ABSTRACT

This study adopts a sociocultural approach to examine the language socialisation of a lower age novice-newcomer recently arrived in a Finnish open day care centre. A mixed method approach combining ethnographic analysis and quantitative analysis has been used to analyse video-recordings. The results suggest that when educators recognise language novice-newcomer’s diverse needs and deploy thereby multimodal socialising strategies (i.e. verbal, gestural), the novice-newcomer’s language and interactive competences could ameliorate across time. Different from adults, the local children seem unconscious of the diverse needs of peers from diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds, which sets out challenges for educators in balancing recognition of diversity with equality.

Introduction

Adopting a sociocultural perspective of second language learning and socialisation (Vygotsky Citation1978), this study focuses on teacher–child and peer interactions to examine how the language novice-newcomer’s second language (L2) learning and interactional competences develop across time in a Finnish monolingual early childhood education classroom. An important body of literature has highlighted the crucial role of teacher–child interaction in supporting children’s language learning and development (Cekaite Citation2017; Degotardi Citation2017; Goble and Pianta Citation2017; Schwartz and Gorbatt Citation2017; Salminen et al. Citation2021). Particular attention has been placed on peer interaction to discuss the influences on children’s second language learning in multilingual contexts (Cekaite and Björk-Willén Citation2012; Blum-Kulka and Gorbatt Citation2014; Rydland, Grøver, and Lawrence Citation2014) and on the engagement of children in the peer culture of the classroom community (Blum-Kulka and Snow Citation2004; Björk-Willén Citation2016). Yet, empirical studies investigating lower age novice-newcomers’ (2–3-year-old toddlers) interactional processes with educators and peers in L2 learning in multicultural early childhood classroom settings are still limited. Particularly, some studies on peer interactions have documented the age effect and related peer skills as determinant factors in children’s language learning and development (Blum-Kulka and Gorbatt Citation2014; Rydland, Grøver, and Lawrence Citation2014; Schwartz and Gorbatt Citation2018; Foster, Burchinal, and Yazejian Citation2020; Wu, Lin, and Ni Citation2021). Adding to the knowledge of the lower age group’s L2 learning, specifically toddlers from linguistically and culturally diverse backgrounds, this study examines interaction patterns in a monolinguistic classroom environment where the novice-newcomer’s interactional processes with educators and peers are closely analysed.

Teacher–child interaction in second language classroom

An important objective of researching second language learning and socialisation is to figure out how learners become members of the target cultural community (Blum-Kulka and Snow Citation2004). Vygotsky (Citation1978) proposed that ‘learning awakens a variety of internal developmental processes that are able to operate only when the child is interacting with people in his environment and in cooperation with his peers’ (90). From this sociocultural perspective, the bulk of empirical research has suggested the crucial role of adult–child interaction and peer interaction in the classroom setting to create a ZPD (zone of proximal development), which is necessary for language learning and further development of the L2 learners (Blum-Kulka and Snow Citation2004; Blum-Kulka and Gorbatt Citation2014; Rydland, Grøver, and Lawrence Citation2014; Björk-Willén Citation2016; Cekaite Citation2017; Degotardi Citation2017; Schwartz and Gorbatt Citation2017, Citation2018). Adult–child interaction has been an important strand in investigating children’s L2 learning. Focusing on a two-way bilingual preschool in Israel, Schwartz and Gorbatt (Citation2017) analysed teachers’ language mediation strategies in scaffolding language learners L2 learning. It has been observed that frequently used strategies in promoting pre-schoolers’ L2 learning include teachers’ explicit requests for L2 usage, the bilingual teacher's direct translation for novices at their arrival, the teacher's concurrent L2 role modelling for student learners, and the mobilisation of peer student experts’ mediation. Blum-Kulka and Gorbatt (Citation2014) have demonstrated the scaffolding strategies of meta-linguistic ‘say’ rituals and repetition rituals deployed by teachers in novices’ L2 learning in early educational settings. These studies have mapped scaffolding strategies which teachers may mobilise in early institutional settings.

Peer interaction in second language classroom

Blum-Kulka and Snow (Citation2004) have identified two types of L2 learners, the language-novice and the language-expert. In line with the analytical framework proposed by Blum-Kulka and Snow (Citation2004), Schwartz and Gorbatt (Citation2018) have focused on young L2 experts’ sociolinguistic behaviour patterns in the bilingual classroom and found that L2 experts between the ages of 5 or 6 years old could ‘directly teach a new word and negotiate their novice peers’ understanding’ (362). Focused on two different early educational settings where children with diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds are in co-education in Swedish monolingual classrooms, Cekaite and Björk-Willén (Citation2012) have not only observed spontaneous corrective actions between peers in the use of lingua franca, including pronunciation, lexical choices and language choice, but also suggested the emergence of social stratification in the peer group where student language-experts affirm their higher position in using unmitigated corrective formats over their peer language-novices.

Studies investigating peer interaction in mixed-aged and same-aged classroom settings have indicated an age effect where younger children have significantly fewer peer interactions and in shorter duration as compared to older children (Wu, Lin, and Ni Citation2021). Focusing on children’s language and behavioural outcomes, Foster, Burchinal, and Yazejian (Citation2020) attributed the age effect to unequal peer skills. In immigrant novices’ L2 learning studies, Blum-Kulka and Gorbatt (Citation2014) identified four stages where young immigrant novices move progressively from ‘peripheral to full participation in the school’s social and academic activities’, namely ‘the phase of innocence,’ ‘shock and silence,’ ‘emergent non-verbal and verbal mutual attempts at communication’ and ‘interactional accomplishments achieved despite limited linguistic resources’ (172). Cekaite (Citation2007) demonstrated the process of an immigrant L2 novice as socialised into a competent L2 learner of the target language through imposing, negotiating and adjusting her self-selections in teacher-fronted classroom talk. Inspired by these longitudinal research findings, the present study extends knowledge of the L2 learners to a lower age child (32-month-old) recently adopted from an Asian country who is in co-education with local Finnish peers in a Finnish early childhood education and care (hereafter ECEC) monolingual classroom. To examine the novice-newcomer’s L2 learning, we focus on educators’ multimodal interactions with the children and the children’s peer interactions in classroom ‘micropractices’ (Goodwin Citation2000; Cekaite Citation2012) and discuss how the novice-newcomer’s language learning and interactional competences evolve across time.

According to Blum-Kulka and Gorbatt (Citation2014), ‘gaining full communicative (or pragmatic) competence in a second language entails a range of social, linguistic and pragmatic skills, including social aspects of language use, knowledge of the conversational skills of turn-taking and dialogicity’ (170). Cekaite (Citation2007) defines interactional competence as ‘participants’ knowledge of the interactional architecture of a specific discursive practice, including knowing how to configure a range of resources through which this practice is created’ (45). In this study, we examine the evolution of the novice-newcomer’s interactional competence from two aspects referring to the skills of configuring available resources in the immediate classroom environment to initiate interaction on one hand, and to the novice-newcomer’s capacity to interact with different agents (educators and peers) across time on the other.

The following two research questions are the focus of this study:

What are the observable interaction patterns in the novice-newcomer within the Finnish ECEC classroom?

How do teacher and peer interactions influence the novice-newcomer’s language learning and interactional competence?

Materials and methods

Materials

Setting, data collection, ethics, and participants

The present study is part of the project on Disentangling equality in multicultural settings: A sociolinguistic-ethnographic study of early childhood education classrooms in Finland (So-Equal). The data are collected by the first author in a Finnish open day care jointly operated by the city hall and the university. In this ECEC educational setting, children aged 2–5 are offered three hours of day care services two- or three-times per week. Though the open day care is not featured as multicultural and the medium of instruction is dominated by the monolingual language policy where Finnish is the lingua franca, some of the clients are from diverse linguistic and cultural background.

This study was approved by the director of the day care and written consent was obtained from all parents and educators, including preservice teachers in internship. After the project was approved by the director, the researcher contacted the teacher educators for information about the linguistic feature of participants in different groups. Based on this information, the group with a child who recently arrived in Finland was sampled for observation. Originally, the data collection was planned to be longitudinal for a duration of six months until the end of the school year. However, the force majeure of COVID-19 interrupted the video recording and reduced the collected data to a period of three months. Apart from the sessions with special arrangements (grandparents’ day for instance), a consistent observation of classroom practices such as children’s free play, circle time and mealtime were recorded for 40 h approximately. The teacher educator informed all children of the purpose of this research and the researcher’s presence next door behind the camera.

The focus child was a 32-month-old boy adopted from an Asian country who had arrived in Finland only two months prior to this research study. Data collection was permitted after his second session in the open day care. In the present study, the focused activity was mealtime where the small group (2–3 years olds) was separated from the big one (4–5 years olds) in two rooms. In contrast to free play activities, children’s physical mobility during mealtime was adjusted by an alarm clock. Accordingly, if some children had finished their snack earlier than the others, they should then patiently stay at the table until the alarm clock rings. Our observation shows that the presence of the alarm clock not only communicates the importance of discipline and patience to children, but also forms the time and space of language learning and socialisation for the novice-newcomer. Together with the focus child, a boy and a girl of the same age, and the three educators (two teacher educators and a nurse) were identified as main participants. The novice-newcomer’s interaction with peers and educators are of concern, since ‘the interactive organization of participation frameworks (is) a primordial locus for the constitution of human action, cognition and moral alignment’ (Goodwin Citation2007, 66), and since teacher–child interactions and peer interactions are suggested to be consequential in children’s learning and language socialisation (Cekaite and Björk-Willén Citation2012; Hamre et al. Citation2014; Björk-Willén Citation2016; Cekaite and Evaldsson Citation2017; Goble and Pianta Citation2017).

Methods

Unit of analysis

Van Lier (Citation1988) has argued that it is sufficient to analyse ‘active participation on the basis of turn taking’ (123). Cekaite (Citation2007) has emphasised that ‘students’ active participation is prompted through opportunities for self-selection’ (47). In line with these arguments, we code the collected video-recordings on the basis of turn-taking, which is defined here as the initiation of interaction, either by verbal communication, eye-gaze, gesture, or touch. Since there is no clear-cut definition of a turn unit (Van Lier Citation1988, 97), a turn is considered here as completed when the initiated topic has been replaced by another topic or has simply been ended. In the case of interruption, no new initiated interaction is counted when the topic is resumed. In this sense, our defined unit of analysis can be larger than a self-selection, in case that the self-selection registers into the ongoing topic. In other words, a unit of analysis is an initiation of interaction which is related to a singular topic development. For example, to attract attention, a sampled child initiates interaction by sticking out his tongue to make a funny noise. This initiation is coded as a unit of analysis, regardless of whether peers or educators react. If the initiated interaction is neglected or ignored by peers or educators, it is still labelled as a unit of analysis. If there is a reaction, and the initiated topic is resumed, it is considered within that same unit of analysis until another topic emerges.

Data processing and methods

On the basis of the unit of analysis, the researcher focused on the video recordings of 13 recorded mealtime sessions throughout a lapse of three months (about 260 min). Repeated video analysis with precision to seconds allowed for the labelling of 428 moments of interactions initiated by different actors engaging in the small group mealtime activities.

Quantitative analysis

In labelling the initiated interactions, the initiator of action counts not only because it consists of the baseline for labelling the unit of analysis, but it also unravels the interactional competence of the initiator. Cekaite (Citation2007) has demonstrated that the capacity to seize the right moment for self-selection is an important competence in a learner’s L2 learning process. The nature of initiated action (verbal, gestural, eye-gazing or touch) in addition to the length of verbal communication (units of sound, word, phrase, or sentences) are recorded as indices to examine the novice-newcomers’ linguistic investment across time in the micro-ecology of the classroom (Darvin and Norton Citation2021). Meanwhile, language learning is not independent from the sociocultural environment of the given society (Steffensen and Kramsch Citation2017). To map out the interactional processes in Finnish ECEC, the addressee of the initiated action is considered to understand the patterns of educators’ pedagogical practices towards the novice-newcomer in comparison to local children.

Referring to these indicators, the analysis of variance (ANOVA) is used to explore the patterns of interactions during the mealtime. The initiators of interactions are categorised into four groups of educators, focus child, peer boy and peer girl. The 13 sessions of observation are combined by month into three periods to explore the potential evolution of interaction patterns across time. Due to the requirement of ANOVA, the outcome variables of the addressees of the initiated interactions and language length are treated as continuous variables where the mean score is concerned. The key variables are described as follows (see ):

Table 1. Descriptive variables (Total = 428).

Qualitative analysis

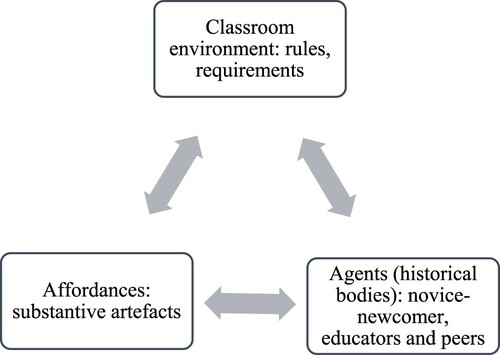

To shed light on how the educator-focus child-peer interactions in the micropractices of a classroom is related to the novice-newcomer’s language learning and socialisation, an ethnographic analysis of interactions is processed. The researchers screened the labelled 428 moments of initiated interactions. With deliberate considerations and discussions, the researchers have drawn on representative instances for in-depth analysis and illustration (Van Lier Citation1988; Cekaite Citation2007, Citation2012) (see example in ). Inspired by the ecological perspective of language learning, this study focuses on ‘the ecosystemic dynamics where agents pick up on the affordances and pressures of the environment, and where the environment changes as a result of agents’ behavior’ (Steffensen and Kramsch Citation2017, 7). Accordingly, we develop a schema indicating the interactive organisation which frames the language learning and socialisation of the novice-newcomer (see ). Here, the environment refers to the ECEC classroom consisting of a local ‘community of practices’ circumscribed to the national educational policy. Agents here are not only the ‘persons-in context’ but also historical bodies with historical trajectories (Scollon Citation2001; Darvin and Norton Citation2021). Affordances in our analysis are substantive artefacts in the classroom used for language learning.

Results

Throughout the three-month observation, mealtime is a significant social site for the under 3-year-old novice-newcomer to interact with other actors in a relatively peaceful classroom environment. As described earlier, the novice-newcomer started his open day care only recently and was not familiar with the routines. His participation is highly dependent on adults’ guidance, and he seems upset when physical closeness occurs with peers. To facilitate the novice-newcomer’s transition from family to ECEC institution, the adoptive mother was allowed to attend the first two sessions. This is also an occasion for teachers to get knowledge of the novice-newcomer’s trajectory and the family’s expectations.

Interaction types

Interactions in the classroom environment are consequential for second language learning (Duff Citation2014; Cekaite Citation2017). In this study, Finnish is not strictly a second language for the novice-newcomer but rather a second mother tongue. Results in show that with only rudimentary Finnish language skills, the novice-newcomer has preference to use verbal communication to engage interaction, and it represents 62% of his initiated interactions. Similarly, he frequently uses gestures such as pointing and handing, alone or accompanied by verbal engagement (60.7%) to initiate interaction. Compared with peers and educators, eye-gaze is predominantly used by the novice-newcomer for initiating interactions, although it is not his favourite means. In contrast, touch is mostly used by educators (90.5%), often in occasions of guiding, caring and imposing discipline (Cekaite Citation2016; Cekaite and Kvist Holm Citation2017). The high rate of interaction initiation (38.1%) indicates the novice-newcomer’s willingness to interact despite the new school culture, yet how his language proficiency and interactional skills evolve across time and how they are relevant to educators’ and peers’ practices needs clarification.

Table 2. Crosstabulation for initiator’s interaction types.

Patterns of interactions

The next step is to discern the patterns of interactions by cross-checking the initiators of interactions and the addressees. The analysis of frequency suggests that 59.4% (104 times) of educator-initiated interactions are addressed to the focus child, 13.1% (23 times) to the peer girl, 26.9% (47 times) to the peer boy and once (0.6%) with no clear addressee. For the peer girl, 76.5% (52 times) of her initiated interactions are addressed to educators, 4.4% (3 times) to the focus child, 5.9% (4 times) to other peers and 13.2% (9 times) with no clear addressees. Among the interactions initiated by the peer boy, 54.5% (12 times) are addressed to educators, 9.1% (2 times) to the focus child, 27.3% (6 times) to other peers and 9.1% (2 times) with no clear addressees. Among the interactions initiated by the focus child, 79.1% (129 times) are addressed to educators, 0.6% (once) respectively to the peer boy and peer girl, 2.5% (4 times) to other peers and 17.2% (28 times) with no clear addressees. Overall, three patterns of interactions are discernible. First, educators accord considerable attention to the novice-newcomer during the mealtime interactive activities. Second, scarce interactions are found between peers and the novice-newcomer and vice versa. Third, in the case of educator-younger children formation, educators are the main addressees of children-initiated interactions, and peer interactions are marginal.

Scaffolding the novice-newcomer’s language learning in teacher–child interaction

A close examination of interactions suggests that most of the initiated interactions are related to routines during the mealtime for the small group. For instance, children’s requests for help and assistance, educators’ interventions for queuing, disinfecting hands, guiding to take lunchboxes and bottles from the fridge, helping to take a seat and opening food and drink containers, etc. When all activities related to routines are accomplished and when educators sit at the same table with children, chattering will accompany the snack-taking which lasts for about 20 min and is regulated by an alarm clock. For both occasions of routine and chattering, it is frequent that teachers employ an ‘interactive organization of apprenticeship’ (Goodwin Citation2007) in engaging the novice-newcomer in language learning and the practices of the classroom, as suggested in . In our case study, the imperative of linguistic integration of the dominant society goes on the same line with the expectation of the focus child’s family, and it forms the local environment which frames teachers’ practices towards the novice-newcomer.Footnote1 To support the novice-newcomer’s language learning and socialisation, affordances such as pictures on the lunchbox, bottle, peers’ food, etc. are commonly used by teachers by means of naming in the first sessions and progressively recycled by the novice-newcomer.

In Excerpt 1(illustrated in ), Teacher 1 moves the focus child’s empty smoothie bag in front of him and points at the pictures on it for naming, the focus child repeats spontaneously. The language learning and socialisation goes smoothly since no discrepancy is there between the requirements of the environment and the intention of the historical bodies.

(February) Excerpt 12 Participants: Teacher 1, nurse, focus child, the peer boy, the peer girl and two other children.

Naming is the mediation strategy that Teacher 1 frequently uses to scaffold the focus child’s L2 learning. In Excerpt 1, Teacher 1 has appropriated an affordance familiar to the focus child (his smoothie bag, line 1) for naming. This verbal initiation for language learning immediately gets the focus child’s attention. Teacher 1 and the focus child’s joint pointing to the picture on the smoothie bag (lines 1–2) has embodied the participants ‘interactive organization’ (Goodwin Citation2007) of language learning. It is evident that Teacher 1 has ‘downplayed the asymmetries in knowledge’ (Cekaite and Björk-Willén Citation2012) with a mitigated format of ‘nodding’ and ‘repeating’ the word ‘mango’ when the focus child fails to pronounce it (lines 4–5); and the strategy of adding ‘yes’ right after repeating ‘mango’ to emphasise the repair has subtly avoided any explicit correction of the focus child’s mispronunciation (line 5). When the focus child still struggles with the repair, instead of insisting on the repair outcome, Teacher 1 initiates an explicative talk with the neighbouring nurse to explain the difficulty of the target language, rather than questioning the focus child’s L2 proficiency (line 7). In reaction to Teacher 1’s initiation, the nurse has extended a compliment on the focus child’s L2 learning (line 8) which has been confirmed by Teacher 1 in return (line 10). Seemingly, adults’ talk concerning the focus child has not been ignored by the latter, since he has effectively participated with his embodied gesture of face direction, peeping and eye-gaze (lines 6–9).

It has been observed that the novice-newcomer and educators’ interactions for language learning progressively change the local ecology of the classroom. In December and January, when teachers were intentionally engaging the novice-newcomer in language learning by naming artefacts, other children assisted without intervention. Yet in the above excerpt from February, the conversation between the teacher and the nurse (line 7, 8 and 10) praising the focus child’s competence in language learning has stimulated the peer girl who has self-selected to engage in similar practice (line 11).

The language use of the novice-newcomer

The descriptive analysis of interaction types in shows the novice-newcomer’s investment in verbal communication and his willingness to learn and practice, as expected by his adoptive family. However, these data inform us neither of the disparity of the initiators’ language proficiency nor its variation across time. To these concerns, a two-way ANOVA analysis is used to test simultaneously the effect of initiator and time on language proficiency as well as their interaction effect. Language proficiency is measured here by the length of language use (see ).

Strong evidence indicates initiators’ difference in language proficiency, F (3, 389) = 33. 36, p < .000,Footnote2 and the effect size is large (partial eta squared = .21) (Pallant Citation2011, 210). Post-hoc comparisons using the Tukey HSD test show that the novice-newcomer’s language proficiency (M = 2.20, SD = 1.01) is significantly lower than that of educators (M = 3.47, SD = 1.81) and the peer girl (M = 4.42, SD = 1.33), in reference to the coding for the length of language use (). There is evidence that initiators’ language proficiency varies across time F (5, 389) = 2. 95, p < .000, while the interaction effect size is less than medium. To determine which initiator’s language proficiency significantly progresses across time, we split the sample by initiator of interactions to proceed a one-way ANOVA for each subgroup of initiators. Results suggest a significant evolution of the novice-newcomer’s language proficiency across time F (2, 152) = 27. 71, p < .000. The mean of the length of language use in the period three (February and March, M = 2.70, SD = 0.79) is significantly higher than the other two periods (December M = 1.31, SD = 0.75 vs January M = 1.76, SD = 0.98) at the 0.05 level, suggesting that the novice-newcomer’s language use has evolved from units of sound to words and phrases.

The novice-newcomer’s emerging interactional competence

In Excerpt 2, Teacher 1 and the nurse show appreciation to a big sister’s act of helping her little brother to drink juice.

(February) Excerpt 2 Participants: Teacher 1, nurse, focus child, the peer boy, the peer girl and two other children.

The peer girl has self-selected and started to talk about her siblings (line 1). The novice-newcomer has assisted the multiparty talk between educators and the peer girl about family members, yet he cannot come up with coherent turn-taking (Mehan Citation1979). Instead, he self-selects to interrupt the ongoing talk by using a formulaic sentence ‘what this is’ (line 7) together with a face direction gesture toward Teacher 1 to embody his request. Obviously, he has succeeded in affirming his turn-taking despite the limited language proficiency preventing him from resuming a cohesive thematic with ongoing talk (Cekaite Citation2007). The interactional competence of the novice-newcomer is plausible, not only because of his self-selection to interact, but he also recycles the teacher’s mediation strategy of naming which has legitimised his intervention, for it has not been considered as impolite but immediately received by teachers as a signal of willingness for language learning. In this example, the novice-newcomer’s self-selection with a non-relevant thematic is immediately recognised and responded by Teacher 1 (line 9 and 10), although the peer girl’s ongoing talking has simply been covered by the focus child’s verbal intervention (line 7).

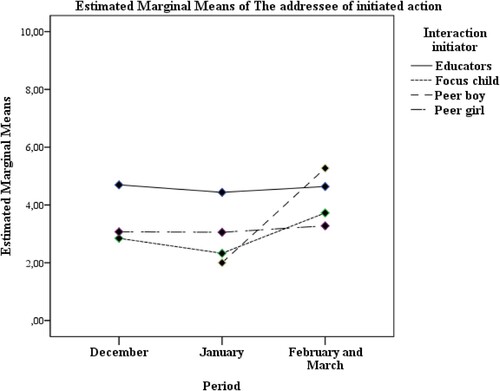

Evolution of interactional competences: interaction with teacher

As suggested in (the line representing the focus child as interaction initiator), if the novice-newcomer was used to repeating words and excerpts of sentences in teacher-led language learning in the first two periods (the estimated marginal means of the addressees are between 1 and 3, meaning educators are his main addressees according to the coding in ), he had then started to capture and repeat instinctively the words used by peer neighbours and to recycle teachers’ roles of naming artefacts. The focus child seemed to enjoy the experience of language learning especially from the third period (the estimated marginal means of the addressees are higher than 3, which means the focus child extends his addressees beyond educators). With these findings, we will focus on the relationship between initiators and addressees of interactions in order to discuss how they are related to the novice-newcomer’s interactional competences.

In Excerpt 3, almost all children of the small group have settled for snack, Teacher 1 stands next to the novice-newcomer.

(March) Excerpt 3 Participants: Teacher 1, teacher 2, focus child, the peer boy, and other four children.

In this example, Teacher 1 has checked up and made sure that every child has their snack and sits properly to eat. When she walks next to the novice-newcomer, the latter has spontaneously self-selected to initiate his familiarised practice of naming artefacts and to show Teacher 1 his knowledge in the target language (line 1). Compared with Excerpt 2, it is evident that the novice-newcomer is more flexible in determining the right transition point for self-selection (Cekaite Citation2007). He has not interrupted Teacher 1’s routine activity but waits for the empty slot to initiate interaction. We can see that the novice-newcomer’s interactional competence is evolving. In Line 7, he has succeeded in achieving his request for aid to open the smoothie bag with a single word followed by a falling intonation. Teacher 1 has understood his intention and confirmed by repeating his request in a rising intonation (line 8) which has received a positive response from the focus child (line 9). Teacher 1 is persistent in scaffolding the novice-newcomer’s L2 learning. When Teacher 1 asks him to name the mandarin (line 2), he is only capable of pronouncing a phoneme (line 3). However, the novice-newcomer can capture the word from Teacher 1’s formulaic question (line 4) and repeats it easily (line 5). It is obvious that the novice-newcomer’s language skill is ameliorating in contrast to the situation encountered one month ago (excerpt 1) when he had extreme difficulty in repeating the word ‘mango’.

Evolution of interactional competence: extending interaction to peers

The quantitative analysis has indicated the novice-newcomer’s increasing interactional competence in the sense that he has expanded his addressees beyond the educators. Strong evidence suggests a significant variation of the interaction patterns across time F (2, 417) = 11. 11, p < .000, the effect size is medium (partial eta squared = .05). There is also evidence suggesting the interaction effect between initiators of interactions and period F (5, 417) = 3.52, p < .05, the effect size was slightly lower than medium (partial eta squared = .04). To determine the initiator whose interaction patterns are significantly related to the progression of time, the sample has been split by initiators of interactions to proceed a one-way ANOVA for each subgroup of initiators. Evidence suggests that the interaction patterns initiated by the focus child F (2, 160) = 6.19, p < .05, and by the peer boy F (1, 20) = 9.64, p < .05, vary across time, while no significant evidence is found in the interaction patterns across time initiated by educators and peer girl. Post-hoc comparisons using the Tukey HSD test suggest that the mean score for the focus child in the third period (February and March, M = 3.73, SD = 2.88) is significantly higher than the second period (January, M = 2.33, SD = 1.87), indicating the increasing interactional competence of the novice-newcomer by expanding his addressees beyond the educators. Similar progression is found for the peer boy.

On the basis of the interaction logs of the video-recordings, the peer boy’s increasing interactions with peers are highly related to the focus child’s activity. From February, the peer boy’s reaction to the novice-newcomer’s naming and repeating way of language learning has shifted from observation to active verbal reactions. Initially, he finds the novice-newcomer’s repeated naming of the same artefact (gingerbread, for instance) funny and has made the word-recycling situation into a funny scenario by playing with the tongue to make funny noise (session 11). In the following session, the peer boy starts to recycle the novice-newcomer’s word.

(February) Excerpt 4 Participants: Teacher 1, nurse, focus child, the peer boy, the peer girl and other four children.

In Excerpt 4, configuring the coffee drinking action of Teacher 1, the focus child has self-selected to reproduce the language learning activity of naming (‘coffee’) (line 1) and has extended the word to the short phrase of ‘drink coffee’ to resume the attention received from the nurse (lines 3). When he feels that the nurse’s reaction is not as gratifying as he had expected, he starts to repeat constantly the same word and phrase (line 5, 7, 9). Triggered by the focus child’s initiated dense verbal reiterations (line 9), the peer boy has engaged in the activity by marking a gestural face-direction to Teacher 1 (line 10) and by recycling the focus child’s utterance of ‘drink coffee’ (line 13) which received the same vocal reaction from the focus child (line 14). However, as Cekaite and Björk-Willén (Citation2012) suggested ‘even at a young age, the children focus on appropriate language use in the flow of talk-in-interaction during their mundane activities’ (185), the peer boy has extended a conversation around the topic of ‘drink coffee’ with another girl sitting face to face with him (line 15–16), the girl has obviously picked up on the focus child’s inappropriate language use of ‘drink coffee’ by stating ‘don’t drink coffee yet’ (line 16) at this age. The social norms related to coffee drinking are embedded in this peer conversation, though how they are received by the novice-newcomer are ignored since he has withdrawn from this conversation by leaving the table.

Discussion

The findings suggest that educators’ recognition of diverse needs and responsive teaching can create a safe environment for the novice-newcomer who at first seemed upset and at a loss in the first sessions and thereby effectively encourage him to confidently take turns and affirm his interactions (see Excerpts 2 and 4). This supports the arguments put forward by Goodwin (Citation2007) and Cekaite (Citation2007) that the positive and supportive classroom ecology and the deliberate use of affordances in the classroom contribute to the novice-newcomer’s language learning and interactive competences across time.

Peer interactions engaging the novice-newcomer are scarce. In contrast to findings concluded in a Swedish preschool classroom where peers with limited languages resources and experiences in Swedish succeed in making friends and achieving intersubjectivity (Björk-Willén Citation2016), this study fails to find substantial verbal interactions between the novice-newcomer and other children. This may be explained by the lower age of our research subjects (3-year-old and younger aged children) and by the large gap of language proficiency, which prevents the novice-newcomer from benefiting of peer interactions (Blum-Kulka and Gorbatt Citation2014; Rydland, Grøver, and Lawrence Citation2014; Cekaite Citation2017).

Ethnographic analyses of classroom interactions suggest that lower age children in the small group have no awareness of how to scaffold verbal communication with the novice-newcomer whose language skills are still very limited. The briefness of the novice-newcomer and peer’s verbal interactions is understandable in the sense that ‘a child perceives other human beings as intentional agents similar to him-or herself’ (Vygotsky Citation1986, xiii). Hence, when the peer initiated verbal interaction receives no responses from the novice-newcomer, the interaction simply terminates. In contrast, the novice-newcomer’s verbal interactions are highly supported by the scaffolding of teachers which stimulate in return the novice-newcomer’s willingness to interact with them (Rydland, Grøver, and Lawrence Citation2014). Clearly, teacher-child interactions consist of a significant social site for the lower age novice-newcomer’s language learning and socialisation.

However, in our focused ECEC intercultural educational setting, knowing how to reconcile the diverse needs of children including the novice-newcomer and the local children (often considered as competent and thus intentionally neglected) seems challenging for teachers. Confronted with the novice-newcomer’s consistent request for attention and the other children’s competitive needs for attention (Excerpts 1 and 2), teachers have accorded priority to the novice-newcomer to support his L2 learning and socialisation. At the same time, the local children’s equal request for attention is inevitably neglected (Excerpts 1 and 2). In the Finnish context, Dervin (Citation2013) is critical of practices that consider only the Other as ‘diverse’, arguing that it could result in teachers’ blindness with regard to local children’s diverse needs. The present study suggests that promoting social justice for each child’s feeling of being equally valued requires educators’ critical reflections of their everyday practices in the classroom.

Conclusion

A mixed method approach has been used to analyse video recordings collected in a Finnish open day care to study the language socialisation of a lower age novice-newcomer recently adopted from a culturally and linguistically diverse background. Based on the initiated multimodal interactions of verbal communication, gesture, eye-gaze and touch, this study has explored the patterns of interactions in the micropractices of a classroom and their relationship with the lower age novice-newcomer’s language learning and interactional competences. The study finds that teachers’ educational practices showcase the recognition of the cultural and linguistic diversity of the novice-newcomer, not by underlining his diverse background but with constant responsive teaching to his diverse needs. However, teachers encounter challenges in the micropractices of classrooms. In the quantitative analysis, there is evidence that educators show particular concern for the novice-newcomer recently adopted from a culturally and linguistically diverse background, while other students do not get similar attention. There is also evidence that children do not significantly differ in terms of their needs of attention from adults, because adults are the primary addressees in case of interactions.

Although an important part of our data suggests the limited benefits from peers’ interactions for the lower age novice-newcomer, peer interactions start to emerge across time. As showcased in Excerpt 4, peers are engaged in the interactional network initiated by and around the novice-newcomer. These competent language speakers have extended the novice-newcomer’s topic of ‘drinking coffee’ to a higher level of norms and values embedded in the society. Further evidence is not available in this research due to the sudden arrival of COVID-19. However, inspired by this emerging case, we contend that for teachers to practice social justice in the intercultural education context engaging lower age children, it is important to seize all opportunities that encourage peer interactions and make them an important social site for the novice-newcomer’s language learning and socialisation.

Transcription conventions

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their suggestions and all the children and their parents, and educators in the participating open day care for making this study possible. We would like to thank Leah Luedtke for her language editing and Wu Yuliang for his technique support of making the illustrative photo anonymous.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 During the first two sessions, Teacher 1 communicates often with the novice-newcomer’s mother about his trajectory, the current family environment, the expectations of parents and the difficulties encountered by the newly formed family.

2 The assumption of homogeneity of variance is not met due to the unequal size of compared groups. However, the satisfactory results performed by Welch for the robust tests of equality of means give basis to ANOVA proceedings.

References

- Björk-Willén, P. 2016. “Peer Collaboration in Front of Two Alphabet Charts.” In Friendship and Peer Culture in Multilingual Settings, edited by M. Theobald, 143–169. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Blum-Kulka, S., and N. Gorbatt. 2014. ““Say Princess”; The Challenges and Affordances of Young Hebrew L2 Novices’ Interaction with Their Peers.” In Children’s Peer Talk: Learning from Each Other, edited by A. Cekaite Thunqvist, S. Blum-Kulka, V. Grøver Aukrust, and E. Teubal, 169–193. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Blum-Kulka, S., and C. E. Snow. 2004. “Introduction: The Potential of Peer Talk.” Discourse Studies 6 (3): 291–306.

- Cekaite, A. 2007. “A Child's Development of Interactional Competence in a Swedish L2 Classroom.” The Modern Language Journal 91 (1): 45–62.

- Cekaite, A. 2012. “Affective Stances in Teacher-novice Student Interactions: Language, Embodiment, and Willingness to Learn in a Swedish Primary Classroom.” Language in Society 41 (5): 641–670.

- Cekaite, A. 2016. “Touch as Social Control: Haptic Organization of Attention in Adult–Child Interactions.” Journal of Pragmatics 92: 30–42.

- Cekaite, A. 2017. “What Makes a Child a Good Language Learner? Interactional Competence, Identity, and Immersion in a Swedish Classroom.” Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 37: 45–61. doi:10.1017/S0267190517000046.

- Cekaite, A., and P. Björk-Willén. 2012. “Peer Group Interactions in Multilingual Educational Settings: Co-Constructing Social Order and Norms for Language use.” International Journal of Bilingualism 17 (2): 174–188.

- Cekaite, A., and A. C. Evaldsson. 2017. “Language Policies in Play: Learning Ecologies in Multilingual Preschool Interactions among Peers and Teachers.” Multilingua 36 (4): 451–475.

- Cekaite, A., and M. Kvist Holm. 2017. “The Comforting Touch: Tactile Intimacy and Talk in Managing Children’s Distress.” Research on Language and Social Interaction 50 (2): 109–127.

- Darvin, R., and B. Norton. 2021. “Investment and Motivation in Language Learning: What's the Difference?” Language Teaching, 1–12. doi:10.1017/S0261444821000057.

- Degotardi, S. 2017. “Joint Attention in Infant-Toddler Early Childhood Programs: Its Dynamics and Potential for Collaborative Learning.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 18 (4): 409–421.

- Dervin, F. 2013. “Towards Post-Intercultural Education in Finland.” In Oppiminen ja pedagogiset käytännöt varhaiskasvatuksesta perusopetukseen, edited by K. Pyhältö, and E. Hujala, 19–29. Helsinki: OPH.

- Duff, P. 2014. “Case Study Research on Language use and Learning.” Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 34: 233–255.

- Foster, T. J., M. Burchinal, and N. Yazejian. 2020. “The Relation Between Classroom age Composition and Children’s Language and Behavioral Outcomes: Examining Peer Effects.” Child Development 91 (6): 2103–2122.

- Goble, P., and R. C. Pianta. 2017. “Teacher–Child Interactions in Free Choice and Teacher-Directed Activity Settings: Prediction to School Readiness.” Early Education and Development 28 (8): 1035–1051.

- Goodwin, C. 2000. “Action and Embodiment Within Situated Human Interaction.” Journal of Pragmatics 32 (10): 1489–1522.

- Goodwin, C. 2007. “Participation, Stance and Affect in the Organization of Activities.” Discourse & Society 18 (1): 53–73.

- Hamre, B., B. Hatfield, R. Pianta, and F. Jamil. 2014. “Evidence for General and Domain-Specific Elements of Teacher–Child Interactions: Associations with Preschool Children's Development.” Child Development 85 (3): 1257–1274.

- Mehan, H. 1979. Learning Lessons: The Social Organization of Classroom Behavior. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Pallant, J. 2011. SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using SPSS. 4th ed. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin.

- Rydland, V., V. Grøver, and J. Lawrence. 2014. “The Potentials and Challenges of Learning Words from Peers in Preschool.” In Children’s Peer Talk: Learning from Each Other, edited by A. Cekaite, S. Blum-Kulka, V. Grøver, and E. Teubal, 214–235. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Salminen, J., H. Muhonen, J. Cadima, V. Pagani, and M. K. Lerkkanen. 2021. “Scaffolding Patterns of Dialogic Exchange in Toddler Classrooms.” Learning, Culture and Social Interaction 28: 100489.

- Schwartz, M., and N. Gorbatt. 2017. ““There is No Need for Translation: She Understands”: Teachers’ Mediation Strategies in a Bilingual Preschool Classroom.” The Modern Language Journal 101 (1): 143–162.

- Schwartz, M., and N. Gorbatt. 2018. “The Role of Language Experts in Novices’ Language Acquisition and Socialization: Insights from an Arabic-Hebrew Speaking Preschool in Israel.” In Preschool Bilingual Education, edited by M. Schwartz, 343–365. Cham: Springer.

- Scollon, R. 2001. “Action and Text: Towards an Integrated Understanding of the Place of Text in Social (Inter) Action, Mediated Discourse Analysis and the Problem of Social Action.” Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis 113: 139–183.

- Steffensen, S. V., and C. Kramsch. 2017. “The Ecology of Second Language Acquisition and Socialization.” In Language Socialization, Encyclopedia of Language and Education. 3rd ed., edited by P. A. Duff and S. May, 17–32. Cham: Springer International Publishing AG.

- Van Lier, L. 1988. The Classroom and the Language Learner: Ethnography and Second-Language Classroom Research. London: Longman.

- Vygotsky, L. S. 1978. Mind in Society: Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Vygotsky, L. S. 1986. Thought and Language. Translated by A. Kozulin. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Wu, J., W. Lin, and L. Ni. 2021. “Peer Interaction Patterns in Mixed-age and Same-age Chinese Kindergarten Classrooms: An Observation-Based Analysis.” Early Education and Development. doi:10.1080/10409289.2021.1909262.