Abstract

Background: The worlds of a physician and a jazz musician seem entirely different. Various studies, however, relating the concepts behind jazz music to medical practice and education, have been published. The aim of this essayistic review is to summarize previously described concepts behind jazz music and its required artistic skills that could be translated to medicine, encouraging doctors, medical students and medical educators to see their professional environment from a different perspective.

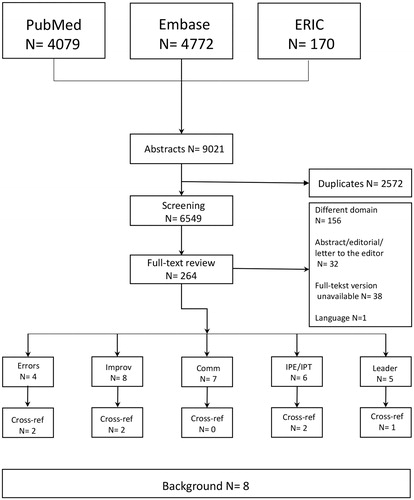

Methods: A systematic search was conducted using PubMed, Embase, and ERIC databases, combining keywords with regard to jazz, medicine and medical education. Background information concerning jazz music and several jazz musicians was retrieved through an additional nonsystematic search using Google Scholar.

Results: Lessons with regard to improvisational skills, both in communication with patients and in a technical context, communication skills, leadership, interprofessional teamwork and coping with errors are presented.

Conclusions: Doctors and medical students could learn various lessons from jazz music performance and jazz musicians. The potential and the possibilities of implementing jazz into the medical curriculum, in order to contribute to the development of professional skills and attitudes of medical students, could be explored further.

Opening the club

“He has to show me that he knows how to listen” – Duke Ellington on the selection of a new band member (Hentoff Citation2009).

What do the sterile white walls, the beeps of monitoring devices and the hastily passing whitecoats of the hospital have in common with a jazz club at night, filled with smoke and the smell of booze, with the murmuring audience in awe of the seemingly uncontrolled chaos on stage? At first glance, the worlds of the doctor and the jazz musician could not be further removed from one another.

Jazz is a musical form that originates from New Orleans in the late nineteenth century (Gioia Citation2011). A typical jazz ensemble consists of a rhythm section (usually drums, double bass, and piano) and a horn section (usually tenor and alto saxophone, and trumpet). Jazz consists of a layer of repetitive rhythmic and harmonic cycles, called “choruses”. The chorus is provided by the rhythm section and has a fixed length (rhythm) and chord progression (harmony). It constitutes a foundation on top of which the soloist(s) (the horn section) can improvise. The chord progression that is given to the soloist by the rhythm section serves as the starting point for improvisation, as jazz musicians have learned which tones can be used in improvisation together with a certain given chord. The resulting improvised solo can take on many forms: from a simple variation on a well-known melody to discarding the melody entirely to rely solely on its underlying chord progression. The solo can be an individual melodic statement, but it can also take on the form of call-and-response between soloists, or between the soloist and the rhythm section (Giddins and DeVeaux Citation2009).

The jazz framework of improvisation based on underlying rhythmic and harmonic structure in an ensemble context has been related to medicine previously. The aim of this essayistic review is to inspire doctors, medical students, and medical teachers to see their professional environment from a different perspective. As this paper will illustrate, the jazz framework applies to medicine and medical education both as a metaphor for organization and culture and a practical tool in clinical education. The reader will experience an imaginary evening at a jazz club, with each “stage” describing a specific theme within the relationship between jazz and medical education.

Set-up

A preliminary literature search was conducted on the 23 February 2017. PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, and ERIC databases were searched using a combination of the keywords “jazz”, “medicine”, “medical education”, “doctor”, and their respective synonyms (Supplementary Appendix 1a). This search yielded four studies specifically focused on jazz from which five lessons/themes within the relationship between jazz and medical education were identified: (1) improvisation, (2) communication, (3) attitude toward errors, (4) leadership, and (5) interprofessional teamwork. An additional broadened literature search was conducted on the 8 January 2018 to elaborate on these themes, using keywords for each theme (Supplementary Appendix 1b). General exclusion criteria were: editorials, commentary, letters to the editor, and abstracts, or articles written in any language other than Dutch, German, English, French, or Italian. shows the specific inclusion and exclusion criteria for each theme. Google Scholar was used to identify relevant background information from (academic) jazz literature. As shown in , the combined literature search yielded 9021 abstracts. Of these, 264 studies were reviewed in full text, of which 37 were finally included.

Figure 1. Systematic search flow chart. Improv: improvisation; Comm: communication; IPE: interprofessional education; IPT: interprofessional teamwork; Leader: leadership.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria per theme.

Practice room

Room for errors

Medical error leads to approximately 250,000 preventable deaths in the USA alone (Makary and Daniel Citation2016). Patient safety requires, among other aspects, recognition of individual errors as system errors, a non-punitive environment for individual errors, and transparency in error disclosure toward patients (Leape Citation2009). Medical education does, however, not sufficiently prepare students to address medical error, which requires deliberate practice (Stroud et al. Citation2013; Harrison Citation2017). How does the jazz musician look at errors? In jazz, there are no “wrong” notes (Lan Doky Citation2016): whenever a jazz musician plays a wrong note, the other members of the band can play a set of notes to accompany the wrong note, integrating it in a new melodic phrase. The “wrong” note is not “wrong”, instead, it provides an opportunity. Pianist Herbie Hancock’s experience with trumpeter Miles Davis as his band leader is illustrative of this perception of error (Bradner et al. Citation2016). Hancock describes a moment during improvisation with the band where he “hit a terrible note”, blaming himself for interrupting an otherwise superb performance. Davis, instead of judging the mistake, picks up on the note, taking the music in an entirely different direction. Medical students could be taught this “Miles Davis method” (Bradner et al. Citation2016): consider errors as an opportunity for greater learning, as a way to probe the student’s understanding of why he or she made the error. How can we adopt this “jazz attitude” toward errors? Han et al. (Citation2017) have identified two cognitive biases that prevent transparent error disclosure. Fundamental attribution error (FAE) is the tendency to overestimate the role of the individual over that of the circumstances. Forecast error (FE) is the tendency to overestimate the duration or impact of the negative consequences of failure. To overcome FAE, one must suppress the reflex to blame the individual and instead analyze the situational forces. To overcome FE, one must be able to “decatastrophise” the failure through recollection of previous failures that seemed overwhelming at first, but that one could eventually cope with. To teach coping with these cognitive biases, the authors propose a longitudinal curricular framework incorporating standardized patient and virtual reality scenarios (Han et al. Citation2017).

Main set

Playing the solo: the art of improvisation

Improvisation is essential to jazz music (Haidet Citation2007) in the way jazz musicians relate and communicate with each other. In medicine, improvisation applies to various aspects of clinical practice. Shaughnessy et al. (Citation1998) emphasize improvisation in evidence-based decision-making: “The best medical practice (…) is like good jazz, combining technical mastery with the artistry of focused personal improvisation. Clinical jazz combines the structure supplied by patient-oriented evidence with the physician’s clinical experience to manage situations of uncertainty, instability, uniqueness and conflicting values”.

Improvisation is also relevant to technical surgical skills. Martellucci (Citation2015) uses the definition of improvisation as given by saxophone player Lee Konitz: the far end of a continuum, ranging from “interpretation (taking minor liberties with a melody or choosing novel accents or dynamics while performing it basically as written) through embellishment (…) and variation (…) ending in improvisation, which means transforming the melody into patterns, bearing little or no resemblance to the original model or using models altogether different from the melody as the basis for inventing new phrases”. The surgeon has to reflect in action, take often irreversible decisions with possible grave consequences and manage errors in the performance of standardized surgical procedures. Martellucci (Citation2015) considers improvisation the only method to “manage the unexpected”. However, in surgery, like in jazz music performance, improvisation consists of a mixture of predefined elements (standardized protocols, procedures and theory in surgery; a simple melody or precomposed phrases in jazz music) and spontaneity.

Finally, a clinician should be skilled in improvisation in the encounter with the patient (Haidet Citation2007). To underline this concept of improvisation in communication, Haidet quotes Stephen Nachmanovitch, a scholar on creativity, who stated: “In real medicine you view the person as unique – in a sense you drop your training. (…) You certainly use your training (…), but you don’t allow your training to blind you to the actual person who is sitting in front of you. In this way, you pass beyond competence to presence. To do anything artistically, you have to acquire technique, but you create through your technique and not with it.”

As all authors illustrate, improvisation in medicine must have a foundation of clinical and communicative skill, knowledge and evidence, comparable to the foundation provided by the rhythm section in a jazz ensemble. But how can students and doctors become skilled improvisers? Hoffmann-Longtin et al. (Citation2017) have outlined the implementation of applied improvisation in medicine, based on three principles: (1) accepting all offers from others to build on their ideas; (2) recognizing everything as a gift; (3) treating collaborators as an equal partner.

Several studies (Hoffman et al. Citation2008; Watson Citation2011; Salas et al. Citation2013; Shochet et al. Citation2013; Casapulla et al. Citation2016; Sawyer et al. Citation2017) have examined the effects of improvisational skills training. These studies were designed around a single or a series of improvisational communication workshops, where participants engaged with each other in improvisational exercises (call-and-response exercises, or elaboration on standard conversation scenarios) followed by questionnaires or reflective assignments to measure the effects. In all studies, a majority of participants considered an improvisational skill course to enhance doctor–patient communication a positive experience, especially with regard to problem-solving, reflection, and relationship-building.

Trading solos: the art of conversation

Jazz can be perceived as a language, used by jazz musicians to “converse” with one another, thus telling a story (i.e. creating music) on the spot (Lan Doky Citation2016). This “musical encounter” in jazz bears similarities to the doctor–patient encounter.

Haidet (Citation2007) defines three levels of jazz performance-inspired communication with the patient: creating space, developing voice, and cultivating conversation.

Like jazz musicians, doctors, and patients collaborate within a “communicative space”. As a doctor, it is important to let the patient have his say, rather than to take up the entire space by asking a multitude of questions and giving extensive explanations. Instead, the doctor should adopt the playing style of Miles Davis. Davis might not have been the most technically gifted player, but through the way he developed his solos, he was able to let the listener experience the broader context of the music by allowing the listener to hear what the rest of band are playing. As a soloist, the notes that Davis plays are as important as the ones he does not play. Silence is indeed an essential part of this communicative space in both jazz and medicine: profound listening enables the doctor to truly connect with the patient (Bradner et al. Citation2016).

One could listen to the same jazz standard sung by Billie Holiday and Sarah Vaughan, and hear two completely different songs: both singers had their own “voice”, their distinct personal style (Gioia Citation2011). The most influential jazz musicians are able to channel the theory and technique of their predecessors through their own personalities and feelings (Haidet Citation2007) – perhaps the foremost strength of Holiday (Gioia Citation2011). Likewise, a doctor must develop his basic communication skills and knowledge of common communicative scenarios and incorporate these into the development of his personal style, in order to tailor the conversation to the particular context and the specific patient. Like a (jazz) improviser, the doctor must approach the patient with openness and curiosity to enable this adaptability (Younie Citation2017).

To cultivate conversation (Haidet Citation2007), the doctor and the patient have to accommodate to each other’s statements and styles of communication, like a jazz ensemble having to develop an understanding of the space that each individual member is allowed in playing and improvising together, as well as knowing what to play within this given space. The doctor and the patient must likewise strive to achieve a common understanding, allowing the conversation to go back and forth, thus facilitating shared decision-making. The doctor should listen with the aim of understanding the patient rather than collecting the facts, while being aware of the subtle non-verbal clues that the patient provides. He or she should explore the patient’s story behind his chief complaint (Bradner et al. Citation2016), this being key to the medical encounter. Herbie Hancock was once told by Miles Davis “not to play the butter notes”: instead of merely discussing the obvious pathophysiological aspects, the doctor should also try to find “the alternate chords” – the reflective and metacognitive aspects in the encounter with the patient.

How can we teach the understanding of the use of space and silence, listening, personal voice, curiosity, and conversation in the doctor–patient encounter? Haidet et al. (Citation2017) have developed a jazz-based curriculum in communication skills, consisting of in-class activities (active listening exercises, discussion and translation to medical practice), and clinical practice. The effects of the course were assessed through pre- and post-course standardized patient interviews. Compared to a control group who received no further instruction, course participants showed significant improvement in adaptability and quality of listening. However, only short-term outcomes were measured.

Finally, improvement of communication skills also concerns the method of practice. Musicians do not practice during formal practice sessions (Davidoff Citation2011; Haidet and Picchioni Citation2016). Instead, formal practice is used to identify weaknesses and specific points for individual practice outside of formal tutorial. Jazz musicians refer to periods of intense, focused individual practice as “woodshedding” (after a story about alto saxophone legend Charlie “Bird” Parker, who allegedly relentlessly practiced for months in his backyard woodshed after being forced off stage). The “woodshedding” doctor would use communication skills tutorials to identify certain elements of the patient encounter that require his or her attention and practice these elements during the actual encounter in the clinical environment (Haidet and Picchioni Citation2016). This might sound paradoxical: during the encounter, the doctor is required to perform, to collect information about the patient’s symptoms and to provide care (Schattner Citation2014). Thinking like a jazz musician, however, one could argue that, although learning is not the primary goal of the patient encounter, the doctor should embrace the opportunity to learn from every encounter.

The classical pianist in the jazz ensemble: the importance of interprofessional teamwork

On their 1961 landmark recording “Waltz for Debby” (Riverside RLP-399), the Bill Evans Trio, consisting of pianist Bill Evans, double-bassist Scott LaFaro and drummer Paul Motian, transformed the jazz trio in the way that the ensemble was well-balanced, as all members could simultaneously play solo and support each other (Pettinger Citation1998; Haidet Citation2007; Gioia Citation2011). Most notably, Evans and LaFaro developed a level of understanding and listening to each other that made it hard to discern soloist and supporting player (Haidet Citation2007). Evans, however, was originally classically trained and he used this background to develop an innovative, distinct piano style, drawing inspiration from eighteenth-, nineteenth-, and impressionist early twentieth-century classical composers (Israels Citation1985; Pettinger Citation1998). In medicine, the need for interprofessional education (IPE) to improve collaborative practice has been clearly established by the WHO (Gilbert et al. Citation2010). The interprofessional team can be viewed as the medical equivalent of the jazz ensemble. Despite different educational backgrounds (comparable to playing different instruments), physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and other healthcare professionals need a common understanding to work together. Yet, physicians and nurses often value collaboration differently (House and Havens Citation2017). Differences in communication styles, as well as interprofessional hierarchies, have a negative influence on collaboration (Foronda et al. Citation2016). From a jazz perspective, balancing the contributions of each individual member is key: jazz ensembles that work well together, seem to achieve an effortless sense of rhythmic synchronization (or “swing”). In bands that are rhythmically out of sync, each individual is tempted to overplay (Gioia Citation2016). To have the interprofessional team achieve a “sense of swing”, a common understanding, entails development of shared mental models (Floren et al. Citation2018), through e.g. team-interaction training, cross-training, team huddles or group or individual reflections.

In addition, as seen in the Bill Evans Trio, the role of each individual band member shifts between supporting and soloing. In the medical interprofessional team, roles are also fluid and overlapping (Lingard et al. Citation2012). Simplified implementation of IPE aimed at “the recognition of roles in the team” would not take this fluidity into account (Lingard Citation2016). Indeed, the interprofessional medical team can be viewed as a complex adaptive system (Pype et al. Citation2017), prompting the call for the integration of complexity theory in medical education (Bleakley Citation2010). The jazz ensemble could thus serve as a metaphor in IPE to clarify this complex nature of the interprofessional team.

Leading from the bandstand: the importance of leadership

Duke Ellington led his eponymous jazz orchestra for decades. As a leader, he was known to arrange his compositions in the way that best suited the individual strengths of his band members (Gioia Citation2011).

The interdisciplinary and interprofessional nature of contemporary medicine requires leadership qualities of physicians. In recent years, the need for physician leadership has been given increasing attention, as clinicians often feel insufficiently trained for a leadership role (Stoller Citation2014). Although “leadership” is difficult to define (Patel et al. Citation2010), many studies have focused on curricula for physician leadership training (Rosenman et al. Citation2014; Frich et al. Citation2015) as well as identifying specific competencies for physician leaders (Patel et al. Citation2010; Green et al. Citation2017). Often, directive or task-based leadership (defining goals, team strategy) is distinguished from team-based or developmental leadership (providing support, coaching, communication skills, emotional intelligence, and behavior) (Patel et al. Citation2010; Rosenman et al. Citation2014; Stoller Citation2014; Weller et al. Citation2014; Green et al. Citation2017). This duality (Rosenman et al. Citation2014) of physician leadership aligns with jazz band leadership. Like a jazz band leader, the physician leader should serve the team (Martellucci Citation2015). As a leader, he or she must strive to be a partner within the team to promote a climate of psychological safety, wherein members are encouraged to act, based on the mutual trust of the team and its agreement to a set of non-negotiable rules as a foundation. In a similar fashion, instead of merely conducting, a jazz band leader plays with the band, allowing each member the space to play within the rhythmic and harmonic framework as set by the leader (Gioia Citation2016). Jazz band leadership is an acknowledged metaphor in the field of business leadership (Adams Citation2012). Equally, jazz band leadership is a suitable metaphor for physician leadership in the context of leading a small team.

After-hours jam session

This essayistic review summarizes the available medical literature on the translation of the concepts behind jazz music performance and artistry to medicine and medical education, illustrating how jazz can be used both as a metaphor in organizational and behavioral concepts as well as a practical device in medical education.

The use of the arts in medical education is not a new concept. Many studies have conceptualized or examined the effects of the use of arts in the medical curriculum (Haidet et al. Citation2016): observation of paintings to enhance clinical observational skills (Shapiro et al. Citation2006), reading poetry and prose combined with reflective writing (Wolters and Wijnen-Meijer Citation2012); drama and theater training to enhance empathy and communication skills (Jeffrey et al. Citation2012); and music in general (Davidoff Citation2011; McLellan et al. Citation2013). Among these, jazz provides a unique multifaceted metaphor, with both its ensemble structure, as well as its musical structure being applicable to medicine and medical education, as shown in this paper.

This review has mainly been limited by the small quantity of studies directly relating jazz to medicine. In particular, studies examining the effects of integrating jazz in the medical curriculum are scarce. The conceptual framework has mainly been provided by one author (Haidet), also responsible for the only jazz-based communication skills curriculum (Haidet et al. Citation2017). Although its results are promising, replication of a similar program in other medical curricula and schools could strengthen the case for the use of jazz in the medical curriculum. In addition, a jazz-based curriculum on leadership and interprofessional teamwork would provide an opportunity for integrative teaching of leadership and collaboration, improvisational and communication skills within the team context.

Wrap-up

Jazz relates to medicine and medical education both as a metaphor for IPE and teamwork, organization and culture, as well as a tool to enhance improvisation and communication skills. Studies assessing the effects of the implementation of jazz in the medical curriculum are scarce. Its potential and possibilities could be explored further.

Glossary

Jazz: Musical genre consisting of improvisation on a rhythmic and harmonic foundation (Source: Giddins G, DeVeaux S. 2009. Jazz. New York: W.W. Norton & Company).

cmte-2017-1079-File004.docx

Download MS Word (14.4 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Any mention of performing jazz artists and/or jazz recordings is for educational purposes only, without any intent of copyright infringement. “Waltz for Debby” by Bill Evans Trio (Riverside RLP-399) is courtesy of Concord Music Group, Beverly Hills, CA, USA.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Allard E. van Ark

Allard E. van Ark, MD, recently graduated as a medical doctor. He is passionate about both jazz and medicine and came up with the idea for this article while following an elective in Medical Education at the University Medical Center Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Marjo Wijnen-Meijer

Marjo Wijnen-Meijer, PhD, is Coordinator Quality Control and Associate Professor at the Center for Research and Development of Education, University Medical Center Utrecht, The Netherlands.

References

- Adams S. 2012. Leadership lessons from the geniuses of jazz. Forbes [Internet]. Aug 10. [accessed 2018 Feb 3]. https://www.forbes.com/sites/susanadams/2012/08/10/leadership-lessons-from-the-geniuses-of-jazz/#2f770b48c8b7

- Bleakley A. 2010. Blunting Occam’s razor: aligning medical education with studies of complexity. J Eval Clin Pract. 16:849–855.

- Bradner M, Harper DV, Ryan MH, Vanderbilt AA. 2016. ‘Don’t play the butter notes’: jazz in medical education. Med Educ Online. 21:30582.

- Casapulla S, Longenecker R, Beverly EA. 2016. The value of clinical jazz: teaching critical reflection on, in, and toward action. Fam Med. 48:377–380.

- Davidoff F. 2011. Music lessons: what musicians can teach doctors (and other health professionals). Ann Intern Med. 154:426–429.

- Floren LC, Donesky D, Whitaker E, Irby DM, Ten Cate O, O’Brien BC. 2018. Are we on the same page? Shared mental models to support clinical teamwork among health professions learners: a scoping review. Acad Med. 93:498–509.

- Foronda C, MacWilliams B, McArthur E. 2016. Interprofessional communication in healthcare: an integrative review. Nurs Educ Pract. 19:36–40.

- Frich JC, Brewster AL, Cherlin EJ, Bradley EH. 2015. Leadership development programs for physicians: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 30:656–674.

- Giddins G, DeVeaux S. 2009. Jazz. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

- Gilbert JH, Yan J, Hoffman SJ. 2010. A WHO report: framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. J Allied Health. 39:196–197.

- Gioia T. 2011. The history of jazz. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gioia T. 2016. How to listen to jazz. New York: Basic Books.

- Green ML, Winkler M, Mink R, Brannen ML, Bone M, Maa T, Arteaga GM, McCabe ME, Marcdante K, Schneider J, et al. 2017. Defining leadership competencies for pediatric critical care fellows: results of a national needs assessment. Med Teach. 39:486–493.

- Haidet P. 2007. Jazz and the ‘art’ of medicine: improvisation in the medical encounter. Ann Fam Med. 5:164–169.

- Haidet P, Jarecke J, Adams NE, Stuckey HL, Green MJ, Shapiro D, Teal CR, Wolpaw DR. 2016. A guiding framework to maximise the power of the arts in medical education: a systematic review and metasynthesis. Med Educ. 50:320–331.

- Haidet P, Jarecke J, Yang C, Teal CR, Street RL, Stuckey H. 2017. Using jazz as a metaphor to teach improvisational communication skills. Healthcare. 5:41.

- Haidet P, Picchioni M. 2016. The clinic is my woodshed: a new paradigm for learning and refining communication skills. Med Educ. 50:1208–1210.

- Han J, LaMarra D, Vapiwala N. 2017. Applying lessons from social psychology to transform the culture of error disclosure. Med Educ. 51:996–1001.

- Harrison P. 2017. Encountering the aftermath of medical error. Clin Teach. https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.12741

- Hentoff N. 2009. How jazz helps doctors listen. Jazz Times [Internet]. Apr 1. [accessed 2016 Nov 12]. http://www.jazztimes.com/articles/24523-how-jazz-helps-doctors-listen

- Hoffman A, Utley B, Ciccarone D. 2008. Improving medical student communication skills through improvisational theatre. Med Educ. 42:537–538.

- Hoffmann-Longtin K, Rossing JP, Weinstein E. 2017. Twelve tips for using applied improvisation in medical education. Med Teach. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2017.1387239

- House S, Havens D. 2017. Nurses’ and physicians’ perceptions of nurse-physician collaboration: a systematic review. J Nurs Adm. 47:165–171.

- Israels C. 1985. Bill Evans (1929–1980): a musical memoir. Musical Quarterly. 71:109–115.

- Jeffrey EJ, Goddard J, Jeffrey D. 2012. Performance and palliative care: a drama module for medical students. Med Human. 38:110–114.

- Lan Doky N. 2016. How Jazz Wisdom Will Change Your Life | Niels Lan Doky | TEDxCopenhagen. Copenhagen: TedX Copenhagen. Apr 7. [accessed 2018 Jan 30]. http://tedxcopenhagen.dk/talks/how-jazz-wisdom-will-change-your-life

- Leape LL. 2009. Errors in medicine. Clin Chim Acta. 404:2–5.

- Lingard L. 2016. Paradoxical truths and persistent myths: reframing the team competence conversation. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 36:S19–S21.

- Lingard L, McDougall A, Levstik M, Chandok N, Spafford MM, Schryer C. 2012. Representing complexity well: a story about teamwork, with implications for how we teach collaboration. Med Educ. 46:869–877.

- Makary MA, Daniel M. 2016. Medical error-the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ. 353:i2139.

- Martellucci J. 2015. Surgery and jazz: the art of improvisation in the evidence-based medicine era. Ann Surg. 261:440–442.

- McLellan L, McLachlan E, Perkins L, Dornan T. 2013. Music and health. Phenomenological investigation of a medical humanity. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 18:167–179.

- Patel VM, Warren O, Humphris P, Ahmed K, Ashrafian H, Rao C, Athanasiou T, Darzi A. 2010. What does leadership in surgery entail? ANZ J Surg. 80:876–883.

- Pettinger P. 1998. Bill Evans: how my heart sings. New Haven (CT): Yale University Press.

- Pype P, Krystallidou D, Deveugele M, Mertens F, Rubinelli S, Devisch I. 2017. Healthcare teams as complex adaptive systems: focus on interpersonal interaction. Patient Educ Couns. 100:2028–2034.

- Rosenman ED, Shandro JR, Ilgen JS, Harper AL, Fernandez R. 2014. Leadership training in health care action teams: a systematic review. Acad Med. 89:1295–1306.

- Salas R, Steele K, Lin A, Loe C, Gauna L, Jafar-Nejad P. 2013. Playback theatre as a tool to enhance communication in medical education. Med Educ Online.18:22622.

- Sawyer T, Fu B, Gray M, Umoren R. 2017. Medical improvisation training to enhance the antenatal counseling skills of neonatologists and neonatal fellows: a pilot study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 30:1865–1869.

- Schattner A. 2014. The clinical encounter revisited. Am J Med. 127:268–274.

- Shapiro J, Rucker L, Beck J. 2006. Training the clinical eye and mind: using the arts to develop medical students’ observational and pattern recognition skills. Med Educ. 40:263–268.

- Shaughnessy AF, Slawson DC, Becker L. 1998. Clinical jazz: harmonizing clinical experience and evidence-based medicine. J Fam Pract. 47:425–428.

- Shochet R, King J, Levine R, Clever S, Wright S. 2013. ‘Thinking on my feet’: an improvisation course to enhance students’ confidence and responsiveness in the medical interview. Educ Prim Care. 24:119–124.

- Stoller JK. 2014. Help wanted: developing clinician leaders. Perspect Med Educ. 3:233–237.

- Stroud L, Wong BM, Hollenberg E, Levinson W. 2013. Teaching medical error disclosure to physicians-in-training: a scoping review. Acad Med. 88:884–892.

- Watson K. 2011. Perspective: Serious play: teaching medical skills with improvisational theater techniques. Acad Med. 86:1260–1265.

- Weller J, Boyd M, Cumin D. 2014. Teams, tribes and patient safety: overcoming barriers to effective teamwork in healthcare. Postgrad Med J. 90:149–154.

- Wolters FJ, Wijnen-Meijer M. 2012. The role of poetry and prose in medical education: the pen as mighty as the scalpel? Perspect Med Educ. 1:43–50.

- Younie L. 2017. Beginner’s mind. London J Prim Care. 9:83–85.