Survival of Public Organizations: Applying Density Dependence Theory to a Population of US Federal Agencies’, Public Administration, 96:4, 633–50.

- White, A., and P. Dunleavy (2010). Making and Breaking Whitehall Departments: A Guide to Machinery of Government Changes. London: Institute for Government, LSE Public Policy Group.