Abstract

This article examines differences between landscapes and nightscapes, i.e. how what we encounter in daylight conditions differs considerably from what we encounter in the dark. I explore what landscape is and how it works, followed by examining how it and how it works is negated by darkness, only to be re-established through illumination. The purpose of this article is to illustrate how nightscapes are, in fact, superior to landscapes in terms of channelling people’s desires. While darkness prevents the abstract machine of landscape from functioning, illumination returns it to action, providing those with the necessary capital the opportunity to influence people and shape their identities. Nightscapes do, however, provide opportunities to anyone who wishes to express oneself by utilising the illumination provided by others for their own purposes and, at times, against the others.

Introduction

While there is no shortage of excellent landscape research, most studies tend to take daylight conditions for granted. As a result, the number of studies on nightscapes is, at best, limited. The purpose of this article is therefore to contribute to this tradition by illustrating the differences between landscapes and nightscapes through a post-structuralist framework.

The study of nightscapes is by no means exclusive to geographers, but they are arguably the ones most dedicated to it. Tim Edensor’s (Citation2015, Citation2017a, Citation2022) work on how people experience nightscapes is particularly noteworthy. He has also collaborated with others, focussing on experiencing nightscapes (Cook & Edensor, Citation2017), as well as on their design and related socioeconomic factors (Edensor & Millington, Citation2013). Others have also focussed on how they are experienced (Ebbensgaard, Citation2015; Morhayim, Citation2018; Sumartojo, Citation2020). For some, their interest lies in the history of nightscapes (Jakle, Citation2001) or in their intertwining with authenticity (Pottie-Sherman & Hiebert, Citation2015), economy (Chatterton & Hollands, Citation2003; Nofre, Citation2013), governance (Hadfield & Measham, Citation2015; Shaw, Citation2015), planning (Gallan, Citation2015), sexuality (Boyd, Citation2010), and security (Brands, Schwanen, & van Aalst, Citation2015; Yeo, Citation2020). My focus is similar to Williams (Citation2008) as I am interested in how nightscapes function to channel people’s desires to produce certain kinds of subjects.

I acknowledge that previous post-structuralist landscape studies tend to disregard changing lighting conditions, as commented by Edensor (Citation2017a). I therefore seek to fill a gap in the research literature. I am also aware of how these studies do not take into account how landscapes are experienced, as indicated by Edensor (Citation2017b). While I find value in studies that focus on the subject, I am interested in what Guattari (Citation1995) refers to as the machinic production of subjectivity. Our affective encounters with landscapes are certainly important, but, in my view, we always experience the world through a socially shared sign system, as argued by Voloshinov (Citation1973) and Wetherell (Citation2015). I subscribe to a mode of thought in which semiotic expressions are not descriptive, nor representative, but affective or non-representative, as presented by Guattari (Citation2013). However, as most people subscribe to a representational mode of thought, being driven by signification and subjectification, they tend to pigeonhole themselves and others, semiotically enslaving one another according to societally valued categories (Guattari, Citation2016), which is why I must take that into account, regardless of my own preference, as argued by Guattari (Citation2009).

I have chosen to exemplify the framework with the Turku Market Square (TMS) located in Turku, Finland, for two reasons. Firstly, the area is undergoing major renovations ‘in order to offer a cosy and a living meeting place in the heart of the city centre for everybody’ (City of Turku, Citation2021). My interest lies in investigating whether the TMS will become as communal and inclusive as the city claims. In other words, I am interested in examining whether people will have the right to the city, to not only visit it or commute through it, but also to change it in order to change themselves (Harvey, Citation2008; Lefebvre, Citation1996), or will the downtown become a landscape of privilege and exclusivity that provides standardised brand experiences to wealthy people (Chatterton & Hollands, Citation2003). Secondly, using photos of the landscape allows me to contrast the situation before and after the work has been completed. and illustrate the architects’ vision of the future landscape.

Figure 1. Schauman & Nordgren Architects’ vision of the Turku Market Square (as seen on Kauppiaskatu). Source: Photograph taken by author.

Figure 2. Schauman & Nordgren Architects’ vision of TMS (as seen on Kauppiaskatu). Photograph taken by author.

The comparison will be particularly interesting as the renovation plans included replacing the existing floodlights with more atmospheric and diffuse lighting solutions (City of Turku, Citation2020). Moreover, this is aspect is particularly noteworthy as the night-time illustrations are markedly devoid of illuminated advertising signage (City of Turku, Citation2020). This article is, however, limited to analysing the TMS in its unfinished form, contrasting channelling of desires in daylight and night-time conditions (Williams, Citation2008).

Following this introduction, this article consists of six sections and a conclusion. The conceptual framework is introduced in the following section: ‘Writing the rules’. It elaborates how space is conceived as landscape according to Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1987). It is followed by a re-evaluation of the framework in the next two sections, ‘Rewriting the rules’ and ‘Breaking the rules’, addressing the role of light and its relative absence. ‘Exemplifying the rules’ moves the discussion from theory to practice. The last two sections, ‘Night and day’ and ‘Guerrilla tactics’, explicate the shift from daylight to night-time conditions and how it modifies channelling of desires.

Writing the rules

To begin with, it is worth noting that while similar to it, the Deleuzo-Guattarian framework presented in this article goes beyond Lefebvre’s (Citation1991) spatial triad. In short, while Lefebvre correctly diagnoses how space is socially produced, typically through representation, signification and subjectification, he is unable to provide a way of out, unlike Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1987) who treat these processes as pertaining to only some, but not all sign regimes.

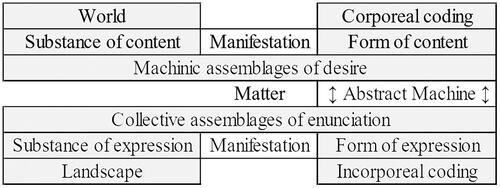

To me, landscape is an abstract machine that defines how actual landscapes are produced for us to see by concrete assemblages. My definition is based on Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1987), who, in turn, base their definition primarily on Hjelmslev’s (Citation1953, Citation1954) understanding of the world as one matter undergoing continuous transformation, as illustrated in .

illustrates Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1987) view of this transformation. Form defines the composition or formalisation of matter, i.e. how it is formed into substance, first on the (material) plane of content and then on the (semiotic) plane of expression. Moreover, as matter appears to us as substance, as formed matter, form is tied to it, appearing to us as manifested in substance, as opposed to having existence separate from matter. The concrete assemblages effectuate the abstract machine, but it is the abstract machine, connected to both (material) content and (semiotic) expression, that acts as the immanent cause to how the concrete assemblages form and deform matter, how they regulate the flows of (material) content and (semiotic) expression, configuring them into substances and forms of content and expression, by defining the rules of the transformation process.

Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1987) rely on Hjelmslev (Citation1953, Citation1954) instead of Saussure (Citation1959) to avoid what Lefebvre (Citation1996) sought to, but was unable to avoid: being trapped in signifying language. Signification is highly important, as well as highly problematic, but it is only one sign regime, among others. As explained by Guattari (Citation1984, Citation2016), Hjelmslev’s distinction between content and expression provides a way out of the despotism of the signifier, in which matter is thought to be reducible to a signifying substance. Their formulation therefore prevents semiotics from being reduced to semiology, which, in turn, prevents the material reality, and all that is affective, from being reduced into a mental reality, i.e. into a representation of itself.

In Hjelmslev’s (Citation1953) terms, an abstract machine is the function of two solidary functives that presuppose one another, the form of content and the form of expression, without which there would be no distinction between content and expression. Moreover, unlike assemblages, these machines are abstract as they are not material, nor semiotic (Guattari, Citation2016). They link forms of content and forms of expression as their end points, indicating possible crystallisations between the two forms, between what one may also refer to as the regimes of bodies (states of things) and the regimes of signs (states of signs) (Guattari, Citation2016). Simply put, they produce a machinic sense (Guattari, Citation2011), establishing how we make sense of the world pragmatically, with or without recourse to signification (Guattari, Citation1984; Voloshinov, Citation1973).

To further clarify , landscapes are (semiotic) substances of expression, the products of the abstract machine of landscape, as produced by the concrete assemblages (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1987). It is worth emphasising that landscapes are mere surfaces that overlay the (material) substances of content, which encompass the whole world (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1987). Landscapes are therefore not material entities, already there, waiting to be discovered, nor mere figments of our imagination, i.e. representations of the material world. Instead, landscapes appear to us pragmatically when the corporeal world is transformed incorporeally, without physical alterations, without penetrating the surface, with only superficial alterations, at its outer boundary (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1987).

As identified by Cosgrove (Citation1985), landscape is a Renaissance invention that came to being under a capitalist regime of signs that constitutes a signifying (Duncan, Citation1990) and subjectifying semiotic system (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1987; Guattari, Citation2011). This regime mixes a despotic and paranoid desire for an objective linguistic meaning and an authoritarian and passional desire to promote one’s own subjectivity, which results in a sticky mixture of representation (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1987). In other words, the plane of content, i.e. the material world, is reduced on the semiotic plane of expression to a signifying screen, to a mere linguistic or semiological surface (Guattari, Citation2011). Moreover, in this regime, subjectivity, i.e. one’s sense of self, is reduced to a black hole, which draws in and consumes various points of subjectification on that screen (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1987; Guattari, Citation2011, Citation2016).

Landscapes are produced in this mixed regime as standard reference units according to which one either conforms to or deviates from them (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1987; Guattari, Citation2011). To be more specific, the abstract machine indexes despotic signifiers, i.e. societally valued identity bearing words (Bracher, Citation1993), as signifying traits to certain landscape traits, i.e. to the various material elements in a landscape (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1987; Guattari, Citation2011). These signifying landscape traits then function as purportedly ideal or normal points of subjectification that one is expected to consume (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1987; Guattari, Citation2011). This results in a doubling of subjectivity; one is simultaneously both the master of and the slave to one’s own reasoning, legislating what one ought to be, according to set norms, while also feeling the pressure to conform to such ideals, being what one is not and not being what one is at the same time (Deleuze, Citation2004; Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1987).

In short, landscapes indicate what is considered desirable in a society. They manifest socially desirable identities that one is expected to identify with in order to be accepted as a member of that society (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1987; Guattari, Citation1984). They therefore serve as detectors of any supposedly aberrant behaviour, which, in turn, creates a warrant to normalise that behaviour (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1987; Guattari, Citation2011).

Existing landscape studies exemplify how this process works to (re)produce certain kinds of supposedly normal identities, pertaining to both property and propriety. In nightscape studies, these identities have been indicated as pertaining to socioeconomic class (Chatterton & Hollands, Citation2003), race (Farrer, Citation2011), sexuality (Boyd, Citation2010), nationality (Nofre, Citation2011), and religion (Talebian & Riza, Citation2020).

Due to their normativity, the problem with landscapes is that they tend to be taken for granted, as noted by Lewis (Citation1979). It is not impossible to think otherwise, but it is very difficult to do so. Once an abstract machine springs into action, it is hard to imagine as if it were not the case, has not always been the case and will not always be the case (Guattari, Citation1995, Citation2011). As landscapes provide people with a sense of normalcy, establishing who they are, now and in the future (Guattari, Citation2011; Rose, Citation2006; Wodiczko, Citation1999), they reinforce the status quo (Howard, Citation2011). It is this givenness that explains their effectiveness in detecting any supposed deviance and subsequently normalising it (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1987; Guattari, Citation2011; Mitchell, Citation2002). It is therefore only apt that Guattari (Citation2016, p. 40) mentions them as ‘perhaps the most underhand allies of dominant systems of signification’.

It is, nonetheless, possible to prevent this semiotic enslavement involving landscapes. All one needs to do is to rewrite the rules of the transformation process illustrated in . Nightscapes provide a perfect opportunity for such an intervention, which will be addressed in the following section.

Rewriting the rules

As an abstract machine, landscape defines the rules according to which the assemblages construct the world, how it appears to us, but it also depends on them, as noted in the previous section. According to Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1987), the concrete assemblages have two sides, which operate on the two planes, as illustrated in .

Firstly, on the content plane, the assemblages are machinic assemblages of desire. They regulate and segment content, dividing it to substance of content and form of content. Moreover, they organise how corporeal bodies are arranged in relation to one another, both inorganically and organically, as regimes of bodies or visibilities (physical systems of affects, of actions and passions) (Deleuze, Citation1988; Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1987), which, in turn, condition what can and cannot be seen (Bogue, Citation2009).

Secondly, on the expression plane, the assemblages are collective assemblages of enunciation. They regulate and segment expression, dividing it to substance of expression and form of expression. Furthermore, they organise how incorporeal anthropomorphic signs are arranged in relation to one another semiotically, as regimes of signs or statements (semiotic systems of indexes, icons and symbols) (Deleuze, Citation1988; Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1987), which, in turn, condition how those bodies or visibilities are transformed incorporeally, defining how we come to make sense of them pragmatically (Deleuze, Citation1990; Guattari, Citation1984, Citation2011).

These two regimes are connected, coordinated and coadapted by the assemblages and the abstract machines, constantly interfering with one another, but they remain distinct from and irreducible to one another (Deleuze, Citation1988; Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1987). It is the interference of the visibilities that is of particular interest here as the abstract machine of landscape depends on a certain physical system, which in this case is daylight conditions. Simply put, lack of light, i.e. darkness, disrupts the abstract machine, preventing it from functioning. It results in what Guattari (Citation2013, p. 249) refers to as ‘an autonomous, abyssally fractalized gaze’, by which he means that we are no longer able to comprehend what we see as a totality and that our interpretation of what we see is prevented from reaching a closure. In other words, summarising Sumartojo (Citation2020), as our visual acuity decreases, as we can no longer distinguish anthropomorphic signs at a distance, our senses are recalibrated to a degree that we can no longer make sense of the world through signification, which also prevents subjectification through signifying landscape traits.

Darkness interferes with the abstract machine of landscape to an extent that it poses a problem to the reigning western socio-semiotic order. According to Edensor (Citation2013, Citation2015) and Schivelbusch (Citation1988), night has typically been considered chaotic, unleashing in the dark all that is Dionysian, whereas day has been considered orderly, shining with light, bringing Apollonian order to the world, and the closer we get to modernity, the more authorities have sought to regulate the night through illumination. As explained by Foucault (Citation1980, p. 154), darkness prevents ‘subjection by “illumination”’, i.e. the production of socially desired bodies, and, conversely, facilitates the production of diverse, yet socially undesirable or deviant identities, which is why it is generally considered a necessity to counter it. The taken for granted, seemingly rational order of things is at stake, hence the urgency to curtail its transgressive or, rather, transversal potential, as aptly summarised by Williams (Citation2008). Consequently, people have become so accustomed to light that its omnipresence is taken for granted even at night time, as noted by Schulte-Römer (Citation2022).

It is virtually impossible to establish daylight conditions at night-time, as discussed by Schivelbusch (Citation1988). Darkness is therefore generally countered only to a certain extent, by, for example, illuminating roads and buildings. The response is thus strategic (Cresswell, Citation1998; Williams, Citation2008). Moreover, this problem posed by darkness also provides other strategic opportunities, which do not present themselves in daylight conditions. What is important is not the light or illumination itself, but what it affords (Ebbensgaard, Citation2019). Landscapes can be so crowded with various elements that our perception of them is hampered by the overwhelming amount of visual information presented to us (Herzog, Sayim, Chicherov, & Manassi, Citation2015). Darkness renders the elements similar, reducing crowding, which, in turn, helps any illuminated elements to stand out in the nightscape, inasmuch as the nightscape does not, of course, become crowded with them (Edensor, Citation2017a; Edensor & Bille, Citation2019). In other words, those who have the resources to illuminate the nightscape do not have to compete for people’s attention as they would under daylight conditions (Edensor, Citation2017a; Williams, Citation2008). This presents an opportunity to reorder what we see, to better serve corporate interests (Williams, Citation2008).

Illumination of nightscape elements allows those with the necessary resources to channel desires, reconfiguring people as machinic assemblages of desire; ‘[t]he brighter the lights or the more vivid the hues, the better to attract potential customers’ (Williams, Citation2008, p. 522). People are constantly reminded of the existence of brands through signifying nightscape traits, while darkness limits people’s opportunities to influence their surroundings (Williams, Citation2008). It is worth clarifying that desire pertains to the production of reality, how bodies affect one another, and its channelling pertains to how desires can be semiotically shifted from being productive and open-ended to being anti-productive and closed-ended beliefs, treating them not as positive, as affirmations, but as negative, as lacks, recasting them as something that must be achieved or fulfilled (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1983, Citation1987). People are therefore driven to consume, to identify themselves with despotic signifiers that provide them stable identities that are, nonetheless, merely illusory (Bracher, Citation1993), as any word, any signifier, only ever refers to other words, to other signifiers, ad infinitum, in a signifying regime of signs (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1987).

While it appears that only those with the necessary capital can seize upon this opportunity to change the rules and to channel people’s desires, it is not, however, strictly speaking the case. As explained by Foucault (Citation1978), wherever you find an exercise of power, you will also find resistance to it as resistance is always inscribed in power as its irreducible opposite. This strategic opportunity to reappropriate the nightscape is further discussed in the following section.

Breaking the rules

Graffiti is a common way of expressing oneself in an urban environment. Most graffiti consist of simple tags, i.e. stylised signatures, as all you need is a marker or a spray can, whereas the more elaborate and large graffiti can only be produced by experienced artists, often working with one another (Christen, Citation2010). While graffiti is often depicted in negative terms, as anti-social behaviour, as deviance or as a problem to solve, in positive terms, it is a way to express oneself and, more importantly, to imagine, map, use, mediate and make urban space (Iveson, Citation2010). It is therefore not only about the expression, but also about the right to express oneself and the right to participate in the society (Harvey, Citation2008; Lefebvre, Citation1996).

While darkness challenges the existing social order that abhors it, it is also possible to challenge the status quo by means provided by the status quo, i.e. through the tactical reappropriation of illumination, as argued by Wodiczko (Citation1999). Dery (Citation2017) refers to one of the tactics as guerrilla semiotics. In the context of nightscapes, the idea is not to destroy illuminated nightscape elements, such as hoardings, but to alter them (Cresswell, Citation1998). This involves changing existing signifying nightscape traits in order to signify something that is deemed to be undesirable instead of something desirable (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1987; Guattari, Citation2011), to make it apparent that messages are not value neutral (Cresswell, Citation1998). The goal is therefore to subvert the original message, to make it clear to passers-by that it is not merely informative, to emphasise that the message seeks to channel desires (Williams, Citation2008), compelling people to act in a certain way, to consume certain points of subjectification (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1987), for example products or services, in order ‘to feel good about themselves’ (Bracher, Citation1993, p. 24), to reassure themselves that they know who they are and what kind of world they belong to, even if only for a moment (Rose, Citation2006).

Next, I will summarise the conceptual framework in the following section. The purpose of this section is to bridge gap between theory and practice, to explain how the framework is used in the analysis in the following two sections: ‘Night and day’ and ‘Guerrilla tactics’.

Exemplifying the rules

As I am interested in the production of subjectivity through nightscapes, I rely on what Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1987) refer to as schizoanalysis, which is the practical and political analysis of desire that does not start from the subject, but from the lineaments that run through individuals, groups and societies. I am therefore tasked to map people’s desires and how they can be channelled, even in ways that can make people desire their own repression (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1983, Citation1987), in order to understand how what is considered given is given (Deleuze, Citation1994; Guattari, Citation2013). In practice, this means that I am tasked to address the abstract machine, to understand how it functions, and the assemblages that produce the substances and the forms of content and expression, as conceived by us as regimes of bodies and signs, respectively (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1987; Guattari, Citation2013). In this article the focus is on the nightscape and its various elements, the signifying traits, as well as on the regimes that govern them in this specific context.

Among landscape scholars, this kind of approach may seem unfamiliar and unorthodox, not to mention dauntingly complex. It is, however, the approach promoted by Schein (Citation2009), albeit in a Foucauldian guise. In summary, one focuses on what is seen, i.e. the non-discursive landscape, and what is said about the landscape, i.e. the discursive context of the landscape, in order to understand how the latter comes to be materialised in former (Schein, Citation2009). In other words, to reiterate a point from an earlier section, ‘Writing the rules’, a semiotic form always appears to us pragmatically, as manifested or incarnated in a material substance (Guattari, Citation2013, Citation2016; Hjelmslev, Citation1954). Simply put, what we see is always conditioned by what is said about it, and vice versa, but neither can be reduced to the other (Deleuze, Citation1988; Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1987).

The interplay of the visible (non-discursive) and the articulable (discursive) also means that the latter is not merely neutral knowledge about the former as the production of knowledge is always tied to it, or, as Foucault (Citation1995, p. 27) expresses it: ‘there is no power relation without the correlative constitution of a field of knowledge, nor any knowledge that does not presuppose and constitute at the same time power relations.’ In other words, it is the latter that has primacy over the former, the articulable being the determiner due to the spontaneity of language, the visible being the determinable due to the receptivity of light (Deleuze, Citation1988). This is why landscape research is never merely descriptive, but interpretative, as argued by Schein (Citation2009).

To make more sense of how darkness renders the abstract machine of landscape inoperative and how illumination re-establishes its visual order in nightscapes, it is best to explicate it with an empirical example. This is done in the following section.

Night and day

The TMS area, ∼120 by 120 m, functions as Turku city centre. It hosts a traditional outdoor market, and it is flanked by public transportation routes, of which nearly all run through the area, making it a local transportation hub. As illustrated in and , the market area was considerably downsized once it was relocated to the eastern corner of the square after the renovations began in October 2018.

Following decades of lobbying, the city opted to renovate the TMS in combination with permitting local investors to build a 600-car parking facility under it. This controversial facility opened in late 2020, as planned. The TMS renovations were expected to be completed at the same time, but the completion was delayed to December 2022.

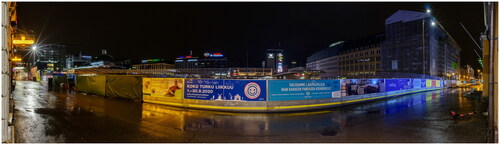

It is worth emphasising that the city centre was effectively closed for four years, which prevented the public from accessing it and adversely affected the local small businesses. The area was cordoned off for the time being and locals started to refer to it as ‘the pit’ instead of the TMS due to the major excavations that were needed to make room for the parking facility. further illustrates the view of the area in the spring of 2021.

The panorama in illustrates how the TMS landscape served corporate interests even in its unfinished form, containing many signifying traits, providing a signifying screen with numerous points of subjectification (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1987; Guattari, Citation2011). Even the barriers and fences that cordoned off people from the area served as advertising hoardings that were hard to miss if one walked through the area. Moreover, the only areas accessible to the public were the routes that lead to the entrances of the privately owned underground parking facility. People’s right to the city and its urban life (Lefebvre, Citation1996) was therefore considerably limited due to the ‘hegemonic liberal and neoliberal market logics’ that presented the parking facility as a necessity for a thriving city centre (Harvey, Citation2008, p. 23). illustrates the same view at night-time.

Darkness has the potential render the world to us in different and, arguably, more egalitarian terms, as argued by Guattari (Citation2013) and Sumartojo (Citation2020), but, as illustrated in , commercial actors harnessed the TMS nightscape to channel people’s desires to serve corporate interests (Williams, Citation2008). Firstly, it is notable that the advertising hoardings were prominently on display even at night-time. Lighting was used to prevent them from being illegible to passers-by. Secondly, and more obviously, the large, illuminated signs and video screens on the sides of the buildings popped out and dominated the nightscape, in stark contrast with everything else, igniting people’s desire to consume, as expressed by Williams (Citation2008). Changing the viewpoint from the accessible sides of the square to one its corners further illustrates this, as apparent from and .

Figure 8. TMS in daylight (view from the corner of Aurakatu and Eerikinkatu). Source: Photograph taken by author.

Figure 9. TMS at night (view from the corner of Aurakatu and Eerikinkatu). Source: Photograph taken by author.

In summary, most of what stood out in dark, namely the illuminated signs and video screens, did not stand out in daylight conditions. In fact, the TMS landscape was so visually crowded that it was difficult to distinguish elements in the landscape. Therefore, contrary to what one might expect, it appears that darkness provides better opportunities to channel desires through signifying nightscape traits that function as points of subjectification (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1987; Guattari, Citation2011) than daylight conditions, at least to those who can afford countering darkness through illumination, as argued by Williams (Citation2008).

Others also took advantage of darkness to express themselves. They utilised the existing well-lit platforms to convey something else, thus challenging the exclusivity of nightscapes discussed by Chatterton and Hollands (Citation2003) and Nofre (Citation2013). This aspect is further investigated in the following section.

Guerrilla tactics

It is worth reiterating that over a hectare of the city centre was largely inaccessible for four years. This limited people’s capacity to act considerably, preventing them from appropriating the urban space for their own activities (Morhayim, Citation2018). It did not, however, prevent people from leaving their mark in the TMS landscape, as illustrated in and .

It may seem counterintuitive to leave one’s mark in a well-lit place in the nightscape, but it makes perfect sense from the perspective of guerrilla tactics. Expressing oneself in the cover of darkness minimises the risk of getting caught, as noted by Cresswell (Citation1998). However, a landscape trait that can only be seen in daylight conditions has to compete for people’s attention with all the other elements, as indicated by Edensor (Citation2017a) and Williams (Citation2008). Therefore, the potential rewards outweigh the risks involved, as argued by Wodiczko (Citation1999) and illustrated in and .

It is also arguable that the renovations facilitated guerrilla tactics. While the buildings and other permanent structures in the TMS were largely devoid of graffiti, the temporary structures, such as the barriers, the signage and the plywood installations were jam-packed with graffiti during the renovations. This is illustrated in .

Figure 10. Graffiti tags on plywood structures, walls, and windows (on Eerikinkatu). Source: Photograph taken by author.

Figure 11. More graffiti tags on plywood structures, walls, and windows (on Eerikinkatu). Source: Photograph taken by author.

Figure 12. More graffiti tags on plywood structures, walls, and windows (on Kauppiaskatu). Source: Photograph taken by author.

Figure 13. More graffiti tags on a sign near a parking facility exit (to Kauppiaskatu). Source: Photograph taken by author.

What is considered temporary is, however, debatable, considering that the area was under construction for four years. Therefore, contrary to what one might expect, these temporary structures were what permitted people to express themselves and their right to the city (Lefebvre, Citation1996), whereas the permanent structures did not.

While most of acts of resistance in the nightscape made use of existing lighting and structures, they largely consisted of graffiti tags, as exemplified by , and, as such, did little to challenge the status quo as it is only likely that these nightscape traits were largely viewed as manifestations of deviant behaviour, as discussed by Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1987). There were some more elaborate graffiti, as exemplified by , and a couple of instances of guerrilla semiotics, as illustrated in and .

Figure 14. An instance of guerrilla semiotics on a City of Turku sign (at the corner of Kauppiaskatu and Yliopistonkatu). Source: Photograph taken by author.

Figure 15. An instance of guerrilla semiotics on an advertising hoarding (on Yliopistonkatu). Source: Photograph taken by author.

The controversiality of the TMS project is brought up in , as people are prompted to ‘wake up’. In the intentions of a private health care provider that seeks to associate itself with the city, and thus its citizens, have been subverted by making it appear that the girl in the large advertisement is unhealthy, something out of a horror movie, with bleeding eyes, thus exhibiting a case of guerrilla semiotics (Dery, Citation2017), signifying that people’s desires are being channelled through signifying traits to serve corporate interests (Williams, Citation2008).

Conclusion

I have sought to illustrate how landscapes and nightscapes function to (re)produce certain identities through channelling of people’s desires and how dependent that production is on daylight conditions and, in its absence, on illumination. Moreover, I have exemplified how illumination is utilised by those with the necessary capital to channel people’s desires through signifying nightscape traits, urging people to consume certain points of subjectification, typically products or services. While darkness obscures the landscape and the elements visible in it, illumination allows certain elements to stand out, which makes a nightscape vastly superior to a daylight landscape, a medium par excellence for those who seek to channel people’s desires.

While corporations dominate nightscapes, people constantly undermine this order of things. People can not only use the cover of darkness to their advantage, to avoid getting caught leaving their mark in the landscape, but they can also utilise the illumination provided by others for their own purposes, so that their expressions can also be seen in the nightscape. The TMS nightscape did not contain many thought-provoking cases of guerrilla semiotics during its renovations, probably because most of the elements that would have stood out in the nightscape would have been difficult to reach, nor elaborate graffiti art, as most of the graffiti consisted of tags. It did, nonetheless, exemplify how people can use existing infrastructure to express themselves and, moreover, to make people aware that their desires are being channelled to benefit corporate interests.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank the Editor and the Reviewers for their feedback. I also wish to thank Heli Syrjälä at the University of Turku for arranging the long term archival of the photos I took to illustrate this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Timo Savela

Timo Savela is a university teacher at the Department of English, University of Turku. His current research focuses on normalisation and production of subjectivity through landscape in the Finnish context.

References

- Bogue, R. (2009). The landscape of sensation. In E. W. Holland, D. W. Smith, & C. J. Stivale (Eds.), Gilles Deleuze: Image and text (pp. 9–26). London: Continuum.

- Boyd, J. (2010). Producing Vancouver’s (hetero)normative nightscape. Gender, Place & Culture, 17(2), 169–189.

- Bracher, M. (1993). Lacan, discourse, and social change: A psychoanalytic cultural criticism. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Brands, J., Schwanen, T., & van Aalst, I. (2015). Fear of crime and affective ambiguities in the night-time economy. Urban Studies, 52(3), 439–455.

- Chatterton, P., & Hollands, R. (2003). Urban nightscapes: Youth cultures, pleasure spaces and corporate power. London: Routledge.

- Christen, R. (2010). Graffiti as a public educator of urban teenagers. In J. A. Sandlin, B. D. Schultz, & J. Burdick (Eds.), Handbook of public pedagogy: Education and learning beyond schooling (pp. 233–243). New York: Routledge.

- City of Turku (2020). Kauppatorin suunnittelukilpailu: 4.2. – 8.5.2020 Arvostelupöytäkirja.

- City of Turku (2021). Information about renovation: Frequently asked questions. https://www.turku.fi/en/new-turku-market-square/information-about-renovation/frequently-asked-questions

- Cook, M., & Edensor, T. (2017). Cycling through dark space: Apprehending landscape otherwise. Mobilities, 12(1), 1–19.

- Cosgrove, D. E. (1985). Prospect, perspective and the evolution of the landscape idea. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 10(1), 45–62. doi:10.2307/622249

- Cresswell, T. (1998). Night discourse: Producing/consuming meaning on the street. In N. R. Fyfe (Ed.), Images of the street: Planning, identity and control in public space (pp. 261–271). London: Routledge.

- Deleuze, G. (1988). Foucault (S. Hand, Trans.). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Deleuze, G. (1990). The logic of sense (M. Lester & C. Stivale, Trans.). London: The Athlone Press.

- Deleuze, G. (1994). Difference and repetition (P. Patton, Trans.). New York: Columbia University Press.

- Deleuze, G. (2004). Desert islands and other texts: 1953–1974 (D. Lapoujade, Ed.; M. Taormina, Trans.). Los Angeles: Semiotext(e).

- Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1983). Anti-oedipus: Capitalism and schizophrenia (R. Hurley, M. Seem, & H. R. Lane, Trans.). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987). A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia (B. Massumi, Trans.). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Dery, M. (2017). Culture jamming: Hacking, slashing, and sniping in the empire of signs. In M. DeLaure & M. Fink (Eds.), Culture jamming: Activism and the art of cultural resistance (pp. 39–61). New York: New York University Press.

- Duncan, J. S. (1990). The city as text: The politics of landscape interpretation in the Kandyan Kingdom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ebbensgaard, C. L. (2015). Illuminights: A sensory study of illuminated urban environments in Copenhagen. Space and Culture, 18(2), 112–131. doi:10.1177/1206331213516910

- Ebbensgaard, C. L. (2019). Making sense of diodes and sodium: Vision, visuality and the everyday experience of infrastructural change. Geoforum, 103, 95–104. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.04.009

- Edensor, T. (2013). Reconnecting with darkness: Gloomy landscapes, lightless places. Social & Cultural Geography, 14(4), 446–465.

- Edensor, T. (2015). The gloomy city: Rethinking the relationship between light and dark. Urban Studies, 52(3), 422–438. doi:10.1177/0042098013504009

- Edensor, T. (2017a). From light to dark: Daylight, illumination, and gloom. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Edensor, T. (2017b). Seeing with light and landscape: A walk around Stanton Moor. Landscape Research, 42(6), 616–633. doi:10.1080/01426397.2017.1316368

- Edensor, T. (2022). Dark designs: Creating shadow, gloomy spaces and enchanting light. In S. Sumartojo (Ed.), Lighting design in shared public spaces (pp. 195–215). New York: Routledge.

- Edensor, T., & Bille, M. (2019). ‘Always like never before’: Learning from the lumitopia of Tivoli Gardens. Social & Cultural Geography, 20(7), 938–959.

- Edensor, T., & Millington, S. (2013). Blackpool illuminations: Revaluing local cultural production, situated creativity and working-class values. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 19(2), 145–161.

- Farrer, J. (2011). Global nightscapes in Shanghai as ethnosexual contact zones. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 37(5), 747–764. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2011.559716

- Foucault, M. (1978). The history of sexuality, Vol. I: An introduction (R. Hurley, Trans.). New York: Pantheon Books.

- Foucault, M. (1980). The eye of power. In C. Gordon (Ed.), & C. Gordon, L. Marshall, J. Mepham, & K. Soper (Trans.), Power/knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings, 1972–1977 (pp. 146–165). New York: Pantheon Books.

- Foucault, M. (1995). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison (A. Sheridan, Trans.). New York: Vintage Books.

- Gallan, B. (2015). Night lives: Heterotopia, youth transitions and cultural infrastructure in the urban night. Urban Studies, 52(3), 555–570. doi:10.1177/0042098013504007

- Guattari, F. (1984). Molecular revolution: Psychiatry and politics (R. Sheed, Trans.). Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Guattari, F. (1995). Chaosmosis: An ethico-aesthetic paradigm (P. Bains & P. Julian, Trans.). Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Guattari, F. (2009). Soft subversions: Texts and interviews 1977–1985 (S. Lotringer, Ed.; C. Wiener & E. Wittman, Trans.). Los Angeles: Semiotext(e).

- Guattari, F. (2011). The machinic unconscious: Essays in schizoanalysis (T. Adkins, Trans.). Los Angeles: Semiotext(e).

- Guattari, F. (2013). Schizoanalytic cartographies (A. Goffey, Trans.). London: Bloomsbury.

- Guattari, F. (2016). Lines of flight: For another world of possibilities (A. Goffey, Trans.). London: Bloomsbury.

- Hadfield, P., & Measham, F. (2015). The outsourcing of control: Alcohol law enforcement, private-sector governance and the evening and night-time economy. Urban Studies, 52(3), 517–537.

- Harvey, D. (2008). The right to the city. New Left Review, 53, 23–40.

- Herzog, M. H., Sayim, B., Chicherov, V., & Manassi, M. (2015). Crowding, grouping, and object recognition: A matter of appearance. Journal of Vision, 15(6), 5–5.

- Hjelmslev, L. (1953). Prolegomena to a theory of language (F. J. Whitfield, Trans.). Baltimore: Waverly Press.

- Hjelmslev, L. (1954). La Stratification Du Langage. WORD, 10(2–3), 163–188. doi:10.1080/00437956.1954.11659521

- Howard, P. (2011). An introduction to landscape. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Iveson, K. (2010). Introduction. City, 14(1–2), 25–32. doi:10.1080/13604811003638320

- Jakle, J. A. (2001). City lights: Illuminating the American night. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Lefebvre, H. (1991). The production of space (D. Nicholson-Smith, Trans.). Oxford: Blackwell.

- Lefebvre, H. (1996). Writings on cities (E. Kofman & E. Lebas, Trans.). Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers.

- Lewis, P. F. (1979). Axioms for reading the landscape: Some guides to the American scene. In D. W. Meinig (Ed.), The interpretation of ordinary landscapes: Geographical essays (pp. 11–32). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Mitchell, W. J. T. (Ed.). (2002). Landscape and power (2nd ed.). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Morhayim, L. (2018). Nightscapes of play: Enjoyment of architecture and urban space through bicycling. Antipode, 50(5), 1311–1329. doi:10.1111/anti.12400

- Nofre, J. (2011). Youth policies, social sanitation, and contested suburban nightscapes. In C. Perrone, G. Manella, & L. Tripodi (Eds.), Everyday life in the segmented city (pp. 261–281). Bingley: Emerald.

- Nofre, J. (2013). “Vintage nightlife”: Gentrifying Lisbon downtown. Fennia–International Journal of Geography, 191(2), 106–121. doi:10.11143/8231

- Pottie-Sherman, Y., & Hiebert, D. (2015). Authenticity with a bang: Exploring suburban culture and migration through the new phenomenon of the Richmond Night Market. Urban Studies, 52(3), 538–554.

- Rose, M. (2006). Gathering ‘dreams of presence’: A project for the cultural landscape. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 24(4), 537–554. doi:10.1068/d391t

- Saussure, F. (1959). Course in general linguistics (W. Baskin, Trans.). New York: Philosophical Library.

- Schein, R. H. (2009). A methodological framework for interpreting ordinary landscapes: Lexington, Kentucky’s Courthouse Square. Geographical Review, 99(3), 377–402. doi:10.1111/j.1931-0846.2009.tb00438.x

- Schivelbusch, W. (1988). Disenchanted night: The industrialization of light in the nineteenth century (A. Davies, Trans.). Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Schulte-Römer, N. (2022). Illuminating experiences. In S. Sumartojo (Ed.), Lighting design in shared public spaces (pp. 17–41). New York: Routledge.

- Shaw, R. (2015). ‘Alive after five’: Constructing the neoliberal night in Newcastle upon Tyne. Urban Studies, 52(3), 456–470. doi:10.1177/0042098013504008

- Sumartojo, S. (2020). On darkness, duration and possibility. In N. Dunn & T. Edensor (Eds.), Rethinking darkness: Cultures, histories, practices (pp. 192–201). London: Routledge.

- Talebian, K., & Riza, M. (2020). Mashhad, city of light. Cities, 101, 1–14.

- Voloshinov, V. N. (1973). Marxism and the philosophy of language (L. Matejka & I. R. Titunik, Trans.). New York: Seminar Press.

- Wetherell, M. (2015). Trends in the turn to affect: A social psychological critique. Body & Society, 21(2), 139–166.

- Williams, R. W. (2008). Night spaces: Darkness, deterritorialization, and social control. Space and Culture, 11(4), 514–532. doi:10.1177/1206331208320117

- Wodiczko, K. (1999). Critical vehicles: Writings, projects, interviews. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Yeo, S.-J. (2020). Right to the city (at night): Spectacle and surveillance in public space. In V. Mehta & D. Palazzo (Eds.), Companion to Public Space (pp. 182–190). Abingdon: Routledge.