ABSTRACT

This introduction explains the existence of a little-known Iberia that was more racially and ethnically diverse than described in domestic narratives. The special issue builds an early late modern and contemporary Afro-Iberian history. It approaches African and Maghrebi experiences and memories in order to explain the close relation between race, class, ethnicity and gender in Portugal and Spain between 1850 and 2021.

Building an early late modern and contemporary Afro-Iberian history

This special issue seeks to augment the scant knowledge of the African presence in the Iberian Peninsula by identifying and documenting the traces of these population groups which I name “Afro-Iberian” in two different periods. First, the time of effective Spanish and Portuguese colonization in Africa (Cervelló Citation2013; Pinhal Citation2017; Telo and de la Torre Citation2000; Torre Gómez Citation2000). Second, the period from the colonial independences until 2021 (Aixelà-Cabré Citation2020; Martín-Díaz and Cuberos-Gallardo Citation2022; Sardinya Citation2009; Sipi Citation2010; Vi-Makome Citation2000; Vala, Lopes, and Lima Citation2008). It aims to explain the existence of a little-known contemporaneous Iberia that was more racially and ethnically diverse than described in domestic narratives (Hertel Citation2015; Ramalho Citation2017; Sánchez Gómez Citation2006). Indeed, the legacy of an Afro-Iberian and Maghrebi minority is notable in the social, cultural and artistic contexts. See and .

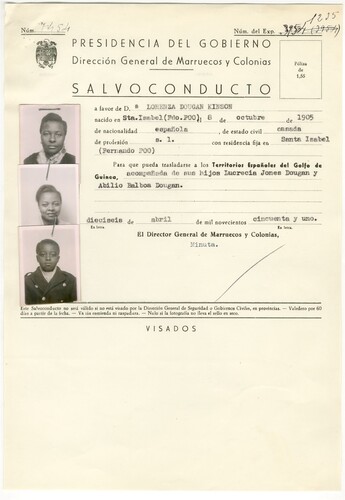

Figure 1. Safe-conduct to travel between Fernando Poo and the Iberian Peninsula, 1951. Archivo General de la Administración (AGA), box 81/08349.

Figure 2. Equatorial Guinean youths summering as part of the Organización Juvenil Española (Spanish Youth Organisation, OJE) passing through Tenerife. Tenerife, 25 July 1964. Archivo General de la Administración (AGA), box, 3 (82) F/ 01311, envelope 45.

Using documentary archives, oral history and ethnography the researchers reconstruct a contemporaneous Afro-Iberia that remains without a history, either because the memories of black and Maghrebi experience were handed down orally, or because they were subalternised groups who were unable to recount it. This collective work thus fills gaps in Afro-Iberian and Maghrebi memory by reviewing the consideration given in the case studies to issues like race, ethnicity and gender (Crenshaw Citation1995; Goldberg Citation2006; Stolcke Citation1992; Stoler Citation1991). To do this, the researchers use a post-decolonial study approach, starting from the basis that colonialism and coloniality were the determining factors (Cooper Citation2005; Grosfoguel Citation2012; Lorcin Citation2015; Mbembe Citation2001; Mignolo Citation2011; Mudimbe Citation1988; Quijano Citation2014) in facilitating the arrival of Africans and Maghrebis in Spain and Portugal and conditioned their empowerment and social participation into the metropolis. After African colonial independences, migration channels to Iberian countries increased, but these groups did not become socially and culturally visible until Afro-descent activists started making political demands.

In this special issue, we support that the African traces in the Iberian Peninsula draw the Afro-Iberian and Maghreb-Iberian mosaic that mediated between the modern age and the establishment of the democratic systems of Spain and Portugal. This legacy must be recovered to enrich the African and North African history of the Iberian Peninsula, since it is through “shared history” (Aixelà-Cabré Citation2022a) that a deep-rooted racism and xenophobia can be combated (Goldberg Citation2009), which, even today, is colonial based and changes over time (Goldberg Citation2006).

The issue is urgent because at the beginning of the twenty-first century, the “Afro” and Maghrebi claim in the Iberian Peninsula is seeking visibility and empowerment strategies as minorities, in the face of the taciturn silence of Portugal and Spain, which are unable to address their colonial past with the African continent (Cardina and Martins Citation2019), and the place must hold African and North African groups in the Iberian collective imaginary, since their historical invisibility in the peninsula continues (Castro Henriques Citation2009, Citation2011).

Unity and diversity in the Afro-Iberian histories

As Resina (Citation2009) stated, the Iberian enables a geographical, theoretical and methodological approximation from a comparative and multidimensional perspective. This special issue is based on the premise that the Iberian has maintained a certain unity in several historical moments, such as the colonial period (Stucki Citation2019) or the dictatorial period (Pena Rodríguez Citation2017). The Iberian unit would show practices and even common methodological principles (Pérez Isasi Citation2017) with such an extensive breadth that within Iberian Studies it is possible to study Iberian cultures, such as Catalan (Resina Citation2009), Spanish and Portuguese national identities (Flynn Citation2001), the construction of the Iberian gender (Buffery, Davis, and Hooper Citation2007), the Iberian historical and ethnographic convergence (Alcantud, Antonio, and Velasco Citation2022; Fernández Sebastián Citation2021) Iberian literature (Domínguez, Abuín, and Sapega Citation2015), or even the similarities in the presentation of colonial otherness as an Iberian legacy (Garrido-Castellano and Leitão Citation2022).

Thus, the comparison between Spain and Portugal is pertinent and significant, first, because this area of Western Europe was quite peripheral during the 19th and 20th centuries, despite having been a pioneer in the European colonial expansion of the fifteenth century (Yun-Casalilla Citation2019), which it has been reflected in the absence of comparative studies with other European colonialisms (Colmeiro and Martínez-Expósito Citation2019). Second, because this marginality with respect to the countries that capitalized on studies in Africa and Asia -British, French, Dutch colonization, and to a lesser extent the Portuguese-, made the Iberian collaborations and the Spanish case especially invisible, which ended up substantiating a generalized apathy to study Iberian specificities (Aixelà-Cabré and Rizo Citation2023). The colonial past is reflected in the collective memories of the European powers, as Buettner (Citation2016) asserts, and as it still seems that it could provoke the vindication of the “discovery” of the “new world” of Spanish and Portuguese explorers in Iberian memories, given how popular it has been for the Portuguese and Spanish to have colonies (Cervelló Citation2013; Delgado Citation2014).

For all these reasons, the selection of the Spanish and Portuguese cases is solid. On the one hand, because it allows us to understand certain postcolonial traces. On the other, because both had dictatorial political systems throughout the twentieth century that were replaced by democratic systems almost simultaneously, which makes it possible to compare two rhetoric about Africanity and the Maghreb with different experiences and historical ties, but with numerous elements of common history, such as, for example, that dictatorships were established with similar narratives of race (Cleminson Citation2022), and Hipanotropicalism and Lusotropicalism that spread to some colonized African and North African countries (Martín Márquez Citation2011).

The project of studying the African and North African legacy from 1850 to 2021 is therefore imperative to identify the exoticization of Africanness that would have occurred in Spain and Portugal, and to demystify it. And it would seem that the African and North African presence in Spain and Portugal, during the period studied, went from being an exceptional presence, to constituting certain minorities from the 1950s, very dispersed, little cohesive and lacking in power, unless the powerful Fernandino diaspora settled in Catalonia since the last quarter of the nineteenth century.

In order to say that African presence in Spain and Portugal at the end of the nineteenth century and beginning of the twentieth century has been studied by human zoos and universal exhibitions. These experiences have constituted examples of the way Iberian countries racialized differences, devalued cultures and fixed primitiveness on populations to justify European colonization in Africa. In these episodes, gender analysis was mostly invisible given that African women were a minority and interest by researchers was not always retained. Also in twentieth century, those Africans who participated in the First and Second World War would be studied (García Balañà Citation2019), which in Spain meant that Franco incorporated Rifians into the rebel side during the Spanish Civil War (Jensen Citation2016).

Our interest is to weave together two stories in parallel that are little known and are enormously fragmented: the similarities and differences in the social participation of Africans in Spain and Portugal; the degree of influence that the sociopolitical framework has had on Afro-Iberian coexistence and visibility; and the degree of historical depth that Iberian notions have about what is African. The comparison will also allow the analysis of the similarities and differences between the narratives and practices of African otherness of two Western European countries marked by twilight overseas empires, favoring rereadings of common Iberian-African and Afro-Iberian historical recognition. Likewise, the dossier also constitutes a laboratory to promote the study of other unknown experiences of Africans in Europe that may allow in the future critical comparisons on the construction of what is Euro-African and Afro-European (Bischoff and Engel Citation2013; Aixelà-Cabré Citation2022b).

Approaches to Afro-Iberian experiences and memories

As Sawyer and Habel (Citation2014) found that there were certain regional coincidences in the presence of the black diaspora in the Nordic countries, most of the articles show certain dynamics in the Iberian Peninsula. Drawing upon Cultural Studies, Anthropology, History, Sociology, Literary Studies and Philology, this interdisciplinary special issue presents definitive results of the R + D Project Afro-Iberia.

Arbaiza opens this special issue studying Africans in Iberia during the early late modern period. Her work “Shifting Representations, Ambiguous Bodies: African Colonial Subjects in Nineteenth Century Spain” examines the racial politics around African colonial subjects in Spain between the 1840s and the 1880s. Developed based on archival and documentary material (travel narratives, newspapers or chronicles), Arbaiza (Citation2023) poses the different processes of racialization to which some braceros (krumanes) brought to the metropolis were subjected. The study reveals that Spanish interests were based on the Hispanization of Spanish Guinea, which was the only Spanish colony in sub-Saharan Africa, enabling us to reconstruct Spanish narratives about Africa in the second half of the nineteenth century.

The special issue continues with two articles that study the African presence in the Iberian peninsula from a gender perspective. On the one hand, Aixelà-Cabré’s text (Citation2023) on “African Women in Iberia. The Fernandino Elite in Barcelona” introduces the role played by some powerful African women from the nineteenth century, showing how this elite subverted Iberian images on Africans until the 1990s. The study offers a decolonial herstory that explains how the Fernandino community broke the race, class and gender molds of Spanish colonialism both in the colony and the metropolis. The analysis based on documentary and oral sources allows some qualities of the Fernandino collective to surface, such as its Afropolitanism, transcontinentalism and multi-sited residence. However, the article ends by explaining how the decline in power of this African bourgeoisie would fuel a deafening silence about its establishment in Barcelona.

On the other hand, Falconi’s article (Citation2023) “African Women’s Trajectories and the Casa dos Estudantes do Império” compares different women's trajectories that crossed this institution in Lisbon, given that women’s role remain still under-explored. The text is of great interest as it analyzes the period between 1944 and 1975. These understudied decades in the scarce historiography have compiled the African presence in Portugal, especially with regard to the presence of women. Therefore, Falconi’s research allows us to deconstruct the national narrative of an essentially white and European Portugal, which has systematically excluded Africans and people of African descent, even more so if it proceeded from women.

The Afro-Iberian imprints in arts are explored by García, and Raposo and Garrido-Castellano. García’s work (Citation2023) “Black Extras and Actors in Francoist Cinema” reconstructs the unnoticed presence of Africans in Spanish filmography during this period, leaving simplistic approaches behind. The article is highly interesting as it shows how Spanish cinema throughout the Franco regime gradually expanded to other genres and topics. This fact filtered into the racial rhetoric that swung between Spanish exoticism and orientalized Spain, and the rejection to racial ambiguity protected by discourses of blood purity. Meanwhile, Raposo and Castellano (Citation2023) offer their research “Batida and the Politics of Sonic Agency in Afro-Lisboa” where they put in relation the Afro-Portuguese Djs sonic archive with cultural creativity and racial affirmation in Portugal. The research recalls that Portugal is a country that has reinvented itself after the migratory flows in the 1980s. It emerged as a multicultural country with a capital city that is a dynamic focal point as Afro-Lisbon. In their opinion, the Lusotropicalist rhetoric used to protect racial politics was very valuable. Raposo and Garrido-Castellanos show how these policies made the black African presence invisible, as well as the effects of racism in the reproduction of racial inequalities, with Afro-diasporic music and beats being the way in which racialized European citizens have appropriated the social networks and digital tools to challenge Portuguese lusotropical reconfigurations.

The way colonialities worked for Africans in the Iberian peninsula are studied by Rizo and Persánch. Rizo (Citation2024) in her article “Leandro Mbomio, the “Black Picasso”: Spanish State Propaganda, Blackness, and Neocolonialism in Equatorial Guinea” researches the Spanish political interests that were behind the figure of the Equatorial Guinean sculptor Leandro Mbomio. Unlike other cases reviewed in this special issue on the arrival of students to the Iberian Peninsula (Arbaiza Citation2023; Falconi Citation2023), Mbomio included black African people in the narrative of Hispanicity at a very delicate political moment in which the late-Franco government sought to legitimize itself internationally while silencing the enormous violence that had been unleashed in the newly independent Equatorial Guinea. Persánch’s article (Citation2023) “Racial Rhetoric in Black and White: Situational Whiteness in Francoist Equatorial Guinea through Misión blanca” studies under the lens of whiteness the interactions of the Africans characters of the Spanish film. He considered the rise in studies on whiteness in the Iberian Peninsula as an opportunity to expand studies both from a geographical and contextual perspective. He regarded them as an opportunity to analyze discourses on whiteness from a post-imperial Hispanic and Lusophone point of view that connects America and Africa with old Catholic Europe.

Finally, two articles make visible contemporary Afro-Iberia approaching how racialized communities activate strategies to subvert minorization. On the one hand, the work of Moreras (Citation2023) “Precarious Lives, Invisible Deaths. A History of Community Funeral Management among Moroccans in Catalonia” approaches how deaths have been managed within Moroccans in Catalonia. The 250-file study on deceased Moroccans from the Moroccan Consulate in Barcelona provides valuable information that creates a socio-economic puzzle from an unknown period in order to understand the changes in the Moroccan community in Catalonia. The research confirms early racism in Catalan society which, in his opinion, continues to be the basis of the negative image of people of Moroccan origin in Catalonia. On the other hand, Grau-Rebollo, García-Tugas, and García-García (Citation2023) in their article “Induced Vulnerability: The Consequences of Racialization for African Women in an Emergency Shelter in Catalonia (Spain)” highlight the cultural strategies of Maghrebin and African women in the care services for battered women. The research displays inadequate staff training in terms of cultural differences, as well as the lack of understanding of the women cared for in the service regarding cultural forms of organization and care which are different from their own. All of this generates an additional vulnerability in shelters. As highlighted, there is a confluence between structural fragility, uprooting and the lack of emotional ties, as perfectly explained in this research.

All the articles make it possible to begin the difficult task of solving a puzzle that accounts for the African and Maghrebi traces in Iberia. I am aware that this is a first approach which is very much incomplete, but we must appreciate that reversing centuries of African and Maghrebi invisibilization and minoritization is not an easy or quick task.

The ultimate goal of this special issue is to sketch out an innovative Afro-Iberian mosaic that puts forgotten memories and histories into circulation that can contribute to constructing an Afro-Iberian past that is critical of the cultural racialization of Spaniards and Portuguese while providing historical reference points for an Afro-Iberian community seeking legitimation in the twenty-first century.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aixelà-Cabré, Yolanda. 2020. “The Presence of the Colonial Past: Equatorial Guinean Women in Spain.” Itinerario. Journal of Imperial and Global Interactions 44 (1): 140–158. https://doi.org/10.1017/S016511532000008X.

- Aixelà-Cabré, Yolanda. 2022a. Spain’s African Colonial Legacies: Morocco and Equatorial Guinea Compared. Leiden: Brill.

- Aixelà-Cabré, Yolanda. 2022b. Africanas en África y Europa (1850-1996). Barcelona: Edicions Bellaterra.

- Aixelà-Cabré, Yolanda. 2023. “African Women in Iberia. The Fernandino elite in Barcelona.” Ethnic and Racial Studies. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2023.2289145.

- Aixelà-Cabré, Yolanda, and Elisa Rizo, eds. 2023. Afro-Iberia (1850-1975). Enfoques teóricos y huellas africanas y magrebíes en la península ibérica. Barcelona: Bellaterra Edicions.

- Alcantud, González, José Antonio, and Pablo Gonzalez Velasco, eds. 2022. El nuevo Iberismo. Iberia redescubierta. Córdoba: Almuzara.

- Arbaiza, Diana. 2023. “Shifting Representations, Ambiguous Bodies: African Colonial Subjects in Nineteenth Century Spain.” Ethnic and Racial Studies. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2023.2289151.

- Bischoff, Eva, and Elisabeth Engel. 2013. “Colonialism and Beyond. Race and Migration from a Postcolonial Perspective.” In Colonialism and Beyond. Race and Migration from a Postcolonial Perspective, edited by Engel Bischoff, 3–19. Wien: Lit.

- Buettner, Elisabeth. 2016. Europe after Empire: Decolonization, Society and Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Buffery, Helena, Stuart Davis, and Kirsty Hooper. 2007. Reading Iberia: Theory / History / Identity. Oxford: Peter Lang.

- Cardina, Miguel, and Bruno Sena Martins. 2019. “Memorias cruzadas de la guerra colonial portuguesa y las luchas de liberación africanas: del imperio a los Estados poscoloniales.” Endoxa 44: 113–134. https://doi.org/10.5944/endoxa.44.2019.24347.

- Castro Henriques, Isabel. 2009. A Herança Africana em Portugal – Séculos XV-XX. Lisboa: CTT-Correios de Portugal.

- Castro Henriques, Isabel. 2011. Os Africanos em Portugal. História e Memória Séculos XV-XXI. Lisboa: Comité Português do Projecto Unesco «A Rota do Escravo».

- Cervelló, Josep. 2013. “La interacción luso-española en la descolonización africana.” Espacio, tiempo y Forma 25: 153–190.

- Cleminson, Richard. 2022. “Race in Iberia and Latin America.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 45 (13): 2486–2490. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2022.2095220.

- Colmeiro, José, and Alfredo Martínez-Expósito, eds. 2019. Repensar los estudios ibéricos desde la periferia. Venezia: Edizioni Ca’ Foscari.

- Cooper, Frederick. 2005. Colonialism in Question. Theory, Knowledge, History. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé. 1995. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics and violence Against Women of Color.” In Critical Race Theory. The key writings that formed the movement, edited by Crenshaw, Cotanda, Peller and Thomas, 357–383. New York: The New Press.

- Delgado, Luisa Elena. 2014. La Nación Singular. Madrid: Siglo XXI.

- Domínguez, César, Anxo Abuín, and Ellen Sapega, eds. 2015. A Comparative History of the Literature of the Iberian Peninsula. Ámsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Falconi, Jessica. 2023. “African Women’s Trajectories and the Casa dos Estudantes do Império.” Ethnic and Racial Studies. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2023.2289141.

- Fernández Sebastián, Javier. 2021. Historia conceptual en el Atlántico ibérico. Lenguajes, tiempos, revoluciones. Madrid: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

- Flynn, M. K. 2001. “Constructed identities and Iberia.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 24 (5): 703–718. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870120063945.

- García, Mar. 2023. “Black Extras and Actors in Francoist Cinema.” Ethnic and Racial Studies. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2023.2289136.

- García Balañà, Albert. 2019. “‘No hay ningún soldado que no tenga una negrita’. Raza, género, sexualidad y nación en la experiencia metropolitana de la guerra colonial (Cuba, 1895–1898).” In Vivir la nación. Nuevos debates sobre el nacionalismo español, edited by Miralles, 153–186. Granada: Comares.

- Garofalo, Leo J. 2017. “Afro-Iberians in the Early Spanish Empire, ca. 1550–1600.” In Global Africa: Into the Twenty-First Century, edited by Hodgson, and Byfield, 39–48. Berkeley: Berkeley University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520962514-007.

- Garrido-Castellano, Carlos, and Bruno Leitão. 2022. “Introduction. Fictions of Cosmopolitanism, Spectacles of Alterity.” In Curating and the Legacies of Colonialism in Contemporary Iberia, edited by Leitão Garrido-Castellano, 1–21. Wales: University of Wales Press.

- Goldberg, David Theo. 2006. “Racial Europeanization.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 29 (2): 331–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870500465611.

- Goldberg, David Theo. 2009. “Racial Comparisons, Relational Racisms: Some Thoughts on Method.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 32 (7): 1271–1282. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870902999233.

- Grau-Rebollo, Jorge, Lourdes García-Tugas, and Beatriz García-García. 2023. “Induced Vulnerability: The Consequences of Racialization for African women in an Emergency Shelter in Catalonia (Spain).” Ethnic and Racial Studies. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2023.2289135.

- Grosfoguel, Ramón. 2012. “Islamofobia epistémica y ciencias sociales coloniales.” In La islamofobia a debate, edited by Grosfoguel Martín, 47–60. Madrid: Casa Árabe.

- Hertel, Patricia. 2015. The Crescent Remembered. Islam and Nationalism on the Iberian Peninsula. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press.

- Jensen, Geoffrey. 2016. “Muslim soldiers in a Spanish Crusade: Tomás García Figueras, Mulai Ahmed er Raisuni and the Ideological Context of Spain’s Moroccan soldiers.” In Colonial Soldiers in Europe (1914-1945), edited by Storm and Al Tuma, 182–206. London: Routledge.

- Lorcin, Patricia. 2015. “France’s Nostalgias from Empire.” In French Politics in an Age of uncertainity, edited by Chabal, 143–171. London: Bloomsbury.

- Martín-Díaz, Emma, and Francisco Cuberos-Gallardo. 2022. “The Reconfiguration of Nationalist Movements in a Context of Crisis: Evidence from the Case of Catalonia.” Interventions 24 (2): 284–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369801X.2020.1863836.

- Martín Márquez, Susan. 2011. Desorientaciones. El colonialismo español en África y la performance de identidad. Barcelona: Bellaterra.

- Mbembe, Achille. 2001. On the Postcolony. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Mignolo, Walter. 2011. The Darker Side of Western Modernity: Global Futures, Decolonial Options. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Moreras, Jordi. 2023. “Precarious Lives, Invisible Deaths. A History of Community Funeral Management among Moroccans in Catalonia.” Ethnic and Racial Studies. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2023.2289148.

- Mudimbe, Valentin Yves. 1988. The Invention of Africa: Gnosis, Philosophy, and the Order of Knowledge. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; London: James Currey.

- Pena Rodríguez, Alberto. 2017. Salazar y Franco. La alianza del fascismo ibérico contra la España republicana: diplomacia, prensa y propaganda. Gijón: Trea.

- Pérez Isasi, Santiago. 2017. “Los Estudios Ibéricos como estudios literarios: algunas consideraciones teóricas y metodológicas.” In Procesos de nacionalización e identidades en la península ibérica, edited by Rina, 347–361. Cáceres: Universidad de Extremadura.

- Persánch, J. M. 2023. “Racial Rhetoric in Black and White: Situational Whiteness in Francoist Equatorial Guinea through Misión blanca.” Ethnic and Racial Studies. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2023.2289152.

- Pinhal, Cindy. 2017. Forgetting the Forgetfulness: (Dis)remembering the Coloniality of the Portuguese and Spanish Dictatorships. San Diego: University of California.

- Quijano, Anibal. 2014. “Colonialidad del poder y clasificación social.” In Epistemologías del Sur (Perspectivas), edited by Meneses Sousa, 67–107. Madrid: Akal.

- Ramalho, Víctor (coord.). 2017. Casa dos Estudantes do Império: 50 anos. Testemunho, vivências, documentos. Lisboa: UCCLA.

- Raposo, Otávio, and Carlos Garrido Castellano. 2023. “Batida and the Politics of Sonic Agency in Afro-Lisboa.” Ethnic and Racial Studies. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2023.2289154.

- Resina, Joan Ramon. 2009. Del hispanismo a los estudios ibéricos. Una propuesta federativa para el ámbito cultural. Madrid: Biblioteca Nueva.

- Rizo, Elisa G. 2024. “Leandro Mbomio, the “Black Picasso”: Spanish State Propaganda, Blackness, and Neocolonialism in Equatorial Guinea.” Ethnic and Racial Studies. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2023.2295481.

- Sánchez Gómez, Luís Ángel. 2006. “África en Sevilla: la exhibición colonial de la Exposición Iberoamericana de 1929.” Hispania (Madrid, Spain 66 (224): 1045–1082. https://doi.org/10.3989/hispania.2006.v66.i224.29.

- Sardinya, João. 2009. Immigrant Associations, Integration and Identity. Angolan, Brazilian and Eastern European Communities in Portugal. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Sawyer, Lena, and Ylva Habel. 2014. “Refracting African and Black diaspora through the Nordic region.” African and Black Diaspora: An International Journal 7 (1): 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/17528631.2013.861235.

- Sipi, Remei. 2010. Genealogies femenines: les dones immigrades a Catalunya. 20 anys d’associacionisme en femení. Barcelona: Yemanjà.

- Stolcke, Verena. 1992. Racismo y sexualidad en la Cuba colonial. Madrid: Alianza Editorial.

- Stoler, Ann Laura. 1991. “Carnal knowledge and Imperial Power: Gender, race, and Morality in Colonial Asia.” In Gender at the Crossroads of Knowledge. Feminist Anthropology in the Postmodern Area, edited by Di Leonardo, 51–101. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Stucki, Andreas. 2019. Violence and Gender in Africa’s Iberian Colonies. Feminizing the Portuguese and Spanish Empire, 1950s–1970s. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Telo, A., and Hipólito de la Torre. 2000. Portugal e Espanha nos sistemas internacionais contemporáneos. Lisboa: Cosmos.

- Torre Gómez, Hipólito de la. 2000. “Unidad y dualismo peninsular: el papel del factor externo.” In Portugal y España contemporáneos, edited by Torre, 11–35. Madrid: Marcial Pons.

- Vala, Jorge, Diniz Lopes, and Marcus Lima. 2008. “Black Immigrants in Portugal: Luso-Tropicalism and Prejudice.” Journal of Social Issues 64 (2): 287–302. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2008.00562.x.

- Vi-Makome, Inongo. 2000. La emigración negroafricana: tragedia y esperanza. Culturas alternativas. Barcelona: Ed. Carena.

- Yun-Casalilla, Bartolomé. 2019. Iberian World Empires and the Globalization of Europe. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.