ABSTRACT

Landscapes as dynamic relations between people and worlds are always incomplete. They are partial understandings, evolving knowledges, edited images and unfinished stories of our designed and undesigned environments. Gaps within and between landscapes can reveal histories omitted and individuals silenced, but this open-endedness of landscapes can also provide opportunities to contribute and participate. In this paper I explore how landscapes are always under construction and I argue that their incompleteness offers potential for new practices. I question, how traditions of mapping can reflect dynamic realities of landscapes; how design and representational practices that attempt to fix time and complete space can work with incompleteness; and how designers and researchers can embrace such landscapes as open-ended, collective endeavours. In this paper, I discuss a mapping project called ‘Incomplete Cartographies’—an experiment with in-progress cartographies, incrementally informed by situated narratives, and producing new forms of belonging.

As we could expect from a paper with ‘incompleteness’ in the title, this text is a work in progress that represents a moment in time in an ongoing research project titled ‘Incomplete Cartographies’—a project of open-ended and collaborative mapping of landscapes that are in-process. There is one question at the core of the project that has enabled my students, colleagues and me to explore other ways to research and design landscapes: How can we work with landscapes in process—through inclusive practices that combine data collected through research with projective design approaches and are informed by situated accounts from less trained individuals. In 2016, I initiated Incomplete Cartographies to explore techniques of open-ended co-authored mapping that span site-based research and design projections. Incomplete Cartographies has since been developed through interdisciplinary student workshops, initially in London (in Advanced Landscape and Urbanism, University of Greenwich), then explored further in Vienna (in SKuOR, TU Wien).

The aim has been to explore techniques that facilitate in-depth engagement with site-specific narratives, from undocumented accounts of places to collective biographies of communities. In recognising that landscapes are processes, a conception of landscape that is increasingly accepted in ecological, architectural and sociological disciplines, their open-ended nature leaves them difficult to understand as design projects and problematic to frame in visual representations. The promise of permanence and aspirations for spatial fixity within traditions of architectural design, represented to clients through static drawings (of plans, sections and visualisations), fails to respond to landscapes that are constantly under construction through human and non-human processes. As mapping can also be considered a process (see Cosgrove Citation1999), of gathering, editing and sharing knowledge, it demonstrates a potential medium to explore and represent dynamic landscapes. Mediating between people, their surroundings and designed futures, maps can also become platforms for forging new forms of citizenship. Through situated conversations about places that are both familiar and unknown, Incomplete Cartographies asks people to draw (and redraw) their relations with the worlds around them. Citizenships understood through relations of belonging, rather than through state mechanisms and nationhood, can be made and reinforced by establishing conversations and producing representations of the streets, neighbourhoods and surroundings in which we live.

Furthermore, if landscapes are also understood through our perception—Barbara Bender reminds us that ‘In the contemporary western world we “perceive” landscapes’ (Bender, Citation1993, p. 2)—whether through single, ego-centred viewpoints or more collective, mobile, unstable or subjugated positions, we must accept perceptions to be partial and multiple. There are no singular landscapes of places. The goal of a totalising vision of landscape is also unachievable,Footnote1 whether by the human eye or mediated through technologies of black mirrors, photography, digital scanners and remote satellites. Such totalising pursuits through military mapping, territorial claims or architectural design can undermine the capacity of landscape as effective mediums for creatively situating and working narratives of places in open inclusive ways. Donna Haraway states in ‘Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective’: ‘The moral is simple: only partial perspective promises objective vision’ (Haraway, Citation1988, p. 583).

This paper sets out the pedagogic process of the Incomplete Cartographies project. I begin with arguments that intertwine several theories and practices of working with incompleteness as I propose relate to landscape. I then describe the Incomplete Cartographies project that has attempted to explore these questions within and outside of the context of the university. In the final section of the paper, I offer several points for discussion, findings that relate to incompleteness in mappings, situating and belonging.

Contexts

Landscape and other landscapes

Landscapes are defined by our relationships with the worlds around us, and as these relations are mediated by our experiences and perceptions we can recognise the subjective positions and partial perspectives from which they are composed. Landscapes are also piecemeal compositions in which understandings are constantly made and remade from incomplete knowledge. Such a definition contrasts with European conceptions of landscape as a way of seeing employed to frame, beautify, and commodify lands (and representations of them), from singular positions of power (see Cosgrove, Citation1984). In ‘Prospect, perspective and the Evolution of the Landscape Idea’ Denis Cosgrove provides a detailed critique of landscape understood in these terms (Cosgrove, Citation1984). He explains that the development of landscape as a visual medium, one that has historically been employed in navigation, mapping and artillery and—as Bender claims in Landscape: Politics and Perspectives (Bender, Citation1993)—draws associations with the origins of landscape in Western European terms and the founding of merchant capitalism in the sixteenth century. These are landscapes attempting to claim complete vision, affording power to a few individuals who seek to control, commodify and condition the environment. However, while Cosgrove critically describes historic trajectories of landscapes since the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, Bender goes further to advocate exploring ‘other ways of understanding and relating to the world—other landscapes’ (Bender, Citation1993, p. 3).

It is from this understanding of the existence and potentiality of ‘other landscapes’ that may exist ‘at the same time and the same place’ (Bender, Citation1993, p. 3) that I began the Incomplete Cartographies project with students in London in 2016Footnote2. How can we work with accounts of places, individuals and communities—forming landscapes understood as collective (sometimes entangled) stories of human and non-human processes, bringing together daily routines and regional ecologies, geological formations, and climatic changes, disrupted habitats and accelerating urbanizations? For the Incomplete Cartographies project we set out to investigate landscapes as ‘situated and embodied knowledges’ (Haraway, Citation1988, p. 583). These are landscapes that aim to reveal the means from which they are made, that resist the urge to beautify, and that are less ‘ego-centred’ (see Bender, Citation1993), providing for shared concerns: ‘Situated knowledges are about communities, not about isolated individuals’ (Haraway, Citation1988, p. 590). They are landscapes as pluralities, situated within times and places. They accept the simultaneity and tension between intersecting narratives of the same place,Footnote3 that deny linear structures of time, that fluidly move between historic accounts, daily occurrences, and future imaginaries.

Mapping processes

If, as I describe in the introduction, landscapes are in the process of being constantly made and remade then we must accept them as never complete, never finished. To work with landscapes of temporality we are confronted with and should seek to address: What are the processes of change? Who and what is most impacted as landscapes are continuously reconstituted? Who is afforded agency to inform change? How can people engage with and represent landscapes? For planners and designers working with landscape there is a need for methods that recognise the spatial and temporal dimensions of these relationships. It is necessary to recognise the components and agents of landscape processes as much as the processes themselves. In ‘Landscape as Provocation: Reflections on Moving Mountains’ (Massey, Citation2006) Massey points to the significance of discourses that give emphasis to ‘constant movement, the inevitability, and inexorability of process (rather than entity); on flow rather than territory’ (Massey, Citation2006, p. 40). But she also highlights that this is a ‘conceptual issue’:

Of course, in the practical conduct of the world we do encounter ‘entities’, there is on occasion harmony and balance; there are (temporary) stabilizations; there are territories and borders (and in the age of globalization the continuous production of these is important to register, and their political significance and contradictions are multiple …) (Massey, Citation2006, p. 40)

In this context, we can accept that the different processes and changing perceptions transform landscapes—from erosion of rocks by weathering to constructions of large urban infrastructures and from forming first impressions upon arrival in cities to developing senses of belonging through longer patterns of inhabitation. But how do we therefore simultaneously work with ‘entities’ as well as ‘processes’, accepting the need to register the things that are in process as well as the constant movements of change (whether at speeds too fast to register or those that seems imperceptibly slow)?

A situatedness in time (as well as space), that allows material entities to be understood as well as the processes from which they are being formed, provides a useful starting point for mapping. As Cosgrove suggests (Citation1999, p. 2), maps are also never complete: they are as much processes of mapping as they are a completed representation.

Their apparent stability and their aesthetics of closure and finality dissolve with but a little reflection into recognition of their partiality and provisionality, their embodiment of intention, their imaginative and creative capacities, their mythical qualities, their appeal to reverie, their ability to record and stimulate anxiety, their silences and their powers of deception. (Cosgrove Citation1999, p. 2)

Through the recognition that landscapes and mapping can be described in similar terms, mapping rather than architectural drafting provides a means through which landscape as process could be effectively employed. To work with the incompleteness of mapping (as many other landscape representations) highlights the partial perspective that Haraway describes (Haraway, Citation1988, p. 583). It also allows for a stronger argument into the subjective, incomplete nature of both landscapes and maps. Incompleteness of mapping points to well-rehearsed critiques of mapping—a medium of representation that is bound up with subjectivities and inaccuracies—but also techniques that open up its potential as a collaborative activity of exploration and imagination.

On accepting only partial perspectives of landscape and mapping there is a question as to what is included and what is excluded from view. If not everything and everyone can be included in these processes who are the authors and what are the valid accounts? Recognising the importance of specific perspectives of vision Haraway writes that there is ‘ … good reason to believe vision is better from below the brilliant space platforms of the powerful’ (Haraway, Citation1988, p. 584). She argues that to take the standpoint of the subjugated may provide ‘ … more adequate, sustained, objective, transforming accounts of the world’ that can challenge totalising claims and visions of scientific authority. In the construction of Incomplete Cartographies, we have found, however, usefulness in exploring tensions between different partial perspectives, from those of researchers and designers as well as those of less trained individuals. Reflecting on findings from the essay ‘Post-landscape or the potential of other relations with the land’ (Wall, Citation2017), the need for multiple, collective and less static perspectives from which to understand and form landscapes highlights conflicts within and between landscapes. Investigating accounts of street vendors that challenge narratives of BIDs (Business Improvement Districts) and descriptions provided by local government planners that deny concerns raised by displaced residents can reveal issues at stake as these landscapes are produced. Mapping also points to a potential agency and activism in addressing such concerns. In his essay, ‘The Uses of Cartographic Literacy: mapping, Survey and Citizenship in Twentieth-Century Britain’ David Matless explains:

Critical analysis of cartography have aligned maps with an impulse to dominate: land, people, things, properties, colonies. The cartographic eye is equated with the eye of power-as-domination. Alternatively maps are claimed as a vehicle of resistance, a language whereby rights to place may be asserted or through which non-dominatory representations might be cultivated. (Citation1999, p. 193)

While it remains an impossibility to gain a ‘complete’ range of perspectives, conflicts between accounts can reveal both the uneven nature of landscapes from below as well as forms of strategic planning, political agendas, and economic power that come to bear on specific communities.

Approach

Incomplete cartographies

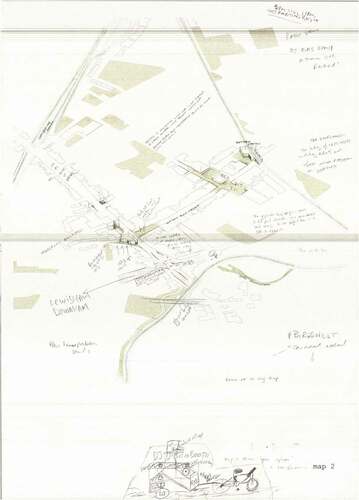

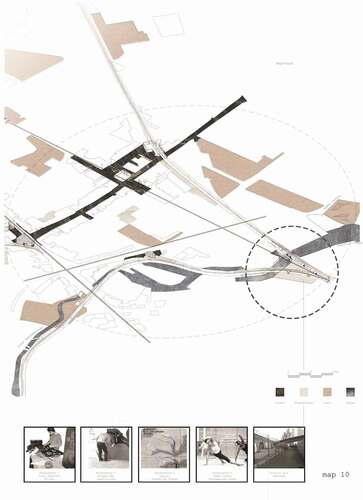

With these texts in mind and a frustration with prevailing approaches to designing landscapes I initiated the Incomplete Cartographies project—an open-ended and collaborative process of bringing situated accounts together with more comprehensive data sets, through drawing, editing, analysing and projecting future visions for places. Incomplete Cartographies has three main stages: firstly, researchers and/or designers work as primary authors to frame an investigation of a specific place by creating an incomplete map. Through collecting information (from field and desk studies, from client briefs and document surveys, from primary and secondary data) and editing, sifting, working and synthesising what is found into a single map, an initial question or focus is framed. Leaning on traditions of landscape architecture research that aim to identify unique qualities or conditions of landscapes, the production of the first map is focused on site-specific issues of concern. The first maps produced by students highlighted patterns of development, ecological challenges, exclusion of individuals, future infrastructures, street conditions and lost histories. James Corner asserts in ‘The Agency of Mapping’ that: ‘Analytical research through mapping enables the designer to construct an argument, to embed it within the dominant practices of a rational culture … ’ (Corner, Citation1999, p. 251). Reflecting the landscapes investigated, the maps were partial constructions of the world that the students were researching. As Cosgrove reminds us, ‘ … all mapping involves sets of choices, omissions, uncertainties and intentions … ’ (Cosgrove, Citation1999, p. 5). The first map (see ) thus frames an argument, with the partial register of the first map leaving intentional gaps and strategic voids that pose questions and encourage further adding to the map in subsequent stages of the process.

Figure 1. Base drawing of sounds in Deptford, London (Toya Peal, MA Landscape Architecture, University of Greenwich, 2016)

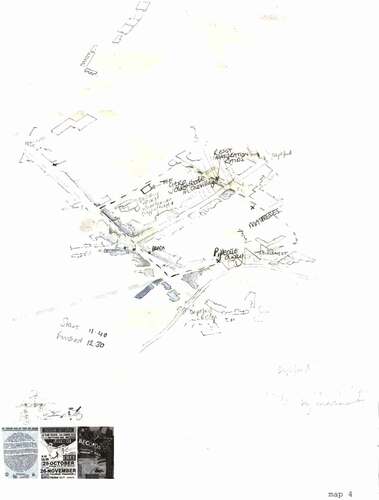

In the second stage, a print of the incomplete maps that were produced in the first stage were used as a means to engage in conversations and to conduct semi-structured interviews with individuals and groups who had knowledge of the area or who had a stake in processes of change (See ). Open-ended questions were asked about the issues framed in the incomplete map, and through the course of the interview residents, dog walkers, local business people and tourists were asked to visualise their account by drawing on the map. During the conversation both interviewers and interviewees added to the maps, visualising the narratives described by the interviewee. Through the processes of the interviews the mappings revealed accounts of places impossible to understand through methods such as document surveys or observation alone. The selection of interviewees was based on the issues identified in the first stage of the process, considering narratives less present online, in libraries or archives. The accounts presented during interviews related to what Massey terms ‘stories-so-far’ in the ‘process of change in a phenomenon’ (2005, p. 12). Massey states (2005, p. 9):

… space as always under construction … it is always in the process of being made. It is never finished, never closed. Perhaps we could understand space as a simultaneity of stories-so-far.

Figure 2. First conversation developing additional knowledge over base drawing (Toya Peal, MA Landscape Architecture, University of Greenwich, 2016)

Semi-structured interviews do not neatly limit interviewees to describing linear historic narratives but instead they provide for conversations that jump between different time periods, from the present day, to future concerns to past events. The edited maps were not limited to providing an archive of past or future events, spaces made or unmade, instead, as Cosgrove explains of mapping, ‘ … it includes the remembered, the imagined, the contemplated’ (Cosgrove, Citation1999, p. 2). In the context that Incomplete Cartographies have been explored in sites of intense ongoing urbanisation (such as London) it would be unusual for the lives and work of interviewees to not be concerned with future plans for their streets, neighbourhood and cities. Having opinions, desires and dreams that correspond or react against formal planning processes establish Incomplete Cartographies as a means through which interviewees untrained in designing cities can engage in the ‘ … imaginative scope and projective power of mapping’ (Cosgrove, Citation1999, p. 1).

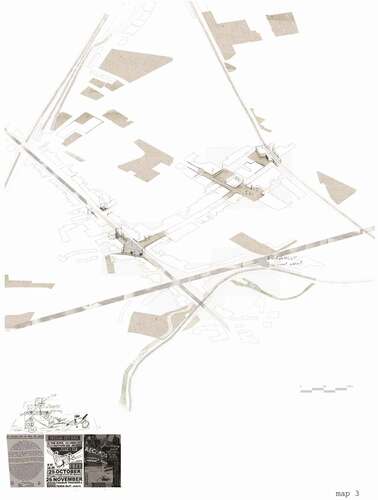

The third stage involved the primary author translating the information added during the interview, analysing, editing and synthesising accounts from the interview to the first incomplete map (See ). Stage two and three were repeated many times. We found that some primary authors working with Incomplete Cartographies used a snowball technique, a useful approach of identifying subsequent interviewees based on what was learnt from earlier interviews. One of the students notes: ‘Patterns of use and process began to emerge which would lead to further questions and prompted me to identify new people to talk to’ (Student discussion 2016). This allowed the primary author to reflect at each stage on what has been learnt and to consider what narratives should be sought. The synthesising of information into the map also provided opportunities to visualise some of the interview transcript into the map—especially where the interviewee chose not to or was unable to mark the map. Importantly for subsequent stages, the primary author also needed to ensure that the map retains (and appears to retain) an incompleteness in information so as to encourage subsequent interviewees to contribute their narratives onto the in-progress map.

Figure 3. First conversation synthesised and consolidated (Toya Peal, MA Landscape Architecture, University of Greenwich, 2016)

Different disciplines and practices involved in research and design of landscapes (from anthropology to architecture and from ecology to engineering) may argue over how many times these stages should be repeated to gain knowledge that effectively represents the people and places in question. With Incomplete Cartographies limited to the semester structure, students themselves identified the need for more time: ‘This exercise would benefit from a longer time scale’ (Student discussion 2016). However, we can also recognise the importance of these ‘stories-so-far’ that go some way towards establishing inclusive practices of design that highlight the in-progress nature of mapping practices. The beginning of the project process may be explicitly marked by the production of the first map, but we found the end point difficult to ascertain. With more and more authors included we also found that commonalities began to emerge as well as clear ambitions for the future of places.

Discussions

As described at the outset of the paper the Incomplete Cartographies research is ongoing. There are, however, several points of reflection that unpack this specific approach to situating, mapping and belonging.

Situating

During the project, mapping has proved an important action for gathering stories of places and situating them with other sets of information. Maps have been important mediators between architectural traditions of plan and masterplan drawings, geographical surveys and territorial representations and ways of reading landscapes from less professional positions. While Cosgrove writes that ‘ … the map is a ubiquitous feature of daily life’ (Cosgrove, Citation1999, p. 2) we found that the spatial and drawing skills of the primary author were often more important in the process than those of the interviewees who were sometimes hesitant to draw. However, a general literacy in regard to maps and the willingness of people to describe directions and situations in relation to the mapsFootnote4 provided an accessible technique for visualising conversations about places. During the research we found that interviews with people who lived or worked locally and who could appreciate the research being undertaken by the students also provided more spatialised knowledge than interviews with visitors less familiar with the study area or the students’ work.

The mapping became an incremental process of learning for the students as contrasting accounts were brought together to form collective and situated knowledge. Matless writes that ‘Thinking is like making and using a map, and mapping is necessary for thought’ (Matless, Citation1992, p. 198). The mapping was complimentary to the verbal accounts of interviews, which often follow simple linear chronologies—the map acted as both a prop as well as a reference during conversations. The maps situated, spatialised and synthesised multiple narratives, forming landscapes as relationships between people and their surroundings. Reflecting on the Incomplete Cartography approach, one of the students stated: ‘Interviewees enjoyed talking about human relationships in the area, which has been useful to my understanding of the social landscape’ (Student discussion 2016). Describing the development of Regional Survey in early twentieth-century Britain, and the aerial maps produced, Matless, claims that maps have less to do with what Haraway terms ‘a totalising visual “god-trick”, a conquering gaze from nowhere’ (CitationMatless, 1992, p. 212), instead he describes them as ‘a sky situated knowledge’. While the elevated position adopted in Incomplete Cartographies may visually resonate with traditions of mapping as surveying, controlling and enclosing lands, the techniques of production contrast significantly to privilege collective accounts, including the partial perspective of the ‘subjugated’.Footnote5

We recognised that it was important to use the maps to make sense of and situate local historical accounts, alongside more official planning narratives: ‘This technique has allowed me to see the spatial correspondences between layers of historical information, present land use and hidden anecdotal information’ (Student conversations 2016). As such, the maps quickly became quite dense with information (see and ) that required care and precision to read. We found that the third stage of analysing, questioning and editing the maps provided opportunities to make sense of what became multiple, partial, collective accounts of places that offered a more complete understanding. The process of mapping relied on the skill of the primary authors to ‘synthesise complex information onto single maps, with the judicious use of colour, texture and line, without losing, but in fact gaining understanding’ (Student conversations 2016). This highlighted the role of individuals with specific literacy and expertise in landscape. Working in this dialogical way relied on the primary author’s mapping skills and landscape experience to mediate the contrasting bodies of knowledge.

Figure 4. Second conversation adding further knowledge to map (Toya Peal, MA Landscape Architecture, University of Greenwich, 2016)

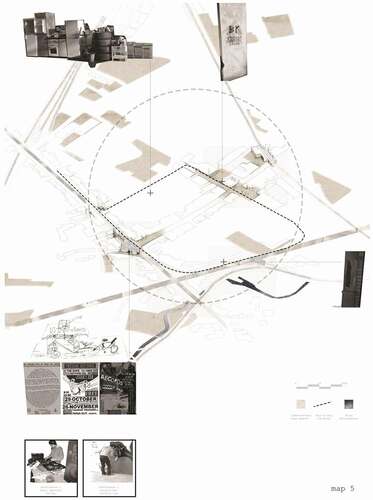

Figure 5. Second conversation synthesised and edited onto map (Toya Peal, MA Landscape Architecture, University of Greenwich, 2016)

We found that the process of adding to the maps provided an opportunity for individuals and communities to situate themselves in relation to their environments. Residents could contextualise ongoing redevelopments directed by commercial developers in relation to daily routines of crossing the park on the way to work. Children could illustrate their experiences and understanding of their neighbourhoods. Older people took time to share easily forgotten histories of past events and places changed. Some maps questioned claims by architects by grounding accounts of the past and proposals for future change. Talking down of neighbourhoods as a means to propose demolishing and rebuilding places were critiqued through knowledge that was both embodied and situated. The Incomplete Cartographies were able to form and situate knowledge and arguments.

Incompleteness

The incompleteness of the maps asks questions and opens up conversations. The gaps in the maps act like pauses where participants are encouraged to add their experiences and knowledge. While the incompleteness of the maps is a strategic device to engage with untold accounts it is also an important recognition that landscapes are collective relationships with places that defy solitary research approaches. Throughout the projects with the students we found that the emphasis on the process of mapping and the permanent incompleteness of the map was important. While the individual maps accrued significant detailed information the students found the process of interviewing, drawing and editing most useful: ‘I can see that although the “final” map of the series is a powerful tool for understanding the more elusive narratives of the place, each map is useful in and of itself. It is the process of editing that has been the most important thing’ (Student conversations 2016) (See ). The potential of Incomplete Cartographies seemed to lie in what Cosgrove describes as ‘ … processes of mapping rather than with maps as finished objects’ (Cosgrove, Citation1999, p. 1). The process provided reassurance for students and interviewees that there was a common ground of interest; the knowledge shared during the interview reminded students of the significance of local, less official narratives of places; accepting the subjectivity of mapping through producing a partial map forced the students to consider their own subjectivities; and the need to edit the map required a close reflection by the students on what had been discussed and an opportunity to test the direction of the research.

Figure 6. One of several ‘final’ drawings produced during the mapping workshop (Toya Peal, MA Landscape Architecture, University of Greenwich, 2016)

We also found that the practice of Incomplete Cartographies provided a unique learning tool for students. In order to engage in conversations with individuals less familiar with design drawings the students were required to provide a clear, well focused argument in the first stage of the work. The iterative development of the process allowed the students to learn from each stage of engaging with participants. Students learned the difficulty in identifying individuals who could provide otherwise untold accounts. They also recognised how keen many people are to speak about their situated knowledges and personal experiences. The incomplete map provided a useful mediator in the conversations between the students directing the projects and the residents, shop keepers, and visitors with whom many of the students spoke. One of the students recognised that the process had ‘ … revealed both hidden empirical “truths” and subjectively significant elements to me as the designer’ (Student conversations 2016). For some students, traditional practices of architectural drawing had previously excused them from engaging with or speaking with people who were part of the landscapes that they were studying. However, Incomplete Cartographies required conversations with people about places. During the process students recognised the possibilities of inventing new approaches in combining different methods, from different disciplines, and the potential that these experiments can offer. Rather than relying on prevailing design and drawing methods, the students found that reimagining site-specific methods within this framework of incomplete cartographies was highly effective in generating situated knowledges.

Belonging

The inclusive practice of asking people to situate themselves in a place opened up questions of belonging and citizenship. Matless claims that: ‘Survey and mapping can be understood in terms of cultivating a particular model of citizenship’ (Matless, Citation1999, p. 202). His exploration of maps as popular documents is concerned with ‘ … how the map should be used, who is able to use it, what forms of knowledge it should register, what kinds of citizenship it should cultivate’ (Citation1999, p. 194). The use of maps for situating ourselves in relation to our worlds can forge such belonging to places. Incomplete Cartographies do this by affording opportunity to co-author maps. In so doing the process of Incomplete Cartographies has the potential to further (and visualise) particular senses of belonging. By contributing knowledge, sharing aspirations for the future and making marks on maps individuals come to belong to landscapes. As with the incompleteness of the maps and the landscapes that they represent, we can understand multiplicity and incompleteness in notions of citizenship. We found that people expressed senses of belonging to multiple places, as interviewees differentially related to the street on which we live, the district in which we work, neighbourhoods of friends and distant places.

Belonging, like mapping, can be considered an open-ended process of making that is never complete.Footnote6 The Incomplete Cartographies recorded temporal and partial forms of belonging as well as the inclusion of some people in the citizenry of a place and the exclusion of others. Matless uses the term ‘anti-citizen’ to describe those excluded: ‘The ignorant and insensitive haunt geographical citizenship, which always works in relation to an ‘anti-citizen’ (Matless, Citation1996, p. 428). Exclusions may point to some of the limits of Incomplete Cartographies as a process that can struggle to be representative of a place or population. However, the practice of creating collective accounts through mapping provides a critical lens to the inclusivity of prevailing research and planning practices. It also returns to the question of how many individual accounts should be included and how long such participatory mapping should continue in order to form representative accounts.

Concluding

Returning to the question from which we began the project, we find that the techniques of mapping have proved effective in engaging with individuals less familiar with practices of planning and design. The inclusiveness of Incomplete Cartographies was one of the main aims of the project. Although the question of who is included or not in processes of remaking streets, neighbourhoods and cities should continue to be asked, we found that the students were able to include in their practice the narratives of often excluded individuals. The judgment of the primary authors to frame initial arguments and to invite subsequent interviewees to co-author and create collective mappings resulted in varied processes of inclusion. Set against the impossibility of accessing all people and all views, including the future perspectives of generations who will live with and in these designed projects, inclusiveness requires a continued practice that the open-ended Incomplete Cartographies could be able to facilitate.

The question of visualising and synthesising narratives that are frequently communicated in words is confronted in the Incomplete Cartographies project. Practices of site-specific research as the means to inform and structure landscape architecture proposals is commonly accepted. The Incomplete Cartographies approach enabled the visualising and synthesising of data from different disciplines that is often difficult to analyse and work with together—such as written documents, interviews and spontaneous conversations. While incomplete cartographies is just one way that this concern can be addressed, one that also depends on the skills of drawing by interviewees and the abilities of primary authors translating and synthesising, I would argue that it is essential to continue to both invent and critically question new ways of mapping. Cosgrove explains: ‘For a politically, economically, technically, and culturally globalizing world in which visual images have an unprecedented communicative significance, much is as stake in matters of space and its formal, graphic representation’ (Cosgrove, Citation1999, p. 4).

Where the end of this open-ended process resides is something that is also important to consider. If Incomplete Cartographies record existing and historical landscapes and include ambitions and ideas for the future, it seems to make sense that the process would continue into construction, maintenance, management and post-occupancy. While the student projects were limited to a semester and were not tasked with making physical transformations Incomplete Cartographies could provide a transparency and evidence of decisions, conversations and plans that impact neighbourhoods undergoing change. One of the recent adaptations that we have made to the Incomplete Cartographies approach is to add a register of additions to the map. So on the back of the composite maps the students have added a list of edits, authors and dates that allows the history of the map to be evidenced. The process of mapping, in this sense, becomes a living landscape archive that could be used to continually document, understand and learn from.

Finally, a means to recognise and work with landscapes that are constantly being made and remade through processes that are more or less informed by humans is a challenge. For Cosgrove, ‘ … the concept and practice of precise and permanent separation, of spatial “fixing”, inherent in boundary definition and conventional mapping … represent an urge towards classification, order, control and purification’ (Cosgrove, Citation1999, p. 4). These tendencies that can be traced through histories of designing cities and landscapes, from the invention of perspective to fashions of the contemporary picturesque, must be questioned for the totalising visions that they can claim and for the individuals, entities and practices that are left out. But in the context that landscapes, as Bender, Massey and others remind us, are continuously in process how can landscape architects find effective ways of working? In a partial response, Incomplete Cartographies have the potential to be open-ended documents that engage with landscapes inprocess, before design and planning, through transformative actions of construction and on to stages of use, occupation, maintenance and management. It is unlikely that this technique can replace practices of masterplanning that are more hierarchical and ordering, but there is potential in them informing wider planning practices. Maybe more importantly, as Matless describes of mapping (Matless, Citation1999, p. 193), Incomplete Cartographies could provide ‘a vehicle of resistance’ for communities to challenge traditional planning approaches, to offer other designs for the future and to establish equitable structures of change inclusive of residents and citizens.

Acknowledgments

Incomplete Cartographies has developed as a collective project with students at University of Greenwich, London, and TU Wien, Vienna and has only been possible with the generous contributions of interviewees participating in the process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ed Wall

Ed Wall is Associate Professor of Cities and Landscapes, Academic Portfolio Lead for Landscape Architecture and Urbanism, co-lead Faculty Postgraduate Research, and co-lead of the Advanced Urban research group. He is also Visiting Professor at the Polytechnic University Milan, Director of Project Studio, Founding Editor of Testing-Ground: Journal of Landscapes, Cities and Territories, and External Examiner at the Architecture Association. Ed is guest-editor of The Landscapists (Architectural Design/Wiley, 2020) and co-editor of Landscape and Agency: Critical Essays, with Tim Waterman (Routledge, 2017). He is currently co-editing two further books: Landscape Citizenships (with colleagues at UCL The Bartlett and University of Toronto) and Unsettled - Urban Routines, Temporalities and Contestations (with colleagues at SKuOR/TU Vienna). His research interests focus on relationships and processes of landscapes and cities– with a particular emphasis on urban equity and ecological justice through design practice.

Notes

1. The illusory capacity of landscape is well critiqued, as it relates to landscapes in process; see Lefebvre (Citation1991), Cosgrove (Citation1984), and Mitchell (Citation1997).

2. Also see Wall (Citation2017), questioning the positions taken to frame landscapes that are understood in visual terms.

3. As Bender explains ‘Each individual holds many landscapes in tension’ (Bender, Citation1993, p. 2).

4. See Harzinski (Citation2010).

5. See Haraway (Citation1988).

6. For more on belonging, citizenships, and landscape, see Wall (Citation2021).

References

- Bender, B. (1993). Landscape: Politics and perspectives. Berg.

- Corner, J. (1999). The Agency of Mapping In D. Cosgrove (Ed.), Mappings (pp. 213–251). Reaktion.

- Cosgrove, D. (1984). Prospect, perspective and the evolution of the landscape idea. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 10(1), 45–62. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/622249

- Cosgrove, D. (1999). Mappings. Reaktion.

- Haraway, D. (1988). Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3), 575–599. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066

- Harzinski, K. (2010). From here to there. A curious collection from the hand drawn map association. Princeton Architectural Press.

- Lefebvre, H. (1991). The production of space (trans.). Basil Blackwell.(Original work published 1974)

- Massey, D. (2006). Landscape as a provocation. Journal of Material Culture, 11(1/2), 33–48. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1359183506062991

- Matless, D. (1996). Visual culture and geographical citizenship: England in the 1940s. Journal of Historical Geography, 22(4), 424–439. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1006/jhge.1996.0029

- Matless, D. (1999). The uses of cartographic literacy: Mapping, survey and citizenship in twentieth-century Britain In D. Cosgrove (Ed.), Mappings (pp. 193–212). Reaktion.

- Mitchell, D. (1997). The annihilation of space by law: The roots and implications of anti-homeless laws in the United States. Antipode, 29(3), 303–335. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8330.00048

- Wall, E. (2017). Post-landscape or the potential of other relations with the land. In E. Wall & T. Waterman (Eds.), Landscape and agency: Critical essays (pp. 144–163). Routledge.

- Wall, Ed. (2021). Working with uncertainties: Living with master planning in elephant and castle. In T. Waterman, J. Wolff, & E. Wall (Eds.), Landscape Citizenships. Routledge. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003037163