ABSTRACT

Although the Great War made extraordinarily complex demands on the nations involved, it is the landscape of the battlefield which has continued to dominate contemporary perceptions of the conflict. Australian and English children’s picture book authors and illustrators have adopted a similar focus, particularly regarding the Western Front. It is the illustrators, however, who have the more complex task, for they have inherited an aesthetic issue that has challenged artists since 1914. Like the British, Australian, Canadian, and New Zealand official war artists of the time, they are confronted, at every turn, by the challenge of depicting a surreally empty landscape. It was not so much a landscape as the artists understood it before the war, but rather an anti-landscape, as though the war had annihilated Nature. What was left was a dystopian wilderness that bore witness to the destructive power of industrialised warfare. This article will explore how a selection of Australian and English children’s picture book illustrators respond to the emptiness of the battlefield landscape, or as Becca Weir so evocatively characterises it, the paradox of measurable nothingness.

INTRODUCTION

Although the Great War made extraordinarily complex demands on the nations involved, it is the battlefield which has remained the most ‘poignant site of the war imaginary’ (Chouliaraki Citation2013, p. 319). Contemporary Australian and English children’s picture book authors and illustrators, who have determinedly kept in step with their respective nation’s imagining of the conflict, have focused on the landscape of the battlefield to the exclusion of almost all else. This is particularly evident when they depict the war on the Western Front. It is the illustrators, however, who arguably have the more complex task, for they have inherited an aesthetic issue that has challenged artists since the very early days of the conflict. Like the British, Australian, Canadian, and New Zealand official war artists, they are confronted, at every turn, by the challenge of depicting a surreally empty landscape, a ‘troglodyte world’ that appeared to be little more than an ‘infinity of waste’ (Gregory Citation2016; Fussell Citation1977, p. 36; Dyer Citation1995, p. 119). It was not so much a landscape as pre-war artists understood it, but rather an anti-landscape, as though humankind had annihilated Nature (Hynes Citation1991, p. 197). The wood, as George Mosse (Citation1990) observes, was being murdered. What was left was a ‘dystopian wilderness … a pestilent waste of shattered trees, toxic soils and scattered bones’ (Gough Citation2018, p. 56). This article will explore how a selection of Australian and English children’s picture book illustrators respond to the emptiness of the battlefield landscape, or as Becca Weir (Citation2007) so evocatively characterises it, the paradox of measurable nothingness. For though the landscape had been all but stripped of identifying features by incessant artillery fire, with only the remains of obliterated villages or woods to recall its peacetime appearance, it was, paradoxically, subject to intense scrutiny. Soldiers remained painfully aware of any landscape feature that, having survived the shelling, might subsequently draw attention to their position or provide the enemy with an advantage. Indeed, twice daily, the Royal Air Force assembled a complete photographic record of the Western Front; the seemingly empty spaces that characterised the battlefield were thereby named and gridded in minute detail (Gough Citation2018). Nothingness was thereby subject to a methodical and sustained scrutiny and measurement.

THE AUSTRALIAN AND ENGLISH ‘WAR IMAGINARY’

The illustrators of contemporary Australian and English children’s picture books about the Great War, and the authors whose text their work complements, embrace an ideological position established in their respective countries during the 1960s. In Australia, the emergence of a ‘kinder, gentler Anzac’ transformed the understanding of the Great War from a narrow and anachronistic one ‘grounded in beliefs about racial identity and martial capacity to a legend that speaks in the modern idiom of trauma, suffering and empathy’ (Holbrook Citation2016, p. 19). This re-invigoration of interest in the Great War occurred just as the Anzac story appeared in terminal decline. This process was driven by a number of imperatives, some of which had been in evidence since 1915, including an increasing interest in family and community history (Holbrook Citation2014), the evolution of war commemoration into a civic religion (Inglis Citation2008) and an expression of displaced Christianity (Billings Citation2015), the status of Australian military history as a sacred parable above criticism (McKenna Citation2007), the commerce and politics of nationalism (McKenna & Ward Citation2007), the pervasiveness of a grand narrative that emphasises the role of Australian military engagements and the Anzac spirit in shaping the nation (Lake Citation2010) and proof of a hunger for meaning, a craving for ritual and a search for transcendence (Scates Citation2006). This renewed interest, which saved the ‘Anzac legend from oblivion’ (Holbrook Citation2016, p. 19) did not challenge the traditional role played by Australian war literature in ‘transmuting the unpleasant particulars of modern combat into an epic model of national achievement’. For if the Great War did indeed bring about ‘a kind of “nervous breakdown” in Europe, then it was Australia’s epiphany’ (Gerster Citation1987, pp. 14–15).

A key component of the national imagining of the Great War is the positioning of landscape as a powerful symbol of historical continuity. By the outbreak of war in 1914 the enduring mythology of landscape in Australian art was already well established (Radford Citation2007). This process reflected a widespread obsession with nationalism and the search for a distinctly Australian national identity. The paintings produced during this period, some of which were painted by artists subsequently selected to work as part of the official war art programme, ‘remain the most iconic and popular … in Australian culture’ (ibid., p. 23). During and after the war, the English saw the Western Front as a disjuncture between the past and the present, ‘a uniquely terrible experience’ that could not ‘be understood as part of any historical process or analysis’ (Badsey Citation2009), as cited in Sheffield Citation2002, p. xiv). In contrast, Australians, steeped in the mythology of landscape, sought to ‘find ways to comprehend and then transcend or assimilate the catastrophes of the war, to make some sense of military events in light of their perceptions about Australia’s past’ (Hoffenberg Citation2001, p. 111). They did this by identifying ‘stunning similarities, and sometimes even mirror images, in those distant landscapes’, ones which positioned both the Australian landscape and the battlefield as ‘new lands to be claimed’ (Hoffenberg Citation2001, p. 119).

Modern weaponry facilitated this conflating of the past with the present for it had driven armies underground, destroyed physical landmarks, pulverised the landscape, caused the literal disappearance of towns and villages, and inverted night and day. During daylight hours the ‘phantasmagorical lunar face of no-man’s land appeared deserted and outwardly calm’ (Gough Citation2018, p. 27). In contrast, at night, the battlefield teemed with activity and potential threats as soldiers repaired or improved their trenches, conducted patrols, and brought up supplies. In this ‘primordial world of confusion, heat, thirst and dust’ soldiers learnt to be wary of finding themselves near a landscape feature that the enemy might consider distinctive (Hoffenberg Citation2001, p. 119; Gough Citation2018). It was far safer to seek the fragile sanctuary afforded by a landscape devoid of any identifying feature that might attract the attention of enemy machine guns or artillery. Australia’s first white martyrs, the explorers, had lived and died in an ‘Outback’ that did not include any of the usual markers of European civilisation. Their descendants now did the same on European battlefields. When it came time to respond artistically to the first major war in the nation’s history, Australian artists drew on the familiar by adopting the academic style in which they had been trained in pre-Federation Australia (Burn Citation1990). For just as there would later be no room for modernism in war memorial design (Bedford et al. Citation2021), there was little sympathy in the official war art programme for what Charles Bean (Citation1928), the official war correspondent, editor of the official history, and founder of the Australian War Memorial (AWM), dismissed as ‘freak art’ (p. 4). This was in line with many Australian critics who derided modernism as an ‘alien disease’ (Williams Citation1995, p. 24).

As Laura Brandon (Citation2006) observes, however, as sites of social remembering, the aesthetic qualities of a canvas are invariably less important than the meanings imposed on it or which are derived from it. The official war art programme, which Bean helped initiate and lead, was driven by a very clear understanding of what meanings should be derived from the artwork. He saw the Great War almost exclusively in terms of national character and achievement. Wherever he looked during the war years he saw proof of Australian exceptionalism, and in the process forged a ‘cult of the individual as hero, who because of the influence of the bush and his frontier background is already a natural soldier who has only to pick up a rifle to be ready for battle’ (Pugsley Citation2004, p. 47). The artwork would therefore serve as a pictorial record of the nation at war, central to which was the battlefield. Anything that was gruesome or harrowing, even if it had artistic merit was excluded, for it was assumed that visitors to the AWM, the nation’s most important cultural institution and where the artwork from the official war artists is still displayed, were not looking for art. Instead, they were visiting ‘in a spirit of reverence and not a little sorrow’ (Scheib Citation2015, p. 305). The narrowness of the collecting parameters was further entrenched by the decision that only Australians were employed as official artists, many of whom had already made a name for themselves before 1914. This ensured that the artwork, which included film and photography, had a particularly strong nationalist focus, reflected the wider preoccupations of Australian art, landscape foremost among them, and focused on the battlefield to the exclusion of almost all else. Indeed, for many Australians, the official photographs taken by Frank Hurley of the shattered landscape during the latter part of the Third Battle of Ypres (31 July–10 November 1917) are the Great War. As Andrews (Citation1993) observes of their continuing impact on the collective memory, it is as if the soldiers are ‘doomed, in a parody of the Flying Dutchman, to continue to fight their hopeless battles in the mud of Flanders for ever’ (p. 3). Despite efforts over subsequent years to broaden the collection, it still is a significant part of ‘a national mythology that privileged a narrative of the Australian soldier on the battlefield, coming at the expense of a more nuanced story of Australia in the war’ (Hutchinson 2018, para. 19). In contrast, the familiarity of landscape imagery and the post1960s focus on trauma permits Australian children’s picture book authors and illustrators to produce work that is often overtly anti-militaristic, indeed almost pacifist in its intent, without challenging, let alone interrogating the courage and sacrifice of the Australian soldier (Kerby et al. Citation2017a).

For all the many great works generated by the British Official War Art scheme, English authors and illustrators draw on an imagining of the Great War shaped by war poets such as Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon. Now widely recognised in England as the authentic voice of the frontline soldier, they have helped position the conflict in the public imagination as a ‘meaningless, futile bloodbath in the mud of Flanders and Picardy – a tragedy of young men whose lives were cut off in their prime for no evident purpose’ (Reynolds Citation2014, p. xv). The war, as Leon Wolff (cited in Bond Citation1997, p. 487) characterised it, ‘meant nothing, solved nothing and proved nothing’. Since the 1960s, this has been the dominant imagining of the Great War in England, one that reflected the ‘very different concerns and political issues of that turbulent decade, but [also] in part resurrecting anti-war beliefs of the 1930s’ (Bond Citation2002, p. 51). It received an academic imprimatur of sorts from a range of literary and artistic responses to the conflict, notably Leon Wolff’s (1958) In Flanders Fields, Alan Clark’s The Donkeys (1961), A. J. P. Taylor’s The First World War (1963), the BBC series The Great War (Citation1964) and the play (and then movie) Oh! What a Lovely War (Littlewood Citation1963 /1969). Their influence, and that exerted by the poets, is evident in a national imagining of the conflict framed by the existence of a Western Front of history and a Western Front of literature and popular culture; the latter, unsurprisingly, is profoundly unhistorical (Badsey Citation2009, pp. 39–51). Despite being challenged by any number of respected historians, it is the literary Western Front with its ‘poets, men shot at dawn, horror, death, waste’ rather than the historical that exerts the greater influence outside academia (Todman Citation2005, pp. 158–60). Nothing it seems can penetrate ‘the popular shroud of death, waste, and futility’; indeed, no generation since the 1920s has questioned this imagining (Spiers Citation2015, p. 77; Hynes Citation1991). As Margaret Baguley and Martin Kerby (2021) found when researching children’s picture books about the 1914 Christmas Truce, whatever their claims to historical authenticity, English authors and illustrators are enthusiastic devotees of the literary Western Front.

Though not an opinion likely to be widely shared outside of academic circles, the overall performance of the Australian official artists was not comparable to their English counterparts. Indeed, one critic has gone as far as describing it as mediocre (Scheib, Citation2015). In contrast, the war stimulated some of the best British art of the twentieth century (Gough Citation2010). Paul Nash’s Menin Road, one of the finest works by a British official artist, is indicative of the difference between the Australian and English approach. The painting is about ‘annihilation, a natural world laid waste, emptied of life and of old meanings, containing nothing except ruin, and a few men who struggle towards nowhere’. Nash and his contemporaries ‘turn war into an emptiness’ (Hynes Citation1991, p. 296), an approach that has influenced the work of the children’s picture book authors and illustrators explored in this article. Yet unlike the war artists who used landscape to argue that the war was meaningless, children’s picture books generally seek to offer some moral instruction appropriate to a modern audience without offering a significant challenge to accepted orthodoxy. The annihilation of Nature is therefore retained as proof of the war’s futility, as a modern readership would expect. From that point all that is required is to position Nature’s regeneration as evidence that for all its terror and suffering, war is an anomaly, book-ended by peace and prosperity. Younger readers are thereby led from a world at peace, through the degradations of war, and then back to peace. Older readers make the same journey but are encouraged to make a more nuanced connection between the shared victimhood of the Germans and their own world. Regardless of the age of the reader, however, they are positioned to recognise that just as the physical landscape can heal itself, nations and peoples can likewise overcome trauma.

THE ART OF WAR IN CHILDREN’S PICTURE BOOKS

As they are usually chosen by parents or family members, children’s picture books are an important indicator of contemporary attitudes and morals and often reveal what parents and teachers desire for children (Flothow Citation2007; Avery Citation1989). Books about the Great War in Australia and England are therefore usually framed by a ‘structured configuration of representational practices, which produce specific performances of the battlefield at specific moments in time’. These representations ‘cultivate longer-term dispositions towards the visions of humanity that each war comes to defend’ (Chouliaraki Citation2013, p. 318). Esther MacCallum-Stewart (Citation2007) describes this as the parable of war, one that is not wedded to notions of historical accuracy but is instead an emotive and unashamedly literary retelling of the war. Authors and illustrators are thereby constrained less by history than an imagining of the war that has become ‘almost immutable, encased in invented tradition and embedded in an orthodoxy of remembrance that is all pervasive’ (Gough Citation2018, p. 14). These traditions are not falsifications of reality but are instead imaginative versions of it. Nevertheless, these authors and illustrators, like historical novelists, ‘declare intentions similar to historians, striving for verisimilitude to help readers feel and know the past’ (Lowenthal Citation1985, p. 224). By domesticating this difficult past, it is enlisted in the service of an ideology firmly rooted in the present (ibid., p. xv). Authors and illustrators are nevertheless subject to the constraints of the genre. They engage with ‘unimaginable, unspeakable, and un-representable horror’, but must balance their art with the imagined ‘demands of children’s literature as sanitary, benign, and didactic’ (Trezise Citation2001, p. 102). They usually respond to this demand for compromise by exploring the underlying humanist principles of the stories they tell. Historical particularities are thereby transformed into ‘universals of human experience’ (Stephens Citation1992, p. 205).

The images in a children’s picture book play a vital role far beyond merely illustrating the text. There is a synergy between the text and images, certainly, but they do not operate on the reader in the same way. As Perry Nodelman (Citation1988) observes, words have a greater potential for conveying temporal information whereas pictures have a greater potential for conveying spatial information. Lawrence Sipe (1988) characterises this as the difference between how we experience the two mediums; we ‘see a painting all at once; but in order to experience literature or music, we have to read or listen in a linear succession of moments through time’ (p. 100). Although a picture book is a hybrid form based on both time and space, the reader is nevertheless encouraged to ‘gaze on, dwell upon or contemplate’ the artwork while being ‘driven ever forward by the temporal narrative flow’ (Sipe Citation1998, pp. 100–1). The belief that an image is particularly suited to conveying spatial information is an interesting one given the reality that few paintings or photographs created during the war years succeed in capturing the immensity of the void that was the Western Front or the intensity of its emptiness (Gough Citation2018). How then, do Australian and English artists who illustrate modern children’s picture books visualise emptiness, while encouraging their viewers to gaze on, dwell upon or contemplate the nature of war and humanity?

THE ARTISTS

Three Australian picture books are analysed in this section: the first two, Voices from the Trenches (2017) and Boys in Khaki (2015) were funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs. The Department was just one source of State and Federal funding that reached half a billion dollars during the centenary of the Great War (per soldier killed that is between five and nineteen times higher than the average spend per death by New Zealand, Canada, United Kingdom, France, and Germany). This financial commitment is indicative of the extent to which the Australian war mythology is driven from above by governments of all political persuasions. The third Australian example, In Flanders Field (2002 /2014) is still in print and was well regarded enough to be re-issued during the first year of the centenary as one of the early contributors to a wave of war themed picture books. Its continued success is indicative not just of its quality, but of its adherence to the popular understanding of the war.

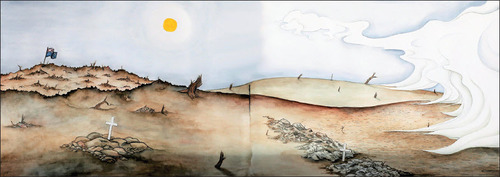

The Australian illustrators Margaret Baguley and Eloise Tuppurainen-Mason respond to the annihilation of the landscape at both a literal and metaphorical level in a manner quite different from their English counterparts. Baguley’s image The Wasteland () is of a distant barrage seen from across the desolation of no man’s land (Voices from the Trenches, Kerby et al. Citation2017c). She responds to the emptiness of the Great War battlefield by emphasising historical continuities; a viewer operating without context might just as easily interpret her imagining of the battlefield landscape to be a bush fire or dust storm in Outback Australia. Although Paul Fussell’s The Great War and Modern Memory (1977) is to be used by historians with caution, his observations about the ‘sharp dividing of landscape into known and unknown, safe and hostile’, ‘the collective isolation’ of trench war, ‘its defensiveness and its nervous obsession with what the other side is up to’ are instructive in this instance (pp. 76–9). For though Baguley has drawn on the physical and implied separation of no man’s land, the absence of barbed wire and the detritus of war cannot have been accidental. Its presence would mark for the reader, as it did the soldiers, the shift from the relative safety of the trenches into a dangerous, remote and mysterious landscape: ‘the [implied] presence of the enemy off on the borders of awareness feeds anxiety in the manner of the dropping-off places of medieval maps’ (Fussell Citation1977, p. 76). Yet the inclusion of human figures would have made Baguley’s image far less threatening, for it is the landscape itself which confronts and threatens the reader.

Plate I. The Wasteland by Margaret Baguley, in Voices from the Trenches written by Martin Kerby and illustrated by Eloise Tuppurainen-Mason and Margaret Baguley © 2017.

Tuppurainen-Mason’s image The Somme () (O’Reilly et al. Citation2015) is more detailed but draws on the same metaphorical content as Baguley’s. She positions the destruction of the landscape as an allegory for the destruction of war, yet the cloud drifting across no man’s land toward the ridge at Pozières, mythologised as a site ‘more densely sown with Australian sacrifice than any other spot on earth’ (Bean Citation1983, p. 264) is pervaded by ambiguity. Is it the smoke of battle? Is it a metaphor for the de-humanisation of war, both literally through the absence of humans, or metaphorically for the assault on civilised values that it represents? Is it a reference to Will Longstaff’s iconic Menin Gate at Midnight that uses spectral figures to symbolise the spirit that carried the men forward, 23,000 of whom became casualties in a six-week period in 1916? Is it the Missing, the men who just disappeared in the mud and are now ‘known unto God’? This ambiguity is juxtaposed against the presence of a beleaguered Australian flag on the ridge, which may reference the nation building role many Australians see as integral to their understanding of the Great War. Tuppurainen-Mason’s addition of two white crosses and the pitiful remains of the village of Pozières reminds the reader that though the landscape possesses a physical nature, it is also, as Tuan (Citation1979) observes, a construct of the mind. The daily confrontation with this landscape left soldiers fearing not just their own death, but the collapse of their world, a final surrender of integrity to chaos. This victory for chaos was most readily personified in the landscape; apart from major battles or periods out of the line, a soldier spent most of his time in a trench or dugout with only a narrow strip of sky to remind him of the outside world. To move about above ground during the day was to risk almost certain death. Enemy combatants, subject to the same conditions, were rarely seen. When death came, it was impersonal; sixty per cent of casualties were inflicted by distant artillery. Under these conditions, it was hardly surprising that the landscape became a ‘personalised evil’, a ‘hostile force [that] whatever its specific manifestation, possessed will’ (Tuan Citation1979, p. 7). It was not just the natural landscape that could be characterised as a construct of the mind. For the French inhabitants of Pozieres, it represented the loss of all ‘that is familiar – the destruction of one’s environment – [which] can mean a disorienting exile from the memories they have invoked’ (Bevan Citation2006, p. 13). For Australians, however, the physical environment of the battlefield was, as Tuppurainen-Mason argues, a hostile foe, one that both invoked memories of a mythical past and highlighted their link to the present (Kerby et al. Citation2017b).

Plate II. The Somme by Eloise Tuppurainen-Mason, in Voices from the Trenches written by Martin Kerby and illustrated by Eloise Tuppurainen-Mason and Margaret Baguley © 2017.

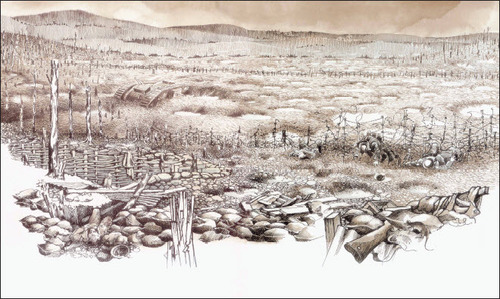

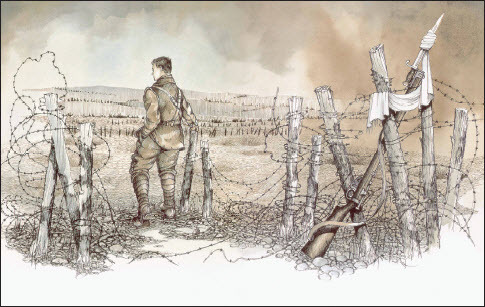

In Flanders Fields (Jorgensen and Harrison-Lever 2002 / 2014) is the fictional story of an Australian soldier who risks his life by crossing no-man’s land to rescue a robin trapped in the barbed wire. The book opens with Brian Harrison-Lever’s two-page image of the battlefield viewed from the Australian side of no man’s land (). The ‘pitted and ruined landscape’ and the ‘huge, desolate battle ground’ that dwarfs the individual soldier is a classic of its type. By positioning the landscape as both the site and the cause of human suffering, Harrison-Lever emphasises the landscape’s capacity to exert agency over everything in its orbit. The addition of a knocked-out tank which sits trapped in the mud like a prehistoric animal makes it clear that even the machine age cannot impose limits on its power. Equally important to the narrative is the complicity of the German soldiers, who allow the rescue to occur without firing on the exposed soldier. By crossing no-man’s-land and approaching the German lines, the soldier bridges an ostensibly impassable divide, both in a literal and a metaphorical sense. The soldiers, both German and Australian, are thereby firmly cast as victims rather than perpetrators. It is not their war. By leaving his white silk scarf and his rifle leaning against the barbed wire when he returns to his own trench, the soldier rejects the war and the empty values for which it is being fought (). The reader is encouraged to do likewise, for as Harrison-Lever acknowledges, ‘it was certainly not intended as a work of historical non-fiction, for there is, in his view, ‘an element of fiction in all histories’:

From first reading, I understood, or at least interpreted the Jorgensen text, as being metaphor. I certainly used metaphor in my approach to the illustrations. Innocence trapped, deception, ignorance, the white silk scarf for example. Loss of life and loss of hope, competing with humanity and compassion on both sides of ‘no man’s land’. (pers. comm., 22 March 2021)

Plate III. In Flanders Fields written by Norman Jorgensen and Illustrated by Brian Harrison-Lever (© 2002/ 2014, publ. Fremantle Press).

Plate IV. In Flanders Fields written by Norman Jorgensen and Illustrated by Brian Harrison-Lever (© 2002/ 2014, publ. Fremantle Press).

Though Harrison-Lever did not consciously draw on the Australian landscape while illustrating the text, he has nevertheless always found the Australian Outback ‘a beckoning force’ (pers. comm., 21 March 2021). Yet he never loses sight of the fact that he is a war artist as much as he is an illustrator: dead bodies hang from the wire, the minds of the soldiers have been ‘damaged by the weeks of deafening noise’, and letters and parcels are returned to the rear area because the intended recipients are now dead. Behind Harrison-Lever’s empathy, there is anger. He rejects the widespread celebration of soldiers who ‘gave their lives’: ‘I cannot and have never agreed with that. I believe, in fact I know, their lives were brutally taken’ (pers. comm., 18 March 2021). Indeed, Harrison-Lever was not left untouched by the process of illustrating the text and the research that guided it:

I had of course done some reading prior and seen the usual films. From the start I understood that it would be folly to simply rely on just this. The research I did and the emotional toll it took is still with me today. I am sure that using our, at the time, eighteen year old son as the model for the young soldier also had a big impact on the work. (pers. comm., 3 December, 2021)

Harrison-Lever is English born, and one wonders how much he absorbed of that nation’s widespread rejection of the war as a futile and unnecessary bloodbath. Though neither author nor illustrator used it as inspiration, English readers might well make a connection with the Christmas Truce observed by English and German soldiers in 1914, which since the 1960s has been perceived as a ‘historiographical touchstone for the conventional narrative of the First World War and an enticing shorthand for the view that the conflict was futile and senseless’ (Crocker Citation2015, p. 6). In Harrison-Lever’s case, however, his response was shaped by an affinity with nature that pre-dated his work as an illustrator by many decades, one which exists quite separately from his views on the war:

From my early youth the mountain country of Britain had been a magnet. It had been a joy as a youngster to pull on a pair of studded boots and wander through and over peat hags and rocky outcrops of the Peak District. Back in England for a working holiday in the 1960s I rediscovered this affinity for ‘the wild’ and spent four years climbing the mountains of the Scottish Highlands and the Cumbrian Lake District. (pers. comm., 21 March, 2021).

Harrison-Lever draws on elements evident in the work of both the Australian and English illustrators explored in this article. Australians have traditionally ignored the disjuncture between war and peace by making connections between active service and life on the frontier, both in terms of the landscape and national character. The landscape of the battlefield is construed as the wartime equivalent of the Australian Outback, while the nation’s soldiers are positioned as a modern incarnation of well-established archetypes. The bushman, the ‘presiding deity’ and ‘noble frontiersman’ of Australian literature since the 1880s, the bushranger, the explorer, and the itinerant rural worker have proved particularly adaptable to the nation’s war mythology (Ward Citation1966, p. 223; Bennett Citation2009, p. 158). As Fay Anderson and Richard Trembath (2011) observe, they are literary constructs that have ‘largely remained static in the Australian imagination’ (p. 139).

The English picture books analysed in this article are award-winning collaborations between Hilary Robinson and Martin Impey, a collaboration between a poet laureate, Carol Ann Duffy, and the illustrator David Roberts (an official imprimatur only hinted at, in contrast to the Australian examples), and a posthumous collaboration between Wilfred Owen, the most famous of the war poets, and Martin Impey. There is a prima facie case to be made that the absence of government funding does not lead to a radical reimagining of the conflict in children’s literature. Both the English and Australian examples analysed in this article conform to their respective nation’s imagining of the conflict. The English authors and illustrators soften some of the rhetoric concerning the war’s futility, but that reflects the demands of children’s literature rather than an exploration of the radical potential of the genre. It is an area worthy of further research. For English audiences, the immense environmental degradation is accepted as compelling evidence of the extent of the calamity of war rather than evidence of historical continuity. Indeed, as Paul Gough observes, one of the cruellest ironies of the Great War was that ‘amidst the devastation, human relationships with nature – and with trees especially – were forced to change’:

Camouflage mimicked their elegant patterns, fake trees concealed snipers and observers, copses hid batteries of artillery, subterranean dugouts were filled with the smell of freshly hewn wood and ancient willows were bent into shape as revetments for frontline trenches. Woodlands were transformed into strongholds that were fiercely fought over by both sides. Single isolated trees became a registration point for enemy artillery. Soldiers soon learned to avoid such places. (Gough Citation2018, pp. 52–3).

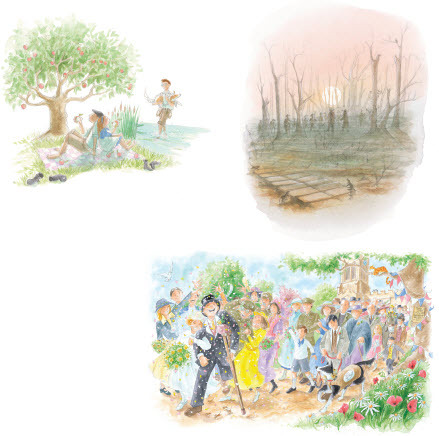

Peace Lily (Robinson & Impey 2017) and Where the Poppies Now Grow (Robinson & Impey 2015) are two notable and commercially successful examples of this approach. Peace Lily is the fictional story of a young woman who becomes a nurse when her two childhood friends join the army. The text opens with an imagining of pre-war England dominated by images of sunshine, picnics, paddling in brooks, running in the woods, and hiding in the old willow trees (). This idealised portrayal is indicative of the widespread view that the Spring and Summer of 1914 was ‘marked in Europe by an exceptional tranquillity’ (Winston Churchill, in Steiner Citation1986, p. 215). Beyond the world of politics, it was a ‘hot, sun drenched, gorgeous summer … the most beautiful within living memory … remembered by many Europeans as a kind of Eden’ (Fromkin Citation2004, p. 11). When war disrupts this idyll, the disjuncture with the past is evident in the changes wrought on the physical landscape, most notably the ‘slimescape’ of the trenches and the ‘diabolical agency’ of the mud (Das Citation2014; Gregory Citation2016, p. 8). Martin Impey’s illustrations of the battlefield are in effect an elegy for the landscape. In this case, however, the return of peace shows that, at least in this moment, Death shall have no dominion. On the morning of the Armistice, Impey shows soldiers half obscured by the November frost, above ground, surrounded by shattered trees. The sun rising through the mist gives them a spectral appearance, as they merge with the landscape rather than battling it as they had done for four years. The landscape is beginning to heal as the relationship between humans and nature is restored (). The final image of Lily marrying her childhood friend who she nursed back to health after he was badly wounded is dominated by the greens, reds and yellows of the English countryside in Spring, itself a powerful metaphor of new life (). The book thus concludes with the birth of both a new day and a new world where the protagonists are again in Rupert Brooke’s (1914) idealised image, ‘breathing English air / Washed by rivers, blest by suns of home’. Landscapes, as David Lowenthal (Citation1990) observes, and Impey implicitly understands, drip with human meaning, both ‘in our lives and in our hearts’ (p. 29).

Plates V–VII. (Images ©M.IMPEY 2018, from the book Peace Lily by Hilary Robinson & Martin Impey, publ. Strauss House Productions).

Robinson and Impey also book-end Where the Poppies Now Grow (2015) with a rural idyll, in this case, one most evocatively referenced in the repeated use of an image of a field of red poppies (). The first use of the image uses dark clouds to herald the approach of war and the end of the glorious summer of 1914. The second use marks the return of peace, with the sun now emerging from behind the clouds. The images of the battlefield that populate the pages in between offer no such comfort. The landscape is an enemy, one that is almost sentient, seemingly intent on waging its own war on humanity. The survival of the two protagonists and their eventual return to their prewar lives in rural England shows both author and illustrator subverting their own imagining of the war as a disjuncture. The landscape, like the people, has survived, and will again thrive. Yet as Hew Strachan (Citation2001) observes, though it is a compelling image, the juxtaposition of ‘a sun-dappled and cultured civilisation and a mud-streaked and brutish battlefield’ has its limitations (p. 114). For just a few miles behind the frontline was an agrarian landscape, ‘a reassuring rurality’ in which many soldiers took refuge while out of the line (Gregory Citation2016, p. 5). Yet this nuance has little to no impact on children’s literature. Refuge is provided by the landscape but not during the war, only in times of peace. During the war the landscape is visual proof of the calamity of conflict. In contrast, the landscape of pre-war and post war-England represents the world that will soon be shattered by war and the one that will re-emerge in peacetime. The religious undertones, not least the parallel with the Resurrection of Jesus, are consistent with the approach adopted by most children’s picture book authors and illustrators who generally avoid explicit references to religion and instead allow it to leave ‘its residual mark in ways that are implicit rather than intentional’ (Worsley Citation2010, p. 162).

Plate VIII. (Image ©M.IMPEY 2018 from the book Where The Poppies Now Grow by Hilary Robinson and Martin Impey, publ: Strauss House Productions).

The Christmas Truce (Duffy & Roberts Citation2014) and The Christmas Truce: The Place where Peace was found (Robinson & Impey Citation2014) focus on the effort of frontline soldiers to maintain their humanity, however precariously, amidst the destruction of the landscape and of civilised values. Both use the 1914 truce as their setting, which allows an equal focus on German and English troops. The Christmas Truce, written by Carol Ann Duffy, a UK Poet Laureate and professor of contemporary poetry, provides little historical context and is, in effect, an illustrated poem. Duffy’s language choices are nevertheless confronting. References to the ‘dead lay[ing] still in no man’s land’, ‘an owl swoop[ing] on a rat on the glove of a corpse’, ‘frozen foreign fields [that] were acres of pain’, and ‘men who would drown in mud, be gassed, or shot or vaporised’ firmly place this work in the pity of war school. In writing poetry, Duffy is intent on revealing a truth; in this case, her truth is grounded in the ‘emotive assumption that the protest poetry of the First World War represents the “correct” moral reading of the war’ (McCallum-Stewart 2007, p. 178). It would have been surprising had it been otherwise; by the time this book was released in 2014, the history of the war had long been ‘distilled into poetry’ (Reynolds Citation2014, p. xv). Perhaps freed by Duffy’s approach, one which transforms the story of the Christmas Truce into a fable in verse, Roberts has eschewed realism and instead has created ‘touchingly childlike illustrations’ (Roche Citation2015). They are, however, unflinching in their representation of death in a landscape mutilated by war and thereby acknowledge the ‘frightful interdependence [between] human death and environmental death’ (Keith Citation2012, p. 77). The outline of human corpses, stripped of their identity by the horrors of mechanised warfare, lying scattered across no man’s land, are particularly evocative. They have been subsumed, perhaps even consumed, by a landscape now devoid of any of the features used to identify specific places in peacetime. Though it is a landscape that can be measured, it is pervaded by a sense of nothingness.

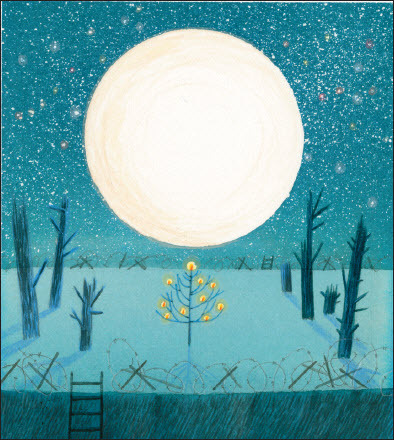

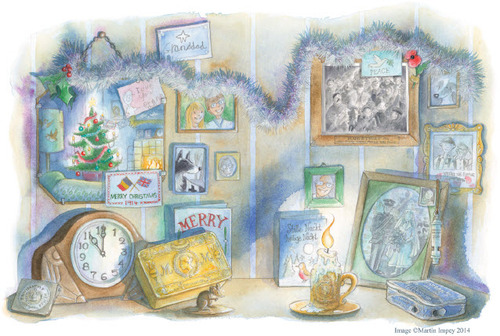

As they bridge the divide between the trenches to celebrate the truce, the soldiers have now come full circle. The idealism that motivated enlistment, like the landscape, has been destroyed. The war has shattered pre-war patriotism and replaced it with compassion and empathy. The soldiers, and the readers, have now adopted the correct moral reading of the war: ‘It was up and over, every man, to shake the hand of a foe as a friend, or slap his back like a brother would’. They exchange gifts and ‘make of a battleground a football pitch’, thereby returning the landscape to a peaceful use (Duffy & Roberts Citation2014, p. 29). The soldiers are all victims, unwilling participants in war, surrounded by the ‘sprawled, mute shapes of those who had died’ (ibid., p. 20). The no man’s land rendered here by Roberts is not so much grim, but isolated, a disjuncture in time and place (). The war artists struggled to portray the emptiness of the landscape, for they could see little more than the Wordsworthian idea of natural benevolence lying dead in the mud and filth of the landscape of the Western Front (Hynes Citation1991, p. 199). Roberts sees the corpses and the destruction of the landscape as clearly as anyone, but after this ‘marvellous, festive day and night’ these ‘fallen comrades’ are now buried ‘side by side beneath the makeshift crosses of midwinter graves’ (Duffy & Roberts Citation2014, p. 34). They have been joined in death in a way that had made impossible in life. The reassurance that the disjuncture is not permanent drives the narrative focus of The Christmas Truce, the Place where Peace Was Found (Robinson & Impey Citation2014). It is as much a Christmas parable as it is a response to an historical event: the image of German and British soldiers attending a mass together in a shattered Church is fictionalised, yet redolent with connections to peacetime Christmas celebrations. Concluding the story with an image of the now elderly soldier’s home where there is a collection of wartime memorabilia and photographs of children and grandchildren emphasises that lives, like destroyed landscapes, heal over time.

Plate IX. (Image taken from the book The Christmas Truce by Carol Ann Duffy, illustration by David Roberts; www. artistpartners.com, published by Picador Books – Pan Macmillan).

The one children’s picture book that embraces the war as a disjuncture is Dulce et Decorum Est (2018) a posthumous collaboration between Wilfred Owen (1893–1918) and Martin Impey. Wilfred Owen, whose poem gives the book its title, has, like the other soldier poets, been ‘transmuted into the supreme truth-teller[s] of the Great War’. Yet the fact that they penned some of the most powerful anti-war poetry in modern literature should not be allowed to obscure the fact they were atypical and far from representative of the almost nine million men who served in the British Army during the war (Reynold 2014, p. 187). Benefitting from the iconic stature of a poem now installed as the sacred catechism of the modern imagining of the war, Impey’s artwork is particularly confronting, for gone is the reassurance offered by the English landscape. In its place are images of soldiers obscured in gas clouds, half formed spectral figures that appear barely human in their gas masks (). The desolation of the landscape is complete. Measurable nothingness has become reality and given a tragically human dimension in the form of the tortured dreams of the returned soldier. The landscape might indeed heal, but this soldier’s survival was a pyrrhic victory. In the words of the author of All Quiet on the Western Front, he may have escaped the shells, but he has nevertheless been destroyed by the war (Remarque Citation1929).

Pl. X. (Image ©M.IMPEY 2018, from the book The Christmas Truce: The Place Where Peace was Found by Hilary Robinson & Martin Impey, Publ: Strauss House Productions).

Plate XI. (Images ©M.IMPEY 2018 from the book Dulce et Decorum Est by Wilfred Owen & Martin Impey, publ. Strauss House Productions).

Impey regularly collaborates with Hilary Robinson on Great War picture books, but the use of Owen’s poem has allowed for a distinctly different approach. In being freed from the expectation that children’s literature should be benign and didactic, Impey has created one of the most visceral images to appear in all of children’s literature. The poem describes the effect of a gas attack on a group of English soldiers and the ‘ecstasy of fumbling/ Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time/ But someone still was yelling out and stumbling/ And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime/ Dim through the misty panes and thick green light/ As under a green sea, I saw him drowning’. It is the description, though, of the impact on the soldier who had been too slow in fitting his helmet that draws from Impey his greatest image: ‘If in some smothering dreams, you too could pace/ Behind the wagon that we flung him in/ And watch the white eyes writhing in his face/ His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin’.

The Devil is holding (dangling) a large bunch for identification ‘dog’ tags as well … he has collected them just as the soldiers would to identify the bodies. I felt it important to not caricature him too much (Fork, Point - tail etc) but I wanted to show this emaciated, malnourished (spinal column clearly visible) creature, oversized sat atop the bodies, yet with all this at his disposal he should be flourishing … but even ‘he too’ is sick of the scale of slaughter and can no longer see sense or reason for all this, hence his slumped appearance, ashamed to show his face. He too wants no part of this. (pers. comm., 26 November, 2021).

In the background are trees shredded by shell fire, three of them an explicit reference to the crosses on Golgotha, the hill of execution outside Jerusalem. The site of Jesus’ death is linked to the landscape of the Western Front, but there is no hope of resurrection or redemption, as is evident in the stories about the Christmas Truce, just nightmares, where ‘before my helpless sight/ He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning’ ().

CONCLUSION

The illustrators of these books acknowledge that the landscape of the Great War battlefield was rarely neutral. It was, as Gough (Citation2018) observes, ‘divided unequally between the safe and unsafe, between refuge and prospect … in front lay the unknowable, beyond lay the unreachable’ (pp. 30–1). The illustrators have embraced the myopia of the infantryman. They focus on the knowable; the small stretch of no man’s land and the German trenches that oppose them, for beyond that limited world is only the diminishing hopes for victory and individual survival. The illustrators have confronted the challenge of representing this landscape, stripped as it is of identifying features, with the soldiers living beneath the surface. What is absent becomes more important than what is visible. In the illustrators’ hands, the landscape must therefore become more metaphor than reality; for Australians, it is about continuity, for the English it is an indictment of the war and the men who direct it. The return of the landscape to its pre-war state offers them hope, if not to the soldiers to the readers who come to the books immersed in a modern imagining. In that sense, they find what they expect to see. For though landscape promises a revealed truth, it inevitably disappoints when applied to national identity; ‘it only exists as a series of signs within a cultural reference’ (Willis Citation1993, p. 64). The authors complex tapestry of cultural constructions of place and illustrators of the picture books explored in this … buried and emerge out of the shifting sands of article know this only too well.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Anderson, F., & Trembath, R., 2011. Witness to War: the history of Australian conflict (Melbourne).

- Andrews, E. M., 1993. The Anzac Illusion: Anglo-Australian relations during World War 1 (Melbourne).

- Avery, G., 1989. ‘The Puritans and their heirs’, in Children and Their Books: a celebration of the work of Iona and Peter Opie, ed. G. Avery & J. Briggs (Oxford), pp 95–118.

- Badsey, S., 2009. The British Army in Battle and its Image 1914–18 (London).

- Baguley, M., & Kerby, M., 2021. ‘A beautiful and devilish thing: children’s picture books and the 1914 Christmas Truce’, Visual Communication, pp. 1–24; https://doi.org/10.1177/1470357220981698.

- Bann, S., 1984. The Clothing of Clio: A study of the representation of the past (New York).

- Bean, C. E. W., 1983. Anzac to Amiens (Canberra):

- Bean, C. E. W., 1928. ‘Parliamentary Standing Committee on Public Works’, Report Together with Minutes of Evidence Relating to the Proposed Australian War Memorial (Canberra).

- Bedford, A., Gehrmann, R., Kerby, M., & Baguley, M., 2021. ‘Conflict and the Australian commemorative landscape’, Hist Encounters, 8 (1), pp. 13–26.

- Bennett, B., 2009. ‘The short story, 1890s to 1950’, in The Cambridge History of Australian Literature., ed. P. Pierce (Melbourne), pp. 156–79.

- Bevan, R., 2006. The Destruction of Memory: architecture at war (London).

- Billings, B., 2015. ‘Is Anzac Day an incidence of “Displaced Christianity?”’, Pacifica: Australasian Theological Stud, 28 (3), pp. 229–42. doi: 10.1177/1030570X16682526

- Bond, B., 1997. ‘Passchendaele: verdicts, past and present’, in Passchendaele in Perspective. ed. P. H. Liddle (London), pp. 481–7.

- Bond, B., 2002. The Unquiet Western Front: Britain’s role in literature and history (New York).

- Brandon, L., 2006. Art or Memorial? The forgotten history of Canada’s war art (Calgary).

- Burn, I., 1990. National Life and Landscapes(Sydney).

- Chouliaraki L., 2013. ‘The humanity of war: iconic photojournalism of the battlefield, 1914–2012’, Visual Communication, 12 (3), pp. 315–40. doi: 10.1177/1470357213484422

- Clark, A., 1961. The Donkeys (London).

- Crocker, T., 2015. The Christmas Truce: myth, memory, and the First World War (Lexington, Kentucky, US).

- Das, S., 2014. ‘Indian sepoy experience in Europe, 1914–1918: archive, language and feeling’, Twentieth Century British Hist, 25 (3), pp. 391–417. doi: 10.1093/tcbh/hwu033

- Duffy, C., & Roberts, D., 2014. The Christmas Truce (London).

- Dyer, G., 1995. The Missing of the Somme (London).

- Flothow, D., 2007. ‘Popular children’s literature and the memory of the First World War 1919–1939’, The Lion and the Unicorn, 31 (2), pp. 147–61. doi: 10.1353/uni.2007.0016

- Fussell, P., 1977. The Great War and Modern Memory (New York, US).

- Fromkin, D., 2004. Europe’s Lost Summer: who started the Great War in 1914 (London)

- Gerster, R., 1987. Big-noting: the heroic theme in Australian war writing (Carlton, Vic).

- Gough, P., 2010. A Terrible Beauty: British artists in the First World War (Bristol).

- Gough, P., 2018. Dead Ground (Bristol).

- Gregory, D., 2016. ‘The Natures of War’, Antipode, 48 (1), pp. 3–56. Hazard, P., 1983. Books, Children, and Men (Boston, MA, US)

- Hoffenberg, P. H., 2001. ‘Landscape, memory and the Australian war experience, 1915–18’, J Contemporary Hist, 36 (1), pp. 111–31. doi: 10.1177/002200940103600105

- Holbrook, C., 2014. ‘The role of nationalism in Australian war literature of the 1930s’, First World War Studies, 5 (2), pp. 213–31. doi: 10.1080/19475020.2014.913988

- Holbrook, C., 2016. ‘Are we brainwashing our children? The place of Anzac in Australian history’, Agora, 51 (4), pp. 16–22.

- Hutchison, M., 2018, 8 November. ‘Friday essay: how Australia’s war art scheme fed national mythologies of WW1’, The Conversation; https://theconversation.com/friday-essay-how-australias-war-art-scheme-fed-national-mythologies-of-ww1-106454.

- Hynes, S., 1991. A War Imagined: the First World War and English culture (New York, US).

- Inglis, K., 2008. Sacred Places: war memorials in the Australian landscape (Melbourne).

- Jorgensen, N., & Harrison-Lever, B., 2002/2014. In Flanders Fields (Freemantle).

- Keith, C., 2012. ‘Pilgrims in a toxic land: writing the trenches of the First World War’, French Literature Ser 39, pp. 85–99.

- Kerby, M., & Baguley, M., 2020. ‘Forging truths from facts: trauma, historicity and Australian Children’s picture books’, The Lion and the Unicorn, 44 (3), pp. 281–301. doi: 10.1353/uni.2020.0028

- Kerby, M, Baguley, M., & MacDonald, A., 2017a. ‘And the Band Played Waltzing Matilda: Australian picture books (1999–2016) and the First World War’, Children’s Literature in Education: an International Quarterly, 44 (4), pp. 91–109.

- Kerby, M., Baguley, M., MacDonald, A., & Lynch, Z., 2017b. ‘A war imagined: Gallipoli and the art of children’s picture books’, Australian Art Education, 38 (1), pp. 199–216.

- Kerby, M., Tuppurainen-Mason, E., & Baguley, M., 2017c. Voices from the Trenches (Brisbane).

- Kerby, M., Baguley, M., Lowien, N., & Ayre, K., 2019. ‘Australian not by blood, but by character: soldiers and refugees in Australian children’s picture books’, in The Palgrave handbook of artistic and cultural responses to war since 1914: the British Isles, the United States and Australasia, ed. M. Kerby, M., Baguley & J. McDonald (Cham, Switzerland), pp. 309–26.

- Kesler, T., 2017. ‘Celebrating poetic nonfiction picture books in classrooms’, The Reading Teacher, 70 (5), pp. 619–28. doi: 10.1002/trtr.1553

- Lake, M., 2010. ‘Introduction: What have you done for your country?’, in What’s Wrong with ANZAC?: The militarisation of Australian history, ed. M. Lake & H. Reynolds (Sydney), pp. 1–23.

- Littlewood, J., 1963. ‘Oh, What a Lovely War’, Theatre Workshop, Stratford East, London.

- Lowenthal, D., 1985. The Past is a Foreign Country (New York).

- Lowenthal, D., 1990. ‘Historic landscapes: indispensable hub, interdisciplinary orphan’, Landscape Res, 15 (2), pp. 27–9. doi: 10.1080/01426399008706313

- MacCallum-Stewart, E., 2007. ‘If they ask us why we died: Children’s literature and the First World War 1970–2005’, The Lion and the Unicorn, 31 (2), pp. 176–88. doi: 10.1353/uni.2007.0022

- McKenna, M., 2007, ‘Patriot act’, Australian Literary Rev, June 6, 2007’; https://honesthistory.net.au/wp/mckenna-mark-patriot-act/

- McKenna, M., & Ward, S., 2007. ‘It Was Really Moving, Mate: The Gallipoli pilgrimage and sentimental nationalism in Australia, Australian Hist Stud, 38 (129), pp. 141–51. doi: 10.1080/10314610708601236

- Mosse, G., 1990. Fallen Soldiers: reshaping the memory of the World Wars (New York).

- Nodelman, P., 1988. Word about Pictures: The narrative art of children’s picture books (Athens).

- O’Reilly, M., Eldridge, S., Tuppurainen-Mason, E., & Kerby, M., 2015. Boys in khaki (Brisbane).

- Pugsley, C., 2004. ‘Stories of Anzac’, in Gallipoli: Making History, ed. J. Macleod (London), pp. 102–26.

- Owen, W, & Impey, M., 2018. Dulce et Decorum Est (Strauss House Productions, York).

- Radford, R., 2007. Australian landscape painting 1850– 1950 (National Gallery of Australia, Canberra).

- Remarque, E., 1929. All Quiet On The Western Front (Boston, MA, US).

- Reynolds, D., 2014. The Long Shadow: the Great War and the twentieth century (London).

- Robinson, H., & Impey, M., 2014. The Christmas Truce: the place where peace was found. (Strauss House Productions, York).

- Robinson, H., & Impey, M., 2014. Where the Poppies Now Grow (Strauss House Productions, York).

- Robinson, H., and Impey, M., 2018. Peace Lily (Strauss House Productions, York).

- Roche, H., 2015. 2 December. ‘Exorcising the Great War: Britten’s War Requiem and Rudland’s Christmas Truce, Hist Today; https://www.historytoday.com/exorcising-great-war-brittens-war-requiem-and-rudlands-christmas-truce.

- Scates, B., 2006. Return to Gallipoli: aaking the battlefields of the Great War (Port Melbourne).

- Scheib, M, 2015. ‘Painting Anzac: a history of Australia’s official war art scheme of the First World War’, unpubl Univ of Sydney Ph.D. thesis,

- Sheffield, G., 2002. Forgotten Victory: the First World War: myths and realities (London).

- Sipe, L. R., 1998. ‘How picture books work: A semiotically framed theory of text – picture relationships, Children’s Literature in Education, 29 (2), pp. 97–108. doi: 10.1023/A:1022459009182

- Spiers, E., 2015. ‘The British centennial commemoration of the First World War’, Comillas J Int Relations, 2, pp. 73–85. doi: 10.14422/cir.i02.y2015.006

- Steiner, W., 1986. The Colours of Rhetoric (Chicago).

- Stephens, J., 1992. Language and Ideology in Children’s Fiction (London).

- Strachan, H., 2001. The First World War, Volume 1; To Arms (New York).

- Taylor, A. J. P., 1963. The First World War, an Illustrated History (London).

- The Great War, 1964. Imperial War Museum, the British Broadcasting Corporation, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and the Australian Broadcasting Commission.

- Thomson, A., 2019. ‘Popular Gallipoli history and the representation of Australian military manhood’, Hist Australia, 16 (3), pp. 518–33.

- Todman, D., 2005. The Great War: myth and memory (London).

- Trezise, T., 2001. ‘Unspeakable’, The Yale J of Criticism, 14 (1), pp. 39–66.

- Tribunella, E. L., 2010. Melancholia and Maturation: the use of trauma in American children’s literature (Knoxville, US).

- Tuan, Y., 1979. Landscapes of Fear (New York, US).

- Twomey, C., 2015. ‘Anzac Day: are we in danger of compassion fatigue’, The Conversation; https://theconversation.com/anzac-day-are-we-in-danger-of-compassion-fatigue-24735

- Ward, R., 1966. The Australian Legend (New York, US).

- Weir, B., 2007. ‘Degrees in nothingness: battlefield topography in the First World War’, Critical Quart, 49 (4), pp. 40–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8705.2007.00799.x

- Williams, J. F., 1995. The Quarantined Culture: Australian reactions to modernism 1913–1939 (New York, US).

- Willis, M., 1993. Illusions of Identity: the art of nation (Sydney).

- Wolff, L., 1958. In Flanders Fields: the 1917 campaign (New York, US).

- Worsley, H., 2010. ‘Children’s literature as implicit religion: the concept of grace unpacked’, Implicit Religion, 13(2), pp. 161–71. doi: 10.1558/imre.v13i2.161