Abstract

According to the optimistic reading of the trust deficit in contemporary democracies, an increasingly non-religious and presumably more rational citizenry is naturally inclined to distrust public institutions. This modern shift is viewed as a positive check that can supposedly improve representative government. This article proposes a more nuanced understanding of the influence of supernatural beliefs on institutional trust. Specifically, the article moves beyond the popular analytical dichotomy between the religious and the non-religious by separating the non-religious into a non-believer segment and a segment hitherto overlooked by studies of political trust: unconventional or heterodox believers (e.g. in astrology and lucky charms, but not in conventional religion). Using comparative data from the International Social Survey Programme, the study finds that heterodox believers, similarly to non-believers, tend to distrust institutions, albeit for very different reasons. The previously ignored role of heterodox beliefs points to grave implications regarding the current trust deficit.

The rise of a more rational and typically secular citizenry is a popular evolutionary argument regarding the decline in institutional trust in most mature democracies (see versions in Dalton Citation2004; Dalton and Welzel Citation2014; Inglehart Citation1997, Citation1999; Welzel Citation2013). Although the secularisation process itself has been a controversial concept (Norris and Inglehart Citation2004: 11–14), this remains a familiar modernisation argument. It tends to view religious citizens as passive towards political authority and reconciled with traditional institutions, while treating secular-rational citizens as more demanding of the political system and inclined to question authority structures. A product of advancing modernity and rising educational attainment, this ‘critical’ secular-rational citizenry exercises a constructive type of scepticism towards the system, while remaining engaged with the democratic process (cf. Norris Citation1999). The current trust deficit therefore could be a healthy one, as less trustful yet rational citizens are key to maintaining viable and well-performing democracies. Nonetheless, recent waves of popular discontent with public-facing institutions in most advanced democracies suggest more complex processes in operation (Bertsou Citation2019; Foa and Mounk Citation2016; Van Prooijen et al. Citation2022).

We propose that this optimistic reading rests, in effect, on a problematic dichotomy between the religious and the (presumably rational) non-religious; and that this dichotomous approach may lead to an erroneous diagnosis of the trust deficit in contemporary democracies. Rather than assuming that all non-religious individuals are necessarily immune to supernatural beliefs, we highlight a third group: those who are not religious in the conventional sense but instead hold unconventional, paranormal or magical (hereafter, heterodox) beliefs in practices such as astrology, lucky charms, divination and faith healing. Compared to religious believers, heterodox believers are individualistic and distrustful of authority. On the other hand, they are less prone to logical critical reasoning than are actual non-believers, who eschew supernatural beliefs, either heterodox or religious ones. In other words, heterodox believers do not harbour the constructive scepticism towards public institutions that characterises non-believers.

Despite their robust presence throughout history and, especially, in modern societies, heterodox believers have been largely ignored by political scientists. Yet, they have received significant attention by sociologists and psychologists under various labels: ‘spiritual but not religious’, ‘post-Christian spirituality’, ‘believing but not belonging’, ‘paranormal, alternative or parallel beliefs’ and the catch-all ‘New Age’ categorisation (e.g. Fuller Citation2001; Heelas Citation1996; Lambert Citation2006; Van Prooijen et al. Citation2022; Wilkins-Laflamme Citation2021; Willard and Norenzayan Citation2017). We summarise all these labels under our ‘heterodox’ category to capture unconventional beliefs in supernatural forces, which deviate from the conventional doctrinal confines of organised religion.

We explore the unexamined role of heterodox beliefs in institutional trust by using pooled comparative data from the waves (1991, 1998 and 2008) covered by the cumulated Religion dataset of the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP Research Group Citation2019). We find that, according to our conceptually rigorous classification of human belief systems (religious, heterodox, non-believer), heterodox beliefs are indeed prevalent in contemporary societies. While there is considerable cross-national variation, roughly one third of survey respondents are heterodox believers. Multilevel regression models show that heterodox believers harbour attitudes that differ from those of religious believers and non-believers alike. Specifically, unlike religious believers but similar to non-believers, heterodox believers are more likely to distrust public institutions. However, further analysis shows that heterodox believers distrust public institutions for quite different reasons; they hold strong anti-science attitudes in sharp contrast to the science-endorsing non-believers. These findings differentiate heterodox believers from both the idealised ‘critical’ citizenry (non-believers) and the more trustful religious believers.

This study presents a novel, systematic attempt to explore the political orientations of heterodox believers towards established authority structures. Its findings suggest that the steady erosion of conventional religiosity through the secularisation process that is observable in many modern societies will not lead necessarily to a rational citizenry of logical positivists that ‘follow the science’. Such an outcome would have been a boon for the quality of public reasoning as a basic input of government. Instead, this secularisation process is compatible with the substantial presence of non-religious citizens who are less trusting in science and public institutions, and who endorse often arbitrary, naïve beliefs. This process remains under-examined by studies of institutional trust and systemic support, as it is concealed under the customary dichotomy of ‘religious versus non-religious’ (e.g. Marien and Hooghe Citation2011: 275; Mishler and Rose Citation2001: 49). This is despite robust challenges to the assumed internal homogeneity of these two population segments (Campbell et al. Citation2021; Layman et al. Citation2021; Voas Citation2009; Wilkins-Laflamme Citation2021).

More generally, by moving past this dichotomy the present study contributes to a wider attempt to understand the defining feature of twenty-first century politics so far: rising popular distrust of the established order, along with the triggering and leveraging of this distrust by political entrepreneurs (Foa and Mounk Citation2016: 15–16). This turns into an urgent question during times of uncertainty and emergency, which require a more interventionist role from public institutions and the mass acceptance of that role by citizens (Goetz and Martinsen Citation2021; Marien and Hooghe Citation2011).

Heterodoxy: neither religious nor rational

Belief structures strongly shape political attitudes and behaviours. When it comes to people’s spiritual lives, political scientists have devoted most attention to the distinction between ‘religious’ and ‘non-religious’, presumably more rational, thinking and how this distinction affects political outcomes such as systemic legitimacy and institutional support (e.g. Inglehart Citation1997; Norris and Inglehart Citation2019; Verba et al. Citation1995). The ongoing public debate regarding the antithetical nature of faith and science, for example, is a prominent iteration of this dichotomous view of people’s spiritual experiences (Dawkins Citation2006).

We question this popular analytical distinction between the conventionally religious and the (supposedly rational) non-religious as a standard explanation in the study of political attitudes and behaviour. This line of thinking in political science downplays a critical type of beliefs that has concerned the fields of sociology and psychology; that is, unconventional, paranormal or magical beliefs (i.e. heterodoxy) (Heelas Citation1996; Houtman and Aupers Citation2007; Van Prooijen et al. Citation2022; Wilkins-Laflamme Citation2021; Willard and Norenzayan Citation2017). Heterodox beliefs entail a host of supernatural-oriented ideas and practices such as magic and witchcraft, faith healing, astrology and other types of divination. Heterodox beliefs, similar to conventional religious beliefs, postulate some kind of superhuman agency that interferes with human and natural affairs, and deal with phenomena falling outside material existence (Norbeck Citation1961: 11, 31). However, unlike conventional religious beliefs, which are characterised by doctrinal complexity, priestly authority, and extensive institutionalisation (McGuire Citation2007: 188), heterodox beliefs have not undergone a similar historical process of ethical rationalisation that minimises contradictions and unanswered questions (e.g. as in the case of Christian apologetics). Unlike organised religions and their clergy, heterodox beliefs do not rely on a fixed and coherent doctrine, while their practitioners usually lack vocational qualifications.

Heterodox beliefs also lack the socially-binding and conformist functions that are key to conventional religious faith. Feelings of belonging to a larger visible group of like-minded individuals, and the belief that the social order is not arbitrary but consecrated by an officially recognised actor (e.g. an institutional faith) that mediates the interaction of the individual with a superhuman agent are considered fertile ground for producing compliance, prosociality and submissiveness (Davis and Robinson Citation1999; Graham and Haidt Citation2010; Saroglou et al. Citation2004). These functions of conventional religious belief and practice as an expedient for creating prosocial and pro-authority feelings are foundational in the social sciences (Durkheim Citation1965). The field of civil religion research is a strong application of this thesis, describing a conflation between veneration of the land’s God and veneration of secular authority and its institutions (Coleman Citation1970).

On the other hand, heterodox beliefs, in their dealing with the supernatural and spiritual realm, are also evidently different from rational thinking. They depend on an intuitive way of thinking that reflects an arbitrary ‘feeling of rightness’ (Pennycook et al. Citation2012: 336). As a case in point, consider the popular belief that the relative trajectory of celestial bodies can predict contemporary human affairs, a belief usually held without having access to some kind of argumentation or the underlying ‘technology’ of prediction (Adorno Citation1957: 15–16, 84). Recent advances in psychology and cognitive science point to critical differences between heterodox beliefs and rational thinking (Kahneman Citation2011; Pennycook et al. Citation2015). As argued by dual-process cognition theory, heterodox and other supernatural beliefs reflect an intuitive and non-analytic cognitive process (Type 1), as opposed to the analytic mode of rational thinking (Type 2). Rational thinking requires more cognitive resources and reflects the propensity to use objective information in order to question and reject misleading intuitions (Pennycook et al. Citation2012: 335–36). Experimental evidence in cognitive styles singles out heterodox supernatural beliefs, together with conspiracist ideation, as a type of cognitive process prone to ‘epistemically suspect’ thinking (Pennycook et al. Citation2015: 427).

The presence of heterodox beliefs has been largely ignored by political scientists, despite the substantial numbers of individuals that report such beliefs in modern societies. This has a lot to do with their lower-status, individualistic and informal nature, features that underestimate and disguise the presence of these beliefs in the historical record, including in survey research (Scott Citation1990). The following discussion develops our expectation of a negative influence of heterodox beliefs on institutional trust as well as a possible mechanism that we can test empirically. It draws largely on the analytical distinction among (conventional) religious belief, (unconventional) heterodox belief and non-belief (neither of the above) types.

The impact of belief structure on institutional trust

We focus on institutional trust to explore how heterodox beliefs may affect an important aspect of mass political attitudes. The much-lamented ongoing decline of political trust in many consolidated democracies justifies the substantial number of empirical studies that have been devoted to documenting the sources, forms and consequences of such trust. As a basic orientation towards political authority and public institutions, political trust is critical for the long-term viability and stability of any form of complex social structure (Levi and Stoker Citation2000; Mishler and Rose Citation2001; Ruck et al. Citation2020; Warren Citation1999). It is a key manifestation of citizens’ underlying, diffuse support for a regime (Citrin Citation1974; Dalton Citation2004; Miller Citation1974; Norris Citation1999), and is required for individual compliance with laws and regulations and more generally, for systemic stability (Barber Citation1983; Foa and Mounk Citation2016; Hetherington Citation1998; Marien and Hooghe Citation2011; Zelditch Citation2001).

Heterodoxy: an antagonistic function

The ambiguous relationship between supernatural beliefs and confidence in authority structures has a long intellectual pedigree (Billings and Scott Citation1994: 174). Consider the original negative Marxist view of religion as the ideological basis of subservience and legitimacy of exploitation (Marx Citation1975), and the positive view among Marx’s disciples of religion, especially its folk or deviating forms, as a breeding ground of protest and revolt (Engels Citation1935). Contemporary anecdotes of the latter reading abound. ‘Witches are influencers who use the hashtag #witchesofinstagram to share horoscopes, spells and witchy memes, and they are anti-Trump resistance activists carrying signs that say “Hex the Patriarchy”’ reports The New York Times (Bennett Citation2019). In the same vein, consider magazine articles with titles such as ‘The Astrological Is Political: Why Alice Sparkly Kat uses postcolonial theory to read the stars’ (Retta Citation2021).

The nature of heterodox beliefs anticipates a deleterious effect on systemic legitimacy and institutional trust. Historically, heterodoxy and heresy have been the cultural basis of political dissent and anti-elitism. An undercurrent of deviant supernatural beliefs has been a feature of primitive class conflict against an oppressive social order, and a form of resistance to authority that subordinate groups have employed across history (Almond et al. Citation2003; Cohn Citation1970; Harkin Citation2004; Scott Citation1977). This type of work has dealt with the heterodox undertones of various popular radical challenges to established authority, such as the German Peasants’ War before the Reformation, the Levellers in the English Civil War and Pacific cargo cults. According to this literature, deviant supernatural doctrines and practices, such as witchcraft, slave religion and the corruption of official church doctrine into ‘folk’ religiosity are a valuable resort for underprivileged groups that wish to challenge the established culture (Scott Citation1990: 144).

With increasing modernisation and secularisation expressed as institutional differentiation in most societies, the main cause of heterodox disaffection with political authority (i.e. the oppression of heterodoxy in favour of established religion) has also been disappearing. Yet, we argue that the institution-rejecting implications of heterodox beliefs survive in the modern context. Sociologists of religion, especially those who examine new religious movements, have long emphasised the anti-authority and left-libertarian ethos that is typically attached to various unconventional supernatural beliefs in modern society (Berger et al. Citation2003; Bloch Citation1998; Harvey and Vincett Citation2012; Heelas Citation1996; Kaplan and Loow Citation2002; cf. Adorno Citation1957). Notable cases include pagan and ‘New Age’ rituals usually practised in the fringes of contemporary countercultural, anti-globalisation, environmental, feminist and other progressive movements.

Students of these phenomena note an interesting implication in the decline of conventional religious belief and the persistence or even growth of these unconventional beliefs in late modernity. The implication concerns a major societal shift, whereby supernatural belief is motivated less by the once-dominant sources of authority external to the self (i.e. ‘authority without’ that is traditional, top-down, institutionalised – for instance, the Church). In late modernity, individual interaction with postulated supernatural forces is motivated by sources of authority that are internal to the self (i.e. ‘authority within’ that is individualised, identitarian, intuitive) (Heelas Citation1996: 1–3; Houtman and Aupers Citation2007: 317).

Certainly, part of this transformation involves a parallel process of rationalisation and secularisation: the individual, at last self-autonomous and free from the bounds of tradition, can now question external authority and hierarchy (Giddens Citation1994). This is the basis of the customary, dichotomous approach to belief-focused explanations of institutional trust: unbelief, rationality and healthy scepticism of authority versus conventional religious belief and passive acceptance of authority. Yet, another part of this transformation is reflected in the rise and presence of modern heterodox beliefs. This part has been largely overlooked by political scientists.

Modern heterodox beliefs typically lack a collective ritual space and instead tend to be a ‘client’ or ‘audience’ based affair (Bruce Citation1995: 103; McGuire Citation2007). The familiar Durkheimian ideal-typical dichotomy between the sacred and the profane is relevant here (Durkheim Citation1965). According to this dichotomy, conventional religious beliefs are sacred. They are geared towards collective, public needs and experiences. In contrast, heterodox beliefs like witchcraft and astrology, but also the translation of official religion into ‘folk’ religiosity, are profane. They focus on private, everyday problems of personal concern and the pursuit of immediate and tangible benefits for the individual believer such as protection from accident, how to get rich quickly or a speedy therapy.

Expectations and hypotheses: systemic distrust and anti-science

In this sense, heterodox beliefs are inherently atomised experiences that do not have a strong collective, organised basis. Beliefs in divination, lucky charms and faith healing lack the stable group nature of the more familiar forms of organised faith (e.g. the Abrahamic religions) that helps to align adherents behind collective identities, aims and institutions. Because of their more individualistic nature, therefore, modern heterodox beliefs can alienate individuals from communal aims and the institutions that promote them. In the absence of the collectivist and system-affirming ethos of official (church) religions, this line of thinking anticipates a negative effect of unconventional beliefs on institutional trust. We therefore expect that heterodox believers differ from traditional religious believers in the following respect:

Hypothesis 1: The stronger the heterodoxy, the lower the institutional trust.

One way to consider these cognitive differences between the heterodox and non-believers is by examining their attitude to science. While all public-facing institutions included in this analysis are built around experts applying skills (priestly, scientific, juridical, economic and legislative) that impact individual lives, we focus on science as the form of expertise that is most readily recognisable by the public. We expect heterodox beliefs to induce an anti-science attitude, which, in turn, will undermine institutional trust. Here, the effect of heterodox beliefs on institutional trust is mediated by the anti-science attitude. We therefore expect that heterodox believers differ from non-believers in the following respect:

Hypothesis 2a: The stronger the heterodoxy, the stronger the anti-science attitude.

Hypothesis 2b: The stronger the heterodoxy, the stronger the anti-science attitude, and, in turn, the lower the institutional trust.

Data and variables

We use data from the cumulated Religion modules of the International Social Survey Programme to test our hypotheses about heterodoxy (ISSP Research Group Citation2019). The cumulated dataset includes comparative survey cross-sections from years 1991, 1998 and 2008 (but not the recent separate 2018 release, which covers some of the countries below). It contains a rich set of questions about respondents’ conventional and unconventional supernatural beliefs. Our analysis includes respondents from the following countries: Austria, Czechia, Denmark, France, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Latvia, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Philippines, Portugal, Russia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. Most countries participated in either one or two of the three waves available.

The 18 countries are substantially different with regard to contextual factors, such as the supply of democracy and levels of economic development. The considerable contextual variation of our sample provides an ideal pool for examining whether and in what way belief structures affect citizens’ trust in public institutions. We also note that the sample of countries used in the analysis is largely a Europe-centred one. Any conclusions may not generalise to other contexts, where the structure of belief systems is not necessarily the one theorised here, especially regarding the collective character of conventional religiosity or the more individualistic nature of heterodoxy (cf. American religious exceptionalism, Warner Citation1993; but see Davis and Robinson Citation1999).

Religious believers, heterodox believers and non-believers

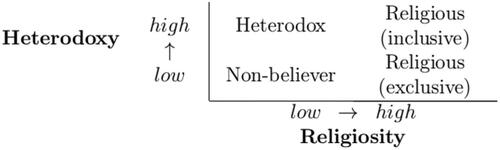

We extend the standard use of supernatural ‘belief’ variables in the study of public attitudes by treating belief as a two-dimensional concept (). On the first dimension, conventional religiosity is the familiar concept referring to the extent to which people state that they believe in an established divine power (‘God’). We square this with a second dimension, which refers to heterodoxy or the extent to which respondents accept ideas that depart explicitly from acknowledged standards and established doctrines. The second dimension distinguishes individuals based on their acceptance of these unconventional beliefs. This schema creates four initial groups: heterodox (high heterodoxy and low religiosity); non-believers (low heterodoxy and low religiosity); religious inclusive (high heterodoxy and high religiosity); and religious exclusive (low heterodoxy and high religiosity).

We use the two axes of belief structure that appear in to identify three groups: religious believers (inclusive and exclusive); non-believers; and heterodox believers. Our main analysis, therefore, collapses the two religious groups (inclusive and exclusive) into a single, generic religious group (cf. Ammerman Citation2013: 259). We will compare institutional trust for these three groups, which are fundamentally different in their understanding of natural and human affairs.

In order to gauge heterodoxy, we use respondents’ assessment of statements that appeared together as a four-item battery in the ISSP questionnaire: (a) ‘Good luck charms sometimes do bring good luck’; (b) ‘Some fortune tellers really can foresee the future’; (c) ‘Some faith healers do have God-given healing powers’ and (d) ‘A person’s star sign at birth, or horoscope, can affect the course of their future’.Footnote1 Respondents assessed each of these four items on a four-point scale, where ‘definitely true’ was scored as ‘1’ and ‘definitely false’ as ‘4’. We combine reversed answers to these four statements, and then use a threshold score to create a binary variable of heterodoxy. When a respondent generally endorsed unconventional supernaturalism (i.e. score on the reversed additive scale is higher than 8), we code this binary variable as ‘1’.

While it is possible that there is variation in aspects of heterodoxy across countries, the four items are ideal for comparative analysis. They refer to beliefs in practices that are universally recognised across cultures. They tend to be worded in an abstract way, which signals the general class rather than the specific phenomenon (e.g. fortune telling is variably understood as chiromancy, cartomancy, clairvoyance or cleromancy by different cultures). The ISSP battery is not exhaustive of the entire spectrum of heterodox beliefs in the supernatural (see a list in Tobacyk Citation2004: 96).

We measure conventional religious belief as belief in God. Respondents were asked to choose among the following options: ‘I don’t believe in God’; ‘I don’t know whether there is a God and I don’t believe there is a way to find out’; ‘I don’t believe in a personal God, but I do believe in a Higher Power of some kind’; ‘I find myself believing in God some of the time, but not at others’; ‘while I have doubts, I feel that I do believe in God’ and ‘I know God really exists and I have no doubts about it’. We code a new binary variable as ‘1’ for respondents that reported the last option; that is, that expressed a firm and unquestionable conventional religious belief. This strict operationalisation ensures the distinctiveness of ‘religious believers’ vis-à-vis the other two groups. Online Appendix B provides evidence that religious belief and heterodoxy are separate constructs.

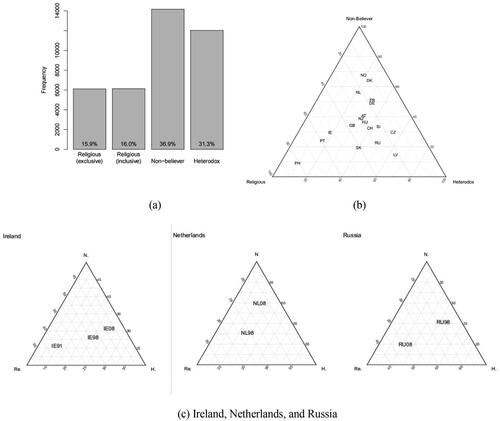

plots the overall distribution of belief types, while online Appendices C and D provide basic demographics and country-wave variation. suggests that the ISSP pool contains a substantial number of people who tend to question traditional religious beliefs but generally endorse unconventional, heterodox ones. These respondents account approximately for one third of survey participants (31%). There are slightly more non-believers (37%) in the sample, accounting for another third of participants. Among religious believers, we find an equal split between inclusive religious believers (16%) and exclusive ones (16%). Together, these two subgroups of religious believers make up the last third of participants. indicates that rather than embracing secular rationality, many people in modern societies tend to adhere to some type of unconventional belief.

The ISSP dataset includes countries with diverse socioeconomic and political backgrounds. In this respect, masks important cross-national variation in belief composition. plots the average compositions of religious, heterodox and non-believers for surveyed countries as a ternary plot (see also online Appendix D). indicates that countries disperse markedly along the three axes.Footnote2 For example, Norway (NO) has the highest share of non-believers (right axis), with fewer religious believers (left axis) than heterodox ones (bottom axis). In contrast, majorities in the Philippines (PH) and Portugal (PT) are composed of religious believers, with fewer heterodox and non-believers. Finally, formerly communist Latvia (LV) occupies the bottom right angle with the greatest amount of heterodox believers in our sample of countries.

The multiple waves of the ISSP also allow us to map changes in the distribution of belief types over time, subject to wave availability. As shown in , there are various distinctive trajectories that stand out. Ireland exemplifies a clear move away from conventional religiosity and mostly towards heterodoxy. In comparison, the Netherlands becomes unreligious more gradually over time. Russia illustrates the familiar journey towards a post-communist religious ‘revival’. The sheer cross-national variation and the dynamics of change over time suggest that the existing focus of empirical research on the political implications of conventional religiosity (or lack thereof) overlooks a large part of the underlying structure of supernatural belief systems.

Institutional trust and anti-science

We expect that supernatural belief structures affect mass attitudes towards public institutions. We are motivated by the current climate of generalised popular discontent against various sources of established authority, political, epistemic, economic and moral. Therefore, for the record, our view of institutional trust is wider than mere public confidence in political structures (e.g. legislatures). Our study deals with the major public-facing institutions that exercise authority over the individual: religious, scientific, legal, economic and political (Zelditch Citation2001).

To gauge citizens’ trust in institutions, we rely on a commonly used battery of questions from the ISSP that includes the following statements: ‘How much confidence do you have in: (a) Parliament; (b) Business and industry; (c) Churches and religious organisations; (d) Courts and the legal system; and (e) Schools and the educational system?’ For each of the five items respondents answered on a five-point scale, where ‘complete confidence’ was scored as ‘1’ and ‘no confidence at all’ as ‘5’. These items cover the key public institutions of modern society, which are the legitimate sources of civic, epistemic and moral authority to which individuals are expected to conform. Although organised across separate material and normative foundations, together they capture the realm of acceptable, systemic power.

Indeed, our analysis points that responses to these items are internally consistent (Cronbach’s α = .72; Guttman’s λ = .69). We constructed an index of general institutional trust by aggregating respondents’ answers to all five items, coded in reverse order. In the following analysis, we use this index as our main dependent variable to test whether religious believers, heterodox believers and non-believers differ in terms of expressed institutional trust. To ensure the robustness of our analysis, we also look separately at explanations of trust in specific institutions such as the national legislature and organised religion.

Hypotheses 2a and 2b expect heterodox believers to harbour a more negative attitude towards science compared to non-believers as the basis of their distrust. We operationalise anti-science by using the following two survey items: ‘Modern science does more harm than good’; ‘We trust too much in science and not enough in religious faith’. For each of the two items, respondents answered on a five-point Likert scale. We use these two items to create an additive scale, whereby higher scores indicate a stronger anti-science position.

Controls

We control for a range of individual- and country-level characteristics that are available in the ISSP’s cumulated Religion modules, particularly those highlighted in the institutional trust literature. At the individual level we include respondents’ gender, education level (degree indicator, ranging from ‘no formal education’ to ‘upper level tertiary’), and age group. We merge the individual-level data with country-level data such as GDP per capita (from the World Bank database). Many studies also stress the importance of regime type and performance (e.g. democracy vs. autocracy) in shaping people’s institutional trust. We thus use Polity IV (Gurr et al. Citation2016) to control for political context.

A state’s past experience with communist rule affects mass attitudes towards public institutions (Mishler and Rose Citation2001). For this reason, we control for communist legacy via a dichotomous variable. Another established view is that close proximity between a state and an official church produces higher levels of institutional trust in general among the population (Martin Citation1978). On this basis, we include a contextual control for the type of relationship that links the state with organised religion, which ranges from negative (state hostility towards religion) to positive (a religious state) using Fox’s ‘official support’ variable (we use the SBX variable from Fox’s Religion and State project; see also Fox Citation2008). Finally, as the ISSP dataset includes various waves of measurement, we control for wave to account for the role of historical changes (Luo and Hodges Citation2022).

Analysis and results

First, we test our main hypothesis using multilevel analysis with random slopes and random intercepts (Gelman and Hill Citation2007). Then, we test the indirect effects of heterodox beliefs via causal mediation analysis. Compared to no pooling (e.g. country-based) and traditional pooling methods, multilevel analysis is a more accurate estimation of the direct effects of both the individual and contextual correlates. It also examines how the impact of belief structure varies across national contexts. More specifically, we regress the combined index of institutional trust on belief types, and we add control variables at both individual and country levels in a stepwise manner (, models 1–4). We then disaggregate further to examine trust in two specific institutions that are emblematic of temporal and religious authority; that is, legislative bodies and formal religious bureaucracies (, models 5–6).

Table 1. Multilevel analysis of institutional trust.

reports multilevel analysis results regarding the determinants of institutional trust (Hypothesis 1). Three findings stand out. First, we observe significant differences between the religious, the heterodox and non-believers. Both non-believers and heterodox believers express less confidence in public institutions than do religious believers. This pattern persists when we focus on specific institutions such as legislative and religious bodies (models 5–6).

Second, we find that a series of important sociodemographics also shape institutional trust. Differences among religious believers, non-believers and heterodox believers persist even after controlling for these variables. Specifically, we find some significant gender, education, and age effects. For instance, respondents in their 70s or older are consistently more likely to report greater confidence in public institutions. The findings confirm existing research by emphasising the importance of exogenous socialisation and structural factors as explanations of institutional trust (e.g. Mishler and Rose Citation2001).

Third, some country-level variables also bear an association with public trust in institutions. Controlling for these contextual factors does not affect the main relationship between belief types and institutional trust. Particularly, we find that while respondents interviewed in countries with a communist past are likely to report lower trust in legislative bodies, those in more mature democracies report higher trust. Moreover, we find that in countries with stronger official support for organised religion, people are more likely to trust public institutions in general, in a relationship partly explained by the fact that official state support often coincides with more homogeneous societies.Footnote3

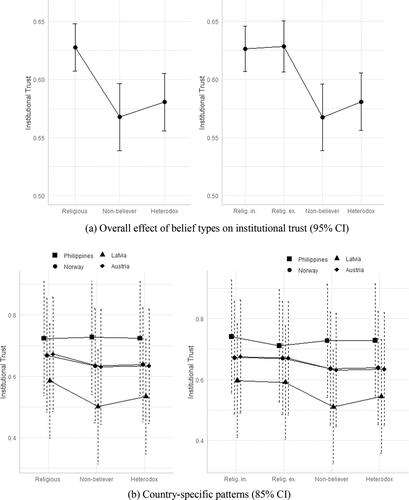

Our multilevel analysis introduces random slopes and random intercepts, as the relationship between supernatural belief structures and institutional trust may vary cross-nationally. shows the overall effect of belief types, independent of random country effects and idiosyncratic individual effects. Consistent with , we find a strong and consistent heterodoxy effect on institutional trust.

In order to provide a more granular picture under divergent country-specific contexts, focuses on four countries: Philippines, Norway, Latvia and Austria. Footnote4 The first three countries occupy the three angles of , representing three extreme compositions of belief systems. Austria lies roughly at the centre of , indicating a more balanced composition profile. While respondents in these four countries report different levels of general institutional trust, there is a similar overall pattern of ‘dips’ in most cases.

We also present the same relationship for the extended belief-type categorisation in the right panel of . We can conclude here, therefore, that there are no marked differences between inclusive and exclusive religious believers. Online Appendix F provides an additional analysis that finds no significant differences between these two subgroups of religious believers in terms of institutional trust.

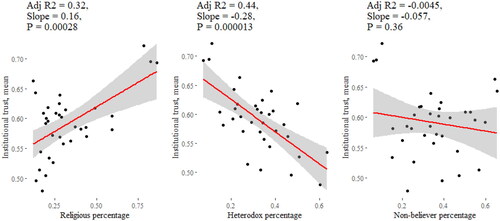

In an additional check, plots country-level percentages of each belief type and country-year means of institutional trust. These bivariate plots indicate that the extent of the religious presence and the extent of the heterodox presence in a country are strongly associated in the expected direction (positively and negatively, respectively) with institutional trust. The heterodox percentage, hitherto ignored in this field, has a stronger relationship with institutional trust (slope = −0.28). There is no significant bivariate relationship between the non-believer percentage and institutional trust at the national level. Together with our individual-level results, we interpret this as further evidence in support of our main argument.

We theorised that, while both non-believers and heterodox believers would be less likely to express confidence in public institutions (H1), they would do so from a different basis (H2a–b). One possible mechanism that can be tested with this dataset is that non-believers question authority because they are prone to use one’s own cognitive capacity to pursue truth and meaning in an analytic manner. This benign explanation of why this segment distrusts institutions is not expected to apply to heterodox believers. As we have already discussed, the scholarly literature treats the latter as prone to a less benign, more intuitive and ‘epistemically suspect’ thinking style, which departs from the idealised image of the ‘critical’ citizen.

In order to test Hypotheses 2a and 2b, we employ multilevel and mediation analysis. We first explore the connection between belief types and anti-science attitudes as stated in Hypothesis 2a. presents the results of a multilevel analysis with non-believers as the reference group. We find a consistent pattern across all models: heterodox believers are markedly more anti-science compared to non-believers. On a side note, we observe that belief in any type of supernatural agency (religious and heterodox) is related to a stronger anti-science position, which we have discussed in connection to analytic thinking (Pennycook et al. Citation2012). The difference between the religious and the heterodox is, of course, that the former express greater confidence in public institutions, which we attribute to the prosocial nature of conventional religiosity.

Table 2. Multilevel analysis of anti-science attitudes.

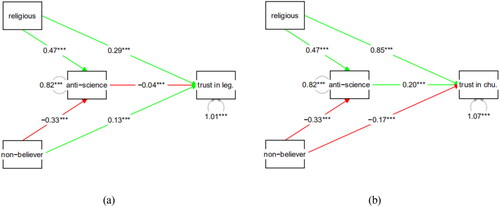

To explore further the mediating role of anti-science attitudes in institutional distrust among the heterodox and non-believers, we examine the effect of heterodox beliefs via anti-science attitudes (Hypothesis 2b). We treat heterodox believers as the reference, with results reported in (for full results and additional multilevel analyses, see online Appendix G). We find evidence of strong and significant mediating effects (for mediation analysis, see Pearl Citation1998; Pearl et al. Citation2016). reports that, compared to non-believers, the reference heterodox group is more anti-science, which, in turn, significantly undermines trust in legislative institutions. This causal chain applies only to heterodox believers. Regarding trust in religious institutions (), anti-science attitudes significantly boost trust in church institutions and, again, the reference heterodox group is more anti-science compared to non-believers. These results confirm our hypothesis that the relationship of heterodoxy with institutional trust is mediated by anti-science attitudes. Together with the findings from , we conclude that although both heterodox believers and non-believers tend to distrust public institutions, the former do so for reasons unrelated to the ‘healthy’ (pro-science) scepticism exercised by non-believers, who are the prototypical ‘critical’ rational citizens.

Conclusion and discussion

Supernatural-oriented beliefs and institutional trust are indeed related, but not for the widely assumed reason that has driven political science research. The ongoing decline of institutional trust experienced by most mature democracies is not simply due to the presence of a less religious, more informed, rational citizenry. It is partly due to the hitherto ignored presence of citizens who are not particularly religious but are prone to ‘epistemically suspect’ beliefs. This empirical analysis provided evidence that heterodox beliefs in the supernatural, exemplified in the conviction that astrology, faith healing, fortune telling and lucky charms actually work, were associated with the tendency to distrust public institutions (parliaments, courts, businesses, organised religion and the education system). The statistical analysis used comparative individual-level information from the cumulated ISSP Religion modules, supplemented by contextual variables.

We acknowledge that the considerable cross-country variation in the distribution of belief types invites further exploration by students of political trust; ideally with evidence that covers consistently an adequate number of countries for an adequately long period. Survey design issues also did not allow us to explore potential confounders surrounding the heterodoxy-political distrust relationship; most notably, other kinds of non-mainstream experience and belief (e.g. the role of minority status; see De Vroome et al. Citation2013).

These limitations notwithstanding, we interpret the overall finding as follows: we are not witnessing a linear trend towards a more rational future that will translate into positive inputs for representative democratic government. This is not a story solely of ‘critical’ citizens that are sceptical of institutional structures, while still engaging constructively with these structures in a benign effort to improve them. If the liberal democratic ideal requires these ‘critical’ citizens, then the presence of distrustful and anti-science heterodox believers is a cause for concern (cf. Bertsou Citation2019). Heterodoxy, after all, appears to coincide with phenomena that include conspiracist ideation and news diets that promote disinformation (Van Prooijen et al. Citation2022: 1069, 1073; Ward and Voas Citation2011). These phenomena rest on non-analytic thinking modes and are facilitated and networked by the same media landscape. Combined, they may form a less constructive pressure on levels of institutional trust in advanced, supposedly rational societies.

The present analysis adds a twist to the popular lament of the current and the previous two centuries regarding the ‘naked public square’ (see a recent iteration in Dreher Citation2019). According to this lament, advancing secularisation of the type afflicting the ‘Judeo-Christian tradition’ as the cultural foundation of the Western institutional order will prove detrimental to systemic legitimacy, political stability and established authority. Our study implies that if this happens, it will not be merely due to modern societies abandoning organised religion in favour of healthy independent scepticism towards authority structures. It might also happen because the same modern context provides a fertile ground for the diffusion of a more problematic type of belief system – heterodoxy.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (766.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Stratos Patrikios

Stratos Patrikios is a senior lecturer at the School of Government and Public Policy, University of Strathclyde. His research focuses on religion and politics. He has published in journals such as Electoral Studies, Journal of Peace Research, Political Behaviour and Socio-Economic Review. [[email protected]]

Narisong Huhe

Narisong Huhe is a senior lecturer at the School of Government and Public Policy, University of Strathclyde. His research focuses on political attitudes and public opinion. He has published in journals such as British Journal of Political Science, Journal of European Public Policy, Political Research Quarterly and Social Networks. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 The presence of the faith-healing item, which refers to ‘God’, might be considered problematic by being too close to conventional religion (cf. McCleary and Barro Citation2006). Yet, translations of the questionnaire in the various ISSP-participating languages make an explicit connection between the faith-healing item and unconventional beliefs. For example, the Portuguese version uses the term ‘curandeiro’ for faith healer, which refers to quack or witchdoctor. The French version uses the term ‘guérisseur’, which also has unconventional connotations. We tested our models by excluding this item, and found results that were consistent with those reported in the main text (see online Appendix A).

2 We ‘jiggered’ some overlapping points for better readability. Exact distribution statistics appear in the online Appendices.

3 Online Appendix E provides an alternative model specification with separate, continuous versions of religiosity and heterodoxy.

4 For , while we varied countries from Philippines to Austria, we fixed Sex as ‘Female’, Education as ‘3’, Age group as ‘70 and older’, Survey wave as ‘1991’, GDPpc as ‘28713.75’, Democracy as ‘10’, Post-Communism as ‘0’ and Official Support as ‘6’. Further details appear in the replication files in the online Appendix.

References

- Adorno, Theodor W. (1957). ‘The Stars down to Earth’, Jahrbuch für Amerikastudien, 2, 19–88.

- Almond, Gabriel, R. Scott Appleby, and Emmanuel Sivan (2003). Strong Religion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Ammerman, Nancy T. (2013). ‘Spiritual but Not Religious? Beyond Binary Choices in the Study of Religion’, Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 52:2, 258–78.

- Barber, Bernard (1983). The Logic and Limits of Trust. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

- Bennett, Jessica (2019). ‘When Did Everybody Become a Witch?’, New York Times, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/24/books/peak-witch.html (accessed 1 September 2022).

- Berger, Helen A., Evan A. Leach, and Leigh S. Shaffer (2003). Voices from the Pagan Census. Columbia: University of South Carolina.

- Bertsou, Eri (2019). ‘Rethinking Political Distrust’, European Political Science Review, 11:2, 213–30.

- Billings, Dwight B., and Shaunna L. Scott (1994). ‘Religion and Political Legitimation’, Annual Review of Sociology, 20:1, 173–202.

- Bloch, Jon P. (1998). ‘Alternative Spirituality and Environmentalism’, Review of Religious Research, 40:1, 55–73.

- Bruce, Steve (1995). Religion in Modern Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Campbell, David E., Geoffrey C. Layman, and John C. Green (2021). Secular Surge: A New Fault Line in American Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Citrin, Jack (1974). ‘The Political Relevance of Trust in Government’, American Political Science Review, 68:3, 973–88.

- Cohn, Norman (1970). The Pursuit of the Millennium: Revolutionary Millenarians and Mystical Anarchists of the Middle Ages. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Coleman, John A. (1970). ‘Civil Religion’, Sociological Analysis, 31:2, 67–77.

- Dalton, Russell J. (2004). Democratic Challenges, Democratic Choices. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dalton, Russell J., and Christian Welzel (2014). The Civic Culture Transformed: From Allegiant to Assertive Citizens. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Davis, Nancy J., and Robert V. Robinson (1999). ‘Their Brothers’ Keepers? Orthodox Religionists, Modernists, and Economic Justice in Europe’, American Journal of Sociology, 104:6, 1631–65.

- Dawkins, Richard (2006). The God Delusion. London: Bantam Press.

- De Vroome, Thomas, Marc Hooghe, and Sofie Marien (2013). ‘The Origins of Generalized and Political Trust among Immigrant Minorities and the Majority Population in The Netherlands’, European Sociological Review, 29:6, 1336–50.

- Dreher, Rod (2019). ‘Politics in a Culture of Disintegration’, American Conservative, available at www.theamericanconservative.com/dreher/politics-culture-disintegration-benedict-option/ (accessed 1 September 2022).

- Durkheim, Émile [1915] (1965). The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life. New York: Free Press.

- Engels, Friedrich [1892] (1935). Socialism: Utopian and Scientific. New York: International Publishers.

- Foa, Roberto S., and Yascha Mounk (2016). ‘The Danger of Deconsolidation: The Democratic Disconnect’, Journal of Democracy, 27:3, 5–17.

- Fox, Jonathan (2008). A World Survey of Religion and the State. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Fuller, Robert C. (2001). Spiritual but Not Religious: Understanding Unchurched America. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gelman, Andrew, and Jennifer Hill (2007). Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Giddens, Anthony (1994). Beyond Left and Right: The Future of Radical Politics. Stanford: Stanford University.

- Goetz, Klaus H., and Dorte Sindbjerg Martinsen (2021). ‘COVID-19: A Dual Challenge to European Liberal Democracy’, West European Politics, 44:5-6, 1003–24.

- Graham, Jesse, and Jonathan Haidt (2010). ‘Beyond Beliefs: Religions Bind Individuals into Moral Communities’, Personality and Social Psychology Review, 14:1, 140–50.

- Gurr, Ted R., Monty G. Marshall, and Keith Jaggers (2016). Polity IV: Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions, 1800–2015. Fairfax: George Mason University.

- Harkin, Michael E., ed. (2004). Reassessing Revitalization Movements: Perspectives from North America and the Pacific Islands. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Harvey, Graham, and Giselle Vincett (2012). ‘Alternative Spiritualities’, in Linda Woodhead and Rebecca Catto (eds.), Religion and Change in Modern Britain. London: Routledge, 156–72.

- Heelas, Paul (1996). The New Age Movement. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Hetherington, Mark J. (1998). ‘The Political Relevance of Political Trust’, American Political Science Review, 92:4, 791–808.

- Houtman, Dick, and Stef Aupers (2007). ‘The Spiritual Turn and the Decline of Tradition: The Spread of Post-Christian Spirituality in 14 Western Countries, 1981–2000’, Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 46:3, 305–20.

- Inglehart, Ronald (1997). Modernization and Post-Modernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Inglehart, Ronald (1999). ‘Postmodernization Erodes Respect for Authority, but Increases Support for Democracy’, in Pippa Norris (ed.), Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Government. New York: Oxford University Press, 236–56.

- ISSP Research Group (2019). International Social Survey Programme: Religion I-III – ISSP 1991-1998-2008. GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA5070 Data file Version 1.1.0, Retrieved from

- Kahneman, Daniel (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

- Kaplan, Jeffrey, and Helene Loow (2002). The Cultic Milieu: Oppositional Subcultures in an Age of Globalization. Walnut Creek: Alta Mira Press.

- Lambert, Yves (2006). ‘Trends in Religious Feeling in Europe and Russia’, Revue Française de Sociologie, 47, 99–129.

- Layman, Geoffrey C., David E. Campbell, John C. Green, and Nathanael Gratias Sumaktoyo (2021). ‘Secularism and American Political Behavior’, Public Opinion Quarterly, 85:1, 79–100.

- Levi, Margaret, and Laura Stoker (2000). ‘Political Trust and Trustworthiness’, Annual Review of Political Science, 3:1, 475–507.

- Luo, Liying, and James S. Hodges (2022). ‘The Age-Period-Cohort-Interaction Model for Describing and Investigating Inter-Cohort Deviations and Intra-Cohort Life-Course Dynamics’, Sociological Methods & Research, 51:3, 1164–210.

- Marien, Sofie, and Marc Hooghe (2011). ‘Does Political Trust Matter? An Empirical Investigation into the Relation between Political Trust and Support for Law Compliance’, European Journal of Political Research, 50:2, 267–91.

- Martin, David (1978). A General Theory of Secularization. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Marx, Karl [1843/1844] (1975). ‘A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right: Introduction’, in Lucio Colletti (ed.), Karl Marx: Early Writings. London: Penguin, 243–58.

- McCleary, Rachel M., and Robert J. Barro (2006). ‘Religion and Political Economy in an International Panel’, Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 45:2, 149–75.

- McGuire, Meredith (2007). ‘Embodied Practices’, in Nancy T. Ammerman (ed.), Everyday Religion: Observing Modern Religious Lives. New York: Oxford University Press, 187–200.

- Miller, Arthur H. (1974). ‘Political Issues and Trust in Government: 1964–1970’, American Political Science Review, 68:3, 951–72.

- Mishler, William, and Richard Rose (2001). ‘What Are the Origins of Political Trust? Testing Institutional and Cultural Theories in Post-Communist Societies’, Comparative Political Studies, 34:1, 30–62.

- Norbeck, Edward (1961). Religion in Primitive Society. New York: Harper & Brothers.

- Norris, Pippa, ed. (1999). Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Government. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart (2004). Sacred and Secular: Religion and Politics Worldwide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart (2019). Cultural Backlash. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Pearl, Judea (1998). ‘Graphs, Causality, and Structural Equation Models’, Sociological Methods & Research, 27:2, 226–84.

- Pearl, Judea, Madelyn Glymour, and Nicholas P. Jewell (2016). Causal Inference in Statistics: A Primer. West Sussex: Wiley.

- Pennycook, Gordon, James Allan Cheyne, Paul Seli, Derek J. Koehler, and Jonathan A. Fugelsang (2012). ‘Analytic Cognitive Style Predicts Religious and Paranormal Belief’, Cognition, 123:3, 335–46.

- Pennycook, Gordon, Jonathan A. Fugelsang, and Derek J. Koehler (2015). ‘Everyday Consequences of Analytic Thinking’, Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24:6, 425–32.

- Retta, Mary (2021). ‘The Astrological Is Political: Why Alice Sparkly Kat Uses Postcolonial Theory to Read the Stars’, The Nation, available at www.thenation.com/article/culture/alice-sparkly (accessed 1 September 2022).

- Ruck, Damian J., Luke J. Matthews, Thanos Kyritsis, Quentin D. Atkinson, and R. Alexander Bentley (2020). ‘The Cultural Foundations of Modern Democracies’, Nature Human Behaviour, 4:3, 265–9.

- Rutjens, Bastiaan T., and Romy van der Lee (2020). ‘Spiritual Skepticism? Heterogeneous Science Skepticism in The Netherlands’, Public Understanding of Science, 29:3, 335–52.

- Saroglou, Vassilis, Vanessa Delpierre, and Rebecca Dernelle (2004). ‘Values and Religiosity: A Meta-Analysis of Studies Using Schwartz’s Model’, Personality and Individual Differences, 37:4, 721–34.

- Scott, James C. (1977). ‘Protest and Profanation: Agrarian Revolt and the Little Tradition, Part I’, Theory and Society, 4:1, 1–38.

- Scott, James C. (1990). Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Tobacyk, Jerome J. (2004). ‘A Revised Paranormal Belief Scale’, International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 23:1, 94–8.

- Van Prooijen, Jan-Willem, Talia Cohen Rodrigues, Carlotta Bunzel, Oana Georgescu, Dániel Komáromy, and André P. M. Krouwel (2022). ‘Populist Gullibility: Conspiracy Theories, News Credibility, Bullshit Receptivity, and Paranormal Belief’, Political Psychology, 43:6, 1061–79.

- Verba, Sidney, Kay L. Schlozman, and Henry E. Brady (1995). Voice and Equality. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Voas, David (2009). ‘The Rise and Fall of Fuzzy Fidelity in Europe’, European Sociological Review, 25:2, 155–68.

- Ward, Charlotte, and David Voas (2011). ‘The Emergence of Conspirituality’, Journal of Contemporary Religion, 26:1, 103–21.

- Warner, R. Stephen (1993). ‘Work in Progress Toward a New Paradigm for the Sociological Study of Religion in the United States’, American Journal of Sociology, 98:5, 1044–93.

- Warren, Mark E., ed. (1999). Democracy and Trust. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Welzel, Christian (2013). Freedom Rising, Human Empowerment and the Quest for Emancipation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wilkins-Laflamme, Sarah (2021). ‘A Tale of Decline or Change? Working toward a Complementary Understanding of Secular Transition and Individual Spiritualization Theories’, Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 60:3, 516–39.

- Willard, Aiyana K., and Ara Norenzayan (2017). ‘“Spiritual but Not Religious”: Cognition, Schizotypy, and Conversion in Alternative Beliefs’, Cognition, 165, 137–46.

- Zelditch, Morris (2001). ‘Theories of Legitimacy’, in John T. Jost and Brenda Major (eds.), The Psychology of Legitimacy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 33–53.