Abstract

This introduction to the special issue recalls the alarm raised in EU capitals and Brussels after the UK’s in-out referendum delivered a Leave vote in June 2016. The fear was of a domino effect and the further fragmentation of an already divided EU. Seven years later, it is clear that there was rapid attrition of Eurosceptic triumphalism, and the EU-27 showed remarkable unity. This required a sustained collective effort to contain a membership crisis and maintain the EU polity. Yet, the issue contributors challenge the notion that the alarm was unfounded and explain why this counter-factual did not materialise, even though potential for future membership crises of different sorts was revealed. Theoretically, this supports an understanding of the EU as a polity that is fragile, yet able to assert porous borders, exercise authority over a diverse membership, and mobilise a modicum of loyalty when the entire integration regime is under threat.

The outcome of the UK’s in-out referendum in June 2016 rang alarm bells across European Union (EU) capitals and in Brussels. The EU’s unidirectional historical trajectory of ever-expanding union had been subject to a first major reverse. A domino effect seemed to be in the offing, given that vocal Eurosceptic movements firmly established themselves in multiple member states’ party systems. Yet, the opposite happened. There was neither contagion, nor did the EU become more internally fragmented. Instead, there has been a marked attrition of Eurosceptic triumphalism and copycat wanderlust on the radical right. The EU-27 showed surprisingly comprehensive unity that survived the next stress test, the Covid-19 pandemic that hit Europe during the final stages of the Brexit negotiations. Fending off a domino effect and forging unity in adversity arguably required a sustained collective effort to contain what had the potential to become a more wholesale crisis of EU membership.

The contributors to this special issue challenge any notion that alarmism in European capitals was completely unfounded. Brexit should be understood as a critical juncture for the EU in which a path to disintegration became visible but was contained, and that has had formative impacts on Euroscepticism downstream, both inside and outside the EU. Our contributions collectively examine the kind of crisis that Brexit represented for the European polity, its dynamics and uniqueness in comparative perspective, and the extent to which it should even be considered an existential crisis at all.

This discussion has broader theoretical implications. We take Brexit as evidence for the post-functionalist condition that elected governments and the EU have found themselves in for quite some time (Hooghe and Marks Citation2009, Citation2018). EU policy making, which was once a rather esoteric affair of which national voters took little notice, can now quickly become headline news, piquing the interest of vocal critics outside expert circles and potentially polarising segments of society (Hutter and Kriesi Citation2019; Schmidt Citation2019). The EU’s default setting of ‘permissive consensus’ that was characteristic of its policy making during previous eras has been replaced by a ‘constraining dissensus’, and if not heeded, this can easily escalate into a full-blown crisis of the EU polity proper. Brexit seems to showcase for this theory in action, except that escalation remained confined to the UK, and was actively averted elsewhere. This suggests that post-functionalism is missing a complement on the supply side of EU policy making: if members of the Commission and national executives take post-functionalist insights seriously, they are bound to consider counter-measures. We argue that Brexit was a challenge that found the EU prepared. The UK’s unprecedented step ended the phase in which the EU proved that it could defend its raison d’être, by juxtaposing the merits of its integration regime against the alternative of non-membership. This argument builds on post-functionalism but also takes it beyond noting a political constraint on European integration.

The following sections tease out both idiosyncratic and generalisable circumstances that led to the British departureFootnote1, to identify the fault lines where EU membership crises in other guises do or can still occur. Theoretically, this supports an understanding of the EU as a polity that is fragile, yet able to assert porous borders, exercise authority over a diverse membership to show unity and mobilise loyalty when the integration regime is under threat (Ferrera et al. Citation2021). But it cannot be taken for granted that EU polity maintenance will always succeed. It must be made to succeed. We outline next what the contributors in this special issue identify as key for the politics and policy of containment, discussing the implications of a ‘membership crisis that wasn’t’ for the EU as a polity. The final section concisely presents the contribution of the articles and concludes.

The shock and puzzle of Brexit

In accounts of various European crises over recent years, Brexit is disputed territory. While the Euro area and migration crises have assumed ubiquitous ‘crisis’ status in both comparative politics and EU studies scholarship, Brexit is counted alongside them by some but not all accounts.Footnote2 The more distant the system shock of the referendum of 23 June 2016 becomes, the more Brexit appears to be downgraded from existential crisis to an event or process of a type less serious and potentially disruptive.

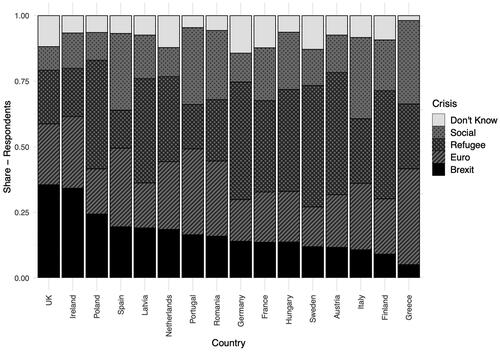

By way of illustration, provides polling data from 2021 showing how Europeans in 16 states perceive different crisis events of the past decade in terms of their disintegrative potential for the EU.Footnote3 Perhaps unsurprisingly, British and Irish respondents saw Brexit as the crisis most likely to threaten the EU’s survival. In all other countries, only a quarter of respondents, or less, consider this to be the case. Brexit lags behind the refugee crisis of 2015–2016 that commands the greatest overall share, the Euro area crisis and a more slow-burning, structural crisis of European unemployment and poverty (Social). Even though Brexit was the only crisis that ended in disintegration, it is now broadly perceived as comparatively less threatening for the EU’s political system. There is significant variation between states, however, and this does not dispel a counterfactual Brexit scenario that could have led to a worse outcome for the EU.

Figure 1. Crisis representing greatest threat to survival of the EU, by country. Source Note: Gallup-SOLID General Survey (Citation2021), survey of 32,800 Europeans in 16 countries (fieldwork: 24 May-19 October 2021). Question: "Thinking about the past decade before the COVID-19 pandemic, the European Union has faced a number of challenges. Which of the following challenges do you think represented the most serious threat to the survival of the European Union?"

Some commentary has portrayed Brexit as a pathology of British politics (Wincott et al. Citation2021; MacLeavy and Jones Citation2021). We examine this claim of British exceptionalism in comparison and specify in which regard Britain is different (Altiparmakis and Kyriazi Citation2023). This leads to further questions on what Brexit reveals about the wider dynamics in EU politics, such as: how and why did Brexit have neither a disintegrative effect on the EU nor a catalytic effect on Euroscepticism in other member states? What pathways for future EU disintegration does it close off and open up? These remain questions of eminent relevance for the future of the European integration process, as it contends with disputes over the accession of Moldova and Ukraine (Euractiv Citation2023), and with politicians’ speculation about formalising multi-tiered terms of membership (Politico Citation2023).

Moreover, Brexit remains a puzzling case for scholars in political economy: the UK, a country with a traditionally liberal outlook, withdrew from an economically beneficial Single Market it had helped to shape for over 40 years. This triggered dire predictions by scholars and officials about the future of the EU’s integration regime (Rosamond Citation2016; Matthijs Citation2017). Our ambition is to take the sound reasoning underpinning these predictions and develop the theoretical premises on which they were based. In line with these accounts, the contributors to this issue do not see Brexit as a blessing in disguise for the EU (see e.g. Collins Citation2017). On the contrary, they describe its destabilising potential and aim to understand the implications of a rupture in a seemingly robust integration process that cannot be reduced to an exceptional case. Before turning to our own accounts, a primer on readings of Brexit helps frame our discussion.

State of the art: Brexit as EU crisis

Some accounts saw the UK’s departure and the procedural challenge of aligning member states to negotiate the terms of exit as potentially corrosive for the EU (Oliver Citation2017). After all, exiting was not just any member state but the third most populous, second largest by GDP and net budget contributions, and one of only two major military powers and permanent UN Security Council members. This immediately opened up a significant hole in the EU’s finances that would have to be plugged by other, reluctant net contributors, while reducing its geopolitical weight (Matthijs Citation2017: 85).

The UK was also a totem of a form of soft Euroscepticism that questioned the orthodoxy of ‘ever closer union’ and in so doing found historical allies in the Council around the EU’s north-western and eastern peripheries (Hix et al. Citation2016). As such, an early report from the European Parliament suggested that it would be ‘difficult, if not impossible’ to establish consensus among the diverse remaining member states during the negotiations that would follow the vote (Guardian 2017). Such a failure would, in turn, allow the UK to demonstrate to others that its preferred form of à la carte exit would be more beneficial than continued membership, with all its associated obligations.

However, the primary hypothesised form of Brexit-inspired disintegration was a domino effect, whereby party systems and public opinion in other member states would coalesce to secure a series of similar votes. Various scholars pointed to the contagion potential of the UK’s move, predicting that it might directly spill over to the remaining EU-27. For example, Martill and Staiger (Citation2018: 2) suggested that ‘homegrown Eurosceptic forces’ will likely feel emboldened by the UK’s step, pursuing either to mimic the UK’s referendum or instead push for fundamental reforms to the EU that may lead to its breakdown.Footnote4 Similarly, Hobolt (Citation2018: 243) argued that ‘the Brexit referendum has illustrated how the lack of public support for the EU can challenge the very foundations of the European project’, and showed with embedded experimental surveys that EU publics were more sensitive to the sovereignty benefits of Brexit than they were to warnings about detrimental economic effects.

This links to a deeper divide in European politics, the emergence of a new cleavage that is restructuring party systems around views on and experiences of interdependence and openness, transnationalism for short (Hooghe and Marks Citation2018; Kriesi et al. Citation2008). This cleavage separates winners and losers of transnationalism that, in turn, informs sentiments towards the EU. Concerns about economic openness and the dangers of European integration are far from confined to the UK (Glencross Citation2018). Many scholars, and not only the usual critics of neoliberal Europe, see this as a consequence of its inherent policy bias in favour of economic freedom at the cost of protection (van Middelaar Citation2019). This is a Brexit variant of Scharpf’s (Citation1999) analysis of the ‘negative integration bias’, the EU’s in-built tendency towards removing market barriers without brokering commensurate social protection. The emergence of populist challenger parties shows the heightened potential for a tipping point, similar to the UK, from constraint on integration to support for disintegration in other countries. After Brexit, scholars thus honed in on the prospects for further exits in a small subset of rich, traditionally social-liberal countries thought to be particularly susceptible. These were typically, but not exclusively Denmark, Sweden, Finland and the Netherlands (De Vries Citation2018; Hix Citation2018; Hobolt Citation2016). These countries, known as the original ‘Frugal Four’, have become a distinct voice of opposition to further fiscal integration.

Brexit invited a process of introspection concerning the democratisation of EU institutions and the completion of integration in areas where the UK was seen as a veto player – most notably the single currency (Matthijs Citation2017: 86). However, the prognosis here again appeared to be glum from the perspective of Europhiles, with the EU polity said to be suffering from perpetual legitimation problems owing to its democratic deficit and weak binding cultural and political European identities (Patomäki Citation2017). Plainly, the EU does not command by most measures even weak federalist powers, and its fundamental image as a means to deliver economic payoffs makes ‘every crisis of competence, every economic slump, […] an existential crisis’ (Isiksel Citation2018: 242).

Why is this so? The crisis experience itself undermines output legitimacy, which is the promise of economic gains as the fundamental rationale of European integration. The gains are not a matter of an aggregate cost-benefit analysis, however, but of public perception and the distribution of it. Crises change this perception. Cini and Verdun (Citation2018) suggest that Brexit, just like every policy crisis, could have taken a centrifugal or a centripetal trajectory. This constitutes the fragility of the polity. In their account, the latter could prevail because ‘[t]here is nothing more unifying than having to show a united front’ (Cini and Verdun Citation2018: 68). Polity maintenance here has a self-fulfilling character.

There are of course those who see the fragility of the EU polity in more fundamental terms, in which Brexit was just ‘the tip of the iceberg’, indicating a much larger potential (Bickerton Citation2018). Potential or actual crises merely give a hint of the political tension between the state and society that the EU polity constitutes. It has set up this tension for, and inside, each of its members by requiring another kind of statehood than that of nations: the obligations of membership dominate all other considerations of self-determination (Bickerton Citation2012). While the EU may have been successful in suppressing these tensions so far, Brexit revealed the limits of this strategy and a first instance of failure. This is a bleak diagnosis that rests, on the one hand, on a degree of steadfast commitment to the EU by political decision-makers that seems implausible. It is as if they had not responded to the populist challenge at all, or only by doubling down, drawing more power to supranational institutions. This is hard to maintain. But European elites may be well-advised to heed Bickerton’s central message that the EU should see the symptoms of an underlying malaise that this ephemeral crisis has not removed.

Our special issue concurs with those who analyse Brexit as a challenge for the EU’s political, economic, and territorial integrity. Integrity can be preserved despite systemic dysfunctionality, such as too little fiscal and symbolic-political capacities to compensate losers of openness and integration. Brexit has, once more, shown that the EU as a polity is fragile and crisis-prone. But, as of now, it has also proven that it is able to redraw borders, exercise shared authority and mobilise second-order loyalty when challenged (Ferrera et al. Citation2021: 13–17). This is what polity maintenance means and it required, in the case of Brexit, active containment of a looming crisis to be achieved.

Membership crises that might be

Any preliminary diagnosis of a ‘crisis that wasn’t’ poses the methodological challenge of researching the counterfactual. There are many reasons why an event may not have happened, but they can be divided into broad categories. Did observers overestimate the crisis potential of Brexit for the EU and its member states since the UK was always an extreme case? Or was it the containment policy of the EU institutions that prevented it? If so, is it possible that the potential for a membership crisis persists and complacency on the part of the EU and national executives could facilitate more exits, or a different form of membership crisis? The contributions to this special issue discuss these three possibilities.

Was the crisis potential of Brexit overestimated?

Knowing what we know today, that the ‘domino effect’ predicted in the immediate aftermath of the Brexit challenge did not materialise, the dire evaluations and pessimistic forecasts made at the time may seem exaggerated. After all, the British relationship with the EU has always been exceptional in some respects. Britain has been notably labelled the EU’s ‘awkward partner’, thought to be geographically, institutionally and psychologically distant from the continent, characterised by persistent and outsized Euroscepticism (George Citation1990; see also Startin Citation2015; Davis Citation2017; Carl et al. Citation2019). A major component of the ‘awkward partner’ title was the ‘awkward party’, the Conservatives, which compared to mainstream centre-right parties in other European countries, projected more pervasive and intense Euroscepticism after Margaret Thatcher’s own conversion on the issue (Altiparmakis and Kyriazi Citation2023; Gamble Citation2012). With the party’s Eurosceptic tendency emboldened by the outside threat of UKIP and defections of voters to their fringe rival, the Conservatives opted to espouse much more radical Eurosceptic positions compared to their continental peers. This trajectory has been followed overtly neither by other centre-right parties nor even by radical-right populist parties. The latter never made the demand for exit through an in-out referendum the centrepiece of their strategy. But this was not a foregone conclusion. As Miró et al. (Citation2024) show, several of them demanded such a referendum right after the UK results came out.

Yet, there were good reasons for overestimating the significance of Brexit. First, Brexit may have got its wider appeal from a long-standing critique of the EU’s overreach, incarnated in the quest for ‘ever closer union’ that leaves hardly any national policy domain untouched (Richardson and Rittberger Citation2020). This view is shared by many citizens and their political representatives in the remaining EU-27. The moment in which Brexit occurred was one of extraordinary instability of the EU. Cameron’s pledge for a membership vote in January 2013 was part of a cluster of withdrawal referendums that the crisis-ridden 2010s brought to the fore in Europe and which sought to nullify common EU policies (Schimmelfennig Citation2019): the 2014 Swiss immigration initiative, the 2015 Greek referendum on the bailout terms, and the 2016 migrant quota referendum in Hungary. A Eurosceptic symbiosis appeared to be on the rise everywhere: in the souring public opinion of the member states, media discourse, civil society initiatives and party politics. The 2014 European Parliament elections were interpreted as a ‘Eurosceptic tsunami’, with a significantly increased presence of radical right and radical left parties entering the new assembly (Brack and Startin Citation2015).

The event of Brexit was a forceful articulation and symbol of these tendencies – a watershed moment from which the EU emerged weaker. Beyond the uncertainty created by this unprecedented event, the departure of a member state shattered the implicit assumption that the integration process would trace an almost teleological, linear progress towards ‘ever closer union’. Moreover, the impact of Brexit on the remaining member states was expected to be not only negative but also uneven. Ireland, Malta, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands were projected to suffer particularly from tariffs and non-tariff barriers vis-à-vis the UK (ECB Citation2020: 21). The various Brexit scenarios had a different impact on member states; for instance, the UK joining the European Economic Area would have had a more adverse effect on Malta and Luxembourg than a Free Trade Area and Customs Union with the UK while it was projected to be the other way round for Ireland (ECB Citation2020: 23). The inclusion of member states in supply chains with the UK varied a lot and hence regulatory non-alignment or delays from border controls were a serious concern for different sectors in different member states (ECB Citation2020: 31–34). Less tangible but arguably even more relevant differences concerned cooperation on internal and external security or the political thrust for closer European integration. These were all issues on which the UK was often a political ally of late joining member states in Northern and Eastern Europe and a vocal adversary to the ‘old’ EU core.

It seems to us that the crisis potential of Brexit was not overestimated. In particular, it was not a foregone conclusion that political unity would prevail, given the differential effects of Brexit on members.

What contained the Brexit crisis?

If the potential for a membership crisis was real, then how did the EU polity manage to prevent it from materialising? Any explanation has to grapple with the puzzle what made the rather diverse set of 27 member states unite behind a central negotiating strategy that gave a strong mandate to the Commission (Chopin and Lequesne Citation2021). To be sure, irrespective of the UK’s internal political struggles and imperfect strategy, exit was always going to be conducted in the context of an immensely asymmetric relationship between the two sides. The EU’s sheer market size combined with its experience in trade negotiations weakened the UK’s position, leaving it with little leverage to achieve the privileged access that it originally sought. Patel (Citation2018: 5–8) has analysed succinctly how the Brexit task force, called TF50Footnote5, used time-honoured techniques of international diplomacy in its deft negotiations with the UK. More broadly, the Brexit negotiations demonstrated that the EU’s supposedly porous, merely regulatory borders can be powerfully defended.

Another element was that unlike in prior crises, the EU has clear competence to handle matters of membership, with Article 50 of the TEU providing the necessary framework (Ganderson et al. Citation2024). Article 50 is a ‘well designed secession clause’ (Gatti Citation2017) in that it empowers the EU and ensures its unity when a member state decides to depart. The exclusive mandate for the negotiations assigned to the Commission left no space for side deals with other member states, while the two-year automatic deadline set the clock ticking and forced the UK government to ask twice for an extension, to its great embarrassment.

Beyond these structural conditions and stabilisers built into the institutions of the EU polity, another aspect of containment politics has to do with the negotiations proper – the way they were designed and conducted. Surely, this came in part as a reaction to the alienating behaviour of successive British governments: just like Prime Minister Cameron before, the administrations of Theresa May and Boris Johnson chose to emphasise red lines and threatened the EU with a hard break. This stance both stunned and united the EU-27. For example, it made influential and/or highly exposed member states to discover that they have at least compatible, if not identical, material interests regarding Brexit (Kyriazi et al. Citation2023). This may have silenced smaller member states, especially in Eastern Europe, even though they had expressed sympathy for the British aspiration soon after the referendum. Not a single member state broke rank.

This still leaves the question why the potential for substantive disagreements did not materialise as the negotiations drew to a close (Jensen and Kelstrup Citation2019). What stands out is the agency of the EU, coordinated across Commission, Council, and Parliament to stress that containment of the crisis potential was a policy. It showed unity, competence, and agility in representing the EU’s collective interests. The separation of a withdrawal agreement and a trade deal isolated some fundamentals, such as the rights of EU citizens in the UK and honouring the financial obligations that the UK incurred as a member state. They had to be settled before any negotiations on the vital economic relationship, which might have had a higher dividing potential, could begin. This curtailed package deals and served to drive home the point that an ex-member state would be treated like any other non-EU country for trade purposes.

The real sticking point of the negotiations became, however, the border with Northern Ireland. From the start, both the European Parliament and the Council stressed the EU ‘continuing to support and protect the achievements, benefits and commitments of the Peace Process’ (European Council Citation2017). By November 2016, the Irish government made the peace process the centre stage of its campaign, both domestically and in its frequent representations to the EU. The other member states appear to have been quite open to this prioritisation (Kyriazi et al. Citation2023; Laffan Citation2019).

A last factor on the EU side concerns the completely aligned communication strategy. It presented a united front to the other side; the task force, national heads of state and the European Parliament used even the same phrases from negotiation guidelines that the Council had approved. The EU’s display of power and competence would have challenged any British negotiation team, even if it had been more experienced and better prepared.

A different set of explanations as to what has contained the potential Brexit crisis relates to the extent to which right populist actors failed to exploit it. Even though in the immediate aftermath of the referendum several of these parties called for similar votes in their own countries, attrition was high: just one year later, their communication on social media was already much less concerned with the demand for a referendum and by the time the UK left, they had abandoned the EU exit bandwagon (Miró et al. Citation2024). The turnarounds of the French presidential hopeful Marine Le Pen and the Italian Lega leader, Matteo Salvini, were particularly noticeable. Le Pen visibly moderated her stance on European integration. In May 2022, her vote share brought a right populist leader closer than ever to the presidency in post-war France. Salvini’s party has already been part of four coalition governments, one under President Draghi, the embodiment of technocracy dedicated to EU-compliance. This is puzzling because the populist radical right supposedly ‘thrives’ on crises (Brubaker Citation2017), and so it would have an interest in cultivating and deepening a sense of membership crisis in the EU.

What, then, explains this muted response? On the one hand, unlike the euro area crisis and the refugee crisis, Brexit did not resonate with voters, and it had generally too little traction with domestic politics (Taggart and Szczerbiak Citation2018). On the other hand, where negotiations were noted, they were successful in generating a deterrence effect on bystanders, like Swiss voters (Malet and Walter Citation2023). The upheaval of British politics left little to envy or emulate. More generally, if the EU’s prior crises contributed to the ‘mainstreaming’ of Eurosceptic radical right parties, Brexit attests to their professionalisation. Those who do not follow the middle-way of ‘equivocal Euroscepticism’ (Heinisch et al. Citation2021) are likely to become marginalised and disappear. Usherwood (Citation2019) traces such a transformation in the case of UKIP. Mirroring their profound opportunism, radical right parties combine a hard Europhobic and a soft sceptical stance simultaneously, depending on the audience and the venue. In the European Parliament, their criticism of the EU is often more vocal and vociferous than at home, presumably because it is politically less costly and the only tie that holds the nationalist party family in the EU chamber reliably together.

What is the potential for further disintegration?

The outcome of the Brexit process left the UK’s political system in turmoil and the country, not the continent divided, to paraphrase Hobolt (Citation2016). While there is some reason for schadenfreude, subsequent events indicate that EU leaders showed not much triumph. If it is indeed the case that the successful containment of Brexit was the result of political agency, this also means that lingering threats may still be present requiring continuous efforts to keep the EU polity together.

To begin with, Brexit may still exercise a corrosive effect on the EU. For instance, very few scholars have asked how Brexit has affected the public’s perception of the EU’s integrity. In his contribution, Ganderson (Citation2023) does exactly that. Based on an original survey from mid-2021, he finds that even Remain voters, who witnessed the non-event that was Brexit, expect more departures from the EU. The departure of a member state has obviously weakened the perception that the union is established and stable.

Now that the inconceivable has happened, a member reversing the trend for an ever-expanding union, one may also consider what this means for separatist movements inside member states like Spain and for associated members of the EU’s various integration schemes with its neighbours (Malet and Walter Citation2023; Sanjaume-Calvet et al. Citation2023). After all, Brexit has unleashed disintegrative dynamics within its own borders, by providing the Scottish independence movement with a new lease to life. In the past, the EU institutions’ reaction to regionalist forces that have been testing the limits of the EU multi-level system making bids for ‘independence in Europe’ has been to defend the member states’ territorial integrity (Massetti Citation2021). Similarly, in the EU’s associated members, e.g. Switzerland, it was closely observed how flexible or principled the EU’s approach to a post-Brexit arrangement would be. For better or worse, it was principled or ‘ideologised’ (Schimmelfennig Citation2022) and a hard Brexit was the result.

Demand for Leave may also be encouraged by Brexit. This scenario is most relevant in member states where Eurosceptic parties form governments or have a chance to get into power and the case in several important member states: France, Italy, and the Netherlands. We have seen however, that in these countries, Euroscepticism has not followed the exit route, most notably in the case of the Rassemblement National in France and the Lega in Italy. To date, mainstream right parties in the continent abandoned the trajectory of the British Conservatives towards persistent and profound Euroscepticism, even though a small but noteworthy group of electorally strong centre-right parties seem to have hardened their Eurosceptic stance (Altiparmakis and Kyriazi Citation2023). Among these are the Hungarian Fidesz and the Polish Law and Justice governments, whose breeches of the rule of law has put them at loggerheads with the EU (Closa Citation2019). The conflict over the erosion of democratic quality and the rule of law reminds us that exit can come in other guises and that internal divergence from EU rules and norms can be potentially more harmful than a break. The EU has so far not found a way of containing this corrosive behaviour and could be criticised for its politics of complacency (Kelemen Citation2020), apparently hoping that the problem will go away with the next election.

Theoretical implications of a crisis contained

Our main explanation for a membership crisis that wasn’t is the politics of containment, both at the European and the member state level. Scholars have of course noted elements of this politics of containment, such as the EU’s carefully orchestrated negotiation strategy and the ostentatious unity of the remaining EU-27. This section spells out the implications of this ‘counter-attack’ (Schimmelfennig Citation2022) for theories of integration and the EU’s political system. The Rokkanian polity perspective has affinities with post-functionalism insofar it shares the emphasis on political processes in diverse member states as the unpredictable irritant of a functional integration logic. Both study the EU as a political system, more broadly in the case of Rokkan et al. (Citation1999) and Bartolini (Citation2005) and more focused in the case of Hooghe and Marks (Citation2009), in particular how they respond to pressures and change. Pressures may be externally inflicted or generated by the system’s own features. This makes both non-teleological theories of polity formation and integration: ever closer union is not a foregone conclusion; not only may there be stalemate, but also reversal.

The implications for post-functionalism that this special issue can draw out from the EU’s politics of containment are twofold. First, when confronted with another potential crisis, adaptations on the side of political decision-makers must be taken seriously, consistent with the non-teleological thrust of the EU. Second, the central notion of a transnational cleavage has possibly clouded our sight of the fact that many citizens do not strongly identify with either cosmopolitan or national-communitarian positions. These two implications give indeterminacy a role in a legally formalised, densely institutionalised polity that opens up space for political agency (Emmenegger Citation2021).

Post-functionalism, as formulated authoritatively by Hooghe and Marks (Citation2009, Citation2018), focuses on how politicised European integration has become, due to challenger movements that represent constituencies with traditional values and national allegiance. While originally on the fringe, Euroscepticism can muster wider appeal when crisis strikes repeatedly, and political decision-makers manage them through further integration and international cooperation that many voters come to see as the problem rather than the solution. By the time of the Brexit referendum, the EU had become extremely politicised, by which we mean it had become salient, polarising and the debate had expanded beyond conventional political venues (Hutter et al. Citation2016). EU crises dominated the news in every member state, polarised citizens within and across member states, and engaged many in street protests and heated exchanges on social media.

In particular, two difficult situations preceded the decision on Brexit. In July 2015, the talk of ‘Grexit’ accompanied a referendum on a third bailout programme for Greece foreshadowing the term ‘Brexit’ under very different circumstances. The seemingly never-ending Greek saga was soon overshadowed by the humanitarian migration crisis. It reached a dramatic stage in that same summer of 2015 when millions of refugees from Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq crossed borders to find shelter in the EU. But European leaders could not find a consensus amidst the political backlash in many member states, spurred on by the association of ‘the refugee problem’ with terrorist attacks. The UKIP leader, Nigel Farage, notoriously used the plight of refugees to insinuate that the EU’s migration regime brought the UK to ‘breaking point’ by allowing an influx of people from far-off countries.

Political decision-makers ignore such experiences at the peril of losing office. This holds even for the unelected office holders in the EU as there are now conceivable scenarios that could bring the EU edifice down. One such scenario would be that parties of the radical populist right enter government in France and Italy and would proceed to openly defy basic norms of the EU’s order, such as the supremacy of EU law, binding collective decisions in the Council and non-discrimination of EU citizens in the country of residence. The predictable stand-off with EU institutions could make government bond markets extremely nervous and the public in potential guarantor countries increasingly hostile to any support.Footnote6 This would combine to a perfect storm that the present, massively reinforced safety nets would be too weak to hold. Smaller, recent, and less engaged member states like Hungary and Poland already tested the boundaries and have in some respects exited within the EU (Szent-Ivanyi and Kugiel Citation2020).

So, executives have all incentives to draw lessons from the repeated experience that normal democratic contestation over certain EU policies, like free movement or refugee policies, can escalate into the politicisation of the polity itself. But which lessons should they draw exactly? The responses to Euroscepticism are thoroughly researched, for good reason. This concerned questions of whether the mainstream parties will absorb Eurosceptic challenger parties as Kriesi et al. (Citation2006, Citation2008) suggested, or whether the challenger parties will become a permanent feature of the party system as Hooghe and Marks (Citation2018) think. Less well-researched than these domestic responses on the supply-side of policy making is whether a more visible supranational level could play a constructive role and if so, in which ways. There is also a lot of research on Eurosceptic voters, notably their socio-economic and demographic characteristics. Less well-researched is the other side of the transnational cleavage, citizens who are generally supportive of EU membership, notably how they react to the Eurosceptic challenge and the politicisation of the EU polity as such.

Starting with the latter: the shorthand scholarly account of the term ‘transnational cleavages’ is often surprisingly close to the Eurosceptic portrayal. On the pro-integration side, it postulates a cosmopolitan elite that wins from everything that the EU offers, while most citizens are apparently on the anti-integration or sceptical side because they all lose.Footnote7 This is obviously a caricature. The majority of citizens tend to be on neither side: citizens experience openness as intensified competition for jobs and housing, which is upsetting, but also quite tangible benefits, such as the opportunity to travel cheaply and consuming a better range and quality of goods. In times of crisis, they may resent the obligations of EU membership but also observe protection they could not get without membership. Citizens in small open economies may feel differently from those in big member states, but not necessarily in predictable ways. Most anti-austerity protesters against the EU are possibly closer to the mainstream middle than to anti-immigration Eurosceptics, if we believe studies of ‘critical Europeans’ (Della Porta Citation2010; Moore and Trommer Citation2021).

The contributions to this special issue shed some light on the non-Eurosceptic range of the alleged cleavage. Our contributors discuss this side primarily to argue why the averted Brexit crisis does not allow complacency on the EU’s part. Euro-indifferent or supportive citizens have become less assured of the EU’s stability, which is a potentially corrosive, lasting effect of Brexit (Ganderson Citation2023). At the same time, Brexit made some consider for the first time why it is actually in their interest to be an EU citizen, as ‘Pulse of Europe’ demonstrations across the EU in 2016 suggest (DW Citation2016). Shaw (Citation2018: 146) also sees political mobilisation in favour of ‘transnational citizenship’ as an ironic outcome of Brexit. Hobolt and Rodon (Citation2020: 161), by contrast, have little hope that ‘Europeanisation’ of political mobilisation will help the EU. With every crisis, the situation of many citizens becomes more precarious in socio-economic terms. This could give rise to the same structural deprivations that prepared the ground for an anti-establishment Brexit vote.

The Covid-19 reforms indicate that it has dawned on EU leaders that more needs to be done to prevent such a scenario (Armingeon et al. Citation2022; Schelkle Citation2021). In this context, it is of interest that surveys show support for transnational solidarity among EU citizens, more than the standoff between executives in the 2010s led scholars to believe (Ferrera and Burelli Citation2019: 103–105). This is particularly noticeable in member states like Germany and Denmark. But specifics matter. There is less willingness, for instance, to pay higher taxes in order to support others in France and Italy than the traditional pro-integration stance of the countries’ leaders would suggest (Cicchi et al. Citation2020: 4). Solidaristic attitudes vary with the nature of crises: supposedly man-made disasters like refugee, unemployment and debt crises solicit less sympathy than natural, public health and climate calamities. Neighbourhood effects also play a role: rational fear of contagion and communitarian feelings that stretch across direct borders can explain why citizens are more ready to help countries around them than members further away (Cicchi et al. Citation2020: 5). This suggests that elected officials have support for solidaristic institution-building as well as leeway in how closely they represent domestically prevailing attitudes on the pro-integrationist side. That the national majority of voters take a more centrist stance than their governments in some policy debates allows the latter to compromise eventually.

The second issue follows from this insight that research points to a considerable degree of political indeterminacy worth fighting for on the demand side of policy making: how can the supply-side of decision-making respond to the emergence of a transnational divide? Schimmelfennig’s account (2023) makes a useful start by distinguishing policy failures, on the one hand, and polity attacks, on the other. Brexit, he argues, belongs to the latter category, and the EU went on the counterattack that, ultimately, bolstered the political development of the union. This principled, ideologized pushback was, however, economically costly for both sides. This fits a post-functionalist account that is expanded by a fuller theory on what this means for the supply side of policy making: defending the EU polity was not functional in the policy sense but achieved its goal of political unity.

The EU repeated this political, if not necessarily economic, success during the Covid-19 pandemic. In both instances, it averted a crisis in which its real or perceived mishandling could have become a source of Euroscepticism. Each time, it was the more structured challenge of national executives to which the EU’s political system has responded with policy measures that were mindful of the political sensitivity in different member states: Italy and Spain versus the Frugal Four in the case of the pandemic, Ireland above all in the Brexit negotiations. This prevented the more powerful or pivotal member states to set the agenda that suited primarily their own domestic conditions. In many ways, it was executive politics at its most effective.

The microphone diplomacy during the hot phase of the deliberations on economic crisis relief in 2020 indicates, however, that executive professionalism may not be enough to win hearts and minds of Euro-indifferent or merely sympathetic citizens. The heads of state of the five biggest members gave interviews in national newspapers of other European countries, typically in those they were in disagreement with (Schelkle Citation2021): Italy’s and Spain’s leaders in Germany, the Dutch leader in Italy, Germany in six countries simultaneously, and France’s leader to the Financial Times. In each case, they appealed to readers to put themselves into the shoes of others. This direct appeal to citizens in other countries had a follow up when Social Democratic leaders from Germany, Portugal and Spain urged French voters, presumably those on the left, to re-elect the right-of-centre candidate Macron as President (Jack Citation2022). None of this can be taken as evidence for a proper cleavage in the making, as it is not an organised, party-political expression of an underlying social division. But it is evidence for politicians in the EU to fight for support of the indeterminate middle in other member states, instead of concentrating their efforts only on the relatively extreme minorities on each side of the transnational cleavage at home.

Again, this should not be taken as a comforting trend for ever closer union. It will remain a balancing act for politicians to not lose sight of the middle while being mindful of the aggrieved extremes. Eurosceptic grievances that escalated in the case of Brexit are here to stay. EU membership cannot be fundamentally contested since it is not possible to go in and out of the EU with every election. Radical Right Parties all over the EU have for now conceded as much (Miró et al. Citation2024).

Moreover, Tilley and Hobolt (Citation2023) provide evidence for the erosion of consent to majoritarian decision-making among Remainers in post-Brexit Britain. This implies that a similar erosion process may affect losers’ consent on the part of Eurosceptic citizens in member states. Their belief in democracy is undermined because the EU is a constitutional feature of a political system, no longer up for periodical revision. However, it would be misleading to characterise this as an inherent democratic deficit of the EU. In this regard, NATO membership is not categorically different from EU membership. But it is true that the EU is now a superstructure reaching in virtually every policy domain of a member state. Post-functionalism tells us that the consent to this superstructure cannot be taken for granted. Policymakers seem to have stopped taking it for granted and when they do, they find a more responsive public than the notion of a pervasive constraining dissensus allows for.

Overview

The articles included in this special issue cover three broad themes. The first set is concerned with the EU’s defence against Brexit and its theoretical implications. Schimmelfennig’s (Citation2022) article examines the grand theories of European integration and their relevance for studying Brexit, showing that neither functionalism nor post-functionalism can fully account for the events witnessed. Instead, he proposes describing Brexit in terms of a ‘polity attack’ that caused significant political turbulence in the attacker, the UK’s political scene, and its eventual expulsion was accompanied with greater closure and cohesion of the remaining EU members. Moving from grand theory to a more empirical approach, the second paper by Kyriazi et al. (Citation2023) tracks the negotiation of Brexit and the unfolding events at the European and domestic level of five especially influential EU countries. It traces the empirics of the polity’s defence, addressing the puzzle of how the EU – despite the potential for internal division – managed to present a united front during the negotiations. It shows that critical factors in the negotiating process were the inclusion and prioritisation of member states’ concerns and hence their disciplined adherence to collective decisions, the elite-driven and structured nature of the negotiations and the low salience and polarisation of Brexit in most member states’ national political scenes that reduced pressure and scrutiny on the Commission’s negotiating team.

The second group of articles in this special issue address party positioning on Brexit and EU membership in three critical cases. Altiparmakis and Kyriazi (Citation2023) compare the UK Conservative Party to its European peers, scanning for traces of emergent Euroscepticism and potential parallels with the Conservatives. They demonstrate that the Conservatives were indeed exceptional in their opposition to the EU, but still, they find some traces of evolving Euroscepticism and radicalisation in a few of their comparable peers. Miró et al. (Citation2024) instead focus on radical right parties, analysing Twitter data to assess their activity on Brexit and the frames they use to discuss it. They show that few parties, such as the Italian Lega, were preoccupied with it at any length and in triumphant tones, urging for more exits elsewhere. Yet, most parties presented Brexit as a cautionary tale for the EU and all of them eventually lost interest as the negotiations became more complicated and unfavourable for the UK. In the last article under this theme, Sanjaume-Calvet et al. (Citation2023) return to the issue of framing but instead zoom in on a comparative study of the Catalan campaign of secession and the Brexit Leave campaign. While they discover that superficially both campaigns evoke the theme of sovereignty and focus on political and social issues to frame it, they still differ significantly as the Leave campaign focused on retaking control from a bloated EU, whereas the Catalan campaign’s goal was self-determination but in a context of EU membership.

Our final theme addresses crucial aspects of public opinion triggered by Brexit. Malet and Walter (Citation2023) examine whether there was a learning effect from Brexit on Swiss voters, who had to decide on key issues of their own relationship to the EU. Through a panel survey, they document that Swiss voters partially learnt from the failures of the UK’s negotiation with the EU, but the effects were generally rather marginal, confined to a small but nevertheless critical constituency of voters, who were ambivalent about their attitudes towards the EU and Switzerland’s cooperation treaties with it. While the electorate at large did not update its vote intentions in upcoming referenda, this small group of voters did, potentially shifting the eventual outcomes. Tilley and Hobolt (Citation2023) examine a different issue, the legitimacy and acceptance of electoral outcomes by the losers of such events. Juxtaposing the Brexit referendum and the UK’s 2019 general election, they discover that electoral processes which are perceived as unfair by their losers are likely to trigger intense emotional responses of anger and lead them to contest their legitimacy. They conclude that divisive electoral events like the Brexit referendum therefore may have a corrosive impact on the quality of democracy as polarisation and mistrust take root in the electorate. Finally, Ganderson (Citation2023) probes the impressions imprinted by Brexit on European publics and their assessment of the potential of future exits. He shows that Brexit had an asymmetrical effect on voters. Those enthused by Brexit are ever more likely to predict further exits from the EU and see their desires come true. A more mixed or ambivalent feeling has settled among those who perceived Brexit as a failed gambit by the UK, as they do not believe the botched precedent set by Britain will stop other countries from emulating it. This finding confirms the cautionary tale of other contributions: an EU crisis that wasn’t can still affect confidence in the EU’s integrity.

More generally, this special issue provides evidence that the EU has become a battle-hardened polity that cannot be adequately fathomed by integration theories. Brexit has shown that it can turn into strength what is often portrayed as its weakness when compared to ideal-typical states. Its flexible border regime allowed it to remain intact while Brexit split the Single Market of the UK into that of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. It used its dispersed authority to confront the British side with a supremely competent Task Force that was under conspicuous instruction by the Council. And the second-order loyalty meant that the protracted exit process had neither salience nor polarising effects in other member states, except the UK and Ireland. However, the heads of state in Hungary and, until 2023, Poland have taken their lesson from Brexit and prefer exit within the EU, notably from the supremacy of community law. The EU polity has yet to find an adequate answer to this erosion-type crisis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Waltraud Schelkle

Waltraud Schelkle has been Professor of European Public Policy at the European University Institute (EUI) since September 2022, and a Visiting Professor at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). She is a Principal Investigator of the ERC-funded project SOLID (Policy Crisis and Crisis Politics: Sovereignty, Solidarity and Identity in the EU post-2008). [[email protected]]

Anna Kyriazi

Anna Kyriazi is Postdoctoral Researcher at the Department of Social and Political Sciences of the University of Milan in the context of the SOLID project. She holds a PhD in Political and Social Sciences from the European University Institute. Her research interests include comparative ethnicity and nationalism, migration, and political communication, with a particular emphasis on Eastern and Southern Europe. [[email protected]]

Joseph Ganderson

Joseph Ganderson is a postdoctoral researcher at the European Institute, London School of Economics, where he works on the ERC-funded project SOLID (Policy Crisis and Crisis Politics: Sovereignty, Solidarity and Identity in the EU post-2008). He received his doctorate from the European University Institute, Fiesole, Italy. [[email protected]]

Argyrios Altiparmakis

Argyrios Altiparmakis is a Research Fellow at the European University Institute. His research focuses on party politics, political behaviour, and the recent European crises. He is currently working on the SOLID-ERC project. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 It is important to note the differential statuses of Great Britain and the United Kingdom with respect to the EU, since the Exit Treaty Protocol has split Northern Ireland off from the UK as far as the Single Market is concerned.

2 See Matthijs (Citation2017) for an account including Brexit as a major crisis, while Zeitlin et al. (Citation2019: 964) exclude it.

3 This question did not include Covid-19.

4 The wider edited volume gives a representative view of the fears, and very few hopes, for the EU that roughly thirty European scholars associated with Brexit (Martill and Staiger Citation2018). See also Richardson and Rittberger (Citation2020, 656–659) for an updated but less comprehensive overview.

5 The acronym derives from its full title of ‘Task Force for the Preparation and Conduct of the Negotiations with the United Kingdom under Article 50 TEU’. Patel (Citation2018) has an organigram.

6 An example for such a standoff was the letter that the incumbent and incoming ECB Presidents sent to then Prime Minister Berlusconi, asking for reforms in return for continuing bond market support of the Italian banking system.

7 Wolfgang Streeck has portrayed supporters and sceptics of EU integration in this polemical fashion for years, with distinctions like Marktvolk and Staatsvolk, most recently in Streeck (Citation2021).

References

- Altiparmakis, Argyrios, and Anna Kyriazi (2023). ‘A Leader without Followers: Tory Euroscepticism in a Comparative Perspective’, West European Politics. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2023.2170650

- Armingeon, Klaus, Caroline de la Porte, Elke Heins, and Stefano Sacchi (2022). ‘Voices from the Past: Economic and Political Vulnerabilities in the Making of Next Generation EU’, Comparative European Politics, 20:2, 144–65.

- Bartolini, Stefano (2005). Restructuring Europe: Centre Formation, System Building and Political Structuring between the Nation-State and the European Union. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

- Bickerton, Chris (2018). ‘The Brexit Iceberg’, in Benjamin Martill and Uta Staiger (eds.), Brexit and Beyond: Rethinking the Futures of Europe. London: UCL Press, 132–7.

- Bickerton, Chris J. (2012). European Integration: From Nation-States to Member States. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Brack, Nathalie, and Nicholas Startin (2015). ‘Introduction: Euroscepticism, from the Margins to the Mainstream’, International Political Science Review, 36:3, 239–49.

- Brubaker, Rogers (2017). ‘Why Populism?’, Theory and Society, 46:5, 357–85.

- Carl, Noah, James Dennison, and Geoffrey Evans (2019). ‘European but Not European Enough: An Explanation for Brexit’, European Union Politics, 20:2, 282–304.

- Chopin, Thierry, and Christian Lequesne (2021). ‘Disintegration Reversed: Brexit and the Cohesiveness of the EU27’, Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 29:3, 419–31.

- Cicchi, L. P., Genschel, A. Hemerijck, and M. Nasr (2020). EU Solidarity in Times of Covid-19. Florence: European University Institute.

- Cini, Michelle, and Amy Verdun (2018). ‘The Implications of Brexit for the Future of Europe: Rethinking the Futures of Europe’, 63–71.

- Collins, Stephen D. (2017). ‘Europe’s United Future after Brexit: Brexit Has Not Killed the European Union, Rather It Has Eliminated the Largest Obstacle to EU Consolidation’, Global Change, Peace & Security, 29:3, 311–6.

- Closa, Carlos (2019). ‘The Politics of Guarding the Treaties: Commission Scrutiny of Rule of Law Compliance’, Journal of European Public Policy, 26:5, 696–716.

- Davis, Richard (2017). ‘Euroscepticism and Opposition to British Entry into the EEC, 1955-75’, Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique, 22, XXII–2.

- De Vries, Catherine E. (2018). Euroscepticism and the Future of European Integration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Della Porta, Donatella (2010). ‘Reinventing Europe: Social Movement Activists as Critical Europeanists’, in Simon Teune (ed.), The Transnational Condition: Protest Dynamics in an Entangled Europe, vol. 4. New York: Berghahn Books, 113–28.

- DW (2016). ‘“Pulse of Europe” Rallies Converge across Germany and EU for United Europe’. https://www.dw.com/en/pulse-of-europe-rallies-converge-across-germany-and-eu-for-an-united-europe/a-38360750.

- ECB (2020). ‘A Review of Economic Analyses on the Potential Impact of Brexit’, ECB Working Papers. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3711524

- Emmenegger, Patrick (2021). ‘Agency in Historical Institutionalism: Coalitional Work in the Creation, Maintenance, and Change of Institutions’, Theory and Society, 50:4, 607–26.

- Euractiv (2023). ‘EU Leaders Approve Accession Talks with Ukraine, Moldova, Bypassing Hungary’, https://www.euractiv.com/section/europe-s-east/news/eu-leaders-greenlight-opening-accession-talks-with-ukraine-moldova/.

- European Council (2017). European Council (Art. 50) Guidelines for Brexit Negotiations. Brussels: European Council. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2017/04/29/euco-brexit-guidelines/.

- Ferrera, Maurizio, and Carlo Burelli (2019). ‘Cross-National Solidarity and Political Sustainability in the EU after the Crisis’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 57:1, 94–110.

- Ferrera, M., J. Miró, and S. Ronchi (2021). ‘Walking the Road Together? EU Polity Maintenance during the COVID-19 Crisis’, West European Politics, 44:5-6, 1329–52.

- Gallup-SOLID General Survey (2021). Online Survey.

- Gamble, Andrew (2012). ‘Better Off Out? Britain and Europe’, The Political Quarterly, 83:3, 468–77.

- Ganderson, Joseph (2023). ‘Exiting after Brexit: Public Perceptions of Future European Union Member State Departures’, West European Politics. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2022.2164135

- Ganderson, Joseph, Niccolò Donati, Maurizio Ferrera, Anna Kyriazi, and Zbigniew Truchlewski (2024). ‘A Very European Way out: Polity Maintenance and the Design of Article 50’, Government and Opposition. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2023.44

- Gatti, Mauro (2017). ‘Art. 50 TEU: A Well-Designed Secession Clause’, European Papers, 2:1, 159–81.

- George, Stephen (1990). An Awkward Partner: Britain in the European Community. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Glencross, Andrew (2018). ‘This Time It’s Different: Legitimacy and the Limits of Differentiation after Brexit’, The Political Quarterly, 89:3, 490–6.

- Heinisch, Reinhard, Duncan McDonnell, and Annika Werner (2021). ‘Equivocal Euroscepticism: How Populist Radical Right Parties Can Have Their EU Cake and Eat It’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 59:2, 189–205.

- Hix, Simon (2018). ‘Brexit: Where is the EU–UK Relationship Heading?’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 56:S1, 11–27.

- Hix, Simon, Sara Hagemann, and Doru Frantescu (2016). ‘Would Brexit Matter? The UK’s Voting Record in the Council and the European Parliament.’ VoteWatch Europe. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/66261/1/Hix_Brexit%20matter_2016.pdf.

- Hobolt, Sara B. (2016). ‘The Brexit Vote: A Divided Nation, a Divided Continent’, Journal of European Public Policy, 23:9, 1259–77.

- Hobolt, Sara B. (2018). ‘The Crisis of Legitimacy in European Institutions’, in Manuel Castells, Olivier Bouin, Joao Caraça, Gustavo Cardoso, John Thompson, and Michel Wieviorka (eds.), Europe’s Crises. Cambridge: Polity, 243−68.

- Hobolt, Sara B., and Toni Rodon (2020). ‘Domestic Contestation of the European Union’, Journal of European Public Policy, 27:2, 161–7.

- Hooghe, Liesbet, and Gary Marks (2009). ‘A Postfunctionalist Theory of European Integration: From Permissive Consensus to Constraining Dissensus’, British Journal of Political Science, 39:1, 1–23.

- Hooghe, Liesbet, and Gary Marks (2018). ‘Cleavage Theory Meets Europe’s Crises: Lipset, Rokkan, and the Transnational Cleavage’, Journal of European Public Policy, 25:1, 109–35.

- Hutter, Swen, Edgar Grande, and Hanspeter Kriesi (2016). Politicising Europe: Integration and Mass Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hutter, Swen, and Hanspeter Kriesi, eds. (2019). European Party Politics in Times of Crisis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Isiksel, Turkuler (2018). ‘Square Peg, Round Hole’, in Benjamin Martill and Uta Staiger (eds.), Brexit and Beyond: Rethinking the Futures of Europe. London: UCL Press, 239–50.

- Jack, Victor (2022). ‘German, Spanish and Portuguese Leaders Slam Marine Le Pen, “Hope” French Will Elect “Democratic” Candidate’, Politico, April 21. https://www.politico.eu/article/german-spanish-portuguese-leader-slam-marine-le-pen-france-election-democracy/.

- Jensen, Mads, and Jesper Kelstrup (2019). ‘House United, House Divided: Explaining the EU’s Unity in the Brexit Negotiations’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 57:S1, 28–39.

- Kelemen, R. Daniel (2020). ‘The European Union’s Authoritarian Equilibrium’, Journal of European Public Policy, 27:3, 481–99.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, Edgar Grande, Romain Lachat, Martin Dolezal, Simon Bornschier, and Timotheos Frey (2006). ‘Globalization and the Transformation of the National Political Space: Six European Countries Compared’, European Journal of Political Research, 45:6, 921–56.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, Edgar Grande, Romain Lachat, Martin Dolezal, Simon Bornschier, and Timotheos Frey (2008). West European Politics in the Age of Globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kyriazi, Anna, Argyrios Altiparmakis, Joseph Ganderson, and Joan Miró (2023). ‘Quiet Unity: Salience, Politicisation and Togetherness in the EU’s Brexit Negotiating Position’, West European Politics. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2023.2264717

- Laffan, Brigid (2019). ‘How the EU27 Came to Be’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 57:S1, 13–27.

- MacLeavy, Julie, and Martin Jones (2021). ‘Brexit as Britain in Decline and Its Crises (Revisited)’, The Political Quarterly, 92:3, 444–52.

- Malet, Giorgio, and Stefanie Walter (2023). ‘Have Your Cake and Eat It, Too? Switzerland and the Feasibility of Differentiated Integration after Brexit’, West European Politics. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2023.2192083

- Martill, Benjamin, and Uta Staiger (2018). Brexit and Beyond. London: UCL Press.

- Massetti, Emanuele (2021). ‘The European Union and the Challenge of “Independence in Europe”: Straddling between (Formal) Neutrality and (Actual) Support for Member-States’ Territorial Integrity’, Regional & Federal Studies, 32:3, 307–30.

- Matthijs, Matthias (2017). ‘Europe after Brexit: A Less Perfect Union’, Foreign Affairs, 96:1, 85–95.

- Miró, Joan, Argyrios Altiparmakis, and Chendy Wang (2024). ‘The Short-Lived Hope for Contagion: Brexit in Social Media Communication of the Populist Right’, West European Politics. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2024.2325785

- Moore, Madelaine, and Silke Trommer (2021). ‘Critical Europeans in an Age of Crisis: Irish and Portuguese Protesters’ EU Perceptions’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 59:2, 316–34.

- Oliver, Tim (2017). ‘Never Mind the Brexit? Britain, Europe, the World and Brexit’, International Politics, 54:4, 519–32.

- Patel, Oliver (2018). The EU and the Brexit Negotiations: Institutions, Strategies and Objectives. London: Brexit Insights, University College London. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/european-institute/sites/european-institute/files/eu_and_the_brexit_negotiations.pdf.

- Patomäki, Heikki (2017). ‘Will the EU Disintegrate? What Does the Likely Possibility of Disintegration Tell about the Future of the World?’, Globalizations, 14:1, 168–77.

- Politico (2023). ‘Macron: EU Should Consider ‘Multi-Speed Europe’ to Cope With Enlargement’, Politico, August 28, https://www.politico.eu/article/france-president-emmanuel-macron-multi-speed-europe-enlargement-ukraine-moldova-balkans/.

- Richardson, Jeremy, and Berthold Rittberger (2020). ‘Brexit: Simply an Omnishambles or a Major Policy Fiasco?’, Journal of European Public Policy, 27:5, 649–65.

- Rokkan, Stein, Peter Flora, Stein Kuhnle, and Derek W. Urwin (1999). State Formation, Nation-Building, and Mass Politics in Europe: The Theory of Stein Rokkan based on His Collected Works. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rosamond, Ben (2016). ‘Brexit and the Problem of European Disintegration’, Journal of Contemporary European Research, 12:4, 864–71.

- Sanjaume-Calvet, Marc, Daniel Cetrà, and Núria Franco-Guillén (2023). ‘Leaving Europe, Leaving Spain: Comparing Secessionism from and within the European Union’, West European Politics. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2023.2191104

- Scharpf, Fritz (1999). Governing in Europe: Effective and Democratic? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schelkle, Waltraud (2021). ‘Fiscal Integration in an Experimental Union: How Path-Breaking Was the EU’s Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic?’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 59:Suppl 1, 44–55.

- Schimmelfennig, Frank (2019). ‘Getting around No: How Governments React to Negative EU Referendums’, Journal of European Public Policy, 26:7, 1056–74.

- Schimmelfennig, Frank (2022). ‘The Brexit Puzzle: Polity Attack and External Rebordering’, West European Politics. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2022.2132448

- Schmidt, Vivien A. (2019). ‘Politicization in the EU: Between National Politics and EU Political Dynamics’, Journal of European Public Policy, 26:7, 1018–36.

- Shaw, J. (2018). ‘Citizenship and Free Movement in a Changing EU’, in B. Martill and U. Staiger (eds.), Brexit and Beyond. Rethinking the Futures of Europe. London: UCL Press, 156–64.

- Startin, Nicholas (2015). ‘Have we Reached a Tipping Point? The Mainstreaming of Euroscepticism in the UK’, International Political Science Review, 36:3, 311–23.

- Streeck, Wolfgang (2021). Zwischen Globalismus und Demokratie: Politische Ökonomie im ausgehenden Neoliberalismus. Franfurt: Suhrkamp.

- Szent-Ivanyi, Balazs, and Patryk Kugiel (2020). ‘The Challenge from Within: EU Development Cooperation and the Rise of Illiberalism in Hungary and Poland’, Journal of Contemporary European Research, 16:2, 120–38.

- Taggart, Paul, and Aleks Szczerbiak (2018). ‘Putting Brexit into Perspective: The Effect of the Eurozone and Migration Crises and Brexit on Euroscepticism in European States’, Journal of European Public Policy, 25:8, 1194–214.

- Tilley, James, and Sara B. Hobolt (2023). ‘Losers’ Consent and Emotions in the Aftermath of the Brexit Referendum’, West European Politics. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2023.2168945

- Usherwood, Simon (2019). ‘Shooting the Fox? UKIP’s Populism in the Post-Brexit Era’, West European Politics, 42:6, 1209–29.

- van Middelaar, L. (2019). Alarums & Excursions: Improvising Politics on the European Stage. Newcastle: Agenda Publishing.

- Wincott, Daniel, Gregory Davies, and Alan Wager (2021). ‘Crisis, What Crisis? Conceptualizing Crisis, UK Pluri-Constitutionalism and Brexit Politics’, Regional Studies, 55:9, 1528–37.

- Zeitlin, Jonathan, Francesco Nicoli, and Brigid Laffan (2019). ‘Introduction: The European Union beyond the Polycrisis? Integration and Politicization in an Age of Shifting Cleavages’, Journal of European Public Policy, 26:7, 963–76.