ABSTRACT

This article examines a largely unexplored component of China’s classical garden system—the gardens of salt merchants in Tianjin during the Qing Dynasty (1636–1911). Beyond existing works, which tend to focus on imperial and scholar gardens—gardens of the ruling elites—this examination of merchant gardens contributes to garden history by revealing that merchants created gardens to improve their low social status. It further reveals shifts in the functions, architectural design and flora of the gardens which reflects both individual aesthetics and the changing fortunes of Tianjin’s salt merchants in general. Salt merchant gardens in Tianjin initially presented idyllic scenery to create literary-based, self-immersed spaces. Then beginning in the 1720s, they evolved into a showcase of rising merchant power displaying affluence, thereby enabling merchants to improve their social rank. Finally, from the 1840s, salt merchant gardens gradually became extravagant enclosures as the collapse of the established social structure unfolded.

Existing studies of Chinese garden history often focus on gardens located in Jiangnan and Beijing, subsuming these two different regions as examples of imperial gardens in both the north of China and the gardens of the scholarly class in the south to discuss the history of and develop the theory on Chinese gardens. If imperial gardens and scholar gardens were the only classic Chinese gardens, this may be adequate. However, merchant gardens also form an important part of the history of Chinese classical gardens, and these have not received enough attention from academia. Scholarship which does mention merchant gardens usually focuses on the Hong gardens in Guangzhou, or salt merchant gardens in Yangzhou, in order to examine and compare their ‘flourishing’ designed landscape with similar art and aesthetics in imperial gardens and scholar gardens (Finnane, Citation2004; Hrdličková, Citation2009; Richard, Citation2015). They neglect to consider the particular ownership of and impetus behind the gardens. Distinguished from scholars and the imperial class, merchants occupied a unique position in the hierarchical culture of traditional Chinese society—they were wealthy but of low rank. Hence, being placed where the owner could seek release from the irritations, frustrations, and discord of life, the merchant gardens were not only developed as leisure spaces, similar to the gardens of scholars and the imperial class, but also as unique spaces to meet the merchant’s desire to elevate their social status (Clunas, Citation1996, p. 12).

During the Qing Dynasty (1636–1911), most merchant gardens were created and owned by salt merchants. Distinguished from the administration of the salt trade in France, the Habsburg Empire, and Venice, the Qing court undertook a syndicate system on salt trade, that is, the government granted each merchant the exclusive right to transport and sell salt within a particular region. Consequently, this monopoly made salt merchants among the wealthiest people in the nation (T. Zhang, Citation1884, p. 40). On the one hand, their large fortunes frequently caused friction within the established social order and this was reflected in state policies, regulations and gabelles, or taxes, on the salt trade. On the other hand, their wealth created a solid economic foundation for developing their own spaces, driving them to construct gardens, physical places and living spaces, which reflected the owners’ rise and fall over time (Kwan, Citation2001, p. 8). Since official permission was the prerequisite for claiming a monopoly over an area, political patronage, rather than salt prices, became the key to success in the syndicate system (Puk, Citation2016, p. 159). Hence, of all salt merchants in China, those of Changlu, who supplied the whole of the capital Beijing and its surroundings, cultivated the closest association with the imperial government and its changing policies (Adshead, Citation1992, p. 125).

Through an examination of the evolution of salt merchant gardens in Tianjin—the commercial and administrative heart of Changlu—during the Qing Dynasty, this article explores how the salt merchants’ struggle with changing state policies and the local social and cultural order shaped their gardens: framing the layouts, architectural constructions and flora, and social activities within them. In doing so, it will contribute to the understanding of gardens as a product of space and time influenced by ongoing interactions and power relations, and will highlight gardens as a diachronic reference to analyse their owners’ place in society.

The salt merchants of Tianjin

Tianjin cemented its status as a trade centre long ago. Historically, it was well known as the second largest industrial and commercial city in China after Shanghai. Tianjin housed up to nine foreign settlements, including France, Great Britain and the United States, during the late imperial and early republic eras as a consequence of its being opened as a treaty port in 1860. Even long before its success as a cosmopolitan centre, this city had already been a key trading hub of northern China with its advantageous location at the confluence of the Grand Canal and the Haihe River, and its 200-kilometre proximity to China’s capital, Beijing. Importantly, Tianjin was also the commercial centre of Changlu Saltern—the largest and the oldest saltern in China (Meng, Citation1992, p.98).

Tianjin itself has never produced any salt. Instead, Tianjin served as the transhipment and transportation centre of the salt trade in Changlu in the early seventeenth century. Salt merchants in Changlu, taking advantage of Tianjin’s availability of transport, shipped the salt from the surrounding salterns to Tianjin by water, and then distributed the salt from Tianjin for transport to other provinces (Puk, Citation2016, pp. 150–1). To improve administrative procedures, the office of Changlu Gabelle Censorate (Changlu Xunyan Yushi) relocated from Beijing to Tianjin in 1668 (Xu, Citation1998, p. 37). Tianjin subsequently became the administrative centre of the salt trade in the mid-seventeenth century, with an even greater number of salt merchants settling in this city.

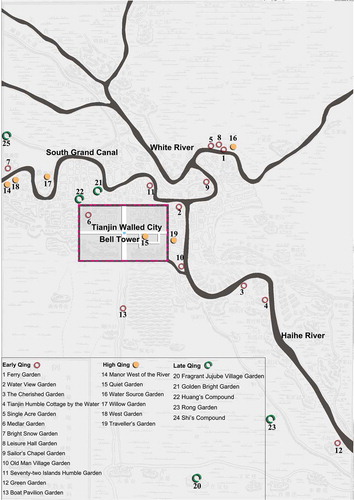

Wealthy salt merchants used their capital to purchase real estate, which set the stage for the emergence of a number of salt merchant gardens. According to the records of local chronicles and private notes and poems, there were more than 20 salt merchant gardens existing in Tianjin during the Qing Dynasty. [ and ] These include Manor West of the River, one of the three renowned private gardens of the Qing Dynasty,Footnote1 Water View Garden, and Ferry Garden which was poetically referred to as a small ‘Pleasant Place of Jade Mountain’ (xiao yu shan)Footnote2 (H. Wang, Citation1739, p. 56; H. Wu, Citation1870, p. 77).

Table 1. Salt merchant gardens in Tianjin (Drawn by author).

Arcadia of the literati: early Qing Dynasty (1636-1725)

For much of ancient Chinse history, society was made up of a hierarchy based on occupation. According to the social order from ‘high’ to ‘low’, occupations were classified into four categories: scholar-officials, farmers, artisans and merchants. While this cultural stratification placed merchants as socially inferior, becoming a literato was seen as the only way to improve social standing (Liu, Citation1995, p. 73). Beginning in the early seventeenth century, some merchants sought to imitate the culture, value orientation and lifestyle of the literati, and to associate with them (Xia, Citation1993, p. 61). This became customary among the salt merchants in early Qing Tianjin. For example, Zhang Shu made friends with scholarly Buddhist and Taoist priests and ‘visited them to co-create poems’ (L. Gao, Citation1931, p. 745). Jin Yugang not only praised the moral quality of the tenth century hermit Lin Bu (967–1028) and imitated him as his model, but also made several thousand-kilometre journeys to ‘Gushan, Hangzhou, to worship in Lin’s cemetery, in spite of snow’ (L. Gao, Citation1931, p. 768).Footnote3

Salt merchants adopted the styles and preferences of the literati for their gardens. The literati had adopted the philosophy of Confucius which emphasised a natural living space, stating: ‘The wise find pleasure in water; the virtuous find pleasure in hills.’ The literati thus determined to create this natural living space whether they lived in the remote countryside or in a crowded city (Han, Citation2012, pp. 297–298). Similarly, the salt merchants sought to design their landscapes with such natural environments. Since Tianjin had abundant river resources, it became popular to obtain sites in the countryside along the river. For instance, Liang Hong developed his garden, Seventy-two Islands Humble Garden, where he could hear the waves of the river (S. Zhang, Citation1824b, p. 22). Zhang Lin constructed his designed landscape, Ferry Garden, at a place where the garden gates opened towards the river (H. Wu, Citation1870, p. 77). Jin Yugang designed his site, Medlar Garden, so it could be directly reached by boat (H. Wu, Citation1870, p. 245).

The salt merchants of this period created relatively small gardens. Old Man Village Garden occupied ‘only five acres’; Single-Acre Garden, as its name suggests, was only one acre; and Medlar Garden was a ‘small garden’ (L. Gao, Citation1931, p. 768). Even Zhang Lin’s renowned garden, Leisure Hall Garden, was not big. Zhang complained in his essay Replanting Willows in the Leisure Hall Garden that ‘there was no place to plant trees’, after painstakingly replanting ‘seven willows’ into the garden (S. Zhang, Citation1991, p. 5). Therefore, the salt merchants sought to merge their gardens into the surrounding natural landscape, blurring the borders of the gardens. They especially used the riverscape outside of the gardens as significant elements of their garden design. Long Zhen thought his garden, Old Man Village Garden, was an excellent place to sit and enjoy an idyllic scene, where he saw ‘children washing vegetables on the island, while melon farmers [were] going across the plateau’ (Long, Citation1824, p. 34). Zhang Lin ‘enjoyed a view of irregular sailboats on the river outside, through a pleasing gap between the trees’ from inside Ferry Garden (H. Wu, Citation1870, p. 77). With this interplay between the inside and outside landscapes, the salt merchants enjoyed the pleasure of sharing in the natural environment outside while remaining within their gardens.

Gardens of the literati were traditionally designed to follow nature’s inherent contours to make the most of an existing site (Keswick & Jencks, Citation1978, p. 76). The salt merchants developed little buildings in their gardens to do this. Ferry Garden had ‘a small group of pools and pavilions’ (H. Wu, Citation1870, p. 239); the Tianjin Humble Cottage by the Water was constructed on uncultivated land and the buildings in the garden were made from simple materials, such as ‘thatch’, ‘hay’ and ‘firewood’ (Hua, Citation1879, p. 186). In Medlar Garden, Jin Yugang used bamboo and grass to build the main pavilion, Yellow Bamboo Mountain Chamber (Huangzhu shanfang) (L. Gao, Citation1931, p. 768). Although the buildings in Sailor’s Chapel Garden were given exalted names such as Lyre and Sea Hall (Qinhai Tang), Cloud Hut (Yun An), Farming and Reading Hall (Gengyue Tang), and Poem and Star Belvedere (Shixing Ge), they were all simply thatched huts (H. Wang, Citation1739, p. 50; H. Wu, Citation1870, p. 77). Consequently, the architectural constructions in the gardens were always juxtaposed with a view of ‘fleabane window’, ‘thatched chapel’, ‘grass pavilion’ and ‘firewood gate’, to frame an image of natural wildness.

Likewise, the plant arrangements became another way salt merchants could produce natural scenery. Among the existing records of these gardens, it is very common to see ‘melon seeding’, ‘bean leaves’, ‘reeds’, ‘lotus’, ‘rye’, ‘cirrus’, ‘flew wild rice’, and ‘pampas grass’, as well as other flora mentioned in historic pastoral poems. It was said of Song Jiushan’s Boat Pavilion Garden, ‘lotus surrounded the pavilion, as gorgeous as if it had been embroidered’ (H. Wu, Citation1870, p. 78). Zhang Shu’s Sailor’s Chapel Garden presented a view of a ‘cottage among the melon fields’ (S. Zhang, Citation1824a). On ‘entering through the gate of the garden’ Tianjin Water Humble Cottage by the Water, one saw ‘an expanse of bulrush and lotus’ (H. Wu, Citation1870, p. 77). These wild, natural scenes were in reality meticulously designed, costly, propagated landscapes. Zhang Lin noted he spared no effort to create such views for his Leisure Hall Garden. ‘Since [this] garden was not located in the mountains, that place could not be secluded enough, even though it was leisurely (sic)’. Thus, ‘replanting willows into the garden’ became a way to fix this deficiency, even though ‘there were no willows in Tianjin, and thus willows were the most expensive [trees]’ (S. Zhang, Citation1991, p. 4). Furthermore, to develop his garden as a secluded place, Zhang not only ‘carried willows in from the gate’ and ‘across the rooftop’, but also dismantled a wall (S. Zhang, Citation1991, p. 4).

In addition to creating ideal natural landscapes, the salt merchants pursued literary interests in their gardens. ‘Elegant gathering’ is a term used to describe the traditional, refined activity of scholars throughout Chinese history. Since Wang Xizhi (303–361), a Chinese writer and calligrapher, enjoyed an ‘elegant gathering’ at Orchid Pavilion in the 3rd century, the Chinese literati were keen to hold their own gatherings to chant poems and enjoy banquets in this garden. Likewise, the salt merchants held such gatherings in their own gardens in early Qing Tianjin. Zhang Shu and Liang Hong always invited each other to gather in their gardens, Sailor’s Chapel Garden and Seventy-two Islands Humble Garden. Apart from other salt merchants, the guests often included a number of local literati, such as the poet and scholar Zhu Yizun (1629–1709), the poet Wu Wen (1644–1704), and the calligrapher and historian Jiang Chenying (1628–1699) (L. Gao, Citation1931, p. 755). Long Zhen, a salt merchant and a frequenter of such gatherings, reported:

[Zhang and his guests] hold elegant gatherings—sometimes every one or two days and sometimes every ten days. At times they begin early in the day and end well into the night. During these gatherings, [they] enjoy writing poems using designated titles and then revise each other’s work. (Long, Citation1886, p. 21)

Afterwards, the merchants compiled their poems into books and published them with titles which included the names of their gardens. For example, Zhang Lin’s The Draft of Leisure Hall Garden (Suixian Tang Gao), Jin Yugang’s The Poems of Yellow Bamboo Mountain Chamber (Huangzhu Wenfang Shichao Shichao), and Zhang Shu’s Poetry Draft of Green Gorgeous Pavilion (Lvyan Ting Shiwengao) and Draft of Sailor’s Chapel Garden (Fanzhai Yigao) (song, Citation1930, pp. 351–352).

The salt merchants also used gardens as a place to exhibit their art and antique collections. Traditionally, exhibiting art and antique collections were significant cultural activities which took place in the gardens of the Chinese scholarly class. Wen Zhenheng (1470–1559), a famous scholar and painter in the sixteenth century, noted that only ‘a collection of art, antiques and books’ could ‘give the owners, dwellers, and visitors non-stop indulgence in pleasures (sic)’ in a garden (Wen & Chen, Citation1984, p. 18). An Qi’s Tianjin Humble Cottage by the Water exhibited ‘Ding and Yi’Footnote4 (H. Wu, Citation1870, p. 77). He attempted to match contemporaries by obtaining renowned historic artefacts from private libraries and collections, such as Xiang Zijing’s (1525–1590) Sound of Nature Belvedere (Tianlai Ge) of the sixteenth century and Ni Zang’s (1301–1374) Pure and Quiet Belvedere (Qingmi Ge) of the fourteenth century (H. Wu, Citation1870, p. 77). Likewise, in the hall in Leisure Hall Garden, Zhang Lin exhibited a great collection of books, ‘the vast number of which forced both the historic and contemporary collectors to acknowledge its superiority’ (W. Wu, Citation1774, p. 11). Although these descriptions perhaps contain a dose of literary hyperbole, they do indicate that the salt merchants obtained vast collections to display in their gardens.

By adopting the tastes of the literati for their gardens, the salt merchants established social ties with the literati, bridging the distance between them. More than that, these gardens, an arcadia of the literati, provided the salt merchants with self-immersive spaces—an opportunity to reflect and become absorbed in their own interests.

A showcase of power: high Qing Dynasty (1725-1840)

The early eighteenth century witnessed a change to the social standing of salt merchants. The Changlu salt merchants donated one hundred thousand tael of silver to the Qing court in 1725, and consequently the court implemented a ‘reciprocating donations system’ (baoxiao) for salt merchants. That is, when salt merchants donated money to the court, provided the army with munitions, donated towards disaster relief, or funded the imperial household, they received financial payoffs, official ranking or titular honours in return (Yan, Citation2015, p. 18; Zhao, Citation1976, p. 3613). This practice both brought enormous wealth to the court and empowered the salt merchants with a new tool to improve their social rank. Consequently, rather than emulating the literati, the salt merchants exchanged material wealth for social capital, hoping to access higher social status and add to their personal fortunes.

This led them to create gardens which would showcase their present and potential earning power. To better cultivate relationships with officials and local society, the salt merchants deliberately developed their gardens in town sites rather than along waterways. Yang Bingyue’s Quiet Garden was located at the southeast of the Bell Tower in the heart of Tianjin (Hua, Citation1879, p. 190). Li Chongcheng’s Traveller’s Garden was situated outside the county seat’s east gate (L. Gao, Citation1931, p. 1053). To reflect their wealth, the salt merchants increased the size of their gardens. For example, Tong Kuiyuan’s Fragrant Jujube Village Garden covered ‘several acres’, and Zha Riqian’s Manor West of the River occupied ‘hundreds of acres’ (L. Gao, Citation1922, p. 736, Citation1931, p. 1053).

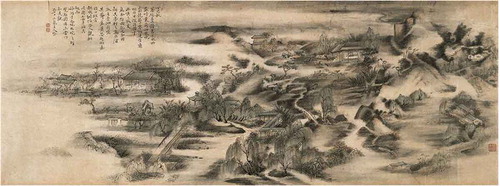

Removed from natural scenery, the gardens could no longer merge with their surroundings to create large-scale designed landscapes with natural environments. Instead, the salt merchants drew attention to the landscapes inside the gardens, developing artificial constructions isolated from the outside, which both represented the wealth of the owners and created a natural environment. This was embodied in the Manor West of the River. Although located at the junction of three rivers, the owner, Zha Riqian, constructed walls along the boundaries to separate the garden from the surroundings, and built massive constructions in the garden, creating ‘halls, pavilions, towers, terraces, bridges and boats’ (H. Wu, Citation1870, p. 78). [] His extraordinary feat brought him great honour, and Manor West of the River was described as including all ‘the spectaculars of Tianjin in one enclosure’ and celebrated as one of the three renowned private gardens. Zha Riqian thus gained a formidable reputation (H. Wu, Citation1870, p. 78).

Figure 2. Zhu Min. A view of reading book at Manor West of the River in the autumn night rain. Tianjin Museum.

Consequently, architectural constructions became dominant elements of the gardens. The salt merchants used buildings, rockeries, pools, plants and other landscape elements to create specific scenes. The various functions, elements and buildings framed the main body of the gardens. Manor West of the River had more than one hundred architectural constructions, such as Water Lyre Mountain Painting Hall (Shuiqin shanhua Tang), Night Moon Covered Walkway (Yeyue Lang), Fragrant Lotus Gazebo (Ouxiang Xie), and Sails Accounting Terrace (Shufan Tai) (H. Wang, Citation1739, p. 55). Zha Weiren explained the complex construction process, stating that they ‘piled up rockeries to form artificial mountains, excavated earth to form pools, and prepared white wood for constructing buildings’ (Zha, Citation1743, p. 11). Likewise, in Traveller’s Garden, most of its Ten Views were architectural constructions, such as Listening Moon Tower (Tingyue Lou), and Fragrant Jujube Library (Zaoxiang Shuwu), which, through the organisation of these buildings, formed an ‘elegant landscape’ (Hua, Citation1886, p. 7).

The architectural constructions presented abundant forms. Apart from pavilions, terraces and halls, which had emerged in the early Qing Dynasty, the salt merchants introduced galleries, boats, houses, bridges, huts, and gate towers into the gardens. Interestingly, artificial rockeries, being an element rarely mentioned in the records of early Qing Tianjin, also emerged in the gardens at this time. According to the master plan of Quiet Garden in the Sequel to Annals of Tianjin County, an artificial rockery was the centrepiece of the garden. As shows, this rockery was not only visible throughout much of the garden, but also framed several views, such as House Entered Peak (Rushi Feng), Lap Held Stone (Baoxi Shi), and Cloud Rested Hole (Suyun Dong) (L. Gao, Citation1931, p. 1053; H. Wu, Citation1870, p. 268). []

Figure 3. Amaster plan of Quiet Garden. Sequel to Annals of Tianjin County (1870), Tianjin. (1. Nuancui Feng 2. Youlan Gu 3. Jikuang Ting 4. Yiyun Lang 5. Suyun Dong 6. Zijun Jing 7. Guanyu Chi 8. Rushi Feng 9. Chenghuai Tang 10. Yingbi)

As well as complex architectural constructions, the flora in the gardens became another way to showcase the wealth and refinement of the owners. Instead of replicating natural scenes, the salt merchants created imagined landscapes in their gardens. For example, in Traveller’s Garden, Yang Bingyue made a square pool planted with lotus and named it Planting Aromatic Canal (Zhongxiang Qu) (L. Gao, Citation1931, p. 1053). In the Manor West of the River, the Zha family introduced bamboo plants and chrysanthemums from the Jiangnan region one thousand kilometres away from Tianjin, and even from Japan, to create a bamboo forest-like scene, named Embroidering Natural Entertainment Side Room (Xiuye Yi) (H. Wang, Citation1739, pp. 47–48; Zha, Citation1743, p. 12). To ensure plantain, orchids and other plants survived the winter, the Zha family developed a conservatory in the garden (Guo et al., Citation2008, p. 88). The merchants deliberately integrated flora into the architectural constructions. For example, Zha ‘planted bamboo under the shadow of the eaves and cultivated a variety of flowers along the steps’ to create a scene where ‘flowers and bamboo presented an image of prosperity in [all] seasons (sic)’ (H. Wu, Citation1870, p. 78; Zha, Citation1743, p. 11).

By creating delicate, artificial landscapes using complicated architectural constructions and exotic flora, the salt merchant gardens not only presented a superficial extravagance, but also represented power and the wealth behind that power. Meyer-Fong, in her discussion of the cultural history of Yangzhou, highlighted the fact that the salt merchants in Yangzhou, through the creation of the triumph of spectacle, ingratiated themselves with the emperors as they looked to the capital for inspiration (Meyer-Fong, Citation2003, pp. 165–97). Likewise, the salt merchants in Tianjin employed their gardens as a tool to develop their political and cultural networks. However, beyond the emperors, they invited a wider social circle to the gardens in an effort to ingratiate themselves with other influential people. In addition to the elegant gatherings, the owners frequently held grand garden parties. Li Chengchong and Zhang Yingchen often hosted large-scale garden parties in their gardens, Traveller’s Garden and Water Source Garden. The scale of garden parties in the Manor West of the River garden were even more striking. A participant of one such garden party, the grand secretary and prime minister of the court, Chen Yuanlong (1686–1774), recalled:

Typically, once a well-regarded person passed by Tianjin and expressed his wish to visit the garden, Zhas would invite him to join the garden parties and enjoy first-class entertainment … During the parties, both the owners and the invited passers-by drank nonstop well into the night. (Chen, Citation1733, p. 78)

Although the idea that any well-regarded person would join the garden parties whenever he passed by Tianjin was perhaps an exaggeration, participants included all levels of leading literati. Apart from Chen Yuanlong, guests included the assistant minister, Qian Chenqun (1686–1774); the scholars Hang Shijun (1696–1773) and Zhao Zhixin (1695–1744); the poet Li E (1692–1752); and the famous Buddhist, Yuanhong (1658-?). Even Emperor Qianlong (1711–1799) visited Manor West of the River four times and inscribed the name ‘Jieyuan’ (Mustard Garden) to name a part of the garden. By means of these grand garden parties, the salt merchants not only gained spiritual pleasure and elevated social reputations, but also, through these powerful guests, attained a higher social position, opening the way for them to influence policy changes to further their own fortunes.

That is not to say that the salt merchants ignored the literary pursuits. They hosted poetry clubs in their gardens to develop cultural networks and liaisons with literary luminaries. In Traveller’s Garden, Li Chenghong’s poetry club included several well-known poets, such as Hao Ren (1730s?-?), Jin Quan (1730s?-1810s?), Wu Nianhu (1740s?-?) and Feng Kunshan (1740s-?); and he even hosted Kang Yaoqu (1741–1802), a famous poet of High Qing (L. Gao, Citation1931, p. 1053). Beyond his identity as a merchant, Li was elected as the leader of the poetry club. Also, the Zha family organised the Plum-Blossom Poetry Club (Meihua shishe) in their Manor West of the River. This important club was praised as being ‘the peak of high society in Tianjin’ (L. Gao, Citation1931, p. 1053). Apart from poetry, the Zha family stepped into the intellectual sphere by making financial contribution historical monographs and local chronicles. Thereupon, Manor West of the River became the birthplace of Tianjin County Annals (Tianjin Xianzhi) and Tianjin Prefecture Annals (Tianjin Fuzhi) (Lu, Citation1997, p. 13).

Salt merchants of the high Qing Dynasty used their gardens both to display their power and wealth and to earn social capital. Through their gardens, they expended huge resources to elevate their social standing and then profited materially and in terms of social capital from this.

Extravagant enclosure: late Qing Dynasty (1840-1911)

Although the salt merchants had accumulated huge wealth and exclusive privileges, large compulsory donations to the emperor and growing charges and fees began to overwhelm them (Ding & Tang, Citation1986, p. 21). The salt merchants raised salt prices to protect their interests, but this encouraged salt smuggling which ultimately severely damaged the foundation of their business (P. Gao, Citation2012, p. 87).

With the outbreak of the Taiping RebellionFootnote5 and China’s increasing involvement in world affairs as a consequence of the first Opium War (1840–1842), the established social structure began to collapse in the second half of the nineteenth century. Consequently, selling offices and titles became common, and salt merchants no longer needed to accumulate social resources to change their social identity. Also, folk entertainment, such as clapper-accompanied opera (bangzi), current tunes (shidiao) and storytelling, emerged and quickly became popular in Tianjin, displacing literati activities (Luo, Citation1993, p. 109).

The salt merchants paid less attention to their gardens, and designed landscapes once renowned in the early and high Qing Dynasty were neglected and fell into disrepair. The formerly glorious Manor West of the River ‘only had some ordinary gardens left after the Tongzhi period (1856–1875), with a view of ‘dilapidated [fields] where monks grew vegetables’ (L. Gao, Citation1922, p. 712). The Ferry Garden ‘lay desolate’ (Jiang, Citation1879, p. 92). Even relatively recently built gardens were downscaled in size to reduce financial outlay.

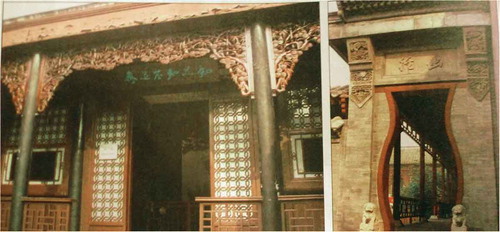

Rather than maintain the gardens exclusively as scenic landscapes, the salt merchants began to build their own dwellings on these sites. Hence, the salt merchants spent their daily lives within the enclosures—their gardens. This included developing part of the compounds to serve as leisure spaces. For example, Huang’s Compound had five large quadrangle dwellings, with the garden located at the western corner of the west yard (Guo et al., Citation2008, pp. 138–139). Shi’s Compound was honoured as ‘the first dwelling of Tianjin’. The garden was situated at the southeast corner of the yard, covering less than one sixth of the more than 7,000 m2.

During the late nineteenth century, a great number of luxurious imperial gardens were built in Beijing. Beijing’s proximity to Tianjin naturally meant that the extravagant style of these gardens would influence the salt merchants to develop showy constructions in their own compounds. In Li Chuncheng’s Rong Garden, the library had ‘carved beams and painted rafters, and vermilion gates and windows, with a spectacular scene (Lai & Zhang, Citation2004, p. 205). Likewise, in Huang’s Compound, not only were all the buildings engraved with delicate decorations, the tiles on the eaves and floss holes were gaily decorated in the basket style, Aquarius style, or with flower and bird tile carvings (Guo et al., Citation2008, p. 139). To create an air of luxury, the salt merchants obtained expensive materials, using rare stone and wood to develop landscapes regardless of cost. For example, in Shi’s Compound, large blue, fine stone was used for all stone features and all timber features used hardwoods, such as Nanmu, Catalpa, and Cypress from Yunan, Guizhou, and other provinces in northwest China. []. Even bricks and tiles were from Suzhou of Jiangsu province and Linqing of Shandong province, several hundred kilometres from Tianjin (Guo et al., Citation2008, p. 161).

Figure 4. Delicate wooden and brick decorations of Shi’s Compound. Tianjin Historical Famous Gardens (2008), Tianjin.

In contrast to the extravagance in architectural construction, the exotic flora in the gardens disappeared in favour of indigenous plants. Even the Rong Garden featured common, local plants such as reeds, peach, willow and pine trees, although it was praised as ‘a sprightly and fresh place making people feel invigorated and content’ (Qing, Citation1986, p. 204; Song, Citation1930, p. 114). Similarly, the plants of Shi’s Compound were made up of local jujube trees and shrubs. As a consequence, the gardens lost their scholarly refinement, becoming commonplace.

The constructions in the compounds, including the salt merchants’ dwellings and the entertainment spaces, made these gardens extravagant enclosures. Literary activities and grand garden parties declined, and the salt merchants only hosted small meetings on certain dates, such as ‘special holidays in the spring or autumn’, or the ‘the early summer when Chinese herbaceous peony bloomed’ (L. Gao, Citation1922, p. 738). However, the guests were always just two or three close friends (L. Gao, Citation1922, p. 738). And the poetry clubs and publications even faded out of view.

Witnessing this situation, the elites of Tianjin expressed their regret, as Gao Lingwen noted:

Once the ancients had a garden they would invite and accommodate well-regarded or influential people inside and undertake artistic activities to entertain the people. By contrast, those who have gardens now just enjoy themselves inside, serving themselves, rather than inviting other people. However, they do not realise that in serving other people, they ultimately serve themselves (L. Gao, Citation1922, p. 738)

Despite this, by the late Qing Dynasty, the salt merchant gardens became enclosures both in the sense of walled compounds and in the sense of isolated private spaces.

Conclusion

During the Qing Dynasty, in the struggle to deal with tensions between changing state policy and social order and culture, the salt merchants of Tianjin rose to a zenith and then declined in their social identity, living conditions and personal fortunes. The merchants’ designed landscapes both influenced and reflected this rise and decline. Consequently, the physical landscapes of the salt merchant gardens evolved from idyllic scenery, to delicate artificial landscapes, and finally to extravagant structures. The roles these gardens played in the lives of merchants transited from literary self-immersed space, to a stage on which to present and earn power, and finally to a corner for private entertainment. The salt merchant gardens in Qing Tianjin evolved from the arcadia of the literati to a showcase of power to an extravagant enclosure.

With the collapse of the Qing Dynasty, some salt merchants planned to reconstruct the Manor West of the River to revive the glorious salt merchant gardens of the high Qing. Although they began preparations, the leading merchant passed away before the construction commenced (L. Gao, Citation1922, p. 738). Thereafter, the proposal, together with the salt merchant gardens in Tianjin, became a part of history.

Acknowledgement

I would like to express my deep gratitude to Prof Elaine Jeffreys, Mr Zhu Yayun, Mr Laurence Stevens, and anonymous referees for providing valuable comments on the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Yichi Zhang

Dr Yichi Zhang is a postdoctoral fellow at the Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages, University of Oslo. Trained as a landscape architect, conservator and garden historian, he was a Postdoctoral Fellow (2019) at the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art (Yale University) and research fellow (2015) in Garden and Landscape Studies at Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University. He is recipient of both the 13th Annual Mavis Batey Essay Prize, 2017 (the Garden Trust, the UK) and the Annual Awards for Post-Doctoral Scholars, 2017 (Geographical Society of New South Wales, Australia).

Notes

1. The three renowned private gardens are Manor West of the River in Tianjin, Small Exquisite Mountain House (Xiaolinglong Shanguan) in Yangzhou and Small Mountain Hall (Xiaoshan Tang) in Hangzhou.

2. Pleasant Place of Jade Mountain (Yushan Jiachu) is the garden of Gu Ying (1310–1369), a litterateur and bibliophile of the late Yuan Dynasty, which is in Hangzhou and renowned for its collection of antiques.

3. Lin Bu was a Chinese poet during the Northern Song Dynasty. He refused civic duties and lived as a recluse by the West Lake in Hangzhou for much of his life.

4. Ding and Yi are prehistoric Chinese bronze cauldrons and wine vessels used for ritual purposes.

5. The Taiping Rebellion was a massive social upheaval from 1850 to 1864, which promoted the dissolution of the established social structure in China.

References

- Adshead, S. A. M. (1992). Salt and civilization. Canterbury University Press.

- Chen, Y., (陈元龙). (1733). Story of Manor West of the River (水西庄记). In X. Lai (来新夏) & F. Guo (郭凤岐) (Eds.), General Annals of Tianjin- Old Local Chronicles Punctuation and Collation (天津通志 旧志点校卷) (Vol. 2, pp. 78). Nankai University Press.

- Clunas, C. (1996). Fruitful sites: Garden culture in Ming Dynasty China. Reaktion Books.

- Ding, C., (丁长青), & Tang, R., (唐仁粤). (1986). History of the Chinese salt industry (中国盐业史). People Press.

- Finnane, A. (2004). Speaking of Yangzhou: A Chinese City, 1550–1850. Harvard University Asia Center.

- Gao, L., (高凌雯). (1922). Sketches after annals (志余随笔). In X. Lai (来新夏) & F. Guo (郭凤岐) (Eds.), General Annals of Tianjin- Old Local Chronicles Punctuation and Collation (天津通志 旧志点校卷) (Vol. 3, pp. 689–739). Nankai University Press.

- Gao, L., (高凌雯). (1931). New annals of Tianjin County (天津县新志). In X. Lai (来新夏) & F. Guo (郭凤岐) (Eds.), General Annals of Tianjin- Old Local Chronicles Punctuation and Collation (天津通志 旧志点校卷) (Vol. 2, pp. 497–1066). Nankai University Press.

- Gao, P., (高鹏). (2012). An analysis on the decline of Changlu salt merchants during the period of Qianlong and Jiaqing in Qing Dynasty (乾, 嘉时期长芦盐商群体衰落现象分析). Salt Industry History Research, 3, 87–94.

- Guo, X., (郭喜东), Zhang, T., (张彤), & Zhang, Y., (张岩). (2008). Famous historical gardens of Tianjin (天津历史文化名园). Tianjin Classics Publishing House.

- Han, C. (2012). The aesthetics of wandering in the Chinese literati garden. Studies in the History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes, 32(4), 297–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2012.721995

- Hrdličková, V. (2009). The culture of Yangzhou residential gardens. In L. Olivová & V. Børdahl (Eds.), Lifestyle and Entertainment in Yangzhou (pp. 75–86). NIAS Press.

- Hua, D., (华鼎元). (1879). The poems on the historic sites of Tianjin (津门征跡诗). In D. Hua (华鼎元) (Ed.), Zililianzhu Collection (梓里联珠集) (pp. 165–190). Tianjin Classics Publishing House.

- Hua, D., (华鼎元). (1886). The biography of Mei Chengdong and Kang Dafu (梅成栋康达夫小传). In D. Hua (华鼎元) (Ed.), The Poems of Tianjin (津门征献诗) (Vol. 7, pp. 7). Xiewenhanzhai.

- Jiang, S., (蒋诗). (1879). The poems on the rivers of Tianjin (沽河杂咏). In D. Hua (华鼎元) (Ed.), Zililianzhu Collection (梓里联珠集) (pp. 65–99). Tianjin Classics Publishing House.

- Keswick, M., & Jencks, C. (1978). The Chinese garden: History, art & architecture. Rizzoli.

- Kwan, M. B. (2001). The salt merchants of Tianjin: State-making and civil society in late Imperial China. University of Hawai’i Press.

- Lai, X., (来新夏), & Zhang, Y., (章用秀). (2004). The historic gardens of Tianjin (天津的园林古迹). Tianjin Classics Publishing House.

- Liu, H., (刘海岩). (1995). A dialogue about the culture of modern Tianjin and its uniqueness (关于近代天津文化及其特质的对话). In Institute of Historical Research of Tianjin Academy of Social Sciences (Ed.), Urban history research (Vol. 10, pp. 71–82). Tianjin Classics Publishing House.

- Long, Z., (龙震). (1824). Stay at home idle in the summer (夏日闲居). In C. Mei (梅成栋) (Ed.), The Poem Collection of Tianjin (津门诗钞) (pp. 34). Tianjin Classics Publishing House.

- Long, Z., (龙震). (1886). The memory of my friendship with Zhang Fanshi (记亡友张帆史交情始末). In D. Hua (华鼎元) (Ed.), The Poems of Tianjin (津门征献诗) (Vol. 8, pp. 21). Xiewenhanzhai.

- Lu, H., (路蘅). (1997). A review on Manor West of the River (回首沧桑话水西). Tianjin Culture and History (Special issue on the research of Manor West of the River) (天津文史 (水西庄研究专辑)), 2, 13–14.

- Luo, S., (罗澍伟). (1993). Modern Tianjin Urban History (近代天津城市史). China Social Sciences.

- Meng, Q., (孟庆斌). (1992). A short history on the salt of Changlu (长芦盐业史述略). Hebei Academic Journal, 4, 98–103.

- Meyer-Fong, T. (2003). Building culture in early Qing Yangzhou. Stanford University Press.

- Puk, W. (2016). The rise and fall of a public debt market in 16th-century China: The story of the Ming salt certificate. Brill.

- Qing, R., (荣庆). (1986). Rong Qing diary (荣庆日记). Northwest University Press.

- Richard, J. (2015). Uncovering the garden of the richest man on earth in nineteenth-century Canton: Howqua’s Garden in Honam, China. Garden History, 43(2), 168–181. Retrieved from www.jstor.org/stable/24636248

- Song, Y., (宋蕴璞). (1930). Concise annals of Tianjin (天津志略). In X. Lai (来新夏) & F. Guo (郭凤岐) (Eds.), General Annals of Tianjin- Old Local Chronicles Punctuation and Collation (天津通志 旧志点校卷) (Vol. 3, pp. 91–410). Nankai University Press.

- Wang, H., (汪沆). (1739). The poems on the chores of Tianjin (津门杂事诗). In D. Hua (华鼎元) (Ed.), Zililianzhu Collection (梓里联珠集) (pp. 3–62). Tianjin Classics Publishing House.

- Wen, Z., (文震亨), & Chen, Z., (陈植). (1984). Superfluous Things (长物志校注). Jiangsu Science and Technology Press.

- Wu, H., (吴惠元). (1870). Sequel to Annals of Tianjin County (续天津县志). In X. Lai (来新夏) & F. Guo (郭凤岐) (Eds.), General Annals of Tianjin- Old Local Chronicles Punctuation and Collation (天津通志 旧志点校卷) (Vol. 2, pp. 259–496). Nankai University Press.

- Wu, W., (吴雯). (1774). A letter to Yifeng, the scholar (柬逸峰孝廉). In W. Wu (吴雯) & T. Zhang (张体乾) (Eds.), Lianyang Collection (莲洋集) (Vol. 13, pp. 4). Jinpu Caotang.

- Xia, X., (夏咸淳). (1993). The relationship between literati and merchants in the late Ming Dynasty (明代后期文士与商人的关系). Social Science, 3, 59–63.

- Xu, Y., (徐永志). (1998). The governments of Ming and Qing Dynasty and the social economic transformation of Tianjin (明清政府与天津社会经济变迁). The Journal of Chinese Social and Economic History, 4, 36–40.

- Yan, X. (2015). In search of power and credibility: essays on Chinese monetary history (1851–1945). PhD thesis, The London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Zha, W., (查为仁). (1743). The collection of baoweng (抱瓮集). In W. Zha (查为仁) (Ed.), The Draft of Zhetang (蔗塘未定稿) (Vol. 2, pp. 1–20).

- Zhang, S., (张霔). (1824a). Gathering at the melon cottage, with Lu Shiqi Chen Zihui, Li Shengke and Zha Hanke (瓜棚秋集, 同陆石骐, 陈子翙, 李省可, 查汉客). In C. Mei (梅成栋) (Ed.), The poem collection of Tianjin (津门诗钞) (pp. 164). Tianjin Classics Publishing House.

- Zhang, S., (张霔). (1824b). Humble Cottage Poem (草堂诗). In C. Mei (梅成栋) (Ed.), The poem collection of Tianjin (津门诗钞) (pp. 22). Tianjin Classics Publishing House.

- Zhang, S., (张霔). (1991). Replanting Willows in the Leisure Hall Garden (遂闲堂别墅移柳记). In G. Hua (华光鼐) (Ed.), A collection of Tianjin Archives (天津文钞) (Vol. 5, pp. 4–5). China Bookstore press.

- Zhang, T., (张焘). (1884). Notes of Tianjin (津门杂记). Youyishanzhuang.

- Zhao, E., (赵尔巽). (1976). Draft History of Qing (清史稿). Zhonghua Book Company.