ABSTRACT

Gaining a decisive technological edge is a never-ending pursuit for defence establishments. Intensifying geo-strategic and geo-economic rivalry among major powers, especially the U.S and China, and the global technological revolution occurring in the civilian and military domains, promise to reshape the nature and distribution of global power. This article provides a conceptual framework for a series investigating the state of global defence innovation in the twenty-first century. The series examines defence innovation in small countries with advanced defence innovation capabilities (Israel, Singapore), closed authoritarian powers (North Korea, Russia), large catch-up states (China and India) and advanced large powers (U.S.).

Gaining a decisive technological edge is a never-ending pursuit for defence establishments and the states they protect. This long-run competition for superiority has mostly occurred at a steady incremental pace, but has been occasionally punctuated by periods of disruptive upheaval.Footnote1 The world is currently in one of these whirlpools of revolutionary change brought on by the confluence of two transformational developments. First is the intensifying geo-strategic and geo-economic rivalry among major powers, especially between the U.S. and China. Second is a global technological revolution that is occurring in both the civilian and military domains. These dynamics taken together promises to fundamentally reshape the nature and distribution of global power.

This quest for game-changing innovation has become a pressing priority for the world’s leading military powers, which has led to the mushrooming of organisations set up to expressly develop advanced military technologies and attendant doctrinal and operational strategies in the past decade. The U.S. has been especially prolific, standing up dozens of innovation entities that are part of what is now defined as the national security innovation base. Prominent organisations include the Defense Innovation Unit, Defense Innovation Board, Strategic Capabilities Office, Army Futures Command and NavalX. This augments an already strong innovation bench anchored by storied organisations such as the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). Other countries have followed suit to differing degrees of urgency and scale, with China second in effort and ambition to the U.S.

The rise of these organisations is a teasing indicator of the importance that defence establishments are attaching to innovation. But this observation by itself offers little explanatory power into how well organised, how effective and how serious these countries are in the pursuit of defence innovation and what types of innovation they are seeking. In order to comprehend the dynamics of the global defence innovation landscape, to identify where countries are in this pursuit for the technological frontier, to determine how fast and effectively they are running, and to assess who is winning now and over the long term, it is imperative to look at the entirety of a country’s defence innovation enterprise and how it is connected with the national and global defence technological orders.

This special volume investigates the state of global defence innovation in the twenty-first century through the examination of a select number of states. Seven countries were picked that are representative of the diverse make-up of the global defence innovation community. There are small countries with advanced defence innovation capabilities (Israel and Singapore), closed authoritarian powers (North Korea and Russia), large catch-up states (China and India), and advanced large powers (U.S.). In addition, there is also a case study of emerging technologies focusing on China’s efforts in the development of quantum capabilities.

Defining defence innovation

The starting point of our examination into the global state of defence innovation is to have a clear and precise definition of what is and is not meant by defence innovation. This is because defence innovation is sometimes used interchangeably with other terms and concepts that appear similar, if not identical, but have important differences such as military innovation or national security innovation. Tom Mahnken, Andrew Ross and Tai Ming Cheung have defined defence innovation as the transformation of ideas and knowledge into new or improved products, processes and services for military and dual-use applications.Footnote2 This refers primarily to organisations and activities associated with the defence and dual-use civil–military science, technology and industrial base. They distinguish defence innovation from military innovation, which they say is principally focused on warfighting innovation that encompasses both product innovation and process innovation, technological, operational and organisational innovation and is intended to enhance the military’s ability to prepare for, fight and win wars. In other words, defence innovation is broader and encompasses the civilian domain, especially the defence industrial base and related dual-use commercial base, whereas military innovation is more narrowly focused on the military domain.

Mahnken et al. identify three key components for both defence and military innovation: technological, organisational and doctrinal. Technology serves as the source of the hardware dimension of defence and military innovation and its concrete products. Organisational and doctrinal changes, the software of innovation, provide what is characterised in the broader literature as process innovation. While defence and military innovation address the interrelationships between these three dimensions, there are inherent biases in their primary areas of focus. For defence innovation, the technological dimension occupies a more prominent role because of a greater focus on research, development and acquisition processes. Military innovation has tended to place more emphasis on doctrinal and warfighting issues. This volume reflects this bias by paying more attention to the technological domain, but organisational and doctrinal perspectives are still given plenty of consideration.

A conceptual framework of defence innovation

A conceptual framework is offered here to provide a foundation for general comparative inquiry of defence innovation across countries, technologies and products. This framework specifies a comprehensive set of factors, the relationships between them, levels of analysis and examination of other relevant attributes such as soft and hard innovation factors, and a typology of innovation outcomes. This framework, however, is not intended to provide explanations of behaviour or outcomes, which is the purview of theories and models.Footnote3

This framework is informed by an extensive body of academic research on systems of innovation and public policy processes over the past few decades.Footnote4 The basis of this framework is the concept of a defence innovation system, which derives from the notion of the national innovation system that was put forward in the 1990s.Footnote5 National innovation systems are complex, constantly evolving eco-systems that includes ‘all important economic, social, political, organisational, institutional and other factors that influence the development, diffusion and use of innovations’.Footnote6 The different ways that organisations and institutions are set up and operate within countries help to explain the variation in the national style of innovation.

Frameworks and theories from the study of the public policy process have also been useful in the shaping of the defence innovation systems framework. Three in particular stand out. First is the family of institutional rational choice frameworks that focus on how institutional rules shape the behaviour of rational actors.Footnote7 Second is the punctuated equilibrium framework that argues that policy-making usually takes place incrementally over long periods but is punctuated by brief periods of major change.Footnote8 Third is the advocacy coalition framework that examines the interaction of coalitions within policy subsystems.Footnote9 The defence innovation systems framework incorporates a number of concepts put forward in these frameworks such as networks and subsystems and institutional factors.

Defence innovation is defined as the transformation of ideas and knowledge into new or improved products, processes and services for military and dual-use applications. This definition refers primarily to organisations and activities associated with the defence and dual-use civil–military science, technology and industrial base. Included at this level are, for instance, changes in planning, programming, budgeting, research, development, acquisition and other business processes.

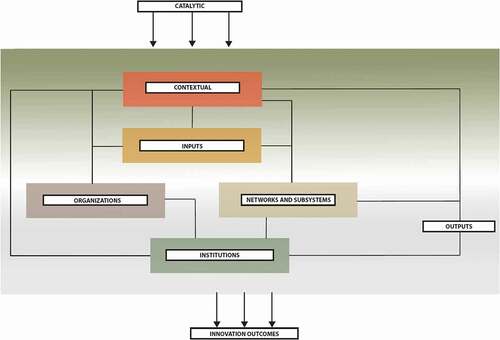

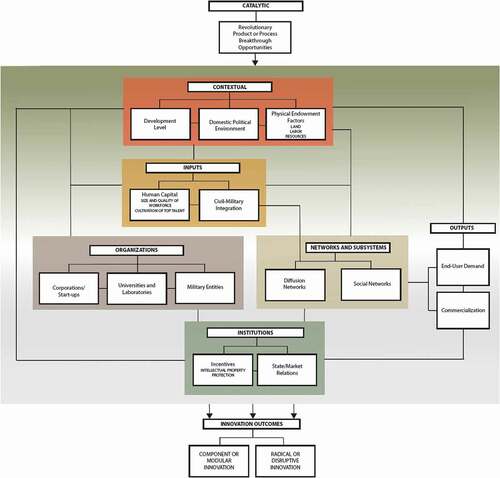

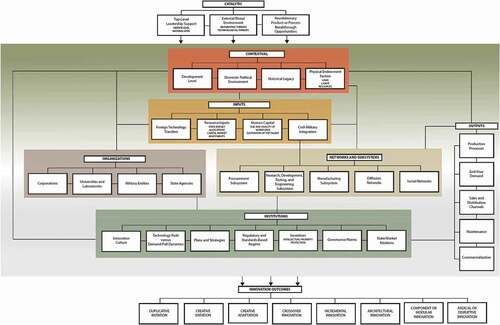

A defence innovation system can be broadly defined as a network of organisations and institutions that interactively pursue science, technology and innovation-related activities to further the development of defence interests and capabilities, especially related to strategic, defence and dual-use civil–military activities (See ). While defence innovation systems have traditionally been bounded by national borders, there has been a growing trend of multi-national defence collaboration, mergers and acquisitions in the post-Cold War era, especially among U.S. and European states, that has eroded this national identity.

Two aspects of this definition of defence innovation systems are worth highlighting. First, organisations refer to entities that are directly or indirectly involved in supporting the innovation process. They would include research institutes, universities, state and party agencies, military units, defence industrial agencies and public and private enterprises at the central and local levels. Second, understanding the nature of interaction between organisations is critical. This is carried out through well-defined institutional arrangements, which are norms, routines, habits, established practices and other rules of the game that exist to guide the workings of the system and the interactions between organisations.Footnote10

Defence innovation systems come in many shapes, sizes and levels of technological advancement, but only a small number of states, on their own or collectively with partner nations, are willing and able to afford to build and sustain the research, development, engineering and production capabilities required to deliver state-of-the-art armaments and military equipment. These complex systems are comprised of numerous components that relate and interact with each other in varied ways.

Categories of factors

A diverse array of factors are involved in the defence innovation process, and the framework distinguishes seven categories (See ):

Catalytic factors: Catalysts are the sparks that ignite innovation of a more disruptive nature. These powerful factors are normally external to the defence innovation system and their intervention occurs at the highest and most influential levels of the ecosystem and can produce the conditions for enabling considerable change and disruption. Without these catalytic factors, the defence innovation system would find it very difficult, if not impossible, to engage in higher end innovation and remain tied to routine modes of incremental innovation.

Input factors: These are material, financial, technological and other forms of contributions that flow into the defence innovation system. Most of these inputs are externally sourced but can also come internally. Resource allocations, technology transfers and civil–military integration are important input factors.

Institutional factors: Institutions are rules, norms, routines, established practices, laws and strategies that regulate the relations and interactions between actors (individuals and groups) within and outside of the defence innovation system.Footnote11 Rules can be formal (laws, regulations and standards) or informal (routines, established practice, and common habits). Norms are shared prescriptions guiding conduct between participants within the system. Strategies refer to plans and guidance that are devised by actors within and outside the defence innovation system.

Organisations and other factors: The principal actors within the defence innovation system and main units of analysis of the framework are organisations, which are formal structures with an explicit purpose and they are consciously created. They include firms, state agencies, universities, research institutes and a diverse array of organised units. Other types of actors are also involved, such as individuals, and they are taken into consideration.Footnote12

Networks and subsystems: Social, professional, virtual and other types of networks allow actors, especially individuals, the means to connect with each other within and beyond defence innovation systems, both domestically and internationally. Networks provide effective channels of sharing information, often more quickly and comprehensively than traditional institutional linkages and they help to overcome barriers to innovation such as rigid compartmentalisation.Footnote13 Subsystems are issue or process-specific networks that link organisations and other actors with each other to produce outputs and outcomes.Footnote14 Numerous subsystems exist within the overall defence innovation system and they can overlap or be nested with each other. The procurement and research and development subsystems are two of the most prominent subsystems.

Contextual factors: This category covers the diverse set of factors that influence and shape the overall defence innovation environment. Contextual determinants that exert strong influence include historical legacy, domestic political environment, development levels and the size of the country and its markets.

Output factors: This category is responsible for determining the nature of the products and processes that come out of the innovation system. They include the production process, commercialisation, the role of market forces such as marketing and sales considerations and the influence of end-user demand.

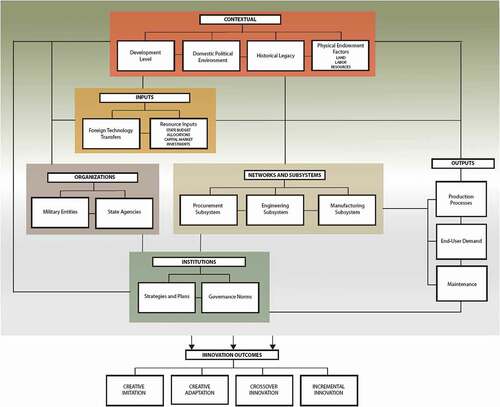

Chart 2. The defence innovation system framework and listing of key variables within the factor categories.

This extensive list of categories and factors, summarized in , is by no means exhaustive and is intended as an initial effort to capture the most salient and significant components and drivers of the defence innovation system. It should be pointed out that the boundaries between these categories are porous and there are instances where factors can overlap between classes. For example, the external threat environment can be both a catalytic and contextual factor, especially if security concerns are sufficiently grave that states mobilise their defence innovation systems to respond to these dangers.

Table 1. List of key categories of factors in the defence innovation system

Relationships between factors

The relationship between these factors determines the performance and outcomes of the defence innovation system. Individual factors by themselves are insufficient to make a far-reaching impact on the innovation process and it is only when they link and interact with other factors that these clusters are able to exert a more profound influence. A number of observations can be made to highlight prominent patterns of association and interaction between factors.

First, catalytic factors have an outsized influence on innovation, especially on higher and more novel types of innovation. But they are only effective if closely linked to other classes of factors in key parts of the defence innovation system, especially those in the input, organisational, institutional, network and subsystem categories. If top leadership support, for example, is coordinated with resource allocations and the research and development subsystem, this offers the opportunity for engaging in higher more disruptive forms of innovation. If leadership support though is absent or weakly connected with these other categories of factors, then any intervention is unlikely to produce meaningful results.

Second, different cluster patterns of factors can be identified depending on the level of development and strategic goals of the defence innovation system:

Incremental catch-up regimes: In economically and technologically underdeveloped countries and their defence innovation systems, absorption-oriented factors are the most important drivers at work (See ). They include technology transfers, organisational and institutional factors that emphasise the importance of the role of the state such as government agencies, and subsystems that are primarily engaged in engineering and production. Catalytic factors do not play a prominent role in these regimes, which means their innovation trajectories are incremental in nature. Examples include India and Brazil.

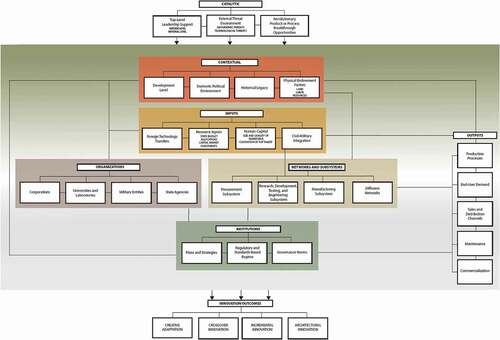

Rapidly catching-up regimes: Many of the same absorption-oriented factors found in incremental catch-up regimes are present in developing countries seeking rapid advancement, but a critical difference is that catalytic factors, especially leadership support and the threat environment, are prominent and link closely with input factors such as resource allocations along with institutional factors like strategies and plans (See ). Moreover, many more factors are engaged in the innovation process compared to its incremental catch-up counterpart, such as the research and development subsystem. China is the proto-typical example of this type of regime.

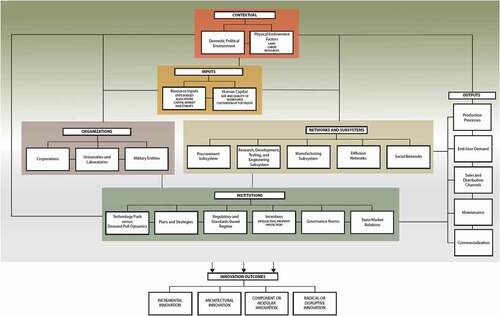

Advanced developed regimes: Factors that promote original innovation are the most important and powerful drivers at play for advanced defence innovation systems (See ). They include bottom-up institutional factors such as market-based governance regimes and incentives supporting risk-taking and intellectual property protection, organisations that encourage market and research activities such as corporations and universities and research institutes and subsystems focused on the generation of original knowledge and products such as the research and development apparatus. The U.S. is a leading example of an advanced developed regime.

Emerging technological domains: In areas focused on the nurturing of emerging technologies, the most important factors are not organisational, institutional, or subsystem classes of factors that are the pillars of conventional well-established defence innovation systems, but factors that emphasise new innovation approaches (See ). This would include (1) a technological environment (counted as both a contextual and catalytic factor) in which revolutionary breakthrough opportunities are possible because of far-reaching shifts underway in the existing techno-economic paradigms; (2) social and professional networks that connect entrepreneurs and those entities focused on early stage, high-risk research; and (3) the embrace of input, market-oriented organisational and institutional factors that encourage risk-taking, experimentation, and new ways of collaboration such as civil–military integration, and the role of start-up and private enterprises.

Levels of analysis

The defence innovation systems framework can be applied to different levels of analysis from the international level to looking at specific projects. In the examination of the country case studies in this volume, the level of analysis is at the national level. But the framework can also be used to look at lower levels such as at the industry sector (e.g. the aviation and shipbuilding industries) or sub-sectoral level (the fighter aviation and surface warship construction sub-industries), at specific technologies (such as artificial intelligence and hypersonics), and also at individual programmes and projects.

Hard vs. soft innovation factors

Another way to distinguish factors in the defence innovation system is to divide them into ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ innovation categories (See ).Footnote15 Hard innovation capabilities are input and infrastructure factors intended to advance technological and product development. This includes research and development facilities such as laboratories, research institutes and universities, human capital, firm-level capabilities and participation, manufacturing capabilities, access to foreign technology and knowledge markets, availability of funding sources from state and non-state sources, and geographical proximity, such as through clusters. These hard innovation capabilities attract the most analytical attention because they are tangible and can be measured and quantified.

Table 2. List of key factors driving the defence innovation system incorporating the hard, soft, and critical factors categories

Soft innovation capabilities are broader in scope than hard factors and cover political, institutional, relational, social, ideational and other factors that shape non-technological and process-related innovative activity. This is what innovation scholars define as ‘social capability’.Footnote16 These soft capabilities include organisational, marketing and entrepreneurial skills as well as governance factors such as the existence and effectiveness of legal and regulatory regimes, the role of political leadership, promotion of standards, corporate governance mechanisms and the general operating environment that the eco-system is located within.

It should be pointed out that the ‘hard–soft’ and functional factor frameworks are not dueling approaches but can be integrated to offer an even more nuanced categorisation of the factors at play in the defence innovation system.

Types of innovation outcomes

There are an array of innovation outcomes resulting from the interactions among the various factors of this framework that extend from simple copying at one end to highly sophisticated disruptive innovation at the other:

Duplicative Imitation: Products, usually obtained from foreign sources, are closely copied with little or no technological improvements. This is the starting point of industrial and technological development for latecomers. The process begins with the acquisition of foreign technology, which then goes directly into production with virtually no technology development or engineering and manufacturing development.

Creative Imitation: This represents a more sophisticated form of imitation that generates imitative products with new performance features. Domestic research input is relatively low, but is beginning to find its way into modest improvements in components or non-core areas. The development process becomes more robust with more work done in the technology development and engineering and manufacturing stages. The work here is primarily how to integrate domestic components into the dominant foreign platform.

Creative Adaptation: Products are inspired by existing foreign-derived technologies but can differ from them significantly. This can also be called advanced imitation. One of the primary forms of creative adaptation is reverse engineering. There is considerably more research conducted here than in the creative imitation stage, especially in product or concept refinement, and there is also significantly more effort and work to combine higher levels of domestic content onto an existing foreign platform.

Crossover Innovation: This refers to products jointly developed by Chinese and foreign partners with significant technology and knowledge transfers to the local side that result in the creation of a R&D base able to conduct independent and original innovation activities. However, there is still considerable reliance on foreign countries for technological and managerial input to ensure that projects come to fruition.

Incremental Innovation: This is the limited updating and improvement of existing indigenously developed systems and processes. Incremental innovation can be the gradual upgrading of a system through the introduction of improved subsystems, but it is also often the result of organisational and management inputs aimed at producing different versions of products tailored to different markets and users, rather than significant technological improvements through original research and development.

Architectural Innovation: This can be distinguished between product and process variants. Architectural product innovation refers to ‘innovations that change the way in which the components of a product are linked together, while leaving the core design concepts (and thus the basic knowledge underlying the components) untouched.’Footnote17 Architectural process innovation refers to the redesign of production systems in an integrated approach (involving management, engineers and workers as well as input from end-users) that significantly improves processes but does not usually result in radical product innovation. The primary enablers are improvements in organisational, marketing, management, systems integration, and doctrinal processes and knowledge that are coupled with a deep understanding of market requirements and close-knit relationships between producers, suppliers and users. As these are also the same factors responsible for driving incremental innovation, distinguishing between these different types of innovation poses a major analytical challenge. While many of these soft capabilities enabling architectural innovation may appear to be modest and unremarkable, they have the potential to cause significant, even discontinuous consequences through the reconfiguration of existing technologies in far more efficient and competitive ways that challenge or overturn the dominance of established leaders.

Component or modular innovation: This involves the development of new component technology that can be installed into existing system architecture. Modular innovation emphasises hard innovation capabilities such as advanced R&D facilities, a cadre of experienced scientists and engineers, and large-scale investment outlays.

Radical or disruptive innovation: This requires major breakthroughs in both new component technology and architecture and only countries with broad-based, world-class R&D capabilities and personnel along with deep financial resources and a willingness to take risk can engage in this activity.

Case studies

This special issue explores in detail the defence innovation systems of seven countries. Altogether, these case studies provide a rich and varied application of the defence innovation framework that offers insightful comparative perspectives. We will begin by briefly summarizing the major categories of innovation factors shaping each of these defence innovation systems and then discuss the key findings. The cases can be sorted into the four framework variants: incremental catch-up, rapidly catching-up, advanced developed and emerging technological regimes.

Incremental catch-up regimes: India

India is the only state among the case studies that fit the definition of an incremental catch-up regime, although many other countries would fall into this category. Laxman Kumar Behera paints a portrait of a country with a sub-optimal performance in defence innovation. This is because of a diverse array of reasons, of which several stand out. First is the absence of catalytic factors in providing leadership, direction, or any outside impetus to a slow-moving and dysfunctional defence innovation system. Behera points out that the role of leadership in defence innovation ‘does not often go beyond lip service’. Second, several contextual factors exert an influential role in shaping the fundamental characteristics of India’s approach to defence innovation. They include the backward state of the overall science and technology ecosystem and the powerful historical legacy of a state-dominated central planning system.

Third is the throttling of inputs going into the defence innovation system. In the late 2010s, only 6% of the Indian defence budget was annually ear-marked for research and development, significantly less than the likes of the U.S. and China. Other input factors are similarly less than sufficient for engaging in moving up the innovation ladder. Behera says that civil–military integration is largely neglected while the nurturing of human capital is underwhelming with only 10% of defence scientists receiving PhDs. One input factor that has had some positive impact is the inflow of foreign technology transfers from the Soviet Union/Russia, Western Europe and more recently the U.S., but the Indian DIS has only been able to partially absorb these foreign capabilities.

Fourth, institutional factors within the Indian DIS hinder more than facilitate innovation. Norms, routines and the governance regime are overly bureaucratic, strictly compartmentalised and risk-adverse. Moreover, Behera argues that there is a lack of strategic planning and guidance and development programmes are often undertaken in ad hoc style. Fifth, organisational factors also contribute to the weak innovation performance of the Indian DIS. The most significant factor is the tight monopoly on the R&D held by the Defence Research and Development Organization (DRDO), whose track record is mixed. Manufacturing is also dominated by a limited number of state-owned entities composed of Defence Public Sector Undertakings and ordnance factories. There are a couple of public firms, Hindustan Aeronautics and Bharat Electronics, but Behera points out that they have only modest intellectual property portfolios.

Sixth, the Indian DIS has a proliferation of subsystems, but there is deep horizontal separation between them, which adds to truncated innovation dynamics. For example, the links between the procurement and production subsystems are limited, and the procurement system itself is characterised by dysfunction caused by strong distrust and competition between end-users and producers and developers. Seventh, output factors reflect the incremental nature of the Indian DIS. The manufacturing base is able to produce third generation conventional platforms, but lacks the technological capabilities to upgrade to more advanced cutting-edge weapons and equipment.

One important caveat though is that the strategic weapons component of the Indian DIS has demonstrated a much better track record for innovation than its conventional counterpart. Innovation in nuclear, ballistic missiles and space capabilities has been a bright spot in an otherwise lackluster Indian innovation landscape.

Rapidly catching-up regimes: North Korea

In contrast to India’s weak efforts at defence innovation, North Korea has been far more successful in its efforts to advance up the innovation ladder primarily limited to strategic capabilities. The focus of the essay by Stephan Haggard and Tai Ming Cheung is on North Korea’s accomplishments in indigenously building nuclear weapons and long-range ballistic missiles. The North Korean case is particularly fascinating because of this extraordinary development of advanced military capabilities in a severely underdeveloped and isolated country.

Catalytic factors in the form of leadership intervention and a severe external threat environment have been outsized influences in driving the development of North Korea’s strategic weapons capabilities. A highly authoritarian and intensely focused leadership has been able to mobilise the entire resources of the country for an extended period to pursue its strategic goal of the indigenous development of a nuclear deterrence capability regardless of the enormous economic and social costs at home and isolation abroad. This is especially the case under Kim Jong Un, who has shown a laser-like focus and dedication to the development of strategic weapons capabilities far greater than his father and grandfather.

This single-minded determination of the Kim dynasty to produce a homegrown nuclear deterrence has been driven by a deep-seated fear that its survival is under threat from the U.S. and its regional allies, especially South Korea and Japan. North Korea has been on a permanent war-footing ever since its founding in the late 1940s. Up until the 1990s, Pyongyang’s foremost priority was on building up a conventional military industrial complex. But after losing access to military assistance from the Soviet Union, who had been a long-time patron and strategic ally, North Korea’s attention turned to the development of strategic weapons capabilities. North Korea’s already profound sense of external threat became even more acute from the 1990s onwards with its protracted nuclear standoff with the international community as well as the spectre of the fall of other pariah regimes such as Libya and Iraq from Western military intervention.

A central focus of Haggard and Cheung’s chapter is the close relationship between external technology inputs and domestic innovation capabilities. North Korea has benefited greatly from access to foreign technology and knowledge, especially in the early stages of research and development but also in the later engineering and testing stages. The North Korean state has cultivated a well-connected international network of suppliers and collaborators stretching from Pakistan and India to Libya, Iraq and Syria. The cultivation of human talent is another important input factor accounting for North Korea’s progress in developing its strategic weapons capabilities. North Korea has nurtured a cadre of well-trained and experienced scientists and engineers across the full range of scientific, technological and engineering disciplines needed for nuclear weapons and ballistic missiles.

Haggard and Cheung point out that North Korea’s ability to effectively marshal its limited resources and push ahead with its nuclear weapons and ballistic missile programmes shows the advantages of its state-socialist system to establish discreet highly functioning and tightly integrated networks and subsystems so long as they enjoy top-level support. The North Korean strategic weapons innovation system has fostered an effective systems integration capability able to manage the complex design, research, development and engineering processes involved in the absorption and reverse engineering of foreign technologies and marrying this with domestically developed technologies.

Another distinctive characteristic and strength of the strategic weapons innovation system is an institutional culture that is willing to take risks, learn from mistakes, be flexible and adaptive, and to learn while doing. Haggard and Cheung say that this attribute stands in sharp contrast with the strict ideological, risk-adverse and tightly regimented norms of the overall North Korean political system.

In conclusion, Haggard and Cheung argue that the effectiveness of North Korea’s strategic weapons innovation system ultimately rests on the relentless buildup of domestic research and heavy industrial capabilities under a highly centralised, state-led and top-down ‘big engineering’ approach. The North Korean strategic weapons system, along with its conventional weapons counterpart, has become a mainstay of the regime, enjoying privileged status and representation at the highest levels of the state, party and military apparatuses. It has also become the indispensable insurance policy for the Kim dynasty’s continued hold on power.

Advanced developed regimes: U.S., Israel, Singapore and Russia

Four of the case studies can be categorised as advanced developed regimes. They are the U.S., Israel, Singapore and Russia. While the defence industrial bases of these states share the common characteristics of being technologically advanced and industrially mature, there are wide variations among them such as size, breadth of technological specialisation and nature of political systems, so it is unsurprising that their defence innovation systems are organised and operate in very different ways.

The U.S. has been the world’s unrivalled defence innovation leader since the end of Cold War, and although there is growing debate that its superiority is at serious risk because of fierce external competition and domestic dysfunction, Eugene Gholz and Harvey Sapolsky say they are ‘sanguine’ that U.S. dominance is intact because the US defence innovation system has a very different and unique set of factors that keeps the country far ahead of any potential rivals. They argue that the combination of hard and soft innovation capabilities that the U.S. excels in will allow the country to ‘remain at the cutting edge’ and unlikely to be challenged for the foreseeable future. Gholz and Sapolsky highlight a number of factors within the input, organisational and institutional categories that stand out as being central to U.S. defence innovation leadership.

First is the input factor of strong defence R&D spending that extends back over more than seven decades. This mobilisation of resources on such a vast scale and over such a long period means the U.S. ‘will not readily fall behind in weapons technology or quality’, Gholz and Sapolsky argue. Second is the organisational factor of special public-private hybrid organisations called federally funded research and development centres and university affiliated research centres that provide unbiased technical advice and a mechanism for the accumulation of knowledge. Gholz and Sapolsky say these entities play a vital role in creating and preserving the ‘soft’ innovation capabilities of the U.S. defence R&D system as a reservoir of institutional memory of past R&D efforts and their independence that prevents capture by the state.

Gholz and Sapolsky also point to three types of institutional factors that act as powerful incentives for innovation. The first is a strong aversion to casualties that is shaped by labour shortages and the democratic nature of the U.S. political system. This has created an institutional culture that favours substituting technology for manpower. Second is the bureaucratic rivalry that exists among different branches of the U.S. defence establishment, especially inter-service competition. Third is a welcoming approach to immigration that has allowed for the importation of new ideas.

While Gholz and Sapolsky also believe that the threat environment plays a highly influential role, they view the threat argument as self-serving, or more precisely self-licking as spelled out in the title of their chapter. They argue that the U.S. is a very secure country surrounded by two big oceans and two unthreatening neighbours. The ‘large threat assessment apparatus’ that was established during the Cold War is now looking for ‘every imaginable threat’ to justify the maintenance and upkeep of the huge and very costly U.S. defence innovation system.

Richard Bitzinger contrasts Israel and Singapore and points out that although Israel and Singapore share many similar geo-strategic, national security and defence technological attributes, there is a ‘marked gap in achievement’ in defence innovation between the two countries. This difference can be teased out when comparing the critical factors at play in the shaping, orchestration and conduct of their defence innovation systems. First, in terms of catalytic factors, the threat environment exerts a profound influence on Israel, which views itself as under permanent siege by hostile neighbours. Singapore also sees itself in a dangerous regional security environment, but its neighbours are far less militant or capable than those in Israel’s backyard and so the threat environment is less of a catalytic factor and more of a contextual factor.

Second, Israel and Singapore share a number of similar contextual factors that have played fundamental roles in shaping the foundations of their approaches to defence industrialisation and innovation. They both share a historical legacy of being born in hostile circumstances and needing to arm and defend themselves with overwhelming firepower as quickly as possible. Moreover, they both have similar geographical profiles of a lack of strategic depth and consequently require advanced military capabilities for a strong forward defence. The critical difference though is that Israel has gone to war several times, while Singapore has managed to avoid conflict so far.

Third, there is considerable overlap in the make-up of the input factors of both countries. They both invest heavily in defence S&T. Ten per cent of Singapore’s defence budget, for example, is spent on research and development. They both have a very strong and well-educated pool of scientific and technological talent to feed into their defence innovation systems. Both countries are also heavily dependent on foreign acquisitions of military capabilities, especially from the U.S., although Israel is able to modify some of these imports with its own indigenous sub-systems. Civil–military integration is also pursued vigorously by both countries as their industrial economies are too small to compartmentalise between civilian and defence activities.

Fourth, the organisational configuration of the Israeli and Singaporean defence innovation systems is also broadly comparable. State-affiliated actors are the dominant players in the corporate and research and development realms. Three of the four top Israeli defence firms are state-owned, as is Singapore’s monopoly defence enterprise. Government agencies exert a powerful grip on the defence S&T apparatus in both countries.

Fifth, one category though where there are significant differences between Israel and Singapore is in institutional factors. Israel has an institutional culture that emphasises improvisation, has limited interest in planning and developing long-range strategies, and embraces continuous ongoing innovation. Singapore by contrast has a far more rigid innovation culture that is risk adverse, strongly embraces planning and strategies, emphasises state control over market forces in picking winners and losers, and has cultivated a conservative governance regime.

Sixth, yet another category that highlights the differences between the Israeli and Singaporean defence innovation systems is networks and subsystems. A central characteristic of Israeli networks is that they are non-hierarchical, informal and adaptive. This allows for excellent access among participants at all levels, strong flows of information and ultimately a highly effective diffusion process. By contrast, Singapore is a more traditional hierarchical regime. One important similarity between these two countries due to their conscription systems is that they both have tight elite networks of politicians, cabinet ministers, corporate chiefs and other well-placed leaders who knew each other while serving in the military. This allows for the leaderships of these defence innovation systems to have access to their counterparts elsewhere within these countries.

Seventh, there are some notable similarities in output factors between Israel and Singapore. The influence of end-user requirements from the warfighters is strong in both the two countries. Another similarity is that they both have specialised niche manufacturing bases as they are both unable to afford or maintain a comprehensive suite of defence production capabilities. Israel though has a more extensive and sophisticated portfolio of products compared to Singapore that has made its companies successful on the international arms market.

In conclusion, while the Israeli and Singaporean defence innovation systems share many common traits, especially in contextual, organisational and output factors, it is the differences that are more significant and explains why the innovation performances and profiles of these two countries are so divergent. These differences are primarily catalytic, institutional and network factors such as the severity of the threat environment, social networks and institutional culture, which are also ‘soft’ in nature.

Russia has been drawing global attention to its defence innovation developments since the late 2010s. In major policy speeches, President Vladimir Putin has showcased his government’s investment in the development of new generations of advanced defence technological capabilities as a cornerstone of his efforts to ensure that Russia remains a leading global military power. Vasily Kashin examines how motivated, capable and ambitious Russia actually is in the pursuit of world class defence innovation.

Kashin points to two events that were catalytic in shaping Russia’s strategic and conventional defence innovation efforts in the twenty-first century. The first was the withdrawal of the U.S. from the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty in 2002, which led Russia to significantly step up the development of strategic capabilities to ensure strategic stability and deterrence. Kashin said Russia focused its efforts on a limited number of highly ambitious but also risky breakthrough projects such as hypersonic glider re-entry vehicles for ICBMs and new generations of strategic cruise missiles at the expense of the continued upgrading of its existing arsenals.

For the conventional sector, Kashin says the catalytic turning point was Russia’s war with Georgia in 2008. Although Russia won the conflict against its much smaller and weaker neighbour, it exposed critical weaknesses in Russia’s command and control structure, weak reconnaissance capabilities and inadequate personnel training. Kashin makes an interesting comparison between the May 1999 US bombing of the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade and the Georgia campaign. The embassy bombing sparked Beijing to embark on a major effort to improve its defence innovation system. In the Georgia conflict, Kashin says that there were widespread suspicions among Russian decision-makers that the U.S. was a key instigator behind Georgia’s activities against Russia. The conflict led to Russia’s reassessment of its relations with the West, which turned from cooperative to more competitive and adversarial.

Kashin offers a detailed layout of the organisational actors and institutional features of the Russian defence innovation system. The principal organisational actors include the Ministry of Defence and the Advanced Research Foundation, which is sometimes compared to DARPA in the U.S., but is very different in set-up and focus. The most important entity though is the Defence Industrial Commission, a government inter-agency body that is directly under the leadership of the Russian President. Vladimir Putin is actively engaged in defence innovation matters and is the supreme arbiter. An important point that Kashin makes is that these organisations are not simply content with focusing their efforts in the defence domain but are keen to broaden their responsibility for promoting innovation across the rest of the Russian national innovation system as well.

But with the limited financial and other resources that the mid-sized Russian economy is able to generate and afford to devote to defence needs compared to the U.S., China and other advanced states, Kashin argues that Russia’s only viable option to keep up militarily with the global frontier is to concentrate its efforts in a select few areas such as nuclear-armed long-range intercontinental ballistic missiles, a non-nuclear strategic deterrence such as hypersonic weapons, air defence systems and a limited array of ground-based weapons. Areas not deemed of sufficiently high priority in current Russian military doctrine such as long-range air and naval power projection capabilities are being sacrificed. Kashin points out that Moscow views the long-term international threat environment to be increasingly complex and hostile, which requires continued commitment to the modernisation of its nuclear triad and more attention and resources to be devoted to emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence, directed energy weapons, hypersonic weapons and robotics.

Emerging technological domains: China’s efforts in quantum technologies

In addition to the country case studies, there is one emerging technology-focused case study by Elsa Kania on China’s development of quantum technologies that have both military and civilian applications. In Kania’s examination of China’s efforts to develop its quantum capabilities, she sees innovation being driven by some of the same factors that are also prominent in conventional domains, of which top-level leadership support and the threat environment stand out. Kania paints a picture of a rapidly developing Chinese quantum innovation eco-system that enjoys strong high-level support among party, state, military and corporate elites, of which Xi Jinping stands out at the very top. This was highlighted most prominently by a Politburo study session on quantum development that was hosted by Xi in October 2020. Underpinning the leadership’s vigorous backing for the development of quantum capabilities are their concerns about the rising threat environment, especially the vulnerability of the country’s communications infrastructure through sophisticated technology-based intelligence gathering activities led by the U.S. Kania points to the Edward Snowden incident in 2013 in which the National Security Agency contractor leaked extensive details of U.S. penetration of foreign networks, including within China, as a pivotal event behind the Chinese leadership’s embrace of quantum technologies that would provide highly secure communications capabilities such as through unbreakable cryptography.

The development of the Chinese quantum innovation ecosystem offers useful insights into how China more generally is going about in establishing itself as a leading player in a broader array of emerging technology sectors. The general approach is through what can be described as a selective authoritarian mobilisation development model, in which the Chinese authorities mobilize and concentrate resources through a statist top-down allocation process to a highly selective group of sectors.Footnote18 This is done through various mechanisms that Kania points out, such as state-directed plans and policies in the form of Five-Year Science and Technology Development Plans, the Strategic Emerging Industries initiative and the Made in China 2025 industrial plan. But there are also new tools being adopted such as the use of provincial and market-supported funding mechanisms that Kania identifies.

Human talent is another prominent characteristic in driving quantum innovation. While high-end human talent is critical across all defence S&T fields, it is doubly so in the quantum realm. Kania points to a number talent recruitment and educational programmes and activities and argues that China has had considerable success in nurturing a homegrown quantum talent pool that makes it less reliant on foreign talent transfers than in other technological domains.

An important distinguishing characteristic of the Chinese quantum innovation system that supports the framework put forward of emerging technological domains is the prominent role played by professional and social networks in promoting knowledge creation and diffusion. Kania points to the forging of domestic and foreign productive partnerships, especially among key quantum hubs such as the Key Laboratory of Quantum Information at the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) and quantum centres at Tsinghua and Fudan Universities. USTC appears to be the most important node for quantum collaboration with foreign and military entities. This includes a joint research project with the Austrian Academy of Sciences and partnerships with Chinese defence corporations.

Another novel feature of the Chinese quantum innovation system is the role of private sector entities that have been generally absent in China’s defense innovation system. The Alibaba Quantum Computing Lab is a rare example of a private entity participating in high-end strategic innovation in China, but whether it is a one-off or represents the start of a new trend of growing private sector involvement in cutting-edge innovation could have a profound impact in shaping China’s long-term technology development trajectory.

Key findings

A number of themes emerge from these case studies. First, catalytic factors are critically important. The threat environment and the role of high-level leadership support are highlighted in a number of the cases, especially Israel and North Korea. Catalytic factors are especially critical for the pursuit of disruptive innovation. The oft-noted contemporary intensification of geopolitical competition can be expected to catalyse competition for defence and military prowess generally and for defence and military innovation specifically. Leading and rising catch-up powers perhaps will be the most likely to pursue ambitious, across-the-board innovation programmes. Their defence and military planners and operators will be attracted by new, emerging and over-the-horizon technologies, such as cyber, AI and quantum computing, that are perceived, correctly or incorrectly, as promising either breakthroughs or discontinuous, disruptive innovation (even as those planners and operators struggle with how to effectively employ new cyber, AI, quantum and other tools).

Innovation by mid-size and small states is more likely to be focused on the development of niche rather than across-the-board capabilities; architectural innovation – the reconfiguration of hardware and software, of technology, doctrine and organisation – may prove particularly attractive to this group of states. In the absence of limits on the development, production, acquisition, deployment and employment of new capabilities – the next big, new thing, or game changer, may not be a good thing – the impetus given to defence and military innovation by an intensification of geopolitical conflict may well pose risks to regional and global order and stability.

New, emerging and over-the-horizon technologies – which are as likely as not to be imported by the defence sector from the commercial sector (rather than, as in the past, exported by the defence sector to the commercial sector) and, as a result of the globalisation of R&D, will be broadly disseminated – may be as likely to undermine as to enhance security, even contributing to the onset of, or exacerbation of, arms races and security dilemmas. As, or perhaps if, geopolitically spurred competition for defence and military innovation intensifies, it should not be assumed that a competitive advantage automatically accrues to authoritarian, centrally planned economies that target a select set of emerging technologies. Matthew Evangelista long ago demonstrated that a bottom-up, decentralised approach to defence and military innovation can best a top-down, centralised approach – that the latter can actually inhibit innovation. Gholz and Sapolsky, too, note the advantages of the competitive, decentralised approach to defence and military innovation enjoyed by the U.S.

A third cluster of attributes identified as having considerable impact on innovation are social and strategic culture-related factors, although their influence is more in an indirect context of providing a positive supporting environment rather than playing a direct role. In the case of the U.S., for example, social and political dynamics related to technology substitution for labour and an immigration-friendly social environment are viewed as having had an important role in shaping the U.S. defence innovation culture. The influence of social traits is even more pronounced in Israel with the prevalence of assertive, risk-taking and non-hierarchical norms a key factor behind its free-wheeling disruptive innovation environment. The opposite is true in Singapore where a more risk-adverse and hierarchical social order means that the preference is for more routine incremental innovation.

Fourth, the nature and intensity of innovation will depend on the level of sophistication and development of a state’s defence innovation system. Advanced and well-endowed innovation systems such as the U.S. are much more able to pursue higher-end innovation than underdeveloped catch-up countries that will be limited to imitation and lower-end innovation.

Fifth, the linkages between factors, especially different categories of factors, are important. Close working connections between catalytic factors and input, process and institutional-related factors would enable higher levels of innovation outcomes. If top leadership support is closely linked to budgets and acquisition processes, for example, this would identify pathways for innovation to take place. But if leadership support is isolated and affiliated with critical enabling factors elsewhere in the innovation system, then the pathways to progress will be absent.

We conclude with a brief discussion about the state of the defense innovation subfield and the next steps in its development. From the outset, this article was based on the modest goal of offering a conceptual framework of defence innovation that pinpoints and bring together the tacit assumptions that have been made by the articles in this special volume as well as by other scholars toiling in the defence innovation sub-field. The framework offered here represents a summation of the state of the field and is intended to set the stage for more explicit theory building and testing that will help to produce more rigorous and generalisable examinations. These next steps in the research agenda could not be more timely as the world faces the prospects of a more intensive and disruptive phase in the global defence innovation race brought on by the global revolution in technology affairs and the fierce techno-security rivalry between the U.S., China and their allies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tai Ming Cheung

Tai Ming Cheung is the director of the University of California Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation and a professor at the School of Global Policy and Strategy at the University of California San Diego in La Jolla, California.

Notes

1 For technological deterministic perspectives, see Michael C. Horowitz, The Diffusion of Military Power: Causes and Consequences for International Politics (Princeton, New Jersey; Princeton University Press, 2010) and Jeremy Black, War and Technology (Indiana University Press, 2013). For the political, social, and domestic drivers behind military revolutions, see MacGregor Knox and Williamson Murray (Eds), The Dynamics of Military Revolution, 1300–2050 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2001); and Geoffrey Parker, The Military Revolution: Military Innovation and the Rise of the West, 1500–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1996).

2 Tai Ming Cheung, Thomas G. Mahnken, and Andrew L. Ross, ‘Frameworks for Analyzing Chinese Defense and Military Innovation’, in Tai Ming Cheung (Ed), Forging China’s Military Might: A New Framework for Assessing Innovation (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014).

3 See Edella Schlager, ‘A Comparison of Frameworks, Theories, and Models of Policy Processes’, in Paul A. Sabatier (Ed), Theories of the Policy Process (Boulder, Co: Westview 2007).

4 Charles Edquist and Bjorn Johnson, ‘Institutions and Organizations in Systems of Innovation’, in Charles Edquist (Ed), Systems of Innovation: Technologies, Institutions and Organizations (Oxford: Routledge, 2005); and Charles Edquist, ‘Systems of Innovation: Perspectives and Challenges’, in Jan Fagerberg, Richard Nelson, and David Mowery, The Oxford Handbook of Innovation (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004).

5 See Richard Nelson (Ed), National Innovation Systems (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993).

6 Edquist, ‘Systems of Innovation: Perspectives and Challenges’.

7 Elinor Ostrom, ‘Institutional Rational Choice: An Assessment of the Institutional Analysis and Development Framework’, in Sabatier, Theories of the Policy Process.

8 Frank Baumgartner and Bryan Jones, Agendas and Instability in American Politics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), and Bryan Jones, Frank Baumgartner, and James True, ‘Policy Punctuations: U.S. Budget Authority, 1947–1995ʹ, Journal of Politics, 60 (February 1998).

9 Paul Sabatier and Christopher Weible, ‘The Advocacy Coalition Framework’, in Paul A. Sabatier (Ed), Theories of the Policy Process (Boulder, Co: Westview 2007).

10 Douglass North, Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1990), 4–5.

11 Edquist and Johnson, ‘Institutions and Organizations in Systems of Innovation’, 46; and Elinor Ostrom, ‘Institutional Rational Choice: An Assessment of the Institutional Analysis and Development Framework’, in Sabatier, Theories of the Policy Process, 26.

12 Edquist and Johnson, ‘Institutions and Organizations in Systems of Innovation’, 56.

13 Mark Zachary Taylor, The Politics of Innovation (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), 157–68.

14 Christopher Weible, Tanya Heikkila, Peter deLeon and Paul Sabatier, ‘Understanding and Influencing the Policy Process’, Policy Sciences 45/1 (March 2012); and Hank C. Jenkins-Smith, Daniel Nohrstedt, Christopher Weible, and Karin Ingold, ‘The Advocacy Coalition Framework: An Overview of the Research Program’, in Christopher Weible (Ed), Theories of the Policy Process (New York: Routledge, 2018).

15 For an expanded discussion, see Tai Ming Cheung, ‘The Chinese Defence Economy’s Long March from Imitation to Innovation’, Journal of Strategic Studies 34/3 (June 2011).

16 Moses Abramovitz, ‘Catching Up, Forging Ahead, and Falling Behind’, Journal of Economic History 46/386 (June,1986).

17 Rebecca Henderson and Kim Clark, ‘Architectural Innovation: The Reconfiguration of Existing Product Technologies and the Failure of Established Firms,’ Administrative Science Quarterly 35/1 (March 1990) 10.

18 See Tai Ming Cheung, Innovate to Dominate: The Making of the Chinese Techno-Security State and Implications for the Global Order (Forthcoming).

Bibliography

- Abramovitz, Moses, ‘Catching Up, Forging Ahead, and Falling Behind’, Journal of Economic History 46/386 (June 1986), 385–406.

- Baumgartner, Frank and Bryan Jones, Agendas and Instability in American Politics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press 1993).

- Black, Jeremy, War and Technology (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press 2013).

- Cheung, Tai Ming, ‘The Chinese Defence Economy’s Long March from Imitation to Innovation’, Journal of Strategic Studies 34/3 (June 2011), 325–354.

- Cheung, Tai Ming, Innovate to Dominate: The Making of the Chinese Techno-Security State and Implications for the Global Order (Irhaca, NY: Cornell University Press 2022).

- Cheung, Tai Ming, Thomas G. Mahnken, and Andrew L. Ross, ‘Frameworks for Analyzing Chinese Defense and Military Innovation’, in Tai Ming Cheung (ed.), Forging China’s Military Might: A New Framework for Assessing Innovation (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press 2014, 15–46).

- Edquist, Charles, ‘Systems of Innovation: Perspectives and Challenges’, in Jan Fagerberg, Richard Nelson, and David Mowery (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Innovation (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2004), 181–208.

- Edquist, Charles and Bjorn Johnson, ‘Institutions and Organizations in Systems of Innovation’, in Charles Edquist (ed.), Systems of Innovation: Technologies, Institutions and Organizations (Oxford: Routledge 2005), 41–63.

- Henderson, Rebecca and Kim Clark, ‘Architectural Innovation: The Reconfiguration of Existing Product Technologies and the Failure of Established Firms’, Administrative Science Quarterly 35/1 (March 1990), 9–30.

- Horowitz, Michael C., The Diffusion of Military Power: Causes and Consequences for International Politics (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press 2010).

- Jenkins-Smith, Hank C., Daniel Nohrstedt, Christopher Weible, and Karin Ingold, ‘The Advocacy Coalition Framework: An Overview of the Research Program’, in Christopher Weible (ed.), Theories of the Policy Process (New York: Routledge 2018), 135-171.

- Jones, Bryan, Frank Baumgartner, and James True, ‘Policy Punctuations: U.S. Budget Authority, 1947–1995’, The Journal of Politics 60/1 (February 1998), 1–33. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2647999

- Knox, MacGregor and Williamson Murray, Eds, The Dynamics of Military Revolution, 1300-2050 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2001).

- Nelson, Richard, Ed, National Innovation Systems (New York: Oxford University Press 1993).

- North, Douglass, Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1990).

- Ostrom, Elinor, ‘Institutional Rational Choice: An Assessment of the Institutional Analysis and Development Framework’, in Paul A. Sabatier (ed.), Theories of the Policy Process, 2nded. (Boulder, Co: Westview 2007), 21–64.

- Parker, Geoffrey, The Military Revolution: Military Innovation and the Rise of the West, 1500-1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1996).

- Sabatier, Paul and Christopher Weible, ‘The Advocacy Coalition Framework’, in Paul A. Sabatier (ed.), Theories of the Policy Process (Boulder, Co: Westview 2007), 189–220.

- Schlager, Edella, ‘A Comparison of Frameworks, Theories, and Models of Policy Processes’, in Paul A. Sabatier (ed.), Theories of the Policy Process (Boulder, Co: Westview 2007), 293–320.

- Taylor, Mark Zachary, The Politics of Innovation (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2016).

- Weible, Christopher, Tanya Heikkila, Peter deLeon, and Paul Sabatier, ‘Understanding and Influencing the Policy Process’, Policy Sciences 45/1 (March 2012), 1–21.