ABSTRACT

This paper contributes to research on the migration studies and homelessness, bringing to the fore the severe forms of deprivation among homeless European Union (EU) citizens. Drawing on 30 in-depth interviews with homeless Romanians in the city of Madrid and an extensive ethnographic observation study, the paper places the homeless themselves at the core of the analysis, highlighting their precarious ways of life as they attempt to access their right to housing as homeless European citizens. In aiming to advance new theoretical perspectives, I emphasize notions of resistance against surveillance and active engagement as forms of agency, in the search for solidarity and access to housing assistance. The conclusions highlight that the practices and feelings of the people affected could harmoniously intersect with the attention to mobility in poor urban spaces.

Introduction

Every day of the year on the pedestrian crossings of the neighbourhoods of Madrid, there are groups of people who stand in front of the cars offering to clean their windshields, or dancing, playing an instrument, or practicing acrobatic jumps. And all this to earn some coins to help them eat that day. Similarly, in the central squares of the city, cartons and carts can be seen, and a few metres away, people asking for alms. These people are, to a large extent, Romanians who are part of the daily landscape of the city. Most of them live on the streets.

This paper contributes to the research of migration and homelessness bringing to the fore the dramatic situation of homeless EU citizens. Drawing on 30 in-depth interviews with mobile homeless Romanians in the city of Madrid and an extensive observation study, the paper highlights their precarious ways of life, the exclusion and attempts to access housing as homeless EU citizens. Authors have extensively analysed life at urban margins (Lancione Citation2019; Lancione Citation2016), mobilities and mobilizations of the urban poor (Jaffe, Klaufus, and Colombijn Citation2012), the politics of embodied urban precarity, the strategies and settings of poverty management (DeVerteuil Citation2014) and the mobility linked to fixity (Jackson Citation2012). However, little is known about the relationship between the lack of housing, their resistance against surveillance and their active engagement in search for solidarity and access to housing assistance.

Inspired by an extensive body of literature on marginalization in cities (Lancione Citation2016), “the complex experiences on young who navigate uncertainty and insecurity associated with urban life” or mobilities and frictions of the homeless (Bourlessas Citation2018), this article analyses the extreme difficult experiences of homeless Romanians living on the streets of Madrid. It aims to offer a critical understanding of the way in which a lack of opportunities and a place to live affects their lives.

Placing the homeless themselves at the core of the analysis, this paper advances new theoretical perspectives by introducing both the notions of resistance as a form of struggle against deprivation and surveillance, and active engagement as a form of agency, to emphasize how homeless people seek solidarity and assistance in order to access housing. I argue that Romanian homeless people have the right to participate in housing assistance programmes (e.g. Housing First) as European citizens and that if they had this opportunity, they would adapt and recover more effectively.

The European Union (EU) advocates that housing is a fundamental human right. But more than 700,000 people – most of them migrants – face homelessness in the EU countries, a 70% increase over the last decade (European Federation of National Organizations Working with the Homeless – FEANTSA Citation2019).Footnote1 In this challenging context, the most developed EU countries are receiving an increasing number of homeless migrants from the poorest EU countries (Hansson and Mitchell Citation2018). Romania is one of these precarious issuing countries, and its citizens particularly head towards Spain and Italy, looking for work and life strategies (Marcu Citation2019). As the levels of underdevelopment and precariousness among the population worsen, the country’s citizens are forced to look for work and housing elsewhere. After thirty years of transition to the free market, Romania’s socio-economic context remains highly problematic. Romanian mobility to Spain has continued to increase despite the particularly disruptive consequences of the last global financial crisis on Spain’s construction sector, which disproportionately affected the work of Romanians who often work in the construction industry (Marcu Citation2019). According to the Spanish Ministry of Labour and Immigration (Citation2021), Romanians represented the largest group of immigrants living in Spain, with 1,087,923 citizens registered. Of that number, 163,402 lived in the Community of Madrid (National Institute of Statistics; INE) and 45,674 in Madrid itself (Register of Inhabitants Citation2021).

The most difficult problems for homeless Romanians, as EU citizens in Spain, relate to employment contracts and housing. However, “European law touches on housing in a range of fields” (Abbé Citation2020, 143). First, EU law grants all EU citizens the right to stay in another EU country for up to three months without the need for a residence permit (Directive 2004/38/EC).Footnote2 Second, article 34(3) of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights – the key text on the protection of human rights in the EU – states: “In order to combat social exclusion and poverty, the EU recognizes and respects the right to social and housing assistance so as to ensure a decent existence for all those who lack sufficient resources, in accordance with the rules laid down by Union law and national laws and practices”.Footnote3 Nonetheless, Spanish national laws and practices do not allow unregistered homeless European citizens to access housing assistance.

Unlike homeless asylum seekers and refugees, whose protection under Spanish law means they are offered access to shelters, homeless EU citizens remain unregistered and, as such, in a legal limbo. To register in the Spanish Register of Inhabitants, EU citizens must have a valid rental agreement, which implicitly means holding an employment contract. As homeless denizens are unable to do this, difficulties accessing social protection systems become crucial vulnerability factors that impact on employment and housing. Due to their economic position, they are at greater risk of remaining homeless. This reality poses a challenge to the principles of egalitarianism and social protection that are the basis of the welfare state (Hansson and Mitchell Citation2018).

Taking into account this context, the paper engages with the following question: How do homeless Romanians experience their resistance and engage actively to defend their access to housing? To delve deeper into this question, first, the paper analyses how resistance against surveillance is experienced by homeless Romanian people, emphasizing that, despite their condition, they have the ability to make their voices heard beyond the street. Second, and linked to this, the paper examines their active engagement as a form of agency enacted through volunteering, exploring community resources and identifying opportunities to become involved in housing assistance as a way to achieve their inclusion in Madrid. I emphasize that the opportunity to foster engagement between the homeless population and the host community – whether people or institutions in the local neighbourhood – is an essential part of housing assistance. After outlining the theoretical framework, I present the characteristics of the homeless Romanians in Madrid. I then define the methodology used and analyze the interviews with the respondents to highlight their experiences, their search for solidarity and housing assistance in Madrid. The conclusions highlight that the practices and feelings of the people affected could intersect with the attention to mobility in poor urban spaces.

The mobile homeless in the city: resistance and active engagement to defend housing assistance

There is a particular relationship between homeless and mobility in the city (Barker et al. Citation2009; Jackson Citation2012). Authors emphasise that mobility shapes the everyday lives of homeless people. For instance, Lancione suggests that “homelessness should just become synonymous with continuous displacement or a form of it” (Citation2016, 172).

The existing literature on homeless people covers their movement and (in)visibility, the vulnerable circumstances in which they live, their tendency to blame themselves for their suffering (Farrugia Citation2011; Parker and Fopp Citation2004) and the circumstances of those who beg in the street (Wardhaugh Citation1996). Usually, immigrant homeless people have no contact with social agents, as they try to go unnoticed. Their lives are characterized by high levels of urban mobility, ranging from the unsuccessful search for employment to entry into the crime circuit – in some cases to escape family problems in the country of origin. Some rebel against their situations, advocating “resistance to social control” in the receiving countries (Ruddick Citation1996). Using the case of homeless Romanians in Bucharest, authors such as O’Neill (Citation2021) link their “downward mobility” and wandering in the city to a manifestation of “boredom”, which is a kind of “idleness”, an inheritance of the communist era, “shared and tied to state efforts of caring for citizens” (Kideckel Citation2004 cited in O’Neill Citation2010, 14). In turn, Hansson and Mitchell (Citation2018) describe how “transnational/European beggars” became a phenomenon in rich Western European countries. Marginalization, indignation, resentment and despair are embodied by their mobility in major European cities, and appear to be the result of an accumulation of losses (home, employment, friends), or even a loss of hope (Levy Citation2021; Tervonen and Enache Citation2017; Humphris Citation2018).

In this research, the mobile Romanian homeless people move through Madrid in an attempt to resist deprivation and surveillance and to survive, while maintaining their aspirations. In doing so, they use active engagement to escape poverty and seek solidarity in accessing housing assistance. Having the freedom to circulate throughout the European space as EU citizens, Romanians practice double mobility: mobility from their countries of origin towards Spain and other EU countries, and mobility through Madrid in search of a “place” that welcomes them. As such, they accumulate a double experience of movement that pushes them to take stances, to resist and to actively participate in search of opportunities for housing assistance.

While authors have analysed the precarious experiences of homeless Romanians in their country of origin (O’Neill Citation2010; Lancione Citation2019; Teodorescu Citation2019) or in Spain (Marcu Citation2019), the specific analysis of the experiences of homeless Romanians who practice mobility overseas is scarcely reflected in the literature (Tervonen and Enache Citation2017).

Similarly, homeless voices and actions in the contestation of urban life have been significantly absent in geographical research, as Butcher and Dickens (Citation2016) note.

The authors use the concept of the “right to the city” in their studies of homelessness (Mitchell Citation2003; Citation2018; Purcell Citation2003). This concern is at the core of policy-oriented and rights-based debates, conflicting with Lefebvre’s (Citation1991) radical conception. While Lefebvre defined the “right to the city like a cry and a demand” as a “transformed and renewed right to urban life” (Citation1996 [1968], 158), current authors use other conceptions of what constitutes a right and advocate a radical openness (Attoh Citation2011, 674; Purcell Citation2014). For instance, Harvey (Citation2008, 37) “defines the right to the city as a collective right to the democratic management” (in Attoh Citation2011, 676) of urban resources, while Mitchell’s work on homelessness (Citation2003) speaks to the ways a right to the city may also be conceived of as a right against “democratic management” (see Attoh Citation2011, 676). Marcuse (Citation2012, 32) describes “the right to the city” as “a demand and aspiration, deprivation and discontent”. In turn, Attoh (Citation2011, 674), notes that “the right to the city may allow us to see rights to housing, rights against surveillance and police abuse (…) as necessarily connected”. In their work on the geography of survival, Mitchell and Heynen (Citation2009, 613) highlight the potential of the term “capaciousness” to “unify the struggles of various marginalized groups around a common rallying cry” (Attoh Citation2011, 674). They highlight the “new housing-based right-to-the-city movements” that have emerged to advocate for radically transformed housing policy that starts from what seems to be a quite radical foundation: that all people have a right to be in and part of the city.” (Mitchell and Heynen Citation2009, 613).

Scholars (Darrah-Okike et al. Citation2018; Watts, Fitzpatrick, and Johnsen Citation2018) also express concern about “surveillance as a key revanchist technique, alongside anti-homeless laws (e.g. laws outlawing camping or begging) and urban design practices that exclude the homeless from certain spaces” (Clarke and Parsell Citation2018, 3). In turn, O’Neill (Citation2010) uses the term of “revanchism” to theorize the marginalization of homeless people. Stuart analyses how homeless people are “copwise”: they employ everyday acts of circumnavigating police interaction and generate collective resistance by documenting policing, or “policing the police” (2016 quoted in Dozier Citation2019, 182). Mitchell and Heynen (Citation2009) engage with the notion of “geography of survival” to highlight what role surveillance plays in everyday survival. As they note, “surveillance encourages employees to self-govern their behaviour – they also have the effect of bringing the interstitial spaces of the city into the spotlight, bringing hidden spaces of survival into visibility” (Mitchell and Heynen Citation2009, 619).

Certain scholars also highlight the actions of vulnerable groups such as homeless people who flee from surveillance and resist attempts to change their homeless status (Schoenfeld et al. Citation2019; Clarke and Parsell Citation2018). Dozier (Citation2019, 182) argued that “these studies have aided our understanding of urban contestation by examining counter surveillance strategies and the role of the homeless and the poor in accessing housing”. This paper makes a contribution to the ways people resist and even challenge the surveillance under which they live in an attempt to defend their right to housing assistance.

This leads to the second aspect of this research, which shows the active engagement of homeless people as a form of agency for seeking their assistance and right to housing. Authors such as Valentine (Citation2008) and Amin (Citation2012) address the problem of living and coexisting in marginalization, paying special attention to the city and thinking about how the urban space could integrate and activate the engagement of homeless people. Contributions analyse the nuances of attention to the management practices of mobile homeless people (Cloke, May, and Johnsen Citation2010; DeVerteuil and Wilton Citation2009) or the constitution of ambiguous spaces of care in the provision of services for homeless people to active assistance (Johnsen, Cloke, and May Citation2005; Lancione Citation2014). “Conceptualizing the ways in which the homeless can react and overcome adversity throughout their mobile lives, scholars suggest the importance of ‘agency’, which encompasses the multiple forms” (Marcu Citation2019) by which people fight to survive and seek their goals in different places (Katz Citation2004; Jeffrey Citation2010), despite “their unequal positions situated at the intersections of various social categories (e.g. gender, religion, ethnicity, etc.)” (Vlase and Voicu Citation2014, 2420). Authors describe strong solidarity among and within homeless communities along with very inventive strategies to get by (Chelcea and Iancu Citation2015). In his study of homeless people in underground Bucharest, Lancione (Citation2019) highlights the concept of resilience “to show (…) how the underground homeless worked as a collective form of contestation from below” (Lancione Citation2019, 549). In turn, Prescott et al. (Citation2008) note that resilience is particularly necessary to the survival of homeless people, along with creative thought, in order to cope with stressful life circumstances.

This paper proposes the notion of active engagement – as a form of agency expressed by dynamic adaptation and actions that entails the ability to (self-)transform when the homeless have to confront “problematic situations” (Emirbayer and Mische Citation1998, 1012). With active engagement homeless are able to react and engage in response to challenging situations faced in the host country. They act as resilient people in meaningful activities which help to provide solidarity and policies of inclusion and equal opportunities to both EU mobile citizens and national homeless populations. I argue that opportunities to integrate into communities are essential to establishing broader support networks, reducing marginalization and helping to leave the streets behind. Active engagement can therefore lead to both personal fulfilment and the opportunity to learn about sharing knowledge and assets. This study adds to these accounts while also taking into consideration that homeless immigrants face even more difficulties integrating than native homeless people.

Structural factors as drivers of homelessness in Madrid

Homelessness (in the EU) has been exacerbated by economic policies, austerity measures and structural adjustment programmes that liberalized real estate systems and led to unaffordable rents, the withdrawal of governments as providers of housing and social protection and the lack of enforcement of legislation to protect tenants. These factors drove unemployment, property speculation, lack of support and personal crises that led to an increase in the number of homeless people (Soaita and Dewilde Citation2019; Peck and Tickell Citation2002). In Spain, specifically, the bursting “property bubble and the economic model based on it have aggravated the economic crisis, producing an unemployment rate of 27% (57% among the young) and a poverty rate” (Romanos Citation2014, 296) – having less than 60% of the medium income – of 21%.

Although unemployment decreased to 14.31% in 2020, the city of Madrid is immersed in an economic and labour model that is characterized by the predominance of the services sector and diversification, flexibilization and deregulation of the labour market. This reality affects migrants – more than other groups of workers – and their social exclusion. Thus, precarious “housing – through the material threat of eviction, displacement and the lack of affordable alternatives in the city, as well as the emotional toll that urban precarity takes on people and their future prospects – affects people’s abilities to claim urban spaces” (Muñoz Citation2018, 372).

The Spanish public housing policy is modest, aid for access is scarce (public spending on housing is 0.4% of GDP), as Spain is the country where home rental rates have increased the most (by 30% in Madrid in 2019) compared to other EU countries. But Spain simultaneously has the highest vacancy rate in the European Union (3.4 million in 2019, of which 40,000 housing units are in the city of Madrid). In fact, in the context of the economic crisis, Spain is the EU country with the highest number of evictions, with 59,671 people evicted in 2019, 6,436 of which took place in Madrid (General Council of the Judiciary Citation2019).

Consequently, poverty and social exclusion increase, manifesting the structural incapacity of the market to provide housing for poor populations. Currently, 6 million people in Spain live at risk of social exclusion (13% of the population) to add to the 8.6 million people already excluded (18.4% of the total population) (FOESSA Report Citation2019). According to the RAIS Foundation (Citation2019)Footnote4, in Spain, 35,000 people are homeless. However, “homelessness policies in Spain have traditionally addressed emergency situations, meeting the basic needs of homeless people but without tackling structural measures that could end homelessness.” (Bernard, Yuncal, and Panadero Citation2016, 59). The authors also note that “the existing resources for homeless people in Spain (from outreach teams or soup kitchens, to care centres, emergency shelters, pensions or shared apartments) do not propose long-term responses to homelessness” (Bernard, Yuncal, and Panadero Citation2016, 59). The National Institute of Statistics (INE) calculates that only 23,000 people go to care centres. Homeless immigrants are those least likely to attend care centres, especially due language problems, but also to lack of registration and documentation; in addition to homelessness and employment, they lack a support network.

However, the Social Emergency Service of Attention to Homeless People (SAMUR)Footnote5, seeks to respond to those suffering the most serious states of social exclusion. During 2019, 44% of people approached by Samur Social in the streets of Madrid were homeless immigrants. The cold weather was the most common cause of their treatment, but there were also problems of malnutrition, dehydration and lack of medication (Samur Civil Protection Citation2019. At the time of the last counting device of the Community of Madrid, in Madrid there were 1,420 homeless people, of whom 887 are homeless Romanians. They inhabit 73 out of 124 encampments.

The homeless Romanians are organized in both large groups (made up of 135 people and located in the district of Fuencarral-El Pardo, or another made up of 120 people and located in the district of Arganzuela), and in other smaller groups made up of only a few people in the neighbourhoods of Usera, Chamberi and Vicalvaro (see ).

Table 1. Homeless people in the city of Madrid. Encampments and number of homeless Romanians

The encampments where they live are marginal spaces consisting of huts or tents located near the most famous neighbourhoods of the city, but also on the outskirts, in abandoned buildings. These settlements or encampments are made from low-quality materials, lacking infrastructure and utilities, mentioned as dangerous sites in the city. They also sleep in parks, under bridges overpasses, or near highway exit ramps. Throughout the day, many of them move continuously towards other neighbourhoods of the city or hide in alleys or in vegetation so as to go unnoticed in the hustle and bustle of the city. Most live in groups, although I also met some isolated individuals. Although they are present in all districts, the data and empirical evidence show that like most homeless Romanians were mostly located in the city centre. In this way, they escape aggression and have more possibilities to “get by”. As homeless Romanians are often perceived “through narratives, images and symbols” (Breazu and Eriksson Citation2021, 140) as Roma people, this reality places them in “suitable positions for dispossession, [marginalization] and exploitation” (Vincze and Zamfir Citation2019, 446), increasing the intolerance toward them.

Like their compatriots, in Madrid Romanian Roma live isolated and marginalized in shacks, without light, water or latrines, and during the day roam the city in search of resources that allow them to survive. Despite the existence of a strategic inclusion framework to combat racism, according to the Spanish Observatory on Racism and Xenophobia OBERAXE (Citation2021), as they lack documentation and are unregistered, they are not entitled to use public services (e.g. health and education) and are not granted access to legal settlements. The most visible form of exclusion and racism consists in the stigmatization of them stealing, begging and smelling bad, which affects the entire Romanian collective in Spain. “You are Romanian, you are a gypsy” is commonly said throughout the country, despite Roma people representing between 1% and 3% of the Romanian population in the city, according to the Embassy of Romania in Spain (Citation2021). Racism is thus another means of exclusion homeless people face, not only in Spain but across Europe.

Methodology

Qualitative methodology was used to carry out this research, with 30 in-depth interviews with homeless Romanians in Madrid. Between September 2016 and October 2017, I conducted 20 interviews with men (aged between 20 and 30, 15 single and 5 married) and 10 interviews with women (aged between 19 and 22, seven single and three married). Eight of the respondents had received higher education, while the others had primary and secondary school studies. They come from the Romanian regions of Moldova and Wallachia. During the same period, I did extensive observation work in the districts of Madrid Centro, Ciudad Lineal and Chamartín. Finding and making contact with interviewees took place on the streets, given the itinerant nature of their lives. Homeless people can be resistant to granting interviews – which took place in the middle of the street, in “the middle of their lives”– as they can cause extreme feelings of shame. However, when I spoke to them in Romanian, I gained their confidence; they agreed to grant me interviews and even allowed me to photograph them for this research. The interviews were thus conducted in Romanian, transcribed and translated, and then coded and analysed using the qualitative analysis programme Atlas.ti. At the time of the interview, no respondent was registered in the census of Madrid or at the Romanian Consulate in Madrid. In addition, they did not go to shelters or soup kitchens as they explained. As for their activities, many Romanian homeless make a living by collecting paper and cardboard from waste containers or scrap metal that they look for at dawn, although some attempt to engage in activities to defend their housing assistance, while resisting police harassment. Some of them were forced by police to seek shelter in highly policed spaces such as subway stations in order to survive the night. The dramatic situation of homeless Romanians has become a social emergency because those who are not registered as residents of Madrid or with the Romanian Consulate in Spain cannot make contact with social workers, or go to shelters or soup kitchens. The interviews, lasting approximately 45 minutes, took place in the Arganzuela (7) Centro (3) Chamartin (9) and Fuencarral-Pardo (6) districts, where there are numerous homeless Romanians. The interviewees appear under pseudonyms to ensure their anonymity.

I also conducted two interviews in Spanish with social workers who are specialized in homeless care from the Federation of Associations and Centres for the Homeless (FACIAM Citation2017). The questions that I asked the homeless interviewees included information about their journeys, their arrival and journeys, their circumstances in the country of origin, and in Madrid. As Knowles (Citation2011, 136) notes “journeys provide powerful intersections from which to observe, ask questions and act”. I asked them about their lives, their activities, about their plans and actions for the future and what they expected from the authorities in Madrid and their country of origin with regard to their journeys. I established a process of synthesis and classification of the information by means of codes derived from the objectives and the script of the interviews. “The analysis of the information from the standpoint of codes, concepts and “categories identified key relations” between the data obtained and the conclusions reached” (Marcu Citation2019, 919). Given the considerable quantity of information, I have used the inductive approach of thematic analysis in which two key themes were identified: resistance against surveillance, and active engagement to seek solidarity and housing assistance.

Resistance against surveillance

One of the biggest challenges in large European cities – as in the case of Madrid – is the difficulty of accessing housing, and this difficulty is growing in Europe, increasingly affecting marginalized immigrants (FEANTSA Citation2019). When they started their journeys, the interviewed Romanian homeless people had assumed that they would find work and a house through their network of friends. However, upon arrival in Madrid, when they could not find a job or a place to live, they felt desperate. They are reluctant to accept the situation, emphasizing their resistance to police surveillance.

For instance, Daniel, a fine arts graduate who had been in Madrid for two years, tells me he is subject to constant police surveillance. He remembered his trip, and the difficulty in arriving at a place where no one was waiting for him. Although he knew the language and had some savings, the impossibility of finding a job led him to the painful situation of becoming homeless.

The police watch me. But I don't run away. Where would I go? I arrived full of hope. I wanted to do a Master’s in Fine Arts in Madrid. But things went badly for me. I ended up on the street. I've been sleeping here for about four months [pointing to one of the arches in the Plaza Mayor]. I sleep on these cardboards. I often play the violin in the subway, but the places are usually taken. I have no rights … but this situation must change for us. I will not give up; I will resist and I will fight for the right to a roof … We are European, right? (Daniel 25 years old)

For Daniel, both the journey from his country to Spain, and his mobility from one place to another to survive in Madrid have become a daily drama. Despite his situation, he remains resolute and stresses his resistance to surveillance, as shown by staying in the same place (the Plaza Mayor, where he sleeps) and enduring constant police scrutiny and control. Daniel considers that as an EU citizen he has the right to a “roof” in order to live with dignity, and as such he manifests his “right to the city” and against police surveillance (Attoh Citation2011; Mitchell Citation2003).

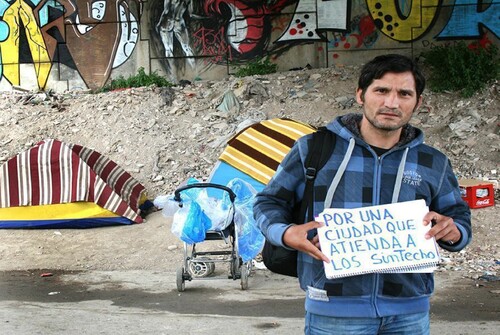

Some respondents rebel against the situation in which they find themselves. They have made their life on the street a way of survival, of defiance of vigilance, and of the defence of the homeless. This is the case of Dorin, who was at a traffic light preparing a protest banner and replied after resisting at first (see ).

Figure 1. Dorin holding the banner “For a city that cares for the homeless”. Photo by the author (2018) with permission from the respondent. (page 16).

Who am I? I have a degree in sociology and before living on the street, I worked as a social educator. I helped Romanian Roma children go to school here in Spain. But many of the centres I worked for excluded me. Now, both social services and the police are watching me. They should help me, not chase me. First, it was impotence, then anger. Never acceptance. I started to rebel against surveillance and against this situation. I am constantly changing places. And I see a lot of people change places … and sleep on the street like me. Now, I fight alongside some of them to combat the surveillance and exclusion we experience (Dorin 24 years old).

Dorin experiences resistance as a source of anger, perceiving exclusion from all sides, and leading to his becoming part of the class of the vulnerable and stigmatized. Despite his attempts to resolve his situation and to help other people at risk of social exclusion, like Roma children in Spain, he was excluded from the centres because of his frustrated and rebellious attitude. Of the 30 respondents, 17 confessed that their movements and their lives are under constant police surveillance, something Mitchell and Heynen also noted (Citation2009, 619). For homeless people like them, fighting against surveillance is also a form of revanchism (O’Neill Citation2010) and “resistance to social control” (Ruddick Citation1996). Constant changes of place and fighting against exclusion through protests are other forms of resistance against surveillance (Mitchell and Heynen Citation2009).

Respondents also expressed resistance through the constant flight from the police and the fear of being punished. Ioana, a young woman who leaves the settlement every day looking for food and employment, points out, in tears:

I run away every day … The police are watching us, and I'm afraid they'll catch me. Since I don't have any documents, I have to change places every day, because I ask for charity to eat … Sometimes I ask on the subway. But it's because I can't find a job … If anyone wanted to hire me … I know … people look down on me … but sometimes they help me. I'm so scared of the police – if they catch me they can put me in jail. However, I will fight, because I need to get out of this situation … (Ioana, 21 years old).

Ioana’s resistance to police surveillance is manifested through the flight and the fear of going to jail for begging. She refuses to stay in one place because she is afraid and she is unsuccessfully looking for a job. By resisting police surveillance through fear and flight, and by indirectly demanding employment, her voice reflects a desire for “the right to the city” “both as cry and a demand” (Lefebvre (Citation1996 [1968], 158) “a cry out of necessity and a demand for something more” (Marcuse Citation2012, 30) – in her case a need for a job. On the one hand, she is deprived of a place to live and of legal rights, and on the other hand she maintains the hope that “someone will give her a job”. Like Ioana, other respondents emphasize that, as well as fear, hope motivates them to be alert in their attempt to escape and to look for new opportunities, while resisting surveillance. The interviews clearly show that as well as its other effects, street life also urges homeless people to contribute to changing their situation through active engagement, as shown in the next section.

Active engagement to seek housing assistance

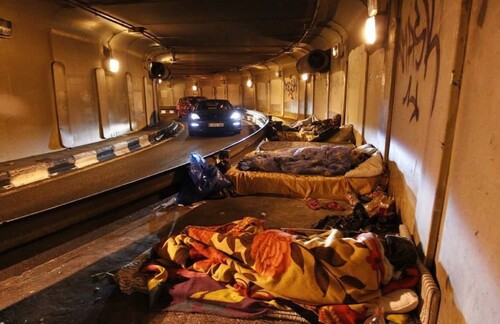

A major contributing factor to homelessness among migrants in the EU are the barriers to accessing the job markets. As European citizens, Romanian homeless in Spain have the right to participate in housing assistance programmes, however, for now, their situation is hard. The Spanish National Strategy for the Homeless (2015–2020) adopts a comprehensive approach based on the defence of human rights, unity of action, prevention and the orientation of solutions for homeless people. In turn, the “Inclusion Plan for Homeless People of the Community of Madrid 2016–2021” with a budget of 170 million euros (Community of Madrid Citation2016) includes actions to advance the improvement of the living conditions of the homeless. The Plan covers initiatives in the fields of employment, health, social services and accommodation resources. However, there is still no comprehensive policy that addresses homeless EU citizens. Unlike the Spanish homeless, who are subject to intervention processes, on many occasions successfully, in spite of the problems they face (alcoholism, addictions and mental health issues), for foreigners, in this case homeless Romanians, it is so arduous to go to hostels as they do not have “the right to reside” (Humphris Citation2018, 2) (see ).

Figure 2. Homeless Romanians sleeping in the tunnel of the M30 avenue Madrid. Photo by author 2018. (page 18).

My fieldwork, however, shows that many Romanian homeless people try to make their voices heard through their active, volunteering attitude; they commit to the host society as a way to claim support and solidarity in their search for a place to stay.

Iulia told me (see ):

I have nowhere to go. That is why I endure the cold. Every night I help give out hot food at a shelter … With Spanish volunteers. As well as asking for support, I hope I can get involved in securing help and assistance to get placed in a home for the homeless. I'm going to get involved, I'm going to stand up and be counted. I live with this hope and will try to get ahead and give up street life. I will fight! (Iulia 22 years old)

Figure 3. “I live with this hope and I will try to get ahead and give up street life.” Photo by the author (2018) with permission from the respondent. (p.19).

Iulia uses her contact with Spanish shelter volunteers to pursue her goals and seek support, and her participation in volunteer activities indirectly makes her voice heard. Like Iulia, nine of my interviewees confessed their desire to seek opportunities to explore resources that help them get off the street and obtain housing assistance.

In turn, Marian confessed:

I haven't done anything wrong. I'm not a criminal. I want to access a house … I have to do something to prove it, work with the Spaniards to get ahead. Now, I have offered to help in the construction of a building near City Hall, to load out sacks of cement. In return, they give me food and I sleep at work at night. If you work, if you engage, maybe you can get help. (Marian, 30 years old)

Marian recognizes that he needs help, yet equally knows that he is “not a criminal”. In fact, half of my respondents try to explore workable interactions with the host society. And, by doing so, they seek to combine their struggle for subsistence with an equally high need for shelter. Consequently, interviewees show homeless Romanians pursuing solidarity from the host society in search of housing solutions and assistance. As Lancione (Citation2019, 540) notes, the “resourceful and resilient poor [have the ability] to mould the city to their own demands”. An attitude of engagement thus helps people to establish social networks, gain experience, improve skills, develop self-esteem and move towards support and assistance.

Seven of my respondents also actively engage with platforms such as the so-called “Ruta contra la pobreza” (Route out of poverty), which is present in the city of Madrid and other major cities in Spain and pursues the integration of the homeless. Among the members of this platform is Gabriel, a homeless Romanian who points out:

I joined the Platform “Route out of poverty”. We are fighting for dignified integration. I tried sleeping in a shelter, but they are like detention centres, pure inhuman prisons. I will continue to fight to get homeless Romanians to be admitted to shared houses as Spaniards are. That way, I will get my life back. I will be able to recover my human dignity. (Gabriel, 30 years old)

Within the Platform “Route out of poverty” Gabriel struggles, along with other activists, to get access to a shared apartment as a means to recover his life. Some homeless people are thus “pro-active in the face of risk and uncertainty of outcomes, and fight to maintain their aspirations despite the persistence of structural influences on their lives”. Their participation in the “Route out of poverty” demonstrates that the homeless Romanians in question actively engage and seek to get involved alongside Spanish and other homeless mobile EU citizens.

A social worker from the Federation of Associations for Marginalized Homeless (FACIAM) whom I interviewed noted:

The intervention of institutions is necessary with EU mobile citizens. They get involved, actively participate … In Madrid, the shelters are overcrowded and do not have enough places. Around 1,500 people are left without a roof over their head, most of whom are EU citizens, and many homeless Romanians. A Housing First model would be good, at least for foreigners with documentation who have had a job in Spain. (Social worker- Federation of Associations for Marginalized Homeless)

In addition to highlighting the problem of access for foreigners to the shelters for the homeless, the social worker interviewed suggests, also for EU citizens, the implementation of the housing model for the homeless Housing First (existing in Madrid since 2014) – “as a housing and support (harm reduction) policy directed at homeless people” (Lancione, Stefanizzi, and Gaboardi Citation2018, 41). This consists of temporary housing (for a maximum of two years) for people who need support to get their life back. Through their commitment and active engagement, and by raising the “voice of the homeless”, homeless people not only respond to their need to be recognized and respected, but remind us that they must be incorporated into housing assistance projects. Through their involvement, they demonstrate that they can actively participate in local activities and programmes and also have the opportunity to provide feedback on the support they are receiving. The concept of active engagement therefore recognizes that the homeless should be in control of their own lives, and be encouraged to make decisions and learn from them.

Conclusions

This article contributes to the research on migration studies and homelessness by introducing the notions of resistance against police surveillance and active engagement as forms of agency, emphasizing how homeless people seek solidarity and assistance in order to access housing. The paper deals with the question of how homeless Romanians experience their resistance and are actively involved in defending their access to housing. I have argued that Romanian homeless people have the right to access housing as European citizens and that if given this opportunity they would adapt and recover more effectively. In other words, they could see positive changes in both their well-being and their social integration.

First, the findings show that while respondents resist and challenge surveillance in different ways, they are all engaged in attempts to defend their “right to the city” (Marcuse Citation2012; Attoh Citation2011; Mitchell and Heynen Citation2009). While some expressed their resistance by staying “in the same place”, challenging the constant monitoring by the police, others are continually changing places, fighting against surveillance as a form of resistance against control (Attoh Citation2011) and protesting against exclusion (Mitchell Citation2003). Furthermore, some respondents express their resistance in their flight from and fear of police surveillance, while aspiring to find opportunities that will allow them to acquire their rights. This reality shows that “ … the deprived and discontented [homeless people] need the right to housing, sanitation, mobility, education, healthcare (…) the necessities for a decent life”, as Marcuse (Citation2012, 34) rightly argues.

Second, the paper underscores that for homeless people active engagement is a form of agency as they seek assistance and the right to housing. Respondents fight to survive, pursuing their goals in different parts of the city (Katz Citation2004; Jeffrey Citation2010). They make their voices heard through their active volunteering attitude, “their ability to participate in the work and the making of the city, and the right to urban life – which is to say the right to be part of the city – to be present, to be” as Mitchell and Heynen (Citation2009, 616) note. The voice of the homeless – as interpreted in this paper – demands not only that they be recognized and respected but also incorporated into activities. Through their “capaciousness” (Mitchell and Heynen Citation2009, 616) they demonstrate their “creative thoughts” (Prescott et al. Citation2008). They actively participate in their housing assistance, trying to explore workable interactions with the host society, seeking to combine their struggle for subsistence – their resilience – with an equally strong need for shelter. On this point, the role of the assistance of the “Housing First” programme appears fundamental. Implemented for the Spanish homeless since 2014, Housing First consists of offering shared flats to several people of similar ages. This model could be adapted to meet the needs of EU citizens who experience homelessness, to involve quality intervention to include the city’s homeless mobile EU citizens.

Third, this research captures the experience of the journeys homeless Romanian people take to access their right to housing as homeless European citizens. The findings identified here may open up new avenues of research, for instance on adapting EU policies to the specific conditions of the homeless in order to curb homelessness. Future research could address the creation of policies to ensure access to housing for all citizens (EU and non-EU) and serve as a platform to build trust, generate recovery processes and achieve access to employment and training, health resources and benefits. The results could be useful for policymakers to identify priorities for the development and support of specific programmes for the homeless through interventions by institutions (housing associations, institutions or public housing agencies) that promote urban inclusion of all the homeless denizens in contemporary society. As some authors (Lancione Citation2019; Darling Citation2017; Knowles Citation2011) critically note, cities have the responsibility to demand, design and implement new and inclusive policies to attend to the homeless, helping mobile people to integrate into host societies.

Ethic statement

The article includes in-depth interviews with participants selected in the frame of the research project entitled “(Re)conceptualizing the human movement in the XXI century: strategies and impacts of the mobility of Eastern Europeans in Spain” CSO2017-2021–82238-R, with funding from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovations, and coordinated by the author.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the Journal Editors and the anonymous referees for their insightful comments and critical engagement.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 FEANTSA is a European NGO focusing on the fight against homelessness. Its ultimate goal is an end to homelessness in the EU. Created in 1989, FEANTSA brings together non-profit services that support homeless people in Europe, including over 130 member organizations from 30 countries, including 28 Member States.

2 Directive 2004/38/EC on the right of citizens of the Union and their family members to move and reside freely within the territory of the Member States amending Regulation (article 24 on equal treatment).

3 National Alliance to End Homelessness EU Charter of Fundamental Rights. Article 34 – Social security and Social assistance.

4 RAIS is an organization existing so that no one has to live on the street.

5 SAMUR – “Servicio de Asistencia Municipal de Urgencias y Rescates”. The Social Emergency Service assists to homeless people and any social emergencies impossible to be attended by first assistance services.

References

- Abbé, Pierre. 2020. Fifth Overview of Housing Exclusion in Europe 2020. Paris: Feantsa and the Foundation. https://www.feantsa.org/public/user/Resources/resources/Rapport_Europe_2020_GB.pdf.

- Amin, Ash. 2012. “Ethnicity and the Multicultural City: Living with Diversity.” Environment and Planning A 34: 959–980. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10. 1068/a3537.

- Attoh, Kafui A. 2011. What Kind of Right is the Right to the City?” Progress in Human Geography 35 (5): 669–685. doi:10.1177/0309132510394706.

- Barker, John, Peter Kraftl, John Horton, and Faith Tucker. 2009. “The Road Less Travelled — new Directions in Children’s and Young People’s Mobility.” Mobilities 4: 1–10. doi:10.1080/17450100802657939.

- Bernard, Roberto, Rebeca Yuncal, and Sonia Panadero. 2016. “Introducing the Housing First Model in Spain: First Results of the Habitat Programme.” European Journal of Homelessness 10 (1): 53–82. https://housingfirsteurope.eu/research/introducing-housing-first-model-spain-first-results-habitat-programme/.

- Bourlessas, Panos. 2018. “These People should not Rest: Mobilities and Frictions of the Homeless Geographies in Arhens City Centre.” Mobilities 13 (5): 746–760.

- Breazu, Petre, and Göran Eriksson. 2021. “Romaphobia in Romanian Press: The Lifting of Work Restrictions for Romanian Migrants in the European Union.” Discourse & Communication 15 (2): 139–162. doi:10.1177/1750481320982153.

- Butcher, Melissa, and Luke Dickens. 2016. “Spatial Dislocation and Affective Displacement: Youth Perspectives on Gentrification in London.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 40 (4): 800–816. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10. 1111/1468-2427.12432.

- Chelcea, Liviu, and Ioana Iancu. 2015. “An Anthropology of Parking: Infrastructures of Automobility, Work and Circulation.” Anthropology of Work Review 36 (2): 62–73. https://anthrosource.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10. 1111/awr.12068.

- Clarke, Andrew, and Cameron Parsell. 2018. “The Potential for Urban Surveillance to Help Support People who are Homeless: Evidence from Cairns Australia.” Urban Studies 56 (10): 1951–1967. doi:10.1177/0042098018789057.

- Cloke, Paul, Jon May, and Sarah Johnsen. 2010. Swept up Lives? Reenvisioning the Homeless City. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Community of Madrid Census. 2016. Community Homeless Inclusion Plan 2016-2021. Accessed 10 October 2021.

- Darling, Jonathan. 2017. “Forced Migration and the City: Irregularity, Informality, and the Politics of Presence.” Progress in Human Geography 41 (2): 178–198. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10. 1177/0309132516629004.

- Darrah-Okike, Jeniffer, Sarah Soakai, Susan Nakaoka, Tai Dunson-Strane, and Karen Umemoto. 2018. “It Was Like I Lost Everything”: The Harmful Impacts of Homeless-Targeted Policies.” Housing Policy Debate 28 (4): 635–651. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10. 1080/10511482.2018.1424723.

- DeVerteuil, Geoffrey. 2014. “Does the Punitive Need the Supportive? A Sympathetic Critique of Current Grammars of Urban Injustice.” Antipode 46: 874–893. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10. 1111/anti.12001.

- DeVerteuil, Geoffrey, and Robert Wilton. 2009. “Spaces of Abeyance, Care and Survival: The Addiction Treatment System as a Site of ‘Regulatory Richness’.” Political Geography 28: 463–472. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2009.11.002.

- Dozier, Deshonay. 2019. “Contested Development: Homeless Property, Police Reform, and Resistance in Skid Row, LA.” International Journal of Urban Research 43 (1): 179–194. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10. 1111/1468-2427.12724.

- Embassy of Romania in Spain. 2021. Accessed 17 March 2022. https://madrid.mae.ro/node/769.

- Emirbayer, Mustafa, and Ann Mische. 1998. “What is Agency?” American Journal of the Sociology of Education 103 (4): 964–1022. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10. 1086/231294?seq=1.

- FACIAM. 2017. Federation of Associations and Centers for Marginalized Persons. Accessed 4 March 2020. https://www.guiaongs.org/directorio/ongs/faciam-federacion-de-asociaciones-y-centros-de-ayuda-a-marginados-5-1-302/.

- Farrugia, David. 2011. “Youth Homelessness and Individualised Subjectivity.” Journal of Youth Studies 14 (7): 761–775. doi:10.1080/13676261.2011.605438.

- FEANTSA. 2019. Housing as a human right. Accessed 8 July 2021. https://www.feantsa.org/en/themes.

- FOESSA Report VIII: Social exclusion is entrenched in an increasingly unlinked society. 2019. Accessed 30 September 2021. https://www.foessa.es/viii-informe/.

- General Council of Judiciary. 2019. Evictions Report. Accessed 23 August 2021. https://www.poderjudicial.es/cgpj/es/Temas/Estadistica-Judicial/Estadistica-por-temas/Datos-penales–civiles-y-laborales/Civil-y-laboral/Estadistica-sobre-Ejecuciones-Hipotecarias/.

- Hansson, Erik, and Don Mitchell. 2018. “The Exceptional State of “Roma Beggars” in Sweden.” European Journal of Homelessness 12 (1): 15–40.

- Harvey, David. 2008. “The Right to the City.” New Left Review 53: 23–40.

- Humphris, Rachel. 2018. “On the Threshold: Becoming Romanian Roma, Everyday Racism and Residency Rights in Transition.” Social Identities 24 (4): 505–519.

- Jackson, Emma. 2012. “Fixed in Mobility: Young Homeless People and the City.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 36 (4): 725–741. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10. 1111/j.1468-2427.2012.01124.x.

- Jaffe, R., Ch. Klaufus, and F. Colombijn. 2012. “Mobilities and Mobilizations of the Urban Poor.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 36 (4): 643–654. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2012.01119.x.

- Jeffrey, Craig. 2010. “Time Pass: Youth, Class, and Time among Unemployed Young men in India.” American Ethnologist 37: 465–481. https://anthrosource.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10. 1111/j.1548-1425.2010.01266.x.

- Johnsen, Sarah, Paul Cloke, and Jon May. 2005. “Transitory Spaces of Care: Serving Homeless People on the Street.” Health & Place 11 (4): 323–336. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2004.03.002.

- Katz, Cindi. 2004. Growing up Global: Economic Restructuring and Children’s Everyday Lives. Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press.

- Kideckel, David A. 2004. “The Undead: Nicolae Ceausescu and Paternalist Politics in Romanian Society and Culture.” In Death of the Father: An Anthropology of the End in Political Authority, edited by John Borneman, 123–147. New York: Berghahn.

- Knowles, Caroline. 2011. “Cities on the Move: Navigating Urban Life.” City 15 (2): 136–153. doi:10.1080/13604813.2011.568695.

- Lancione, Michele. 2014. “Assemblages of Care and the Analysis of Public Policies on Homelessness in Turin, Italy.” City 18 (1): 25–40. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10. 1080/13604813.2014.868163.

- Lancione, Michele. 2016. “Racialised Dissatisfaction: Homelessness Management and the Everyday Assemblage of Difference.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 41 (4): 363–375. doi:10.1111/tran.12133.

- Lancione, Michele. 2019. “Weird Exoskeletons: Propositional Politics and the Making of Home in Underground Bucharest.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 43 (3): 535–550. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12787.

- Lancione, Michele, Alice Stefanizzi, and Marta Gaboardi. 2018. “Passive Adaptation or Active Engagement? The Challenges of Housing First Internationally and in the Italian Case.” Housing Studies 33 (1): 40–57. doi:10.1080/02673037.2017.1344200.

- Lefebvre, Henry. 1991. The Production of Space. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Lefebvre, Henry. 1996 [1968]. Writings on Cities. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Levy, Joshua. 2021. “Revanchism via Pedestrianism: Street-Level Bureaucracy in the Production of Uneven Policing Landscapes.” Antipode 53 (3): 906–927. doi:10.1111/anti.12702.

- Madrid City Council. 2018. Care for homeless people. Accessed 7 June 2021. https://www.comunidad.madrid/transparencia/informacion-institucional/planes-programas/plan-inclusion-personas-hogar-comunidad-madrid-2016-2021.

- Marcu, Silvia. 2019. “The Limits to Mobility: Precarious Work Experiences among Young Eastern Europeans in Spain.” Environment and Planning A 51 (4): 913–930. doi:10.1177/0308518X19829085.

- Marcuse, Peter. 2012. “Whose Right(s) to What City?” In Cities for People, not for Profit, edited by Neil Brenner, Peter Marcuse, and Margit Mayer, 24–41. New York: Routledge.

- Mitchell, Don. 2003. The Right to the City: Social Justice and the Fight for Public Space. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Mitchell, Don. 2018. “Revolution and the Critique of Human Geography: Prospects for the Right to the City After 50 Years.” Geografiska Annaler, Series B, Human Geography 100 (1): 2–11. doi:10.1080/04353684.2018.1445478.

- Mitchell, Don, and Nick Heynen. 2009. “The Geography of Survival and the Right to the City: Speculations on Surveillance, Legal Innovation, and the Criminalization of Intervention.” Urban Geography 30 (6): 611–632. doi:10.2747/0272-3638.30.6.611.

- Muñoz, Solange. 2018. “Urban Precarity and Home: There Is No “Right to the City.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 108 (2): 370–379. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10. 1080/24694452.2017.1392284?journalCode=raag21.

- O’Neill, Bruce. 2010. “Down and Then out in Bucharest: Urban Poverty, Governance, and the Politics of Place in the Postsocialist City.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 28: 254–269. doi:10.1068/d15408.

- O’Neill, Bruce. 2021. “Stuck Here: Boredom, Migration, and the Homeless Imaginary in Post-Socialist Bucharest.” Urban Geography 42 (9): 1292–1309. doi:10.1080/02723638.2019.1571829.

- Parker, Stephen, and Rodney Fopp. 2004. “I'm the Slice of pie That's Ostracised: Foucault's Technologies, and Personal Agency, in the Voice of Women who are Homeless.” Housing, Theory and Society 21: 145–154. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10 .1080/14036090410011415.

- Peck, Jamie, and Adam Tickell. 2002. “Neoliberalizing Space.” Antipode 34 (3): 380–404. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10. 1111/1467-8330.00247.

- Prescott, Margaret V. MA, Banu Sekendur, Bryce Bailey MA, and Janice Hoshino. 2008. “Art Making as a Component and Facilitator of Resiliency with Homeless Youth.” Art Therapy 25 (4): 156–163. doi:10.1080/07421656.2008.10129549.

- Purcell, Mark. 2003. “Citizenship and the Right to the Global City: Reimagining the Capitalist World Order.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 27 (3): 564–590. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.00467.

- Purcell, Mark. 2014. “Possible Worlds: Henri Lefebvre and the Right to the City.” Journal of Urban Affairs 36 (1): 141–154. doi:10.1111/juaf.12034.

- RAIS Foundation. 2019. Home Yes” Right to Housing. Accessed 1 December 2021. https://hogarsi.org/en/.

- Register of Inhabitants. 2021. Population by district and sex. Accessed 1 May 2021. https://www.madrid.es/portales/munimadrid/es/Inicio/El-Ayuntamiento/Estadistica/Areas-de-informacion-estadistica/Demografia-y-poblacion/Cifras-de-poblacion/Padron-Municipal-de-Habitantes-explotacion-estadistica-/?vgnextfmt=default&vgnextoid=e5613f8b73639210VgnVCM1000000b205a0aRCRD&vgnextchannel=a4eba53620e1a210VgnVCM1000000b205a0aRCRD.

- Romanos, Eduardo. 2014. “Evictions, Petitions and Escraches: Contentious Housing in Austerity Spain.” Social Movement Studies 13 (2), https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10. 1080/14742837.2013.830567?journalCode=csms20.

- Ruddick, Susan. 1996. Young and Homeless in Hollywood: Mapping Social Identities. New York: Routledge.

- Schoenfeld, Elizabeth, Kate Bennett, Katy Manganella, and Gage Kemp. 2019. “More Than Just a Seat at the Table: The Power of Youth Voice in Ending Youth Homelessness in the United States.” Child Care in Practice 25 (1): 112–125. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10 .1080/13575279.2018.1521376.

- Servicio de Asistencia Municipal de Urgencias y Rescates SAMUR Civil Protection. 2019. Accessed 30 June 2021. https://www.madrid.es/portales/munimadrid/es/Inicio/Emergencias-y-seguridad/SAMURProteccionCivil/?vgnextfmt=default&vgnextoid=c88fcdb1bfffa010VgnVCM100000d90ca8c0RCRD&vgnextchannel=f9cd31d3b28fe410VgnVCM1000000b205a0aRCRD&idCapitulo=5644986

- Soaita, Adriana, Mihaela, and Caroline Dewilde. 2019. “A Critical-Realist View of Housing Quality Within the Post-Communist EU States: Progressing Towards a Middle-Range.” Explanation, Housing, Theory and Society 36 (1): 44–75. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10. 1080/14036096.2017.1383934.

- Spanish Ministry of Labour and Immigration. 2021. Foreigners living in Spain. Accessed 14 November 2021. http://extranjeros.inclusion.gob.es/es/Estadisticas/operaciones/con-certificado/index.html.

- Spanish Observatory on Racism and Xenophobia OBERAXE. 2021. Accessed 13 April 2022. https://www.inclusion.gob.es/oberaxe/ficheros/documentos/MEMORIA_OBERAXE_2020_3.pdf.

- Teodorescu, Dominic. 2019. “Racialised Postsocialist Governance in Romania’s Urban Margins.” City 23 (6): 714–731. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10. 1080/13604813.2020.1717208.

- Tervonen, Miika, and Anca Enache. 2017. “Coping with Everyday Bordering: Roma Migrants and Gatekeepers in Helsinki.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 40 (7): 1114–1131. doi:10.1080/01419870.2017.1267378.

- Valentine, Gill. 2008. “Living with Difference: Reflections on Geographies of Encounter.” Progress in Human Geography 32: 323–337. doi:10.1177/0309133308089372.

- Vincze, George, and Iulian Zamfir. 2019. “Racialized Housing Unevenness in Cluj-Napoca Under Capitalist Redevelopment.” City 23 (4-5): 439–460. doi:10.1080/13604813.2019.1684078.

- Vlase, Ioana, and Malina Voicu. 2014. “Romanian Roma Migration: The Interplay Between Structures and Agency.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 37 (13): 2418–2437. doi:10.1080/01419870.2013.809133.

- Wardhaugh, Julia. 1996. “‘Homeless in Chinatown’: Deviance and Social Control in Cardboard City.” Sociology 30 (4): 701–716. doi:10.1177/0038038596030004005.

- Watts, Beth, Suzanne Fitzpatrick, and Sarah Johnsen. 2018. “Controlling Homeless People? Power, Interventionism and Legitimacy.” Journal of Social Policy 47 (2): 235–252. doi:10.1017/S0047279417000289.