Abstract

This paper takes an historical perspective to examine the social and community motivations for public parks and their funding. Public parks can be some of the most valuable green infrastructure assets; understanding why they were created and how they have developed can usefully inform current international practice. Analysis is of one the UK’s first public parks, Peel Park, Salford, Greater Manchester and draws on documentary material from the Park’s creation in the 1840s and its refurbishment in the 2010s. Common and long-lived expectations for community cohesion are found, but for contemporary management we highlight the importance of park quality and understanding public parks as part of wider equality issues. We also argue that entrepreneurial municipalism and diversified funding arrangements introduce diverse politics and interests to park provision. A lack of government funding, and thus a reliance on charitable and philanthropic sources, also potentially categorise public park provision as non-essential.

Introduction

Green infrastructure (GI) as a concept has garnered a broad coalition of interests and literature paints an increasingly complex picture of the benefits, functions and (ecosystem) services expected (Benedict & McMahon, Citation2006; European Union, Citation2013; Sinnett et al., Citation2015). Arriving at a singular definition is therefore neither feasible nor desirable. As Wright (Citation2011) argued, GI is better understood as a contested concept, shaped by various forces. As some of the most established GI features, public parks offer an opportunity to gain insight on some the development and contest which has shaped contemporary GI.

Indeed, historical narratives explaining the development of GI, in the UK especially, tend to begin with the development of public parks in response to urbanisation and industrialisation during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. As the nineteenth century developed, public parks came to be favoured over earlier initiatives such as ‘public walks’,Footnote1 for three primary reasons. First, they provided a means of addressing contemporaneous miasmatic theories of disease by ensuring the provision of ‘large sanitary “lungs” to stem the progress of epidemics’ (Reid, Citation2000, p. 763). Secondly, they provided a means by which to ‘civilise’ and ‘improve’ the working-class, for example, through so called ‘rational recreation’Footnote2 (O’Reilly, Citation2013). Thirdly, various speculative development schemes had started to use parks to improve the value of the houses being developed (Layton-Jones & Lee, Citation2008; Sharples, Citation2018).

Taking these ideas as our starting point, this paper addresses the research question, how have public parks developed and been shaped over time? We utilise an historical perspective to specifically examine:

the social and community motivations for public parks; and

the funding of public park creation and refurbishment.

We begin with a discussion of literature, followed by an explanation of our methods. We then present our analysis in two sections before drawing together our discussion and conclusions.

Public parks and green infrastructure

As Britain’s industrial development intensified, public parks were increasingly developed in a growing number of cities. As Taylor (Citation1995) noted, this was a process that started with the opening-up of the Royal Parks in London. From these grand former hunting grounds, the next generation of public parks followed from the mid-nineteenth century. When the Select Committee on Public Walks reported in 1833, they raised concerns of overcrowding, poverty, squalor, ill-health, lack of morals and morale (Taylor, Citation1995), and called for the creation of public parks. Action to counter such urban ills by opening public parks began with the opening of Derby Arboretum in 1840. Peel Park, Salford followed in 1846 along with Queen’s and Philips Parks in neighbouring Manchester. Though common land and greenspaces had existed previously, what made these developments novel was that they were deliberately planned as places for public recreation (Layton-Jones & Lee, Citation2008).

Rational recreation was not, however, to be idle but improving. Facilities recorded for public parks included outdoor gymnasia, cricket, archery and bandstands for the provision of afternoon concerts, ‘healthy’, wholesome and improving activities taking centre stage; described as ‘instruments of physical health and social discipline’ (Beckett, Citation2005, p. 403). Literature on contemporary GI connects to some of the same health and social aspirations, and a substantial body of evidence has been built up for the health and salutogenic value of GI, particularly parks, for individuals and communities (Coutts, Citation2016; Silveirinha de Oliveira & Ward Thompson, Citation2015).

In many settings parks are some of the most visible ‘hubs’ within GI networks and important community assets (Benedict & McMahon, Citation2002, Citation2006). Barker et al. (Citation2019) argue that parks can aid community cohesion, not through deliberate community acts necessarily but by offering convivial spaces where diversity is observed and rendered mundane; helping to form loose community bonds. However, it is also important to acknowledge that parks can ‘ … be delightful features of city districts, and economic assets to their surroundings as well, but pitifully few are’ (Jacobs, Citation1961, p. 99).

Moreover, community cohesion as a policy agenda should not be looked on uncritically. As Cowden and Singh (Citation2017) argue, community cohesion can serve to impose a singular set of values and emphasise identity differences. For diverse communities to be successful, they argue, it is important to attend to the material realities of poverty. Unequal access and variable quality of local parks is part of this material reality of poverty and is tied to socio-economic status and ethnicity (Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment, Citation2010; Office for National Statistics, Citation2020). We argue therefore, that the connection between parks and local communities present in the nineteenth century remains pertinent to contemporary debates.

To consider the financing of parks, we note clear connections to class politics from their inception, and that the establishment of parks was not a wholly altruistic act. The connection between parks and land value was well established; parks or gardens, more often private or by subscription, were frequently part of the economics of speculative housing development (Layton-Jones & Lee, Citation2008; Sharples, Citation2018). Public parks, however, were primarily financed in the mid-nineteenth century by a combination of philanthropy and public subscription, the prevailing ratepayers’ laissez-faire attitudes still being wedded to notions of self-improvement, anti-municipalism and the idea that ‘funding the leisure or improvement of the poor was not their business’ (Doyle, Citation2000, p. 292). Rather, as Taylor noted, part of the political motivation of the upper and middle classes’ arguing for public spaces was that they provided an antidote to the squalid conditions of the industrial towns, thereby ensuring their continued positions of leadership whilst simultaneously contributing to the ‘improvement’ of the working class. As Beckett argues, ‘regulated amusement was regarded as a safety valve for social diffusion … rational recreationalists looked to extend middle-class leisure interests to the working classes’ (Beckett, Citation2005, p. 403). The provision of parks as a way of appeasing the working classes to maintain political power was not a uniquely British phenomenon, indeed New York City in the 1880s had a similar fusion of park provision and political power (Rosenzweig & Blackmar, Citation1992). Viewed in this way, therefore, the establishment of public parks was in the political interest of the upper and middle classes, as well as a boon to municipal health and part of the broader continuum of mid-nineteenth century working class self-improvement initiatives (Reid, Citation2000).

The connection between GI more generally and economic returns remains part of the contemporary context (Mell et al., Citation2013). However, to further understand this we need to consider the shift of municipalities from ‘growth machines’ towards an idea of the entrepreneurial city, navigating deindustrialisation, neoliberal markets and inter-urban competition (Lauermann, Citation2018). Alongside arguments that local governments have fully incorporated neoliberalism (Keil, Citation2009), we need to understand contemporary municipal interventions as more broadly constituted than always growth focused, potentially incorporating parallel and conflicting politics. The entrepreneurial municipality may adopt diversified intervention portfolios, experiment with success metrics other than economic growth, and undertake diplomacy to achieve objectives (Lauermann, Citation2018). However, municipal entrepreneurialism should not be assumed to bring more progressive politics, rather a diverse and disrupted politics with potential for conflict and informed by the histories and geographies of an area (Lauermann, Citation2018).

With an entrepreneurial mode in mind, set against a backdrop of austerity and public sector cuts which have dramatically impacted on local authority budgets and their commitments to GI (Gray & Barford, Citation2018; Mell, Citation2020), it is also important to consider the influence and role of funding from beyond the public sector. The involvement of non-profits and philanthropic organisations within the funding of public parks has the potential to bring in additional sources of funding but may bring unintended consequences. Brecher and Wise (Citation2008) argued that the inclusion of funding from non-profits can introduce particularistic rather than public interests into decision making, whereby funding directs action to the particular, although often laudable, goals of the non-profit which may not cover the full range of public benefits provided or communities served. Similarly, charity funding may introduce additional complexities as the geography of collection may not align with geography of action. And while in some cases this redistributive effect may be exactly the aspiration, charitable collections for example, via lotteries have been found to disproportionately collect from less-well off areas while providing no guarantees that those same areas will benefit (Pickernell et al., Citation2004).

This review of public parks and GI literature, rather than providing a definitive history of either, locates the two literatures alongside one another. The literature reinforces the focus of our research on the politics driving park creation, community and social functions, and park funding.

Methods

This research analyses Peel Park, Salford, Greater Manchester, UK. The case study approach enables a detailed and context rich understanding of a real-world example (Flyvbjerg, Citation2006; Yin, Citation2012). Peel Park was selected because it is one of the earliest public parks established in the UK (opened in 1846) and thus reflects the very early aspirations held. Peel Park also provides the opportunity to examine how aspirations and funding for public parks have changed as it was significantly renovated (reopening in 2017) in recent years due to its degradation. Peel Park has remained public throughout its 170-year history, but rather than attempting to cover this long history, we focus on two specific points in time—the years leading up to its creation in 1846 and the years approaching its refurbishment in 2017. This provides a view of how the politics, debates and funding of public parks may have changed. We use documentary evidence from local archives, including council and committee minutes and newspaper records.

The creation of Peel Park

On Saturday 22 August 1846, Peel Park was, at 32 acres (approximately 13 hectares), the largest of three parks opened within the adjoining Boroughs of Salford and Manchester. There was much civic celebration. A cavalcade of two charabancs along with an assorted menagerie of 35 horse drawn and motorised carriages and coaches processed from Manchester Town Hall accompanied by two regimental bands to Salford Town Hall. There met by additional coaches containing Salford’s civic elite, the combined party of solely male dignitaries made their way, flanked by policemen and members of Salford Borough’s fire brigade, to the entrance of Peel Park. The opening ceremony performed, the cortege duly proceeded to the second and third opening ceremonies of the day at Queen’s and Philips Parks (within the Borough of Manchester). Thereafter, and having dined at a civic lunch which, due to the number of people who had attended the ceremonies and thronged the streets, began a mere two hours behind schedule, a ‘great meeting [of 5,000] in the Free Trade Hall’ took place until a late hour (Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser (MCLGA), Citation1846). The importance attached at a civic level to the day’s events is underlined by the scale of the festivities, the number of non-local worthies in attendance, and the unprecedented coverage—for that time—given to them by the MCLGA. And yet, despite this sustained trumpeting of civic prowess and progressiveness, neither Manchester nor Salford Corporation had contributed financially towards establishing the three parks. Rather, their creation was financially realised through 5,000 individual public subscriptions and a small grant from a central government fund. It was a process that, as this paper notes, worked wholly outside of the established structures of existent local governance.

Following the depositing of a number of letters and petitions to Manchester Town Council between June 1843 and May 1844, the Mayor, Alexander Kay, decided to convene on 8 August 1844 a ‘public meeting of the gentry, bankers, merchants and traders of Manchester, to consider the propriety of taking steps for the formation of a public park, walk or playground’ (MCLGA, Citation1844a). Those who duly assembled were informed that two pledges of £1,000 each had been received from Sir Benjamin Heywood and Mark Philips MP,Footnote3 and a series of letters were read out from various notables unable to attend in person. Common to each was the belief that the provision of park facilities would be of primary benefit to the working classes. It was, as the Reverend Canon CD Wray wrote, ‘desirable that the working-classes should have spaces of ground found for them, where they may be able to take moderate exercise, and find relaxation from their daily toil’ (MCLGA, Citation1844a). This theme was readily endorsed by those in attendance; by the meeting’s close a total of £7,000 had been pledged (predominantly in denominations of £500 of £1,000), and a series of related resolutions unanimously agreed. These included: that Manchester needed at least two parks, that a Public Park Committee (PPC) of 25 named individuals should be appointed to oversee the raising of the funds necessary to purchase suitable land, and that once laid, such sites would be ‘conveyed over to the Mayor, Alderman and Burgess of the Borough and their successors’ on the understanding that they would be ‘for the free use and enjoyment of the inhabitants in perpetuity [… and kept in] good order and repair’ (MCLGA, Citation1844a).

Though those who spearheaded this civic movement were empowered and entitled citizens who, predominantly, were also intimately linked to differing aspects of the town’s governance, the process of establishing the public parks operated outside of such formal institutional structures. This reflected the dominant laissez-faire ideology of mid-nineteenth-century classical liberalism and the ideals of minimal state intervention whilst also adhering to the still ascendant doctrine of self-help and improvement. Accordingly, though led by the upper classes and frequently presented as an almost paternalistic endeavour, ‘not a gift to the town but a righting of a wrong, a deficiency, for the labourers of the working-class’, it was not an altruistic movement (Rt Hon. Lord Francis Egerton MP,Footnote4 as cited in MCLGA, Citation1844a). Rather, it was co-operative, with the direct financial input and ‘buy-in’ of the workers themselves being not only essential to the fundraising campaign but also the parks’ subsequent usage. The need to galvanise working-class support and the framing employed so to do, is readily evident in both the public call for the ‘working class meeting’ held on 10 September 1844 to specifically launch the scheme to the working class and the Chairman’s opening remarks at the same. The former implored:

every woman who finds her children’s sport restricted by the smallness of her house, and their health deteriorated by continual habitation of crowded streets, and who loves her offspring and wishes them to live, should move herself, and induce her husband to move, in support of the establishment of free public parks … [for they will] excite mind to action, by supplying instructive and pleasing lessons in science; will moralize by the association of class and the generation of sympathy between them … (MCLGA, Citation1844b).

Delivering the latter, Abel HeywoodFootnote5 proclaimed that, ‘a greater desire on the part of the upper classes to assist in the progress of the working men had never existed in this country … [but] the object could only be carried out by the co-operation of the working-classes themselves’ (cited MCLGA, Citation1844b).

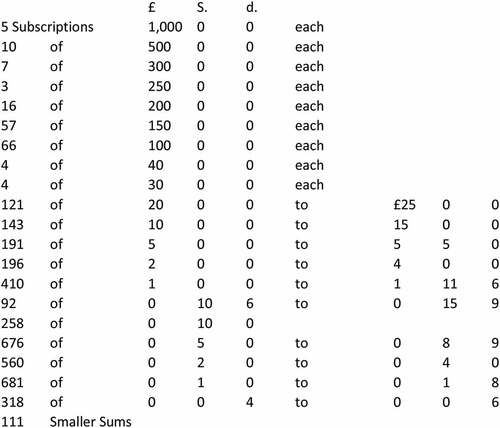

The approach worked. Not only did approximately 5,000 persons attend the meeting in Manchester’s Free Trade Hall,Footnote6 but by 21 September 1844, some £19,112 13s had been raised. Indeed, such was the scale of the contributions received within the appeal’s first six months that the PPC actively began to seek to purchase sites from January 1845 onwards. The first land purchased was that of the former Lark Hill Estate, Salford. Comprised of some 7 acres this purchase was quickly followed by 25 acres from the adjacent Wallness Estate at a combined total cost of £9,981 10s. Exactly a year from the initial public meeting, the public subscription fund was formally closed. It had raised in excess of £32,167 10s with individual sums given ranging from five subscriptions of £1,000 each to 329 donations of 4d or under (MCLGA, Citation1846—and ).

Figure 1. Records of donations received to the PPC fund (Source: Adapter from MCLGA, Citation1846)

Sites secured, the PPC’s attention shifted to the facilities to be provided and their future management. Concurrent to its formal closing of the public subscription fund, the PPC informed Manchester Corporation that it had resolved, in keeping with the resolution passed at the initial public meeting of August 1844 to transfer ownership of all its properties to the Corporation provided they hold them in trust in accordance with the resolutions of the August 1844 public meeting (Manchester Town Council, Citation1845, p. 181). The Corporation concurred and it was agreed that upon their opening the three parks would be transferred to the Corporation. This was subsequently amended to Salford Borough Council in the case of Peel Park with the same provisions of trust.

Realising the PPC’s commitment to provide activities focused upon the physical needs of the working classes, Peel Park was subsequently endowed with playgrounds, a large area of flat land that would be ideal for ‘cricket …, and other manly games and healthy exercise’ (Manchester Guardian, Citation1846a) and an outdoor gymnasium (see ). The latter being likely, in the opinion of the Manchester Guardian (Citation1846b) to be a ‘favoured facility amongst working class boys and young men’ on account of its being furnished with; horizontal beams, climbing ladders, a climbing board, slanting and parallel poles, a vaulting horse, a set of German ropes, separate adult and child parallel bars and a set of flying steps. Regrettably, however, though the sites for each had been agreed and laid out, at the time of the park’s opening the PPC was unable, ‘from want of funds … to provide any implements for ball-play, cricket, fives, skittles, [and] archery’.Footnote7 All requests from the PPC for minor financial assistance from the corporation having been rebuffed on the basis that the council could not ‘grant any money whatever for the purposes of the parks until they had possession of the whole’ (MCLGA, Citation1846).

Figure 2. Plan of Peel Park (Source: Ordnance Survey, Citation1850. Courtesy of Salford Local History Library)

The parks were not to be solely, however, places of physical recreation for ‘the working classes for whose especial use [they] had been established’ (Salford Borough Council, Citation1848, p. 68). They were also established as spaces for self-improvement. Accordingly, it was hoped that weekly concerts and the labelling of all different species of trees and plants would, ‘awaken attention and give information to many of the humbler classes’ (Manchester Guardian, Citation1846c). Whilst the provision of a wide carriageway encompassing the entire site, boats for hire upon the River Irwell—along with the promise of future Regattas—and a series of tiered parterres, would not only further elevate the ‘tastes, morals and intellect of the labouring classes’ (Manchester Guardian, Citation1846a) but also make the park an attractive place for members of all classes. It was to be a ‘democratic space’ in which all peoples could ‘meet on a footing of perfect equality’ (Philips as cited in MCLGA, Citation1846). Though whether the subsequent provision of ‘two classes of refreshment rooms’ with tiered prices reflecting patrons’ class (Manchester Guardian, Citation1846c) was a measure designed to enable cross-class subsidisation or enshrine social-segregation remains a moot point.

What is clearer is Peel Park’s immediate popularity. Reporting on its census of park usage for the week ending 30 July 1847 Salford Borough Council’s Park’s Committee Annual Report noted that a total of 30,069 had visited the park during that week. These figures, for ‘an average week of the season’ (Salford Borough Council, Citation1847, p. 60), clearly suggest that Peel Park had indeed become, in the words of Robert Sanley MPFootnote8 and Mark Philips MP in their respective addresses to the crowds gathered at its official opening, a place where the ‘labouring classes, when their day’s labour is done, may … walk with their wives and children, enjoying the sweet converse of those who are dearest to them’; ‘the people’s park, raised by the people, and for the use of the people’ (MCLGA, Citation1846).

The refurbishment of Peel Park

Much like in 1846, the re-opening of Peel Park was marked with a public event. The auspicious evening of Friday 13 October 2017 saw the park transformed into ‘The Fire Garden’ with fire displays and lanterns (@PeelParkSalford, Citation2017; Roue, Citation2017). An ‘official’ opening was also held in May 2018; a more formal affair with a small group reviewing the completed works and the reinstatement of the Joseph Brotherton statue (@PeelParkSalford, Citation2018; Keeling, Citation2018). Social media posts show some reverberations from these events and the @PeelParkSalford Facebook and Twitter pages offer posts and photographs recording the scenes (@PeelParkSalford, Citation2017, Citation2018). Unlike in 1846, news coverage of the re-opening is scant, perhaps reflecting how commonplace public parks have become or decline of civic pride (Collins, Citation2016; Reeves, Citation2000). Nevertheless, some reporters did offer tangential coverage as part of other news (Keeling, Citation2018; Lovell, Citation2017; Roue, Citation2017).

Returning to the founding principles for the establishment of Peel Park, we are reminded that the park was to be ‘for the free use and enjoyment of the inhabitants in perpetuity [… and kept in] good order and repair’ (MCLGA, Citation1844a). Peel Park is still owned and managed by Salford City Council and is free to use. However, the park has experienced considerable change since its creation. Most striking are its reduction in size and changes to its general setting, in particular its reduced visibility from the street and the loss of parts of its elevated views of the River Irwell (Burnett, Citation2014; Luczak Associates, Citation2015). The size of the park has fluctuated over time, gaining space to the north and losing space to the south (Burnett, Citation2014). Today the park is approximately 10 hectares and sits alongside several other greenspaces, together making up one of the largest public open spaces in Salford (Luczak Associates, Citation2015) (see ).

Figure 3. Master Plan showing improvements proposed to Peel Park as part of the refurbishment (Source: Urban Vision, Citation2015)

Much of the space, visibility and views lost from the park were related to the establishment of the Royal Technical Institute, which was built in 1896, and the 1950s and 1960s expansion of the University of Salford. As Burnett noted,

‘The expansion of the University curtailed the entire environs of the museum building and almost broke its link with the park. The Park itself lost many of its features due to deterioration, new design, lack of resources and vandalism’ (Burnett, Citation2014, p. 42).

For some these changes led locals to report that the park was ‘out of sight, out for mind’ (Luczak Associates, Citation2015, p. 12). Historic features such as the statues of Joseph Brotherton MP and Sir Robert Peel, the Prime Minister after whom the park is named, were removed in 1954 (Burnett, Citation2014). Although the site has remained accessible to the public, development in the area has dramatically changed its southern section and the ability of Salford City Council to maintain the facilities in ‘good order and repair’ has not always been possible over park’s life and the heritage value of the park was considered to be at risk by the early 2010s—hence the need for refurbishment (Salford City Council & Urban Vision, Citation2013).

It is within this context that the latest refurbishment of Peel Park took place. Refurbished between 2015–2017 and funded by a Heritage Lotter Fund (HLF) Parks for People grant approved in June 2015, Peel Park has been restored largely to its 1890 layout (Greenspace Management and Development, Citation2017; Salford City Council, Citation2015a). The vision developed for the HLF application and maintained through the various Landscape Management Plans is:

To create an attractive, well-used park for 21st century living, providing a place for enjoyment, inspiration, reflection and a source of local pride (Greenspace Management and Development, Citation2016, p. 11, Citation2017, p. 11; Luczak Associates, Citation2015, p. 19).

The vision statement goes on to emphasise desires to reintroduce historic features and to ‘re-establish the links between recreation and learning through a programme of activities and links with Salford Museum and Art Gallery’ ultimately calling to ‘put the public emphasis back and make this once again “A Park for the People”’ (Greenspace Management and Development, Citation2016, p. 11).

This connects us to one of the key themes of the refurbishment of the park, its emphasis on connecting with the public. As part of the proposed Management and Maintenance Plan we see identification of current and potential audiences. Moving on from the blunt focus on the ‘labouring’ classes, contemporary audiences are identified largely as the local population, some 27,128 people within 1.2 km of the park and predicted to grow considerably by 2028 (Luczak Associates, Citation2015). The demographics of this population are also understood in greater detail, albeit with a similar focus on ideas of need and poverty as in the nineteenth century. Locally, it is observed that there is a greater proportion of younger residents, a greater number of dependent children, a significant retired population and greater ethnic diversity than the rest of the Borough, as well as higher residential density and less land given for domestic gardens (Luczak Associates, Citation2015). Health and deprivation indicators are also utilised to outline the context for many people living near the park.

Certain audiences’ current engagement with the park is also noted. Low use by university students, members of black and ethnic minority communities,Footnote9 and disabled groups is reported, against generally good use by local schools through school activities and lesbian, gay, bi-sexual and transgender people associated with a recurrent event hosted in the park—the Pink Picnics (Luczak Associates, Citation2015). The Activity Plan sets out objectives for engagement, including how the refurbishment and subsequent management will enable engagement ‘from all sectors of the community’, identifying families, fitness enthusiasts, retired people, heritage fans, university students, school children, visitors, young people and minority groups as potential audiences (Salford City Council, Citation2015b, p. 36). Surveys collected by the Friends of Peel Park group and a local charity identified concerns over safety; a lack of facilities; poor maintenance; litter; vandalism; poor access for those with disabilities, health conditions or the elderly; and a lack of supervision by a ranger; amongst other issues; ultimately summarised as 71% feeling that Peel Park was ‘not adequate’ (Salford City Council, Citation2015b, p. 14–15).

Since the refurbishment, social media provides a record of some of the events which have taken place, including park clean ups, volunteering sessions, seasonal events, ecological events, tree planting, and themed walks (@PeelParkSalford, Citation2019). shows how some solutions to identified problems and programmed uses were built into the refurbishment plans, for example, the events area, accessible paths, the Park Keeper’s Base (Peel Park Offices), as well as reinstated and restored sculptures and a refurbished play area (Urban Vision, Citation2015).

The detail, data and community consultation surrounding the refurbishment is unlike that of the nineteenth century, nonetheless there are parallels. In the 1840s we saw public meetings, a public subscription fund, and attempts were made to engender class interaction in the park. In contemporary accounts we see similar concerns for community engagement and cohesion: ‘The activity plan seeks to bring these communities [identified audiences] together creating cohesion. Activities will focus on uniting people from all walks of life together to focus on a common interest’ (Salford City Council, Citation2015b, p. 10).

While there is more nuance in the identification and discussion of ‘communities’, in many ways the aspiration that a public park can and should unite communities has demonstrated remarkable endurance.

With respect to the funding of the refurbishment of Peel Park, there are again parallels with the 1840s as funding blended multiple sources. When collecting funds for the establishment of Peel Park, large philanthropic donations, many smaller donations and a national government grant were brought together. The modern refurbishment was funded through a similar fusion. The HLF contributed £1,572,800 from its Parks for People fund; additional funds, bringing the total investment to approximately £2.5 million, were provided by Salford City Council, Salford Community Leisure, Section 106 developer contributions, and the University of Salford (including some non-cash contributions) (Salford City Council, Citation2015a). With civic and public aspirations clearly reaffirmed in the HLF bidding documents and vision statement (Luczak Associates, Citation2015), it is notable that for both the park’s establishment and refurbishment the costs have not been born wholly by the municipality but through a combination of government (national or local), philanthropic and public donations.

Discussion and conclusions

Notions of class interaction and community cohesion feature as motivations in both periods of our analysis. Cowden and Singh (Citation2017) argue that while a cohesive society may be an admirable policy aspiration, focus should also be on the fundamental causes of division, such as poverty and social inequality, rather than solely on adherence to a specified set of norms. For our case, this raises questions about how a public park is being placed within this scenario, as a place to bring people together, but also to represent ‘a common interest’. We do not dispute the ability of parks to act as valuable community assets, the popularity of Peel Park in both 1846 and 2017 demonstrates this potential, but we argue that positioning parks as being able to deliver community cohesion without acknowledgement of the causes of division, risks offering them up as a cover for underlying inequalities (see also Mell, Citation2019). We argue, emphasised by our historical account and the long-held connection between public parks and notions of community mixing, that the existence of a park is not sufficient to achieve or maintain community cohesion; we must be cognisant of park quality and inequalities in access to good quality parks as part of wider societal inequalities.

Creating and maintaining the sort of good quality parks we are advocating requires resources. The practice of blending public and private funding sources to finance parks is found in both accounts, potentially introducing scope for funders to influence park provision or management. In the 2017 refurbishment, we see the majority of funding coming from the HLF—collected through the National Lottery. This continues the historic process of the donations from individual citizens, albeit not directly drawn from the locality as in the nineteenth century public subscription model. As noted, lotteries disproportionately collect from less-well off areas without guarantees that those same areas will benefit (Pickernell et al., Citation2004). Adding to this potential geographic discrepancy, as argued by Brecher and Wise (Citation2008), the role played by the HLF and their Parks for People scheme introduces a particular set of community and heritage interests and metrics. While we do not argue that our case is an example of funds moving from less-well off areas to affluent areas necessarily or of a funder imposing inappropriate interests, it is an example of how both are possible within the current funding model.

Moreover, we argue that the creation and refurbishment of Peel Park demonstrates municipal entrepreneurialism. With insufficient municipal or government funding, additional funds were sought from public subscriptions (nineteenth century), and from a competitive HLF grant, from private developer contributions and negotiated third party contributions (twenty-first century). As Lauermann (Citation2018) argues, the entrepreneurial municipality can incorporate other politics alongside growth politics, allowing space for diversified interventions and alternative measures of success. In this case incorporating competitive and collaborative ways of securing funding, with heritage or community metrics usurping economic growth as the measure of success. We argue that the history of Peel Park in particular may have influenced the entrepreneurial spirit with which the intervention was approached. As we have established, Peel Park as ‘a park for the people’ was part of its foundations and heavily lent on in its refurbishment—therefore, the logic for measuring success against community and heritage politics rather than economic growth could be justified by its 170-year history as a public park.

It is important to also consider the space for progressive politics within entrepreneurial actions, given this cannot be assumed (Lauermann, Citation2018). In the UK the National Lottery can be seen as a form of hypothecated tax, with revenues ringfenced for activities additional to essential government spending (Pickernell et al., Citation2004). While keeping in mind the impact of austerity on local authority budgets (Gray & Barford, Citation2018), the need for HLF funding categorises public parks, at least partially, as additional activity. This message is repeated by the national government as public park provision is not a statutory duty for local authorities (Department for Communities and Local Government, Citation2011a, Citation2011b). We argue that when funding for essential maintenance is drawn from the National Lottery and when public park provision is a non-statutory duty, this reflects the conditional value attributed to public parks. Meaning that although entrepreneurial, the politics driving the refurbishment of Peel Park cannot be assumed to be a progressive divergence from neoliberal growth politics. This is hinted at in development planning documents as the park features as a potential driver of future growth (University of Salford & Salford City Council, Citation2019). Highlighting the space for diverse politics in the entrepreneurial municipality.

Our analysis of Peel Park has provided evidence of its longstanding social and community goals. While these goals have evolved for the twenty-first century, we argue that understanding park quality and access to good quality greenspaces as part of underlying equality issues is crucial. We argue also that the diversified funding model and more-than-economic success metrics can be cautiously seen an example of the entrepreneurial municipality. An approach perhaps bolstered by a clear historical precedent. That the politics of growth is waiting in the wings for Peel Park is also evidence of the parallel politics possible within the entrepreneurial city. Future work could usefully expand on this discussion to analyse the environmental politics of public parks, as well as considering how the politics of park creation have evolved by comparing our discussions with the politics and creation of new parks.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff of the Salford Local History Library, Manchester Cental Library Archives and Special Collections, and Salford City Council and the Peel Park Rangers for their support in locating and providing the historic and contemporary documentary evidence for this work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Samuel J Hayes

Samuel J. Hayes is a planner and geographer, currently Research Fellow at the University of Salford (UK). His research and teaching interests are related to environmental planning, our relationships with green spaces and nature, and the related politics. His current research is concerned with the connections between physical activity (currently running), green spaces, and our health and wellbeing. He is also researching broader issues of historic and contemporary green spaces. He is interested in using Lefebvre’s rhythmanalysis, mobile methods, and creative and participatory methods to understand affective and lived experiences of green spaces and nature. He tweets at @DrSamHayes1.

Bertie Dockerill

Bertie Dockerill is an urban planning historian, currently Senior Tutor in the School of Environment, Education, and Development University of Manchester (United Kingdom). His principal research interests relate to the development of working-class municipal housing in the late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century. More broadly, his research focuses on measures introduced to improve the health and well-being of inner-urban residents in this period, such as municipal parks and wash houses, and how centrifugal forces such as the expansion of intra-urban rail and tramway networks impacted the nature of urban form.

Notes

1. Public walkways have been a feature of British towns and cities since the seventeenth century and were commonly places for people to walk and be seen in public. They often followed riverbanks, were tree lined or provided pleasing vistas (O’Reilly, Citation2019).

2. Rational recreation typically describes forms of recreation which reflected the ideals and morals of the bourgeois classes to encourage sobriety, respectable conduct and learning set against supposed working-class culture including licentious and gregarious activities (O’Reilly, Citation2019).

3. Respectively, philanthropist and founder of the Manchester Mechanics Institute; MP for Manchester 1832–1847.

4. MP for South Lancashire 1835–1846.

5. Noted Chartist, Manchester Councillor, Liberal radical, and subsequent Mayor of Manchester.

6. A subsequent meeting of working-class citizens in Salford was held on 25 September. Though it was reported to have been ‘well attended’ and that attendees were similarly supportive, no precise details are given (see Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser, Citation1846).

7. The cost of securing the land upon which to buy the parks had left the PPC with only £7,000 for furnishing the parks (Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser, Citation1846).

8. The MP who, in 1833, moved that the House of Commons should establish a Select Committee ‘to consider the best means of securing open places in the neighbourhood of great towns, for the healthful exercise of the population’ (Hansard, 21 February Citation1833).

9. Although not part of our core analysis which is focused on the refurbishment of the park leading up 2017, this evidence set alongside the current #BlackLivesMatter movement shows the relevance of understanding how parks are part of wider inequalities.

References

- Barker, A., Crawford, A., Booth, N., & Churchill, D. (2019). Everyday encounters with difference in urban parks: Forging ‘openness to otherness’ in segmenting cities. International Journal of Law in Context, 15(4), 495–514. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744552319000387

- Beckett, B. (2005). City Status in the British Isles, 1830-2002. Ashgate.

- Benedict, M. A., & McMahon, E. T. (2002). Green infrastructure: Smart conservation for the 21st century. S. W. Clearinghouse.

- Benedict, M. A., & McMahon, E. T. (2006). Green infrastructure: Linking landscapes and communities. Island Press.

- Brecher, C., & Wise, O. (2008). Looking a gift horse in the mouth: Challenges in managing philanthropic support for public services. Public Administration Review, 68, S146–S161. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2008.00985.x

- Burnett, C. (2014). Peel park conservation plan. Salford City Council.

- Collins, T. (2016). Urban civic pride and the new localism. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 41(2), 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12113

- Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment. (2010). Community green: Using local spaces to tackle inequality and improve health. CABE.

- Coutts, C. (2016). Green infrastructure and public health. Routledge.

- Cowden, S., & Singh, G. (2017). Community cohesion, communitarianism and neoliberalism. Critical Social Policy, 37(2), 268–286. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261018316670252

- Department for Communities and Local Government. (2011a). List of statutory duties - DCLG owned (revised 30 June 2011). Retrieved November 29, 2019, from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/review-of-local-government-statutory-duties-summary-of-responses–2

- Department for Communities and Local Government (2011b). List of statutory duties - other government departments (revised 30 June 2011). Retrieved November 29, 2019, from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/review-of-local-government-statutory-duties-summary-of-responses–2

- Doyle, B. (2000). The changing functions of urban government: Councillors, officials, and pressure groups. In M. Dunton (Ed.), The Cambridge urban history of Britain, Volume III, 1840-1950 (pp. 287–314). Cambridge University Press.

- European Union. (2013). Building a green infrastructure for Europe. Retrieved November 29, 2019, from http://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/ecosystems/docs/green_infrastructure_broc.pdf

- Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12(2), 219–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800405284363

- Gray, M., & Barford, A. (2018). The depths of the cuts: The uneven geography of local government austerity. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(3), 541–563. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsy019

- Greenspace Management and Development. (2016). Peel Park, Salford: Landscape management plan. Salford City Council.

- Greenspace Management and Development. (2017). Peel Park, Salford: Management plan 2018-2023. Salford City Council.

- Hansard. (1833). House of Commons 3rd Series, Volume 15, col. 1049 (21 February 1833). HMSO.

- Jacobs, J. (1961). The death and life of Great American Cities. Penguin Books in association with Jonathan Cape.

- Keeling, N. (2018, 26 May).The statue of much-loved MP has returned to a Salford park. Manchester Evening News. Retrieved November 29, 2019, from https://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/greater-manchester-news/statue-much-loved-mp-returned-14703665

- Keil, R. (2009). The urban politics of roll‐with‐it neoliberalization. City, 13(2–3), 230–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604810902986848

- Lauermann, J. (2018). Municipal statecraft: Revisiting the geographies of the entrepreneurial city. Progress in Human Geography, 42(2), 205–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132516673240

- Layton-Jones, K., & Lee, R. (2008). Places of health and amusement: Liverpool’s historic parks and gardens. English Heritage.

- Lovell, L. (2017, 10 October).Five must-see events at Salford’s food and drink fortnight - including a new beer made for the city. Manchester Evening News. Retrieved November 29, 2019, from https://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/whats-on/food-drink-news/salford-food-and-drink-fortnight-13740806

- Luczak Associates. (2015). Peel Park: Parks for people round II application management and maintenance plan. Salford City Council.

- Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser (MCLGA). (1844a). Formation of Public Parks in Manchester. 10 August 1844.

- Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser (MCLGA). (1844b). Public Parks, Walks and so on in Manchester, Aggregate Meeting of the Working Classes. 14 September 1844.

- Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser (MCLGA). (1846). The Public Parks. 26 August 1846.

- Manchester Guardian. (1846a). Salford council and the public parks. 22 August 1846.

- Manchester Guardian. (1846b). Official Inspection of the Manchester Public Parks. 19 August 1846.

- Manchester Guardian. (1846c). The Public Parks. 2 September 1846.

- Manchester Town Council. (1845). Proceedings 1844-1845.

- Mell, I. C. (2019). Beyond the peace lines: Conceptualising representations of parks as inclusionary spaces in Belfast, Northern Ireland. Town Planning Review, 90(2), 195–218. https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.2019.13

- Mell, I. C. (2020). The impact of austerity on funding green infrastructure: A DPSIR evaluation of the Liverpool Green & Open Space Review (LG&OSR), UK. Land Use Policy, 91, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104284

- Mell, I. C., Henneberry, J., Hehl-Lange, S., & Keskin, B. (2013). Promoting urban greening: Valuing the development of green infrastructure investments in the urban core of Manchester, UK. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 12(3), 296–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2013.04.006

- O’Reilly, C. (2013). “We have gone recreation mad”: The consumption of leisure and popular entertainment in municipal public parks in early twentieth century Britain. International Journal of Regional and Local History, 8(2), 112–128. https://doi.org/10.1179/2051453013Z.0000000009

- O’Reilly, C. (2019). The greening of the city: Urban Parks and public leisure, 1840-1939. Routledge.

- Office for National Statistics. (2020). One in eight British households has no garden. Retrieved July 9, 2020, from https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/environmentalaccounts/articles/oneineightbritishhouseholdshasnogarden/2020-05-14

- Ordnance Survey. (1850). Manchester & Salford Town Plan. Sheet, 21(1), 1056.

- @PeelParkSalford. (2017). The fire garden [Facebook Photo Album]. Retrieved November 29, 2019, from https://www.facebook.com/pg/PeelParkSalford/photos/?tab=album&album_id=1959867180929897&ref=page_internal

- @PeelParkSalford. (2018). Peel park official opening & Joseph Brotherton [Facebook Photo Album]. Retrieved November 29, 2019, from https://www.facebook.com/pg/PeelParkSalford/photos/?tab=album&album_id=2051554605094487&ref=page_internal

- @PeelParkSalford. (2019). Events. Retrieved November 29, 2019, from https://www.facebook.com/pg/PeelParkSalford/events/

- Pickernell, D., Brown, K., Worthington, A., & Crawford, M. (2004). Gambling as a base for hypothecated taxation: The UK’s national lottery and electronic gaming machines in Australia. Public Money & Management, 24(3), 167–174. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9302.2004.00414.x

- Reeves, N. (2000). The condition of public urban parks and greenspace in Britain. Water and Environment Journal, 14(3), 157–163. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-6593.2000.tb00244.x

- Reid, D. (2000). Playing and praying. In M. Daunton (Ed.), The Cambridge urban history of Britain, Volume III, 1840-1950 (pp. 745–810). Cambridge University Press.

- Rosenzweig, R., & Blackmar, E. (1992). The park and the people: A history of Central Park. Cornell University Press.

- Roue, L. (2017, 11 October). One million pound arts hub opens in Salford. Manchester Evening News. Retrieved November 29, 2017, from https://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/business/business-news/one-million-pound-arts-hub-13745401

- Salford Borough Council. (1847). Proceedings and reports.

- Salford Borough Council. (1848). Proceedings and reports.

- Salford City Council. (2015a). Joint report of the strategic director environment and community & the development director.

- Salford City Council. (2015b). Peel park stage 2 HLF submission - February 2015 Activity Plan.

- Salford City Council & Urban Vision. (2013). Peel Park heritage Lottery Fund Bid 2013: Supporting document parks for people programme. Salford City Council & Urban Vision.

- Sharples, J. (2018). The residential development of Sefton Park, Liverpool. Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, 165, 57–78. https://doi.org/10.3828/transactions.165.6

- Silveirinha de Oliveira, E., & Ward Thompson, C. (2015). Green infrastructure and health. In D. Sinnett, N. Smith, & S. Burgess (Eds.), Handbook on green infrastructure. [electronic book]: Planning, design and implementation (pp. 11–29). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Sinnett, D., Smith, N., & Burgess, S. (2015). Introduction. In D. Sinnett, N. Smith, & S. Burgess (Eds.), Handbook on green infrastructure. [electronic book]: Planning, design and implementation (pp. 1–7). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Taylor, H. A. (1995). Urban Public Parks, 1840-1900: Design and meaning. Garden History, 23(2), 201–221. https://doi.org/10.2307/1587078

- University of Salford & Salford City Council. (2019). Salford crescent & university district development prospectus: City making in action Salford’s bold vision.

- Urban Vision. (2015). Peel Park and Salford Museum & Art gallery frontage improvements master plan UV005215-L-104 Rev D.

- Wright, H. (2011). Understanding green infrastructure: The development of a contested concept in England. Local Environment, 16(10), 1003–1019. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2011.631993

- Yin, R. K. (2012). Applications of case study research. SAGE.