Abstract

Differentiated integration (DI) and flexibility in implementation (FI) are two forms of differentiation that can be used to cope with heterogeneity among EU member states. Given the different ways in which they do so, this article asks whether DI and FI are alternatives for each other or whether they serve different functions in EU legislation. Based on a dataset that maps the occurrence of opt-outs and flexibility provisions in EU directives, the analysis shows that DI and FI tend to be used together. A qualitative analysis of directives that combine different levels of DI and FI shows that, within that overall pattern, DI is used to accommodate individual outliers, while FI is used to address widespread concerns among member states. This suggests that DI and FI are two forms of differentiation in the EU, which are used to address different aspects of a common underlying set of concerns.

Over the past decades, various forms of differentiation have been proposed in response to the (growing) heterogeneity among member states in the European Union (EU). Differentiation is seen as a way to increase both the efficiency and the legitimacy of EU decision-making in the face of the challenges raised by the increasing (and increasingly diverse) membership of the EU (Andersen and Sitter Citation2006; Dyson and Sepos Citation2010). Forms of differentiation have come under different labels, such as ‘variable geometry’, ‘multi-speed Europe’ and ‘enhanced cooperation’, with partly different implications (Stubb Citation1996). Examples include the Euro and the Schengen regimes, in which only part of the member states participate, and opt-outs for individual member states in specific directives or regulations. Under the enhanced cooperation procedure, groups of member states are allowed to adopt legislation that only applies to themselves, as is for instance the case for the regulation on cross-border divorces. Collectively, these approaches are known as ‘differentiated integration’ (DI) (Dyson and Sepos Citation2010; Leuffen et al. Citation2013; Schimmelfennig and Winzen Citation2020). What they have in common, is that they make a distinction between member states that do and member states that do not fall under some EU arrangement or measure.

In terms of background and purpose, DI is foremost seen as a way to cope with heterogeneity among member states. This heterogeneity can manifest itself during decision-making, when a divergence of preferences makes it difficult to arrive at joint solutions. Allowing for differentiation may then be a way to appease member states that do not want to be tied to EU-level measures. This leads to what Schimmelfennig and Winzen (Citation2014) call ‘constitutional differentiation’, which ‘is motivated by concerns about national sovereignty and identity’ (Ibid: 355). In addition, they discern forms of ‘instrumental differentiation’. These are related to enlargement of the EU and meant either to protect old member states from competition by new ones or to allow new member states more time to adjust to EU requirements. Whereas constitutional differentiation is often permanent (or at least adopted for an indeterminate period of time), instrumental differentiation is typically transitional.

Alongside these forms of DI, differentiation also occurs in the implementation (transposition and practical application) of EU legislation by member states. To the extent that EU law allows member states to make choices during implementation, this is another way to differentiate between member states. We call this approach flexibility in implementation (FI), as it entails that EU law offers flexibility to member states during implementation. When member states make use of this flexibility, it results in actual patterns of ‘differentiated implementation’ (see the introduction to this special issue and Princen Citation2022). Flexibility in implementation has always been part of the EU legal and political systems. Directives, in particular, are instruments that are meant to ‘leave to the national authorities the choice of form and methods’, to quote Article 288 TFEU, although the extent of this leeway depends on the content and wording of the directive. The flexibility offered by directives can take different forms, such as the possibility to adopt more stringent standards (minimum harmonisation), the possibility to restrict or expand the scope of a directive (‘scope discretion’) or room to specify more general requirements from a directive (‘elaboration discretion’) (see Van den Brink Citation2017 for this typology).

FI arguably serves many of the same purposes as DI. By giving member states discretion during implementation, differences between member states can be taken into account (Hartmann Citation2016; Thomann Citation2015; Zhelyazkova and Thomann Citation2022). Moreover, giving this flexibility may facilitate decision-making on EU-level measures when member states cannot agree on one set of uniform standards (Andersen and Sitter Citation2006: 321). As a result, both DI and FI allow for ways to tailor EU law and policies more closely to member state preferences. In the end, this should improve the ‘fit’ of EU law and policies with member state preferences and practices.

Although they serve similar purposes, DI and FI work differently. Whereas under DI certain specifically designated member states are legally exempted or excluded from (part of) an EU-level arrangement altogether, under FI all member states are given room to manoeuvre under a common legal arrangement. It is therefore important to understand better how DI and FI relate to each other. Are they (full) alternatives that substitute for each other in coping with heterogeneity in the EU or do they serve different functions within a broader range of arrangements that allow for differentiation? This question is important for advancing both academic and political debates. The academic literature on differentiation in the EU has focussed almost exclusively on DI as a way to differentiate between member states. Exploring the relationship between DI and FI enables us to explore whether the logics underlying the use of DI and FI are similar. To the extent that they are, such a comparison may reveal common institutional and political dynamics that have hitherto not been analysed systematically, and serve to broaden the notion of ‘differentiation’ in the EU. In political debates on the future of the EU, proposals for and debates about differentiation have been recurring elements (see, e.g. European Commission Citation2017: 20–21; European Council Citation2014: 11). Like the academic debate, this political debate has been limited to forms of DI as a way to achieve differentiation. Identifying the extent to which FI can be used as an alternative or complement to DI and revealing the rationales behind these two forms of differentiation may broaden the range of options available in this debate. This article therefore sets out to study the relationship between DI and FI by analysing whether DI and FI go together in EU directives and in what situations they are used.

It does so by a quantitative comparison of the use of both forms of differentiation in EU directives between 2006 and 2015 and by a qualitative examination of the rationale behind their use in a number of directives that combine different levels of DI and FI. The analysis relies on a combined dataset that links the updated EUDIFF2 dataset on DI in EU secondary legislation and the Flexible Implementation in the EU (FIEU) dataset.

We find overall support for our expectation that both DI and FI address heterogeneity among EU member states and the legislative complications that derive from it. The quantitative analysis shows that DI and FI are positively correlated. DI and FI tend to go together in EU legislation rather than being mutually exclusive instruments. To some extent, however, they also address different concerns. Our qualitative analysis of groups of directives representing distinct combinations of DI and FI reveals that DI typically exempts individual member states in a particular situation (such as geography or treaty-based opt-outs) and reflects high levels of conflict in the legislative process. Flexibility provisions are used to address heterogeneity concerns that are spread more widely among EU member states. By contrast, our expectation that DI is used to accommodate heterogeneity of preferences about the level and scope of integration, while FI is primarily used to accommodate implementation problems, receives mixed support and requires further nuance.

Theoretical expectations

As was outlined above, DI and FI achieve differentiation among EU member states in different ways. Whereas DI excludes certain member states from an EU-level legal norm, FI offers flexibility to all member states in implementing an EU-level legal norm. Building on this distinction, DI can be defined as an arrangement under which an EU-level legal norm (or set of norms) does not apply (equally) to all member states (cf. the definitions in Dyson and Sepos Citation2010: 4 and Leuffen et al. Citation2013: 17). This means that specific and individually identifiable member states are excluded from some EU-level legal arrangement. Examples are the (specific) member states that have not adopted the Euro or the member states that do not participate in the regulation on cross-border divorces. Likewise, if an individual member state obtains an opt-out from a specific provision in a directive, this is a form of DI.

FI is an arrangement under which member states are given flexibility in implementing some EU-level legal instrument or legal norm (cf. Zbiral et al. Citation2022). The key difference with DI is, first, that FI does not apply to a specific member state but to all member states. In addition, whereas under DI an opt-out itself produces variation between member states, FI only introduces the opportunity for member states to adopt different domestic arrangements and standards. Actual differences between member states therefore depend on the use they make of the flexibility that is offered to them.

In order to avoid overlap between these two categories, we reserve the label ‘DI’ to what in the literature is known as ‘actual’ differentiation. Actual differentiation refers to individual member states, as in Denmark and Ireland’s exemptions from legislation adopted in the area of Justice and Home Affairs. In addition, EU legislation sometimes includes what the literature has called ‘potential’ differentiation. Potential differentiation typically accords all member states the right to seek or declare formal exemptions from specific legal obligations under certain conditions (Tuytschaever Citation1999). In our conceptual approach, potential differentiation is a form of FI, since it allows all member states to make further decisions during the implementation process.

Since we are interested in the way DI and FI are used in EU directives, we only look at instances in which they are formally granted to member states. In addition, the literature has also identified ‘de facto’ differentiation, in which member states informally opt out of EU legislation by refusing or failing to implement (some part of) it (Hofelich Citation2022). Although such forms of de facto differentiation are sometimes tolerated when they arise, they are normally not used as ways to deal with heterogeneity between member states at the time of adoption of an EU-level legal framework. For the same reason, we do not look at instances in which member states have a formal opt-out but decide to cooperate with other member states nonetheless (cf. Migliorati’s (Citation2022) analysis of the de facto cooperation between Denmark and the rest of the EU in the field of Justice and Home Affairs).

Based on these definitions, we can develop a number of theoretical expectations on the relationship between DI and FI in EU legislation. These expectations derive from the observation that DI and FI serve similar purposes. Both are ways to accommodate heterogeneity among member states and to prevent heterogeneity from causing paralysis in decision-making and implementation. In relation to this, two points about heterogeneity are important to note. First, the sources of heterogeneity are manifold (Schimmelfennig and Winzen Citation2020: 24–30). Heterogeneity can result from differences between member states in structural conditions ‘on the ground’, which affect to what extent states are affected by international policy externalities and which standards and approaches fit their situation. Heterogeneity can also have its origins in different policy paradigms and styles as well as different attitudes towards integration. Whereas some member states (or member state governments) support a comprehensive policy scope of European integration and deep supranational centralisation, others seek to keep the EU out of certain policy domains (mainly in the area of core state powers; Genschel and Jachtenfuchs Citation2014) and/or under intergovernmental control. In addition, heterogeneity may have to do with member state capacities. Ambitious regulation, e.g. in environmental and social policy, or strict fiscal and financial rules imply costs and burdens that certain (especially poorer) member states reject. These heterogeneities translate into controversiality during decision-making and can lead to political stalemates, in which no agreement can be reached between (groups of) member states that prefer different outcomes. The literature shows that, in such circumstances, both DI and FI are means to achieve compromise by differentiating between member states and accommodating ‘outliers’ (for DI, see Bellamy and Kröger Citation2017; Holzinger and Schimmelfennig Citation2012; Jensen and Slapin Citation2012; Lord Citation2015; for similar arguments about FI, see Andersen and Sitter Citation2006: 321; Dimitrova and Steunenberg Citation2000: 218; Hartmann Citation2016; Thomann Citation2015; Zhelyazkova and Thomann Citation2022).

The second key point is that heterogeneity may follow different spatial patterns. Whereas some cases of heterogeneity pit one or a few ‘outlier’ member states against the rest, other cases lead to several groups of member states that exemplify different ‘types’ (of, say, legal approaches, sociocultural values or natural conditions). Still other cases lead to a pattern in which all member states more or less differ from each other. A specific case may also exhibit a combination of these patterns, with one or a few member states having strong objections against a proposed piece of legislation while the others, which are in principle positive about the proposal, want to accommodate smaller differences between them.

Given the different sources and spatial patterns of heterogeneity, we can formulate a number of theoretical expectations on the relationship between DI and FI. In terms of their overall use, if DI and FI respond to the same underlying condition (heterogeneity), there are two possible types of overall relationship between them. The first possibility is that DI and FI are complementary responses to different sources and patterns of heterogeneity under the same piece of EU legislation. If so, we should observe a positive correlation between the occurrence of DI and FI in directives: if one form of differentiation is more prevalent in a directive, the other should also be. The second possibility is that DI and FI are rival responses to the same sources and patterns of heterogeneity. In that case, the choice is between DI or FI, and a greater use of one should go together with a lesser use of the other. This would then lead to a negative correlation between the two.

The first possibility is arguably the most plausible. Although in some cases one or a few member states may have specific objections against a legislative proposal while the other member states all support a large degree of uniformity, it is more likely that a proposal that gives rise to fundamental objections on the part of some member states will also lead to reservations (albeit less pronounced) on the part of member states that in principle agree to a common EU approach. In addition, member states that consent to opt-outs for one or a few of their peers may want to reserve a degree of discretion for themselves, too. This mix can be addressed through a combination of opt-outs and flexibility provisions. We therefore formulate the following hypothesis:

H1: The use of DI and FI in EU directives is positively associated.

This is much less the case for FI, as member states are still part of the same EU-level arrangement and the flexibility offered by FI provisions is often much less visible. FI is therefore less likely to address identity and sovereignty concerns to the extent that DI does. For that reason, we may expect FI to be used primarily in relation to specific implementation problems, which derive from capacity deficits and high costs. EU law imposes varying adjustment costs on the member states, and member states have varying administrative and financial capacity to bear these adjustment costs. The higher the costs, and the lower their capacity, the more likely states are to seek flexibility in implementation – even if they do not disagree with the policy in principle. This leads to our second hypothesis:

H2: DI is primarily used to accommodate heterogeneity of preferences about the level and scope of integration, while FI is primarily used to accommodate implementation problems.

H3: DI is used to accommodate individual outliers, while FI is used to address widespread concerns.

Methods and data

The analysis in this article is based on a mixed-methods approach that combines the strengths of quantitative and qualitative analysis. In the quantitative analysis, the correlation between the occurrences of DI and FI in EU directives is determined. This provides a test of H1, by establishing what relationship, if any, exists between the use of these types of differentiation. The quantitative analysis is used as a basis for the selection of cases in the qualitative part of the analysis, which compares types of differentiation and their rationales in directives that exhibit different combinations of high and low DI and FI. These case studies provide additional insights into the rationales for using different forms of differentiation in EU directives and are thereby used to test H2 and H3.

The quantitative analysis is based on a dataset that codes for the occurrence of DI (opt-outs) and FI (flexibility provisions) in EU directives. DI was coded in the Differentiated Integration in the EU dataset (EUDIFF2, Duttle et al. Citation2017), FI in the Flexible Implementation in the EU dataset (FIEU, Princen et al. Citation2019; Zbiral et al. Citation2022). After merging the two datasets, the ‘master’ dataset contains values for 164 directives adopted between 2006 and 2015. The selection of directives followed the selection made for the EUDIFF2 dataset and included legislative acts (directives) as defined by primary law, excluding those that ‘merely amend, supplement, extend or suspend existing legislative acts or fix volumes, levies, duties, subsidies, refunds or prices […] on a regular (usually annual) basis’ and implementing or delegated acts (Art. 290 and 291 TFEU) (Duttle et al. Citation2017). So-called codified directives were excluded as well, because they only technically combine the original act and its amendments (vertical consolidation) or several acts from related subjects (horizontal codification). By contrast, the dataset includes recast directives which not only codify existing legislation, but also involve substantive amendments to the original legal acts. Hence, the dataset includes all new and recast directives adopted between 2006 and 2015.

To measure differentiated integration, we coded all provisions in a directive that exempt a country from applying that provision. This approach builds upon the DI measure by Duttle et al. (Citation2017), who measured DI as a count of explicit mentions of DI for a country in a legal act. However, to capture the nuances of DI and to make it comparable to the measurement of FI, which is measured on the provision level, we recoded DI on the provision level. As a result, each provision/member state combination counts as one opt-out. The overall DI variable is the sum of these opt-outs.Footnote1

FI is measured by coding provisions that provide discretion to member states (cf. the approach taken by Franchino Citation2001, Citation2004, Citation2007; see also Gastinger and Heldt Citation2022; Hartmann Citation2016; Steunenberg and Toshkov Citation2009). It does so by coding whether individual provisions granted discretion. A provision was only coded if it explicitly granted discretion. A provision includes discretion when it explicitly authorises member states to make choices in transposing, applying and enforcing EU law.

In addition to discretion as such, the dataset also distinguishes between different types of discretion. Conceptually, the types of discretion that are discerned are a combination of the typologies used by Hartmann (Citation2016) in her coding of EU directives and Van den Brink (Citation2017) in his analysis of discretion in EU law.

Based on these two typologies, the FIEU dataset includes five types of discretion:

Elaboration discretion: permission for member states to further specify a provision.

Reference to national legal norms: the use of pre-existing national legal norms for the definition of concepts or the scope of a directive.

Minimum harmonisation: permission for member states to adopt more stringent standards.

Scope discretion: permission for member states to expand or restrict the categories of cases to which a provision applies.

Discretion in application on case-by-case basis: permission for member states to deviate from a provision in an individual case.

Discretion may be limited by imposing certain constraints on the exercise of discretion, for instance by requiring prior authorisation, by attaching substantive conditions or by imposing a reporting requirement. Since these constraints affect the actual discretion given to member states, they were also coded, insofar as they were linked to a flexibility provision.Footnote2

In total, the 164 directives contained 13,806 substantive provisions. Two trained coders manually coded each directive independently of each other. Differences in coding were resolved by a supervisor in order to achieve maximal uniformity in coding. Further details on the codebooks and coding procedures can be found in the online depositories for the EUDIFF2 and FIEU datasets.Footnote3

For the quantitative analysis of the association between DI and FI, we calculated indexes for both. The DI index was obtained by dividing the total number of opt-outs in a directive by both the total number of provisions in that directive and the total number of member states at the time of adoption of the directive, and multiplying the result by 100. This leads to a number that can theoretically vary between 0 and 100. A score of 0 means that no member state has obtained any opt-out in the directive. A score of 100 means that all member states have opt-outs for all provisions. This would of course be an absurdity but it represents the theoretical extreme of complete DI.

The FI index was obtained by first weighting the number of flexibility provisions in a directive against the associated constraints, then dividing the weighted number by the total number of provisions in a directive, and multiplying the result by 100.Footnote4 Since constraints reduce the discretion member states have, we discounted the number of constraints against the number of provisions granting discretion. For each constraint, 0.5 was subtracted from the number of flexibility provisions. The use of a 0.5 weight is arbitrary in the sense that constraints have different impacts on discretion and this impact is difficult to quantify. However, as a proxy, a 0.5 weight is arguably reasonable overall. In the end, the precise weight that is used does not have a strong effect on the results, as the weighted and unweighted discretion indexes show a correlation of .971. A score on the index of 0 means a directive contains no discretion for member states whatsoever. A score of 100 means every provision in a directive provides discretion for member states.

The dataset also served as the basis for identifying cases for the qualitative examination of the use of DI and FI in directives, which explores directives on the four ‘extremes’ of the spectrum (high DI-high FI; high DI-low FI; low DI-high FI; and low DI-low FI). In the qualitative analysis, we looked at the content of these directives, in order to find out what types of DI and FI were used and why. Our dataset does not include data on the preferences of individual member states. Existing datasets on EU decision-making that include this type of data, most notably the DEU III dataset, do not include directives that occur in our qualitative examination (Arregui and Perarnaud Citation2022). Our analysis of (groups of) directives therefore relies on an inspection of the opt-outs and flexibility provisions in the directives themselves, combined with data on the decision-making process leading up to their adoption. This allows us to determine whether directives with a specific combination of DI and FI stand out in terms of their structure (e.g. length) and decision-making process (in particular, the level of conflict).

Patterns of DI and FI in directives: a quantitative analysis

Based on the dataset and the DI and FI indexes, the relationship between DI and FI can be systematically assessed. Looking at the overall figures, DI occurred much less frequently in the sample than FI. Only 35 directives contained at least one provision granting an opt-out to a member state, meaning that almost 80 percent of directives did not contain any DI provision. Within the subsample of directives with opt-outs, the number of opt-outs varied widely, with a maximum of 513 opt-outs for the highest-scoring directive.Footnote5 The DI index ranged from 0 to 17.9, with a mean of 1.2.

FI occurred more frequently in our dataset. Of the 164 directives, 162 contained at least one flexibility provision. The largest number of flexibility provisions in one directive was 217 (but in a directive with 569 provisions).Footnote6 The weighted discretion index ranged from 0 to 67.1, with a mean of 21.3.

Zooming in on the types of discretion, elaboration discretion represents the most frequent type (about 40 percent), followed by reference to national law provisions (about 25 percent). The remaining types are represented similarly with a share above 10 percent (see ).

Table 1. Overview of types of discretion.

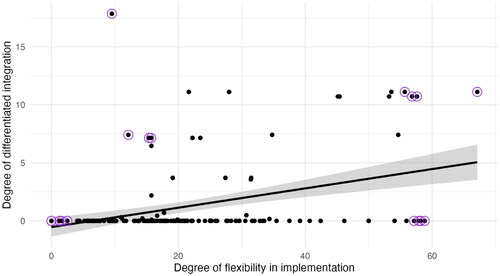

shows the scatter plot for the 164 directives in relation to the DI and FI indexes. The Pearson’s correlation between the DI and FI indexes is .380 (significant at .01 level). This is despite the outlier in the top-left corner, which combines high DI and low FI. As a robustness check, to see if the results were not driven by the directives without any opt-outs, we also calculated the correlation between the DI and FI indexes including only directives with at least one opt-out. In this subsample, the correlation is .495 (also significant at .01 level). Although the number of cases in this subsample is too small to accord it independent meaning, it confirms the main finding that DI and FI are associated.

Figure 1. Scatterplot of the DI and FI indexes with the regression line and the cases included in the qualitative analysis highlighted. Shaded area indicates the 95% confidence interval.

also includes the correlations between DI and the types of FI. For this purpose, the number of provisions containing a given type of discretion was divided by the total number of provisions in a directive. This was correlated with the DI index. Of the five types of discretion, references to the national legal order and discretion on a case-by-case basis show (highly) significant correlations with the occurrence of DI provisions. The other three types of discretion are not significantly correlated with DI.

Overall, the quantitative analysis of the relationship between FI and DI confirms the hypothesised positive correlation between both types of measures aimed at accommodating heterogeneity in the EU legal order. This indicates that legislative acts with a large proportion of discretionary provisions are likely also to include forms of DI and vice versa. The meaning of the findings on types of discretion is more difficult to interpret purely based on the quantitative data. We will return to this after the qualitative examination in the next section.

The uses of DI and FI: a qualitative analysis

Although the quantitative analysis shows an overall association between DI and FI, it sheds less light on the way these two forms of differentiation are used in directives. In order to obtain more insight into this use and the rationales behind it, we zoom in on a number of cases that exhibit particular combinations of DI and FI. These directives are highlighted in . As indicated above, we expect DI to be primarily used to accommodate heterogeneity of preferences about the level and scope of integration, while FI is primarily used to accommodate implementation problems (H2). Moreover, we expect that DI is used to accommodate individual outliers, while FI is used to address widespread concerns (H3).

Directives with high DI and high FI

The first subgroup includes four directivesFootnote7 that score high on both implementation flexibility for member states and opt-outs. All these directives closely relate to the politically very sensitive areas of labour market regulation and justice and home affairs. Three of them cover issues of residence and work of third-country nationals in the EU, and one deals with the European arrest warrant procedure. Consequently, the structure of individual opt-outs was identical. All opt-outs applied to the same set of three countries, Denmark, Ireland, and the United Kingdom, which had obtained general opt-outs from the area of justice and home affairs.

The directives in this group belong to the shorter ones; all of them consist of less than a hundred codable provisions. Despite being shorter than the mean or median directive in the whole sample of 164 directives, the directives in the subgroup have comparatively more recitals in the preamble. A longer list of recitals may indicate policy complexity of legal acts touching upon many important issues (Franchino Citation2007; Migliorati Citation2021; Thomson and Torenvlied Citation2011; Toshkov Citation2008), but also controversy (Kaeding Citation2008) or salience of the legal act (Häge Citation2007). The median directive out of these four also took a longer time on average to negotiate than the median directive of the whole sample. Moreover, a high number of documents in the Council Registry hints towards conflicts during political negotiations among member states. Indeed, all four directives made it multiple times on the Council agenda as B items. On the contrary, the European Parliament remained largely inactive, as its committees tabled an unusually low number of amendment proposals. Finally, a large number of implementing acts shows that member states needed to adjust their domestic legal orders significantly in order to implement the requirements of these directives. While the four directives grant considerable discretion to member states, they do not include many constraints.

The uniform pattern of three states with full opt-outs shows the ‘trickle-down’ effect of a treaty-based approach to legislative differentiation. The other member states, which are fully covered by the directives, are given many opportunities to twist provisions to domestic circumstances and preferences. The directives include a lot of elaboration discretion and references to the national legal order. Sometimes minimum harmonisation is added. This is also reflected in the preambles, which explicitly state which member state competences are not touched by the directives and point out the large differences between the criminal justice systems of the member states.

Directives with high DI and low FI

The four directives in this subgroup relate to a mix of policy areas. Two touch on criminal law,Footnote8 one on transport,Footnote9 and one on environmental policy.Footnote10 These directives display fairly similar characteristics in terms of background variables. Measures relating to conflict in the decision-making process, such as days of negotiations, occurrence as B items on the Council agenda, and the number of documents in the Council registry, are slightly lower than in the case of directives with high values on both DI and FI. In addition, the directives in the high DI/low FI group relate to fewer issue areas and have been transposed with fewer national implementing acts than those in the previous group.

Two reasons for granting opt-outs arose in this group of directives. Two directives touch on sensitive issues of the Area of Freedom, Security and Justice, to which the Treaty-based opt-outs for Denmark and the UK applied. Interestingly, Ireland decided to opt in to these directives, thereby reversing its Treaty-based opt-out. The opt-outs for the other two directives have structural reasons. Five landlocked member states do not need to implement Directive 2014/89/EU establishing a framework for maritime spatial planningFootnote11 and two countries without railway systems – Cyprus and Malta – do not participate in Directive 2007/59/EC on the certification of train drivers operating locomotives and trains ‘as long as no railway system is established within their territory’.Footnote12

Directive 2014/89/EU establishing a framework for maritime spatial planning represents an outlier in the whole dataset. While scoring highest on the DI index, it belongs to the bottom quartile on the FI index. The legislative process took 16 months and did not produce any complications – as the only proposal in the subgroup, it has not been listed as a B item in the Council.

The three remaining directives pose an interesting puzzle because all of them stirred a political conflict among member states, appearing twice as a B item on the Council’s agenda. Yet, these directives allow states only a relatively low level of discretion. Directive 2007/59/EC on the certification of train drivers underwent more than three and half years of negotiations until it was finally approved. It sought to overcome considerable differences among national laws on the certification conditions for train drivers to support their free movement by setting minimum requirements. The directive follows a joint agreement by European Transport Workers’ Federation and the Community of European Railways, hence enjoying support of key stakeholders. The directive does not contain many discretionary provisions, but they cover important points. These crucial points include the minimum harmonisation approach, the possibility to exclude certain categories of train drivers from implementation, and a gradual phasing-in so that previous train drivers’ certifications stay valid for a long time. Moreover, the directive does not apply to more demanding complementary certificates and states can also utilise the directive’s ambiguous language,Footnote13 which opens space for national solutions.

Similar to the train drivers directive, both criminal law directives in this subgroup – on market abuse, and on the freezing and confiscation of instrumentalities and proceeds of crime – established minimum rules for given area. Both directives built on pre-existing EU legal frameworks, which, however, had not operated fully effectively due to persistent differences in national laws and practices. The relatively small number of explicit discretionary provisions leaves member states a number of possibilities to deviate from the directives. This is embodied in particular in the minimum harmonisation approach. Moreover, the directives lower possible disagreements among states flowing from their differing preferences by narrowing the scope and objective (Simonato Citation2015: 220) or ambiguous wording (Chitimira Citation2017).

Directives with low DI and high FI

The sample of 164 directives includes 129 directives that apply to all member states. This subgroup with no instances of DI differs widely in terms of FI, as the weighted ratio of discretion ranges from zero to 59. The subgroup of directives that combine low DI with high FI concerns the fields of transportFootnote14 and the internal market.Footnote15 This subgroup is characterised by directives with comparatively lower levels of salience and political conflict than in the case of the two previous subgroups with non-zero DI. They have much fewer recitals in their preambles and tend to be shorter. It took a shorter time to pass them, the Council stored fewer documents in the Council Registry, and the European Parliament committees tabled fewer amendment proposals. Only one directive out of the five appeared as a B item on the Council agenda, and all passed in the first reading, which indicates a low level of inter-state and inter-institutional conflict. Member states, on average, needed much fewer implementing acts than in the previous two subgroups.

The directives deal with issues such as navigability licences for vessels, roadworthiness tests for motor vehicles, cross-border exchange of information on traffic offences, or rights of shareholders in listed companies. They concern quite specialised partial single market issues with elaborate standards on the national level. The directives often deal with details and approach them on the basis of individual provisions that provide some discretion. Directive 2009/40/EC 6 May 2009 on roadworthiness tests for motor vehicles and their trailers may serve as an example. After setting general provisions, the directive allows for various exceptions. Member states can, for example, exclude from the directive’s scope vehicles of armed forces, police and the fire service. They may also exclude vehicles of historic standards, for which they may set their own testing standards. Moreover, as regards vehicles generally, states may shorten intervals between compulsory tests, prescribe additional tests, etcetera. Such a legal solution hints towards a situation of differing national standards in a politically not so contentious area which would benefit from some alignment of standards but at the same time needs to allow for national peculiarities.

Directives with low DI and low FI

The subgroup with no opt-outs and zero or very low levels of discretion for member states consists of four directives in the policy field of health and consumer protectionFootnote16 and one directive in environment and energy.Footnote17 Three of these five directives are so-called recasts, which means that the directives incorporate previous legal acts and amend them, resulting in a single legal act. The subgroup scores even slightly lower than the subgroup with zero DI and high FI in terms of political salience and conflict, with fewer documents in the Council Registry, fewer amendment proposals tabled by European Parliament committees and fewer national implementing acts. The directives in this subgroup also tend to be short and with a high ratio of constraints when their provisions offer discretion for member states.Footnote18

The directives deal with radioactive substances in water, emissions from air condition systems in motor vehicles, foodstuffs for particular nutritional uses, colouring matters in medicinal products, and transparency of gas and electricity prices. Similar to the previous group, the directives include detailed particular rules; however, they do not permit much discretion. For example, Directive 2009/39/EC on foodstuffs intended for particular nutritional uses contains a number of definitions and invitations for the Commission (but typically not for member states) to elaborate further. When there is a possibility for a member state to depart from the provisions, it is accompanied by constraints. States may, for instance, temporarily suspend or restrict trade in a foodstuff when they have detailed grounds for establishing that it endangers human health, but they then immediately have to inform the Commission and other member states and give reasons.

Discussion: patterns of DI and FI in the four groups

This section zoomed in on groups of directives with extreme or divergent DI and FI scores. The policy field largely determines the membership in the groups. One type of directives with high DI scores simply reflected naturally or structurally determined situations of landlocked countries or member states without railway systems. The other sub-group consisted of justice and home affairs-related directives which typically included opt-outs by the UK, Denmark and sometimes Ireland. These directives are associated with measures of heightened political conflict – they are sensitive also for other states. Directives dealing with third-country nationals recorded, in addition to their high DI scores, also high levels of flexibility for member states’ implementation. The directives with high DI but low FI used different techniques to both placate conflicts and deal with differences among member states. They adopted a minimum harmonisation approach, permitted states to determine the scope of application in some controversial situations and used ambiguous language.

The directives with full membership (i.e. with a zero DI score) differed considerably in terms of FI. Directives with high discretion for member states concerned transport (e.g. licences or tests) and company law. They included detailed provisions with the possibility for states to come up with their own partial solutions. The last group of directives, with zero DI and zero or very low FI, related especially to public health. They are aimed at providing a uniformly high level of protection of health which cannot not be attenuated by the possibility for member states to depart from the common standards.

Based on the qualitative analysis, we can also reflect further on the correlations between DI and the various types of FI that we found in the previous section. Because it is inductive, this reflection remains speculative and ad hoc, but it may offer leads for future studies. As we saw, DI was correlated significantly with references to the national legal order and discretion on a case-by-case basis, but not with elaboration discretion, minimum harmonisation and scope discretion. Looking specifically at the directives in the low DI-high FI category, it appears that elaboration discretion and scope discretion are used for more ‘technical’ issues than DI. As a result, their use is relatively independent from the use of DI. The role of minimum harmonisation is less clear in this regard, as it may also concern value-laden political considerations. Apparently, however, it is not used for the kind of sovereignty and structural concerns that drive DI.

References to the national legal order mainly concern provisions that allow for the use of national procedures and of national legal definitions for concepts in EU directives. This may help to allay concerns on the part of member states that EU legislation intrudes too much on domestic legislative choices. The same (sovereignty) concerns then lead to opt-outs (for some member states) and references to national legal concepts and procedures for others. Likewise, discretion on a case-by-case basis may serve as a ‘safety valve’ for member states, which allows them to set aside EU-level rules in specific situations.

Conclusions

In this article, we examined the relationship between differentiated integration and flexibility in implementation in EU directives. Our analysis started from the observation that these two forms of differentiation respond to similar heterogeneity concerns within the EU. For that reason, we expected the use of DI and FI to be positively associated (H1). At the same time, DI and FI address these underlying concerns in different ways. Whereas DI exempts certain member states altogether, FI offers flexibility to mould legislative provisions to all member states. For that reason, we also expected DI and FI to be used for different forms of heterogeneity. DI was hypothesised to address sovereignty concerns arising from heterogeneity of preferences about the level and scope of integration among member states and FI to address implementation problems (H2). Moreover, we expected DI to be used to accommodate individual outliers and FI to address widespread concerns among member states (H3).

Our quantitative analysis showed a positive correlation between the occurrence of opt-outs (DI) and flexibility provisions (FI) in the directives in our dataset. This confirms H1 and suggests that DI and FI indeed respond to similar concerns. Arguably, DI and FI are two different ways to address heterogeneity in the EU. They can therefore be seen as specific forms of the more general notion of ‘differentiation’ in the EU.

At the same time, our qualitative examination of groups of directives with different combinations of DI and FI showed striking differences in the levels of controversiality during decision-making, as borne out by indicators of conflict such as the time it took to negotiate the directives, the number of Council documents produced during the decision-making process, and the number of times a directive appeared as a B-item in the Council. Directives with high levels of DI and high levels of FI were most controversial. Apparently, these directives raised concerns among all member states, also beyond the three member states that had overall opt-outs for those directives. Directives with high DI and low FI were somewhat less controversial, while directives with low levels of DI showed least controversy regardless of the level of FI. This suggests that DI is used more than FI to address controversial issues.

These qualitative analyses also showed that H2 only captures part of the way these two forms of differentiation are used. In some directives, DI was indeed used to address sovereignty concerns. Directives in the field of justice and home affairs are a case in point. However, in other cases DI was used to exempt member states for which a directive was irrelevant for structural (geographical) reasons. Examples are landlocked states that were exempted from the directive on maritime spatial planning and member states without a railway system that received an opt-out from the directive on train drivers. Sovereignty concerns and structural reasons, then, are two different rationales for using DI, alongside the transitory use of DI that is used in times of enlargement (Schimmelfennig and Winzen (Citation2014) ‘instrumental differentiation’).

Likewise, the expectation in H2 that FI would be primarily used to accommodate implementation problems also requires nuance. In several cases with high FI, flexibility was used to allow member states to tailor EU-wide standards to national specificities, as for instance in the specific roadworthiness requirements for certain types of vehicles. This does not necessarily have to do with implementation problems, but may also reflect differences ‘on the ground’, for instance in the existence and use of certain types of vehicles across member states. The same is the case for the directives in the field justice and home affairs that show both high DI and high FI.

H3 obtained stronger support in our case analyses. DI is indeed used to address concerns on the part of a limited number of specific member states, whether they are related to sovereignty concerns of structural reasons. For these types of issues, FI does both too much and too little: too much as it also allows flexibility to (the vast majority of) member states that do not need it, and too little as it still requires dissenting member states to be part of the overall framework. In those cases, DI is both a more targeted and a more far-reaching way of addressing (fundamental) concerns. FI is used to address more widespread forms of heterogeneity, which are relevant to most or at least a large part of all member states. In those cases, a patchwork of individual opt-outs would both be impractical and lead to overly detailed and rigid frameworks.

Overall then, FI is partly an equivalent to DI (as it is used to address similar heterogeneity concerns) and partly complementary to DI (as it addresses specific types of heterogeneity). In certain situations, DI seems the most logical way to address heterogeneity. In particular, this is the case if a member state wants to be exempted from a directive altogether and if only one or a few member states have serious concerns. Although in this way certain ‘idealtypical’ uses of DI and FI can be discerned, in many cases the two forms are linked. Heterogeneity hardly ever comes in only one form but relates to various aspects of an EU legislative act and its underlying policy issue. In practice, DI and FI therefore form different parts of the same ‘legislative toolbox’, which are used to address different aspects of the same underlying heterogeneity issues.

For future research, this has two implications. The literature on differentiation in the EU, which has focussed predominantly on forms of DI, could broaden its scope by also taking into account forms of FI as a way to address heterogeneity. This includes further analyses of the way these two forms of differentiation work together, for which this article offers a first step. The literature on implementation in the EU, which has mostly sought to describe and explain variation in implementation practices among member states, could take up the question to what extent and under what conditions flexibility in EU legislation leads to actual variation in implementation practices, and whether this offers a solution to the heterogeneity issues that formed the rationale for including the flexibility to begin with. This would broaden the analysis from the determinants of patterns of implementation towards the implications these patterns have for the functioning of the EU.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jan Pollex and Eva Thomann, as well as two anonymous WEP reviewers, for their comments on earlier versions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sebastiaan Princen

Sebastiaan Princen is Associate Professor at Utrecht University’s School of Governance. His research focuses on policy making in the European Union. His books include Agenda-setting in the European Union (2009, Palgrave) and The Politics of the European Union (with Herman Lelieveldt, 3rd ed., 2023, CUP). [[email protected]]

Frank Schimmelfennig

Frank Schimmelfennig is Professor of European Politics at ETH Zurich, Centre for Comparative and International Studies. His recent books include Ever Looser Union? Differentiated European Integration (OUP, 2020, with Thomas Winzen) and Integration and Differentiation in the European Union (Palgrave 2022, with Dirk Leuffen and Berthold Rittberger). [[email protected]]

Ronja Sczepanski

Ronja Sczepanski is a post-doctoral researcher at the Department of Political Science at ETH Zurich. Her research focuses on social identities in Europe and differentiated integration in secondary law in the EU. [[email protected]]

Hubert Smekal

Hubert Smekal is Lecturer at the Maynooth University School of Law and Criminology. His research interests include: courts and judges, human rights, and EU Law. He has published in European Union Politics, European Constitutional Law Review, and German Law Journal, amongst other. [[email protected]]

Robert Zbiral

Robert Zbiral is Associate Professor at the Department of Constitutional Law and Political Science, Faculty of Law, Masaryk University in Brno. His research focuses on legislative process and implementation of EU law. He has published in journals such as Common Market Law Review, Journal of European Public Policy, European Union Politics and Party Politics. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 If a member state had an opt-out for an entire directive, each provision in that directive was counted as an individual opt-out.

2 The following types of constraints were distinguished: substantive standards, reporting requirements, approval by an EU institution, time limits on the exercise of discretion, and the imposition of spending limits. The types of constraints are not used in the analysis in this article.

3 The EUDIFF2 dataset and codebook are available at www.research-collection.ethz.ch/handle/20.500.11850/538562; the FIEU dataset and codebook are available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/I7BZGU.

4 Because flexibility provisions apply (by definition) to all member states, no weighting for the number of member states is needed here.

5 Directive 2013/32 on common procedures for granting and withdrawing international protection.

6 Directive 2006/112 on the common system of value added tax.

7 Directive 2011/98/EU on a single application procedure for a single permit for third-country nationals to reside and work in the territory of a Member State and on a common set of rights for third-country workers legally residing in a Member State; Directive 2014/36/EU on the conditions of entry and stay of third-country nationals for the purpose of employment as seasonal workers; Directive 2013/48/EU on the right of access to a lawyer in criminal proceedings and in European arrest warrant proceedings, and on the right to have a third party informed upon deprivation of liberty and to communicate with third persons and with consular authorities while deprived of liberty; Council Directive 2009/50/EC on the conditions of entry and residence of third-country nationals for the purposes of highly qualified employment.

8 Directive 2014/42/EU on the freezing and confiscation of instrumentalities and proceeds of crime in the European Union, Directive 2014/57/EU on criminal sanctions for market abuse (market abuse directive).

9 Directive 2007/59/EC on the certification of train drivers operating locomotives and trains on the railway system in the Community.

10 Directive 2014/89/EU establishing a framework for maritime spatial planning.

11 Directive 2014/89/EU, Art. 15(4).

12 Art. 36(3) of Directive 2007/59/EC.

13 Commission Staff Working Document Executive Summary of the Evaluation of Directive 2007/59/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2007 on the certification of train drivers operating locomotives and trains on the railway system in the Community, SWD (2020) 138 final, 14 July 2020, https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-9636-2020-INIT/en/pdf, p. 2.

14 Directive 2009/100/EC on reciprocal recognition of navigability licences for inland waterway vessels; Directive 2009/40/EC on roadworthiness tests for motor vehicles and their trailers (Recast); and Directive (EU) 2015/413 facilitating cross-border exchange of information on road-safety-related traffic offences.

15 Directive 2012/30/EU on coordination of safeguards which, for the protection of the interests of members and others, are required by Member States of companies within the meaning of the second paragraph of Article 54 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, in respect of the formation of public limited liability companies and the maintenance and alteration of their capital, with a view to making such safeguards equivalent; and Directive 2007/36/EC on the exercise of certain rights of shareholders in listed companies.

16 Council Directive 2013/51/Euratom laying down requirements for the protection of the health of the general public with regard to radioactive substances in water intended for human consumption; Directive 2009/39/EC on foodstuffs intended for particular nutritional uses (recast); Directive 2008/92/EC concerning a Community procedure to improve the transparency of gas and electricity prices charged to industrial end-users (recast); and Directive 2009/35/EC on the colouring matters which may be added to medicinal products (recast).

17 Directive 2006/40/EC relating to emissions from air conditioning systems in motor vehicles and amending Council Directive 70/156/EEC.

18 Two directives offer no discretion and the highest FI score in this subgroup stands at 2.5.

References

- Andersen, Svein S., and Nick Sitter (2006). ‘Differentiated Integration: What Is It and How Much Can the EU Accommodate?’, Journal of European Integration, 28:4, 313–30.

- Arregui, Javier, and Clement Perarnaud (2022). ‘A New Dataset on Legislative Decision-Making in the European Union: The DEU III Dataset’, Journal of European Public Policy, 29:1, 12–22.

- Bellamy, Richard, and Sandra Kröger (2017). ‘A Demoicratic Justification of Differentiated Integration in a Heterogeneous EU’, Journal of European Integration, 39:5, 625–39.

- Chitimira, Howard (2017). ‘A Historical Overview of the General Implementation of the European Union Market Abuse Directive in the United Kingdom before Brexit and Its Future Implications’, Maastricht Journal of European and Comparative Law, 24:2, 217–44.

- Dimitrova, Antoaneta, and Bernard Steunenberg (2000). ‘The Search for Convergence of National Policies in the European Union’, European Union Politics, 1:2, 201–26.

- Duttle, Thomas, Katharina Holzinger, Thomas Malang, Thomas Schäubli, Frank Schimmelfennig, and Thomas Winzen (2017). ‘Opting Out from European Legislation: The Differentiation of Secondary Law’, Journal of European Public Policy, 24:3, 406–28.

- Dyson, Kenneth and Angelos Sepos, eds. (2010). Which Europe? The Politics of Differentiated Integration. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- European Commission (2017). ‘White Paper on the Future of Europe. Reflections and Scenarios for the EU27 by 2025’, COM (2017) 2025, 1 March 2017, Brussels: European Commission.

- European Council (2014). ‘Conclusions of the European Council of 26/27 June 2014’, EUCO 79/14, Brussels, 27 June 2014.

- Franchino, Fabio (2001). ‘Delegation and Constraints in the National Execution of the EC Policies: A Longitudinal and Qualitative Analysis’, West European Politics, 24:4, 169–92.

- Franchino, Fabio (2004). ‘Delegating Powers in the European Community’, British Journal of Political Science, 34:2, 269–93.

- Franchino, Fabio (2007). The Powers of the Union: Delegation in the EU. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gastinger, Markus, and Eugénia C. Heldt (2022). ‘Measuring Actual Discretion of the European Commission: Using the Discretion Index to Guide Empirical Research’, European Union Politics, 23:3, 541–58.

- Genschel, Philipp, and Markus Jachtenfuchs, eds. (2014). Beyond the Regulatory Polity? The European Integration of Core State Powers. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Häge, Frank M. (2007). ‘Committee Decision-Making in the Council of the European Union’, European Union Politics, 8:3, 299–328.

- Hartmann, Josephine M. (2016). ‘A Blessing in Disguise? Discretion in the Context of EU Decision-Making, National Transposition and Legitimacy Regarding EU Directives’, PhD Dissertation, Leiden University. Available at https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/handle/1887/43331.

- Hofelich, Tobias C. (2022). ‘De Facto Differentiation in the European Union: Circumventing Rules, Law, and Rule of Law’, in Benjamin Leruth, Stefan Gänzle and Jarle Trondal (eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Differentiation in the European Union. London and New York: Routledge, 66–80.

- Holzinger, Katharina, and Frank Schimmelfennig (2012). ‘Differentiated Integration in the European Union: Many Concepts, Sparse Theory, Few Data’, Journal of European Public Policy, 19:2, 292–305.

- Jensen, Christian B., and Jonathan B. Slapin (2012). ‘Institutional Hokey-Pokey: The Politics of Multispeed Integration in the European Union’, Journal of European Public Policy, 19:6, 779–95.

- Kaeding, Michael (2008). ‘Lost in Translation or Full Steam Ahead. The Transposition of EU Transport Directives across Member States’, European Union Politics, 9:1, 115–43.

- Leuffen, Dirk, Berthold Rittberger, and Frank Schimmelfennig (2013). Differentiated Integration. Explaining Variation in the European Union. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lord, Christopher (2015). ‘Utopia or Dystopia? Towards a Normative Analysis of Differentiated Integration’, Journal of European Public Policy, 22:6, 783–98.

- Migliorati, Marta (2021). ‘Where Does Implementation Lie? Assessing the Determinants of Delegation and Discretion in Post-Maastricht European Union’, Journal of Public Policy, 41:3, 489–514.

- Migliorati, Marta (2022). ‘Postfunctional Differentiation, Functional Reintegration: The Danish Case in Justice and Home Affairs’, Journal of European Public Policy, 29:7, 1112–34.

- Princen, Sebastiaan (2022). ‘Differentiated Implementation of EU Law and Policies’, in Jale Tosun and Paolo Graziano (eds.), Encyclopedia of European Union Public Policy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Princen, Sebastiaan, Hubert Smekal, and Robert Zbiral (2019). ‘Codebook Flexible Implementation in EU Law’, Deliverable D7.1, InDivEU project, 26 June 2019.

- Schimmelfennig, Frank, and Thomas Winzen (2014). ‘Instrumental and Constitutional Differentiation in the European Union’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 52:2, 354–70.

- Schimmelfennig, Frank, and Thomas Winzen (2020). Ever Looser Union? Differentiated European Integration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Simonato, Michele (2015). ‘Directive 2014/42/EU and Non-Conviction Based Confiscation: A Step Forward on Asset Recovery?’, New Journal of European Criminal Law, 6:2, 213–28.

- Steunenberg, Bernard, and Dimiter Toshkov (2009). ‘Comparing Transposition in the 27 Member States of the EU: The Impact of Discretion and Legal Fit’, Journal of European Public Policy, 16:7, 951–70.

- Stubb, Alexander (1996). ‘A Categorization of Differentiated Integration’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 34:2, 283–95.

- Thomann, Eva (2015). ‘Customizing Europe: Transposition as Bottom-up Implementation’, Journal of European Public Policy, 22:10, 1368–87.

- Thomson, Robert, and René Torenvlied (2011). ‘Information, Commitment and Consensus: A Comparison of Three Perspectives on Delegation in the European Union’, British Journal of Political Science, 41:1, 139–59.

- Toshkov, Dimiter (2008). ‘Embracing European Law: Compliance with EU Directives in Central and Eastern Europe’, European Union Politics, 9:3, 379–402.

- Tuytschaever, Filip (1999). Differentiation in European Union Law. Oxford: Hart Publishing.

- Van den Brink, Ton (2017). ‘Refining the Division of Competences in the EU: National Discretion in EU Legislation’, in Sacha Garben and Inge Govaere (eds.), The Division of Competences between the EU and the Member States. Reflections on the Past, the Present and the Future. Oxford: Hart Publishing, 251–75.

- Zbiral, Robert, Sebastiaan Princen, and Hubert Smekal (2022). ‘Differentiation through Flexibility in Implementation: Strategic and Substantive Uses of Discretion in EU Directives’, European Union Politics, 24:1, 146511652211260.

- Zhelyazkova, Asya, and Eva Thomann (2022). ‘I Did It My Way: Customisation and Practical Compliance with EU Policies’, Journal of European Public Policy, 29:3, 427–47.