Abstract

In parliamentary democracies, elections distribute the seats in parliament, but who gets into government and determines the policy agenda over the course of the legislative term is decided upon after the elections, in negotiations between the political parties. This introduction to the special issue discusses research concerning dynamic approaches to coalition governments. A dynamic approach implies that what happens at the electoral stage influences the government formation stage, which in turn shapes what happens during the government’s tenure, which may influence the cabinet’s durability. Hence, this type of research tries to analyse various stages of a government’s ‘life cycle’ from its ‘birth’ to its ‘death’ as interdependent processes, rather than examining them in mutual isolation. These processes may be restricted to the confines of a self-contained universe of politicians and political parties, or they may involve ‘external’ events, such as, for example, elections, or the state of the economy. In addition to having a dynamic approach to analysing coalitions, the contributions in the special issue use brand-new comparative data from several independent research projects investigating various aspects of coalition politics.

In parliamentary democracies, elections distribute the parliamentary seats, but what is decided upon after the elections and in negotiations between the political parties is clearly of central importance to our understanding of such political systems. The focus of coalition studies has mainly been what happens after and between elections, and for about seven decades scholars have researched why some coalition governments form while others do not, how they distribute office and policy payoffs to coalition partners, how they plan to guarantee a certain level of stability, how they eventually collapse, and the electoral consequences of their downfall.

However, coalition studies have been criticised for their static nature, as much theoretical and empirical work has focused on isolated episodes of complex political processes, such as the formation of government coalitions, without considering what happens at other stages of the coalition ‘life cycle’. For instance, in empirical studies, scholars have employed as their explanatory variables mostly the parties’ initial ‘endowments’, such as legislative seat shares or policy preferences – attributes which typically remain unchanged during the life of a coalition (e.g. Druckman Citation2008; Laver Citation1974, Citation1986, Citation2008). This classic critique of the state of the art has not remained unchallenged (see e.g. Strøm Citation2008). In particular, the study of isolated episodes has given way to a more dynamic approach incorporating how coalition actors’ experiences at one stage of a coalition’s life cycle influence their behaviour in episodes that follow and how anticipation of challenges during the coalition life cycle governs their behaviour earlier on. Thus, the idea that what happens at the government formation stage shapes what happens during the government’s tenure, which in turn influences its durability.

In this special issue, we aim to contribute further towards a more dynamic approach to coalition research. In the remainder of this introduction to the special issue, we first summarise the critical discussion regarding the static nature of coalition research. We then elaborate on different ways in which political science research can account for the dynamic nature of government coalitions and coalition politics. Specifically, we refer to three types of dynamics: interactions between coalition actors within each stage of the coalition cycle; influence from actual events at one stage of the coalition cycle to another, and from the anticipation of such events in a later stage of the coalition cycle; dynamics within the coalition resulting from changes in the world outside coalition politics. Next, we review the literature showing where we stand regarding making coalition research dynamic. In so doing, we particularly focus on studies providing a comparative perspective. Some of the gaps identified in our review are addressed in the special issue articles. But rather than providing a separate section with a preview of the contributions to this special issue, we place them in the literature discussion, showing how they contribute to the research agenda.

A ‘dynamic turn’ in coalition research

Missing dynamics in coalition research

From its inception in the 1950s, coalition research has tried to explain which governments form (Axelrod Citation1970; De Swaan Citation1973; Dodd Citation1976; Gamson Citation1961; Riker Citation1962; von Neumann and Morgenstern Citation1953; for reviews see Laver Citation1998; Laver and Schofield Citation1990; Müller Citation2009; Strøm and Nyblade Citation2007). Later, the scholarly interest also shifted to government duration (Dodd Citation1976; Warwick Citation1994; for reviews see e.g. Grofman and van Roozendaal Citation1997; Laver Citation2003) and portfolio allocation (Browne and Franklin Citation1973; Gamson Citation1961; for a review Warwick and Druckman Citation2001). For a long time, research on these topics treated each topic as isolated episodes in the life of coalitions. Such research hence took a static perspective on coalition politics. While coalition research has made considerable progress in many respects, its static perspective has been seen as an inherent weakness (e.g. Druckman Citation2008; Laver Citation1974, Citation1986).

Already in 1974, Laver criticised the bulk of studies concerned with government formation and based on formal coalition theories as ahistorical, not considering the national history of coalitions: ‘It is not true … that the slate is wiped clean after every election, with parties searching for coalition partners as if the political world had just been created’ (1974: 259). Thus, a more realistic perspective would try to understand coalition formation – or, indeed, any aspect of coalition politics – before the background of the experiences the parties made with each other in earlier situations.

About a decade later, Laver (Citation1986: 33) again criticised that ‘most formal theories of coalition formation are essentially static’, aiming at explaining static aspects of coalition politics, such as the party composition of coalitions or portfolio distribution among government parties. This was considered a major limitation, as ‘[m]any of the more interesting aspects of coalition politics tend, of course, to be concerned with dynamic aspects of the situation’. What is more, the explanations suggested by formal coalition theories rest on a set of variables that are also static in nature, such as parties’ parliamentary seat shares or their policy positions as indicated by their electoral manifestos. Because of this confinement of coalition research, most of the predictions from static coalition theories ‘cannot change until a new election produces a new set of parameters’ (Laver Citation1986: 34).

Arguing for a dynamic perspective in coalition research

In 2008, Political Research Quarterly published a symposium on ‘Dynamic Theories of Coalition Politics’ edited by James N. Druckman. The symposium contained some new work exemplifying dynamic analysis but also a few pieces commenting on the state of the art. In one of the latter, Laver (Citation2008) restated and elaborated his criticisms as cited above. In another, Druckman (Citation2008: 479–80) argued that ‘for an approach to be genuinely dynamic, there must be some incorporation of the past and/or the future’. While underlining the claims made by Laver, Druckman added a new twist by referring to the missing link with the dynamic world outside coalitions, suggesting that the ‘typical research study explores a single coalition process at one point in time, with limited attention to dynamics external to coalition politics’.

In the same symposium, Kaare Strøm, another leading coalition researcher, arrived at a conclusion that seems at odds with the above-mentioned criticisms. Accordingly, the ‘study of coalition politics has come a long way from its one-time conception of coalition bargaining as episodic and mutually isolated events, brought about spontaneously and exogenously by a general election or the sudden fall of an incumbent government’ (2008: 537). And even Druckman (Citation2008: 480) referred to ‘notable examples of dynamic research’.

However, it is not possible, neither in terms of formal theory nor in terms of empirical modelling, to capture the full complexity of real-world coalition dynamics. As Laver (Citation2008) argues, a full model of coalition politics would need to include all the stages through which coalitions go, take into consideration the political institutions which structure the interactions of coalition actors, as well as theorise how elections impact the whole process. If one adds the requirement that such a model should also be reasonably realistic in its assumptions, it becomes ‘formally intractable’ by conventional methods (see also de Marchi and Laver Citation2023).

Nonetheless, as Strøm and Druckman argue, one may consider empirical work that poses relationships between individual variables in a less strict theoretical framework. Thus, in terms of theory, such studies might be best understood as building blocks for empirical mid-range theories (Merton Citation1968). One of the developments behind the more positively tuned judgments of Druckman and, in particular, Strøm, relates to one of the most profound changes in the agenda of coalition research – the relatively recent focus on coalition governance. The classical studies of coalition research largely neglected what occurs between government formation and termination. As argued by Laver and Shepsle (Citation1990a, Citation1996), coalition research had, at that point, ignored the fact that coalitions ‘are also governments’ and that governments are the main drivers of public policy. Political parties thus strive for government office to determine public policy. They do so either because politicians have genuine policy desires themselves or because they need to please their voters who certainly do have policy demands. Given the centrality of government policy, the parties’ rational expectations about what will happen after government formation influences the formation process itself.

In addition, Laver and Shepsle (Citation1996) argued that the organisation of government in monocratic ministries, large ministerial discretion in making final policy decisions, and the ministers’ key role in shaping collective cabinet decisions in their domain must lead to a specific governance structure: ‘ministerial government’. Accordingly, dividing the portfolios among the coalition parties and granting each minister (close to) dictatorial power over policy making in the ministry’s domain provides a credible mechanism to determine government policy. Thus, according to Laver and Shepsle, the presence of this mechanism allows political parties to foresee the policy output of alternative governments and commit to specific coalitions. In that sense, their theory of ministerial governance dynamised coalition research in shifting attention to the process of producing policy output. Thereby they provide a strong theoretical link between the two separate stages in the life of coalitions that had captured the most attention of coalition researchers – government formation and government termination. In the governance-centred perspective, the crucial challenge of coalition politics is thus to build a governance mechanism that credibly will produce the intended policies.

Once Laver and Shepsle had brought governance to the centre stage of coalition research, alternative approaches to coalition decision making emerged. On the one hand, some of the assumptions behind the theory of ministerial government were challenged (Dunleavy and Bastow Citation2001; Müller and Strøm Citation2008). On the other hand, attention was drawn to the different kinds of governance mechanisms in Western European coalitions (Müller and Strøm Citation2000), that is, mechanisms by which coalitions, consisting of more or less compatible parties, are able to coordinate and bargain over government policy. Such mechanisms can either be created as part of the coalition deal when parties form a government, by coalition agreements, or policy monitoring arrangements (e.g. via junior ministers or shadowing by other ministers). Alternatively, coalition governance can rest in existing institutions – such as mechanisms of parliamentary scrutiny – remodelled to support the coalition deal. Notwithstanding the differences between these approaches, they have in common that their focus is on the interaction of the coalition actors over time. A focus on coalition governance hence introduces a dynamic perspective to the study of coalition politics.

Introducing the coalition ‘life cycle’

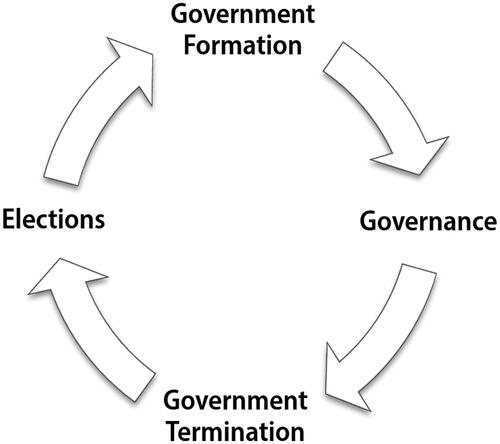

As part of the agenda of taking a dynamic perspective in coalition research, Müller et al. (Citation2008) introduce the concept of the ‘coalition life cycle’. Put briefly, as illustrated in , they argue that what happens in one stage of the coalition life cycle influences what happens in other stages. That is, the idea that bargaining during the government formation stage shapes what happens during the government’s tenure and how parties work together in government, which in turn influences government durability and election outcomes. At the same time, the lessons political actors learn in one particular life cycle influence their behaviour in the cycles to come. Yet when making their moves, political actors also try to anticipate the consequences that decisions and occurrences in one stage of the cycle will have for what happens in later stages and adapt their strategies accordingly.

Figure 1. The coalition life cycle.

Source: Müller et al. (Citation2008).

Thus, the coalition life cycle is a simple heuristic framework that provides a broad-brush picture of coalition politics, directing attention to the dynamics that result from the sequence of distinct stages. Accordingly, elections are followed by the stages of government formation, governing (‘coalition governance’), termination, and another election. This last stage, of course, assumes that government termination occurs at the end of the constitutional inter-election period or that political actors engineer early elections when the cabinet terminates. Yet both options may fail to be realised. Then, rather than with an election, a new life cycle begins with the formation of a new government – be it another coalition, a single-party minority cabinet, or a technocratic government – in the sitting parliament.

Other authors have offered up different versions of (parts of) the coalition life cycle, adapted to their analytical focus. For example, Fortunato (Citation2021: 5), who studies the interplay between the electorate and coalition politics, defines the ‘cycle of coalitions’ as ‘how voters perceive the process of multiparty policy making, how these perceptions influence their voting behaviour, and how the behaviour, in turn, informs the choices that parties make in the legislature’. De Marchi and Laver (Citation2023: 11) conceptualise the ‘governance cycle’ as election – government formation – government survival – election. In his review of the state of the art of formal coalition theory, Laver (Citation2008) employs a more complex heuristic model – including political institutions and events – to highlight deficits of extant theories.

Capturing dynamics in coalition politics

The collected criticism of the static nature of the study of coalition politics suggests that a dynamic analysis would incorporate the time dimension of coalition politics. Dynamics can relate to processes within one stage of the coalition cycle, to the interplay between different stages of the same coalition cycle, or to dynamics from one cycle to the next. Major ruptures in politics – often dramatic events – may fall into one of the three categories but have a lasting impact on coalition politics way beyond the next coalition cycle, leading to the freezing of certain patterns of coalition politics. A full picture of dynamics in coalition politics would thus register short-term changes in the categories given above but also consider the long cycles and the direction-setting dynamics at historical junctures.

Another takeaway from the critique of coalition research is that analyses should not be confined to making inferences from the initial endowments of coalition actors and other factors that typically remain frozen for the lifetime of a coalition. While important, initial endowments do not enforce a particular strategy on coalition actors. There is room for agency. Accordingly, a dynamic analysis builds on observing the interactions of coalition actors. Research can capture such dynamics at quite different levels of granularity. Studies of individual episodes of coalition politics often focus on the sequence and contents of moves by the coalition actors to explain the outcome (Andeweg et al. Citation2011; Müller and Strøm Citation1999; Strøm Citation1994). However, reconstructing the strategic interactions that drive coalition politics (Lupia and Strøm Citation1995) ‘requires a much more detailed knowledge of intra- and inter-party affairs than is usually found among scholars doing large-scale comparative research’ (Damgaard Citation2008: 302). Such studies therefore often summarise complex processes in a single or a few variables. But we may consider such analyses dynamic if they employ variables resulting from the interactions between coalition actors rather than from their initial endowments.

Another way the analysis of coalition politics can turn dynamic is by incorporating changes in the ‘outside world’ surrounding it (Druckman Citation2008). Probably the part of the outside world that is most persistently present in the minds of coalition actors is the electorate. While voters periodically matter for coalition politics by assigning coalition actors their weights in terms of parliamentary seats, the electoral connection is always present with the actors trying to anticipate how their moves will resonate with the final arbiters in the political game. Thus, various conceptions of a cycle in coalition politics have explicitly incorporated elections as a stage of coalition politics. Important issues and hence research questions relating to this stage include the timing of elections, the parties’ coalition signals in the electoral campaign, and how political accountability plays out in different coalition settings. Other parts of the outside world of more immediate relevance to coalition politics may include institutional actors, the business community, foreign powers, and international organisations.

Admittedly, the organisation of our literature survey leaves no natural place for discussing another source of dynamics in coalition politics: in-between elections changes of political actors. Giving up the assumption that parties are ‘unitary actors’ which underlies traditional coalition studies (Laver and Schofield Citation1990), researchers have either built their theories on individual MPs who continuously evaluate whether to stay with their party or to split and join another party – ‘party system evolution’ (Laver Citation1989; Laver and Benoit Citation2003) – or on party factions commanding the loyalty of sections of the party (Gianetti and Benoit Citation2009; Laver and Shepsle Citation1990b). Changes in the party membership of MPs or faction strength or alliance can occur at any time between elections, and they can have important consequences for coalition politics. Empirical research on party system evolution so far has confined itself largely to the most likely cases, such as Japan or Italy (see Giannetti and Laver Citation2001; Laver and Kato Citation2001) and work on intra-party factional dynamics has not yet given much attention to how these affect coalition politics (Bäck Citation2008; Ceron Citation2019; Greene and Haber Citation2016). Notwithstanding these limitations, both perspectives are promising avenues for future work on coalition dynamics.

Real-world developments and new data

Two developments make this special issue with its focus on empirical coalition dynamics a timely endeavour. One is the recent changes in the real world of coalition politics which suggest that it might be questionable whether the empirical findings from the first few post-war decades are still valid generalisations. The other is that the special issue can draw on brand-new data from several independent research projects investigating various aspects of coalition politics.

The real world of party politics has seen important changes in the last two decades which may potentially challenge established wisdom regarding the working of coalition politics. For one thing, coalition governments have become the even more dominant form of government in parliamentary systems. Not only have single-party majority governments become a dying species (Mair Citation1997) with even the UK going through an episode of coalition government recently (Barlow and Bale Citation2021), but in addition, countries that traditionally were going back and forth between single-party (minority) governments and coalition governments now seem to be confined to coalition governments. Accordingly, parties once committed to a ‘no coalition’ strategy, such as the Irish Fianna Fáil, the Labour parties in Norway and Sweden, and the Socialists in Spain have become ‘coalitional’. In some cases, formal support arrangements between minority cabinets and non-cabinet parties have functioned as a prelude to coalition governments. In any case, such substitutes to formal coalition government also have become more frequent in recent decades (see Thürk and Krauss Citation2023).

The most noticeable changes in the party systems during the past few decades have been the loss of electoral support for previously strong centrist parties and the formation and rise of new anti-establishment parties and populist parties of the extreme left or extreme right. These parties, the weakening of the dominant left–right dimension of conflict, and the increased salience of new policy dimensions have led to greater uncertainty and complexity in bargaining over government and policy. Thus, much of the recent debate about the changing party systems has been about the rise of populist parties, which are now a regular fixture in most Western European parliaments and have served both as support parties to government and held cabinet positions in some countries (Bergman et al. Citation2021a). Also, when populist parties do not enter government, they can have a noticeable impact on the party system and the political agenda. Most countries in Western Europe have seen an increasing fragmentation of their party systems over time – often because of the electoral success of anti-establishment parties and populist parties of the extreme left and/or right. And in many countries, having a large populist party influences the coalition building among the mainstream parties, effectively making it more difficult to form majorities (Bergman et al. Citation2021a).

This special issue takes advantage of recent data collection efforts in several research projects. Central to our concern is a project bringing data collection on coalition politics in Western European up to date, which allows us to cover the impact on coalition politics of the party system changes described above. Specifically, building and expanding on Müller and Strøm (Citation2000), an extension of the project (Bergman et al. Citation2021b, Hellström et al. Citation2021) provides data on government formation, coalition governance institutions, and coalition termination in 17 Western European countries from the 1990s to the present. Most authors in the special issue have been involved in that project as experts in their respective countries using standardised coding instructions and interview guidelines. Specifically, the data were gathered from official documents (government, administration, and parliament) and party documents (election manifestos, coalition agreements), by conducting semi-structured interviews with (former) staff and cabinet members, as well as a systematic analysis of media reports.

Those authors not directly involved in the project have had access to the project data to enable them to combine it with their own data and write articles for the special issue. The authors of individual articles also use novel comparative data from their own projects on parliamentary dissolution powers (Schleiter and Bucur Citation2023), political parties’ issue emphasis in election campaigns (Däubler et al. Citation2022), minority government support arrangements (Thürk and Krauss Citation2023), portfolio design (Meyer et al. Citation2023), and government policy outputs (Bergman et al. Citation2023). Below we describe the articles in the special issue in more depth, discussing how they contribute to our understanding of the four stages of the coalition life cycle, and how they contribute to a dynamic approach to coalition research.

Coalition dynamics at different life cycle stages

Dynamics at the electoral stage

The electoral stage in the coalition life cycle is not confined to the election itself but also includes the run-up to it. Elections determine the numerical strength of parties – one of the main variables theorised to understand which governments form. Yet electoral campaigns are political processes that can influence coalition formation way beyond assigning parliamentary voting weights to political parties. Parties may use campaigns to make ‘hard’ pledges – policy commitments deemed as ‘not negotiable’ conditions for government participation. Party leaders, who ‘tie themselves to the mast’ in that manner, try to reassure voters and activists that the rank-and-file concerns will not be sacrificed for the gains of a few party leaders in coalition negotiations. While such moves may help parties to maintain or win electoral support, they also make the tasks of coalition negotiators more complex, which may prolong the time required for bargaining or even prevent the striking of a coalition deal.

While policy pledges still leave coalition negotiators some room for interpretation and hence manoeuvre, commitments concerning membership in future government coalitions are unambiguous. Accordingly, parties may commit to specific pre-electoral coalitions or reject serving in coalitions that include some other party or parties. Parties make such commitments in electoral campaigns to mobilise voters who have positive or negative attitudes concerning some parties or types of government. Party commitments to cooperate with one or more other parties, to explicitly exclude specific parties as coalition partners, or to stay out of government under certain stated conditions hence constrain party leaders in the government formation arena.

Several scholars have focused on the impact of pre-electoral commitments on government formation, connecting the electoral stage to the government formation stage (e.g. Debus Citation2009; Golder Citation2006; Ibenskas Citation2016). It has been shown that the probability of parties forming a government together after an election increases if these parties entered into a pre-electoral coalition beforehand (Debus Citation2009; Martin and Stevenson Citation2001). Debus (Citation2009) argues that we should analyse the impact of both ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ pre-electoral commitments when connecting the electoral stage to the formation stage. Positive pre-electoral commitments include statements or joint policy programmes where some parties present a promise to the voters that they will collaborate after the election. Negative pre-electoral commitments instead entail election promises where some parties are characterised as ‘uncoalitionable’.

Drawing on such work and focusing on the role of pre-electoral alliances, Bäck et al. (Citation2023) argue that there are several ways in which such alliances could influence bargaining duration, either speeding up the formation process or in some cases, pro-longing the process. For example, if parties spend a lot of time before the election bargaining over policy issues, this should reduce uncertainty about potential coalition partners’ policy preferences. The authors also argue that government formation processes may be swiftly concluded since pre-electoral alliances tie ‘the hands of the included parties, as breaking electoral promises can come with significant costs in future elections’, which means that parties are less likely to negotiate with other potential partners (see also Bäck et al. Citation2022a).

Focusing on more subtle signalling to voters and potential coalition partners during the election campaign, Däubler et al. (Citation2022), argue that policy emphasis in the last few weeks before the election matters for portfolio allocation, because parties can focus their message, react to exogenous events, and use campaign communication as a commitment device. Evaluating this argument by making use of a novel dataset on party representatives’ campaign statements in seven European countries, the authors show that the policy focus of campaign statements, especially those stating positions rather than referring to valence, predicts who will control a ministerial portfolio associated with the respective policy domain.

So far, we have been looking forward, from elections to subsequent stages of the coalition life cycle. Yet elections are a mechanism of both delegation and accountability. They also come after a period of government and hence allow voters to reward or punish parties for their deeds and omissions during government office. Several observational studies have investigated the electoral consequences coalition membership or the occupying of particular portfolios or their role as junior or senior partners have for political parties, finding much more punishment than reward (Greene et al. Citation2021; Hjermitslev Citation2020; Klüver and Spoon Citation2020; Narud and Valen Citation2008) and loss of party ideological profile (Fortunato Citation2019a; Fortunato and Stevenson Citation2013).

Other observational studies have related the parties’ electoral performance to specific acts of behaviour by parties while in office in a government coalition, such as conflict with the coalition partners (Plescia and Kritzinger Citation2022), breaking out of the coalition (Mershon Citation2002; So Citationforthcoming; Tavits Citation2008) and opportunistic election timing (Beckman and Schleiter Citation2020). Generally, these studies suggest that governing in coalitions is an electorally risky undertaking for political parties, yet it depends on the specific conditions. For instance, So (Citationforthcoming) analyses what happens after termination, connecting the termination stage to the electoral stage. She argues that the electoral impact of conflictual cabinet terminations depends on voters’ perceptions of them. Terminations following non-policy conflicts should be electorally costly since they signal parties’ deteriorating governing competence. In contrast, So (Citationforthcoming) argues that terminations following policy conflicts signal parties’ unwillingness to compromise their policy positions and clarify parties’ policy profiles, thus allowing them to evade voter punishment. Experimental studies asking hypothetical questions about parties’ compromising behaviour in coalitions to samples of voters have further delved into the mechanisms behind the observed patterns (e.g. Plescia et al. Citation2022).

Dynamics at the formation stage

The formation process and the party composition of government

The classical coalition studies focused on explaining the type of government and party membership in government with the help of the parties’ endowments with seat-shares and their ideological positions (Axelrod Citation1970; De Swaan Citation1973; Gamson Citation1961; Riker Citation1962). Thus, the connection between election outcomes and coalition bargaining outcomes are clear, but as previously mentioned, scholars have often treated the parties’ initial endowments, such as their policy preferences, as unchanged during the life of a coalition. Nonetheless, for the formation stage, it is undoubtably an important aspect. However, as mentioned above, elections may include campaign behaviour and explicit statements about commitment to certain types of government, preferred coalition partners or parties explicitly unpreferred as future partners.

Coalition formation is not a process that quasi-automatically unfolds from the presence of certain objective conditions, such as the parties’ seat shares or ideological distances. Rather, it requires repeated interactions between party leaders over a period of time. This process for a long time has figured in quantitative coalition research with a single indicator, its total duration (De Winter and Dumont Citation2008; Diermeier and van Roozendaal Citation1998; Golder Citation2010; Martin and Vanberg Citation2003). This indicator obscures important aspects of the actual dynamics of that process, in particular, whether it covers one or several formation attempts. Recently Ecker and Meyer (Citation2020) have captured more of the dynamics of the government formation process by breaking it down into its individual episodes (i.e. formation attempts). This allows them to shift the focus from a systemic to an actor-centred approach and to capture post-electoral intra-party dynamics. Indeed, they show that post-electoral replacement of the party leader reduces the relevant party’s chance of inclusion in the government.

Focusing on making the study of the government formation process more dynamic, Bäck et al. (Citation2023) stress the importance of ‘familiarity’ between political parties for government formation, meaning that political parties that have experience ‘of working together in government’ could be at an advantage when forming governments (Franklin and Mackie Citation1983: 276). Bäck and Dumont (Citation2007) make a similar argument on how incumbency influences future coalition formations in that ‘government formation is not considered as a one-shot game by political parties: they evaluate available alternatives according to their experience in and out of government (to re-form the same coalition or to exclude a long-standing governmental party), and they anticipate future formation opportunities (by including an unnecessary partner)’ (Bäck and Dumont Citation2007: 495). Past experiences of governance are often argued to have an effect on bargaining outcomes. For example, Tavits (Citation2008) argues that parties are likely to exclude a defector party, that is, a party that withdrew from their previous coalition, from future cooperation (also see Warwick Citation2012). Also, as Laver (Citation1974: 261–3) argues, if the previous cooperation has been successful, and their members are satisfied with the cooperation, parties will be more favourable to forming the same government once more.

Focusing specifically on the role of incumbents and their formal institutional powers, Schleiter and Bucur (Citation2023) develop a theory of coalition formation in the shadow of parliamentary dissolution. The authors argue that incumbents who can dissolve the assembly are more likely to return to government than incumbents who lack this power because they enjoy greater bargaining leverage and reputational advantages in coalition formation. Schleiter and Bucur test this expectation, analysing governments during the post-war period in Western and Eastern Europe and find that coalition leaders with the discretion to dissolve parliament secure significant advantages in negotiating their return to power.

Also analysing government formation, Dumont et al. (Citation2023) focus specifically on the role of preference tangentiality in coalition formation. Drawing on Luebbert (Citation1986), they argue that parties that care about different issues are the most compatible partners, as their tangential preferences allow them to engage in policy logrolling and enable them to preserve their distinctiveness in the eyes of voters. As a result, such parties are more likely to form coalitions than parties that are ideologically close. The authors evaluate this hypothesis analysing governments formed in Western Europe during the post-war period. Contrary to Luebbert’s expectations, they find that parties that emphasise the same issues are more natural coalition partners when their ideological positions are not too dissimilar.

Thürk and Krauss (Citation2023) investigate the formation of those minority governments that are based on an institutionalised long-term support partnership with parties staying outside the cabinet. Analysing data from 27 Eastern and Western European countries they find that the size of the largest party and the party type of the support party are important explanatory factors. Anticipation of how the external support arrangement will impact the process of governing is a strong influence on the willingness of government parties to enter such deals. Specifically, a commitment by support parties to sectoral interests seems important as such commitments lead to logrolling over different policies rather than the negotiating of substantive compromises which are more painful to the government parties.

The allocation and design of ministerial portfolios

We can also observe dynamic processes, such as when it comes to portfolio allocation, a part of the formation stage. Similarly to party composition of coalitions, election outcomes matter here. Famously, the portfolio shares coalition parties receive have been captured in ‘Gamson’s law’, predicting that cabinet seats will be allocated among the coalition parties in proportion to the parliamentary support these parties provide for the government, and that has been found to be ‘one of the strongest empirical relationships documented in the social sciences’ (Gamson Citation1961; Warwick and Druckman Citation2006: 636). In addition, several studies have tried to understand the quality of portfolio allocation, focusing on which departments go to which parties (Bäck et al. Citation2011; Browne and Feste Citation1975; Budge and Keman Citation1990; Druckman and Warwick Citation2005).

These classical studies in portfolio allocation are static in several ways. Firstly, they consider the portfolio allocation at the beginning of a cabinet but disregard changes later on during the lifetime of a government. Secondly, they take the portfolios which are allocated at government formation as a given. Moreover, the explanatory variables employed in these studies are static in the sense that they typically do not change until the next cabinet formation or election. Yet given that these works try to understand portfolio allocation at coalition formation, this seems unproblematic from a dynamic point of view. These studies are also silent about the process of distribution among the coalition partners and de facto assume that each portfolio is allocated to a party independently from the allocation of the other portfolios.

Looking at changes in the allocation of portfolios would speak to the theoretical ideas of re-negotiation of the coalition deal as a response to external shocks (Laver and Shepsle Citation1998; Lupia and Strøm Citation1995). To the best of our knowledge, no study has done so, perhaps because the empirical evidence (Bergman et al. Citation2019, Citation2021b; Müller and Strøm Citation2000) seems to suggest that such shifts occur quite rarely. Shifts of whole ministries, of course, are very strong signals and probably more than leaders of parties that are deprived of portfolios can afford.

Yet the contribution of Meyer et al. (Citation2023) shows that changes in portfolio design in sitting governments occur quite frequently. Shifting smaller jurisdictions between ministries is certainly less visible than changes in the party control of ministries. But, as the authors explain, the dynamic may be driven more by other concerns than redistribution among the coalition partners. In any case, there are considerable dynamics below the level of full portfolios within government terms and this research has begun to unravel these processes.

Ecker et al. (Citation2015) and Raabe and Linhart (Citation2015) chose different strategies to make their attempts at understanding which portfolios go to which parties both more realistic and more dynamic by modelling the process of portfolio allocation. Earlier studies have implicitly assumed that parties make decisions on the allocation of the full set of portfolios in one take. In contrast, Ecker et al. (Citation2015) and Raabe and Linhart (Citation2015) theorise that coalition parties allocate portfolios sequentially. Based on qualitative accounts, the former authors assume that parties decide on the allocation of key cabinet positions before they turn to less important ones. Ecker et al. (Citation2015) find that the prediction success for the allocation of individual cabinet positions is considerably higher when enacting a sequential bargaining process compared to the allocation of the full set of portfolios.

Carroll and Cox (Citation2007) connect portfolio allocation to the electoral stage of the coalition life cycle. They explain the degree of proportionality of portfolio allocation by the parties’ pre-electoral coalition building behaviour. One goal of such alliances is to re-direct competition – from competition between the alliance partners (where ideological proximity might promise easy gains) to competition with external parties. If successful, this strategy might boost the total vote of the pre-electoral coalition. To motivate the parties to campaign harder and hence increase their alliance’s chance of winning, the partners promise a fair division of portfolios among themselves. Carroll and Cox (Citation2007) indeed find portfolio allocation to be significantly more proportional in those government coalitions which are based on pre-electoral agreements.

Much work on portfolio allocation focuses on Gamson’s law, trying to understand the mechanisms underlying this very strong empirical regularity and deviations from it. Of those, Falcó-Gimeno’s study (2012) is particularly relevant in our context, focusing on dynamics, as it sheds light on the long-term effects of parties being out of office. As he demonstrates, such ‘deprivation’ makes political parties willing to make greater concessions and hence accept a share of offices that is lower than the party’s contribution to the coalition’s parliamentary base.

Dynamics at the governance stage

The turn to coalition governance as a central issue of coalition politics since the beginning of the 1990s is motivated by its importance for understanding coalition politics tout court (Laver and Shepsle Citation1990a). Parties’ anticipation of the policy outputs under different government formulas drives government formation and the actual working of coalitions is of critical importance for their duration, policy outputs, electoral performance, and possible renewal.

While the ministerial government model, which assumes that ministers have quasi dictatorial power and implement their respective party’s policy, was the first explicitly stated model of coalition governance, it was soon challenged by other models. One is the coalition compromise model – with coalition parties agreeing on a joint programme via substantive compromise, the implementation of which is then monitored and enforced by the coalition parties (Martin and Vanberg Citation2014). Another model is that of prime ministerial government built on a dominant prime minister endowed with strong formal powers and leading a dominant party (Bergman et al. Citation2019, Citation2021b). While the latter type per se does not look very ‘coalitional’, it is empirically relevant in some countries and time periods. A final model, the parliamentary median model comes with a strong theoretical foundation in the median voter theorem (Black Citation1987), predicting that government policy will approximate this position (Laver and Schofield Citation1990). These different models capture how governments (and legislative majorities) make decisions and predict what kind of policy outputs the government will produce. Importantly, these models capture the dynamics of governing and making policies. In a sense, they emerge from the daily interactions of the coalition partners.

Much empirical research has focused on the institutional manifestations of these daily interactions within the coalition. One group of studies is concerned with the establishment of the institutions of coalition governance, assuming that rational politicians build such institutions to actually use them to enforce the coalition compromise. While in some instances coalition governance mechanisms emerge while the government is in office, typically these institutions are designed in the government formation process and meant to remain in place for the entire lifetime of the coalition. The vast majority of these studies focus on individual governance institutions – either private ones, designed and set up by the coalition parties, or constitutional ones, adapted to the needs of coalition governance. Beginning with the private institutions, various studies have researched when coalitions turn to write formal agreements (Müller and Strøm Citation2008), how comprehensive these agreements are, and which functions they may serve (Eichorst Citation2014; Indridason and Kristinsson Citation2013), and which factors drive the emphasis on specific policy content (Klüver and Bäck Citation2019; Klüver et al. Citation2023; Krauss and Kluever Citation2022). Other research has focused on the establishment of coalition committees and other inter-party bodies for mutual scrutinising and consensus finding (Andeweg and Timmermans Citation2008).

A few publications investigate the actual working of the mechanisms of coalition governance. Examples are studies on the implementation of conflict containment through coalition agreements (see Moury Citation2013; Moury and Timmermans Citation2013; Timmermans Citation2006) and coalition bodies (Miller Citation2010; Miller and Müller Citation2010). Yet the scope of these studies is severely limited in terms of the countries and governments covered.

The private institutions of coalition governance emerge from the purposive actions of the coalition parties. It is their very existence that reveals information on the process of governing. Additional insights into the actual working of coalitions can be gained from specific patterns of appointments to positions in the political executive and the parliamentary committee system. In that vein, various studies have focused on appointments that should allow coalition parties to monitor their coalition partners’ ministers and negotiate policy initiatives so that they respect the coalition compromise. The relevant appointments are to the positions of (watchdog) junior ministers (Lipsmeyer and Pierce Citation2011; Thies Citation2001), ministers in substantively related departments (Fernandes et al. Citation2016), and committee chairs (Carroll and Cox Citation2012).

Other studies on coalition governance build on observing actual interactions of coalition parties in the formal institutions. Important examples include patterns of behaviour in legislative agenda setting (König et al. Citation2022; Martin Citation2004), scrutinising legislative bills in parliamentary committees (Fortunato Citation2019b; Martin and Vanberg Citation2004, Citation2005, Citation2020), assigning joint ministerial responsibility for policy issues (Klüser Citation2022; Klüser and Breunig Citation2023), and policing the ministers of the coalition partner through parliamentary questions (Höhmann and Sieberer Citation2020; Martin and Whitaker Citation2019). These studies also show how coalition parties change their behaviour over the electoral cycle. Typically, they show that the parties’ behaviour becomes more competitive the closer to the next election. In a similar vein, Imre et al. (Citation2023) aim to understand the intra-coalition mood by studying patterns of applause by MPs of the coalition parties for speakers of their partner(s) in parliamentary debates, finding differences between different coalitions and over the electoral cycle.

The studies cited mostly provide indirect evidence for the relative importance of the various models of coalition governance, as important parts of the dynamic process of policy production remain unobserved (Martin and Vanberg Citation2020). A few studies have thus turned to focus on government outputs, which should significantly differ depending on the coalition governance model at work. Ultimately, a government’s policy output is probably the most critical aspect of its performance for voters and politicians alike. In that vein, Becher (Citation2010) and Martin and Vanberg (Citation2014) focus on changes in the levels of social policy entitlements while Bäck et al. (Citation2022b) focus on the policy measures enacted. These studies condense the dynamics of policy processes over several years into a few summary indicators that allow inferences to be made on the prevailing model of coalition governance.

Relating to that line of research, Bergman et al. (Citation2023) investigate whether written coalition agreements increase the policy-making productivity of multiparty governments. They investigate their claim by analysing data on economic reform measures adopted by national governments in 11 Western European countries over a 40-year period (1978–2017), based on a coding of country reports issued by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The authors show that coalition agreements foster policy productivity in minimal winning cabinets, but play a weaker role in minority and surplus governments. Moreover, coalition agreements limit the negative effect of intra-cabinet ideological conflict on reform productivity. Their results show that coalition contracts help parties to overcome the risk of a policy stalemate traditionally ascribed to multi-party government.

A few other studies ask how coalition parties communicate with their rank-and-file and the electorate at large over the electoral cycle. In so doing, coalition parties must balance the need to compromise in the coalition with the need to maintain the party profile. For that purpose, Martin and Vanberg (Citation2008) infer party-position-taking from the volume of communication in parliamentary plenary speeches in Germany and the Netherlands. Sagarzazu and Klüver (Citation2017), in turn, use German parties’ press releases to analyse this question. These studies demonstrate that the individual parties’ concerns for emphasising their own profile become more prominent the closer the next election comes and hence demonstrate strategic change in party behaviour over the electoral cycle. While limited in geographical and time scope, these pioneering studies build a bridge to the electoral stage in the coalition life cycle.

Coalition governance is also a natural candidate for dynamics from one coalition cycle to the next as coalition parties may learn from previous experiences and readopt mechanisms that have worked and abstain from using ones that have proved ineffective. Likewise, system learning may occur so that parties adopt mechanisms that had been used by other parties in office before. Similarly, coalition parties in new democracies (such as those in Eastern Europe) or in new coalition systems (such as the UK) are predisposed to learning from the experience in older democracies or coalition systems (Bergman et al. Citation2019). Yet such dynamics still lack a rigorous analysis.

Dynamics at the termination stage

Most work on government stability focuses on cabinet duration, that is, how long governments last, or ‘survive’. Termination enters this field of research only indirectly as it determines a cabinet’s end date. Durable governments terminate at or close towards the end of the constitutional inter-election period. Empirical research has tried to explain actual government duration with the help of variables, such as the parties’ legislative strength, the ideological structure of party competition, and the institutional environment (see Grofman and van Roozendaal Citation1997). These variables typically remain unchanged over the lifetime of the cabinet. Although static in that sense, work on the institutional framework structuring cabinet termination and parliamentary dissolution stand out in terms of understanding coalition dynamics. Drawing on theoretical work by Lupia and Strøm (Citation1995), Schleiter and Morgan-Jones (Citation2009), and Strøm and Swindle (Citation2002) model how different sets of institutional rules structure the coalition actors’ interactions and test their hypotheses with the help of observable implications with aggregate data.

Starting with the work by Warwick (Citation1992, Citation1994), dynamics have entered the study of government duration more directly via economic indicators. For example, inflation rates, and unemployment rates change constantly over a cabinet’s life cycle. Including these variables has incorporated the dynamics of the world surrounding the coalition (Druckman Citation2008) with the theoretical expectation being that economic discomfort tends to shorten the lifetime of governments (also see e.g. Damgaard Citation2008; Hellström and Walther Citation2019; Saalfeld Citation2008). In this context, some studies have also modelled dynamics directly by including time-varying measurements of the state of economy (e.g. Hellström and Walther Citation2019).

Another step towards making analyses of government duration more dynamic is by integrating mechanisms of coalition governance, assuming that well-thought-out institutions help to contain or resolve internal conflict and hence stabilise the coalition and contribute to its survival – an expectation that is indeed indicated by some analyses of cabinet duration (Krauss Citation2018; Saalfeld Citation2008, Citation2009). While it is true that the governance mechanisms are mostly established at the beginning of the coalition’s term, and in most instances in the process of negotiating the coalition deal, they emerge from the interactions of the coalition partners and not their initial ‘endowments’. They thus capture some of the real dynamics in coalition politics.

Damgaard (Citation2008) studies termination events, trying to understand why some governments end at the end of the constitutional inter-election period and others considerably earlier and, if the latter applies, whether the governments fall over internal conflict or suffer parliamentary defeat. In a similar manner to the studies of cabinet duration just cited, Damgaard’s study employs some variables that reflect actual interactions between the coalition partners. Specifically, he finds that strong mutual commitments to coalition discipline help to avoid conflictual termination, while written coalition agreements are of little relevance to maintaining coalition governments in office. As we have already discussed, the parties’ behaviour in terminating a coalition is consequential as former partners tend to shun these parties (Tavits Citation2008) and their bargaining power seems reduced even vis-à-vis other parties (Warwick Citation2012).

Focusing on what happens after termination, more specifically on when governments are able to return to power, Pedrazzani and Zucchini (Citation2023) classify non-electoral replacements of cabinets according to the degree of ministerial turnover. They show that new cabinets are often similar to their predecessors and hypothesise that the likelihood of cabinets ‘reincarnating’ is greater under certain circumstances. Analysing post-war cabinets in Western Europe, they show that governments are able to return to power almost untouched after their termination if they are oversized, if the opposition is far from the legislative median voter, and if inflation grows during a government’s tenure.

Conclusion

Little more than a decade after coalition research had taken root in political science, first concerns were issued that theory and existing empirical work were static. Although coalition research has turned out to be a productive field, the static criticism has been raised several times, lastly in 2008. Since then, this critique seems to have lost much of its bite. Our review of coalition research suggests that there has been great progress made in the field, in terms of research becoming dynamic and more realistic. In this introductory essay, we have described many studies that have advanced coalition research in terms of making it more dynamic.

Specifically, we have given examples of some studies that capture the dynamic in coalition politics in three different but overlapping ways. First, we have focused on work that is not confined to employing the ‘initial endowments’ of coalition parties (such as parliamentary seats or left–right placements) in its analyses. While these endowments, at least in conventional measurement, only vary from one election to another, we have focused on studies that also draw on the actual interactions of coalition actors and hence allow episodes of coalition politics to be looked into rather than making inferences from what was new at the starting gate.

Second, drawing in particular on the turn to coalition governance from 1990 (Laver and Shepsle Citation1990a, Citation1990b), we have focused on studies that try to explain what occurs at one stage in the coalition life cycle compared with what happened earlier in the same cycle, and how the expectations of coalition actors about what lies ahead in the same cycle influence their behaviour (Strøm et al. Citation2008). Third, pushing the cycle-idea further, coalition research becomes dynamic when it connects adjacent cycles. Such work draws on the experiences coalition actors make in one cycle to explain their behaviour in the new cycle. A fourth way to look at dynamics would be the long-cycle perspective, focusing on critical junctures in coalition politics, such as the beginning or ending, era-defining coalition formulas. Such analyses are the domain of country studies (e.g. Bergman et al. Citation2019, Citation2021b; Müller and Strøm Citation2000).

The articles in this special issue clearly contribute to this agenda of taking a dynamic approach towards the study of coalition politics. They for example show how commitments made at the electoral stage of the coalition life cycle influence both how long it takes to form a government and how ministerial portfolios are distributed. They also show how historical patterns of cooperation between parties in a political system influence government formation and portfolio design, and in which institutional contexts incumbency matters the most for government formation, and when cabinets are likely to be ‘reborn’ in a similar form. In addition, they contribute to our understanding of the coalition governance stage of the life cycle, suggesting that agreements made during the formation stage influence policy making, and such agreements are also important for the formation of minority governments. Even though more work is needed in making coalition research dynamic, these theoretical and empirical contributions increase our understanding of coalition politics in parliamentary democracies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Wolfgang C. Müller

Wolfgang C. Müller is a Professor of Democratic Governance, Department of Government, University of Vienna, and is retired from teaching and administration. He has published extensively on political parties, political institutions, and coalition politics, including articles in journals, such as the British Journal of Political Science, Comparative Political Studies, and the European Journal of Political Research and books including Coalition Governments in Western Europe (co-edited with Kaare Strøm, OUP 2000), Cabinets and Coalition Bargaining (co-edited with Kaare Strøm and Torbjörn Bergman, OUP 2008), and Coalition Governance in Central Eastern Europe (co-edited with Torbjörn Bergman and Gabriella Ilonszki, OUP 2019). [[email protected]]

Hanna Bäck

Hanna Bäck is Professor of Political Science at Lund University. Her research mainly focuses on political parties and government formation in parliamentary democracies. She has published extensively in highly ranked journals on these topics, for example, in the British Journal of Political Science, Comparative Political Studies, and the European Journal of Political Research. She is one of the co-editors of the recently published book – Coalition Governance in Western Europe (co-edited with Torbjörn Bergman and Johan Hellström, OUP, 2021) and co-author of Coalition Agreements as Control Devices (with Heike Klüver and Svenja Krauss, OUP, 2023). [[email protected]]

Johan Hellström

Johan Hellström is Associate Professor of Political Science at Umeå University. His research focuses on political parties, coalition politics, and democratic representation in Europe. He has published his recent work in journals, such as West European Politics, Political Science Research and Methods, and the European Journal of Political Research. He is one of the co-editors of the recently published book – Coalition Governance in Western Europe (co-edited with Hanna Bäck and Torbjörn Bergman, OUP, 2021) and Co-PI for The Representative Democracy Data Archive. [[email protected]]

References

- Andeweg, Rudy B., Lieven De Winter, and Patrick Dumont, eds. (2011). Puzzles of Government Formation. London: Routledge.

- Andeweg, Rudy B., and Arco Timmermans (2008). ‘Conflict Management in Coalition Government’, in Kaare Strøm, Wolfgang C. Müller, and Torbjörn Bergman (eds.), Cabinet Governance: Bargaining and the Cycle of Democratic Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 269–300.

- Axelrod, Robert. (1970). Conflict of Interest. Chicago: Markham.

- Barlow, Nick, and Tim Bale (2021). ‘The United Kingdom: When Coalition Meets the Westminster Model, Who Wins?’, in Torbjörn Bergman, Hanna Bäck, and Johan Hellström (eds.), Coalition Governance in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 611–39.

- Bäck, Hanna. (2008). ‘Intra-Party Politics and Coalition Formation: Evidence from Swedish Local Government’, Party Politics, 14:1, 71–89.

- Bäck, Hanna, Marc Debus, and Patrick Dumont (2011). ‘Who Gets What in Coalition Governments? Predictors of Portfolio Allocation in Parliamentary Democracies’, European Journal of Political Research, 50:4, 441–78.

- Bäck, Hanna, Marc Debus, and Michael Imre (2022a). ‘Populist Radical Parties, Pariahs, and Coalition Bargaining Delays’, Party Politics. https://doi.org/10.1177/13540688221136109.

- Bäck, Hanna, and Patrick Dumont (2007). ‘Combining Large-n and Small-n Strategies: The Way Forward in Coalition Research’, West European Politics, 30:3, 467–501.

- Bäck, Hanna, Wolfgang C. Müller, Mariyana Angelova, and Daniel Strobl (2022b). ‘Ministerial Autonomy, Parliamentary Scrutiny and Government Reform Output in Parliamentary Democracies’, Comparative Political Studies, 55:2, 254–86.

- Bäck, Hanna, Johan Hellström, Johannes Lindvall, and Jan Teorell (2023). ‘Pre-Electoral Coalitions, Familiarity, and Delays in Government Formation’, West European Politics. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2023.2200328.

- Becher, Michael. (2010). ‘Constraining Ministerial Power: The Impact of Veto Players on Labor Market Reforms in Industrial Democracies, 1973–2000’, Comparative Political Studies, 43:1, 33–60.

- Beckman, Tristin, and Petra Schleiter (2020). ‘Opportunistic Election Timing, a Compliment or Substitute for Economic Manipulation?’, The Journal of Politics, 82:3, 1127–41.

- Bergman, Matthew, Mariyana Angelova, Hanna Bäck, and Wolfgang C. Müller (2023). ‘Coalition Agreements and Governments’ Policy-Making Productivity’, West European Politics. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2022.2161794.

- Bergman, Torbjörn, Hanna Bäck, and Johan Hellström (2021a). ‘Coalition Governance in Western Europe’, in Torbjörn Bergman, Hanna Bäck, and Johan Hellström (eds.), Coalition Governance in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1–14.

- Bergman, Torbjörn, Hanna Bäck, and Johan Hellström, eds. (2021b). Coalition Governance in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bergman, Torbjörn, Gabriella Ilonszki, and Wolfgang C. Müller, eds. (2019). Coalition Governance in Central Eastern Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Black, Duncan. (1987). The Theory of Committees and Elections. Boston: Kluwer.

- Browne, Eric C., and Karen A. Feste (1975). ‘Qualitative Dimensions of Coalition Payoffs: Evidence from European Party Governments, 1945–1970’, American Behavioral Scientist, 18:4, 530–56.

- Browne, Eric C., and Mark N. Franklin (1973). ‘Aspects of Coalition Payoffs in European Parliamentary Democracies’, American Political Science Review, 67:2, 453–69.

- Budge, Ian, and Hans Keman (1990). Parties and Democracy: Coalition Formation and Government Functioning in Twenty States. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Carroll, Royce, and Gary W. Cox (2007). ‘The Logic of Gamson’s Law: Pre-Electoral Coalitions and Portfolio Allocations’, American Journal of Political Science, 51:2, 300–13.

- Carroll, Royce, and Gary W. Cox (2012). ‘Shadowing Ministers: Monitoring Partners in Coalition Governments’, Comparative Political Studies, 45:2, 220–36.

- Ceron, Andrea. (2019). Leaders, Factions and the Game of Intra-Party Politics. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Damgaard, Erik. (2008). ‘Cabinet Termination’, in Kaare Strøm, Wolfgang C. MüLler, and Torbjörn Bergman (eds.), Cabinets and Coalition Bargaining: The Democratic Life Cycle in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 301–26.

- Däubler, Thomas, Marc Debus, and Alejandro Ecker (2022). ‘Party Campaign Statements and Portfolio Allocation in Coalition Governments’, West European Politics. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2022.2140397.

- Debus, Marc. (2009). ‘Pre-Electoral Commitments and Government Formation’, Public Choice, 138:1–2, 45–64.

- De Marchi, Scott, and Michael Laver (2023). The Governance Cycle in Parliamentary Democracies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- De Swaan, Abram. (1973). Coalition Theories and Cabinet Formations. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- De Winter, Lieven, and Patrick Dumont (2008). ‘Uncertainty and Complexity in Cabinet Formation’, in Kaare Strøm, Wolfgang C. Müller, and Torbjörn Bergman (eds.), Cabinet Governance: Bargaining and the Cycle of Democratic Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 123–57.

- Diermeier, Daniel, and Peter van Roozendaal (1998). ‘The Duration of Cabinet Formation Processes in Western Multi-Party Democracies’, British Journal of Political Science, 28:4, 609–26.

- Dodd, Lawrence C. (1976). Coalitions in Parliamentary Government. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Druckman, James N. (2008). ‘Dynamic Approaches to Studying Parliamentary Coalitions’, Political Research Quarterly, 61:3, 479–83.

- Druckman, James N., and Paul V. Warwick (2005). ‘The Missing Piece: Measuring Portfolio Salience in Western European Parliamentary Democracies’, European Journal of Political Research, 44:1, 17–42.

- Dumont, Patrick, Albert Falcó-Gimeno, Indridi H. Indridason, and Daniel Bischof (2023). ‘Pieces of the Puzzle: Coalition Formation and Preference Compatibility’, West European Politics. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2023.2234236.

- Dunleavy, Patrick with Simon Bastow (2001). ‘Modelling Coalitions That Cannot Coalesce: A Critique of the Laver-Shepsle Approach’, West European Politics, 24:1, 1–26.

- Ecker, Alejandro, and Thomas M. Meyer (2020). ‘Coalition Bargaining Duration in Multiparty Democracies’, British Journal of Political Science, 50:1, 261–80.

- Ecker, Alejandro, Thomas M. Meyer, and Wolfgang C. Müller (2015). ‘The Distribution of Individual Cabinet Positions in Coalition Governments: A Sequential Approach’, European Journal of Political Research, 54:4, 802–18.

- Eichorst, Jason. (2014). ‘Explaining Variation in Coalition Agreements: The Electoral and Policy Motivations for Drafting Agreements’, European Journal of Political Research, 53:1, 98–115.

- Falcó-Gimeno, Albert. (2012). ‘Parties Getting Impatient: Time Out of Office and Portfolio Allocation in Coalition Governments’, British Journal of Political Science, 42:2, 393–411.

- Fernandes, Jorge M., Florian Meinfelder, and Catherine Moury (2016). ‘Wary Partners: Strategic Portfolio Allocation and Coalition Governance in Parliamentary Democracies’, Comparative Political Studies, 49:9, 1270–300.

- Fortunato, David. (2019a). ‘The Electoral Implications of Coalition Policy Making’, British Journal of Political Science, 49:1, 59–80.

- Fortunato, David. (2019b). ‘Legislative Review and Party Differentiation in Coalition Governments’, American Political Science Review, 113:1, 242–7.

- Fortunato, David. (2021). The Cycle of Coalition. How Parties and Voters Interact under Coalition Governance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Fortunato, David, and Randolph T. Stevenson (2013). ‘Perceptions of Partisan Ideologies: The Effect of Coalition Participation’, American Journal of Political Science, 57:2, 459–77.

- Franklin, Mark N., and Thomas T. Mackie (1983). ‘Familiarity and Inertia in the Formation of Governing Coalitions in Parliamentary Democracies’, British Journal of Political Science, 13:3, 275–98.

- Gamson, William A. (1961). ‘A Theory of Coalition Formation’, American Sociological Review, 26:3, 373–82.

- Gianetti, Daniela, and Kenneth Benoit, eds. (2009). Intra-Party Politics and Coalition Governments. London: Routledge.

- Giannetti, Daniela, and Michael Laver (2001). ‘Party System Dynamics and the Making and Breaking of Italian Governments’, Electoral Studies, 20:4, 529–53.

- Golder, Sona Nadenochek (2006). The Logic of Pre-Electoral Coalition Formation. Columbus: Ohio State University Press.

- Golder, Sona N. (2010). ‘Bargaining Delays in the Government Formation Process’, Comparative Political Studies, 43:1, 3–32.

- Greene, Zackary, and Matthias Haber (2016). ‘Leadership Competition and Disagreement at Party National Congresses’, British Journal of Political Science, 46:3, 611–32.

- Greene, Zackary, Nathan Henceroth, and Christian B. Jensen (2021). ‘The Cost of Coalition Compromise: The Electoral Effects of Holding Salient Portfolios’, Party Politics, 27:4, 827–38.

- Grofman, Bernard, and Peter van Roozendaal (1997). ‘Review Article: Modeling Cabinet Durability and Termination’, British Journal of Political Science, 27:3, 419–51.

- Hellström, Johan, and Daniel Walther (2019). ‘How is Government Stability Affected by the State of the Economy? Payoff Structures, Government Type and Economic State’, Government and Opposition, 54:2, 280–308.

- Hellström, Johan, Torbjörn Bergman, and Hanna Bäck (2021). Party Government in Europe Database (PAGED). Main sponsor: Riksbankens Jubileumsfond (IN150306:1). https://repdem.org

- Hjermitslev, Ida B. (2020). ‘The Electoral Cost of Coalition Participation: Can Anyone Escape?’, Party Politics, 26:4, 510–20.

- Höhmann, Daniel, and Ulrich Sieberer (2020). ‘Parliamentary Questions as a Control Mechanism in Coalition Governments’, West European Politics, 43:1, 225–49.

- Ibenskas, Raimondas. (2016). ‘Understanding Pre-Electoral Coalitions in Central and Eastern Europe’, British Journal of Political Science, 46:4, 743–61.

- Imre, Michael, Alejandro Ecker, Thomas M. Meyer, and Wolfgang C. Müller (2023). ‘Coalition Mood in European Parliamentary Democracies’, British Journal of Political Science, 53:1, 104–21.

- Indridason, Indridi H., and Gunnar Helgi Kristinsson (2013). ‘Making Words Count: Coalition Agreements and Cabinet Management’, European Journal of Political Research, 52:6, 822–46.

- Klüser, K. Jonathan. (2022). ‘Keeping Tabs Through Collaboration? Sharing Ministerial Responsibility in Coalition Governments’, Political Science Research and Methods. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2022.31.

- Klüser, K. Jonathan, and Christian Breunig (2023). ‘Ministerial Policy Dominance in Parliamentary Democracies’, European Journal of Political Research, 62:2, 633–44.

- Klüver, Heike, and Hanna Bäck (2019). ‘Coalition Agreements, Issue Attention, and Cabinet Governance’, Comparative Political Studies, 52:13–14, 1995–2031.

- Klüver, Heike, Hanna Bäck, and Svenja Krauss (2023). Coalition Agreements as Control Devices: Coalition Governance in Western and Eastern Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Klüver, Heike, and Jae-Jae Spoon (2020). ‘Helping or Hurting? How Governing as a Junior Coalition Partner Influences Electoral Outcomes’, The Journal of Politics, 82:4, 1231–42.

- König, Thomas, Nick Lin, Xiao Lu, Thago N. Silva, Nikoleta Yordanova, and Galina Zudenkova (2022). ‘Agenda Control and Timing of Bill Initiation: A Temporal Perspective on Coalition Governance in Parliamentary Democracies’, American Political Science Review, 116:1, 231–48.

- Krauss, Svenja. (2018). ‘Stability Through Control? The Influence of Coalition Agreements on the Stability of Coalition Cabinets’, West European Politics, 41:6, 1282–304.

- Krauss, Svenja, and Heike Kluever (2022). ‘Formation and Coalition Governance: The Effect of Portfolio Allocation on Coalition Agreements’, Government and Opposition. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2021.68.

- Laver, Michael (1974). ‘Dynamic Factors in Government Coalition Formation’, European Journal of Political Research, 2:3, 259–70.

- Laver, Michael (1986). ‘Between Theoretical Elegance and Political Reality: Deductive Models and Cabinet Coalitions in Europe’, in Geoffrey Pridham (ed.), Coalition Behaviour in Theory and Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 32–44.

- Laver, Michael (1998). ‘Theories of Government Formation’, Annual Review of Political Science, 1:1, 1–25.

- Laver, Michael (1989). ‘Party Competition and Party System Change’, Journal of Theoretical Politics, 1:3, 301–24.

- Laver, Michael (2003). ‘Government Termination’, Annual Review of Political Science, 6:1, 23–40.

- Laver, Michael (2008). ‘Governmental Politics and the Dynamics of Multiparty Competition’, Political Research Quarterly, 61:3, 532–6.

- Laver, Michael, and Kenneth Benoit (2003). ‘The Evolution of Party Systems between Elections’, American Journal of Political Science, 47:2, 215–33.

- Laver, Michael, and Junko Kato (2001). ‘Dynamic Approaches to Government Formation and the Generic Instability of Decisive Structures in Japan’, Electoral Studies, 20:4, 509–27.

- Laver, Michael J., and Kenneth A. Shepsle (1990a). ‘Coalitions and Cabinet Government’, American Political Science Review, 84:3, 873–90.

- Laver, Michael J., and Kenneth A. Shepsle (1990b). ‘Government Coalitions and Intraparty Politics’, British Journal of Political Science, 20:4, 489–507.

- Laver, Michael, and Kenneth A. Shepsle (1996). Making and Breaking Governments. Cabinets and Legislatures in Parliamentary Democracies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Laver, Michael, and Kenneth A. Shepsle (1998). ‘Events, Equilibria, and Government Survival’, American Journal of Political Science, 42:1, 28–54.

- Laver, Michael J., and Norman Schofield (1990). Multiparty Government. The Politics of Coalition in Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lipsmeyer, Christine S., and Heather Nicole Pierce (2011). ‘The Eyes That Bind: Junior Ministers as Oversight Mechanisms in Coalition Governments’, The Journal of Politics, 73:4, 1152–64.

- Luebbert, Gregory M. (1986). Comparative Democracy. Policymaking and Governing Coalitions in Europe and Israel. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Lupia, Arthur, and Kaare Strøm (1995). ‘Coalition Termination and the Strategic Timing of Parliamentary Elections’, American Political Science Review, 89:3, 648–65.

- Mair, Peter. (1997). Party System Change. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Martin, Lanny W. (2004). ‘The Government Agenda in Parliamentary Democracies’, American Journal of Political Science, 48:3, 445–61.

- Martin, Lanny W., and Randolph T. Stevenson (2001). ‘Government Formation in Parliamentary Democracies’, American Journal of Political Science, 45:1, 33–50.

- Martin, Lanny W., and Georg Vanberg (2003). ‘Wasting Time? The Impact of Ideology and Size on Delay in Coalition Formation’, British Journal of Political Science, 33:02, 323–32.

- Martin, Lanny W., and Georg Vanberg (2004). ‘Policing the Bargain: Coalition Government and Parliamentary Scrutiny’, American Journal of Political Science, 48:1, 13–27.

- Martin, Lanny W., and Georg Vanberg (2005). ‘Coalition Policymaking and Legislative Review’, American Political Science Review, 99:1, 93–106.

- Martin, Lanny W., and Georg Vanberg (2008). ‘Coalition Government and Political Communication’, Political Research Quarterly, 61:3, 502–16.

- Martin, Lanny W., and Georg Vanberg (2014). ‘Parties and Policymaking in Multiparty Governments: The Legislative Median, Ministerial Autonomy, and the Coalition Compromise’, American Journal of Political Science, 58:4, 979–96.

- Martin, Lanny W., and Georg Vanberg (2020). ‘Coalition Government, Legislative Institutions, and Public Policy in Parliamentary Democracies’, American Journal of Political Science, 64:2, 325–40.

- Martin, Shane, and Richard Whitaker (2019). ‘Beyond Committees: Parliamentary Oversight of Coalition Government in Britain’, West European Politics, 42:7, 1464–86.

- Mershon, Carol. (2002). The Costs of Coalition. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Merton, Robert K. (1968). Social Theory and Social Structure. New York: Free Press.

- Meyer, Thomas M., Ulrich Sieberer, and David Schmuck (2023). ‘Rebuilding the Coalition Ship at Sea: How Uncertainty and Complexity Drive the Reform of Portfolio Design in Coalition Cabinets’, West European Politics. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2023.2169512.

- Miller, Bernhard. (2010). Der Koalitionsausschuss. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- Miller, Bernhard, and Wolfgang C. Müller (2010). ‘Managing Grand Coalitions: Germany 2005–09’, German Politics, 19:3–4, 332–52.

- Moury, Catherine. (2013). Coalition Government and the Party Mandate. London: Routledge.