Abstract

This paper focuses on the extraordinary 245-metre-long Pergola on Hampstead Heath, designed by renowned landscape architect Thomas Mawson between 1905 and 1925, and funded by William Lever, Lord Leverhulme, owner of the property. The paper focuses on the Pergola’s potential as an exemplar for considering more creative, sensory and sociable provision for urban pedestrians After detailing its origins and key features, the discussion explores the shifting uses of the Pergola over the past hundred years as it has changed from private realm to public space, yet these changes have accentuated its enduring landscape architectural qualities as a structure for pleasurable walking. The paper particularly focuses how the structure has been adopted as a contemporary site for walking and as a venue for numerous photographic and filmic practices. I conclude by suggesting that these virtues might inform more assiduous pedestrians provision following the rise in walking during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords:

During the recent lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic, many Londoners sought a brief, temporary escape by walking around their neighbourhoods. In so doing, they became newly acquainted with their surroundings, perhaps attending to formerly unnoticed features, wandering down hitherto unexplored byways or intensifying awareness of the affective and sensory impact of their locale. Such widely shared experience has renewed incentives to produce environments specifically designed for walking, spaces that draw pedestrians along lightly regulated, interesting, aesthetic and socially inclusive routes. Though functionalist road design still dominates transport and mobility planning, car use is increasingly regarded as unsustainable and ecologically harmful, and this is aligned with an emergent awareness that walking is beneficial to mental and physical health.

Accordingly, in seeking to explore how landscape architecture might rekindle Victorian and Edwardian enthusiasm for creating inventive pedestrian structures, this paper focuses on the Pergola designed by Thomas Mawson for Lord Leverhulme in Hampstead, London. In offering a stimulating sensory, social and interactive experience, the Pergola provides an exemplary design that contemporary landscape architects might emulate. In offering this contribution to reconsidering the importance of urban pedestrian experience, I firstly discuss ideas about walking and forms of landscape architecture that enhance pedestrian experience. I then outline a history of the Pergola’s origins and design, before exploring how its uses have changed over the past hundred years as it has moved from private realm to public space. Following this, drawing on participant observation and photography, I investigate the qualities that make this such a popular structure upon which to walk. Subsequently, I focus on the host of contemporary visual practices that are stimulated by the Pergola’s design.

Walking architectures

Pedestrians adopt multiple modes of walking shaped by social objectives, individual dispositions, cultural and historical conventions, and the spaces that are traversed (Edensor, Citation2000). Walking elicits well-being, is a practical means of travelling, fosters acquaintance with place, rumination, companionship, and opens the body up to sensation. While pedestrians adopt diverse styles of comportment, display, pace and rhythm (Edensor, Citation2010), particular spaces and landscapes cajole bodies into particular performances and generate specific experiences (Degen & Rose, Citation2012). As Rachel Thomas emphasises, ‘sensory configurations… are favourable, or unfavourable, to walking’ (Citation2010, p. 55); they inform whether pedestrians accelerate, linger and amble, walk cautiously or formally.

I argue that unfortunately, urban streets are often excessively regulated to minimise social and sensory experience, and functionally organised to maximise traffic flow, maintain public order and prioritise commerce. Generic design conventions typically erase local signifiers and peculiar sights (Julier, Citation2005, p. 874). Accordingly, contemporary urban streets are often unimaginative, untethered to place, and unstimulating (Sanders-McDonagh, Peyrefitte, & Ryalls, Citation2016). For Richard Sennett (Citation1994, p. 15), many streets are ‘a mere function of motion’ wherein speedy vehicular progress trumps pedestrian access and walkers are subject to perpetual scrutiny via CCTV systems. This is apt to tone down playfulness and deter loitering. While situationists and other alternative practitioners have sought to challenge these functional approaches, their walking activities are somewhat rarefied and specialist. Yet as Peter Blundell Jones (Citation2015, p. 4) contends, walking is part of everyday life, ‘the basis of who and where we are, the means by which we gather and separate, by which we first traverse territories and give them definition’. Accordingly, it seems critical that urban designers and planners should develop more sensorially stimulating walking spaces that encourage creativity and play.

There are several historical examples of inspiring landscape architectures designed purely for pedestrians. As Wendy Jacobson remarks (Citation2017, p. 39), ‘Mediterranean populations in Southern Europe have long been known for their formal evening ritual of walking along the paseo, the esplanada, or the corso’. Similar promenading took place in London’s Pall Mall, named after a game akin to croquet that required a linear stretch of land lined with shaded trees. Landscaped walks became key elements in the fashionable pleasure gardens of 18th and 19th century London (Conlin, Citation2008) and similarly, ‘oceanfront or riverine promenades throughout Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-century Europe took … their amenity from proximity to the water, views across it, and often from fresh breezes emanating from it’ (Jacobson, Citation2017, p. 50). As Jacobson (Citation2017, p. 53) emphasises, such pleasurable promenading practices ‘demanded routes that were diverse and interesting, relatively unimpeded, and lengthy enough for unhurried social encounters’. In seeking to rejuvenate city-dwellers, Victorians designed a range of perambulatory spaces in cemeteries and urban parks, and in beachfront piers and promendades.

In recent times, other infrastructural features have been repurposed for pedestrian use. Certain medieval city walls, such as Lucca in Italy and York in England, offer enticing circular walks, while New York’s celebrated High Line, Chicago’s Bloomingdale Trail and the Paris Promenade Plantée are innovative, highly designed walkways created on disused elevated railways. While certain forms of contemporary landscape architecture does encourage walking (Edensor & Millington, Citation2018), I argue that Hampstead Pergola offers an especially salient exemplar of how pedestrian realms might be inventively designed.

History of the Pergola: Lever and Mawson

In 1904, William Lever, Lord Leverhulme, doyen of the Lever Brothers soap company, purchased the Hill, a large Edwardian mansion on Hampstead Heath, London. The hugely wealthy, energetic Lever, champion of free trade, trade unionism, universal suffrage and the British Empire, became a Liberal MP, and in 1911 was made a baronet. The Hill was Lever’s London base for his political activities. It also offered opportunities to satisfy another of his passions, garden design, and he recruited eminent designer Thomas Mawson to create a 245-metre-long pergola, described by Katherine Swift (Citation2001, p. 85) as

a remarkable structure with its contradictory signals of exclusivity and openness… its extraordinary scale and its brilliant extempore handling of space, zig zags around what appears to be a precipice on the edge of West Heath like some great Indian fort, a shimmer of white stone columns above massive red brick arches and retaining walls

Translated as ‘a close walk of boughs’, a pergola is formed by a narrow linear walkway in which pillars support crossbeams and latticework covered in climbing plants that shade pedestrians. First used in ancient Egyptian gardens, pergolas were adopted by Greeks and Romans as structures in which to rest and entertain. During the Italian Renaissance, they served desires for imposing orderly geometric subdivisions and enclosed spaces (Lazarro, Citation1990). 19th century French Pergolas diverged in style and size, some with roughly designed trellises, others with elaborate lattices. Contemporary pergolas are fashioned from diverse materials including stainless steel and living willow (Claydon, Citation2001). Yet as Swift (Citation2001, p. 85) contends, the golden age of the British pergola was the Edwardian era in which wealthy industrialists and landed aristocrats funded creations that resonated with a ‘heady social mix of leisure, sensuality and affluence’. These Edwardian structures are epitomised by the Hampstead Pergola.

Leverhulme is renowned for the estates he created for himself, his workers and the public. At Rivington near Bolton, Lever’s hometown, Thomas Mawson created a vast landscape of moorland, woodland, lakes, terraced gardens, shelters and pavilions, criss-crossed with extensive paths and steps. While Lever retained 45 acres for his own use, 345 acres were donated to the people of Bolton (Beard & Wardman, Citation1978). On the great lawn, dance parties took place (Historic England, Citationn.d.). Lever’s house, with its glass roofed pergola, no longer exists. His best-known project, Port Sunlight on the Wirral, housed workers at his adjacent soap factory. Inspired by arts and crafts designs and garden city principles, the village included an art gallery and library but no pub.

In contrast to these paternalistic endeavours, Hampstead’s Hill Gardens and Pergola, surrounded on all sides by the public land of Hampstead Heath, were private, intended solely for Lever’s use. As a Liberal Member of Parliament for Wirral between 1906 and 1909, and as a peer from 1911, Lever was continuously engaged in public activities and political campaigns, and ‘needed a London base for entertaining his parliamentary colleagues’ (Waymark, Citation2009, p. 82). Accordingly, the Hampstead estate staged meetings with politicians, business associates, investors and employees, also serving, as Mawson (Citation1927) claims, as ‘a pleasant setting for the garden parties which are such a popular feature at The Hill, including each season, the entertainment of the members of many artistic and learned societies’.

Located on a high, sandy rise, The Hill overlooked a thickly wooded area of the Heath to the south that gave the impression of extensive rural space, so that ‘one would never imagine that there was a teeming population spread over the vast area visible, in part hidden away in slums, over which recuring groups of trees seemed to cast a foil’ (Swift, Citation2001, p. 88). In creating the gardens, soil was transferred from the excavations to create the new Northern Line underground railway that passed through Hampstead, which a large army of manual labour fashioned into containing walls ‘somewhat akin to a medieval castle’ (Waymark, Citation2009, p. 83), engineering works essential if ‘level lawns, so necessary to a town house where entertaining is to be done, were to be formed’ (Mawson, Citation1912, p. 340). In accommodating large garden parties, Lever did not want his guests to be ‘overlooked by heath-walking hoi polloi’ (City of London Corporation, Citation1996, p. 2). Mawson (Citation1927, p. 129) also reflects upon how this landscaping would also ‘keep open the panorama without in any way introducing a jarring note to the view of The Hill from the Common’.

The Pergola was constructed in three distinct phases. Between 1905 and 1906, the long section from south to north encloses the Hill House and gardens and changes direction twice. Along its length, evenly spaced timbers occasionally swell upwards to form domed latticed ceilings, supported by Doric stone columns bounded by lateral trellised walls on the north side. On the southern side, the stone pathway is bordered by balustrades overlooking the sharp drop to well-stocked gardens. Walking from the south, this earlier pathway culminates at a large, open tented, upcurved trellised roof structure. The second phase of building was initiated between 1911 and 1914 following Lever’s purchase of the adjoining Heath Lodge which was demolished to accommodate the Pergola’s extension. This short section consists of a flight of steps up to a small domed temple built on a bridge underneath a public path that Lever was unable to buy. Besides retaining the Pergola’s separation from public space, according to a City of London Corporation pamphlet (Citation1996, p. 5) this temple unobtrusively acted as a ‘knuckle’, an architectural device that eased the right angular change in direction ‘that might otherwise appear awkward’. The third phase of construction, between 1917 and 1920, continued westwards from the bridge for a further 100 metres. Possessing a double Doric colonnade sculpted from Portland stone, the path is level with the ground either side until to the right, views emerge of the formally laid out gardens that are accessible from the steps that descend at the end of the Pergola. Old climbing plants thickly colonise the columns and the original, decaying timbers. Though the most recently built section, this now appears to be the most venerable part of the Pergola. The long colonnade leads to a brick and limestone wall behind which lies a summerhouse and beyond this, a belvedere that rises above the beech, horse-chestnuts, oaks and elms and offers a scenic view of Harrow-on-the Hill, 6 and half miles away to the west.

Lord Leverhulme used his Pergola for his own exercise and enjoyment, and for post prandial strolling with visitors. Following his death in 1925, the Hill and gardens were purchased by Andrew Weir, Baron Inverforth, ship owner and president of Marconi companies. After Weir’s death in 1955, the house served as a convalescent home. In 1985, the Corporation of London claimed ownership of the property. Much of the stonework, pillars and wood has disappeared or collapsed, with many timbers twisted and rotted beyond repair. In 1992, renovation began. The lower floor was solidified with concrete, drainage improved, damaged brickwork refaced, ornamental arches replaced, and stone balustrades rebuilt. A steel trellis was created to separate the now public Pergola from the still private Hill House and lawns. 2200 cubic feet of French oak – equivalent to 300 trees – was imported to reconstruct the overhead beams intrinsic to the Pergola’s form, and the whole structure became subject to ‘a continuous care and maintenance programme, preserving the integrity of its fabric while still allowing it to age gracefully’ (City of London Corporation, Citation1996, p. 9). A planting scheme followed details from a 1912 issue of the Gardeners Chronicle, installing flowering climbers including pyrus japonica, jasmines, various clematis, crimson rambler, wisteria, rambling roses, honeysuckle, magnolia, prunus, and flowering almond, all planted ‘with the aim of creating a vivid living picture of the Pergola in all its Edwardian splendour’ (City of London Corporation, Citation1996, p. 9).

Since its reopening as a wholly public amenity, the site has attracted thousands of visitors. Many who visit for the first time are amazed, with one elderly woman exclaiming, ‘I was astonished to come here today. I’ve lived in London all my life and had no idea this was here’ (visitor interview, 9 August 2021). One regular visitor appositely referred to the Pergola as ‘something of a hidden gem’ (visitor interview, 16 May 2021). The Pergola’s reconfiguration as a public space hosts different social practices to those carried out in Lever’s day, responding to the affordances offered by its original design.

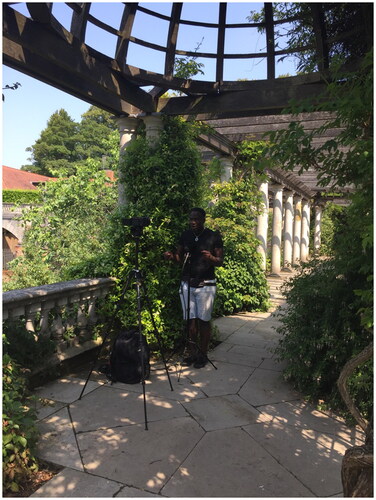

In the following discussion, I draw on 80 visits over 18 months from March 2020 until June 2022, during all seasons and on different days of the week, much of this time during the pandemic. Strolling along the Pergola, sitting down and observing people’s practices, and recording these through hundreds of photographs, I was able to identify consistent regularities after extensive perusing. In addressing the themes that have emerged for this paper, three distinctive series of images were identified: those that feature the entangling of architectural and botanical elements ( and ), representations of diverse seasonal plant growth, shadow and light along the structure (), and that captured some of the many in situ visual practices undertaken by visitors and creative practitioners, one shown here (). This immersive, extensive participant observation and photographic scrutiny was supplemented by numerous informal conversations during which visitors detailed their reasons for walking here, and their thoughts about the virtues of the Pergola and how this shaped the performance of their informal or professional activities. This was further augmented by archival research in local libraries, newspaper archives and especially the Camden Local Studies and Archive Centre in Holborn from which much historical material was obtained.

Figure 1. (a) Climbing plants wind around a pillar on the elevated north south section of the Pergola. (b) A trellised cupola adorned with foliage on the north-south section of the Pergola. (c) Old timbers thickly festooned with foliage on the western section of the Pergola.

Figure 2. (a) The immediate view upon entering the Pergola from the South in winter. (b) Entering a tented ceiling in strong summer light. (c) Turning the corner at the first change in direction to the west in summer. (d) The autumnal view from this section across to the Pergola and Gardens along which the walk has passed. (e) A further turn to the south and the approach to the ‘knuckle’ on a bright, late Spring day.

The Pergola as walking architecture

The Hampstead Pergola remains a form of landscape architecture devised for walking, designed to solicit specific ambulatory manoeuvres along its length, arouse particular ways of sensing surrounding space and foster distinctive performative conventions. I first discuss the Edwardian walking practices that were likely performed when the Pergola was part of a wholly private landscape, before detailing contemporary walking practices and experiences at the Pergola now it is part of the public realm.

Walking in Edwardian times

As Janet Waymark (Citation2009, p. 77) describes, the long walks throughout the garden of Thornton Manor near his Port Sunlight factory ‘were a reminder of Lever’s restless personality; he paced up and down similar pathways at Roynton Cottage and Hampstead’. Lever walked to expend energy and concentrate on the industrial, commercial and political strategies that subsumed him. Striding back and forth, unhindered by the presence of others, Lever could focus on the challenges to his business empire, plan building projects, landscape designs and social endeavours, and plot how to fulfil his political objectives. Aligning with broader notions that it could act as a cure for tension and restore mental and physical well-being (Wallace, Citation1993), walking acted to focus Lever’s mind. The Pergola was also a stage upon which Lever and his guests could converse while walking, exemplifying the practice of the promenade, which both ‘connotes the act of walking leisurely in a social setting’ and refers to ‘the setting for that activity’ (Jacobson, Citation2017, p. 38).

Extensive searches unearthed very limited archival evidence of the experiences of walking on The Pergola by Lever or his guests. However, historical accounts examine particular kinds of Edwardian walking practices. For instance, David Scobey (Citation1992, pp. 203–204) discusses the walking practices undertaken in mid-Nineteenth century New York by ‘the city’s propertied men and fashionable women [who] gathered in public, circulated past one another, and exchanged salutations’ performing gentility through ‘a peculiar mix of ceremony and spectacle, preening and restraint’. This promenading followed a rigorous code of conduct that performatively reinforced social status through the display of fashionable dress, disposition, comportment, gait, manners and etiquette. These reserved, genteel performances demonstrated to the lower classes ‘the manners and cultural mores that exemplified the highest ideals of an increasingly heterogeneous society, inspiring social cohesion and civic pride’ (Jacobson, Citation2017, p. 38), promenading practices they might emulate. Scobey (Citation1992, p. 215) argues that the promenade highlighted the evolution of a bourgeois public sphere in which a spectacular ‘tableau of orderly circulation’ was enacted.

However, in the late nineteenth century, a more culturally heterogeneous working class took over the processional spaces of New York and elsewhere, as ‘genteel notions of park use gave way to a more democratic recreational vision’ (Scobey, Citation1992, p. 226). Lively social conviviality, expressive playfulness, and sensuous engagements displaced more ‘respectable’ modes of public behaviour, along with more inclusive walking practices. In attempting to reinstate bourgeois distinctions, ‘genteel actors turned to other, more private institutional settings such as clubs, fraternities, and learned societies to socialise’ (Jacobson, Citation2017, p. 46). The Pergola constituted one such exclusive walking realm.

This performance of gentility is underpinned by Sarah Edwards (Citation2017, p. 16) exploration of the Edwardian summer garden party as represented through persistent literary and filmic tropes. These romantic imaginaries typically ‘feature an exotic, self-contained space which is beyond the realm of the protagonist’s ordinary experience: geographically remote, stilled in time, promising heightened adventures and sensory delights. It may be an island, wood, river and/or a country house’. The Hill House and Pergola is typical of such opulent, stable and peaceful realms, and yet imperial decline, political struggles for class and gender equality, and the looming shadow of the First World War threaten to shatter such idealised landscapes. Nonetheless, visions of ‘tea on the lawn, games of croquet and intricate social rituals’ (S. Edwards, Citation2017, p. 22) still pervade contemporary cultural imaginaries. Indeed, the City of London Corporation pamphlet about the Pergola (1996, p. 10) advises contemporary visitors that it is best ‘not to hurry your stroll along its length – instead, imagine yourself into the role of a well-to-do Edwardian, with all the time in the world to saunter and savour its delights before returning to a Leverhulme garden party’. The author counsels that ‘the return to twentieth century reality is something you may not want to rush’ (City of London Corporation, Citation1996, p. 10). Its design and setting does indeed entreat us to envision the polite conversation and genteel ambling along the tranquil Pergola by women visitors in their elegant gowns and hats and men with starched collars and suits, stopping occasionally to imbibe their drinks.

Contemporary walking

Now it is a wholly public space, the Pergola lures numerous pedestrians, drawn by the qualities that inhere in its original design, attributes that cajole pedestrians into a range of distinctive, regular practices, some that resonate with those of bourgeois Edwardian strollers.

Despite the many joggers that run across the Heath, nobody runs here. Indeed, there is rarely any speedy walking, for most pedestrians amble along, sometimes stopping to smell the flowers or gaze at the vistas afforded by its multiple vantage points. Conversation is typically muted as family groups, couples and friends slowly wander, chatting, gazing and photographing each other. This is a venue for amiable, relaxed social interaction. Many visitors rest awhile on one of the memorial benches that line the walkway, drinking coffee, hot chocolate or something stronger, chatting with companions, reading, sketching, completing crosswords, devising film plots, meditating or daydreaming. I now focus more specifically on the qualities offered by the Pergola and how these contribute to the sensory and social pleasures pedestrians experience.

The Pergola’s recurrent pillars and covering beams provide a rhythmic consistency for walkers but this is punctuated by sharp turns and striking breaks. Further, the different exits and entrances, steps, bridges and the ever-changing relationship to the ground below act to slow linear movement, producing a walking experience that combines repetition, surprise and variety. The four or five exits and entrances along its length that offer connections to the gardens and the Heath can be traversed via stairs and slopes, with some accessible to non-ambulant people. Like the medieval town of Martel depicted by Peter Blundell Jones (Citation2015, p. 2), the Pergola offers ‘an unfolding sequence of experience… progress across thresholds and through layers of fabric’, drawing pedestrians forward. Sheltered areas offer respite from wind and rain, while the benches and balustrade offer places at which to sit and lean. The walking body is thus enticed into an array of movements up and down and along the course of the walkway and a host of points of access and repose. The ‘delicious sense of enclosure’ offered by a pergola, as Katherine Swift (Citation2001, p. 85) notes, ‘beckons us to enter, to stroll, to sit, above all to linger’. This pedestrian landscape architecture repudiates the imperative for instrumental transit and encourages multiple movements and stoppages, enhancing the improvisatory capacities and sensory pleasures of visitors.

Indeed, in extending the sensory experience of a walk, the Pergola offers tactile pleasures stimulated by botanical growth and the lithic and metal materialities out of which it is wrought. For one regular visitor, a middle-aged woman, the Pergola ‘mediates between the wild and the manicured’ (visitor interview, 21 June 2020), articulating the productive tension that devolves between the planned and rigid geometry and the cascades of unruly plants that grow, bloom and wither throughout the year (see ). This botanical agency is accompanied by energies of other non-humans: the birds that nest in the thick foliage and the spiders that weave their webs across trellises, bricks and branches. The solid Portland stone balustrades are pleasing to lean upon, the even paving underfoot offers a generous bounce to the walking feet and iron gates and trellises provide an unyielding strength. The crumblier brick, individuated through processes of decay, acts as counterpoint to these smooth elements, and the timbers – some of recent vintage and sturdy, others venerable and splintery – add to the variegated material constituency.

These tactile delights are accompanied by the rich aromas that pervade the Pergola, especially during spring and summer flowering, and autumnal decay. As Swift (Citation2001, p. 85) submits, the Pergola grants ‘an open invitation to stroll and to idle away the hours in scented dalliance’. Sonic stimulations are solicited by the low chatter of others, rustling trees and mellifluous birdsong, besides the rasping corvids and mewing buzzards. The transformation of fresh spring and summer greenery into the browns and yellows of autumn and then to the skeletal arboreal forms of winter conveys ‘powerful feelings of transitoriness, movement, a sense of the fleeting moment’ (Swift, Citation2001, p. 9).

To summarise, these multiple affordances coerce moving bodies into adapting to the route, its surfaces, textures underfoot, angles and slopes offering a rich, dynamic, sensual walking experience. Most pedestrians ‘adjust their gait to the pace of the place, listening to their surroundings and extending their visual attention’ (Thomas, Citation2010, p. 61), ambling, lingering and attending to the numerous sensations. A pedestrian choreography is characterised by a shifting attunement to intensities of rain, light, shadow, smell, sound, and colour, the density of the air or the touch of the breeze. Visitors may become aware of the presence of other cross movements – rain and wind, birds and insects, plant growth and water running, and the slow decay of wood and stone, dynamic, mutable agencies in a vital, transient world. This sensuality is appositely captured by Swift (Citation2001, p. 7):

Pergolas, arbours and arches are a source of some of the most acute of all garden pleasures – the visual contrast of architectural line with twining plant, the gardenly satisfactions of plants trimly tied and trained (or wantonly trailing), the sensuous dangling of fruit or flower just within reach – but above all perhaps, of the subtle interweaving of interior and exterior

The skilfully created architectural and landscaped realm of the Pergola promotes extremely rich sensorial experiences for pedestrians that surely resonate with those of the Edwardians that once strolled along it. Yet these sensory pleasures stimulate contemporary modes of visual consumption and production that were not envisaged during these earlier times, as I now discuss.

Sceneography, films and photographs at the Pergola

The Hampstead Pergola has been sceneographically devised to produce a wealth of visual pleasures, a plethora of shifting views close at hand, in the middle distance, and towards the horizon. The movement I have discussed that shifts in and out, up and down, stopping and moving, and the multiplicity of frames this offers veers away from landscape designs in which there is a singular hierarchical viewpoint (Woudstra, Citation2015). In the foreground, climbers weave through the trellises and beams, and where climbing plants are scanty the geometric patterns of the temples frame the sky. A gaze into the middle distance discloses the gardens below, the thick foliage of trees and the rectilinear zigzag of the Pergola. Views beyond the trees are few but are thereby rendered more dramatic. As Swift (Citation2001, p. 85) contends, the view of Harrow-on-the Hill is a startling surprise, a ‘magnificent coup de theatre’. Indeed, local tree manager, David Humphries, informed me that this is one of several privileged views that the Heath’s landscape managers must retain through tree pruning.

Critically, as Paul Edwards (Citation2001, p. 111) emphasises, ‘a Pergola directs the eye and frames the view’. Views outwards are framed by pillars, balustrades and overarching timbers, often fringed with branches and leaves. A rest upon the balustrade affords scrutiny of the gardens; a pause on the bridge reveals pedestrians on the public path below. The view ahead reveals a succession of twists and turns, steps, cupolas and arches, and focuses attention on fellow promenaders as they move away or towards the beholder. A further compelling visual effect of the beams, trellises and pillars, especially in bright sunlight, is that they generate extraordinary patterns of shadow and light across surfaces (see ).

This medley of views accords with Victorian and Edwardian sceneographic endeavours to develop panoramic views of landscapes, seas, skies, coastlines and horizons from belvederes, piers and promenades. While such optical practices might suggest a detached gaze redolent of Cartesian perspectivalism, Joslin McKinney (Citation2018) contrasts this with a baroque vision that continuously shifts between a proliferation of objects near and far. It is this latter visual practice, an intensified, immersive engagement open to landscape rather than separate from it, that is solicited by the Pergola (Wylie, Citation2005). Thomas Mawson skilfully manipulated colour, light, materiality and pattern to create a complex, theatrical and visually arresting landscape. Yet these sceneographic qualities have generated abundant photographic and filmic practices that neither Lever and Mawson could have envisaged.

These practices resonate with the contemporary centrality of images to place-making, especially where enticing images of iconic architectures are deployed to attract visitors (Koeck, Citation2012). Such images are enrolled into processes of regeneration and economic growth (Roberts, Citation2012), contributing to an urban imaginary saturated with tourist destinations and heritage sites. Yet while local authority promotion of place through marketing potential film locations seek commercial opportunities, filmic representations coexist with vernacular visual practices at the Pergola, where fashion shoots, pop videos, filmed poetry readings and wedding photography are extremely prevalent, and often transmitted via social media. As the making of still and moving images via digital cameras becomes progressively entangled with everyday practices, photography becomes embedded in the multisensorial experience of place as part of an ‘emplaced visuality’ (Pink & Hjorth, 2014). Indeed, Mosconi et al. (Citation2017, p. 962) insist that image making is often a local practice that enhances ‘the capacity of social media to bring neighbours closer together, create closer ties, and increase civic engagement’. It is also a profoundly place-making practice; as photographs and films of certain sites proliferate, luring others to make their own images (Edensor & Mundell, Citation2021).

With its sceneographic qualities and plethora of alluring sites, the Pergola has become an exemplary stage upon which to pose in front of the camera. Its lateral, vertical and elongated perspectives offer a multitude of frames – and frames within frames – while its elevated position allows photographic subjects to be positioned against a verdant backdrop. The linear pathway, garlanded with flowers and leaves, encourages the photographing of individuals or couples walking towards the camera. And the open-ended architecture offers soft or geometric light to bathe photographic subjects from above and from the side.

This wealth of photographic practices includes selfies and individual and group photographs. Many images are akin to the tourist photographs that involve carefully chosen backdrops and playful performative arrangements (Larsen, Citation2005). Many are posted on social media platforms for a larger audience (on Instagram, the hashtag ‘Hampstead Pergola has been used nearly three thousand times). Other practices are more ‘professional’, with fashion shoots selecting different settings in which to photograph models. Similarly, photographs intended to supplement the portfolios of musical performers, models and actors variously position their subjects between pillars, leaning on balustrades, partially covered by foliage, posing along walkways.

Most extensively, the Pergola is a stage for commemorative wedding photographs, predominantly of South Asian couples. On most summer days, newlyweds or those about to be married, finely dressed and coiffed, adopt lengthy sequences of poses for professional photographers that usually excise the presence of others. These intimate compositions characteristically involve the couple walking along extended sections of pathway, wistfully gazing upwards or outwards while leaning upon the balustrade or sitting together on a bench. These idealised romantic images are supercharged by their evocative location, as articulated by wedding photographers who advertise their services on the internet. Bhavesh Chauhan (Citationn.d.) exclaims, ‘I love this location because it has such charm, presence and architecture – a photographers dream!’, while Amanda Karen (Citationn.d.) deems that ‘the pillars and architecture was just perfect for this elegant engagement shoot, creating a romantic yet grand sense of style’. Maria Assia (Citationn.d.) considers that the Pergola has ‘a luxurious and intimate feel to it… is elegant in its design and architecture and is full of rundown splendour’.

The Pergola has also become a well-used location for diverse video and cinematic projects. This exemplifies Giuliana Bruno’s (Citation1997) contention that modern walking experiences produce synergies between physical movement and cinematic filming and viewing. She proclaims that coterminous with the advent of cinema, a profusion of spaces of transit, including ‘arcades, railways, department stores, and exhibition halls’ formed a new mobile geography of modernity. Bruno argues that by ‘changing the relation between spatial perception and bodily motion’ such architectures ‘prepared the ground for the invention of the moving image - an outcome of the age of travel culture and the very epitome of modernity’ (Bruno, Citation1997, p. 9). Here, ‘the architectural promenade, like the cinema, is a medium for experiencing multiple, changing views borne through mobility, the moving camera and the pedestrian in motion both connecting spaces together as sequence of visual impressions’ (Bruno, Citation1997, 19). The plethora of framings experienced during a walk along the Pergola, though not created with image-making in mind, have become framing devices for filming.

The Pergola is often selected by film students and frequently, as a venue at which to shoot music videos, as was evident on one July afternoon in 2021 as directors shot footage of pan-European rock band, The Gulps, in many areas of the structure. Similar video performances were filmed for a rap artist (November 2021) and an Asian pop star (February 2021). One July morning, charismatic motivational speaker Ralph Smart (Citation2021) performed one of his regular YouTube videos, termed New Earth Is Already Here. Prepare Yourself for the 5th Dimension! He commences by referring to his surroundings, announcing that ‘we’re in like, a paradise now deep divers’, the ‘new age’ term for his followers whom he encourages to advance their self-development (see ).

The Pergola served as a setting for ‘Joystick Generation’, episode 3 of a 2009 Channel 4 documentary series, Games Britannia, presented by Benjamin Woolley (Citation2009), that explores the emergence of video gaming. The episode features the presenter wandering down the Pergola, its long series of frames acting as an unspoken metaphor for the sequential pathways down which Lara Croft, heroine of the hugely popular Tomb Raider video game travels, a series of stages that the player, as Lara, has to overcome. Woolley explains that with the advance of digital techniques, such games can now ‘plunge the viewer into a glorious, lush world of exotic locations’, simulations that resonate with the lavish surrounds of the Pergola. This is followed by an animated sequence in which Lara travels down a verdant linear walkway lined with columns that makes these visual resonances explicit.

By contrast, in Melanie Gilligan’s Citation2008 political art film, Crisis in the Credit System, the Pergola is the location for a farcical role-playing seminar in which employees at an investment banking company explore potential responses and solutions to the threatening financial climate. Contrastingly, major feature film The Danish Girl (2015), directed by Tom Hooper, focuses on the 1920s pioneering gender reassignment surgery of Einar, subsequently Gerda Wegener, played by Eddie Redmayne. The Pergola serves as a formal garden through which Gerda walks, recuperating after her first surgical operation, and while most of the sequence is filmed from a single point, at one point the camera pans out to reveal a digitally altered riverine landscape that supplants the oaks and beeches that clothe Hampstead Heath. Judy (2019), directed by Rupert Goold and starring Rene Zellweger as American movie icon Judy Garland in the twilight of her life, also includes a brief autumnal scene in which Judy walks along the Pergola with Mickey, her husband to be.

Rethinking walking architectures; amplifying imageability

As the City of London Corporation publication asserts (1996, p. 5), though conceived as a private Edwardian project, ‘the Pergola’s influence was far-reaching’. In this paper, I have challenged limited understandings about pedestrian provision by foregrounding how the Pergola, a hundred-year-old form of landscape architecture, affords highly pleasurable walking experiences that diverge from the functional and commercial imperatives that so often dominate designs and planning for pedestrians. I suggest that it retains its potency and acts an exemplar for more creatively expanding pedestrian experience in cities. While linear in form, the Pergola invites diverse movements along its route, diverse places to sit or rest, and the adoption of divergent rhythms and paces. Lingering is not regarded as suspicious but encouraged by the looser temporal conventions that guide spatial practice (Edensor & Millington, Citation2018). Elsewhere, such unhurried practices may be conceived as frivolous, unproductive and inimical to public order, with loitering discouraged within urban agendas of ‘surveillance, regulation, privatisation and sanitization’ (Rishbeth & Rogaly, Citation2018). Moreover, the Pergola offers an inclusive realm in which people may relax, socialise, absorb surroundings and create. They may rest, converse and dream. Its mix of botanical effusion and formal structure, diverse material affordances and various prompts to movement engender highly stimulating sensory experiences throughout the year.

I have underlined that the design of the Pergola succeeds as walking landscape architecture because its skilful, multiple production of numerous frames afford multiple visual delights. These diversions have made the site extraordinarily popular as a contemporary venue at which to creatively produce photographic and filmic images. In an era of social media in which the dissemination of memorable images can broadcast powerful place-images, such visual qualities seem especially valuable. Here, besides the professional images produced for feature films, pop videos and commercial wedding photography, numerous unofficial and vernacular practices make and disseminate images of the site, broadcasting the virtues of the Pergola. They also connect people to the wider landscape through which pedestrian routes pass and offers an example of how these might be more inventively framed, capitalising on Giuliana Bruno’s (Citation1997) identification of the resonances between walking and the modern experience and production of visual images.

The increased walking solicited by the COVID-19 pandemic has promoted a new awareness about the values of walking that city manager and planners must address. In this context, the attributes of the Pergola exemplify how pedestrian pleasures might be more assiduously promoted in cities, especially in an era in which walking is increasingly recognised as conducive to well-being, an antidote to obesity and poor mental health, and integral to place belonging. Landscape architects, urban planners and city managers would do well to learn from the Pergola in designing structures solely designed to facilitate walking; indeed, it seems imperative to enhance urban walking experiences as future car use dwindles and alternative means for enlivening the city are demanded. The Pergola exemplifies how enticing, enduring and innovative designs for walking can be devised that foster urban sociability, enhance sensory experience and advance the imageability of the city through skilful framing.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the many folks with whom I have walked along the Hampstead Pergola.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tim Edensor

Tim Edensor is Professor of Social and Cultural Geography at the Institute of Place Management, Manchester Metropolitan University. He is the author of Tourists at the Taj (1998), National Identity, Popular Culture and Everyday Life (2002), Industrial Ruins: Space, Aesthetics and Materiality (2005), From Light to Dark: Daylight, Illumination and Gloom (2017) and Stone: Stories of Urban Materiality (2020). and. He is editor of Geographies of Rhythm (2010), and co-editor of The Routledge Handbook of Place (2020), Rethinking Darkness: Cultures, Histories, Practices (2020) and Weather: Spaces, Mobilities and Affects (2020). His most recent publication is Landscape, Materiality and Heritage: An Object Biography (2022), a book about a Scottish medieval cross.

References

- Assia, M. (n.d.). Maria Assia. Retrieved from https://mariaassia.com/luxuriously-intimate-hampstead-Pergola-pre-wedding-shoot/.

- Beard, G., & Wardman, J. (1978). Thomas H. Mawson, 1861–1933: The life and work of a northern landscape architect. Lancaster: University of Lancaster, Visual Arts Centre.

- Blundell Jones, P. (2015). Introduction: Architecture and the experience of movement. In P. Blundell Jones & M. Meagher (Eds.), Architecture and movement: The dynamic experience of buildings and landscapes (pp. 1–7). London: Routledge.

- Bruno, G. (1997). Site-seeing: Architecture and the moving image. Wide Angle, 19(4), 8–24. doi:10.1353/wan.1997.0017

- Chauhan, B. (n.d.). Bavesh Chauhan Photography. Retrieved from https://bhaveshchauhanphotography.co.uk/pre-wed-shoot/Pergola-and-hill-gardens-london/.

- City of London Corporation. (1996). The Pergola: The birth, decline and spectacular renaissance of a unique Edwardian extravaganza. London: City of London Corporation.

- Claydon, A. (2001). Pergolas of today and tomorrow. In P. Edwards & K. Swift (Ed.), Pergolas, arbours and arches (pp. 66–73). London: Barn Elms.

- Conlin, J. (2008). Vauxhall on the boulevard: Pleasure gardens in London and Paris, 1764–1784. Urban History, 35(1), 24–47. doi:10.1017/S0963926807005160

- Degen, M., & Rose, G. (2012). The sensory experiencing of urban design: The role of walking and perceptual memory. Urban Studies, 49(15), 3271–3287. doi:10.1177/0042098012440463

- Edensor, T. (2000). Walking in the British countryside: Reflexivity, embodied practices and ways to escape. Body & Society, 6(3-4), 81–106. doi:10.1177/1357034X00006003005

- Edensor, T. (2010). Walking in rhythms: Place, regulation, style and the flow of experience. Visual Studies, 25(1), 69–79. doi:10.1080/14725861003606902

- Edensor, T., & Millington, S. (2018). Learning from Blackpool promenade: Re-enchanting sterile streets. The Sociological Review, 66(5), 1017–1035. doi:10.1177/0038026118771813

- Edensor, T., & Mundell, M. (2021). Enigmatic objects and playful provocations: The mysterious case of Golden Head. Social & Cultural Geography, 1–21. doi:10.1080/14649365.2021.1977994

- Edwards, P. (2001). Elements of design. In P. Edwards & K. Swift (Ed.), Pergolas, arbours and arches (pp. 111–121). London: Barn Elms.

- Edwards, S. (2017). Dawn of the new age: Edwardian and neo-Edwardian summer. In S. Shaw, S. Shaw, & N. Carle (Eds.), Edwardian culture: Beyond the garden party (pp. 15–30). London: Routledge.

- Gilligan, M. (2008). Crisis in the credit system. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qnMYwUz0WVY.

- Historic England. (n.d.). Rivington gardens listing. Retrieved from https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1000950.

- Jacobson, W. (2017). The Nineteenth Century American promenade. Precedent and form. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy, 2(4), 37–62.

- Julier, G. (2005). Urban designscapes and the production of aesthetic consent. Urban Studies, 42(5–6), 869–887. doi:10.1080/00420980500107474

- Karen, A. (n.d.). Amanda Karen Photography. Retrieved from https://www.amandakarenphotography.co.uk/about-fine-art-essex-wedding-photography/.

- Koeck, R. (2012). Cine-scapes: Cinematic spaces in architecture and cities. London: Routledge.

- Larsen, J. (2005). Families seen sightseeing: Performativity of tourist photography. Space and Culture, 8(4), 416–434. doi:10.1177/1206331205279354

- Lazarro, C. (1990). The Italian renaissance garden. London: Yale University Press.

- McKinney, J. (2018). Seeing scenography: Scopic regimes and the body of the spectator. In A. Aronson (Ed.), The Routledge companion to scenography (pp. 102–118). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Mawson, T. (1912). The art and craft of garden making. London: B. T. Batsford.

- Mawson, T. (1927). The life and work of an English architect. Manchester: Percy Brothers.

- Mosconi, G., Korn, M., Reuter, C., Tolmie, P., Teli, M., & Pipek, V. (2017). From Facebook to the neighbourhood: Infrastructuring of hybrid community engagement. Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW), 26(4–6), 959–1003. doi:10.1007/s10606-017-9291-z

- Pink, S., & Hjorth, L. (2012). Emplaced cartographies: Reconceptualising camera phone practices in an age of locative media. Media International Australia, 145(1), 145–155. doi:10.1177/1329878X1214500116

- Rishbeth, C., & Rogaly, B. (2018). Sitting outside: Conviviality, self-care and the design of benches in urban public space. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 43(2), 284–298. doi:10.1111/tran.12212

- Roberts, L. (2012). Film, mobility and urban space: A cinematic geography of Liverpool. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Scobey, D. (1992). Anatomy of the promenade: The politics of bourgeois sociability in Nineteenth-Century New York. Social History, 17(2), 203–227. doi:10.1080/03071029208567835

- Sanders-McDonagh, E., Peyrefitte, M., & Ryalls, M. (2016). Sanitizing the city: Exploring hegemonic gentrification in London’s Soho. Sociological Research Online, 21(3), 128–133. doi:10.5153/sro.4004

- Sennett, R. (1994). Flesh and stone. London: Faber.

- Smart, R. (2021). New earth is already here. Prepare yourself for the 5th dimension! Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LDgpq_fPGl0&t=51s.

- Swift, K. (2001). Introduction. In P. Edwards & K. Swift (Ed.), Pergolas, arbours and arches (pp. 7–9). London: Barn Elms.

- Swift, K. (2001). The hill. In P. Edwards & K. Swift (Ed.), Pergolas, arbours and arches (pp. 84–89). London: Barn Elms.

- Thomas, R. (2010). Architectural and urban atmospheres: Shaping the way we walk in town. In R. Methorst, H. Monterde, R. Risser, D. Sauter, M. Tight, & J. Walker (Eds.), Pedestrians’ quality needs. Final report of the COST project, 358 (pp. 54–68). Brussels: European Cooperation in Science and Technology (COST).

- Wallace, A. (1993). Walking, literature and English culture. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Waymark, J. (2009). Thomas Mawson: Life, gardens and landscapes. London: Frances Lincoln.

- Woolley, B. (2009). Joystick generation. Games Britannia. Retrieved from https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x4tatxc, 21.04 -22.37

- Woudstra, P. (2015). From health to pleasure: The landscape of walking. In P. Blundell Jones & M. Meagher (Eds.), Architecture and movement: The dynamic experience of buildings and landscapes (pp. 102–111). London: Routledge.

- Wylie, J. (2005). A single day’s walking: Narrating self and landscape on the South West Coast Path. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 30(2), 234–247. doi:10.1111/j.1475-5661.2005.00163.x