?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study investigates how nationality and partisanship, two personal attributes of Commissioners, influence member states’ bargaining success in EU law making. Building on principal-agent theory, it is expected that countries with close national and political linkages to the Commissioner responsible for negotiating a proposal are more successful in attaining their preferred outcomes. The hypotheses are tested using a linear regression model on the DEUIII dataset. Overall, the analysis demonstrates that a state has more bargaining success when the responsible Commissioner comes from that state or is affiliated with the same European Parliament party group as one of the governing parties in that state. Moreover, shared national ties moderate the detrimental effect of preference disagreements with the Commission on states’ success. The study contributes to the literature by showing that Commissioners are not independent but political actors who can act autonomously and successfully pursue the preferences of their home countries and parties.

Having been appointed as a Member of the European Commission by the European Council (…) I solemnly undertake: (…) to be completely independent in carrying out my responsibilities, in the general interest of the Union; in the performance of my tasks, neither to seek nor to take instructions from any Government or from any other institution, body, office or entity (…). I formally note the undertaking of each Member State to respect this principle and not to seek to influence Members of the Commission in the performance of their tasks.Footnote1

In the European Union, legislative acts are primarily negotiated between the Council and the European Parliament (EP), while the European Commission is responsible for drafting legislation. However, this does not imply that the Commission cannot influence bargaining outcomes, or that its role is limited to agenda-setting (Kreppel and Oztas Citation2017). The Commission’s representatives attend the Council’s working groups and EP committees, and also participate in trilogues – informal meetings where delegates of the Council, EP and Commission craft provisional agreements on legislative proposals that are then formally approved by the Council and the EP (see Laloux Citation2020). Consequently, the Commission can influence both the internal positions of these institutions and final outcomes in line with its preferences. Previous studies have confirmed that the Commission has a say in EU legislative negotiations, as both member states and the EP attain more bargaining success when their preferences align with those of the Commission (Arregui Citation2016; Costello and Thomson Citation2013; Cross Citation2013; Lundgren et al. Citation2019).

However, the Commission is not a unitary actor, but is composed of Commissioners. These individuals are nominated by the member states and assigned specific portfolios (Hartlapp et al. Citation2014). While the Commission’s decisions are made collectively in the College of Commissioners and all Commissioners are collectively responsible for the Commission’s actions, they enjoy some discretion when drafting and negotiating legislative proposals in the areas within their jurisdictions (Wonka Citation2008). Accordingly, earlier research has investigated how their characteristics and resources, such as age, experience, expertise, or the size of the Directorates-General (DGs) they lead, affect the content of the proposal (Bürgin Citation2017; Hartlapp et al. Citation2014; Rauh Citation2019), the amount of discretionary power granted for the implementation of EU legislation (Ershova Citation2019), or the Commission’s legislative success (Bailer Citation2014; Laloux and Panning Citation2021; Rauh Citation2021).

However, Article 17 TEU and Article 245 TFEU emphasise that Commissioners are required to be completely independent in performing their duties and act in Europe’s interests rather than representing their states. Nevertheless, previous studies have shown that Commissioners are not independent Europeanists and technocrats, but rather politicians with strong connections to their home countries and political parties. For example, Killermann (Citation2016) found that member states’ governments are less likely to vote against a proposal coming from a Commissioner with whom they share national and political ties. Thomson (Citation2008a) and Thomson and Dumont (Citation2022) demonstrated that there is relatively high congruence between the policy positions taken by the Commission and the home country of the responsible Commissioner. Gehring and Schneider (Citation2018) found a significant positive relationship between the nationality of the Commissioner for Agriculture and the share of agricultural funds obtained by his/her country. Other analyses have shown that due to the Commission’s heightened importance over time, states have increasingly appointed high-profile politicians as Commissioners in order to influence the Commission’s preferences (Döring Citation2007; Hartlapp et al. Citation2014; Hug Citation2003; Wonka Citation2007).

If Commissioners are agents of national governments made up of specific political parties, they are expected to defend the interests of their home member states and parties during negotiations on EU legislative proposals. As a result, their personal attributes, especially nationality and partisanship, are likely to influence their member states’ bargaining success in the EU legislative process. A number of studies have addressed the question of what determines states’ bargaining satisfaction in the EU (Arregui Citation2016; Arregui and Thomson Citation2009; Bailer Citation2004; Cross Citation2013; Golub Citation2012; Hosli Citation2000; Kirpsza Citation2023; Lundgren et al. Citation2019; Mariano and Schneider Citation2022). Yet, none of them have examined the effect of Commissioners’ personal attributes on member states’ preference attainment.

This study seeks to fill this gap by investigating how shared national and political ties with a Commissioner influence EU member states’ bargaining success. Building on principal-agent theory, it is expected that a state is more successful in attaining its most preferred outcomes when (1) the Commissioner responsible for the proposal comes from that state, and (2) he/she is a member of the same EP party group as at least one of the parties forming the government in that state. The study also hypothesises that sharing national and political ties with a Commissioner is particularly beneficial to countries whose preferences diverge from those of the Commission. The hypotheses were tested using a linear regression model on the Decision Making in the EU (DEUIII) dataset, which covers 141 key legislative proposals introduced and decided between 1996 and 2019 (Arregui and Perarnaud Citation2022).

Overall, the analysis reveals that sharing national and political ties with Commissioners increases states’ bargaining success, while national proximity also moderates the detrimental effect of disagreement with the Commission’s preferences. However, the effect of a Commissioner’s nationality and partisanship on states’ bargaining satisfaction varies with the Commissioner’s gender, political experience, and the experience of his/her country in the EU. The study thus contributes to the literature on EU decision making by showing that (1) Commissioners’ personal attributes, especially their nationality and partisanship, are relevant drivers of states’ bargaining success in the EU; (2) member states exploit the advantage of having their ‘own’ Commissioner to pursue their national interests, even when their positions differ substantially from the preferences of the entire Commission; and (3) Commissioners are the political agents of their home countries rather than technocratic and independent actors in the inter-institutional bargaining stage, as they can deviate from the Commission’s position and influence policy outcomes in line with their states’ preferences.

Theorising the effect of Commissioners’ attributes on member states’ bargaining success

This section theorises the impact of Commissioners’ attributes on member states’ bargaining success in EU law making. A starting assumption is that the process of appointing members of the Commission can be conceptualised through the lens of principal-agent theory, where member states are the principals who delegate their authority to Commissioners who serve as their agents (Pollack Citation2003). Each state nominates one Commissioner, and the full list of candidates is accepted by the Council in agreement with the previously elected Commission’s President. The proposed College of Commissioners is then appointed by the European Council after receiving approval from the EP. The appointment procedure outlined above reveals that member states enjoy a considerable degree of discretion when nominating their Commissioners. Even if a government’s candidate is rejected by the Council or Parliament, only that government has the right to propose another nominee. Therefore, member states ‘are in the driver’s seat during the nomination and appointment process of the Commission’ (Wonka Citation2007: 178).

Member states can exploit their nomination powers to influence Commission policies in line with their preferences. Accordingly, they can appoint particular types of Commissioners who will be more controllable and more likely to advance their interests in this institution. Earlier research has demonstrated that when national governments nominate candidates for Commission posts, they consider the nominees’ personal characteristics and political activities, and tend to select politicians who are more visible and high-ranking, have had past careers in national politics, and share a government’s party affiliation (Döring Citation2007; Hartlapp et al. Citation2014; Wonka Citation2007). In light of principal-agent theory, careful screening and selection of candidates allow member states to reduce the risk of choosing disloyal delegates and agency slack. This increases the probability that the appointed Commissioners will advance their national interests if required to do so. Moreover, governments hold the resources to reward loyal Commissioners with re-nomination or high-profile appointments after they leave the Commission. These prospects should therefore enhance the Commissioners’ propensity to advance their home countries’ preferences, since many of them pursue national careers after serving on the Commission (Vaubel et al. Citation2012).

Based on these arguments, I expect that shared national ties between member states and Commissioners not only affect the contestation of legislative acts in the Council or the content of legislative proposals, as found by Killermann (Citation2016), Thomson (Citation2008a) and Thomson and Dumont (Citation2022), but also states’ bargaining success. Specifically, a state is assumed to be more successful in attaining its most preferred outcome when the Commissioner responsible for negotiating the proposal comes from that state. The reason is that Commissioners and their delegates are involved in decisive legislative deliberations on both intra- and inter-institutional levels, and are thus able to impact legislative outcomes in line with their home countries’ preferences. On the intra-institutional level, they attend the meetings of Council working groups and EP committees, exerting noticeable influence on these institutions’ policy positions. This is evidenced by Egeberg (Citation1999: 468), who found that 63% of national officials in Council groups give substantial consideration to the Commission’s positions; and Rasmussen (Citation2003: 9), who demonstrated that in most cases, the Council follows the Commission’s opinions on amendments. On the inter-institutional level, Commissioners and their subordinates (e.g. directors-general or heads of units) participate in secluded trilogues, where representatives of the Council, EP and Commission negotiate a compromise text, which is then typically rubberstamped by the Council and the EP without any further amendment (Panning Citation2021; Roederer-Rynning and Greenwood Citation2015, Citation2021). Given that trilogues play a pivotal role in the adoption of almost 90% of EU legislation (Roederer-Rynning and Greenwood Citation2015: 1148), Commissioners gain substantial leverage when determining final policy outcomes. Hence, they can successfully capitalise on their powerful positions in intra- and inter-institutional negotiations to promote their home countries’ preferences. Therefore:

H1: A member state has more bargaining success when the responsible Commissioner comes from that member state.

Second, party ideology plays a major role in EU law making. With regard to the Council, Kreppel (Citation2013) demonstrated that there are substantial variations in the ideological preferences of ministers across different policy areas and within member state delegations to this institution. It has also been found that governments are more likely to vote together with those of the same ideological affiliation (Hagemann and Høyland Citation2008), while both the left-right and EU integration positioning of governments determine their likelihood of casting a contesting vote on EU legislation (Hagemann et al. Citation2017; Hosli et al. Citation2011). It must be noted, however, that the literature is inconsistent in this respect, as there are also studies suggesting that decision making in the Council is driven by domestic economic interests rather than ideological factors (Bailer et al. Citation2015; Kudrna and Wasserfallen Citation2021). As for the Parliament, existing research has demonstrated that voting behaviour and coalition formation in this institution fall predominantly along the left-right dimension (Hix et al. Citation2007). In the context of inter-institutional relationships, Hagemann and Høyland (Citation2010) showed that divisions over legislation in the Council fall along the left-right dimension and cause the EP to split along this ideological dimension as well. Given that party politics determine policy outcomes, Commissioners need to accommodate the respective parties’ preferences to ensure they have the required support for the adoption of their proposals within the Council and the EP. Accordingly, they are expected to advance the interests of national parties affiliated with their EP political group, resulting in a higher degree of bargaining success for the member states’ governments represented by those parties at the time of decisive negotiations on proposals. Thus:

H2: A member state has more bargaining success when the responsible Commissioner belongs to the same EP party group as at least one of the parties in that state government.

Nevertheless, if national and political linkages between member states and Commissioners are as strong as expected, then the latter are likely to deviate from the College’s instructions and promote the preferences of their home states and party groups in the bargaining phase, even if these preferences differ substantially from those of the entire Commission. The EU bargaining stage offers great opportunities to escape the College’s control and act autonomously, since negotiations within the Council and in trilogues are secluded, informal and less controllable for the principals (Brandsma Citation2019; Laloux and Delreux Citation2018). Given that Commissioners can successfully influence negotiation outcomes, as assumed when formulating H1, their advocacy should be particularly beneficial for member states that hold positions further from those of the Commission, but at the same time share national and political ties with the responsible Commissioner. Along this line, it is thus expected that both shared nationality and partisanship with a Commissioner mitigate the negative effect of holding preferences that diverge from those of the Commission on member states’ bargaining success. Therefore, the following two hypotheses are proposed:

H3a: Shared national ties with the responsible Commissioner moderate the detrimental effect of disagreement with the Commission on member states’ bargaining success.

H3b: Shared political ties with the responsible Commissioner moderate the detrimental effect of disagreement with the Commission on member states’ bargaining success.

Furthermore, the Commissioners’ ability to advance the interests of member states that share national and partisan ties with them may be strengthened or weakened by other factors. For example, Commissioners with prior national political experience should be better positioned to shape negotiation outcomes in the direction these states want, than those with no such experience (Bailer Citation2014; Rauh Citation2021). The same applies to Commissioners with portfolio-specific expertise, as they can use their informational advantages to champion specific solutions (ibid.). Likewise, male Commissioners are expected to be more successful in pursuing national and partisan interests than female Commissioners, since earlier research shows that due to gender differences in negotiation, men negotiate more assertively and competitively, thereby achieving better outcomes than women (Mazei et al. Citation2015). Finally, Commissioners from the new member states should deliver better outcomes to countries sharing national and partisan ties with them than Commissioners from the old members, as the former may not be fully socialised to defend supranational or Commission’s interests due to the shorter duration of their countries’ EU membership. With that, I expect the effect of a Commissioner’s nationality and partisanship on states’ bargaining success to be conditional on the Commissioners’ age, gender, political experience, policy expertise, and their countries’ experience in the EU.

Research design

The data

In order to test my hypotheses, I drew on the DEUIII dataset (Arregui and Perarnaud Citation2022). It was collected through semi-structured interviews with key decision-makers, and includes 363 controversial issues relating to 141 politically important EU legislative proposals. These proposals were decided between 1996 and 2019 under the consultation (currently the special legislative procedure) or the co-decision procedure (currently the ordinary legislative procedure). For each issue, DEUIII contains information about (1) the policy positions of individual member states, the EP and the Commission; (2) the importance attached by those actors to the issues; and (3) the negotiation outcome, all reported on a scale from 0 to 100.

Since the DEU dataset includes issues as observations, I transformed it to obtain each state’s policy positions on each issue as observations. Hence, the unit of analysis is the member state’s position*outcome dyad within each issue. After excluding missing cases, the final dataset includes 5,237 observations (dyads) across 304 issues. The time frame for the analysis is from 1996 to 2019, thus covering five Commissions: Santer (1995–1999), Prodi (1999–2004), Barroso I (2004–2009), Barroso II (2009–2014) and Juncker (2014–2019).Footnote2

Dependent and independent variables

The dependent variable is Bargaining success, which measures member states’ preference attainment spatially as the absolute distance between a state’s policy position and the decision outcome on each issue, weighted by the salience each state attaches to the issue:

where i – a member state; j – an issue; Pij – a position of a state i on an issue j measured on a scale from 0 to 100; Outcomej – the outcome on an issue j on a scale of 0–100; Sij – the salience attached by a state i to an issue j, measured on the 0–100 scale. In the literature, this saliency-weighted operationalisation is considered to have advantages over alternative measures of bargaining success (Arregui Citation2016; Cross Citation2013; Golub Citation2012). As Golub (Citation2012: 1300–1301) emphasised: ‘(…) to determine how much states differ in translating their strongly held preferences into EU policy we need to build salience directly into the dependent variable’. The reason is that states value each issue differently; therefore, they can attain different levels of bargaining success when their policy positions are equally distant from the outcome, while attaching different levels of salience. The dependent variable ranges from 0 to 100, where higher scores indicate a larger salience-weighted distance from the outcome and therefore a lower degree of bargaining success.

To test H1, I created a dichotomous variable, Nationality, which equals 1 if the responsible Commissioner comes from a given member state, and 0 if otherwise. A Commissioner’s nationality was identified via Eur-Lex and the EP’s Legislative Observatory at the stage of decisive negotiations, either at the time of the key trilogues during which the final legislative text was agreed and then formally approved, or at the time of a formal conclusion when trilogues did not occur.

The dichotomous Partisanship variable was coded to test H2. It equals 1 when the responsible Commissioner and at least one of the parties in a state government are members of the same EP political group, and 0 if otherwise. Information on the Commissioners’ political affiliations and government composition was gathered from Döring (Citation2007) and the ParlGov database (Döring and Manow Citation2022), respectively. As in the case of nationality, political ties between member states and Commissioners were measured at the time of decisive negotiations.

H3a and H3b on the conditioning effect of a Commissioner’s nationality and political affiliation were tested with two interactions: (a) Nationality*Distance to COM, and (b) Partisanship*Distance to COM. The Distance to COM variable measures the absolute distance between the policy positions of a state and the Commission on an issue. It ranges from 0 to 100, where higher values correspond to greater divergence between their preferences. The literature argues that states with positions more distant from the Commission attain lower bargaining success (cf. Arregui Citation2016); however, I expect this relationship to be moderated by shared national and political ties with the responsible Commissioner.

In order to investigate the conditional effect of a Commissioner’s nationality and partisanship on states’ bargaining success, I constructed five additional variables. Age measures the age of a Commissioner at the time of decisive negotiations on a proposal. Female is coded as 1 for female Commissioners and 0 for male Commissioners. Political experience informs if the responsible Commissioner was (1) or not (0) a national minister before he/she took office. Expertise is equal to 1 if a Commissioner has portfolio-specific expertise, and 0 if otherwise. To operationalise this expertise, I checked if a Commissioner possessed an educational or professional background that was relevant for the portfolio he/she held. Finally, New MS takes the value of 1 for Commissioners from states that joined the EU in 2004 and later, and 0 for those from the old member states. After coding the above variables, I interacted each of them with Nationality and Partisanship.

Control variables

The analysis also includes several control variables. Earlier studies have found that states with extremist preferences have less bargaining success (e.g. Arregui Citation2016; Bailer Citation2004; Lundgren et al. Citation2019). Therefore, I constructed the variable Extremity, which measures the absolute distance between each state’s position and the average position of the other member states.

The proximity to the EP’s position can also affect states’ bargaining success (cf. Arregui Citation2016; Cross Citation2013). Hence, I created the Distance to EP variable, measuring the absolute distance between the positions taken by the EP and each member state.

The literature on EU decision making often posits that larger countries have more bargaining success as they hold more economic resources and wield greater voting power, thus being better positioned to influence other actors and build winning and blocking coalitions in the Council (Arregui and Thomson Citation2009; Cross Citation2013). Therefore, using the Eurostat data, I constructed the Population variable, measuring each country’s population (in millions) as a proxy for member state power and size.

The Council Presidency is another power resource that enables states to influence policy outcomes. During its six-month term, a state holding the chair structures the legislative agenda, drafts compromise proposals, has privileged access to information, and represents the Council in trilogues. These advantages offer opportunities for the state at the helm to advance its domestic interests (Cross and Vaznonytė Citation2020; Häge Citation2017; Thomson Citation2008b; Vaznonytė Citation2020). Thus, I created a dichotomous Presidency variable, which equals 1 for member states serving as the Presidency when a legislative act is adopted, and 0 for other countries. I refer to the adoption stage since Thomson (Citation2008b) found that finalising presidents were more successful than other presidents and non-presidents.

The fifth control variable, Positions taken, measures the percentage of issues on which a state took a position. This variable stems from the fact that member states have different ranges of interests and are not equally affected by all EU policies. As a result, they sometimes do not take a position on an issue because it has little or no relevance to their utility. With that, I expect states with fewer policy positions to achieve more bargaining success because they can concentrate their negotiation resources on fewer issues that they care most about.

Bargaining success may also vary with the legislative instruments. EU secondary law mainly covers two types of legal acts: regulations and directives. According to Article 288 TFEU, regulations are ‘binding in its entirety and directly applicable in all Member States’, while directives are ‘binding, as to the result to be achieved, upon each Member State to which it is addressed, but shall leave to the national authorities the choice of form and methods’. Since directives give the member states more flexibility, allowing them to accommodate their national regulatory peculiarities and domestic stakeholder interests during the transposition stage, I expect states to be more successful when adopting these instruments. Thus, Directive equals 1 for directives and 0 for regulations and decisions.

Issues captures the dimensionality of a proposal by measuring the number of conflicting issues negotiated within each proposal. More issues are expected to increase states’ bargaining success, as the availability of multiple issues creates opportunities for gains from legislative exchange, enabling member states to trade their support for their most preferred issues.

Finally, since the effect of a Commissioner’s nationality and partisanship may vary across policy fields (Killermann Citation2016), I control for the proposal’s policy area using the primarily responsible Commission’s Directorate-General as a proxy.

Empirical analysis

Bivariate analysis

As a first step, I performed a bivariate analysis. compares the average bargaining success attained by member states that do or do not share national and political ties with the responsible Commissioner, measured as the average salience-weighted distance between their positions and final outcomes. Starting with nationality, the average salience-weighted distance from the outcome for member states that share national ties with a Commissioner (18.17) is about 2.5 points lower than that for countries without such ties (20.70). A t-test comparing these means yields a statistically significant result (p = 0.047), demonstrating that there is a significant difference between these two groups. This lends support to H1 that sharing nationality with a Commissioner increases states’ bargaining success. With regard to political ties, the average salience-weighted distance between states’ positions and outcomes is about 1.5 points lower for countries with at least one of the governing parties coming from the same EP party group as the responsible Commissioner (19.86), compared to states without such political connections (21.36). Again, a t-test reveals that there is a significant difference in bargaining success between the two groups (p = 0.013). This result is thus consistent with H2 that political ties shared with a Commissioner translate into higher success.

Table 1. Average states’ bargaining success by Commissioner nationality and partisanship.

Multivariate analysis

In the second step, I conducted a multivariate analysis by employing multiple linear regression. Given that the data structure is hierarchical, where state-level observations of bargaining success are nested within issues, I used robust standard errors clustered by issue, following the approach used in previous studies (Arregui and Thomson Citation2009; Cross Citation2013; Golub Citation2012; Rasmussen and Reh Citation2013). presents the regression results. It should be recalled that a negative coefficient indicates a decrease in the distance between a state’s position and the outcome, and thus an increase in bargaining success. Overall, three groups of regression models are estimated. Models 1 A, 1B and 1 C only analyse the effect of the Commissioner’s nationality; Models 2 A, 2B and 2 C examine the individual influence of political ties with the Commissioner, while Models 3 A, 3B and 3 C investigate both of these effects together. Within each group of models, Model ‘A’ includes only the independent variables, Model ‘B’ adds control variables to Model ‘A’, and Model ‘C’ incorporates all independent variables, control variables, and the interaction terms. In the Online Appendix, I reported a series of robustness checks with policy area and member state fixed-effects.

Table 2. Regression results.

Consistent with H1, a state is more successful in attaining its most preferred outcome when the responsible Commissioner comes from that state. The coefficient associated with the Nationality variable is negative and significant across all models, even when considering the control variables (Model 1B) and Partisanship (Models 3 A and 3B). In substantive terms, when the Commissioner comes from a given state, its salience-weighted distance from the outcome decreases by an average of 2.32 scale points (based on Model 1B). The discussed effect also holds after controlling for the proposal’s policy area (see Tables E and G in the Online Appendix). More specifically, member states sharing national ties with the responsible Commissioner attain more bargaining success than those without such linkages in all policy fields except energy and transport, judicial and home affairs, general secretariat, and education and culture (see Figure A in the Online Appendix). This finding indicates that member states can exploit their ‘own’ Commissioners to increase bargaining satisfaction, while Commissioners are capable of successfully promoting their home countries’ preferences.

Sharing partisan ties with the responsible Commissioner also increases states’ bargaining success. The effect of Partisanship is negative and significant at the 5% level in Models 2 A and 2B. This effect also remains significant when considering Nationality in Models 3 A and 3B. Based on Model 2B, when the Commissioner and at least one of the parties in a state’s government come from the same party group, the distance between that state’s policy position and the outcome decreases by 1.17 salience-weighted points. Using the EJPR Political Data Yearbook, I also investigated if the influence of a Commissioner’s partisanship was associated with the number of government ministers held by parties belonging to his/her EP party group (see Table D in the Online Appendix). The results reveal a negative and significant relationship, thus indicating that holding more cabinet posts by parties coming from the same EP party group as the responsible Commissioner increases states’ bargaining success. In sum, the above findings demonstrate that not only national but also political ties with the responsible Commissioner are relevant predictors of states’ bargaining success in the EU. Thus, this analysis corroborates H2.

However, when controlling for policy fields, the effect of Partisanship loses its significance (Tables E and G in the Online Appendix). A closer inspection suggests that states with political ties to Commissioners have visibly more bargaining success than those without such linkages in only five of the sixteen policy areas under investigation, including enterprise and industry, agriculture, health, and external relations (Figure B in the Online Appendix). While this finding indicates that the importance of partisanship varies across policy fields, it also signifies that in some policy areas, member states can capitalise on their political ties with Commissioners to achieve better policy outcomes.

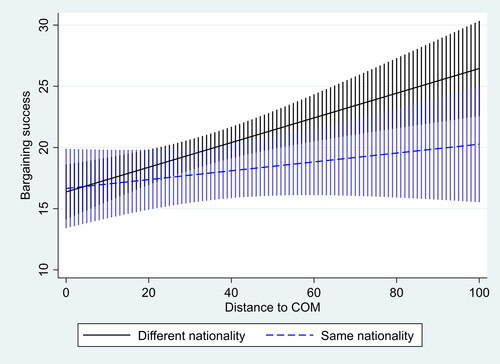

In the previous section, I hypothesised that the effect of the Commissioner’s nationality and partisanship is stronger when a state holds divergent preferences with the Commission (H3a and H3b). The analysis confirms this expectation, but only for national ties. As indicated by the positive and highly significant coefficient of the Distance to COM variable, states’ bargaining success generally decreases as the distance between their positions and those of the Commission increases, reflecting previous findings (cf. Arregui Citation2016). Interestingly, however, the interaction term between this variable and Nationality has the opposite and significant effect in Models 1 C and 3 C, revealing a clear and expected moderating effect of the Commissioner’s nationality on disagreement with the Commission. illustrates this effect. Overall, as the preference divergence between a state and the Commission increases, that state attains a higher level of bargaining success when it has national ties with the responsible Commissioner than when it does not. Therefore, while holding divergent positions with the Commission is generally disadvantageous for bargaining success, member states can visibly mitigate this negative effect by taking advantage of their ‘own’ Commissioners responsible for the proposal. The analysis thus supports Hypothesis 3a.

Figure 1. Interaction effect between the Commissioner’s nationality and states’ alignment with the Commission’s policy position (based on Model 1C).

By contrast, sharing political ties with the responsible Commissioner does not moderate the detrimental effect of disagreement with the Commission on states’ bargaining success. The coefficient of the interaction Partisanship*Distance to COM has the expected negative direction, but is insignificant in Models 2 C and 3 C. This implies that while having an ‘own’ Commissioner is advantageous in terms of bargaining success when a state’s preference differs substantially from that of the Commission, this relationship does not hold for Commissioners sharing political ties with states’ governing parties. Thus, the analysis does not support H3b.

In the theoretical section, I argued that the impact of a Commissioner’s nationality and partisanship varies with specific conditions. To inspect that claim, I conducted additional regression analyses where I investigated the effect of these two attributes on states’ bargaining success conditional on the Commissioner’s age, gender, political experience, policy expertise, and the experience of his/her home country in the EU. The results are presented in Table H in the Online Appendix, and are as follows: First, as opposed to male Commissioners, female Commissioners are less successful in pursuing the interests of member states that share partisan ties with them. Interestingly, however, member states are found to attain a higher level of average bargaining success when the responsible Commissioner is female rather than male, regardless of whether those states share national or partisan ties with the Commissioner. Second, as expected, a Commissioner’s prior national political experience matters for bargaining success. A member state benefits substantively more from having its ‘own’ Commissioner when that Commissioner previously held a ministerial portfolio. Third, Commissioners from the new member states are more successful in advancing their home countries’ preferences than those from the old member states. Fourth, contrary to expectations, no evidence was found that the age and policy expertise of the Commissioners influence their ability to successfully promote the preferences of their home countries or parties. Overall, the above findings confirm that the impact of a Commissioner’s nationality and partisanship on states’ bargaining success is not straightforward, but rather conditional on other attributes of individual Commissioners, including their gender, political experience, and country of origin.

Turning to the control variables, Extremity is positive and significant across models, reflecting previous findings that states with more extreme preferences are less successful in attaining their preferred outcomes (e.g. Kirpsza Citation2023). Furthermore, a member state achieves more bargaining success when its position is closer to the EP’s position. Holding the Council Presidency during the final stages of the legislative proceedings also increases states’ bargaining success, mirroring earlier findings (Thomson Citation2008b). Positions taken is positive and significant, suggesting that member states that take policy positions on a higher proportion of issues achieve lower bargaining success than those that focus their attention on a narrow range of issues (see Golub Citation2012). Finally, Directive is negative and significant, suggesting that member states are more likely to succeed when a directive is negotiated.

By contrast, member states with larger populations are not associated with greater or lesser success. This null finding aligns with earlier research showing that states’ power resources are not relevant drivers of bargaining success in the EU (Arregui Citation2016; Lundgren et al. Citation2019). Similarly, the coefficient of Issues is not significant in any model, indicating that the availability of multiple issues does not influence states’ bargaining success.

Qualitative examples

While the quantitative findings corroborate my central expectations, it is also worth enriching them with qualitative evidence. This section therefore offers two illustrative examples, where shared nationality and partisanship with the responsible Commissioner potentially contributed to states’ bargaining success.

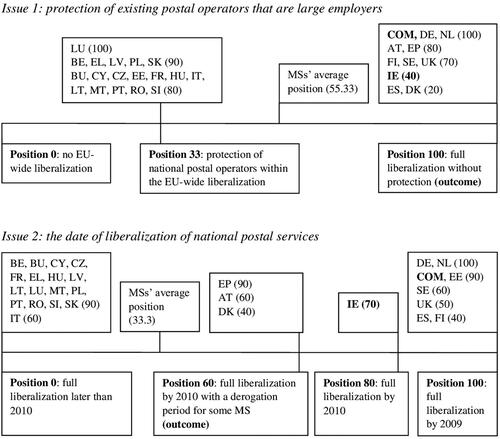

The first example relates to the directive on postal services adopted in 2008. The proposal was presented by the Commission in 2006 and its objective was to accomplish the EU internal market of postal services by 2009. The proposed directive raised two controversial issues. The first concerned the level of protection of national postal companies that are large employers, while the second one pertained to the timing of liberalisation of national postal markets. Actors were split into two camps on both issues, as depicted in (see also Thomson Citation2011: 139–142). The Commission and member states that had already liberalised their postal services, i.e. northern countries and Germany, supported the full market opening by 2009 without any protection for the national postal operators (position 100). On the opposite side were countries that had not opened their postal markets, including Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, and the new member states. They favoured postponing full liberalisation beyond 2010 without specifying its exact date, and wanted their large national postal providers to be protected within the EU-wide liberalisation.

Figure 2. Actors’ preferences regarding the directive on postal services.

Notes: Salience levels are in parentheses. EP: European Parliament, COM: Commission, AT: Austria, BE: Belgium, CY: Cyprus, CZ: Czechia, DE: Germany, DK: Denmark, EE: Estonia, EL: Greece, ES: Spain, FI: Finland, FR: France, HU: Hungary, IE: Ireland, IT: Italy, LT: Lithuania, LU: Luxembourg, LV: Latvia, MT: Malta, NL: The Netherlands, PL: Poland, PT: Portugal, SE: Sweden, SI: Slovenia, SK: Slovakia, UK: United Kingdom.

Source: Arregui and Perarnaud (Citation2022).

For the Commission, the proposal was led by Charlie McCreevy, the Commissioner for Internal Market and Services from Ireland. Before taking the Commissioner’s office, he was a politically experienced and seminal figure in national politics, having served various high-level government posts, including Minister for Social Welfare (1992–1993), Minister for Tourism and Trade (1993–1994), and Minister for Finance (1997–2004). In addition, during his term as a Commissioner, McCreevy was accused by László Kovács, the Hungarian Commissioner for Taxation and Customs Union, of advancing the national interests of Ireland (Kubosova Citation2007). Based on the above observations and previous empirical findings, one can thus expect Ireland to benefit substantively from having its ‘own’ Commissioner when deciding on the proposal under consideration.

Indeed, confirms this expectation. First, the policy positions of the Commission and Ireland were considerably close on both issues, suggesting that the initial proposal led by Commissioner McCreevy was in line with his country’s preferences. This significantly strengthened Ireland’s negotiating position as research showed that the Commission’s support substantively increases actors’ bargaining success (cf. Kirpsza Citation2023; Lundgren et al. Citation2019). Second, Ireland emerged as one of the most successful countries in the negotiations over this proposal. On the first issue, its policy position perfectly overlapped with the outcome, while on the second issue it was only 14 salience-weighted points away from it. In total, Ireland attained an average weighted bargaining success score of 7, and only two countries, Austria and Denmark, fared better (0).

The postal services case was not the only one where Ireland benefitted from having McCreevy as its Commissioner. In my analysis, he was responsible for two legislative proposals that raised a total of six controversial issues. Ireland attained high average bargaining success on those issues (18.67), ranking with Denmark (16.3) and Finland (14) as being among the three most successful countries. Furthermore, on five of the six issues in the data, the positions of Ireland and the Commission were identical (position 100), indicating that the initial proposals led by Commissioner McCreevy generally reflected Ireland’s preferences. Hence, there are solid grounds to claim that this country enjoyed a clear dividend from having its ‘own’ Commissioner at the proposal and negotiation stage.Footnote3

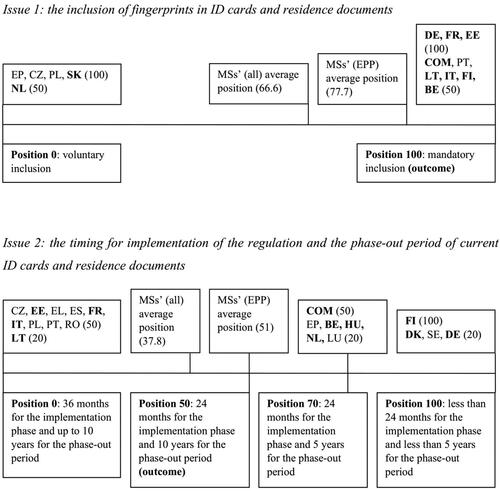

The second example concerns the Regulation on strengthening the security of identity cards and residence documents issued by the EU member states. The Commission submitted this proposal in April 2018, while the Council and the EP adopted it in June 2019. This legislative act generated two controversial issues, as depicted in . The first was the inclusion of fingerprints in identity cards. The Commission and most member states, notably France and Germany, called for the compulsory introduction of those biometric traits (position 100), while four countries, supported by the EP, opposed that measure, claiming that it was disproportionate in terms of data protection (position 0). The outcome was in line with the first group’s position. The second issue concerned the timing for implementation of the proposal and the phasing-out period of current ID cards not meeting security standards. The Commission proposed 24 months for implementation and 5 years for phasing-out (position 70), which was supported by the EP, Hungary, and the Benelux countries. Most member states, including France, Italy, Poland, and Spain, called for longer time periods (position 0), arguing that it was almost impossible to replace millions of ID cards held by EU citizens within such a short time. The opposite position was taken by Germany and the Nordic countries, which favoured reducing the Commission’s time limits (position 100). The outcome was in the middle of the policy spectrum, envisaging the 24-month date of application and the 10-year phasing-out period (position 50).

Figure 3. Actors’ preferences regarding the regulation on the security of identity cards and residence documents.

Notes: Salience levels are in parentheses. Member states with at least one of the governing parties belonging to the EPP are in bold.

Source: Arregui and Perarnaud (Citation2022).

The Commissioner responsible for this proposal was Dimitris Avramopoulos, the Commissioner for Migration, Home Affairs, and Citizenship nominated by Greece. Like Commissioner McCreevy, he was a heavyweight national politician with prior political experience as Minister for Foreign Affairs or Minister for National Defence. Importantly, he was a high-profile member of the New Democracy, a liberal-conservative party belonging to the EPP. Therefore, in line with H2, member states with at least one of the governing parties affiliated with the EPP are expected to benefit from sharing political ties with Commissioner Avramopoulos.

The presented case study seems to confirm this expectation, as indicated by the following four observations: First, the Commission’s proposal reflects to a greater extent the preferences of member states with at least one of the governing parties affiliated with the Commissioner’s party family than those of the countries with no such partisan ties. Considering both issues, the average absolute distance from the Commission’s positions is substantively smaller for the former (30 points) than for the latter countries (59.1 points). Second, member states sharing partisan ties with Commissioner Avramopoulos were generally more successful in attaining their preferred outcomes than countries not sharing such ties. On both issues, the average salience-weighted distance from the outcome for the former countries (16.7) was about 16 points lower than that for the latter (33.1), indicating higher bargaining success. The only exception was Slovakia, which attained the lowest bargaining success (100). Third, there is high agreement between decision outcomes and the average position of member states with strong partisan connections to the Commissioner. On the first issue, this position almost perfectly overlapped with the outcome, while on the second issue, it was located only 22.3 policy scale points away from it. Importantly, in both cases, the model based on the average position of countries sharing political ties with the Commissioner produced more accurate forecasts of decision outcomes than the mean position of all member states, which was found to exhibit high predictive accuracy regarding the legislative issues covered in the DEUII dataset (Thomson Citation2011: ch. 7). Fourth, displays that the national Commissioner dividend did not occur in this proposal, as the Commission’s position on the second issue (70) was far away from Greece’s preference (0). Again, this could stem from partisan reasons. During the key negotiations in the years 2018–2019, Greece was ruled by a coalition of Syriza, a radical-leftist-populist party, and ANEL, a radical right-wing populist party. Both parties were not members of the EPP and their ideological profile differed significantly from that of the EPP and the Commissioner’s national party (New Democracy), thus potentially leading to divergent preferences with the Commission.

Conclusion

This study investigated the effect of a Commissioner’s nationality and partisanship on member states’ bargaining success in EU law making. The analysis based on the DEUIII dataset produced the following results. First, member states sharing national ties with the responsible Commissioner were found to be more successful in attaining their preferred outcomes than those without such ties, irrespective of the proposal’s policy area. This finding shows that Commissioners are firmly linked to the countries that appointed them to the Commission and can capitalise on the leeway the EU’s legislative system gives them to pursue their home countries’ interests at the negotiation table.

Second, a Commissioner’s partisanship influences bargaining success. When the responsible Commissioner and one of the parties in the member state’s government come from the same EP party group at the time of decisive negotiations, that member state attains a higher degree of bargaining success than states without such political linkages. However, in contrast to nationality, this relationship is not relevant in all policy areas.

Third, shared national ties between a member state and Commissioners moderate the negative effect of holding conflicting preferences with the Commission on that state’s bargaining success. Hence, while a state holding a preference that diverges from that of the Commission is generally worse positioned to achieve gains close to its ideal point (cf. Arregui Citation2016), it can still be more successful when the responsible Commissioner comes from that state. On the one hand, this finding suggests that Commissioners enjoy great discretion during negotiations. Although the content of a proposal is decided collectively by the College, the responsible Commissioners do not always seem to feel bound to its decision, championing preferences that are inconsistent with those of the entire Commission. On the other hand, this finding implies that Commissioners are very successful in promoting their home countries’ preferences even if they differ substantially from those of the Commission. The study argues that this capability stems from two circumstances: (1) national officials in the Council are attentive to the arguments made by the Commission, and (2) the secluded, restricted, and informal nature of negotiations in the Council and trilogues allows Commissioners and their delegates to deviate from the Commission’s position and exploit their discretion to the advantage of their home countries.

Moreover, the findings hold both theoretical and normative implications. Theoretically, they confirm that principal-agent theory offers a good explanation of the relationship between member states and Commissioners and its consequences for bargaining outcomes. Accordingly, member states are the principals who appoint Commissioners, while Commissioners are the agents pursuing states’ interests in the EU. Through increasing nominations of high-ranking national politicians affiliated with governing parties as Commissioners (see Hartlapp et al. Citation2014), member states boost their loyalty and bind them to behave in a manner consistent with national preferences, thereby exerting more influence on the Commission’s positions and attaining higher bargaining success in areas within their Commissioners’ jurisdictions. This indicates that Commissioners should no longer be conceptualised as technocratic and supranational, but rather as political actors with close national and partisan ties to member states, as suggested by Wonka (Citation2007). In addition, the findings imply that considering the Commission a unitary actor, while being a useful simplifying assumption, is erroneous. As Commissioners are able to act autonomously, future studies should theorise the impact of their personal attributes on the specific phenomena of the EU legislative process, instead of focussing solely on the Commission as a whole.

Normatively, the findings cast doubt on the formal independence of Commissioners. As laid down in Articles 17 TEU and 245 TFEU, the members of the Commission shall be ‘persons whose independence is beyond doubt’ and ‘neither seek nor take instructions from any government or other institution, body, office or entity’, while member states are obliged to ‘respect their independence and not seek to influence them in the performance of their tasks’. This study suggests that these provisions are not respected; not only do Commissioners advance the interests of their home countries, even if they contradict the preferences of the Commission, but also their home countries seem to leverage their activities. Such circumstances produce distributive consequences for policy outcomes and undermine the Commission’s legitimacy, in particular its commitment to promoting the Union’s general interests. They also upset the balance of power, granting member states disproportionate control over the institution that, as a guardian of the treaties, scrutinises the implementation of EU legislation by these countries. If the independent and supranational function of the Commission is to be maintained, future treaty reforms should either change the rules of Commissioners’ appointment or strengthen control over individual Commissioners by, for example, introducing a vote of no confidence against each of them, or giving the Commission’s President greater control over them. In this context, reducing the number of Commissioners to below the number of member states, as foreseen by the Treaties of Nice and Lisbon, could also magnify the importance of national and political ties and thus exacerbate the legitimacy of decision outcomes by further enhancing the advantage of countries with their ‘own’ Commissioners at the expense of those without such posts during a given term of office.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (794 KB)Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the anonymous reviewers and editors for their valuable comments that improved previous versions of the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Adam Kirpsza

Adam Kirpsza is Assistant Professor of Political Science at Jagiellonian University in Krakow, Poland. His research interests include EU institutions, decision making in the EU, and legislative studies. He has published in the Journal of Common Market Studies, Comparative European Politics, and International Political Science Review, amongst others. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 The oath taken by Commissioners after their appointment.

2 More specifically, the final dataset includes proposals submitted in 1996–2000, 2003–2008, and 2012–2018, which were enacted in 1998–2002, 2005–2009, and 2016–2019.

3 Another example is Franz Fischler, Austrian Commissioner for Agriculture, Rural Development, and Fisheries (1995–2004). Swinnen (Citation2008: 145) argues that Fischler sought to reform the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy in line with the ‘Austrian model of agriculture’. It is therefore not surprising that the average salience-weighted bargaining success of Austria attained on proposals and issues led by Fischler was the highest among all member states (16.35).

References

- Arregui, Javier (2016). ‘Determinants of Bargaining Satisfaction across Policy Domains in the European Union Council of Ministers’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 54:5, 1105–22.

- Arregui, Javier, and Clément Perarnaud (2022). ‘A New Dataset on Legislative Decision-Making in the European Union: The DEU III Dataset’, Journal of European Public Policy, 29:1, 12–22.

- Arregui, Javier, and Robert Thomson (2009). ‘States’ Bargaining Success in the European Union’, Journal of European Public Policy, 16:5, 655–76.

- Bailer, Stefanie (2004). ‘Bargaining Success in the European Union: The Impact of Exogenous and Endogenous Power Resources’, European Union Politics, 5:1, 99–123.

- Bailer, Stefanie (2014). ‘An Agent Dependent on the EU Member States? The Determinants of the European Commission’s Legislative Success in the European Union’, Journal of European Integration, 36:1, 37–53.

- Bailer, Stefanie, Mikko Mattila, and Gerald Schneider (2015). ‘Money Makes the EU Go Round: The Objective Foundations of Conflict in the Council of Ministers’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 53:3, 437–56.

- Brandsma, Gijs J. (2019). ‘Transparency of EU Informal Trilogues through Public Feedback in the European Parliament’, Journal of European Public Policy, 26:10, 1464–83.

- Bürgin, Alexander (2017). ‘Internal Coordination and Legitimation Strategies: Assessing the Influence of Individual Commissioners in the Policy Formulation Process’, Journal of European Integration, 39:1, 1–15.

- Costello, Rory, and Robert Thomson (2013). ‘The Distribution of Power among EU Institutions: Who Wins under Codecision and Why?’, Journal of European Public Policy, 20:7, 1025–39.

- Cross, James (2013). ‘Everyone’s a Winner (Almost): Bargaining Success in the Council of Ministers of the European Union’, European Union Politics, 14:1, 70–94.

- Cross, James, and Austė Vaznonytė (2020). ‘Can We Do What We Say We Will Do? Issue Salience, Government Effectiveness, and the Legislative Efficiency of Council Presidencies’, European Union Politics, 21:4, 657–79.

- Döring, Holger (2007). ‘The Composition of the College of Commissioners’, European Union Politics, 8:2, 207–28.

- Döring, Holger, and Philip Manow (2022). ‘Parliaments and Governments Database’. ParlGov. Retrieved from https://www.parlgov.org/.

- Egeberg, Morten (1999). ‘Transcending Intergovernmentalism? Identity and Role Perceptions of National Officials in EU Decision-Making’, Journal of European Public Policy, 6:3, 456–74.

- Ershova, Anastasia (2019). ‘The Watchdog or the Mandarin? Assessing the Impact of the Directorates General on the EU Legislative Process’, Journal of European Public Policy, 26:3, 407–27.

- Gehring, Kai, and Stephan A. Schneider (2018). ‘Towards the Greater Good? EU Commissioners’ Nationality and Budget Allocation in the European Union’, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 10:1, 214–39.

- Golub, Jonathan (2012). ‘How the European Union Does Not Work: National Bargaining Success in the Council of Ministers’, Journal of European Public Policy, 19:9, 1294–315.

- Häge, Frank (2017). ‘The Scheduling Power of the EU Council Presidency’, Journal of European Public Policy, 24:5, 695–713.

- Hagemann, Sara, and Bjorn Høyland (2008). ‘Parties in the Council?’, Journal of European Public Policy, 15:8, 1205–21.

- Hagemann, Sara, and Bjorn Høyland (2010). ‘Bicameral Politics in the European Union’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 48:4, 811–33.

- Hagemann, Sara, Sara B. Hobolt, and Christopher Wratil (2017). ‘Government Responsiveness in the European Union: Evidence from Council Voting’, Comparative Political Studies, 50:6, 850–76.

- Hartlapp, Miriam, Julia Metz, and Christian Rauh (2014). Which Policy for Europe? Power and Conflict inside the European Commission. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hix, Simon, Abdul Noury, and Gerard Roland (2007). Democratic Politics in the European Parliament. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hosli, Madeleine O. (2000). ‘The Creation of the European Economic and Monetary Union (EMU): Intergovernmental Negotiations and Two-Level Games’, Journal of European Public Policy, 7:5, 744–66.

- Hosli, Madeleine O., Mikko Mattila, and Marc Uriot (2011). ‘Voting in the Council of the European Union after the 2004 Enlargement: A Comparison of Old and New Member States’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 49:6, 1249–70.

- Hug, Simon (2003). ‘Endogenous Preferences and Delegation in the European Union’, Comparative Political Studies, 36:1–2, 41–74.

- Killermann, Kira (2016). ‘Loose Ties or Strong Bonds? The Effect of a Commissioner’s Nationality and Partisanship on Voting in the Council’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 54:6, 1367–83.

- Kirpsza, Adam (2023). ‘Quid Pro Quo: The Effect of Issue Linkage on Member States’ Bargaining Success in European Union Lawmaking’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 61:2, 323–43.

- Kreppel, Amie (2013). ‘Legislative Implications of the Lisbon Treaty: The (Potential) Role of Ideology’, West European Politics, 36:6, 1178–98.

- Kreppel, Amie, and Buket Oztas (2017). ‘Leading the Band or Just Playing the Tune? Reassessing the Agenda-Setting Powers of the European Commission’, Comparative Political Studies, 50:8, 1118–50.

- Kubosova, Lucia (2007). ‘Kovacs: EU Commissioners Should Not Act as National Ministers’. EUobserver. Retrieved from https://euobserver.com/eu-political/24211.

- Kudrna, Zdenek, and Fabio Wasserfallen (2021). ‘Conflict among Member States and the Influence of the Commission in EMU Politics’, Journal of European Public Policy, 28:6, 902–13.

- Laloux, Thomas (2020). ‘Informal Negotiations in EU Legislative Decision-Making: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda’, European Political Science, 19:3, 443–60.

- Laloux, Thomas, and Tom Delreux (2018). ‘How Much Do Agents in Trilogues Deviate from Their Principals’ Instructions? Introducing a Deviation Index’, Journal of European Public Policy, 25:7, 1049–67.

- Laloux, Thomas, and Lara Panning (2021). ‘Why Defend Something I Don’t Agree with? Conflicts within the Commission and Legislative Amendments in Trilogues’, Politics and Governance, 9:3, 40–51.

- Lundgren, Magnus, Stefanie Bailer, Lisa M. Dellmuth, Jonas Tallberg, and Silvana Târlea (2019). ‘Bargaining Success in the Reform of the Eurozone’, European Union Politics, 20:1, 65–88.

- Mariano, Nathan, and Christina Schneider (2022). ‘Euroscepticism and Bargaining Success in the European Union’, Journal of European Public Policy, 29:1, 61–77.

- Mazei, Jens, Joachim Hüffmeier, Philipp Alexander Freund, Alice F. Stuhlmacher, Lena Bilke, and Guido Hertel (2015). ‘A Meta-Analysis on Gender Differences in Negotiation Outcomes and Their Moderators’, Psychological Bulletin, 141:1, 85–104.

- McElroy, Gail, and Kenneth Benoit (2012). ‘Policy Positioning in the European Parliament’, European Union Politics, 13:1, 150–67.

- Panning, Lara (2021). ‘Building and Managing the European Commission’s Position for Trilogue Negotiations’, Journal of European Public Policy, 28:1, 32–52.

- Pollack, Mark A. (2003). The Engines of Integration: Delegation, Agency and Agenda Setting in the EU. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rasmussen, Anne (2003). ‘The Role of the European Commission in Co-Decision: A Strategic Facilitator Operating in a Situation of Structural Disadvantage’, European Integration Online Papers, 7, 10.

- Rasmussen, Anne, and Christine Reh (2013). ‘The Consequences of Concluding Codecision Early: Trilogues and Intra-Institutional Bargaining Success’, Journal of European Public Policy, 20:7, 1006–24.

- Rauh, Christian (2019). ‘EU Politicization and Policy Initiatives of the European Commission: The Case of Consumer Policy’, Journal of European Public Policy, 26:3, 344–65.

- Rauh, Christian (2021). ‘One Agenda-Setter or Many? The Varying Success of Policy Initiatives by Individual Directorates-General of the European Commission 1994–2016’, European Union Politics, 22:1, 3–24.

- Roederer-Rynning, Christilla, and Justin Greenwood (2015). ‘The Culture of Trilogues’, Journal of European Public Policy, 22:8, 1148–65.

- Roederer-Rynning, Christilla, and Justin Greenwood (2021). ‘Black Boxes and Open Secrets: Trilogues as ‘Politicised Diplomacy’, West European Politics, 44:3, 485–509.

- Spence, David (2006). ‘The President, the College and the Cabinets’, in David Spence and Geoffrey Edwards (eds.), The European Commission. London: John Harper Publishing.

- Swinnen, Johan (2008). The Perfect Storm: The Political Economy of the Fischler Reforms of the Common Agricultural Policy. Brussels: CEPS Paperbacks.

- Thomson, Robert (2008a). ‘National Actors in International Organizations: The Case of the European Commission’, Comparative Political Studies, 41:2, 169–92.

- Thomson, Robert (2008b). ‘The Council Presidency in the European Union: Responsibility with Power’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 46:3, 593–617.

- Thomson, Robert (2011). Resolving Controversy in the European Union. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Thomson, Robert, and Partick Dumont (2022). ‘A Comparison of Two Views on the European Commission: Engine of Integration and Conduit of National Interests’, Journal of European Public Policy, 29:1, 136–54.

- Vaubel, Roland, Bernhard Klingen, and David Müller (2012). ‘There is Life after the Commission: An Empirical Analysis of Private Interest Representation by Former EU-Commissioners, 1981–2009’, The Review of International Organizations, 7:1, 59–80.

- Vaznonytė, Austė (2020). ‘The Rotating Presidency of the Council of the EU-Still an Agenda-Setter?’, European Union Politics, 21:3, 497–518.

- Wonka, Arndt (2007). ‘Technocratic and Independent? The Appointment of European Commissioners and Its Policy Implications’, Journal of European Public Policy, 14:2, 169–89.

- Wonka, Arndt (2008). ‘Decision-Making Dynamics in the European Commission: Partisan, National or Sectoral?’, Journal of European Public Policy, 15:8, 1145–63.