Abstract

Tactical decision games (TDGs) have been used in healthcare and other safety-critical industries to develop non-technical skills training (NTS). TDGs have been shown to be a realistic, feasible, and useful way of teaching NTS such as decision making, task prioritisation, situational awareness, and team working. Our 12-tips for using TDG to teach NTS are based on our experience of integrating them into an undergraduate medical and nursing programme. We cover how to design successful TDGs, how to facilitate and debrief them and how to integrate TDGs into curricula. We have found TDGs to be a cost-effective, low fidelity, and useful method of delivering NTS teaching, ideally as an adjunct to immersive simulation. Learners find them a useful way to be introduced to NTS in a safe and relaxed environment, with particular emphasis on critical decision making and prioritisation.

Introduction

Non-technical skills (NTS) are ‘the cognitive, social, and personal resource skills that complement technical skills and contribute to safe and effective task performance’ (Flin et al. Citation2008). NTS are critically important; effective NTS can reduce the likelihood of error, whereas deficiencies in NTS are known to contribute to most medical errors and adverse events (Glavin and Maran Citation2003). Recognition of this importance has prompted significant efforts over the last two decades to develop NTS training in healthcare. Much of this work has drawn upon learning from established ‘Crew Resource Management’ (CRM) programmes in aviation and other safety-critical industries (Flin and Maran Citation2015). In particular, there have been widespread proliferation of simulation-based education (SBE) programmes (Weaver et al. Citation2014). Encouragingly, NTS training appears to improve both participants’ knowledge of NTS and their behaviour during simulated clinical scenarios (O’Dea et al. Citation2014). There is also some evidence of improved clinical outcomes and organisational change (Neily et al. Citation2010; Hagemann et al. Citation2017).

Tactical Decision Games (TDGs) are facilitated, low-fidelity simulations utilising brief written scenarios designed to exercise decision-making and other NTS (Schmitt Citation2019). Participants are presented with a developing problem and are given limited time to decide on a course of action as a group (Drummond et al. Citation2016). They range in complexity and have been specifically developed to focus on key NTS including situational awareness, communication, teamwork, leadership, and stress management (Crichton and Flin Citation2001; Flin et al. Citation2008). They are flexible, adaptable, and can be generic or domain-specific, with sessions often employing a combination of both (Crichton et al. Citation2000).

TDGs offers a complementary approach to immersive clinical simulation which has been regarded as the ‘gold standard’ for NTS training in healthcare but is heavily dependent on expert faculty and specialist resources (Maloney and Haines Citation2016). Indeed, given the small group sizes that characterise most immersive simulation programmes, it is an inefficient and hugely expensive approach for training large groups of learners. Moreover, the vast majority of activities run face-to-face, and many programmes have been considered both too high-risk and resource-heavy to continue during the current response to the COVID-19 pandemic. TDGs offer an alternative that still affords participants with experiential learning but costs significantly less to develop and run than other simulation modalities, requires no specialised equipment and, critically, can be delivered in a classroom or online by one facilitator. Also, recent literature has challenged our assumptions that high fidelity simulators lead to more effective learning, for example, Matsumoto et al. (Citation2002) showed that there was no difference in performance between learners taught ureteroscopy on high or low fidelity models, but with significant differences in cost of $20 versus $3700.

TDGs were originally developed by the US Marine Corps and have been widely used in other safety-critical domains including the prison and fire services, and nuclear and oil industries. They have been shown to make participants feel better prepared to make time-pressured decisions in critical, complex, and stressful situations (Crichton et al. Citation2000; Crichton and Flin Citation2001; Schmitt Citation2019). For example, 3 weeks after prison officers participated in a domain-specific TDG, a prisoner deliberately started a major fire that engulfed a residential hall. The responding supervisor reported that the TDG had helped his mental state of preparedness and that decisions came easily (Crichton et al. Citation2000).

Despite their benefits, and the clear parallels between managing unexpected and complex incidents in healthcare and other safety-critical industries, TDGs remain under-utilised in clinical education. Indeed, a handful of reports describing their use in healthcare have only emerged in recent years. These have shown TDGs to be a useful, feasible, and enjoyable approach to teaching NTS with some self-reported improvements in these skills (Drummond et al. Citation2016; Woodier Citation2016; Suarez and Suarez Citation2020). In our University, we have successfully integrated both generic and clinical TDGs into our medical and nursing inter-professional simulation programme to help address the known difficulties newly-qualified practitioners have demonstrating effective NTS (Tallentire et al. Citation2011; Monrouxe et al. Citation2017).

This article describes twelve tips for using TDGs to teach NTS including designing and developing TDGs, running the TDGs, and integrating them into programmes. It is drawn from both our own extensive experience of utilising TDGs and the broader literature on TDGs and NTS.

Designing successful tactical decision games

Tip 1

Use your TDGs to introduce or target specific non-technical skills

The key to an effective TDG (and indeed any NTS learning) is alignment between the task and the intended learning objectives. Hamstra et al. (Citation2014) suggest that ‘fidelity’ in simulation should be replaced with ‘functional task alignment’ and that clear learning outcomes, authentic scenarios, and engaged learners lead to knowledge transfer more so than the level of fidelity of the simulation environment. Therefore, the first step in TDG design is to consider the specific NTS you wish to cover so that you can choose or design a TDG appropriately. The NTS to be targeted will need to vary between professional groups and teams. For example, the NTS required of a senior anaesthetist will be different from those of a medical student (Flin et al. Citation2010). Where possible, we suggest using behavioural marker systems (BMS) that have been developed to highlight the NTS critical to different professional groups. For example, BMS for medical students and newly qualified doctors in acute care settings highlight the key importance of escalating care, speaking up, projecting to future states, establishing a team, and balancing options (Mellanby et al. Citation2013; Hamilton et al. Citation2019).

TDGs have previously been shown to be a feasible and acceptable way to introduce students to NTS and this is where we have found them particularly useful in our practice (Drummond et al. Citation2016; Suarez and Suarez Citation2020). Social learning theories describe the importance of the social context in developing shared mental models between the learners and the teachers in simulation; thereby allowing students to develop ‘signifiers’ (a shared language of practice), particularly important when introducing learners to new concepts such as NTS (Schoenherr and Hamstra Citation2017).

A facilitated debrief helps participants to reflect upon behaviours that contributed to the team’s performance during the TDG and introduces them to the underpinning NTS concepts. For example, we use Collier’s generic ‘plane crash’ TDG, in which participants are given limited time to decide which of the two holds of a crashed plane they want to open and which items they want to rescue before the plane explodes (Drummond et al. Citation2016). The discussion in the debrief around whether the teams had verbalised a plan of ‘stay and build a camp’ or ‘go for help’ can be used to discuss hidden assumptions and the concept of shared mental models or ‘distributed’ situational awareness (Drummond et al. Citation2016). The concrete experience provided by the TDG is particularly useful as the terminology and definitions within NTS can be difficult for students to grasp (Drummond et al. Citation2016).

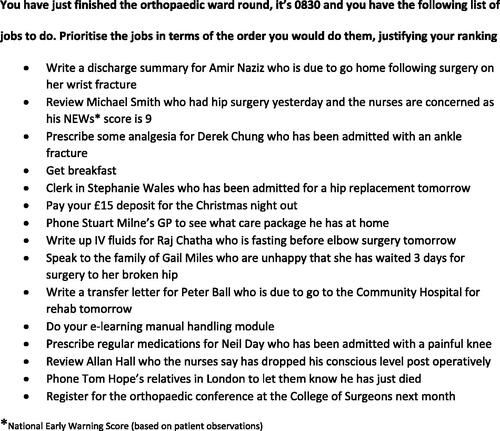

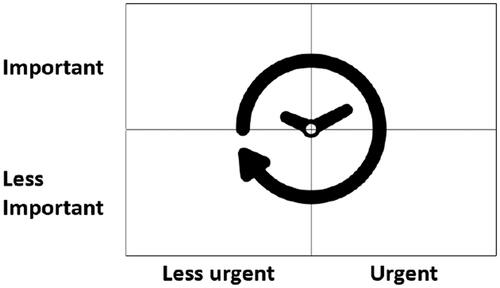

We suggest targeting specific learning needs, particularly those that are difficult for learners to experience for themselves in the clinical area. For example, students and junior practitioners can struggle with escalating care but the nature of the TDG can empower individuals to ‘speak up.’ Indeed, participants in Suarez and Suarez’s TDGs reported feeling more confident and ‘better able to delegate upwards’ (2018). Similarly, UK junior doctors identified ‘task prioritisation’ as the most important NTS for their role but reported little prior experience or teaching on this (Brown et al. Citation2015; Drummond et al. Citation2016). In response, we designed an ‘orthopaedic ward round’ TDG, with a list of tasks for completion, that we use as an introduction to prioritisation (). In the debrief, we discuss a modified version of Eisenhower’s urgent-important prioritisation matrix () that considers time efficiency. This recognises that it can be more efficient overall to complete some less urgent or important tasks sooner; for example, prescribing routine medications or fluids for patients in the same ward after completing an urgent review (Covey Citation2004).

Tip 2

Incorporate broader professional issues and personal skills

In our experience, TDGs provide an excellent forum for discussion of broader professional issues in healthcare. When developing your learning outcomes, think about the personal skills your learners may not otherwise get many opportunities to explore. We designed tasks in our orthopaedic TDG that would allow students to explore issues such as wellbeing; the importance of taking breaks; potential cognitive and emotional biases and how to minimise their effects; as well as other factors that can impact on decision making, such as being hungry, angry, late, tired (HALT) (See Supplement material) (Baverstock and Finlay Citation2019). We also discuss issues around empathy; communication, particularly the importance of saying sorry; as well as ethical issues surrounding end-of-life care.

Tip 3

Create a level playing field by shifting the focus from medical knowledge

Well-designed TDGs should create a ‘level playing field’ where medical knowledge has a limited influence upon how individuals and teams perform. This shifts the focus to NTS, making them ideally suited for use with both hierarchical and horizontal teams. This often encourages quiet or less confident participants to ‘speak up’ because their clinical knowledge is not in question (Drummond et al. Citation2016). In our experience, this has made TDGs an ideal tool for inter-professional learning. We use our orthopaedic TDG to introduce junior medical and nursing students to NTS, and the TDG is deliberately designed to explore the potential for conflicting priorities between the two professions. This has invariably led to interesting discussions, particularly around breaking bad news to a relative and discharge letters which nursing students have consistently prioritised higher than the medical students. In our experience, this appears to afford students with a deeper understanding of, and empathy towards, each other’s different roles, ‘identities’ and priorities.

Generic TDGs, such as the ‘plane crash,’ are one way to establish this level playing field. In Drummond et al’s study of the feasibility of TDGs for teaching NTS to medical students, focus groups revealed that students liked the generic TDGs and felt that they helped keep attention on NTS rather than the medical knowledge that is required for immersive simulation scenarios (Drummond et al. Citation2016). Similarly, in other safety-critical industries, generic TDGs have been shown to facilitate a good introduction to NTS with subsequent domain-specific TDGs allowing skills to be explored in context (Crichton and Flin Citation2001).

Alternatively, domain-specific TDGs can be purposefully designed so that all participants are likely to have the required clinical knowledge to be able to complete the tasks. For example, an Emergency Department’s resuscitation room team should all have the required knowledge to treat a patient with uncomplicated sepsis due to pneumonia, allowing the focus to be on NTS.

Tip 4

Incorporate dilemmas and uncertainty into your TDGs

Effective TDGs are designed to include dilemmas that force participants to make choices as a team and exercise the NTS under consideration. Crucially, the discussion in the debrief about how and why a decision was reached is far more important than the decision itself. For example, in the plane crash TDG, it is perfectly acceptable for the team to access either hold; what is more important is whether that decision was taken as a group of individuals or as a team working towards a shared goal. There should be no accepted right or wrong answers and ambiguity is vital to a TDG’s success (Crichton et al. Citation2000; Drummond et al. Citation2016; Schmitt Citation2019). One of the ways to achieve this ambiguity is to give limited and slightly vague information that can be interpreted a number of different ways (Schmitt Citation2019). For example, when deciding on a ‘stay’ or ‘go’ strategy after the plane crash, a box of matches could be useful to either light a fire for camp or as a distress signal to attract help.

Ambiguous TDGs also offer an opportunity to explore uncertainty and complexity, two aspects of decision-making that are particularly challenging and stressful during the transition from student to practice (Brennan et al. Citation2010; Drummond et al. Citation2016). The uncertain nature of TDGs reflects the clinical environment and requires participants to consider multiple factors in order to make a balanced decision. Drummond et al. found students recognised that the ambiguity of TDGs reflected the ‘real-life clinical situations’ they had encountered on the wards and may actually help them develop a tolerance of uncertainty (Drummond et al. Citation2016).

Tip 5

Create TDGs that are authentic and appropriately challenging

To be effective and credible, TDGs need to be interesting, challenging, and authentic (Crichton et al. Citation2000; Crichton and Flin Citation2001; Schmitt Citation2019). In practice, this means ensuring that the levels of difficulty and stress are matched to the needs of your participants: more novice and junior learners require simpler, low stakes TDGs; more advanced learners or relative experts require TDGs that recreate the complex, dynamic and stressful conditions of the real-world (Lauche and Crichton Citation2009; Guadagnoli et al. Citation2012). We have found that progressing from simple to more complex TDGs across our program helps students put into practice the skills that they recognised and discussed in earlier TDGs.

More complex and dynamic TDGs can be created by introducing new or extra information as the TDG progresses (Crichton and Flin Citation2001). Schmitt refers to these as ‘now what’ TDGs, where an unexpected event occurs that may impact task prioritisation or decision-making (Schmitt Citation2019). For example, in our final-year ‘hospital at night’ TDG, as the TDG progresses students are told about a patient who has become unwell and an abnormal test result that has just been reported. Just be careful not to make your TDGs so complex that they become dependent on extra resources, facilitators, or technology. Remember the main benefit of TDGs is that they can be delivered by one facilitator and should need no more complex equipment than a pen and paper (or virtual equivalent)!

Running the tactical decision games

Tip 6

Focus on the debrief and encourage reflection

Debriefing can be defined as ‘facilitated or guided reflection in the cycle of experiential learning’ (Fanning and Gaba Citation2007). It aims to help learners make sense of the events they have experienced and integrate new insights (Fanning and Gaba Citation2007; Sawyer et al. Citation2016). Debriefing is recognised as the most important part of any SBE activity and is critical for ensuring the learning outcomes are met (Fanning and Gaba Citation2007; Sawyer et al. Citation2016).

Debriefing should be a multidirectional discussion that encourages learners to reflect on the knowledge and beliefs that underpinned their behaviours (Fanning and Gaba Citation2007). In practice, this involves the facilitator asking probing questions about the participants’ behaviours and their underlying frame of mind or decision-making processes (Fanning and Gaba Citation2007; Sawyer et al. Citation2016). Critically, follow-up questions should probe similarities and differences between individual participants. For example, in the plane crash TDG, ‘Did you all choose that hold for the same reason?’ Focusing on how and why these decisions were made can lead to a deeper understanding of how teams work (Drummond et al. Citation2016; Suarez and Suarez Citation2020). Where necessary, the facilitator can then introduce and explain NTS terms to afford participants a shared language for the observations they have explored.

Tip 7

Aim for shared understanding and peer-peer learning

Developing a shared understanding of both the dilemma and each other’s perspectives is a primary objective of TDGs (Crichton et al. Citation2000). This is particularly important for interprofessional education activities where the acquisition of shared knowledge and mutual understanding are felt to deliver key benefits (Homeyer et al. Citation2018). Moreover, participants particularly value this element. Suarez and Suarez’s participants enjoyed observing the heuristics or ‘rules of thumb’ of other participants and the focus on ‘how’ learners thought, not ‘what’ they thought (Suarez and Suarez Citation2020). Undergraduate students in Drummond’s feasibility study appreciated the opportunity that TDGs afforded them to ‘give and receive feedback’ from their peers (Drummond et al. Citation2016). Psychological theories also suggest that learning that occurs in ‘social contexts’ such as TDGs is more likely to lead to an appreciation of the perspectives of fellow learners (Schoenherr and Hamstra Citation2017).

Ideally, the debrief discussion should spread amongst members of the group rather than ‘ping ponging’ between the facilitator and individual participants (Fanning and Gaba Citation2007). In practice, this requires the use of techniques that encourage group discussion such as asking open-ended questions, summarising, and rephrasing comments rather than giving answers. Active listening and the use of silence to draw further discussion are very effective techniques. Occasionally, it is necessary to move around the group looking for input from all participants, particularly where the conversation is being dominated by a few individuals or one professional group (Fanning and Gaba Citation2007).

Tip 8

Factor in time pressures

Enforcing a time limit brings an element of urgency to TDGs that mirrors the time pressure of real-life clinical situations. Time-limited TDGs are particularly useful for exploring dynamic prioritisation and critical situations that necessitate rapidly weighing-up several options. We use a ‘hospital at night’ TDG in the final year to explore these areas through a complex, evolving set of time-sensitive tasks requiring prioritisation. TDGs such as this requires an element of naturalistic decision-making with a focus on ‘sense making’ and planning as opposed to emergency ‘skills and drills’ which are generally driven by protocols and standard operating procedures (Crichton et al. Citation2000; Crichton and Flin Citation2001; Klein Citation2008). Likewise, forcing participants to rapidly assemble a team mirrors the clinical environment where healthcare workers often have to form high-functioning ad-hoc teams, in emergency situations, where skills in followership may be equally if not more important than those in leadership (McKimm and Vogan Citation2020).

Tip 9

Relate generic TDGs back to the clinical context

It is important to situate and contextualise learning by relating the NTS highlighted in generic TDGs back to the participants’ clinical practice. This involves ‘intentionality’ or creating shared mental models where the learner becomes able to see and understand the teachers’ intentions and goals (Schoenherr and Hamstra Citation2017). This can be done using a number of complementary approaches. Firstly, whilst debriefing, the decision-making processes, and team interactions evident during the TDG can be likened to examples from clinical practice. For example, how a decision was made to choose a ‘stay’ or ‘go’ strategy in the plane crash TDG can be likened to how treatment decisions are made rapidly in acutely unwell, complex, patients in the clinical environment. Secondly, participants can be encouraged to consider experiences that they have had in their own practice that relate to the concepts being explored, such as examples of conflicting priorities between nursing and medical staff. Finally, after the debrief, we reinforce and contextualise participants’ learning by showing two videos of real-life patient cases where an error is made because of a failure of NTS. We use these to ‘scaffold’ what students have learned from the TDGs to real-life clinical scenarios. For example, students learn about the importance of communication in their orthopaedic TDG and see the importance of this in one video where a near-fatal drug error occurs because a task was poorly communicated and executed.

Tip 10

Make the TDGs (and the environment) fun

Keeping your TDGs fast-paced, ambiguous, and appropriately challenging yet within a level playing field, helps to make TDGs fun and engage students. We believe learning should be fun, particularly as entertainment and enjoyment may enhance memory (Gifford and Varatharaj Citation2010). In the neuroscience literature, Gruber et al. (Citation2014) showed on MRI scans that stimulating curiosity in learners caused dopamine to be released in the midbrain, leading to a sensation of ‘anticipation’ and enhanced activity in the hippocampus where learning occurs. Importantly, Suarez and Suarez’s group of trainee doctors reported less stressful experiences during TDGs than immersive simulation which generated pressure to do well in front of peers, facilitators, and a camera (Suarez and Suarez Citation2020).

We use ice breakers at the start of our sessions to set an informal tone and move the focus away from clinical knowledge. For example, we show a photo of the Prime Minister’s Questions and ask students to comment on the politician’s team-working (or lack thereof). We have also found that the addition of ‘lollipops’ is popular with the students and appears to promote psychological safety.

Integrating the TDGs into curricula

Tip 11

Use as an adjunct to, not as a replacement for, immersive simulation

TDGs add value to immersive SBE programmes, rather than replacing them, particularly when purposefully integrated into a longitudinal programme (Drummond et al. Citation2016; Suarez and Suarez Citation2020). TDGs are perhaps best utilised as an introduction to relevant NTS before participants undertake high-fidelity simulated clinical scenarios. This can enable the more high-fidelity immersive simulation sessions to focus on the performance of the skills rather than knowledge and elevate the reflection and analysis during debriefing.

We have incorporated TDGs into our interprofessional simulation programme. Students progress from generic TDGs and simple clinical simulations in the early years through to much more challenging domain-specific TDGs and complex clinical simulations in their final year. For example, final-year students undertake a simulated ward round activity consisting of multiple simultaneous patient simulations (Harvey et al. Citation2015). We use the ‘hospital at night’ clinical TDG immediately beforehand to focus on dynamic prioritisation and ‘task efficiency.’ This appears to have improved both students’ performance and confidence during the simulated ward round. Importantly, it has also allowed the debrief to focus on how teams can develop a shared understanding of their priorities rather than the mechanics of prioritising tasks.

Tip 12

Be creative about the way you use the TDGs and the teams you involve

The flexibility and adaptability of TDGs make them suitable for a wide variety of contexts and teams. We have used TDGs effectively with groups from 5 to 10 students through to a workshop with 100 participants playing TDGs around small tables. We have also delivered TDGs remotely using online platforms such as Zoom or MS Teams, with participants in multiple locations. As well as supporting social distancing efforts, this can facilitate learning for teams in remote and rural locations. For example, Crichton et al used TDGs in the oil industry to facilitate NTS training for distributed teams, where a critical scenario could involve team members in several locations, both on and off-shore (Lauche and Crichton Citation2009).

TDGs can be used for training teams who work together frequently, an Emergency Department resuscitation room team, for example, or those that form ad-hoc such as a hospital’s major incident response team. We have also used TDGs with staff from different departments to develop a greater understanding of the challenges of each other’s roles and explore the potential for goal conflicts during their interactions. Our experience suggests that TDGs could enhance both undergraduate and postgraduate curricula, as well as benefitting the professional development of established healthcare practitioners.

Conclusion

TDGs offer a flexible/adaptable, fun, and cost-effective approach to NTS training that can be used in a variety of settings, including to augment immersive high-fidelity simulation programmes. They can be developed to target various NTS and offer the opportunity to rehearse decision-making under uncertain and time-pressured conditions; skills that are more important than ever given the ever-increasing complexity of healthcare.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (16.4 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank NHS Fife for funding the Research Fellow post who explored the feasibility of TDGs in teaching medical students NTS and the CSMEN for a research grant to support this work. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Catherine Collier for allowing us to use her plane crash TDG.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Scott Clarke

Scott Clarke, MBChB, MCEM, MRCEM, DIMC RCSEd, FHEA, is a Fellow in Medical Education and a senior trainee in Emergency medicine in Edinburgh, and has designed and delivered year 4 TDG sessions.

Janet Skinner

Janet Skinner, MBChB, FRCS Ed, FCEM, MSc Med Ed, is Director of Clinical Skills at the University of Edinburgh and an NHS Lothian Emergency Medicine Consultant, and has helped design, implement and deliver TDGs as part of the undergraduate medical and nursing programmes.

Iain Drummond

Iain Drummond, MBChB, MRCP (UK), MD, MRCP (Nephrology), is a Renal Consultant at the Queen Elizabeth University Hospital, Glasgow and carried out the initial feasibility study into TDGs as part of an MD in Medical Education.

Morwenna Wood

Morwenna Wood, MA, MBBS, FRCP, DPhil, AoME, is a Renal Professor and Director of Medical Education in NHS Fife, and along with JS supervised the initial feasibility study.

References

- Baverstock A, Finlay F. 2019. Take a break: HALT - are you hungry, angry, late or tired? Arch Dis Childhood. 104(4):200.

- Brennan N, Corrigan O, Allard J, Archer J, Barnes R, Bleakley A, Collett T, de Bere SR. 2010. The transition from medical student to junior doctor: today’s experiences of tomorrow’s doctors. Med Educ. 44(5):449–458.

- Brown M, Shaw D, Sharples S, Jeune IL, Blakey J. 2015. A survey-based cross-sectional study of doctors’ expectations and experiences of non-technical skills for out of hours work. BMJ Open. 5(2):e006102.

- Covey S. 2004. The 7 habits of highly effective people. New York (NY): Free Press.

- Crichton M, Flin R. 2001. Training for emergency management: tactical decision games. J Hazard Mater. 88(2–3):255–266. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11679197.

- Crichton MT, Flin R, Rattray WAR. 2000. Training decision makers - tactical decision games. J Contingencies Crisis Manage. 8(4):208–217.

- Drummond I, Sheikh G, Skinner J, Wood M. 2016. Exploring the feasibility and acceptability of using tactical decision games to develop final year medical students' non-technical skills. Med Teach. 38(5):510–514.

- Fanning RM, Gaba DM. 2007. The role of debriefing in simulation-based learning. Simul Healthc. 2(2):115–125.

- Flin R, Maran N. 2015. Basic concepts for crew resource management and non-technical skills. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 29(1):27–39.

- Flin R, Patey R, Glavin R, Maran N. 2010. Anaesthetists’ non-technical skills. Br J Anaesth. 105(1):38–44.

- Flin R, O’Connor P, Crichton M. 2008. Safety at the sharp end; a guide to non-technical skills. Ashgate (UK): Taylor and Francis Ltd.

- Gifford H, Varatharaj A. 2010. The ELEPHANT criteria in medical education: can medical education be fun. Med Teach. 32(3):195–197.

- Glavin RJ, Maran NJ. 2003. Integrating human factors into the medical curriculum. Med Educ. 37:59–64. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14641640.

- Guadagnoli M, Morin MP, Dubrowski A. 2012. The application of the challenge point framework in medical education. Med Educ. 46(5):447–453.

- Hagemann V, Herbstreit F, Kehren C, Chittamadathil J, Wolfertz S, Dirkmann D, Kluge A, Peters J. 2017. Does teaching non-technical skills to medical students improve those skills and simulated patient outcome? Int J Med Educ. 8:101–113.

- Hamilton AL, Kerins J, MacCrossan MA, Tallentire VR. 2019. Medical Students’ Non-Technical Skills (Medi-StuNTS): preliminary work developing a behavioural marker system for the non-technical skills of medical students in acute care. BMJ Stel. 5(3):130–139.

- Hamstra SJ, Brydges R, Hatala R, Zendejas B, Cook DA. 2014. Reconsidering fidelity in simulation-based training. Acad Med. 89(3):387–392.

- Harvey R, Mellanby E, Dearden E, Medjoub K, Edgar S. 2015. Developing non-technical ward-round skills. Clin Teach. 12(5):336–340.

- Homeyer S, Hoffmann W, Hingst P, Oppermann RF, Dreier-Wolfgramm A. 2018. Effects of interprofessional education for medical and nursing students: enablers, barriers and expectations for optimizing future interprofessional collaboration - a qualitative study. BMC Nurs. 17(1):1–10.

- Klein G. 2008. Naturalistic decision making. Hum Factors. 50(3):456–460.

- Lauche K, Crichton M. 2009. Tactical decision games-developing scenario-based training for decision-making in distributed teams. British Computer Society Proceedings of NDM9, the 9th International Conference on Naturalistic Decision Making; London, UK.

- Maloney S, Haines T. 2016. Issues of cost-benefit and cost-effectiveness for simulation in health professions education. Adv Simul. 1(1):13.

- Matsumoto ED, Hamstra SJ, Radomski SB, Cusimano MD. 2002. The effect of bench model fidelity on endourological skills: a randomized controlled study. J Urol. 167(3):1243–1247.

- Gruber MJ, Gelman BD, Ranganath C. 2014. States of curiosity modulate hippocampus-dependent learning via the dopaminergic circuit. Neuron. 84(2):486–496.

- McKimm J, Vogan C. 2020. Followership: much more than simply following the leader. Leader. 4(2):41–44.

- Mellanby E, Hume M, Glavin R, Skinner J, Maran N. 2013. FoNTS - Foundation non-technical skills; [accessed 2020 Jun 1]. http://www.docs.hss.ed.ac.uk/iad/Learning_teaching/Academic_teaching/PTAS/Outputs/Mellanby_Jan2012award_PTAS_Final_Report.pdf.

- Monrouxe LV, Grundy L, Mann M, John Z, Panagoulas E, Bullock A, Mattick K. 2017. How prepared are UK medical graduates for practice? A rapid review of the literature 2009-2014. BMJ Open. 7(1):e013656.

- Neily J, Mills PD, Young-Xu Y, Carney BT, West P, Berger DH, Mazzia LM, Paull DE, Bagian JP. 2010. Association between implementation of a Medical Team Training Program and surgical mortality. JAMA. 304(15):1693–1700.

- O’Dea A, O’Connor P, Keogh I. 2014. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of crew resource management training in acute care domains. Postgrad Med J. 90(1070):699–708.

- Sawyer T, Fleegler M, Eppich W. 2016. Essentials of debriefing and feedback. In: Grant V, Cheng A, editors. Comprehensive healthcare simulation: pediatrics. Cham (Switzerland): Springer; p. 31–42.

- Schmitt J. 2019. Designing good TDGs; [accessed 2020 Jun 1]. https://mca-marines.org/gazette/designing-good-tdgs/.

- Schoenherr JR, Hamstra SJ. 2017. Beyond fidelity: deconstructing the seductive simplicity of fidelity in simulator-based education in the health care professions. Simul Healthc. 12(2):117–123.

- Suarez AE, Suarez N. 2020. Tactical decision games: a novel teaching method for non-technical skills. BMJ Stel. 6(1):54–55.

- Tallentire VR, Smith SE, Wylde K, Cameron HS. 2011. Are medical graduates ready to face the challenges of foundation training? Postgrad Med J. 87(1031):590–595.

- Weaver SJ, Dy SM, Rosen MA. 2014. Team-training in healthcare: a narrative synthesis of the literature. BMJ Qual Saf. 23(5):359–372.

- Woodier N. 2016. “Playing games” – using tactical decision games to enhance non-technical skills*. BMJ Simul Technol Enhanced Learn. 2(1):A20.