Abstract

One of the biggest challenges parties in multiparty governments face is making policies together and overcoming the risk of a policy stalemate. Scholars have devoted much attention to the study of how various institutions in cabinet and parliament help coalition parties with conflicting policy preferences to be efficient in the policy-making process. Coalition agreements are one of many instruments coalition partners can use to facilitate policy making. However, many scholars describe such agreements’ actual role as cheap talk, due to their legally non-enforceable nature. Do coalition agreements make a difference in the policy-making productivity of multiparty governments? To address this question, this article focuses on governments’ policy output and investigates whether coalition agreements increase the policy-making productivity of multiparty cabinets. Its central argument is that written agreements between coalition partners strengthen the capacity of coalition governments to make policy reforms, even when there is a high degree of ideological conflict among partners. To evaluate this argument, the article analyzes data on economic reform measures adopted by national governments in 11 Western European countries over a 40-year period (1978–2017), based on a coding of more than 1000 periodical country reports issued by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The results show that while coalition agreements foster policy productivity in minimal winning cabinets, they play a weaker role in minority and surplus governments. Coalition agreements limit the negative effect of intra-cabinet ideological conflict on reform productivity, suggesting that such contracts help parties overcome the risk of policy stalemate.

Coalition governments join together political parties with different, and sometimes conflicting, policy preferences that compete with each other in elections and over government offices. This often results in governments that are politically unstable and find it hard to make policy reforms, leaving the choice between short-liveness and policy stalemate (Bryce Citation1920). Yet, this bleak picture of coalition governance is far from universally applicable. Coalition governments can also be stable, and productive in terms of making policy reforms (Lijphart Citation2012). We very well know that greater preference compatibility between the coalition parties is likely to produce such effects. However, are there institutional mechanisms coalition partners can resort to in order to overcome the challenges associated with incompatible policy preferences and better facilitate the policy-making process?

Scholars studying multiparty governments in parliamentary democracies have highlighted various institutional control and oversight mechanisms, which coalition partners use to mitigate potential agency loss in cabinet and facilitate coalition policy compromises (Müller and Meyer Citation2010). These control and oversight mechanisms, for example, include the appointment of ‘watchdog junior ministers’ (Lipsmeyer and Pierce Citation2011; Thies Citation2001), overlapping policy jurisdictions of ministries (Fernandes et al. Citation2016), cabinet committees and ‘inner cabinets’ (Andeweg and Timmermans Citation2008; Müller and Strøm Citation2000) and strong ‘parliamentary policing institutions’ (Martin and Vanberg Citation2011, Citation2020). Another important mechanism which has been stressed in this literature is the drafting of a coalition policy agreement, or a ‘contract’ between coalition partners, which also has the potential to mitigate agency loss within cabinet (e.g. Klüver and Bäck Citation2019; Müller and Strøm Citation2008). Existing studies have shown that coalition agreements have an impact on cabinet survival (Krauss Citation2018; Saalfeld Citation2008), however few studies have analysed the role of coalition agreements in the policy-making process (Bäck et al. Citation2017; Moury Citation2014; Timmermans Citation1998, Citation2006). The aim of this article is to address this gap.

Here we investigate one potential role of coalition agreements, namely their ability to mitigate one of the main risks in coalition governments – policy stalemate, or low policy-making productivity. We argue that coalition governments that rely on a written coalition agreement are more productive in terms of making policy reforms than those without. We further suggest that the productivity boost of coalition agreements should be more pronounced for minimal winning cabinets and less so for minority and surplus cabinets. We also propose that coalition agreements mitigate the negative effect of ideological conflict between government parties on reform productivity.

We evaluate our theoretical expectations using a data set of coalition agreements and economic reform measures taken in 11 Western European countries (1978–2017), based on a coding of more than 1000 periodical country reports issued by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) and the OECD. Our data set that includes 6664 actual reforms and covers the full life span of 150 coalition cabinets. We find robust empirical support for our hypotheses, revealing that coalition agreements increase reform productivity and mitigate potential hindrances to reform productivity that might result from intra-coalition ideological conflict. Hence, even highly heterogenous cabinets can be productive if they have negotiated a coalition agreement.

Theoretical framework and hypotheses

Challenges to coalition governance and policy making

Governance and policy making in multiparty governments are characterised by several challenges, related to the fact that coalition partners have differing policy preferences and compete at elections separately. This problem is exacerbated by the existence of a jurisdictional system, where cabinets delegate considerable policy making authority to individual ministers and parties in charge of a ministry have a significant advantage in terms of policy-specific resources and gate-keeping powers (Laver and Shepsle Citation1996). As a consequence, in practice, ministers are the only ones who can develop viable policy proposals (Laver and Shepsle Citation1996; Martin and Vanberg Citation2014, Citation2020). Given differing policy preferences between partners, ministers have strong incentives to use this informational advantage to advance their own (party’s) interests in the policy-making process (Bäck et al. Citation2022; Martin and Vanberg Citation2020; Thies Citation2001). According to the principal–agent framework, multiparty cabinets have to deal with problems of ‘ministerial drift’, since individual ministers representing different policy interests are likely to deviate from the agenda of the government as a whole (see e.g. Ecker et al. Citation2023).

That said, ministerial drift can be reined in through monitoring and control mechanisms in cabinet and parliament, lowering the informational advantage of responsible ministers and make it harder for the minister party to misrepresent the policy situation to its advantage (e.g. Bergman et al. Citation2021; Martin and Vanberg Citation2014; Müller and Strøm Citation2000; Strøm et al. Citation2008). At the cabinet level, these for example include, ‘watchdog junior ministers’ (Lipsmeyer and Pierce Citation2011; Thies Citation2001), cabinet committees and ‘inner cabinets’ (Andeweg and Timmermans Citation2008; Müller and Strøm Citation2000). In parliament, committees play a central role in intra cabinet monitoring and oversight (André et al. Citation2016; Bäck et al. Citation2022; Carroll and Cox Citation2012; Harfst and Schnapp Citation2003; Kim and Loewenberg Citation2005; Martin Citation2004; Martin and Vanberg Citation2005, Citation2011, Citation2020; Mattson and Strøm Citation1995; Strøm et al. Citation2010; Zubek Citation2015) – they have different options to gather policy information,Footnote1 which help them balance out informational asymmetries in cabinet and propose feasible alternatives. In addition, depending on the legislative rules, committees can propose bill amendments or directly rewrite ministerial draft bills.

However, the usage of these control and monitoring mechanisms in cabinet and parliament, while effective (Bäck et al. Citation2022; Martin and Vanberg Citation2020), comes with an important cost – time – time which could be used to pass further policies. Thorough investigation of the current policy situation and the subsequent correction of ministerial drift via policy amendments is time consuming. In addition, intra-cabinet ideological conflict increases the costs of potential ministerial drift and thus necessitates thorough oversight checks on policy proposals, which in turn can increase substantively the time spent on deliberation and revision of draft legislation. In support of this theoretical expectation, Martin and Vanberg (Citation2004, Citation2005) show that the legislative process results in more amendments and lasts longer when there is greater ideological conflict between the coalition parties. How can coalition governments use their time more efficiently, yet still overcome problems of ministerial drift? Existing literature suggests that coalition agreements can be used to address intra-cabinet agency loss problems (e.g. Hallerberg et al. Citation2009; Indridason and Kristinsson Citation2013; Klüver and Bäck Citation2019). In contrast to oversight mechanisms used when in office, coalition agreements impose time-costs at the beginning of the legislative term when parties bargain over the content of the contract.

While coalition contracts are negotiated and signed by a majority of coalition governments (Bergman et al. Citation2021; Müller and Strøm Citation2000), strikingly, we know little about their actual role in the policy-making process. Despite the substantive attention devoted to studying coalition agreements, scholars have predominantly focussed on their content and fulfilment rates of party pledges (Naurin et al. Citation2019; Thomson et al. Citation2017). For example, in a study of coalition agreements in four Western European countries, Moury and Timmermans (Citation2013) investigate whether coalition agreements include deals over policy issues that the governing parties do not agree on (see also Moury Citation2011). Only recently, do we see a shift of the scholarly focus more towards finding empirical evidence which reveal whether coalition agreements can mitigate intra-cabinet problems. Bäck et al. (Citation2017) for example, investigate the role of coalition agreements in solving ‘common pool problems’ taking the example of budgetary spending. They find that coalition agreements significantly reduce the negative effect of government fragmentation on public spending, albeit only in institutional contexts where prime ministerial power is low. In this article, we aim to contribute to this literature by focussing on the role of coalition agreements in overcoming one of the main risks in coalition governments – policy stalemate and investigating their capacity to facilitate government policy productivity or not.

How can coalition agreements facilitate policy productivity?

While Laver and Schofield (Citation1990: 189) suggest that coalition agreements are ‘little more than window dressing’ and Timmermans (Citation1998: 419) highlights their symbolic function, writing and negotiating coalition agreements is a costly endeavour. The costs associated with crafting a written agreement can be thought of as an investment in the functioning of the coalition. Here, we investigate whether this investment pays off in terms of greater policy output over the duration of the cabinet. In particular, we are interested in answering the question whether coalition agreements facilitate government policy productivity.

Bargaining over a coalition agreement is a central part of the government formation process (Peterson and De Ridder Citation1986). The negotiation over policy before government formation as compared to during the legislative period after the government has formed is substantively different (Andeweg et al. Citation2011; Bergman et al. Citation2021; Müller and Strøm Citation1999, Citation2000). These differences relate to (1) which political actors participate, (2) their goals and motivations and (3) the distribution of responsibility for policy concessions. Below, we suggest that the specific set up of coalition agreement negotiations helps forging inter-party agreement on government policies, which subsequently should lead to policy-productivity gains of governments during the legislative term. We also note that the public nature of coalition agreements increases the costs of reneging on these agreements and facilitates coalition partners’ commitment to it.

The key actors in government formation negotiations are the grandees of the parties rather than cabinet ministers and specialised members of parliament (MPs). Although some politicians may anticipate a minister role for themselves in the yet to form government, at the time of the bargaining, none is in a position similar to that of an acting minister when it comes to influencing policy content. While party leaders who engage in the coalition formation process also draw on their parties’ policy experts to conduct detailed policy negotiations, they remain in control of the process, and it is up to them to strike the final deal. Compared to the policy making of an already installed coalition government, decision making in the formation situation is thus delegated upwards.

The fact that party grandees are the central actors in the government formation process has substantive implications for the policy deals which are agreed upon in the government formation arena (Peterson and De Ridder Citation1986). Party leaders have the overarching goal of ensuring their own party’s government participation rather than anchoring specific policy choices in the coalition agreement. Thus, at the formation stage, they are willing to trade policy concessions for government participation and favourable cabinet posts. If policy concessions are required for sealing the coalition deal, party leaders weigh them against all the benefits of government participation – the policy concessions won and all the positions which come under the party’s appointment power. Having the whole package at stake should make it easier to overcome inter-party differences on specific policies in government formation situations.

Policy compromises are more easily forged at the government formation stage for two main reasons – low immediate costs and high immediate benefits. First, potential electoral costs for policy concessions are low or discounted because of the long time period until the next general elections when such concessions might be punished if voters remember these.Footnote2 Second, the rewards from these policy agreements are high, because they pave the way to government participation and, with it, direct policy influence. In addition, the inclusion of policy deals in the coalition agreements, increases the probability of their successful enactment during the legislative term (Schermann and Ennser-Jedenastik Citation2014).

Further, the very nature of negotiating an entire policy program, rather than individual measures or policies, allows for logrolling within and beyond policy areas. In contrast, during the legislative term, issues emerge one-by-one, which increases the uncertainty of ad hoc policy deals. First movers in a logroll – those who fulfil their part of the deal first – run the risk of their logrolling partners to renege on the deal, pointing to unforeseen new circumstances and difficulties. Without institutional mechanisms, which foster partisan commitment to negotiated logrolls (e.g. a publicly revealed coalition agreement), concerns about uncertainty and reneged deals might deem logroll agreements during the legislative terms less feasible, more time-consuming and thus less attractive. One exception would be simultaneous logrolls, which require tit-for-tat-policies to be enacted at the same time or be a condition for each other. In contrast, negotiating various policies as one deal within the coalition agreement, opens avenues for logrolling over different issue areas and issues which may appear on the government agenda with considerable time difference. Their passage during the legislative term can be fostered by the associated audience and reputation costs of reneging on the publicly agreed deals included in the written agreement.

Finally, there are important differences in terms of responsibility attribution for the policy concessions between negotiating an entire coalition deal and making individual decisions in a sitting government. Concessions made to coalition partners in the government formation process are collective decisions of the party and will not be attributed to individual politicians to the same extent as concessions made by ministers in a sitting coalition. Diffusion of responsibility for policy concessions among the party elite is thus another favourable condition for agreeing on a substantive policy program in the bargaining arena of coalition formation.

In addition, formalising the bargaining results in a written coalition agreement with a substantive policy program can help avoiding conflicting interpretations of what had been agreed once the coalition cabinet has taken office and works on realising the coalition program. Of course, putting the policy agreement in written form does not prevent all such difficulties in actual policy making. Like business contracts and constitutions, coalition agreements are incomplete contracts. Unforeseen contingencies will not be covered. Even when negotiators can envision the challenges ahead, writing complete contract clauses may simply be too costly (Müller and Strøm Citation2008). Political actors may use contractual fuzziness for self-serving interpretation of the agreement later on. Yet even in that case, the agreements’ provisions remain a ‘reference point’ for actual solutions (Hart and Moore Citation2008). While parties may have difficulties getting policy outcomes outside the contract, they may feel entitled to different outcomes within the contract, with each party pursuing for itself the best outcome permitted by the contract (Fehr et al. Citation2011; Frydlinger and Hart Citation2023; Hart and Moore Citation2008). Therefore, by providing a reference point, policy provisions in coalition agreements can bridge the gap between conflicting policy positions of government parties even in the face of uncertainty.

Above we discussed how coalition agreements can facilitate successful policy making during the legislative term. All of these reasons hinge on one central assumption – that coalition partners will commit to the coalition agreement and will not defect from the agreed upon policy compromises included in the agreement. What reigns in coalition partners into commitment, given that coalition agreements do not have legal status and therefore no national court has the authority to enforce it upon the participating parties?

We suggest that the institutional mechanism which has the potential to enforce partisan commitment to the coalition agreement is the public status of the agreement. Eichorst (Citation2014: 98) suggests that the public nature of coalition agreements gives them a ‘contract-like’ status, which ties ministers’ hands through reputational concerns (Bäck et al. Citation2017).Footnote3 Building a reputation of an unreliable coalition partner, might make it more difficult for a party to be included in future coalitions and thus introduces long-term policy or office losses. Furthermore, given that the full coalition agreement with all included policy compromises is revealed to the public, any reneging on a policy agreement runs the risk to be uncovered. The publicity of coalition agreements allows party activists, the media, and the opposition to use the agreement as a yardstick by which to compare the activities of an incumbent government (Thomson Citation2011). Such scrutiny serves as a sort of ‘fire alarm’ mechanism (McCubbins and Schwartz Citation1984), bringing to light deviations from the policy commitments of the coalition agreement by one coalition partner. In effect, this mechanism should encourage coalition partners to honour the signed coalition contract – at least in times when government partners value their government participation and deem future collaborations desirable. As opposed to governments that lack such an accountability mechanism, it is in mutual interest of all partners to implement the policy agreements contained in the coalition agreement. Consequently, a coalition agreement with a substantial policy program should increase a government’s policy-making productivity. We therefore expect that,

H1: The presence of a coalition agreement increases the policy productivity of coalition governments.

Under which circumstances do coalition agreements facilitate policy productivity?

The degree to which coalition agreements can facilitate a high policy-making productivity hinges on the feasibility of the policy compromises and the costs of defecting from such compromises. We suggest that the differentiation between government types – minority coalition, minimal winning coalition, and surplus coalition – is helpful to capture these aspects.

One central aspect related to the feasibility of policy compromises is the existence of a parliamentary majority in favour of the policy agreement. While it is difficult to evaluate the content of coalition contracts in terms of acceptability to a parliamentary majority, we know whether a government enjoys a majority status. We therefore suggest, that a minority coalition might not be able to reap the productivity gains that a coalition agreement offers. Although coalition partners in a minority cabinet might have agreed on some policy compromises and included these together with logrolling deals in the coalition agreement, the passage of these policies in parliament might plainly fail or become overly costly because everything a minority government wants to enact needs to get the support of some of the opposition parties.

Even if minority governments consist of parties that are centrally located and enjoy a privileged ideological position where they can play the opposition parties against each other (Laver and Schofield Citation1990; Tsebelis Citation2002), government parties still need to win over opposition parties on a bill-by-bill basis. An additional complication of such a scenario of a centrally located minority government, is that the opposition parties willing to support government policies might diverge from one policy to another. This requires considerable political effort and is likely to expend much of the government’s time in office, reducing overall productivity. Further, the support of opposition parties for minority government policies is volatile and depends on the circumstances. Under unfavourable electoral prospects and better outside options, opposition parties can withhold support from the government, causing policy stalemate.

Coalition parties can also include policies desired by opposition parties in their coalition agreements to gain the respective opposition parties’ support. Lengthier coalition agreements of minority governments (Indridason and Kristinsson Citation2013) suggest that this might be often the case. However, different policies might require the support of different opposition parties, whose support then depends upon their outside options at the time of bill deliberation. This complication renders the inclusion of policy commitments towards specific opposition parties in the agreement not only costly, but also difficult. We thus expect heterogeneous effects of coalition agreements on governmental policy productivity, with minority cabinets receiving less of a productivity boost from coalition agreements than majority cabinets.

We have a similar expectation for surplus governments. This type of government seems the most heterogeneous of the three and therefore the least understood. Accordingly, our discussion here is more tentative. By definition, surplus coalitions include at least one party that is not necessary for a parliamentary majority. Practically, this implies, that such coalitions include parties that can bring down the cabinet and others that cannot. Reaching agreement between the parties that are critical to the formation and the survival of the government therefore should be the top priority in negotiating the coalition deal and agreement. Given that a surplus party is not necessary for the government to form, effectively, it has little bargaining power during the government formation stage to push for specific policies to be included in the coalition agreement. Furthermore, given the time constraints under which such bargains are made, the consent of surplus parties is likely to be more of a passive nature. Sometimes they become part of the bargain only after the parties providing the government majority have agreed. In such instances, they may be presented already with a draft agreement that shall not be altered much by bringing on board additional partners. Due to their limited bargaining power, surplus parties then cannot require fundamental changes of the agreement that would affect vital interests of the major parties.Footnote4

However, paying less attention to the policy preferences of the surplus parties during the government formation stage, might backfire during the legislative term. One factor that is likely to shift power towards a surplus party during a government’s term in office is ministerial responsibility for particular policies (Bäck et al. Citation2022; Laver and Shepsle Citation1996; Martin and Vanberg Citation2020). Ministers from surplus parties enjoy about the same advantages in terms of formulating draft legislation and agenda control in their respective jurisdictions as their ministerial colleagues from the more powerful parties have for theirs. Ministers from surplus parties can use these powers to delay and modify policies included in the coalition agreement and to introduce proposals not contained therein according to their own preferences. Such attempts at modifying the coalition agreement in its implementation process, in turn, may require a greater amount of coordination and bargaining with the other parties to arrive at bills the cabinet and the parliamentary majority are willing to enact. In other words, the transaction and deliberation costs (e.g. time) within the coalition increase (Lupia and Strøm Citation2008), and the government’s policy-productivity may be reduced.

We expect a similar logic to unfold when changes in the government’s political environment cause shifts of the relative bargaining power of the individual parties (Laver and Shepsle Citation1998; Lupia and Strøm Citation1995). Although surplus parties remain technically not necessary for a parliamentary majority and thus are not required to pass legislation, such parties are included in the cabinet for good reasons (Crombez Citation1996; Laver and Schofield Citation1990: 81–87; Luebbert Citation1986; Volden and Carrubba Citation2004). Concerned about future policies, parties might include surplus parties because they have been reliable coalition partners in the past and may be required again in the future (Carrubba and Volden Citation2000; Hinckley Citation1981: 66–7). Another reason for their inclusion could be to tame the conflict of interest among government parties (Axelrod Citation1970; Bassi Citation2017), or to guarantee bill passage, and with it the survival of the cabinet in the instances when partisan discipline is low (see Carrubba and Volden Citation2000; Laver and Schofield Citation1990; Volden and Carrubba Citation2004). Any of these considerations can gain momentum during a government’s life-time due to external shocks. Such shocks may impose challenging issues on the government’s agenda which make it harder for the major antipodes in the government to agree and to rally their MPs behind the government. All of this may undermine the electoral prospects of the government parties. Under such conditions, support by surplus parties becomes more valuable. In turn, these parties get their grip on a new bargaining chip which they can use to introduce modifications to coalition agreement policies.

Given these complexities of the policy-making process in surplus majority cabinets, why would the government parties holding a majority not consider the policy preferences of the surplus party in the coalition agreements in the first place? We suggest that, due to uncertainty, parties holding a parliamentary majority at the government formation stage cannot anticipate when and for which policies surplus parties might enjoy bargaining power and demand adjustments. Incorporating the wishes of the surplus parties in the coalition agreement proportionally might be costly and mechanically unnecessary for the passage of legislation. Therefore, surplus cabinets might be better off to confine the input of surplus parties during the government formation stage and instead act upon any surplus parties’ policy demands on a bill-by-bill basis when the surplus parties happen to hold a bargaining chip during the legislative term. This, of course, suggests that coalition agreements negotiated by surplus coalitions might not be as effective for reform productivity as the coalition agreements of minimal winning cabinets.

Given the above discussion about the three government types, we present a conditional hypothesis, suggesting that it is mainly minimal winning governments that should benefit from a coalition agreement in the policy-making process. We thus hypothesise that,

H2: The presence of a coalition agreement increases policy productivity more strongly for minimal winning cabinets as compared to minority or surplus governments.

An up-front comprehensive policy deal fixed in a coalition agreement seems particularly valuable when the coalition parties’ policy positions are conflicting. In such instances, finding ad hoc agreement in the policy-making process is often difficult. We suggest that coalition agreements can mitigate the negative effect of intra-cabinet conflict and help achieve greater policy productivity even under such circumstances. A coalition agreement is likely to curb uncertainties associated with what lies ahead, which may reduce the potential for stalemate in government decision processes (Moury and Timmermans Citation2013: 56; Timmermans Citation2006: 265). Further, a detailed policy agenda should limit shirking or ministerial drift in contested areas (Klüver and Bäck Citation2019). In addition, sealed policy deals in coalition agreements should reduce the danger of parties’ backbench rebellions as these policy concessions are seen as integral part of a bigger deal (Williams Citation2011). Finally, early concessions before the start of a government term should face less future electoral costs than when made ad hoc during the term and closer to an election. We thus hypothesise that:

H3: The presence of a coalition agreement mitigates the negative effect of ideological conflict within cabinets on policy productivity.

Methods and data

Measuring economic reform productivity

In our analyses we focus on economic reform measures – regulatory, labour, welfare and taxation measures changing the status quo. These policies relate to the core of the classic left–right dimension and have generally continued to be the most important concerns in party competition in post-war Europe (e.g. Dalton et al. Citation2011; Martin and Vanberg Citation2014). Furthermore, recent work has identified that ‘welfare’ and ‘economy’ topics are jointly as common as all other substantive topics within coalition agreements (Klüver and Bäck Citation2019). In addition to the substantive importance of the selected economic policy dimension, there are pragmatic grounds to focus on it – as here we find authoritative sources that centrally report national economic policy reforms in a largely standardised format and over a long time period.

In order to measure actual policy output of governments, we manually coded more than 1000 periodical country reports issued on a quarterly basis by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) and (bi)yearly by the OECD on 11 Western European countries for a period of 40 years (1978–2017) identifying reform measures in the areas of state ownership and regulation, taxation, labour, and social policy – to which we refer to as ‘economic policy’ in the present article. The reform data analysed here includes more than 6600 specific reform measures made by 150 coalition governments in Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal and Sweden.

The EIU reports contain information on recent economic and political developments and provide a review of the most important reform efforts and socio-economic changes in a given country. They offer reliable and comprehensive information about concrete policy changes invoked by the government in a given country to potential business investors, international organisations, government agencies, and academic institutes. EIU reports are prepared by country experts with deep knowledge of the reform processes and policy developments in a given country using various information channels, such as official statements, media reports, and direct contact with government officials. To cross-validate the coverage of the EIU country reports, we also coded more than 200 OECD country reports issued annually or biannually.

We code policy measures that change the policy status quo and were adopted, either by laws or decrees, through actions of the national government. Every reform measure is coded individually, even if they occur in packages (see Wenzelburger et al. (Citation2020) for a similar approach). We consider only concrete measures which contain information on a policy that is altered resulting in some change from a policy status quo. For example, ‘power companies, now operating under a regulated system of licences, will have to open their lines to other suppliers’ (EIU Citation1992). In contrast, we do not code descriptive or vague phrases such as ‘The Austrian schilling became the ninth currency in the Exchange Rate Mechanism’, as these do not contain information about a specific action that the government employed to prepare its capital market for such integration. To illustrate our coding decisions, consider the following example taken from an EIU report on Portugal:

After years of operating with antiquated rules and practices, a degree of reform has at last come to the Portuguese stock markets. The minister of finance, Miguel Cadilhe, introduced a package of reforms in May which have won official approval. The main elements are […] (EIU Citation1988: 19)

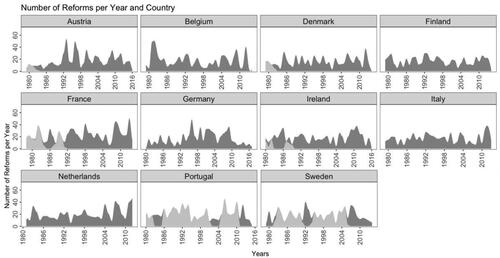

presents the number of reform measures, aggregated into a yearly measure for coalition governments. Years of non-coalition government (excluded from analysis) are shaded light. Overlaps between the curves indicate instances where in a given year a single party government was replaced by a coalition government and vice versa – we consider only the coalition governments and their reform productivity in these years. For example, in 1982 the single-party Danish Jørgensen cabinet was succeeded by a coalition led by Poul Schlüter.

There is considerable variation in the number of reforms across countries and years. Some countries make more reforms than others. For example, Germany and Austria are highly productive and regularly have more than 20 reform measures per year, whereas countries such as Denmark and Finland are less productive. Additionally, we see no general time trends in the amount of reform measures introduced in each country, with even the European financial crisis after 2008 not causing a particular spike in reform productivity. In our subsequent analysis, we use the number of reform measures per cabinet as our dependent variable.

Measuring our independent variables

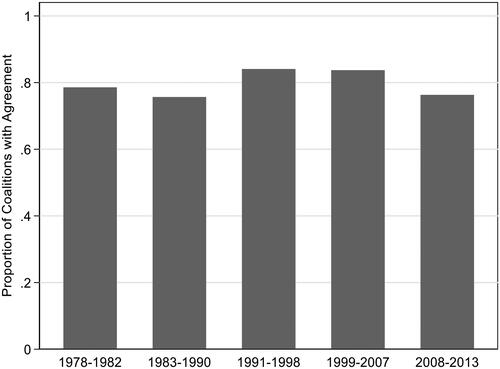

For information related to the bargaining environment and coalition agreements, we rely on the Coalition Governments in Western Europe dataset (Bergman et al. Citation2021). This dataset provides detailed information on important aspects of government formation, coalition governance, and government termination. One of our main independent variables draws on this data set and measures whether there was a written and public coalition agreement presented when the government formed (Agreement). displays the proportion of coalition government cases with a coalition agreement over the timeframe of our sample. While we can observe an uptick in the 1990s and early 2000s in the prevalence of coalition agreements, for those coalitions that began after the start of the financial crisis, the prevalence of such agreements returned to pre-1990 levels.

Another important explanatory variable that we draw from the Coalition Governments in Western Europe dataset is one indicating if a government was a minority, minimal winning, or surplus coalition. From this dataset we also use cabinet duration, which we include as a control variable, to take into account that longer lasting cabinets have more time to pass a larger amount of reform measures.

The aim of this article is to investigate the role of coalition agreements on the reform productivity of coalition governments. We acknowledge that coalition agreements are not randomly assigned to cabinets and instead follow a selection process. While some governments actively decide to write and are able to negotiate and seal a coalition agreement, others do not. It is thus possible that various factors can lead to both – governments to decide and to succeed in writing a coalition agreement and at the same can lead to higher policy productivity. Given the nature of our research question, a randomised control trial where coalition agreements are assigned randomly to cabinets is out of question. Inevitably, relying on observational as opposed to experimental data caries the risk of selection bias. Nevertheless, while we cannot completely rule out the existence of factors which might be confounding to any observed association between coalition agreements and reform productivity, we can increase the internal validity of our analyses by controlling for various potential confounding variables.

An important confounding variable is the nature of intra-coalition relations. Some coalitions might be more capable of making policies and at the same time might be more willing to sign a coalition agreement. There might be many aspects in the nature of intra-coalition relations which could influence both decisions. We know from existing literature that ideological conflict might influence the decision to sign a coalition agreement (see Bowler et al. Citation2016; Eichorst Citation2014; Indridason and Kristinsson Citation2013) and at the same time has been shown to have direct impact on policy output (see Angelova et al. Citation2018; Conley and Bekafigo Citation2010; Tsebelis Citation1999). In addition, we also know that ideological conflict within the cabinet is instrumental for other partisan decisions, including with whom to build a government and how often, as well as with whom to enter into a pre-electoral coalition, which by themselves might also be consequential to writing a coalition agreement and passing policies. In this sense, for our analyses, we take intra-cabinet ideological conflict as a proxy for such partisan decisions (e.g. pre-electoral coalitions and past coalition participation experience).

In line with previous scholars examining ideological conflict within coalition cabinets (Eichorst Citation2014), we match the parties identified as being members of a government with their positions using party manifesto data provided by MARPOR (formerly CMP; Volkens et al. Citation2017). We apply the dimensional and logarithmic scaling approach suggested by Lowe et al. (Citation2011) to create an overall left–right ‘state involvement in the economy’ position of the parties. We then create a measure of Ideological Conflict which captures the absolute distance between the two most extreme parties in the cabinet.

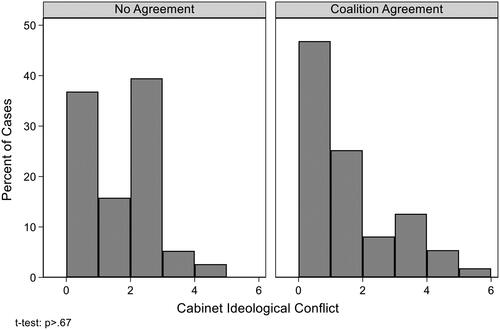

displays the distribution of ideological conflict for coalition cabinets with and without a coalition agreement. The mean value for cabinets without and with a coalition agreement is 1.71 and 1.60, respectively. The distribution of both also has a positive skew indicating a greater concentration of coalitions with lower, rather than higher, levels of ideological disagreement. A t-test indicates that there is no statistically significant difference in the ideological conflict between cabinets with and without a coalition agreement.

Another potential confounding variable is related to the contemporary policy-making context in the country, more specifically, the demand for reforms. Stronger demand for reforms due to demographic changes or economic crises can raise the stakes and influence the motivation of governments to sign a coalition agreement, which would ensure these issues are put on the government agenda and increase the probability of actually passing these. The same policy demand can also pressure the government during the legislative term to pass more policies which tackle the problems at hand, so as to appear responsive to dynamic economic conditions. To capture the demand for policy change, we include various economic factorsFootnote5 – calculated as averages over the cabinet termFootnote6: (1) unemployment rate, (2) percentage of elderly population (over 65), (3) GDP growth and (4) inflation rate. Here we expect that greater proportions of the unemployed and elderly should put financial pressure on regimes resulting in more social or labour policies which accommodate for this (Pierson Citation2001). Relatedly, GDP growth directly impacts a government’s taxation revenues, while recessions might produce conditions favouring Keynesian demand management through increased government spending or subsidisation of labour or business.

Empirical analysis

Here we present analyses using multi-level negative binomial count regression models with errors clustered and random coefficients by country. The dependent variable is the total number of economic reform measures per cabinet. Ordinary least squares regression is not suited for such analysis as such count data violates several assumptions: the data is not continuous – it is discrete, the dependent variable is not normally distributed, and its values are inherently truncated at zero (Beck and Tolnay Citation1995). Negative binomial models are suitable for over-dispersed count data, meaning that the conditional variance exceeds the conditional mean, which is true for all of our models as indicated by the alpha coefficient in .

Table 1. The impact of coalition agreements on reform productivity.

As cabinets are nested within countries, we are concerned with country-level heterogeneity, where some countries might tend to pass a greater number of reforms than others, as well as have a tradition of signing coalition agreements. For example, country-specific characteristics in the design of their social policy, use of VAT, or the availability of industries to privatise are factors that might produce a higher or lower potential for policy reform that cannot be captured by variables included in the models. Countries also vary in their usage of formal written coalition agreements. This heterogeneity could present analytical issues that would impinge one’s ability to disentangle the effect of our key independent variables from these country-level confounders. The use of hierarchical models provides a solution to the aforementioned issues as they can account for differences in the country-level means and differences in the country-level data generation process (Feller and Gelman Citation2015). Interpreting coefficients in a partially-pooledFootnote7 manner provides support that we are not just capturing effects between countries (i.e. countries that tend to have a greater number of reforms also tend to have more frequent coalition agreements), but also within them (i.e. ceteris paribus a coalition with an agreement as compared to one without an agreement). We also employ clustered errors to account for country-level heterogeneity in reform productivity.

In our regression output tables, we use incident rate ratios, which can be interpreted as the percent increase in counts should a cabinet have a given dichotomous feature or should a continuous variable increase by one. As such, coefficients greater than 1 indicate a greater number of reforms while coefficients smaller than 1 indicate fewer reforms. For example, as shown on , a cabinet that has 1% greater GDP growth than the country average (as per the country-effects) would be expected to have passed 7% {1 − 0.929} fewer reforms. Countries experiencing economic crises (lower GDP growth or higher unemployment) would be expected to have a greater number of reforms. Similarly, for each day in office, a cabinet is expected to produce 0.1% more reforms.

Our first hypothesis suggests that coalitions that have negotiated a policy agreement should be more productive than those without. Model 1 in indicates that, controlling for various potential confounders like intra-cabinet conflict and policy demand (unemployment level, GDP growth, elderly population), governments with coalition agreements can be expected to have 22% more reforms than those that do not have such an agreement.

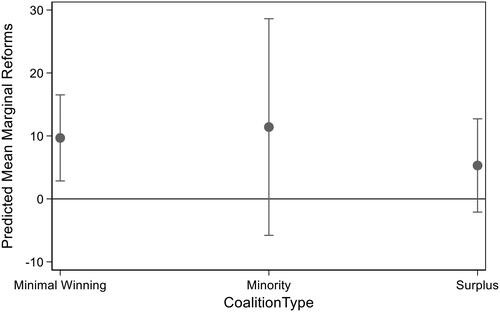

presents the substantive difference that a coalition agreement would make distinguished by cabinet type using the estimates from Model 2 in .Footnote8 Our models suggest that for minimal winning coalitions the benefit of having an agreement equates to approximately 10 additional reforms.Footnote9 With the mean number of reforms per cabinet in our sample having 45 reforms, this is a substantively important amount. Minority and surplus government productivity also tend to be greater with the presence of a coalition agreement. While individually, these are not significant due to wider confidence intervals than those for minimal winning coalitions, jointly, non-minimal winning coalitions with coalition agreements are also estimated to have approximately 10 additional reforms should they conclude a coalition agreement.

Our third hypothesis suggests that coalition agreements are particularly important in their ability to manage intra-coalition ideological conflict. To evaluate this hypothesis, we interact the presence of coalition agreement with the ideological conflict variable among cabinet types. Model 3 in displays these estimates.

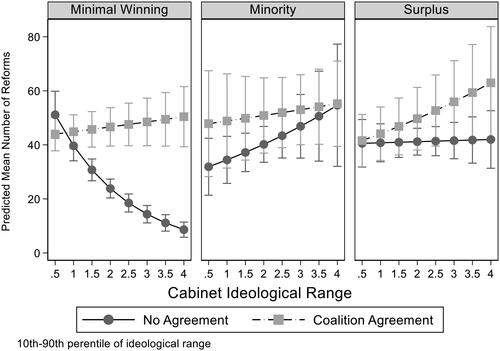

We depict the interaction effect of the presence of a coalition agreement and government type across the ideological range of cabinets in . Here, using the model 3 estimates, we are predicting the number of reforms per cabinet type over the central 10th–90th percentiles of ideological conflict in cabinets. The difference in output between minimal winning cabinets (left panel) with an agreement (in squares and dotted line) and those without (in circles and solid line) increases as the conflict increases. There is little variation in the predicted number of reforms for minimal winning cabinets with coalition agreements, with each averaging between 40 and 50 reforms. However, we can see that ideological conflict does indeed impede policy productivity in minimal winning cabinets without agreements. Note the decrease from 50 predicted reforms for cabinets with little conflict down to 10 for cabinets with high levels of ideological conflict.

A similar pattern can be noted in examining surplus cabinets (right panel). While ideological conflict has no impact on the productivity of surplus cabinets without an agreement, for highly divided cabinets, an agreement is associated with greater reform productivity, perhaps providing evidence of logrolling between coalition members. We see no notable impact of ideological range or the presence of a coalition agreement for minority cabinets (middle panel) in this interactive model. While an upward trend is visually present, neither of these trends are statistically significant.

The marginal effects of the presence of a coalition agreement are depicted in online appendix Figure A1. The estimates substantiate indicating that minority coalitions of all types are unable to benefit from the presence of a coalition agreement. This is potentially indicative of their need for additional agreements with parties outside the coalition for successful passage of policy. In other words, just because a minority coalition has been able to work through its internal conflicts with a coalition agreement, this is not sufficient for greater productivity. These results stand in strong contrast to the effects for minimal winning cabinets. Without an agreement, as ideological conflict in minimal winning cabinet increases, they are expected to have fewer reforms. In that manner, the impact of an agreement on economic policy output becomes more substantive as ideological conflict within a minimal winning cabinet increases, though does not necessarily lead to a substantively greater number of reforms than a similar cabinet with less ideological disagreement. Though not clearly visible in , Figure A1 in the online appendix also demonstrates that, like minimal winning cabinets, surplus cabinets also have a statistically significant benefit of a coalition agreement, though the size of this effect is notably less than that for minimum winning cabinets. These results are in line with the hypotheses we have advanced in this article.

While we hypothesise that the process of making the coalition agreement is key to the resulting productivity gains, we can also evaluate some of the more specific mechanisms that might be at work by restricting analysis to those cases with an agreement and identifying key areas on which they might differ using other variables in the Bergman et al. (Citation2021) dataset. In online appendix Table A1e, we use the length of the agreement as the key independent variable to explain governmental reform productivity. The general expectation here is that lengthier coalition agreements contain either more reforms or more detail, both of which should facilitate policy productivity. An average agreement has a length of around 15,000 words with a standard deviation also of that length. Our regression analyses suggest that increasing the length of an agreement by one standard deviation would result in a 7% greater reform productivity. Given the reduced sample size used for this analysis, this variable does not reach standard levels of significance. However, if we include the full sample, setting the length variable in cabinets without an agreement to zero, we estimate a significant difference of a 10% greater reform productivity for a one standard deviation increase in word count. Evidence of interaction effects is not as visible, although we make no prediction that the length would have a differing impact based on the type of coalition or ideological range.

Another feature that is included in the Bergman et al. (Citation2021) dataset is the policy comprehensiveness of the agreement (categories: no agreement, few selected policy issues, a variety of policy issues, comprehensive policy platform). We analyse the impact of this variable in online appendix Table A1f. For each greater level of comprehensiveness, 21% more reforms are predicted, though again, in the reduced sample this is not significant. If one were to code those lacking an agreement as having no comprehensive agreement, the variable does become significant at the 0.1 level predicting 15% more reforms for each level increase of comprehensiveness. Evidence on interaction effects is again not visible. There is also the possibly to examine whether the percentage of policy statements contained in a coalition agreement would affect productivity. However, a majority of coalition agreements consist of 98% or more policy statements. Only 15% of the agreements consist of fewer than 90% of policy statements. We find no significant effect of this variable on reform productivity, but with such limited variation on this key variable, it would be quite difficult to do so.

Conclusions

In this article we have investigated the role of a widely adapted instrument of coalition governance – written coalition agreements. Earlier research has shown that such agreements are associated with cabinets of greater longevity (Krauss Citation2018; Saalfeld Citation2008), but very few scholars have analysed their impact on government policy making. Innovatively, the current article has investigated whether and when such agreements can increase the reform productivity of coalition governments. We argued that the presence of a coalition agreement will increase reform productivity of majority cabinets, and should mitigate negative effects that ideological conflict within the coalition has on the cabinet’s policy productivity.

We evaluated these expectations with original data on 6664 reform measures (extracted from the country reports of the EIU and the OECD) by coalition governments in 11 Western European countries over a 40-year period ranging from 1978 until 2017. We find that coalition governments with a written and publicly announced policy agreement have a statistically significant and substantively important advantage in reform productivity over coalitions without such contracts. We also find that the presence of a coalition agreement can largely compensate for increasing problems to pass reforms that come from a greater ideological conflict for majority cabinets. Collectively, these results underline the importance of carefully negotiated agreements for coalition governments’ reform productivity. Coalitions are not doomed to fail in making socio-economic reforms and coalition agreements do matter for the policy-making process. In particular, such written and public contracts between partners help mitigate one of the central risks associated with coalition governments – policy stalemate.

Given that our analyses rely on observational data, the above findings should be interpreted with caution. While we included several potential confounding variables – intra-cabinet conflict and various indicators for policy demand, which we believe increase the internal validity of the found positive relationship between coalition agreements and reform productivity – we acknowledge that we cannot rule out the existence of other observable and not observable confounding variables. We thus emphasise the necessity to investigate the impact of coalition agreements on policy productivity focussing on other observable implications which could provide additional empirical evidence for the suggested relationship.

Our theoretical arguments present various observable implications which could be tested in future research. For example, we suggest, that parties benefit from coalition agreements, because the policy concessions included in these are collective decisions of the party and will not be attributed to individual politicians as compared to a scenario where policy concession are negotiated during the legislative term and specific parties and ministers are leading and therefore visible to the public in the policy making process. If this is one of the mechanisms which facilitates the inclusion of more policy concessions in coalition agreements, and consequently leads to more policy productivity during the term we should find the following: First, countries with electoral systems where individual politicians, as opposed to parties, are held accountable at elections (e.g. open vs. closed proportional electoral systems) should have more detailed coalition agreements and include more policy concessions; second, we should observe that individual politicians from government parties are punished less by voters (e.g. through popularity or competence ratings) when there is a coalition agreement vs. when there is no coalition agreement. According to this logic, individual politicians should also face more favourable ratings when there are more policy concessions included in a coalition agreement rather than making these concessions while the government is in office.

Further, we also suggest that the enforceability of coalition agreements lies in their public nature and the associated audience and reputation costs. Here we expect that parties are interested in complying with the policy concessions in the coalition agreement to avoid reputational costs and keep their prospects to be included as a coalition partner in future governments. If this mechanism is at work, then we should find that parties with better outside options and better government prospects defect more often from the policy compromises included in the coalition agreements. Coalition agreements might not facilitate reform productivity in such instances. We hope our findings will encourage scholars to test such additional observable implications of our theoretical argument.

We also suggest other avenues for future research. As of today our understanding of what happens in the bargaining process of coalition agreements and intra-cabinet decisions is based largely on qualitative evidence. Unravelling such processes more deeply and ideally coming up with indicators for quantitative analyses is also a desirable step forward. Another lies in the content of coalition agreements. While this study was agnostic to the specifics contained within policy agreements, a fruitful extension would be to tie the specific content of coalition agreements to subsequent reforms and reform productivity. This nuanced view could give us a better understanding of how coalition agreements mitigate agency losses and facilitate policy productivity. Another avenue for future research includes a move from socio-economic reforms – where the ultimate reform goals, such as economic growth and high employment, often are agreed upon by the parties – to socio-cultural reforms, which may be contested more fundamentally. While we focussed on coalition agreements – one instrument coalition governments might use to facilitate the policy-making process – coalition governments have an arsenal of other control and oversight mechanisms at their disposal. In order to understand better the role of coalition agreements and their efficacy in different institutional setups, we believe it is worthwhile to move away from evaluating individual instruments of coalition governance to studying their effects, taking into account the overall design of coalition governance (Ecker et al. Citation2023).

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (808.7 KB)Acknowledgements

A previous version of this paper was presented at the ‘Coalition Dynamics: Advances in the Study of the Coalition Life-Cycle’ workshop held at the University of Vienna in November 2021. The authors thank those participants for their assistance in framing the paper’s contributions and Gerard Breeman, who served as discussant. The editors of the journal and two anonymous reviewers are also thanked for their careful reading of an earlier version of this manuscript. Financial support has been provided by the (FWF) Austrian Science Fund (project number: I 3793-G27).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Matthew E. Bergman

Matthew E. Bergman is a Post-Doctoral Researcher at the University of Vienna affiliated with the Department of Government and SFB 884 ‘Political Economy of Reforms’. He has lectured on the topics of comparative politics, research methods, political economy, legal reasoning, and policy analysis. He served as the founding Director of the Krinsk-Houston Law and Politics Initiative at University of California, San Diego until 2020. Among others, his work can be found in Electoral Studies, Political Studies, Politics, Political Studies Review, and Representation. [[email protected]]

Mariyana Angelova

Mariyana Angelova is Assistant Professor at the Department of Political Science at Central European University. Her research focuses on legislative policy making and voter behaviour in parliamentary democracies. Her work has been published in leading journals including the British Journal of Political Science and Comparative Political Studies. [[email protected]]

Hanna Bäck

Hanna Bäck is a Professor of Political Science at Lund University. Her research mainly focuses on political parties, legislators and governments in parliamentary democracies. Her articles have, for example, appeared in British Journal of Political Science, Comparative Political Studies, and European Journal of Political Research. [[email protected]]

Wolfgang C. Müller

Wolfgang C. Müller was Professor of Democratic Governance, Department of Government, University of Vienna and is retired from teaching and administration. He has published extensively on political parties, political institutions and coalition politics, including Coalition Governments in Western Europe (co-edited with Kaare Strøm, OUP 2000), Cabinets and Coalition Bargaining (co-edited with Kaare Strøm and Torbjörn Bergman, OUP 2008), and Coalition Governance in Central Eastern Europe (co-edited with Torbjörn Bergman and Gabriella Ilonszki, OUP 2019). [[email protected]]

Notes

1 They can request relevant documents from the executive, schedule hearings, call witnesses, arrange open hearings and invite experts as well as interest group representatives (Martin and Vanberg Citation2011).

2 Healy and Lenz (Citation2014) show that voters rely on the end-heuristic when they engage in electoral accountability at elections. In particular, they find that voters substitute the end (policy situation in the election year) for the whole (policy outcomes during the whole legislative term) when they evaluate incumbents and hold them accountable at elections. This finding supports our argument that at elections voters are expected to discount the associated costs of policy concession which were agreed upon at the government formation stage in the beginning of the legislative term.

3 This is supported by in-depth studies which stress the parties’ acceptance of contractual sanctity as a ‘moral duty’ and associated reputational concerns (De Winter et al. Citation2000: 322; Müller Citation2000: 111; Timmermans and Andeweg Citation2000: 384).

4 According to this logic we would expect that coalition agreements of surplus coalitions reflect to a greater extent the preference of the parties providing a majority and less so the preferences of the surplus parties. We believe this constitutes an interesting avenue for future research.

5 We include additional controls for debt-levels in the online appendix (see Table A1a and Table A1d).

6 We use values as reported in the Comparative Political Data Set (Armingeon et al. Citation2020).

7 We run analyses with country fixed-effects in the Appendix (see Table A1b), which allow us to focus specifically on within-country effects. We also run models that include a lagged-dependent variable to account for any temporal or regression-to-the-mean effects (see Table A1c and Table A1d in the Appendix). We find no major substantive difference to the findings we report here. More detail about these models and their substantive interpretation can be found in the Appendix.

8 Though this term between government type and coalition agreement presented in Table 1 did not look significant, note that the coefficient presented there is always in reference to a base term. Brambor et al. (Citation2006: 74) remind us, ‘It is perfectly possible for the marginal effect of X on Y to be significant for substantively relevant values of the modifying variable Z even if the coefficient on the interaction term is insignificant… one cannot determine whether a model should include an interaction term simply by looking at the significance of the coefficient on the interaction term’. In the case at hand, a negative covariance between the base term (1.300) and the interactive term (0.969) actually would lead to a smaller standard error for this marginal effect of interest (Brambor et al. Citation2006: 70).

9 This can be roughly calculated looking at the agreement coefficient indicating 30% more reforms and the agreement*MWC coefficient indicating 3% (1–.969) fewer reforms.

References

- Andeweg, Rudy B., Lieven De Winter, and Patrick Dumont, eds. (2011). The Puzzle of Government Formation. London: Routledge.

- Andeweg, Rudy B., and Arco Timmermans (2008). ‘Conflict Management and Coalition Governance’, in Kaare Strøm, Wolfgang C. Müller, and Torbjörn Bergman (eds.), Cabinet Governance: Bargaining and the Cycle of Democratic Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 269–300.

- André, Audrey, Sam Depauw, and Shane Martin (2016). ‘“Trust Is Good, Control Is Better”: Multiparty Government and Legislative Organization’, Political Research Quarterly, 69:1, 108–20.

- Angelova, Mariyana, Hanna Bäck, Wolfgang C. Müller, and Daniel Strobl (2018). ‘Veto Player Theory and Reform Making in Western Europe’, European Journal of Political Research, 57:2, 282–307.

- Armingeon, Klaus, Virginia Wenger, Fiona Wiedemeier, Christian Isler, Laura Knöpfel, David Weisstanner, and Sarah Engler (2020). Comparative Political Data Set 1960–2018. Zurich: Department of Political Science, University of Zurich.

- Axelrod, Robert (1970). Conflict of Interest. Chicago, IL: Markham.

- Bäck, Hanna, Wolfgang C. Müller, Mariyana Angelova, and Daniel Strobl (2022). ‘Ministerial Autonomy, Parliamentary Scrutiny and Government Reform Output in Parliamentary Democracies’, Comparative Political Studies, 55:2, 254–86.

- Bäck, Hanna, Wolfgang C. Müller, and Benjamin Nyblade (2017). ‘Multiparty Government and Economic Policy-Making. Coalition Agreements, Prime Ministerial Power and Spending in Western European Cabinets’, Public Choice, 170:1-2, 33–62.

- Bassi, Anna (2017). ‘Policy Preferences in Coalition Formation and the Stability of Minority and Surplus Governments’, Journal of Politics, 79:1, 250–68.

- Beck, Elwood Meredith, and Stewart E. Tolnay (1995). ‘Analyzing Historical Count Data: Poisson and Negative Binomial Regression Models’, Historical Methods: A Journal of Quantitative and Interdisciplinary History, 28:3, 125–31.

- Bergman, Torbjörn, Hanna Bäck, and Johan Hellström, eds. (2021). Coalition Governance in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bowler, Shaun, Thomas Bräuninger, Mark Debus, and Indridi H. Indridason (2016). ‘Let’s Just Agree to Disagree: Dispute Resolution Mechanisms in Coalition Agreements’, Journal of Politics, 78:4, 1264–78.

- Brambor, Thomas, William Roberts Clark, and Matt Golder (2006). ‘Understanding Interaction Models: Improving Empirical Analyses’, Political Analysis, 14:1, 63–82.

- Bryce, James (1920). Democracies. New York: Macmillan.

- Carroll, Royce, and Gary W. Cox (2012). ‘Shadowing Ministers Monitoring Partners in Coalition Governments’, Comparative Political Studies, 45:2, 220–36.

- Carrubba, Clifford, and Craig Volden (2000). ‘Coalitional Politics and Logrolling in Legislative Institutions’, American Journal of Political Science, 44:2, 261–77.

- Conley, Richard, and Marija Bekafigo (2010). ‘‘No Irish Need Apply’? Veto Players and Legislative Productivity in the Republic of Ireland, 1949–2000’, Comparative Political Studies, 43:1, 91–118.

- Crombez, Christophe (1996). ‘Minority Governments, Minimal Winning Coalitions and Surplus Majorities in Parliamentary Systems’, European Journal of Political Research, 29:1, 1–29.

- Dalton, Russell J., David M. Farrell, and Ian McAllister (2011). Political Parties and Democratic Linkage. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- De Winter, Lieven, Arco Timmermans, and Patrick Dumont (2000). ‘Belgium. On Government Agreements, Evangelists, Followers and Heretics’, in Wolfgang C. Müller and Kaare Strøm (eds.), Coalition Governments in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 300–55.

- Ecker, Alejandro, Thomas M. Meyer, and Wolfgang C. Müller (2023, forthcoming). ‘The Architecture of Coalition Governance’, in Torbjörn Bergman, Patrick Dumont, Bernard Grofman, and Tom Louwerse (eds.), New Developments in Coalition Cabinet Research. New York: Springer.

- Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) (1988). Country Report: Portugal, May 1988. London: The Economist Intelligence Unit.

- Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) (1992). Country Report: Sweden, May 1992. London: The Economist Intelligence Unit.

- Eichorst, Jason (2014). ‘Explaining Variation in Coalition Agreements: The Electoral and Policy Motivations for Drafting Agreements’, European Journal of Political Research, 53:1, 98–115.

- Fehr, Ernst, Oliver Hart, and Christian Zehnder (2011). ‘Contracts as Reference Points – Experimental Evidence’, American Economic Review, 101:2, 493–525.

- Feller, Avi, and Andrew Gelman (2015). ‘Hierarchical Models for Causal Effects’, in R. A. Scott, and S. M. Kosslyn (eds.), Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences: An Interdisciplinary, Searchable, and Linkable Resource. Online Wiley. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/9781118900772.

- Fernandes, Jorge M., Florian Meinfelder, and Catherine Moury (2016). ‘Wary Partners: Strategic Portfolio Allocation and Coalition Governance in Parliamentary Democracies’, Comparative Political Studies, 49:9, 1270–300.

- Frydlinger, David, and Oliver Hart (2023, forthcoming). ‘Overcoming Contractual Incompleteness: The Role of Guiding Principles’, Journal of Law, Economics and Organization.

- Hallerberg, Mark, Rolf Rainer Strauch, and Jürgen von Hagen (2009). Fiscal Governance in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Harfst, Philipp, and Kai-Uwe Schnapp (2003). ‘Instrumente parlamentarischer Kontrolle der Exekutive in westlichen Demokratien', Discussion Paper Sp Iv 2003-201, Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin Für Sozialforschung (WZB). https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/handle/document/11154.

- Hart, Oliver, and John Moore (2008). ‘Contracts as Reference Points’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123:1, 1–48.

- Healy, Andrew, and Gabriel S. Lenz (2014). ‘Substituting the End for the Whole: Why Voters Respond Primarily to the Election‐Year Economy’, American Journal of Political Science, 58:1, 31–47.

- Hinckley, Barbara (1981). Coalitions & Politics. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- Indridason, Indridi H., and Gunnar H. Kristinsson (2013). ‘Making Words Count: Coalition Agreements and Cabinet Management’, European Journal of Political Research, 52:6, 822–46.

- Kim, Dong-Hun, and Gerhard Loewenberg (2005). ‘The Role of Parliamentary Committees in Coalition Governments. Keeping Tabs on Coalition Partners in the German Bundestag’, Comparative Political Studies, 38:9, 1104–29.

- Klüver, Heike, and Hanna Bäck (2019). ‘Coalition Agreements, Issue Attention, and Cabinet Governance’, Comparative Political Studies, 52:13–14, 1995–2031.

- Krauss, Svenja (2018). ‘Stability Through Control? The Influence of Coalition Agreements on the Stability of Coalition Cabinets’, West European Politics, 41:6, 1282–304.

- Laver, Michael, and Kenneth A. Shepsle (1996). Making and Breaking Governments. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Laver, Michael, and Kenneth A. Shepsle (1998). ‘Events, Equilibria, and Government Survival’, American Journal of Political Science, 42:1, 28–54.

- Laver, Michael, and Norman Schofield (1990). Multiparty Government. The Politics of Coalition in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lijphart, Arend (2012). Patterns of Democracy: Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Lipsmeyer, Christine S., and Heather Nicole Pierce (2011). ‘The Eyes That Bind: Junior Ministers as Oversight Mechanisms in Coalition Governments’, The Journal of Politics, 73:4, 1152–64.

- Lowe, Will, Kenneth Benoit, Slava Mikhaylov, and Michael Laver (2011). ‘Scaling Policy Preferences from Coded Political Texts’, Legislative Studies Quarterly, 36:1, 123–55.

- Luebbert, Gregory M. (1986). Comparative Democracy. Policymaking and Governing Coalitions in Europe and Israel. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Lupia, Arthur, and Kaare Strøm (1995). ‘Coalition Termination and the Strategic Timing of Parliamentary Elections’, American Political Science Review, 89:3, 648–65.

- Lupia, Arthur, and Kaare Strøm (2008). ‘Bargaining, Transaction Costs, and Coalition Governance’, in Kaare Strøm, Wolfgang C. Müller, and Torbjörn Bergman (eds.), Cabinet Governance: Bargaining and the Cycle of Democratic Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 51–83.

- Martin, Lanny W. (2004). ‘The Government Agenda in Parliamentary Democracies’, American Journal of Political Science, 48:3, 445–61.

- Martin, Lanny W., and Georg Vanberg (2004). ‘Policing the Bargain: Coalition Government and Parliamentary Scrutiny’, American Journal of Political Science, 48:1, 13–27.

- Martin, Lanny W., and Georg Vanberg (2005). ‘Coalition Policymaking and Legislative Review’, American Political Science Review, 99:1, 93–106.

- Martin, Lanny W., and Georg Vanberg (2011). Parliaments and Coalitions: The Role of Legislative Institutions in Multiparty Governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Martin, Lanny W., and Georg Vanberg (2014). ‘Parties and Policymaking in Multiparty Governments: The Legislative Median, Ministerial Autonomy, and the Coalition Compromise’, American Journal of Political Science, 58:4, 979–96.

- Martin, Lanny W., and Georg Vanberg (2020). ‘Coalition Governance, Legislative Institutions, and Government Policy in Parliamentary Democracies’, American Journal of Political Science, 64:2, 325–40.

- Mattson, Ingvar, and Kaare Strøm (1995). ‘‘Parliamentary Committees’, in Herbert Döring (ed.), Parliaments and Majority Rule in Western Europe. Frankfurt am Main: Campus, 249–307.

- McCubbins, Matthew, and Thomas Schwartz (1984). ‘Congressional Oversight Overlooked: Police Patrols versus Fire Alarms’, American Journal of Political Science, 28:1, 165–79.

- Moury, Catherin (2011). ‘Coalition Agreement and Party Mandate: How Coalition Agreements Constrain the Ministers’, Party Politics, 17:3, 385–404.

- Moury, Catherin (2014). Coalition Governments and Party Mandate: How Do Coalition Agreements Constrain Ministerial Action. London: Routledge.

- Moury, Catherin, and Arco Timmermans (2013). ‘Inter-Party Conflict Management in Coalition Governments: Analyzing the Role of Coalition Agreements in Belgium, Germany, Italy and The Netherlands’, Politics and Governance, 1:2, 117–31.

- Müller, Wolfgang C. (2000). ‘Austria. Tight Coalitions and Stable Government’, in Wolfgang C. Müller and Kaare Strøm (eds.), Coalition Governments in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 86–125.

- Müller, Wolfgang C., and Thomas M. Meyer (2010). ‘Meeting the Challenges of Representation and Accountability in Multiparty Governments’, West European Politics, 33:5, 1065–92.

- Müller, Wolfgang C., and Kaare Strøm, eds. (1999). Policy, Office, or Votes? How Political Parties in Western Europe Make Hard Decisions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Müller, Wolfgang C., and Kaare Strøm, eds. (2000). Coalition Governments in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Müller, Wolfgang C., and Kaare Strøm (2008). ‘Coalition Agreements and Cabinet Governance’, in Kaare Strøm, Wolfgang C. Müller, and Torbjörn Bergman (eds.), Cabinet Governance: Bargaining and the Cycle of Democratic Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 159–99.

- Naurin, Elin, Terry J. Royed, and Robert Thomson, eds. (2019). Party Mandates and Democracy. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Peterson, Robert L., and Martine M. De Ridder (1986). ‘Government Formation as a Policy-Making Arena’, Legislative Studies Quarterly, 11:4, 565–81.

- Pierson, Paul (2001). ‘Post-Industrial Pressures on the Mature Welfare States’, in Paul Pierson (ed.), The New Politics of the Welfare State. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 80–105.

- Saalfeld, Thomas (2008). ‘Institutions, Chance, and Choices: The Dynamics of Cabinet Survival’, in Kaare Strøm, Wolfgang C. Müller, and Torbjörn Bergman (eds.), Cabinet Governance: Bargaining and the Cycle of Democratic Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 327–68.

- Schermann, Katrin, and Laurenz Ennser-Jedenastik (2014). ‘Coalition Policy-Making Under Constraints: Examining the Role of Preferences and Institutions’, West European Politics, 37:3, 564–83.

- Strøm, Kaare, Wolfgang C. Müller, and Torbjörn Bergman, eds. (2008). Cabinets and Coalition Bargaining: The Democratic Life Cycle in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Strøm, Kaare, Wolfgang C. Müller, and Daniel M. Smith (2010). ‘Parliamentary Control of Coalition Governments’, Annual Review of Political Science, 13:1, 517–35.

- Thies, Michael F. (2001). ‘Keeping Tabs on Partners: The Logic of Delegation in Coalition Governments’, American Journal of Political Science, 45:3, 580–98.

- Thomson, Robert (2011). ‘Citizens’ Evaluations of the Fulfillment of Election Pledges: Evidence from Ireland’, The Journal of Politics, 73:1, 187–201.

- Thomson, Robert, et al. (2017). ‘The Fulfillment of Parties’ Election Pledges: A Comparative Study on the Impact of Power Sharing’, American Journal of Political Science, 61:3, 527–42.

- Timmermans, Arco (1998). ‘Conflicts, Agreements, and Coalition Governance’, Acta Politica, 33:4, 409–32.

- Timmermans, Arco (2006). ‘Standing Apart and Sitting Together: Enforcing Coalition Agreements in Multiparty Systems’, European Journal of Political Research, 45:2, 263–83.

- Timmermans, Arco, and Rudy B. Andeweg (2000). ‘The Netherlands. Still the Politics of Accomodation?’, in Wolfgang C. Müller and Kaare Strøm (eds.), Coalition Governments in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 356–98.

- Tsebelis, George (1999). ‘Veto Players and Law Production in Parliamentary Democracies: An Empirical Analysis’, American Political Science Review, 93:3, 591–608.

- Tsebelis, George (2002). Veto Players: How Political Institutions Work. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Volden, Craig, and Clifford Carrubba (2004). ‘The Formation of Oversized Coalitions in Parliamentary Democracies’, American Journal of Political Science, 48:3, 521–37.