Abstract

Pressures to comply with EU rules have allegedly eroded opportunities for national governments to adopt policies that they support. Conversely, research into differentiated implementation underlines that governments use their discretion to tailor supranational policies to national contexts. This study addresses these competing arguments using unique data on the implementation of EU migration issues. On the one hand, compliance with EU rules is expected to compel governments to transpose liberal migration policies, even when they favour restrictive measures. However, increased politicisation and differentiated integration are likely to increase governments’ autonomy to pursue restrictive policy preferences during transposition. The findings suggest that the constraining effect of EU policies is conditional on the importance that governments place on immigration issues and differentiated participation in the EU. Thus, it is important to consider both domestic and supranational conditions to understand fully the impact of external constraints on government policy implementation.

There is a growing perception among citizens and politicians that national governments have lost their sovereignty to international organisations. Membership and participation in international organisations such as the European Union (EU) has allegedly eroded the opportunities of governments to adopt and implement autonomously their most desirable policies. Underpinning this argument is the assumption that membership in the EU obliges governments to commit to a narrow set of policies allowed by the EU (Lefkofridi and Nezi Citation2020: 1; Mair Citation2006). As a result, governments may be compelled to institute and implement policies that diverge from their policy preferences. For example, recent empirical studies find support for governments’ declining leeway to determine their own fiscal and monetary policies (Schneider Citation2019). In a similar vein, mainstream parties have adopted restrictive stances on migration due to politicisation (Akkerman Citation2015; Alonso and Claro da Fonseca Citation2012), while most national migration policies have become more liberal (de Haas et al. Citation2018; Helbling and Kalkum Citation2018), denoting a gap between government positions and national policies (Lutz Citation2021). It is often argued that at least some of the observed differences are due to Europeanization pressures (Hampshire Citation2016; Koopmans et al. Citation2012).

Nevertheless, there are also reasons to doubt the alleged constraining effects of EU rules on domestic policies in the implementation process. The EU directives and regulations enable national authorities to institute a broad range of credible and distinct policy options to accommodate domestic demands (Franchino Citation2007). Furthermore, existing research on differentiated implementation shows that governments customise the EU rules in national legislation to address local problems and satisfy public demands (Thomann and Zhelyazkova Citation2017; Zhelyazkova and Thomann Citation2022). Therefore, it is highly questionable whether the EU member states are forced to implement policies that they do not support.

Currently, there is limited research on the impact of the EU on the opportunities of national governments to implement EU directives in accordance with their policy preferences. Thereby, this study analyses whether and under what conditions the EU directives hamper government autonomy in the legal implementation (also referred to as transposition) of EU immigration and asylum rules.

To what extent do EU asylum and migration rules constrain governments’ autonomy to transpose restrictive migration policies?

Theoretically, the study addresses the question by focussing on both national and supranational factors. On the one hand, compliance with EU rules is expected to decrease the congruence between government preferences and national legislation, when governments support restrictive migration policies. On the other hand, it is expected that the effects of external compliance pressures are less prominent, when governing parties attach high importance to their policy stances. Furthermore, national governments are also likely to respond to public demands for more national autonomy in the field of immigration due to politicisation (Morales et al. Citation2015). At the supranational level, member states are not equally constrained by the EU policy requirements (Schimmelfennig and Winzen Citation2019). Some countries enjoy flexible arrangements with the EU, where governments may decide not to participate in a specific EU asylum rule during the EU policy-making process. Previous research shows that EU negotiations affect the implementation of EU policies (Zaun Citation2017; Zhelyazkova Citation2013). However, the effect of differentiated integration on domestic outcomes has received limited attention by scholars. The study addresses the research gap by examining the relationship between differentiated integration and differentiated implementation. Finally, the constraining effects of EU rules are expected to vary across issue areas. Whereas EU asylum policies require higher standards for protection of asylum seekers, EU rules on border control and immigration allow and even prescribe restrictive immigration practices (Lavenex Citation2006; Zaun Citation2016).

In order to test hypotheses, this study examines member states’ differentiated transposition of 120 policy issues from EU directives on immigration, asylum and border control. The data-set includes directives adopted as part of the first phase of the Common European Asylum System (CEAS) and it is based on transposition reports published in the period between 2006 and 2013 (Zhelyazkova et al. Citation2016). The policy area is especially suitable for the objectives of the study. Arguably, EU asylum and immigration policies have become increasingly politicised and salient to both elites and citizens (Helbling and Kalkum Citation2018; Lutz Citation2021; Schultz et al. Citation2021). Immigration policy concerns core state powers and touches upon domestically sensitive issues of national identity and culture, where national authorities have been reluctant to concede responsibilities to supranational institutions (Lavenex Citation2006). At the same time, the EU has made enormous strides in ensuring that the fundamental rights of asylum seekers and third-country nationals (TCNs) are protected (Geddes Citation2003). Moreover, focussing on EU immigration and asylum policies enables scholars to distinguish between different levels of EU participation, as the EU member states are not bound by the same requirements to participate in this policy area (Geddes Citation2003). Thereby, it is possible to analyse directly the impact of differentiated integration on domestic policies.

The findings show that compliance with EU rules increases the gap between government policy preferences and actions when governments attach low salience to their more restrictive immigration stances. Conversely, public support for government autonomy and flexible EU participation enable governments to implement more restrictive immigration rules when they wish to do so. These results challenge ideas that membership in the EU has decreased government autonomy in the implementation of EU policies. Instead, it is important to consider both domestic and supranational conditions to understand fully the impact of external constraints on government policy choices.

Does compliance with EU rules diminish the linkage between government preferences and actions?

Recent studies identify increasing government commitments to comply with international agreements as a major source for declining government control over national policies and outcomes (Bardi Citation2014). The transfer of responsibilities to supranational authorities has allegedly compelled governments to implement policies that deviate from their policy preferences. In the context of EU integration, supranational policies are the outcome of intense negotiations between 27 member-state representatives as well as the EU Commission and the European Parliament. Consequently, the EU policies are unlikely to reflect the preferences of governments and citizens of any one country. Furthermore, policy-makers inherit international commitments made by previous governments, making it increasingly difficult to follow programmatic policy preferences.

Despite these assumptions, there is mixed evidence that EU integration has diminished government autonomy in the context of immigration policy. Studies focussing on EU asylum directives find that EU legislation exceeds the lowest common denominator. In particular, the harmonisation of European asylum standards has led to relatively high legal standards for refugees (Zaun Citation2016, Citation2017) and new supranational norms have been established to protect illegally resident immigrants from forceful expulsion (Thomann and Zhelyazkova Citation2017). In a similar vein, research on national migration policies suggests that domestic rules have become less restrictive due to Europeanization (de Haas et al. Citation2018; Helbling and Kalkum Citation2018). Nevertheless, findings on the implementation process indicate that domestic outcomes often diverge from the EU objectives (Lang Citation2020; Trauner Citation2016). These divergent findings call for a need to examine the conditions under which the EU has influence on the implementation of EU migration rules in domestic settings.

Based on preference-based explanations for compliance, member states comply with international commitments to a varying degree because governments reap significant benefits from non-compliance (Downs et al. Citation1996; Tallberg Citation2002; Thomson et al. Citation2007) or because they have been outvoted during the Council negotiations at the EU (Falkner et al. Citation2004; Thomson Citation2010). Even in the context of the relatively binding EU legislation, the EU member states differ in the extent to which they enact and implement policies in accordance with the European norms (Börzel et al. Citation2012; Versluis Citation2007). Opportunities for non-compliance increase in an enlarged Union, where supranational enforcement actors are unable to monitor fully the implementation of all EU rules across countries and heavily rely on self-reporting by the member states (Hartlapp and Falkner Citation2009). Given the potential for non-compliance, governments that support more restrictive asylum and immigration policies are more likely to implement stringent measures towards asylum seekers and TCNs. Nevertheless, compliance-seeking governments with restrictive policy preferences may still decide to prioritise conformity with EU requirements either to avoid infringement cases and domestic and international critique, or because they lack regulatory expertise to accommodate their divergent preferences. This is especially likely during transposition, as the Commission is better able to detect issues of non-compliance at the legal stages of the implementation process than in the case of practical implementation. Finally, liberal-leaning governments are expected to implement policies that are favourable to asylum seekers and TCNs because these policies are in line with their preferences.

In sum, it is expected that governments supporting restrictive immigration rules are more likely to implement and adopt policies that deviate from their policy positions, if they choose to comply with the EU rules.

Supranational constraints hypothesis: Compliance with EU rules decreases the autonomy of governments favouring restrictive measures to implement restrictive policies in the transposition of EU rules.

The conditional effect of domestic factors: government salience and public opinion

Different strands of literature challenge the uniform impact of EU integration on national policies. A popular counter-argument to the Supranational constraints hypothesis is that the EU rules help governments overcome domestic opposition to necessary policy reforms. As a result, supranational compliance pressures could even enhance the autonomy of government officials and push for the implementation of favourable EU policies that are domestically contested (Börzel et al. Citation2012). In the context of EU migration policies, autonomy-striving national ministers often seek to enhance domestic interests through cooperation at the EU level (Lavenex Citation2006). A long-standing argument in this literature is that member states’ interior ministers have used the EU as a venue to pass restrictive policies and circumvent domestic liberal veto players (Guiraudon Citation2000). Moreover, the EU rules grant extensive discretion to member states to accommodate domestic preferences and demands. As a result, even EU compliant governments are able to change or adapt the EU policies during transposition to make them suitable to the specific domestic context (Thomann Citation2019; Thomann and Zhelyazkova Citation2017). In short, it is important to acknowledge the relevance of both domestic and supranational conditions in the implementation of EU migration rules.

At the national level, the supranational constraints thesis is inconsistent with recent findings on the growing politicisation of EU policies. This research suggests that mainstream governing parties have adopted more restrictive and Eurosceptic stances in response to the rising popularity of radical right-wing parties and the politicisation of immigration issues (Akkerman Citation2015; Alonso and Claro da Fonseca Citation2012; Kriesi Citation2014). A key and necessary element of politicisation is the salience that governing parties attach to specific issues (Green-Pedersen Citation2012). First, high issue salience motivates governments to search for policy solutions that accommodate their diverging preferences. Even when national policy-makers enjoy discretion to implement the EU policies, accommodating diverging national preferences is not cost free. The more government preferences deviate from the EU policy demands, the more difficult it is to adopt and implement policies that both meet external pressures for compliance and satisfy domestic preferences. Thereby, national authorities need to mobilise resources to find appropriate policy solutions that both meet the EU objectives and correspond to their policy preferences.

Second, issue salience also affects the extent to which national representatives are able to negotiate more favourable deals at the EU level through mobilisation of bargaining resources (Warntjen Citation2012). By emphasising their concerns during EU negotiations, national representatives signal that governments will not honour the EU agreements causing other member states to make concessions. Similarly, member states that attach high salience to constraining immigration were more likely to adopt ‘hard’ bargaining strategies, which helped them successfully upload their preferences at the EU level (Zaun Citation2017: 206). As a result, the EU policies are likely to reflect the interests of national governments, increasing governments’ autonomy to implement the EU rules in a way that resonates with their policy preferences. In sum, it is expected that the emphasis (e.g. salience) that governments place on restrictive immigration policies moderates the relationship between compliance and government autonomy.

Government salience hypothesis: When governments attach high salience to adopting restrictive immigration policies, they are more likely to implement restrictive measures in the transposition of EU rules. Under these circumstances, compliance is less likely to decrease the autonomy of governments to implement restrictive measures.

Another necessary element of politicisation is public opinion regarding EU integration. The substantial transfer of political authority to supranational institutions has arguably made EU issues highly controversial in the public arena (Hooghe and Marks Citation2009). Whereas there is limited evidence that member states respond to public support in the implementation of EU policies more generally, recent studies show that politicisation improves the representation of citizen preferences in national migration policies (Ford et al. Citation2015; Lutz Citation2021; Morales et al. Citation2015). Public opinion is expected to affect the differentiated transposition of EU migration rules at least indirectly. First, the increased politicisation of migration issues has fuelled demands for more restrictive immigration policies among citizens. Even before the refugee crisis, EU citizens regularly mentioned immigration to be one of the most important issues facing their country. Consequently, relative to other policy areas, citizens formulate and express clearer preferences, and national governments are more likely to listen to the public when transposing the EU immigration and asylum policies. Second, even when citizens are not familiar with the exact EU rules, they could more easily observe when governments implement policies that diverge from their electoral pledges (Lutz Citation2021) given the heightened public interest in these policies. In this case, governments could face electoral losses if their actions convey to voters that the EU rules constrain their policy autonomy (Ruiz-Rufino and Alonso Citation2017). Public demands for more autonomous policy making are then likely to encourage national governments to pursue their restrictive policy preferences during transposition.

Government responsiveness hypothesis: When citizens support government autonomy from EU policies, governments favouring restrictive immigration policies are more likely to implement restrictive measures in the transposition of EU rules.

Supranational conditions: differentiated integration and asylum-favourability

In addition to domestic conditions, supranational factors could also affect government autonomy in EU policy implementation. Over its history, the EU has not only deepened its competences, but it has also become a ‘looser’ Union with uneven and differentiated member states’ participation in EU policy making. Differentiated integration (DI) denotes the absence of single policy that equally binds all countries (Schimmelfennig and Winzen Citation2019). For example, not all member states participate in major policy projects such as the Monetary Union, the Schengen Area, or the Area of Freedom, Security and Justice. Some member states (e.g. the United Kingdom at the time of its membership, Denmark and Ireland) are exempted from implementing the EU requirements, but national authorities could opt into specific policies during EU-level negotiations.

The literature understands DI as a response to the diversity of preferences and capacities of member states to implement EU policies. In other words, the EU makes use of flexible arrangements in order to facilitate policy making in domains characterised by salient and heterogeneous government and societal preferences (Scharpf Citation2010). Thus, DI is especially likely in issue areas with core state powers, such as immigration and asylum (Genschel and Jachtenfuchs Citation2014), where sovereignty concerns threaten to thwart agreements on common policy.

Uneven participation in the field of EU immigration and asylum is also expected to affect policy implementation. Arguably, governments who choose not to take part in specific EU legislation (opt-out decisions) are not bound by the relevant EU agreements and are thus free to pursue their own policy preferences. National authorities could still copy the EU rules they favour, but they are not subject to infringement proceedings if they fail to comply. Similarly, opting-in governments are likely to join in EU migration policies, when they hold positions aligned with the EU objectives. Finally, member states that do not enjoy flexible arrangements with the EU (full participants) are legally obliged to meet the EU requirements, and thus experience the least flexibility in policy implementation.

Differentiated integration hypothesis: Governments enjoying flexible arrangements with the EU are more likely to implement restrictive measures in the transposition of EU rules, when they favour restrictive immigration policies.

Finally, EU legislation consists of different policy dimensions that shape government autonomy when responding to EU policy demands. Allegedly, the EU migration rules are highly discretionary and focus on minimum standards. Thus, governments who support restrictive immigration rules may not necessarily incur losses to their autonomy. It is expected that the constraining effects of the EU vary across policy dimensions. On the one hand, some scholars argue that political integration in Europe has led to more restrictive immigration policies that make territorial access for TCNs more difficult (Lavenex Citation2006). Therefore, border control and immigration-related issues are likely to be in line with the preferences of governments that favour restrictive immigration. At the same time, these EU rules do not prevent governments from implementing more lenient rules, if they wish to do so. Conversely, the harmonisation of European asylum policies has improved the legal standards of refugees due to the bargaining success of countries with high regulatory capacity (Zaun Citation2016). In this case, implementation of the EU rules is associated with higher asylum favourability and member states are not allowed to go below the standards enshrined in the EU rules. Thereby, it is expected that governments face more constraints in the implementation of EU asylum rules than issues related to immigration and border control.

Asylum-favourability hypothesis: Governments favouring restrictive immigration policies are less likely to implement restrictive measures during the transposition of EU asylum rules relative to EU rules on immigration and border control.

Research design

Data and coding of (restrictive) national policies

Information about member states’ domestic outputs was obtained from a large-scale study on member states’ legal implementation of EU directives. Directives are the only instruments that oblige member states to transpose domestic policies that explicitly meet the EU objectives.Footnote1 The dataset is based on reports by external experts who were contracted by the EU Commission to assess member states’ implementation of various policy issues within EU directives. The dataset includes information about 27 member states (excluding Croatia and including the UK) and their transposition measures in relation to EU directive provisions. More information about the data collection procedure is given in the online appendix and it is described elsewhere (Zhelyazkova et al. Citation2016). This study focuses on the following EU directives (abbreviated names): Family reunification, Long-term residents, Temporary protection, Reception conditions, Victims of trafficking, Qualification, Assistance for transit, Carriers’ liability, Facilitation of unauthorised entry and stay and Mutual recognition of expulsion. While these directives were adopted in the early stages of CEAS, recent research shows that the implementation of subsequent EU asylum and migration policies followed the same logic as that of earlier directives (Zaun Citation2017).

One of the main advantages of the dataset is that it includes information about both member states’ level of compliance and differentiated (legal) implementation in relation to various target groups, including refugees, immigrants, long-term residents, etc. The data was compiled from extensive national reports, synthesis reports and Tables of Correspondence (TOCs) that outline how member states adapted separate provisions from each EU directive and their level of conformity with each specific issue. Thus, the level of analysis is a distinct issue or a provision within a directive. Inconsequential provisions that do not require national adoption were excluded from the analysis.

In this study, government autonomy is conceptualised as the relationship between government preferences and legal implementation outcomes. The assumption is that national governments autonomously implement the EU rules, if national transposition corresponds to their policy preferences. More precisely, governments with restrictive migration stances will adopt restrictive migration policies when implementing the EU rules. The measurement of restrictiveness is based on both the nature of the EU rule and expert evaluations. First, I identified the level of restrictiveness prescribed by each EU issue depending on whether it referred to obligations or rights conferred on TCNs and refugees. Second, different codersFootnote2 assessed whether the national government enacted restrictive or liberal immigration policies.Footnote3 The analysis focuses on absolute levels of restrictiveness in response to EU rulesFootnote4 based on explicit assessments by external experts, where they identified national implementation of EU rules as either ‘favourable’ or ‘restrictive’ to relevant target groups. Governments supporting restrictive immigration policies are expected to grant limited rights of TCNs and refugees in the transposition process. For example, Art. 4(2) of the directive on carriers’ liability (2001/51/EC) specifies that penalties against carriers of illegal immigrants should not interfere with member states’ obligations when immigrants seek international protection. However, Italy, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, Romania and Slovenia applied sanctions regardless of whether asylum is sought or granted, resulting in a restrictive legal implementation of the EU provision. Conversely, a member statés adoption of a provision was assessed by the external experts as favourable to the relevant target groups if national transposition granted specific rights to refugees and TCNs (e.g. healthcare to refugees beyond emergency care). Finally, it is possible that national policies implemented the EU rules without clear consequences for different immigrant groups. As there are only seven cases that fit this description, they were excluded from the analysis. The coding procedure is further described in the online appendix.

Similarly, the measure for compliance records whether a member state correctly incorporated a specific issue from an EU directive into national legislation.Footnote5 Compliance is coded as 1 if the external reports indicate that a member state fully conformed to a specific issue within an EU directive.

Government preferences, public opinion and the salience of immigration policies

In order to analyse whether legal implementation reflects government policy preferences, I compiled data on government positions on migration policy. Information about government preferences was obtained from the Chapel Hill expert surveys on party positions (Bakker et al. Citation2015). The question used in the study captures a party’s position on immigration policy on a scale from 0 (strongly favours a liberal stance on immigration) to 10 (strongly favours a restrictive policy on immigration). The Chapel Hill expert survey also includes information about the importance that political parties attach to immigration policy (range: 0–10). Both measures are weighted by the share of party seats in government at the time of the adoption of the national transposition measure.

The measure for public opinion was taken from the Eurobarometer survey, which regularly asks citizens if migration policies should be decided only nationally or jointly with the EU. It is assumed that public opinion is more hostile towards EU migration rules, if citizens think that their government should be solely responsible for the adoption of immigration policies. The measure for public opinion reflects the fraction of respondents (excluding ‘don’t know’ and refusal responses) who support exclusively national competences over immigration policy. Given that the sample sizes vary between 500 and 2000 respondents per country, I constructed a state-specific opinion variable from the Eurobarometer data using post-stratification weights rendering estimates representative for the populations in each member state. As the question was asked in multiple years, the public opinion data was matched with the year of transposition of a given policy issue by the member-state authorities.

Measuring different levels of participation in EU migration policy and issue areas

An important characteristic of EU asylum and immigration rules is that they grant flexibility to certain member states to participate in specific EU directives on a voluntary basis. For example, Denmark, Ireland and the UK (before leaving the EU) have enjoyed more flexible arrangements than other member states. Member states that chose to opt out from a directive during the EU negotiations are least constrained by the EU requirements (EU participation = 0). Governments that volunteered to adopt a specific EU rule have an intermediate level of flexibility (EU participation = 1) because opting-in governments are legally bound to follow the EU requirements. Finally, fully participating member states cannot rely on flexible arrangements at the EU level, and are most constrained by the EU immigration policies (EU participation = 2). Finally, the Asylum-favourability hypothesis is tested by distinguishing between issues related to asylum seekers and refugees (coded as 1) (Zaun Citation2016) and issues concerning border control and illegal immigration (coded as 0). The information is based on the content of the provisions and the measure was cross-validated by different coders.

Control variables

The analysis further accounts for relevant characteristics of the policy-making process that could affect governments’ ability to pursue their policy interests. For example, government flexibility could increase because participating member states are given extensive discretion to implement the EU rules (Franchino Citation2007). Discretion is measured at the issue level and records whether a specific provision relates to an optional requirement (coded as 1) for all the member states or not (coded as 0). Furthermore, existing policies adopted by previous incumbents could pose an additional constraint on governments to enact and implement restrictive migration policies (Zaun Citation2016). The reports include information about member states’ pre-existing policies for each EU issue prior to the EU directive adoption. The variable takes the value of 1 if there is a pre-existing national policy on a given issue (otherwise, 0). Another important indicator is the salience that citizens attach to immigration issues. This is measured as the share of citizens who mentioned immigration as one of the most important issues in their country in the relevant Eurobarometer surveys. The salience measure is based on state-specific post-stratification weights. Finally, the analysis distinguishes between Central and Eastern European (CEE) member states and EU-15 countries. The CEE member states are generally more reluctant to adopt the EU migration rules. Most of the directives were adopted before these countries joined the EU and CEE representatives were not able to push forward their policy preferences or express opposition towards the EU requirements. The descriptive statistics of the main variables are presented in the online appendix.

Analysis

The hypotheses are tested using logistic regression models with directive-level fixed effects and robust standard errors clustered in policy issues. Furthermore, the observations are also nested in both issues and member states. As a robustness check, I conducted crossed-level analysis with random effects at the country and issue levels (see Table A4 in the online appendix).

presents the analysis of member states’ legal implementation of EU immigration and asylum policies. Model 1 shows the relationship between government preferences for strict immigration policies and restrictive implementation of EU policies. Therefore, government autonomy would imply a positive significant effect of government support for tough immigration on restrictive implementation of the EU policies. Model 2 tests the Supranational constraints hypothesis by analysing whether member states’ compliance with EU issues affects the relation between government preferences and transposition outcomes. Models 3 and 4 test the conditional effects of government salience (Model 3) and public opinion (Model 4). Finally, Models 5 and 6 analyse whether different levels of EU participation (Model 5) and EU asylum favourability (Model 6) affect the relation between government preferences and domestic policy responses to EU policies.

Table 1. Analysis of government preferences – policy relation in member states’ implementation of EU asylum and immigration policies.

The results presented in Model 1 show no significant relationship between governments’ preferences on immigration and the likelihood that member states adopt restrictive migration policies in response to EU legislation. In other words, governments supporting tough immigration measures do not necessarily execute preferred policies when transposing the EU migration rules. Conversely, compliance with EU issues is negatively associated with restrictive domestic policies enacted in response to EU legislation. The average probability that compliance with an EU issue leads to a restrictive migration policy is only 0.14 and it increases to 0.62 when a government fails to conform to the EU objectives. This finding remains robust when both domestic and supranational factors (i.e. level of EU participation, discretion, type of issue, etc.) are included in the analysis. The negative effect of compliance on restrictive implementation underscores ideas that EU migration rules allow for more leniency and favourable conditions for immigrants and asylum seekers (de Haas et al. Citation2018; Helbling and Kalkum Citation2018; Zaun Citation2016). Conversely, compliant member states do not implement more restrictive policies than prescribed by the EU rules.

Model 2 of explicitly tests the constraining effect of compliance with EU obligations on governments’ autonomy by including an interaction term between government immigration stances and compliance (Compliance*Gov’t Position). The non-significant interaction coefficient shows that the relationship between government policy preferences and transposition outcomes does not differ for non-compliant and law-observant governments. Contrary to the Supranational Constraints hypothesis, non-compliant governments are not necessarily better able to enact and implement policies that reflect their restrictive interests.

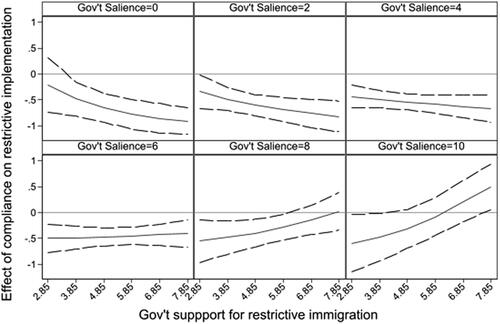

Models 3 and 4 show that the gap between government preferences and policy outcomes is conditional on government salience (Model 3) and public opinion (Model 4). It was expected that the alleged constraining effect of EU compliance is weaker when governments attach high salience to their preferences on immigration issues. This complex relationship is tested with a three-way interaction including compliance, government position and government salience on immigration policy. Model 3 includes the main components of the interaction effect as well as the multiplicative terms for all different combinations of the three variables (Brambor et al. Citation2006). The significant three-way interaction coefficient suggests that the extent to which compliance decreases the likelihood of restrictive migration policies depends on both the preferences and the importance that governing parties attach to immigration issues. illustrates the effect of compliance on government policies at varying levels of government support and salience for restrictive immigration. More precisely, compliance has a negative effect on the ability of governments to enact preferred restrictive policies, when they attach low salience to such measures. However, when governments strongly favour restrictive immigration and consider these issues highly important, compliance with the EU requirements could even result in more restrictive implementation. This finding is in line with studies underpinning the existence of differentiated national responses to EU policy requirements (Thomann Citation2019). Governments that attach high salience to immigration are more likely to invest resources in search for policy solutions that satisfy both the EU objectives and their national preferences for restrictive immigration. This finding also resonates with research showing that increased salience positively affects member states’ incentives for policy learning. For example, Mastenbroek et al (Citation2022) find that member states strongly affected by the increased influx of refugees were more likely to look for solutions by engaging with the European Migration Network (Mastenbroek et al. Citation2022).

Figure 1. Marginal effect of compliance on government autonomy to execute preferred restrictive policies in the implementation of EU migration issues at different levels of salience.

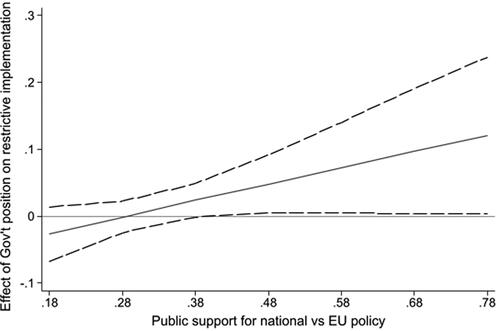

Based on the analysis of Model 4, public opinion significantly affects the relationship between government preferences and restrictive implementation of EU migration policies. The significant positive interaction coefficient of Gov’t Position*Opinion suggests that governments supporting restrictive immigration policies are more likely to adhere to their preferences in the implementation of EU policies when citizens support exclusive national competences. illustrates how the relationship between government preferences and legal implementation varies due to changes in public support for national sovereignty on immigration issues. In cases where more than 38% of national respondents favour autonomous government policies on immigration, national authorities are more likely to translate their preferences for tough immigration into restrictive immigration policies. This finding supports the conjecture that public opinion creates ‘audience costs’ for governing parties, who risk electoral losses if they convey inability to pursue their policy preferences in the transposition of EU policies.

Figure 2. Marginal effect of government preferences for restrictive immigration rules at different levels of public support for exclusive national competences on immigration.

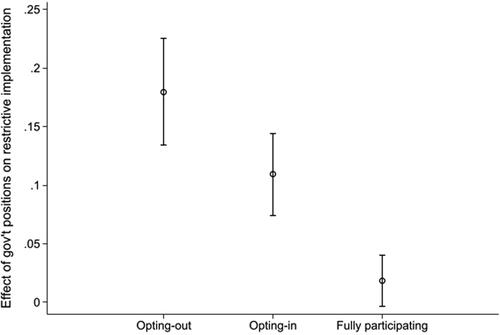

Finally, Models 5 and 6 test the conditional effects of supranational factors. It was hypothesised that flexible arrangements help national authorities enhance state interests for restrictive immigration (Differentiated Integration hypothesis). Model 5 analyses whether EU participation decreases the likelihood that governments wishing to restrict immigration will enact such measures. Furthermore, shows the effect of government preferences at different levels of EU participation. As expected, both opting-out and opting-in member states are significantly more likely to adopt policies reflecting their restrictive policy preferences than fully participating countries. However, the effect could be endogenous. Member states that traditionally support more restrictive EU immigration policies have negotiated flexible arrangements with the EU to preserve control over national borders. This argument is also supported by findings on member states’ negotiation strategies. Governments with salient restrictive preferences are more likely to engage successfully in hard bargaining and negotiate beneficial deals at the EU level (Zaun Citation2017), including flexible participation in the EU asylum and immigration policies.

Figure 3. Marginal effect of government preferences for restrictive immigration policy at different levels of EU participation.

Model 6 analyses whether the relationship between government preferences and implementation outcomes varies across different types of issue within the field of immigration and asylum (Helbling and Kalkum Citation2018; Lutz Citation2021; Schultz et al. Citation2021). The constraining effects of the EU were expected to be stronger for asylum policies than for issues concerning border control and labour migration (Zaun Citation2016). The results in confirm that EU issues related to asylum are adopted less restrictively than issues concerning border control and immigration (see Models 1–5). However, the non-significant interaction Gov’t Position*Asylum suggests that the relationship between government preferences does not vary across different types of EU issue.

Robustness analysis

The results from were cross-checked using multilevel models and alternative statistical techniques to control for potential endogeneity. I applied cross-classified analysis with two random effects at the member state and issue level (Table A4 in the online appendix). While implementation outcomes are nested in both countries and EU directive provisions, the variables already account for most country-level variation (based on the miniscule standard deviation in Table A4). The robustness analysis further controls for potential endogenous and simultaneous decision-making processes. Decisions to comply with specific EU issues are likely to be endogenous to government preferences, public opinion, varying levels of EU participation, as well as unaccounted country- and issue-level characteristics. Furthermore, governments take decisions in relation to compliance and restrictive immigration simultaneously, based on their policy preferences and the costs from non-compliance. Therefore, I also applied structural equation models (SEM) with simultaneous and endogenous processes. Tables A5 and A6 present two separate multilevel models with random effects at the issue and country levels. While most results do not substantially deviate from the main findings, the conditional effect of public opinion loses significance in the robustness analysis. Finally, the analysis in Table A7 accounts for the effects of government effectiveness and changes in governing parties between the adoption and the implementation of EU directives, as these factors could affect how governments respond to EU policies during the transposition process.

Conclusions

The main objective of this study was to revisit academic debates regarding the obstructing effects of EU rules on member states’ autonomy to design policies that reflect government preferences. Whereas existing research focuses on EU membership as a major constraint on government policies (Koopmans et al. Citation2012; Peters Citation2021), I argue that compliance with specific EU rules more directly captures the causal mechanism behind the impact of EU policy demands. Furthermore, the constraining effects of EU rules are heavily contested because EU governments use their discretion to implement supranational objectives reflecting domestic preferences (Thomann and Zhelyazkova Citation2017; Zhelyazkova and Thomann Citation2022). The analysis shows that the constraining effect of compliance is present when governments do not attach high importance to immigration issues. Under these conditions, national authorities are reluctant to mobilise resources to shape the EU rules both domestically and internationally. Conversely, public support for more government sovereignty in immigration policy leads to restrictive implementation of EU migration rules when governments support such measures, although the effect is not robust. At the supranational level, differentiated integration improves the linkage between government preferences and implementation actions. Both non-participating and voluntarily participating member states adopted more restrictive immigration policies, when governments supported such measures. Thus, differentiated integration could be a successful strategy in resolving tensions between EU policy demands and domestic opposition, not only at the level of EU policy making but also during implementation.

The findings from this study have theoretical and empirical implications for different strands of literature on Europeanization, differentiated EU implementation and migration policies. First, studies emphasising the constraining effects of EU policies on government autonomy do not account for the incentives of political actors to customise the EU rules (Thomann Citation2019; Zhelyazkova and Thomann Citation2022). Whereas most research has studied member states’ conformity with EU directives, we still lack understanding of the consequences of compliance for domestic policies and outcomes. On the other hand, research on differentiated implementation does not fully explain observed patterns of convergence in migration policies in Europe (de Haas et al. Citation2018; Helbling and Kalkum Citation2018). Therefore, future research should link questions about government autonomy and differentiated implementation more systematically. Second, the effect of differentiated integration on transposition underlines important relations between EU-level decision making and national implementation outcomes. Member states are likely to adopt different bargaining strategies during EU negotiations that reflect their implementation capacity and the salience they attach to migration. Existing research shows that governments placing more importance on migration adopt harder bargaining stances during EU policy making (Zaun Citation2017, Citation2022). As a result, national representatives are better able to ensure that EU policies reflect national interests. Indeed, other studies in this special issue suggest that differentiated implementation is influenced by the ability of governments to upload their policy preferences during EU policy making. Given the lack of available data on bargaining strategies in relation to specific EU directives, future research should further our understanding of the effects of EU negotiations on differentiated implementation.

Third, the study contributes to the conceptualisation of differentiated implementation. Most research on the topic studies variations between EU rules and national policies on relevant dimensions (Thomann Citation2019; Thomann and Zhelyazkova Citation2017). However, it is not only important to understand how national policies deviate from the EU rules, but also the impact of these differences on politically and societally relevant processes and outcomes. While this study focussed on the congruence between government policy preferences and national legal responses to EU law, future research should also analyse whether and how differentiated implementation facilitates government responsiveness to public opinion and member states’ problem-solving capacities.

Fourth, the findings from the study provide insights for research on immigration and asylum policy both at the EU and the national level. At the national level, governments favouring restrictive immigration do not directly translate their preferences into restrictive migration policies when implementing the EU rules. This finding lends support to the ‘gap-hypothesis’ regarding the disconnect between government positions and policy actions in the area of immigration and asylum (Lutz Citation2021). Nevertheless, increased politicisation of migration goes along with a stronger preference-policy linkage (Morales et al. Citation2015). It is worthwhile noting that public opinion affects implementation outcomes only indirectly, when governments already support more restrictive immigration policies. National migration policies are the outcome of complex interactions between various stakeholders, including courts, bureaucracies, interest groups and civil society organisations (Geddes Citation2003; Lahav and Guiraudon Citation2006), all of which could steer government policies away from the public mood.

Finally, this study analysed the differentiated transposition of EU migration directives in the period prior to the EU refugee crisis. Arguably, recent studies show that the increased influx of refugees into Europe has transformed government preferences and even the most liberal countries implemented restrictive conditions for asylum seekers (Zaun Citation2017, Citation2022). Therefore, it is likely that the findings are still relevant and the effects will be even more pronounced after the refugee crisis. As the salience of migration issues increases and governments support more restrictive immigration stances, member states are even more likely to transpose the EU issues restrictively. It is questionable, however, whether domestic implementation is in line with existing EU policies. Further work is needed to unpack the impact of the crisis on the practical implementation of EU asylum and immigration policies.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (787.7 KB)Acknowledgements

This article has greatly benefited from the helpful suggestions of the co-editors of the special issue ‘Differentiated policy implementation in the European Union’: Sebastiaan Princen, Eva Ruffing and Eva Thomann. The author would like to thank Brigitte Pircher, Rik Joosen, Markus Haverland, Geske Dijkstra, Michal Onderco and two anonymous WEP reviewers for their constructive comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Asya Zhelyazkova

Asya Zhelyazkova is Assistant Professor in European Politics and Public Policy at the Department of Public Administration and Sociology (DPAS), Erasmus University Rotterdam. Her research focuses on member states’ compliance and implementation of EU policies, delegation in the EU, and responsiveness of EU policies. Her recent work has appeared in journals such as the European Journal of Political Research, European Union Politics, Journal of European Public Policy, and the Journal of Common Market Studies. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 Other binding EU instruments such as regulations and decisions are directly applicable and do not require national governments to adopt implementing instruments. The study focuses on transposition because practical implementation is the responsibility of street-level bureaucrats and governments have a less decisive role.

2 Two different coders were involved in coding the data on the dependent variable and on compliance. The inter-coder reliability ranges between 95 and 98 percent. A case was excluded from the analysis, if no agreement was reached about the coding.

3 The coding of restrictiveness is based on the explicit assessments of external experts. Therefore, the distinction between restrictive and liberal immigration policy is context specific and depends on the EU issue. For EU issues related to immigration and border control, restrictive policies refer to stringent entry requirements and immigration control mechanisms, while liberal immigration policies impose few entry barriers. In the context of asylum and integration, restrictive immigration pertains to limited legal rights and social benefits granted to migrants and refugees already settled in the country, whereas liberal policies legally guarantee multiple rights to migrants and give them access to welfare benefits under the same conditions as country nationals.

4 Studies of customization analyse the extent to which national rules differ in their restrictiveness relative to a specific EU rule (Thomann and Zhelyazkova Citation2017; Zhelyazkova and Thomann 2020). However, I do not aim to explain the extent to which national policies deviate from the EU policies, but whether and under what conditions EU rules restrict governments in implementing policies that diverge from their policy preferences.

5 It is important to note that the data design is cross-sectional, as member states generally implement and comply with specific EU rules at a specific point in time. Thus, the unit of analysis is the transposition of an EU issue by a given member state.

References

- Akkerman, Tjitske (2015). ‘Immigration Policy and Electoral Competition in Western Europe: A Fine-Grained Analysis of Party Positions over the Past Two Decades’, Party Politics, 21:1, 54–67.

- Alonso, Sonia, and Saro Claro da Fonseca (2012). ‘Immigration, Left and Right’, Party Politics, 18:6, 865–84.

- Bakker, Ryan, et al. (2015). ‘Measuring Party Positions in Europe: The Chapel Hill Expert Survey Trend File, 1999–2010’, Party Politics, 21:1, 143–52.

- Bardi, Luciano (2014). ‘Political Parties, Responsiveness, and Responsibility in Multi-Level Democracy: The Challenge of Horizontal Euroscepticism’, European Political Science, 13:4, 352–64.

- Börzel, Tanja, T. Hofmann, and D. Panke (2012). ‘Caving In or Sitting It Out? Longitudinal Patterns of Non-Compliance in the European Union’, Journal of European Public Policy, 19:4, 454–71.

- Brambor, Thomas, William Roberts Clark, and Matt Golder (2006). ‘Understanding Interaction Models: Improving Empirical Analyses’, Political Analysis, 14:1, 63–82.

- de Haas, Hein, Katharina Natter, and Simona Vezzoli (2018). ‘Growing Restrictiveness or Changing Selection? The Nature and Evolution of Migration Policies’, International Migration Review, 52:2, 324–67.

- Downs, George W., David M. Rocke, and Peter N. Barsoom (1996). ‘Is the Good News about Compliance Good News about Cooperation?’, International Organization, 50:3, 379–406.

- Falkner, Gerda, Miriam Hartlapp, Simone Leiber, and Oliver Treib (2004). ‘Non-Compliance with EU Directives in the Member States: Opposition through the Backdoor?’, West European Politics, 27:3, 452–73.

- Ford, Robert, Will Jennings, and Will Somerville (2015). ‘Public Opinion, Responsiveness and Constraint: Britain’s Three Immigration Policy Regimes’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 41:9, 1391–411.

- Franchino, Fabio (2007). The Powers of the Union. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Geddes, Andrew (2003). The Politics of Migration and Immigration in Europe. London: SAGE Publications.

- Genschel, Philipp, and Markus Jachtenfuchs (2014). ‘Introduction: Beyond Market Regulation. Analysing the European Integration of Core State Powers’, in Philipp Genschel and Markus Jachtenfuchs (eds.), Beyond the Regulatory Polity?.

- Green-Pedersen, Christoffer (2012). ‘A Giant Fast Asleep? Party Incentives and the Politicisation of European Integration’, Political Studies, 60:1, 115–30.

- Guiraudon, Virginie (2000). ‘European Integration and Migration Policy: Vertical Policy-Making as Venue Shopping’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 38:2, 251–71.

- Hampshire, James (2016). ‘European Migration Governance since the Lisbon Treaty: Introduction to the Special Issue’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 42:4, 537–53.

- Hartlapp, Miriam, and Gerda Falkner (2009). ‘Problems of Operationalization and Data in EU Compliance Research’, European Union Politics, 10:2, 281–304.

- Helbling, Marc, and Dorina Kalkum (2018). ‘Migration Policy Trends in OECD Countries’, Journal of European Public Policy, 25:12, 1779–97.

- Hooghe, Liesbet, and Gary Marks (2009). ‘A Postfunctionalist Theory of European Integration: From Permissive Consensus to Constraining Dissensus’, British Journal of Political Science, 39:1, 1–23.

- Koopmans, Ruud, Ines Michalowski, and Stine Waibel (2012). ‘Citizenship Rights for Immigrants: National Political Processes and Cross-National Convergence in Western Europe, 1980-2008’, American Journal of Sociology, 117:4, 1202–45.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter (2014). ‘The Populist Challenge’, West European Politics, 37:2, 361–78.

- Lahav, Gallya, and Virginie Guiraudon (2006). ‘Actors and Venues in Immigration Control: Closing the Gap between Political Demands and Policy Outcomes’, West European Politics, 29:2, 201–23.

- Lang, Iris Goldner (2020). ‘No Solidarity without Loyalty: Why Do Member States Violate EU Migration and Asylum Law and What Can Be Done?’, European Journal of Migration and Law, 22:1, 39–59.

- Lavenex, Sandra (2006). ‘Shifting Up and Out: The Foreign Policy of European Immigration Control’, West European Politics, 29:2, 329–50.

- Lefkofridi, Zoe, and Roula Nezi (2020). ‘Responsibility versus Responsiveness…to Whom? A Theory of Party Behavior’, Party Politics, 26:3, 334–46.

- Lutz, Philipp (2021). ‘Reassessing the Gap-Hypothesis: Tough Talk and Weak Action in Migration Policy?’, Party Politics, 27:1, 174–86.

- Mair, Peter (2006). ‘Political Parties and Party Systems’, in Paolo Graziano and Maarten P. Vink (eds.), Europeanization: New Research Agendas, 154–66.

- Mastenbroek, Ellen, Reini Schrama, and Dorte Sindbjerg Martinsen (2022). ‘The Political Drivers of Information Exchange: Explaining Interactions in the European Migration Network’, Journal of European Public Policy, 29:10, 1656–76.

- Morales, Laura, Jean Benoit Pilet, and Didier Ruedin (2015). ‘The Gap between Public Preferences and Policies on Immigration: A Comparative Examination of the Effect of Politicisation on Policy Congruence’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 41:9, 1495–516.

- Peters, Yvette (2021). ‘Social Policy Responsiveness in Multilevel Contexts: How Vertical Diffusion of Competences Affects the Opinion-Policy Link’, Governance, 34:3, 687–705.

- Ruiz-Rufino, Rubén, and Sonia Alonso (2017). ‘Democracy without Choice: Citizens’ Perceptions of Government Autonomy during the Eurozone Crisis’, European Journal of Political Research, 56:2, 320–45.

- Scharpf, Fritz W. (2010). ‘The Asymmetry of European Integration, or Why the EU Cannot Be a “Social Market Economy”’, Socio-Economic Review, 8:2, 211–50.

- Schimmelfennig, Frank, and Thomas Winzen (2019). ‘Grand Theories, Differentiated Integration’, Journal of European Public Policy, 26:8, 1172–92.

- Schneider, Christina J. (2019). The Responsive Union: National Elections and European Governance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Schultz, Caroline, Philipp Lutz, and Stephan Simon (2021). ‘Explaining the Immigration Policy Mix: Countries’ Relative Openness to Asylum and Labour Migration’, European Journal of Political Research, 60:4, 763–84.

- Tallberg, Jonas (2002). ‘Paths to Compliance: Enforcement, Management, and the European Union’, International Organization, 56:3, 609–43.

- Thomann, Eva (2019). Customized Implementation of European Union Food Safety Policy. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Thomann, Eva, and Asya Zhelyazkova (2017). ‘Moving beyond (Non-)Compliance: The Customization of European Union Policies in 27 Countries’, Journal of European Public Policy, 24:9, 1269–88.

- Thomson, Robert (2010). ‘Opposition through the Back Door in the Transposition of EU Directives’, European Union Politics, 11:4, 577–96.

- Thomson, Robert, René Torenvlied, and Javier Arregui (2007). ‘The Paradox of Compliance: Infringements and Delays in Transposing European Union Directives’, British Journal of Political Science, 37:4, 685–709.

- Trauner, Florian (2016). ‘Asylum Policy: The EU’s “Crises” and the Looming Policy Regime Failure’, Journal of European Integration, 38:3, 311–25.

- Versluis, Esther (2007). ‘Even Rules, Uneven Practices: Opening the “Black Box” of EU Law in Action’, West European Politics, 30:1, 50–67.

- Warntjen, Andreas (2012). ‘Measuring Salience in EU Legislative Politics’, European Union Politics, 13:1, 168–82.

- Zaun, Natascha (2016). ‘Why EU Asylum Standards Exceed the Lowest Common Denominator: The Role of Regulatory Expertise in EU Decision-Making’, Journal of European Public Policy, 23:1, 136–54.

- Zaun, Natascha (2017). EU Asylum Policies: The Power of Strong Regulating States. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Zaun, Natascha (2022). ‘Fence-Sitters No More: Southern and Central Eastern European Member States’ Role in the Deadlock of the CEAS Reform’, Journal of European Public Policy, 29:2, 196–217.

- Zhelyazkova, Asya (2013). ‘Complying with EU Directives’ Requirements: The Link between EU Decision-Making and the Correct Transposition of EU Provisions’, Journal of European Public Policy, 20:5, 702–21.

- Zhelyazkova, Asya, Cansarp Kaya, and Reini Schrama (2016). ‘Decoupling Practical and Legal Compliance: Analysis of Member States’ Implementation of EU Policy’, European Journal of Political Research, 55:4, 827–46.

- Zhelyazkova, Asya, and Eva Thomann (2022). ‘“I Did It My Way”: Customisation and Practical Compliance with EU Policies’, Journal of European Public Policy, 29:3, 427–47.