ABSTRACT

Recent studies conclude that higher-educated migrants experience less belonging to the residence country than lower-educated migrants, which has been dubbed the integration paradox. World citizenship is a possible explanation yet has been left untheorized and empirically untested. We are the first to theorize and test this mechanism for Turkish migrants in the Netherlands using a mixed-methods approach. Results based on the NIS2NL survey confirm that world citizenship is an explanation of this paradox when acknowledging its interplay with belonging to the origin country. World citizenship is associated with a lower sense of belonging to the Netherlands, albeit only when migrants feel a low sense of belonging to Turkey. These findings are underlined by in-depth interviews with purposively sampled highly-skilled Turkish migrants (N = 32). Moreover, two proposed narrative strategies are vital to understand the negative association between world citizenship and national belonging. World citizenship is thus key in understanding the integration paradox.

Introduction

To belong or not to belong – that is the cosmopolitan question (Beck Citation2003, 454)

To provide further understanding of the integration paradox, this paper zooms in on the role of cosmopolitanism. Doing so, it picks up on the suggestion made by Ten Teije, Coenders, and Verkuyten (Citation2013) that higher-educated migrants can have a more open and cosmopolitan worldview than lower-educated migrants, resulting in a lower sense of belonging to their residence country. Here, we theorize about this possible answer and provide the first comprehensive empirical test of it.

The integration paradox is often studied and found among Turkish migrants in Europe, both those with a second-generation migration background (Tolsma, Lubbers, and Gijsberts Citation2012) as well as more recent migrants (Geurts, Lubbers, and Spierings Citation2020). A low sense of national belonging is recurrently problematized in debates about integration and social cohesion in residence countries as well as about migrants’ empowerment (Verkuyten; Yuval-Davis, Kannabiran, and Vieten Citation2006). This is in particular the case for migrants from Muslim-majority countries in Western European countries such as the Netherlands (De Vroome, Martinovic, and Verkuyten Citation2014), where citizens are subject to active policies as “everyone should feel at home” (Duyvendak Citation2011). Not unimportantly, a recurring notion in that debate is that a lack of belonging among migrants is often equated to a sense of belonging to another nation-state (Snel, Engbersen, and Leerkes Citation2006), despite that various studies have illustrated that this relationship is far from a “zero sum game” (Erdal and Oeppen Citation2013; Şimşek Citation2019). In this study, we focus on migrants’ sense of belonging to the residence country, in line with what is dubbed “place-belongingness” (Antonsich Citation2010), following Yuval-Davis’ (Citation2006) definition of belonging as a personal feeling of being “at home” in a place, meaning a symbolic space of familiarity, comfort, security and emotional attachment (hooks Citation2009, 213). In the remainder, we will discuss and use the term “a sense of national belonging”. In doing so, we view belonging not as an either/or property nor as something that can only be achieved in case of complete “sameness”. We moreover underline previous research in arguing that a sense of national belonging is dynamic as it is “situated within experiences and practices in everyday life, and operates alongside belonging to other collectives” (Horst and Olsen Citation2021, 80).

Returning to the causes of belonging, the literature on cosmopolitanism suggests that not only loyalty to another nation-state can hamper migrants’ belonging to a new country, but that experiencing belonging to a supranational entity, such as the world, could challenge this as well (Castles Citation2002; Helbling and Teney Citation2015; Norris and Inglehart Citation2009).Footnote1 Accordingly, we focus on world citizenship as an indicator of cosmopolitanism. And while it has been suggested before that world citizenship is likely to affect one’s sense of belonging to a specific country (Schueth and O’Loughlin Citation2008; Ten Teije, Coenders, and Verkuyten Citation2013), a question that remains is why such a (negative) association is there in the first place.

In this contribution, we will first explore to what extent a (negative) association between world citizenship and a sense of national belonging applies to the case of Turkish migrants in the Netherlands, and in doing so, whether it forms an explanation of the previously found integration paradox (Geurts, Lubbers, and Spierings Citation2020). Second, we will explore the specific underlying processes between world citizenship and a sense of national belonging by proposing and exploring two narrative strategies, whereby we understand integration as a two-way process in which migrants affect society and are affected by it. Taking this dynamic process, we underline Antonsich’s (Citation2022) view that a nation, such as the Netherlands, is not fixed and stable and that migrants’ integration is as such shaped in interaction with a specific context (Erdal and Oeppen Citation2013); realizing this allows for a better understanding of how world citizenship and belonging might be interlinked.

To summarize, we set out to answer the following research question: To what extent is the negative association between Turkish migrants’ educational level and a sense of belonging to the Netherlands due to world citizenship?

To answer our research question, we use a nested mixed-methods approach. Combining survey and interview data allows us to shed light on different elements of the studied associations. First, we use survey data of the New Immigrants Survey (Lubbers et al. Citation2018) to study to what extent the previously found negative effect between education and a sense of national belonging is explained by world citizenship. Subsequently, we propose two possible narrative strategies to understand how world citizenship could negatively relate to a sense of national belonging. We use in-depth life history interviews with 32 recent Turkish migrants from the same New Immigrants Survey to interpret the found survey results and to study how being a world citizen relates to a sense of national belonging, informing previous research on the association between cosmopolitanism and national belonging. We explore this association for the specific case of highly educated migrants, who are often found to have a lower sense of national belonging than expected in classical assimilation theories. We purposefully sampled informants from the New Immigrants Survey, which allows for rich data that reflect both highly educated migrants who, according to the survey, feel little belonging to the Netherlands (N = 15) and highly educated migrants who do experience a sense of belonging to the Netherlands (N = 17). By distinguishing between these paradox and non-paradox groups, our analyses provide empirical evidence with respect to which processes do and do not underlie the association between cosmopolitan and national belonging, called for by Castles (Citation2002). As the interview participants are drawn from the same study as survey respondents, the insights gained from the interviews can provide strong evidence to whether the proposed underlying mechanisms account for the survey results.

Theoretical background

Cosmopolitanism as possible explanation of the integration paradox

A cosmopolitan can be literally translated as citizen (polis) of the world (kosmos) (Molz Citation2005). According to some, cosmopolitanism entails any form of supranational identification. This suggest that besides feeling like a world citizen, a cosmopolitan could also entail identification with a (geographical) unit that transcends national boundaries (such as Europe), as argued by Helbling and Teney (Citation2015). The territorialization of belonging is hereby being questioned more often (Antonsich Citation2010), although the rise of the so-called “new nationalism” over the last few years could be viewed as an opposite trend (Antonsich Citation2022). Whilst the concept of world citizenship thus has various meanings and definitions (Levitt and Nyíri Citation2014), a common denominator in given definitions of cosmopolitanism from which we depart is: a state of mind and worldview, which includes a disposition of openness to cultural diversity and to the world around them (Skrbiš and Woodward Citation2011; Vertovec and Cohen Citation2002) and a sense of global belonging (Norris and Inglehart Citation2009). Within this study, we focus on cosmopolitanism in the sense of feeling like a world citizen. Similar to Caraus (Citation2018), the notion of citizenship here is not associated with formal membership or legal status, but instead relates to identities, practices and civic values of world citizenship (Horst and Olsen Citation2021).

Research among native populations illustrates that higher-educated individuals attribute less importance to national group membership due to their, on average, more cosmopolitan and open-minded worldview (Coenders and Scheepers Citation2003; Hakhverdian et al. Citation2013). Based on socialization theory, it is assumed that educational institutions affect individuals’ outlooks in various ways: by transferring norms and values as well as knowledge and information, and by the development of cognitive capacities (Coenders and Scheepers Citation2003; Inglehart Citation1997). Indeed, previous studies show that over the past two centuries, education stresses universal principles, intercultural knowledge and more generalized meanings of citizenship rather than national belonging (Bekhuis, Lubbers, and Verkuyten Citation2014; Kalmijn Citation1998) and in doing so serves as a vehicle for the spread of cosmopolitanism (Levitt and Nyíri Citation2014). Also in Turkey, it has been found that higher-educated citizens are more accepting of “the Other” as they are more welcoming towards refugees and have more gender equality attitudes (Lazarev and Sharma Citation2017; Spierings Citation2015). Education is moreover presumed to give individuals cognitive capabilities which reduce oversimplification and improve analytical skills (Coenders and Scheepers Citation2003). This allegedly makes higher-educated more open-minded as well as critical and reflective about issues that not only concern one specific nation state. Therefore, we expect that higher-educated migrants are more likely to feel like a world citizen.

In general, it has been assumed that world citizenship can overrule the need for singular belonging to any nation-state in specific (Schueth and O’Loughlin Citation2008). As Hannerz (Citation1990) puts it: “although the cosmopolitan embraces alien cultures and appreciates its differences, he does not become committed to it”. Such world citizens create and experience belonging on a supranational level, without necessarily experiencing belonging to a specific imagined community on the national level (Anderson Citation2006). Previous studies on non-migrant populations argue accordingly that this open-minded and “worldly” view among cosmopolitans may explain lower levels of national attachment and nationalistic feelings (Bekhuis, Lubbers, and Verkuyten Citation2014; Coenders and Scheepers Citation2003; Norris and Inglehart Citation2009; Ten Teije, Coenders, and Verkuyten Citation2013).

In this study we test to what extent these processes hold in a migration context. We expect that this notion also applies to migrants, where world citizenship can result in lower attachments to the new residence country. The integration paradox could then be explained by world citizenship. We therefore suppose that migrants with a higher educational level have a lower sense of belonging to the Netherlands (H1), because they are more likely to feel like a world citizen (H2).

The role of the origin country

In addition to the above, we argue that translating the cosmopolitanism hypothesis to migrants requires acknowledging migrant-specific circumstances, as “migration also means that people’s sense of belonging and connectedness to different people and places changes” (Horst and Olsen Citation2021, 10). Among recent migrants especially, a sense of belonging to the origin country is likely to relate to belonging to a new country. Indeed, previous studies on transnationalism have concluded that a sense of belonging to the origin country matters for one’s sense of belonging to the residence country, where many studies expect a negative association based on, for example, classic assimilation theories (Snel, Engbersen, and Leerkes Citation2006).

Building on these studies, we argue that such belonging to the origin country is likely to condition the association between world citizenship and belonging to the residence country. We hereby build on research by Horst and Olsen (Citation2021) showing that indeed, transnational connections can develop cosmopolitan identities and practices among migrants. In this study, we propose that there are different manifestations of world citizens that can be unravelled by its association with sustaining transnational ties. We expect that an integration paradox is only explained by world citizenship when the sense of belonging to the origin country is low. For those who experience little belonging to the origin country, world citizenship can result in less belonging to the residence country as this reflects the world citizen who indeed experiences no (need for) belonging to specific nation states (Geurts, Davids, and Spierings Citation2021). However, when someone is used to and is still experiencing belonging to the origin country, it is likely that world citizenship translates into belonging to the residence country too. This builds on the notion that transnationalism (i.e. experiencing belonging to both the origin and residence country) can be an important pathway in creating a cosmopolitan outlook and identity (Horst and Olsen Citation2021). Under the condition of already experiencing belonging to a specific (origin) country, being a world citizen is likely to appreciate and enable a sense of belonging to multiple countries, including the residence country (Geurts, Davids, and Spierings Citation2021). As a result, we argue that only when belonging to Turkey is lower, world citizenship can result in a lower sense of belonging to the Netherlands, which would explain the integration paradox. We therefore hypothesize that the integration paradox can be explained by feeling like a world citizen under the condition of a lower sense of belonging to the origin country (H3).

Quantitative study

Sample

The hypotheses are first tested using quantitative data, after which the mechanisms and processes underlying the results and assumed in the hypotheses are studied with in-depth life history interviews. We make use of the New Immigrants Survey Netherlands (NIS2NL) survey (Lubbers et al. Citation2018). NIS2NL is specifically designed to analyse early integration processes after migration. Earlier it has been evidenced that also among recent immigrants an integration paradox is present (Geurts, Lubbers, and Spierings Citation2020). We make use of the Turkish sample in the fourth wave, as this wave includes a measurement of world citizenship (N = 208). These respondents participated in all four waves of the survey. In September 2013, a sample of migrants older than 18 years old was invited to participate in a written or online survey. These invitations and the questionnaires were translated into migrants’ first language. Migrants were sampled within 18 months after their registration in a Dutch municipality. The first wave was collected in November 2013 and March 2014, after which the second and third wave followed after about 15 months each. Respondents who took part in wave 3, who agreed to participate in another wave and were still living in the Netherlands, according to Statistics Netherlands, were approached for the fourth wave in January 2018. In total, 257 Turkish migrants could be approached, of which 81% indeed participated in the fourth wave. Only 21 respondents held a Dutch citizenship, the rest held a Turkish citizenship – dual citizenship was at the time not a possibility in the Netherlands. All respondents had a valid Dutch residence permit.Footnote2 The dropout between these waves may be selective, as it is to a large extent affected by migration elsewhere or return migration. It appears that migrants who were employed, had a higher Dutch language proficiency, had a permanent intention to stay in the Netherlands, had a Dutch partner, were higher educated or experienced less group discrimination were less likely to dropout. This dropout is consequently selective, where a dropout could be an indication of a lack of identification to the residence country. As such, this selection results in a sample in the fourth wave that more closely represents the settling migrant population from Turkey in the Netherlands, as the group that settles is different from those who migrate elsewhere or return to the origin country. Although this dropout is selective, we argue these are common selection processes which also apply to results of previous studies on the integration paradox based on longer residing migrants. Moreover, prior research based on the first wave of the NIS2NL survey has illustrated that the main association between educational level and sense of national belonging is similar to the results presented here (Geurts, Lubbers, and Spierings Citation2020).

Measurements

Dependent variables

We measured a sense of national belonging by taking the mean of the following items: “How important is the following to your sense of who you are: your current country of residence”, ranging from (0) very important to (3) not important at all and “I have a strong sense of belonging to the Netherlands”, ranging from (0) totally disagree to (4) totally agree. We transformed the items to have the same scale length, ranging from 0 to 4, before taking their mean. Correlation between these items was .64. Seven respondents (3,4%) had no score on either item, which therefore were deleted from the analyses. This resulted in a final sample of 201 migrants.

Independent variables

In line with previous integration paradox studies, we included the highest obtained level of education attained in either the Netherlands, the origin country(measured on a country-specific scale), or another country. All education items were standardized into the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) scale of 2011 (UNESCO Citation2012), where answer categories range from (0) pre-primary education to (8) doctoral or equivalent. We included this linearly.Footnote3 We used one item to acknowledge to what extent one identifies as a world citizen: “I see myself as a world citizen”, where answer categories ranged from (0) totally disagree, to (4) totally agree. We measured a sense of belonging to Turkey in the same way as belonging with the Netherlands, thus by taking the mean of the following two items: “How important is the following to your sense of who you are: Turkey” and “I have a strong sense of belonging to Turkey”. We transformed the items to have the same scale length, ranging from 0 to 4, before taking their mean. Correlation between these items was .69.

Control variables

We control for a number of factors that are expected to be associated to the relationships or one of the (in)dependent variable(s). First, we included four categories to indicate migrants’ duration of stay: (1) fewer than 55 months, (2) between 55 and 65 months, (3) longer than 65 months and (4) missing. Migrants’ intention to stay was also acknowledged where answers were categorized into (1) temporary, (2) circular and (3) permanent. Migration motive (which was measured at wave 1) was included as well, with the following motives distinguished: (1) economic, (2) family, (3) education or (4) other or no specific reason. Finally, we included migrants’ sex being (0) male or (1) female, and migrants’ age at migration.

presents descriptive statistics for all variables included and indicates the % of missing values that were estimated with multiple imputation.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics, after multiple imputation (N = 201).

Analysis and results

To test the formulated hypotheses, we use ordinary least squares regression analyses. In Model 1, we include educational level and the control variables. In Model 2, we add world citizenship as mediating variable. In Model 3, we included a sense of belonging to Turkey and in Model 4 the moderation between world citizenship and belonging with Turkey was added. The final moderated mediation model was tested with the PROCESS Model 15 procedure (Hayes Citation2013).

Results are presented in . In Model 1, we see that a higher educational level is indeed negatively associated with a sense of belonging to the Netherlands. This supports Hypothesis 1 in expecting an integration paradox.

Table 2. Linear regression analysis on sense of belonging to the Netherlands (N = 201).

In Model 2, we added world citizenship to see whether this is (partly) responsible for this paradox. The main effect of educational level does not get closer to zero, which implies that world citizenship does not explain the negative effect of educational level on sense of belonging to the Netherlands, opposing Hypothesis 2. There moreover is no association between world citizenship and a sense of national belonging, which can suggest that this association depends on other conditions.

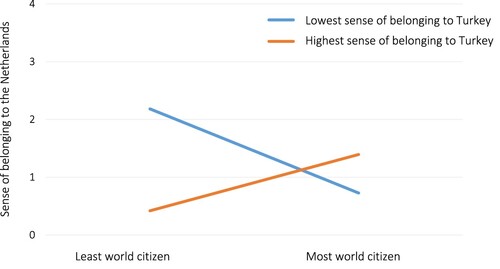

Model 3 shows that a sense of belonging to Turkey is not significantly related to a sense of belonging to the Netherlands and does not change the effects of educational level and world citizenship. In Model 4, we added the moderation between world citizenship and sense of belonging to Turkey to test Hypothesis 3. As expected, it shows that among those who experience no belonging to Turkey, world citizenship is negatively associated with a sense of belonging to the Netherlands (b = −.37). When more belonging to Turkey is experienced, this negative effect of world citizenship becomes less negative (b = .15), as shown in . This effect even turns positive for those who experience the most sense of belonging to Turkey (b = .23, not presented in table). Adding this moderation results in an insignificant effect of educational level (b = −.03) indicating that world citizenship indeed explains a negative relationship between educational level and sense of belonging to the Netherlands under the condition of a lower sense of belonging to Turkey, thereby supporting Hypothesis 3. These results moreover underline that world citizenship relates to a sense of national belonging differently depending on certain conditions. In the qualitative phase we will dive further into these underlying mechanisms that we found in the literature to understand the processes that lay underneath these found patterns and that guides us in analysing the interview material.Footnote4

Theorizing on two narrative strategies of belonging

Besides testing whether world citizenship forms an explanation of the integration paradox, this study aims to increase our understanding of its underlying mechanisms, particularly the negative association between world citizenship and migrants’ sense of national belonging to the residence country. As discussed, it is often claimed that cosmopolitans belong to the world as a whole rather than to nations, yet specific underlying reasons for this assumption are lacking (Bekhuis, Lubbers, and Verkuyten Citation2014; Coenders and Scheepers Citation2003; Norris and Inglehart Citation2009; Ten Teije, Coenders, and Verkuyten Citation2013). Based on previous studies, we have therefore derived two narrative strategies that can explain such a negative association: a lack of necessity and a lack of willingness to belong to a specific country. Such narrative strategies, be they deliberate or not, drive one’s construction of belonging, and reveal one’s longing to belong (Yuval-Davis Citation2011). This is in line with viewing identities as “narratives, stories people tell themselves and others about who they are (and who they are not)” (Yuval-Davis Citation2011, 25). Life history interviews give access to these narratives and related strategies, as they allow informants to share and frame their story and ascribe meaning to their experiences (Eastmond Citation2007).

Empirical insight into such narrative strategies is vital for a comprehensive understanding of the integration paradox and the role of world citizenship. Although these two narrative strategies are likely to relate, we expect they can form separate underlying mechanisms.

How can world citizenship shape a sense of national belonging?

With respect to necessity, constructing a sense of belonging to a new country of residence may not be worthwhile for those who already consider themselves to be world citizen. National and ethnic belonging are – to a degree – replaceable by different, more general feelings of belonging such as the cosmopolitan one. As cosmopolitans tend to be familiar with other cultures and know how to easily adapt to a new and dynamic reality, they may fit in a new country relatively easy (Molz Citation2005; Nedelcu Citation2012). Feeling like a world citizen could therefore translate in little commitment to a specific national narrative but rather to the world and humankind in general.

Feeling like a cosmopolitan could thereby be a strategic move to better one’s economic possibilities within the changing structures of the global economy (Rizvi Citation2005). This is in line with self-interest theory, where world citizenship can be an asset in a world that prizes skills of interculturality and a cosmopolitan outlook. Cosmopolitan migrants who have international (work) experience and speak English – and are thus viewed as “economically useful and skilled” – are more likely to be accepted than those who do not (Kofman Citation2005). Migrants’ self-interest could hereby not only concern economic possibilities but also social well-being (De Vries and Van Kersbergen Citation2007; Röder Citation2011). Indeed, investing in the sense of national belonging may be less worthwhile for cosmopolitans as a supranational identity can prevent experiencing strain and pressure to become “like a native citizen”. For cosmopolitan migrants who thus already feel part of an entity which is to a certain extent valued by and includes the residence country (as this country is part of the world), the need to invest in and create a specific sense of belonging to their new residence country may be low. We thus suppose that world citizenship can decrease the necessity for migrants to create a sense of belonging to their new residence country.

With respect to willingness, cosmopolitans may consciously choose to belong to a supranational entity such as the world and not to one specific nation state for various reasons (Geurts, Davids, and Spierings Citation2021). More generally, they can feel that existing national distinctions do not prove to be useful for the world and humankind and hampers their mobile lifestyle, an outlook which may be reinforced when faced with exclusion in that residence country (Cheah and Robbins Citation1998). Previous studies argue accordingly that (international) mobility and exposure to information and cultures from other places undermine distinct national group boundaries (Bekhuis, Lubbers, and Verkuyten Citation2014). In doing so, such cosmopolitans can experience little value in labelling themselves within such a container of any nation state.

All in all, we argue that world citizens may experience a lower sense of national belonging because they are less willing to belong to one specific nation state for various reasons. For example, a low sense of national belonging may reflect one’s outlook and preference to de-emphasize territorial ties and attachments. Moreover, positioning oneself as a world citizen can be seen as desirable in which (economic and social) gains from investing in a specific sense of belonging may therefore be limited. The necessity to experience belonging to the residence country may thus be smaller among world citizens. To what extent these explicit mechanisms behind the linkage between world citizenship and sense of national belonging are part of the processes underpinning the integration paradox, or whether other processes and considerations are at play, will be assessed using in-depth interviews.

Qualitative study

Sampling and analytical strategy

To explore the presence of the two narrative strategies informing us on the mechanisms of the (conditional) association between world citizenship and a sense of national belonging, we draw from in-depth life history interviews with highly skilled migrants from Turkey in the Netherlands (N = 32). These migrants moved to the Netherlands around 2012/2013. We invited those who fitted our sampling criteria and who stated to be interested in follow-up research in the survey of NIS2NL. All informants had high educational levels, meaning most finished university education. We purposefully sampled informants from the NIS2NL survey, which enabled interviewing those who, according to the survey, are highly educated but feel a low sense of belonging to the Netherlands (N = 15) and those who are highly educated but feel a high sense belonging to the Netherlands (N = 17). Within these criteria, we were able to interview a diverse group in terms of age and gender. A high share of the informants agreed to the statement of feeling like a world citizen, as we would expect based on our survey findings that higher-educated migrants are more likely to feel like a world citizen. However, in both the paradox and non-paradox group there is a share that does not agree to feeling like a world citizen (7/15 and 4/17, respectively). Seemingly, the combination of a high sense of belonging to the Netherlands (non-paradox group) and world citizenship seems just as, or even more, likely as the combination of a low sense of national belonging (paradox group) and feeling like a world citizen. This underlines the results based on the survey, suggesting that world citizenship alone is not necessarily (negatively) related to a sense of belonging to the residence country.

Interviews were conducted by the first author between summer and fall of 2018, around six to eight months after the fourth wave of the NIS2NL survey was collected. Importantly, the two proposed narrative strategies above were neither part of nor guiding for the interviews. These strategies were not part of the interview guide and the interviews were conducted with an inductive approach, avoiding the risk of priming the interviewees towards these concepts. Interviews were transcribed and analysed with MAXQDA. To discover patterns among those with a low and those with a high sense of belonging to the Netherland, we used narrative and textual analyses. We coded inductively and in vivo to use informants’ own expressions to capture the content in the first round. Then, we compared both groups more specifically in their experiences and construction of belonging in the Netherlands, and the role of the two proposed narratives on world citizenship herein.

Results

Results based on the survey data illustrate that the interplay between world citizenship and a sense of belonging to the origin country is key for understanding an integration paradox. With the two narrative strategies, it turned out that we could get further insights in the underlying process.

World citizens who belong to no specific country

The (lack of) necessity strategy

Among those migrants who identified as a world citizen, many stated in the interviews to experience little belonging to the Netherlands. One woman shared that, despite sharing the same mentality as many Dutch people with respect to human rights, she still feels like a stranger in the Netherlands:

It is like I’m a penguin, it is like I’m out of my own habitat and trying to eh, survive (…) like a tree without roots trying to survive in another piece of earth or something. (paradox sample)

When talking about one’s world citizenship, many interviewees shared sentiments that having a supranational identity somehow offers more safety and security rather than labelling oneself as part of one or two nations in specific, which taps into the narrative strategy of “necessity”. A lack of national belonging is hereby a result of a (strategic) preference, where being a world citizen is something easier and more safe, both in economic and social terms. Belonging to a specific nation state is not seen as something that one would need being a world citizen already, as shared by this informant:

For me, because it is not that important to belong somewhere. (…) Eh, for me, it is not important to feel Dutch. (paradox sample)

The (lack of) willingness strategy

Besides the lack of need to experience national belonging, some world citizens share that their willingness to belong to a specific nation is low, as argued by this woman:

I’m not Dutch, I think, not yet, I don’t. But it doesn’t matter. I mean, I, I don’t see a point why people are so interested in describing themselves even eh, in the eh, limits of ethnic identity or national identity. (…) it’s so outdated. (paradox sample)

In this case, not feeling Dutch seems a deliberate choice to not fit into certain (“outdated”) labels. This lack of willingness to feel belonging to any specific country stems from a certain outlook that wants to de-emphasize national borders and divisions in general, this being an active narrative strategy to disregard place in one’s sense of belonging. This also became clear when talking to an interviewee about celebrating King’s Day in the Netherlands:

So I don’t like you know, Dutch flags or I, I really don’t like nationalist things in general, anywhere in the world. (…) Also, I, I won’t celebrate Turkish holidays, neither religious nor national holidays really, just no national holidays. (…) I don’t know whether this is political thing, but eh, maybe it’s because I am a world citizen. (paradox sample)

This illustrates that this interviewee does not reject specifically Dutch national holidays, but does not like “nationalist things” in general.

As expected, these experiences are embedded in migrants’ recent experiences of life in Turkey. All of those who identified as world citizen expressed that they perceived a low sense of national belonging mentioned that when living in Turkey they did not feel belonging there either, as expressed by this interviewee:

I mean, I feel like a foreigner sometimes here, but as I think of my past, I felt like a foreigner in my own country too. (paradox sample).

One’s feelings of belonging to Turkey play a role and develop when living in the Netherlands. This is in part caused by changes in Turkey after migration to the Netherlands, where there is often explicitly referred to the political and economic developments. The combination of leaving an origin country that is changing and adjusting to a new life in the residence country can result in feeling part of nowhere in specific:

But as our country is changing so much, I don’t feel belonging there anymore either. And of course, I am changing too. (…) So you don’t feel any more belonging there. You don’t feel belonging here. (paradox sample)

Seemingly, the way world citizenship shapes one’s (necessity and/or willingness to) belonging to a new residence country is affected by one’s experiences in the origin country. Being used to not (completely) feel part of Turkey when living there can be a cause for wanting to identify to something supranational instead, which offers a more stable and safe space of belonging. In the majority of the interviews, social exclusion comes to the fore as key condition in this narrative strategy of willingness. Especially under circumstances that make informants feel excluded and thus like a foreigner in the residence country, being a world citizen is preferred.

Ehm, because the Dutch people will always make you feel you’re different. Being a world citizen is simply easier … (paradox sample)

As a reference group, we find that migrants who do not identify as a world citizen and do not experience belonging with the Netherlands mention that they are used to and still feel belonging to Turkey and in that respect differ from the group discussed above. World citizenship is not seen as something desirable or necessary as one is satisfied with feeling belonging to Turkey. Among the latter group, it is stressed how the Netherlands othered them, in line with Ghorashi’s (Citation2003) work on the thickness of Dutch culture, and in doing so hampered a sense of belonging to the Netherlands.

World citizens who belong everywhere

The willingness strategy

Among migrants who do experience belonging to the Netherlands, the majority identified as a world citizen. Among these interviewees, it was often shared that one felt a certain flexibility to live anywhere in the world, so also the Netherlands. Rather than belonging to no specific nation, interviewees stated to feel belonging to the world as whole, including belonging to multiple specific nations. The Netherlands is often seen as only a country where one simply happens to live now, but it could be any other place:

But as a world citizen, if it is about just, that you are able to feel at home elsewhere, that is what it is about I think to be a world citizen, because the Netherlands was just a country for me. I mean if my husband came from the US than I would have been in the US today so, but actually it was just a country. (non-paradox sample)

Next to the feeling of flexibility to live anywhere in the world, these self-identified world citizens mentioned similar ideas with respect to preferring a world without borders and nationalities as the world citizens (who experienced little belonging to the Netherlands) discussed above:

So I don’t think I really differentiate between o, okay, Turkish people or Dutch people or different countries, but it’s connecting to people in general. (non-paradox sample)

By looking beyond these borders and nationalities, these interviewees state they can experience belonging to every place they live. Rather than not feeling connected to anyone or anyplace, they experience the flexibility to feel embedded wherever they are:

I feel, I could live in eh, anywhere in the world right now. (paradox sample)

This strategy of willingness to belong to a specific country appeared key, as no other narrative strategies (including the necessity strategy) was mentioned among these world citizens. With respect to necessity, informants did not indicate to differentiate between what is a “better” or “more strategic” identity, emphasizing instead to want the perks of being able to belong wherever you are. However, they do express that they would have trouble with living in Turkey again due to recent political developments:

If I need to live in Turkey again I would find it so hard to feel adapted there because I feel eh I’m a human being here which is really difficult in Turkey. (non-paradox sample)

Although these world citizens thus express to be flexible about where to live and feel belonging to multiple places, there are limits to one’s world citizenship, where Turkey is seen as a place not suitable to live as a world citizen:

Today, I do not see a future in Turkey, not for my own child and not for myself (…) we do not have new elections for five years if I’m right so then, for those upcoming five years I do not see a future there. (non-paradox sample)

We thus see that the origin country also conditions these world citizens’ decisions and preferences of where to move and live.

As a reference group, we find that migrants who do not identify as a world citizen but do experience belonging to the Netherlands mention they have never felt like a world citizen or struggle with what this entails exactly. Some interviewees of this group show that a great sense of belonging to Turkey, already developed while living there, stimulated to invest in one’s belonging to the Netherlands as well. Others feel that their sense of belonging to Turkey is limited and try to focus on their life and belonging to the Netherlands.

Conclusion and discussion

In this study, a nested mixed methods approach was taken to test an unexplored explanation of the so-called integration paradox among recent migrants from Turkey in the Netherlands. To improve our understanding of this paradox, where higher-educated immigrants show a lower sense of belonging to the residence country, we for the first time statistically tested the possible explanation of world citizenship, as proposed by Ten Teije, Coenders, and Verkuyten (Citation2013). By introducing the argument to a migration context, we propose that migrants’ belonging to the origin country plays a key part in how world citizenship explains the integration paradox. Next, we explored which narrative strategies underlie a negative association between world citizenship and a sense of national belonging using in-depth interviews with highly educated migrants purposefully sampled from the survey data.

Results based on the survey data illustrate the presence of an integration paradox. Additionally, we show that at first sight, this paradox is not explained by world citizenship. However, it is explained when acknowledging the interrelationship between world citizenship and migrants’ sense of belonging to Turkey. Among migrants who perceive less belonging to Turkey, there is a negative association between world citizenship and belonging to the residence country. Among migrants with a higher sense of belonging to Turkey, world citizenship is positively associated to a sense of national belonging to the residence country. Acknowledging a sense of belonging to one’s origin country thus reveals when world citizenship contributes or hampers one’s sense of belonging to the residence country, which allows for understanding the integration paradox. Only for higher-educated migrants who identify less with Turkey, world citizenship is associated with a lower sense of belonging to the Netherlands. This finding builds on research on transnationalism, stressing the need for future studies to acknowledge processes that link together societies of origin and residence in various domains of life and how cosmopolitanism is part of that equation (Basch, Glick Schiller, and Szanton Blanc Citation1994; Horst and Olsen Citation2021).

Next, in-depth interviews were analysed to understand the association between world citizenship and national belonging. We contributed to the literature by empirically studying and deepening two of the few existing theoretical mechanisms on whether and why world citizenship negatively relates to a sense of national belonging (Antonsich Citation2010; Cheah and Robbins Citation1998; Schueth and O’Loughlin Citation2008). The first strategy of (lack of) necessity was only brought up among world citizens who experienced little belonging to the Netherlands. These migrants indicated to not want to label themselves within national boundaries and saw being a world citizen as easier and more “desirable”. The second strategy of (lack of) willingness appeared to be key in understanding both why some world citizens do experience belonging to their residence country, and others do not. Not wanting to categorize themselves within and preferring a world without borders and national labels was brought up among both groups. For some this, in combination with feeling socially excluded by the native population, resulted in experiencing no belonging to any country in specific and for others in experiencing a sense of belonging to the world as a whole (including different nation states). Among the latter group, one’s preference to be flexible in where to live contributes to feeling like a world citizen who experiences belonging everywhere. As such, the interviews support our proposition that a negative association between world citizenship and a sense of national belonging to the residence country should be understood by acknowledging the underlying mechanisms of (a lack of) necessity and willingness.

The mixed methods approach proved insightful as the in-depth interviews not only add to the survey results but also provide further support for these findings. In line with the survey results, the interviews point towards the importance of the origin country in how world citizens experience belonging to their current residence country. World citizens who feel little belonging to the Netherlands are migrants who experience little belonging to Turkey as well, and have experienced little belonging when living there. This is opposite for those world citizens who do experience a sense of belonging to the Netherlands, as they are used to and currently experience belonging to Turkey too. Acknowledging one’s (past and current) engagement with the origin country is thus key as it brings out various styles of world citizenship and therefore allows for understanding the integration paradox. In doing so, we also contributed to previous research on understanding migrants who feel belonging nowhere (Lähdesmaki et al. Citation2016), as we point towards the importance of one’s (past and current) ties to the origin country.

In addition, we inform previous research on the role of place among world citizens. Some world citizens choose a narrative strategy that de-emphasizes national boundaries by instead belonging to no place in specific. Building on Antonsich’s (Citation2010) work, we underline that a role for place remains by actively de-emphasizing its importance. Our nuanced understanding of world citizenship reveals the limits of its “all-inclusivity” as our informants shared that although they feel belonging everywhere, they would not consider living in Turkey at the moment as this is a place considered less suitable for world citizens. By believing in and preferring a world without borders, experiencing belonging to a place that stresses national borders is thus hampered. This is in line with Ehrkamp’s (Citation2005) research showing that one needs comfort and security in a place to feel a sense of belonging.

We expect these mechanisms to work similarly among longer established first-generation and second-generation migrants, where the role of one’s origin country may vary across generations. In a similar vein, it is a question to what extent these processes apply to migrants from other origin countries and for migrants with various migration motives. In the case of forced migration for example, world citizenship could play a similar role being conditioned by a complicated relationship with one’s origin country, whereas in the case of temporary migration for educational purposes, the association between world citizenship and national belonging to the residence country may not be affected by one’s engagement to the origin country as much. Future research could explore this accordingly, and assess the expected generalizability of our results, possibly by acknowledging various dimensions of world citizenship as we were limited by the use of a single-measurement item. Moreover, although previous research on the integration paradox has often been based on the Netherlands, various studies indicate that such a paradox is also present in other Western societies including Germany (Steinmann Citation2019), the US (Lajevardi et al. Citation2020) and Denmark (Geurts Citation2022). Given shared developments between such societies it is not unlikely that our results are generalizable beyond the Dutch case. Future research benefits from testing this and exploring the possible cross-national variation in this integration paradox and the role of world citizenship as such.

In this study, we have contributed to previous research on the integration paradox by empirically assessing the role of world citizenship using a mixed methods approach. World citizenship is a key explanation of the integration paradox, when acknowledging its interplay with migrants’ sense of belonging to their origin country, as this reveals what kind of world citizenship hampers a sense of belonging to the residence country. As such, this study informs current societal debates and policies in residence countries on the need for migrants to belong and migrants’ experienced necessity and willingness to do so.

Additional information

Ethical approval for the study described was not obtained from Radboud University, because this was not required at the time the research was conducted. The authors confirm that informed consent to participate was collected among the interviewees, which was obtained prior to the commencement of the study.

An earlier version of this study was presented at the online IMISCOE Annual Conference in July 2021.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 A lack of national belonging is even used as an indicator of cosmopolitanism in survey research (Pichler Citation2012).

2 In additional analyses, we explored the role of formal citizenship as previous studies point towards its important interrelationship with belonging (Erdal, Doeland, and Tellander Citation2018). In the quantitative analyses, citizenship did not affect the paradox nor did it change the results when included as a control variable. From the interviews, it became clear that especially a permanent residence permit, not necessarily formal citizenship, enabled a sense of security that contributed to a sense of belonging.

3 For all ordinal and interval items, deviation from linearity was checked in multivariate regression analyses using subtests with dummy variables. We decided accordingly which operationalization to include.

4 In additional analyses, perceived group discrimination and non-acceptance were added to explore how the cosmopolitan explanation holds over previously proposed explanations of the integration paradox. Adding these explanations increases the explained variance with 3,5 percent; the role of world citizenship remains the same as discussed.

References

- Alba, R., and V. Nee. 1997. “Rethinking Assimilation Theory for a New Era of Immigration.” International Migration Review 31 (4): 826–874.

- Anderson, B. 2006. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

- Antonsich, M. 2010. “Searching for Belonging – An Analytical Framework.” Geography Compass 4 (6): 644–659.

- Antonsich, M. 2022. “The Diversity Continuum: Blurring the Boundaries Between Internal and External Others among Italian Children of Migrants.” Political Geography 96: 102602.

- Basch, L., N. Glick Schiller, and C. Szanton Blanc. 1994. Nations Unbound: Transnational Projects, Postcolonial Predicaments, and Deterritorialized Nation-States. Amsterdam: Gordon and Breach.

- Beck, U. 2003. “Toward a New Critical Theory with a Cosmopolitan Intent.” Constellations (Oxford, England) 10 (4): 453–468.

- Bekhuis, H., M. Lubbers, and M. Verkuyten. 2014. “How Education Moderates the Relation Between Globalization and Nationalist Attitudes.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 26 (4): 487–450.

- Caraus, T. 2018. “Migrant Protests as Acts of Cosmopolitan Citizenship.” Citizenship Studies 22 (8): 791–809.

- Castles, S. 2002. “Migration and Community Formation Under Conditions of Globalization.” International Migration Review 36 (4): 1143–1168.

- Cheah, P., and B. Robbins. 1998. Cosmopolitics: Thinking And Feeling Beyond the Nation. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Coenders, M., and P. Scheepers. 2003. “The Effect of Education on Nationalism and Ethnic Exclusionism: An International Comparison.” Political Psychology 24 (2): 313–343.

- De Vries, C., and K. Van Kersbergen. 2007. “Interests, Identity and Political Allegiance in the European Union.” Acta Politica 42 (2/3): 307–328.

- De Vroome, T., B. Martinovic, and M. Verkuyten. 2014. “The Integration Paradox: Level of Education and Immigrants’ Attitudes Towards Natives and the Host Society.” Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 20 (2): 166–175.

- Duyvendak, J. 2011. The Politics of Home: Belonging and Nostalgia in Western Europe and the United States. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Eastmond, M. 2007. “Stories as Lived Experience: Narratives in Forced Migration Research.” Journal of Refugee Studies 20 (2): 248–264.

- Ehrkamp, P. 2005. “Placing Identities: Transnational Practices and Local Attachments of Turkish Immigrants in Germany.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 31 (2): 345–364.

- Erdal, M. B., E. M. Doeland, and E. Tellander. 2018. “How Citizenship Matters (or Not): The Citizenship–Belonging Nexus Explored Among Residents in Oslo, Norway.” Citizenship Studies 22 (7): 705–724.

- Erdal, M. B., and C. Oeppen. 2013. “Migrant Balancing Acts: Understanding the Interactions Between Integration and Transnationalism.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 39 (6): 867–884.

- Geurts, N. 2022. “Puzzling Pathways: The Integration Paradox Among Migrants in Western Europe.” Doctoral diss., Radboud University Nijmegen. Radboud repository. https://hdl.handle.net/2066/246515.

- Geurts, N., T. Davids, and N. Spierings. 2021. “The Lived Experience of an Integration Paradox: Why High-skilled Migrants from Turkey Experience Little National Belonging in the Netherlands.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (1): 69–87.

- Geurts, N., M. Lubbers, and N. Spierings. 2020. “Structural Position and Relative Deprivation Among Recent Migrants: A Longitudinal Take on the Integration Paradox.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (9): 1828–1848.

- Ghorashi, H. 2003. “Multiple Identities Between Continuity and Change. The Narratives of Iranian Women in Exile.” Focaal - European Journal of Anthropology 42: 63–75.

- Gordon, M. 1964. Assimilation in American Life: The Role of Race, Religion, and National Origins. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Hakhverdian, A., E. Van Elsis, W. Van der Brug, and T. Kuhn. 2013. “Euroscepticism and Education: A Longitudinal Study of 12 EU Member States, 1973-2010.” European Union Politics 14 (4): 522–541.

- Hannerz, U. 1990. “Cosmopolitans and Locals in World Culture.” Theory, Culture & Society 7 (2): 237–251.

- Hayes, A. 2013. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Helbling, M., and C. Teney. 2015. “The Cosmopolitan Elite in Germany: Transnationalism and Postmaterialism.” Global Networks 15 (4): 446–468.

- hooks, b. 2009. Belonging: A Culture of Place. New York: Routledge.

- Horst, C., and T. V. Olsen. 2021. “Transnational Citizens, Cosmopolitan Outlooks? Migration as a Route to Cosmopolitanism.” Nordic Journal of Migration Research 11 (1): 4–19.

- Inglehart, R. 1997. Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Kalmijn, M. 1998. “Intermarriage and Homogamy: Causes, Patterns, Trends.” Annual Review of Sociology 24 (1): 395–421.

- Kofman, E. 2005. “Figures of the Cosmopolitan.” Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 18 (1): 83–97.

- Lähdesmäki, T., T. Saresma, K. Hiltunen, S. Jäntti, N. Sääskilahti, A. Vallius, and K. Ahvenjärvi. 2016. “Fluidity and Flexibility of ‘Belonging’: Uses of the Concept in Contemporary Research.” Acta Sociologica 59 (3): 233–247.

- Lajevardi, N., K. A. Oskooii, H. L. Walker, and A. L. Westfall. 2020. “The Paradox Between Integration and Perceived Discrimination among American Muslims.” Political Psychology 41 (3): 587–606.

- Lazarev, E., and K. Sharma. 2017. “Brother or Burden: An Experiment on Reducing Prejudice Toward Syrian Refugees in Turkey.” Political Science Research and Methods 5 (2): 201–219.

- Levitt, P., and P. Nyíri. 2014. “Books, Bodies, and Bronzes: Comparing Sites of Global Citizenship Creation.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 37 (12): 2149–2157.

- Lubbers, M., M. Gijsberts, F. Fleischmann, and M. Maliepaard. 2018. The New Immigrant Survey – The Netherlands (NIS2NL). The Codebook of a Four Wave Panel Study. NWO-Middengroot, file number 420-004.

- Molz, J. 2005. “Getting a “Flexible Eye”: Round-the-World Travel and Scales of Cosmopolitan Citizenship.” Citizenship Studies 9 (5): 517–531.

- Nedelcu, M. 2012. “Migrants’ New Transnational Habitus: Rethinking Migration Through a Cosmopolitan Lens in the Digital Age.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 38 (9): 1339–1356.

- Norris, P., and R. Inglehart. 2009. Cosmopolitan Communications: Cultural Diversity in a Globalized World. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Pichler, F. 2012. “Cosmopolitanism in a Global Perspective: An International Comparison of Open-Minded Orientations and Identity in Relation to Globalization.” International Sociology 27 (1): 21–50.

- Rizvi, F. 2005. “International Education and the Production of Cosmopolitan Identities.” In Globalization and Higher Education, edited by A. Arimoto, F. Huang, and K. Yokoyama, 77–92. Hiroshima: Hiroshmia University, Research Institute for Higher Education.

- Röder, A. 2011. “Does Mobility Matter for Attitudes to Europe? A Multi-level Analysis of Immigrants’ Attitudes to European Unification.” Political Studies 59 (2): 458–471.

- Schueth, S., and J. O’Loughlin. 2008. “Belonging to the World: Cosmopolitanism in Geographic Contexts.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 39 (2): 926–941.

- Şimşek, D. 2019. “Transnational Activities of Syrian Refugees in Turkey: Hindering or Supporting Integration.” International Migration 57 (2): 268–282.

- Skrbiš, Z., and I. Woodward. 2011. “Cosmopolitan Openness.” In The Ashgate Research Companion to Cosmopolitanism, edited by M. Rovisco and M. Nowicka, 53–68. Famham: Ashgate.

- Snel, E., G. Engbersen, and A. Leerkes. 2006. “Transnational Involvement and Social Integration.” Global Networks 6 (3): 285–308.

- Spierings, N. 2015. “Gender Equality Attitudes among Turks in Western Europe and Turkey: The Interrelated Impact of Migration and Parents’ Attitudes.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (5): 749–771.

- Steinmann, J. P. 2019. “The Paradox of Integration: Why Do Higher Educated New Immigrants Perceive More Discrimination in Germany?” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (9): 1377–1400.

- Ten Teije, I., M. Coenders, and M. Verkuyten. 2013. “The Paradox of Integration.” Social Psychology 44 (4): 278–288.

- Tolsma, J., M. Lubbers, and M. Gijsberts. 2012. “Education and Cultural Integration among Ethnic Minorities and Natives in the Netherlands: A Test of the Integration Paradox.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 38 (5): 793–813.

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics. 2012. International Standard Classification of Education ISCED 2011. Montreal: UNESCO Institute for Statistics.

- Van Doorn, M., P. Scheepers, and J. Dagevos. 2013. “Explaining the Integration Paradox among Small Immigrant Groups in the Netherlands.” Journal of International Migration and Integration 14 (2): 381–400.

- Verkuyten, M. 2016. “The Integration Paradox.” American Behavioral Scientist 60 (5–6): 583–596.

- Vertovec, S., and R. Cohen. 2002. Conceiving Cosmopolitanism: Theory, Context and Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Yuval-Davis, N. 2006. “Belonging and the Politics of Belonging.” Patterns of Prejudice 40 (3): 197–214.

- Yuval-Davis, N. 2011. The Politics of Belonging: Intersectional Contestations. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Yuval-Davis, N., K. Kannabiran, and U. Vieten. 2006. The Situated Politics of Belonging. London: Sage.