Abstract

Background

Disparities in scholarship exist between authors in low- or middle-income countries (LMIC) and high-income countries. Recognizing these disparities in our global network providing pediatric, adolescent, and maternal healthcare to vulnerable populations in LMIC, we sought to improve access and provide resources to address educational needs and ultimately impact the broader scholarship disparity.

Methods

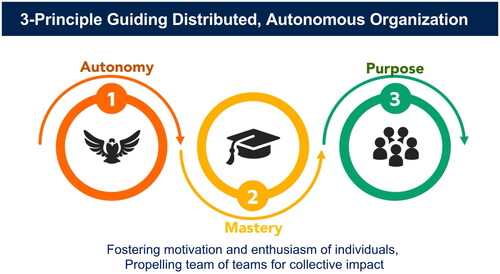

We created a virtual community of practice (CoP) program underpinned by principles from starling murmuration to promote interdisciplinary scholarship. We developed guiding principles- autonomy, mastery and purpose- to direct the Global Health Scholarship Community of Practice Program. Program components included a continuing professional development (CPD) program, an online platform and resource center, a symposium for scholarship showcase, and peer coaching.

Results

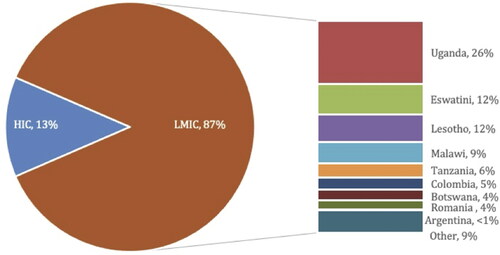

From February 2021 to October 2022, 277 individuals joined. Eighty-seven percent came from LMIC, with 69% from Africa, 6% from South America, and 13% from other LMIC regions. An average of 30 members attended each of the 21 CPD sessions. Thirty-nine authors submitted nine manuscripts for publication. The symposium increased participation of individuals from LMIC and enhanced scholarly skills and capacity. Early outcomes indicate that members learned, shared, and collaborated as scholars using the online platform.

Conclusion

Sharing of knowledge and collaboration globally are feasible through a virtual CoP and offer a benchmark for future sustainable solutions in healthcare capacity building. We recommend such model and virtual platform to promote healthcare education and mentoring across disciplines.

Introduction

Scholarship disparities exist between authors in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) and those in high-income countries (HIC). They affect awareness of health issues impacting LMIC, recognition of expertise within LMIC, resulting funding and resource allocation, and quality of care and treatment. Research has shown that historically, LMIC representation as first and last author positions has been low in global health research, despite data having been collected and produced by researchers in those countries (Cash-Gibson et al. Citation2018). A large-scale analysis of published science-related studies showed evidence of uneven progress towards greater representation: only 12.8% of peer review publications included authors from low-income countries, while 47.3% included authors from upper-middle and 45.1% from lower-middle income countries (Dimitris et al. Citation2021).

Practice points

The guiding principles of autonomy, mastery, and purpose, based on biological insights from the murmuration of starlings, can be applied to improve the robustness of a community of practice.

A scholarship community can thrive when members trust and respect individual boundaries, value diversity as complementarity, and align and commit to a shared purpose.

Program developers can leverage technologies to foster interdisciplinary scholarship via virtual communities of practice that engage and empower scholars from LMIC and thereby advance scholarship equity.

The multifactorial reasons for this are complex and often rooted in systems, including geopolitical context of academic and scientific publishing and the rigorous cycle of donor demands in health systems that rely significantly on international development and aid funding, as is the case in many LMIC (Salager-Meyer Citation2008; Binagwaho et al. 2021). Other reasons relate to underlying education challenges. LMIC researchers and healthcare professionals often lack formal education in managing research projects and publishing in peer-reviewed journals (Busse and August Citation2020). Linguistic disadvantages facing non-native English speakers, lack of scientific writing training or support, and lack of specialized technical and editorial staff to edit manuscripts also pose challenges for LMIC authors (Salager-Meyer Citation2008).

Capacity-building or -enhancing, a term initially emerging from the fields of development and aid, but in this case, refers to the process of increasing skills of staff to ultimately improve practices (Crisp et al. Citation2000). Although numerous LMIC-HIC partnerships supporting scholarly and research capacity-building have been initiated with documented successes and constraints (Färnman et al. Citation2016; Basu et al. Citation2017), benefits from these capacity-building partnerships are unevenly distributed (Blicharska et al. Citation2021). This can be attributed to structural inequities in access to resources, education, and training between institutions in HIC and LMIC, leading to power imbalances, limited ownership, and missed opportunities (Binagwaho et al. Citation2021). Concrete reforms to LMIC-HIC academic global health partnerships have been delineated for equity, accountability, and ultimately addressing inequities facing scholars in LMIC at the individual level (Binagwaho et al. Citation2021).

Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) affiliated with the Baylor College of Medicine International Pediatric AIDS Initiative (BIPAI) Network operate clinics serving more than 365,000 beneficiaries across Argentina, Botswana, Colombia, Eswatini, Lesotho, Malawi, Romania, Tanzania, and Uganda. More than 2,900 locally employed professionals support clinical and programmatic services that provide pediatric and maternal healthcare to vulnerable populations. BIPAI Network headquarters, based in Houston, USA, supports the NGOs through education and capacity-enhancing initiatives.

To address the disparities reflected among local healthcare professional staff in our network of NGOs, we formed the Global Health Scholarship Community of Practice Program (GHS-CoP) for greater access to resources and enhanced learning and peer interaction. The program initiated and sustained global health scholarship among healthcare professionals in LMIC and HIC across the BIPAI Network, with a goal to improve their skills and ultimately the quality of care and treatment provided in the communities they serve. From its inception, the GHS-CoP embraced a commitment to mutual capacity building aligned with educational and training needs of LMIC scholars, reflecting reforms that have been called for in academic global health partnerships (Binagwaho et al. Citation2021). Convening professionals from both LMIC and HIC provided a robust range of scholarly expertise and interests that fostered a rich environment for the GHS-CoP, as well as an opportunity to demonstrate an equitable and mutually beneficial partnership. The GHS-CoP described offers an effective way to do so and serves as a steppingstone for future education and capacity-enhancing programs in other disciplines.

Methods

Theoretical framework

To implement the GHS-CoP program, we adopted the concept of a starling murmuration as a novel framework. Murmuration refers to the phenomenon of thousands of starlings as they fly together, flocking into a display of swirling patterns. Computer simulations (Reynolds Citation1987) and mathematical models (Hildenbrandt et al. Citation2010; Hemelrijk and Hildenbrandt Citation2011) describe how starlings collectively create complex motion and interactions as they follow three basic rules: separation, alignment, and cohesion (Reynolds Citation1987). With no central control, groups of seven neighbouring starlings autonomously separate into self-organized teams, optimizing the balance between group cohesiveness and individual effort. Significantly, such groups can maintain cohesion even when every individual starling is subject to uncertain information about the behaviour of its neighbors as well as disturbances from the environment. This robust group dynamic has significance in evolutional biology and offers implications for social networks (Young et al. Citation2013).

We married these biological insights with the Community of Practice (CoP) framework, a term coined by anthropologists Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger while they were studying apprenticeship as a learning model that refers to a community acting as a living curriculum. CoPs have these three characteristics: a domain, or shared interest that involves commitment and a shared competence that distinguishes the members from others; a community, a group of individuals who build relationships around the domain that enables them to learn from each other; and the practice, a repertoire of shared experiences and ways of affecting an outcome or product (Wenger-Trayner and Wenger-Trayner Citation2015).

Using the murmuration concepts, we formed the overarching GHS-CoP, namely a robust community of scholars, and encouraged smaller CoPs to form by setting up sub-communities with shared interests (the domain), who improved their practices as they interacted regularly. Forming smaller groups around domains, just as the starlings form teams of seven, we sought to optimize the balance between group cohesiveness and individual effort. As the GHS-CoP matured, smaller CoPs also formed spontaneously. We developed guiding principles – autonomy, mastery, and purpose – to establish governance and delineate roles of GHS-CoP members grounded in the three rules of murmuration and to support a purpose-driven organization, the GHS-CoP, composed of distributed autonomous CoPs.

Program components and implementation

Five faculty members in Houston, Malawi, and Uganda formed a GHS-CoP governance and invited multidisciplinary staff interested in scholarly activities to join. We created an online platform, called ‘Virtual Home,’ which serves as a professional network, learning management system, and cloud-based collaboration tool. The Virtual Home houses the continuing professional development (CPD) program and provides members with curated resources to support their scholarly activity (e.g. library services and electronic resources, literature management tools, writing resources, journal-selection guidance, and directories for grants, scientific journals, and scientific conferences). We developed various program components to enhance members’ scholarly activities as illustrated in .

The CPD program consisted of virtual sessions hosted twice monthly: a Core Series of webinars and workshops focused on development of essential scholarly skills and on writing for publication through project-based learning; and a CoPs session of small group activities for exploration of inquiries, formation of collaborations, and scholarship consultations. lists the topics offered in the two Core Series and CoPs sessions. We sponsored a symposium showcasing members’ scholarship, the RAISE (Research. Arts. Innovation. Scholarship. Education) Symposium, which replaced an annual in-person BIPAI Network Meeting. The symposium aimed to foster greater inclusion of participants from LMIC and greater capacity enhancement (Basile et al. Citation2022). The virtual format eliminated the usual professional conference participation barriers facing individuals from LMIC (e.g. travel expense, visa requirements, and protected time away from duty). The RAISE Symposium expanded the audience by implementing live-time presentations and workshop sessions, virtual scientific posters and art exhibits, and interactive engagement strategies. We established a system for peer coaching and support to enable successful submissions of scholarship for the symposium and beyond, which took place over the preceding eight months. All individual submissions to RAISE underwent a double-blinded peer-review process to evaluate their scientific merit, reflecting the standard procedure of most scientific conferences; those that were accepted were chosen for oral presentations, live e-poster, or e-poster formats.

Table 1. Description of GHS-CoP continuing professional development sessions.

At the start of the GHS-CoP, members completed a scholarship-competency inventory, adapted from the Academic Competencies for Medical Faculty by Harris et al. (Citation2007), to advise member baseline skills and identify members with expertise to serve as coaches for small group activities, collaborative projects, and RAISE Symposium activities. Coaching and educational activities designed for the RAISE Symposium aimed to catalyze the exchange of ideas across the BIPAI Network, enhancing authors’ writing skills and capacity, and rendering the traditional scientific abstract showcase more accessible and appealing.

Program evaluation

We examined the contribution of this virtual GHS-CoP on improving global health scholarship through evaluation of the process and products. We surveyed participants at the conclusion of the symposium, the Core Series and CoPs sessions; tracked user analytics of Virtual Home engagement; and assessed outcomes related to the community and practice aspects (e.g. autonomy, mastery, purpose) of GHS-CoP to inform program improvement. We report descriptive outcomes and lessons learned based on data abstracted from the GHS-CoP database as well as survey-based responses.

Results

Participants and geographical representation

From February 2021 to October 2022, 277 members joined the GHS-CoP, with 87% (241 of 277) coming from LMIC. The largest proportions came from Uganda (26%), Lesotho (12%), and Eswatini (12%); 12% of participants came from the United States of America ().

Quantitative program outcomes

Over two years, the GHS-CoP organized 14 workshops, including two Core Series, and seven CoPs sessions, with an average of 30 members attending each session (range, 12–68). The range fluctuated throughout but remained stable when comparing initial to later sessions, thereby suggesting long-term viability. The RAISE Symposium, held in June 2021, showcased 10+ hours of live programming, 74 scientific abstracts, and 101 pieces of artwork, with an average of 120 participants attending each Symposium session. The Symposium increased participation by 366% compared to a previous in-person BIPAI Network Meeting in 2019, with a total of 505 attendees from more than 20 countries; 90% of whom were from LMIC. The affiliated NGO in Malawi was inspired by the original RAISE Symposium and replicated a smaller scale RAISE Symposium in 2022 to showcase local works.

highlights the tangible scholarly outcomes (publications, abstracts, and presentations) from GHS-CoP members. A seven-part Core Series on scholarly writing resulted in 39 authors from eight countries working in small groups to write and publish nine manuscripts on health disparities in LMIC contextualized to the COVID-19 pandemic. For the RAISE Symposium, 20 coaches supported 29 submitting authors, and 90% of those authors reported gains in skills transferable to future submissions (e.g. abstract writing, effective e-poster development, graphic design, effective oral presentation delivery).

Table 2. Tangible scholarly outcomes from GHS-CoP members.

Quantitative and qualitative responses from participants – aggregate responses from sessions

Ninety-seven percent (135 of 139) of respondents reported that GHS-CoP activities provided new or updated their current knowledge, and 97% (140 of 144) indicated they would incorporate information from the Core Series sessions into their current practice. Eighty-percent of respondents favorably rated these Core Series sessions for instructional approaches using deconstructed practicum, interactive virtual didactics, collaborative learning in breakout rooms, and workbook and worksheets for application. They reported the Core Series sessions to be practical and highly interactive: facilitators fostered open dialogue in large and small groups, encouraging active participation and enabling brainstorming. Ninety-three percent (129 of 138) appreciated an increased sense of community and belonging, 95% (56 of 59) reported that the activities during the CoPs sessions provided an opportunity to learn about and from peers, and 88% (52 of 59) highlighted these activities fostered collaboration among members. Participants provided feedback that the Virtual Home was user friendly and enhanced the sense of belonging in a virtual community. highlights what respondents found helpful from open-ended survey evaluation questions conducted in the Core Series and CoPs sessions.

Table 3. Representative quotes from GHS-CoP members describing program.

Discussion

Our study aimed to address the CPD needs of healthcare professionals within the BIPAI Network and to ultimately reduce the disparity in scholarship between authors in LMIC and HIC. To achieve this goal, we created a CoP for scholarship inspired by the principles and insights of starling murmuration. Our results suggest that this innovative CoP model, which fosters distributed, purpose-driven, self-organized teams, can effectively promote interdisciplinary scholarship with publications, abstracts, and presentations among a global CoP spanning ten countries.

The three guiding principles of murmuration, as described below, were critical to our GHS-CoP program and add to the literature on how to sustain CoPs (Buysse et al. Citation2003; Barnett et al. Citation2012) ().

Separation

As starlings avoid crowding their neighbors by maintaining separation, GHS-CoP members need to develop their sense of autonomy. The use of a “scholarship inventory” (Supplemental Content) and the “Milestones for Scholarship” (Mink et al. Citation2018) to identify baseline capacities, interests, and goals helped delineate an individual’s boundary, purpose(s), and role(s). Acknowledging explicit boundaries, which was encouraged by CoPs sessions designed to get to know other members and explore collaborative projects, facilitated formations of CoPs and mutual respect of individuals’ complementary skills. Members must be empowered to put forward initiatives with flexibility to decide how to execute scholarly work (i.e. autonomy), but accountability is necessary to earn autonomy and add value to the CoPs.

Allowing individual members some level of independence while being responsible to the group is a delicate balance that ignites creative ideas. We have noticed this delicate equilibrium at play in some writing groups. These groups grappled with a mix of individuals, each with their own level of skill and commitment. This disparity can potentially undermine the team’s collaborative spirit. Unlike starlings, the uniqueness of human nature, imbuing us with autonomy, power, and agency (Cristancho Citation2021), may add limitations to the CoP dynamics. When dissension is perceived, the governance should refrain from interfering and allow the group to balance autonomy and accountability, and, thereby, ultimately foster collective leadership and equity.

Cohesion

Starlings maintain cohesion by steering towards the average position of neighbors, whereas GHS-CoP members contribute to cohesion by developing mastery within the shared domain. Cohesion requires cultivating a culture of respect, trust, and psychological safety. Embracing intellectual honesty promotes a culture of learning, innovation, and sustained improvement. Within a brave and safe space, members celebrate successes, examine progress or disappointments through reflective practices, and lean on the collective strength of the CoPs (Luhanga et al. Citation2021). Members are encouraged to share perceived gaps, a difference between what is and what could be, or tensions between members to identify opportunities to enhance efficiency. A CoP that thrives despite differences in backgrounds, skills, and attitudes is one that gain complementarity and transform tensions into agility.

Self-assessments by all members at the conception were critical. Acknowledging their diverse skill levels, members could promote individual goal-setting for desired mastery and enhance cohesiveness. Our Core Series provided a knowledge base for expedient mastery in conjunction with the CoPs sessions, in which engaged members shared and learned through working on collaborative projects, a key feature for successful CoPs (Probst and Borzillo Citation2008, de Carvalho-Filho et al. Citation2020).

Alignment

As the average direction of starlings maintains alignment, a shared purpose drives GHS-CoP members towards collective behaviors. Unlike policies and rigid rules, clear purpose fosters motivation, creativity, and enthusiasm, the enablers of transferring knowledge to practice (Luhanga et al. Citation2021). Engaging in scholarly activities may seem daunting to some people, so members are encouraged to set smaller goals on the journey to acquire, practice, and master scholarly skills (de Carvalho-Filho et al. Citation2020). Keeping focused on tangible goals while maintaining view of the broader context helps formulate interdependent efforts to achieve the larger GHS-CoP purpose.

CoP dynamics: The lessons learned in writing groups

During one CoPs session, we organized a Coffee and Conversation to inspire organic collaborations through socialization, resulting in the formation of smaller CoPs that, in turn, strengthened the GHS-CoP as a whole. This was fully realized when we helped form CoPs writing groups to submit manuscripts for a journal: a clear purpose for a tangible product.

Collaboration within a multidisciplinary group of professionals working in different countries required more time for members to understand and appreciate each other’s skills, workplace obligations, and communication styles. However, openness to sharing and flexibility with work culture and time diversity enabled each writing group to develop realistic expectations and timelines for themselves. This contributed to equitable distribution of the work and meeting defined criteria for authorship while remaining sensitive to individuals’ baseline skills and commitments. For example, one group had three members who anticipated going on maternity leave during the writing project, and so they staggered their responsibilities across the timespan of preparing the manuscript accordingly. Groups also capitalized on members’ location across several time zones to optimize work efficiency in a relay race fashion–Members who were ahead in time would work on the project first and then turn it over to members who were behind so that maximal work was consolidated into a 24-h period.

It was important for members to know their individual roles or contributions within smaller CoPs (autonomy). Members who emerged as leaders in the writing project were recognized for their efforts in authorship, earning autonomy through accountability. As members actively worked on writing projects, members’ strengths and weaknesses emerged, and members willingly supported each other to form their collective mastery. Changing roles is acceptable in this dynamic group setting, and CoPs that thrived were able to adapt to the morphing nature of collaborations and roles, leading to sustained cohesion and completed writing projects. Multiple factors contribute to this agility, including a common purpose binding them around project goal.

These CoPs exemplify grassroots efforts to empower individuals one-by-one with the confidence and skills to amplify their voices through dissemination of their work highlighting the health priorities and needs of the communities they serve. This is a prime example of the bottom-up organizational approach to capacity building (Crisp et al. Citation2000). This approach aims to reduce scholarship disparity between authors in LMIC and HIC and build momentum of scholarship representation of health professionals in LMIC to address health disparities facing their communities.

Conclusion

Murmuration is critical to the survival of starlings. It helps them evade predators, exchange information, and huddle for warmth over their roost (RSPB Citation2022). Engaging in scholarly activities can be challenging, sometimes ancillary to day-to-day job obligations, and imposes difficult demands for continuing focus and commitment. Our murmuration-inspired model of a CoP leverages synergy of robust group dynamics, empowerment, and technical and personnel supports to coordinate resources and access for healthcare professionals globally. As the beauty of murmuration is beyond what any individual starling can create, so the value of this powerful community reflects an axiom that ‘the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.’

Program limitations and strengths

Our program had some limitations: We recognize that participants of the GHS-CoP joined voluntarily and that survey responses may skew answers toward positive feedback. Program evaluations have not investigated long-term outcomes of the GHS-CoP.

Ethical approval

The study of this program has been approved by the Baylor College of Medicine institutional review board.

Authors’ contribution

Conceptualization: DN, ST, RNS, BLL; Data curation: DN, ST; Methodology and Formal Analysis: DN, ST, JB; Project Administration: DN; Writing Original Draft: DN, ST, RNS KH, RNS, AM, JB; Review and Editing: DN, ST, BLL, RNS, KH, AM, JB. All authors read and approved the manuscript. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of BIPAI.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (88.9 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all GHS-CoP Program members for their participation and the leadership of the BIPAI Network and respective affiliated NGOs for their support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current program evaluation are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Diane Nguyen

Diane Nguyen, PharmD, is an Assistant Professor at Baylor College of Medicine and associate director for the Center for Research, Innovation and Scholarship in Health Professions Education. She was formerly director of global programs for BIPAI at the inception of this project.

Rogers N. Ssebunya

Rogers N. Ssebunya, MPH(Epi), PGDM&E, serves as technical lead for Program Outcomes, Evaluations and Operations Research at Baylor College of Medicine Children’s Foundation-Uganda.

Kajal Hirani

Kajal Hirani, PhD, FRACP, MBBS, is a Consultant Pediatrician and Adolescent Medicine Physician working at Baylor College of Medicine Children’s Foundation-Malawi during this project.

Anna Mandalakas

Anna Mandalakas, MD, MSEpi, PhD, is a Professor at Baylor College of Medicine and chief of the Division of Global and Immigrant Health.

Jennifer Benjamin

Jennifer Benjamin, MD, MS, is an Associate Professor at Baylor College of Medicine and technology director for the Center for Research, Innovation and Scholarship in Health Professions Education.

B. Lee Ligon

B. Lee Ligon, PhD, MA, MA, MAR, is an Instructor/Department Editor at Baylor College of Medicine and Director of Publications for the Center for Research, Innovation, and Scholarship in Health Professions Education.

Satid Thammasitboon

Satid Thammasitboon, MD, MHPE, is an Associate Professor at the Texas Children’s Hospital, Baylor College of Medicine and the director for the Center for Research, Innovation and Scholarship in Health Professions Education.

References

- Barnett S, Jones S, Bennet S, Iverson D, Bonney A. 2012. General practice training and virtual communities of practice – a review of the literature. BMC Fam Pract. 13:87.

- Basile F, Petrus J, Gates C, Perry S, Benjamin J, McKenzie K, Hirani K, Huynh C, Anabwani-Richter F, Haq H, et al. 2022. Increasing access to a global health conference and enhancing research capacity: using an interdisciplinary approach and virtual spaces in an international community of practice. J Glob Health. 12:03038. doi: 10.7189/jogh.12.03038.

- Basu L, Pronovost P, Molello NE, Syed S, Wu A. 2017. The role of south-north partnerships in promoting shared learning and knowledge transfer. Global Health. 13(1):64. doi: 10.1186/s12992-017-0289-6.

- Binagwaho A, Allotey P, Sangano E, Ekström AM, Martin K. 2021. A call to action to reform academic global health partnerships. BMJ. 375:n2658 10.1136/bmj.n2658.

- Busse C, August E. 2020. Addressing power imbalances in global health: Pre-Publication Support Services (PREPSS) for authors in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Health. 5(2):e002323. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002323.

- Buysse V, Sparkman KL, Wesley PW. 2003. Communities of practice: connecting what we know. Except Child. 69(3):263–277. doi: 10.1177/001440290306900301.

- Cash-Gibson L, Rojas-Gualdrón DF, Pericàs JM, Benach J. 2018. Inequalities in global health inequalities research: A 50-year bibliometric analysis (1966-2015). PLoS One. 13(1):e0191901 10.1371/journal.pone.0191901.

- Crisp B, Swerissen H, Duckett S. 2000. Four approaches to capacity building in health: consequences for measurement and accountability. Health Promot Int. 15(2):99–107. doi: 10.1093/heapro/15.2.99.

- Cristancho S. 2021. On collective self-healing and traces: how can swarm intelligence help us think differently about team adaptation? Med Educ. 55(4):441–447. doi: 10.1111/medu.14358.

- de Carvalho-Filho MA, Tio RA, Steinert Y. 2020. Twelve tips for implementing a community of practice for faculty development. Med Teach. 42(2):143–149. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1552782.

- Dimitris M, Gittings M, King N. 2021. How global is global health research? A large-scale analysis of trends in authorship. BMJ Glob Health. 6(1):e003758. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020003758.

- Färnman R, Diwan V, Zwarenstein M, Atkins S. 2016. Successes and challenges of north-south partnerships-key lessons from the African/Asian Regional Capacity Development projects. Glob Health Action. 9(1):30522. doi: 10.3402/gha.v9.30522.

- Harris DL, Krause KC, Parich DC, Smith MU. 2007. Academic competencies for medical faculty. Fam Med. 39:343–350.

- Hemelrijk C, Hildenbrandt H. 2011. Some causes of the variable shape of flocks of birds. PLoS One. 6(8):e22479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022479.

- Hildenbrandt H, Carere C, Hemelrijk C. 2010. Self-organized aerial displays of thousands of starlings: a model. Behav. Ecol. 21(6):1349–1359. doi: 10.1093/beheco/arq149.

- Luhanga U, Chen W, Minor S, Drowos J, Berry A, Rudd M, Gupta S, Bailey J. 2021. Promoting transfer of learning to practice in online continuing professional development. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 0(0):1–5.

- Mink R, Myers A, Turner D, Carraccio C. 2018. Competencies, milestones, and a level of supervision scale for entrustable professional activities for scholarship. Acad Med. 93(11):1668–1672. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002353.

- Probst G, Borzillo S. 2008. Why communities of practice succeed and why they fail. Eur. Manag. J. 26(5):335–347. doi: 10.1016/j.emj.2008.05.003.

- Reynolds C. 1987. Flocks, herds and schools: a distributed behavioral model. SIGGRAPH Comput Graph. 21(4):25–34. doi: 10.1145/37402.37406.

- RSPB. 2022. Starling murmurations. [accessed 2022 Apr 22]. https://www.rspb.org.uk/birds-and-wildlife/wildlife-guides/bird-a-z/starling/starling-murmurations/.

- Salager-Meyer F. 2008. Scientific publishing in developing countries: Challenges for the future. Journal of English for Academic Purposes. 7(2):121–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jeap.2008.03.009.

- Wenger-Trayner E, Wenger-Trayner B. 2015. Introduction to communities of practice: a brief overview of the concept and its use; [accessed 2023 March 22]. https://www.wenger-trayner.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/15-06-Brief-introduction-to-communities-of-practice.pdf.

- Young G, Scardovi L, Cavagna A, Giardina I, Leonard N. 2013. Starling flock networks manage uncertainty in consensus at low cost. PLoS Comput Biol. 9(1):e1002894. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002894.