ABSTRACT

Considering the current political relevance of anti-immigration sentiments, we examined preference to avoid interacting with immigrants – conceptualized here as a manifestation of xenophobia – among radical (Sweden Democrats, Sverigedemokraterna, N = 2216) and mainstream (Conservative Party, Moderaterna, N = 634) right-wing voters in Sweden. Correlates of xenophobia did not differ between the voter groups or compared to other populations in previous research, suggesting that increased societal focus on immigration has not altered the correlation patterns. Intended Sweden Democrat (vs. Conservative Party) voting correlated with Right-Wing Authoritarianism, institutional distrust, less right-leaning socioeconomic attitudes (in both low- and high-xenophobia subgroups), sexist attitudes (low-xenophobia subgroup), male gender and younger age (high-xenophobia subgroup). In both voter groups, respondents with higher xenophobia expressed on average more sympathy for the Sweden Democrats, perhaps indicating a larger potential voter base. We discuss the interplay of xenophobia and contemporary voting behaviours, and the concept of xenophobia in relation to anti-immigration attitudes.

Ethnonationalism and opposition to immigration are increasingly influencing party politics and voting behaviour in the Western world. New radical right-wing parties have emerged and become established over the past three decades, and several mainstream parties have toughened their approach to immigration and multiculturalism in an effort to challenge the growth of the radical right (Mudde Citation2019). These political changes do not seem to be caused by increased anti-immigration sentiments, but rather reflect a shift in the political salience of the immigration issue at the expense of economic issues that used to guide voting behaviour during the postwar period (Mudde Citation2010; Rydgren and van der Meiden Citation2019). Yet, it has been suggested that the presence of a successful anti-immigration party may contribute to politicizing the immigration issue, shaping their voters’ anti-immigration attitudes, as well as legitimizing and normalizing expressions of xenophobia in society (Harteveld, Kokkonen, and Dahlberg Citation2017; Rydgren Citation2003; Wodak Citation2015).

Given their current political relevance, anti-immigration attitudes have been commonly addressed in research. These attitudes are related to, but conceptually distinct from, antipathies toward immigrants. People may oppose immigration as a societal phenomenon, and these views do not necessarily involve harbouring antipathy toward individual immigrants (see e.g. Rydgren Citation2008). Thus, to shed light more specifically on anti-immigrant attitudes, we will examine preference to avoid interacting with immigrants, which we conceptualize as an explicit manifestation of xenophobia.

Research on voter behaviour and opinions commonly relies on existing datasets that have multiple strengths but can have shortcomings if the focus is on analyzing specific voter groups because only relatively small subsets of the sample represent these groups. The present study was particularly designed to investigate the new patterns in the political landscapes by focusing on selected voter groups. Consequently, we will be able to conduct well-powered analyses among voters of two right-wing parties in Sweden: a radical right-wing party (the Sweden Democrats) that has a pronounced anti-immigration agenda as their core issue, and a mainstream right-wing party (Conservative Party, Moderaterna) that emphasizes classical socioeconomic questions while being less invested in the immigration issue. More specifically, we aim to examine (1) the conceptual overlap and distinct aspects of anti-immigration attitudes and xenophobia, (2) correlates of xenophobia in the two included voter groups and (3) the effects of xenophobia on radical right-wing party support.

The Swedish context

The present study was conducted in Sweden, which is a socially progressive country where liberal and egalitarian norms are so commonly endorsed that they have come to be seen central to the national identity (Moffitt Citation2017; Towns, Karlsson, and Eyre Citation2014). Sweden has a long history of immigration, and the proportion of people with foreign background in 2018 was 24.9 (including both first- and second-generation immigrants: SCB Citationn.d.). People in Sweden have more positive views on immigration and immigrants compared to almost all other European countries (Bohman Citation2018; Van der Linden et al. Citation2017), but the discussion has become politized and immigration is an increasingly important political issue (Rydgren and van der Meiden Citation2019). Moreover, there are signs of a trend change in immigration sentiments, and the suggestion of receiving less refugees has become more popular (SOM Institute Citation2020).

As a liberal-conservative party, the Conservative Party has traditionally tried to combine market liberalism with relative sociocultural conservatism. Over the past decades, however, the party has emphasized socioeconomic issues while being less engaged in sociocultural questions, and the years between 2006 and 2014 marked a change toward more liberal positions on sociocultural issues – maybe most notably regarding immigration and national defense. A process that may also have distanced some of the more far-right voters from the Conservative Party was the formation of the political coalition between the centre-right parties: The AllianceFootnote1 (Rydgren and van der Meiden Citation2019) that was dissolved after the 2018 election but was still relevant at the time of the present study. To succeed in collaborations, the involved parties developed common policy statements and proposals that required compromises and pulled them closer to each other.

Due to these circumstances, voters who desired strong stances on immigration may not have found any obvious voting option among the mainstream parties. The Sweden Democrats was founded in 1988 but was an unattractive option for many due to its fascist past (Rydgren Citation2002). Since the mid-2000s, the Sweden Democrats strengthened their strivings to gain a more legitimate position in Swedish politics. Although there are indicators that at least some of their actions toward this aim were largely cosmetic, such as their “zero tolerance for racism”Footnote2 (Widfeldt Citation2015), these actions nonetheless likely helped destigmatizing the party in the eyes of many voters. In part due to this legitimization process, and the politization of the immigration issue (Rydgren and van der Meiden Citation2019), Sweden Democrats entered the national parliament (Riksdag) in 2010 (5.7 per cent of the votes) and rapidly grew into one of the largest parties in the country in the 2014 and 2018 elections (12.9 per cent/17.5 per cent of the votes).

Anti-immigration and anti-immigrant sentiments

Anti-immigration attitudes have been the most consistent predictor of radical-right support (Ivarsflaten Citation2008; Rooduijn Citation2018; but see Stockemer, Halikiopoulou, and Vlandas Citation2020), and there is therefore plenty of research focusing on a general immigration scepticism (a desire to decrease or stop immigration to one’s country) or on some of the more specific negative perceptions of immigration as a societal phenomenon (e.g. anticipated weakening of the native culture or increased criminality). However, these attitudes do not necessarily reflect antipathies toward immigrants (Rydgren Citation2008), which are also relevant to study in the contemporary European political context.

Indeed, the core ideology of the European radical right-wing party family is ethnonationalism (or nativism), which consists of a desire for a homogeneous nation-state exclusively inhabited by natives, as well as a nostalgic emphasis on ancestral values and shared culture (Mudde Citation2007; Rooduijn et al. Citation2019; Rydgren Citation2007). From the ethnonationalist viewpoint, all immigrant groups could thus be potentially harmful because nonnative elements pose a threat to the homogeneous nation-state. Hence, to increase understanding of attitudes toward immigrants, we focus on xenophobia which signifies feelings of fear, discomfort or hostility when being in contact with people from foreign groups, and a belief and desire that different groups of people should live separately (Rydgren Citation2003; Merriam-Webster Citationn.d.). Xenophobia can be considered as a form of cultural racism as it includes a perception that cultural background determines personal characteristics and determines if people can live with each other (Mulinari and Neergaard Citation2014).

However, we acknowledge the overlap between our key concepts. For example, xenophobia likely entails opposition to immigration, but we argue that anti-immigration attitudes can target mainly some categories of immigration, or immigration as a general societal phenomenon, meaning that these attitudes are not necessarily based on xenophobia (see also Rydgren Citation2008; Bohman Citation2018; Theorin and Strömbäck Citation2020). Complicating conceptual distinctions, however, the contemporary discourses depicting immigration as a problematic societal phenomenon may serve the same function as expressions of blatant xenophobia and racism (Augoustinos and Every Citation2007; Betz and Johnson Citation2004). Even when holding deeply rooted antipathies toward immigrants or ethnic minorities, individuals commonly aim at hiding and denying this because such sentiments are considered irrational and undesirable in liberal democracies, and the social norms of tolerance prohibit expressing them (Ivarsflaten, Blinder, and Ford Citation2010; Van Dijk Citation1992). But if this is the case, it seems even more important to investigate direct expressions of xenophobia, which are thus more extreme and nonnormative as compared to immigration scepticism.

Right-wing support and xenophobia

When compared to their left-leaning counterparts, people on the right-wing side of the political spectrum more commonly hold negative attitudes toward immigrants, and these attitudes are more pronounced among radical right-wing voters than among mainstream right-wing voters (Cutts, Ford, and Goodwin Citation2011; Jost et al. Citation2003; Van Assche et al. Citation2019). This corresponds well with ethnonationalism (or nativism) which is, as discussed above, the core ideology of the radical right (Mudde Citation2007; Rydgren Citation2007).

However, like people in general (Van Dijk Citation1992), radical right-wing parties tend to deny being racist or xenophobic (Hatakka, Niemi, and Välimäki Citation2017; Wodak Citation2015; see also Blinder, Ford, and Ivarsflaten Citation2013; Mulinari and Neergaard Citation2014), and their support has indeed been connected more strongly with attitudes toward immigration than towards immigrants (Rydgren Citation2008). At the same time, these parties habitually express strong antipathies toward certain immigrant groups and ethnic minorities – particularly Muslims – and depict them as dangers to their country (Hatakka, Niemi, and Välimäki Citation2017; Stavrakakis et al. Citation2017). Thus, it seems easy to see why voters with high levels of xenophobia might support these parties. However, it is unclear what explains the appeal of the radical right among voters with low levels of xenophobia, and – equally importantly – what factors hinder the xenophobic mainstream-right voters from moving to the more radical right-wing option. Highlighting a need for further study variations within voter groups, a recent study did not find anti-immigration attitudes to be a necessary condition for voting for the far-right parties in Europe (Stockemer, Halikiopoulou, and Vlandas Citation2020).

Attitudes and personality dispositions related to xenophobia and right-wing support

Generalized prejudice and conservative ideology

Negative attitudes toward immigrants and ethnic minorities correlate with other forms of group-based resentment, such as sexism and homophobia, and this tendency is called generalized prejudice (Allport Citation1954; Ekehammar et al. Citation2004). Negative intergroup attitudes correlate with endorsement of two types of ideological attitudes (e.g. Sibley and Duckitt Citation2008; Ekehammar et al. Citation2004; Hellmer, Stenson, and Jylhä Citation2018). The first of these, Right-Wing Authoritarianism, is an attitudinal cluster including conventionalism, readiness to support and submit to authorities, and authoritarian aggression toward deviants and outgroups (Altemeyer Citation1981), and is linked to a perception of the world as a dangerous place where traditions and strong leadership are essential for societal security and stability (Duckitt Citation2001). Authoritarian attitudes correlate negatively with the Five-Factor personality trait Openness (Ekehammar et al. Citation2004), meaning that they are more common among individuals who do not prefer new experiences and ideas, or aesthetic and imaginary ventures (McCrae and Costa Citation2008). The second attitudinal concept, Social Dominance Orientation, refers to acceptance and promotion of hierarchical and dominant relations between social groups (Pratto et al. Citation1994), and is associated with a competitive worldview where it is natural and legitimate that some groups are at the bottom (Duckitt Citation2001). Social Dominance Orientation correlates negatively with the Five-Factor trait Agreeableness (Ekehammar et al. Citation2004), which is a personality trait characterized by kindness, empathy, helpfulness and a general concern for social harmony (McCrae and Costa Citation2008). Low levels of Openness and Agreeableness predict negative intergroup attitudes, but these correlations tend to vanish when Right-Wing Authoritarianism and Social Dominance Orientation, respectively, are controlled for. This reflects mediation effects whereby ideological attitudes mediate the effects of personality traits (Ekehammar et al. Citation2004; Sibley and Duckitt Citation2008).

As for voting behaviour, Right-Wing Authoritarianism and Social Dominance Orientation are often referred to as right-wing or conservative attitudes because they are more commonly expressed by right-leaning and politically conservative individuals in Western countries (e.g. Ho et al. Citation2015; Jost et al. Citation2003; Wilson and Sibley Citation2013). It is also noteworthy that the political agenda of the radical right is strongly characterized by these views, as illustrated for example in their endorsement of conventional values, promotion of issues of law and order, and opposition to affirmative action (Erlingsson, Vernby, and Öhrvall Citation2014; Jungar and Jupskås Citation2014; Oscarsson and Holmberg Citation2013). Regarding voters’ attitudes, Social Dominance Orientation predicts radical-right voting (Aichholzer and Zandonella Citation2016; Van Assche et al. Citation2019), but research results have been inconclusive regarding Right-Wing Authoritarianism: studies have shown positive, non-significant, or even negative correlations (Cornelis and Van Hiel Citation2015; Dunn Citation2015). Given their inclination to support the status quo, authoritarian individuals could be open to support a radical-right party only if they consider that immigration seriously threatens society and that the party is norm-congruent rather than radical (Dunn Citation2015). Threat-based anti-immigration discourse has been receiving increasing attention in Sweden (Elgenius and Rydgren Citation2017; Strömbäck Citation2018), which may have enabled the Sweden Democrats mobilize authoritarian voters in this cultural context (see also Jylhä, Rydgren, and Strimling Citation2019a; Oskarson and Demker Citation2015). As immigration can be seen as a societal threat without holding deep-seated antipathies toward immigrants, it seems possible that authoritarianism correlates with radical right-wing support regardless of the levels of xenophobia.

Distrust and relationship with society

Negative attitudes toward immigrants have been linked to low interpersonal and institutional trust (Halapuu et al. Citation2013; Van der Linden et al. Citation2017). These relationships could be bidirectional: distrust and cynicism about human nature and societal institutions likely include distrusting in foreign people, but anti-immigration views can also lead to distrust of governments in cultural contexts with welcoming immigration policies (Citrin, Levy, and Wright Citation2014). Also, due to the general societal shift toward more liberal and pluralistic values, ethnonationalist individuals may feel excluded by politicians and society (Inglehart and Norris Citation2017). Accordingly, we will investigate the links between xenophobia, institutional distrust and experienced relationship with the society.

Right-leaning people tend to have a more distrusting view of human nature than left-leaning people, as illustrated in their higher average scores in Social Dominance Orientation (including the competitive-jungle worldview) and Right-Wing Authoritarianism (including the dangerous-world worldview) discussed above (Duckitt Citation2001). These tendencies are particularly pronounced among far-right parties and voters, who tend to hold both anti-immigration attitudes and institutional distrust (Mudde Citation2007; Rydgren Citation2007). Radical right-wing parties may be an attractive option for voters who are generally distrustful and disagreeable, or who feel they are being distanced from the society, and who are therefore drawn to a populist rhetoric (Bakker, Schumacher, and Rooduijn Citation2021; Van Assche et al. Citation2019). Also, this causality can go in the opposite direction: Radical right-wing voters are exposed to the anti-establishment messages from the politicians they support (Rooduijn et al. Citation2017) and they may also identify as societal underdogs who are being stigmatized in society (Hellström and Nilsson Citation2010).

It should be noted that radical right-wing parties are not primarily populist: their policy solutions are mainly connected to pursuit of the national preference (Halikiopoulou and Vlandas Citation2019) and their anti-establishment rhetoric is not promoting a populist agenda per se but is used more selectively to gain support for their ethnonationalist agenda or as an “amplifier” of their anti-immigrant message (Stavrakakis et al. Citation2017; Rydgren Citation2017). Nevertheless, populist rhetoric has likely been an important contributor to the success of these parties in multicultural contexts where ethnonationalist voters have been dissatisfied with the mainstream parties’ approach to internationalization (Citrin, Levy, and Wright Citation2014), which they may feel is depriving them or the social (native) group they belong to (Mols and Jetten Citation2016; Urbanska and Guimond Citation2019).

It also seems plausible that, based on these rhetorical means, the radical right has succeeded in attracting voters who are not particularly xenophobic or ethnonationalist, but who feel worried about the recent societal developments. By using scapegoating rhetoric these parties have evoked a sense that internationalization is to blame for the changes in their nation that some experience as undesirable (Mols and Jetten Citation2016; Zaslove Citation2004). Indeed, radical right-wing support has been linked to both political distrust/cynicism and negative views on immigration (Oscarsson and Holmberg Citation2013; Van Assche et al. Citation2019; but see Rooduijn Citation2018).

Summary and aims

The present research explored xenophobia among voters of a radical right-wing party (Sweden Democrats) and a mainstream right-wing party (Conservative Party) in Sweden.

As our first aim, we examined the overlap between our measures for xenophobia and anti-immigration attitudes. The goal of these analyses was to firstly ensure that our measure for xenophobia captures attitudes that are distinct from the societal perceptions of immigration, and secondly to inform future research designs that focus on perceptions of immigration.

The second aim was to study the correlates of xenophobia in both voter groups. Much is known about the correlates of negative intergroup attitudes in the public in general (e.g. Sibley and Duckitt Citation2008). However, to our knowledge, no research has investigated if these correlations are also observed among voters who support an anti-immigration radical right-wing party. As these parties may shape their voters views (Harteveld, Kokkonen, and Dahlberg Citation2017) and legitimize expressions of xenophobia in society (Wodak Citation2015), it is possible that these attitudes are expressed across the voter group, and thus individual-difference variables are less relevant in explaining them. Our first hypothesis is hence that xenophobia does not correlate with the variables that are linked to negative views on immigrants in other populations (see, e.g. Ekehammar et al. Citation2004): sexism, conservative attitudes [Right-Wing Authoritarianism and Social Dominance Orientation] and low levels of openness and agreeableness (H1a) On the other hand, radical right-wing voters tend to score higher on variables linked to anti-immigrant attitudes (e.g. Van Assche et al. Citation2019), and there are limitations in the degree to which voters can be expected to adjust their views according to the party line (Harteveld, Kokkonen, and Dahlberg Citation2017). Moreover, party preferences may be based on various criteria, but voters tend to support politicians whose messages are congruent with their personality dispositions and worldviews (Caprara and Zimbardo Citation2004; Bakker, Schumacher, and Rooduijn Citation2021). Hence, xenophobia may be merely one expression of a coherent worldview that is guiding new patterns of voting behaviour. Thus, the alternative for our first hypothesis is that the correlation patterns do not differ across the two voter groups and resemble those found in the general population.Footnote3 (H1b) Also, we explored correlations of xenophobia with variables that are linked to right-wing orientation and/or support for an anti-establishment party (e.g. Jylhä, Rydgren, and Strimling Citation2019a; Oscarsson and Holmberg Citation2013) but are less commonly tested in social psychological literature explaining intergroup attitudes: socioeconomic attitudes, institutional distrust and experienced societal exclusion.

The third aim was to explore the role of xenophobia in potentially influencing voter behaviour and party support. To this end, we investigated second-hand party support and sympathy for the Sweden Democrats among mainstream and radical right-wing voters with low and high levels of xenophobia. We expected to observe more sympathy for the Sweden Democrats among the respondent who express high (vs. low) levels of xenophobia (H2). Moreover, we investigated why voters with low levels of xenophobia support a radical right-wing party (Sweden Democrats) and why voters with high levels of xenophobia continue supporting a mainstream party (Conservative Party) that does not prioritize immigration in their political programme. We reasoned that having right-leaning socioeconomic attitudes – which tend to determine support for a mainstream right-wing party in Sweden – could predict support for the Conservative Party among voters with high levels of xenophobia (H3) (see also Rydgren Citation2002; Stockemer, Halikiopoulou, and Vlandas Citation2020). As for voters with low levels of xenophobia, we expected them to be more prone to supporting Sweden Democrats if they experience negative relationship with the society and societal institutions, or if they hold conservative and authoritarian attitudes (H4). These views could entail dissatisfaction with the recent societal developments in Sweden (a liberal country with, up until recently, relatively generous immigration policies), making voters more susceptible to the anti-establishment and authoritarian messages of a radical right-wing party (Jylhä, Rydgren, and Strimling Citation2019a; Oskarson and Demker Citation2015).

Method

Participants

Participants were Sweden Democrat (N = 2216) and Conservative Party (N = 634) supporters.Footnote4 Also, the sample included 548 supporters of the Social Democratic Party (included only in the Preliminary analyses in the Method-section) and 119 participants who stated they would not vote. Party support was indicated by the question, “How would you vote if there were an election for Riksdag today?”. Additionally, 101 respondents participated but were excluded from the analyses due to incorrect or untrustworthy response pattern.

Age ranged between 18 and 79 among Sweden Democrat voters (M = 55.8, SD = 15.3) and between 18 and 79 among Conservative Party voters (M = 55.9, SD = 17.0). In both voter groups, most of the respondents were male (72 per cent/65 per cent), had either university (37 per cent/50 per cent) or upper secondary school education (50 per cent/42 per cent), lived in urban areas (66 per cent/71 per cent) and had Swedish-born parents (86 per cent/87 per cent).

Procedure

The data were collected in January–May 2018 prior to the general election in September. An independent research company, Novus, administered the survey, at the request of the authors, to panelists from a randomly recruited pool of approximately 40,000 volunteers. An invitation to the survey was sent to a selection of panelists who had indicated in the background questionnaire that they either had voted (in 2014), or would consider voting (in 2018), for one of the parties of focus in the present study. The sample also included 239 panelists (only SD supporters) recruited by a market research company, Norstat. An online survey (median time: 18.5 minutes) included questions about attitudes, values and personality characteristics. For full description of data collection, see Jylhä, Rydgren, and Strimling Citation2019b.

Material

If not otherwise stated, participants responded to the items on a scale ranging from 1 (disagree completely) to 5 (agree completely), or 6 (don’t know; handled as missing values). Full scales are presented in the supplemental online material, and the mean values and standard deviations in .

Immigration and immigrants

Xenophobia was measured by a three-item index (α = .85, example: “I don’t want an immigrant to marry into my family”). The wordings were adapted from the Bogardus (Citation1926) Social Distance Scale that is commonly used to investigate intergroup attitudes. Continuous coding (1-5) was used in analyses where predictors of xenophobia were tested. To enable analyses comparing groups with high or low xenophobia, also a dichotomous transformation of this index was done: low xenophobia (0) included scores 1–2 and high xenophobia (1) included scores 4–5. In this index, middle scores, denoting neither agreement nor disagreement with the items, were excluded.

Immigration scepticism was measured by the item “Immigration to Sweden should be reduced”, and negative perception of the societal consequences of immigration by a three-item index (α = .79, example: “Immigration costs too many public resources”). Distrust of a foreign group was measured by the item “To what degree do you trust in Middle-East-born people that you meet for the first time?” (reversed) (scale: 1–5 [very small degree to very high degree]).

Attitudinal and personality variablesFootnote5

Three-item scales were used to measure sexist attitudes (α = .71, “Feminism has gone too far” and two items from Glick and Fiske Citation1996), socioeconomic attitudes (α = .62, example: “Taxes should be reduced”), Right-Wing Authoritarianism (α = .47; from Zakrisson Citation2005, example: “To stop the radical and immoral currents in the society today there is a need for a strong leader”), and Social Dominance Orientation (α = .56; from Ho et al. Citation2015, example: “It’s probably a good thing that certain groups are at the top and other groups are at the bottom”), as well as personality variables Openness (α = .55, example: “I value artistic, aesthetic experiences”) and Agreeableness (α = .56, example: “I am considerate and kind to almost everyone”) using the short Big Five scale (Lang et al. Citation2011).

We measured institutional distrust by an index capturing low trust in the national parliament, courts of law and the Swedish public service television (α = .76, example: “To what degree do you trust that Riksdagen manages its work?”, reversed), and experienced societal exclusion with the item “I generally feel that I am a part of society” (reversed).

Support for the Sweden Democrats

We measured second-hand party choice by asking “If your first choice could not be voted for, which party would you vote for?” The three biggest parties (Social Democrats, Conservative Party and Sweden Democrats) were analyzed separately, but smaller parties were clustered according to the governmental blocks they belonged to at the time of the measurement (centre-right or red/green) and parties that are not in the Parliament were clustered as “other”.

Sympathy for Sweden Democrats was measured by the questions “If Sweden Democrats governed Sweden, how would you see Sweden’s future” (scale ranging from 0 [very negatively] to 5 [very positively]) and “To what degree do you trust news reporting from the following media”: Samtiden (an online newspaper published by the Sweden Democrats), Avpixlat/Samhällsnytt (alternative media with Sweden Democratic and anti-immigrant focus). For comparison purposes, we also measured trust in Sveriges Television (the national public TV consistently criticized by the Sweden Democrats).

Demographics and control variables

To control for the effects of demographics and sociological variables, we included variables that can influence attitudes towards immigrants and immigration. Education level was measured with three categories that were further dummy coded as 0 (elementary school and high school) and 1 (university education). Gender was indicated either as woman (0) or man (1). Ethnicity was measured by parents’ birth land, coded as 0 (Swedish parents), 1 (one parent immigrant) or 2 (both parents immigrants).

The following macro-level control variables were included (see supplemental online material for descriptions): Size of municipality (Cities/Medium towns and Small towns/Rural areas), and proportion of immigrants in one’s living area in year 2017.

Results

Prevalence of, and correlations between, immigration and immigrant attitudes

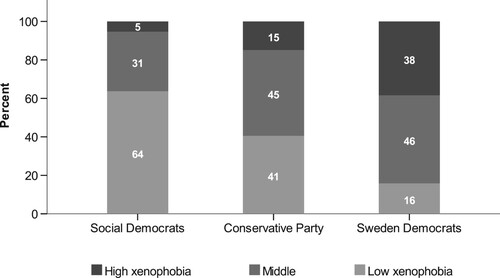

Analyses on the dependent variable. To examine the descriptive statistics and the distribution of our dependent variable, we tested mean value differences as well as the prevalence of low, middle and high xenophobia across all three voting groups. Sweden Democrat voters (M = 3.4, SD = 1.1) scored highest on xenophobia, followed by Conservative Party voters (M = 2.5, SD = 1.1) and Social Democrat voters (M = 1.9, SD = 1.0), F(2) = 445.37, p < .001. As for our categorical variable, high xenophobia was approximately 2.5 times more common among Sweden Democrat voters (38 per cent) than among Conservative Party voters (15 per cent) (see ). Among Social Democratic voters, high xenophobia was very uncommon (5 per cent; N = 29). This limits conclusions about group differences, which supports our decision to exclude this voter group from the scope of the present study.

Figure 1. Prevalence (%) of high, middle and low xenophobia among Social Democrat, Conservative Party and Sweden Democrat voters.

After excluding participants with middle scores in xenophobia (for the analyses comparing groups with low vs. high xenophobia), the prevalence of high xenophobia was 70.9 per cent (N = 848) among Sweden Democrat voters, and 26.9 per cent (N = 94) among Conservative Party voters. The prevalence of low xenophobia was 29.1 per cent (N = 348) among Sweden Democrat voters, and 73.1 per cent (N = 256) among Conservative Party voters.

Overlap and correlations between xenophobia and anti-immigration attitudes. The items meant to capture xenophobia loaded on the same factor in an exploratory factor analysis (see ). Distrust of Middle-East-born people loaded on this factor too, while the item measuring immigration scepticism loaded on the same factor as the items regarding societal consequences of immigration. These patterns support our decision to measure views of immigrants separately from views of immigration.

Table 1. Factor Analysis including items measuring anti-immigrant and anti-immigration attitudes (Factor 1/Factor 2: Eigenvalue = 4.44/1.33; 55.5/16.6 per cent of variance explained).

As shown in , high mean values were observed in both immigration scepticism and negative views on immigration in both voter groups. As to mean differences in anti-immigration views between voters with low and high xenophobia, participants with higher xenophobia expressed more negative attitudes on immigration among both Conservative party, t(348) = −20.03, p < .001, η2 = .35, and Sweden Democrat voters, t(377.8) = −15.94, p < .001, η2 = .30. Similar but weaker effects were found in immigration scepticism, which was higher among voters with higher xenophobia among both Conservative Party voters, t(335.8) = −14.81, p < .001, η2 = .22 and Sweden Democrat voters, t(357.9) = −7.84, p < .001, η2 = .10. Next, we tested if our measure for xenophobia differentiates the levels of distrust of people who are born in the Middle East. More xenophobic voters expressed more distrust, among both Conservative Party voters, t(335) = −13.26, p < .001, η2 = .34, and Sweden Democrat voters, t(529.1) = −21.12, p < .001, η2 = .31.

Correlation analysis including the full xenophobia index (1–5 range) showed similar results. Xenophobia correlated with negative attitudes on immigration, immigration scepticism and distrust of Middle-East-born people among both Conservative Party voters (rs = 50/.61/.53, ps < .001) and Sweden Democrat voters (rs = .27/.48/.51, ps < .001).

To summarize, the results suggest that xenophobia and other immigration-related attitudes are intercorrelated but distinct concepts that only share 7–37 per cent of common variance. Negative views on immigration were more common than xenophobia.

Correlates of xenophobia

Statistically significant correlations were found between xenophobia and all predictor variables and control variables (see ) in analyses in both voter groups. Xenophobia correlated positively with sexist attitudes, socioeconomic right-wing attitudes, Right-Wing Authoritarianism, Social Dominance Orientation, institutional distrust, experienced societal exclusion, age, (male) gender and living in a small town/rural area. Negative correlations were found with Openness, Agreeableness, having immigrant parent(s), education and living in an area with lower proportion of immigrants.

Table 2. Correlations between the xenophobia and the predictor variables and control variables.

We also investigated group differences between the groups scoring low or high in xenophobia. As for the control variables (See supplemental online material for full analyses), participants with higher levels of xenophobia were on average older in age in both voter groups. Among Sweden democrat voters, high xenophobia was more common among respondents who are male, have lower levels of education, and live in small towns/rural areas and areas with a lower proportion of immigrants. In both voter groups, xenophobia was unrelated to having Swedish parent(s).

As shows, differences were found in all attitudinal and personality variables in both voter groups: Participants with higher xenophobia scored lower in Openness, and Agreeableness, and higher in sexism, economic right-wing attitudes, Right-Wing Authoritarianism, Social Dominance Orientation, institutional distrust and experienced societal exclusion (ps < .05; t-scores in Table S2 in supplemental online material).

Table 3. Mean values (standard deviations) of attitudinal and personality variables per voting group and level of xenophobia.

Hierarchical multiple regression analysis

We then tested unique contributions of our independent variables on the xenophobia index in a hierarchical multiple regression analysis. Building on the above analyses, all variables that correlated with xenophobia in either voting group were included as independent variables: demographic and macro-level variables in step 1 and attitudinal and personality variables in Step 2 (missing values excluded pairwise).

In both voter groups, xenophobia was predicted by age, sexist attitudes, Right-Wing Authoritarianism, Social Dominance Orientation and (low) Agreeableness (see ). Additional predictors were institutional distrust among Conservative Party voters, and not having immigrant parent(s), living in an area with low percentage of immigrants, (low) Openness and experienced societal exclusion among Sweden Democrat voters. The model explained more variance in xenophobia among Conservative Party voters (31 per cent) than among Sweden Democrat voters (21 per cent). No concerns were detected regarding multicollinearity assumptions (Tolerances: .71–.98).

Table 4. Summary of hierarchical multiple regression analysis predicting xenophobia per voter group.

Support for Sweden Democrats

Second-hand party choice

Statistically significant group differences were found in second party choice in both voter groups (Sweden Democrats: χ2(6) = 23.36, p = .001; Conservative Party: χ2(6) = 85.06, p < .001). We analyzed mobility between the two parties in focus here.

Conservative Party voters with high xenophobia most commonly chose Sweden Democrat (66 per cent), while those with low xenophobia most commonly chose other centre-to-right parties (67 per cent) and less commonly Sweden Democrats (16 per cent). Among Sweden Democrat voters, the most notable difference was that voters with high xenophobia expressed almost two times more commonly that they would not vote for any other party than the Sweden Democrats (26 per cent), when compared to voters with low xenophobia (14 per cent). The differences in choosing the Conservative Party as a second option did not differ much (low/high xenophobia: 47/40 per cent).

Sympathy for Sweden Democrats

In both voter groups respondents with higher xenophobia expressed a more positive view of Sweden’s future if the Sweden Democrats governed, more trust in a Sweden Democratic alternative media (Avpixlat/Samhällsnytt), and less trust in the national public service TV (Sveriges Television, commonly criticized by the SD) (see ). Similar patterns were found in trust toward an online newspaper published by the Sweden Democrats (Samtiden) among Sweden Democrat, but not Conservative Party, voters.

Table 5. Mean values (standard deviations) of variables measuring sympathy for Sweden Democrats (SD) and for a media channel criticized by SD, per voting group and level of xenophobia.

Support for the Sweden Democrats among voters with high and low xenophobia

We tested in a logistic binary regression analysis which variables explain support for Sweden Democrats (vs. the Conservative Party) among respondents with high or low levels of xenophobia. To limit the number of predictor variables, we included only variables that correlated (see Table S3 in the supplemental online material) with Sweden Democrat support among voters with either low or high xenophobia. As presented in , voters with both low and high xenophobia were more likely to support Sweden Democrats if they have less right-leaning socioeconomic attitudes and higher levels of Right-Wing Authoritarianism and institutional distrust. Moreover, voters with low xenophobia more likely also support the Sweden Democrats if they score higher in sexist attitudes, and voters with high xenophobia more likely also support the Sweden Democrats if they are male and younger in age. The model explained support for Sweden Democrats better among participants with low (vs. high) scores in xenophobia (Nagelkerke pseudo R2:.50/.21), which further supports that xenophobia is an independent predictor of Sweden Democrat support.

Table 6. Summary of binary logistic regression analysis predicting support for Sweden Democrats (vs. the Conservative Party) among voters with high and low level of xenophobia.

Discussion

The present study examined xenophobia among voters of a radical right-wing party (the Sweden Democrats) and a mainstream right-wing party (the Conservative Party) in Sweden. As our first aim, we addressed the conceptual overlap and difference between anti-immigrant and anti-immigration attitudes. The results of a factor analysis and correlation analyses supported our decision to treat xenophobia as a distinct – yet correlated – concept from anti-immigration attitudes (see, however, further discussion on the overlap in both introduction and later in the discussion).

The second aim was to investigate the correlates of xenophobia in both voter groups. Supporting H1b (i.e. not H1a), we found no notable difference between these groups or in comparison to previous research results in other populations (e.g. Ekehammar et al. Citation2004). Regression analysis revealed that Right-Wing Authoritarianism was the variable with the strongest effect on xenophobia in both voter groups. Also, in line with previous research on intergroup attitudes, Social Dominance Orientation had a unique effect on xenophobia, and the effect of (low) Openness vanished in the full model among Conservative Party voters and was weakened among Sweden Democrat voters. However, unexpectedly, the effect of (low) Agreeableness remained statistically significant in both voter groups. Perhaps this is because our measure for Social Dominance Orientation – a variable that usually mediates the effect of Agreeableness on intergroup attitudes – had a low reliability that introduced error variance into measurement. Moreover, in line with previous research showing links between antipathies toward different societal groups (i.e. generalized prejudice, see e.g. Ekehammar et al. Citation2004), sexist attitudes explained a unique part of variance in xenophobia. And finally, the effects of the macro-level control variables were either non-significant or relatively weak, which could indicate that xenophobia is a stable variable that is not easily influenced by social circumstances.

The third aim was to investigate if and how xenophobia potentially influences voter behaviour and support for the radical right. To begin with, xenophobia was higher among Sweden Democrat (vs. Conservative Party) voters, and clearly less common than anti-immigration attitudes in both voter groups. As for analyses on Sweden Democrat support, the model predicted support better among voters with low levels of xenophobia, which provides additional evidence for suggesting that xenophobia is an independent predictor of supporting this party. Overall, these results support the assumption that although not all far-right voters are xenophobic, xenophobic voters tend to be more inclined to support far-right parties than other voters (Rydgren Citation2008; see also Cutts, Ford, and Goodwin Citation2011; Van Assche et al. Citation2019 for the link between racism/prejudice and far-right support).

Furthermore, we explored if more and less xenophobic voters could have different motivations to support a radical-right party, as well as why the more xenophobic Conservative Party voters do not vote for the radical right. The results showed that Right-Wing Authoritarianism, institutional distrust and less right-leaning socioeconomic attitudes predicted support for the Sweden Democrats among voters with both low and high xenophobia. That is, more support for the core issues of the European radical right and less support for the socioeconomic issues of the mainstream right are linked to Sweden Democrat support regardless of levels of xenophobia. Additionally, voters with low xenophobia were more likely to supporting the Sweden Democrats if they scored high in sexism, which indicates that socially conservative and anti-feminist views are linked to supporting a more radical option even when not holding antipathies toward immigrants per se. Moreover, participants who score high in xenophobia were more likely to support Sweden Democrats if they are male and younger in age. The results support both H3 and H4, but some of the correlations were observed regardless of the levels of xenophobia and provide information beyond our theoretical discussions. Importantly, unlike in previous research on far-right support (e.g. Cornelis and Van Hiel Citation2015), Social Dominance Orientation did not predict Sweden Democrat support. Future research could investigate if this is due to some measurement issues, or some other explanation. For example, measures capturing general views on inequality may have somewhat limited predictive power in explaining radical-right support in Sweden: the liberal and egalitarian norms are widespread in this country, and the Sweden Democrats have aimed to promote their agenda without confronting these norms at a principal level (Moffitt Citation2017; Towns, Karlsson, and Eyre Citation2014). On the other hand, it is not surprising that Right-Wing Authoritarianism correlated stronger than Social Dominance Orientation with both anti-immigrant attitudes and radical-right support: This could be expected in cultural contexts where immigration is depicted as a societal threat (related to, e.g. criminality: see Cohrs and Stelzl Citation2010; Dunn Citation2015), such as has been the case in Sweden over the past years (Strömbäck Citation2018).

Finally, considering the potential influence for voter behaviour, Conservative Party voters with a high level of xenophobia expressed somewhat less institutional distrust, and thus could potentially be mobilized by the Sweden Democrats or other parties that use anti-establishment rhetoric. Among Sweden Democrat voters, however, voters with low and high xenophobia did not differ in terms of distrust. Thus, the anti-establishment messages of the Sweden Democrats may have mobilized voters who are distrusting toward societal institutions and/or decreased trust among their voters (see also Hellström and Nilsson Citation2010; Rooduijn et al. Citation2017), but unfortunately, causality could not be determined due to our cross-sectional design. We also found that a third of Sweden Democrat voters with high xenophobia would not vote if this party was not an option and, as compared to Sweden Democrat voters with low xenophobia, they experience being a part of the society to a lesser degree. They also have a more positive view of Sweden’s future if the Sweden Democrats were to govern and more trust in Sweden Democratic media. In sum, the results support H2. The results could indicate that the potential voter base for the radical right is larger and more stable among more xenophobic voters, particularly in a societal context where an anti-immigration party is considered as legitimate and where immigration is depicted as a serious societal problem that needs to be addressed in politics.

Research on voter behaviour commonly relies on existing datasets that have, despite their multiple strengths, certain shortcomings: Only relatively small subsets of the sample represent specific voter groups, and the included set of variables are fixed, and researchers cannot therefore freely choose their research questions. The large sample size of the present study enabled well-powered analyses on within-group differences in two right-wing voter groups, and the set of variables was specifically selected to test the relevant issues when investigating the recent changes in voting behaviour. A limitation is that our study was constrained to only one country but there is large variability among the radical right-wing party family in Europe. However, we believe that our results can be generalized to several other European countries because the included measures aimed to capture the core ideologies and issue preferences of these parties. As a further limitation, this study was cross-sectional, and no claims can be made about causality. For example, an anti-immigration party may shape their voters views (Harteveld, Kokkonen, and Dahlberg Citation2017), and future studies should thus examine further if xenophobia influences party support and voter behaviour, and/or vice versa.

Regarding conceptual considerations, we acknowledge that distinguishing different immigration-related attitudes is complicated, as brought up in the introduction. However, our measure for xenophobia seems to successfully captures resentment of immigrants: Distrust of Middle-East-born people loaded on the same factor with these items, while the items for immigration scepticism and societal effects of immigration loaded together on the same factor. Also, of importance when discussing if radical right-wing party could alter or legitimize expressions of xenophobia, it should be noted that majority of Sweden democrat voters are either not avoiding interaction with immigrants or are at least following the social norms that prohibit expressing such avoidance. This question could be studied further using alternative measures, for example differentiating between immigrant groups that are more or less rejected in society (see e.g. Bohman Citation2018; Ford Citation2011; Theorin and Strömbäck Citation2020). Moreover, further research could clarify the differences and measurement issues in relation to studying xenophobia, ethnic prejudice and/or racism (for conceptual discussions, see e.g. Van Hiel and Mervielde Citation2005). Prejudice refers to an attitude involving prejudgments that involves a cognitive representation (stereotype) and an emotional response (like/dislike) related to a particular group of people (e.g. immigrants) (Stangor, Sullivan, and Ford Citation1991). In some definitions, also behavioural acts, or readiness to act, (discrimination) is included as a core characteristic. Racism is an ideological view including a belief that some racial or ethnic groups are inherently inferior to others and is, as a concept, closely linked to institutional structures and power relations (Augoustinos and Every Citation2015; see, however e.g. Van Hiel and Mervielde Citation2005 for discussion on modern racism). In sum, we join others (Cutts, Ford, and Goodwin Citation2011; Rydgren Citation2008; Theorin and Strömbäck Citation2020) to call for more finetuned conceptualizations and measurements on anti-immigrant/immigration attitudes.

To conclude, our results firstly indicate that the increased focus on immigration in society has not altered psychological explanations to xenophobia, and secondly support suggestions that various reasons may contribute to radical right support (e.g. institutional distrust and social conservatism). However, it seems that the radical right-wing has a larger potential voter base in those segments of the population that express higher xenophobia, at least in the contemporary societal context where the threats of immigration are actively debated.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Coalition between the Conservative Party, the Center Party, the Liberals and Christian Democrats. Alliance was formed to challenge the dominance of Social Democratic Party in the Swedish politics.

2 Some more centrally placed Sweden Democrats did not face expulsion when expressing racist views.

3 Some correlations may be weaker among Sweden Democrat or Conservative Party voters due to smaller variation in these variables in these voter groups. However, we focus on investigating the patterns in correlations, and comparing the strengths of these correlations is outside the scope of this paper.

4 Data were part of a larger project that aimed to investigate the changing political landscape in Sweden and have previously been used in a descriptive research report (Jylhä, Rydgren, and Strimling Citation2019b) and in two articles investigating research questions that are unrelated to the present analyses (Jylhä, Rydgren, and Strimling Citation2019a; Jylhä, Strimling, and Rydgren Citation2020).

5 Some of the scales measuring attitudinal and personality variables yielded a poor reliability. This is common for short measures capturing variables including more than one facet or dimension. Considering the validity problems when using single items to capture such variables, we formed indexes regardless of the low alpha scores.

References

- Aichholzer, J., and M. Zandonella. 2016. “Psychological Bases of Support for Radical Right Parties.” Personality and Individual Differences 96: 185–190.

- Allport, G. W. 1954. The Nature of Prejudice. Cambridge, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Altemeyer, B. 1981. Right-Wing Authoritarianism. University Press.

- Augoustinos, M., and D. Every. 2007. “The Language of “Race” and Prejudice: A Discourse of Denial, Reason, and Liberal-Practical Politics.” Journal of Language and Social Psychology 26: 123–141.

- Augoustinos, M., and D. Every. 2015. “Racism: Social Psychological Perspectives.” In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, edited by J. D. Wright, 2nd ed, 864–869. Elsevier. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780080970868240828?via%3Dihub.

- Bakker, B. N., G. Schumacher, and M. Rooduijn. 2021. “The Populist Appeal: Personality and Anti-Establishment Communication.” The Journal of Politics 83 (2): 589–601.

- Betz, H.-G., and C. Johnson. 2004. “Against the Current – Stemming the Tide: The Nostalgic Ideology of the Contemporary Radical Populist Right.” Journal of Political Ideologies 9: 311–327.

- Blinder, S., R. Ford, and E. Ivarsflaten. 2013. “The Better Angels of our Nature: How the Antiprejudice Norm Affects Policy and Party Preferences in Great Britain and Germany.” American Journal of Political Science 57: 841–857.

- Bogardus, E. S. 1926. “Social Distance in the City.” Proceedings and Publications of the American Sociological Society 20: 40–46.

- Bohman, A. 2018. “Who’s Welcome and Who’s Not? Opposition Towards Immigration in the Nordic Countries 2002-2014.” Scandinavian Political Studies 41: 283–306.

- Caprara, G. V., and P. G. Zimbardo. 2004. “Personalizing Politics: A Congruency Model of Political Preference.” American Psychologist 59: 581–594.

- Citrin, J., M. Levy, and M. Wright. 2014. “Multicultural Policy and Political Support in European Democracies.” Comparative Political Studies 47: 1531–1557.

- Cohrs, J. C., and M. Stelzl. 2010. “How Ideological Attitudes Predict Host Society Members’ Attitudes Toward Immigrants: Exploring Cross-National Differences.” Journal of Social Issues 66: 673–694.

- Cornelis, I., and A. Van Hiel. 2015. “Extreme Right-Wing Voting in Western Europe: The Role of Social-Cultural and Anti-Egalitarian Attitudes.” Political Psychology 36: 749–760.

- Cutts, D., R. Ford, and M. J. Goodwin. 2011. “Anti-Immigrant, Politically Disaffected or Still Racist After All? Examining the Attitudinal Drivers of Extreme Right Support in Britain in the 2009 European Elections.” European Journal of Political Research 50: 418–440.

- Duckitt, J. 2001. “A Dual-Process Cognitive-Motivational Theory of Ideology and Prejudice.” In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, edited by M. P. Zanna, Vol. 33, 41–113. New York: Academic Press.

- Dunn, K. 2015. “Preference for Radical Right-Wing Populist Parties among Exclusive-Nationalists and Authoritarians.” Party Politics 21: 367–380.

- Ekehammar, B., N. Akrami, M. Gylje, and I. Zakrisson. 2004. “What Matters Most to Prejudice: Big Five Personality, Social Dominance Orientation, or Right-Wing Authoritarianism?” European Journal of Personality 18: 463–482.

- Elgenius, G., and J. Rydgren. 2017. “The Sweden Democrats and the Ethno-Nationalist Rhetoric of Decay and Betrayal.” Sociologisk Forskning 4: 353–358.

- Erlingsson, GÓ, K. Vernby, and R. Öhrvall. 2014. “The Single-Issue Party Thesis and the Sweden Democrats.” Acta Politica 49: 196–216.

- Ford, R. 2011. “Acceptable and Unacceptable Immigrants: How Opposition to Immigration in Britain is Affected by Migrants’ Region of Origin.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 37 (7): 1017–1037.

- Glick, P., and S. T. Fiske. 1996. “The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory: Differentiating Hostile and Benevolent Sexism.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 70: 491–512.

- Halapuu, V., T. Paas, T. Tammaru, and A. Schütz. 2013. “Is Institutional Trust Related to Pro-Immigrant Attitudes? A Pan-European Evidence.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 54: 572–593.

- Halikiopoulou, D., and T. Vlandas. 2019. “What is New and What is Nationalist About Europe’s New Nationalism? Explaining the Rise of the Far Right in Europe.” Nations and Nationalism 25: 409–434.

- Harteveld, E., A. Kokkonen, and S. Dahlberg. 2017. “Adapting to Party Lines: The Effect of Party Affiliation on Immigration Attitudes.” West European Politics 40 (6): 1177–1197.

- Hatakka, N., M. K. Niemi, and M. Välimäki. 2017. “Confrontational Yet Submissive: Calculated Ambivalence and Populist Parties’ Strategies of Responding to Racism Accusations in the Media.” Discourse & Society 28: 262–280.

- Hellmer, K., J. T. Stenson, and K. M. Jylhä. 2018. “What's (not) Underpinning Ambivalent Sexism?: Revisiting the Roles of Ideology, Religiosity, Personality, Demographics, and Men's Facial Hair in Explaining Hostile and Benevolent Sexism.” Personality and Individual Differences 122: 29–37.

- Hellström, A., and T. Nilsson. 2010. “We are the Good Guys’: Ideological Positioning of the Nationalist Party Sverigedemokraterna in Contemporary Swedish Politics.” Ethnicities 10: 55–76.

- Ho, A. K., J. Sidanius, N. Kteily, J. Sheehy-Skeffington, F. Pratto, K. E. Henkel, R. Foels, and A. L. Stewart. 2015. “The Nature of Social Dominance Orientation: Theorizing and Measuring Preferences for Inequality Using the New SDO7 Scale.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 109: 1003–1028.

- Inglehart, R. F., and P. Norris. 2017. “Trump and the Xenophobic Populist Parties: The Silent Revolution in Reverse.” Perspectives on Politics 15: 443–454.

- Ivarsflaten, E. 2008. “What Unites Right-Wing Populists in Western Europe?” Comparative Political Studies 41: 3–23.

- Ivarsflaten, E., S. Blinder, and R. Ford. 2010. “The Anti-Racism Norm in Western European Immigration Politics: Why We Need to Consider it and How to Measure it.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 20: 421–445.

- Jost, J. T., J. Glaser, A. W. Kruglanski, and F. J. Sulloway. 2003. “Political Conservatism as Motivated Social Cognition.” Psychological Bulletin 129: 339–375.

- Jungar, A.-C., and A. R. Jupskås. 2014. “Populist Radical Right Parties in the Nordic Region: A New and Distinct Party Family?” Scandinavian Political Studies 37: 215–238.

- Jylhä, K. M., J. Rydgren, and P. Strimling. 2019a. “Radical Right-Wing Voters from Right and Left: Comparing Sweden Democrat Voters who Previously Voted for the Conservative Party or the Social Democratic Party.” Scandinavian Political Studies 42 (3-4): 220–244.

- Jylhä, K. M., J. Rydgren, and P. Strimling. 2019b. “Sweden Democrat Voters: Who are They, Where Do They Come from and Where are they Headed?” Research Report 2019:1. Institute for Future Studies, Stockholm.

- Jylhä, K. M., P. Strimling, and J. Rydgren. 2020. “Climate Change Denial Among Radical Right-Wing Supporters.” Sustainability 12 (23): 10226.

- Lang, F. R., D. John, O. Lüdtke, J. Schupp, and G. G. Wagner. 2011. “Short Assessment of the Big Five: Robust Across Survey Methods Except Telephone Interviewing.” Behavior Research Methods 43: 548–567.

- McCrae, R. R., and P. T. Costa Jr. 2008. “The Five-Factor Theory of Personality.” In Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research, edited by O. P. John, R. W. Robins, and L. A. Pervin, 3rd ed., 159–180. New York: Guilford.

- Merriam-Webster. n.d. Xenophobia. Accessed 11 May 2021. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/xenophobia.

- Moffitt, B. 2017. “Liberal Illiberalism? The Reshaping of the Contemporary Populist Radical Right in Northern Europe.” Politics and Governance 5: 112–122.

- Mols, F., and J. Jetten. 2016. “Explaining the Appeal of Populist Right-Wing Parties in Times of Economic Prosperity.” Political Psychology 37: 275–292.

- Mudde, C. 2007. Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mudde, C. 2010. “The Populist Radical Right: A Pathological Normalcy.” West European Politics 33: 1167–1186.

- Mudde, C. 2019. The Far Right Today. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Mulinari, D., and A. Neergaard. 2014. “We are Sweden Democrats Because We Care for Others: Exploring Racisms in the Swedish Extreme Right.” European Journal of Women’s Studies 21: 43–56.

- Oscarsson, H., and S. Holmberg. 2013. Nya Svenska Väljare. Stockholm: Norstedts Juridik.

- Oskarson, M., and M. Demker. 2015. “Room for Realignment: The Working-Class Sympathy for Sweden Democrats.” Government and Opposition 50: 629–651.

- Pratto, F., J. Sidanius, L. M. Stallworth, and B. F. Malle. 1994. “Social Dominance Orientation: A Personality Variable Predicting Social and Political Attitudes.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 67: 741–763.

- Rooduijn, M. 2018. “What Unites the Voter Bases of Populist Parties? Comparing the Electorates of 15 Populist Parties.” European Political Science Review 10: 351–368.

- Rooduijn, M., W. van der Brug, S. L. de Lange, and J. Parlevliet. 2017. “Persuasive Populism? Estimating the Effect of Populist Messages on Political Cynicism.” Politics and Governance 5: 136–145.

- Rooduijn, M., S. Van Kessel, C. Froio, A. Pirro, S. De Lange, D. Halikiopoulou, P. Lewis, C. Mudde, and P. Taggart. 2019. The PopuList: An Overview of Populist, Far Right, Far Left and Eurosceptic Parties in Europe. www.popu-list.org.

- Rydgren, J. 2002. “Radical Right Populism in Sweden: Still a Failure, but for How Long?” Scandinavian Political Studies 25: 27–56.

- Rydgren, J. 2003. “Meso-Level Reasons for Racism and Xenophobia: Some Converging and Diverging Effects of Radical Right Populism in France and Sweden.” European Journal of Social Theory 6: 45–68.

- Rydgren, J. 2007. “The Sociology of the Radical Right.” Annual Review of Sociology 33: 241–262.

- Rydgren, J. 2008. “Immigration Sceptics, Xenophobes or Racists? Radical Right-Wing Voting in Six West European Countries.” European Journal of Political Research 47: 737–765.

- Rydgren, J. 2017. “Radical Right-Wing Parties in Europe: What’s Populism Got to do With it?” Journal of Language and Politics 16: 485–496.

- Rydgren, J., and S. van der Meiden. 2019. “The Radical Right and the End of Swedish Exceptionalism.” European Political Science 18: 439–455.

- SCB. n.d. Summary of Population Statistics 1960–2018. Accessed 8 May 2019. https://www.scb.se/en/finding-statistics/statistics-by-subject-area/population/population-composition/population-statistics/pong/tables-and-graphs/yearly-statistics–the-whole-country/summary-of-population-statistics/.

- Sibley, C. G., and J. Duckitt. 2008. “Personality and Prejudice: A Meta-Analysis and Theoretical Review.” Personality and Social Psychology Review 12: 248–279.

- SOM Institute. 2020. Swedish Trends: 1986-2020. Edited by J. Martinsson, and U. Andersson. Accessed 16 June 2021. https://www.gu.se/en/som-institute/publications.

- Stangor, C., L. A. Sullivan, and T. E. Ford. 1991. “Affective and Cognitive Determinants of Prejudice.” Social Cognition 9: 359–380.

- Stavrakakis, Y., G. Katsambekis, N. Nikisianis, A. Kioupkiolis, and T. Siomos. 2017. “Extreme Right-Wing Populism in Europe: Revisiting a Reified Association.” Critical Discourse Studies 14: 420–439.

- Stockemer, D., D. Halikiopoulou, and T. Vlandas. 2020. “Birds of a Feather’? Assessing the Prevalence of Anti-Immigration Attitudes among the Far Right Electorate.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2020.1770063.

- Strömbäck, J. 2018. “(S)Trategiska (M)Isstag Bäddade för (SD).” In Snabbtänkt - Reflektioner Från Valet 2018 av Ledande Forskare, edited by L. Nord, M. Grusell, N. Bolin, and K. Falasca, 41. Sundsvall: Mid-Sweden University, DEMICOM.

- Theorin, N., and J. Strömbäck. 2020. “Some Media Matter More Than Others: Investigating Media Effects on Attitudes Toward and Perceptions of Immigration in Sweden.” International Migration Review 54: 1238–1264.

- Towns, A., E. Karlsson, and J. Eyre. 2014. “The Equality Conundrum: Gender and Nation in the Ideology of the Sweden Democrats.” Party Politics 20: 237–247.

- Urbanska, K., and G. Guimond. 2019. “Swaying to the Extreme: Group Relative Deprivation Predicts Voting for an Extreme Right Party in the French Presidential Election.” International Review of Social Psychology 31: 26.

- Van Assche, J., A. Van Hiel, K. Dhont, and A Roets. 2019. “Broadening the Individual Differences Lens on Party Support and Voting Behavior: Cynicism and Prejudice as Relevant Attitudes Referring to Modern-day Political Alignments.” European Journal of Social Psychology 49: 190–199. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10. 1002/ejsp.2377.

- Van der Linden, M., M. Hooghe, T. de Vroome, and C. Van Laar. 2017. “Extending Trust to Immigrants: Generalized Trust, Cross-Group Friendship and Anti-Immigrant Sentiments in 21 European Societies.” PLoS ONE 12: e0177369. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0177369.

- Van Dijk, T. A. 1992. “Discourse and the Denial of Racism.” Discourse & Society 3: 87–118.

- Van Hiel, A., and I. Mervielde. 2005. “Authoritarianism and Social Dominance Orientation: Relationships With Various Forms of Racism.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 35: 2323–2344. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10. 1111/j.1559-1816.2005.tb02105.x.

- Widfeldt, A. 2015. Extreme Right Parties in Scandinavia. London: Routledge.

- Wilson, M. S., and C. G. Sibley. 2013. “Social Dominance Orientation and Right-Wing Authoritarianism: Additive and Interactive Effects on Political Conservatism.” Political Psychology 34: 277–284.

- Wodak, R. 2015. The Politics of Fear: What Right-Wing Populist Discourses Mean. London: SAGE.

- Zakrisson, I. 2005. “Construction of a Short Version of the Right-Wing Authoritarianism (RWA) Scale.” Personality and Individual Differences 39: 863–872.

- Zaslove, A. 2004. “The Dark Side of European Politics: Unmasking the Radical Right.” European Integration 26: 61–81.