Abstract

The Covid-19 pandemic triggered polarisation across Europe. While most citizens supported governments’ containment measures, others took to the streets and voiced their dissatisfaction. The article focuses on the mobilisation potential related to this heterogenous protest wave. It examines individuals that show sympathy and are willing to engage in anti-containment demonstrations based on 16 waves of a rolling cross-section survey fielded in Germany in 2020/2021. The results show a considerable and stable mobilisation potential: every fifth respondent sympathises with the protesters, and around 60% of those are ready to participate themselves. Political distrust, far-right orientations and an emerging ‘freedom divide’ structure the potential, as do Covid-19-related economic and health threats. Moreover, the findings indicate a radicalisation process and show how ideology and threat perceptions drive the step from sympathy to willingness to participate, suggesting that ideological polarisation may quickly spill over to the streets given an appropriate supply of protest opportunities.

Europe saw major protests targeting the state measures to contain Covid-19 since the beginning of the pandemic in the spring of 2020. Such anti-containment or anti-restriction protests have been particularly strong where strict policies had been adopted, while the mortality rate remained comparatively low (Kriesi and Oana Citation2022; Neumayer et al. Citation2021). Germany, the country under scrutiny in this study, is an illustrative case for the protest wave during the pandemic. Covid-related protests in the country emerged early during the pandemic, with several periods of heightened mobilisation and radicalisation. As large majorities adhered to anti-containment measures and supported the government’s approach to tackling the pandemic (e.g. Altiparmakis et al. Citation2021; Jørgensen et al. Citation2021), the protests became a ‘signifier of conflict’ in German society at large. Early on, diverse social and ideological groups took to the streets, ranging from hard-hit economic sectors and anti-vaccination groups to adherents of extreme left and right ideologies (e.g. della Porta Citation2022; Grande et al. Citation2021; Nachtwey et al. Citation2020; Koos Citation2021; Plümper et al. Citation2021). Organisers were mainly loose, often new networks and citizens’ action groups. Most important was the so-called Querdenker (‘lateral thinkers’) movement, increasingly shaped by a confrontational action repertoire and radical right claims and actors (Hunger et al. Citation2021). The latter mirroring developments elsewhere (e.g. Rohlinger and Meyer Citation2022; Brennan Citation2020; Ariza Citation2020).

The current study examines the mobilisation potential of these anti-containment protests to better understand the emerging polarisation during the Covid-19 pandemic. We take up the concept of ‘issue-specific mobilisation potential’, defined as ‘an individual’s propensity to engage in certain protest activities in order to defend his or her position with regard to a specific issue’ (Kriesi et al. Citation1993: 155). Specifically, we compare the share and the characteristics of those who show sympathy for the people protesting the containment measures and those who would take it to the streets themselves. This conceptual distinction draws on Klandermans’ (Citation1984) ground-breaking work on consensus and action mobilisation, differentiating processes of (a) convincing people that a social movement’s goals are worthwhile and (b) mobilising them to take part (for related research designs: Klandermans and Oegema Citation1987; Kriesi et al. Citation1993; Oegema and Klandermans Citation1994; Beyerlein and Hipp Citation2006; Rüdig and Karyotis Citation2014). Empirically, we draw on 16 waves of a rolling cross-section survey. The survey was fielded from June 2020 to April 2021, with a total of around 13,000 respondents, allowing us to capture the dynamics over this eventful period.

Why do we shift from studying actual protest behaviour to the attitudinal concept of issue-specific mobilisation potentials? We know from previous research that only a fraction of those who intend to participate ultimately take to the street (for a classic, see Klandermans and Oegema Citation1987). However, we agree with Kriesi et al. (Citation1993: 157) that noting the apparent difference does not render the study of mobilisation potentials ‘pointless’. By contrast, the study of potentials in the population captures an essential part of the mobilisation process. It allows identifying the social and political characteristics of individuals drawn to a particular protest or social movement, irrespective of the (un)available supply of protest events and organisers (Klandermans Citation1997). Thus, it helps observe the demand-side of protest beyond phases and geographic areas of overt mobilisation. Moreover, a focus on over-time changes captures the expansion of the mobilisation potential as a central outcome of social movements.

We find such an approach to the study of protest particularly insightful in dynamically, at times rapidly, changing contexts such as the Covid-19 pandemic and for the type of reactionary mobilisation at play (see Caiani Citation2019; Muis and Immerzeel Citation2017). Specifically, the present article makes two contributions to the scholarly literature – an empirical and a conceptual one.

First, we provide an exploratory empirical analysis of the social and political characteristics of individuals who show sympathy for or would participate in anti-containment protests. The analysis offers essential information about this significant, and for many observers puzzling, protest wave. Since the first anti-containment protests emerged in 2020, scholarly and public debates have centred around the heterogeneity of the social base, the ideological makeup, and the suspected radicalisation at play. Next to the evident empirical relevance of the specific case, the study offers more general insights in regressive social movements which have been on the rise in Europe’s protest arena during the last decades (e.g. Castelli Gattinara et al. Citation2022; Hutter Citation2014) and whose mobilisation are often marked by the participation of so-called ‘political outsiders’ (Borbáth Citation2023).

Second, we contribute to this special issue (Borbáth et al., Citation2023) by bringing the concept of issue-specific mobilisation potentials to the burgeoning research on ideological and affective polarisation. The concept of mobilisation potential has been prominent in social movement studies in the 1980s and 1990s. Yet, we argue that it has a lot to offer to current debates about transformations in European politics. Notably, it complements the attention to general ideological distributions, i.e. polarisation, in the population or across social groups (e.g. Traber et al., Citation2023) with a focus on individuals’ propensity to act on behalf of these preferences. We consider such individual predispositions particularly essential when linking polarisation research with studies on the emergence of new cleavages, defined as ‘durable patterns of political behaviour linking social groups and political organisations’ (Bornschier Citation2009: 3). The conceptual toolkit introduced by Klandermans (Citation1984) offers interesting avenues to study the link between the supply of collective political actors and the social structuration of the new cleavages (e.g. Marks et al. Citation2022).

This article is structured as follows: We first present a brief overview of protest politics during the pandemic and formulate expectations about the mobilisation potential of anti-containment demonstrations. Next, we present the research design, data, and strategy of analysis, before testing our hypotheses using descriptive and regression analyses. The results show a considerable and stable mobilisation potential: Every fifth respondent shows sympathy with the protesters, and around 60% of those are ready to participate themselves. Political distrust, far-right orientations, and an emerging ‘freedom divide’ structure the potential, as do Covid-related economic and health threats. Moreover, we observe a radicalisation in the ideological makeup and show how ideology and threat perceptions drive the step from sympathy to being ready to participate. We conclude with a summary of the findings and avenues for further research.

Protesting during and against the government’s containment measures

The Covid-19 pandemic and its global effect have been unprecedented in the last decades. Since the Spanish Flu hit Europe in the aftermath of the Great War and killed millions, no other health-related crisis has had a comparable global effect. Governments had to act quickly and issue policies to tackle the virus and its adverse effects on economies and citizens’ private lives (for an overview: Hale and Webster Citation2020).

At the onset of the pandemic, limitations on the freedom of assembly suddenly but often only briefly halted classical street protest (Bloem and Salemi Citation2021). Moreover, curfews and requirements, such as rules to keep distance and wear face masks, forced social movements to adjust their action repertoire accordingly (e.g. Kowalewski Citation2021; Pinckney and Rivers Citation2020; Pleyers Citation2020; Zajak et al. Citation2021). Data on the extent and nature of protest during the coronavirus pandemic is still scarce. Based on survey data, Borbáth et al. (Citation2021) show that about 10% of respondents in seven European countries stated that they went to a demonstration at least once during the early phase of the pandemic, a level comparable to that found in previous years. Case studies in the US show that protests petered out after the pandemic’s beginning. However, this standstill was followed by a heightened protest phase by conservative and progressive actors (Brennan Citation2020). Similarly, Kriesi and Oana (Citation2022), in their study of 31 European countries, report a precipitous decline in the number of protest events and participants in spring 2020. While protest levels rose again after that moment, the average number of events, especially the number of participants, remained lower in 2020 than in 2019.

The pandemic triggered different types of political actions (e.g. Gerbaudo Citation2020); ranging from civic engagement, like providing help to neighbours and elderly people (e.g. Carlsen et al. Citation2021), via protest events that expressed solidarity and support for health care staff or demanded better protection of economically hard-hit sectors to contention in opposition to the governments’ containment measures. Neumayer et al.’s (Citation2021) comparative protest event analysis shows that such anti-containment protests have been prevalent in countries with relatively strict measures and low death rates (cf. Kriesi and Oana Citation2022). Moreover, higher levels of trust in government and public administration are associated with fewer protests. In contrast, the degree of civil liberties (measured based on the freedom house index) is associated with more protests.

Germany is an illustrative case of these dynamics. The country has come comparatively well through the first phase of the pandemic but has – like many countries globally – faced a wave of protest in the spring and summer of 2020 (Van der Zwet et al. Citation2022). This phase of heightened protest was observed across Europe: Based on information from ACLED (the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project), Neumayer et al. (Citation2021) estimate 1,322 protest events in Germany between March 2020 and January 2021. In Spain (1,487 events) and in France (1,168 events) similar numbers were recorded, only Italy experienced slightly more protest with 2,618 protest events. The same trend applies to smaller European countries, such as Austria (130 events), Belgium (118 events), and the Netherlands (240 events). Kriesi and Oana’s (Citation2022) comparative study shows this peak in protest is mostly driven by countries in north-western Europe and – to a smaller extent – in central-eastern Europe. Their analysis of protest claims also demonstrates that Covid-related issues were highly salient, accounting for roughly 30% of all recorded protest events in 2020. In German protest politics, this trend is even more pronounced, with around every second event relating to the pandemic throughout 2020. Kriesi and Oana’s (Citation2022) analysis shows a common European prevalence of anti-restriction claims, while only few countries, for instance Spain, experienced a considerable amount of pro-restriction mobilisation. Many of these protest events were driven by conservative and radical right actors, as early studies on these protests show for the US, Australia, Italy, Spain, and the UK (Rohlinger and Meyer Citation2022; Brennan Citation2020; Ariza Citation2020). The same applies to Germany, the country under study here, where far-right actors were prominently involved in protest events (Hunger et al. Citation2021).

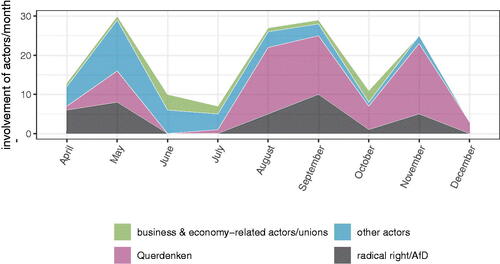

Detailed protest event data from our protest monitoring project MOTRA indicates three surges of Covid-related protests in Germany in 2020. The first peak right after the easing of the initial lockdown in April 2020 was characterised by a relatively broad array of protesting groups, including parents, the hotel and restaurant industry, and artists (). This situation, however, changed quite drastically in the subsequent months, when protests became larger and more homogenous in terms of their claims. Two massive demonstrations in Berlin with about 30,000 participants each in August mark the peak of this second surge. Not only the number of protesters but also the escalation dynamics sparked a nationwide outcry afterward: on August 29, 2020, several hundred protesters – many with visible extreme-right symbols – managed to circumvent safety barriers of the Bundestag and tried to ‘storm’, i.e. unlawfully enter, the parliamentary building. This incident reflects a general development with more radical actors gaining importance in the German anti-containment protests, such as the extreme-right Reichsbürger (‘Reich citizens’) and supporters of the QAnon movement. Most influential, however, has been the so-called Querdenker movement (‘lateral thinkers’) which originated in the Southern German city of Stuttgart and quickly expanded nationally. The group campaigned against the German Infection Protection Act. It drew criticism early on for attracting and accommodating diverse far-right actors and groups (Teune Citation2021a), including the far-right party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) (Lehmann and Zehnter Citation2022). As our protest event data shows, the shift in actors went along with increasingly confrontational protest forms and anti-system claims. The protesters increasingly rejected all the countermeasures to the pandemic, linked the coronavirus to (racist and antisemitic) conspiracy theories, and demanded the dismissal of the German government altogether.

Figure 1. Actors in German anti-containment protests in 2020.

Note: The protest event data of the MOTRA project is based on the manual coding of two German quality newspapers (Die Welt and Süddeutsche Zeitung).

Only a few studies have assessed the social and political underpinnings of the anti-containment protests in Germany. Notably, Plümper et al. (Citation2021) show that protests are more numerous in geographical areas where vote shares for mainstream parties have been low. Based on an on-site and online survey, Koos (Citation2021) shows an over-representation of older individuals dissatisfied with the crisis management among participants of a Querdenker demonstration in the city of Konstanz. At the same time, most respondents reported that they do not feel economically threatened by the pandemic and containment policies. However, they believe that the German government exaggerated the pandemic’s threat and expressed fears of long-lasting restrictions of political and civic rights.Footnote1 Based on a nonprobability online survey among members of Querdenker-Telegram channels, Nachtwey et al. (Citation2020) also observe the dominance of older and highly educated individuals. The supporters of the protests are alienated from the political system and tend to believe in conspiracy theories. While many respondents indicate having voted for left-wing parties in the past, potential voters of the far-right AfD in the next election are overrepresented compared to the general electorate. Finally, Grande et al. (Citation2021) have assessed the mobilisation potential of anti-containment protests among the German population at large. Grande et al. (Citation2021) report similar findings as Koos (Citation2021) and Nachtwey et al. (Citation2020) for political dissatisfaction and conspiracy theories. However, they find a different socio-economic profile when focussing on the wider potential in society. Specifically, there is little indication that more educated individuals show more sympathy for the protest. The mobilisation potential is rather heterogeneous regarding its social composition. By contrast, the authors emphasise the overrepresentation of AfD voters and individuals that do not feel represented by any party in the German parliament.

Explanatory framework

Initial research on anti-containment protests in Germany has tackled different groups, i.e. protesters, supporters, and members of protest-related information channels. The current article complements these studies with a systematic analysis of the issue-specific mobilisation potential in the wider population. We focus on sympathy and propensity to participate as different steps in the mobilisation process, following Klandermans’ (Citation1984) classical distinction between consensus and action mobilisation.Footnote2 Our research questions are as follows: Which individuals show sympathy for anti-containment protests? Which of them would take to the streets if they had the opportunity to do so? To answer these questions, we assess two sets of explanatory variables: political attitudes and ideological beliefs and Covid-related economic and health-related threats.Footnote3 As follows, we briefly review the scholarly literature and deduce expectations on the specific case of anti-containment protests in Germany.

Political attitudes and ideological beliefs

Political attitudes and ideological beliefs have a dual purpose in our study. First, they play a significant role in successful consensus mobilisation, as attitudinal alignment is considered pivotal to convincing citizens of a protest movement’s goals. Second, we also ask how holding certain, at times extreme, political attitudes and ideological beliefs might reinforce an individual’s propensity to participate in a protest. Specifically, we are interested in how the mobilisation potential of anti-containment protests relates to general left–right orientations, political distrust, and specific attitudes about freedom restrictions. Together, these factors allow us to better understand the political characteristics of this wave of Covid-related protests.

Previous scholarship is inconclusive on how left–right self-placement affects protest participation in Europe. While the streets in Western Europe generally have a left-libertarian bias (Torcal et al. Citation2016), recent studies stress the importance of contextual factors, such as historical legacies, and the specific claims and organisers of a protest event (e.g. Borbáth and Gessler Citation2020; Giugni and Grasso Citation2019; Grasso and Giugni Citation2019; Quaranta Citation2014). What we observe is a new differentiation in Europe’s protest arena where different ideological groups take it to the streets, often directly confronting each other (e.g. Borbáth Citation2023; Daphi et al. Citation2021).

At first sight, opposition to containment measures does not easily fit into classic left–right distinctions, given the multifaceted character of the coronavirus crisis and the potentially unifying claims of life and death. However, as research on Covid-related issues in party competition (Rovny et al. Citation2022) and the electorate (Ruisch et al. Citation2021) suggests, the political right has been less supportive of strict policies limiting the spread of the virus. By contrast, the political right favoured rules relying on citizen self-enforcement more than the political left. In addition, the previous section on the current state of the art has shown the increasingly central role of the far-right in organising and supporting the anti-containment protests in Germany. Based on these observations, we expect that individuals from the political right are more likely to belong to the mobilisation potential of the anti-containment protests than individuals from the political left (right-wing ideology hypothesis). Controlling for the right-wing bias of the anti-containment protests, we also expect individuals who hold extreme ideological beliefs from both left and right to be more likely to belong to the mobilisation potential than people from the political centre (extreme ideology hypothesis). The expectation relates to the comparatively confrontational action repertoire and the strong anti-system component of anti-containment protests (see also Hunger et al. Citation2021; Teune Citation2021b).

Like the general left–right orientation, the findings on the general relationship between political (dis)trust and protest behaviour tend to be mixed and context-dependent (e.g. Norris et al. Citation2005; Hooghe and Marien Citation2013; Braun and Hutter Citation2016). On the one hand, citizens disenchanted with political authorities are likely to partake in demonstrations to voice their frustration and anger. On the other hand, individuals with higher levels of trust in government might also take to the streets because they believe in the functioning of the political system and, thus, in the effectiveness of street protests – as illustrated by the recent Fridays for Future movement (de Moor et al. Citation2020). However, the claims of the anti-containment protests and initial survey-based research during the pandemic point in the former direction (e.g. Borbáth Citation2023). The anti-containment protestors are highly critical of the government and feel alienated from the political system. Given this anti-system component, we expect individuals who distrust the government to be overrepresented among the mobilisation potential of anti-containment protests (distrust hypothesis). Substantively, the distrust in the political elite’s management of the pandemic relates to the balance of public health and security, on the one hand, and restrictions on democratic norms and fundamental rights, on the other (Engler et al. Citation2021). This tension has been at the core of the anti-containment protests in Germany, as illustrated by the Querdenker’s insistence on the restoration of freedom and democracy. Thus, we expect individuals who view democratic principles and personal freedom as lastingly threatened to be more likely to belong to the mobilisation potential (freedom restrictions hypothesis).

Covid-related economic and health threats

Early approaches to the study of social movements focussed on the structural causes of protest action: structural strains or grievances have a disruptive impact on society, thus leading to the emergence of social movements (McAdam Citation1982). Especially suddenly-imposed grievances – like chemical spills, nuclear accidents, or economic crises – may facilitate mobilisation processes (Walsh Citation1981). For instance, the Chernobyl disaster enhanced discontent with nuclear energy and sparked anti-nuclear protests across Germany (Opp Citation1988). The primary focus of this literature has been inequality and economic deprivation fuelling protest and dissent (e.g. Gurr Citation1970; Regan and Norton Citation2005; Stekelenburg and Klandermans Citation2013; Kurer et al. Citation2019). Recently, Rüdig and Karyotis (Citation2014) found that the perceived size of economic deprivation has been a crucial predictor of support for protesting the unprecedented austerity measures in Greece. Interacting micro-level grievances with contextual influences, Grasso and Giugni (Citation2016) also show that individual deprivation is a stronger predictor for protest action in contexts when individuals are more aware that their struggle is a general one, thus being politicised rather than individualised.

The Covid-19 pandemic resulted in a multifaceted crisis with severe economic and health-related threats distributed unevenly across society. Starting with economic threats, the containment measures hit the German economy hard. It shrank by 5%, accompanied by a significant rise in unemployment,Footnote4 severe falls in household spending, and a decline in total production of goods and services of 10%—the sharpest on record in post-war history (Walker Citation2021). Many businesses had to shut down because of the national lockdown. To save jobs during the pandemic, state-sponsored furlough schemes, Kurzarbeit (short-time work), were widely implemented in Germany. After reaching its peak with 6 million short-time workers in April 2020 (Eichhorst and Rinne Citation2020), their number gradually decreased in the following months. A crucial measure implemented worldwide to fight the spread of Covid-19 infections was school and day-care closings. In Germany, federal states closed schools for extended periods creating a ‘disruptive exogenous shock’ to family life (Huebner et al. Citation2020). This strategy had consequences beyond the adverse effects on children’s educational outcomes, as parents were confronted with additional child-caring and home-schooling duties. The additional care work decreased well-being and increased perceived stress. It also led to financial hardships arising from reduced working hours, casting further economic strains on households with children (Chen et al. Citation2022). From a grievance perspective, one can expect individuals who suffered financial losses or had to shoulder more care work to develop grievances towards the government. These expectations are also true for individuals who perceive that they are at a greater risk of losing their jobs or being furloughed. Accordingly, we expect individuals with greater Covid-related economic threat to be more likely to belong to the mobilisation potential of anti-containment protests (economic threat hypothesis).

In addition to economic threats, health-related threats may also play a role. Studies show that individuals who are not afraid of getting infected or do not perceive to be at risk are much less likely to comply with Covid-related policy measures, such as wearing masks, social distancing, or avoiding public gatherings (Zimmermann et al. Citation2022). Early in the pandemic, public health authorities identified two key characteristics associated with a greater health risk: old age and pre-existing medical conditions (CDC 2021). However, lockdowns and other Covid-19 containment measures affected everyone regardless of demographic characteristics or health status. Thus, it is likely that individuals with a lower (perceived) threat to their health feel unfairly treated and develop grievances against the governing bodies for implementing them. We, therefore, expect that individuals with greater actual and perceived Covid-related health threats are less likely to belong to the mobilisation potential of anti-containment protests (health threat hypothesis).

In general, we expect all hypotheses to hold for both steps in the mobilisation process (reinforcement hypothesis). We assume that ideological beliefs, political attitudes, and Covid-related economic and health threats explain who shows sympathy for the anti-containment protesters and, controlled for that sympathy, they also explain who is even likely to participate him/herself. In our opinion, this reinforcing dynamic indicates an intense form of ideological polarisation, which is most likely in situations when a protest or social movement becomes a ‘signifier of conflict’ itself. Note that the reinforcing dynamic seems least likely for the two ‘threat factors’. Protest research has also subsumed these variables (especially employment status and child-care obligations) under the term biographical availability, defined ‘as the absence of personal constraints that may increase the cost and risks of movement participation’ (McAdam Citation1986: 70). These costs are understood as ‘the expenditures of time, money, and energy that are required of a person engaged in any particular form of activism’ (McAdam Citation1986: 67).Footnote5 Thus, interpreted in this perspective, obligations, such as having children at home who require care, increase the costs of activism and are likely to hinder protest participation (Wiltfang and McAdam Citation1991, 997). Moreover, the two sets of explanatory factors in our theoretical framework might contradict each other. Economic and health threats can also drive beliefs in the necessity of decisive state action to fight Covid-19. Thus, they might trigger political responses, but not in the right-leaning, government-distrusting, and citizen-self enforced direction expected when considering the attitudinal and ideological underpinning of the anti-containment protests in Germany.

Data and methods

We use original survey data to empirically assess the associations of political and social characteristics with the mobilisation potential of anti-containment protests,. The survey covers various social and political topics related to the Covid-19 pandemic in Germany. The respondents were recruited by respondi from an online access panel. To ensure that different demographic groups are equally represented in the survey, quotas regarding education, age, and gender were used for the selection of respondents.Footnote6 The survey was conducted in 23 waves in a so-called rolling cross-section procedure. Between 512 and 1,044 persons were interviewed per wave. This procedure enabled us to react to unforeseeable or currently relevant events and to adapt our questionnaire. Thus, starting with the 8th wave of the survey in June 2020, we included items about the current protest events.

Dependent variables

Two items were tailored to measure the respondents’ sympathy for and readiness to participate in protests related to the Covid-19 pandemic. The exact wording of the ‘sympathy question’ was: ‘How understanding are you of the people who took part in demonstrations against the state’s coronavirus measures?’ [Answer options: Very, fairly, somewhat, not at all].Footnote7 We deliberately opted to ask about ‘the people in the streets’ and not about specific claims of the protests. First, we argue that, in dynamic and polarised contexts, such measure is more suitable given that the movements’ exact goals were often time vague and changed during the protest wave. Second, we argue that ultimately a movement consists of the crowd on the street and thus sympathy towards participants is crucial when studying the different steps of mobilisation. We asked for the respondents’ readiness to participate using the following question: ‘Would you take part in a demonstration against the state’s coronavirus measures if one were organised in your area?’ [Answer options: certainly, probably, rather not, certainly not]. Phrasing the latter question in that manner prevents a bias for respondents that lived in an area without demonstration, which were particularly rare in the early phase, thus introducing bias of lacking protest supply. We re-coded the resulting variables as binary, where 1 indicates that an individual reported ‘very much’ or ‘much’ sympathy or would ‘certainly’ or ‘probably’ participate in anti-containment protests.

Asking people’s attitudes towards protest is no trivial exercise and might lead to a social desirability bias, especially in polarised cases such as the anti-containment protests in Germany. Respondents may be reluctant to admit their sympathy for the protests and refrain from expressing their willingness to participate. To address these concerns, we conducted a list experiment in a later round of the survey (Hunger et al. Citation2022): the control group is presented with a 3-item list of political engagement, while the treated group is presented with a 4-item list that additionally includes the sensitive item, i.e. participating in the anti-containment protest. The respondents are then asked to state in how many activities they would participate. By comparing the two groups, the share of individuals that would participate in the sensitive protests can be determined. Hunger et al.’s (Citation2022) detailed analysis shows that there is no social desirability bias.

Political attitudes and ideological beliefs

To test our explanatory framework, we take advantage of the broad array of issues and items in the survey to operationalise the theoretically motivated clusters of factors outlined above. For political attitudes and ideological beliefs, we use political left–right self-placement, a measure of political trust (i.e. to what extent respondents believed that the federal government is acting in the interests of German citizens during the Covid-19 crisis), and two scales that grasp the respondents’ worry about political and individual freedom restrictions. The measure for worries about political freedom restrictions combines four survey items via means of principal component analysis (see online appendix, section 6). The items are the following: asking respondents how worried they are about (1) restrictions on the freedom to assembly; (2) the government’s bypassing of parliaments when issuing coronavirus containment policies; (3) restrictions on public life; and 4) restrictions on private contacts.Footnote8

Economic and health-related threats

We operationalise economic and health-related threats using different measures of economic vulnerability (i.e. the risk of being fired or furloughed and having children at home), perceived health risks (i.e. how worried respondents were that a coronavirus infection would cause them or a member of their immediate family to develop a life-threatening illness and their own health assessment) and factual health risks (i.e. pre-existing medical conditions and age of the respondent).Footnote9

Control variables

We control for several demographic, contextual, and temporal variables: education, gender, marital status, personal experience with the virus, general economic situation, whether the respondent resides in East Germany, and the wave of the survey.Footnote10 The data, however, does not include a direct measure of respondents’ social class. Moreover, the longitudinal data does not include information on additional key explanatory factors for participation such as respondents’ embeddedness in mobilising structures, political interest, and political efficacy beliefs.

Data analysis strategy

We limit our sample to complete cases leaving us with 12,815 respondents, of which 2,304 express sympathy for the protests against the government’s containment measures. Very few respondents expressed willingness to participate but no sympathy of the protests. As our two dependent variables – sympathy for and willingness to participate in anti-containment protests – are coded binary, we use logistic regression analyses to test our hypotheses. This allows us to test the two steps of the mobilisation process in two separate analyses. Previous scholarship has used empirical approaches such as structural equation models (Beyerlein and Hipp Citation2006), which is unsuitable since we consider more explanatory factors in our analyses. Like Rüdig and Karyotis (Citation2014), we use logistic regression models and run separate models for the different dependent variables for several reasons. First, this allows us to evaluate the steps independently, without giving us averaged coefficients for step 1 and step 2 as a classic ordered logit would do. While the first model assesses drivers of sympathy solely, the second model is concerned with what motivates individuals to move beyond sympathy to readiness to participate. Additionally, we run a series of robustness checks and complementary analyses with alternative model specifications, further corroborating our findings (see online appendix, sections 7, 9 to 11).

Empirical results

Descriptive findings

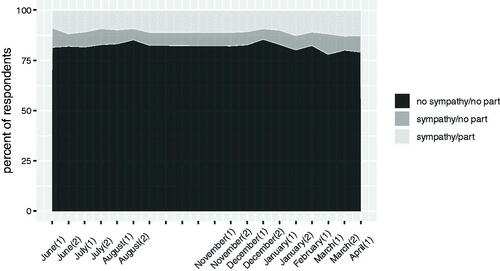

At first, we use this novel data set to assess the size of the mobilisation potential, especially the gap between protest sympathy and willingness to participate. shows shares of respondents broken down into three categories: The first group consists of respondents who do not sympathise with or are not willing to participate in anti-containment protests; the second group are the respondents who show sympathy for the protestors but are not willing to participate in them; the third group are the respondents who show sympathy for the protestors and are also ready to act on their beliefs given a supply of protest. As the results highlight, most respondents – on average 82% – neither sympathise nor are likely to participate in anti-containment protests. Nevertheless, around every fifth respondent belongs to the broadly defined mobilisation potential of the anti-containment protests. Around 60% who showed sympathy for anti-containment protests also stated that they would be willing to engage in protest themselves. Thus, around 10% of Germans can imagine themselves participating in anti-containment protests. Notably, the shares of all three groups are relatively stable from June 2020 to April 2021. This stability is remarkable considering the background of the dynamically evolving protest landscape described before.

Figure 2. Development of sympathy and readiness to participate in anti-containment protests by survey wave (2020–2021).

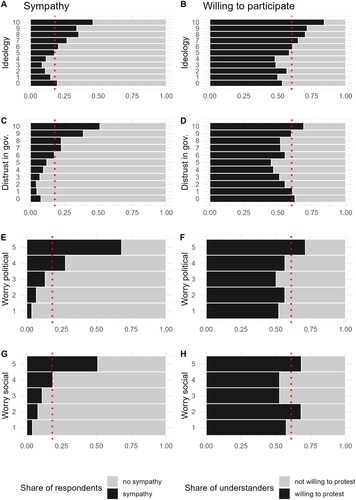

Next, we focus on the bivariate associations with political attitudes and ideological beliefs (). We examine left–right self-placement, distrust in government, and how much a respondent worries about freedom restrictions (we differentiate here ‘social’ and ‘political’ worries instead of the combined measure as used in the regression analyses below). The graphs in the first column of (panels A, C, E, G) present the share of participants who show sympathy for the protests by these political attitudes. The graphs in the second column present the shares of ‘sympathisers’ who would also be willing to participate in the demonstrations.

Figure 3. Share of groups by respondents’ attitude.

Note: Left–right self-placement is measured on an 11-point scale from 0, left, to 10, right. Trust in government also ranges from 0, do not trust at all, to 10, trust completely. Worries about individual and political freedoms are composite measures (see online appendix sections 1 and 2). They range from 1 to 5, lower values indicating less concern. Note that the graphs in the first column present the share of participants who show sympathy for the protests by these political attitudes. The graphs in the second column focus on the shares of ‘sympathisers’ and their (non-)willingness to participate in the demonstrations.

Panel A in on the left–right self-placement of respondents shows that the further we move away from the political centre towards the extreme right, the larger the share of sympathisers, thus providing the first indication for our right-wing ideology hypothesis. However, looking on the opposite fringe of the political spectrum, sympathy for the anti-containment protest is also slightly more common among the most left-leaning respondents. Similarly, supporters who expressed their willingness to participate in anti-containment protests (panel B) are over-represented on the right side of the political spectrum. Around 90% of supporters on the most extreme right would also participate in such demonstrations. Next, panel C in relates to our distrust hypothesis, showing the share of protest sympathisers across different levels of distrust in government. This offers preliminary support for our hypothesis that respondents with lower trust are more likely to belong to the mobilisation potential due to the strong anti-system component of the protests. Mirroring the context-dependent association between political trust and protest behaviour, respondents with higher and lower levels of trust in government among the ‘sympathisers’ are more willing to participate (panel D). Lastly, we turn to the descriptive relationship between worries about political and individual freedom restrictions and protest support and potential participation (panels E to F). Our freedom restrictions hypothesis posits that worries about democratic principles and personal freedoms are associated with higher sympathy and willingness to participate. This is strongly reflected in the descriptive evidence: People who worry more about these aspects are clearly overrepresented in the group of those who show sympathy for the protestors. However, the picture is less clear when we turn to willingness to participate among the supporters (panels G and H).

Regression analyses

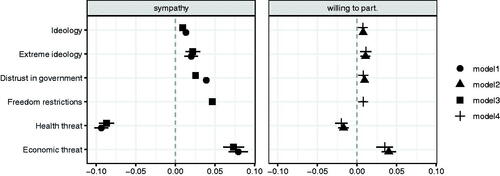

In the following, we present the central results of our logistic regression analyses in . The models on the left-hand side use sympathy for the anti-containment protests as the dependent variable. In contrast, we use the willingness to participate as the dependent variable in the models on the right panel. For each of the dependent variables, we present two different models: one for the full sample (models 1 and 2) and one for the reduced sample (models 3 and 4) to be able to include the measure for worries about freedom restrictions, since these items were only included in the survey from wave 14 onwards. Our empirical setup allows us to understand what drives people to feel sympathy for anti-containment protest and express their willingness to participate. This enables us to investigate the determinants of the mobilisation potential of anti-containment protests among a representative sample of the German population. Mirroring the theory section, we discuss the independent variables in two clusters: (i) political attitudes and ideological beliefs and (ii) Covid-related economic and health threats. We start the discussion by focussing on the drivers of protest sympathy (models 1 and 3) before proceeding to factors associated with willingness to participate (Model 2 & 4). reports average marginal effects. In the text, we discuss the substantive effect sizes by reporting how, on average across all of the cases in our data, each variable affects the probability of sympathy or being willing to protest.

Figure 4. Average marginal effects of logistic regression models predicting sympathy for and willingness to participate in anti-containment protests.

Note: The full regression models with all control variables can be found in the online appendix section 5. The coefficients come from models excluding (models 1 and 2) and including (models 3 and 4) ‘worries about freedom restrictions’, which have only been asked from August 2020 onwards. A coefficient depicted in corresponds to the association between a change in an independent variable and a change in the dependent variable. Please also note that the models with willingness to participate as DV include sympathy as an additional IV.

Regarding political attitudes and ideological beliefs, the findings meet our expectations regarding sympathy for the anti-containment protests (see left-hand side of ). As predicted by the right-wing ideology hypothesis, a one-unit increase on our 10-point scale for ideology increases the probability of showing sympathy for the anti-containment demonstrations by 1%.Footnote11 While these effects may seem small at first glance, we argue that they are substantive, since a change of one point on a 10-point scale is also very fine-grained. How different ideological dispositions affect sympathy and propensity to protest is further visualised and discussed below (see ). To test for the extreme ideology hypothesis, we also include a measure for more extreme political beliefs in our regression models. On our three point-extremism scale, respondents who are at the extreme right and extreme left of the ideological scale, are 2% more likely to be among those who express sympathy for anti-containment protests, which is in line with our hypothesis and with the descriptive evidence in . We explore the role of extreme ideology further by including a quadratic term of left–right ideology in the regression model to test for a potential curvilinear relationship (see online appendix, section 9). Our results indicate a minor curvilinear relationship which is strongly biased towards the right. Overall, these findings suggest that right leaning individuals and particularly those on the extreme right are more likely to support the anti-containment protests. Moreover, we find that a one-unit increase in our distrust in the German government measure increases the probability of sympathy for the protests by 4%, confirming our expectations concerning the relationship between distrust in government and protest sympathy (distrust hypothesis).Footnote12 Turning to model 3 in , we investigate whether worries about lasting freedom restrictions positively affect sympathy for the anti-containment protestors. Our results support the idea of an emerging ‘freedom divide’: respondents who are one-unit more concerned about freedom restrictions are also 5% more likely to show sympathy for the anti-containment protests.

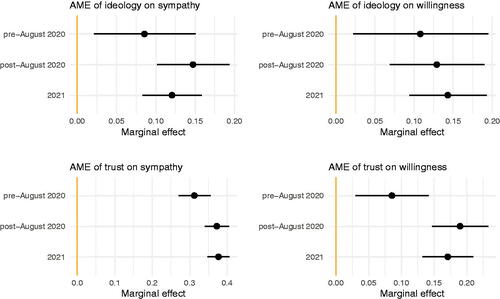

Figure 5. Average marginal effects of left–right ideology and trust in government conditional on time.

Note: shows the average marginal effects for two variables – ideological self-placement and distrust in the government. Interacting the variables with different time periods allows for assessing how much their effect on protest sympathy and willingness to participate changes over time. The regression models include all our standard independent variables, expect for freedom restrictions, which were only asked from wave 14 onwards.

Next, we turn our attention to the associations of economic and health-related grievances with protest sympathy. As expected, individuals who fear the coronavirus are less likely to show sympathy (-9%), while economic grievances are associated with significantly more sympathy for the anti-containment protestors. Specifically, a one-unit increase on the economic concerns index, increases the probability of showing sympathy by 8%. These findings are in line with the economic threat and health threat hypotheses.

In the second step of our estimation strategy, we focus on those respondents who expressed their willingness to participate in the protests (see right-hand side of ). We include the sympathy variable in these regressions as an independent variable. This allows us to investigate what makes sympathisers ‘walk the extra mile’, i.e. motivates them to be willing to participate in demonstrations. For simplicity, these coefficients are not included in (please refer to the regression table for the main models in the online appendix, section 5). As we have posited in our reinforcement hypothesis, sympathy for the protestors strongly determines their willingness to participate. However, even when controlling for this sympathy, our results shed light on the significance of attitudes for later stages of a mobilisation process. While previous research usually stresses the role of ideology and political attitudes for consensus mobilisation, our findings tell a story of reinforcement. While controlling for the group of ‘sympathisers’, we show that political attitudes are still crucial for the next step in the mobilisation process, i.e. voicing willingness to protest. Right-wing ideological beliefs (1% increase), distrust in government (1% increase),Footnote13 and worries about the damaging effect of Covid-19 on democratic principles and personal freedoms (1% increase) significantly increase the probability of the second dependent variable, i.e. willingness to participate. These findings indicate that even though more radical and distrusting individuals are already more likely to sympathise with the protestors, these characteristics also enhance their willingness to participate.

We observe a similar reinforcing dynamic for health and economic threats: being threatened by the virus significantly decreases the probability of being willing to participate in the demonstrations. As we have argued above, this effect might also stem from the fear of getting infected during a demonstration, where standard hygiene rules, such as wearing masks and social distancing, were often not adhered to. On the contrary, economic threats have a potentially mobilising effect. A one-unit increase in the economic threats scale is related to a marked increase in the probability of partaking in protests (4%).

In a final step, we test whether our results depend on the timing of the survey waves by running models in which we interact three crucial periods of mobilisation with several variables of interest. (for detailed results, see section 8 in the online appendix). This serves as an additional control for the dynamically evolving protest landscape during the Covid-19 pandemic. The actor constellation and major protest claims changed throughout the pandemic, indicating increasing radicalisation. The three-time periods are the survey waves before August 2020, after August 2020—when the anti-containment protests escalated notably—and the survey waves in 2021. As ideological self-placement and trust in government are identified as crucial drivers of mobilisation, shows the average marginal effects of these individual variables conditional on period. The results suggest a certain tendency of ideological dispositions to become more important in driving sympathy and willingness to protest over time. However, note that only the association between trust in government and willingness to protest is statistically significant. Similarly, we do not find strong over-time differences regarding extreme ideology as well as economic and health threats, reflecting a rather stable size of the mobilisation potential throughout the observation period.

Conclusion

This article has focussed on the mobilisation potential of anti-containment protests in Germany. The country has seen public demonstrations and other protest actions targeting the state measures to contain Covid-19 early on during the pandemic, with several peaks of heightened mobilisation and radicalisation. We have analysed individuals’ sympathy for and willingness to engage in such anti-containment demonstrations based on 16 waves of a rolling cross-section survey from 2020/2021. The study contributes in two ways to the scholarly literature in general and this special issue more specifically: First, we have presented an original large-scale study on the mobilisation potential of this unusual protest wave, allowing us to study the emerging polarisation in European societies during the Covid-19 pandemic. Specifically, our empirical analyses have examined two clusters of explanatory factors: individuals’ political attitudes and their (perceived) economic and health-related threats. Second, our study brings to the currently burgeoning research on polarisation the concept of issue-specific mobilisation potentials. Pioneered by Klandermans (Citation1984), the concept has been prominent in social movement research of the 1980s and 1990s. It helps observe the demand-side of protest beyond phases and geographic areas of overt mobilisation. As we argue, the concept offers a welcome addition to research on ideological polarisation, putting individuals’ propensity to act on behalf of their preferences centre stage. It also allows moving beyond a narrow focus on electoral behaviour, which seems particularly relevant in times when protest campaigns and social movements become key ‘signifiers of conflict’.

The empirical analyses point to four main conclusions: First, we observe a considerable and stable mobilisation potential of anti-containment protests in Germany from June 2020 to April 2021. Around every fifth respondent shows (very) much sympathy for the people demonstrating against the government’s measures; around 60% of those would also participate in demonstrations if they had the opportunity to do so. Second, political distrust is a primary driver of the mobilisation potential, confirming previous research about citizens’ preferences for containment measures (e.g. Altiparmakis et al. Citation2021; Jørgensen et al. Citation2021). Yet, the mobilisation potential is also embedded in left–right conflict and emerging divides over political freedom restrictions. Far-right orientations and worries about lasting freedom restrictions explain individuals’ sympathy and willingness to participate in anti-containment protests. Third, economic threats (including child-care obligations) relate to more sympathy for the protests, whereas health threats (including older age groups) relate to less sympathy. Finally, and most notably in the context of the special issue, we find that the step from showing sympathy for the protestors to being ready to participate is mainly driven by political attitudes and not by anticipated biographical constraints. As posited in our reinforcement hypothesis, this result suggests that ideological polarisation may quickly spill over to the streets depending on the availability of opportunities to protest.

Overall, our findings underline that the Covid-19 pandemic—and its nature as a multifaceted crisis—have led to political polarisation beyond party competition. Further research should focus on how the protests and their resonance in German society and other European countries have been structuring public debate over the containment measures in general and the legitimacy of protest and dissent in particular. These questions seem crucial to improve our understanding of how the anti-containment protests have been embedded in the broader landscape of political contestation during the pandemic and to what extent they may also have a lasting impact on citizens’ beliefs in a post-pandemic era. Since our findings show how polarised attitudes can easily spill over to the streets, a deeper engagement with consensus mobilisation offers an additional avenue for further research, contributing to our understanding of what drives people ‘to act on their beliefs’. While large shares of the literature on consensus mobilisation have focussed on progressive movements, our study covers a more reactionary type of mobilisation, mirroring a common trend of emerging regressive movements in Europe and beyond (Caiani Citation2019; Castelli Gattinara et al. Citation2022; Hutter Citation2014).

Our study was limited in its lack of focus on several essential concepts from the social movement and political participation literature: the role of mobilising structures, class belonging, and the role of political interest and efficacy. Due to the specifics of our case, we see further need to investigate how the novel, and thus less homogenous Querdenken movement ties in with individual level characteristics such as social status and class belonging. Unfortunately, our survey did not allow us to investigate how organisational infrastructures or measures of internal or external political efficacy may have contributed to the sympathy and willingness to protest. Future research, for example, could explore whether anti-containment protests have been more successful in mobilising supporters in national or regional contexts where a dense organisational infrastructure contesting the status quo was already in place pre-pandemic. We also would invite further scholarship to investigate how online mobilisation affected offline participation, especially in the context of the pandemic where face-to-face-interactions were thwarted by the anti-containment policies against the spread of the pandemic.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (340.5 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the reviewers of West European Politics and the journal editors for their valuable and thoughtful feedback. Earlier versions of this paper were presented at a panel on ‘Political Polarization’ at the DVPW Conference 2021, as well as in the Friday Seminar Series at the Department of Political Science in the School of Social Sciences and Philosophy, Trinity College Dublin. We thank the participants of these workshops and seminars as well as Lukas Stoetzer and Endre Borbáth for their helpful comments on earlier drafts. We also thank our research assistants Hannah Siebert, Anton Leue, Leonhard Schmidt and Meret Stephan for their assistance during the writing process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sophia Hunger

Sophia Hunger is a post-doctoral research fellow at the Centre for Civil Society Research, WZB Berlin Social Science Centre. [[email protected]]

Swen Hutter

Swen Hutter is Lichtenberg-Professor of Political Sociology at Freie Universität Berlin and Director of the Centre for Civil Society Research, a joint initiative of Freie Universität and the WZB Berlin Social Science Centre. [[email protected]]

Eylem Kanol

Eylem Kanol is a post-doctoral research fellow in the unit ‘Migration, Integration, Transnationalization’ at the WZB Berlin Social Science Centre. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 Some findings—for instance that 47% of the online interviewees hold a university degree and 51% of them are more than 50 years old—might be driven by the survey design and the location of the protest in Baden-Württemberg, which might not be representative for the movement in other parts of Germany (Koos Citation2021: 12).

2 Originally, Klandermans introduced four steps: first, an individual becomes a member of the group of potential participants; second, this individual is exposed to attempts at mobilisation; before third, s/he develops a motivation to participate; and lastly, overcomes barriers to participation. Subsequent studies have typically considered individuals that are already potential participants, i.e. are already convinced of the movement’s goals (for an overview, see Stürmer and Simon Citation2004; notable exceptions are Beyerlein and Hipp Citation2006; Kriesi et al. Citation1993; Rüdig and Karyotis Citation2014). However, in this paper, we are interested in the first and third steps: selection into sympathy and selection into willingness to participate in anti-containment protests.

3 One important variable from the social movement theories that has been prominently used in explaining the emergence and prevalence of protest and collective action is mobilising structures (McAdam et al. 1996; McCarthy and Zald Citation1977). Mobilising structures provide the infrastructure, resources, staff, and safe spaces for interactions, recruitment, ideological encapsulation and protest organisation. Proponents of this approach argue that activism and mobilisation are more likely to occur and endure if there is a dense organisational and institutional infrastructure (e.g. McCarthy and Zald Citation2015). Although, we acknowledge the importance of this variable, unfortunately our survey design did not include any items on the mobilising structures to enable us to investigate their role in the anti-containment protests in Germany. We address this limitation in the concluding section.

4 According to a report published by the Institute of Labour Economics, ‘the number of registered unemployed stood at 2.75 million persons [in October 2020], an increase by 25% compared to October 2019’ (Eichhorst and Rinne Citation2020: 3).

5 Following this line of argumentation, parental status, for example, has been considered a crucial biographical availability variable (Oliver Citation1984; CitationBeyerlein and Hipp Citation2006).

6 Additionally, the sample corresponds well to the distribution of the population across the federal states. There are some minor differences: Baden-Württemberg is slightly underrepresented with −2.4 percentage points, whereas Berlin (+1.1) and Hamburg (+1.2) are slightly overrepresented (see online appendix, Table 2).

7 In the questionnaire, we used the German word ‘Verständnis.’ Literally translated as understanding, the term refers to (a) comprehension, the ability to understand the content of an issue; (b) empathy, the ability to put oneself in the place of other people and to sympathise with them; and (c) opinion, in the sense of a view or point of view. We opted for it because it captures a weak form of support. After consulting with several native speakers, we opted for the English translation ‘sympathy,’ aiming to avoid the narrower definition of ‘understanding’ as comprehension.

8 See also online appendix section 1.1 for more details on the operationalisation

9 See also online appendix section 1.2 for more details on the operationalisation

10 See also online appendix section 1.3 for more details on the operationalisation

11 Including the worry about political and social freedoms variable in the regression models does not considerably change the coefficients of the other independent variables. We therefore report the odds ratios from the regression models without this variable (models 1 and 2).

12 Since most of our data includes a measure of political trust that is closely related to the pandemic, we perform additional robustness checks using an item that asks for trust in politicians and political parties in general. Note that these measures have only been asked in later survey waves. The models in the online appendix, section 10, show that the results are consistent with the main models presented in the text (models 1 and 3 in Table 11, online appendix).

13 Please note, however, that this association is not robust to include alternative measures for political trust, i.e. trust in politicians and parties, and not trust in the government as the key executive institution (see online appendix, section 10).

References

- Altiparmakis, Argyrios, Abel Bojar, Sylvain Brouard, Martial Foucault, Hanspeter Kriesi, and Richard Nadeau (2021). ‘Pandemic Politics: Policy Evaluations of Government Responses to COVID-19’, West European Politics, 44:5–6, 1159–79.

- Ariza, Cristina. (2020). ‘From the Fringes to the Forefront: How Far-right Movements Across the Globe Have Reacted to Covid-19’, Institute for Global Change. https://institute.global/policy/fringes-forefront-how-far-right-movements-across-globe-havereacted-covid-19.

- Beyerlein, Kraig, and John Hipp (2006). ‘A Two-Stage Model for a Two-Stage Process: How Biographical Availability Matters for Social Movement Mobilisation’, Mobilisation: An International Quarterly, 11:3, 299–320.

- Bloem, Jeffrey R., and Colette Salemi (2021). ‘COVID-19 and Conflict’, World Development, 140, 105294. April, Article 105294.

- Borbáth, Endre. (2023). ‘Differentiation in Protest Politics: Participation by Political Insiders and Outsiders’, Political Behaviour, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-022-09846-7.

- Borbáth, Endre, Swen Hutter, and Arndt Leininger (2023). ‘Cleavage Politics, Polarisation and Participation in Western Europe’, West European Politics, https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2022.2161786

- Borbáth, Endre, and Theresa Gessler (2020). ‘Different Worlds of Contention? Protest in Northwestern, Southern and Eastern Europe’, European Journal of Political Research, 59:4, 910–35.

- Borbáth, Endre, Sophia Hunger, Swen Hutter, and Ioana-Elena Oana (2021). ‘Civic and Political Engagement During the Multifaceted COVID-19 Crisis’, Swiss Political Science Review, 27:2, 311–24.

- Bornschier, Simon. (2009). ‘Cleavage Politics in Old and New Democracies’, Living Reviews in Democracy, https://www.zora.uzh.ch/id/eprint/26412/

- Braun, Daniela, and Swen Hutter (2016). ‘Political Trust, Extra-Representational Participation and the Openness of Political Systems’, International Political Science Review, 37:2, 151–65.

- Brennan, Elliott. (2020). Coronavirus and Protest: How COVID-19 Has Changed the Face of American Activism. Sydney: United States Studies Centre.

- Caiani, Manuela. (2019). ‘The Rise and Endurance of Radical Right Movements’, Current Sociology, 67:6, 918–35.

- Carlsen, Hjalmar Bang, Jonas Toubøl, and Benedikte Brincker (2021). ‘On Solidarity and Volunteering During the COVID-19 Crisis in Denmark: The Impact of Social Networks and Social Media Groups on the Distribution of Support’, European Societies, 23:sup1, S122–S140.

- Castelli Gattinara, Pietro, Caterina Froio, and Andrea L. P. Pirro (2022). ‘Far‐Right Protest Mobilisation in Europe: Grievances, Opportunities and Resources’, European Journal of Political Research, 61:4, 1019–41.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2021). Covid-19: People with Certain Medical Conditions, available at https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html (accessed 18 June 2021).

- Chen, Cliff., Yung-Chi, Elena Byrne, and Tanya Vélez (2022). ‘Impact of the 2020 Pandemic of COVID-19 on Families with School-Aged Children in the United States: Roles of Income Level and Race’, Journal of Family Issues, 43:3, 719–40.

- Daphi, Priska, Sebastian Haunss, Moritz Sommer, and Simon Teune (2021). ‘Taking to the Streets in Germany – Disenchanted and Confident Critics in Mass Demonstrations’, German Politics, https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2021.1998459.

- della Porta, Donatella. (2022). The Protests Against Anti-Contagion Measures and Vaccination in Covid19 Times: Between Social Movement and Sectarian Dynamics Unpublished manuscript.

- Eichhorst, Werner, and Ulf Rinne (2020). IZA Covid-19 Crisis Response Monitoring: Germany (December 2020). Bonn: IZA Institute of Labor Economics.

- Engler, Sarah, Palmo Brunner, Romane Loviat, Tarik Abou-Chadi, Lucas Leemann, Andreas Glaser, and Daniel Kübler (2021). ‘Democracy in Times of the Pandemic: Explaining the Variation of Covid-19 Policies Across European Democracies’, West European Politics, 44:5–6, 1077–102.

- Gerbaudo, Paolo. (2020). ‘The Pandemic Crowd: Protest in the Time of Covid-19’, Journal of International Affairs, 73:2, 61–76.

- Giugni, Marco, and Maria T. Grasso (2019). Street Citizens: Protest Politics and Social Movement Activism in the Age of Globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Grande, Edgar, Swen Hutter, Sophia Hunger, and Eylem Kanol (2021). ‘Alles Covidioten? Politische Potenziale des Corona-Protests in Deutschland. Discussion Paper, ZZ 2021-601. Berlin: Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung.

- Grasso, Maria T., and Marco Giugni (2016). ‘Protest Participation and Economic Crisis: The Conditioning Role of Political Opportunities’, European Journal of Political Research, 55:4, 663–80.

- Grasso, Maria T., and Marco Giugni (2019). ‘Political Values and Extra-Institutional Political Participation: The Impact of Eco-Nomic Redistributive and Social Libertarian Preferences on Protest Behaviour’, International Political Science Review, 40:4, 470–85.

- Gurr, Ted Robert. (1970). Why Men Rebel. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Hale, Thomas, and Samuel Webster (2020). Oxford Covid-19 Government Response Tracker. Oxford: Blavatnik School of Government, available at https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/research-projects/coronavirus-government-response-tracker (accessed 18 June 2021).

- Hooghe, Marc, and Sofie Marien (2013). ‘A Comparative Analysis of the Relation Between Political Trust and Forms of Political Participation in Europe’, European Societies, 15:1, 131–52.

- Huebner, Mathias, Sevrin Waights, C. Katharina Spiess, Nico A. Siegel, and Gert G. Wagner (2020). ‘Parental Well-Being in Times of Covid-19 in Germany’, IZA Institute of Labor Economics, Discussion Paper No. 13556, 1–40.

- Hunger, Sophia, Teresa Völker, and Daniel Saldivia Gonzatti (2021). ‘Der Verlust der Vielfalt. Die Corona-Proteste in Deutschland werden durch eine radikale Minderheit geprägt’, WZB Mitteilungen, 172, 30–2.

- Hunger, Sophia, Eylem Kanol, Daniel Saldivia Gonzatti und, and Swen Hutter (2022). Better Off Alone Than in Bad Company? The (De)-Mobilizing Effect of Violence and Radical Right Involvement on Protest Support and Mobilization. Unpublished manuscript.

- Hutter, Swen. (2014). Protesting Culture and Economics in Western Europe: New Cleavages in Left and Right Politics. Ann Arbor: University of Minnesota Press.

- Jørgensen, Frederik, Alexander Bor, Marie Fly Lindholt, and Michael Bang Petersen (2021). ‘Public Support for Government Responses Against COVID-19: Assessing Levels and Predictors in Eight Western Democracies During 2020’, West European Politics, 44:5–6, 1129–58.

- Klandermans, Bert. (1984). ‘Mobilisation and Participation: Social-Psychological Expansions of Resource Mobilisation Theory’, American Sociological Review, 49:5, 583–600.

- Klandermans, Bert. (1997). The Social Psychology of Protest. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Klandermans, Bert, and Dirk Oegema (1987). ‘Potentials, Networks, Motivations, and Barriers: Steps Towards Participation in Social Movements’, American Sociological Review, 52:4, 519–31.

- Koos, Sebastian. (2021). Die ‘Querdenker’. Wer nimmt an Corona-Protesten teil und warum?: Ergebnisse einer Befragung während der ‘Corona- Proteste’ am 4.10.2020 in Konstanz. Working paper.

- Kowalewski, Maciej. (2021). ‘Street Protests in Times of COVID-19: Adjusting Tactics and Marching “as Usual’, Social Movement Studies, 20:6, 758–65.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, and Ioana-Elena Oana (2022). Protest in Unlikely Times: Dynamics of Collective Mobilization in Europe During the COVID-19 Crisis ‘Protest in Unlikely Times: Dynamics of Collective Mobilization in Europe During the COVID-19 Crisis’, Journal of European Public Policy, https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2022.2140819.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, Willem E. Saris, and Anchrit Wille (1993). ‘Mobilisation Potential for Environmental Protest’, European Sociological Review, 9:2, 155–72.

- Kurer, Thomas, Silja Häusermann, Bruno Wüest, and Matthias Enggist (2019). ‘Economic Grievances and Political Protest’, European Journal of Political Research, 58:3, 866–92.

- Lehmann, Pola, and Lisa Zehnter (2022). ‘The Self-Proclaimed Defender of Freedom: The AfD and the Pandemic’, Government and Opposition, https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2022.5.

- Marks, Gary, David Attewell, Liesbet Hooghe, Jan Rovny, and Marco Steenbergen (2022). ‘The Social Bases of Political Parties: A New Measure and Survey’, British Journal of Political Science, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123421000740.

- McAdam, Doug. (1982). Political Process and the Development of Black Insurgency, 1930-1970. Chicago, London: The University of Chicago Press.

- McAdam, Doug. (1986). ‘Recruitment to High-Risk Activism: The Case of Freedom Summer’, American Journal of Sociology, 92:1, 64–90.

- McAdam, Doug, John D. McCarthy, and Mayer N. Zald (1996). ‘Introduction: Opportunities, Mobilizing Structures, and Framing Processes – Toward a Synthetic, Comparative Perspective on Social Movements’, in Doug McAdam, John D. McCarthy and Mayer N. Zald (eds.), Comparative Perspectives on Social Movements. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1–20.

- McCarthy, John D., and Mayer N. Zald (1977). ‘Resource Mobilisation and Social Movements: A Partial Theory’, American Journal of Sociology, 82:6, 1212–41.

- McCarthy, John D., and Mayer N. Zald (2015). ‘Social Movement Organizations’, in Jeff Goodwin and James M. Jasper (eds.), The Social Movements Reader: Cases and Concepts. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 159–74.

- de Moor, Joost, Katrin Uba, Mattias Wahlström, Magnus Wennerhag, and Michiel de Vydt (2020). Protest for a Future II : Composition, Mobilization and Motives of the Participants in Fridays for Future Climate Protests on 20-27 September, 2019, in 19 Cities Around the World. Retrieved from http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:sh:diva-40271.

- Muis, Jasper, and Tim Immerzeel (2017). ‘Causes and Consequences of the Rise of Populist Radical Right Parties and Movements in Europe’, Current Sociology. La Sociologie Contemporaine, 65:6, 909–30.

- Nachtwey, Oliver, Robert Schäfer, and Nadine Frei (2020). Politische Soziologie der Corona-Proteste. Basel: Universität Basel.

- Neumayer, Eric, Katharina Pfaff, and Thomas Plümper (2021). Protest Against COVID-19 Containment Policies in European Countries. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3844989or.

- Norris, Pippa, Stefaan Walgrave, and Peter van Aelst (2005). ‘Who Demonstrates? Antistate Rebels, Conventional Participants, or Everyone?’, Comparative Politics, 37:2, 189–205.

- Oegema, Dirk, and Bert Klandermans (1994). ‘Why Social Movement Sympathizers Don’t Participate: Erosion and Nonconversion of Support’, American Sociological Review, 59:5, 703–22.

- Oliver, Pamela. (1984). ‘‘‘If You Don’t Do It, Nobody Else Will”: Active and Token Contributors to Local Collective Action’, American Sociological Review, 49:5, 601–10.

- Opp, Karl-Dieter. (1988). ‘Grievances and Participation in Social Movements’, American Sociological Review, 53:6, 853–64.

- Pinckney, Jonathan, and Miranda Rivers (2020). ‘Sickness or Silence: Social Movement Adaptation to Covid19’, Journal of International Affairs, 73:2, 23–42.

- Pleyers, Geoffrey. (2020). ‘The Pandemic Is a Battlefield. Social Movements in the COVID-19 Lockdown’, Journal of Civil Society, 16:4, 295–312.

- Plümper, Thomas, Eric Neumayer, and Katharina Gabriela Pfaff (2021). ‘The Strategy of Protest Against Covid-19 Containment Policies in Germany’, Social Science Quarterly, 102:5, 2236–50.

- Quaranta, Mario. (2014). ‘The “Normalisation” of the Protester: Changes in Political Action in Italy (1981–2009)’, South European Society and Politics, 19:1, 25–50.

- Regan, Patrick M., and Daniel Norton (2005). ‘Greed, Grievance and Mobilisation in Civil Wars’, Journal of Conflict Resolution, 49:3, 319–36.

- Rohlinger, Deana A., and David S. Meyer (2022). ‘Protest During a Pandemic: How Covid-19 Affected Social Movements in the United States’, American Behavioral Scientist, https://doi.org/10.1177/00027642221132179.

- Rovny, Jan., Ryan Bakker, Liesbet Hooghe, Seth Jolly, Gary Marks, Jonathan Polk, Marco Steenbergen, and Milada Anna Vachudova (2022). ‘Contesting Covid: The Ideological Bases of Partisan Responses to the Covid-19 Pandemic’, European Journal of Political Research, 61:4, 1155–64.

- Rüdig, Wolfgang, and Georgios Karyotis (2014). ‘Who Protests in Greece? Mass Opposition to Austerity’, British Journal of Political Science, 44:3, 487–513.

- Ruisch, Benjamin Coe., Courtney Moore, Javier Granados Samayoa, Shelby Boggs, Jesse Ladanyi, and Russel Fazio (2021). ‘Examining the Left–Right Divide Through the Lens of a Global Crisis: Ideological Differences and Their Implications for Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic’, Political Psychology, 42:5, 795–816.

- Stekelenburg, Jacquelien van, and Bert Klandermans (2013). ‘The Social Psychology of Protest’, Current Sociology, 61:5-6, 886–905.

- Stürmer, Stefan, and Bernd Simon (2004). ‘Collective Action: Towards a Dual-Pathway Model’, European Review of Social Psychology, 15:1, 59–99.

- Teune, Simon. (2021a). ‘Zusammen statt nebeneinander. Die Proteste gegen die Corona-Maßnahmen und die extreme Rechte’, Demokratie gegen Menschenfeindlichkeit, 5:2, 114–8.

- Teune, Simon. (2021b). ‘Querdenken und die Bewegungsforschung – neue Herausforderung oder Déjà-Vu?’, Forschungsjournal Soziale Bewegungen, 34:2, 326–34.

- Torcal, Mariano, Toni Rodon, and María José Hierro (2016). ‘Word on the Street: The Persistence of Leftist-Dominated Protest in Europe’, West European Politics, 39:2, 326–50.

- Traber, Denise, Lukas F. Stoetzer, and Tanja Burri (2023). ‘Group-Based Public Opinion Polarisation in Multi-Party Systems’, West European Politics. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2022.2110376

- Walker, Andrew. (2021). Covid Contraction Shrinks German Economy by 5%. BBC News. January 14, 2021.

- Walsh, Edward J. (1981). ‘Resource Mobilisation and Citizen Protest in Communities around Three Mile Island’, Social Problems, 29:1, 1–21.

- Wiltfang, Gregory L., and Doug McAdam (1991). ‘The Costs and Risks of Social Activism: A Study of Sanctuary Movement’, Social Forces, 69:4, 987–1010.

- Zajak, Sabrina, Katarina Stjepandić, and Elias Steinhilper (2021). ‘Pro-Migrant Protest in Times of COVID-19: Intersectional Boundary Spanning and Hybrid Protest Practices’, European Societies, 23:1, 172–183.

- Zimmermann, Bettina M., Amelia Fiske, Stuart McLennan, Anna Sierawska, Nora Hangel, and Alena Buyx (2022). ‘Motivations and Limits for COVID-19 Policy Compliance in Germany and Switzerland’, International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 11:8, 1342–53.

- van der Zwet, Koen, Ana I. Barros, Tom M. van Engers, and Peter Sloot (2022). ‘Emergence of Protests During the Covid-19 Pandemic: Quantitative Models to Explore the Contributions of Societal Conditions’, Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 9:1, 1–11.