Abstract

One of the purported effects of international integration is that voters are less able, or less willing, to punish or reward incumbents for economic performance: since governments are less able to influence economic outcomes, economic considerations weigh less for voters at the ballot box. This would have serious implications for democratic legitimacy. Yet the balancing demands hypothesis predicts that voters compensate for this by judging incumbents on non-economic performance instead. In this article, this theory is critiqued theoretically and empirically, putting it to the test for one of the first times at the individual level using the 2019 Belgian Election Study. Combining perceptions of policy performance across six issue areas with novel survey items which measure perceptions of economic constraints, it is shown that whilst performance voting does occur, there is no support for the balancing demands hypothesis. Voting based on performance in economic or non-economic areas remains largely unrelated to perceptions of international constraints.

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at: https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.1953850 .

The interdependence of nation states poses a legitimacy dilemma for democratic governance: as integration deepens, governors are torn between responsiveness to the electorate and responsibility to international commitments with other states and international organisations (Ezrow and Hellwig Citation2014; Mair Citation2013; Rodrik Citation2011). This dilemma is not new (Easton Citation1965; Gourevitch Citation1978), but has grown with greater interdependence and the politicisation of issues such as sovereignty and European integration. Perhaps one of the most consequential and studied aspects of this is how greater integration affects elections and voting behaviour (Kayser Citation2007; Le Gall, Citation2017). In this article, we critique and provide a novel empirical test one of the core hypotheses of the link between integration and voting behaviour – the balancing demands hypothesis – using original data from the 2019 Belgian Election Study (Walgrave et al. Citation2020).

One of the core theories of international integration and domestic politics is the ‘room to manoeuvre’ (RTM) theory, which posits that greater integration reduces the RTM governments have over (economic) policy, with widespread consequences for democratic politics (Hellwig Citation2014b). With respect to voting behaviour, research indicates that external constraints from both globalisation and European integration reduce turnout (Marshall and Fisher Citation2015; Steiner Citation2010, Citation2016; Turnbull-Dugarte Citation2020) by diminishing the belief that who’s in power makes a difference (Vowles Citation2008) and by decreasing political choice via party convergence (Steiner and Martin Citation2012), eventually weakening party responsiveness (Ezrow and Hellwig Citation2014; though see Devine and Ibenskas, Citation2021). Second, there is evidence that the limitation of the economic room to manoeuvre also weakens the extent of the economic vote (Costa Lobo and Lewis-Beck Citation2012; Duch and Stevenson Citation2008; Fernández-Albertos Citation2006; Hellwig Citation2014b; Hellwig and Samuels Citation2007; Le Gall Citation2018). According to this line of argument, voters adapt to the loss of economic leeway of governments on economic policy by judging incumbents less on economic performance. Assuming voters’ electoral preferences are shaped by their governments’ performance and perceived competences (Green and Jennings Citation2017), such a conclusion is pessimistic for the normative consequences of integration. However, when a ballot is cast, it is argued that voters compensate for the loss of national governments’ RTM on economic policy by shifting to judgements on non-economic issues, on which national governments have greater control: this is the balancing demands hypothesis (Hellwig Citation2008, Citation2014a, Citation2014b). Put another way, given a lack of voter agency in shaping economic outcomes, we might expect voters to seek to fill this void by anchoring their choices at the ballot box in non-economic policy dimensions over which states are still able to enact policy output with fewer international commitments.

To provide a concrete example, consider two Belgian citizens going to the polls on the 2019 federal election day. Both view economic and immigration performances as equally important when judging the record of the incumbent government. Yet, voter 1 considers the Belgian government to be constrained in its economic margins of manoeuvre by globalisation and the EU, while voter 2 believes that the EU and globalisation do not reduce her government’s leeway in the economy. Assuming government performance plays some role in vote choice and that both voters behave instrumentally, the balancing demands hypothesis would predict that these two voters differ in the way they punish or reward the incumbent government on those two records: the former will still vote based on economic performance, while the latter will vote less on economic performance and more on immigration, since accountability is arguably conditional on (perceived) responsibility (Duch and Stevenson Citation2010). Clearly, this is important if one believes that governments should be accountable for performance or if performance judgements are relevant for understanding vote choice.

Yet, this analysis can be contended on theoretical and empirical grounds. Theoretically, it logically entails the argument that if voters perceive the economy as performing poorly but that this is due to forces outside of the government’s control, they will not punish the incumbent and instead judge them on alternative bases. However, there are also reasons to believe that voters will not simply exit, but rather voice their discontent with the economy, conditional on voting. Indeed, it seems equally likely that voters will instead vote for change or opt for alternative parties rallying against economic constraints, illustrated by the surge of populist parties across Europe in which sovereignty is a core element of their programme (Halikiopoulou et al. Citation2012). Empirically, this theoretical concern is supported by several studies. For instance, Dassonneville and Hooghe (Citation2017) show how electoral volatility increases with economic distress and that the effect of the economy on volatility is increasing, despite objective economic constraints increasing, particularly in Southern Europe. In a similar vein, Kosmidis (Citation2018) experimentally manipulates the level of ‘room to manoeuvre’ in a survey experiment in Greece and shows that economic voting does not decrease with greater room to manoeuvre.

Despite the hypothesis about the effects of economic constraints on performance voting being a central prediction in the literature on the effects of international integration on political behaviour, existing studies are limited to studying the strength of the economic vote rather than how voters compensate for the supposed loss of efficacy. In addition, the balancing demands hypothesis has been tested almost exclusively with aggregate level data, while no research has examined whether individuals’ perceptions of constraints stemming from international integration matter when judging incumbents on their performance in non-economic policy areas. In line with Steiner (Citation2016), we believe that it is fundamental to complement the existing evidence by analysing the mechanisms on the individual level since the association between constraints from economic integration and performance voting must necessarily be rooted in the thoughts and actions of voters.

As such, this article addresses these gaps and extends the literature on the impact of economic constraints on voting behaviour by asking whether, and how much, voters reward or punish incumbents based on policy performance, using original data fielded in the Belgian Election Study 2019. We directly test the two key implications of the balancing demands hypothesis: that with greater perceptions of constrained room to manoeuvre with regards to the economy, voters 1) reduce economic performance voting and 2) increase non-economic performance voting. In doing so, we fill three gaps within the literature. As mentioned, existing research has tested this either using aggregate measures of globalisation or estimating the effects of perceived constraints on party-citizens congruence; here, we use direct measures of voters’ perceptions using novel survey items fielded in the 2019 EOS Belgian Election Study. This is the only survey which provides information on perceptions of external constraints stemming from globalisation and European integration, and perceptions of performance in different economic policy domains. Second, we extend the literature to a new case, specifically Belgium. The balancing demands hypothesis is one that requires a cast ballot; in Belgium, almost all citizens cast a vote, since it is compulsory. This, combined with the openness of Belgium to European and global markets, makes it an interesting case to test this hypothesis. Third, we extend the test to new policy areas. Whilst Hellwig (Citation2014b) addresses healthcare and immigration, we extend this and include performance in more economic areas (poverty, unemployment, and debt) as well as non-economic areas (the environment, burglaries, and asylum).

In line with existing individual-level studies on the room to manoeuvre and economic voting (e.g. Kosmidis Citation2018), our empirical results broadly reject the balancing demands hypothesis. We do not find that the impact of perceived performance on incumbent voting varies across perceptions of constraint, regardless of whether it is an economic or non-economic issue; where it does, it is not in the direction that the theory predicts. In other words, the effect of perceived performance in non-economic policy is no larger for those who perceive a great degree of constraint than those who perceive none; and the effect of perceived performance in economic policy is no weaker for those same people. We therefore reject a key hypothesis of the room to manoeuvre literature.

This article is organised as follows. In the first section, we discuss performance voting, the literature on economic constraints and voting, and provide an explicit model of the balancing demands hypothesis. We then present the research design and results. We conclude by discussing the wider relevance of the findings for the literature on international integration and political behaviour.

Literature review: economic constraints and performance voting

Economic constraints

More integration, perceived or otherwise, provides a hurdle for citizens’ ability or willingness to vote based on performance. In the words of Duch and Stevenson (Citation2008: 106): ‘An incumbent who is not perceived by the voter as having competency for economic outcomes should neither be rewarded for a good economy, nor punished for poor economic outcomes.’ There are two mechanisms hypothesised in the literature through which this occurs. First, voters could perceive this directly. For instance, Duch and Stevenson (Citation2008) develop and test a formal model of a ‘competency signal’, which indicates how much policy variation can be attributed to an incumbent. Essentially, as integration into the international economy grows, voters can discern less of a competency signal, and voting based on economic performance decreases.

Alongside voters perceiving the level of constraint directly, it has also been posed that voters react to political parties’ cues on a given issue when forming their vote. Parties may strategically avoid issues, removing the track record of an incumbent from the agenda of a campaign and therefore from individual voting decisions. The evidence for this comes from studies which show that economic integration has a clear negative impact on the emphasis of economic issues by political parties (Nanou and Dorussen Citation2013; Ward et al. Citation2015). Ultimately, if parties choose not to compete on the economic dimension, the importance of that dimension may be reduced come election day (see Steiner Citation2016). Indeed, the depoliticisation of economic issues is one potential reason for the politicisation of cultural issues (for instance, Mair Citation2013).

The theoretical argument that integration reduces economic performance voting has been studied and well-supported (Costa Lobo and Lewis-Beck Citation2012; Fernández-Albertos Citation2006; Hellwig Citation2008; Hellwig and Samuels Citation2007; Hellwig Citation2014b; but see: Kosmidis Citation2018). Hellwig (Citation2001), in a seminal study, finds a negative relationship between the level of trade exchange and the economic vote. This result was further corroborated by Hellwig and Samuels (Citation2007) in a larger comparative analysis utilising data from 75 countries over 27 years which indicated that the size of international trade as part of a country’s gross domestic product and exposure to transnational trade flows weakens the economic vote. Many studies have subsequently confirmed this trend at the aggregate level (Fernández-Albertos Citation2006; Giuliani Citation2019; Hellwig Citation2014a, Citation2014b). In contrast, however, fewer studies have investigated the impact of perceptions of economic constraints on the economic vote – or related political attitudes (e.g. Devine Citation2021) – at the individual level. Hellwig (Citation2008) shows that citizens who perceive their national governments to be constrained on the economy are less inclined to punish or reward their incumbents for economic performance in a study focussing on the 2001 British and 1997 French general elections. Similarly, Costa Lobo and Lewis-Beck (Citation2012) find that individual perceptions of the responsibility of the European Union for the situation of the domestic economy negatively affects the extent to which voters punish or reward incumbents in Italy, Greece, Portugal and Spain in 2009. Finally, Le Gall (Citation2018) also provides evidence that lower perceived responsibility of the EU over economic conditions moderates the extent of the economic vote. Worth noting here is that these studies rely on responsibility attribution, a proxy for economic constraints that this article overcomes by using direct measures. The hypothesis has, however, also been challenged. Dassonneville and Lewis-Beck (Citation2019) find the economic vote to be stable over time in national elections in a study across several European societies. Most importantly, Kosmidis (Citation2018) does not support the hypothesis that the economic vote decreases as room-to-manoeuvre decreases in a survey experiment in Greece. Still, overall, the literature expects that as perceived or real integration deepens, voting based on economic performance decreases, whilst the mechanisms which link the two are somewhat understudied.

The balancing demands hypothesis

Overall, this provides a pessimistic view of democratic legitimacy under international integration: political accountability for policy outcomes is weakened with greater openness. However, the balancing demands hypothesis asserts that economic integration increases individuals’ weight on governmental policy actions in the non-economic area (Hellwig Citation2014a), eventually increasing the role of non-economic issues in the calculus of voting (Hellwig Citation2008, Citation2014b) and thus offsetting the legitimacy dilemma – voters failing to judge incumbents on performance – posed by international integration. Voters are assumed to demand less in terms of economic responses, while they should compensate ‘for reduced demands for government action in the economy by increasing demands for attention in other, non-economic areas’ (Hellwig Citation2014a: 5). As a result, if voters participate in elections, they should react to the loss of economic policy competences of national governments not only by voting less on economic issues, but also by voting more on non-economic issues.

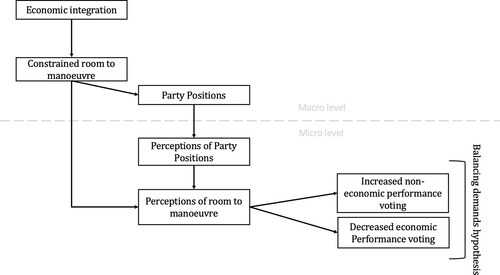

The causal mechanisms linking the growth of non-economic performance voting is the same as the decline in economic performance voting. First, it could be the direct perception of the loss of control, as in Duch and Stevenson (Citation2008). Second, it may be driven by political elites: political parties, even incumbents, emphasising non-economic issues that they can control over economic issues which they cannot. Hence, citizens’ perceptions of economic integration – whether driven by the actual perception of economic constraints or party cues – should increase the importance of non-economic performance in the calculus of voting. We outline this theoretical model in , in which we summarise the links discussed in these sections.Footnote1 This article tests the final set of arrows, between perceptions of the room to manoeuvre and performance voting.

So far, the balancing demands hypothesis has only been tested in three studies. Using data from the 2006 International Social Survey Programme’s (ISSP) Survey, Hellwig (Citation2014a) demonstrates that individual preferences for government actions are moderated by the extent of economic integration. This analysis indicates that citizens’ preferences for government provision of non-economic policies increase with indicators of international economic integration, specifically the KOF index (Gygli et al. Citation2019). Conversely, demands for more involvement in the economy decrease as economic integration deepens. In addition, Hellwig (Citation2014b: 76–95) finds that the electoral effect of evaluations of performance in immigration and healthcare areas are greater in more integrated economies in a cross-sectional analysis covering 28 countries in 2009. In contrast to these studies which use aggregate indicators of economic integration, a study in Britain and France focuses instead on the effects of constraint perceptions on performance voting in non-economic issues (Hellwig Citation2008). This study examines the effect of individual perceptions of national governments’ economic constraints on party-voter congruence in non-economic issues, i.e. a libertarian-authoritarian index and positioning on European integration. In both cases, the author finds that voters who believe their national governments to be constrained in their economic choices by economic globalisation tend to be closer to the parties on the libertarian-authoritarian axis than voters who think the opposite (Hellwig Citation2008).

The previous study (Hellwig Citation2008) uses party-citizen congruence to assess the hypothesis rather than voting specifically, though it does use direct measures of voter perceptions; yet, we believe that the analysis we perform here is a necessary step for the theory, since we must establish that voting based on perceived performance also increases across perceptions of constraint. Indeed, aggregate studies are more likely to lead to methodological problems of observational equivalence and ecological fallacy, while party-citizens congruence does not directly reflect performance voting at the individual level. Thus, our fundamental contribution is to test this core hypothesis in a new context with direct measures of perceptions of both constraints and performance voting at the individual level.

To be clear, we specify the two expectations of the balancing demands hypothesis that we are testing below. To reiterate, it expects voters who perceive their government to be constrained to be more likely to punish or reward incumbents on non-economic issues. Formally, this results in the following two hypotheses:

Balancing demands hypothesis 1: The more a citizen believes the national government to be constrained on the economy, the more prone she will be to reward or punish the incumbent government on its record in non-economic policies

Balancing demands hypothesis 2: The more a citizen believes the national government to be constrained on the economy, the less prone she will be to reward or punish the incumbent government on its record in economic policies

Research design

We use the 2019 EOS – Belgian Election Study (Walgrave et al. Citation2020)Footnote2 – to test these hypotheses at the individual level. This post-election survey was fielded between the 29th of May and the 30th of June, shortly after the 2019 federal elections in Belgium on the 26th of May. The election resulted in the loss of votes for mainstream parties (liberals, socialists and Christian-democrats) that has been a feature of elections across Europe since the Eurozone crisis, with far-right parties gaining in Flanders (Vlaams Belang) and left-wing and communist parties gaining in Wallonia (PTB-PVDA). More broadly, the electoral defeat of the four parties that were part of the federal government incumbent parties (N-VA, CD&V, Open VLD and MR) was patent and this led to a fragmented party system, with a chasm between Flanders and Francophone Belgium. Given this rupture, it took the COVID-19 crisis for government formation, leaving the country without government until March 2020.

Issue-wise, the election revolved around three main topics: employment, the environment, and immigration (for a thorough review, see: Pilet Citation2021). Socio-economic issues were particularly salient in Wallonia. In contrast, issues of identity and immigration were the most salient issues in Flanders, particularly following the tensions between the ruling coalition regarding the UN Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (also referred to as the UN Marrakech Pact). Those disagreements led the Prime minister, Charles Michel, to resign in December 2018 and the N-VA to be excluded from the minority caretaker government that was composed of MR, CD&V and Open VLD before the 2019 elections. Finally, the climate was an important topic during the campaign, since the election was conducted on the heels of the ‘climate marches’ with several large demonstrations calling for more ambition in fighting climate change from November 2018 to May 2019. As we will go on to discuss, our measures of policy areas adequately capture these differing concerns between the two regions and the key salient issues, and we deal with these differences by separating Wallonia and Flanders in the analysis.

More prosaically, however, the 2019 EOS dataset is the only one that provides a direct survey item on perceptions of external constraints – globalisation and European integration – as well as perceptions of performance in different non-economic policy domains, such as the environment, security and immigration. This means that there is no other available dataset that we can use to test these hypotheses so specifically. Whilst there are some parallels with the European Election Studies of 2009 and 2014 which ask about responsibility judgements in several policy areas in 2009 and the economy in 2014, this is limited for our purposes by being European elections, which are not expected to have the same dynamics as domestic elections.

Dependent variable

The aim of this article is to assess whether performance voting in national elections is moderated by perceptions of economic constraints. The model of performance voting starts from a simple assumption: that the minimal requirement for democratic accountability is that voters’ electoral choices are at least in part based on the past record of the governors. Consequently, the dependent variable used in this study is whether respondents reported to have voted for the incumbent. Hence, the dependent variable is a dichotomous variable, in which 1 identifies all the respondents who report to have voted for the incumbents – MR in Wallonia; CD&V, N-VA and Open VLD (Coalition) in Flanders – and where 0 identifies those who reported voting for any of the other parties. Approximately 43% of our sample reports having voted for the Coalition (Flemish incumbent) and 14% having voted for MR (Walloon incumbent). The specific question is: ‘For which party did you vote for the Chamber during the national elections on the 26th of May 2019?’

Independent variables

Our key explanatory variables are perceptions of performance in specific policy areas. We have three indicators for non-economic policies: perceptions of performance in security, environment and immigration – explicitly non-economic issues, unlike those used in previous studies (such as pensions) which entail greater direct economic costs. These are retrospective performance judgements. When studying performance voting, the retrospective approach is the most sensible since it is at the core of the theoretical assumption of the model: voters reward or punish incumbent governments based on their past policy record on election day. In practice, empirical studies have mostly relied on retrospective and sociotropic perceptions of policy performance to assess performance voting (Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier, Citation2013; Nannestad and Paldam Citation1994; Plescia and Kritzinger Citation2018). That said, the balancing demand hypothesis can also be adapted to prospective voting according to Hellwig (Citation2014b). Indeed, there is no reason to believe that (perceived) economic constraints should affect retrospective voting, but not how voters choose parties based on their assessments of the future economic and non-economic conditions. However, the EOS dataset only provides measures of retrospective performance and, thus, does not allow us to test the effect of perceived economic constraints on prospective voting.Footnote3

It is not easy to clearly differentiate between what can be conceptualised as an economic issue and what can be conceptualised as a non-economic issue: there are only few issues that can be defined as purely non-economic, in the sense that they are budget neutral. Stated differently, almost all policies must be funded to achieve their purpose. However, some issues are more closely related to economic frames than others. Environment, immigration and security constitute good case studies to test the balancing demands hypothesis, though we acknowledge that addressing them will entail some economic cost and benefit.

In order to test H2, we also include economic issues pertaining to debt, unemployment, and poverty. In this study, we use questions which are worded as follows: ‘Many social problems may be assessed using numbers. Below we ask you your opinion on six of these problems. In your estimation, to what extent has each of these social problems decreased or increased during the previous period of government? 1) The number of people in Flanders/Wallonia/Brussels living in poverty 2) The unemployment rate in Flanders/Wallonia/Brussels 3) CO2 emissions in Belgium 4) The number of approved requests for asylum in Belgium 5) The number of home burglaries in Flanders/Wallonia/Brussels 6) The Belgian public debt’. The response scale is 5-points from ‘strongly decreased’ to ‘strongly increased’. The correlation between these variables is between 23% (poverty and asylum) and 45% (asylum and burglaries), which supports our assertion that these are seen as different frames, with a lower correlation between economic and non-economic areas than within.

Our other key explanatory variables are the degree to which respondents believe that their national governments are constrained by the processes of European integration and economic globalisation. This dataset is the only one in which respondents were asked to assess this alongside other key variables. More precisely, we benefit from two original questions on constraints stemming from European integration and globalisation, which are worded as follows: ‘To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statement? ‘The European Union gives enough leeway to the Belgian Government in the economic field’Footnote4 and ‘To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statement?’ ‘Globalisation gives enough leeway to the Belgian Government in the economic field’. Both questions have a five-point response scale, from ‘totally disagree’ to ‘totally agree’. An important clarification here is that whilst the European Union can certainly be seen as playing a role in non-economic issues such as asylum and immigration, we specify in the question ‘economic field’, narrowing our focus to the specific balancing demands hypothesis. We return to this in the conclusion. A second clarification is that we do not directly consider the mechanism of how respondents ended up with this attitude – for instance, direct perception or through party competition over the issue(s). We do not see this as an issue as our intention is not to isolate the mechanism but whether the balancing demands hypothesis occurs at all.

Control variables

We control for basic demographics in gender and age, indicators of an individual’s position in the labour market through education, and income; and two attitudinal variables: left-right self-placement and levels of satisfaction with democracy. We theoretically defend including these variables and provide a full codebook in the Online Appendix instead of the main text. Descriptive statistics for our variables are presented in (key variables) and (control variables).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics: key variables.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics: control variables.

Empirical strategy

The empirical strategy proceeds in two steps. First, we investigate whether retrospective perceptions of performance affect incumbents’ fortunes; in other words, we test whether performance voting exists in the first place to establish our benchmark and the validity of the measures. Hence, we run logistic models including incumbent vote choice as a dependent variable, our battery of control variables, and our main explanatory variables.

In the next step, we include interaction terms to see whether perceptions of economic constraints affect performance voting in general elections: this answers whether the effect of performance voting depends on the level of perceived constraint, as the balancing demands hypothesis predicts.

We present the results in the form of marginal effects. For the interactions, these are marginal effects at representative values (MERs). Models include robust standard errors and are not weighted. To save space, we present only figures and our variables of interest; full tables are available in the Online Appendix. As will be clear, the effects differ between Wallonia and Flanders, and so we separate our results by region; we present identical figures pooling the sample, with region fixed effects, in the Online Appendix.

Performance voting in 2019 federal elections

The effect of performance on incumbent voting

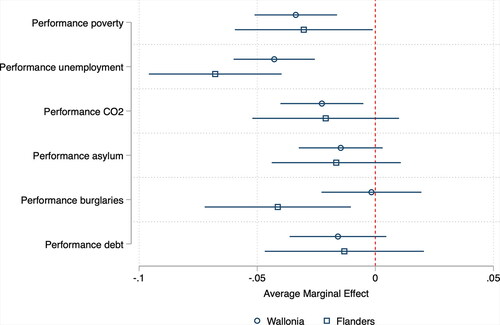

First, we turn to the effect of perceived performance on incumbent voting to establish that performance voting does indeed occur. Following the logistic regression as described above, the average marginal effects (AMEs) of perceived performance are displayed in . This describes the expected change in the probability of voting for the incumbent for a change in the chosen predictor (in this case, perceived performance in each policy field). As noted, these models include a full battery of controls and our explanatory variables, including the perceived constraint variables.

The results show the existence of performance voting in unemployment and poverty in the case of both Wallonia and Flanders. In Flanders, performance in managing burglaries is a significant predictor, whilst environmental management – Co2 emissions – has a significant effect in Flanders. What this means is that if the respondent believes that unemployment has increased, for instance, they are approximately 5 percentage points less likely to vote for the incumbent. Considering this is a five-point scale, the full possibility is an effect size of 20 percentage points from one end of the scale to the other. In the case of Co2 emissions, respondents in Flanders are 3 percentage points less likely to vote for the incumbent the more they believe Co2 emissions have increased.

Overall, there is strong evidence of performance voting in the 2019 federal elections for most policy areas, except for asylum claims and debt. Burglaries and Co2 emissions have different levels of significance in the two Belgian regions. Whilst economic performance has the strongest effect, non-economic policy performance also influences the vote. This indicates that at this election, voters were on average responding as expected to perceived performance with a greater focus on economic performance.

Testing the moderating effect of perceived constraint

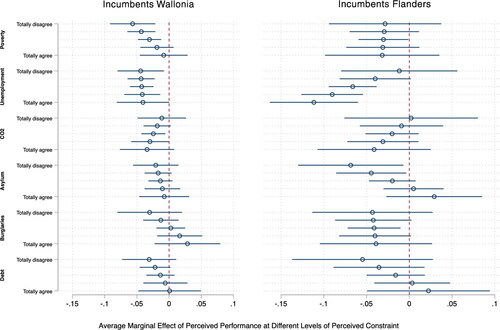

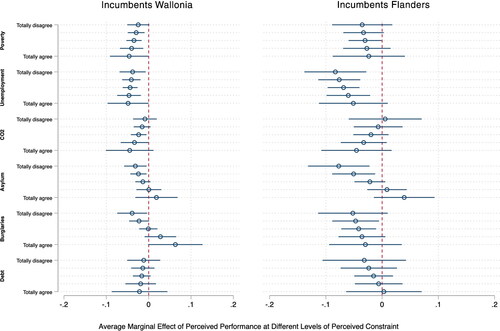

Next, we turn to our main hypotheses of interest: does the strength of non-economic performance voting increase as perceived international constraints increase? Conversely, does the strength of economic performance voting decrease as perceived international constraints increase? As discussed, this ‘balancing demands’ hypothesis is a key hypothesis from the room to manoeuvre literature. We run the same logistic regression as before, except now include an interaction term in the model. We present the marginal effects of performance voting at different levels of perceived constraint (therefore making them MERs) in (for globalisation) and (for the EU). These show the marginal effects on the X-axis; on the Y-axis, the level of perceived constraint grouped by policy area. We present the results for Wallonia and Flanders on the left and right respectively.

Figure 3. Performance voting under perceived constraints from globalisation (95% confidence intervals).

Figure 4. Performance voting under perceived constraints from the European Union (95% confidence intervals).

Recall that the question to measure constraint here is whether respondents believe that the government has enough ‘leeway’ in economic policy in the face of economic globalisation or European integration. As such, we would expect a greater effect of economic policy perceptions on the probability of incumbent voting as we move from ‘totally disagree’ to ‘totally agree’ and the reverse for non-economic policy areas (i.e. a greater effect as we move from ‘totally agree’ to ‘totally disagree’). Beginning with , we observe that the expected effect on economic policy only stands regarding unemployment in Flanders, with a large effect size; the reverse is the case for poverty in Wallonia; and in the two others there is no change. For non-economic policy, we observe the expected effect only regarding asylum in Flanders. Overall, this provides very limited support for the hypothesis, and much more against it.

Turning to perceptions of constraint imposed by European integration, the problems are much the same. We do not observe any significant change with regard to economic policy, and indeed the opposite effect with unemployment in Flanders. Regarding non-economic policy, we again find very limited support for the hypothesis. Only asylum in Flanders and burglaries in Wallonia do we note a statistically significant change.

Perhaps more importantly, comparing these effects to the performance voting models without interactions shows much the same effects. In other words, the perceptions of constraint add very little to our understanding of how people weigh different issues at the ballot box, which is precisely the expectation of the balancing demands hypothesis. Whilst there is some support, we find just as much support for the opposite effect. As such, our findings echo the experimental findings from Kosmidis (Citation2018) in Greece in a very different methodological and substantive setting.

It may be argued that one aspect of the theory also pertains to issue salience, and this is something we have not considered: it may be that salience also decreases as perceived constraint increases, or that there may be some interaction. Unfortunately, we cannot test salience directly, as there is no suitable question in the dataset. Our overview of the context of Belgian elections, however, suggests that at the very least climate and asylum were salient in Flanders and unemployment in Wallonia. Salience does not seem to change the results. Whilst asylum (Flanders) fits the model’s expectations, asylum and unemployment do not. To attempt to address this empirically, we also repeat the analysis separating the sample into those with high interest and those with low interest in politics. First, we might expect that those with high interest will be more aware of both party competition and more likely to receive ‘competency signals’ (Duch and Stevenson Citation2008) than those with low interest, simply through paying greater attention. Second, we may expect that those individuals adjust their saliency judgements in reaction to this. As a result, this provides a reasonable approximation. We present the results in the Online Appendix, but they are consistent with the presented results and do not change our conclusions.

Finally, we recognise that our case here has drawbacks as well as positives. Whilst we cannot extend the number of our cases since the question of interest was only fielded in Belgium, we approximate our results using the European Election Study (EES) 2009. This dataset includes responsibility attribution between the EU and respondents’ member state and performance perceptions across a number of economic and non-economic policy areas. Whilst responsibility attribution is not an ideal measure of constraint, these variables have been used by other authors to study similar questions (Costa Lobo and Lewis-Beck Citation2012; Devine Citation2021; Le Gall Citation2018, Citation2019). We thus repeat our analysis here on a pooled sample of 26 countries (N = 19788). Controlling for sex, age, education, class, left-right ideology, partisanship, and country fixed effects, the results reaffirm our conclusions that whilst there is performance voting, it does not increase or decrease depending on perceptions of constraints. We are cautious to draw too much from this broader analysis, but it does offer some generalisation of the results presented here in a different time, place, and using different measures.

Discussion

The integration of nation states alters the dynamics of domestic mass politics. In this article, we have focussed on the effect of integration on voting behaviour, specifically how voters weigh the performance of incumbents in determining their vote choice at election time. We have extended the literature on the impact of economic integration on voting behaviour on the individual level by addressing a fundamental yet overlooked hypothesis (Costa Lobo and Lewis-Beck Citation2012; Hellwig Citation2014b; Steiner Citation2016). The balancing demands hypothesis predicts that under conditions of economic constraint, voters, knowingly or otherwise, reduce their reliance on economic performance and increase the importance of performance in non-economic policy. Evidence on this question has been limited to a handful of studies and only one at the individual level. We have argued that there are theoretical reasons to doubt this hypothesis, and empirically tested it in a new setting with direct measures of perceptions of constraint with respect to both globalisation and European integration. We have shown that there is little evidence for this hypothesis in this case. The effect of perceived performance in non-economic policy does not increase with greater perceived constraints from globalisation or the EU; nor does the effect of perceived economic performance weaken. The exception is in asylum claims.

This is a fundamental problem for the theory if the results are replicated elsewhere. Although we do not reject the effect of economic integration on other aspects of mass politics, we do consider it a necessary condition that we observe that citizens both perceive these constraints, and this carries through to their behaviour at the ballot box or correlates with other relevant attitudes. We have, however, contributed to a literature which has so far failed to confirm that this is the case (Devine Citation2021; Kosmidis Citation2014, Citation2018), though it does seem to affect turnout (e.g. Steiner Citation2016). This suggests that there is some discrepancy between the aggregate level studies and individual level studies which needs to be explored, since studies which rely on either observational measures of individual perceptions (Devine Citation2021) or experimentally manipulated perceptions of the room to manoeuvre (Jensen and Rosas Citation2020; Kosmidis Citation2018) have not provided support for the individual-level mechanisms which purportedly link greater integration with individuals’ attitudes or behaviour. That said, this is potentially more positive for considerations of democratic accountability than it is for academic knowledge. Incumbents are still held to account, even if they are perceived to have less efficacy. This is bad news for incumbents, but it is good news for those who hope citizens hold political actors accountable for political outcomes.

This begs the question of why we find these null results. The theory tested here predicts a clear relationship: as perceptions of constraints increase, performance voting decreases in the constrained area and increases in the areas with greater leeway. Yet this requires two steps: individuals perceive those constraints and then link that to a lack of government power. We propose nuancing both steps. First, it matters whether elites politicise the issue. If we assume that elites – by which we mean political actors, media leaders, and so on – play a role in shaping public opinion (Zaller Citation1992; for specifically on international issues, Guisinger and Saunders Citation2017), elite emphasis and polarisation over the issue of constraints should increase those who hold any perceptions at all and their salience in moderating performance voting. Second, we must recognise that perceptions of constraints are not value-free. As Hay and Smith (Citation2005) have argued, discourses of integration can vary from those that are negative and a threat to sovereignty, to those constraints which are changeable, and those that should be defended. Though not directly providing evidence for this, Kosmidis (Citation2014) has shown that under extreme external constraints such as experienced by Greece under Troika conditionality, economic voting can actually increase: voters blame the domestic government for being in that position in the first place. To summarise, an alternative theoretical explanation, and one consistent with the null results presented here, does not presume the direct, negative consequences of exogenous constraints to mass politics. Instead, it emphasises elite emphasis and polarisation over constraints (i.e. the relative influence of the domestic and international levels) and the articulation of what this means for domestic political power. This also accommodates the issue of salience noted previously.

A more parsimonious argument might point instead to heterogeneity caused by individuals’ attributes such as interest, knowledge and ideology. Whilst we have provided evidence for one of these (interest), it is possible that there are others we have not tested. Ultimately, we don’t see this as an issue for testing the balancing demands hypothesis precisely because it does not itself posit these interactive effects and finding them would not provide clear evidence either way. For instance, if there was an interaction with ideology, such that those on the right of the spectrum do comply with the model, this only begs the question of why those with different political ideologies react differently to the same level of constraint. And this brings us back to the theoretical argument in the previous paragraph.

A final limitation to address more extensively is that the analysis is in Belgium, a country in which incumbent voting may be distorted by strong federalism, different issue priorities in Wallonia and Flanders, and by the specific context of the changing ruling coalition at the dawn of the 2019 elections. Moreover, whilst we believe compulsory voting provides benefits, it also has the potential to distort the theory. Namely, because voters are forced to make a choice, they may rely on economic cues even though they don’t believe the government has made a difference. This would lead to null results that do not extend to non-compulsory systems. That said, we do not think this is the only conclusion: it is quite possible that those who are forced to vote rely on the most salient cues, which the theory (and empirical evidence) would suggest would be non-economic. Second, whilst high interest individuals do comply with the theory marginally more than low interest individuals, this still does not provide strong evidence for the theory. This is important since high interest individuals are likely to have voted if it was not compulsory.

Nonetheless, we recognise that the unique Belgian system may mean our results only apply to that system, and so have also provided an approximate replication of our results using the European Election Study 2009, which at least broadens our case for rejecting the balancing demands hypothesis. Finally worth mentioning is that integration impacts non-economic policy areas too, which we would not dispute. However, it is precisely the claim of the balancing demands hypothesis that non-economic policy judgements are affected differently (and oppositely) to economic policy judgements. That we do not find this is the case is precisely a problem the theory must deal with. Despite these limitations, we have addressed more policy areas than previous research, and those that can be considered salient at an election time (such as crime, immigration, the environment, and poverty). Given the growing evidence of the weaknesses presented here, it is perhaps time to move to greater theorising about mass politics under international integration. We think a future promising path to follow is to adopt an elite-led model of public opinion in which the focus is on elite polarisation of international integration and how the bargaining process between domestic and international levels is articulated.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1.2 MB)Acknowledgements

The authors would first like to thank Patrick Van Erkel and Stefaan Walgrave, the members of the EOS research project, and especially Virginie Van Ingelgom, for including questions on perceived constraints and allowing us to use the dataset. Furthermore, the authors would like to thank Ruth Dassoneville, Philipp Harfst, Silke Goubin, Isabelle Guinaudeau, Morgan Le Corre-Juratic, Arndt Leininger, Raul Magni-Berton and the members of the CEE at UCLouvain, and the two helpful and benevolent anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions and comments. Finally, the authors would also like to specifically thank Virginie Van Ingelgom and Claire Dupuy for their support and for helping this research go through.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Cal Le Gall

Cal Le Gall is a postdoctoral researcher in the DeVOTE project funded by the ERC at the University of Vienna. He was previously a postdoctoral researcher in the Qualidem project funded by the ERC and the GLOBPOL project funded by the F.R.S.–FNRS at University of Louvain, projects in the framework of which this research was done. He studies political attitudes and voting behaviour, particularly relating to globalisation and European integration. His work has been published in journals such as European Journal of Political Research, Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties and French Politics. [Email: [email protected]]

Daniel Devine

Daniel Devine is a Career Development Fellow in Politics at St Hilda’s College, University of Oxford. He studies public opinion, particularly relating to political trust, policy preferences and voting. His work has been published in journals such as European Union Politics, Journal of European Public Policy and British Journal of Political Science. [Email: [email protected]]

Notes

1 This is adapted from Steiner (Citation2016) and Devine (Citation2021).

2 The 2019 Belgian Election Study was launched in the framework of the EOS research project RepResent, which is led by Antwerp University, and includes teams from VUB, KULeuven, UCLouvain, and ULB. We would like to thank the members of the EOS research project and the Antwerp University team in particular, i.e., Patrick Van Erkel and Stefaan Walgrave, for letting us include questions on perceived constraints and use the dataset quickly (Walgrave et al. Citation2020)

3 In the Online Appendix, we also included an analysis of the conditional effect of perceived government/EU responsibility on economic prospective voting using the 2009 European Election Study dataset (see Tables 6 and 7).

4 The correlation between this question and the item for whether the respondent thinks that EU integration has gone too far (0) or should go further (10) is .46, indicating that whilst the variables are of course correlated, they are not functions of each other: we are not (only) picking up preferences on integration.

References

- Costa Lobo, Marina, and Michael S. Lewis-Beck (2012). ‘The Integration Hypothesis: How the European Union Shapes Economic Voting’, Electoral Studies, 31:3, 522–8.

- Dassonneville, Ruth, and Marc Hooghe (2017). ‘Economic Indicators and Electoral Volatility: Economic Effects on Electoral Volatility in Western Europe, 1950–2013’, Comparative European Politics, 15:6, 919–43.

- Dassonneville, Ruth, and Michael S. Lewis-Beck (2019). ‘A Changing Economic Vote in Western Europe? Long-Term vs. short-Term Forces’, European Political Science Review, 11:1, 91–108.

- Devine, Daniel (2021). ‘Perceived Government Autonomy, Economic Evaluations, and Political Support during the Eurozone Crisis’, West European Politics, 44:2, 229–52.

- Devine, Daniel, and Raimondas Ibenskas (2021). ‘From Convergence to Congruence: European Integration and Citizen-Elite Congruence’, European Union Politics. Retrieved from https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/14651165211024936

- Devine, Raymond M., and Randolph Stevenson (2008). The Economic Vote: How Political and Economic Institutions Condition Election Results. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Duch, Raymond M., and Randolph Stevenson (2010). ‘The Global Economy, Competency, and the Economic Vote’, The Journal of Politics, 72:1, 105–23.

- Easton, David (1965). A Framework for Political Analysis. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

- Ezrow, Lawrence, and Timothy Hellwig (2014). ‘Responding to Voters or Responding to Markets? Political Parties and Public Opinion in an Era of Globalization’, International Studies Quarterly, 58:4, 816–27.

- Fernández-Albertos, Jose (2006). ‘Does Internationalisation Blur Responsibility? Economic Voting and Economic Openness in 15 European Countries’, West European Politics, 29:1, 28–46.

- Giuliani, Marco (2019). ‘Economic Vote and Globalization before and during the Great Recession’, Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 1–20. Retrieved from https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2019.1697881

- Gourevitch, Peter (1978). ‘The Second Image Reversed: The International Sources of Domestic Politics’, International Organization, 32:4, 881–912.

- Green, Jane, and Will Jennings (2017). The Politics of Competence Parties: Public Opinion and Voters. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Guisinger, Alexandra, and Elizabeth M. Saunders (2017). ‘Mapping the Boundaries of Elite Cues: How Elites Shape Mass Opinion across International Issues’, International Studies Quarterly, 61:2, 425–41.

- Gygli, Savina, Florian Haelg, Niklas Potrafke, and Jan-Egbert Sturm (2019). ‘The KOF Globalisation Index – Revisited’, The Review of International Organizations, 14:3, 543–74.

- Halikiopoulou, Daphne, Kyriaki Nanou, and Sofia Vasilopoulou (2012). ‘The Paradox of Nationalism: The Common Denominator of Radical Right and Radical Left Euroscepticism: The Paradox of Nationalism’, European Journal of Political Research, 51:4, 504–39.

- Hay, Colin, and Nicola Smith (2005). ‘Horses for Courses? The Political Discourse of Globalisation and European Integration in the UK and Ireland’, West European Politics, 28:1, 124–58.

- Hellwig, Timothy (2001). ‘Interdependence, Government Constraints, and Economic Voting’, The Journal of Politics, 70:4, 1141–62.

- Hellwig, Timothy (2008). ‘Globalization, Policy Constraints, and Vote Choice’, The Journal of Politics, 70:4, 1128–41.

- Hellwig, Timothy (2014a). ‘Balancing Demands: The World Economy and the Composition of Policy Preferences’, The Journal of Politics, 76:1, 1–14.

- Hellwig, Timothy (2014b). Globalization and Mass Politics: Retaining the Room to Manoeuvre. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Hellwig, Timothy, and David Samuels (2007). ‘Voting in Open Economies: The Electoral Consequences of Globalization’, Comparative Political Studies, 40:3, 283–306.

- Jensen, Nathan M., and Guillermo Rosas (2020). ‘Open for Politics? Globalization, Economic Growth, and Responsibility Attribution’, Journal of Experimental Political Science, 7:2, 89–100.

- Kayser, Mark A. (2007). ‘How Domestic is Domestic Politics? Globalization and Elections’, Annual Review of Political Science, 10:1, 341–62.

- Kosmidis, Spyros (2014). ‘Government Constraints and Accountability: Economic Voting in Greece before and during the IMF Intervention’, West European Politics, 37:5, 1136–55.

- Kosmidis, Spyros (2018). ‘International Constraints and Electoral Decisions: Does the Room to Maneuver Attenuate Economic Voting?’, American Journal of Political Science, 62:3, 519–34.

- Le Gall, Cal (2017). ‘How (European) Economic Integration Affects Domestic Electoral Politics? A Review of the Literature’, French Politics, 15:3, 371–17.

- Le Gall, Cal (2018). ‘Does European Economic Integration Affect Electoral Turnout and Economic Voting?’, Politique Européenne, N° 62:4, 34–79.

- Le Gall, Cal (2019). ‘EU Authority, Politicization and EU Issue Voting’, Politique Européenne, N°64:2, 32–55.

- Lewis-Beck, Michael S., and Mary Stegmaier (2013). ‘The VP-Function Revisited: A Survey of the Literature on Vote and Popularity Functions after over 40 Years’, Public Choice, 157:3–4, 367–85.

- Mair, Peter (2013). Ruling the Void: The Hollowing of Western Democracy. London: Verso Books.

- Marshall, John, and Stephen D. Fisher (2015). ‘Compensation or Constraint? How Different Dimensions of Economic Globalization Affect Government Spending and Electoral Turnout’, British Journal of Political Science, 45:2, 353–89.

- Nannestad, Peter, and Martin Paldam (1994). ‘The vp-Function: A Survey of the Literature on Vote and Popularity Functions after 25 Years’, Public Choice, 79:3–4, 213–45.

- Nanou, Kyriaki, and Han Dorussen (2013). ‘European Integration and Electoral Democracy: How the European Union Constrains Party Competition in the Member States’, European Journal of Political Research, 52:1, 71–92.

- Pilet, Jean-Benoît (2021). ‘Hard Times for Governing Parties: The 2019 Federal Elections in Belgium’, West European Politics, 44:2, 439–49.

- Plescia, Carolina, and Sylvia Kritzinger (2018). ‘Credit or Debit? The Effect of Issue Ownership on Retrospective Economic Voting’, Acta Politica, 53:2, 248–68.

- Rodrik, Dani (2011). The Globalization Paradox: Democracy and the Future of the World Economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Steiner, Nils D. (2010). ‘Economic Globalization and Voter Turnout in Established Democracies’, Electoral Studies, 29:3, 444–59.

- Steiner, Nils D. (2016). ‘Economic Globalisation, the Perceived Room to Manoeuvre of National Governments, and Electoral Participation: Evidence from the 2001 British General Election’, Electoral Studies, 41, 118–28.

- Steiner, Nils D., and Christian W. Martin (2012). ‘Economic Integration, Party Polarisation and Electoral Turnout’, West European Politics, 35:2, 238–65.

- Turnbull-Dugarte, Stuart J. (2020). ‘Why Vote When You Cannot Choose? EU Intervention and Political Participation in Times of Constraint’, European Union Politics, 21:3, 406–28.

- Vowles, Jack (2008). ‘Does Globalization Affect Public Perceptions of ‘Who in Power Can Make a Difference’? Evidence from 40 Countries, 1996–2006’, Electoral Studies, 27:1, 63–76.

- Walgrave, Stefan, Patrick van Erkel, Isaia Jennart, Karen Celis, Kris Deschouwer, Sofie Marien, Jean-Benoît Pilet, Benoît Rihoux, Emilie Van Haute, Virginie Van Ingelgom, Pierr Baudewyns, Anna Kern, and Jonas Lefevere (2020). ‘RepResent Longitudinal and Cross-Sectional Electoral Survey 2019’, DANS. Retrieved from https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17026/dansxe8-7t78

- Ward, Dalston, Jeong Hyun Kim, Matthew Graham, and Magrit Tavits (2015). ‘How Economic Integration Affects Party Issue Emphases’, Comparative Political Studies, 48:10, 1227–59.

- Zaller, John (1992). The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press