Abstract

Although populist radical right-wing parties (PRRPs) are regarded as male-dominated, many have in recent years expanded their female electorate and reduced their electoral gender gap. Studies explain this trend as the result of a conscious strategy to target female voters through representation. This strategy is applied in both the descriptive and substantial realms, as PRRPs appoint female leaders and adopt relatively more progressive stances on gender, while still holding conservative, family-centred positions. However, the central question of whether and which of these strategies explain the closing gender gap in the populist vote has not yet been thoroughly comparatively examined. To answer this question, this study uses conditional logit models to explore the relationship between descriptive and substantial representation and women’s vote for a PRRP. The results show that a higher convergence between voter and PRRP positions on gender equality increases female votes for the PRRP. However, female descriptive representation does not prove relevant to explaining women’s vote for PRRPs. This has important implications for the literature on female representation in general, and women’s vote for PRRPs in particular.

Populist radical right-wing parties (PRRPs) have become an important political force in Europe, where they, in many countries, constitute a large proportion of the parliament or participate in government. Despite their electoral success, PRRPs have traditionally struggled to attract female voters (see Snipes and Mudde Citation2020). Research has suggested that the PRRP gender gap is the result of women having less favourable views of the parties’ perceived discriminatory policies and prejudice towards minorities (Hansen Citation2019; Harteveld et al. Citation2015; Harteveld and Ivarsflaten Citation2018). In recent years, PRRPs have however begun to close their electoral gender gap—even achieving parity in some countries (Mayer Citation2015; Snipes and Mudde Citation2020).

Scholars have explained this trend by highlighting the parties’ attempts to better represent female voters in both substantial and descriptive terms (Mudde Citation2007: 9). Substantially, gender issues have become a salient part of PRRP ideologies, though these parties largely maintained their conservative and family-centred gender positions (e.g. Bernardez-Rodal et al. Citation2022; Ennser-Jedenastik Citation2022; Heinisch and Werner Citation2019; Kantola and Lombardo Citation2019, Citation2021; Mudde Citation2007; Spierings et al. Citation2015). Descriptively, PRRPs have sought to improve their representation of the female electorate by strategically promoting female leaders—the most emblematic case being that of Marie Le Pen, the leader of the National Rally (formerly the National Front) in France (Ben‐Shitrit et al. Citation2022; Mayer Citation2015; Snipes and Mudde Citation2020).

Studies on the efforts of PRRPs to reach the female electorate have suggested that their strategies have been relatively successful (Allen and Goodman Citation2021; Ben‐Shitrit et al. Citation2022; Campbell and Erzeel Citation2018; Lancaster Citation2020). However, these studies have two important weaknesses. First, they focus on either the supply or the demand side, rather than understanding the voting choice as a function of the relationship between parties’ and voters’ positions (Allen and Goodman (Citation2021) is an exception). It is therefore unclear whether women are indeed voting for PRRPs because they are better represented. Second, research has disregarded that voters’ party choice is conditioned by the options available. Attempts by PRRPs to increase their share of votes from women are impacted by their competitors’ positions on gender equality, and the success of PRRP strategies to better represent women must therefore be considered in relation to the competitor parties. To fill this literature gap, this study uses conditional logit models—also known as choice models—to link party characteristics with individual attitudes and ultimately investigate the degree to which gender representation explains women’s vote for PRRPs. We distinguish two types of representation: descriptive representation—operationalised by female party leadership—and substantive representation—measured by the distance between a party and an individual’s position on gender equality. Our main question is as follows: To what extent do substantive (RQ1) and descriptive (RQ2) representation by PRRPs increase their share of female voters?

We use data from the European Social Survey (ESS9), data on parties’ positions on gender issues from the Chapel Hill Expert Survey, and data on female leadership from the European Institute of Gender Equality for 23 European countries.Footnote1 We contribute to the literature on female voting for PRRPs by measuring the impact of descriptive and substantive representation on the likelihood of a woman voting for a PRRP. After excluding Hungary, which proved to be an influential case, we confirm that substantive representation explains the increase in the female electorate of PRRPs. However, the analyses indicate that descriptive representation is not associated with a higher chance of a woman voting for a PRRP. This finding holds independently of the congruence between party and voter positions on gender equality.

Political representation and the gender gap

Studies have found that women are more likely than men to vote for left-wing parties in both the United States (Barnes and Cassese Citation2017; Kaufmann Citation2006) and Europe (Giger Citation2009). Researchers have attributed this divergence in voting behaviour to differences in how left- and right-wing parties represent women voters (Barnes and Cassese Citation2017) with respect to two forms of female political representation: substantive representation and descriptive representation.

Substantive representation reflects the extent to which party representatives’ activities and policies respond to their voters’ concerns (Pitkin Citation1967). Studies have shown that social cleavages, such as class or the rural-urban divide, are more relevant than gender in explaining variation in voters’ policy preferences. Nonetheless, a voter’s gender is the main predictor of their policy preferences regarding equality-related issues, such as childcare, reproductive rights, sexual violence, and gender quotas (Htun and Weldon Citation2010; Kaufmann and Petrocik Citation1999). In particular, the literature has reported that gender equality has become a salient cultural issue among women (Inglehart and Norris Citation2003), and the gender ideology of parties is an important predictor of voting choice (Campbell and Erzeel Citation2018; Paxton and Kunovich Citation2003). Thus, political actors need to consider women’s preferences regarding gender issues to ensure their substantive representation.

The second type of representation considered is descriptive representation, which refers to the preference of voters to prefer candidates from their own social group (Bergh and Bjørklund Citation2011; Teney et al. Citation2010). This trend suggests that female voters favour female candidates and parties in which women occupy leadership positions (Banducci and Karp Citation2000). Some studies have reported that the link between higher visibility of women in political parties and a rise in female votes results from expectations that this heightened visibility will improve substantive representation (Plutzer and Zipp Citation1996). Gender is associated with different experiences of social reality (see Wängnerud Citation2009); therefore, voters expect female politicians to be better situated to respond to female voters’ concerns (Mansbridge Citation1999). In line with this, studies have found that women are more likely to vote for a female leader only when that candidate is perceived as holding a feminist attitude (Campbell and Heath Citation2017; Giger et al. Citation2014).

Notably, these ideas of female representation and voting were developed to explain the dynamics of mainstream parties. The next section discusses the particularities of the PRRP gender ideology to formulate hypotheses on how substantial and descriptive representation explain women’s vote for PRRPs.

Gender in the agendas of radical right-wing parties

The literature has defined populism as a ‘thin-centred’ ideology that separates society into two antagonistic and homogeneous groups—the ‘pure people’ and the ‘corrupt elite’—and argues that politics should be an expression of the ‘general will’ of the people (Mudde Citation2004). Because populism is a thin-centred ideology, it always appears in combination with other ideologies, such as authoritarianism and nativism in the case of PRRPs.

By understanding the general will of ‘the people’ to be homogenous, early research on populism has considered gender ideology to be secondary or irrelevant for PRRPs. Yet, according to recent studies, PRRPs have developed a distinctive and increasingly salient gender ideology (see Akkerman Citation2015; Erzeel and Rashkova Citation2017; Mudde and Kaltwasser Citation2015). While such gender ideology varies by cultural setting (e.g. de Lange and Mügge Citation2015; Erzeel and Rashkova Citation2017; Mudde Citation2007), it has three main recurrent features. First, PRRPs reject a gender equal society because they view gender inequality as ‘natural’, and an egalitarian society contradicts their fundamental belief structure (de Lange and Mügge Citation2015: 64). Second, PRRPs directly associate women’s issues and politics with family politics (Mudde Citation2007: 92). They do not question the traditional approach to the family; as wives and mothers, women are located within the home and are subordinate to men (Pettersson Citation2017). This approach has social policy implications in that social benefits are designed for male breadwinners, which leaves women primarily responsible for childcare (Ennser-Jedenastik Citation2022; Mudde Citation2007; Mudde and Kaltwasser Citation2015: 29). Finally, because women give birth, they need protection (Mudde Citation2007). In summary, PRRPs advocate for clearly distinct gender roles. Studies have demonstrated that this view is held mainly by men who believe that greater gender equality would diminish their own status (Coffé Citation2018; Ralph-Morrow Citation2022).

Scholars have also identified a ‘double standard’ or ‘dual problem’ in the gender ideology of PRRPs, as issues of gender are framed differently in the context of immigration (Mudde and Kaltwasser Citation2015; Pettersson Citation2017; Spierings and Zaslove Citation2015). On the one hand, PRRPs want to promote a traditional image of the family in contrast to a progressive, egalitarian notion of gender (Mudde and Kaltwasser Citation2015); on the other hand, gender issues are ‘instrumentalised’ in connection with immigration, as PRRPs claim that Islam threatens female emancipation as a national norm (Mudde and Kaltwasser Citation2015). By using the narrative that ‘other’ cultures are less progressive and not as compliant with Western values, PRRPs emphasise the need to protect ‘the people’—and especially women (Akkerman Citation2015; de Lange and Mügge Citation2015; Mudde and Kaltwasser Citation2015; Pettersson Citation2017).

As part of their opposition to the cultures they describe as ‘illiberal’, some PRRPs have selectively adopted progressive stances on gender equality. For instance, in the Netherlands, the Party for Freedom has rejected the image of ‘traditional’ women and instead promotes a ‘modern’ vision of gender, which includes female participation in the workforce. The Party for Freedom has also started to advocate for LGBTQ + rights (de Lange and Mügge Citation2015). In France, Marie Le Pen (National Rally) has embraced secularism in opposition to multiculturalism and, accordingly, has defended women’s right to abortion (Scrinzi Citation2017). Thus, rather than maintaining a consistently traditional position on gender issues, PRRP gender ideology is highly variable and may include elements of gender equality positions in response to non-Western perspectives of gender roles. These ideological moves are not merely cosmetic, as recent studies have shown that PRRPs have, in some cases, paradoxically implemented policies that improve gender equality (Erzeel and Rashkova Citation2017; Rashkova Citation2021).

We expect female voters to ‘read’ the varying positions of PRRPs on gender equality and prefer parties that more closely represent their own policy preferences. We hypothesise that, as in the case of mainstream parties, party-voter congruence on gender equality will explain women’s vote for a PRRP. We operationalise the congruence between individual and party positions on gender equality in terms of (absolute) distance and expect that a smaller distance between voter and party positions on gender equality will correspond to a higher likelihood of a voter choosing a PRRP.

H1: A smaller distance between voter and PRRP positions on gender equality corresponds to a higher chance of a woman voting for the party.

Research has revealed that PRRPs have recruited female politicians and appointed female leaders to ‘soften’ their traditional image of Männerparteien and become more attractive to women (Ben‐Shitrit et al. Citation2022; Snipes and Mudde Citation2020). Studies have also shown that female leaders are perceived as more moderate than male counterparts with similar political positions (O’Brien Citation2019). Thus, we expect that the presence of a female leader will increase the likelihood of a woman voting for a PRRP.

H2: A female leader increases the chance of a woman voting for a PRRP.

In line with the previous studies on mainstream parties, we furthermore anticipate a positive interactive effect between substantive and descriptive representation. In particular, female leadership signifies that a PRRP has modernised their gender ideology and is often presented as an internal ‘rupture’ in the party (Meret and Siim Citation2017). Thus, we expect that female leadership will intensify the positive effect of PRRPs’ moderation on the change of a woman voting for a PRRP.

H3: The positive effect of female leadership on the chance of a woman voting for a PRRP is stronger when the party-voter congruence on gender equality is higher.

Methodology

In order to test our hypotheses, we used conditional logit models. This model is the most appropriate for analysing voting behaviour in multiparty systems because it considers party choice to be dependent on the options available (Alvarez and Nagler Citation1998; Elff Citation2009). Thus, it not only includes information on the party chosen but also evaluates the conditional effect of the characteristics of the competitor parties on voting choice. Studies have shown that, in multiparty systems, voters do not consider all parties available to make their choice, but rather choose from a constrained set of possible options (Oscarsson and Rosema Citation2019; Rekker and Rosema Citation2019). Following previous studies’ findings that PRRPs’ electoral success occurred at the expense of mainstream left- and right-wing parties (Betz Citation1993; Kriesi et al. Citation2008), we constrain the party choice of a potential PRRPs voter to three options: mainstream left-wing, mainstream right-wing, and PRRP.

Admittedly, in highly fragmented political systems, potential PRRPs’ voters consider more than three party options. Nonetheless, we follow this operationalisation to simplify interpretation of the results and to enable cross-country comparison. We thus selected countries’ most successful PRRP and the largest left and right-wing mainstream parties in the election of reference, based on parties’ position on the left-right scale available at Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES).Footnote2 The list of countries and parties included in this study is available in the online appendix. The dependent variable stems from the ESS9 question, ‘For which party did you vote in the last election?’ We consider information only from voters of the three selected parties, which means that the data of the remaining electorate was not included in the analysis. In order to conduct the regression, voters’ information was triplicated to denote all available options, and a dummy variable was included to signal the chosen party.

In conditional logit models, the choice is explained by two types of covariates: individual-specific and choice-specific. The latter varies within the individual depending on the option; thus, it denotes a relationship between the individual and the party choice. We developed two choice-specific covariates to capture the descriptive and substantial dimensions of representation. Female leadership indicates whether the party represents women descriptively by having a female leader. This dimension is operationalised by a binary variable, which assumes a value of 1 if the party has a female party leader or deputy leader. The authors were granted access to this data collected by the European Institute of Gender Equality. We decided to include these two positions because the literature has argued that they are visible and prominent enough to enable identification by female voters and mobilise those voters. Alternative models operationalising descriptive representation by the presence of a female party leader are available in the online appendix. Similar to the results presented here, these find that descriptive representation is not significant in explaining the female vote on PRRPs.

Women’s substantive representation on gender issues is operationalised by the congruence between voter and party preferences regarding gender equality. Parties’ positions on gender issues were obtained from the CHES, and the variable assumes values between 0 and 10. Higher values indicate that a party’s platform opposes gender equality. Importantly, this variable reflects a broader perspective of gender equality that includes the party’s approach to both women’s rights and LGBTQ + rights. Due to the absence of a more precise measure of individual position on gender equality, our variable stems from the ESS9 question on the importance of equal treatment and equal opportunity for all people. This variable assumes values ranging from 1 (very important) to 6 (not important at all). This choice-specific covariate is operationalised by the absolute distance between the normalised individual position on equality and the normalised gender position on gender equality. It thus varies between 0 (complete agreement) and 1 (total disagreement).

On order to match properly individual data and party information, we considered the date of the last election for each country in relation to the period of the survey field work. For instance, in relation to the ESS9 fieldwork, the last Belgian elections were held on May 25, 2014. Thus, we considered the PPRP’s position on gender issues and the presence of a female leader in 2014. However, in Sweden, the last elections took place on September 9, 2018. Therefore, the party data are from 2018. The online appendix provides a complete list of the ESS9 fieldwork and the dates of the last elections by country.

Research has also shown that the ‘losers of globalisation’ (i.e. lower-middle class, less educated, and younger voters) are more likely vote for PRRPs (Betz Citation1993). Moreover, Euroscepticism, traditional values, and negative attitudes towards migrants have been associated with PRRP voting (Ivarsflaten Citation2005; Kitschelt and McGann Citation1997; Mudde Citation2007; Van der Brug and Fennema Citation2007). Nonetheless, Arzheimer and Carter (Citation2009) have suggested that religious affiliation is negatively associated with PRRPs. Therefore, we include a series of control variables to account for those individual characteristics associated with voting for a PRRP. summarises the independent variables used in this study.

Table 1. Independent variables.

As the research focuses on understanding how female descriptive and substantive representation influence women’s vote for a PRRP, we conduct most of our analysis considering only the female electorate. It should be noted that in order to determine how those party characteristics influence the gender gap size, a study considering the male electorate would also be needed. We believe, however, that the presence of a female party leader and party position on gender equality have a lesser influence on male party choice, and it is likely to affect this group through very different mechanisms. Thus, we opt to focus on the effect of representation on women’s party choice.

Descriptive statistics

presents the average and the standard deviation of parties’ positions on gender equality by party family. It also displays the number of parties with a female leader by party family. Fewer PRPPs have female leaders compared to mainstream parties, but the difference is not substantial. Among the 23 parties included in the analyses, there are 10 female leaders in PRRPs, and 12 in the mainstream parties. The most contrasting characteristic concerns the party position on gender equality. The most inegalitarian party family is PRRPs (score: 8.16) followed by right-wing parties (5.13) and left-wing parties (3.27). Our data reflect that PRRPs receive fewer votes than mainstream parties, and the female electorate is less supportive of this party family compared to the male electorate. These results confirm the presence of a gender gap in PRRP voting, though they also indicate that this difference is not as pronounced as previous studies have suggested. Notably, the vote shares displayed in do not correspond to actual electoral results, as they account only for the electorate of those three parties.

Table 2. Descriptive information on party descriptive and substantive representation, by party family.

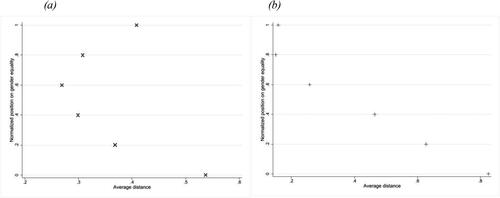

shows how individuals of different positions on gender equality are represented by their chosen parties. It displays the relationship between the individual normalised position on gender equality and the average absolute difference between individuals’ and parties’ positions on gender equality. includes data for the electorate of all parties, while contains data only for PRRPs voters. They reveal that, for the entire electorate, large average distances between voters and parties’ positions occur for voters with low and high levels of preference for equality. Nonetheless, for the PRRP electorate, larger distances appear only for more equalitarian voters, which implies that PRRPs do not properly represent voters with more equalitarian positions.

Statistical analysis

We ran four conditional multinomial regression to model vote choice in a multiparty system. illustrates the effect of individual characteristics on the probability of a voter choosing a right-wing party or PRRP over a left-wing party (the baseline). Model 1 contains data from the entire electorate and includes only individual covariates. Models 2, 3, and 4 focus on the voting choice of female voters and add stepwise choice-specific covariates. Model 2 includes a choice-specific covariate to account for the conditional effect of substantial representation on voting choice. Model 3 includes two choice-specific variables to study the conditional effect of substantive and descriptive representation on voting choice, and Model 4 also includes an interaction effect between substantive and descriptive representation.

According to Model 1, while gender does not explain voting choice between right- and left-wing mainstream parties, the results evidence that a woman is less likely to choose a PRRP over a left-wing party. Model 2 shows that a marginal increase in distance between individual and party positions on gender equality is associated with a decrease in the chance of voting for the party. Model 3 demonstrates that a party having a female leader increases the chance of a woman choosing that party; however, Model 4 reveals that the effect of descriptive representation is moderated by substantial representation.

Before further analysing the results, we ran a sensibility test to verify whether the results are driven by one or a few influential cases. For this test, we re-estimated our models 23 times, and excluded the respondents of one country each time. The results of those regressions, which are available in the online appendix, are stable to the removal of all countries but Hungary. This country has an atypical political system. The PRRPs Fidesz and Jobbik are the nation’s most important parties, whereas the most prominent mainstream left- and right-wing parties accounted for only 17% of votes in the 2018 elections, which led to an unreliable estimation of the effect of female leadership on the chance of a woman voting for a PRRP. Thus, following advice in the literature (Van der Meer et al. Citation2010), we excluded this case from our study.

displays the same models as but without the Hungarian respondents. In line with previous research, Model 5 shows that, in comparison to left-wing voters, PRRP voters are less educated, more religious, have less trust in the European Parliament, have stronger anti-immigration sentiments, and live more comfortably with their current income. They are also older and more right-wing in the economic dimension than left-wing voters. Although gender does not explain voting choice between right- and left-wing mainstream parties, the results indicate that a woman is less likely to choose a PRRP over a left-wing party. The analysis of the predicted probability of PRRP voting by gender reveals that men have around a 19% chance of voting for a PRRP, whereas this likelihood is just 15% among women. These findings confirm the gender gap in PRRP voting, although it is less expressive than earlier studies have suggested (see e.g. Harteveld et al. Citation2015).

Table 3. Results of the regression analysis with the Hungarian case.

Table 4. Results of the regression analysis without the Hungarian case.

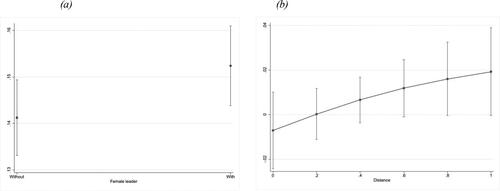

The results of Model 6 lead to similar conclusions as Model 5 regarding the effect of the individual covariates on women’s vote for a PRRP. They also reflect that a marginal increase in distance between individual and party positions on gender equality is associated with a decrease in the chance of voting for this party, which confirms that substantive representation is relevant to explain women’s party choice. illustrates the effect of descriptive representation on the probability of a woman choosing a PRRP. Plot 2(a) depicts the predicted probability of voting for a PRRP for the different distances between voter and party positions on gender equality. This probability is 21% for total congruence and approximately 11% for no congruence, which confirms H1. Plot 2(b) illustrates the effect of a marginal increase in distance between voter and PRRP positions on gender equality on the chance of voting for a PRRP, a left-wing party, and a right-wing party. The decrease in substantive representation of a PRRP corresponds to a 0.09 reduction of the likelihood of a woman voting for this party. Both left- and right-wing mainstream parties benefit from this decrease in PRRP substantive representation, as it increases the probability of women choosing these parties.

Figure 2. (a) Predicted probability of voting for a PRRP for different distance levels and marginal effect of distance between voters and (b) PRRPs’ position on gender equality. (Plot based on Model 6).

Since distance is measured in absolute terms, the direction of change in PRRP positions on gender issues is a priori unknown. Nonetheless, both previous studies and support the interpretation that an increase in congruence between female voters’ and PRRP positions on gender issues is primarily driven by the moderation of PRRP stances on gender equality. Thus, by adopting a more equalitarian position, PRRPs can effectively attract female voters both from mainstream right- and left-wing parties.

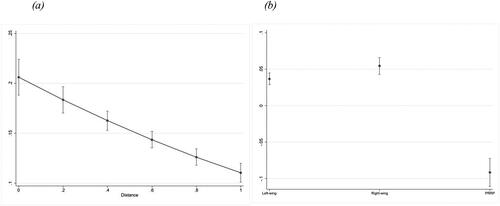

Models 7 and 8 show that, without the Hungarian respondents, female leadership has neither a direct (Model 7) nor indirect (Model 8) effect on women’s party choice. illustrates the effect of a female leader on the change in a woman’s vote for a PRRP. Contrary to H2, Plot 3(a) shows no significant difference between the predicted probability of a woman voting for a PRRP that does or does not have a female leader. Furthermore, in opposition to H3, Plot 3(b) indicates that the marginal effect of female leadership on the chance of a woman voting for a PRRP increases with lower congruence between party and voter positions on gender equality; however, this result is not significantly different from 0.

Discussion and conclusion

PRRPs have in recent years increased their female electorate and begun closing their electoral gender gap. Research has explained this trend by the parties’ attempt to better represent women. This study has used conditional logit regression to investigate how descriptive (female leadership) and substantive representation (congruence between party and voter positions on gender equality) are associated with the likelihood of women voting for PRRPs. This methodology allows us to move beyond previous studies’ limitations by analysing the effect of the two types of representation on women’s vote for PRRPs and considering the voters’ party choice conditional on the available options.

Our preliminary analysis identified Hungary as an influential case that led to an inaccurate estimation of the relevance of a female leader to the chance of a woman voting for a PRRP. Our conclusions are therefore based on an analysis that excludes the respondents from this country. Still, future studies could use this case for theory refinement, as it can illuminate the circumstances under which women vote for female leaders who promote an inegalitarian gender ideology.

The results confirm the existence of a gender gap—albeit small—in the PRRP vote, with women less likely than men to vote for these parties. However, while previous research has found that female leadership has an important role in attracting women’s votes for PRRP, we find that this is, in fact, not the case: descriptive representation does not increase female votes. Moreover, we find no moderating effect between substantive representation and descriptive representation on the probability of women voting for a PRRP. Only substantive representation—measured by the distance between voter and party’s positions on gender equality—proved to be statistically significantly associated with an increase in the chance of a woman voting for a PRRP.

These findings have important implications for the literature on female representation in general, and women’s vote for PRRPs in particular. The absence of a significant effect of female descriptive representation adds to previous studies that conclude that women’s support for female leaders is conditional on candidates’ ideology (e.g. Campbell and Heath Citation2017; Giger et al. Citation2014; Martin Citation2019). One possible reason underlying this result may be that PRRPs view gender inequality as ‘natural’ and advocate for distinct gender roles. Thus, it is plausible that their voters do not ascribe particular importance to the presence of female leadership.

Substantial representation may succeed in attracting these voters as PRRPs’ are adopting selective progressive stances on gender, in particular as a response to a perceived non-Western culture. PRRPs seek to construct their gender positions on the basis of their anti-immigrant appeal, claiming to be the real defenders of women in reaction to stereotypes of gender relations in migrant communities (Pettersson Citation2017). A possible explanation for our results is thus that such a strategy may succeed in appealing to parts of the female electorate. However, more research on PRRP voters’ gender positions is needed to determine whether their attitudes on gender issues match their parties.

Some limitations should be noted. It should be acknowledged that female descriptive representation does not only concern party leadership: literature has noted the importance of the number of female candidates and leadership at the local level as important drivers of female voters. Additionally, due to data unavailability, the measures of individual and party positions on gender equality encompass not only the position on equal rights for women but also equal rights for the LGBTQ + community. Nevertheless, we believe that defending equality for these groups naturally accompanies a more equal position on gender overall, which implies that parties that advocate for women’s equal rights are also pro-LGBTQ + rights.

Despite these limitations, the study at hand uses the best data available to illuminate the relationship between the female vote for PRRPs and party strategies for representing women. By linking individual and party positions on gender equality, we offer an alternative perspective to the top-down tradition of studying the female vote for PRRPs, and we can effectively study women’s responses to changes in substantive and descriptive representation. Moreover, by taking a conditional approach to party choice and considering how the characteristics of competing parties affect the likelihood of a woman voting for a PRRP, we provide a more realistic analysis of the trade-offs that women face in their vote choices.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (381.9 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Juliana Chueri

Juliana Chueri is a postdoctoral researcher at the Swiss Graduate School of Public Administration (IDHEAP), University of Lausanne. She studies the transformation of the welfare state, focussing on the rise of populist radical right-wing parties, immigration and digitalisation. Her recent publications have appeared in journals such as Party Politics and the Journal of European Social Policy. [[email protected]]

Anna Damerow

Anna Damerow holds a master’s degree in International Relations from the University of Leiden. Her research interests include women’s representation in politics and European Union politics. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Croatia Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Great Britain, Hungary, Italy, Latavia, Lithuania, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland.

2 We considered as a left-wing party, meaning a party that scored less than five on the left-right scale, and a right-wing party a party that scored more than five on the left-right scale.

References

- Akkerman, Tjitske (2015). ‘Gender and the Radical Right in Western Europe: A Comparative Analysis of Policy Agendas’, Patterns of Prejudice, 49:1–2, 37–60.

- Allen, Trevor J., and Sara Wallace Goodman (2021). ‘Individual-and Party-Level Determinants of Far-Right Support among Women in Western Europe’, European Political Science Review, 13:2, 135–50.

- Alvarez, R. Michael, and Jonathan Nagler (1998). ‘When Politics and Models Collide: Estimating Models of Multiparty Elections’, American Journal of Political Science, 42:1, 55–96.

- Arzheimer, Kai, and Elisabeth Carter (2009). ‘Christian Religiosity and Voting for West European Radical Right Parties’, West European Politics, 32:5, 985–1011.

- Banducci, Susan A., and Jeffrey A. Karp (2000). ‘Gender, Leadership and Choice in Multiparty Systems’, Political Research Quarterly, 53:4, 815–48.

- Barnes, Tiffany D., and Erin C. Cassese (2017). ‘American Party Women: A Look at the Gender Gap within Parties’, Political Research Quarterly, 70:1, 127–41.

- Ben‐Shitrit, Lihi, Julia Elad‐Strenger, and Sivan Hirsch-Hoefler (2022). ‘“Pinkwashing” the Radical‐Right: Gender and the Mainstreaming of Radical‐Right Policies and Actions’, European Journal of Political Research, 61:1, 86–110.

- Bergh, Johannes, and Tor Bjørklund (2011). ‘The Revival of Group Voting: Explaining the Voting Preferences of Immigrants in Norway’, Political Studies, 59:2, 308–27.

- Bernardez-Rodal, Asuncion, Paula Requeijo Rey, and Yanna G. Franco (2022). ‘Radical Right Parties and Anti-Feminist Speech on Instagram: Vox and the 2019 Spanish General Election’, Party Politics, 28:2, 272–83.

- Betz, Hans-George (1993). ‘The New Politics of Resentment: Radical Right-Wing Populist Parties in Western Europe’, Comparative Politics, 25:4, 413–27.

- Campbell, Rosie, and Silvia Erzeel (2018). ‘Exploring Gender Differences in Support for Rightist Parties: The Role of Party and Gender Ideology’, Politics & Gender, 14:01, 80–105.

- Campbell, Rosie, and Oliver Heath (2017). ‘Do Women Vote for Women Candidates? Attitudes toward Descriptive Representation and Voting Behavior in the 2010 British Election’, Politics & Gender, 13:02, 209–31.

- Coffé, Hilde (2018). ‘Gender and the Radical Right’, in Jens Rydgren (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of the Radical Right. New York: Oxford University Press, 200–11.

- de Lange, Sarah L., and Liza M. Mügge (2015). ‘Gender and Right-Wing Populism in the Low Countries: Ideological Variations across Parties and Time’, Patterns of Prejudice, 49:1–2, 61–80.

- Elff, Martin (2009). ‘Social Divisions, Party Positions, and Electoral Behaviour’, Electoral Studies, 28:2, 297–308.

- Ennser-Jedenastik, Laurenz (2022). ‘The Impact of Radical Right Parties on Family Benefits’, West European Politics, 45:1, 154–76.

- Erzeel, Silvia, and Ekaterina R. Rashkova (2017). ‘Still Men’s Parties? Gender and the Radical Right in Comparative Perspective’, West European Politics, 40:4, 812–20.

- Giger, Nathalie (2009). ‘Towards a Modern Gender Gap in Europe?: A Comparative Analysis of Voting Behavior in 12 Countries’, The Social Science Journal, 46:3, 474–92.

- Giger, Nathalie, Anna M. Holli, Zoe Lefkofridi, and Hanna Wass (2014). ‘The Gender Gap in Same-Gender Voting: The Role of Context’, Electoral Studies, 35, 303–14.

- Hansen, Michael A. (2019). ‘Women and the Radical Right: Exploring Gendered Differences in Vote Choice for Radical Right Parties in Europe’, Österreichische Zeitschrift für Politikwissenschaft, 48:2, 1–21.

- Harteveld, Eelco, and Elisabeth Ivarsflaten (2018). ‘Why Women Avoid the Radical Right: Internalized Norms and Party Reputations’, British Journal of Political Science, 48:2, 369–84.

- Harteveld, Eelco, Wouter Van Der Brug, Stefan Dahlberg, and Andre Kokkonen (2015). ‘The Gender Gap in Populist Radical-Right Voting: Examining the Demand Side in Western and Eastern Europe’, Patterns of Prejudice, 49:1–2, 103–34.

- Heinisch, Reinhard, and Annika Werner (2019). ‘Who do Populist Radical Right Parties Stand for? Representative Claims, Claim Acceptance and Descriptive Representation in the Austrian FPÖ and German AfD’, Representation, 55:4, 475–92.

- Htun, Mala, and S. Laurel Weldon (2010). ‘When do Governments Promote Women's Rights? A Framework for the Comparative Analysis of Sex Equality Policy’, Perspectives on Politics, 8:1, 207–16.

- Inglehart, Ronald, and Pippa Norris (2003). Rising Tide: Gender Equality and Cultural Change around the World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ivarsflaten, Elisabeth (2005). ‘The Vulnerable Populist Right Parties: No Economic Realignment Fuelling Their Electoral Success’, European Journal of Political Research, 44:3, 465–92.

- Kantola, Johanna, and Emanuela Lombardo (2019). ‘Populism and Feminist Politics: The Cases of Finland and Spain’, European Journal of Political Research, 58:4, 1108–28.

- Kantola, Johanna, and Emanuela Lombardo (2021). ‘Strategies of Right Populists in Opposing Gender Equality in a Polarized European Parliament’, International Political Science Review, 42:5, 565–79.

- Kaufmann, Karen M. (2006). ‘The Gender Gap’, PS: Political Science & Politics, 39:03, 447–53.

- Kaufmann, Karen M., and John R. Petrocik (1999). ‘The Changing Politics of American Men: Understanding the Sources of the Gender Gap’, American Journal of Political Science, 43:3, 864–87.

- Kitschelt, Herbert, and Anthony J. McGann (1997). The Radical Right in Western Europe: A Comparative Analysis. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, Edgar Grande, Romain Lachat, Martin Dolezal, Simon Bornschier, and Tobia Frey (2008). West European Politics in the Age of Globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lancaster, Caroline Marie (2020). ‘Not so Radical after All: Ideological Diversity among Radical Right Supporters and Its Implications’, Political Studies, 68:3, 600–16.

- Mansbridge, Jane (1999). ‘Should Blacks Represent Blacks and Women Represent Women? A Contingent "Yes”’, The Journal of Politics, 61:3, 628–57.

- Martin, Danielle Joesten (2019). ‘Playing the Women’s Card: How Women Respond to Female Candidates’ Descriptive versus Substantive Representation’, American Politics Research, 47:3, 549–81.

- Meret, Susi, and Birte Siim (2017). ‘A Janus-Faced Feminism: Gender in Women-Led Right-Wing Populist Parties’, Conference: European Conference on Gender & Politics, Lausanne, Switzerland.

- Mayer, Nonna (2015). ‘The Closing of the Radical Right Gender Gap in France?’, French Politics, 13:4, 391–414.

- Mudde, Cas (2004). ‘The Populist Zeitgeist’, Government and Opposition, 39:4, 541–63.

- Mudde, Cas (2007). Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mudde, Cas, and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser (2015). ‘Vox Populi or Vox Masculini? Populism and Gender in Northern Europe and South America’, Patterns of Prejudice, 49:1–2, 16–36.

- O’Brien, Diana Z. (2019). ‘Female Leaders and Citizens’ Perceptions of Political Parties’, Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 29:4, 465–89.

- Oscarsson, Henrik, and Martin Rosema (2019). ‘Consideration Set Models of Electoral Choice: Theory, Method, and Application’, Electoral Studies, 57, 256–62.

- Paxton, Pamela, and Sheri Kunovich (2003). ‘Women's Political Representation: The Importance of Ideology’, Social Forces, 82:1, 87–113.

- Pettersson, Katarina (2017). ‘Ideological Dilemmas of Female Populist Radical Right Politicians’, European Journal of Women's Studies, 24:1, 7–22.

- Pitkin, Hanna F. (1967). The Concept of Representation. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Plutzer, Eric, and John F. Zipp (1996). ‘Identity Politics, Partisanship, and Voting for Women Candidates’, Public Opinion Quarterly, 60:1, 30–57.

- Ralph-Morrow, Elizabeth (2022). ‘The Right Men: How Masculinity Explains the Radical Right Gender Gap’, Political Studies, 70:1, 26–44.

- Rashkova, Ekaterina R. (2021). ‘Gender Politics and Radical Right Parties: An Examination of Women’s Substantive Representation in Slovakia’, East European Politics and Societies: and Cultures, 35:1, 69–88.

- Rekker, Roderik, and Martin Rosema (2019). ‘How (Often) Do Voters Change Their Consideration Sets?’, Electoral Studies, 57, 284–93.

- Scrinzi, Francesca (2017). ‘A “New” National Front? Gender, Religion, Secularism and the French Populist Radical Right’, in Michaela Köttig, Renate Bitzan, and Andrea Petö (eds.), Gender and Far Right Politics in Europe. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 127–40.

- Snipes, Alexandra, and Cas Mudde (2020). ‘“France's (Kinder, Gentler) Extremist”: Marine Le Pen, Intersectionality, and Media Framing of Female Populist Radical Right Leaders’, Politics & Gender, 16:2, 438–70.

- Spierings, Niels, and Andrej Zaslove (2015). ‘Gendering the Vote for Populist Radical-Right Parties’, Patterns of Prejudice, 49:1–2, 135–62.

- Spierings, Niels, Andrej Zaslove, Liza M. Mügge, and Sarah L. de Lange (2015). ‘Gender and Populist Radical-Right Politics: An Introduction’, Patterns of Prejudice, 49:1–2, 3–15.

- Teney, Celine, Dirk Jacobs, Andrea Rea, and Pascal Delwit (2010). ‘Ethnic Voting in Brussels: Voting Patterns among Ethnic Minorities in Brussels (Belgium) during the 2006 Local Elections’, Acta Politica, 45:3, 273–97.

- Van der Brug, Wouter, and Meindert Fennema (2007). ‘Causes of Voting for the Radical Right’, International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 19:4, 474–87.

- Van der Meer, Tom., Manfred Te Grotenhuis, and Ben Pelzer (2010). ‘Influential Cases in Multilevel Modeling: A Methodological Comment’, American Sociological Review, 75:1, 173–8.

- Wängnerud, Lena (2009). ‘Women in Parliaments: Descriptive and Substantive Representation’, Annual Review of Political Science, 12:1, 51–69.