Abstract

The vast majority of elections in parliamentary systems result in minority situations. During cabinet formation, parties have three options: building a winning coalition, a genuine substantive minority cabinet without support, or a formal minority with institutionalised long-term support partnerships. Even though the use of permanent support partners has increased substantially, there is still comparatively little knowledge about the circumstances under which parties choose to enter such formalised support partnerships instead of winning coalitions. This article aims to close this gap by analysing how the party system, the institutional configuration, as well as the bargaining environment influence which cabinet type forms. The dataset includes 469 cabinets from 27 Eastern and Western European countries between 1970 and 2019. The hypotheses are tested with the help of multinomial model estimations. While only few of the traditional explanations can explain the formation of formal minority cabinets, the results show that there is a time-trend towards more formalisation.

‘Good evening. We will get a new red-green government in Denmark’, Pia Olsen Dyhr, the party leader of the left-wing Socialist People’s Party, posted on Twitter late in the evening of 25 June 2019. Alongside she tweeted a picture of the party leaders of four centre-left parties sitting on a table after 18 intense days of negotiations. This constituted the longest government formation period in Denmark since the late 1980s. However, the actual government that was presented the next day, was a single-party minority cabinet formed by the Social Democrats alone. Still, the cooperation between the three support parties and the minority cabinet has been perceived as so institutionalised and committed that the support partners framed it like a coalition cabinet. This type of formalised supported minority governments has become more popular over the last decades and can be observed in countries with and without minority cabinet experience (Krauss and Thürk Citation2022). In this article, we shed light on the circumstances under which minority cabinets form such institutionalised relationships with non-cabinet parties.

When elections result in minority situations in parliament, parties have different alternatives to form a lasting government. Traditionally, research has investigated the circumstances of why minority cabinets form instead of majority coalitions (e.g. Bassi Citation2017; Bergman Citation1993; Crombez Citation1996; Mitchell and Nyblade Citation2008; Thürk et al. Citation2021). However, research on minority governments shows that there are two distinct types of minority cabinets (Damgaard Citation1969; Strøm Citation1990b). First, minority cabinets with permanent support for crucial legislative votes. Strøm (Citation1990b) calls those cabinets formal minority government since they resemble de facto majority coalitions on the legislative level. Second, minority cabinets can form without permanent partners but build shifting majorities in parliament instead, i.e. changing their partners depending on the policy area. This type of ‘genuine’ minority government is referred to as substantive minority cabinet (Strøm Citation1990b).

Previous literature shows that these two types of minority cabinets differ substantially and underlines the trade-off government parties face when forming minority cabinets: if they close formalised support agreements, minority cabinets are more stable (Krauss and Thürk Citation2022) and more likely to control the legislative process (Thürk Citation2022). However, entering this type of commitment also means that cabinet parties have to make substantial policy concessions to their non-cabinet partners (Anghel and Thürk Citation2021; Bale and Bergman Citation2006a; Strøm Citation1990b). Consequentially, parties have to carefully consider their options and weigh the cost and benefits. So far, however, the literature has neglected to study the circumstances when and why parties enter such formally supported minority governments.

Identifying formal support partnerships and understanding which factors lead to their formation is important in order to understand legislative behaviour, policy making and party competition. For instance, previous research has shown that support parties vote with the cabinet most of the time (Otjes and Louwerse Citation2013) and that they are more likely to enter legislative agreements with the minority cabinet (Christiansen and Pedersen Citation2014). Hence, formal support parties substantially affect government policies and ensure that minority cabinets work rather similarly to majority coalitions.

The distinction between the cabinet types has important implications for the transparency and representation of governance. Under substantive minority cabinets, the electorate has to make great efforts to follow which parties are involved in which decision-making processes due to the changing natures of legislative coalitions. Moreover, policy formulation takes place ‘behind closed doors', especially under minority cabinets (Thürk Citation2022), which increases the difficulties for voters to identify the responsible actors and to hold them accountable. In contrast, in formal minority cabinets, formal support parties are able to substantially draw policies into the direction of their own ideal points which in turn crucially affects the representation of the median voter. Moreover, the electorate commonly has difficulties to distinguish coalition members from formal support partners (Tromborg et al. Citation2019). This has considerable consequences for the functioning of representative democracy in terms of the mandate theory and the responsible party model (e.g. Downs Citation1957; Kirkpatrick Citation1971; Klingemann et al. Citation1994; Powell Citation2000).

We contribute to the existing literature by studying all three formation alternatives parties have in parliamentary minority situations: forming genuine substantive minority governments, formally supported minority cabinets, or majority coalitions. Following the existing literature, we formulate theoretical expectations about the circumstances under which parties form those different cabinet types. We derive our hypotheses based on three major theoretical approaches: First, the complexity of the bargaining environment in parliament, i.e. fragmentation and polarisation (e.g. Saalfeld Citation2008); second, the attributes of the cabinet member(s), e.g. the centrality and size of the involved parties (e.g. Crombez Citation1996) as well as their partisan attributes; and third, the institutional settings during cabinet formation (e.g. Strøm et al. Citation1994).

We test our hypotheses based on a newly compiled data set of 469 cabinets in 27 European parliamentary democracies between 1970 and 2019. We estimate multinomial logit models in order to account for the three options. The results of our analysis are rather mixed for the traditional explanations of cabinet formation. We find that the existence of positive parliamentarism and the size of the largest party may explain formal minority cabinet formation. Moreover, we show that partnerships with ethno-regional parties make it more likely that formal minority cabinets are formed instead of majority coalitions since it allows the cooperation to be based on log-rolling strategies. In contrast, our results show no robust effects for most partisan variables such as polarisation or the inclusion of the median party, nor for bicameralism.

However, we find a substantial time effect: the formalisation of minority cabinets has clearly increased over the decades. Similar to the development of longer and more enhanced coalition agreements (Müller and Strøm Citation2008), we observe a so to say formalisation trend of minority cabinets. While there have been basically no formal support agreements before the 1970s, in the 2010s more than two thirds of all minority cabinets in Europe have a formal support partnership. This is a striking finding since the nature of minority cabinets has changed drastically since the seminal work by Strøm (Citation1990b) which is still the baseline for most theoretically assumptions about the behaviour and functioning of minority governments.

From parliamentary minority to cabinet formation

In parliamentary democracies, the electorate does not vote directly for the government, but only indirectly via voting for parties and/or candidates. Therefore, political parties are the main actors as they provide the basis for government formation. Hence, every cabinet is dependent on the (explicit or implicit) support of a legislative majority of parties. We assume parties to behave as unitary (see e.g. de Swaan Citation1973; Riker Citation1962) and rational actors who pursue specific strategies in order to maximise their utility (Downs Citation1957). Following Strøm (Citation1990a), parties may try to maximise their vote, office, or policy benefits. Generally, we assume that parties are first and foremost policy-seeking actors, at least in the long run. Thus, they are aiming at influencing public policies in accordance with their ideal points either due to intrinsic believes (de Swaan Citation1973) or in order to maximise their vote shares (Downs Citation1957).

The lion’s share of parliamentary democracies is characterised by proportional representation and multi-party systems. Consequentially, elections regularly result in minority situations, i.e. no party is able to win an absolute majority. Even in first past the post parliamentary systems, elections do more commonly result in hung parliaments (e.g. since 2010 there have been three hung parliaments in Canada and two in the UK). Previous research has shown that minority situations in parliament substantially complicate the government formation and increase their duration (e.g. Bergman et al. Citation2015; Ecker and Meyer Citation2015; Golder Citation2010).

In the following, we lay out our theoretical expectations regarding the formation of those three cabinet types. We begin by describing the rationality of support agreements before we deduce which factors influence the cabinet formation in minority situations. Therefore, we rely on the previous literature on cabinet formation and derive our hypotheses based on three approaches: (1) the bargaining environment in parliament, (2) the attributes of the cabinet member(s) and (3) the institutional settings.

The rationality behind formally supported minority cabinets

As stated above, when elections result in a minority situation in parliament, parties have three options in order to build a government: substantive or ‘genuine’ minority cabinets, formal minority cabinets with long-term support partnerships, or majority coalitions. In contrast to majority coalitions, minority cabinets, per defintionem, are governments in which the parties in cabinet do not represent an absolute majority (50%+1) of deputies. While this might strike as undemocratic at first glance, minority cabinets are actually most common in countries that rank high in regards to democratic quality and satisfaction, e.g. Denmark, Norway, Sweden or New Zealand.

Still, the formation of majority coalitions is generally considered as the standard outcome of cabinet formation, as it is assumed to be the most rational and secure option (see e.g. Saalfeld Citation2008). The reason behind this is that when in office, parties do not only have the opportunity to enjoy the benefits of office (see e.g. Gamson Citation1961; Riker Citation1962), but it also gives political parties the opportunity to lead ministries and enact policies in line with their preferences (e.g. Budge and Laver Citation1986; Laver and Shepsle Citation1996). However, entering a majority coalition also means to be committed to share those beneficial positions and to make substantial policy (and office) concessions. Previous research has shown that government participation can be electorally harmful (Narud and Valen Citation2008), especially for the junior coalition partner (Hjermitslev Citation2020; Klüver and Spoon Citation2020).

Based on this, Strøm (Citation1990b) explains the rationality of forming minority governments. It can be a reasonable decision for parties to give up office benefits and to stay out of government if they have the possibility to influence policy decisions from the opposition (e.g. through strong legislative committees) and if the parties expect that their government participation could be electorally costly and thus lead to significantly less policy influence in the long run. Or, in other words, they rather wait for ‘more favourable circumstances’ (Strøm, Citation1990b: 69) and tolerate the formation of a minority government in order to keep their chances at the next elections and to increase their long-term policy benefits.

Research shows that minority governments are more likely to form if parliamentary polarisation and fragmentation is high (Dodd Citation1976; Strøm Citation1990b) and if there is a large and centrally located dominant party (Crombez Citation1996; Laver and Shepsle Citation1990). Moreover, some institutional settings of a country may impact the government formation since they increase the majority requirements in parliament. Thus, positive parliamentarism decreases the chances for minority cabinets (e.g. Bergman Citation1993; Cheibub et al. Citation2021; Strøm Citation1990b) as do strong bicameralism and other legislative veto points (e.g. Lijphart Citation1984; Thürk et al. Citation2021).

However, previous research has mainly ignored the differences between distinct types of minority cabinet. Following Strøm (Citation1984, Citation1990b), minority cabinets can be distinguished based on the way how they organise their legislative support. They can either form as substantive minority government or as formal minority cabinet. Substantive minority governments function like ‘genuine’ minority cabinets and pass their policy agenda based on ad hoc legislative coalitions with shifting majorities. Thus, the minority cabinet can choose the legislative partner that is close to its own ideal point on each policy and is not forced to any long-term cooperation. This strategy allows them to work flexibly and effectively and pursue their own policy agenda successfully without too large policy concessions (Green-Pedersen Citation2001; Strøm Citation1990b; Tsebelis Citation2002). However, substantive minority governments are more likely to experience legislative defeat (Thürk Citation2022) and to terminate early (Krauss and Thürk Citation2022). Moreover, this type of minority cabinet depends on non-cabinet parties to be mainly policy oriented and to be (at least to some extent) willing to cooperate with the minority cabinet.

In contrast, formal minority governments work on a long-term basis with permanent non-cabinet parties. The minority cabinet therefore relies on its support parties to form a majority in parliament and to support the cabinet on major legislation in exchange for policy benefits. The definition of support parties is contested (see e.g. Bäck and Bergman Citation2015; Bergman Citation1995; Lijphart Citation1999; Thesen Citation2016) but it is important that such a support relationship is not only spontaneous or of short-term nature but has been explicitly negotiated prior to the formation of the government and is committed to its survival (Strøm Citation1990b: 62). This type of minority cabinet works similarly to majority coalitions – just on the legislative level (Laver and Schofield Citation1990). In some cases, the support agreements are written and publicly available and thus similarly formalised as coalition agreements (Bale and Bergman Citation2006b).

For the cabinet parties, this government alternative might work as a sweet-spot regarding the trade-off between majority coalitions and genuine minority cabinets: On the one hand, this type of minority cabinet is bound by the formal agreement to its support party and has to make policy concessions in exchange for the support. Still, though, the cabinet parties are able to stay in control over the cabinet positions and have the advantage of policy formulation (e.g. Laver and Shepsle Citation1996). On the other hand, formal minority governments are similarly successful and stable as majority coalitions.

Formal minority governments can also be beneficial for the support party. While they gain policy pay-offs, they are not part of the actual government. Thus, they are less often the object of critical media reports (Green-Pedersen et al. Citation2017: 145). Furthermore, support parties are not obliged by coalition unity, but have the opportunity to abstain or even vote against the government. Especially on highly salient policies for ideological distant support parties, they can express their differences from the minority cabinet (Müller Citation2022). Moreover, support parties tend to vote against the minority cabinet in times when media attention is especially high: right at the beginning and the end of the legislative cycle (Müller and König Citation2021). This strategy helps the support party to prominently distinguish itself from the cabinet.

But under which circumstances do parties decide to form more or less secure cabinets? In the following, we follow the existing literature on government formation and derive our hypotheses based on three distinct approaches: (1) the bargaining environment, (2) the cabinet member attributes and (3) the institutional rules.

Bargaining environment and minority cabinet formation

Previous research shows that one driving factor is the complexity of the bargaining environment in parliament, i.e. the parliamentary fragmentation and the polarisation (e.g. de Winter and Dumont Citation2008; Luebbert Citation1986; Martin and Vanberg Citation2003; Powell Citation1982; Strøm Citation1990b; Thürk et al. Citation2021; Warwick Citation1998).

The complexity of the bargaining environment importantly affects which type of cabinet is formed. Previous research has argued that the formation of ideological compact winning coalitions is more complicated under high fragmentation which increases the likelihood for minority cabinets to form (Dodd Citation1976; Sartori Citation1976). We argue, however, that this should be only true for substantive minority cabinets. One important explanatory factor is the available number of potential voting partners a substantive minority cabinet may have. If there are only few options to form ad hoc legislative coalitions, the non-cabinet parties know about their pivotal role for the government which decreases the cabinet’s bargaining power compared to the opposition. In contrast, the minority cabinet’s bargaining power increases if it has a larger number of potential allies to choose from (see e.g. Falcó-Gimeno and Jurado Citation2011).

Regarding the formation of formal minority governments, there is very little research to derive a theoretical expectation from. In the related literature, Klemmensen (Citation2005) as well as Christiansen (Citation2008) have investigated the effect of a minority cabinet’s bargaining power and the parliamentary fragmentation on the adoption of policy-specific legislative agreements in Denmark (so-called ‘forlig’).Footnote1 Interestingly, Klemmensen (Citation2005) finds that parties with a weak bargaining position are more likely to form such policy-specific agreements with non-cabinet parties. Christiansen (Citation2008: 86–92) does not find that bills are more likely to be part of such an agreement dependent on the cabinet’s voting power or the parliamentary fragmentation. The research is thus inconclusive and no clear effect can be derived.

Consequentially, we expect that substantive minority cabinets are more likely to be formed when fragmentation is high since the number of potential legislative coalition partners increases while the formation of compact majority coalitions becomes more complicated and therefore less likely. For formal minority cabinets, we expect no effect of fragmentation. Thus, we hypothesise:

Hypothesis 1:

The higher the party system fragmentation in parliament, the more likely is the formation of substantive minority cabinets and the less likely the formation of majority coalition cabinets.

In highly polarised parliaments, radical parties are more likely to be present in parliament but they are less likely to become government members in coalitions. As coalition members, radical parties would lose momentum and be ‘unlikely to credibly cater for popular protest sentiment’ (Cohen Citation2020: 5). Also, moderate parties might block the possibilities for radical parties to participate in government because they do not want to share executive responsibilities with them. As a consequence, the formation of majority coalitions becomes less likely. Instead, ideological distant parties are likely to prefer supporting minority governments when their formation means the lesser evil in comparison to a majority government of parties from the other end of the political spectrum. This strategy allows the support party to exert at least some policy influence but keep its anti-elite attitude towards the government in front of their electorate because they are not bound by coalition agreements and forced to make unbearable concessions. Following this, we hypothesise:

Hypothesis 2:

The higher the polarisation in parliament, the more likely is the formation of formal minority cabinets with support parties and the less likely the formation of substantive minority governments and majority coalition cabinets.

Cabinet party attributes and minority cabinet formation

Another theoretical approach explaining the formation of minority cabinets concentrates on the attributes of the party or parties forming the cabinet. If a cabinet has a strong bargaining position, it is less important that it forms as a majority coalition. Important factors that determine the government’s bargaining position are the attributes of the largest party but also the tangentiality of the cooperating partners. Following a spatial approach, previous research has focussed on the centrality and size of the largest parliamentary party in order to understand cabinet formation (Baron Citation1991; Crombez Citation1996; Laver and Shepsle Citation1996). The more centrally located in the ideological space and the higher the seat share of the largest party, the stronger its bargaining position.

First, we follow existing research and argue that the median party in parliament has a strong bargaining position. Thus, a median party is more likely to form a substantive minority cabinet. The median party must be included in all ideological compact winning coalitions in parliament and is, due to this strength, able to work with political parties to both of its sides: the ideological left and right. Hence, it can choose between different potential partners for successful ad hoc coalition formation (Crombez Citation1996; Laver and Shepsle Citation1996; Tsebelis Citation2002). This flexibility in the legislative process makes substantive minority cabinets stable even without an institutionalised cooperation. Therefore, we expect governments which encompass the median party to be more likely to form as substantive minority ones:

Hypothesis 3:

The formation of substantive minority cabinets becomes more likely and the formation of formal minority cabinets and majority coalition cabinets less likely if the cabinet includes the median party.

Regarding the effect of the largest party’s size on building formal minority cabinets, we expect a more complicated relationship. Generally, we theorise a decrease in bargaining power of the largest party, the lower its seat share and thus, a higher likelihood to form based on safer, formalised cooperation. However, very large parties, which miss an absolute majority only by few seats, might take advantage of their size in a different way. They can form formalised agreements with small non-cabinet actors based on a log-rolling strategy. This allows the cabinet party to offer very specific, minor pay-offs in exchange for long-term support. An example for this type of relationship is the formalised cooperation of large minority cabinet parties with independent deputies in Ireland or Australia (e.g. Kefford and Weeks Citation2020) or with small regionalist parties in Spain (Field Citation2016). In both cases, large minority cabinet parties can rely on their legislative strength and enter log-rolling relationships. Hence, they do not have to compromise and make concessions with larger parliamentary parties on a regular basis. Instead, they can be sure of their survival and keep the prerogative to decide all other major legislation. Following the logic of parties pursuing log-rolling strategies, we hypothesise a u-shaped curvilinear relationship between the largest party’s size and formal minority cabinets:

Hypothesis 4:

The formation of formally supported minority cabinets is more likely if the largest party is very large or very small. Otherwise, the larger the largest party, the more likely the formation of substantive minority cabinets and the less likely the formation of majority coalition cabinets.

We argue that for some types of parties it is especially beneficial to rather support a minority cabinet than to enter it. This should be particularly true for the cooperation of mainstream parties with ethno-regional parties. Ethno-regional parties are a specific type of niche parties (Meguid Citation2008) and thus classical policy-seekers which are less interested in office positions (Klüver and Spoon Citation2016: 6). The electorate of ethno-regional parties is more heterogeneous regarding social class voting than the electorate of any other type of parties (de Winter Citation1998). Therefore, ethno-regional parties are least interested in influencing national legislation but are willing to support cabinet policies on national matters in exchange for ‘transfers of policy-making authority’ (Heller Citation2002) to their regions or groups (i.e. more autonomy for the group/region or financial support).

Examples are the regional party support of national minority cabinets in Spain (Field Citation2009, Citation2016) or the support of the ethnic minority parties in Romania (Anghel and Thürk Citation2021). In both cases, the parties decided to support even ideological distant minority cabinets in exchange for group specific policy pay-offs. Following this, we posit the following:

Hypothesis 5:

If one partner is an ethno-regional party, the formation of formal minority cabinets becomes more likely and the formation of majority coalition cabinets becomes less likely.

Institutional rules and minority cabinet formation

Additionally, institutions may affect government formation at two different stages: directly during the formation process and indirectly through anticipation of potential barriers during the legislative process later on (Strøm et al. Citation1994; Thürk et al. Citation2021).

Investiture votes belong into the category of institutions that directly impact the cabinet formation process (e.g. Cheibub et al. Citation2021; Rasch et al. Citation2015). Previous research argues that minority cabinets are less likely to form if the cabinet has to win an investiture vote in parliament in order to start governing (e.g. Lijphart Citation1999; Strøm Citation1990a). This should be especially true if this investiture vote requires a legislative majority vote in favour of a new cabinet, i.e. positive parliamentarism (Bergman Citation1993).

However, we argue that positive parliamentarism should only affect substantive ones because non-cabinet parties are more likely to express their confidence in favour of a minority government if they have secured policy benefits in a deal based on formalised cooperation. Thus, we hypothesise:

Hypothesis 6:

Under positive parliamentarism, the formation of substantive minority cabinets is less likely than the formation of formal minority cabinets and majority coalition cabinets.

Hypothesis 7:

If there is a strong second chamber, the formation of substantive minority cabinets is less likely than the formation of formal minority cabinets and majority coalition cabinets.

Table 1. Summary of theoretical arguments.

Research design

In order to test our hypotheses, we analyse the formalisation of minority governments in 27 Western and Eastern European countries between 1970 and 2019.Footnote2 Overall, our dataset contains 469 cabinets. We restrict the sample to government formation in minority situations in parliament, excluding all governments in which a single party had a legislative majority. The rationale behind this is that we are interested in the question how parties form viable cabinets without an own legislative majority. Including a wide range of different countries accounts for unobserved heterogeneity and increases the generalisability of our results. The data mainly originates from two data sets: for the cabinets from Western Europe, we relied on data provided by Bergman et al. (Citation2021) and Hellström et al. (Citation2021), while the data for the Eastern European countries come from the dataset by Bergman et al. (Citation2019). Even though data for the Western European countries is available from 1945, we decided to only include cabinets that formed in the 1970s and later. This is mainly due to the fact that the formalisation of minority governments really only started in the 1970s.

Dependent variable

In order to account for the three options of cabinet formation which parties have in minority situations, our main dependent variable is the type of cabinet that formed. For the main analysis, we rely on a categorical variable with three manifestations: substantive minority cabinets without majority support, formal minority cabinets with long-term majority support, and majority coalition cabinets. The coding for the distinction between majority and minority governments is based on the seat share of the cabinet member parties. If the cabinet members reach a seat share of over 50%, it is coded as majority coalition, otherwise as minority cabinet. To operationalise formal minority cabinets, we rely on the identification of formal support parties by country experts from the PAGED dataset and additionally on data provided by Thürk (Citation2022). Relying on Strøm (Citation1990b), a formal support party has been coded as existent if the party has:

prior to the cabinet formation

publicly announced to support the minority government

on a long-term basis when push comes to shove

and has received pay-offs in exchange.

If the combined legislative seat share of the formal support parties and the cabinet parties accumulates to more than 50%, we classify the minority cabinet as formal minority cabinet with majority support. Otherwise as substantive minority cabinet since at least some additional partner has to be found to pass policies. However, Table A1 and Figure A5 in the online appendix show our results when we distinguish between minority governments with majority support and minority governments with support parties but without majority support.

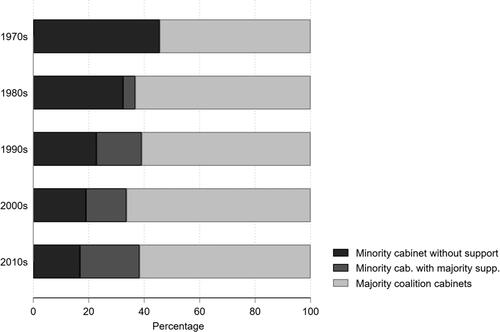

shows the distribution of our dependent variable, dependent on the decades in which the cabinets formed. Our sample includes 118 substantive minority cabinets without majority support, 61 formal minority cabinets with a majority support as well as 290 majority coalition cabinets. also clearly indicates that the formalisation of minority governments increases over time.

Independent variables

We include a number of explanatory and control variables in our analyses. First, we hypothesised that the complexity of the bargaining environment and the previous experience with minority situations influences the level of formalisation. First, in order to measure the fragmentation of the party system we rely on the effective number of parties (Laakso and Taagepera Citation1979). The effective number of parliamentary parties can be seen as an indicator for the complexity of the bargaining environment (Saalfeld Citation2008) and weighs the number of parties by their size. Second, we also include a polarisation variable. In order to operationalise polarisation, we rely on the index proposed by Dalton (Citation2008). The data originates from ParlGov (Döring and Manow Citation2016). However, in line with Strøm (Citation1990b), we estimate additional models including the seat share of radical parties instead of the Dalton index to account for the polarisation in parliament. This variable originates from the data provided by Thürk et al. (Citation2021). The models Tables A2–A4 can be found in the online appendix and largely support our findings presented below.

Table 2. Cabinet types (multinomial).

In order to test our party attributes hypotheses, we include a variable that indicates whether the median party is part of the cabinet (in which case it is coded ‘1') or not (in which case it is coded ‘0'). A second party attributes variable is the seat share of the largest party in parliament. We include this variable also as an interaction effect with itself (i.e. squared) to account for the hypothesised u-shaped relationship. Additionally, we include the ethno-regional party variable in our second analysis. This variable signals whether or not at least one ethno-regional party is part of the parliamentary basis of the government, either as cabinet member or as a support party. We base our operationalisation on the categorisation by the MARPOR data set (Volkens et al. Citation2018). Additionally, we include two institutional variables: the existence of bicameralism and positive parliamentarism. Both variables are dichotomous, meaning that ‘1’ indicates the presence of bicameralism and positive parliamentarism, respectively and ‘0’ the absence of it.

Lastly, we also include three different control variables. First, we include minority experience as a measurement of how used parties in a country are to minority governments in parliament. In order to operationalise this variable, we first calculated for every government the sum of all previous government durations as well as the sum of all minority government durations. In a second step, we then divided the minority government duration by the total government duration. Second, we include a variable that indicates whether or not the government has formed right after an election ('1') or if it formed as a replacement during the legislative term ('0'). Third, we also control for the decades in which the governments formed.

Analysis

We present our results in two sub-sequential parts. In the first part, we include all observations to analyse the circumstances under which parties form one of the three cabinet types. In the second part, we restrict our sample to only minority governments with majority support and majority coalitions in order to test our hypothesis 5, the influence of ethno-regional parties.

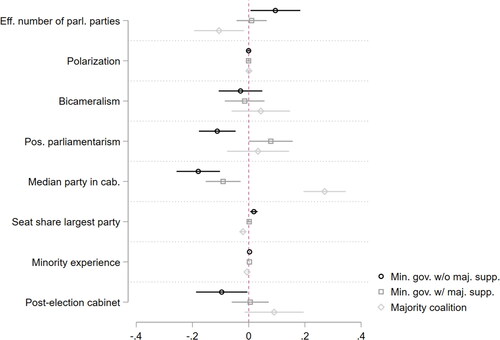

In the first part of our analysis, we rely on a multinomial logit model to test our hypotheses. The results can be found in . All coefficients in the table have to be interpreted with reference to the baseline category of substantive minority governments. Since this is not an intuitive way to interpret the results, we further estimated average marginal effects (AME) for our main explanatory variables. displays the AMEs graphically with 95% confidence intervals, where 0 (the vertical line) indicates no relationship, values less than zero a decreased probability and values greater than zero an increased probability. Plotting the results allows us to show the estimates for all three categories of our dependent variable in comparison.Footnote3

We find that the effective number of parties, the existence of positive parliamentarism, and the seat share of the largest party have a coherent influence on the decision which cabinet to form. In line with our theoretical expectations, we find a negative effect of the effective number of parliamentary parties on the probability to form a majority coalition cabinet and a positive effect on the probability to form a minority cabinet without majority support. Thus, the lower the effective number of parliamentary parties, the higher the probability of forming majority coalitions and the lower the probability of forming substantive minority cabinets. With an increase in the number of effective parties, the pattern reverses (see here also the graphical illustration in Figure A4 in the online appendix).

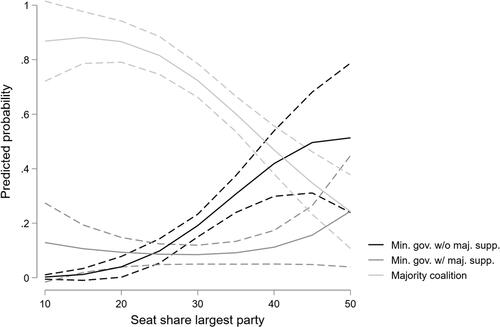

However, the effective number of parliamentary parties does not seem to affect the formation of formally supported minority governments. Moreover, we find that positive parliamentarism decreases the chances of forming a substantive minority government without majority support, but increases the probability that a formally supported minority government or a majority coalition forms. The AME of the seat share of the largest party is positive for minority governments without majority support (thereby increasing the chances of their formation) but is negative for majority coalition cabinets (thereby decreasing the formation chances). The results in for the squared seat share further suggest that there is a saturation effect after which the previously mentioned effects turn to the opposite.

To further illustrate the influence of the seat share of the largest party, we have estimated predicted probabilities.Footnote4 displays the u-shaped relationship between the seat share of the largest parliamentary party and the probability to form a minority government with or without majority support. The probability to form a formal minority cabinet slowly drops from 13% for small largest parties with a seat share of about 10% down to 8.5% for parties with a seat share of 30%. At a seat share of about 40%, the probability increases again up until 24% for parties with a seat share of 50% which miss an absolute majority only by an inch. This is in line with our theoretical expectations: a large party can pay off a small partner with minor specific legislation and gains stability as well as the prerogative to decide all other legislation. Classic examples can be found in Ireland and Australia where minority cabinets often form with the help of a few Independents (Kefford and Weeks Citation2020). The independent MPs get policy benefits, often in form of financial support for local infrastructure in their home districts, and promise support on major legislation and confidence votes in exchange. But also cooperation with smaller parties explain this pattern as e.g. in the UK under Theresa May or commonly in Spain.

Contrary to our theoretical expectations, we find that the probability to form a majority coalition cabinet rather than a substantive (or formal) minority government is higher if the median party is a member of the cabinet. Furthermore, we do not find the theorised effects of polarisation or bicameralism on the formation of the different (minority) cabinet types. In contrast, we find that the timing of cabinet formation plays a substantial role. First, we find that an increased experience with minority governments decreases the likelihood that a majority coalition cabinet forms instead of a minority cabinet. Additionally, the results show that parties are more likely to form majority coalitions directly after general elections and less likely to form substantive minority cabinets without majority support. For the formation of formally supported minority cabinets, we find a strong time effect: over the years it has become more likely to form minority cabinets with formalised support partnerships in contrast to substantive minority cabinets.

In the second part of our analysis section, we restrict our sample to only majority coalitions and formally supported minority cabinets in order to analyse under which circumstances parties form which type of ‘majority’ government. This allows us to test the effect of ethno-regional parties on the formation of both cabinet types. Theoretically, we argued above that a log-rolling strategy may lead to formalised minority cabinets instead of majority coalitions if ethno-regional parties are part of the cabinet’s legislative base. The results of the logistic models can be found in and support our theoretical expectation. The coefficient is positive and statistically significant at the 10% level. Substantially this means that when ethno-regional parties are involved in the government formation process as part of their legislative basis, the probability is higher that a formally supported minority government is formed instead of a majority coalition. Figure A2 in the online appendix graphically displays the results as average marginal effect. Even though the influence of ethno-regional parties is only significant at the 10% level, the influence is comparatively substantially relevant and robust. Aside from this, only minority government experience and the presence of the median party in cabinet can explain why formal minority governments are formed instead of majority coalitions.

Table 3. The effect of ethno-regional parties.

In order to check the robustness of our results, we ran a number of additional analyses. First, we use an alternative operationalisation of our dependent variable. Since our main arguments rest on the assumption that having a majority in the legislature is an important distinction between cabinets, we have decided to allocate those minority governments that do not reach legislative majorities even though they have support parties to the group of substantive minority governments.Footnote5 Table A1 in the online appendix reports the results for this alternative operationalisation. The results suggest that almost none of the theorised variables included can explain this type of minority cabinet.

Second, we substitute the polarisation measure with a variable that measures the share of radical parties in parliament. Previous research has used this variable to operationalise the complexity of the bargaining environment (see e.g. Strøm Citation1984). The results can be found in Tables A2–A4. The share of radical parties does not have a coherent significant influence on the decision which government type forms and our main results remain substantially the same.Footnote6 Third, we also include a number of different model specifications where we add interaction effects (e.g. between the effective number of parliamentary parties and polarisation) and additional control variables (i.e. committee strength based on André et al. Citation2016). Our main results remain substantially the same across the different specifications. Finally, we check for differences between Eastern and Western Europe by including a dummy variable in one model (Table A6) and by running separate analyses for Eastern and Western European countries (Tables A7 and A8). We find that the formalisation of minority governments differs to some degree between the regions, e.g. we do not find a time effect for Eastern Europe. All results and more detailed descriptions of the robustness checks can be found in the online appendix.

Discussion of results

In general, our analysis shows that only some of the traditional arguments debated in the coalition formation literature can explain why formally supported minority cabinets form instead of substantive minority ones or majority coalitions. Our findings show the most robust positive effect on the formation of formally supported minority cabinets for the variables which account for the possibility of parties to organise their cooperation for cabinet support based on log-rolling strategies. Hence, parties prefer to form minority cabinets with long-term support if (a) the largest party misses a parliamentary majority only by an inch and/or (b) if the cooperation for the parliamentary basis of the cabinet includes ethno-regional parties with very specific policy goals which can be reached by supporting a cabinet instead of joining it (e.g. Anghel and Thürk Citation2021; Field Citation2016).

Regarding the traditional arguments of coalition formation, we find that the often-argued negative effect of positive parliamentarism on minority cabinet formation (Bergman Citation1993; Cheibub et al. Citation2021; Strøm Citation1990b) exists only for substantive minority governments, not for formally supported ones, which underlines the importance to distinguish between minority cabinet types. In contrast, fragmentation explains only substantive minority cabinet and majority coalition formation, but fails to explain why or when formal minority cabinets are formed. Other important traditional variables explaining coalition formation, polarisation, median party status, and bicameralism, have not been found to predict the formation of the minority cabinet types. Regarding bicameralism, future studies should account for the partisan composition of the second chamber in order to detect an effect. Regarding the surprising finding that the median party status increases the probability of forming winning coalitions, it could potentially be explained by the fact that today’s politics is too multidimensional. Thus, there is not only one important ideological dimension but several ones and a party could still be centrally located enough in order to form viable (substantive) minority government on some dimension but not on the one captured as main dimension in the data. Further, there could be measurement complications: in order to count as median party, a party has to own the median legislator but in a more multidimensional space with a growing number of (minor) political actors, it is very complicated to locate every party and thus to identify the median position correctly. This might also affect the polarisation measure. New measures of ideological dispersion and centrality would be helpful.

The most robust and substantial predictor of this analysis is the time factor: The formation of formally supported minority cabinets has become more likely over time. This finding also lends support to what has shown descriptively. The predictor is very robust over all model specifications (with the exception of the model for CEE-countries only) and can most likely be explained as part of a general trend of formalisation as e.g. also party manifestos increase (Däubler Citation2012) and coalition agreements become more common and longer (Müller and Strøm Citation2008). Bale and Bergman (Citation2006a) show that even written support contracts become more common for minority cabinets in New Zealand and Sweden. One important reason explaining this formalisation trend in politics might be the increasing complexity and multi-dimensionality of the political agenda. Accordingly, Green-Pedersen (Citation2006) shows that ‘new issues', e.g. immigration and environment, have risen drastically in Danish legislative debates while the traditional cleavage of welfare and economy has become less dominant since the 1980s. Moreover, not only the number of policy areas has increased but there has been a considerable growth of policy portfolios over time and a significant trend of substantial policy accumulation in Western democracies (Adam et al. Citation2019). This increasing complexity of politics has also been discussed as a main reason for an increase in the density of regulation of parliaments in Europe while traditional party system attributes such as polarisation and fragmentation failed as predictors (Sieberer and Höhmann Citation2022). This complexity of today’s politics may lead to more uncertainty which is an important explanation for formalised cooperation such as coalition agreements (Müller and Strøm Citation2008).

What does this formalisation of minority cabinets mean for our understanding of minority governance? Still, most scholars base their theoretical assumptions on the ground-breaking work by Strøm (Citation1990b). He wrote that ‘minority cabinets are typically not coalitions’ (Strøm, Citation1990b: 61, emphasis in original) and that ‘formal minority governments are not a very large proportion of all minority governments’ (Strøm, Citation1990b: 94, emphasis in original). Strøm (Citation1990b: 96) also argues that formal minority cabinets only form in specific countries while we nowadays observe formal minority cabinets and minority coalitions frequently and everywhere, e.g. also in Canada and all Scandinavian countries. Our findings, therefore, underline that we have to take this crucial change of minority governance into account, especially when analysing democratic decision-making processes, government representation, policy responsibility, and policy outcomes under minority governments. Thus, our study has important implications for the field of comparative politics as it underlines that formal support parties, previously largely neglected, need to be taken into consideration.

Conclusion

In this article, we have sought to analyse why parties choose to form specific types of cabinets by including a previously mainly ignored government type: formal minority governments with institutionalised majority support of non-cabinet parties. Previous research shows that this type of minority cabinet behaves fundamentally different from substantive minority governments (Field Citation2016; Krauss and Thürk Citation2022; Thürk Citation2022), however, little is known about the circumstances under which this type forms. We have derived hypotheses based on the three major theoretical approaches previously discussed in coalition theory: the complexity of the bargaining environment, structural attributes of the cabinet, and the institutional environment. However, the traditional explanations seem to explain the formation of formal minority cabinets only to limited extent.

We tested the hypotheses with a new dataset including 469 cabinets from 27 Eastern and Western European countries between 1970 and 2019. We find empirical support for the theoretical expectation that the size of the largest party matters, the party type of the involved (minor) partner, and the existence of positive parliamentarism. Theoretically, we argue that this is due to cabinet parties preferring formal minority cabinets if they can pursue a log-rolling strategy. Thus, if very large parties can pay off minor parliamentary actors or when they cooperate with a political actor who is oriented to a very specific electorate group, such as ethno-regional parties, they are more probable to build formally supported minority cabinets.

Our analysis, though, has also shown that one of the most important predictors of the formation of minority governments with majority support is time. Empirically, we can clearly observe that a so-called formalisation of minority cabinets is taking place. We observe only few formal support parties in the 1970s and 1980s. However, in the 2010s more than two thirds of all minority cabinets in Europe have a formal support partnership which underlines that minority cabinets crucially changed since the seminal studies by Strøm (Citation1990b).

While this article is a first step to understanding the formalisation of minority governments, much is left to be analysed. For instance, further research could analyse the differences in the support relationships. This article only distinguishes different types of minority governments based on having support parties or not. However, these support relationships vary substantially from oral agreements to contracts that are similar to coalition agreements. It is quite likely that parties have different motives depending on which type of support relationship they form. Additionally, it could also be a worthwhile avenue for future research to analyse the behaviour of support parties in, for instance, parliament but potentially also the following electoral campaign. Under which circumstances will support parties try to differentiate themselves from the cabinet parties? Further research might also want to include parliamentary democracies outside of Europe. Canada and New Zealand, for instance, have a strong tradition of minority governance though substantially different majority building strategies can be observed in both countries.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (930.4 KB)Acknowledgements

The list of author names follows a rotation principle. Both authors contributed equally to all work. We thank Hanna Bäck, Johan Hellström and Wolfgang C. Müller as well as the participants of the workshop ‘Advances in Coalition Research: A Dynamic and Comparative Perspective’ for extensive feedback and detailed suggestions. We further thank three anonymous reviewers for their careful reading and helpful comments and are very grateful to Nikolaus Kowarz for excellent research assistance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Maria Thürk

Maria Thürk is a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Social Sciences, University of Basel. Her research focuses on party competition, legislative politics and minority as well as coalition governments. Her research has been published in the European Journal of Political Research, Legislative Studies Quarterly, West European Politics, Government & Opposition and other political science journals. [[email protected]]

Svenja Krauss

Svenja Krauss is a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Government, University of Vienna. Her main research interests are coalition governments, political parties, political behaviour as well as political representation. She has published in the Journal of European Public Policy, West European Politics and Government & Opposition, amongst others. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 These agreements are not formal support agreements, but policy-area specific agreements with a strong tradition in Denmark (e.g. Green-Pedersen and Skjaeveland Citation2020).

2 The countries included are: Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom.

3 For illustration purposes, we do not display the decade variable due to their strong effects.

4 The predicted probabilities for the influence of positive parliamentarism and the effective number of parliamentary parties can be found in Figures A3 and A4 in the online appendix.

5 See Figure A1 for the distribution of this variable over decades.

6 The share of radical parties increases the probability that a majority coalition forms in contrast to a substantive minority government but only for our three-categorical dependent variable.

References

- Adam, Christian, Steffen Hurka, Christoph Knill, and Yves Steinebach (2019). Policy Accumulation and the Democratic Responsiveness Trap. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- André, Audrey, Sam Depauw, and Shane Martin (2016). ‘Trust Is Good, Control Is Better?’, Political Research Quarterly, 69:1, 108–20.

- Anghel, Veronica, and Maria Thürk (2021). ‘Under the Influence: Pay-Offs to Legislative Support Parties under Minority Governments’, Government and Opposition, 56:1, 121–40.

- Bäck, Hanna, and Torbjörn Bergman (2015). ‘The Parties in Government Formation’, in Jon Pierre (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Swedish Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 206–23.

- Bale, Tim, and Torbjörn Bergman (2006a). ‘Captives No Longer, but Servants Still? Contract Parliamentarism and the New Minority Governance in Sweden and New Zealand’, Government and Opposition, 41:3, 422–49.

- Bale, Tim, and Torbjörn Bergman (2006b). ‘A Taste of Honey Is Worse Than None at All?’, Party Politics, 12:2, 189–202.

- Baron, David P. (1991). ‘A Spatial Bargaining Theory of Government Formation in Parliamentary Systems’, American Political Science Review, 85:1, 137–64.

- Bassi, Anna (2017). ‘Policy Preferences in Coalition Formation and the Stability of Minority and Surplus Governments’, The Journal of Politics, 79:1, 250–68.

- Bergman, Torbjörn (1993). ‘Formation Rules and Minority Governments’, European Journal of Political Research, 23:1, 55–66.

- Bergman, Torbjörn (1995). ‘Constitutional Rules and Party Goals in Coalition Formation: An Analysis of Winning Minority Governments in Sweden’, Dissertation, Department of Political Science Umeå University.

- Bergman, Torbjörn, Hanna Bäck, and Johan Hellström (2021). Coalition Governance in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bergman, Torbjörn, Svante Ersson, and Johan Hellström (2015). ‘Government Formation and Breakdown in Western and Central Eastern Europe’, Comparative European Politics, 13:3, 345–75.

- Bergman, Torbjörn, Gabriella Ilonszki, and Wolfgang C. Müller (2019). Coalition Governance in Central Eastern Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Budge, Ian, and Michael Laver (1986). ‘Office Seeking and Policy Pursuit in Coalition Theory’, Legislative Studies Quarterly, 11:4, 485–506.

- Cheibub, José Antonio, Shane Martin, and Bjørn Erik Rasch (2021). ‘Investiture Rules and Formation of Minority Governments in European Parliamentary Democracies’, Party Politics, 27:2, 351–62.

- Christiansen, Flemming Juul (2008). ‘Politiske forlig i Folketinget: Partikonkurrence og samarbejde’, Doctoral dissertation, Forlaget Politica.

- Christiansen, Flemming Juul, and Helene Helboe Pedersen (2014). ‘Minority Coalition Governance in Denmark’, Party Politics, 20:6, 940–9.

- Cohen, Denis (2020). ‘Between Strategy and Protest: How Policy Demand, Political Dissatisfaction and Strategic Incentives Matter for Far-Right Voting’, Political Science Research and Methods, 8:4, 662–76.

- Crombez, Christopher (1996). ‘Minority Governments, Minimal Winning Coalitions and Surplus Majorities in Parliamentary Systems’, European Journal of Political Research, 29:1, 1–29.

- Dalton, Russell J. (2008). ‘The Quantity and the Quality of Party Systems: Party System Polarization, Its Measurement, and Its Consequences’, Comparative Political Studies, 41:7, 899–920.

- Damgaard, Erik (1969). ‘The Parliamentary Basis of Danish Governments: The Patterns of Coalition Formation’, Scandinavian Political Studies, 4:A4, 30–57.

- Däubler, Thomas (2012). ‘The Preparation and Use of Election Manifestos: Learning from the Irish Case’, Irish Political Studies, 27:1, 51–70.

- de Swaan, Abram (1973). Coalition Theories and Cabinet Formations: A Study of Formal Theories of Coalition Formation Applied to Nine European Parliaments after 1918. Vol. 4 of Progress in Mathematical Social Sciences. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- de Winter, Lieven (1998). ‘A Comparative Analysis of the Electoral, Office and Policy Success of Ethnoregionalist Parties’, in Lieven de Winter and Huri Tursan (eds.), Regionalist Parties in Western Europe. New York: Routledge, 204–47.

- de Winter, Lieven (2002). ‘Parties and Government Formation, Portfolio Allocation and Policy Definition’, in Kurt Richard Luther and Ferdinand Müller-Rommel (eds.), Political Parties in the New Europe: Political and Analytical Challenges. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 171–205.

- de Winter, Lieven, and Patrick Dumont (2008). ‘Uncertainty and Complexity in Cabinet Formation’, in Kaare Strøm, Wolfgang C. Müller, and Torbjörn Bergman (eds.), Cabinets and Coalition Bargaining. The Democratic Life Cycle in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 124–58.

- Dodd, Lawrence C. (1976). Coalitions in Parliamentary Government. Princeton Legacy Library. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Döring, Holger, and Philip Manow (2016). ‘Parliament and Government Composition Database (ParlGov): Information on Parties, Elections and Cabinets in Modern Democracies', Development version.

- Downs, Anthony (1957). ‘An Economic Theory of Political Action in a Democracy’, Journal of Political Economy, 65:2, 135–50.

- Druckman, James N., Lanny W. Martin, and Michael F. Thies (2005). ‘Influence without Confidence: Upper Chambers and Government Formation’, Legislative Studies Quarterly, 30:4, 529–48.

- Ecker, Alejandro, and Thomas M. Meyer (2015). ‘The Duration of Government Formation Processes in Europe’, Research & Politics, 2:4. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168015622796.

- Ecker, Alejandro, and Thomas M. Meyer (2020). ‘Coalition Bargaining Duration in Multiparty Democracies’, British Journal of Political Science, 50:1, 261–80.

- Falcó-Gimeno, Albert (2014). ‘The Use of Control Mechanisms in Coalition Governments’, Party Politics, 20:3, 341–56.

- Falcó-Gimeno, Albert, and Ignacio Jurado (2011). ‘Minority Governments and Budget Deficits: The Role of the Opposition’, European Journal of Political Economy, 27:3, 554–65.

- Field, Bonnie N. (2009). ‘Minority Government and Legislative Politics in a Multilevel State: Spain under Zapatero’, South European Society and Politics, 14:4, 417–34.

- Field, Bonnie N. (2016). Why Minority Governments Work: Multilevel Territorial Politics in Spain. Europe in Transition. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gamson, William A. (1961). ‘A Theory of Coalition Formation’, American Sociological Review, 26:3, 373–82.

- Golder, Sona N. (2010). ‘Bargaining Delays in the Government Formation Process’, Comparative Political Studies, 43:1, 3–32.

- Green-Pedersen, Christoffer (2001). ‘Minority Governments and Party Politics: The Political and Institutional Background to the “Danish Miracle"’, Journal of Public Policy, 21:1, 53–70.

- Green-Pedersen, Christoffer (2006). ‘Long-Term Changes in Danish Party Politics: The Rise and Importance of Issue Competition’, Scandinavian Political Studies, 29:3, 219–35.

- Green-Pedersen, Christoffer, and Asbjørn Skjaeveland (2020). ‘Governments in Action: Consensual Politics and Minority Governments’, in Peter Munk Christiansen, Jørgen Elklit, and Peter Nedergaard (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Danish Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 230–41.

- Green-Pedersen, Christoffer, Peter B. Mortensen, and Gunnar Thesen (2017). ‘The Incumbency Bonus Revisited: Causes and Consequences of Media Dominance’, British Journal of Political Science, 47:1, 131–48.

- Heller, William B. (2002). ‘Regional Parties and National Politics in Europe: Spain’s Estado De Las Autonomias, 1993 to 2000’, Comparative Political Studies, 35:6, 657–85.

- Hellström, Johan, Torbjörn Bergman, and Hanna Bäck (2021). ‘Party Government in Europe Database (PAGED)’, Main sponsor: Riksbankens Jubileumsfond (IN150306:1).

- Hjermitslev, Ida B. (2020). ‘The Electoral Cost of Coalition Participation: Can Anyone Escape?’, Party Politics, 26:4, 510–20.

- Kefford, Glenn, and Liam Weeks (2020). ‘Minority Party Government and Independent MPs: A Comparative Analysis of Australia and Ireland’, Parliamentary Affairs, 73:1, 89–107.

- Kirkpatrick, Evron M. (1971). ‘"Toward a More Responsible Two-Party System”: Political Science, Policy Science, or Pseudo-Science?’, American Political Science Review, 65:4, 965–90.

- Klemmensen, Robert (2005). ‘Forlig i det danske folketing 1953-2001’, Politica, 37:4, 440–52.

- Klingemann, Hans-Dieter, Richard I. Hofferbert, and Ian Budge (1994). Parties, Policies, and Democracy: Theoretical Lenses on Public Policy. Boulder: Westview Press.

- Klüver, Heike, and Jae-Jae Spoon (2016). ‘Who Responds? Voters, Parties and Issue Attention’, British Journal of Political Science, 46:3, 633–54.

- Klüver, Heike, and Jae Jae Spoon (2020). ‘Helping or Hurting? How Governing as a Junior Coalition Partner Influences Electoral Outcomes’, The Journal of Politics, 82:4, 1231–42.

- Krauss, Svenja, and Maria Thürk (2022). ‘Stability of Minority Governments and the Role of Support Agreements’, West European Politics, 45:4, 767–92.

- Laakso, Markku, and Rein Taagepera (1979). ‘"Effective” Number of Parties: A Measure with Application to West Europe’, Comparative Political Studies, 12:1, 3–27.

- Laver, Michael, and Kenneth A. Shepsle (1990). ‘Coalitions and Cabinet Government’, American Political Science Review, 84:3, 873–90.

- Laver, Michael, and Kenneth A. Shepsle (1996). Making and Breaking Governments: Cabinets and Legislatures in Parliamentary Democracies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Laver, Michael, and Norman Schofield (1990). Multiparty Government: The Politics of Coalition in Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lijphart, Arend (1984). Democracies: Patterns of Majoritarian and Consensus Government in Twenty-One Countries. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Lijphart, Arend (1994). Electoral Systems and Party Systems: A Study of Twenty-Seven Democracies, 1945-1990. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lijphart, Arend (1999). Patterns of Democracy: Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Democracies. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Luebbert, Gregory M. (1986). Comparative Democracy: Policymaking and Governing Coalitions in Europe and Israel. Columbia: Columbia University Press.

- Martin, Lanny W., and Georg Vanberg (2003). ‘Wasting Time? The Impact of Ideology and Size on Delay in Coalition Formation’, British Journal of Political Science, 33:02, 323–32.

- Meguid, Bonnie (2008). Party Competition between Unequals: Strategies and Electoral Fortunes in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mitchell, Paul, and Benjamin Nyblade (2008). ‘Government Formation and Cabinet Type in Parliamentary Democracies’, in Kaare Strøm, Wolfgang C. Müller, and Torbjörn Bergman (eds.), Cabinets and Coalition Bargaining. The Democratic Life Cycle in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 201–36.

- Müller, Melanie (2022). ‘Support Party Strategies on Important Policy Issues: Results from Swedish Minority Governments’, Government and Opposition, 1–22.

- Müller, Melanie, and Pascal D. König (2021). ‘Timing in Opposition Party Support under Minority Government’, Scandinavian Political Studies, 44:2, 220–43.

- Müller, Wolfgang C., and Kaare Strøm (2008). ‘Coalition Agreements and Cabinet Governance’, in Kaare Strøm, Wolfgang C. Müller, and Torbjörn Bergman (eds.), Cabinets and Coalition Bargaining. The Democratic Life Cycle in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 159–200.

- Narud, Hanne Marthe, and Henry Valen (2008). ‘Coalition Membership and Electoral Performance’, in Kaare Strøm, Wolfgang C. Müller, and Torbjörn Bergman (eds.), Cabinets and Coalition Bargaining. The Democratic Life Cycle in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 369–402.

- Otjes, Simon, and Tom Louwerse (2013). ‘Een bijzonder meerderheidskabinet? Parlementair gedrag tijdens het kabinet Rutte-I’, Res Publica, 55:4, 459–79.

- Powell, G. Bingham (1982). Contemporary Democracies. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Powell, G. Bingham (2000). Elections as Instruments of Democracy: Majoritarian and Proportional Visions. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Rasch, Bjørn Erik, Shane Martin, and José Antonio Cheibub (2015). Parliaments and Government Formation: Unpacking Investiture Rules. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Riker, William H. (1962). The Theory of Political Coalitions. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Saalfeld, Thomas (2008). ‘Institutions, Chance and Choices: The Dynamics of Cabinet Survival in the Parliamentary Democracies of Western Europe (1945-99)’, in Kaare Strøm, Wolfgang C. Müller, and Torbjörn Bergman (eds.), Cabinets and Coalition Bargaining. The Democratic Life Cycle in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 327–68.

- Sartori, Giovanni (1976). Parties and Party Systems: A Framework for Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sieberer, Ulrich, and Daniel Höhmann (2022). ‘Do Party System Parameters Explain Differences in Legislative Organization? Fragmentation, Polarization, and the Density of Regulation in European Parliaments, 1945–2009’, Party Politics, 28:4, 597–610.

- Sjölin, Mats (1993). Coalition Politics and Parliamentary Power. Lund: Lund University Press

- Strøm, Kaare (1984). ‘Minority Governments in Parliamentary Democracies. The Rationality of Nonwinning Cabinet Solutions’, Comparative Political Studies, 17:2, 199–227.

- Strøm, Kaare (1990a). ‘A Behavioral Theory of Competitive Political Parties’, American Journal of Political Science, 34:2, 565–98.

- Strøm, Kaare (1990b). Minority Governments and Majority Rule. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Strøm, Kaare, Ian Budge, and Michael Laver (1994). ‘Constraints on Cabinet Formation in Parliamentary Democracies’, American Journal of Political Science, 38:2, 303–35.

- Thesen, Gunnar (2016). ‘Win Some, Lose None? Support Parties at the Polls and in Political Agenda–Setting’, Political Studies, 64:4, 979–99.

- Thies, Michael F. (2001). ‘Keeping Tabs on Partners: The Logic of Delegation in Coalition Governments’, American Journal of Political Science, 45:3, 580–98.

- Thürk, Maria (2022). ‘Small in Size but Powerful in Parliament? The Legislative Performance of Minority Governments’, Legislative Studies Quarterly, 47:1, 193–224.

- Thürk, Maria, Johan Hellström, and Holger Döring (2021). ‘Institutional Constraints on Cabinet Formation: Veto Points and Party System Dynamics’, European Journal of Political Research, 60:2, 295–316.

- Tromborg, Mathias Wessel, Randolph T. Stevenson, and David Fortunato (2019). ‘Voters, Responsibility Attribution and Support Parties in Parliamentary Democracies’, British Journal of Political Science, 49:4, 1591–601.

- Tsebelis, George (2002). Veto Players: How Political Institutions Work. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Tsebelis, George, and Jeannette Money (1997). Bicameralism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Volkens, Andrea, Werner Krause, Pola Lehmann, Theres Matthieß, Nicolas Merz, Sven Regel, and Bernhard Weßels (2018). ‘The Manifesto Data Collection. Manifesto Project (MRG/CMP/MARPOR)'. Version 2018b.

- Warwick, Paul V. (1998). ‘Policy Distance and Parliamentary Government’, Legislative Studies Quarterly, 23:3, 319–45.