ABSTRACT

This paper examines the issue of migration control in Malaysia. Despite the fact that the majority of the world’s migratory movements are between countries in the Global South, the dominant focus of research on migration control has tended to be liberal democracies of the Global North. Here, focussing on a country which is a major destination for migrants in Southeast Asia, this paper examines the varied policies enacted by the Malaysian government in an effort to decrease the number of undocumented foreign workers. As Malaysia is known for its frequent migration policy shifts, this paper traces the many twists and turns in Malaysian policy in the period from 2011 to 2019. In doing so, the paper seeks to help build a better understanding of the complex and sometimes contradictory tools states use in attempting to manage migration. Here I find that some patterns emerge from Malaysia’s use of a wide variety of policy instruments to reduce its population of undocumented foreign workers, but that ultimately these must be placed in the context of the overall economic reliance of Malaysia on foreign labour and its turbulent policies.

It is a common observation of migration policy that states are not particularly adept at consistently controlling and regulating international migration (Cornelius Citation2004). Such an observation, often referred to as the ‘gap’ between policy and practice (Czaika and De Haas Citation2013), has highlighted both that states that might be restrictionist in rhetoric and public posturing, ending up home to significant populations of migrants (Joppke Citation1998), and that migration policies end up being much less successful at controlling migration than intended (Castles Citation2004a; Boswell Citation2007). Such ‘gaps’ have been blamed on contradictions inherent within ‘liberalness’ of liberal states (Hollifield Citation2006; Joppke Citation1998), the influence of clientelist political agendas (Freeman Citation1995), and institutional constraints provided by state and supra-state entities (Guiraudon Citation2012).

Here, by looking at the example of Malaysia’s attempts to govern and control its population of ‘foreign workers’ (as it terms its temporary migrant labour force), this paper examines two particular shortcomings of this portrayal. First, despite the fact that the largest migration movements are between countries in the Global South, research on migration control has disproportionately focussed on the Global North (Natter Citation2018). Our understanding of how states govern and control migration therefore tends to assume particular types of movements within a limited range of economic and state models (see Adamson and Tsourapas Citation2019). In this context, migration outcomes are often explained simply by reference to a state’s ‘liberalness’ (Joppke Citation1998; Hollifield Citation2006) or administrative capacity (Adamson and Tsourapas Citation2019) rather than the actual policies that have been promulgated. Secondly, many of these appraisals of the failure of migration policy ‘have a tendency to speak of immigration policy and politics writ large’ (Freeman Citation2006, 228) without much overt examination of the actual policies (or practices; see Bonjour Citation2011) that regulate migration.

Malaysia is a compelling context in which to look at processes of managing foreign workers considering its importance as a destination for migrant workers within Asian. Possessing both wide latitude to make decisions and relatively effective state capacity and enforcement mechanisms, Malaysia largely avoids the restraints faced by liberal democratic states and thus in theory should not face the same challenges in managing and controlling migration. As this article will discuss, Malaysia has implemented a raft of policies designed to regulate the presence of undocumented individuals. Yet Malaysia continues to have a large number of both documented and undocumented foreign workers. Alongside the estimated 1.8–3 million documented foreign workers in Malaysia (Loh et al. Citation2019), anywhere from 1.46 million (Loh et al. Citation2019) to 4.6 million (Low Citation2017) are estimated to be ‘illegal’.

This paper contends that the answer to this apparent contradiction lies in looking beyond the nature of the Malaysian regime to a more detailed examination of both the content of specific policies and the change in policies over time. Given the opacity of the Malaysian regime, it is impossible to know the motivations for all these sudden changes – which have been dubbed ‘engimatic’ (Nah Citation2011, 4) and ‘ad-hoc’ (Loh et al. Citation2019). However, although it has been a clearly stated goal of the government to rid the country of undocumented migrants (Yusof and Muhamading Citation2018), it has failed to do so despite its many policy initiatives. Here, I look beyond the common notion of policy ‘failure’ (Castles Citation2004b) in migration policy, as such conceptualisations tend to lead to an overly narrow sense of both policy (seeing it as inherently cohesive and unified) and failure (narrowly defined in relation to the purported policy aims). Rather than attempting to disentangle what Malaysia was ‘really’ trying to achieve through its migration policymaking, it is important to look to the tools used as Malaysia has sought to govern and control migration. Although certain policy patterns can be identified in how it manages undocumented foreign workers, these take place in the context of a state which has, overall, continued to promote migration as a key part of its economy.

Additionally, this paper argues the variety of policies deployed by the Malaysian government reveals that concept of ‘control’ within migration remains slippery. If ‘migration policy is seen to revolve around the walls that states build and how wide they open the small doors in these walls’ (Geddes Citation2012, 96), having both programmes that deport and those that regularise being seen as steps to ‘control’ migration highlights the complexity of this term. Therefore, examining the series of policies put forth by the Malaysian government as they rotated through policies designed to alternately regularise, punish and promote the voluntary return of foreign workers reveals that Malaysia was unable to either entirely control migration or find a clear policy path for achieving control.

The paper looks at the period from 1 August 2011, when Malaysia began the large, comprehensive immigration programme known as 6P, through mid-2019. Drawing upon an extensive review of press stories about migration control, it puts together an overview of the multiple policy directions pursued by the Malaysian government during this period. The next section provides an overview of the theory and literature on migration control before turning to the particularities of the Malaysian context, the methods used in this study and, finally, the findings of the research.

Policy and the ‘control’ of migration

One of the common features of research about migration policy has been the pervasive gap between the goals of migration policy and the measured outcomes (Hollifield, Martin, and Orrenius Citation2014). This has been explained in part by the fact that a number of interest groups influence policy (Freeman Citation1995) or that various institutions such as the courts, constitutions, or human rights agreements limit the capacity of governments to regulate migration with a free hand (Joppke Citation1998; Guiraudon Citation2012). In other words, these analyses assume that if states had a freer hand in regulating migration, there would ultimately be fewer migrants.

First, as discussed above, the assumption that ‘only liberal states are plagued by the problem of unwanted immigration’ (Joppke Citation1998, 269) has limited our understanding of the complexity of migration control. For example, one of the pre-eminent edited volumes on migration management and control does not use any examples from the Global South, and has only one chapter (of 14) devoted to countries in Asia (Hollifield, Martin, and Orrenius Citation2014). Therefore, many of these analyses are based on the assumption that the states in question are both liberal and democratic – that a wide variety of interest groups have input into policymaking procedures and that rights institutions are a significant break in the actions of national governments, which is clearly not true in all contexts.

However, it should be noted that such claims are not universal. Research from South America has suggested that liberalness can indeed extend from political systems to immigration policy (Arcarazo and Freier Citation2015). Within Africa, research has highlighted the complex interactions between migration (both inward and outward) and state development and formation (Vigneswaran and Quirk Citation2015). In the Asian context, important work has been done on the significant level of state involvement in outmigration programmes in the Philippines (Rodriguez Citation2010) and China (Xiang Citation2012). There has also been increasing focus on the management of temporary worker programmes in Asia (Surak Citation2018) as well as longstanding interest in the roles played by brokerage networks in organising migration (Lindquist Citation2012, Citation2017; McKeown Citation2008, Citation2012). In response to changing movement patterns there is also a growing body of research on how states have managed their new roles as net receivers of migration (Chalamwong, Meepien, and Hongprayoon Citation2012; Paitoonpong and Chalamwong Citation2012) as well as the role played by regional organisations like the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) (Bal and Gerard Citation2018).

Emerging research from a wider variety of political contexts has shown that countries which are not liberal democracies also grapple with issues of migration governance and control. Authoritarian states are also influenced by political, demographic and economic conditions and interests in shaping migration policy (Shin Citation2017). Even Gulf countries, which often typify aggressive migration control, have not been able to immediately and unilaterally alter migration control processes but have had to work through existing vested interests, including those of private migration brokers (Thiollet Citation2019).

Beyond the focus on Western liberal democracies, another limitation of this literature on migration control has been its tendency to ignore the specific policies which target migration management and control. Migration policy failure is couched in terms of economic trends, political structures and dynamics, and other aspects of states (Castles Citation2004b), but not policy more specifically. This is important as often the literature on migration control tends to avoid looking at policy and instead sees migration control as almost an inherent attribute of the state, rather than the product of a set of government policies. This is clearly present, for example, in Hollifield’s conceptualisation of a ‘migration state’ (Hollifield Citation2006) or in Joppke’s presentation of the inability to control migration as simply an inherent feature of the liberal state (Joppke Citation1998). There is, therefore, a need to look beyond the regime typology and see how migration policies are actually made and implemented (Natter Citation2018), as such research has long revealed intricate complexity and contradictions as states work to regulate migration (see for example Calavita Citation1992). Malaysia, like many states, faces issues of implementation as well as competition amongst competing branches and interests. Malaysian migration policy has been under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Home Affairs, a department run by the Deputy Prime Minister, yet a number of agencies are involved with various aspects of the migration process (Harkins Citation2016).

Taking the example of guestworker schemes, which is essentially what Malaysia’s foreign worker scheme is, there is a large amount of complexity and policy choice to be made. Guestworker schemes often share a common focus on temporariness, employer sponsorship and an extensive use of non-state actors (see Anderson and Franck Citation2019). Yet even within that framework, states may design their programmes in different ways (see for example Surak Citation2013; Kaur Citation2010) with different rules about fees, how brokers are involved, how wages are set, the economic sectors in which migrants may work, and which government departments supervise which aspects of the programme. Moreover, there is not necessarily a ‘right’ answer when it comes to formulating policy. A report on best practices by the International Labor Organization (ILO) noted that while one can identify some general trends, what is successful in one context might not always be ideal in another (Abella Citation2006).

Discussions of migration policy are especially relevant in the context of Malaysia’s foreign worker and guestworker programmes more broadly. As programmes for temporary migration, they are designed, from the outset, to be ‘managed’ migration programmes – setting narrow parameters in which migrants operate. These parameters are, furthermore, often determined by the perceived economic value of the migrant to the state, creating a ‘hierarchy of rights’ based on their expected contribution to the state (Nah Citation2012). Through the combination of specific legal frameworks and the extensive delegation of authority to private actors who are given broad latitude to control the lives of migrants, the state is able to supervise and regulate migrants quite closely (Anderson and Franck Citation2019). While ‘seepage’ does occur within managed migration programmes more broadly, as those migrants who are supposed to be temporarily present can end up staying for longer periods (Surak Citation2015, 169), this does not mean that managed migration programmes are not highly regulated spaces. Therefore, when it comes to examining how migration is governed and controlled in the context of managed migration programmes it is important to see ‘control’ in terms of not just the number of migrants, but also the conditions of their stay and how employers, brokers and other private actors form part of the structures that manage and control them.

Research context and methodology

Migration has long been important within Malaysia. Since the 1970s, as the government turned to industrialisation as a means to develop the economy, migration has been used to fill persistent labour shortages with the country (Kaur Citation2010; Nah Citation2011). Malaysia has also been a popular destination for migrants in the region given its strong economic growth and its wealth relative to its neighbours the Philippines, Indonesia, Pakistan and Bangladesh (Garcés-Mascareñas Citation2012). While migrants to Malaysia are admitted under several categories, the largest (and the focus of this research) are those termed ‘foreign workers’. The regulation of these workers was enshrined in the 1991 ‘Comprehensive Policy on the Recruitment of Foreign Workers’, which established such principles as allowing workers to work only for one employer and charging a levy for hiring workers (Kaur Citation2014).

The rules for foreign workers in Malaysia are narrowly defined and are designed to give workers relatively little room for manoeuvre while also trying to ensure that their stay is temporary (Nah Citation2012; Franck Citation2016). The Malaysian government specifies which industries an individual may work in depending on their nationality and gender (Immigration Department of Malaysia Citation2018). Not only must they pass a health inspection before their arrival, workers are not allowed to bring family members, become pregnant or become otherwise ‘medically unfit’ while in Malaysia (Garcés-Mascareñas Citation2012, 82). Workers are also tied to their employer while in Malaysia, and it is up to their employer to file for renewal of the work permit if desired, and to ensure that the worker leaves at the end of their contract (Nah Citation2012).

While Malaysia is known for signing memoranda of understandings (MoUs) with migrant-sending countries (Kaur Citation2014), the processes of recruiting, processing and transporting migrants to Malaysia on behalf of employers are largely outsourced. There are reported to be about 280 official ‘outsourcing companies’ that continue to function as the employer of the migrants even once they have come to Malaysia, and over 1000 ‘private employment agencies’ that act as labour brokers and recruiters on behalf of employers (Muñoz Moreno et al. Citation2015, 56). Given both the power endowed to employers over their workers and the extensive involvement of convoluted chains of private actors, many migrants end up in abusive employment relationships, including instances of forced labour. In a 2014 survey of foreign workers in the electronics industry, 32% of workers reported being in a situation of forced labour (Verité Citation2014). Because of how restrictive formal employment is in Malaysia for foreign workers, workers frequently choose to run away from employers even if it means losing legal status. For example, an in-depth study of foreign workers revealed that all but one of a group of 31 migrants interviewed had run away from their employer at some point, and 19 had gone between documented and undocumented legal status at least once, with one making the switch six times (Franck, Arellano, and Anderson Citation2018).

The migration policy shifts that will be discussed later in the paper have taken place in the context of a state which politically has been quite stable. Until 2018, Malaysia had the longest uninterrupted rule of a single party in a country with regular elections (Wong and Ooi Citation2018). As such, its political structure has been described using terms like ‘semi-democracy, competitive authoritarianism, soft authoritarianism, or pseudo-democracy’ (Arakaki Citation2013, 689). It has tended to feature power that is both relatively centralised and heavy-handed, while also being responsive to some degree to popular interests and sentiment (Crouch Citation1996). While a deep analysis of its political structures is beyond the scope of this paper, relevant to this endeavour is that it is clearly not a liberal democratic state like those examined by Joppke (Citation1998) or Hollifield (Citation2006), nor could electoral swings in power explain the policy changes examined below.

Yet, the Malaysian context is also notable for issues of corruption. A recent labour MoU with Nepal required renegotiation because Nepal had stopped all of its workers from going to Malaysia after it was revealed that workers had paid over 450 million USD in excessive fees. Furthermore, a company connected to family members of the Deputy Prime Minister, who also served as head of the Immigration Department, had been involved in the scheme and the companies through which migrants had been funnelled (Dixit Citation2019; Carvalho Citation2018). Similar allegations have been made related to Malaysia’s labour agreement with Bangladesh, with high levels of bribery and the channelling of lucrative contracts to well-connected individuals (The Star Citation2018a; Zsombor Citation2019). Within Malaysia, police officers frequently perform document checks, but these can be evaded through the paying of bribes (Franck Citation2016).

A complicating aspect of examining migration policy in Malaysia is that each of the ‘political entities’ of Peninsular Malaysia, Sabah and Sarawak has autonomous migration policies (Kaur Citation2014). While Sabah in particular has been the home to a number of complicated dynamics around migration control (see for example Joibi Citation2019), this paper focuses primarily on the developments in Peninsular Malaysia.

This paper draws its data from a review of articles published in Malaysian English-language online newspapers between 1 August 2011 and September 2019. The main papers reviewed were the New Straits Times, The Star and The Sun Daily, as they are amongst the largest newspapers in Malaysia. To identify important policies, the search first used broad terms such as ‘foreign workers’. Then the focus turned to searching for the specific policy programmes identified. This was supplemented by a review of the relevant scholarly literature as well as looking at the news bulletins provided by relevant organisations in Malaysia, such as the Malaysian Employers Federation (MEF) and the Immigration Department of Malaysia.

Online newspapers were selected because the Malaysian government makes relatively few documents, press releases or figures publicly available. However, policies and plans are revealed at press conferences or in interviews with the press. The press in Malaysia has relatively little independence and the owners of the main newspapers have close ties to the government (Nain Citation2017). While this means that views critical of state policy are muted (although not absent),Footnote 1 reviews of newspapers are helpful for understanding government policy. For this reason, newspaper articles are used regularly as sources of information on Malaysia both in the scholarly literature and in reports by international organisations like the ILO and World Bank.

However, even as online newspapers remain a commonly used source of information, they have their limitations. While this is perhaps reflective of the overall lack of clarity within how Malaysia governs migration, different stories sometimes give slightly different dates for when certain policy programmes began. It is difficult to know if this is due to unclear or inconsistent information provided by the government or through errors in the reporting itself. Where such discrepancies exist they are noted in the text.

Policy changes regarding foreign workers in Malaysia

Looking at the period from 2011 to 2019, it is clear that the Malaysian government has pursued a number of different strategies when it comes to controlling the population of undocumented foreign workers present within the country.Footnote 2 While there are a wide variety of policies that affect the situations of migrants, including policies around health and housing (Czaika and De Haas Citation2013), this paper mainly focuses on those policies that specifically targeted foreign workers, their legal status and the terms of their employment.

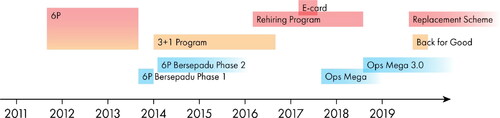

The timeline in highlights the most notable policies undertaken by the government during the period 2011–2019. These programmes generally fall into three categories. The first category of programmes (in red) are regularisation programmes. These programmes provide migrants, together with their sponsoring employers, opportunities to register in order to regularise their immigration status. The second category (in yellow) are those programmes which the government and media often refer to as amnesty programmes, but which are in fact voluntary deportation programmes. As undocumented foreign workers can face extensive fines and periods of detention if they are caught without documents during raids, these programmes provide them with the opportunity to return home under more favourable circumstances. Finally, the third category (in blue) are enforcement programmes, which are generally periods of increased or more targeted raids. As can be seen from the figure, these are often timed to begin once a regularisation or amnesty programme has ended. Beyond the introduction of these major programmes, some additional policy shifts that the government made will be discussed below.

Figure 1. Timeline of major migration policies in Malaysia (2011–2019).

Note: Boxes with gradient endings indicate unknown end dates.

The first programme examined here was designed to be comprehensive, combining a number of different processes into a single programme. It is known as 6P for ‘registration (Pendaftaran), legalization (Pemutihan), amnesty (Pengampunan), monitoring (Pemantauan), enforcement (Penguatkuasaan), and deportation (Pengusiran)’ (World Bank Citation2013, 124). The early phase of the programme involved a large-scale effort to register the biometric information of all foreign workers, allowing some to regularise their status while others were deported for failure to pass health checks or for not having a clean police record, or for other reasons (World Bank Citation2013). Since this was a blended programme, it is reflected as both red and yellow in . Originally scheduled to run until October 2011, the regularisation possibilities under the scheme continued until 10 April 2012 (Omar, Mokhtar, and Chin Citation2016). While it is exceedingly difficult to obtain reliable, comprehensive figures, those available suggest that at least 2 million, and up to 3 million, individuals were registered under the programme, with about half to two-thirds of those having irregular status at the time of registration (World Bank Citation2013, 124). Those regularised under the programme were allowed to extend their work permits for 2–3 years, although in December 2014 the government announced an extension of one additional year for about 300,000 workers who had been regularised under the 6P programme (Anwar Citation2014). While registration formally ended in April of 2012, a newspaper report from the beginning of January 2014 mentioned that employers were encouraged to register their foreign workers up until 20 January 2014, before enforcement action began the next day, as part of a three-month amnesty (The Star Online Citation2014).

As part of the 6P programme, the government also announced an enforcement initiative known as 6P Bersepadu. Conducted in two phases, it was reported that during the period 2011–2014, following the period of voluntary registration under the 6P programme, 28,450 undocumented foreign workers were arrested along with 486 employers (The Sun Daily Citation2014).

In February of 2016, the Malaysian government launched the ‘rehiring programme’ which was originally supposed to run only until June 2016; however, it was first extended to December 2017 (The Sun Daily Citation2017) and then later to 30 June 2018 (New Straits Times Citation2018). While in some ways similar to the earlier 6P programme in that it allowed workers to be regularised, it was also significantly more expensive for employers, and required the usage of one of three designated brokerage companies (The Sun Daily Citation2017). The rehiring programme was also generally less successful in regularising the status of workers. As of about one month before the end of the programme, 744,942 undocumented foreign workers had applied to have their status regularised, but of those 307,557 were qualified to be rehired, 108,234 were rejected for various reasons, and the remaining individuals had either not been able to supply the required documentation or had otherwise not completed their application or submitted biometric data (New Straits Times Citation2018).

The rehiring of existing workers was especially important for employers as in March of 2016,Footnote 3 the government instituted a freeze on bringing in foreign workers, including halting a planned admission of up to 1.5 million Bangladeshi workers (The Sun Daily Citation2016). As Malaysian employers are highly dependent on continuing to bring in workers, the freeze resulted in significant financial losses. The Deputy Prime Minister, whose government was responsible for instituting the freeze, estimated that businesses had lost ‘some RM24billion’ (Carvalho Citation2016) as a result of the migration freeze, a sum equal to about 5.7 billion USD. However, it is somewhat unclear exactly when the freeze was lifted or even if it was a complete freeze as there were some reports of some workers being allowed in (Free Malaysia Today Citation2016). The government first said it would lift the freeze in May and then said it would lift it at the end of the rehiring programme (30 June 2016), but then decided on 1 June that it ‘would not lift the ban until it is convinced that employers stopped using agents and took full responsibility of their workers welfare’ (Free Malaysia Today Citation2016).

In 2017, the government also instituted the ‘E-Card Program’, which allows for the temporary registration of workers while they waited for documents such as passports and for the completion of their regularisation applications. The programme ran from 15 February 2017 to 30 June 2017, with permits being valid until 15 February 2018. However, the head of the Immigration Department indicated that while they had hoped to register between 400,000 and 600,000 E-Cards, in the end they had only reached about 23% of that target on the eve of the end of the programme (The Star Citation2017). Despite issues with the E-Card process and being encouraged by employers’ groups to better align the deadline of the E-Card programme with that of the rehiring programme (The Star Online Citation2017), the government maintained the original deadline.

In addition to these efforts to regularise the status of foreign workers, the government initiated a number of programmes designed to get foreign workers to leave the country. These took the form of both voluntary deportation ‘amnesty’ programmes and raids in which foreign workers could be detained, fined and then deported. Since 2011, Malaysia has operated two primary ‘amnesty programmes’, the ‘3 + 1 Program’ and the ‘Back for Good’ (also sometimes styled ‘B4G’) Program.

In order to encourage workers to leave, the ‘3 + 1 Program’ ran from 2014 until 30 August 2018, and was so called because it allowed workers to leave upon payment of a fee of RM 300 plus RM 100 for a special pass allowing them to leave. Originally scheduled to run until 31 December 2015 (The Sun Daily Citation2015), the programme was later extended. A few weeks before the end of the programme in August 2018, the government indicated that over 840,000 individuals had been deported, with the government collecting RM 400 million in fees (Kumar Citation2018).Footnote 4 More recently, the ‘Back for Good’ programme, which started 1 August 2019 and is scheduled to run until 31 December 2019, allows workers to return to their home countries for a fee of RM 700, although – like before – they retain responsibility for the costs of their return travel as well as any travel documents (such as a passport) that they might need (Kumar Citation2019). However, there have been concerns that the fees combined with the other costs are not feasible for migrants and that not many migrants have been using the programme (Rahim Citation2019). The ‘Back for Good’ programme is also only available to those residing in Peninsular Malaysia.

The last primary category of programmes engaged in by the government is enforcement raids. These are often timed to coincide with the end of regularisation programmes or voluntary return programmes. Thus, for example, raids as part of Ops 6P Bersepedu were tied in with the regularisation programmes that also formed part of the 6P programme. Ops Mega began at the end of the E-Card programme, and Ops Mega 3.0 began at the end of the rehiring programme. Additionally, during the period 2011–2019, news sources also mentioned that workers were detained under enforcement raids named Ops Belanja, Ops Gegar, Ops Sapu and Ops Selera, yet provided no information about the distinguishing features of these ops or when they began or ended. Many raids involve the Malaysian Volunteer Corps (RELA), a volunteer security force which has migration enforcement as one of its missions (RELA Citation2020) and which has been known to receive a bounty for each migrant detained (Garcés-Mascareñas Citation2015). Such raids have also been known to detain individuals even if they have valid migration documents (Garcés-Mascareñas Citation2012, 100).

Additionally, and not reflected in the timeline above, a number of policy changes that the government made at various points are not reflected in these longer ‘programmes’. These are shifts that the government made to the general terms under which migrants are employed and supervised. While there were undoubtedly additional changes that were not large enough to make it into the press, the ones discussed here are some of those that appeared to be most significant.

One of these significant changes was to how foreign worker levies work in Malaysia. As a disincentive for hiring foreign workers, and as a source of revenue for the government, Malaysia has long charged a levy based on the field in which the worker is employed. In 2018, as part of an initiative that the government called the Employer Mandatory Commitment, the amount of the levies was increased significantly, to RM 1850 (about 450 USD) in the construction and services sector and RM 640 (150 USD) in agriculture (Lokman Citation2017). Although these were significant increases, they were not as large as the government had originally proposed, when they sought levies as high as RM 2500 (Anis Citation2016). Another significant change introduced as part of the Employer Mandatory Commitment was making employers rather than foreign workers responsible for paying the levies. While such a move could make migrants less indebted, in practice it often meant that the costs were simply pulled out of workers’ wages instead. This change in who is responsible for paying levies follows earlier changes, as employers were made responsible for levies in 2009 following criticism from non-governmental organisations, then the system reverted to having migrants pay levies in 2013 under pressure from employers (Kaur Citation2015, 219).

In an attempt to shift even more responsibility (and control) to employers, the government also proposed, in 2015, the Strict Liability Principle in which employers would also be responsible for the housing of foreign workers (Tam Citation2015). Another proposed shift has been to reduce the influence of labour brokers in the migration process. Rather than having employers rely on private labour brokers, as is common in temporary labour programmes both in Asia and around the world (Lindquist Citation2017; Kaur Citation2012), this proposal would make the Ministry of Human Resources responsible for all foreign worker recruitment. However, while this was discussed in the media in late 2018 (Musa Citation2018) attempts to implement these programs have faltered (Low Citation2020).

Emerging patterns of migration control

Given the large number of policy changes and reversals, and the frequent introduction of new programmes, it can be difficult to identify any consistency amongst the policy tools that Malaysia has used. While, it seems that Malaysian immigration policy remains ‘engimatic’ (Nah Citation2011, 4) and ‘ad-hoc’ (Loh et al. Citation2019), nevertheless some patterns have emerged.

The first pattern that emerges is that these policies are internally focussed. Compared to migration control in the Global North which is often focussed on external border controls, such as the securing of the US–Mexico border or the creation of ‘Fortress Europe’ (see for example Andreas and Snyder Citation2000), the policies examined here all rely on mechanisms of internal control. As mentioned, switching between legal and illegal status while in Malaysia is extremely common, and migrants may end up making the switch multiple times (Franck, Arellano, and Anderson Citation2018). The conditions for maintaining legal status are extremely rigid and narrow (Nah Citation2012). It is not possible to switch employers, even in the case of abusive employers, and maintaining one’s status requires the payment of hefty fees (Nah Citation2012). The significant costs associated with legal status mean that it can be a valuable ‘commodity’ to pursue at certain times, but workers may also often feel that it is not worth the cost (Franck and Anderson Citation2019). What this has meant in practice is that many (if not most) undocumented migrants in Malaysia originally had a legal status, and that therefore the presence of undocumented foreign workers is closely tied to the continued recruitment and presence of legal foreign workers.

The second pattern that emerges is that even though there have been rapid and frequent shifts in policies, the underlying mechanisms are largely the same. While there have been different voluntary deportation (‘amnesty’) programmes, regularisation programmes and raids, there has not been significant variation between the programmes within each category. The timing, level of fines and procedures have varied somewhat between programmes, but they are notable overall for their relative similarity. Take, for example, the various voluntary deportation programmes. Despite the name change and the slight increase in the fine, the ‘3 + 1 Program’ and the ‘Back for Good’ programmes were largely identical. Even though there had been a promise of ‘no second chances’ after the end of ‘3 + 1 Program’, the ‘Back for Good’ programme was launched because, in the words of Home Minister Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin, ‘While the previous programmes were effective, the number of illegal immigrants in the country is still large’. He also promised, however, that this time there would be no extensions to the programme (Kumar Citation2019). From this it remains unclear whether the government found the earlier iteration of the programme successful but incomplete, or whether, as has been said of Europe’s migration policy and recalling Einstein’s definition of madness, it is ‘doing the same thing over and over, each time hoping for a different result’ (Andersson Citation2015).

The third pattern that emerges is that while Malaysia has a wide variety of tools at its disposal, most changes have come through ‘voluntary’ measures rather than aggressive raids. Even as newspapers frequently print stories about raids, the number of individuals caught in these raids is often relatively small, with reported numbers of usually 30 or 40, although sometimes up to a few hundred (see for example The Star Citation2015; Zolkepli Citation2018; Shahrudin Citation2017). After regularising the status of over 500,000 workers as part of the 6P programme (Loh et al. Citation2019), raids in the three years following the programme managed to ensnare only around 28,000 workers (The Sun Daily Citation2014). The rehiring programme saw the registration of roughly 300,000 individuals (New Straits Times Citation2018), and the ‘3 + 1’ voluntary deportation programme, which ended two months later, was reported to have led to the departure of 840,000 individuals (Kumar Citation2018). Comparatively, a month after the end of ‘3 + 1’ it was reported that a total of 30,000 individuals had been detained in raids in the previous nine months (Bernama Citation2018a).

However, the term ‘voluntary’ should be used cautiously here. While raids seem to account for many fewer changes in status than other mechanisms do, Malaysia is known for being extremely harsh against individuals. Caning and whipping remain possible punishments for migrants who are found without papers as well as for employers who hire foreign workers without proper documentation, and Malaysia has been criticised for the often horrible treatment and conditions of detained migrants (Nah Citation2012). Immigration Director Datuk Seri Mustafar Ali was quoted as saying ‘Some people say that caning could be seen as cruel, but if we look at it from the security and sovereignty aspect, it is a matter which cannot be compromised’ (The Star Citation2018b). While the government does not hesitate to make public their desire to whip or cane individuals who break migration rules, an article noted that amongst those employers charged in courts, only three of 1400 were caned (The Star Citation2018b). Overall, while the strategy in Malaysia has seemed to rely more on ‘voluntary’ actions, there has also been a strong interest in demonstrating the possible punishments that await those who are not in compliance.

Undocumented foreign workers and Malaysian migration policy

As highlighted above, the country has taken a number of steps to control the population of undocumented workers through various strategies, although with some common aspects. However, these policy initiatives should be placed within the context of the central relationship between the economy and the use of foreign workers within Malaysia, as the Malaysian government’s promotion and use of foreign workers has been closely tied to economic needs. The initial move to use foreign workers in Malaysia was linked to a severe labour shortage, and Malaysia created its foreign worker system as part of a larger project of economic development and growth (Kaur Citation2014). Although migrant numbers are notoriously difficult to pinpoint in Malaysia, at the upper range of estimates as much as 40% of the labour force may be made up of foreign workers, documented and undocumented (Lek Citation2016). Malaysia continues to bring in significant numbers of foreign workers, and in recent years has also been developing a more centralised ‘Government to Government’ model for labour recruitment (Low Citation2020). Malaysia has signed agreements with Cambodia and Indonesia (Harkins Citation2016) and recently signed a new MoU with Nepal (Dixit Citation2019). Under the terms of a deal with Bangladesh, renegotiated in 2016, Malaysia sought to bring in up to 1.5 million Bangladeshi workers (Low Citation2020). The agreement was cancelled in 2018 following concerns about exploitation and corruption, but the Malaysian government has been working to renew its agreement with Bangladesh as well as beginning negotiations with the Philippines before the expiration of their agreement (Zsombor Citation2019; Bernama Citation2018b). The presence of foreign workers in Malaysia is not the byproduct of state liberalism, but part of an explicit government strategy.

Moreover, as Nah has argued, the entire system of foreign workers is predicated on their economic value (Citation2012). What is created is a ‘hierarchy of rights’ which provides protection to those who are seen as providing the most value while offering almost no rights to the ‘foreign workers’ at the bottom (Nah Citation2012) Thus, the use of foreign workers in Malaysia, like state use of guestworkers more broadly, is seen as a tool to provide ‘government protection of both the economy and the nation’ (Surak Citation2013b, 88), balancing migrants’ economic utility while ensuring that they are not seen as an undue burden on society. As discussed above, the government on several occasions backtracked from proposals to further restrict migration or raise costs, after protests from important industry groups including the influential MEF (Anis Citation2016; Mahalingam and Inn Citation2017). Also, as discussed above, the voluntary nature of many of the programmes could be seen as a means of softening the impacts on the business community, who would likely find aggressive raids significantly more disruptive. At the same time, generating publicity around the raids that do occur and frequent promises about eliminating migrant workers speak to the government’s desire to simultaneously take a tough public stance.

While such balancing of competing interests is often associated with liberal states (Freeman Citation1995), even more autocratic states have displayed a need to be sensitive to different interest groups in society (Natter Citation2018; Shin Citation2017). However, the government has occasionally shown a willingness to be more aggressive in its efforts to decrease the total number of migrants and provide a sense of control, even if it ends up damaging the economy, such as the 2016 hiring freeze discussed above. Yet the tremendous economic damage from that freeze, estimated at up to 5.7 billion USD (Carvalho Citation2016), underscores the overall reliance of the Malaysian economy on the labour of foreign workers.

Recalling that ‘migration policies are established in order to affect behavior of a target population (i.e. potential migrants) in an intended direction’ (Czaika and De Haas Citation2013, 489), the question remains exactly what the ‘intended direction’ is that the Malaysian government seeks for undocumented migrants. While, as discussed above, certain patterns emerge, overall the policies have variously allowed migrants to regularise their status and stay in Malaysia, while at other points it has sought to get them to leave, either voluntarily or after being detained. The Malaysian government has therefore cycled relatively quickly through divergent policy choices, sometimes pursuing all of them at the same time (as in the 6P programme programme). While the ability of less-democratic regimes to make sudden policy shifts is well documented (see for example Natter Citation2018; Norman Citation2016), what is striking about the Malaysian case is not just having an abrupt change, but having almost constant abrupt changes. Here, looking simply at the case of undocumented foreign workers, there have been eleven major policies in a space of just eight years.

This is especially notable as many of these changes are not new comprehensive policies, but rather temporary initiatives. The regularisation and voluntary deportation programmes are designed with clear beginning and end dates (although these may end up changing), but they are not permanent. Rather than the creation of durable policy frameworks, undocumented workers during the period studied here were instead largely governed through exceptions to existing rules. In this context it becomes difficult to evaluate policy success or failure in a comprehensive manner, since the policies themselves are so short-lived (Castles Citation2004b). If ‘migration policy is seen to revolve around the walls that states build and how wide they open the small doors in these walls’ (Geddes Citation2012, 96) it becomes difficult to consistently characterise the size of the door in Malaysia, since it may change significantly from one month to the next.

Conclusions

The tendency to focus on liberal and democratic states which seek to control migration (Hollifield Citation2006; Hollifield, Martin, and Orrenius Citation2014; Joppke Citation1998) has meant that migration control in other contexts remains comparatively understudied. Because such analyses have tended to proceed from an argument that links migration policy success to regime type and not to the specific characteristics of the policy, it is instructive here to engage more deeply with the particular policy changes in Malaysia.

Here, looking at the policies put in place by the Malaysian government has revealed that rather than pursue a consistent set of policies to control the number of undocumented workers, the government has rotated through a large number of policy approaches. While certain patterns of internal control, policy type and a reliance on voluntary action rather than purely coercive measures emerge, these do not comprise a consistent policy. Furthermore, issues of policy regarding the control of undocumented workers need to be placed in the context of a larger political and economic system that remains committed to using the labour of foreign workers.

Finally, this examination of the specific policy moves in Malaysia suggests there is a need for more research on the complexity of migration policymaking. The tendency to think of migration control in broad strokes and trends, present not only in the works referred to above but also in attempts to look historically (Haas et al. Citation2019) or to create typologies (Boucher and Gest Citation2018), means that the variation in policies is sometimes lost. Here, the analysis of Malaysian policies revealed not a state that was restrictionist or welcoming, but one that went back and forth between these policies – often within the space of a few months. More work is needed to help us better understand these nuances of migration policy.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Joseph Trawicki Anderson

Joseph Trawicki Anderson is an Associate Researcher in the School of Global Studies at the University of Gothenburg. His research focuses on the interactions between public and private actors and interests in controlling and governing migration.

Notes

1 Migrant rights organisations have been able to publish opinion pieces criticising migration policy and industry leaders, like those of the MEF or the Malaysian Trades Union Congress.

2 For information on years prior to 2011, see Devadason and Meng (Citation2014).

3 Another source listed the beginning of the freeze as being in mid-February (see Carvalho Citation2016).

4 While these are the figures reported by the government, in order for the figures to add up the government would have to have been collecting more than the RM 400 per migrant specified in the programme.

Bibliography

- Abella, Manolo . 2006. “Policies and Best Practices for Management of Temporary Migration.” UN/POP/MIG/SYMP/2006/03. Turin: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

- Adamson, Fiona B. , and Gerasimos Tsourapas . 2019. “The Migration State in the Global South: Nationalizing, Developmental, and Neoliberal Models of Migration Management.” International Migration Review . doi:https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/wze2p.

- Anderson, Joseph Trawicki , and Anja K. Franck . 2019. “The Public and the Private in Guestworker Schemes: Examples from Malaysia and the U.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (7): 1207–1223. S.” . doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1415752.

- Andersson, Ruben . 2015. “Europe’s Migrant ‘Emergency’ is Entirely of Its Own Making | Ruben Andersson.” The Guardian, August 22. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/aug/23/politics-migrants-europe-asylum.

- Andreas, Peter , and Timothy Snyder . 2000. The Wall around the West: State Borders and Immigration Controls in North America and Europe . Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Anis, Maswin Nik . 2016. “New Foreign Worker Levies for Peninsular Malaysia Effective Today.” The Star Online. March 18. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2016/03/18/foreign-worker-levies-penisular-malaysia.

- Anwar, Zafira . 2014. “Work Permit Extended for 300,000.” NST Online. December 19. https://www.nst.com.my/news/2015/09/work-permit-extended-300000.

- Arakaki, Robert . 2013. “Malaysia’s 2013 General Election and Its Democratic Prospects.” Asian Politics & Policy 5 (4): 689–692. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/aspp.12058.

- Arcarazo, Diego Acosta , and Luisa Feline Freier . 2015. “Turning the Immigration Policy Paradox Upside down? Populist Liberalism and Discursive Gaps in South America.” International Migration Review 49 (3): 659–696. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/imre.12146.

- Bal, Charanpal S. , and Kelly Gerard . 2018. “ASEAN’s Governance of Migrant Worker Rights.” Third World Quarterly 39 (4): 799–819. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2017.1387478.

- Bernama . 2018a. “Over 30,000 Illegal Immigrants Nabbed since Jan 1: Immigration Dept.” NST Online. September 4. https://www.nst.com.my/news/nation/2018/09/408071/over-30000-illegal-immigrants-nabbed-jan-1-immigration-dept.

- Bernama . 2018b. “ Gov’t Working on Improved, Standardised MOU on Hiring Foreign Workers.” NST Online . November 28. https://www.nst.com.my/news/nation/2018/11/435432/govt-working-improved-standardised-mou-hiring-foreign-workers.

- Bonjour, Saskia . 2011. “The Power and Morals of Policy Makers: Reassessing the Control Gap Debate.” International Migration Review 45 (1): 89–122. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23016190.

- Boswell, Christina . 2007. “Theorizing Migration Policy: Is There a Third Way?” International Migration Review 41 (1): 75–100. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2007.00057.x.

- Boucher, Anna , and Justin Gest . 2018. Crossroads: Comparative Immigration Regimes in a World of Demographic Change . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Calavita, Kitty . 1992. Inside the State: The Bracero Program, Immigration, and the I.N.S. New York: Routledge.

- Carvalho, Martin . 2016. “Zahid: RM24bil Lost Because of Foreign Worker Freeze.” The Star Online, June 17. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2016/06/17/zahid-foreign-workers-24bil-losses.

- Carvalho, Martin . 2018. “Nepali Worker Issue: Ahmad Zahid Says Ready to Be Investigated by MACC.” The Star Online. July 23. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2018/07/23/nepal-issues-ahmad-zahid-ready-to-be-investigated-by-macc.

- Castles, Stephen . 2004a. “The Factors That Make and Unmake Migration Policies.” International Migration Review 38 (3): 852–884. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2004.tb00222.x.

- Castles, Stephen . 2004b. “Why Migration Policies Fail.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 27 (2): 205–227. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0141987042000177306.

- Chalamwong, Yongyuth , Jidapa Meepien , and Khanittha Hongprayoon . 2012. “Management of Cross-Border Migration: Thailand as a Case of Net Immigration.” Asian Journal of Social Science 40 (4): 447–463. doi:https://doi.org/10.1163/15685314-12341251.

- Cornelius, Wayne A . 2004. Controlling Immigration: A Global Perspective . Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Crouch, Harold . 1996. Government and Society in Malaysia . Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Czaika, Mathias , and Hein De Haas . 2013. “The Effectiveness of Immigration Policies.” Population and Development Review 39 (3): 487–508. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2013.00613.x.

- Devadason, Evelyn Shyamala , and Chan Wai Meng . 2014. “Policies and Laws Regulating Migrant Workers in Malaysia: A Critical Appraisal.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 44 (1): 19–35. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2013.826420.

- Dixit, Kunda . 2019. “Nepal and Malaysia Rewrite Rules for Migrant Labour.” The Nepal Times (blog), September 15. https://www.nepalitimes.com/here-now/nepal-and-malaysia-rewrite-rules-for-migrant-labour/.

- Franck, Anja K . 2016. “A(Nother) Geography of Fear: Burmese Labour Migrants in George Town.” Urban Studies 53 (15): 3206–3222. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098015613003.

- Franck, Anja K. , and Joseph Trawicki Anderson . 2019. “The Cost of Legality: Navigating Labour Mobility and Exploitation in Malaysia.” International Quarterly for Asian Studies 50 (1–2): 19–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.11588/iqas.2019.1-2.10288.

- Franck, Anja K. , Emanuelle Brandström Arellano , and Joseph Trawicki Anderson . 2018. “Navigating Migrant Trajectories through Private Actors: Burmese Labour Migration to Malaysia.” European Journal of East Asian Studies 17 (1): 55–82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1163/15700615-01701003.

- Free Malaysia Today . 2016. “Foreign Workers Still Coming in despite Hiring Freeze.” Free Malaysia Today (blog). August 8. https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/nation/2016/08/08/foreign-workers-still-coming-in-despite-hiring-freeze/.

- Freeman, Gary P . 1995. “Modes of Immigration Politics in Liberal Democratic States.” The International Migration Review 29 (4): 881–902. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2547729.

- Freeman, Gary p . 2006. “National Models, Policy Types, and the Politics of Immigration in Liberal Democracies.” West European Politics 29 (2): 227–247. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380500512585.

- Garcés-Mascareñas, Blanca . 2012. Labour Migration in Malaysia and Spain: Markets, Citizenship and Rights . Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Garcés-Mascareñas, Blanca . 2015. “Revisiting Bordering Practices: Irregular Migration, Borders, and Citizenship in Malaysia.” International Political Sociology 9 (2): 128–142. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/ips.12087.

- Geddes, Andrew . 2012. “The European Union’s Extraterritorial Immigration Controls and International Migration Relations.” In Migration, Nation States, and International Cooperation , edited by Randall Hansen , Jobst Koehler , and Jeannette Money , 87–100. London: Routledge.

- Guiraudon, Virginie , 2012. “De-Nationalizing Control: Analyzing State Responses to Constraints on Migration Control.” In Controlling a New Migration World , edited by Virginie Guiraudon and Christian Joppke , 29–64. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. http://public.eblib.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=180579.

- Haas, Hein , Mathias Czaika , Marie-Laurence Flahaux , Edo Mahendra , Katharina Natter , Simona Vezzoli , and María Villares-Varela . 2019. “International Migration: Trends, Determinants, and Policy Effects.” Population and Development Review 45 (4): 885–922. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/padr.12291.

- Harkins, Benjamin . 2016. Review of Labour Migration Policy in Malaysia. Bangkok: ILO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific.

- Hollifield, James , Philip L. Martin , and Pia M. Orrenius , eds. 2014. Controlling Immigration: A Global Perspective . 3rd edition. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Hollifield, James . 2006. “The Emerging Migration State.” International Migration Review 38 (3): 885–912. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2004.tb00223.x.

- Immigration Department of Malaysia . 2018. “Foreign Workers.” https://www.imi.gov.my/index.php/en/main-services/foreign-workers.html.

- Joibi, Natasha . 2019. “Sabah CM Defends Proposal to Legitimise Illegal Workers.” The Star Online, January 12. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2019/01/12/sabah-cm-dont-be-swayed-by-sentiments-when-running-the-country.

- Joppke, Christian . 1998. “Why Liberal States Accept Unwanted Immigration.” World Politics 50 (2): 266–293. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S004388710000811X.

- Kaur, Amarjit . 2010. “Labour Migration in Southeast Asia: Migration Policies, Labour Exploitation and Regulation.” Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy 15 (1): 6–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13547860903488195.

- Kaur, Amarjit . 2012. “Labour Brokers in Migration: Understanding Historical and Contemporary Transnational Migration Regimes in Malaya/Malaysia.” International Review of Social History 57 (S20): 225–252. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020859012000478.

- Kaur, Amarjit . 2014. “Managing Labour Migration in Malaysia: Guest Worker Programs and the Regularisation of Irregular Labour Migrants as a Policy Instrument.” Asian Studies Review 38 (3): 345–366. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10357823.2014.934659.

- Kaur, Amarjit . 2015. “Labour in Malaysia: Flexibility, Policy-Making and Regulated Borders.” In Routledge Handbook of Contemporary Malaysia , edited by Meredith L Weiss , 214–225. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Kumar, M . 2018. “840,000 Nabbed, RM400mil Collected as Immigration’s Amnesty Draws to a Close.” The Star Online, August 4. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2018/08/04/840000-nabbed-rm400mil-collected-as-immigrations-amnesty-draws-to-a-close.

- Kumar, M . 2019. “Fresh Bid to Send Illegal Workers ‘Back for Good.” The Star Online, July 19. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2019/07/19/fresh-bid-to-send-illegal-workers-back-for-good.

- Lek, Pooh A. H . 2016. “The Dilemma of Having Foreign Workers in Malaysia.” Text. The Straits Times. September 17. https://www.straitstimes.com/opinion/the-dilemma-of-having-foreign-workers-in-malaysia.

- Lindquist, Johan . 2012. “The Elementary School Teacher, the Thug and His Grandmother: Informal Brokers and Transnational Migration from Indonesia.” Pacific Affairs 85 (1): 69–89. doi:https://doi.org/10.5509/201285169.

- Lindquist, Johan . 2017. “Brokers, Channels, Infrastructure: Moving Migrant Labor in the Indonesian-Malaysian Oil Palm Complex.” Mobilities 12 (2): 213–226. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2017.1292778.

- Loh, Wei San , Kenneth Simler , Kershia Tan Wei , and Soonhwa Yi . 2019. “Malaysia - Estimating the Number of Foreign Workers : A Report from the Labor Market Data for Monetary Policy Task.” Report Number AUS0000681. The World Bank. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/953091562223517841/Malaysia-Estimating-the-Number-of-Foreign-Workers-A-Report-from-the-Labor-Market-Data-for-Monetary-Policy-Task.

- Lokman, Tasnim , 2017. “Employers to Pay Levy for Foreign Workers from Jan 1, 2018.” Nst Online, December 20. https://www.nst.com.my/news/nation/2017/12/316614/employers-pay-levy-foreign-workers-jan-1-2018.

- Low, Choo Chin . 2017. “A Strategy of Attrition through Enforcement: The Unmaking of Irregular Migration in Malaysia.” Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs 36 (2): 101–136. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/186810341703600204.

- Low, Choo Chin . 2020. “De-Commercialization of the Labor Migration Industry in Malaysia.” Southeast Asian Studies 9 (1): 27–65. doi:https://doi.org/10.20495/seas.9.1_27.

- Mahalingam, Eugene , and Toh Kar Inn . 2017. “New Foreign Worker Levy Rule Weighs on Manufacturers.” The Star Online, January 4. https://www.thestar.com.my/business/business-news/2017/01/04/new-levy-rule-weighs-on-manufacturers.

- McKeown, Adam . 2008. Melancholy Order: Asian Migration and the Globalization of Borders . New York: Columbia University Press.

- McKeown, Adam . 2012. “How the Box Became Black: Brokers and the Creation of the Free Migrant.” Pacific Affairs 85 (1): 21–45. doi:https://doi.org/10.5509/201285121.

- Moreno, Muñoz , Rafael del Carpio , Ximena Vanessa , Harry Edmund Moroz , Loo Carmen , Kamer Karakurum-Ozdemir , Pui Shen Yoong , Rebekah Lee Smith , and Mauro Testaverde . 2015. “Malaysia - Economic Monitor: Immigrant Labor.” Report number 102131. The World Bank. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/753511468197095162/Malaysia-Economic-monitor-immigrant-labor.

- Musa, Zazali . 2018. “Association All for Abolishing Foreign Worker Agent Service.” The Star Online, November 9. https://www.thestar.com.my/metro/metro-news/2018/11/09/association-all-forabolishing-foreign-worker-agent-service.

- Nah, Alice M . 2011. “State Power and the Regulation of Non-Citizens: Immigration Laws, Policies, and Practices in Peninsular Malaysia.” PhD diss., National University of Singapore.

- Nah, Alice M . 2012. “Globalisation, Sovereignty and Immigration Control: The Hierarchy of Rights for Migrant Workers in Malaysia.” Asian Journal of Social Science 40 (4): 486–508. doi:https://doi.org/10.1163/15685314-12341244.

- Nain, Zaharom . 2017. “Malaysia.” Digital News Report. http://www.digitalnewsreport.org/survey/2017/malaysia-2017/.

- Natter, Katharina . 2018 . “Rethinking Immigration Policy Theory beyond 'Western liberal democracies'.” Comparative Migration Studies 6 (1): 4. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-018-0071-9.

- New Straits Times . 2018. “No More Second Chances for Illegal Immigrants and Their Bosses Come July 1.” NST Online, June 1. https://www.nst.com.my/news/nation/2018/06/375479/no-more-second-chances-illegal-immigrants-and-their-bosses-come-july-1.

- Norman, Kelsey P . 2016. “Between Europe and Africa: Morocco as a Country of Immigration.” The Journal of the Middle East and Africa 7 (4): 421–439. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21520844.2016.1237258.

- Omar, Nor Sakinah , Khairiah Salwa Mokhtar , and Low Choo Chin . 2016. “Managing the Deportation of Undocumented Migrants in Malaysia: A Review.” Paper Presented at Social Sciences Postgraduate International Seminar, Penang, Malaysia.

- Paitoonpong, Srawooth , and Yongyuth Chalamwong . 2012. “Managing International Labor Migration in ASEAN: A Case of Thailand.” Thailand Development Research Institute. https://tdri.or.th/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/h117.pdf.

- Rahim, Rahimy Bin A . 2019. “Cut RM700 Fine under B4G Scheme.” The Star Online, September 26. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2019/09/26/cut-rm700-fine-under-b4g-scheme.

- RELA . 2020. “History.” Official Portal Volunteers Department of Malaysia. Accessed 12 February 2020. http://www.rela.gov.my/en/history/.

- Rodriguez, Robyn . 2010. Migrants for Export: How the Philippine State Brokers Labor to the World . Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Shahrudin, Hani Shamira . 2017. “80 Illegal Immigrants Nabbed in Morning Raid on Segambut Settlement.” NST Online, July 21. https://www.nst.com.my/news/nation/2017/07/259293/80-illegal-immigrants-nabbed-morning-raid-segambut-settlement.

- Shin, Adrian J . 2017. “Tyrants and Migrants: Authoritarian Immigration Policy.” Comparative Political Studies 50 (1): 14–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414015621076.

- Surak, Kristin . 2013. “The Migration Industry and Developmental States in East Asia.” In The Migration Industry and the Commercialization of International Migration , edited by Thomas Gammeltoft-Hansen and Ninna Nyberg Sørensen . New York: Routledge.

- Surak, Kristin . 2015. “Guestworker Regimes Globally: A Historical Comparison.” In Handbook of the International Political Economy of Migration , edited by Leila Simona Talani and Simon McMahon , 167–184. Handbooks of Research on International Political Economy. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Surak, Kristin . 2018. “Migration Industries and the State: Guestwork Programs in East Asia.” International Migration Review 52 (2): 487–523. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/imre.12308.

- Tam, Michelle . 2015. “11MP: Management of Foreign Workers to Be Improved.” The Star Online, May 21. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2015/05/21/11mp-foreign-workers.

- The Star Online . 2014. “10,000 to Take Part in Nationwide Ops Bersepadu.” The Star Online, January 10. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2014/01/10/10000-to-take-part-in-nationwide-ops-bersepadu.

- The Star Online . 2017. “Employers Regret Not Registering Workers Earlier.” The Star Online, July 1. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2017/07/01/employers-regret-not-registering-workers-earlier.

- The Star . 2015. “29 Foreign Workers Held in Raids at Construction Sites.” The Star Online, July 12. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2015/07/12/29-foreign-workers-held-in-raids-at-construction-sites.

- The Star . 2017. “Fuming Immigration Boss: Deadline for E-Card Registration Stays.” The Star Online, July 1. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2017/07/01/absolutely-no-extension-fuming-immigration-boss-deadline-for-ecard-registration-stays.

- The Star . 2018a. “Bangladeshi Worker Recruitment: ‘Monopoly’ Was Mostly KL’s Doing, Say Officials.” The Star Online, November 1. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2018/11/01/recruitment-in-malaysia-monopoly-was-mostly-kls-doing.

- The Star . 2018b. “Caning Acts as a Deterrent to Hiring Illegals, Says Immigration D-G.” The Star Online, December 29. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2018/12/29/caning-acts-as-a-deterrent-to-hiring-illegals-says-immigration-dg.

- The Sun Daily. 2014. “28,000 Illegals Arrested over Last 3 Years.” Www.Thesundaily.My, December 10. https://www.thesundaily.my/archive/1263794-KRARCH285155.

- The Sun Daily. 2015. “More than 222,000 Illegals Deported This Year.” Www.Thesundaily.My, November 29. https://www.thesundaily.my/archive/1623854-ASARCH339855.

- The Sun Daily. 2016. “Hire Illegals and Face the Full Brunt of the Law: Immigration DG.” Www.Thesundaily.My, September 13. https://www.thesundaily.my/archive/1969382-XSARCH394379.

- The Sun Daily. 2017. “Days of ‘cheap’ Foreign Labour over for Builders.” Www.Thesundaily.My, July 30. https://www.thesundaily.my/archive/days-cheap-foreign-labour-over-builders-FTARCH465985.

- Thiollet, Hélène . 2019. “Immigrants, Markets, Brokers, and States: The Politics of Illiberal Migration Governance in the Arab Gulf.” https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02362910.

- Verité . 2014. “Forced Labor in the Production of Electronic Goods in Malaysia: A Comprehensive Study of Scope and Characteristics.” https://www.verite.org/sites/default/files/images/VeriteForcedLaborMalaysianElectronics2014.pdf.

- Vigneswaran, Darshan , and Joel Quirk . 2015. Mobility Makes States: Migration and Power in Africa . Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Wong, Chin-Huat , and Kee Beng Ooi . 2018. “Introduction: How Did Malaysia End UMNO’s 61 Years of One-Party Rule? What’s Next?” The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Studies 107 (6): 661–667. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00358533.2018.1545944.

- World Bank . 2013. “Immigration in Malaysia: Assessment of Its Economic Effects, and a Review of the Policy and System.” https://www.knomad.org/event/immigration-malaysia-assessment-its-economic-effects-and-review-policy-and-system.

- Xiang, Biao . 2012. “Predatory Princes and Princely Peddlers: The State and International Labour Migration Intermediaries in China.” Pacific Affairs 85 (1): 47–68. doi:https://doi.org/10.5509/201285147.

- Yusof, Teh Athira , and Masriwanie Muhamading . 2018. “[Exclusive] ‘PH Will Rid Country of Illegals within a Month.’” New Straits Times, July 23. https://www.nst.com.my/news/exclusive/2018/07/393416/exclusive-ph-will-rid-country-illegals-within-month.

- Zolkepli, Farik . 2018. “338 Foreign Workers Detained after Factory Raid in Cyberjaya.” The Star Online, September 22. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2018/09/22/338-foreign-workers-detained-after-factory-raid-in-cyberjaya.

- Zsombor, Peter . 2019. “Malaysia Readies New Deal for Bangladesh’s Fleeced Migrant Workers.” Voice of America, November 18. https://www.voanews.com/east-asia-pacific/malaysia-readies-new-deal-bangladeshs-fleeced-migrant-workers.