Abstract

Background

As there is a need to prepare doctors to minimize errors, we wanted to determine how doctors go about reflecting upon their medical errors.

Methods

We conducted a thematic analysis of the published reflection reports of 12 Dutch doctors about the errors they had made. Three questions guided our analysis: What triggers doctors to become aware of their errors? What topics do they reflect upon to explain what happened? What lessons do doctors learn after reflecting on their error?

Results

We found that the triggers which made doctors aware of their errors were mostly death and/or a complication. This suggests that the trigger to recognize that something might be wrong came too late. The 12 doctors cited 20 topics’ themes that explained the error and 16 lessons-learnt themes. The majority of the topics and lessons learnt were related more to the doctors’ inner worlds (personal features) than to the outer world (environment).

Conclusion

To minimize errors, doctors should be trained to become earlier and in time aware of distracting and misleading features that might interfere with their clinical reasoning. This training should focus on reflection in action and on discovering more about doctors’ personal inner world to identify vulnerabilities.

Introduction

Medical errors threaten patient safety because of the associated morbidity and mortality [Kohn et al. Citation2000]. Errors are commonly multi-factorial in origin and involve both system-related and cognitive factors (Kohn et al. Citation2000; Graber Citation2013; Singh et al. Citation2017; Graber et al. Citation2012; Croskerry Citation2003; Clapper and Ching Citation2020). Different strategies can be used to reduce errors such as educational strategies (e.g. curricula covering decision-making theories), workplace strategies (e.g. time-out whilst in the operating room) and cognitive forcing functions (e.g. reflection) (Croskerry et al. Citation2013). Young doctors commonly reflect on patient safety incidents within their professional portfolios (Ahmed et al. Citation2012). Such critical reflection is a cognitive forcing function because it depends on the clinician consciously applying a metacognitive step and cognitively forcing a necessary consideration of alternatives. This shows that reflection is an essential drive in learning from one’s own behaviour, and a key concept in the conscious interpretation of it (Hatton and Smith Citation1995; Korthagen and Wubbels Citation1995; Korthagen and Kessels Citation1999). Experimental studies have suggested that a more reflective reasoning approach may even prevent a mistake through a new perception which then changes one’s way of thinking (Mamede and Schmidt Citation2017; Brush et al. Citation2022). Thus reflection, including a systematic and critical analysis of past behaviours and the underlying assumptions, might be a guide for future behaviours (Dewey Citation1933). It is, therefore, an outstanding instrument to minimize errors (Epstein Citation2017; Mamede and Schmidt Citation2017).

Practice points

Timing and focus of reflection is important when using reflection as a cognitive strategy to minimize errors;

Timing of reflection can be optimised by making a shift from reflection on action to reflection in action;

Doctors should be trained in mindfulness skills to reflect in action;

The focus of doctors’ reflection should be on their inner world to identify vulnerabilities.

Even though reflection is commonly used by doctors (Ahmed et al. Citation2012), little is known about the reflection process. In other words: how do doctors start, move, stop and look back in the reflection circle and what does this reveal about reflection? By looking at this process, we want to get an insight into doctors’ behaviours when making errors and, with this deeper understanding, we might be able to train doctors more precisely in using reflection to minimize errors and to learn from errors. As there is a need to prepare young doctors to improve patient safety (O’Connor et al. Citation2019), we looked into how doctors went about reflecting upon their medical errors, hence the reflection process, as described in 12 published reports (Buikema Citation2011). We formulated three research questions for our study:

What triggers doctors to become aware of their errors?

What topics do doctors reflect upon to explain the error?

What lessons do doctors learn after reflecting on their error, visible in their behavioural changes?

Methods

Data source

The study described in this paper is a thematical analysis of published reflection reports about doctors’ medical errors in the book ‘When Healthcare Hurts. Doctors share their darkest hours’ () (Buikema Citation2011). The publication of this book was commissioned by three Dutch health care organizations, including the Dutch Quality Institute for Healthcare (CBO). The goal was to increase openness about medical errors as an essential step to safer health care. The book was originally published in Dutch in 2009 and then in English in 2011 (Buikema Citation2011). The content consists of transcribed verbatims from interviews between the book’s author and medical doctors. In a personal email conversation with the interviewer, we identified how the interviews were performed. Thirteen doctors were selected through purposeful sampling using 3 criteria: candidates must be respected doctors, publicly well-known and working in patient care in different medical fields. One doctor declined due to personal reasons. The interview focused on the circumstances in which the errors arose, the impact of it on the doctor, how the doctor dealt with it, and how the doctor returned to work again. There were no questions about blame. The 12 interviews were held in person and took between 2 and 3 h each. All the doctors gave their informed consent for a non-anonymous publication of the interview in a book. To give an impression, we will describe the cover and how the book is organised. The cover of the 55 page book has photos of the twelve doctors (). Each interview is described in 3 pages and is classified according to a specific outline. The first part begins with the doctor’s name and photo, his/her specialism and a specific quote referring to the error. Then an introduction is given with the doctor’s description of some core aspects of the error. The second part describes a summary of the doctor’s academic and work history. Subsequently, an extensive reflection is given about the analysis of what happened and the changes the doctor made after making the error. The book concludes with an epilogue in which two experts on patient safety discuss openness as the key to safer health care. We used these interviews as a source for our qualitative study to determine (1) what triggered the doctor’s awareness of having made an error, (2) the topics to explain the error, and (3) the lessons learnt from these errors, visible in behavioural change.

Analysis

In the first round of the analytical procedure, all the reflection reports were analysed and coded independently by AV and HR. We started the analysis by familiarizing ourselves with the data line-by-line, using a constant comparative approach to develop codes and themes. We underlined segments of texts which described aspects of a doctor’s behaviour. In this context, behaviour included thinking, doing and feeling with respect to error-making. In other words, what did the doctor (not) think, do or feel when the error appeared? To code the texts, we identified the triggers, topics and lessons learnt by asking the three research questions (). Then, we translated the coded data into themes by selecting verbs that identified expressions of action, and selected nouns and key terms that identified the action’s domain.

Table 1. Illustration of how the reflection themes were derived from the coded data by posing specific questions.

In the next round, we reviewed all the relevant coded data under each theme, and asked ourselves: does each theme have adequate supporting data? Are the included data coherent in supporting that theme? Are some themes too large or too diverse? Then, we defined and (re)named themes and combined themes that overlapped. An example how three overlapping themes were combined into the new definition, ‘confirmation bias’, is: ‘her trip to India had blinded me….’ + ‘… you looking particular for evidence that will support your presumptions’ + ‘I had succumbed to that well-known pitfall whereby doctors tend to look for explanations and symptoms that confirm their own hypothesis’.

Finally, we used the multi-level professionalism framework (Barnhoorn et al. Citation2019) to characterize the behavioural aspects of the themes in the topics and lessons. The behavioural aspects can be divided into outer world (including the environment) and inner world (including personal features such as competencies, beliefs and values, identity and mission) characteristics (Barnhoorn et al. Citation2019). During the whole analytical process, regular meetings were held until consensus was reached by the entire team.

Reflexivity

We conducted a qualitative study using thematic analysis to determine the triggers which made the doctors aware of having made an error, the topics of the errors and the lessons learnt. In qualitative research, the researchers’ backgrounds can influence the interpretation of the data and consequently the construction of the findings and the conclusions, which means the study requires reflexivity. Neither of this present study’s authors had had any formal relationships with the authors of the reflection reports or with the interviewer or the doctors who were interviewed. All the study’s authors were medical educators with specific experience in reflection such as through developing trainings, coaching students and residents in identity formation, and performing research in the field of reflection. The authors were trained as an educationalist (HR) and general practitioners (AV, PB).

Results

After analysing and discussing 43 pages of the reflection reports, we identified three main trigger themes which made the doctors aware of their errors, 20 themes of topics’ errors which these doctors had reflected upon and 16 themes of lessons learnt following the error-making, visible in their behavioural changes.

Error aware making triggers

The 12 doctors referred to triggers in 16 quotes that were relevant moments when they realized something had gone wrong with the patient. These error reflection triggers spanned three themes: (1) death; (2) complication of an intervention; (3) no explicit trigger mentioned ().

Table 2. Illustrative quotes of triggers which made the 12 doctors aware of their error.

Error topics on which the doctors reflected upon

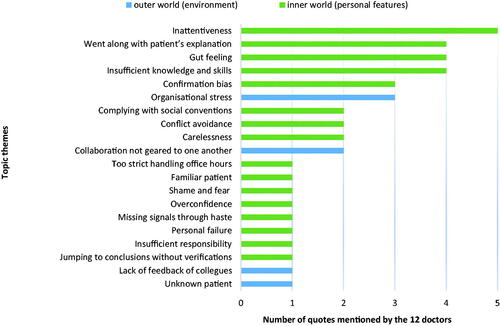

We found 41 quotes by the 12 doctors (range: 2-8) summarized into 20 themes related to the error explanation topics (). Of these topics, 17% concerned the outer world (including environment) and 83% concerned the inner world (including personal features). Overall, the topics on which the doctors reflected upon varied greatly whereby some were mentioned by more than one doctor and some by just one doctor. and Supplementary Appendix 1 gives a few illustrative quotes related to the topics’ themes.

Figure 2. Topic themes in the doctors’ reflection reports - 41 of the 12 doctors’ quotes summarized into 20 themes belonging to the outer and inner world.

Table 3. A selection of illustrative quotes related to the topics’ themes mentioned by the 12 studied doctors.

Lessons the doctors learnt from making the error

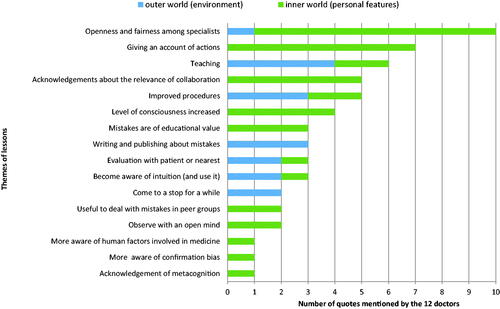

We found 58 quotes by the 12 doctors (range: 2-11) summarized into 16 lessons learnt themes (). Of these lessons learnt, 29% concerned outer world (including environment) and 71% concerned inner world (including personal features) characteristics. Although the lessons learnt after an error tended to vary greatly between the doctors, some lessons were mentioned by more than one doctor. and Supplementary Appendix 2 shows some illustrative quotes related to the lessons.

Figure 3. Lessons learnt themes in the doctors’ reflection reports - 58 quotes by the 12 doctors summarized into 16 lessons learnt themes belonging to the outer and inner world.

Table 4. A selection of illustrative quotes related to the lessons learnt themes mentioned by the 12 studied doctors.

Discussion

This study shows that the triggers which made the 12 studied doctors aware of their errors were mostly death and complications. The topics that the doctors reflected upon to explain the error, and the lessons the doctors learnt from making the error, varied between the doctors and included outer world (environment) and inner world (personal) characteristics. Since reflection can be seen as a cognitive forcing function to minimize errors (Croskerry Citation2013), we discuss two key factors which optimize reflection: the timing and the focus of the reflection.

Timing of reflection

We will discuss the timing of the reflection first because, as shown by this study, most triggers which make doctors aware of their errors come too late. Before our study’s doctors realised that something was wrong, their patient had already died or had already developed a complication. Therefore, we conclude that they did not reflect in time. Although the doctors recognized that the error they had made was due to their own flawed reasoning, they did not get a cue in time to change their mind or behaviour. An explanation for this could be that doctors tend to go with their initial intuitive judgments if not confronted with sufficient conflicting evidence compelling them to change their mind and behaviour (Evans Citation2006; Evans Citation2008; Bazerman and Moore Citation2009). Intuitive judgments belong to the type 1 process of clinical-decision-making. This type 1 process is fast, usually effective, and automatic. As it is largely unconscious, the type 1 process may open the door to errors because automatic judgments cannot be submitted for verification (Croskerry Citation2013). The opposite of the type 1 process is the type 2 process which includes cognitive forcing functions such as reflection (Croskerry Citation2013). Although the type 2 process is fairly reliable, safe and effective, it is also slow and intensive. When we teach doctors to use reflection as a tool to minimize errors, it is very relevant that the doctor detects continuously what is happening during the reasoning process in order to become aware of a factor that might interfere. Reflection as a tool to monitor interfering factors has also been used in other fields, such as in laboratory medicine (Oosterhuis et al. Citation2021) and in psychotherapy (Segal et al. Citation2004). A reason for continuously detecting interfering factors is to raise awareness through mindfulness (Epstein, Citation2017). As mindfulness is not natural in every person in a stressful practice environment (Verweij et al. Citation2018), doctors should be trained to be mindful (Scheepers et al. Citation2020; Sottile Citation2022; Ryznar and Levine Citation2022). When a doctor is able to be mindful and is, at the same time, consciously applying reflection, then s/he might have a timely moment of reflection. By doing this, s/he might be creating a change from reflecting on action to reflecting in action. Such in action reflections might help the doctor to make a close connection between what s/he is doing and what s/he should do (Schön Citation2016), and this creates an opportunity for the doctor to overcome distracting and misleading features (Brush et al. Citation2022).

Focus of reflection

We will now discuss the focus of doctors’ reflections because this study shows that, although there were large variations between the studied doctors’ error topics and lessons learnt, the majority of topics that explained their errors and the majority of lessons they had learnt were related to the doctors’ inner world. It seems as if they felt the full responsibility for the error was located in themselves, and that the outer world was less to blame. Hence we conclude that doctors’ reflections seem personal and unique. Therefore, we hypothesize that when doctors learn more about handling their inner world, they might be able to discover the dynamic modulation in themselves. In response, they can react more adequately to what is happening in the clinical setting. Ilgen et al. described how clinicians’ personal perceptions, e.g. discomfort, is cued by vague somatic or emotional signals such as fear, shame, irritation, that something is wrong (Ilgen et al. Citation2021). Discomfort serves as a warning bell for clinicians to monitor a situation with greater attention and to proceed more intentionally. Responding to the dynamic modulation in oneself means that one creates new possibilities to cope with uncertain situations. Creating possibilities is a fundamental factor in the development of a professional, as it contributes to personal autonomy [Ng et al. Citation2012).

Implications for educational practice

Our study’s conclusions that doctors’ reflections do not occur in time and are personal as well as unique have implications for educational practice. To minimise errors, doctors should be trained in reflecting more in action instead of on action. In addition, doctors need to know themselves better in order to anticipate more adequately what is happening in themselves. How can we train doctors to use reflection more as a tool to consciously apply a metacognitive step? There are several complementary ways to do this. First, we could pass on knowledge by lecturing about topics and lessons learnt after making an error. Second, we could train doctors to be mindful in order to reflect earlier and in time (Sottile Citation2022; Ryznar and Levine Citation2022). Mindfulness necessitates an awareness of what is happening, including self-awareness (Verweij et al. Citation2018). Self-awareness pays attention to a unique person and begins by first assessing one’s degree of presence of own thoughts, doings, feelings and intentions. Examples of training methods to assess one’s degree of presence are self-questioning, concretizing, specifying, differentiating one’s own behaviour, showing one’s vulnerable side and creating a safe atmosphere (Schön Citation2016).

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is the availability of exceptional reflection reports by 12 senior doctors which gave us an insight into the darkest recesses of their minds and behaviours when making medical errors. Another strength is the thorough and systematic analysis of the data following specific steps by researchers who had complementary expertise. Finally, we have added extensive evidence to our study’s results in the form of themes in the figures and quotations in the tables.

This study has some limitations. The first is that the reflection reports were obtained from a limited number of doctors, namely 9 men and 3 women. It means that this might be a non-representative group. Therefore, our findings may not be generalizable to other doctors. Neither can we say anything about gender specific differences of men and women in reflection on errors because of the limited number of doctors. Nevertheless, the quality of this study, including the real-life dimension and the in-depth and consistent analysis, makes the results convincing and valuable for future research. The second limitation is that the doctors reflected years after the error was made. This may have had a memory deformity effect (Gray and Bjorklund Citation2014). However, we argue that reflection is about how events affect people and how people develop themselves following these experiences, as remembered by the person, regardless of whether it really happened exactly as they remembered it. Third, the reflection reports of the clinicians were made 10 to 15 years ago, before medicine became more aware about the influence of reflection as a cognitive forcing function on clinical reasoning. However, we have reason to assume that nowadays reflection during clinical reasoning needs improvement (Brush et al. Citation2022). Fourth, sometimes the validity of the topics that contributed to the errors mentioned by the doctors can be questionable. It is possible for a topic to work out negatively in a certain context, but positively in another context. Finally, the text analysis method used by us might be open to some subjectivity regarding the authors’ interpretations.

Conclusion

The timing and focus of doctors’ reflections are key factors when using reflection as a cognitive strategy to minimize errors. This means that doctors should be trained to reflect whilst in action instead of reflecting on the action, so that they become aware earlier and in time as to which factor might interfere with their clinical reasoning. This awareness creates an opportunity for the doctor to overcome distracting and misleading features. In addition, doctors should discover more about their inner world to identify vulnerable personal features. By being aware of these vulnerable features, they can anticipate more adequately what is happening in themselves during the clinical-decision making process.

Ethical approval

The conducted research is not related to either human or animal use.

Author contributions

All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (68.9 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Helga M. J. Raghoebar-Krieger

Helga M. J. Raghoebar-Krieger, PhD, is an educationalist at the Department of Primary- and Long-term Care, University Medical Center Groningen, The Netherlands.

Pieter C. Barnhoorn

Pieter C. Barnhoorn is a general practitioner and PhD at the Department of Public Health and Primary Care, Leiden University Medical Center, The Netherlands.

Anita A. H. Verhoeven

Anita A. H. Verhoeven, MD, PhD, at the Department of Primary- and Long-term Care, University Medical Center Groningen, The Netherlands.

References

- Ahmed M, Arora S, Carley S, Sevdalis N, Neale G. 2012. Junior doctors’ reflections on patient safety. Postgrad Med J. 88(1037):125–129.

- Barnhoorn PC, Houtlosser M, Ottenhoff-de Jonge MW, Essers GTJM, Numans ME, Kramer AWM. 2019. A practical framework for remediating unprofessional behavior and for developing professionalism competencies and a professional identity. Med Teach. 41(3):303–308.

- Bazerman MH, Moore DA. 2009. Judgment in managerial decision making, 7th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Brush JE, Sherbino J, Norman GR. 2022. Diagnostic reasoning in cardiovascular medicine. BMJ. 376:e064389.

- Buikema M. 2011. When healthcare hurts: doctors share their darkest hours. Sin Loco: Zin Publishing.

- Clapper TC, Ching K. 2020. Debunking the myth that the majority of medical errors are attributed to communication. Med Educ. 54(1):74–81.

- Croskerry P, Singhal G, Mamede S. 2013. Cognitive debiasing 2: impediments to and strategies for change. BMJ Qual Saf. 22(Suppl 2):ii65–ii72.

- Croskerry P. 2003. The importance of cognitive errors in diagnosis and strategies to minimize them. Acad Med. 78(8):775–780.

- Dewey J. 1933. How we think: a restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process. Lexington: Heath.

- Evans JSBT. 2006. The heuristic-analytic theory of reasoning: extension and evaluation. Psychon Bull Rev. 13(3):378–395.

- Evans JSBT. 2008. Dual-processing accounts of reasoning, judgment, and social cognition. Annu Rev Psychol. 59:255–278.

- Epstein R. 2017. Attending medicine, mindfulness, and humanity. New York: Scribner.

- Graber ML, Kissam S, Payne VL, Meyer AND, Sorensen A, Lenfestey N, Tant E, Henriksen K, Labresh K, Singh H. 2012. Cognitive interventions to reduce diagnostic error: a narrative review. BMJ Qual Saf. 21(7):535–557.

- Graber ML. 2013. The incidence of diagnostic error in medicine. BMJ Qual Saf. 22(Suppl 2):ii21–ii27.

- Gray P, Bjorklund DF. 2014. Psychology. New York: Worth Publishers. p. 321–367.

- Hatton N, Smith D. 1995. Reflection in teacher education: towards definition and implementation. Teach Teach Educ. 11(1):33–49.

- Ilgen JS, Teunissen PW, de Bruin ABH, Bowen JL, Regehr G. 2021. Warning bells: how clinicians leverage their discomfort to manage moments of uncertainty. Med Educ. 55(2):233–241.

- Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, editors. 2000. To err is human: building a safer health system. Report of the Institute of Medicine (US). Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US).

- Korthagen FAJ, Wubbels T. 1995. Characteristics of reflective practitioners: towards an operationalization of the concept of reflection. Teach Teach. 1(1):51–72.

- Korthagen FAJ, Kessels JPAM. 1999. Linking theory and practice: changing the pedagogy of teacher education. Educ Res. 28(4):4–17.

- Mamede S, Schmidt HG. 2017. Reflection in medical diagnosis: a literature review. Health Prof Educ. 3(1):15–25.

- Ng JYY, Ntoumanis N, Thøgersen-Ntoumani C, Deci EL, Ryan RM, Duda JL, Williams GC. 2012. Self-determination theory applied to health contexts: a meta-analysis. Perspect Psychol Sci. 7(4):325–340.

- O'Connor P, Lydon S, Mongan O, Connolly F, Mcloughlin A, McVicker L, Byrne D. 2019. A mixed-methods examination of the nature and frequency of medical error among junior doctors. Postgrad Med J. 95(1129):583–589.

- Oosterhuis WP, Venne W v d, Deursen CT, Stoffers HE, Acker BA, Bossuyt PM. 2021. Reflective testing – A randomized controlled trial in primary care patients. Ann Clin Biochem. 58(2):78–85.

- Ryznar E, Levine RB. 2022. Twelve tips for mindful teaching and learning in medical education. Med Teach. 44(3):249–256.

- Scheepers RA, Emke H, Epstein RM, Lombarts KM. 2020. The impact of mindfulness-based interventions on doctors’ well-being and performance: a systematic review. Med Educ. 54(2):138–149.

- Schön DA. 2016. The reflective practitioner: how professionals think in action. London: Routledge.

- Segal ZV, Teasdale JD, Williams JMG. 2004. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy: theoretical rationale and empirical status. In: Hayes SC, Follette VM, Linehan MM, editors. Mindfulness and acceptance: expanding the cognitive-behavioral tradition. New York: Guilford Press. p. 45–65.

- Singh H, Schiff GD, Graber ML, Onakpoya I, Thompson MJ. 2017. The global burden of diagnostic errors in primary care. BMJ Qual Saf. 26(6):484–494.

- Sottile E. 2022. Twelve tips for mindful teaching. Med Teach. 44(1):32–37.

- Verweij H, Van Ravesteijn H, Van Hooff MLM, Lagro-Janssen AL, Speckens AE. 2018. Does mindfulness training enhance the professional development of residents? A qualitative study. Acad Med. 93(9):1335–1340.