ABSTRACT

This paper examines discriminatory attitudes of Israeli Jews towards non-Jewish immigrants admitted into Israel under the Law of Return. We looked at three spheres of discrimination: admission, political rights, and welfare rights and focused on the role of realistic socioeconomic and symbolic threats in the emergence of discriminatory attitudes. We used a mixed-methods approach that allowed to test our hypotheses among a representative sample (survey) and examine the logics underlying the respondents’ justifications for endorsing discrimination (focus groups/in-depth interviews). The findings show that discrimination endorsement is strongest in the case of admission and political rights where Israeli Jews seek to prevent the presence of outgroups and deny them the right to become part of the society. By contrast, discrimination with respect to welfare rights is less pronounced – possibly because it is not viewed as awarding membership in society, but rather providing individuals their basic needs based on universalistic or democratic values.

Introduction

Since the mid-1990s, the ethnic composition of migration flows into Israel have shifted from being predominantly Jewish to including increasing numbers of non-Jewish migrants. One group of non-Jewish migrants consists of temporary labour migrants, undocumented migrant workers, and asylum seekers from countries in Africa (Raijman Citation2020). Another group, on which we will focus, consists of immigrants not considered Jewish under halakha (Jewish law), but able to migrate to Israel under the auspices of the 1970 amendment to the Law of Return, thus creating a new oxymoronic category of “non-Jewish olim” (Lustick Citation1999).Footnote1 Specifically, we examine the social mechanisms that generate discriminatory attitudes towards this particular group.

Most research carried out in Israel on attitudes towards non-Jewish migrants has focused on the first group of labour migrants and asylum seekers. This body of work has shown that discriminatory attitudes towards this population are quite prevalent (see e.g. Gorodzeisky Citation2013; Hercowitz-Amir, Raijman, and Davidov Citation2017; Hochman Citation2015; Hochman and Hercowitz-Amir Citation2017; Raijman and Semyonov Citation2004). By contrast, research on non-Jewish migrants arriving in Israel under the Law of Return (hereafter, non-Jewish olim) has been scant, and focused mainly on the macro-institutional level (Shafir and Peled Citation2002; Shapira Citation2019; Sheleg Citation2004). The micro-level of analysis – that is, the exploration of the attitudes of the Israeli population towards non-Jewish olim – has largely been overlooked.Footnote2

This neglect is somewhat surprising, given that the non-Jewish olim in Israel embody one of the fundamental and unresolved contradictions of Zionism, or Jewish nationalism, namely, its relationship with the Jewish religion (e.g. Shenhav Citation2007). From a secular civic perspective, these immigrants are non-Arabs (e.g. Lustick Citation1999) and hence help ensure the majority of the Jewish population in the country. However, from a religious ethnic perspective, they are also not Jewish and hence are a threat that undermines the Jewish character of the state.

Narrowing this gap, in the current paper we focus on discriminatory attitudes towards non-Jewish olim. We define discrimination as a combination of openness to Jewish immigrants (olim) and a lack of such openness to non-Jewish olim. By comparing two groups of immigrants (both citizens of the State of Israel) who differ in their ethno-religious belonging, we make a theoretical contribution to the literature on ethnic exclusionism. Specifically, we seek to disentangle the role of perceived socioeconomic and national threats in the discrimination directed towards non-ethnic migrants in Israel. To accomplish this goal, we use a mixed-methods approach that combines quantitative and qualitative data. As we will show, this approach deepens our understanding of the complex nature of membership and belonging in Israeli society.

Non-Jewish olim in the ethno-national state of Israel

Israel is a country inhabited by Jews, representing the dominant majority, Arabs who represent the largest minority, and other non-Jewish outgroups (labour migrants and asylum seekers). The relationships between the Jewish majority and the non-Jewish minorities are institutionalized within a democratic regime that resembles what Smooha (Citation2002) calls an ethnic democracy model. Unlike the civic democracy model prevalent in industrialized Western societies, this model of ethnic democracy consists of a state where all citizens are granted civil rights but at the same time, members of the majority ethnic group enjoy additional privileges. The model thus implies the co-existence of two contradictory principles: civic and political rights for all citizens, and the structural subordination of the (non-Jewish) minority to the ethnic majority. As such, Israel is a democracy in which the state belongs to the majority Jewish group, which utilizes it to promote its own national interests (Smooha Citation2002).Footnote3

One example of how the Israeli state serves the interests of the majority is its immigration policy, expressed in the Law of Return of 1950. This law underpins the legal framework for granting Israeli citizenship to Jewish migrants and their children immediately upon arrival in the country. It reflects Israel's definition of Jewish newcomers as “returning ethnic immigrants” – that is, as rightful members of Israel's Jewish majority (Raijman Citation2020).Footnote4

Following a 1970 reform, the rights conferred by the Law of Return were extended to the grandchildren of Jews and to their nuclear families (even if they were not Jewish). The unintended consequences of the 1970 amendment became evident after the collapse of the former Soviet Union (FSU), when a massive wave of migrants exited the Soviet republics to settle in Israel. Between 1990 and 2018, Israel took in more than one million migrants from the former Soviet Union. Currently, immigrants from the FSU still comprise the bulk of immigration into Israel. Immigrants from Africa (mainly Ethiopia), Western Europe, and North and South America have also arrived under the auspices of the Law of Return (Raijman Citation2020).

The migration flows of the 1990s included, for the first time, a significant number of migrants not considered Jewish according to halakha, who had entered the country under the 1970 amendment to the Law of Return. The percentage of non-Jewish olim has increased over time, especially among migrants from the FSU and Ethiopia (Kravel-Tovi, Citation2012).Footnote5 According to Israel's Central Bureau of Statistics, their share increased from 1.5 per cent of the overall population in 1995 to 4.6 per cent in 2017, with the Jewish share decreasing from 80.6 per cent to 74.5 per cent (Central Bureau of Statistics Citation2018).

Although these migrants are granted citizenship immediately upon arrival and the state supports their integration in the country, as non-Jewish olim they are part of the non-Jewish minority. Therefore, they encounter noticeable disadvantages with respect to various civil rights, in comparison to Jewish olim. Issues of marriage and burial, for example, are in the hands of Orthodox religious institutions who systematically neglect the non-Jewish olim and their needs (Shafir and Peled Citation2002). Non-Jewish citizens also encounter significant difficulties when seeking the admission of their non-Jewish parents, spouses, or children still living abroad to Israel (Raijman and Pinsky Citation2011).

Most of the problems encountered by non-Jewish olim are the result of the absence of a formal constitutional separation between religion and state in Israel. Although religion plays a central role in the public sphere in many Western countries (Shenhav Citation2007, 25), “few democracies go as far as the Israeli state to accommodate religious fundamentalism in the public domain” (Bagno-Moldavski Citation2015, 515). As Kimmerling (Citation1999) observes,

The basis of belonging and the criteria for measuring the enjoyment of rights is ethnic-religious. The state is not defined as belonging to its citizens, but to the entire Jewish people. Rights within it are determined according to ethnic-national-religious belonging more than according to citizenship. (340)

To sum up, the social fabric of Israeli society underwent significant changes in the 1990s due to the ethno-religious composition of the immigration flows of the period. The presence of non-Jewish olim within the country became a fact. In the next section, we draw on existing theories of discrimination and anti-immigrant sentiment to develop hypotheses about the attitudes of Israel's Jewish majority towards these newcomers.

Theoretical background

Quillian (Citation2006) defines discrimination as differential treatment on the basis of race or ethnicity that disadvantages a social group. Discrimination is “the difference between the treatment that a target group actually receives and the treatment they would receive if they were not members of the target group but were otherwise the same” (302). Allport (Citation1954), similarly, defines discrimination as “differetial treatment that is based on ethnic categorization” (52). Discrimination is thus a crucial indicator of where members of the majority draw the line between “us” (the ingroup) and “them” (the outgroup).

Reflecting this distinction, we focus on the differential attitudes towards Jewish and non-Jewish olim (according to halakha) (hereafter ethno-religious discrimination)Footnote6 regarding two dimensions of migration policy: (1) admission to the territory of the state, and (2) entitlement to rights. The first dimension refers to what Gorodzeisky and Semyonov (Citation2009) label “exclusion from the social system” (405). The second concerns social closure inside the territorial borders, and refers to the exclusion of immigrants from the “system of rights and privileges”. These two dimensions reflect two different logics of exclusion with regard to outgroup populations. The first relates mainly to securing the national and cultural homogeneity of the state and the national identity of the majority. The second relates to preserving the rights and privileges of the dominant majority and its “group position” in the Blumer (Citation1958) sense (Gorodzeisky and Semyonov Citation2009).

In terms of the entitlement to rights, we also differentiate between welfare rights and political rights. The former refers to economic security and the right “to live the life of a civilized being according to the standards prevailing in the society” (Marshall Citation1950, 149). The latter refers to exercising political power through voting for representatives and/or running as candidates for public office. Different logics may drive the denial of welfare rights and the denial of political rights. The latter is likely to be motivated by the need to protect the national ingroup from any political influence that might threat the ingroup's position, interests, and privileges. The willingness to grant welfare rights to outgroup members may be motivated by democratic and universalistic values, because the majority regards the entitlement to such rights as independent from membership in a specific social group or state (Gorodzeisky Citation2013). We thus expect that:

H1: Endorsement of ethno-religious discrimination in admission to the country will be more widespread than endorsement of ethno-religious discrimination in rights (1a). Endorsement of ethno-religious discrimination in political rights will be more widespread than its endorsement in welfare rights (1b).

Explanations of discriminatory attitudes

Scholars have identified fear of competition and feelings of threat as the main predictors of discriminatory attitudes toward outgroup populations (Quillian Citation1995; Scheepers, Gijsberts, and Coenders Citation2002; Semyonov, Raijman, and Gorodzeisky Citation2006; Stephan and Stephan Citation2000). Increased competition over scarce material or symbolic resources is likely to create more hostility to outgroup members because they are often regarded as a threat to ingroup prerogatives. Scholars have identified two forms of threat: realistic (socioeconomic) and symbolic (cultural) (Stephan and Stephan Citation2000).

Realistic threat refers to competition on the socioeconomic level and the impact of socioeconomic factors on ethnic antagonism (Blalock Citation1967; Coenders Citation2001; Quillian Citation1995; Raijman and Semyonov Citation2004; Scheepers, Gijsberts, and Coenders Citation2002). It involves a sense of threat to the ingroup's material resources, its welfare, and its wellbeing. This threat may be actual or perceived and can refer to one's own socioeconomic position or to that of the collective (e.g. Raijman Citation2010). Based on this logic, we expect that the perception that non-Jewish olim constitute a socioeconomic threat rationalizes discriminatory attitudes towards them.

Symbolic threat is rooted in cultural preferences that emphasize the importance of national and religious identity in understanding discrimination against outgroup populations. It reflects the fear of the intrusion of values and cultural practices that might endanger the cultural, religious, and national homogeneity of a given society. Such feelings are likely to prompt antagonism against outgroup populations (Bloom, Arikan, and Courtemanche Citation2015; Fetzer Citation2000; Stephan and Stephan Citation2000).

Symbolic threat is of special importance in Israel for two reasons. First, according to Israel's strong ethno-national and religious self-definition, membership in the (Jewish) nation is a prerequisite for substantive membership in the state (citizenship) (e.g. Shafir and Peled Citation2002). Second, symbolic threat is associated with what is called the “demographic” (or “national”) threat; namely, the fear that Jews will no longer be the majority group in the country (Zureik Citation2008), or the Arab population will become the majority (Lustick Citation1999). Both explanations imply that from the majority's perspective, symbolic threat reflects a threat to the identity of Israel as a Jewish state.

Different types of threats may affect the endorsement of ethno-religious discrimination with regard to admission to the country and the entitlement to rights differently. Denial of admission is the first act of exclusion against outgroup members’ residence in the country (Gorodzeisky and Semyonov Citation2009). Raijman, Hochman, and Davidov (Citation2021) show that both socioeconomic and symbolic threats increase opposition to the admission of non-Jewish immigrants to Israel.Footnote7 We predict that symbolic threat will have a stronger effect on admission because this factor relates explicitly to securing the religious, national and cultural homogeneity of the state and the national identity of the majority.

In the case of granting rights, Gorodzeisky (Citation2013) identifies the various mechanisms prompting discrimination in social rights against non-Jewish labour migrants in Israel. Such discrimination is driven mainly by perceptions about socioeconomic threat and competition, but not by national threat, because granting social rights is not regarded as awarding membership in the collective or the state. By contrast, discrimination in granting political rights is driven by realistic and symbolic threats, as political rights are the main benefit of membership in the host society. We thus predict that:

H2: Endorsement of discrimination in admission to the country (a) and in political rights (b) will increase with increasing levels of socioeconomic and symbolic threats.

H3: Symbolic threat will have the strongest effect on the endorsement of discrimination in admission to the country.

H4: Endorsement of discrimination in welfare rights will increase with increasing levels of socioeconomic threat, but not symbolic threat.

Methodology

Data

The data we use were collected through a mixed method approach: focus groups, survey, in-depth interviews. The combination of these three sources facilitates a better and more nuanced understanding of discrimination. For the quantitative analyses, we used data collected from computer-assisted face-to-face interviews with a stratified representative random sample of the adult Israeli population.Footnote8 The total number of respondents was 1,342. However, in our analyses we focused on 663 of them, namely, Jews who were either born in Israel or immigrated to Israel prior to 1989.Footnote9 In addition to the attitudinal items, the questionnaire contained a set of socio-demographic questions. Interviews lasted about 50 minutes. The response rate was 62 per cent, high by any standard in Israeli society.

For the qualitative analyses, we used data collected in focus groups and in-depth interviews conducted among a separate sample of Jewish participants. This sample was based on specific individual characteristics that strongly correlate with discriminatory attitudes towards immigrants in Israel, namely, religiosity, political orientation, level of education, and ethnic origin. Recruitment was based on a snowball method.

We conducted three focus groups with Israeli Jews. Each group contained between 9 and 11 participants.Footnote10 One focus group consisted of students; the two other groups were made up of participants aged 25–55, of diverse religious and political orientations, as well as different educational levels and employment status. The focus group sessions lasted between 90 and 120 minutes, and were recorded and then fully transcribed. We also conducted six in-depth interviews with Jewish respondents, which lasted 90 minutes on average. First, we asked the interviewees the same questions as in the survey regarding their perceptions about socioeconomic and symbolic threats, admitting Jewish and non-Jewish olim, and granting them equal welfare and political rights. In addition, we asked them to elaborate on their specific responses to assess their own understanding of the different items included in the questionnaire. The interviews included additional questions in order to gain better insights into how the participants evaluated the consequences of the presence of migrants in Israeli society, and how these perceived consequences explained their attitudes.

Measurement of the variables in the quantitative study

We created three dependent variables to measure the endorsement of ethno-religious discrimination:

Admission to Israel. We measured this variable using two questions, formulated in the same way: “Should Jewish/non-Jewish olim (according to halakha) be allowed unlimited entry to Israel, limited entry, or should their entry be prohibited completely?” The response scales ranged from 1 (allow unlimited entry) to 5 (prohibit completely).

Entitlement to Welfare Rights. We measured this variable using two questions, formulated in the same way: “The state should ensure the welfare benefits of Jewish/non-Jewish olim (according to halakha)”. The response scales ranged from 1 (strongly agree) to 7 (strongly disagree).

Entitlement to Political Rights. We measured this variable using two questions, formulated in the same way: “All Jewish/non-Jewish olim (according to halakha) should be allowed to vote”. The response-scales ranged from 1 (strongly agree) to 7 (strongly disagree).

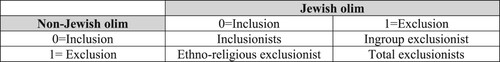

For all three dependent variables, we first recoded the original items for Jewish and non-Jewish olim into dichotomous variables. For admission, we collapsed categories 1–3 (inclusion=0) and 4–5 (exclusion=1); for discrimination in welfare and in political rights, we collapsed categories 1–5 (inclusion=0) and 6–7 (exclusion=1). We then combined the dichotomous variables for Jewish and non-Jewish olim to create three new variables indicating endorsement of ethno-religious discrimination in Admission; Entitlement to Welfare Rights; and Entitlement to Political Rights (see ).

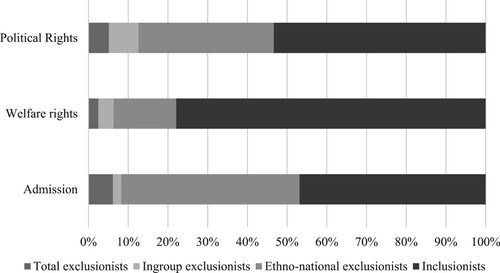

Each of these variables had four categories: (1) inclusionists – those who supported the inclusion of both Jewish and non-Jewish olim; (2) ingroup exclusionists – those who supported the exclusion of Jewish olim, and the inclusion of non-Jewish olim; (3) ethno-religious exclusionists – those who supported the exclusion of non-Jewish olim and the inclusion of Jewish olim; and (4) total exclusionists – those who supported the exclusion of all migrants (both Jewish and non-Jewish). As shows, across all three dependent variables, only a very small number of respondents belonged to the categories of total exclusionists and ingroup exclusionists. Thus, we focused only on two categories: Ethno-religious exclusionists and Inclusionists.Footnote11

Explanatory variables

We measured realistic socioeconomic threat based on responses to the questions: To what extent do (Jewish/non-Jewish) migrants arriving under the Law of Return negatively affect (1) your wage level, (2) your employment opportunities, (3) your welfare benefits, (4) your chances of buying a house? All items had a response scale ranging from 1 (not affected at all) to 7 (strongly affected) (see the descriptive statistics in Appendix A2). We conducted two exploratory factor analyses for non-Jewish and for Jewish olim, both yielding one factor (Cronbach's alpha was 0.83 and 0.90 for Jewish and non-Jewish immigrants respectively). Based on these results, we created two indexes, one for perceived threat associated with Jewish immigrants and another for perceived threat associated with non-Jewish immigrants. We then calculated a threat ratio, whereby a value larger than 1 indicated stronger feelings of threat from non-Jewish immigrants compared to Jewish immigrants.

We measured symbolic threat with an item reflecting perceptions about the threat to the Jewish majority and hence to the national identity of Israel as a Jewish state: “To what extent do you agree that in the future the proportion of non-Jewish immigrants arriving under the Law of Return would be so high that they would be a threat to the Jewish majority in the state?” (response scale ranging from 1 (agree strongly) to 4 (disagree strongly)). We recoded the scale in the opposite direction so that higher values indicated stronger threat.

We controlled for the usual socio-demographic variables in this type of study, including age (in years), gender (male vs. female), and ethnicity (Asian-African origin, European-American origin as the reference category, and Israeli). Other variables were political orientation (left, right, and centre as the reference category) and religious orientation (secular as the reference category, traditional, and ultra-Orthodox or Orthodox); education (post-secondary education, including partial and complete university degree and other post high-school studies vs. lower education – the reference category) and labour force position (employed vs. not employed – the reference category). Appendix A1 shows the distribution of these variables in the original sample.

To test our hypotheses, we estimated three logistic regression models, one for each dependent variable. We imputed data using a multi-iterative imputation method with chained (regression) equations (MICE) in Stata© (for technical details, see Raghunathan et al. Citation2001).

Findings

Quantitative analyses

In , we provide a general overview of the dependent and explanatory variables. The data reveal differences in levels of exclusion with respect to the various dimensions of immigration policy. In line with Hypotheses 1a and 1b, endorsement of ethno-religious discrimination against non-Jewish olim is more marked in admission (48 per cent) and in granting political rights (39 per cent) than in welfare rights (17 per cent). Most respondents regard the presence of non-Jewish olim as a threat to national identity and feel a stronger sense of socioeconomic threat from these individuals than they do from Jewish olim.Footnote12

Table 1. Distribution of the dependent and main independent variables (after imputation)Table Footnote1.

presents the coefficients of the three logistic regression models predicting endorsement of ethno-religious discrimination against non-Jewish olim as a function of perceived socioeconomic threat and perceived threat to national identity. In Model 1, we predict the odds of endorsing ethno-religious discrimination in admission into the country vs. the “inclusion” category. In Models 2 and 3, we predict the odds of endorsing ethno-religious discrimination in entitlement to political rights and welfare rights versus the “inclusion” category. Although the regression coefficients in the models do not convey the size of the effects in a straightforward fashion, they do shed light on whether the explanatory variables increase or decrease the respondents’ likelihood of endorsing ethno-religious discrimination rather than taking an inclusive position.

Table 2. Coefficients (SE) of the three logistic regressions (imputed data).

The data displayed in the first column of reveal that, as expected, perceptions of threat to national identity increase the likelihood of endorsing ethno-religious exclusion in admission. Likewise, respondents who reported higher levels of perceived socioeconomic threat posed by non-Jewish olim are more likely to endorse discriminatory views. Perceptions of socioeconomic threat and perceptions of threat to national identity also increase the likelihood of endorsing ethno-religious discrimination in granting political rights.

The data in indicate that the respondents’ likelihood of endorsing ethno-religious discrimination in allocating welfare rights is positively associated with increasing levels of perceived socioeconomic threat. In addition, as expected, after controlling for other relevant variables, threat to national identity does not affect the likelihood of endorsing ethno-religious discrimination in the allocation of welfare rights.

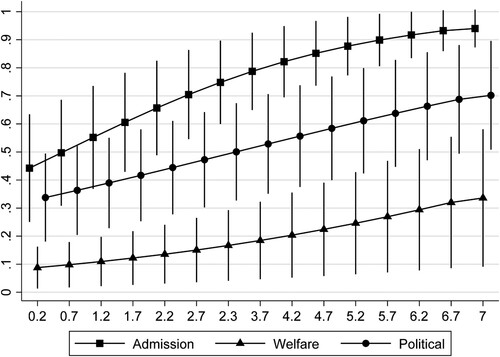

To provide a clearer interpretation of the effects of socioeconomic threat and threat to national identity, we will now present the predicted probabilities of a specific respondent profile endorsing ethno-religious discrimination in admission, welfare rights, and political rights, using predictive margins. The profile represents a male respondent, aged 42, whose parents were born in Israel, who states that he is traditional in terms of his religiosity, is employed, has a post-secondary education, and a right-wing political orientation.

shows the adjusted predictions for the three dependent variables as a function of the change in the socioeconomic threat ratio. We can clearly see that the effect of socioeconomic threat on the probability of endorsing ethno-religious discrimination with respect to admission is very strong. It increases from 44 per cent for respondents who express lower levels of socioeconomic threat from non-Jewish olim, to 94 per cent for those expressing higher levels of threat from non-Jewish olim. The effect of socioeconomic threat on the probability of endorsing discrimination in political rights is somewhat weaker, ranging from 33 per cent for respondents who express lower levels of socioeconomic threat from non-Jewish olim, to 70 per cent among respondents who feel a stronger threat from non-Jewish olim.

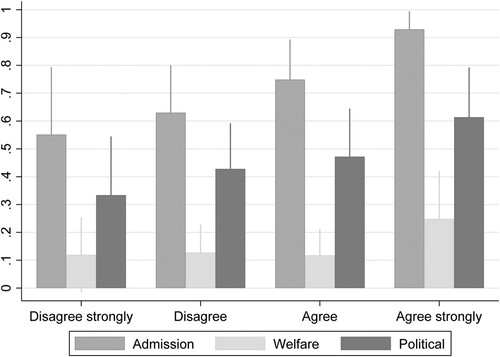

illustrates the impact of perceived threat to national identity on the predicted probabilities of endorsing discrimination against non-Jewish olim with regard to admission to Israel and entitlement to political and welfare rights. The predicted probability of a profile respondent endorsing ethno-religious discrimination against non-Jewish olim with regard to admission to Israel increases from 55 per cent for respondents who score lower on threat to national identity, to 93 per cent for respondents who score highest in this scale. For a profile respondent who disagrees with the statement that non-Jewish olim pose a threat to national identity, the predicted probability of endorsing an ethno-religious exclusionist position with regard to political rights is 34 per cent, increasing to 62 per cent for respondents who strongly agree that non-Jewish olim pose a threat to national identity. Thus, the data confirm Hypotheses 2a, 2b and 3.

Figure 4. Predicted probabilities of discrimination with 95% CIs by levels of threat to national identity.

Finally, perceptions of threat to national identity have almost no effect on endorsing discrimination against non-Jewish olim with respect to welfare rights, confirming Hypothesis 4 (see ). For a profile respondent who strongly agrees with the claim that non-Jewish olim pose a threat to national identity, there is a predicted probability of about 25 per cent that such a respondent will endorse their exclusion from welfare rights.

Summing up, our findings confirm that majority attitudes towards non-Jewish olim in Israel differ based on the various dimensions of migration policy – admission, and entitlement to welfare and political rights. These differences are rooted in different sources of threat that immigrants pose. Most Israeli Jews strongly support ethno-religious discrimination regarding admission to the country and the granting of political rights. However, there is less opposition to granting immigrants welfare rights. Socioeconomic threat is important for predicting endorsement of discrimination in the three dimensions, but its impact is more pronounced in the case of admission and political rights. The effect of threat to national identity is most prominent in the case of admission and less so in political rights. It is very weak in the case of welfare rights.

Notwithstanding the significance of these results, there are still many open questions associated with their meaning. In what follows, we present qualitative findings that can shed light on the mechanisms and logics of exclusion and inclusion in explaining these results.

Qualitative analyses

While the previous section shows the varying attitudes of the Israeli Jewish population towards Jewish and non-Jewish olim and the main factors explaining these attitudes, the qualitative analysis reveals the discursive dimension of discrimination, namely, how individuals frame and explain their attitudes towards both groups of olim. As in the quantitative analyses, we differentiated between inclusionists, those endorsing the inclusion of both Jewish and non-Jewish olim, and ethno-religious exclusionists, those discriminating against non-Jewish olim with regard to admission and rights.

Admission

The analysis of the qualitative data reveals a clear consensus concerning the admission of Jewish olim, whom both the inclusionist and ethno-religious exclusionist interviewees regard as “authentic olim” who belong to the ethnic (Jewish) majority. These ideas are expressed in the following quotations.

I think it is the best thing that can be for the Land of Israel, that the Jewish demography will win against the Arab demography. This is one of the long-term solutions for the Land of Israel, that millions of Jews will come. (A, male, right-wing, secular)

I am glad that Jews immigrate into Israel because I see it as part of the SHIVAT ZION (return to Zion), KIBUTZ GALUYOT (ingathering of the exiles) and I believe this will go in a good direction … it is a healthy process also for the State of Israel, to grow by way of receiving Jewish immigrants. (H, female, right-wing, religious)

By contrast, the attitudes towards non-Jewish olim are not uniform. As the following quotation suggests, inclusionist interviewees view the arrival of non-Jewish olim as enhancing the Jewish majority in the country.

Firstly, you do not always know who is Jewish and who is not. But there are situations in which you say on the one hand, they did fill our ranks, as they say … a group of immigrants arrived that allowed us to feel that we are a million more than we thought we were. (R, female, right-wing, secular)

They are not Jewish but their share in the population is relatively low, hardly 4 or 5 per cent. There is already a share of 20 per cent here who are not Jewish [Arab citizens], so what is there to fear from 4–5 per cent who have some attachment, and tendency to connecting with the Jewish people and that see themselves as Israelis … I would rather have 20 per cent of those, than Arabs or Muslims. (A, male, right-wing, secular)

The state belongs primarily to the Jews. When non-Jewish individuals arrive, it may harm the Jewish majority … I think the state of Israel can include citizens who are not Jewish, but it is first of all a Jewish state and this should be expressed also in some form of legal positive discrimination in realms where there is danger that the Jewish character of the state will be damaged or in issues related to promoting the Jewish perspective in the country. (H, female, right-wing, religious)

The problem [with the presence of non-Jewish immigrants] is the issue of hitbolelut and the creation of another people [non-Jews] in the land [of Israel] … . Every person that joins you affects. It affects whether the state will be more Jewish or less, whether the state will be more patriotic or less. (J, male, right-wing, religious)

They make secularism more accessible and broader, they added colors. It is legitimate, but extreme, they have crossed the line by celebrating holidays of others and eating pork—which in the country is a bit of a taboo. (Student, focus group)

… they celebrate Christmas, so you were used to not seeing decorations for Christmas in the city, now you can see shops that hold adornments for the trees … Overall, these are nice holidays, so there are Jews who also want to celebrate them. I do not want Jews to start celebrating holidays that symbolize our vulnerability. (R, female, right-wing, secular)

The qualitative data also reveal the relevance of perceived socioeconomic threat in explaining the interviewees’ positions regarding the admission of Jewish and non-Jewish olim. There is a consensus that both Jewish and non-Jewish olim pose a socioeconomic threat – especially to those individuals who compete with them for the same types of jobs. However, ethno-religious exclusionist interviewees expressed their willingness to endure these “costs”, in the case of Jewish immigrants, because Israel is the Jewish nation and therefore Jewish immigrants have a legitimate claim to entrance.

As long as they are Jewish I accept them regardless of the fact that I invest resources and even if it goes on my expenses to some extent. I see the long run and I know that just like I would like to be accepted with open arms when arriving in the country from a foreign country, I need to do the same. (Focus group participant)

Some of them are not Jewish, some of them came … to occupy Israel, and take our jobs, … some married in mixed marriages, to stay, and some got pregnant to be able to stay … they get good jobs, trick the state and receive benefits from it. It is very sad … it is necessary to check very well who comes in here. (Focus group participant)

[the non-Jewish olim] arrived here, received the SAL KLITA [absorption basket]Footnote14, took it and ran away. No. First you should show your loyalty, your will to live here, something that will provide the feeling that you did not come here to take advantage and leave, and only then you get it. (R, female, right-wing, secular)

Entitlement to rights

Possibly due to their perception of non-Jewish olim as bogus olim, ethno-religious exclusionists draw a clear line regarding the entitlement of non-Jewish and Jewish olim to social rights. Specifically, non-Jewish olim must comply with specific conditions before they can be granted equal social rights: conversion to Judaism and military service.

The solution was supposed to take place at a preliminary stage, that before they (non-Jewish olim) make aliyah, it should have been made clear to them that [there is] the need to convert to Judaism and connect to the Jewish people entirely. (A, male, right-wing, secular)

I understand military service as a benchmark for citizenship, religious or not, Jewish or not. Come, contribute to the state, fight for this country … and then see if you want to stay here. (Focus group participant)

However, military service is not the only voluntarist condition mentioned. Other conditions are integration into the labour market, and the fulfilment of all of the civic duties that the state expects of its citizens.

But if you demonstrate that you are a good citizen, work and make a living, and if you are willing to make a contribution and make it, then later, you can receive everything that a person who lives here needs. (R, female, right-wing, secular)

… You cannot say that you only deserve rights without fulfilling the civic duties according to the state's laws. All the duties you and I comply with, the law compels us to fulfil them, and it cannot be that there is one law for them and one law for others. So, for rights you need to fulfil your duties. (J, male, left-center, traditional)

I think they should have all the rights … If the state brought them (the non-Jewish olim), it should not deprive them of any right. (D, male, traditional, left-center)

I mean, if they are already here, you cannot tell them that because their grandmother is not Jewish, they cannot have … I think it is problematic to withdraw their rights once they are here. (H, female, right-wing, religious)

The right to vote should not be granted automatically. We need to wait at least five years, live here, get to know what you stand against and who you stand against, form your position. A person arrives who has no clue about anything that is happening and affects my life, because he made the wrong choice of party because someone placed the wrong envelope in his hand, and I need to suffer the consequences because a clueless person voted. (R, female, right-wing, secular)

Conclusions

In this study we investigated discriminatory attitudes towards non-Jewish olim admitted into Israel under the Law of Return. We looked specifically at three spheres of discrimination: (1) admission, (2) political rights, and (3) welfare rights. We focused on the role of perceptions about socioeconomic (realistic) and symbolic threats in the endorsement of discriminatory attitudes in these spheres.

Our findings confirm that ethno-religious discrimination is a multi-dimensional concept, highlighting the need to differentiate between attitudes towards different dimensions of migration policy. Endorsement of ethno-religious discrimination is strongest in the case of admission, where Israeli Jews (especially the religious and right-wing respondents) seek to prevent the entry of outgroups (non-Jewish) and deny them the right to become part of the society. Discriminatory attitudes are also pronounced in the case of political rights, motivated by the need to protect the majority group from any political influence that could threaten their privileges. By contrast, endorsement of ethno-religious discrimination with respect to welfare rights is less pronounced – possibly because it is not viewed as awarding membership in society, but rather providing individuals with their basic needs based on universalistic or democratic values.

The multi-dimensionality of ethno-religious discrimination in Israel echoes the still debated role of religion in Jewish-Israeli identity. Endorsement of ethno-religious discrimination in admission was stronger among religious and among right-wing Jews than among secular Jews and individuals identifying with the political centre. Data from the qualitative analysis support these findings, showing that endorsement of discrimination in admission is based on the contention that non-Jewish olim undermine the Jewish religious character of the state. Therefore, conversion is perceived by some as the ultimate step in assimilating into society.

Interestingly, we could not find religious-based differences in the likelihood of endorsing discrimination with regard to political or welfare rights in our statistical models net of national and socioeconomic threats. The qualitative findings, however, did indicate an important difference between the exclusionists and inclusionists. The former regard the non-Jewish olim as bogus Jews who took advantage of the Law of Return. Their Israeli identity, which is divorced from a Jewish religious identity, is regarded as shallow and not strong enough for them to live in Israel permanently. For this reason, exclusionists do not agree with Israel's decision to admit them under the Law of Return. Indeed, the qualitative analysis conveyed an important underlying mechanism linking ethno-religious discrimination and trust. The perceived shallow religious identification of non-Jewish olim (especially those from the FSU) increases the mistrust of their intentions of becoming long-term ingroup members. According to the exclusionists, the only way for them to demonstrate this intention is though religious conversion. From this ascriptive logic, membership is a matter of blood and Jewish ancestry.

Among the inclusionists however, there is a willingness to accept the equal treatment policy under the premise that non-Jewish olim will perform their duties and above all, serve in the military, one of the core markers of membership in Israeli society (Livio Citation2011) in exchange for receiving rights. Unlike Jewish olim, non-Jewish olim are thus required to gain the trust they lack due to their not being religiously Jewish before they can enjoy the benefits of membership in the ingroup.

The attitudes of the Jewish Israeli majority towards non-Jewish olim reflect the two incompatible but at the same time complementary “systems” that Kimmerling (Citation1999, 342) observes in Israeli society: a national-religious order and a secular-liberal one. Those supporting the national-religious order exclude the non-Jewish olim as outsiders. They make a hierarchical distinction between “wanted/legitimate” (Jewish) immigrants who deserve inclusion, and “unwanted/not legitimate” (non-Jewish) olim, who do not deserve inclusion. They oppose the equal treatment bestowed upon non-Jewish olim by the Law of Return. Instead, they support the idea that Jewish olim should enjoy a premium over non-Jewish olim.

Supporters of the secular-liberal order take a different, more pragmatic position towards non-Jewish olim, stressing primarily the obligation of the state to treat these people in a manner equal to the majority. Importantly, though, their argument is not completely devoid of nationalistic sentiment. First, they are willing to view the non-Jewish olim as equals because they serve a higher purpose, namely, securing a non-Arab majority. Second, some of them are willing to share resources with the non-Jewish olim only if they demonstrate their trustworthiness or loyalty to the country by performing their national duties, and above all, by serving in the army. On this particular point, we also see an important difference between even the more liberal side of Israeli society and other liberal societies. In Israel, liberals, too, are not willing to compromise on their nationalistic sentiment. They simply convert it from a religious to a republican mechanism according to which civic rights are connected to civic duties. This is one important issue that differentiates ethno-national states like Israel from liberal democracies in Western countries.

Acknowledgments

Authors wish to thank Michael Braun and Noah Lewin-Epstein, as well as the anonymous reviewer for their useful and constructive remarks.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The Hebrew word olim refers to Jewish immigrants, derived from the Hebrew word Aliyah, literally “ascent”.

2 For an exception, see Canetti-Nissim, Ariely, and Halperin (Citation2008), who compared the attitudes of Jewish Israelis towards Palestinian citizens of the country and non-Jewish immigrants arriving under the Law of Return.

3 We want to point out that Jews as a majority group are not a homogeneous but rather a heterogeneous group in terms of ethnicity, levels of religiosity, and political orientation. Yet, when it comes to the issue of national identity, most of the Jewish majority defines it based on “values, symbols, and collective memories most of which are anchored in the Jewish religion” (see Kimmerling Citation1999, 340).

4 According to halakha, a Jew is a person who was born of a Jewish mother or has converted to Judaism and is not a member of another religion.

5 High rates of intermarriage account for the large number of non-Jewish olim from the FSU (see Remennick Citation2007). Non-Jewish olim from Ethiopia are the Falas-Mura descendants of Ethiopian Jews who converted to Christianity. They are allowed to immigrate to Israel under the framework of the Entry into Israel Law, and are defined as olim by the state after arrival (Shapira Citation2019, 13).

6 Given that the halakha determines the difference between Jewish and non-Jewish olim, the basis for discrimination against the latter is based on ethno-religious criteria.

7 The paper relies on the European Social Survey that does not include data regarding attitudes towards non-Jewish migrants arriving under the Law of Return.

8 The study was conducted in 2008 by the B.I. and Lucille Cohen Institute for Public Opinion Research at Tel Aviv University.

9 Respondents who immigrated to Israel after 1989 were not included in our analysis, because they were not asked about their attitudes towards olim. Non-Jewish respondents were also excluded from the analysis.

10 The total number of participants was 29 (17 women and 12 men).

11 For the categorization we followed Gorodzeisky and Semyonov (Citation2009), who examined attitudes towards immigrants in Europe. They differentiated between three categories: total exclusionists – who supported the exclusion of both ethnic and non-ethnic migrants; racial exclusionists – who supported the inclusion of ethnic migrants, but object to the inclusion of non-ethnic migrants; and pro-admission – who supported the inclusion of both ethnic and non-ethnic migrants. Unlike the countries in Europe, where on average a third of the respondents were total exclusionist, in our data this category was very small (5.7 per cent in the admission category). The reason is that Jewish migration is the raison d'être of the Israeli state – the ingathering of the exiles.

12 Here, values less than 1 indicate stronger threats from Jewish olim, and values greater than 1, stronger threats from non-Jewish olim. A value of 1 implies that respondents feel equally threatened by both groups.

13 Given that Israel is viewed as the homeland of the Jewish people, there is a general tendency to view Jewish olim as migrating to Israel mainly for ideological reasons.

14 Olim arriving in Israel receive an “absorption basket” that includes various programmes to support their integration during their first year after arrival (see https://www.gov.il/he/Departments/General/absorption_basket).

15 This position reflects our quantitative findings (), which show that the share of respondents who exclude both Jewish and non-Jewish olim is larger for political rights than it is for welfare rights (13 per cent and 6 per cent respectively).

References

- Allport, G. W. 1954. The Nature of Prejudice (25th Anniversary Edition). New York, NY: BASIC Books.

- Bagno-Moldavski, O. 2015. “The Effect of Religiosity on Political Attitudes in Israel.” Politics and Religion 8 (3): 514–543.

- Blalock, H. M., Jr. 1967. Toward a Theory of Minority-Group Relations. New York: Wiley.

- Bloom, P. B. N., G. Arikan, and M. Courtemanche. 2015. “Religious Social Identity, Religious Belief, and Anti-Immigration Sentiment.” American Political Science Review 109 (2): 203–221.

- Blumer, H. 1958. “Race Prejudice as a Sense of Group Position.” The Pacific Sociological Review 1: 3–7.

- Canetti-Nissim, D., G. Ariely, and E. Halperin. 2008. “Life, Pocketbook, or Culture: The Role of Perceived Security Threats in Promoting Exclusionist Political Attitudes toward Minorities in Israel.” Political Research Quarterly 61 (1): 90–103.

- Central Bureau of Statistics. 2018. Population – Statistical Yearbook for Israel 2018 – No. 69, Population, by Population Group. Available online.

- Coenders, M. T. A. 2001. Nationalistic Attitudes and Ethnic Exclusionism in a Comparative Perspective: An Empirical Study of Attitudes toward the Country and Ethnic Immigrants in 22 Countries. Vol. 78. Neijmegen: Radboud University Nijmegen.

- Fetzer, J. S. 2000. Public Attitudes toward Immigration in the United States, France, and Germany. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Gorodzeisky, A. 2013. “Does the Type of Rights Matter? Comparison of Attitudes toward the Allocation of Political versus Social Rights to Labour Migrants in Israel.” European Sociological Review 29 (3): 630–641.

- Gorodzeisky, A., and M. Semyonov. 2009. “Terms of Exclusion: Public Views towards Admission and Allocation of Rights to Immigrants in European Countries.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 32 (3): 401–423.

- Hercowitz-Amir, A., R. Raijman, and E. Davidov. 2017. “Host or Hostile? Attitudes towards Asylum Seekers in Israel and in Denmark.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 58 (5): 416–439.

- Hochman, O. 2015. “Infiltrators or Asylum Seekers? Framing and Attitudes toward Asylum Seekers in Israel.” Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 13 (4): 358–378.

- Hochman, O., and A. Hercowitz-Amir. 2017. “(Dis)Agreement with the Implementation of Humanitarian Policy Measures Towards Asylum Seekers in Israel: Does the Frame Matter?” Journal of International Migration and Integration 18 (3): 897–916.

- Kimmerling, B. 1999. “Religion, Nationalism, and Democracy in Israel.” Constellations (oxford, England) 6 (3): 339–363.

- Kravel-Tovi, Michal. 2012. “‘National Mission’: Biopolitics, Non-Jewish Immigration and Jewish Conversion Policy in Contemporary Israel.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 35 (4): 737–756.

- Livio, O. 2011. “The Right to Represent: Negotiating the Meaning of Military Service in Israel.” Phd diss.

- Lustick, I. 1999. “Israel as a Non-Arab State: The Political Implication of Mass Immigration of Non-Jews.” Middle East Journal 53: 417–433.

- Marshall, T. H. 1950. Citizenship and Social Class. Cambridge: CUP.

- Quillian, L. 1995. “Prejudice as a Response to Perceived Group Threat: Population Composition and Anti-Immigrant and Racial Prejudice in Europe.” American Sociological Review 60: 586–611.

- Quillian, L. 2006. “New Approaches to Understanding Racial Prejudice and Discrimination.” Annual Review of Sociology 32: 299–328.

- Raghunathan, T. E., J. M. Lepkowski, J. Van Hoewyk, and P. Solenberger. 2001. “A Multivariate Technique for Multiply Imputing Missing Values Using a Sequence of Regression Models.” Survey Methodology 27 (1): 85–96.

- Raijman, R. 2010. “Citizenship Status, Ethno-National Origin and Entitlement to Rights: Majority Attitudes Towards Minorities and Immigrants in Israel.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 36 (1): 87–106.

- Raijman, R. 2020. A Warm Welcome for Some: Israel Embraces Immigration of Jewish Diaspora, Sharply Restricts Labor Migrants and Asylum Seekers. Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/israel-law-of-return-asylum-labor-migration.

- Raijman, R., O. Hochman, and E. Davidov. 2021. “Ethnic Majority Attitudes toward Jewish and Non-Jewish Migrants in Israel: The Role of Perceptions of Threat, Collective Vulnerability, and Human Values.” Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 19 (4): 407–421.

- Raijman, R., and J. Pinsky. 2011. “‘Non-Jewish and Christian’: Perceived Discrimination and Social Distance among FSU Migrants in Israel.” Israel Affairs 17 (1): 125–141.

- Raijman, R., and M. Semyonov. 2004. “Perceived Threat and Exclusionary Attitudes towards Foreign Workers in Israel.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 27 (5): 780–799.

- Remennick, L. 2007. Russian Jews on Three Continents. Identity, Integration and Conflict. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

- Scheepers, P., M. Gijsberts, and M. Coenders. 2002. “Ethnic Exclusionism in European Countries. Public Opposition to Civil Rights for Legal Migrants as a Response to Perceived Ethnic Threat.” European Sociological Review 18 (1): 17–34.

- Semyonov, M., R. Raijman, and A. Gorodzeisky. 2006. “The Rise of Anti-Foreigner Sentiment in European Societies, 1988-2000.” American Sociological Review 71 (3): 426–449.

- Shafir, G., and Y. Peled. 2002. Being Israeli. The Dynamics of Multiple Citizenship. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Shapira, Assaf. 2019. “Israel’s Citizenship Policy since the 1990s—New Challenges, (Mostly) Old Solutions.” British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 46 (4): 602–621.

- Sheleg, Y. 2004. Jewish Not According to the Halacha: On the Issue of Non-Jewish Olim in Israel. Jerusalem: The Israeli Institute for Democracy (Hebrew).

- Shenhav, Y. 2007. “Modernity and the Hybridization of Nationalism and Religion: Zionism and the Jews of the Middle East as a Heuristic Case.” Theory and Society 36 (1): 1–30.

- Smooha, S. 2002. “The Model of Ethnic Democracy: Israel as a Jewish and Democratic State.” Nations and Nationalism 8 (4): 475–503.

- Stephan, W. S., and C. W. Stephan. 2000. “An Integrated Threat Theory of Prejudice.” In Reducing Prejudice and Discrimination, edited by Stuart Oskmap, 23–46. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers.

- Zureik, E. 2008. “Comments on the Demographic Discourse in Israel.” In Migration, Fertility and Identity in Israel, edited by Y. Yonah, and A. Kemp, 39–55. Jerusalem: Van Leer Institute and HaKibbutz Hameuchad Publishing House.

Appendix

Table A1. Control variables (not imputed).

Table A2. Items measuring socioeconomic threat and the dependent variables (not imputed).

Table A3. Distribution of Meaningful variables for the analysis (imputed data).