ABSTRACT

The links between integration and transnationalism have attracted considerable attention in the study of migration. In contributing to these debates, this article examines the increasingly diverse landscape of self-organizations of people with migratory biographies, the so-called migrant organizations (MOs), to show how these provide opportunities for establishing and maintaining attachments in changing social and spatial contexts. Using in-depth interviews and qualitative network analysis to explore the connectivity of migrants with different actors and places, we show that the key contribution to developing experiences of belonging essentially lies in their role as places associated with home. They have a significant impact on processes of anchoring and embedding within prevailing politics of belonging. In addition to illustrating the interconnectedness between local and transnational involvement in adaptation processes, we emphasize the transformative role of MOs as unique spaces where people can develop coherent forms of belonging beyond essentialized notions of ethnicity, nationality, and “we” identities.

Introduction

“Deutschland neu Denken” (Rethinking Germany) is the claim of a network of organizations, associations, and projects in Germany that refer to themselves as “Neue Deutsche Organisationen” (NDO, New German Organizations). Since their formation in 2015, they have been actively involved in debates about new forms of “Germanness” while seeking to give a voice to people who experience exclusionary politics of belonging (Ataman et al. Citation2017). Meanwhile, the network comprises more than 150 organizations, associations and initiatives of people, together seeking to shape political and social discourses toward new and inclusive understandings of living together, that is, “conviviality” (Nowicka and Vertovec Citation2014). The emergence of organizations of this kind indicates a major and remarkable trend in German society, where people with migration biographies and their associations often suffer from misrecognition. This limited agency is consistent with the public and political environment in Germany, where “immigrants” and their associations are “more looked after than involved” (Thränhardt Citation2013, 5).

These so-called “migrant organizations” (MOs) conventionally refer to units founded by people with migration biographies who use formal organizational settings to address and support “migrants” with their activities and servicesFootnote1 (D'Angelo Citation2015; Pries and Sezgin Citation2012). The particular reference to the “migrant status” of people involved with these organizations is historically rooted in an early host of designated Ausländervereine (foreigner associations). As the number of "MOs" in Germany started to expand in the context of guest worker agreements in the 1960s, they were largely considered to concentrate on cultural activities related to maintaining ethnic identities and transnational ties (Schultze and Thränhardt Citation2013). Although many “MOs” have also engaged in the political representation of people with migration biographies and marginalized populations for many years (Ataman et al. Citation2017), lack of funding and public and political recognition has largely limited their voice and scope of action. It was not until the 1990s that “MOs” in Germany increasingly articulated political interests to promote equal participation in education, politics, media and culture and thus contributed to strengthening the rights and representation of people with international biographies (Bäßler Citation2013). Especially for those with limited opportunities for political participation, “MOs” therefore play an important role in bringing their interests to public and political attention, thus increasingly mediating between people with and without migration biographies and their institutions. Today, “MOs” increasingly accumulate political and societal attention and receive increasing recognition, especially as partners for issues of “integration” (Böhmer Citation2012; Hunger and Candan Citation2014; SVR Citation2020). Their consultation and participation activities have expanded in recent years (Halm and Sauer Citation2022; Dijkzeul and Fauser Citation2020). In addition, their funding has increased considerably since the 2010s, and they have been included in the National Integration Plan and become indispensable partners in refugee aid (Halm and Sauer Citation2022; Sultan, Friedrichs, and Weiss Citation2019).

In the course of invigorated political and public interest in the self-organization of people with migration biographies in Germany, discourses around “MOs” have largely focused on their potential contribution to political goals of “integration”. Many of these organizations, though, reject and actively seek to counteract the prevailing image of the “migrant” that requires “integration” (Ataman et al. Citation2017). Therefore, the NDO network is calling for an “inclusive understanding of belongingness” (Neue Deutsche Organisationen Citation2022), indicating new forms of inclusion beyond ethnic/national categories. Similarly, “postmigrant” scholars in Germany call for replacing “migrantology” with an overall account of social transformations (Bojadžijev and Römhild Citation2014, 11; in English see Ohnmacht and Yıldız Citation2021) and a transgression of ethnic boundaries. These reactions to what Bivand Erdal (Citation2020, 1) refers to as “integration bias” are embedded in wider criticisms of dichotomies and simplified portrayals often employed in European migration research (Amelina Citation2022; Schapendonk, Bolay, and Dahinden Citation2021; Snel, Bilgili, and Staring Citation2021; Papadopoulos and Fratsea Citation2022).

This article aims to contribute to these debates on more complex understandings of migration processes by looking at self-organizations as spaces for settlement and inclusion beyond commonly depicted dichotomies. Drawing on the concepts of social anchoring (Grzymała-Kazłowska Citation2016) and differentiated embedding (Ryan Citation2018), we explore new forms of belonging (Afonso, Barros, and Albert Citation2022), which involve coexisting cultural and social patterns, as well as assembling new ones. Therefore, we consider people to actively recreate belongingness as they transfer, rearrange and newly assemble various forms of attachment in the context of personal interactions and embedding in institutional, political, and material surroundings. Our study specifically examines the interactions between people with migration biographies and their organizations, as well as between “MOs” and their institutional, political, and material surroundings. In this way, we strive to move beyond the general and seemingly passive concept of “integration” of people into existing structures, thus taking a perspective on social transformations (Amelina, Horvath, and Meeus Citation2016). This includes recognizing that people both maintain and newly establish ties to people and places that lead to new configurations of cultural, social and spatial elements (Barglowski Citation2019; Citation2021). By studying the local interactions of people involved in “MOs”, we show that self-organization facilitates participation, network and attachment formation in changing environments. Therefore, we argue that “MOs” deserve attention as spaces of inclusion beyond the domestic sphere and personal relationships.

This article begins with a discussion of recent approaches to “migrant adaptation”, which emphasize the link between subjective experience and structural circumstances, including the differentiated and multifaceted ways in which people develop a sense of belonging (Afonso, Barros, and Albert Citation2022; Antonsich Citation2010; Grzymała-Kazłowska Citation2016; Ryan Citation2018; Yuval-Davis Citation2010). Followed by an overview of our research design and methodological approach, these analytical and theoretical perspectives serve as a starting point to explore how connections, ties, and relationships evolve in the context of people's participation in “MOs”. Based on this, we illustrate how "MOs" contribute to processes of re-negotiating and re-defining belongingness beyond the binary between integration and transnationalism.

Transnational adaptation: from integration to anchoring and embedding

In the context of examining newly forming attachments among mobile people, the prominent concept of integration has attracted widespread criticism. It is particularly criticized for its sole focus on the destination country and for exaggerating the national context of settlement processes (Faist Citation2020). Therefore, it spuriously rivets on conditions in designated places rather than allowing for encompassing explorations of the ways people become full members of societies (Korteweg Citation2017). Further criticism has pointed to the binaries created by contrasting approaches to assessing people’s practices and ties as either integrated or transnational (Joppke and Morawska Citation2003). Based on their observation of emerging “pan-ethnic identities and organizations” in the US-American context, Joppke and Morawska (Citation2003, 22) alternatively suggested considering different paths of incorporation, including co-existence, or merging into new forms of identities and belonging beyond politicized notions of integration or transnationalism.

Recent scholarship has advanced nuanced analytical refinements and new terms, including belonging (Antonsich Citation2010; Bivand Erdal Citation2020), homemaking (Boccagni and Hondagneu-Sotelo Citation2021), anchoring (Grzymała-Kazłowska Citation2016) and embedding (Ryan Citation2018) to account for the dynamic and multidimensional nature of processes of migration and settlement. According to Antonsich (Citation2010), belongingness is the result of an interplay between personal interpretations of what constitutes home and the politics of belonging that determine these experiences. Thus, belonging relates to personal feelings of attachment, as well as to politics of belonging. In this understanding, belonging is shaped by combinations of autobiographical, relational, cultural, economic, and legal factors (Arhin-Sam Citation2019). Together, these factors contribute to the creation of a sense of belonging on the individual level as well as on the level of social and collective inclusion (Arhin-Sam Citation2019). Bivand Erdal (Citation2020) also emphasizes the processual character of developing personal and collective understandings of belonging in the multiscalar approach, which illuminates the possible interactions between transnationalism and integration in the context of individual experiences. These works demonstrate that cross-border and destination country engagement can co-exist in a variety of ways, thus pointing at the necessity to acknowledge their potential entanglement rather than treating them separately. This resonates with an overall criticism of equating “integration” with destination country contexts for its nationalist ideology, while people can, in fact, integrate into networks, institutions, and organizations in different places simultaneously (Nancheva and Ranta Citation2022).

Boccagni and Hondagneu Sotelo (Citation2021) argue that the division between transnationality and integration could be overcome by examining the processes of settlement through home-making practices. This migrant-centered view is also eminent in other recent works on adaptation practices among people with migratory biographies. Grzymała-Kazłowska (Citation2016) proposes the analytical concept of social anchoring as “the process of finding significant reference points: grounded points that allow migrants to restore their socio-psychological stability in new life settings” (p.1131). In changing physical spaces, social anchors provide alternative sources of location and stability, which determine how people behave and “function” at their destinations (p.1133). Anchoring also indicates how connections to places of origin are maintained or lose importance as sources of belonging. Consequently, social anchoring provides a starting point for assessing the process of developing belongingness in the context of various locations simultaneously. The author proposes distinguishing between subjective and internal anchors, which include a person’s values, beliefs, memories, personality, and national identification. Legal status, economic resources, property and appearance, are defined as objective and external anchors. Moreover, the author includes social, professional and cultural anchors, including family roles, occupation, language, and status as an immigrant.

With a network-based approach, Ryan (Citation2018) proposes the concept of differentiated embedding to explore the dynamic, differentiated and processual ways in which people develop belongingness. Criticizing the more common notion of embeddedness as too static, embedding seeks to emphasize the agency in developing and maintaining relationships in the specific context of structural and institutional settings. Therefore, embedding represents a dynamic process determined by the establishment and maintenance of social relationships in the context of opportunity structures. Therefore, the social and territorial aspects of embeddedness influence a person’s “belonging within wider socio-political structures” (Ryan Citation2018, 236). If opportunity structures produce barriers impeding embedding, the relational element may gain greater significance and vice versa. With its focus on relationships, this concept emphasizes social networks within and across borders as the main condition for evolving experiences of belonging, which resonates with a well-established research strand in the study of migration (Bilecen Citation2020; Keskiner, Eve, and Ryan Citation2022; Ryan Citation2011). In addition to the social aspects of relationships, social ties provide key opportunities to access and use a variety of resources in different contexts and have important implications for the ways people develop abilities to navigate their lives in a new environment.

With their emphasis on the processual character of (dis)connecting with different people and places over time, these works underscore a necessity to explore evolving experiences of belonging as dynamic processes in which people develop individual approaches to settling-in in the context of prevailing structures and institutions. In this article, we aim to emphasize the role of “migrant organizations” in the processes of recreating belongingness in the context of migration, by offering opportunity structures for building and maintaining connections in changing social and spatial contexts. To this end, we draw on Antonsich’s (Citation2010) definition of belonging as a combination of personal feelings of being “at home” and the politics of belonging, as well as the concepts of homemaking, anchoring and differentiated embedding to explore the role of “MOs” in evolving modes of belonging.

Migrant organizations and new modes of adaptation in Germany

In Germany, recruitment agreements (Anwerbeabkommen) with Southern European countries mainly during the 1960s mark the beginning of rising immigration that promoted a growing number of organizations founded by people with migration biographies (Bäßler Citation2013; Hunger and Candan Citation2014). For the large number of people who migrated to Germany in the context of these agreements, there was no coherent policy approach to dealing with their adaptation to a new environment beyond their integration into the workforce (Thränhardt Citation1989; Hoesch Citation2018). In response, people with migration biographies organized themselves and created spaces for coming together and engaging in various cultural and social activities, which also allowed them to use their native languages and maintain connections to their places of origin. As migration increased and diversified throughout the 1990s, various “migrant organizations” also began to participate in political activities and pool and represent the interests of people with migration biographies in Germany (Bäßler Citation2013; SVR Citation2020). In this context, many organizations have increasingly professionalized in addressing and representing their target groups and receive growing appreciation for their work from both the public and the state (Thränhardt Citation2013). In 2006, the German government recognized “MOs” for the first time as ambassadors of the interests of “migrant” groups, especially for their efforts to promote integration, and decided to include these organizations as important stakeholders in the national integration plan (Böhmer Citation2012). Previously, people with migration biographies were rarely seen as actively involved in voluntary commitment themselves but primarily as a target group for social participation (Thränhardt Citation2013). Today, most integration concepts at federal and state levels emphasize the potential of “MOs” especially for generating and distributing social capital (Thränhardt Citation2013). According to an estimate, there are currently between 12,400 and 14,300 active “MOs”, mostly in the legal form of eingetragene Vereine (registered associations).

We draw on the conception of “MO” as suggested by Pries and Sezgin (Citation2012), who characterize them as a combination of clearly defined organizational goals, an internal structure that defines organizational functions, and unifying membership criteria based on migration histories. In addition to offering a variety of opportunities that support people with migration biographies in their everyday lives, these organizations also promote origin country attachment based on transnational activities (Levitt Citation2004; Pries and Sezgin Citation2012) and in global perspective (Dijkzeul and Fauser Citation2020). In addition to providing opportunities for social networking within the organization itself, engagement with “MOs” as locally established entities also allows people to engage with local actors and institutions (Barglowski and Bonfert Citation2021; Bonfert et al. Citation2022; Halm et al. Citation2020; SVR Citation2020; Dijkzeul and Fauser Citation2020). Therefore, they offer not only material and emotional support based on internal relationships, but also occasions to share and exchange support beyond organizational boundaries (Barglowski and Bonfert Citation2021).

Regarding the role of social networks in the context of communities and organizations, Putnam’s (Citation2000) work with a distinction between "bonding" social capital within and "bridging" social capital beyond social groups has been particularly influential. .In migration research, this distinction has frequently favoured associations with bonding social capital as “negative social capital through ethnic enclaves and ghettoization” and with bridging social capital as “positive social capital; integration and social mobility” (Ryan Citation2011, 710). This binary conception of social networks has also been criticized as too simplistic (Erdal and Oeppen Citation2013; Patulny and Svendsen Citation2007; Ryan Citation2011). Alternatively, exploring the synergies between maintaining and establishing connections across various social and spatial contexts enabled by “MOs” allows us to turn our gaze to new configurations of belonging (Achbari Citation2015; Amelina Citation2021; Easton-Calabria and Alaous Citation2022; Thränhardt Citation2013). Therefore, they provide an interesting field for investigating adaptation experiences in mobile and transnational contexts.

As with migration scholarship in general, discussions about the potential role of “MOs” for their target groups and society are also influenced by binaries, such as between integration and transnationality, or bonding and bridging social capital. Thus, “MOs” are often discussed either as promoters of integration (essentially based on bridging social capital into the host society) or as facilitators of transnational engagement (mainly based on bonding social capital between migrant groups and their relatives and friends who stay behind). In the face of recent turns in migration scholarship calling for more dynamic and processual concepts in studies of migration and adaptation, recent work proposes to replace distinctions between “migrant” and “native” with investigations of newly emerging forms of social life (Amelina Citation2022; Schapendonk, Bolay, and Dahinden Citation2021; Snel, Bilgili, and Staring Citation2021). As people with migration biographies increasingly engage in political projects through their organizations themselves, they have begun to promote a postmigrant agenda – an approach developed in the German context which has since been adapted in international discourse. Its main premise is to move migration scholarship and common knowledge around migration towards a greater appreciation of ambiguity. The goal is a “postmigrant” state of society, where the boundaries between “migrant” and “native” are no longer decisive for the future life chances of people. Ohnmacht and Yıldız (Citation2021) summarize this agenda as “radical interrogation” of the “dualisms therein of Western/non-Western, locals/foreigners, which previously determined hegemonic normality” (p.150). Various “MOs” commit themselves to agendas of this kind and actively engage in German society to reflect and potentially deconstruct stereotypic thinking about “migration” and “integration”. One example is the umbrella organization “Neue Deutsche Organisationen” (New German Organizations), whose objective is to shape new understandings of citizenship, ethnicity and belonging and new forms of “Germanness” (see Ataman et al. Citation2017). In this context, our objective here is to explore the role of “MOs” in adaptation processes and evolving belongingness from the perspective of people involved in these organizations.

Methods

The results discussed in this article are based on interviews and two group discussions with 34 interview participants from 17 different MOs in North Rhine Westphalia (Bochum, Dortmund, Duisburg), Germany between October 2020 and November 2021. These interviews were carried out as part of a collaborative research project between the Universities of Bochum, Dortmund and Duisburg-Essen that seeks to uncover the role of “MOs” in the social protection strategies of “migrants” in the German welfare architecture (see Bonfert et al. Citation2022). Some of these organizations have a “postmigrant” focus, while others do not. However, most of them offer people a place for developing new forms of belonging and connection. Having established contact with organizations with and without post-migrant agendas based on publicly accessible information and local umbrella organizations in three German cities in the Ruhr area, we were able to access members of “MOs” through their representatives, who acted as gatekeepers. Especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, this sampling proved to be very efficient. Semi-structured interviews lasted between 40 and 120 minutes, were conducted online or face-to-face, and covered a variety of questions on perceptions and management of social risks. We also collected ego-centric network charts in which participants were able to indicate individuals, groups, organizations, and institutions they considered important for their social protection. All interviews were conducted in German, while representatives of "MOs" acted as translators in a few cases where participants preferred this form of support. To gather a variety of experiences, we spoke with 17 women and 17 men of different ages, with various educational backgrounds and employment experiences, from different places of origin, and with diverse migration histories (see below). Similarly, the sample includes various "MOs" of varied sizes and with different degrees of professionalization. They include religious congregations and registered associations (e.V.) with or without formally employed staff. However, most "MOs" in the sample are managed by volunteers. Four researchers employed in the collaborative research project engaged in contacting and interviewing research participants. The study was prospectively approved by the legal offices of the involved universities. We have acquired written informed consent from all research participants, who were also extensively informed on the objectives and methods of the project, data protection, and handling of their data. After an external transcription service transcribed the recordings, all names and organizations involved were anonymized.

Table 1. Sample overview.

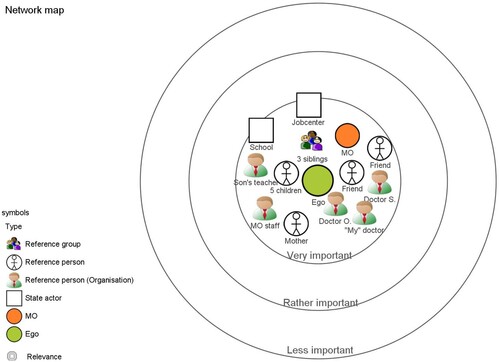

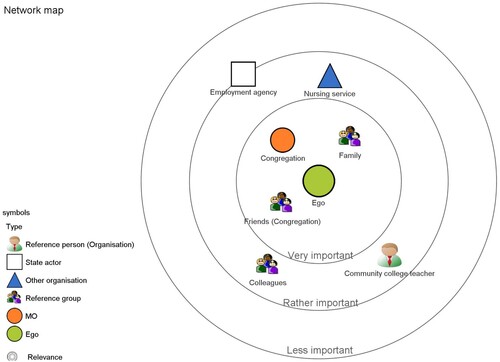

The process of coding and analyzing the data was carried out jointly by the research team consisting of four German researchers. Open and axial coding using MAXQDA served to structure the data and uncover relevant aspects discussed throughout the range of interviews, as well as relationships between emerging codes and categories. We used a combination of theory-driven analysis and inductive coding of the empirical material. Codes and categories were discussed within the team and constantly refined and generalized. In addition to contributing to risk management strategies among their target groups, we discovered various functions that "MOs" performed for different respondents. More specifically, we identified differences in the specific ways people use their organizations and the resources they provide in their approaches to (re)negotiating belongingness alongside processes of adaptation. To develop a better understanding of the linkages between experiences of adaptation and belonging in the context of "MOs", we analyzed a selection of small sequences in particular depth (Amelina Citation2010) and brought in collected ego-centric network charts as visualizations of social networks using VennMaker. Qualitative network analysis as a tool to explore the connectivity between the participation of "migrants" with different actors and places allowed us to investigate the importance participants ascribed to their organizations and individuals within "MOs" for organizing social protection as a key part of their daily life experiences (Bilecen Citation2020). The network charts were used both for data collection and data analysis. During the interviews, participants were asked to allocate actors and organizations that were important to them for their social protection; network charts thus worked as a stimulus to generate narratives. Therefore, analysis of the networks was complemented by qualitative analysis of interview transcripts (Bilecen Citation2020).

Results: finding a sense of belonging in migration

Our findings indicate that organizations founded by and targeted at people with migration biographies can ease dislocation and relocation by offering opportunities to develop familiarity and belongingness in a new context. The resources provided by "MOs" are material as well as symbolic, providing orientation and support within the protected boundaries of a place itself associated with “home”, and promoting connections with various local actors outside of the organization. This way of enabling access to various forms of attachment turns “MOs” into important “anchors”, which directly influence relational embedding processes based on maintaining and (re-)building social networks. In this way, “MOs” ease processes of finding a sense of belonging in migration.

Anchors and homes: “MOs” as distinct spaces of belonging

The empirical analysis draws on theoretical concepts of social anchoring and differentiated embedding. While the former refers to the “footholes which enable migrants to establish stability” (Grzymała-Kazłowska Citation2016, 1133), the latter is defined as the “dynamic temporal, spatial, and relational process” of developing belongingness (Ryan Citation2018, 233). Consequently, we consider anchors both as a result and as a prerequisite for embedding as the process that drives experienced combinations of feeling “at home” and politics of belonging (Antonsich Citation2010). The accounts of participants in our study who had spent various years in Germany illustrate these processes of (re)negotiating belongingness, in which membership in “MOs” becomes an important source of orientation often referred to as “home” in complex encounters with politics of belonging (Boccagni and Hondagneu-Sotelo Citation2021; Barglowski and Bonfert Citation2021). Therefore, the links between anchoring and embedding show how “homemaking” practices can extend beyond the domestic sphere and turn organizations both into anchors and into a “home”. The following accounts illuminate how participants in our research construct their “MOs” into their “homes” as they act as places of stability and predictability and thus as anchors within individual embedding experiences.

Linh’s family fled the Vietnam War and migrated to Germany in the context of a UNHCR agreement in 1980. She was of primary school age when she arrived in Germany. Her young age and smooth inclusion in primary school enabled her to learn German, make friends, finish her vocational training as a hairdresser, and find employment. In the following years, Linh established a family and became involved in the schools and daycare facilities of her children, which offered further opportunities to meet people and participate in the daily life surrounding her. This depiction of Linh’s embedding in a new context based on the drop of various anchors was further promoted by her naturalization as a German citizen, granting her a relatively privileged status and facilitating access to local resources necessary for the further course of embedding. Through her daughter’s daycare facility, she met Tina, the founder of an organization called Culture & Hope.Footnote2 This relatively small registered association offers support for women with a history of migration, especially in the areas of language learning and family counseling. Since Tina invited Linh to join their women’s café, Culture and Hope has become an indispensable place for her to spend her free time, contact others, and exchange various information.

I met Tina, I mean Culture and Hope. And I went to the parents’ breakfast and the international women’s café. And she told us so many things. Therefore, I gained more experience. Before, I was also new and I didn’t know anything. And she told us that there are laws and there are things such as language courses. My mother does not speak German very well. She used to speak German better, but when she moved [here], she rarely had contact with Germans, you know? And she just spent time with Asians. So, I took her to Culture and Hope for elderly women. And my mother also brought other women here who did not speak German. (Linh, 53, from Vietnam)

They do a lot of things for women, like breakfast, too, you know? The international women’s group meets for breakfast every Sunday. And we also just meet occasionally. With friends, for coffee or for a conversation: What are you doing? Things like that. […] This gives them happiness, you know? But also, family conflicts with the daughter-in-law; they talk about those things. So, they try to solve their problems together. (Linh, 53, from Vietnam)

Once, I went to pick up my daughter from Catholic primary school. She was tall for her age, you know? And then they wouldn’t let me in because they thought I was some woman, because my daughter was tall, right? She doesn’t look Asian, because my ex-husband came from Yugoslavia, you know? And he is a Serb. And her nose is high up, nice and all that. Not at all like me. So, they did not let me in. They called the police. And I told them that I am the mother of this child. And they said that you are some woman. […] You are some housekeeper, Philippian, because many Germans have a housekeeper, right? And they did not think they were my children because they are more European, right? Mixed children. They are different. Their eyes are different, their hair is different. My daughter is even blond, too, right? And they say that she doesn’t look like me at all. (Linh, 53 from Vietnam)

This anchoring function of the “MO” is also evident in Linh’s ego-centric network chart, in which state actors and institutional reference persons are complemented not only by family and friends, but also by the “MO” and its staff ().Footnote3 While the first is indicative of embedding in local structures, the second provides a source of orientation in the context of social relationships. This shows that embedding processes are significantly influenced by the ways in which personal relationships facilitate opportunities to renegotiate belongingness in a new environment beyond national “we identities” (Ohnmacht and Yıldız Citation2021).

This role of the “MO” as a key contributor to embedding processes was also evident in other interviews. In contrast to Linh, Anastasia had moved to Germany from Ukraine as an adult at the age of 27, about 20 years before the interview. Like Linh, she built a settled life in Germany where she acquired locally acknowledged qualifications, including language skills and credentials, and formed meaningful relationships. When she arrived in Germany, Anastasia invested a lot of effort in acquiring German language skills that allowed her to participate in the workforce as one of the most important milestones driving her independence and ultimate embedding in the destination context. After she gained financial independence, she divorced her husband and continued to raise her daughter as a single parent. At work, she met supportive colleagues who helped her with various administrative challenges and thus became an important anchor supporting her embedding in Germany. In addition to these local anchors that promote embedding in local structures, one of the key social anchors that allows her to reconstruct a sense of belonging is the Russian congregation.

About this congregation … It’s paramount, I think. For me, the congregation is my mental or spiritual support. […] And why this congregation? A lot is connected to it. Yes? I like our new priest, both priests. Yes, and my family, my sister sometimes comes here and her family, too. And I have many, many, many friends here. Real friends, on whom I can really count when I need help. More like advice, not help, advice. Yes, then one of my friends immediately comes, and we talk and think together about how we can manage this. (Anastasia, 47 from Ukraine)

Finding a sense of belonging in migration is strongly related to social anchors rooted in social relationships, which connote a sense of “home” based on experiences of collectivity and inclusion. While local anchors such as language skills, work placements, local agencies, and citizenship thus indicate embedding with local structures, “MOs” contribute to the process of finding orientation and belongingness in changing environments by facilitating access to relationships of trust and reciprocity. In addition to involvement with local institutions, including schools and work placements, “MOs” complement the range of anchors dropped in this process, especially by providing access to networks. In this way, they become distinct anchors that promote a feeling of being “at home” in themselves (Grzymała-Kazłowska Citation2016; Boccagni and Hondagneu-Sotelo Citation2021). This shows that processes of adapting to changing environments develop in close connection with social networks, as social relationships provide important sources of meaning beyond the national framework (Grzymała-Kazłowska Citation2016; Nancheva and Ranta Citation2022; Keskiner, Eve, and Ryan Citation2022; Ryan Citation2018; Bilecen Citation2020).

Anchoring toward embedding: “MOs” as drivers of belongingness

The accounts above have shown how opportunities to establish and maintain social relationships turn “MOs” into important anchors and thus distinct sources of belonging. In this section, we will show that this association with “MOs” as sources of trust and orientation significantly contributes to the ways in which they facilitate access to additional anchor points and thus consolidate as anchors. As the “MO” is itself embedded in the structural landscape of Germany, occasions to access people, organizations, and institutions thus immediately contribute to the future direction of embedding in local structures. This demonstrates how anchoring and embedding are mutually reinforcing and thus importantly affecting belongingness in a new environment.

This influence of the anchoring function of “MOs” on the embedding process in Germany was evident, for example, in the case of Hoshyar. Hoshyar’s family moved to Germany from Iraq when she was 11 years old, ten years before the interview. Like Linh, Hoshyar's early embedding in the school system allowed her to acquire German language skills and locally acknowledged qualifications early on. In addition to these institutional anchors, she found the relationships she had been able to establish in the context of Path to represent an important source of orientation.

I must say, I had many difficulties in finding an apprenticeship because I finished school and then I had no idea what to do. Where to go. Then I got a letter. Jobcenter. Come, please. Then I went there, and I didn’t know what to do. And then I got help, I would say. But it does not help in the sense that I say: Okay, this really helped me. I wanted something else. I wanted to do an apprenticeship as a pharmaceutical technician. And I got counseling for business management training. And I didn’t know what that was all about, what the difference was. I got help, but I thought I wanted to do something different. Why am I doing this now? And then, there was a woman who always came here [to Path] to the informal gatherings. We talked and she said, “Okay, actually, we need someone in our pharmacy. You can send in your application.” So, I applied. And she had already spoken to the boss. That was extremely helpful. So, as you can see, no matter how you look at it, the association is always there (laughing). (Hoshyar, 21, from Iraq)

About the network we just talked about. Well, they are not necessarily always top jobs or whatever. It is mainly because of the many people who have come here over the past few years, their qualifications are sometimes not acknowledged here. That is why they work in the low-wage sector. They are happy to get anything. And then we get this question: Does anyone know anyone, anywhere, where you can work? They want to work, too. They don't want to be home alone. And then people really appreciate this kind of advice. And in this way, one or the other also found something. (Alexian, 32, parents from Turkey).

This way of facilitating access to local systems and institutions was also described by Najim, whom we met at Lomingo. Najim’s family had left Syria when he was a child. After four years in a refugee camp in Turkey, he and his mother were able to join the rest of the family in Germany. In addition to navigating the new school system and acquiring German language skills, Najim was determined to pursue his dream of becoming a musician. Along this road, Lomingo had become an important anchoring point for him in numerous ways. Najim described how the tutoring sessions organized by the “MO” had an important impact on his successful high school graduation. In addition to easing interactions with the school system, this form of support also helped Najim achieve the necessary qualification for higher education in music. Lomingo also facilitated various opportunities for Najim to engage with his favourite subject by offering music lessons and workshops. Najim also described how specific offers allowed him to engage with topics he had not previously dealt with, like sexuality and family life, which he deems important for navigating his life in Germany.

Everyone benefits from something when they come here [to Lomingo]. They don’t just come here for nothing, they do so many things here and you benefit from them. Even if it is about, for example, I don’t know. They provide counseling for family problems, sexuality, and things like that. When it is about, because, I don’t know, in the culture, where we come from, it’s not so free, you are not allowed to have this freedom like here in Germany. That is why some people don’t really dare say something. Because they are not … because of their families or something. That is why you can also find your way very well here and live your freedom, which I really, really like. And yes, even seminars where you, for example, are against racism, when you experience racism, how to react. You can benefit in many ways (laughing). (Najim, 17, from Syria)

Conclusion

This article emphasized the role of organizations created, led, and targeted at people with migration biographies as key drivers for the development of belonging. While providing a sense of “home”, they also allow access to local anchor points and thus contribute to overall embedding processes in new and changing environments. Rather than promoting isolation and transnational engagement “within” or integration “beyond”, they provide opportunities to build, maintain and expand ties and attachments in unique ways (Erdal and Oeppen Citation2013; Patulny and Svendsen Citation2007; Ryan Citation2011). In this way, they support the agency of people in navigating their social, cultural, and material surroundings during migration and settlement. We have shown that their key contribution to developing experiences of belonging essentially lies in their role as places associated with home, through which they not only affect associations with places of belonging, but also further processes of renegotiating belongingness (Afonso, Barros, and Albert Citation2022) within politics of belonging (Antonsich Citation2010). The concepts of social anchoring (Grzymała-Kazłowska Citation2016) and differentiated embedding (Ryan Citation2018) were useful in highlighting that the ways “MOs” influence opportunities for networking in various spaces significantly affect how people construct and experience belonging, thus challenging binary understandings of adaptation as framed in relation to places of origin or settlement. In this context, “MOs” represent distinct “footholes” (Grzymała-Kazłowska Citation2016) and places called home (Boccagni and Hondagneu-Sotelo Citation2021) that facilitate possibilities for building relationships and mobilizing social capital (Keskiner, Eve, and Ryan Citation2022; Ryan Citation2018). The focus on "MOs" enables theorizations of adaptation experiences “in-between” and beyond ethnic and national collectivities, which resonates with “postmigrant” perspectives and agendas (among others, Ataman et al. Citation2017; Bojadžijev and Römhild Citation2014; in English Ohnmacht and Yıldız Citation2021). Rather than being mutually exclusive, “MOs” thus demonstrate that transnational participation and settling in local contexts of immigration can develop inclusively and collaboratively. This dynamic and non-essentialist understanding of adaptation as a political project has the potential of promoting kinds of progressive inclusion. Therefore, “MOs” take an important transformative role in the development of coherent forms of belonging beyond essentializing notions of ethnicity, nationality, and religion.

Experiences of participants presented in this study resonate with other studies that indicate that people with migration biographies continue to experience othering and challenges to their belonging, indicating hierarchies of privilege and “whiteness” and ongoing processes of the racialization of immigrant populations (see Sime, Käkelä, and Moskal Citation2022). In this context, this study has shown that processes of finding a sense of belonging in migration are strongly shaped by the distinct anchors that facilitate embedding in new social contexts. While prevailing politics of belonging often fail to promote a sense of membership, relationships of trust and support play a key role in the ways people experience embedding inclusively. As “MOs” offer distinct anchor points of stability and belonging based on meaningful relationships, they contribute to inclusive experiences of embedding of this kind. Furthermore as integral parts of both transnational communities and the local institutional landscape, “MOs” engage in political projects to shape new understandings of ethnicity, national cohesion, and belonging. Therefore, they have the potential to advance new interpretations of collectivities “beyond” rigid boundaries and national or ethnic “we identities” (Ohnmacht and Yıldız Citation2021). In addition to their importance to individuals, they thus have an innovative potential for promoting new understandings of cohesion and diversity that will provide important venues for further research to fully grasp their differentiated embedding in the institutional landscapes of immigrant societies and beyond.

Ethics statement

The study underlying this article includes human research participants, which was prospectively approved by the legal office of the Technical University Dortmund at the outset of the research project. Before each interview, we obtained informed written consent from all participants involved in this research, which included extended information about the goal of the research, legal information about their data protection rights as well as our approaches to collecting and managing data. Ethical approval for this study was not mandatory.

Acknowledgements

Findings presented in this paper stem from the collaborative research project “MIKOSS. Migrant organizations and the co-production of social protection” generously funded by the Mercator Research Center Ruhr (MERCUR). We are very grateful to our collaborators from the University of Duisburg-Essen and the Ruhr-University Bochum for their cooperation and support. We also want to express our appreciation to participants in this research who generously shared their stories with us. In addition, we wish to thank two anonymous reviewers for their useful and constructive comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 While the term “migrant organization” is still frequently used, it is also heavily criticized for a variety of reasons, including the difficulties in determining who is a ‘migrant’, and the fact that it is albeit not always used by organizations themselves who might externally be labelled a MO. Therefore, we choose to put the term in quotation marks and use it to refer more broadly to groups of people with migration biographies, who formally organize as registered organizations or associations with the goal to address other people with migration biographies.

2 All organizations involved in our research received pseudonyms for this article.

3 Ego-centric network charts used to illustrate participants‘ networks in this article were collected in the context of the research project on the role of migrant organizations for social protection. During the interviews, the name generator specifically asked for people and (institutional) relationships participants associated with their own social protection.

References

- Achbari, W. 2015. “Bridging and Bonding Ethnic Ties in Voluntary Organisations: A Multilevel ‘Schools of Democracy’ Model.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (14): 2291–2313. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2015.1053851.

- Afonso, J. D., S. Barros, and I. Albert. 2022. “The Sense of Belonging in the Context of Migration: Development and Trajectories Regarding Portuguese Migrants in Luxembourg.” Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science, 1–29. doi:10.1007/s12124-022-09721-4.

- Amelina, A. 2010. “Searching for an Appropriate Research Strategy on Transnational Migration: The Logic of Multi-Sited Research and the Advantage of the Cultural Interferences Approach.” Forum: Qualitative Social Research 11 (1). doi:10.17169/fqs-11.1.1279.

- Amelina, A. 2021. “After the Reflexive Turn in Migration Studies: Towards the Doing Migration Approach.” Population, Space and Place 27 (1). doi:10.1002/psp.2368.

- Amelina, A. 2022. “Knowledge Production for Whom? Doing Migrations, Colonialities and Standpoints in non-Hegemonic Migration Research.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 45 (13): 2393–2415. doi:10.1080/01419870.2022.2064717.

- Amelina, A., K. Horvath, and B. Meeus. 2016. An Anthology of Migration and Social Transformation. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Antonsich, M. 2010. “Searching for Belonging - An Analytical Framework.” Geography Compass 4 (6): 644–659. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8198.2009.00317.x.

- Arhin-Sam, K. 2019. Return Migration, Reintegration and Sense of Belonging. Nomos.

- Ataman, F., M. El, J. M. R. Lehmann, and G. Tank. 2017. “Neue Deutsche Organisationen.” Forschungsjournal Soziale Bewegungen 30 (3): 109–111. doi:10.1515/fjsb-2017-0069.

- Barglowski, K. 2019. Cultures of Transnationality in European Migration: Subjectivity, Family and Inequality. Routledge.

- Barglowski, K. 2021. “Transnational Parenting in Settled Families: Social Class, Migration Experiences and Child Rearing Among Polish Migrants in Germany.” Journal of Family Studies, 1–18. doi:10.1080/13229400.2021.2007786.

- Barglowski, K., and L. Bonfert. 2021. “Migrant Organisations, Belonging and Social Protection. The Role of Migrant Organisations in Migrants’ Social Risk-Averting Strategies.” International Migration, online first.

- Bäßler, K. 2013. Kulturelle Bildung in der Migrationsgesellschaft: Migrantenorganisationen als Akteure und Impulsgeber. Kulturelle Bildung Online. https://www.kubi-online.de.

- Bilecen, B. 2020. “Personal Network Analysis from an Intersectional Perspective: How to Overcome Ethnicity Bias in Migration Research.” Global Networks 21: 470–486. doi:10.1111/glob.12318.

- Boccagni, P., and P. Hondagneu-Sotelo. 2021. “Integration and the Struggle to Turn Space into “Our” Place: Homemaking as a Way Beyond the Stalemate of Assimilationism vs Transnationalism.” International Migration. doi:10.1111/imig.12846.

- Böhmer, M. 2012. Bericht der Beauftragten der Bundesregierung für Migration, Flüchtlinge und Integration über die Lage der Ausländerinnen und Ausländer in Deutschland.

- Bojadžijev, M., and R. Römhild. 2014. “Was Kommt Nach dem “Transnational Turn“? Perspektiven für Eine Kritische Migrationsforschung.” In Vom Rand ins Zentrum. Perspektiven Einer Kritischen Migrationsforschung Herausgegeben vom Labor Migration. Panama Verlag.

- Bonfert, L., E. Günzel, A. Kellmer, K. Barglowski, U. Klammer, S. Petermann, L. Pries, and T. Schlee. 2022. “Migrantenorganisationen und soziale Sicherung.” IAQ Report, Universität Duisburg-Essen. doi:10.17185/duepublico/77027.

- D'Angelo, A. 2015. “Migrant Organisations: Embodied Community Capital?” In Migrant Capital: Networks, Identities and Strategies, edited by L. Ryan, U. Erel, and A. D'Angelo, 83–101. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Dijkzeul, D., and M. Fauser. 2020. “Introduction: Studying Diaspora Organizations in International Affairs.” In Diaspora Organizations in International Affairs, edited by D. Dijkzeul and M. Fauser. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Easton-Calabria, E., and Y. Alaous. 2022. Belonging in Berlin: An Exploration of Syrian Refugee-led Organisations and Volunteerism during COVID-19.

- Erdal, M. B. 2020. “Theorizing Interactions of Migrant Transnationalism and Integration Through a Multiscalar Approach.” Comparative Migration Studies 8 (1). doi:10.1186/s40878-020-00188-z.

- Erdal, M. B., and C. Oeppen. 2013. “Migrant Balancing Acts: Understanding the Interactions Between Integration and Transnationalism.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 39 (6): 867–884. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2013.765647.

- Faist, T. 2020. “Beyond National and Post-National Models: Transnational Spaces and Immigrant Integration.” In New Horizons in Sociological Theory and Research, 277–312. Routledge.

- Grzymała-Kazłowska, A. 2016. “Social Anchoring: Immigrant Identity, Security and Integration Reconnected?” Sociology 50 (6): 1123–1139. doi:10.1177/0038038515594091.

- Halm, D., and M. Sauer. 2022. “Cross-Border Structures and Orientations of Migrant Organizations in Germany.” Journal of International Migration and Integration. doi:10.1007/s12134-021-00927-w.

- Halm, D., M. Sauer, S. Naqshband, and M. Nowicka. 2020. Wohlfahrtspflegerische Leistungen von säkularen Migrantenorganisationen in Deutschland, unter Berücksichtigung der Leistungen für Geflüchtete. Nomos Verlag.

- Hoesch, K. 2018. “Migrationspolitiken und -Diskurse in Historischer Perspektive.” In Migration und Integration. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Hunger, U., and M. Candan. 2014. “Politisches Engagement von Migranten in Vereinen und Verbänden.” Forschungsjournal Soziale Bewegungen 27 (4): 137–141. doi:10.1515/fjsb-2014-0417.

- Joppke, C., and E. Morawska. 2003. “Integrating Immigrants in Liberal Nation-States: Policies and Practices.” In Toward Assimilation and Citizenship: Immigrants in Liberal Nation-states, edited by C. Joppke and E. Morawska, 1–36. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Keskiner, E., M. Eve, and L. Ryan. 2022. Revisiting Migrant Networks. Migrants and Their Descendants in Labour Markets. Springer.

- Korteweg, A. C. 2017. “The Failures of 'Immigrant Integration': The Gendered Racialized Production of Non-belonging.” Migration Studies 5 (3): 428–444. doi:10.1093/migration/mnx025.

- Levitt, P. 2004. “Redefining the Boundaries of Belonging: The Institutional Character of Transnational Religious Life.” Sociology of Religion 65 (1): 1–18. doi:10.2307/3712504.

- Nancheva, N., and R. Ranta. 2022. “Do They Need to Integrate? The Place of EU Citizens in the UK and the Problem of Integration.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 45 (10): 1983–2003. doi:10.1080/01419870.2021.1977363.

- Neue Deutsche Organisationen. 2022. https://neuedeutsch.org. Retrieved September 30, 2022, from https://neuedeutsche.org/de/ueber-uns/wer-wir-sind-was-wir-wollen/.

- Nowicka, M., and S. Vertovec. 2014. “Comparing Convivialities: Dreams and Realities of Living-with-difference.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 17 (4): 341–356. doi:10.1177/1367549413510414.

- Ohnmacht, F., and E. Yıldız. 2021. “The Postmigrant Generation Between Racial Discrimination and New Orientation: From Hegemony to Convivial Everyday Practice.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 44 (16): 149–169. doi:10.1080/01419870.2021.1936113.

- Papadopoulos, A. G., and L. M. Fratsea. 2022. “Aspirations, Agency and Well-Being of Romanian Migrants in Greece.” Population, Space and Place, e2584. doi:10.1002/psp.2584.

- Patulny, R., and G. L. H. Svendsen. 2007. “Exploring the Social Capital Grid: Bonding, Bridging, Qualitative, Quantitative.” International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 27 (1/2): 32–51. doi:10.1108/01443330710722742.

- Pries, L., and Z. Sezgin. 2012. Cross Border Migrant Organizations in Comparative Perspective. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Putnam, R. D. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. Simon & Schuster Paperbacks.

- Ryan, L. 2011. “Migrants’ Social Networks and Weak Ties: Accessing Resources and Constructing Relationships Postmigration.” The Sociological Review 59 (4): 707–724. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.2011.02030.x.

- Ryan, L. 2018. “Differentiated Embedding: Polish Migrants in London Negotiating Belonging Over Time.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (2): 233–251. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1341710.

- Schapendonk, J., M. Bolay, and J. Dahinden. 2021. “The Conceptual Limits of the ‘Migration Journey’. De-Exceptionalising Mobility in the Context of West African Trajectories.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (14): 3243–3259. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2020.1804191.

- Schultze, G., and D. Thränhardt. 2013. Migrantenorganisationen. Engagement, Transnationalität und Integration. Bonn: FES.

- Sime, D., N. Tyrrell, E. Käkelä, and M. Moskal. 2022. “Performing Whiteness: Central and Eastern European Young People’s Experiences of Xenophobia and Racialisation in the UK Post-Brexit.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, doi:10.1080/1369183X.2022.2085678.

- Snel, E., Ö Bilgili, and R. Staring. 2021. “Migration Trajectories and Transnational Support Within and Beyond Europe.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (14): 3209–3225. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2020.1804189.

- Sultan, M. M., N. Friedrichs, and K. Weiss. 2019. Anerkannte Partner - Unbekannte- Unbekannte Größe? Migrantenorganisationen in der deutschen Einwanderungsgesellschaft. [Accepted partners, unknown players? Migrant organizations in Germany‘s immigration society] Berlin (SVR).

- SVR. 2020. “Vielfältig engagiert – breit vernetzt – partiell eingebunden? Migrantenorganisationen als gestaltende Kraft in der Gesellschaft. [Diversely Engaged, Broadly Networked - Partially Integrated? Migrant Organisations as a Shaping Force in Society].” Sachverständigenrat Deutscher Stiftungen Für Integration und Migration 2.

- Thränhardt, D. 1989. “Patterns of Organization among Different Ethnic Minorities.” New German Critique 46: 10–26. doi:10.2307/488312.

- Thränhardt, D. 2013. “Migrantenorganisationen, Engagement, Transnationalität und Integration.” In Migrantenorganisationen, Engagement, Transnationalität und Integration, edited by G. Schultze, and D. Thränhardt. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.

- Yuval-Davis, N. 2010. “Theorizing Identity: Beyond the ‘Us’ and ‘Them’ Dichotomy.” Patterns of Prejudice 44 (3): 261–280.