Abstract

High corruption perceptions among voters have been shown to have dire consequences for political participation, trust in institutions and ability to solve collective action problems. Research on corruption focussed on macro- and micro-level explanations to explain persistent corruption in developed countries. This article adds a new meso-level variable to the picture: party primaries. While until recently selection of candidates was the privilege of narrow party elites, many Western European parties have introduced primaries to select candidates for public offices. This study posits that this attempt at increasing intraparty democracy has negative consequences regarding corruption perceptions and suggests three mechanisms through which primaries increase corruption perceptions among supporters of parties that use them. First, primaries can be perceived as a means of ‘window-dressing’, second, primaries can suffer from vote buying, and third, candidates in primaries have incentives to campaign on anti-elitism to distinguish themselves from party elite candidates, increasing corruption salience. The theoretical argument is tested using a novel dataset on primaries in Spanish regions and corruption perceptions in a difference-in-difference design. The results support the hypothesis that primaries increase corruption perceptions among supporters of parties that use them and hint that this result is driven by the process of competitive primaries rather than a restriction of competition.

What is the role of candidate selection on voters’ assessments of political institutions? As many scholars and commentators have noted, citizen’s trust and satisfaction in political institutions have been in decline in many democracies in recent years (Dalton Citation2004; Mishler and Rose Citation2001; Torcal and Christmann Citation2021) and corruption remains prevalent even among numerous developed democracies (Transparency International Citation2022). While many studies highlight micro-level factors, such as the voters’ perception of the economy, education, partisanship or political trust (Agerberg Citation2020; Anderson and Tverdova Citation2003; Klašnja Citation2017), and macro-level factors, such as the horizontal and vertical division of power and features of the electoral system (Chang and Golden Citation2007; Gerring et al. Citation2009; Kunicova and Rose-Ackerman Citation2005; Tavits Citation2007) in explaining persistent corruption and corruption perceptions, an under-explored area is the ‘meso-level’, or the effect of political parties. Political parties are a key link between political institutions and citizens (Katz and Mair Citation1995; Klingemann et al. Citation1994). Indeed, parties frame issues and help shape public opinion regarding how citizens view their public institutions. Thus, how parties select candidates should influence voters’ overall assessment of their institutions.

While traditionally, narrow elites had the power to select candidates in Western European democracies, in the last two decades power has been increasingly transferred to party members and party supporters, in an adaptation of American primaries. The conventional wisdom suggests that candidate selection in terms of primary elections is a type of ‘democratization instrument’ (Sandri and Seddone Citation2015) that brings decision making closer to the voters and in turn should increase perceptions of fairness and legitimacy. Indeed, some studies have found positive effects of primaries on political behaviour and/or perceptions of citizens (Cross Citation1996; Lehrer Citation2012; Shomer et al. Citation2016). Conversely, Rosenbluth and Shapiro (Citation2018) argue that primaries have heightened polarisation and eroded voters’ trust in political institutions over time. Building on these insights, we anticipate that a shift in parties’ power to screen candidates will affect the way in which their candidates will behave in other political contexts, and hence will have implications for assessments of political institutions, whereby we focus on corruption perceptions. Despite the proliferation of primaries throughout the world in recent years, most of the literature outside the U.S. context focussed on the effect of primaries on parties, such as their ideological cohesion (e.g. Debus and Navarrete Citation2020), representativeness (e.g. Cordero and Coller 2018) and whether parties gain electorally from introducing primaries (e.g. Astudillo and Lago Citation2021). While there are notable exceptions to this, we still know little about the relationship between different modes of candidate selection and voters’ attitudes towards their political institutions. This study seeks to address this lacuna.

We develop a framework in which we contrast the most inclusive form of candidate selection—primaries—with other, more traditional forms of candidate selection in order to answer the question, how does inclusive candidate selection influence corruption perceptions? We argue that primaries change intraparty competition and therefore affect supporters’ perceptions of institutions. Broadly, we discuss how voters can perceive primaries as a means of window-dressing without real transfer of power and restricted competition by leaderships, as well as two mechanisms in which the competitiveness of primaries increases supporters’ perception of corruption: First, primaries can enhance clientelistic linkages and mass-registrations (Gherghina Citation2013). Second, primaries lead to an increase in outsider candidates, who in turn are more likely to campaign on anti-corruption platforms, which increases issue salience (Bågenholm and Charron Citation2014). We therefore highlight institutional assessments in the form of perceptions of corruption, which are strongly connected to institutional fairness and impartiality.

The theoretical arguments are tested in the context of Spanish regions. Not only does conducting a sub-national study come with the advantage that many other factors affecting corruption such as the electoral system, freedom of the press and level of democracy are held constant by design, but Spain also presents a unique case in variation on the dependent and the independent variables across space and time. Spanish parties have heterogeneously introduced primaries, and as such, the Spanish case offers within-party-region variation on candidate selection; in other words, candidate selection methods do not only vary by party but also for the same party across regions. Simultaneously, Spain consistently is among the countries with the most sub-national variation of corruption in Europe (Charron et al. Citation2015). Such nuanced variation in our key variables strengthens our research design and provides more reliable inferences of the relationship between primaries and corruption perceptions.

With respect to corruption, the primary empirical focus of this study is on party supporters’ perceptions of corruption in their public institutions compared with non-supporters, in that we assess the degree to which primaries affect corruption perceptions. Corruption perceptions are critically important in their own right as they are predictive of a host of salient individual level traits, such as lower life satisfaction (Helliwell and Huang Citation2006), lower trust in political institutions (Morris and Klesner Citation2010), support of anti-establishment populist parties (Agerberg Citation2020), or distrust and withdrawal of support from the system all together, causing problems of collective action (Persson et al. Citation2013; Sharafutdinova Citation2010). Corruption perceptions have also been found to correspond strongly with ‘actual’ corruption in European contexts (Charron Citation2016). Further, we argue that due to our regional level focus on political parties, our perceptions’ measures are well-suited because they specifically pertain to sub-national public services that would be affected by regional and local governments.

By using a novel dataset collected by the authors on 264 candidate selections in 48 regional elections between 2010 and 2021 combined with data from the European Quality of Government database between 2013 and 2021 (Charron et al. Citation2015), the effect of regional primaries on corruption perception is tested via several estimation approaches, including a difference-in-difference design that aids in elucidating the effects of changes in candidate selection on perceptions of corruption over time within parties and regions. Our findings show primaries increase perceptions of corruption among those partisan supporters using them as a means to select their candidates, and that the effects are strongest in the early years of adoption. Our findings further show that non-competitive primaries ('coronations’) do not negatively impact on party supporters’ attitudes, indicating that it is the competitive process of primaries rather than a restriction of competition that drives corruption perceptions. Moreover, we find no effect of primaries on other attitudes, such as economic satisfaction, or ‘trust in others’, meaning that downsides of more open candidate selection affect perceptions of regional institutions only, and not those of national ones or social trust more broadly.

Previous research on intraparty democracy

In the past decade, scholarly interest in intraparty democracy has increased. The decrease of party membership numbers inspired argumentative and normative work, assessing the functionality and legitimacy of parties as parties became less representative of the electorate and more strongly connected to the state (Mair Citation2006; Sartori Citation2005). In an attempt to counteract the loss in membership numbers and legitimacy, established parties broadened the rights given to party members and increased intraparty democracy (Faucher Citation2015; Poguntke et al. 2016; Young Citation2013), a development perpetuated by new-left and regional parties (Cordero et al. Citation2016; Debus and Navarrete Citation2020; Orriols and Cordero Citation2016).

With the widening of intraparty democracy, several parties introduced primaries, effectively giving members a say in candidate selection for representative office. Party primaries take various forms, ranging between party members being allowed to vote on lists prepared by the party committee (e.g. British UKIP) to open primaries in which every voter has the right to participate (e.g. U.S. parties in several states). Most common in Europe are closed party primaries in which only registered party members are allowed to vote on potential candidates with varying influence of the party leadership.

A key feature of intraparty democracy is candidate selection, which is ‘predominantly an extra legal process by which a political party decides which of the persons legally eligible to hold an elective public office will be designated on the ballot’ (Ranney Citation1981: 1). Candidate selection is of interest for the study of corruption more so than other features of intraparty democracy for several reasons. Candidate selection, theoretically, could have a disproportionally higher direct effect on corruption than other features of intraparty democracy. Intraparty competition and candidate selection impact the socio-demographic features of candidates, their ideological profile, responsiveness and geographical dispersion (Rehmert Citation2021), with important implications for accountability (Crutzen and Sahuguet Citation2018), and therefore, corruption.

Given the variation in candidate selection that developed in some Western European democracies such as Spain (Astudillo and Detterbeck Citation2020; Hazan and Rahaṭ Citation2010), empirical studies have highlighted several consequences of these reforms for voters and parties alike. First, in general, more open candidate selection processes tend to personalise, or ‘presidentialize’ politics at the expense of the collective regardless of the electoral system (Poguntke and Webb Citation2005). Second, scholars have investigated whether more open candidate selection affects political competition and overall representativeness of candidate lists, with mixed empirical findings (Hazan and Rahaṭ Citation2010). Third, several studies have related primaries to voter satisfaction, with some evidence that partisans of parties who elect candidates via primaries are generally more satisfied with the selection process (Bernardi et al. Citation2017), while others show increased dissatisfaction among partisans (Cross and Pruysers Citation2019). Others find that variation in candidate selection has broader implications for citizens’ perceptions and trust in institutions more broadly, with some finding that voters of parties using primaries demonstrate higher rates of democratic satisfaction (Shomer et al. Citation2016), while others claim primaries have strongly negative effects on trust in institutions (Rosenbluth and Shapiro Citation2018).

As candidates are ultimately the representatives of the electorates, candidate selection influences not only the input but also the output side of political systems. Candidates who later become Members of Parliament or part of the executive have a direct influence on policy outputs such as corruption laws as well as control over the bureaucracy. Candidates selected via primaries might choose to be more independent from the party elite and ensure anti-corruption efforts more directly (Crutzen and Sahuguet Citation2018; Fernandes et al. Citation2019; Rehmert Citation2021). Conversely, candidates selected in primaries might undermine confidence in the system among voters. In sum, while research has investigated how candidate selection affects the behaviour, responsiveness and representativeness of candidates, little attention has been paid to the effects candidate selection has on the system in which parties operate, in particular the degree to which voters perceive their political institutions to be clean from corruption. Moreover, as much empirical comparative work is cross-sectional, we have limited knowledge on how changes in candidate selection over time affect how voters assess their institutions. These lacunae motivate our theoretical contributions.

Theoretical framework

Primaries introduce an additional level of competition to the electoral system, as party supporters are given a chance to assess potential candidates for political offices. As such, primaries could increase resources for screening and serve as a means for parties to increase local-level accountability by giving party members another tool to hold the party elite responsible. Primaries, through their logic of procedural fairness in which candidates compete openly for their party’s nomination, could also result in better candidates through screening and pre-election character tests (Adams and Merrill Citation2013; Serra Citation2011). However, the increase of competition and choice for supporters can be a farce, as it is often argued that the transfer of power is only cosmetic and reinforces party leaders’ grip on the party (Hazan and Rahaṭ Citation2010; Schumacher and Giger Citation2017) or are intentionally undemocratic (Sulley Citation2022). Most parties have used primaries to signal unity and transparency to their electorate and to end intraparty conflicts (Astudillo and Detterbeck Citation2020; Chiru et al. Citation2015; Cross and Blais Citation2012). However, party leaders were also quick to establish their control over the nomination of candidates even though the process of nomination and selection had been formally widened, by increasing the hurdles to compete in primaries, effectively restricting competition (Astudillo and Detterbeck Citation2020; Hazan and Rahaṭ Citation2010). In these cases, primaries often result in so-called ‘coronations’, with a single candidate, preferred by the party elite, getting elected by the party base. In fact, insights as far back as the early progressive era in the U.S. posited that the idea of primaries ‘giving power to the people is a mockery. The reality is that it scrambles power among faction chiefs and their bands, while the people are despoiled and depressed’ (Ford Citation1909).

The Spanish Socialist Worker’s Party (PSOE) poses as a prime example of a party that formally introduced the possibility of primaries to select candidates at the regional level but often does not implement them: While primaries were formally introduced to select candidates for regional elections in 2010, out of 51 candidates nominated for regional elections between 2010 and 2020 only ten were selected via competitive primaries. This is partly due to the party’s statute, which foresees that primaries are to be suspended if the party leads the government and the incumbent decides to run again. However, even excluding these cases, in 15 out of 29 cases in which primaries should have been held according to the statute, the regional leadership selected the candidate. In cases as described here, the prospect of primaries only serves to produce a more ‘transparent’ image of a party while the party elite still puts forward their candidates by effectively restricting the competition. If such ‘window-dressing’ methods fail, voters could perceive the system as fraudulent and corrupt, being discouraged by a party leadership that ensures that primary voters do not gain too much independence and no real competition takes place.

A second way through which the competition that is introduced through primaries could affect voters’ perceptions of corruption negatively is through a competitive primary process itself, either based on candidates’ campaigning or by candidates engaging in illicit means of winning votes.

First, primaries are more likely to attract a candidate that is not part of the traditional party elite (Serra Citation2011) and such an outsider might choose to campaign on anti-elitism and anti-corruption in the primary, effectively increasing the salience of corruption among party supporters. As intraparty competition implies less ideological difference between candidates, individuals seeking office are incentivized to stand out via positions which highlight extremism, outrage and conflict, which are in turn ‘catnip for journalists’ (La Raja and Rauch Citation2020), affecting the minds of voters. This mechanism is similar to a trend found among new parties in European democracies, which are likely to adapt anti-corruption and anti-elitism rhetoric to separate themselves from the mainstream parties and to appeal to voters dissatisfied with the current establishment (Bågenholm and Charron Citation2014; Engler Citation2020). Similarly, primaries produce elections that are more likely to incentivize candidates to stress valence issues and adopt anti-corruption and anti-elitism rhetoric to separate themselves from the established candidates and to profit from the fact that they are an outsider within the party (Serra Citation2011). However, while the individual candidate might benefit from campaigning on anti-corruption and anti-elitism, it is likely to have negative spill-over effects by enhancing salience of corruption for party supporters and increasing corruption perceptions. In particular, we would expect this to be strongest among party supporters who have most recently experienced a change in candidate selection from a party-driven selection to a primary. In such a case, the competitiveness of the primaries has a negative effect in itself through the campaigning of candidates.

Second, literature on candidate selection has argued that primaries can be subject to vote-buying efforts and mass-registrations. Several authors identified mass-registrations of members before primary elections while membership numbers drop again after the primary was held (Carty and Cross Citation2006; Malloy Citation2003). This suggests that membership was not based on the intention of forming a connection with the party but merely to influence candidate selection, a process argued to be actively driven by candidates (Hazan and Rahaṭ Citation2010). Especially in the context of ethnic registrations of marginal groups, concerns were raised that mobilisation was not aimed at increasing their representation in party politics but rather provided a good base for clientelistic connections (Carty and Cross Citation2006). Not only were cases of inflation of membership numbers reported, also cases of vote buying and bribery have been found in the context of primaries (Ascencio Citation2021; Baum and Robinson Citation1995; Scherlis Citation2008). The chance of such tactics taking place is more likely to occur in competitive primaries than in the above-described coronations, as candidates in primaries for regional office have high incentives to engage in such methods to win a candidate nomination. The benefits of public office are high and in high corruption and clientelistic political contexts the repercussions of engaging in vote buying and mobilisation with the aim of forming a patron-client relationship are low, as they are ‘accepted’ forms of winning competitions and parties lack the will and means to prevent them (Kenig and Pruysers Citation2018). However, it is quite likely that even if engaging in these tactics does not have a direct negative impact for the candidate, the effect on the party supporters that personally experience these illicit means are more dire: As party leaders change and adapt selection rules to ensure that their preferred candidate wins and candidates engage in vote buying and clientelism, it is likely that party supporters lose faith in the political system and perceive higher corruption levels (Bacchus and Boulding Citation2022; Singer Citation2009).

Overall, the arguments of this section point towards primaries having a negative effect on corruption perceptions among the supporters of parties that use them, due to party leaders using primaries to reinforce their influence, candidates engaging in clientelistic practices to ensure being elected and campaigning on anti-elitism and anti-corruption platforms that raise salience of corruption, resulting in the following hypothesis:

H1: Respondents who support parties that select candidates via primaries will have higher levels of corruption perceptions, all else being equal.

The case of Spain

The above developed theoretical argument is tested in the context of Spanish regions. Spain provides a good case for our analysis since it presents considerable variation in both the independent and the dependent variable.

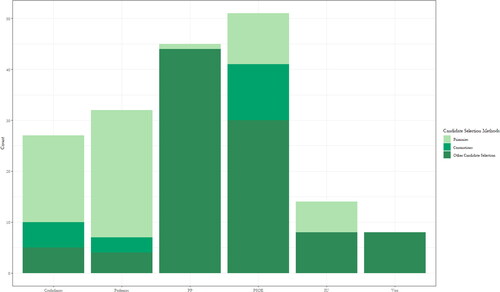

There is considerable variation of candidate selection methods across the regions of Spain ().Footnote1 While candidate selection regimes in Spain were for a long time defined by low inclusiveness, in recent years an increasing number of parties adopted regional primaries to select candidates. Given the formal possibility of regional primaries, intraparty democracy was unevenly introduced in regions even within the same party (; Debus and Navarrete Citation2020).

Figure 1. Distribution of candidate selection methods across parties. Notes: Includes all regional candidate selections between 2010 and 2020. As not every party runs in each region, and several of the parties were founded in the period under investigation, the number of candidate selections per party varies. For an overview of how candidate selection varies across parties by region please refer to in the online appendix.

The reason for the uneven introduction of primaries remains rather uncertain and could raise concerns about reverse causality if the reason for implementing primaries is a high corruption context. While we tackle potential endogeneity issues with our estimation strategy, a short review of academic arguments for the introduction of primaries in Spain is in order. First, research has argued that primaries are attractive to parties with declining membership numbers to help them appear more internally democratic and attract new members (Poguntke et al. 2016), an argument also cited in the context of Spanish regional parties (Debus and Navarrete Citation2020). Second, the emergence of Podemos (2014) and Ciudadanos (2006, Catalonia), parties defining intraparty democracy as a key feature of their ideology, changed the perception of primaries towards a tool of responsiveness and representation (Cordero et al. Citation2016; Debus and Navarrete Citation2020; Orriols and Cordero Citation2016), increasing pressure on more traditional parties. Third, Astudillo and Detterbeck (Citation2020) argue that the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE) introduced primaries first as a response to electoral setbacks and a decrease in vote shares in several Spanish regions in 2010, also including several caveats for the party not to use primaries as a candidate selection mechanism, if, for instance, only a single candidate runs for candidacy or the national leadership sees reason to suspend potential candidates. While this does explain the increasingly widespread use of primaries in Spanish regions in general, it does not explain where regional variation within the same party stems from. Astudillo and Detterbeck (Citation2020) argue to this point, that the variation in the implementation of primaries after their initial introduction in the PSOE and PP is mainly elite driven, and often used to resolve intraparty conflicts.

The high level of autonomy of Spanish regions makes Spain an interesting case besides its strong variation in the explanatory variable. While Spain’s constitution establishes a unitary structure, the Spanish system is characterised by a strong decentralisation in both the political and administrative sense and is often referred to as a quasi-federal state (Colomer Citation1998). Therefore, being the leading candidate for a regional party promises access to political office and the spoils associated with it, therefore making it attractive for politicians to compete as candidates (Franceschet and Piscopo Citation2014).

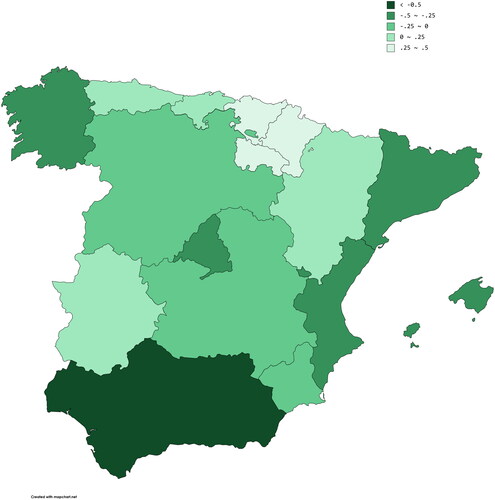

Finally, Spain has consistently been ranked among the highest in the whole of Europe with respect to regional variation of corruption, as some of its regions rank among the best performers (e.g. Pais Vasco), while others rank considerably lower (e.g. Andalusia) (Charron et al. Citation2019). shows a map of the corruption perception index averaged for the past three rounds of the data across all regions, whereby lighter (darker) shaded regions imply lower (higher) average corruption perceptions.Footnote2

Figure 2. Corruption perceptions index by region: 2013–2021. Notes: Figure shows average corruption perceptions from EQI 2013, 2017 and 2021 data. Data is standardised with an EU mean of ‘0’ and standard deviation of ‘1'. Minimum: −0.60 (Andalusia); Maximum: 0.48 (Pais Vasco). Canary Islands (−0.47) excluded from the graphic.

Data, design and estimation

Our sample relies on three waves of the European Quality of Government Index (EQI) survey (Charron et al. Citation2019), which looks into citizens’ perception and experiences of corruption with their local and regional public services. The emphasis of the survey is to gauge the extent to which respondents believe their sub-national authorities administer services impartially and with a low degree of corruption. The survey has undertaken four rounds since 2010, with the latest round in 2021 (Charron et al. Citation2022). The advantage with this survey is the sub-national focus of the questions, the sample size per region, along with several corruption-oriented questions being asked with the same formulation over four waves, ensuring comparability over time. As the question regarding partisan affiliation was not included in 2010, we rely on the 2013, 2017 and 2021 EQI data for Spain.

In total there are 21,859 respondents across the three waves.Footnote3 However, in some cases, we limit our comparisons to respondents from regions only where at least one party adopted primaries as their method of candidate selection to isolate the within-regional variation among parties ('effective sample’).

We proxy our dependent variable via an index of corruption perceptions from the EQI survey. Certainly, one can argue that ‘perceptions of corruption are not corruption’. However, based on our research question, we argue that our measure is a suitable alternative for several reasons. As previously noted, public perceptions of corruption are important in and of themselves, as they are an indication of system legitimacy, along with being strongly predictive of other important attitudes and behaviours, such as trust in government, participation in politics, voting-behaviour and life satisfaction, inter alia (see for example Agerberg Citation2017; Helliwell and Huang Citation2006; Sharafutdinova Citation2010). Moreover, perceptions tend to correspond strongly with the corruption experiences of citizens (Charron Citation2016), and scholars have found that objective measures of political corruption scandals in countries such as Spain tend to lead to higher perceptions of corruption and lower trust (Solé-Ollé and Sorribas-Navarro Citation2018). As our measure, we aggregate questions on perceptions of corruption from three sub-national services—education, health care and law enforcement, which together serve as a proxy for citizens’ assessment of institutions in their area.Footnote4 The variable ranges from 0 to 10 whereby higher values equal higher perceived corruption, with a mean of 4.2 and standard deviation of 2.6.

The main independent variables are the partisanship of the respondent (or lack thereof), along with whether or not their preferred party carried out a primary in the most recent regional election prior to the survey wave. The data from the survey waves were collected in three waves, in 2013, 2017 and in 2021. As regards partisanship, the survey uses a standard formulation about which party one would support if the election was held tomorrow, and respondents are given a list of parties, along with the choice of ‘regional party’, ‘other’ or ‘none’ (in the online appendix, see Table A1 for distribution by region and Spanish average).Footnote5 We then collected data on regional primaries for leading candidates in regional elections across the period and coded each party that competed within each region as having a primary ‘1′, or not ‘0′.

Table 1. Predictors of corruption perceptions in Spain.

In order to approximate a test of the proposed mechanisms, we rely on two different measures for primaries. First, we coded whether a primary selection of a leading candidate for the regional election took place in which only a single candidate competed ('coronation’). If our results show that coronations drive the effect of primaries on corruption perception, this would speak in favour of the mechanism that party leaders restrict competition and voters perceive primaries as a mere action of window-dressing. Second, we coded competitive primaries, such as a candidate selection for a leading regional candidate is coded as a competitive primary if the competition included at least two competitors and either party members or registered party supporters were allowed to vote. This ensures that primary voters had a real choice and ‘coronations’ of single candidates were excluded. If we find that competitive primaries affect corruption perceptions rather than coronations this would hint that it is the competitive process of primaries that is problematic. This would be early evidence for either campaigning or clientelism to be the cause of higher corruption perceptions. We refrain from making any bolder claims about the driving mechanisms because of lack of data on the campaigning platforms as well as systematic tracing of vote buying and clientelism in primaries. While we are aware that these are not perfect tests for our theoretical arguments, they provide valid empirical implications at this stage of data availability. Data on competitive primaries was taken from a dataset shared by Debus and Navarrete (Citation2020) on primaries between 2003 and 2015 and extended by the authors to cover the time span until 2021 and to include non-competitive primaries. Respondents were then matched with these party-regional level variables and coded ‘1′ if they support a party that used a primary or coronation in the latest regional election before the survey wave, and ‘0′ otherwise. The main other mode of candidate selection is selection by a leadership, either selection by regional leadership or national leadership (53% of all candidate selections are selection by leadership, 5.7% of selections are based on assemblies), thus, our model mainly compares the effect of primary selection to selection by leaderships.Footnote6

As our design is observational, we account for several possible confounders. First, whether or not one’s preferred party is in power, in particular at the national level is related to corruption perceptions question, with government supporters showing systematically lower perceptions on average (Agerberg Citation2019). We thus include a dummy variable whether one’s party is in power at the national level. Second, education levels are both a predictor of one’s political party (or lack thereof) as well as perceptions of corruption (Charron and Annoni Citation2021; Gallego Citation2010). We therefore control for one’s education level with a five-level ordered variable. As age, gender and population of residence could be confounding factors, we also include these in the model. In addition, the EQI employed a mixed administration approach in 2021 and we control for the survey administration for all models when the 2021 data is used.Footnote7 Finally, as the observations in the data are cross-nested, we include fixed years and regions to account for unexplained time and spatial-effects. Summary statistics are found in the online appendix (Table A2).

Table 2. The effect of a change in candidate selection on corruption perceptions for competitive primaries: DiD estimates.

The samples are independent across waves; thus, we do not have panel data that allow for within-unit variation. We rely on two sources of variation in our estimations to identify the effect of primaries on party supporters’ corruption perceptions. Firstly, we test whether the perceptions of corruption are systematically different between citizens who support parties with primaries in their region versus other voters. With two-way, fixed-effects models, our estimate therefore tells us the static effect of the average difference by means of the dependent variable for partisans with primaries versus all other respondents, averaged over all time periods and regions. Our hypothesis anticipates a positive and significant coefficient.

Secondly, we exploit the time variation in the data and estimate the dynamic effect of a change in candidate selection from one wave to the next via a quasi-experimental difference-in-difference (DiD) design (see online appendix for more details). Using this strategy, we distinguish between parties within regions that experienced a change in candidate selection from survey wave ‘t − 1′ to survey wave ‘t’ ('treatment’) with those that did not ('control’), and with a binary time count, we create an interaction which serves as a difference-in-difference (DiD) estimator. Any significant interaction effect implies that trends in corruption perceptions have changed systematically within groups of respondents whose party did not change candidate selection but reside in the same region. If our main theoretical hypothesis is correct, the interaction term should be positive and significantFootnote8 (see online appendix for more specification details).

While the EQI samples are intended to be representative at the regional level, we use post-stratification weights on gender, age and education levels to ensure better representativeness. Finally, as our predictions imply clustering of assessments of institutional corruption by party, we cluster standard errors by partisanship.

Empirical results

In a first step, we investigate the effect of competitive primaries on corruption perceptions. shows the results for the two-way fixed effects models. The first two models pool all three waves and show the baseline results and those with the control variables. The third and fourth models remove 2021 and 2013 respectively, testing whether our results are sensitive to the exclusion of certain years.

Overall, the effect of our main variable is clear across all four models—respondents who support parties which select candidates via competitive primaries demonstrate significantly higher levels of corruption perceptions compared with party supporters using other methods of candidate selection. The models show that the difference in corruption perceptions ranges from 0.25 to 0.38, depending on the specification. The magnitude of the effect is modest, but significant, ranging from 10% to 15% of a standard deviation change in the dependent variable.

The control variables are mainly in line with previous expectations. Education is a highly relevant factor, with more highly educated respondents reporting lower levels of corruption perceptions on average. Age is also highly predictive, with younger respondents reporting the highest level of corruption perceptions, followed by each consecutive age group. We also observe year and administration effects, with 2017 and online showing the highest perceptions respectively. Gender plays a role in models 3 and 4, with females showing higher perceptions of corruption, yet the effect is not robust across the full sample. Finally, we observe that neither support for the governing party nor population is significant predictors of corruption perceptions across these three waves of the EQI.

While we observe that on average, supporters of parties with competitive primaries assess their institutions as more corrupt, we cannot rule out that primaries might be adopted as a remedy to help mitigate corruption, thus the relationship may be endogenous. In an attempt to address this concern, we now move to , which reports the results for the difference-in-difference (DiD) estimation. For transparency purposes, and to highlight any differences in the effects over the time periods, we separate the models into two groups—the first set of results compares the 2017 round with the 2013 round (models 1–3), and the second set of results (models 4–6) compares the 2021 and 2017 waves. In these models, all control variables from are included (not shown for sake of space).

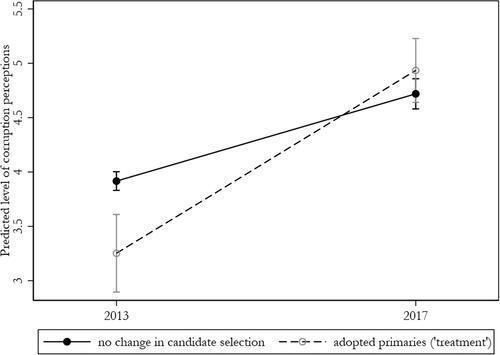

suggests stronger evidence that the effects found in may be causal, as the DiD estimator is significant and positive in all models (except for model 6). The effects are strongest in models 1–3, which estimate the effects of the change in candidate selection between 2013 and 2017, with the difference-in-difference ranging between 0.76 and 0.88, depending on the specification. Model 1 includes only individual level covariates, and no regional dummies, while model 2 includes them. Model 3, which we label ‘effective sample’, includes only regions where at least one party made a candidate selection change between 2013 and 2017, thus we compare only regions that include a ‘treatment’ case, and omit the regions that only contain ‘control’ cases. In the latter case, the magnitude of the effect is strongest. Interestingly, we observe that the baseline corruption perceptions of supporters of parties that would adopt primaries to select candidates between 2013 and 2017 was in fact lower, and then exceeded all other voters by 2017. provides a visual of the difference-in-difference effect.

Figure 3. Effect of adopting primaries on corruption perceptions: 2013–2017. Notes: Results from model 3 in , 95% confidence intervals reported from clustered standard errors by party.

The results in support the initial finding of , that primaries increase corruption perception among party supporters whose parties use competitive primaries with causal evidence. This is in line with the expectations formulated in the theory section. Whether the effect is a result of candidates engaging in clientelistic or vote-buying activities or candidates campaigning on anti-corruption and anti-elitism platforms resulting in higher corruption salience or a result of both factors is not possible to determine from our analysis, but it is clear, that candidate selection via competitive primaries does not lead to supporters assessing their institutions as less corrupt.

Models 4 to 6 test the effects with the 2017–2021 waves. In general, we find similar patterns although weaker both in magnitude and significance, supporting again our hypothesis. Model 4 shows that again: the perceptions of respondents whose party changes to a competitive primary selection system between 2017 and 2021 had lower perceptions by −0.17 in 2017. While the collective corruption perceptions went down between these two waves, the positive and significant DiD estimate demonstrates that the perceptions among those ‘treated’ went down significantly less compared with the control cases—by 0.21 and 0.18 in models 4 and 5, respectively. This implies that the results in model 4 are mainly robust to the inclusion of regional fixed effects in model 5. However, in model 6, we observe that the interaction term falls from statistical significance when employing the more conservative test using only respondents in the ‘effective’ sample between 2017–2021.

Thus, according to , we find strong evidence that a change in candidate selection had an effect on partisans’ corruption perceptions between 2013–2017 (when the greatest number of changes actually occurred), and some evidence that the effect also occurred from 2017–2021, yet the findings are less robust in some model specifications.

The finding, that the effect strength differs between years is interesting and could be due to a weakening of the mechanisms proposed in the theory section over time. First, it is possible that the institutionalisation of primaries and the potential of repeated interaction incentivizes candidates to invest in programmatic rather than clientelistic linkages, reducing vote buying over time and increasing trust of voters in competitive primaries. Second, the appeal of running on anti-corruption platforms might diminish over time as primaries become more institutionalised and media coverage diminishes as primaries lose their ‘newness’. Indeed, as in the online appendix shows, primaries became more widely used after the first period under investigation here, 2013–2017, providing some anecdotal evidence for this reasoning. However, for now we can only speculate on the reasons and leave more systematic investigation to future research.

In a next step, we estimate the effect of coronations, i.e. primaries in which a single candidate ran. This allows us to approximate a test of the first mechanism proposed, that voters disappointed with a leadership that restricts competition perceive primaries as a means of window-dressing and express subsequently higher corruption perceptions. shows the results of a difference-in-difference estimation of the effect of coronations on corruption perceptions, model 1 shows the estimates of a change from no primaries to coronations between 2013 and 2017, while model 2 shows the results of the analysis for a change from 2017 to 2021. Both models include the full set of controls specified in .

Table 3. The effect of a change in candidate selection on corruption perceptions for coronations: DiD estimates.

The DiD estimator only reaches statistical significance in Model 1, estimating the effect of a change to coronations between 2013 and 2017. However, the effect goes in the opposite direction than the previously estimated effect in . While in the former, competitive primaries increase corruption perceptions, coronations seem to decrease corruption perceptions for supporters of parties that use them. The effect is about half the size of the effect estimated for competitive primaries in . The effect of a change to coronations has no statistically significant effect in the second period under investigation, 2017–2021. The finding that coronations has a decreasing or no effect on corruption perceptions provides preliminary evidence that the process of competitive primaries rather than the restriction of competition drives the effect of primaries on corruption perceptions. However, we are still unable to detect whether the effect of competitive primaries is driven by candidates campaigning on anti-corruption platforms and thereby increasing salience of corruption or vote buying and clientelistic linkages dominating the competition and leave it to future research to determine this.

Exploring effects with alternative measures

Our theory suggests that primaries will lead to more negative assessments of regional institutions overall. In lieu of corruption perceptions, we first test whether coronations and competitive primaries have a similar impact on perceptions of fairness and impartiality or regional institutions in Tables A3 and A4 in the online appendix. We find strikingly similar patterns for perceptions of impartiality as those presented in the main analyses regarding corruption for competitive primaries while we find no effect of coronations on impartiality perceptions. As the effect of coronations is largely a null-finding, we continue to test our findings of competitive primaries having an effect on other outcomes. We should not expect that primaries affect assessments of other institutions (national) or other forms of trust for example. To test this expectation, we test whether competitive primaries affect overall, country-level economic satisfaction (Table A5 in the online appendix), trust in national parliament as well as social trust in others (Table A6 in the online appendix). We find, as expected, that competitive primaries have no effect on any of these outcomes. Finally, we explore whether competitive primaries lead to an increase in corruption experiences in the form of petty corruption in public services (Table A7). Likewise, we find that primaries do not drive trends in experiences with corruption, which shows that the effect of competitive primaries on perceptions of corruption does not work via direct experience with corruption in public services, but via other channels, such as heightened primary campaigns on anti-elitism and anti-corruption.

Next, we check whether the results are consistent when separating perception of corruption for education and health services (mainly controlled by regions) and law enforcement (mainly controlled at national level, with some exceptions).Footnote9 In splitting the measures of education and health care from law enforcement, we test whether the perceptions of mainly sub-nationally administered services are different from those with national level administration (e.g. Policia National), or are exclusively local. We find no notable distinction in our 2013–2017 sample, while we find that the 2017–2021 DiD effects are in the expected direction, they are only statistically significant for the indicator of law enforcement, which we speculate has to do with the timing of the 2021 survey corresponding with strict lock-downs and an increased presence of the police as symbolising public institutions (online appendix, Table A8).

In sum, these findings, along with those in the main results, suggest that there is a coercive effect of competitive primaries on the perception of regional institutions in terms of higher perceptions of corruption and lower perceptions of fairness, in particular in the earlier rounds of primary adoption (2013–2017). Further, that other, less related outcomes, such as perceptions of the economy or national institutions, are unrelated to competitive primaries, which provides indirect evidence for our proposed mechanisms.

Additional robustness and design checks

To the extent that we can, we check the assumptions of the difference-in-difference design with two additional tests. First, we run placebo tests with the ‘treated’ partisan groups for 2017–2021 and test the effect on the similar partisan groups for the prior period (2013–2017). Given these partisans had yet to observe a change in their party’s candidate selection prior to 2017, we should not observe difference-in-difference effects. The test shows null results, as anticipated (see online appendix, Table A9). Additionally, we can assess the parallel trends assumption for the period prior to the 2017–2021 waves (e.g. how treatment/control partisan for the 2017–2021 period trended in 2013–2017 for corruption perceptions). We do not see any reason to reject the parallel trend assumption in this case, as the mean level of perception among control and treatment cases for the 2017–21 period follows parallel trends in the previous period, although the control cases show higher perceptions (see in the online appendix). Unfortunately, due to the partisanship question not being included in the 2010 wave, we cannot do this for the 2013–2017 findings in models 1–3 in Table A9.

Next, we check the robustness of the results by excluding respondents from certain regions for two reasons. First, while most regional elections were held within two years of the subsequent round of the survey data collation, the regional elections in Catalonia were held just after the data collection in 2017. Thus, their ‘treatment’ effects for the 2017–2021 samples are over 3.5 years prior to the 2021 EQI round. Catalonia also held a snap election in 2015, which makes this event unique for the 2013–2017 comparison, and most likely affected parties internal planning and candidate selection strategies. Second, we also consider the Basque Country, which (along with Catalonia) has a comparatively unique party system—many of the parties are not included in our data—which could render this case an outlier. In online appendix Table A10, we find that our results hold when excluding respondents from these two regions. Finally, we check whether the findings are spurious to the concurrent electoral set-backs of parties at the regional level, which could be correlated with both our main independent variable and motivation to adopt new candidate selection methods, as parties may perceive an electoral advantage in doing so (Carey and Polga-Hecimovich Citation2006). Specifically, we code respondents living in regions who support a party that previously controlled the regional government but was voted out of power in the current regional government, as ‘treatment’ cases, and test whether this additional treatment confounds our focal relationship. We find our main effects robust, shown in online appendix Table A11.

Conclusion

Does the candidate selection method of a party affect how its supporters assess their institutions? While the literature is mixed on how primaries in particular affect voter behaviour, broadly speaking, our findings suggest that when party nominations are more open to the voters, partisans in turn perceive higher levels of corruption in their institutions on average. Using survey data from the last three rounds of the EQI for Spanish respondents and a unique dataset on Spanish party candidate selection, our analysis exploits rich sub-national variation across Spanish regions and political parties over three rounds of the survey data (2013, 2017 and 2021). We find that that competitive primaries are associated with higher perceptions of corruption on average, and in addition, using a difference-in-difference design, our results show that changes in candidates selection from no primary to competitive primary lead to greater changes in (higher) perceptions of corruption among such partisan supporters, compared with other voters whose party did not change their candidate selection, although the effect is strongest in the earlier period of primary adoption (2013–2017). No such effect is found for ‘coronations’ of single candidates. The essence of our findings corroborates some recent work in the U.S., where scholars identify primaries as contributing to a decline in institutional trust and political polarisation (La Raja and Rauch Citation2020; Rosenbluth and Shapiro Citation2018).

Our study makes several contributions across multiple research sub-fields. First, in general, research on corruption has largely focussed on macro-level factors such as the institutional setup and aspects of democracy, as well as micro-level determinants that keep voters from ‘throwing the rascals out’. Our study added the role of parties to this literature, by investigating how the selection of candidates affects individuals’ perception of corruption. Second, understanding how candidate selection influences corruption perceptions is crucial in the light of increasing intraparty democracy and use of primaries as a selection tool in Western European democracies. As the trend among many parties is to open their candidate selection process to increase transparency, attract more voters and to even improve governance, our study presents a clear negative consequence to such reforms. Third, with newly collected data, we take advantage of the rich variation for our main variables of interest in the Spanish case and provide temporal evidence using a quasi-experimental design.

While the empirical evidence corroborated our theoretical expectations, several of our proposed mechanisms remain untested. For example, our theoretical argument that primaries lead to higher corruption perceptions is based on three potential mechanisms. One, research on primaries that has argued that primaries are often merely a tool of party leaders to reinforce their power over the party while signalling transparency (Astudillo and Detterbeck Citation2020; Hazan and Rahaṭ Citation2010; Schumacher and Giger Citation2017), which could lead to backlash. Two, we argue that the competitiveness in primaries incentivizes candidates to adopt an anti-elitism and anti-corruption rhetoric, similar to new parties in order to draw attention to themselves (Bågenholm and Charron Citation2014) and to engage in mass-registration and vote buying (Carty and Cross Citation2006; Malloy Citation2003). While our theoretical argument outlines several theoretical mechanisms through which primaries could increase corruption perception, we are unable to determine the exact causal mechanism at play. We approximate testing the effect of restricted competition in primaries by comparing non-competitive to competitive primaries and find that coronations are insignificant, yet we cannot make any conclusive statement about what aspect of the process of primaries affects corruption perceptions. We largely agree with the assessment by Astudillo and Lago (Citation2021) that future research needs to focus on collecting systematic evidence on the process of primaries themselves, the platforms that candidates campaign on, and how prevalent vote-buying and clientelistic linkages in primaries are.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1 MB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Georgios Xezonakis and Gefjon Off for their helpful comments on drafts of this manuscript. We would further like to extend our gratitude to Professor Marc Debus and Dr Rosa Navarrete for sharing their data on primaries in Spain. The authors are grateful for the constructive comments of the anonymous reviewers of this paper, which helped greatly to strengthen the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nicholas Charron

Nicholas Charron is a Professor in the Department of Political Science and a Research Fellow at the Quality of Government Institute, University of Gothenburg. He is also a visiting scholar at the Minda de Gunzburg Centre for European Studies at Harvard University. Charron’s research is concerned with political behaviour, links between gender and politics and corruption, electoral behaviour, comparative politics on political institutions, studies of corruption and quality of government and how these factors impact economic development with a focus on Europe and the US. [[email protected]]

Jana Schwenk

Jana Schwenk is a PhD candidate at the Department of Political Science at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden. She received a MA degree from the University of Gothenburg in Comparative Politics and an MA degree from the University of Konstanz in Political Science and Research Design. Her research interests are in intraparty democracy, candidate selection, corruption and female representation. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 We acknowledge that there is also temporal and party-level variation within our highlighted categories of candidate selection in terms of the selectorate, eligibility for candidacy, inter alia (Barberà et al. Citation2016). For reasons of parsimony and to maintain a proper sample size, we elect to collapse these differences into a single category for this analysis. For an overview of variation of candidate selection across regions and party please refer to Figure A2 in the online appendix.

2 Spanish regions show widening regional variation over time, and now the second highest within-country variation in the 2021 data after Italy among all EU27 countries.

3 In total, the survey samples 17 Spanish regions. The 2013 and 2017 data includes 400 respondents per region, while the 2021 data includes 500 per region.

4 The Cronbach's alpha for the three item-index over the three waves is 0.85, showing high internal consistency.

5 While this question refers to the national level, we assume it to be an appropriate proxy, as regional elections are heavily dominated by national parties (Ortega et al. Citation2021) and split-ticket voting is rare (Sanz Citation2008).

6 The average lag between a primary competition and the collection of the survey data is 22 months (c.f. also Figure A4 in the online appendix for a distribution of the time lag between primary competitions and survey wave). While we acknowledge that such a time difference might make it questionable whether our results are based on the effect of primaries rather than some other factors, we also believe that finding any evidence of an effect of primaries after such a time span indicates that primaries could have a long-lasting effect on partisans’ attitudes.

7 Computer assisted telephone interviews, ‘CATI', and online show systematic differences in perceptions.

8 As some of the ‘control’ cases in the DiD analyses for time ‘t’ to ‘t + 1’ could contain both ‘control’ cases as well as those ‘treated’ in time ‘t − 1', we control for ‘past treatment status’ (0/1) in these models. We have no cases of parties adopting primaries that then reverted back to none.

9 Only Navarre, Canary Islands, Basque country and Catalonia have fully autonomous, regional police forces, while all others have purely national or local.

References

- Adams, James, and Samuel Merrill (2013). ‘Policy-Seeking Candidates Who Value the Valence Attributes of the Winner’, Public Choice, 155:1–2, 139–61.

- Agerberg, Mattias. (2017). ‘Failed Expectations: Quality of Government and Support for Populist Parties in Europe’, European Journal of Political Research, 56:3, 578–600.

- Agerberg, Mattias. (2019). ‘The Curse of Knowledge? Education, Corruption, and Politics’, Political Behavior, 41:2, 369–99.

- Agerberg, Mattias. (2020). ‘The Lesser Evil? Corruption Voting and the Importance of Clean Alternatives’, Comparative Political Studies, 53:2, 253–87.

- Anderson, Christopher J., and Yuliya V. Tverdova (2003). ‘Corruption, Political Allegiances, and Attitudes Toward Government in Contemporary Democracies’, American Journal of Political Science, 47:1, 91–109.

- Ascencio, Sergio J. (2021). ‘Party Influence in Presidential Primaries: Evidence from Mexico’, Party Politics, 27:6, 1229–42.

- Astudillo, Javier, and Klaus Detterbeck (2020). ‘Why, Sometimes, Primaries? Intraparty Democratization as a Default Selection Mechanism in German and Spanish Mainstream Parties’, Party Politics, 26:5, 594–604.

- Astudillo, Javier, and Ignacio Lago (2021). ‘Primaries Through the Looking Glass: The Electoral Effects of Opening the Selection of Top Candidates’, British Journal of Political Science, 51:4, 1550–64.

- Bacchus, Emily Beaulieu, and Carew Boulding (2022). ‘Corruption Perceptions: Confidence in Elections and Evaluations of Clientelism’, Governance, 35:3:2, 609–32.

- Bågenholm, Andreas, and Nicholas Charron (2014). ‘Do Politics in Europe Benefit from Politicising Corruption?’, West European Politics, 37:5, 903–31.

- Barberà, Oskar, Marco Lisi, and Juan Rodríguez Teruel (2016). ‘Democratising Party Leadership Selection in Spain and Portugal’, in Giulia Sandri and Antonella Seddone (eds.), Party Primaries in Comparative Perspective. New York: Routledge, 77–102.

- Baum, Julian, and James A. Robinson (1995). ‘Party Primaries in Taiwan: Reappraisal’, Asian Affairs: An American Review, 22:2, 91–6.

- Bernardi, Luca, Giulia Sandri, and Antonella Seddone (2017). ‘Challenges of Political Participation and Intra-Party Democracy: Bittersweet Symphony from Party Membership and Primary Elections in Italy’, Acta Politica, 52:2, 218–40.

- Carey, John M, and John Polga-Hecimovich (2006). ‘Primary Elections and Candidate Strength in Latin America’, The Journal of Politics, 68:3, 530–43.

- Carty, R. Kenneth, and William Cross (2006). ‘Can Stratarchically Organized Parties Be Democratic? The Canadian Case’, Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 16:2, 93–114.

- Chang, Eric C. C., and Miriam A. Golden (2007). ‘Electoral Systems, District Magnitude and Corruption’, British Journal of Political Science, 37:1, 115–37.

- Charron, Nicholas. (2016). ‘Do Corruption Measures Have a Perception Problem? Assessing the Relationship Between Experiences and Perceptions of Corruption among Citizens and Experts’, European Political Science Review, 8:1, 147–71.

- Charron, Nicholas, and Paola Annoni (2021). ‘What Is the Influence of News Media on People’s Perception of Corruption? Parametric and Non-Parametric Approaches’, Social Indicators Research, 153:3, 1139–65.

- Charron, Nicholas, Lewis Dijkstra, and Victor Lapuente (2015). ‘Mapping the Regional Divide in Europe: A Measure for Assessing Quality of Government in 206 European Regions’, Social Indicators Research, 124:3, 1059.

- Charron, Nicholas, Victor Lapuente, and Paola Annoni (2019). ‘Measuring Quality of Government in EU Regions Across Space and Time’, Papers in Regional Science, 98:5, 1925–53.

- Charron, Nicholas, Victor Lapuente, Monika Bauhr, and Paola Annoni (2022). ‘Change and Continuity in Quality of Government: Trends in Subnational Quality of Government in EU Member States’, Investigaciones Regionales - Journal of Regional Research, 53:2, 5–23.

- Chiru, Mihail, Anika Gauja, Sergiu Gherghina, and Juan Rodríguez-Teruel (2015). ‘Explaining Change in Party Leadership Selection Rules’, in William Cross and Jean-Benoit Pilet (eds.), The Politics of Party Leadership. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 31–49.

- Colomer, Josep M. (1998). ‘The Spanish "State of Autonomies": Non‐Institutional Federalism’, West European Politics, 21:4, 40–52.

- Cordero, Guillermo, and Xavier Coller, eds. (2018). Democratizing Candidate Selection. New York: Springer International Publishing.

- Cordero, Guillermo, Antonio M. Jaime-Castillo, and Xavier Coller (2016). ‘Candidate Selection in a Multilevel State: The Case of Spain’, American Behavioral Scientist, 60:7, 853–68.

- Cross, William. (1996). ‘Direct Election of Provincial Party Leaders in Canada, 1985–1995: The End of the Leadership Convention?’, Canadian Journal of Political Science, 29:2, 295–315.

- Cross, William, and André Blais (2012). ‘Who Selects the Party Leader?’, Party Politics, 18:2, 127–50.

- Cross, William, and Scott Pruysers (2019). ‘Sore Losers? The Costs of Intra-Party Democracy’, Party Politics, 25:4, 483–94.

- Crutzen, Benoit S. Y., and Nicolas Sahuguet (2018). Electoral Incentives: The Interaction Between Candidate Selection and Electoral Rules. Rotterdam: Erasmus School of Economics, Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam.

- Dalton, Russell J. (2004). Democratic Challenges, Democratic Choices. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Debus, Marc, and Rosa M. Navarrete (2020). ‘Do Regional Party Primaries Affect the Ideological Cohesion of Political Parties in Multilevel Systems? Evidence from Spain’, Party Politics, 26:6, 770–82.

- Engler, Sarah. (2020). ‘“Fighting Corruption” or “Fighting the Corrupt Elite”? Politicizing Corruption Beyond the Populist Divide’, Democratization, 27:4, 643–61.

- Faucher, Florence. (2015). ‘New Forms of Political Participation. Changing Demands or Changing Opportunities to Participate in Political Parties?’, Comparative European Politics, 13:4, 405–29.

- Fernandes, Jorge M., Lucas Geese, and Carsten Schwemmer (2019). ‘The Impact of Candidate Selection Rules and Electoral Vulnerability on Legislative Behaviour in Comparative Perspective’, European Journal of Political Research, 58:1, 270–91.

- Ford, Henry Jones. (1909). ‘The Direct Primary’, North American Review, 190:644, 1–14.

- Franceschet, Susan, and Jennifer M. Piscopo (2014). ‘Sustaining Gendered Practices? Power, Parties, and Elite Political Networks in Argentina’, Comparative Political Studies, 47:1, 85–110.

- Gallego, Aina. (2010). ‘Understanding Unequal Turnout: Education and Voting in Comparative Perspective’, Electoral Studies, 29:2, 239–48.

- Gerring, John, Strom C. Thacker, and Carola Moreno (2009). ‘Are Parliamentary Systems Better?’, Comparative Political Studies, 42:3, 327–59.

- Gherghina, Sergiu. (2013). ‘One-Shot Party Primaries: The Case of the Romanian Social Democrats’, Politics, 33:3, 185–95.

- Hazan, Reuven Y, and Gideon Rahaṭ (2010). Democracy within Parties: Candidate Selection Methods and Their Political Consequences. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Helliwell, John, and Haifang Huang (2006). How’s Your Government? International Evidence Linking Good Government and Well-Being. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Katz, Richard S, and Peter Mair (1995). ‘Changing Models of Party Organization and Party Democracy: The Emergence of the Cartel Party’, Party Politics, 1:1, 5–28.

- Kenig, Ofer, and Scott Pruysers (2018). ‘The Challenges of Inclusive Intra-Party Selection Methods’, in Guillermo Cordero and Xavier Coller (eds.), Democratizing Candidate Selection. New York: Springer International Publishing, 25–48.

- Klašnja, Marko. (2017). ‘Uninformed Voters and Corrupt Politicians’, American Politics Research, 45:2, 256–79.

- Klingemann, Hans-Dieter, Richard I. Hofferbert, and Ian Budge (1994). Parties, Policies, and Democracy. Boulder: Westview Press.

- Kunicova, Jana, and Susan Rose-Ackerman (2005). ‘Electoral Rules and Constitutional Structures as Constraints on Corruption’, British Journal of Political Science, 35:4, 573–606.

- La Raja, Raymond J., and Jonathan Rauch (2020). Voters Need Help: How Party Insiders Can Make Presidential Primaries Safer, Fairer, and More Democratic. Washington DC: Brookings Institution.

- Lehrer, Ron. (2012). ‘Intra-Party Democracy and Party Responsiveness’, West European Politics, 35:6, 1295–319.

- Mair, Peter. (2006). ‘Political Parties and Democracy: What Sort of Future?’, Central European Political Science Review, 4:13, 6–20.

- Malloy, Jonathan. (2003). ‘High Discipline, Low Cohesion? The Uncertain Patterns of Canadian Parliamentary Party Groups’, The Journal of Legislative Studies, 9:4, 116–29.

- Mishler, William, and Richard Rose (2001). ‘What Are the Origins of Political Trust?: Testing Institutional and Cultural Theories in Post-Communist Societies’, Comparative Political Studies, 34:1, 30–62.

- Morris, Stephen D, and Joseph L. Klesner (2010). ‘Corruption and Trust: Theoretical Considerations and Evidence from Mexico’, Comparative Political Studies, 43:10, 1258–85.

- Orriols, Lluis, and Guillermo Cordero (2016). ‘The Breakdown of the Spanish Two-Party System: The Upsurge of Podemos and Ciudadanos in the 2015 General Election’, South European Society and Politics, 21:4, 469–92.

- Ortega, Carmen, Fátima Recuero, José Manuel Trujillo, and Pablo Oñate (2021). ‘The Impact of Regional and National Leaders in Subnational Elections in Spain: Evidence from Andalusian Regional Elections’, Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 52:1, 133–53.

- Persson, Anna, Bo Rothstein, and Jan Teorell (2013). ‘Why Anticorruption Reforms Fail – Systemic Corruption as a Collective Action Problem’, Governance, 26:3, 449–71.

- Poguntke, Thomas, Susan E. Scarrow, Paul D. Webb, Elin H. Allern, Nicholas Aylott, Ingrid van Biezen, Enrico Calossi, Marina Costa Lobo, William P. Cross, Kris Deschouwer, Zsolt Enyedi, Elodie Fabre, David M. Farrell, Anika Gauja, Eugenio Pizzimenti, Petr Kopecký, Ruud Koole, Wolfgang C. Müller, Karina Kosiara-Pedersen, Gideon Rahat, Aleks Szczerbiak, Emilie van Haute, and Tània Verge (2016). ‘Party Rules, Party Resources and The Politics of Parliamentary Democracies: How Parties Organize in the 21st Century’, Party Politics, 22:6, 661–78.

- Poguntke, Thomas, and Paul Webb, eds. (2005). The Presidentialization of Politics: A Comparative Study of Modern Democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ranney, Austin. (1981). ‘Candidate Selection’, in David Butler, Howard R. Penniman, and Austin Ranney (eds.), Democracy at the Polls. A Comparative Study of National Elections. Washington, DC: Aei, 75–105.

- Rehmert, Jochen. (2021). ‘Behavioral Consequences of Open Candidate Recruitment’, Legislative Studies Quarterly, 46:2, 427–58.

- Rosenbluth, Frances McCall, and Ian Shapiro (2018). Responsible Parties: Saving Democracy from Itself. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Sandri, Giulia, and Antonella Seddone (2015). Party Primaries in Comparative Perspective. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Sanz, Alberto (2008). ‘Split-Ticket Voting in Multi-Level Electoral Competition: European, National and Regional Concurrent Elections in Spain’, in Cees van der Eijk and Hermann Schmitt (eds.), The Multilevel Electoral System of the EU. Mannheim: Connex, 101–37.

- Sartori, Giovanni. (2005). ‘Party Types, Organisation and Functions’, West European Politics, 28:1, 5–32.

- Scherlis, Gerardo. (2008). ‘Machine Politics and Democracy: The Deinstitutionalization of the Argentine Party System’, Government and Opposition, 43:4, 579–98.

- Schumacher, Gijs, and Nathalie Giger (2017). ‘Who Leads the Party? On Membership Size, Selectorates and Party Oligarchy’, Political Studies, 65:1_suppl, 162–81.

- Serra, Gilles. (2011). ‘Why Primaries? The Party’s Tradeoff Between Policy and Valence’, Journal of Theoretical Politics, 23:1, 21–51.

- Sharafutdinova, Gulnaz. (2010). ‘What Explains Corruption Perceptions? The Dark Side of Political Competition in Russia’s Regions’, Comparative Politics, 42:2, 147–66.

- Shomer, Yael, Gert-Jan Put, and Einat Gedalya-Lavy (2016). ‘Intra-Party Politics and Public Opinion: How Candidate Selection Processes Affect Citizens’ Satisfaction with Democracy’, Political Behavior, 38:3, 509–34.

- Singer, Matthew. (2009). Buying Voters with Dirty Money: The Relationship between Clientelism and Corruption. Rochester: Social Science Research Network.

- Solé-Ollé, Albert, and Pilar Sorribas-Navarro (2018). ‘Trust No More? On the Lasting Effects of Corruption Scandals’, European Journal of Political Economy, 55:2, 185–203.

- Sulley, Consolata R. (2022). ‘Democracy within Parties: Electoral Consequences of Candidate Selection Methods in Tanzania’, Party Politics, 28:2, 261–71.

- Tavits, Margit. (2007). ‘Clarity of Responsibility and Corruption’, American Journal of Political Science, 51:1, 218–29.

- Torcal, Mariano, and Pablo Christmann (2021). ‘Responsiveness, Performance and Corruption: Reasons for the Decline of Political Trust’, Frontiers in Political Science, 3, 676.

- Transparency International. (2022). CPI 2021 for Western Europe & European Union: Trouble Ahead for Stagnating Region. Available at https://www.transparency.org/en/news/cpi-2021-western-europe-european-union-trouble-ahead-for-stagnating-region (accessed June 2022).

- Young, Lisa. (2013). ‘Party Members and Intra-Party Democracy’, in William Cross and Richard S. Katz (eds.), The Challenges of Intra-Party Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 65–80.