ABSTRACT

The United States established itself as the dominant supplier of civil nuclear technology in the 1960s. But Moscow soon caught up, supplanting Washington after the Cold War. What led to the rise of this autocratic nuclear marketplace? We identify two factors. First, polarity shapes the motives for states to pursue civil nuclear exports. The superpowers faced strong motivations under bipolarity, but unipolarity put greater pressure on Russia to compete for influence with nuclear exports. Second, regime type affects state capacity to execute this strategy. We find that Moscow enjoyed an autocratic advantage, which insulated its nuclear industry from domestic opposition.

In 2011, Belarus signed an agreement with Russia to build its first nuclear power plant. Moscow extended $10 billion in credit for the Russian state-owned nuclear vendor Rosatom to begin construction the following year. From an economic perspective, it made little sense to build reactors in the rural town of Astravyets, far away from the energy intensive industrial hub in central Belarus. But the location offered geopolitical value for Russia: Astravyets abutted the border with Lithuania. As Rosatom broke ground, Moscow deepened ties with Minsk and increased Russian military presence at a new base near the construction site, supplying air defence platforms and training local forces to defend the plant from attack.Footnote1 A civilian nuclear project thereby enabled Russia to extend its political influence and military presence as a bulwark against the West.

Russia’s nuclear power plant project in Belarus is but one recent illustration of how nations wield civil nuclear exports as an instrument of statecraft.Footnote2 The most dominant states in the international system often supply commercial nuclear power plants to build political relations and acquire leverage over countries.Footnote3 Nuclear projects create durable beachheads for suppliers to collect intelligence and gain influence around the world. Moreover, peaceful (as opposed to military) exports lower the risk of direct confrontation with rivals and can help counter nuclear proliferation.Footnote4

The use of civil nuclear exports to vie for influence and insight is an old nonmilitary strategy of great power competition. During the Cold War, the United States and Soviet Union established themselves as the main suppliers of nuclear technology. They used nuclear trade to bolster alliance coalitions, court nonaligned partners, and dampen ally proliferation.Footnote5 Both superpowers often acted as sheriffs of the nuclear marketplace – regulating trade and pressuring smaller supplier nations into ending the sale of sensitive nuclear technologies.Footnote6

In recent decades, however, the American position as a nuclear exporter underwent a dramatic erosion. After dominating the market in its first few decades, in the 1970s and 1980s, Washington began to fall behind the Soviet Union – not only in the export of power plants but also the provision of enriched uranium fuel, which Moscow began selling to a host of U.S. allies.Footnote7 These trends accelerated after the end of the Cold War. Of the 33 foreign-built nuclear power reactors whose construction has begun since 2000, the United States has supplied only four.Footnote8 The U.S. role in the uranium enrichment sector has continued to decline, culminating in a total exit in 2013.Footnote9 As former Secretary of Energy Daniel Poneman put it, ‘the US nuclear industry is hanging onto its global influence by a thread.’Footnote10 As the American role in the marketplace declined, authoritarian rivals of the United States stepped in to fill this space – 19 of the 33 reactors exported since 2000 came from Russia and China. Russia remains the world’s largest producer of enriched uranium.Footnote11 Emblematic of these trends, the once dominant U.S. nuclear firm Westinghouse filed for bankruptcy in 2017.Footnote12 As a Reuters story put it in 2018, Rosatom, ‘has an order book worth $134 billion and contracts to build 22 nuclear reactors in nine countries over the next decade … Westinghouse [has] not a single one.’Footnote13 What led to the rise of this autocratic nuclear marketplace?

We identify two drivers behind this dramatic shift: the international incentives for major power rivals of the lone great power to compete for influence under unipolarity; and the domestic advantages autocratic leaders enjoy in the pursuit of geostrategic nuclear exports. Variation in the global distribution of power shapes the motivations state leaders face to pursue civil nuclear exports, making it more or less attractive as a foreign policy tool. But nuclear vendors benefit from strong state support when it comes to outcompeting other suppliers. Autocratic leaders are more capable of empowering industrial vendors with sovereign resources. By contrast, democratic leaders are less capable of executing this strategy because they face greater challenges when it comes to mobilizing and sustaining support for nuclear exports.

Our framework combines these factors to generate three hypotheses. First, bipolarity is likely to create strong motives for great powers to pursue civil nuclear exports as part of a counterbalancing strategy. Second, under unipolarity, civil nuclear exports are likely to become more attractive for major power rivals to improve their respective positions against the sole great power, while the unipole should face weaker motives to pursue nuclear exports. Third, autocratic leaders are most likely to be capable of sustaining domestic political support for the nuclear industry, thereby enabling them to translate international incentives into successful civil nuclear exports. By contrast, democratic leaders are likely to be incapable of maintaining state support for nuclear vendors over time, which should make it harder to effectively compete for influence with civil nuclear exports.

We test these claims with comparative case studies of nuclear export policy in the United States and the Soviet Union/Russia. We find significant support for our theoretical framework. During bipolarity, both the United States and Soviet Union were motivated to offer nuclear exports for geopolitical purposes. However, as a democratic country, the U.S. position proved vulnerable to domestic opposition, leading the American nuclear industry to decline starting in the 1970s, despite the efforts of the executive branch. By contrast, the Soviet nuclear industry remained stable until the late 1980s, when political liberalization and the Chernobyl accident provided a one-two punch that stopped the industry’s further expansion. During the era of unipolarity, the U.S. nuclear industry further declined. In Russia, conversely, the move back toward authoritarianism and the decision to challenge U.S. hegemony resulted in massive support for the nuclear industry, allowing Russia to become the dominant supplier on the globe.

Our account of the autocratic nuclear marketplace makes three general contributions to international relationship scholarship. First, we identify the factors driving patterns of economic statecraft with civil nuclear exports. Our logic refines existing explanations about why states supply nuclear technology to better account for the decline of American dominance over the nuclear marketplace. Second, the article explores how variation in regime type affects the ability of state leaders to pursue foreign policy goals.Footnote14 Scholars of nuclear proliferation argue that some types of weak autocratic regimes are ineffective when it comes to building nuclear weapons.Footnote15 Our study finds that leaders of powerful autocratic states are better at sustaining nuclear exports than democratic leaders who face higher constraints from elites and public constituents at home. Third, this observation about autocratic advantages joins an ongoing effort to bring domestic politics into the study of economic statecraft.Footnote16 Domestic institutions affect whether and how state leaders can control industrial firms, especially in the nuclear realm. By showing how these same dynamics impact nuclear exports, our research helps to shore up the domestic foundations of effective economic statecraft.

The current concern in Washington is that the autocratic nuclear marketplace portends a dangerous future where Moscow and Beijing pursue nuclear exports with little consideration of proliferation risks. It is often argued that Russia and China impose weak safeguards and loose controls over foreign nuclear energy projects.Footnote17 If so, this could increase the odds of proliferation as these countries gain ever greater market share.

The paper explains the rise of the autocratic marketplace in three main parts. The first part presents our theory of geostrategic nuclear exports. The second part tests this theory with case studies on the evolution of nuclear export policy in the United States and the Soviet Union/Russia. We conclude by considering the policy implications of our research.

Theory

We outline our theory in four sections. The first explores the allure of civil nuclear exports as a form of statecraft. The second explains how variation in the systemic distribution of power shapes the appeal of this strategy. The third identifies the domestic mechanisms that enable autocratic suppliers to outcompete their democratic rivals. The final section deduces hypotheses about when different suppliers are most likely to implement effective nuclear export policies.

International incentives

What are the foreign policy benefits of civil nuclear exports? Expensive nuclear projects can be attractive sources of commercial revenue. But states also supply civil nuclear technology to reap geopolitical rewards. According to Matthew Fuhrmann, ‘suppliers use this type of foreign aid as a tool of economic statecraft to influence the behavior of their friends and adversaries.’Footnote18 We focus on powerful suppliers – specifically great powers and their major power rivals – because these nations stand to gain greater strategic benefits from civil nuclear exports. Smaller nations tend to focus on reaping economic rewards.Footnote19 Recent research finds that atomic assistance is especially helpful when it comes to solidifying alliance coalitions, projecting influence, and managing ally proliferation. We draw on this scholarship to specify three international incentives for great powers – and rival major powers – to pursue nuclear exports.

First, civil nuclear exports enable powerful states to bolster alliance ties and attract new partners. The high value and relative scarcity of nuclear energy technology makes it an effective means of foreign assistance. As Fuhrmann argues, peaceful atomic assistance ‘allows a supplier state to develop a closer relationship with the importing state.’Footnote20 Nuclear power plants are valuable assets for nations to acquire, both for economic and prestige reasons. Foreign technology transfers often subsidize or at least offset some of the investment costs associated with developing nuclear enterprises from scratch. Fuhrmann demonstrates that by limiting nuclear cooperation to allies and select partners, great powers send atomic aid recipients ‘a credible signal of intent to forge a strategic partnership.’Footnote21 Other scholars find civil nuclear exports are intended to improve the international reputations of great powers, who outbid each other to solidify alliances and court the allegiance of nonaligned countries.Footnote22

Second, great powers can use civil nuclear exports to collect intelligence and exert leverage. The process of building nuclear power plants opens channels to elite decision makers in the recipient nation. Before any construction begins, the supplier meets with top government officials from the recipient country to negotiate the terms – what is often referred to as a nuclear cooperation agreement. Mark Hibbs finds that these agreements grant suppliers ‘access to strategic decisionmaking in [recipient] countries concerning technology, energy, and foreign policy for decades to come.’Footnote23 Once reactors come online, suppliers remain deeply embedded in the recipient’s nuclear program and broader energy production infrastructure.

Great powers also gain influence over nations who import nuclear technology. Nuclear power plants require significant resources to get off the ground. Suppliers can offer generous financing packages to build reactors without much capital investment from the recipient. But this debt generates political leverage for the supplier.Footnote24 In exchange, recipients may be asked to offer up something else beyond the four corners of the nuclear deal – such as favourable trade deals or preferential access to transshipment points. Or the supplier can cash in this chit for a favour down the road, when it needs the recipient to undertake specific actions. The upfront investment costs of large nuclear projects make them ideally suited for this type of transactional diplomacy.

After construction, nuclear power plants require special skills and materials to operate over long time periods. The average life cycle of nuclear power plants is around forty or fifty years. During this time, reactors need fuel, continuous maintenance, and spent fuel disposal. Many countries lack the resources and expertise to manage basic atomic energy operations, let alone supply themselves with the low enriched fuel that powers most of the power reactors in service today. Regardless of whether the supplier helped finance the construction of the reactor, this often makes recipients dependent on their patron, leaving them vulnerable to coercive diplomacy.Footnote25 Suppliers can threaten to hold back critical materials or services unless the recipient complies with their demands.Footnote26 Even if coercion is not explicitly used, generous nuclear support can predispose a recipient to accommodate a supplier’s foreign policy interests.

Third, civil nuclear exports help great powers to manage proliferation and dampen potential blowback from great power adversaries. One challenge with exporting nuclear power plants is that this technology can help recipients pursue weapons ambitions. But many of the same attributes that make civil nuclear exports effective for exercising leverage also enable great powers to reap nonproliferation benefits. Scholars show that great powers use nuclear trade to gain greater insight and influence over the trajectory of nuclear energy programs, often by conditioning exports on recipient countries joining the nonproliferation regime and opening themselves up to international inspection.Footnote27

The above-board nature of civil nuclear exports also lowers the risk of direct confrontation with another great power. Some states supply sensitive nuclear technology to help the enemy of another rival acquire nuclear weapons.Footnote28 But the problem with military atomic assistance is that it is likely to draw the wrath of another great power rival. Great power suppliers can protect themselves from this blowback by using the above-board marketplace to sell nuclear plants in full compliance with international safeguards and by refraining from transferring sensitive fuel cycle facilities. The need to protect nuclear facilities from attack also creates an avenue for more direct military cooperation. Recipients may request additional force training and military hardware to defend nuclear infrastructure. This creates an opportunity for great powers to improve military cooperation with key recipients without directly targeting another rival.

In sum, civil nuclear exports help powerful nations to (1) shore up political relations with close allies and court nonaligned partners; (2) establish beachheads for projecting influence and insight abroad; and (3) lower the risks of potential blowback. Yet these alluring attributes raise the question of why some nations seem to abandon civil nuclear exports over time.

Structural pressure

What explains variation in the incentives for powerful nations to compete for influence with civil nuclear exports? In her study of the nuclear marketplace, Eliza Gheorghe argues that ‘the core motivation for nearly all vendors is to maximize market share,’ which creates a constant zero-sum competition among suppliers to win nuclear bids.Footnote29 Another strand of research suggests that great powers opt for this tool when another peer rival poses a clear threat. As Jeff Colgan and Nicholas Miller find, periods of intense competition drive great powers to outbid each other by supplying allies and partners with nuclear energy technology.Footnote30 Fuhrmann similarly observes that atomic assistance becomes attractive for powerful nations under pressure to keep alliances and foreign partnerships strong.Footnote31 But these conditions for market competition are endogenous to one larger factor: the number of great powers in the international system.Footnote32 Our framework adopts this traditional definition of polarity to compare an international system with two great powers (bipolarity) against one featuring a sole great power (unipolarity).Footnote33 As a structural variable, polarity does not determine foreign policy outcomes. Instead, we argue that it shapes the motivations of great powers and their rivals to pursue civil nuclear exports.

Bipolarity creates incentives for the two dominant states to keep their alliances strong and court the allegiance of nonaligned countries. Alliance coalitions tend to form around the duelling great powers.Footnote34 But this system puts pressure on each great power to increase the odds of success in a potential conflict by offsetting any power advantages accrued by the opposite side. The situation privileges balancing strategies – mostly internal build-ups of military force but also external enhancements to the war-fighting capacity of allies.Footnote35 On the external balancing front, great powers are likely to employ a range of options to shore up alliances and court partners, from defence commitments and military assistance to economic aid and technology transfers. Civil nuclear exports should become an attractive tool for each great power to strengthen allies, bolster bilateral relations, and manage proliferation.

Unipolarity relieves pressure on the lone great power to adopt aggressive balancing measures. In the absence of another peer rival, the unipole only faces incentives to contain weaker adversaries and hedge against the rise of major power rivals.Footnote36 Allies and potential partners are more eager to align with the unipole to harness its power for their own interests. The unipole therefore enjoys the luxury of being able to ‘pick and choose among different alliance partners,’ according to Stephen Walt.Footnote37 As a result, the unipole faces less pressure to pursue nuclear exports.

By contrast, major power rivals of the unipole face stronger motivations to adopt nonmilitary instruments of influence. Unipolarity need not drive all other lesser powers to oppose the global hegemon – it can be more advantageous to bandwagon or at least buy time with a neutral stance. But some powerful states may come to oppose the lone great power. Unipolarity drives these ‘major power rivals’ onto the horns of a dilemma. On the one hand, they confront a power gap with the unipole who can limit their freedom of action. This creates an incentive for these challengers to improve their position and constrain the unipole. On the other hand, the power imbalance means that these rivals must be wary of taking aggressive actions to make up ground. Traditional balancing options involve substantial risk for marginal reward. For instance, military build-ups risk setting off unwinnable arms races. Countervailing coalitions are difficult to form in the shadow of overwhelming power. Even modest containment efforts might spark a dangerous confrontation. In this situation, major powers are likely to find political and economic levers of statecraft an attractive way to oppose the unipole without incurring its wrath.

In sum, we claim that polarity is central to leaders’ motivations to pursue civil nuclear exports. However, in order for these motives to translate into successful export outcomes on the global market, they must make their way through the exporter’s domestic political system. Structure therefore shapes the allure of nuclear exports as a foreign policy tool, but does not automatically lead states to gain or lose relative market share.

Domestic advantages

How do powerful supplier nations translate international incentives into successful outcomes in the nuclear market? Drawing on recent research, we explore the impact of regime type on state capacity to pursue civil nuclear exports.Footnote38 Although our theory focuses on the most powerful nations in the system, who are most likely to be motivated by the geopolitical concerns outlined above, the domestic political mechanisms in this section are generalizable to any nuclear supplier state. We reveal how autocratic leaders can gain an advantage over democratic rivals who compete for influence with civil nuclear exports.

Supplier performance in the nuclear marketplace principally depends on the relationship between two key actors within the state: (1) the core leadership in charge of foreign policy and (2) the industrial vendors who build the nuclear technology abroad. Leaders are instrumental in marshalling the material and political support vendors need to pursue nuclear exports. But this level of support varies along a continuum, from wholly state-run nuclear enterprises with access to deep sovereign wealth funds at the high end to independent private firms with little sustenance from government on the low end.

Leaders who marshal high levels of state support for nuclear vendors put themselves in an optimal position to outcompete other suppliers on the market for three reasons. First, state support enables nuclear vendors to offer countries lucrative financial sweeteners during negotiations, such as interest free loans or low investment costs.Footnote39 By lowering its cost, sovereign wealth can create added demand abroad for atomic energy imports. Second, and relatedly, state subsidization of the nuclear industry helps to dampen the financial risks involved with foreign nuclear projects, especially in countries with limited capital and weak regulatory frameworks. Without state support, nuclear vendors may be less willing and able to take on many customers. Third, vendors need state support to maintain supply chains amid slumps in the demand for nuclear energy,Footnote40 which can occur for economic reasons or due to nuclear accidents or other exogenous events that reduce citizen support for nuclear power. In sum, the more support a vendor receives from state leaders, the greater its capacity to compete in the nuclear marketplace.

There are two main ways for leaders to increase support for the nuclear industry. The first is to empower vendors with greater resources and authority by mobilizing other elite actors in the state. As Elizabeth Saunders points out, the participation of bureaucratic and legislative elites ‘is often necessary to make or implement a policy change’ over large nuclear enterprises.Footnote41 These complex technological projects benefit from firm commitments from the state to sustain capital intensive construction efforts over long time periods.Footnote42 Leaders who want an agile nuclear export capacity must cultivate elites as stakeholders in this plan. Vendors can then be brought into the folds of state power through national ownership schemes or government partnerships.

The second mechanism involves activating the public to back nuclear vendors on economic or prestige grounds. Saunders notes that this domestic audience can act ‘as a constraint on leaders or be activated by elites.’Footnote43 When the public is capable of imposing costs on a leader, opposition to the nuclear industry tends to constrain the level and durability of state support. Public opposition to the nuclear industry can wax or wane in response to exogenous events, such as nuclear accidents or climate crises. Leaders who either alter public preferences or face few constraints from this audience are better able to maintain elite cohesion around the nuclear industry. Domestic audiences can also make commitments to nuclear trade deals more credible if the public can impose costs on leaders for abandoning export plans.

The institutions in autocratic regimes generally make it easier for leaders to sustain state support for nuclear vendors. In particular, Hyde and Saunders focus attention on the ‘domestic political institutions that govern the interactions between leaders, elites, and the mass public,’ which create domestic audience constraints that are often lower in autocracies.Footnote44 Autocratic leaders tend to face few costs and political challenges when it comes to mobilizing elite support and empowering state-owned nuclear vendors.Footnote45 In addition, the authoritarian nature of the system makes leaders less accountable to the mass public, thereby undercutting pressure to keep the nuclear industry profitable or responsive to constituents. As a result, autocratic institutions put leaders in an optimal position to lend high levels of durable support for nuclear vendors.

Democratic leaders, however, tend to pay higher costs and run into institutional barriers when it comes to backing the nuclear industry. The domestic institutions in democracies can constrain leaders from translating policy preferences into outcomes for two reasons. First, elite actors are independent of the core leadership circle, especially in states where private nuclear vendors pursue commercial goals outside of the government altogether.Footnote46 This feature can be advantageous for democracies when it comes to pioneering economic and technological innovation at early stages of development. However, elite independence makes it harder for democratic leaders to maintain durable support for the nuclear industry as it matures, especially if exogenous events such as accidents create political opposition to nuclear energy. Second, democratic leaders are also more responsive to public opinion. Swings in electoral preferences can introduce volatility in state support for nuclear vendors. Democracy therefore acts as a constraint on nuclear exports because it makes the nuclear industry more vulnerable to public opposition, whereas it is less vulnerable in authoritarian regimes. This disadvantage for democracies is likely to be most acute in the wake of nuclear accidents or proliferation crises that galvanize public concerns about the safety of nuclear power plants. As a result, empowerment of nuclear vendors in democracies tends to be fragile and difficult to sustain over time, hampering their ability compete internationally.Footnote47

Hypotheses

The final part of our framework combines these international and domestic factors to generate three hypotheses about the rise of the autocratic nuclear marketplace.

The first set of hypotheses focus on the relationship between polarity and the motivation for states to pursue civil nuclear exports. Great powers are more likely to face strong motives to export civil nuclear technology under bipolarity than in periods of unipolarity. Democratic and autocratic leaders should both attempt to provide allies and partners with civil nuclear exports.

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Democratic and autocratic great powers are likely to find civil nuclear exports an attractive instrument of statecraft during periods of bipolarity.

In periods of unipolarity, major power rivals are likely to be more motivated to consider civil nuclear exports to push back against the dominant great power. Civil nuclear exports should be an attractive tool for making up ground without triggering costly reactions. But the sole great power is likely to face weaker motives to pursue civil nuclear exports during the unipolar era.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Major power rivals are more likely to face stronger motives to pursue civil nuclear exports than the sole great power in periods of unipolarity.

The second set of hypotheses considers how differences in regime type shape the capacity of state leaders to translate these structural incentives into successful nuclear export outcomes. The centralization of elite actors should lower the costs of wielding state-owned enterprises to accomplish foreign policy objectives. Autocratic leaders are likely to be more capable of maintaining deep levels of government support for the nuclear industry without needing to be responsive to public opinion.

Hypothesis 3a (H3a): Authoritarian leaders are likely to be the most capable of securing and sustaining civil nuclear exports over time because state institutions enable them to support the nuclear industry at low domestic cost.

By contrast, democratic leaders are less likely to pay the high political costs associated with backing nuclear exports in the face of public opposition. Domestic institutions make it more difficult for these leaders to support the nuclear industry, as they must mobilize elite stakeholders and activate public preferences over successive electoral cycles. We therefore expect democracies to perform more poorly than autocracies once political opposition to nuclear energy emerges.

Hypothesis 3b (H3b): Democratic leaders are likely to be less capable of supporting successful civil nuclear exports because nuclear vendors are more vulnerable to political opposition over time.

Testing the theory

Our theory focuses on great powers and major power rivals, who are most likely to be motivated by geopolitical concerns.Footnote48 To test H1 and H2, we rely on a combination of primary and secondary sources to determine the motives of leaders overseeing civil nuclear export efforts. To test H3a and 3b, we primarily focus on trends over time in the export of nuclear power plants and associated materials like enriched uranium fuel supplies, as well as how domestic opposition impacts this process. We do not focus on trends in the signing of nuclear cooperation agreements (NCAs) since these provide a legal and political framework for exports but do not necessarily result in the transfer of nuclear technology or materials. We also set aside the export of research reactors – often used for scientific purposes and the production of medical isotopes – since they are far less expensive and valuable a form of assistance when compared to nuclear power plants.

To code polarity, our empirical approach considers the total number of great powers in the international system. We identify a state as a ‘great power’ if it (a) possesses the military capability to hold its own against any other powerful nation and (b) enjoys the ability to shape outcomes around the world.Footnote49 We use the term ‘major power rivals’ to denote powerful states who oppose the lone great power under unipolarity. They possess enough military force to make war costly for the great power but lack global power projection capabilities.Footnote50 This yields three international systems since the advent of civil nuclear technology in 1954: (1) the bipolar era during the Cold War with the United States and the Soviet Union as the two great powers (1945–1991); (2) the unipolar moment with the United States as the sole great power (1991–2014); (3) the transition back to a bipolar system as China started to attain the military capabilities of a great power in 2014. We treat the United States as a democracy for the entire period under study, and the Soviet Union/Russia as authoritarian until the late 1980s, democratic in the 1990s, and moving back toward authoritarianism again in the 2000s.Footnote51

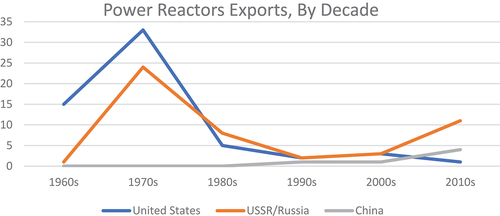

below offers a first cut at testing H3a and H3b, examining the exports of the great power nuclear suppliers from the 1960s to the present.

Overall, the trajectory is consistent with the theory. The United States dominated the export market during the early years of bipolarity but was unable to sustain its position as a democratic supplier with a private industry, entering a steep decline in the 1980s; its position declined further once unipolarity emerged. The Soviet Union managed to better weather the global decline in demand for nuclear power, overtaking the United States in the 1980s before declining during the era of political liberalization in 1990s. The Russian nuclear industry re-emerged with a vengeance after the return of authoritarian governance and the decision to challenge U.S. unipolarity in the 2000s. China, a rapidly rising authoritarian major power rival of the United States, has likewise seen its nuclear export position grow steadily for three decades as it seeks to erode U.S. hegemony.

To assess the theory’s causal mechanisms – both geopolitical and domestic – we examine the evolution of American and Soviet/Russian nuclear export policy from 1953 until 2018. We treat the Soviet Union and Russia as one longitudinal case since Russia inherited the bulk of Soviet nuclear infrastructure and expertise. We selected these two cases in order to obtain variation on our two main explanatory variables: polarity and regime type. Both cases span periods of bipolarity and unipolarity. The United States offers an example of a democratic great power with a private nuclear industry where the Soviet/Russia case provides an example of authoritarian great power with a state-run nuclear enterprise, with brief periods of political openness in the late 1980s and 1990s. Though its trajectory is consistent with the theory, we leave aside China since it only began exporting power reactors in the 1990s, so there is little variation in polarity, nor variation in regime type to explore.

If our hypotheses are correct, in the American case we should find a strong push for nuclear exports under bipolarity and a weaker commitment under unipolarity, when the U.S. position of dominance was assured. Moreover, as a democratic country with a private industry, the United States should find it more difficult to sustain its nuclear industry and exports in face of public opposition – even when strongly motivated to do so during bipolarity. In the Soviet/Russia case, we should find a strong commitment to nuclear exports – both during bipolarity and also under unipolarity once Russia becomes determined to challenge U.S. hegemony. Due to its authoritarian system, support for the nuclear industry and exports should be more stable and more likely to weaken during periods of greater political openness.

The evolution of U.S. nuclear export policy

We examine the rise and fall of American civil nuclear exports across three time periods from 1953 until 2018: (I) the initial era of close relations between Washington and the nuclear industry under bipolarity from 1953 until 1970; (II) the subsequent erosion in government support from 1970 through 1991; (III) the further decline of U.S. exports during the apogee of American power in the unipolar era from 1991 until 2018.

Atoms for international influence (1953–1970)

In the early years of the nuclear age, the U.S. government provided extensive support to the civilian nuclear industry. Consistent with Hypothesis 1, the bipolar competition with the Soviet Union was a crucial motivator for the development of the U.S. nuclear industry and exporting nuclear technology abroad.

In the first few years following the Second World War, economically competitive nuclear power was a distant goal and there was little private sector appetite for investing in this technology. The government filled this gap by funding research and development (R&D) for national security applications, as the Navy was interested in reactors that could power its vessels.Footnote52

In 1953, President Dwight Eisenhower unveiled his Atoms for Peace plan, which called for the development of peaceful nuclear technology and sharing it worldwide. Eisenhower’s objectives had everything to do with the Cold War competition. His administration hoped Atoms for Peace would counteract Soviet propaganda and improve America’s image, cement ties with U.S. allies, and attract new client states. Within a few years, the United States had signed nuclear cooperation agreements with forty countries.Footnote53 Meanwhile, the Atomic Energy Act of 1946 was amended to allow for sharing of nuclear technology and the development of commercial nuclear power domestically.Footnote54 As one of Eisenhower’s advisers put it, sharing nuclear technology abroad had the potential to ‘bind our allies closer to us and even influence certain countries presently neutral to be more positively cooperative.’Footnote55 A National Security Council report two years later warned, ‘The USSR will make maximum use of atomic energy … as political and psychological measures to gain the allegiance of the uncommitted areas of the world … If the United States fails to exploit its atomic potential … the USSR could gain an important advantage in what is becoming a critical sector of the cold war struggle.’Footnote56

The nuclear industry benefitted from having two bureaucratic advocates created by the Atomic Energy Act of 1946: the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), which oversaw both civilian and military nuclear development, and the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy (JCAE), a congressional body that oversaw legislation related to nuclear issues.Footnote57 Together, the JCAE and AEC worked to create and mobilize economic interest groups that would support the development of nuclear power.Footnote58

In its first few decades, the nuclear industry received large-scale government support. From 1950 to 1962, the government spent $28.2 billion (in 2015 USD) on R&D for nuclear reactors, and another $36.6 billion was spent from 1963 to 1975.Footnote59 Government support extended to include limits on liability for nuclear accidents, financial support for construction and waste management, and provision of fuel for power reactors at discounted rates.Footnote60 Meanwhile, the AEC and government-run Export-Import Bank facilitated nuclear exports, using artificially low fuel costs to make their offers more attractive.Footnote61 The United States gained a commanding lead over the Soviet Union in the export of power reactors. By 1970, U.S. firms had completed or begun construction on power reactors in Belgium, West Germany, Italy, India, Spain, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Japan.

The growth of the U.S. nuclear industry also benefitted from a favourable domestic environment. State and local officials were often enthusiastic about hosting nuclear reactors.Footnote62 Although there was some public uneasiness about nuclear technology, Gamson and Modigliani find that, ‘By the mid-1960s, the nuclear energy industry was enjoying a wave of new orders and no public opposition.’Footnote63 The lack of public concern about nuclear safety was in part due to a consensus among nuclear experts that their disagreements should be kept behind closed doors, so that they did not undermine support for the industry.Footnote64

Decline in government support for the nuclear industry (1970–1991)

Starting in the 1970s, expert consensus broke down and the political tide began to shift against the nuclear industry, causing Washington to lose ground in the export market. Consistent with H1, U.S. leaders continued to be strongly motivated to export for geopolitical reasons. However, domestic opposition made it more difficult for them to successfully execute this policy, as H3b would expect for a democratic country.

In 1971, environmentalists won a legal case that required the AEC to evaluate the environmental impacts of all reactors licensed since January 1970, a decision that ‘created enormous difficulties for the Commission.’Footnote65 The 1973 oil crisis brought the debate over energy policy to the fore, leading to intense arguments over nuclear power. Anti-nuclear groups mobilized, seeking to rein in the industry and disband the AEC – which they viewed as problematic due its twin roles of developing and regulating nuclear power.Footnote66

President Nixon colourfully described the precarious situation for nuclear power in a cabinet meeting in April 1973, a few months before the oil crisis made the debate even more intense:

We’re in the lead in nuclear energy in developing it. We’re the people that started it all. And now, who’s ahead in the development of nuclear power plants, in terms of actually having ‘em on stream? The Soviet Union! Even the British. Why? Why are they ahead of us? Because … of all the whole wrap of red tape that is required to get one through, and, again, our environmentalist friends.Footnote67

In 1974, the Energy Reorganization Act abolished the AEC and created the Energy Research and Development Agency (ERDA) to oversee R&D for all energy sources and established the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) to set standards for the nuclear industry. As a result, the industry lost one of its key institutional advocates and ‘support for nuclear R&D and similar activities lagged.’Footnote68 As part of the reform, the NRC was given ‘final responsibility for approving nuclear exports,’Footnote69 weakening the ability of the White House to wield nuclear trade for foreign policy objectives. Meanwhile, the United States maxed out its enriched uranium production capacity, meaning it could no longer enter into new foreign supply relationships – and Congress blocked the Ford administration’s efforts to expand capacity.Footnote70 Three years later, the JCAE was abolished as a result of Congressional concern that it was too pro-nuclear – removing another key backer of the industry.Footnote71

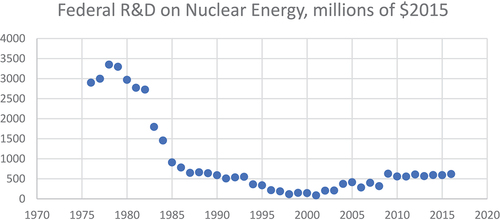

In the second half of the 1970s mobilization against the nuclear industry increased. The Three Mile Island accident of 1979 accelerated these trends, delivering a ‘death blow for the extension of nuclear power.’Footnote72 In 1974, 125 new nuclear power plants were slated to be built in the United States; this number fell to 64 by 1977 and to only 2 by 1984 – largely as a result of tightened safety standards and correspondingly higher construction costs. Those plants that were built often experienced massive delays.Footnote73 Public opinion in the United States followed a similar trajectory, shifting from majority support for expanding nuclear power to majority opposition by the early 1980s.Footnote74 At the same time, as below demonstrates, federal spending on nuclear R&D began to plummet.Footnote75

In addition to devastating the nuclear industry at home, domestic mobilization hampered America’s competitiveness as an exporter. Increasingly concerned about the dual-use problem in the wake of India’s 1974 nuclear test, Congress moved to tighten the export process. While U.S. presidents and members of the executive branch were also motivated to strengthen America’s nonproliferation policy, the evidence below makes clear that domestic pressure from Congress was crucial in shaping the form and intensity of that policy change, and that the White House resented its diminished ability to control the export process.

In 1975, Congress passed a bill that gave it the ability to reject a nuclear cooperation agreement through a joint vote of the House and Senate.Footnote76 While sharing a desire to prevent proliferation, the Ford administration worried that congressional moves would go too far, to the detriment of America’s geopolitical position. As Secretary of State Kissinger put it in testimony before the Senate, further restrictions on the export process could ‘damage our political relationships well beyond the nuclear area … cast further doubt on the credibility of U.S. supply commitments … [and] reduce the influence we are now able to bring to bear in service of our nonproliferation objectives …’ Footnote77

Tightening U.S. export restrictions was especially problematic since the United States was beginning to face stiffer competition – not just from the Soviet Union but also allies like West Germany and France, who were willing to sell sensitive fuel cycle facilities. In order to limit proliferation risks while shoring up America’s competitive position, the Ford administration spearheaded the creation of the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG), which set international standards for exports and sought restraint in the transfer of enrichment and reprocessing facilities.Footnote78

Jimmy Carter entered the White House facing the same dilemma as his predecessor – he was committed to supporting America’s nuclear industry but faced strong domestic constraints. As he put it to allied leaders in May 1977, ‘I think we are all aware of the public displeasure at the rapid turn to nuclear power … I feel that governments should depend more on nuclear power in the future for electricity … But it is hard to convince the opposition to our exports that we should maintain an export policy when they think this is going to be used for explosives.’Footnote79

The following year, responding in part to Congressional pressure, President Carter signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Act (NNPA), which required recipients of U.S. exports to accept IAEA safeguards on all their facilities and to obtain U.S. approval to reprocess any spent fuel provided by the U.S, among other conditions.Footnote80 In justifying the stricter approach to allied leaders in July 1978, President Carter emphasized, ‘Nuclear power ought to be expanded, but all of us ought to comply with rigid international safeguards … there are major domestic pressures on non-proliferation.’Footnote81 But because the United States went further to restrict exports than most of its competitors, this worked to the detriment of its market share.

By the early 1980s, the trendline was clear. The U.S. share of the free world reactor export market declined from 86% in 1970–73 to 39% between 1978 and 1980.Footnote82 West Germany beat out the U.S. to win reactor contracts in Iran and Brazil, while France began building reactors in South Africa. A 1980 General Accounting Office report could not determine the overall impact of the new export policies, but it did conclude they were a significant reason why Washington lost the Brazil and Iran contracts.Footnote83 After the tightening of U.S. export policy, efforts to sell power reactors to Israel and Egypt likewise fell through.Footnote84 Meanwhile, Carter came to resent congressional constraints. As one of his advisers put it, the result was that ‘assistance programs [were] more cumbersome and inflexible, and less effective as foreign policy instruments.’Footnote85

The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 sharpened this dilemma, as the collapse of détente increased the imperative to balance against Moscow while congressional constraints limited Carter’s manoeuvrability. After a hard-fought battle, the Carter administration narrowly gained congressional assent in late 1980 to ship enriched uranium fuel to India for its Tarapur reactor – a move they deemed essential for shoring up ties with New Delhi in the context of Soviet adventurism in the region, but which was in tension with the newly instituted NNPA. As Senator Frank Church, who supported the administration’s position, put it, the provision of fuel would help ensure, ‘the U.S. voice in New Delhi will not be drowned out by a strident, anti-American outcry … which could drive the Indian government even further away from U.S. policies’ and avoid a scenario where ‘India would turn to the Soviet Union to replace us at Tarapur.’Footnote86 By the time Carter left office, his top adviser on nonproliferation warned that U.S. policy had generated resentment among allies, who no longer thought America was a reliable supplier, and had undercut U.S. leverage in an increasingly competitive marketplace.Footnote87 Consistent with Hypothesis 3b, America’s democratic system hampered its ability to sustain its nuclear industry over time.

Reagan assumed the presidency in 1981 determined to push back against the Soviets and reinvigorate the American nuclear industry. And these objectives were closely related: administration officials believed that Carter’s policies had ‘needlessly antagonized American allies’ and that the United States needed to re-establish itself as a reliable supplier to shore up bilateral relations and maintain its nonproliferation influence.Footnote88

To help carry out this vision, the Reagan administration considered pursuing a number of reforms, including repealing the tighter export rules enacted under Carter, but congressional pushback led them to drop most of these plans,Footnote89 in part because Israel’s 1981 attack on Iraq’s Osirak reactor refocused congressional attention on nonproliferation.Footnote90 The Reagan administration nevertheless worked to resume, expand, or initiate nuclear exports to India, South Africa, Argentina, Brazil, and China – all countries deemed to be important anti-Soviet allies or countries whose attraction to Moscow could be loosened (in the case of India). Notably though, congressional constraints severely hampered what Reagan could achieve in each of these cases. In the cases of India and South Africa, the administration brokered deals for the French to supply enriched uranium fuel, thus getting around NNPA constraints that barred Washington from doing so. With Argentina, Brazil, and South Africa, the Reagan administration approved dual-use exports that the NNPA did not prohibit. Due to congressional constraints, the Reagan administration was unable to secure major new sales to any of these countries.Footnote91 Domestic constraints continued to hamper the U.S. nuclear industry, despite the geopolitical motives for supporting it.

Ceding the nuclear marketplace (1991–2018)

By the time the Soviet Union collapsed and unipolarity emerged, the U.S. nuclear industry was already in rough shape. The new geopolitical reality ensured that Washington would face few strategic incentives to revive its position in the marketplace, reinforcing the industry’s decline. Indeed, as indicates, the American nuclear industry lost even greater control over the global market after 1991, consistent with Hypothesis 2. Between 1990 and 2020, the United States exported only 6 power reactors, compared to 16 for Russia.

As above illustrates, U.S. spending on nuclear R&D likewise dramatically declined through the 1990s. The White House lost interest in civil nuclear exports. President Clinton adopted a policy of ‘benign neglect’ toward the nuclear sector, notably vetoing a bill that would have established Yucca Mountain as the future site of a nuclear waste depository.Footnote92

Starting in the mid-2000s, the government began working to restore the nuclear industry. In 2005, President George W. Bush signed the Energy Policy Act, which provided a variety of financial incentives and support.Footnote93 This policy shift was primarily driven by economic and climate considerations though, not the geopolitical desire to compete with rivals that was dominant in the Cold War.Footnote94

One area where geopolitics did enter into the equation was the decision in 2005 to negotiate a nuclear cooperation agreement with India. Because India was outside the NPT and did not have IAEA safeguards on many of its facilities, the Bush administration would need to circumvent the NNPA and gain special approval from the NSG.Footnote95 In addition to having the potential to revive the U.S. nuclear industry, Bush administration officials viewed the deal as a means of achieving closer ties with India and helping to counterbalance a rising China.Footnote96

Despite these indications that heightened geopolitical competition was influencing U.S. policy, the overall effort was limited and incoherent. Like Bush before him, President Obama committed to supporting the nuclear industry.Footnote97 As above demonstrates, federal R&D funding on nuclear technology began to tick up again in the mid-2000s, recovering from the nadir of the 1990s. But funding remained substantially lower than in the 1970s and 1980s. Though public support for nuclear power in the United States began to recover in the 1990s, it declined again in the wake of the 2011 Fukushima accident. Moreover, strict regulations, low natural gas prices, and local activism continued to hamper efforts to maintain or expand nuclear power domestically.Footnote98 In 2009, the Department of Energy declined to consider a loan guarantee for the United States Enrichment Corporation to build a new enrichment plantFootnote99; four years later, the last U.S.-owned plant was shuttered.

Moreover, U.S. nuclear export policy became even more confused. Washington supported nuclear trade with India, despite its status as a nuclear weapons possessor outside the NPT. But with a select few countries, namely the United Arab Emirates and Taiwan, the United States secured even stricter conditions than required in the NNPA – specifically that the recipient commit not to conduct any enrichment or reprocessing, the so-called ‘Gold Standard.’Footnote100 In other cases like Saudi Arabia where the United States has sought to achieve this standard, it has met stiff resistance, providing an opening for Russia or China to step in.Footnote101 Meanwhile, at the same time as Washington was promising nuclear trade with India to help balance against China, Westinghouse signed a deal to not only build four reactors in China, but also to transfer the technology underlying them,Footnote102 undercutting American advantages. Indeed, these four reactors are the only ones built by a U.S. firm abroad since 2000. Since 2010, the United States has not begun construction on a single reactor abroad. Despite intermittent efforts to revive the U.S. nuclear industry in the 2000s, then, the era of unipolarity instead saw it further lose ground.

To be clear, the United States has still engaged in international nuclear cooperation since the Cold War ended, signing more than a dozen agreements for nuclear cooperation,Footnote103 but these have rarely resulted in power reactor exports, in contrast to the U.S. record during the Cold War.

The evolution of Soviet and Russian nuclear export policy

We trace the rise of the Soviet and then Russian position in the nuclear marketplace across three time periods: (I) the Cold War era of stable government support for the nuclear industry from 1953 until 1989; (II) the decade of decline in the nuclear industry when the Soviet Union imploded and Moscow experimented with political liberalization from 1989 to 1999; (III) the ascendancy of geostrategic nuclear exports as an authoritarian regime consolidated power and leveraged state-owned nuclear vendors to challenge U.S. hegemony from 1999 through 2018.

Moscow sustains the competition for influence (1953–1989)

From the early days of the Cold War, the nuclear industry played an outsized role in the Soviet economy. Moscow was a pioneer in the development of civilian nuclear power, bringing online the first power reactor in the world and exporting dozens of power reactors to its satellite states over the ensuing decades. Consistent with Hypothesis 1, during this period of bipolarity, competition with the United States was a prime driver of its exports. In fact, it was only when Eisenhower launched the Atoms for Peace program that the Soviets got into the nuclear export game and attempted to outbid the United States for the allegiance of unaligned states by offering nuclear assistance with fewer safeguards.Footnote104 As Schmid describes, the Soviets ‘feared that Western nuclear assistance to Eastern Europe would compromise Soviet economic control, which in turn could become a threat to political unity within the bloc.Footnote105

Like in the United States, nuclear scientists in the Soviet Union secured significant financial support from the state in part by appealing to the international benefits that would accrue to Moscow by being at the forefront of the nuclear technology race.Footnote106 During the early years of the Soviet program, Moscow provided nuclear assistance to its Warsaw Pact allies, as well as China, Yugoslavia, and Egypt.Footnote107 By 1960, it had begun construction on its first two power reactors abroad, in Czechoslovakia and East Germany.

After a decade of relatively limited export activity as Moscow reassessed its policy in light of China’s use of Soviet aid to develop nuclear weapons, the Soviets again burst onto the scene, capitalizing on U.S. decline to increase its market share, even providing enriched uranium to Western European countries for their power reactors.Footnote108 Remarkably, by 1977 Moscow was providing a majority of the European Community’s enriched uranium – a market the United States had once monopolized.Footnote109 By the end of the decade, as demonstrates, the Soviet Union had significantly increased the number of reactors it exported, outpacing the United States by the 1980s.

While anti-nuclear mobilization succeeded in derailing the nuclear industry in the United States and many European democracies, no similar movement emerged in the Soviet Union, giving the government a free hand. As Dawson demonstrates, this was clearly due to differences in regime type: ‘Opportunities for opponents of nuclear power to speak out publicly, to appeal to mass audiences, and to organize resistance to the state’s official commitments to the expansion of nuclear power in the USSR were almost non-existent prior to 1985.’Footnote110 As expected by Hypothesis 3a, the Soviet state was able to continue support for the nuclear industry, facing few domestic costs for doing so.

The decade of democratic decline (1989–1999)

In the mid-1980s, the situation fundamentally changed, as Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev adopted a policy of glasnost and perestroika that allowed for greater political openness. When the catastrophic nuclear accident at Chernobyl occurred, Soviet citizens had greater impetus and ability to mobilize against nuclear power. Protest movements erupted across the Soviet republics that stopped further expansion of the industry, much like what occurred in the United States a decade prior.Footnote111 At the same time, construction on many reactors abroad was cancelled or postponed.Footnote112 Demonstrating the importance of regime characteristics, significant mobilization in Ukraine – home to Chernobyl – did not emerge until 1989, corresponding with Gorbachev’s removal of its hardline leader and decision to bring political reform to the republic.Footnote113 In line with Hypothesis 3b, as the Soviet Union became less authoritarian, it faced higher domestic costs for supporting nuclear power, leading the industry to decline.

The Russian nuclear sector was further weakened by the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the economic troubles of the 1990s.Footnote114 In an effort to revive the industry, Russia looked abroad, securing a contract to finish construction of Iran’s first nuclear power plant and to begin work on a power reactor in China.Footnote115 During the early years of unipolarity, Russia’s limited export activities were predominantly motivated by economic rather than strategic concerns, as the ministry of atomic energy (Minatom) sought to make up for the decline in state funding.Footnote116 Relations between Russia and the United States were relatively positive at the time. Washington provided assistance to Moscow to support its fledgling democracy and to help secure and dismantle elements of its nuclear weapons complex.Footnote117 Though operating in a unipolar environment, Russia had not yet decided to challenge the United States and become a major power rival.

Setting the Russian nuclear juggernaut in motion (1999–2018)

In 1999, the confluence of geopolitical and domestic changes set the stage for the revival of Russia’s nuclear industry. In March 1999, NATO launched a bombing campaign against Yugoslavia in an effort to end ethnic cleansing in Kosovo. The intervention was viewed by many Russian elites as a ‘watershed between the post-Gorbachev world and a new era of increasing Russian-Western rivalry.’Footnote118 Russian leaders began to worry more about Western intervention abroad, a concern exacerbated by the 2003 invasion of Iraq and the Colored Revolutions in former Soviet republics.Footnote119 Meanwhile, the enlargement of NATO to include Russia’s former sphere of influence, reaching Russia’s borders in 2004, further heightened Russian threat perceptions.Footnote120

Just as the dust was settling in Kosovo, Vladimir Putin assumed the presidency, determined to reassert the power of the Russian central government and reinvest in Russia’s nuclear sector, both military and civilian. Putin rejected the liberalization of his predecessor and moved to re-establish an authoritarian regime.Footnote121 Putin ultimately adopted an anti-US and anti-Western foreign policy not just for the geopolitical reasons described above but also for his own domestic and ideological purposes as well.Footnote122

It was in this environment – an increasingly authoritarian Russia determined to stand up to the United States – that Moscow began investing serious resources into reviving its nuclear industry, consistent with Hypothesis 2 and 3a. By the early 2000s, Russian nuclear officials began pushing to expand the industry and vertically integrate it. The head of Minatom believed consolidation could ensure ‘Russia’s rightful place in the global nuclear industry and the sector’s value as an instrument of diplomacy.’Footnote123

A few years later, these goals began to be realized. In December 2005, in announcing Russia’s new National Energy Strategy, Putin declared, ‘Russia has a competitive, natural and technological advantage and must become an energy superpower to retain political leadership in the world.’ That same year, former Prime Minister Sergei Kiriyenko was appointed head of the Federal Agency on Atomic Energy (Rosatom), which had replaced Minatom in 2004.’Footnote124

In 2006, the Russian government earmarked $54 billion in funding for the nuclear industry, of which $17 billion would go toward building 12 reactors abroad. The following year, Rosatom was turned into a state corporation, which would allow it ‘to act like a government agency with respect to establishing international and domestic government agreements.Footnote125 Russia’s nuclear industry was simultaneously consolidated, partly because this was deemed essential for international competitiveness.Footnote126 Russian officials outlined a goal of building 20 to 25% of all new reactors globally over the next few decades, as well as increasing their market share in nuclear fuel.Footnote127

As Putin’s statement in 2005 suggests, Russia viewed its energy resources, including its nuclear industry, as a tool of geopolitical influence. This was reiterated in Russia’s 2009 Energy Strategy, which identified as one objective, ‘to promote foreign policy positions.’Footnote128 The predominant view of scholars is that geopolitics and economics drove Russia’s nuclear export policy during this time. Stulberg shows that in the early 2000s, Russia sought to regain preferential access to the uranium mining and processing industries in Central Asia, in part to better compete on the international market, deny access to Western actors, and ‘carry the geopolitical advantage of bolstering Russia’s influence along its vulnerable southern periphery.’Footnote129 Weiss and Rumer observe that, ‘Key parts of the Russian national security establishment view civil nuclear power exports as an important tool for projecting influence overseas while creating revenue streams for sustaining intellectual and technical capabilities and vital programs inside Russia itself.’Footnote130 Others underscore that Russia used nuclear exports as a tool of ‘soft power’ to make diplomatic gains with Finland and Hungary in the wake of Western sanctions over Crimea.Footnote131 Martikainen and Vihma describe how Russian energy policy behaves according to the logic of ‘geoeconomics,’ whereby carrots and sticks are wielded to increase Moscow’s influence, including in the nuclear domain.Footnote132

Russian support for geostrategic nuclear exports began to clearly bear fruit by 2010. Since then, Russia has exported 10 power reactors, with plans for many more – surpassing the United States by a large margin. A broader statistical analysis of nuclear cooperation agreements between 2000 and 2015 found that Russia is ‘by far the largest technological supplier,’ spanning 35 recipient countries – more than double its nearest competitor.Footnote133 Consistent with Hypothesis 2 and 3a, Russia’s authoritarian system has enabled massive support for the nuclear industry, while its determination to challenge U.S. unipolarity helped provide a motive to compete abroad.

In securing these contracts, Russia has benefitted from several competitive advantages facilitated by heavy state support. First, it has the ability to offer lower prices and generous financing to its foreign customers, often in the form of large, long-term loans with low interest rates. This effort has been so successful, that it could ‘be argued that Russia played a large role in creating the market that emerged after 2005,’ making nuclear power seem affordable to developing countries like Vietnam, Turkey, and Egypt.Footnote134 In order to break into the Chinese market, Russia offered below market-rate prices.Footnote135 In the case of Hungary, Russia offered a $12 billion loan in 2017 to cover the entire cost of the Paks-2 nuclear plant, allowing Moscow to beat out competition from the United States and France. Similarly, with Finland, ‘state-backed finance … was decisive’ in securing the contract.Footnote136 For Bangladesh, Russia offered a loan covering 90% of the nuclear plant’s cost, to be paid back over 28 years at an interest rate capped at 4%. Russia beat out competitors to win a contract to build Egypt’s first nuclear power plant by offering similar terms.’Footnote137 Despite doubts about its long-term viability, this strategy succeeded in making Russia the predominant player in the nuclear market.

Russia’s second major advantage is its ability to serve as a ‘one-stop shop’ for nuclear customers due to the consolidation and comprehensiveness of its industry, allowing it to ‘effectively cater both to “nuclear newcomers” … and to established nuclear countries that require specific services.Footnote138 A third unique Russian advantage is its willingness to take back and reprocess spent fuel produced in reactors it builds overseas – something democratic suppliers are unwilling to do.Footnote139 Notably, Russia temporarily reversed this policy during its democratic turn in the 1990s before it was re-established under Putin in 2001.Footnote140 Russia is also flexible about the business models it offers customers: both a standard ‘turnkey’ approach where the recipient country takes over control and operation of the reactor, and a ‘build-own-operate’ model pioneered with Turkey, whereby Russia retains an ownership stake and commits to operate the plant itself.Footnote141

In sum, there is substantial evidence that the Russian government increased its support for the nuclear industry starting in the early 2000s as it began to chafe under U.S. unipolarity, viewed it as a tool of geopolitical influence, optimized it for export competitiveness, and succeeded in gaining a dominant position in the market by supporting the nuclear industry in a way that is more feasible in an authoritarian regime. Anti-nuclear groups in Russia have continued to mobilize under Putin – for instance they attempted to block the law allowing for the import of spent fuel – but they have been only partly and occasionally successful in affecting policy, in contrast to their impressive success under Gorbachev.Footnote142

In the appendix, we address alternative explanations for Russia’s rise relating to economic opportunism, the commercial vacuum created by U.S. decline, the changing allure of alternative forms of statecraft, and the impact of nuclear accidents.

Conclusion

In this paper, we explain when great powers are most likely to compete effectively with civil nuclear exports. Our theory accounts for the surprising demise of the United States, as well as the rise of Soviet and then Russian control over global nuclear trade. We argue that unipolarity motivated Moscow to compete for influence with nuclear exports. Autocratic Russian leaders worked closely with the state-owned nuclear industry throughout most of the atomic age, insulating it from public opposition except during a brief period of political openness. By contrast, the evolution of civil nuclear export policy in the United States shows that Washington faced less pressure to pursue this strategy under unipolarity. Even during the Cold War, democratic institutions made it difficult for U.S. leaders to sustain government support for private nuclear firms in the face of public opposition. This undercut the ability of American industry to compete for nuclear trade deals abroad – even when these exports would advance the geopolitical goals of leaders in Washington.

Our framework sheds light on recent efforts by China and the United States to compete with Russia more vigorously in the nuclear marketplace. The era of American hegemony is coming to an end. China is ascending to great power status while Russia continues to punch above its weight class. A bipolar system appears to be emerging on the horizon that pits Washington against Beijing, with Moscow looking on from the sidelines as a declining major power. According to our framework, this shift should put greater pressure on the United States and China to balance against each other with nuclear exports. But they would need to supplant Russia from its position atop the global nuclear market. We expect to see all three states push to export nuclear technology.

Over the last few years, the United States took preliminary steps to regain its share of global nuclear trade. Under the Trump administration, whose National Defense Strategy announced a shift toward great power competition with Russia and China, support for the nuclear industry and nuclear exports again received a boost.Footnote143 In February 2019, Assistant Secretary of State Ford charged Russia and China with using ‘heavily state-supported nuclear industries … to take market share from private U.S. firms.’Footnote144 The Secretary of Energy made a similar clarion call in April 2020 by unveiling a plan to shore up nuclear fuel production, develop advanced reactors, and enhance export competitiveness.Footnote145 Notably, the strategy was explicitly premised on the need to compete with Russia and China. The Trump administration also increased R&D funding for nuclear energy and lifted a longstanding government ban on financing nuclear exports, thereby paving the way for the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation to underwrite civil nuclear projects.Footnote146 The Trump administration also cut off most nuclear exports to China.Footnote147 While these or similar efforts may help revitalize American nuclear exports, our framework suggests that leaders in Washington must still surmount additional domestic barriers to make this strategy work.

China is also pursuing an aggressive plan to become a global leader in nuclear exports. Under President Xi Jinping, Beijing began using China’s extensive investment in its nuclear industry for geopolitical purposes. Chinese officials view nuclear energy exports as ‘vehicles for states to access and influence other countries’ decisionmaking on technology and energy,’ according to Mark Hibbs.Footnote148 In contrast to the United States, however, Chinese leaders are better positioned for success because they benefit from government control over state-owned nuclear enterprises, enabling them to finance risky nuclear projects abroad. As Hibbs concludes, this tight nexus between commerce and government means that ‘China’s industry is poised to invade the world’s nuclear goods markets.’Footnote149

Chinese geostrategic nuclear exports often target allies and close partners of the United States – most notably the United Kingdom and Saudi Arabia. The China General Nuclear Power Corporation (CGN) invested an ownership stake in constructing the Hinkley Point Nuclear Power Plant in the United Kingdom.Footnote150 After the British government reconsidered plans to build its fifth-generation networks with technology from the Chinese firm Huawei, China’s ambassador to the UK threatened in June 2020 to withdraw CGN support from the Hinkley Point project.Footnote151 In Saudi Arabia, the China Nuclear Engineering Corporation signed an agreement in 2016 to build a nuclear reactor and nuclear manufacturing equipment centre in Saudi Arabia.Footnote152 In the summer of 2020, allegations surfaced that Beijing helped Riyadh construct a facility for extracting uranium yellowcake from uranium ore – a step on the front end of the nuclear fuel cycle.Footnote153

Meanwhile, as Russia continues to challenge U.S. dominance, it has persisted in its efforts to dominate the nuclear marketplace, signing deals to build additional reactors in China, Turkey, Iran, Finland, and Armenia, and is in various stages of planning to build new reactors in Egypt, India, Hungary, Slovakia, and Uzbekistan.Footnote154 However, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 may curtail its ability to export civil nuclear technology, especially to Western countries.

These trends toward autocratic dominance over the nuclear marketplace have implications not only for the ability of great powers to compete with nuclear exports, but also for the future of the nonproliferation regime. To the extent that Russia and China continue to strengthen their grip on the nuclear market, they will have greater influence over the nonproliferation standards attached to nuclear transfers and will increasingly find themselves in the position of acting as nonproliferation enforcers. Whether Russia and China prioritize nonproliferation as highly as the United States traditionally has will therefore play a major role in shaping the future nuclear landscape.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (227.2 KB)Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge exceptional feedback from David Arsenaux, Eliza Gheorghe, Mark Hibbs, Vipin Narang, and conference audiences at APSA 2020. Nicholas Bartlett, Cole Srere, and James Wen provided superb research assistance. Authors listed in alphabetical order.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nicholas L. Miller

Nicholas L. Miller is an associate professor in the Department of Government at Dartmouth College.

Tristan A. Volpe

Tristan A. Volpe is an assistant professor in the Defense Analysis Department of the Naval Postgraduate School and a Nonresident Fellow in the Nuclear Policy Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. The views in this article are the authors’ own and do not reflect those of the U.S. Navy, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

Notes

1 Ivan Nechepurenko and Andrew Higgins, ‘Coming to a Country Near You: A Russian Nuclear Power Plant,’ The New York Times, 21 March 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/21/world/europe/belarus-Russia-nuclear.html.

2 The term ‘civil nuclear exports’ refers to the supply of nuclear energy assets by vendors to foreign customers for peaceful purposes. We focus on the export of commercial nuclear power plants but also examine related commodities such as fuel supply services. For an examination of a broader array of nuclear assistance, see Matthew Fuhrmann, Atomic Assistance: How Atoms for Peace’ Programs Cause Nuclear Insecurity (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2012), 13–17. On nuclear exports for military purposes, see Matthew Kroenig, Exporting the Bomb: Technology Transfer and the Spread of Nuclear Weapons (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2010).

3 Matt Bowen, ‘Why the United States Should Remain Engaged on Nuclear Power: Geopolitical and National Security Considerations,’ Columbia University, SIPA: Center on Global Energy Policy, 29 September 2020, https://www.energypolicy.columbia.edu/research/commentary/why-united-states-should-remain-engaged-nuclear-power-geopolitical-and-national-security; Mark Hibbs, ‘Does the U.S. Nuclear Industry Have a Future?’ (Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 10 August 2017), http://carnegieendowment.org/2017/08/10/does-u.s.-nuclear-industry-have-future-pub-72797.

4 Nicholas L. Miller, ‘Why Nuclear Energy Programs Rarely Lead to Proliferation,’ International Security 42/2 (2017) 40–77, https://doi.org/10.1162/ISEC_a_00293; Rebecca Davis Gibbons, ‘Supply to Deny: The Benefits of Nuclear Assistance for Nuclear Nonproliferation,’ Journal of Global Security Studies 5/2 (2020) 282–98, https://doi.org/10.1093/jogss/ogz059. But see Matthew Fuhrmann, ‘Spreading Temptation: Proliferation and Peaceful Nuclear Cooperation Agreements,’ International Security 34/1 (2009) 7–41, https://doi.org/10.1162/isec.2009.34.1.7.

5 Fuhrmann, Atomic Assistance; Alexander Lanoszka, Atomic Assurance: The Alliance Politics of Nuclear Proliferation (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2018); Jeff D. Colgan and Nicholas L. Miller, ‘Rival Hierarchies and the Origins of Nuclear Technology Sharing,’ International Studies Quarterly 63/2 (2019) 310–21, https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqz002.

6 Eliza Gheorghe, ‘Proliferation and the Logic of the Nuclear Market,’ International Security 43/4 (2019) 88–127, https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00344; Lisa Langdon Koch, ‘Frustration and Delay: The Secondary Effects of Supply-Side Proliferation Controls,’ Security Studies 28/4 (2019) 773–806, https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2019.1631383.

7 Gloria Duffy, Soviet Nuclear Energy: Domestic and International Policies (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 1979), 75; and Oleg Bukharin, ‘Understanding Russia’s Uranium Enrichment Complex,’ Science and Global Security 12/3 (2004) 200–201.

8 Data from World Nuclear Association, https://www.world-nuclear.org/.

9 Timothy Frazier, ‘The Role of Policy in Reviving and Expanding the United States’ Global Nuclear Leadership,’ Center on Global Energy Policy, March 2017, 12–13. There is one foreign-owned enrichment plant in New Mexico, run by URENCO.

10 Daniel Poneman, ‘The Case for American Nuclear Leadership,’ Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 73/1 (2017) 45.

11 See World Information Service on Energy, ‘World Nuclear Fuel Facilities,’ 29 July 2020, https://www.wise-uranium.org/efac.html#ENR.