ABSTRACT

In this article, I analyze the use of historical counterfactuals in the Campaign of 1815 by Carl von Clausewitz (1780–1831). Such is the importance of counterfactuals in this work that its gist can be given in a series of 25 counterfactuals. I claim that a central role is played by evaluative counterfactuals. This specific form of counterfactuals is part of a didactic method that allows Clausewitz to teach young officers a critical method that prepares them for the challenge of decision-making in real warfare. I conclude with the enduring relevance of Clausewitz’s use of evaluative counterfactuals for contemporary military historiography.

Introduction

In his Campaign of 1815, Carl von Clausewitz (1780–1831) makes the following remark about Napoleon after his victory at Ligny against the Prussians on 16 June 1815: ‘If Bonaparte had followed with the main army, he would have been ready to fight at Wavre early on the 18th, and it is doubtful whether Blücher would have been in a position to accept a battle at that time and place, and even more doubtful that Wellington could have rushed over in time.’Footnote1 Clausewitz uses a historical counterfactual, which can be defined as a proposition of the form ‘If antecedent A had been the case, consequent C would have been the case.’ This counterfactual uses the perfect tense. Strictly speaking, a counterfactual can also be formulated in the imperfect tense: ‘If antecedent A were the case, consequent C would be the case.’Footnote2 In this article, I will concentrate on counterfactuals in the perfect tense, i.e., I will concentrate on historical counterfactuals.

Historical counterfactuals figure in the earliest military historiography and onward; Thucidides and Livy already wondered what their societies would have looked like if the Persians had defeated the Greeks or if Alexander the Great had turned his army toward Rome.Footnote3 Given this omnipresence, it would seem that historical counterfactuals have important functions, although debate about their use is by no means resolved, and already Leibniz subjected the concept to trenchant skepticism.Footnote4 Nevertheless, especially since the publication of David Lewis’s classical study Counterfactuals (1973), large strides have been made toward an increasingly sophisticated philosophical analysis of the functionality of various types of counterfactuals, including historical counterfactuals.Footnote5 These results can be used to obtain a deeper understanding of the specific functionality of specific types of historical counterfactuals in the works of individual historians, provided that due attention is paid to the historical and historiographical context of their works. In the present article, I discuss Clausewitz’s use of historical counterfactuals in his historical analysis of the Waterloo campaign; I place his preference for evaluative counterfactuals in the wider theoretical context provided by On War; and I conclude with the relevance of Clausewitz’s discussion of counterfactuals for contemporary military historiography.

But why Clausewitz and why the Waterloo campaign? Clausewitz’s work on On War, written during the last 15 years of his life, was preceded and accompanied by studies on military history. He took constant care to formulate a general theory of war that remained close to the diversity of historical experience. He was interested in attempts to integrate universality with particularity and was possibly influenced by Montesquieu, either directly, or through his mentor Gerhard von Scharnhorst (1755–1813).Footnote6 Clausewitz analyzed the campaigns of Frederick the Great and other early modern battles, but he was most interested in the more recent battles of the French Revolution and Napoleon, in many of which he had participated himself. His most interesting historical works were written after his appointment as director of the Berlin Kriegsakademie in 1818. In 1831, the revolutionary crisis saw him return to active duty in Posen, where he fell victim to the great cholera epidemic 1 year later. The last work in his hands was probably not the unfinished On War but his rather hastily finished history of the French campaigns in Italy and Switzerland of 1799.Footnote7

The importance of Clausewitz’s historical works for the development of his military theory has been widely appreciated, and of these historical works the Campaign of 1815 ranks especially high.Footnote8 It was written between 1827 and 1830 and he used its material to teach Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm of Prussia.Footnote9 While Clausewitz had still treated historical description and critical analysis separately in his account of the campaign of France of 1814, his account of the military events of 1815 achieves an exemplary and seamless integration of description and analysis in 57 short sections. Andreas Herberg-Rothe sees a direct connection between Clausewitz’s analysis of Waterloo and his famous mature appreciation of the relation between war and politics.Footnote10 Indeed, the Campaign of 1815 contains many concepts that are developed at a more abstract level in On War. This holds true for the ideas of friction and the culmination point of an attack; and, most significantly, the same point can also be made for historical counterfactuals.Footnote11

Moreover, the Battle of Waterloo itself made a career as the historical counterfactual par excellence from the moment when Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, famously observed that the outcome had been ‘the nearest run thing you ever saw in your life,’ until the fatal shots fired at Sarajevo on 28 June 1914 provided the world with another counterfactual paradigm.Footnote12 The counterfactual of a French victory at Waterloo was used in 1907 by G.M. Trevelyan and other authors as the starting point for a full-fledged ‘alternate’ history.Footnote13 Finally, the Waterloo campaign sees a remarkable combination of the same persons in multiple ‘counterfactual roles.’ Napoleon was not only the object of many counterfactuals but also made avid use of these propositions himself when, in the deadly torpor of St. Helena, he dictated Mémoires that were specially dedicated to the Waterloo campaign.Footnote14 Clausewitz participated in the campaign as chief of staff of the Prussian corps that pinned down Marshal Grouchy at Wavre.Footnote15 In addition, he wrote the counterfactuals in his own account often in a direct reaction against those of Napoleon, whose Mémoires in many ways set a polemic agenda for Clausewitz. Finally, Wellington was one of the main actors in the military drama, the recipient of some major criticism from Clausewitz, and also the writer of a reaction against this criticism, in which he scornfully rejects the latter’s frequent use of counterfactuals – immediately after having employed an extensive counterfactual himself.Footnote16

Description: the Waterloo campaign in 25 counterfactuals

Clausewitz starts his account of the extraordinary events that saw Napoleon escape from his exile on Elba and march across France, on 20 March 1815 – the day Napoleon triumphantly entered Paris and King Louis XVIII took refuge to Ghent. Napoleon started the ‘Hundred Days’ with energetic attempts at internal pacification and with preparations for the inevitable clash with the coalition of four great powers that had defeated him and forced him to abdication in the previous year. An Anglo-Dutch and a Prussian army would enter the southern part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands soon, and Austrian and Russian armies were on their way to other parts of the French frontier (the Seventh Coalition). Clausewitz concentrates on Napoleon’s military preparations and the subsequent Waterloo campaign, but he never loses sight of the precarious political context for the Emperor’s last military adventure. The Campaign of 1815 is positively bristling with historical counterfactuals. It is possible to summarize Clausewitz’s history of the campaign in the form of a series of counterfactuals, which is what I shall do here, with each counterfactual preceded by a number between square brackets.

[1] If Napoleon had imposed general conscription for all male French citizens between the ages of 20 and 60, he would have had a considerable force of over 2,000,000 soldiers. [2] Yet, this measure would only have worked if he had sufficient equipment and if the French had stood unified and enthusiastically behind him. His own Mémoires, as Clausewitz is keen to point out, show that he entertained grave doubts on each of these conditions; hence he rejected this option.Footnote17 Napoleon also considered the possibility of a defensive strategy that would have seen France invaded by the forces of the Coalition, but would have given him extra time to reinforce, make use of French fortifications, and possibly incite his citizens to a patriotic insurrection. [3] But a foreign invasion would have further compounded his already extremely perilous internal political situation. His Mémoires clearly testify that he felt this danger through and through; hence, it is not surprising that he rejected this option as well.Footnote18 So, Napoleon had no other option than an offensive operation with an army that numbered 129,000 men against his nearest enemies, the 99,000 soldiers of the Anglo-Dutch under Wellington and the 115,000 Prussians under Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher – in that sense he took the right decision. [4] Yet, his chances of success were exceedingly slim and even a resounding blow against the English and Prussians would still have left the possibility of defeat at the hands of the Austrians and the Russians. [5] But if Napoleon had managed to crush Wellington and Blücher, he would have been able to spare troops to counter the Austrians and the Russians while drawing on the vast capabilities of an energized and reunited France. The overall odds would still remain against him, but this would have given him a real chance to take on the Coalition.Footnote19 Given Napoleon’s urgent need for success against both the Anglo-Dutch and the Prussians, and given the well-known energetic way in which he waged his campaigns, Wellington and Blücher should have tried harder to combine their forces. [6] Given his need for a resounding victory, Napoleon would have attacked them anyway, even if he had been forced to confront them jointly. [7] But even if it had been obvious to both allied commanders that such a combination of forces was possible, it still would not have happened because Wellington was unduly preoccupied with the continued possession of Brussels. This fixation prompted him to deploy his troops in a wide area south of the city, screening its multiple approaches.Footnote20

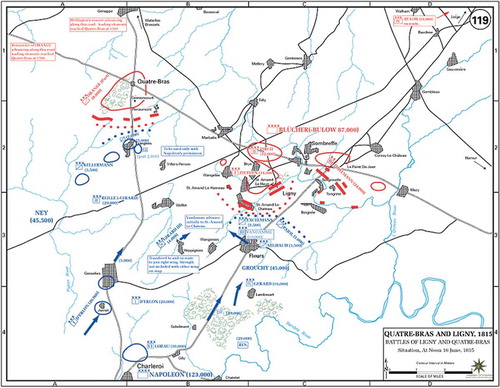

On the night of 14–15 June, the Coalition forces were surprised to learn that Napoleon was on the move and poised to strike in the direction of Charleroi, which was taken on the 15th. Napoleon had managed to insert himself between the Anglo-Dutch in the northwest, and the Prussians in the northeast. On the 16th, he sent Marshal Ney with 48,000 men to take and guard Quatre Bras against the Anglo-Dutch and decided to use his remaining 75,000 men against the Prussians, whom he attacked and beat, but did not destroy, at Ligny that same day (see Figure 1). [8] The Prussian General Bülow had remained too long in Liege, although he had received timely marching orders and would have been able to reach Ligny 12 hours earlier than he actually did, just in time to decide the battle in favor of the Prussians.Footnote21 [9] Similarly, Wellington had been able to send reinforcements that could have reached Ligny in time, again deciding the battle in favor of the Coalition, but he continued his passive defense of the approaches to Brussels.Footnote22 [10] On the French side, Napoleon maintained in his Mémoires that he had ordered Ney to send 10,000 men from Quatre Bras to Ligny; in that way the Prussians would have been surrounded, and Napoleon boasted that they would have been taken en flagrant délit.Footnote23 [11] Clausewitz does not agree: if Napoleon had really had this aim, he would have given clear and timely orders, but proof for such orders is conspicuously absent.Footnote24 [12] And even if Ney had appeared with 10,000 men in the open territory around Ligny, then Blücher would probably have been able to free part of his 80,000 men for countermeasures.Footnote25 [13] Clausewitz also notes that if Ney had possessed complete knowledge of the situation, he would have realized that he actually was able to drive away the Anglo-Dutch from Quatre Bras and then fall on the right wing of the Prussians at Ligny in full force, all on 16 June.Footnote26

After the Battle of Ligny, Blücher, with his forces battered but still intact, started a difficult retreat in the northern direction of Wavre with the aim of joining forces with Wellington. Napoleon maintains in his Mémoires that he was aware of this maneuver, but Clausewitz retorts that [14] if he had indeed guessed this movement, he would not have sent merely 35,000 men under Marshal Grouchy to go after the Prussians.Footnote27 [15] Actually, if Napoleon had followed the Prussians swiftly and with all his forces, and forced them to another battle, it is doubtful whether they would have been able to survive this second onslaught, and even more doubtful whether the Anglo-Dutch would have arrived in time to save their allies. In that way, Napoleon could have decided the entire campaign.Footnote28 [16] But even without such a major shift in Napoleon’s operations, it still remains true that if he really had guessed the direction of Blücher’s retreat, it would have been more natural (natürlicher) to post a strong corps on the left bank of the Dyle. [17] If a corps had been placed there, it would have been able to prevent the Prussians from joining the Anglo-Dutch at Waterloo while at the same time being available to help Napoleon in his decisive battle against the Anglo-Dutch.Footnote29 Napoleon would later maintain that it had been his plan all along for Grouchy to come to his aid against the Anglo-Dutch, and that [18] if Grouchy had followed his orders correctly, he would have arrived in time at the battlefield of Waterloo, thus deciding the battle in favor of the French.Footnote30 Clausewitz remarks that there is again no proof in the form of any clear order for this, and [19] if this had indeed been Napoleon’s intention, he should have taken care from the start to keep Grouchy between himself and the Prussians, not behind the Prussians.Footnote31 In the event, Grouchy first missed the Prussians and then ended up with a battle against their rear guard on 18 June at Wavre, while their regrouped and replenished main force was able to partake in the battle against Napoleon at Waterloo that same day.

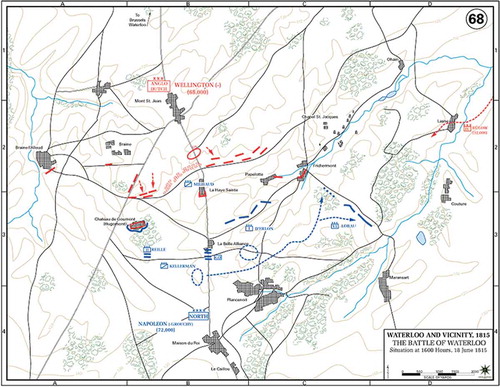

Meanwhile, Napoleon had used 17 June to push on in the direction of Wellington, and 18 June saw his army near Waterloo, pitched against the Anglo-Dutch, who later that day would be reinforced by the Prussians (see Figure 2). Napoleon opened his attack as late as 2:00 p.m. He could have attacked between 6:00 and 7:00 a.m. Why did he think that he could afford to wait? Because he did not believe that Wellington would be able to bring in any more additional troops, and also because he did not expect Blücher to come to Wellington’s aid that afternoon. Napoleon was right in the first assumption and his miscalculation in the second assumption did not matter very much; [20] if he had attacked earlier, then Blücher in his turn probably would have found ways to appear earlier as well, so that it would still have been hard for Napoleon to win at Waterloo. So neither assumption had much impact on the final outcome of the battle. Yet, Napoleon’s decision should be judged on the basis of his assumptions at that moment. His arguments for these assumptions were defective in both cases.Footnote32

The French concentrated their attack during the Battle of Waterloo on Wellington’s centre, which however they did not manage to break. [21] If they had rather concentrated on Wellington’s left wing, which was relatively weak and exposed by open terrain, the chances of success would have seemed higher.Footnote33 [22] But this would probably have resulted in an attack on the French rear by a sizable detachment of Prussian reinforcements, and this would actually have been the worst rather than the best option. [23] If Napoleon had included the timely arrival of the Prussians on the battlefield in his plans, as indeed he should have, then he should have tried an attack on the Anglo-Dutch right wing, even although this wing profited from depressions in the landscape.Footnote34 [24] In that case, the Anglo-Dutch would still have been supported by the Prussians, and an Anglo-Dutch rout would still have been unlikely; but perhaps the combined coalition forces might have suffered a similar blow as the Prussians had suffered 2 days earlier at Ligny; perhaps this setback would have caused hesitation and discord in the allied command; perhaps in this constellation Grouchy’s arrival a day later might have had an additional effect; and perhaps this would have marked the beginning of more sizable results for the French.Footnote35 [25] As it was, the fatal outcome of Napoleon’s late and uncoordinated attack against the Anglo-Dutch center during the Battle of Waterloo would probably not have been reversed even if Grouchy had arrived in time on the battlefield of Waterloo. Since the Prussians would have managed to send in troops as well, the cataclysm for the French would have been all the more comprehensive.Footnote36 Clausewitz notes with grim satisfaction that this time it was the turn of ‘the great magician’ himself to be taken en flagrant délit – not in a historical counterfactual, but for real.Footnote37

Analysis of the function of counterfactuals in the Campaign of 1815

In his critical analysis of the Battle of Ligny, Clausewitz excuses the modest performance of the Prussians and their commanders with the remark that action in war is like moving in a heavy element, so that even the most mediocre results demand uncommon capabilities. This remark about the debilitating effect of friction (which also appears in On War) is used to emphasize the function of criticism: it should try to assess the truth, not exercise the function of a judge.Footnote38 Peter Paret indeed used this observation to stress that Clausewitz ‘considered judgment in the sense of approval and disapproval to be (…) infinitely less significant than understanding what had occurred.’Footnote39 I do not agree with this verdict and I think that, in spite of this isolated remark, Clausewitz is very much interested in passing judgment on the choices and actions of the main actors. He constantly hands out praise and blame, implicitly or explicitly. Keywords that appear again and again in this context are ‘to forgive’ (verzeihen) and, especially, ‘to blame’ (tadeln). The Campaign of 1815 was composed by an officer who participated in the events himself and who evaluates the performance of his fellow officers. For instance, he notes that the Coalition was still in the dark about Napoleon’s whereabouts until 14 June and that it remained too long in a condition of ‘blameworthy indecision’ (tadelnswerther Schwebe). The Coalition had an – admittedly – vague sense of danger and yet it managed to be completely surprised by the lightning action of the Emperor.Footnote40 And when Clausewitz discusses Napoleon’s decision to continue the Battle of Waterloo in spite of the arrival of the Prussians on the battlefield, he adds that he cannot be blamed. Given his extremely vulnerable political internal and international situation, he had to persevere against all odds – it is not without some admiration that Clausewitz adds: ‘there are situations when the greatest prudence can only be sought in the greatest boldness, and Bonaparte’s situation was one of them.’Footnote41 Since the expression of approval and disapproval is so important for Clausewitz, it is not surprising that a large part of his counterfactuals can be understood in this light.Footnote42

When Clausewitz uses evaluative counterfactuals, his aim is frequently the assessment of responsibility, often in a direct reaction against Napoleon himself. In his Mémoires, the Emperor constantly tried to shift the blame for the indecisive nature of the Battle at Ligny to Ney [10] and the disaster at Waterloo to Grouchy [18] who, Napoleon maintains, failed to follow his orders. Clausewitz counters these counterfactual arguments in two different ways. Firstly, he notes that both are based on the assumption that Napoleon issued the orders in the first place; but Clausewitz denies that these orders were given, and without proof of their existence the ramifications of their nonexecution become vacuous. Moreover, in both cases, Clausewitz formulates his refutation in the form of a new counterfactual, so that [11] reacts against [10] and [19] reacts against [18]. From a morphological point of view, counterfactual [19] is especially interesting: if Napoleon had indeed intended to use Grouchy’s help at Waterloo before the arrival of the Prussians, then he should have taken care to keep Grouchy between himself and the Prussians. Usually both the antecedent and the consequent of a counterfactual take the form of a false event (i.e., an event that did not take place), but in this case only the antecedent is a (false) event. The consequent is not factual but deontological; ‘Napoleon should have.’

Clausewitz’s second mode of attack is to allow for a moment the truth of Napoleon’s counterfactuals, but to deny their relevance and hence their success in shifting the blame away from the Emperor to his subordinates. The effect of Clausewitz’s argument is again exculpation of Ney [12] and Grouchy [25], and hence inculpation of Napoleon. Even if his supposed orders had been obeyed, the result would still have been unsatisfactory, given the impact of his other, more fundamental errors. Both counterfactuals have again an intriguing morphology. Rather than the usual case of an antecedent and a consequent that are both false, in these cases we have an antecedent fact that is indeed false, but a consequent is not false but true: ‘even if Grouchy had arrived in good time on the battlefield (not a fact), Napoleon would still have lost at Waterloo (a fact).’ Nelson Goodman has called these partial counterfactuals semifactuals, which typically have the form ‘even if … then still’ rather than ‘if … then.’Footnote43

This second mode of attack on Napoleon’s attempts at self-justification points to the importance of the (un)availability of alternative options and alternative outcomes to an historical actor. These factors are highly relevant if we want to judge the person in question. Clausewitz seems to subscribe to the common assumption that the potential for praise and blame will be higher to the extent that an actor had more options that were able to produce more different outcomes, and vice versa. Since he adheres to this assumption about evaluative verdicts in general, it is not surprising that this assumption also informs his use of evaluative counterfactuals. Blame is often assigned in the form of a counterfactual that points to the availability of a different option that could have led to better outcomes. Wellington would have been able to send reinforcements to the Battle at Ligny and this could have decided the fight in favor of the Coalition, but he took the culpable decision to remain passive [9].Footnote44 On the other hand, Napoleon’s options after his return from Elba were very limited. The chances of success of an offensive military campaign against the assembling Seventh Coalition were very small, and even complete success against the Anglo-Dutch and the Prussians would still have left the gathering Russians and Austrians unaffected [4]; but a defensive campaign would have been fraught with (political) dangers as well [3]. The combination of [3] and [4] amounts to a semifactual: the alternative antecedent (a defensive versus an offensive campaign) is given the same likely consequent (a defeat for Napoleon) as the actual antecedent. This semifactual is used to excuse Napoleon’s actual choice.

But this is merely a simplified sketch of Clausewitz’s approach. He realizes very well that a fair counterfactual evaluation of his actors should not be based exclusively or even primarily on their objective options and the related outcomes, but rather on their own perceptions and evaluations. He tries to present an analysis of the aims and means of the main historical actors that is based on their own situational knowledge. Only with this information does he feel safe to pronounce evaluative judgments. And here again, historical counterfactuals are used to elucidate the options of the historical actors in question. At the start of the Hundred Days, Napoleon considered the option of a general conscription. This would have provided him with a very large army of some 2,000,000 recruits ([1]); but he rejected this option because of its expected negative outcome ([2]); political dissent stood in the way of raising this army and the required equipment was lacking. Napoleon ‘most definitely’ (auf das allerbestimteste) felt the problems related to this option; his analysis was correct, and hence he is not blamed for rejecting this option.Footnote45 Similarly, on 16 June, Marshal Ney had the means to both drive away the Anglo-Dutch from Quatre Bras and subsequently fall on the right wing of the Prussians at Ligny [13]; but because he did not and could not have the situational knowledge to see this as a viable option, he receives no blame.Footnote46

So far, we have seen that Clausewitz uses counterfactuals for the attribution of responsibility, often in a polemical context; for the assessment of available options and outcomes; and for a better understanding of the situational knowledge, the aims, and the means of his historical actors. All these points are related to the central function of administering praise and blame, while this activity itself is again frequently expressed in the form of counterfactuals – in the next section, we will see how this use of evaluative counterfactuals fits the wider didactic context of Clausewitz’s historical criticism as explained in On War.

Let us first see, however, how the case of Clausewitz relates to a modern account of the function of historical counterfactuals in historiography and what the differences may teach us. In a recent article, Daniel Nolan lists eight functions; he notes that counterfactuals are used because: (1) they can invigorate the historical imagination; (2) they help in bringing out disagreement; (3) they mitigate hindsight bias and increase the appreciation of historical contingency; (4) we gain inside understanding when we partake in the counterfactual worries and assessments of historical actors; (5) people are curious about counterfactual questions, which seems to make them legitimate topics of inquiry in their own right; (6) historians make causal judgments and (7) they give explanations, and the use of counterfactuals is closely related to these activities; and (8) counterfactuals can inform the value judgments of historians, including the assessment of responsibility.Footnote47 It is easy to find numerous examples of these points in the Campaign of 1815, but I will concentrate on two issues.

The most contentious issue is Nolan’s third point: the mitigation of hindsight bias and the increased appreciation of historical contingency. This might imply that counterfactuals can be used to make a point about the contingent versus deterministic character of history in general. This function has indeed been ascribed to counterfactuals by Niall Ferguson and other modern historians. Ferguson gives a brief history of historical determinism, presents contingent or ‘chaotic’ history as an alternative, and argues for the anti-determinist function of counterfactuals.Footnote48 But sometimes a historical consequent is the very contrary of contingent; it is overdetermined. A consequent is overdetermined when it has multiple antecedents that can each be regarded as a cause, while already a mere subset of these causes would have been enough to trigger the consequent. Martin Bunzl and Julian Reiss have argued that counterfactuals can perform an important function in solving problems of overdetermination. They can help us to make a distinction between antecedents that are sufficiently potent to trigger a consequent and antecedents that lack this capacity; in this way, historians use counterfactuals to assess ‘difference makers’: ‘If antecedent A had not been the case, consequent C would not have been the case.’Footnote49 This means that counterfactuals can be used not only to make a contingent point but also to make an ‘overdetermined’ or ‘determinist’ point.Footnote50 In Clausewitz we can indeed observe a perfect agnosticism about the contingent or determinist character of history as such.Footnote51 He sometimes observes that many options were open to the historical actors in question, and sometimes that there was an acute paucity of such options. Sometimes history is very open and sometimes it is very closed. We have seen that this position by no means impedes a fruitful use of counterfactuals. Actually, one of Clausewitz’s major reasons for using counterfactuals in the first place, is to understand or to assess how open or closed a given case actually was; and if he makes a point about the closed character of a case, he often uses a semifactual: ‘even if … then still.’

While Clausewitz thus give less prominence to the third point in Nolan’s list of counterfactual functions, the opposite holds for Nolan’s eighth point: the use of counterfactuals in making value judgments, including the assessment of responsibility. It is interesting to note that this function figures as the last item on Nolan’s list, and this is not coincidental. He writes: ‘One use of counterfactuals for historical purposes that has rarely been focused on in the recent literature is in the attribution of responsibility, and in the determination of the appropriateness of regret and pride, and to a lesser extent praise and blame.’Footnote52 Yet, in spite of this apparent modern rarity, we have seen how evaluative counterfactuals play an essential role in the Campaign of 1815. Moreover, while Nolan merely aims to present a list of different and only loosely connected counterfactual functions, Clausewitz’s account shows how different counterfactual functions can form an intricate and cohering pattern in which a central position is taken by evaluative judgments. Now that Nolan has helped to bring out this special interest, it may be useful to consider its conceptual and historical background in Clausewitz’s case.

Clausewitz’s use of counterfactuals for the attribution of praise and blame for the assessment of responsibility and for the inside information about historical actors in the Campaign of 1815 all point to a great interest in what Daniel Moran describes as ‘the minds of the men who commanded the armies that fought [this campaign].’Footnote53 In no mind is Clausewitz more interested than in Napoleon’s and he constantly reacts against Napoleon as actor and as writer of the Mémoires. Napoleon is the object of intense criticism – although Blücher and, especially, Wellington are not spared either.Footnote54 With his failure to pursue the Prussians after his victory at Ligny Napoleon squandered his best chance at a decisive victory (see [15]). This behavior is compared with two previous cases, which are formulated in similar counterfactual terms and contribute to the construction of a pattern. If Napoleon had chased the Austrians after the Battle of Dresden in 1813 and the Prussians after they had been caught at the Marne in 1814, he would have been able to follow up partial success with decisive victory. In his later years, he had become used to military opponents that took flight or became paralyzed after the first blow. He had formed a habit of underestimating and disdaining his adversaries that contributed to his final undoing in 1815.Footnote55

Moreover, Clausewitz uses Napoleon’s own Mémoires as ammunition for an uncanny picture of gradual mental decline with disastrous consequences. He uses Napoleon’s efforts to shift blame to Ney on 16 June (see [10]) and to Grouchy on 17 June (see [18]) to corroborate a pattern of vague and hesitant commands: ‘Given all this, it can already be said that even on the 16th Bonaparte was no longer equal to the task that fate had imposed upon him.’Footnote56 This line of argument is continued on the day of the Battle of Waterloo on 18 June. Napoleon loses many hours to deploy his army in a parade-like formation. Clausewitz notes that Napoleon’s Mémoires betray a puerile pleasure in receiving the accolades of his troops while riding in front of them. This dismissal of what may have been the last agreeable moment in Napoleon’s life may betray a certain meanness on the part of Clausewitz. More serious is his observation that the Emperor himself seems to have lost faith in the campaign, that with ‘the unnecessary assembling and parading of his army’ he hoped to induce Wellington’s army to a retreat so that, in a striking departure from his previous habits, he could evade battle altogether.Footnote57 All this confirms for Clausewitz the impression ‘that something had changed within him.’Footnote58 This mental unraveling contributed to his futile attack on the Anglo-Dutch center. Due to the unexpected arrival of the Prussians, Napoleon must have realized that his attack had little chance of success; his decision to start this attack was an act of ‘sheer desperation.’Footnote59 His decision to continue this attack while defeat was already staring him in his face lacked all rationality and no longer showed Napoleon as a great man, but ‘like someone who has broken an instrument and in his anger smashes the parts to pieces on the ground.’Footnote60 Although Clausewitz’s evaluative counterfactuals in the Campaign of 1815 are used to establish a pattern of personal hubris and failing leadership, this amounts to more than just a case of old-fashioned nineteenth-century ‘Great Man’ historiography; but in order to appreciate that, we need to turn to Clausewitz’s theoretical masterwork.Footnote61

Context: on war

In On War Clausewitz explains that the theory of war concerns itself with the study of ends and means.Footnote62 Various factors conspire to make this study a highly problematic venture: war is driven by complex psychological forces; these forces tend to interact; and in general all military action has to proceed in a state of twilight due to a constant lack of information.Footnote63 Nevertheless it is possible to formulate a large number of evident propositions, for instance, that defense is the stronger form of warfare with a negative purpose while attack is the weaker form with a positive purpose; and that victory not only implies the conquest of the battle field but also the physical and psychological destruction of the opponent.Footnote64 History is an important tool in the formulation of these rules, if only because it provides certain limiting conditions: ‘But that is inevitable, since theoretical results must have been derived from military history or at least checked against it.’Footnote65 Neither here nor elsewhere does Clausewitz provide a precise methodological procedure for the contribution of history to the formulation of theoretical rules. This is probably because he sees theory very much in the light of its practical function as an instructive didactic tool, and he is extremely skeptical about the instructive use of theory in the form of a fixed set of prescriptive rules.

A military theory should demonstrate its practical use by offering young officers reflection rather than trivial rules about the extremely complicated topic of warfare.Footnote66 Theory should invite them to an analytic examination that leads to an understanding of the objects under investigation. There is only one way to instill this familiarity in pupils even before they engage in direct operational activities, and that is through a close study of military history.Footnote67 History allows the student to relive the decisions of great generals in what Jon Tetsuro Sumida has called ‘a form of psychological reenactment.’Footnote68 Given his didactic aims, it is not surprising that Clausewitz prefers a detailed historical account of a single campaign to more general surveys, and this in turn explains his predilection for recent and contemporary history.Footnote69 In a letter of 1829 to Karl von der Gröben, Clausewitz explained that the instructive aim of his historical writings was the reason why he did not publish his historical works: ‘I am never afraid to ask the “why” of the “why,” since I do not aim to write something that is agreeable, but only to seek for myself and others unquestionable truth and instruction.’Footnote70 History also had taught Clausewitz himself an important lesson. The crushing defeat of Prussia at the Battle of Jena in 1806 showed to him the danger of the mindless application of military procedures that had functioned well enough in the age of Frederick the Great. The antidote against such petrified ‘methodism’ is to develop the critical capabilities (Kritik) of young officers.

In criticism, history is not used for theory, but theory is used for history – not so much because theoretical content is brought to bear on history because criticism is a theoretical method applied to history.Footnote71 Historical criticism has three functions: it helps to clarify dubious facts, it contributes to establishing causal relations, and it inspects (prüfen) means in relation to ends. There is a clear relation between these functions. It is only thanks to causal criticism that we are able to isolate the topics that are worthy of evaluative criticism.Footnote72 But the ultimate aim is evaluative criticism, one that contains ‘praise and blame’ (Lob und Tadel) about means and ends.Footnote73 It is this evaluative function that enables criticism to be instructive (belehrend).Footnote74 Given his aim of educating young officers to become future leaders, it is not strange that Clausewitz concentrates on the actions and decisions of great generals. And since he finds it important to judge individuals, he formulates a criterion of fairness that guides this judgment. The military critic should endeavor to place himself in the shoes of his historical subject, and only praise or blame him on account of what he knew or could have known.Footnote75 The critic should try to reproduce the mental activity of his subjects and criticism should use the same practical language as the subjects that it studies in the midst of their choices and actions. Only then will criticism exercise its instructive function and only then will this theoretical tool be adequately applied.

Moreover, if criticism is to exercise its function properly, it needs historical counterfactuals. Since criticism should have the form of an evaluative judgment about the aims and means of generals, it should not only inspect the aims that they really formulated and the means that they really used but also take into consideration the aims that they could have formulated and the means that they could have used: ‘Critical analysis is not just an evaluation of the ends actually employed, but of all possible means – which have first to be formulated, that is, invented. One can after all, not condemn a method without being able to suggest a better alternative.’Footnote76 A telling example is the analysis of Napoleon’s performance after defeating the Austrian Archduke Charles on the Tagliamento in 1797. Clausewitz starts with the limited perspective of a local military success in Italy and then zooms out, to evaluate Napoleon’s actions and decisions in an ever-wider perspective. He includes the strategic level of coordinated action with other French armies and the level of ultimate political and diplomatic success against the Austrians. Each level in this subtle hierarchy of possible means and ends is subjected to rigorous counterfactual analysis.Footnote77

Clausewitz’s interest in great men and his efforts at inside knowledge are indeed typical of nineteenth-century historicism. But we have now seen that it is possible to give a more specific context for his use of counterfactuals in the Campaign of 1815. Counterfactuals form the vital element of a critical investigation, in analytic sections that often carry the explicit title of ‘Criticism’ or ‘Reflection’ (Betrachtung) and are interspersed among more descriptive sections. In this way, the point made in On War about the interrelated character of factual, causal, and evaluative criticism is brought into vivid practice in the Campaign of 1815. Moreover, in On War, the author explains how his counterfactual criticism is an instrument in the pursuit of instructive ends; and these ends are indeed vigorously pursued in the Campaign of 1815. Facts should be used to draw ‘clear and instructive conclusions’ (ein klares und lehrreiches Resultat).Footnote78 Clausewitz had good reasons to use this work for teaching the Crown Prince.

Context: military history in general

Although the eight functions ascribed by Nolan (Section 3) to counterfactuals were formulated with the aims of contemporary historians in mind, we have seen that most of these functions can be clearly distinguished in Clausewitz’s Campaign of 1815. The instructive function of this work (as further explained in On War) explains why a central part is played by evaluative historical counterfactuals that assign praise and blame to individual military leaders. Other kinds of historical counterfactuals are often used as means toward this end. In that sense, the Campaign of 1815 serves as a rewarding case for a study of the intricate patterns formed by the interrelated functions of different types of counterfactuals. But why, actually, was it so easy to present the main stages of this account in counterfactual form? Surely this must be related to the military theme of the work. One of the first truly systematic uses of counterfactuals was indeed made by an immediate predecessor of Clausewitz, the Welsh officer and military writer Henry Lloyd (1718–1783).Footnote79 He did not just write a factual history of the campaigns of Frederick the Great, but a critical analysis that may have been a source of methodological inspiration for Clausewitz. Catherine Gallagher notes that Lloyd’s critical project entailed three levels of narrative: ‘what happened, what might have happened, and what should have happened. It is in the last of these levels that Lloyd comes into the full exercise of his critical powers, and we should note that when the “ought” narrative begins, unmarked transitions take us into the realm of the counterfactuals.’Footnote80 This perceived aptitude of military history for counterfactual treatment has remained in view ever since. In 1999 and 2001, Robert Cowley edited two popular collections of counterfactual history: What If? The first volume consists exclusively of military history (reflecting its original publication in MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History). The second volume no longer focuses on military topics, but in the introduction, the editor repeats a point that he already made in the first volume: ‘Armed confrontation provides counterfactual history with its most natural arena.’Footnote81

Various reasons have been given for this aptitude of military history for the formulation of historical counterfactuals. Bunzl points to the importance of aims. Counterfactuals explicitly or implicitly ascribe aims to historical actors, and counterfactuals can be used to test the rationality of the choices that were supposed to realize these aims. The advantage of military aims is that they tend to be clearer than other aims; military aims can often be expressed unambiguously in terms of winning. If the aims are so clear, then it becomes easier to construct counterfactuals that study their (lack of) realization. But Bunzl appreciates that this is by no means an absolute criterion; often military aims are muddled while nonmilitary aims can be surprisingly clear.Footnote82 A more important reason is suggested by Crowley in the introduction to his first volume of What If?: ‘What ifs can define true turning points. They can show that small accidents or split-second decisions are as likely to have major repercussions as larges ones.’Footnote83 Military history seems especially prone to dramatic turning points, hence its special counterfactual potential.Footnote84

But what exactly is a ‘turning point’? We have seen that a counterfactual consists of antecedents and consequents. Turning points are antecedents that have dramatic consequents. This means that the construction of a counterfactual turning point should be understood in terms of what Noel Hendrickson calls ‘the problem of selecting antecedent scenarios.’Footnote85 He starts his ‘plausibility theory’ with the general observation that good counterfactual antecedent scenarios should be constructed with a minimum of change in the counterfactual history that is supposed to produce the antecedent in question. This well-known ‘minimal rewrite rule’ is defined by Hendrickson as ‘the shortest path to the antecedent that involves no highly improbable individual events (assessed in terms of the immediately prior events).’Footnote86 This is refined to three sub-criteria. The first sub-criterion is the amount of prior history that is perfectly preserved. This indicates how far back in time events have to be altered in order to produce the posited counterfactual antecedent in question.Footnote87 The second sub-criterion pertains to the probability of the initial deviation; it should be realistic and plausible. The third sub-criterion concerns unity: ‘An antecedent scenario is unified to the extent to which the history of the antecedent traces back to fewer starting points.’Footnote88 Moreover, it should be observed that Hendrickson, like other philosophers of historical counterfactuality, is interested in a theory that yields ‘intuitively correct results,’ i.e., a theory that remains close to the intuitions of historians.Footnote89

Using Hendrickson’s criteria, it is easy to see how military history can offer a myriad of counterfactual turning points that are the immediate and dramatic results of small contingencies or decisions. This falls under the first criterion (perfectly preserved prior history). It is also easy to see how in a military campaign, let alone in one battle, a single contingency or decision can have dramatic results. This falls under the third criterion (unity). The second criterion on the other hand, probability, has no privileged status in military history. There is no a priori reason why counterfactuals should be more probable in this branch of history than in other fields of history. If the three criteria for a good counterfactual are indeed close to the common notions of previous and contemporary historians, and if the first and third criteria form part and parcel of military history in particular, then one would expect these criteria to remain predominantly implicit in works of military history, while the more problematic second criterion of probability receives more explicit attention. This is indeed the case in Clausewitz’s Campaign of 1815. Most of his counterfactuals fulfill Hendrickson’s criteria of perfectly preserved prior history and unity, but the application of these criteria remains implicit. On the other hand, much of Clausewitz’s critical method in the Campaign of 1815 is geared toward an investigation of the (im)probability of its many counterfactuals.

This evaluation of the counterfactual potential of military history in general and the special case of Clausewitz’s Campaign of 1815 points to a surprisingly modern relevance of the seemingly antiquated field of military history at the operational level and its preoccupation with the motives and actions of great generals. The field seems indeed to enjoy a modest but no less surprising renaissance in the judgment of academic scholars. Robert Citino notes about operational military history: ‘Once dominated by personalist modes of analysis that consisted almost exclusively of blaming General X for zigging when he should have zagged, or turning left when he should have turned right, it is now much more likely to emphasize systematic factors: the uncertainty of the battlefield (often metaphorically expressed, per Carl (…) von Clausewitz, as the “fog of war”), the ever-present problems of information-gathering and -sharing, and the inherently asymmetric nature of war. As historians in all fields seem increasingly willing to recognize the role of contingency, chance, and even “chaos” in historical development, operational military historians find themselves in the unusual position of being well ahead of the scholarly curve: they have been talking about all of these things for years.’Footnote90 Clausewitz himself made significant contributions to all these ‘systematic factors’ and this explains much of his continuing relevance – although the contemporary enthusiasm generated by these topics has led to confusions that cannot be ascribed to himself. Allan Beyerchen wrote a classic article on the role of chaos and nonlinear processes and their role as impediments to the formulation of a theory of war in On War, but his thesis has met with serious and pertinent criticism.Footnote91 Terence Holmes puts the role of chaos into perspective by arguing that Clausewitz, although he appreciates the complicating influence of friction and interaction, still maintains that a military genius will be able to predict the reactions of his opponents and include these in his plans – so chaos does not make planning impossible.Footnote92 In addition, Paul Roth and Thomas Ryckman answer Beyerchen with the more fundamental observation that chaos theory consists of value terms and concepts that ‘have a specifically precise meaning only within the confines of mathematical theory,’ which means that ‘the promised benefits of chaos theory vis-à-vis history are either fantastic or, at best, an extremely loose heuristic.’Footnote93 Moreover, we have already noted how some historians tend to compound these problems, by using notions of chaos and contingency in conjunction with counterfactuals for anti-determinist claims about the nature of history. On this account as well, Clausewitz shows an enduring relevance. He does not use counterfactuals to make claims about the open or closed character of history, but rather puts them to instructive use as part of a critical method that evaluates the possibilities of means and ends in individual cases, even if this means the use of Citino’s ‘personalist modes of analysis’ that consist of ‘blaming General X for zigging when he should have zagged.’Footnote94

Map 1. The Battles of Ligny and Quatre Bras, 16 June 1815.Footnote95

Map 2. The Battle of Waterloo, 18 June 1815.Footnote96

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Paul Schuurman

Paul Schuurman works on war in the history of ideas and he has published on the grand strategy of the Dutch Republic; François Fénelon (1651–1715) on war and luxury; Montesquieu on process explanations for the rise and fall of the Roman Empire; Clausewitz on real war and on limited war. Paul Schuurman also has published on senventeenthcentury logic, epistemology and metaphysics. He has an MA degree in History, Bussiness Administration and Philosophy, and obtained his doctorate at Keele University, UK, with dissertation on John Locke, and currently works as lecturer at the Faculty of Philosophy of Erasmus University Rotterdam.

Notes

1 Carl von Clausewitz, ‘Feldzug von 1815. Strategische Uebersicht des Feldzugs von 1815 in Clausewitz, Schriften – Aufsätze – Studien – Briefe’, in Werner Hahlweg (ed.), Dokumente aus dem Clausewitz-, Scharnhorst- und Gneisenau- Nachlaß sowie aus öffentlichen und privaten Sammlungen, vol. II. 2 (=Feldzug), § 51, 1079. English translation: On Waterloo. Clausewitz, Wellington and the Campaign of 1815, transl. and ed. Christopher Bassford, Daniel Moran and Gregory W. Pedlow (s. l. Clausewitz.com, 2010) (=Campaign) p. 186. Another translation is Carl von Clausewitz, On Wellington, transl. and ed. Peter Hofschröer (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010). The translation of quotations from other works besides the Feldzug von 1815 is mine, unless stated otherwise.

2 Cf. David Lewis, Counterfactuals (Oxford: Blackwell 1973), 1–4; Peter Menzies, ‘Counterfactual Theories of Causation,’ The Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy (Fall 2009 Edition), <http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/causation-counterfactual/>.

3 See Gavriel Rosenfield, ‘Why Do We Ask “What if?” Reflections on the Function of Alternate History’, History and Theory 41 (2002), 91; Simon T. Kaye, ‘Challenging Certainty: The Utility and History of Counterfactualism’, History and Theory 49 (2010), 45–46; Martin Bunzl, ‘Counterfactual History: A User’s Guide’, American Historical Review 109 (2004), 846.

4 Rosenfield, ‘Why Do We Ask “What if?”’, 90–103; Kaye, ‘Challenging Certainty,’ 42; Richard J. Evans, Altered Pasts. Counterfactuals in History (Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press 2013), 125.

5 See, among others, Noel Hendrickson, ‘Counterfactual Reasoning and the Problem of Selecting Antecedent Scenarios,’ Synthese 185 (2012), 365–386 and Menzies, ‘Counterfactual Theories of Causation,’ passim.

6 Azar Gat, A History of Military Thought from the Enlightenment to the Cold War (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2001), 169, 191, 195.

7 Eberhard Kessel, ‘Zur Genesis der modernen Kriegslehre. Die Entstehungsgeschichte von Clausewitz’ Buch “Vom Kriege”’, Wehrwissenschaftliche Rundschau 3 (1953), 418–423; Peter Paret, Clausewitz and the State. The Man, His Theories and His Times (Princeton: Princeton University Press 2007), 328–330; Werner Hahlweg, ‘Vorbemerkung’ to Carl von Clausewitz, 'Feldzug von 1815. Strategische Uebersicht des Feldzugs von 1815 in Clausewitz, Schriften – Aufsätze – Studien – Briefe', in Werner Hahlweg (ed.), Dokumente aus dem Clausewitz-, Scharnhorst- und Gneisenau- Nachlaß sowie aus öffentlichen und privaten Sammlungen (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht 1990), vol. II. 2, 936–937.

8 Daniel Moran, ‘Clausewitz on Waterloo: Napoleon at Bay’, in Christopher Bassford, Daniel Moran and Gregory W. Pedlow (transl. and eds.), On Waterloo. Clausewitz, Wellington and the Campaign of 1815 (s. l. Clausewitz.com 2010), 241; Paret, Clausewitz and the State, 329; Jon Tetsuro Sumida, Decoding Clausewitz. A New Approach to On War (Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas 2008), 136; Bruno Colson, ‘Clausewitz on Waterloo’, War in History 19 (2012), 400; and, especially, Andreas Herberg-Rothe, Clausewitz’s Puzzle. The Political Theory of War (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2007), 32–38 and 79–85.

9 Christopher Bassford, ‘Introduction’ to Campaign, 6; Moran, ‘Clausewitz on Waterloo’ in Campaign, 237; Herberg-Rothe, Clausewitz’s Puzzle, 37 dates the writing of the Campaign of 1815 to 1827–1828.

10 Herberg-Rothe, Clausewitz’s Puzzle, 83–84.

11 Friction: Feldzug § 33, 1013–1014; culmination: Feldzug § 33, 1012.

12 Quoted in Moran, ‘Clausewitz on Waterloo’ in Campaign, 253.

13 George Macaullay Trevelyan, ‘If Napoleon Had Won the Battle of Waterloo,’ in Clio, a Muse, and Other Essays Literary and Pedestrian (London: Longmans, Green 1913), 184–200. See also Kaye, ‘Challenging Certainty,’ 48.

14 Napoléon, Mémoires pour servir À l’histoire de France en 1815, avec le plan de La bataille de Mont-Saint-Jean (Paris: Barrois 1820); see also Evans, Altered Pasts, 3; Moran, ‘Clausewitz on Waterloo’ in Campaign, 253.

15 See Donald Stoker, Clausewitz. His Life and Work (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2014), 223–253.

16 Wellington, ‘Memorandum on the Battle of Waterloo’, in Christopher Bassford, Daniel Moran and Gregory W. Pedlow (transl. and eds.) On Waterloo. Clausewitz, Wellington and the Campaign of 1815 (s. l. Clausewitz.com 2010), 219–35.

17 Feldzug § 5, 953; Napoléon, Mémoires, 51–65.

18 Feldzug § 7, 956–958; Napoléon, Mémoires, 59–60.

19 Feldzug § 14, 971–972.

20 Feldzug § 15, 974.

21 Feldzug § 20, 980.

22 Feldzug § 21, 980–981.

23 Napoléon, Mémoires, 93–94, 100; Feldzug § 30, 996.

24 Feldzug § 31, 997–1000 and idem § 36, 1023

25 Feldzug § 31, 1001.

26 Feldzug § 36, 1023–1024.

27 Napoléon, Mémoires, 115–117; Feldzug § 37, 1025–1026.

28 Feldzug § 51, 1079–1081.

29 Feldzug § 37, 1026.

30 Napoléon, Mémoires, 107–115, 142–158, 197.

31 Feldzug § 48, 1053–1059.

32 Ibid., 1052.

33 Ibid., 1066.

34 Ibid., 1067.

35 Ibid.

36 Feldzug § 50, 1075.

37 Ibid., 1087.

38 Feldzug § 33, 1014; cf. Vom Kriege I. 7, 263.

39 Paret, Clausewitz and the State, 349, 354.

40 Feldzug § 18, 978.

41 Feldzug §48, 1070/Campaign, 177.

42 See the counterfactuals [2], [3], [6], [7], [8], [11], [12], [14], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [23] [24], and [25].

43 Nelson Goodman, Fact, Fiction and Forecast (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press 1983), 3–31. Other semifactuals employed by Clausewitz include [4], [6], [7] and [25].

44 See also counterfactual [8].

45 Feldzug § 5, 953/Campaign, 63.

46 See also Paret, Clausewitz and the State, 332; Moran, ‘Clausewitz on Waterloo’, 240.

47 Daniel Nolan, ‘Why Historians (and everyone else) Should Care About Counterfactuals’, Philosophical Studies 163 (2013), 333–334.

48 Niall Ferguson, ‘Introduction’ to Virtual History. Alternatives and Counterfactuals (s. l.: Basic Books 1997), 20–88; see also Kaye ‘Challenging Certainty’, 38–43.

49 Cf. Bunzl, ‘Counterfactual History’, 857; Julian Reis, ‘Counterfactuals, Thought Experiments, and Singular Causal Analysis in History,’ Philososophy of Science 76 (2009), 722.

50 See Kaye, ‘Challenging Certainty’, 50; Evens, Altered Pasts, 36–37, 61.

51 See also Moran, ‘Clausewitz on Waterloo’, 246.

52 Nolan, ‘Why Historians Should Care’, 331.

53 Moran, ‘Clausewitz on Waterloo’, 240.

54 Cf Hahlweg, ‘Vorbemerkung’ to Feldzug, 939.

55 Feldzug § 51, 1080.

56 Feldzug § 34, 1018/Campaign, 127.

57 Feldzug § 48, 1052–1053/Campaign, 160.

58 Ibid., 1058/Campaign, 167.

59 Ibid., 1065/Campaign, 173.

60 Ibid., 1071/Campaign, 178.

61 See Kaye, ‘Challenging Certainty,’ 44–45.

62 Vom Kriege II. 1, 277; idem II. 2, 291.

63 Vom Kriege II. 2, 288–28; idem II. 3, 303.

64 Clausewitz, ‘Nachricht’ in Vom Kriege, 182–183.

65 Vom Kriege II.2, 295/On War, 144.

66 Ibid., 290.

67 Vom Kriege II. 2, 290 and 295. See also idem VIII. 8, 1007.

68 Sumida, Decoding Clausewitz, 100; see also Andres Engberg-Pedersen, Empire of Chance. The Napoleonic Wars and the Disorder of Things (Cambridge, Massechusetts: Harvard University Press 2015), 136–145.

69 Vom Kriege II. 6, 338–340.

70 Quoted in Kessel, ‘Zur Genesis,’ 421. See also Hahlweg, ‘Vorbemerkung’ to Feldzug, 937.

71 Vom Kriege II. 5, 312–313; cf. Jan Willem Honig, ‘Clausewitz and the Politics of Early Modern Warfare’, in Andreas Herberg-Rothe (e.a.), Clausewitz. The State and War (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag 2011), 30.

72 Vom Kriege II. 5, 317.

73 Ibid., 312.

74 Ibid., 314.

75 Ibid., 325–326.

76 Vom Kriege II. 5, 321/On War, 161. For other examples of counterfactuals see Vom Kriege III. 12, 394–395; idem VIII. 3, 958 (footnote); idem VIII. 8, 1007; idem VIII. 9, 1024–1027, 1031.

77 Vom Kriege II.5, 317–320. See also Catherine Gallagher, ‘The Formalism of Military History’, Representations 104 (2008), 30–31.

78 Feldzug §11, 963/Campaign, 73; see also Feldzug §53, 1089.

79 See Henry Lloyd, War, Society and Enlightenment. The Works of General Lloyd, ed. Patrick J. Speelman (Leiden: Brill, 2005).

80 Gallagher, ‘The Formalism’, 26.

81 Robert Cowley, ed., What If? (London: Pan Books 2002), xviii; and Cowley, What If? (London: Pan Books 2001), xiii.

82 Bunzl, ‘Counterfactual History’, 852.

83 Cowley, What If? (2001) xii.

84 See also Kaye, ‘Challenging Certainty’, 52.

85 Hendrickson, ‘Counterfactual Reasoning’, 365–386; see also Philip Tetlock and Aaron Belkin Tetlock, ‘Counterfactual Thought Experiments in World Politics: Logical, Methodological, and Psychological Perspectives’, in Counterfactual Thought Experiments in World Politics (Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press 1996), 16–31.

86 Hendrickson, ‘Counterfactual Reasoning’, 377.

87 Hendrickson, ‘Counterfactual Reasoning’, 372–373.

88 Hendrickson, ‘Counterfactual Reasoning’, 380.

89 Hendrickson, ‘Counterfactual Reasoning’, 367–368. See also Reis, ‘Counterfactuals’, 712.

90 Robert Citino, ‘Military Histories Old and New: A Reintroduction,’ American Historical Review 112 (2007) 1079; see also Gallagher, ‘The Formalism,’ 32.

91 Beyerchen, ‘Clausewitz, Nonlinearity, and the Unpredictability of War’, International Security 17 (1992–93), 59–90.

92 Terence M. Holmes, Planning versus Chaos in Clausewitz’s On War’, The Journal of Strategic Studies 30 (2007), 130.

93 Paul A. Roth and Thomas A. Ryckman, ‘Chaos, Clio, and Scientific Illusions of Understanding’, History and Theory 34 (1995), 30–44. See also Engberg-Pedersen, Empire of Chance, 66.

94 Thanks are due to Paul Donker, Andreas Herberg-Rothe, Mart Verhage and Michiel Wielema.

95 Downloaded at <http://www.westpoint.edu/history/siteassets/sitepages/napoleonic%20war/napsel119.pdf>.

96 Downloaded at http://www.westpoint.edu/history/siteassets/sitepages/napoleonic%20war/nap68.pdf on 8 August 2016.

Bibliography

- Beyerchen, Alan, ‘Clausewitz, Nonlinearity, and the Unpredictability of War’, International Security 17 (1992-93), 59–90. doi:10.2307/2539130

- Bunzl, Martin, ‘Counterfactual History: A User’s Guide’, The American Historical Review 109 (2004), 845–58. doi:10.1086/587020

- Citino, Robert, ‘Military Histories Old and New: A Reintroduction’, The American Historical Review 112 (2007), 1070–90. doi:10.1086/ahr.112.4.1070

- Clausewitz, Carl von, Vom Kriege, ed. Werner Hahlweg (Bonn: F. Dümmler 1972).

- Clausewitz, Carl von, On War, ed. and trans. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press 1984).

- Clausewitz, Carl von, ‘Feldzug von 1815. Strategische Uebersicht des Feldzugs von 1815 in Clausewitz, Schriften – Aufsätze – Studien – Briefe’, in Werner Hahlweg (ed.), Dokumente aus dem Clausewitz-, Scharnhorst- und Gneisenau- Nachlaß sowie aus öffentlichen und privaten Sammlungen (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht 1990), Vol. II. 2, 943–1118.

- Clausewitz, Carl von, On Waterloo. Clausewitz, Wellington and the Campaign of 1815, transl. and ed. Christopher Bassford, Daniel Moran and Gregory W. Pedlow ( s. l. Clausewitz.com 2010).

- Clausewitz, Carl von, On Wellington, transl. and ed. Peter Hofschröer (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 2010).

- Colson, Bruno, ‘Clausewitz on Waterloo’, War in History 19 (2012), 397–400.

- Cowley, Robert, ed., What If? The World’s Foremost Military Historians Imagine What Might Have Been (London: Pan Books 2001).

- Cowley, Robert, ed., What If? Eminent Historians Imagine What Might Have Been (London: Pan Books 2002).

- Engberg-Pedersen, Anders, Empire of Chance. The Napoleonic Wars and the Disorder of Things (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press 2015).

- Evans, Richard J., Altered Pasts. Counterfactuals in History (Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press 2013).

- Ferguson, Niall, ed., Virtual History. Alternatives and Counterfactuals (s. l.: Basic Books 1997).

- Gallagher, Catherine, ‘The Formalism of Military History’, Representations 104 (2008), 23–33. doi:10.1525/rep.2008.104.1.23

- Gat, Azar, A History of Military Thought from the Enlightenment to the Cold War (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2001).

- Goodman, Nelson, Fact, Fiction and Forecast (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press 1983).

- Hahlweg, Werner, ‘Vorbemerkung’ to Clausewitz, Carl von, ‘Feldzug von 1815. Strategische Uebersicht des Feldzugs von 1815 in Clausewitz, Schriften – Aufsätze – Studien – Briefe’, in Werner Hahlweg (ed.), Dokumente aus dem Clausewitz-, Scharnhorst- und Gneisenau- Nachlaß sowie aus öffentlichen und privaten Sammlungen (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht 1990) vol. II. 2, 936–937.

- Hendrickson, Noel, ‘Counterfactual Reasoning and the Problem of Selecting Antecedent Scenarios’, Synthese 185 (2012), 365–86. doi:10.1007/s11229-010-9824-1

- Herberg-Rothe, Andreas, Clausewitz’s Puzzle. The Political Theory of War (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2007).

- Holmes, Terence, ‘Planning versus Chaos in Clausewitz’s on War’, The Journal of Strategic Studies 30 (2007), 129–51. doi:10.1080/01402390701210855

- Honig, Jan Willem, ‘Clausewitz and the Politics of Early Modern Warfare’, in Andreas Herberg-Rothe ( e.a.), Clausewitz. The State and War (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag 2011), 29–48.

- Kaye, Simon T., ‘Challenging Certainty: The Utility and History of Counterfactualism’, History and Theory 49 (2010), 38–57. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2303.2010.00527.x

- Kessel, Eberhard, ‘Zur Genesis der modernen Kriegslehre. Die Entstehungsgeschichte von Clausewitz’ Buch “Vom Kriege”’, Wehrwissenschaftliche Rundschau 3 (1953), 405–23.

- Lewis, David, Counterfactuals (Oxford: Blackwell 1973).

- Lloyd, Henry, War, Society and Enlightenment. The Works of General Lloyd, ed. Patrick J. Speelman (Leiden: Brill 2005).

- Macaullay, Trevelyan, George ‘If Napoleon Had Won the Battle of Waterloo’, in Clio, a Muse, and Other Essays Literary and Pedestrian (London: Longmans, Green 1913), 184–200.

- Menzies, Peter, ‘Counterfactual Theories of Causation’, The Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy (Fall 2009 Edition), <http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/causation-counterfactual/on>.

- Moran, Daniel, ‘Clausewitz on Waterloo: Napoleon at Bay’, in Christopher Bassford, Daniel Moran and Gregory W. Pedlow (transl. and eds.), On Waterloo. Clausewitz, Wellington and the Campaign of 1815 (s. l. Clausewitz.com 2010), 241.

- Napoléon, Mémoires pour servir à l’histoire de France en 1815, avec le plan de la bataille de Mont-Saint-Jean (Paris: Barrois 1820).

- Nolan, Daniel, ‘Why Historians (and Everyone Else) Should Care about Counterfactuals’, Philosophical Studies 163 (2013), 317–35. doi:10.1007/s11098-011-9817-z

- Paret, Peter, Clausewitz and the State. The Man, His Theories and His Times (Princeton: Princeton University Press 2007).

- Reiss, Julian, ‘Counterfactuals, Thought Experiments, and Singular Causal Analysis in History’, Philosophy of Science 76 (2009), 712–23. doi:10.1086/605826

- Rosenfield, Gavriel, ‘Why Do We Ask “What If?” Reflections on the Function of Alternate History’, History and Theory 41 (2002), 90–103. doi:10.1111/1468-2303.00222

- Roth, Paul A. and Thomas A. Ryckman, ‘Chaos, Clio, and Scientific Illusions of Understanding’, History and Theory 34 (1995), 30–44. doi:10.2307/2505582

- Stoker, Donald, Clausewitz. His Life and Work (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2014).

- Sumida, Jon Tetsuro, Decoding Clausewitz. A New Approach to on War (Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas 2008).

- Tetlock, Philip and Tetlock, Aaron Belkin, ‘Counterfactual Thought Experiments in World Politics: Logical, Methodological, and Psychological Perspectives’ in Counterfactual Thought Experiments in World Politics (Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press 1996), 16–31.

- Wellington, ‘Memorandum on the Battle of Waterloo’, in Christopher, BassfordChristopher, Bassford, Daniel, Moran and Gregory, W. Pedlow (transl. and eds.) On Waterloo. Clausewitz, Wellington and the Campaign of 1815 (s. l. Clausewitz.com 2010), 219–235.