Abstract

Since the Trump administration started its ‘war on migrants’ many of civil society’s responses have been oriented to counter the impact of this ‘war’. Such responses include the creation of sanctuary cities and providing legal defence to migrants. In Mexico, the actions of the Trump administration have also reverberated among migrant communities and within government circles. Ways of dealing with the challenges posed by the Trump administration range from policies directed at return migrants to providing shelter to Central American migrants in transit, to organising caravanas de migrantes to the Mexico–US border. This paper addresses how these caravanas have become the focus of biopolitical struggles among different authorities, migrant smugglers and civil society organisations. It argues that biopolitics is not just a state-initiated phenomenon, but that non-state actors are also practicing biopolitics.

Introduction

For more than 10 years now, there have been caravanas de migrantes (CM) from Central America to Mexico, although not all of them reached the Mexican–US border. These earlier CMs received some attention in Mexico from the media, government and civil society, but relatively little interest from their counterparts abroad. This changed in 2018, when the CM became one of the hottest debated topics in Mexican–US relations. Early accounts of the 2018 CM, five in total with one in the spring and four in the fall, show that they involve many different actors, with their distinct agendas generating several layers of complexity. While the debates around the CM have focussed in particular on the responses by the Trump administration and the crisis situations at Mexico’s northern and southern borders, there are many other issues that deserve attention. In this article I will address local and transnational organising around the different CMs and how local and federal governments have responded to the CMs and related organising. The article will focus in particular on how local and transnational organisations as well as government actors have engaged in a biopolitics, sometimes even taking a necropolitical approach, towards the CMs. Although biopolitics is usually associated with the governmentality of the state, this article sets out to show that some of the groups involved in organising the CMs went beyond resisting state-related biopolitics by engaging themselves in biopolitical practices, by way of disciplining and controlling the CMs. The article addresses the central themes of new architectures and actors in migration governance, raised in the introduction to this collection, by focussing on the biopolitical struggles around the CMs and the multiple actors involved (Riemsdijk, Marchand, and Heins Citation2020).

The article will first provide a short account of the different CMs between the spring of 2018 and the spring of 2019. Then it will introduce some key concepts related to Michel Foucault’s notion of biopolitics. The final section involves an analysis of the different ‘biopolitical interventions and practices’ around the CMs. It is important to note that the situation around the CMs is evolving rapidly and that the present paper provides an analysis of a phenomenon in a particular time frame, that of 2018 until the summer of 2019.

The article is based on a qualitative analysis of the phenomenon of CMs, which according to Varela Huerta and McLean (Citation2019) is a new model of transmigration. For the analysis I am using a range of qualitative methods, including social media accounts and newspaper reports of the CMs, which often include ethnographic information, such as interviews with government officials and civil society representatives directly involved with CMs, and secondary literature, in the form of analyses by academics and civil society representatives. Unfortunately, I was not able to engage with the CMs directly, as I was abroad when they passed through the city in which I live. In the fall of 2019 I was able to speak to some of the participants in the Caravanas de Madres Centroamericanas de Migrantes Desaparecidos. However, as this falls outside of the time frame used for the present analysis, I am not directly relying on the information I gathered during that encounter.

Caravanas de migrantes (2018–2019): evolution of a ‘model of transmigration’

CMs making their way from Central America’s Northern Triangle to Mexico have been around for more than 10 years. The most well known of these are the Caravanas de Madres Centroamericanas de Migrantes Desaparecidos (CMCMD)Footnote 1 which have taken place 15 times (Nodal Dec. 4, 2019; Web Radio Migrantes-Español Citation2018, Oct. 16). Other, less well-known ‘Caravanas’ are the ones organised by the Asociación de Migrantes Retornados con Discapacidad Footnote 2 which took place in 2014 and 2016 (Martínez Hernández-Mejía Citation2018, 234). Most of these CMs did not have the purpose of getting to Mexico’s northern border. For instance, the CMCMDs were organised to pressure the Mexican government to seriously investigate the disappearances of their family members.

Starting in 2011, several CMs were organised during Easter time, using the symbolism of the Stations of the Cross, the Catholic tradition of Christ’s crucifixion during Easter (Vargas Carrasco Citation2018). As Ileana Martínez H. M. explains, the first CM Vía Crucis coincided with another Caravana, that of AMIREDIS. While it was not the objective of the CMs Via Crucis organised between 2011 and 2013 to reach the northern border, the one that took place in 2014, starting in Tenosique at Mexico’s southern border, actually made it all the way north (Martínez Hernández-Mejía Citation2018).

According to Varela Huerta and McLean (Citation2019, 176) these first few CMs Via Crucis were mostly performative and received support from religious congregations responsible for migrant shelters throughout Mexico. Yet these same religious groups had second thoughts when it became increasingly dangerous for migrants to engage in such performances, especially after the Mexican government adopted the Plan Integral para la Frontera Sur or the so-called Plan Sur to strengthen its southern border and increase surveillance of the southern border region (Martínez Hernández-Mejía Citation2018, 234–235). This Plan Sur was formulated around the same time that the humanitarian crisis of unaccompanied minors at the Mexican–US border reached unprecedented levels.

Although Mexican president Enrique Peña Nieto defended the Plan Sur as a humanitarian policy to protect migrants, its critics argued that it has led to increasing securitisation of Mexico’s policies towards Central American migrants (Marchand Citation2017a). Given the new context of the increased insecurity generated by the authorities and organised crime, the CMs organised since 2014 have changed. According to Varela Huerta and McLean, a new collective political identity emerged in relation to the transmigrants, and in particular the CMs:

From our perspective, in turn, what emerges with the consolidation of these kinds of collective political identities (those of the antiracist, non-clerical collectives that are not specifically dedicated to the humanitarian work of sheltering migrants) is a tension that will define the future of the migration industry over the next few years, and which will be a ‘toss-up’ between openly political antiracist and capitalist actions, challenging the current border regime, and the exercise in radical hospitality (also, from our perspective, highly political in this context) of providing humanitarian assistance to transmigrants. (Varela Huerta and McLean Citation2019, 178; translation by the author)

In other words, Varela and McLean are suggesting that a shift is taking place in the region’s migration industry: away from humanitarian assistance provided by religious groups and networks towards an agenda of political engagement pursued by groups defending migrants’ rights, suggesting increasing tensions between these two loosely organised networks. However, my research suggests that this shift is not clear cut, as the two networks have continued to collaborate and are complementary in that they address different needs of transmigrants.

These post-2014 CMs represent a new model of transmigration and are a response to the changing political and social context with which Central American migrants have to deal when crossing Mexican territory (Varela Huerta and McLean Citation2019). The new model of transmigration is a response to the multiple insecurities, generated by organised crime and the Mexican authorities in their implementation of Plan Sur, forcing Central American migrants to look for safer ways to travel north. These efforts have included the use of different routes and means of transportation, rather than the train ‘La Bestia’, and to travel in groups or Caravanas. In addition to migrants’ security, Varela Huerta and McLean identify three additional dimensions and reasons for the massive CMs organised from the spring of 2018 onward: the first one was that the starting date and departure location of the CMs were announced via social media; second, the CMs attracted the participation of entire families, including little children; and third, the CMs had the advantage of not being organised by migrant smugglers or ‘polleros’,Footnote 3 which considerably reduced the costs involved (Varela Huerta and McLean Citation2019).

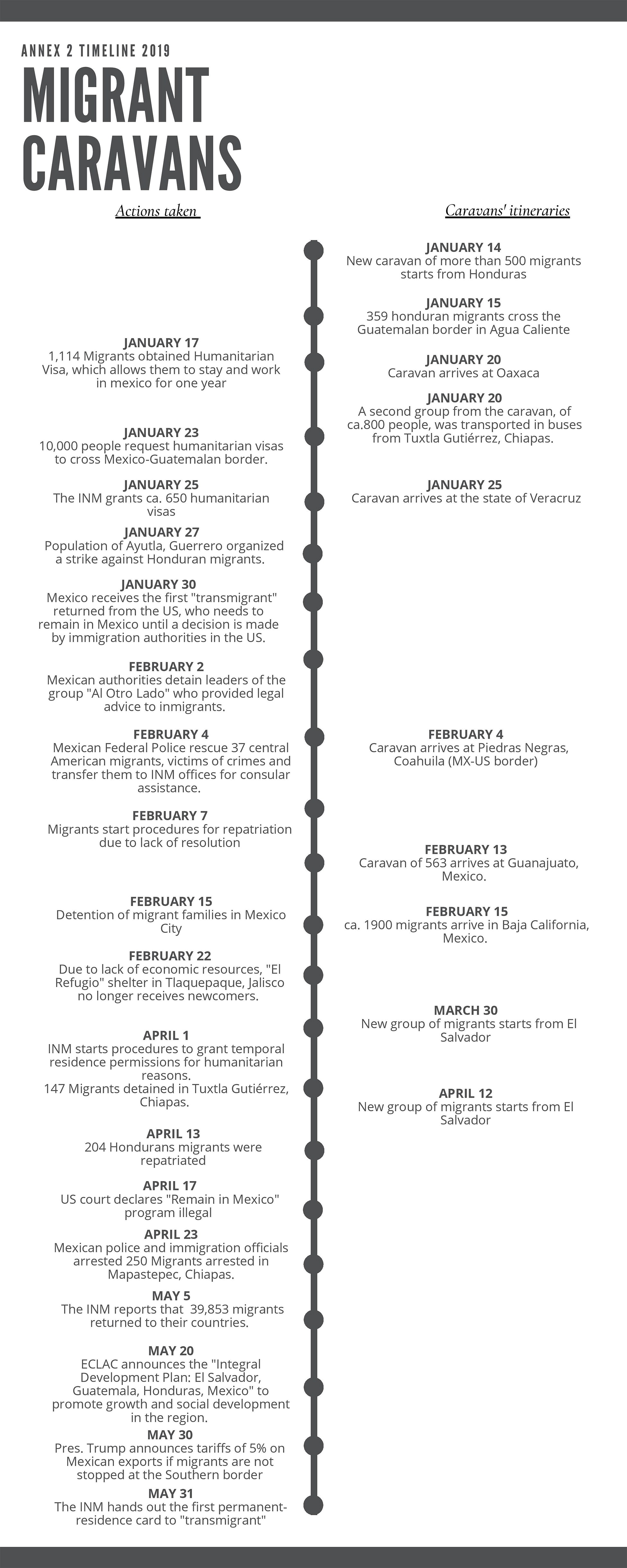

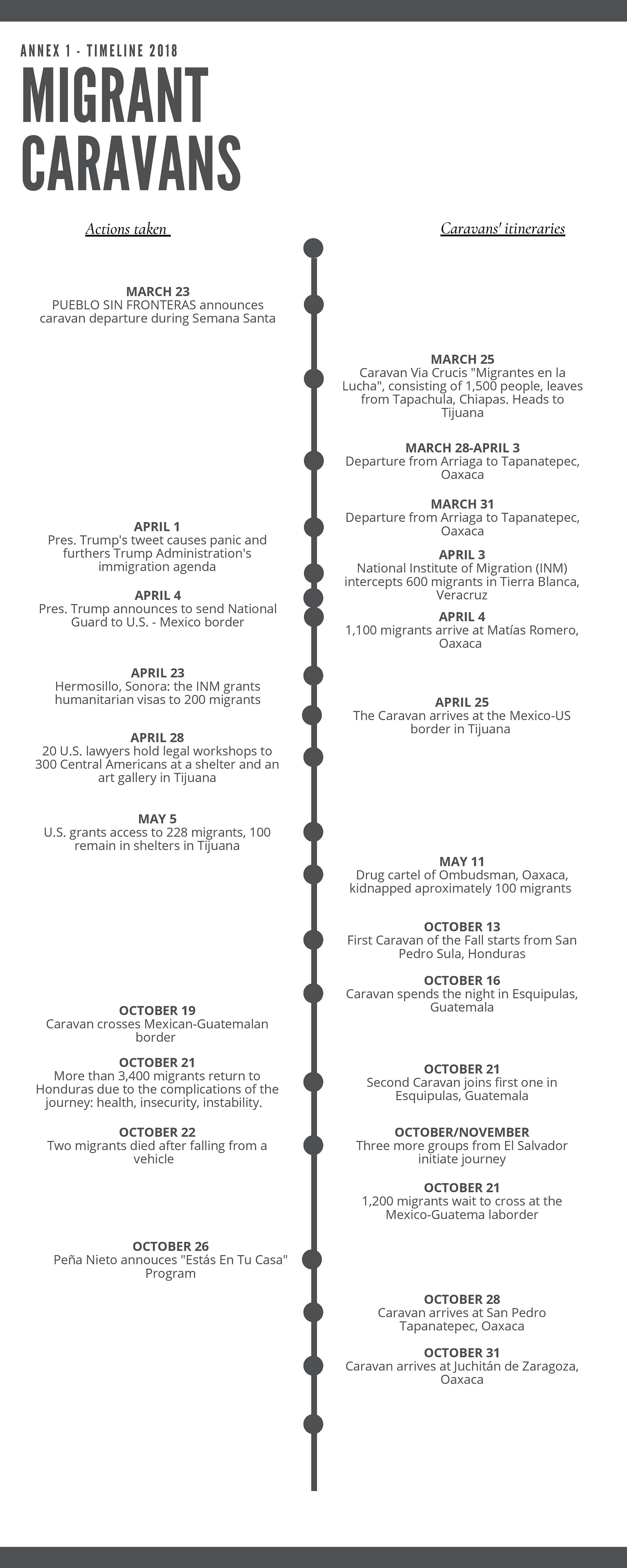

The first large CM that reflected these characteristics was the Caravana Vía Crucis ‘Migrantes en la Lucha’ of about 1500 people. It departed from Tapachula, Mexico, on 25 March 2018, during Holy Week or Semana Santa (see annexed Timeline 1). The transborder organisation Pueblo Sin Fronteras (PSF) in charge of this CM indicated that the main reasons for organising the CM were to protect migrants during their journey across Mexican territory and to call attention to the plight migrants are facing (@PuebloSF Citation2018; Pueblo Sin Fronteras Citation2020; Linthicum Citation2018). This time the CM attracted much more attention than the previous ones, not only because of its size but also because President Trump reacted to the CM via his tweets, suggesting that the CM was a national security threat to the US: ‘Getting more dangerous. “Caravans” coming’ (Trump Citation2018a). To this first tweet he added:

Mexico is doing very little, if not NOTHING, at stopping people from flowing into Mexico through their Southern Border, and then into the U.S. They laugh at our dumb immigration laws. They must stop the big drug and people flows, or I will stop their cash cow, NAFTA [the North American Free Trade Agreement]. NEED WALL! (Trump Citation2018b)

Initially, Mexican authorities were overwhelmed by the sheer size of the CM and let it proceed. Yet the size of the CM created many challenges, particularly for local (state and municipal) authorities as they were suddenly faced with an influx of people in their towns and cities. The CM also generated unprecedented challenges for existing migrant shelters that were not equipped to receive so many migrants simultaneously. In many cases local populations spontaneously started to collect and donate basic necessities such as soap and shampoo, food and clothing for the migrant shelters to support the CM.

A major bottleneck occurred in Tijuana, where the CM participants got stuck as US authorities only agreed to make appointments for a few migrants/asylum seekers at the time. So, again Tijuana needed to accommodate a large group of migrants, similar to what had happened a few years before with a group of ca. 8000 Haitian migrants (Marchand and Ortega Ramírez Citation2019). And, while it overwhelmed the local authorities and shelters, it also created resentment and xenophobic reactions among some of the Tijuanenses. However, despite such xenophobic reactions, a large part of the population still supported the CM.

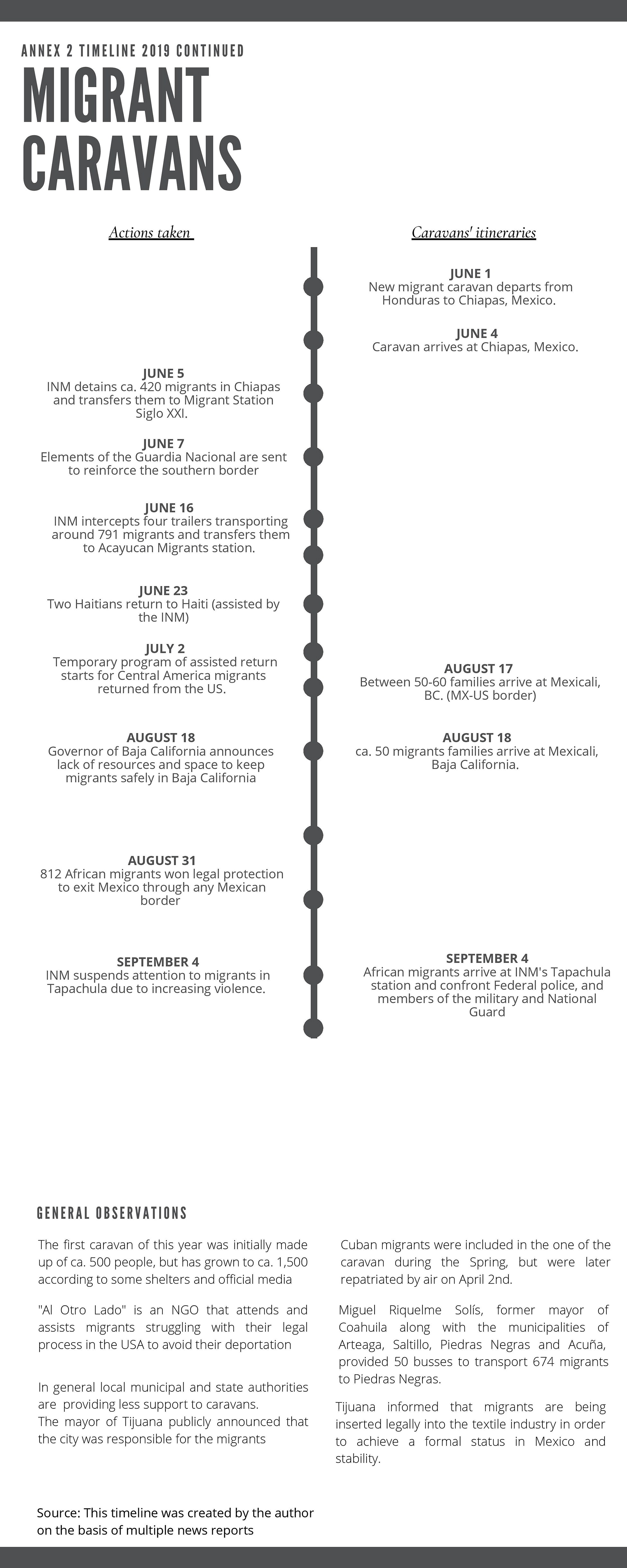

In the fall of 2018, a new wave of CMs started (see annexed Timeline 1). This time, they departed from Honduras, instead of Mexico, and it appears that PSF was not involved initially, although it decided to accompany the CMs throughout Mexican territory (Pueblo Sin Fronteras 2018). According to its press communiqués the group had some reservations about getting involved, as the spring 2018 CM had backfired, providing the Trump administration with additional arguments in support of its initiative to build a wall between Mexico and the US. Also, the various CMs that were initiated during the fall occurred under very different political conditions, as the US was absorbed by midterm elections and in Mexico the political transition from the Peña Nieto administration to the Lopez Obrador administration was in full swing. Despite its reluctance to get involved, PSF was attacked from various sides: while the Trump administration and some of its supporters claimed that the organisation was involved in the trafficking of persons, one of the most well-known migrant defenders in Mexico, Padre Solalinde, attacked the group for pursuing its own political objectives at the expense of the migrants. Furthermore, the group was being challenged for receiving many donations, but not spending them on the CM (Centro de Apoyo Marista al Migrante (CAMMI)), 2018; Linthicum Citation2018; Padre Gustavo, 2019b, Interview March 22). The controversy between Padre Solalinde, on one side, and PSF, on the other, was a reflection of the rift between the religious network providing humanitarian assistance and the non-religious network of migrants’ rights defenders identified by Varela Huerta and McLean (Citation2019; see above). Yet in practice the divides between these two networks were not clear cut and they continued to collaborate.

The Trump administration’s attacks on PSF for being involved in the trafficking of people are unfounded, reflecting a tendency of various governments to label organisations involved in supporting migrants through activities such as rescuing them at sea or providing them shelter as migrant smugglers or traffickers. These rescue activities pertain to the migration industry which Gammeltoft-Hansen and Nyberg Sørensen define as including three dimensions in total: that of actors facilitating migrants’ mobility; that of actors providing control ‘such as private contractors performing immigration checks, operating detention centers and/or carrying out forced returns’; and that of actors involved in the rescue industry, such as ‘NGOs [non-governmental organisations], social movements, faith-based organizations and migrant networks’ (Gammeltoft-Hansen and Nyberg Sørensen Citation2013, 6). According to Gammeltoft-Hansen and Nyberg Sørensen, the facilitating and rescuing dimensions of the migration industry should not be conflated or interchanged, as actors involved in the latter are usually not interested in financial gain, while service providers involved in facilitating mobility are receiving monetary remuneration (2013, 6).

Comparing the attacks by the Trump administration with Padre Solalinde’s critique of PSF, the latter’s critique rings more true: PSF engaged in crowd funding for its activities, but apparently did not share any of this with the migrant shelters in Mexico, while claiming that it had been using the funds to support migrants in the CMs (Freedom for Immigrants Citation2018; Linthicum Citation2018; Pueblo Sin Fronteras 2018; Padre Gustavo 2019b, Interview March 22). As I will discuss below, the attacks by the Trump administration as well as the controversy between Padre Solalinde and PSF appear to have generated some changes to the migration industry in the region, as Varela Huerta and McLean suggest in their discussion about the humanitarian activities of religious networks and activist networks in defence of migrants’ rights (Varela Huerta and McLean Citation2019, 181).

Since January 2019, at least four CMs left Honduras to make their trek north (see annexed Timeline 2). This time, the involvement of PSF was less clear and, according to one observer, they were ‘muy quemado’ (very burned) (Padre Gustavo, 2019b, Interview March 22). However, this does not mean that the CMs were ‘spontaneous’ events. As some observers suggest, the CMs were now organised by coyotes or polleros – in other words, migrant smugglers (Officer Instituto Nacional de Migración (INM) 2019, Interview March 24, 2019; Padre Gustavo 2019b, Interview March 22). This was a clear departure from 2018, when organisations defending migrants’ rights were in charge of organising the CMs. According to Padre Gustavo, the smugglers would ask migrants for money for taking them across to the US, but at the same time they were using the CMs to reduce their operational costs: benefitting from transportation that is sometimes offered for free by local communities or ordinary peopleFootnote 4 or using the shelters instead of hotels and safehouses for migrants to rest and get something to eat.

The new administration of President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (AMLO)Footnote 5 decided to deal with the CMs differently. It started to hand out humanitarian visas at the southern border, which allowed Central American migrants to stay in the country for one year and work. Initially, 15,000 humanitarian visas were handed out at the southern border and a little over 1000 at the northern border, in Piedras Negras and other border towns. The main reason for providing these humanitarian visas was the ability to keep track of how many migrants were entering the country and where they were staying. In addition, it gave migrants the option (and time) to apply for asylum or refugee status in Mexico, instead of in the US (Officer INM, Interview March 24, 2019). The practice of providing humanitarian visas had already started in the fall of 2018, apparently at the insistence of the transition team for the new AMLO administration (see ).

Table 1. Humanitarian visas issued by Mexican authorities.

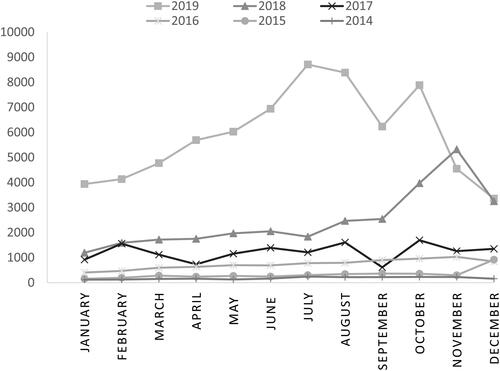

Both the number of humanitarian visas extended by the Mexican authorities and refugee claims by Central Americans have grown exponentially since the spring of 2018 (see and ). Yet, as the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) comments, filing an asylum claim is quite complicated in Mexico as the Comisión Mexicana de Ayuda a Refugiados (COMAR or Mexican Commission for Assistance to Refugees) is rather small and understaffed (UNHCR Citation2019). For instance, there are only two offices along the entire southern border of Mexico.

Figure 1. Monthly evolution of asylum claimants in Mexico (2014–2019).

Source: Comisión Mexicana de Ayuda a Refugiados (2020) Estadísticas de solicitantes de la condición de refugiado en México (Blog). March. Available from https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/544676/CIERRE_DE_MARZO_2020__1-abril-2020_-2__1_.pdf.

Unidad de Política Migratoria y Comisión Mexicana de Ayuda a Refugiados (2014–2018). Boletín Estadístico de Solicitantes de Refugio en México. Mexico, D.F.: Secretaría de Gobernación. http://portales.segob.gob.mx/es/PoliticaMigratoria/Refugio.

The situation around the CMs changed drastically in June 2019 when President Trump announced that the US would increase tariffs on Mexican exports by 5% per month, to a maximum of 25%, if Mexico did not take more drastic measures to prevent Central American migrants from reaching the US–Mexican border. In hindsight, it appears that negotiations between Mexican and American diplomats had already been going on since the spring, with the Mexican government agreeing to better ‘protect’ its southern border (Shear and Haberman Citation2019). The result was an increased militarisation of its southern border as the Mexican government sent about 6000 members of the National Guard to Chiapas. In addition, the government allowed Central American asylum seekers to wait in Mexico for their asylum or refugee claim to be resolved, something agreed under the Migrant Protection Protocols or Remain in Mexico programme (Holpuch Citation2019; Shear and Haberman Citation2019). These measures have stopped the CMs for the moment, and Central American migrants have now returned to previous forms of transiting Mexico, travelling in smaller groups and using alternative means of transportation, such as La Bestia, something they had been avoiding for a while (Padre Gustavo 2019a, communication, November 13). Moreover, at the moment of this writing, the COVID-19 pandemic has seriously interrupted migrant flows, as borders have been sealed off and shelters temporarily closed, thus making it impossible to organise new CMs. As noted in the introduction to this special issue, the medium- and long-term effects of the pandemic are difficult to measure at this point (Riemsdijk, Marchand, and Heins Citation2020).

While I have only highlighted a few details of these CMs, when they occurred in 2018 and the spring of 2019, in reality they involve a complex web of transnational actors and their positionalities, political strategies, media representations, and transnational organising. In the next section I will address some of the theoretical underpinnings which I will use in trying to analyse the CMs.

Migration governance: biopolitical struggles over the CMs

Biopolitics, an approach originally developed by Michel Foucault, is concerned with the ‘administering of life’ in order to make a state’s population productive (Foucault Citation1991). Against the background of the securitisation of migration and stricter border controls since the events of 11 September 2001, scholars have turned to Foucault’s insights for analysing migratory flows, transformations in border regimes and their concomitant institutional apparatus and technologies (Epstein Citation2007; Lemke Citation2001; Rygiel Citation2012; Salter Citation2007, Citation2013).Footnote 6

Foucault was in particular interested in how states exercise their power through biopolitics and what he called governmentality. The latter he defines as

the ensemble formed by the institutions, procedures, analyses and reflections, the calculations and tactics that allow the exercise of this very specific albeit complex form of power, which has as its target population, as its principal form of knowledge political economy, and as its essential technical means apparatuses of security. (Foucault Citation1991, 102)

Recently, scholars have stretched the concept of biopolitics in various ways. First, Achille Mbembe has built on the concept of biopolitics by introducing necropolitics as the administration of death. In his words, necropolitics create ‘new and unique forms of social existence in which vast populations are subjected to conditions of life conferring upon them the status of living dead’ (Mbembe Citation2003, 40). Necropower and necropolitics are used particularly in the context of post-colonial states in the Global South (Mbembe Citation2003). Given the high levels of state- and cartel-related violence in Mexico, his ideas are increasingly used to analyse the current situation in the country (Valencia Citation2010; Estévez Citation2014). The crudeness and level of violence perpetrated by the drug cartels are behind this interest in necropolitics. According to Ariadna Estévez (Citation2018), it is not a question of biopolitics versus necropolitics; rather, they are co-constitutive.

The idea that biopolitics can be exercised by non-state actors is not new. It is generally assumed that these non-state actors’ biopolitical practices are in concordance with the state’s overall objectives (Estévez Citation2014). However, some academics have stretched the concept of biopolitics by introducing the idea that non-state actors can pursue a biopolitics that contrasts with or contradicts that of the state. In her book Capitalismo Gore, Sayek Valencia (Citation2010) argues that the Mexican state and the drug cartels engage in parallel biopolitics as well as necropolitics. Discussing humanitarian intervention, which involves transnational actors such as Médicins sans Frontières, Didier Fassin (Citation2007) considers humanitarianism a form of biopolitics as it targets populations. However, he prefers the term ‘politics of life’ because for him humanitarian intervention is not really related to biopolitical techniques of power. In sum, Fassin acknowledges the limits to using the concept of biopolitics for humanitarianism, but still considers it a form of biopolitics.

In this article I will explore the idea that biopolitics can go beyond the state’s administration of life. In particular, I will analyse whether the organising of the CMs involves biopolitical practices or the administration of life of its participants. In other words, are the CMs the sites of biopolitics parallel to that of the state, or is their organisation in concordance with the state’s biopolitical objectives? As I will show, the CMs are situated in an entangled web of power struggles which have pitted several actors against each other in their respective attempts to articulate the CMs’ objectives, meaning and practices. The actors can be broadly divided into two groups: governmental or state-related actors on one side, and civil society groups on the other. Neither group is homogeneous, as they are made up of various national and transnational actors. I will also show how, in some instances, temporary alliances were forged between members of both groups. In other words, these groups are not mutually exclusive.

Governmental and state-related actors in search of managing the CMs

When the CMs appeared on Mexico’s southern border in the spring of 2018, the first reaction of the Mexican INM authorities was to allow them to continue their journey through Mexico. Three reasons accounted for this. First, the government of President Peña Nieto was already considered a ‘lame duck’, as electoral campaigns for the general elections of 1 July 2018 were in full swing.Footnote 7 This meant that the sitting administration was not willing or able to stop the CMs from moving north to the Mexico–US border. Second, over the years Mexican authorities have not really seen transit migration as a major problem, the implicit assumption being that migrants in transit would leave the country via the US–Mexican border and their presence would not really cause a problem for the Mexican state. When the authorities have tried to stop the flow of migrants crossing the southern border, it has often been in response to pressures from the US. A case in point is the Plan Frontera Sur implemented by the government of president Peña Nieto. Over the years Mexican governments have used their control over the southern border as a bargaining chip in their relations with the US, thus exercising a certain degree of autonomy in developing their own governmentality and not accepting unconditionally a role as buffer state (Marchand Citation2017b). A third reason for allowing the CMs to proceed was provided by the INM officer I interviewed: his rather cynical reading of the situation suggests that the Trump administration actually wanted the CMs to advance to the Mexican–US border in order to have more arguments to build the wall (Interview March 24, 2019).

During subsequent CMs in the fall of 2018 and the spring of 2019, the Mexican authorities started to apply different biopolitical techniques. The most important of these was to hand out humanitarian visas to transit migrants presenting themselves at the southern border. Although information is not available about the kind of collaboration that occurred between the team of outgoing president Peña Nieto and the transition team of president Lopez Obrador (AMLO), it seems likely that the two sides consulted on how to deal with the CMs. On 26 October 2018, the Departments of Internal Affairs (Secretaría de Gobernación or SEGOB) and of Foreign Affairs (Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores or SRE) announced a new policy with respect to the CMs: Plan ‘Estás en tu Casa’ (translation: Plan ‘You are at Home’). The Plan ‘Estás en tu Casa’ had two major components:

Immigrants who present themselves before the migration authorities and request to do so can access the Program for Temporary Employment (PET) in the states of Chiapas and Oaxaca under the rules of operation of existing programmes.

Obtaining a temporary population ID (Clave Única de Registro de Población or CURP) for foreigners assures that immigrants have legal proof of identity and can exercise their rights when accessing the services provided by the Mexican state […]. (SRE-SEGOB Citation2018; translation by the author)

The implication of this new policy for Central American migrants was that they had to regularise their immigrant situation by presenting themselves to the migration authorities, and present a claim as asylum seeker. Having registered, they would be allowed to engage in certain types of work, such as ‘social infrastructure’ – defined as the ‘repair, maintenance and cleaning’ of ‘roads, streets and public spaces’ – in parts of Chiapas and Oaxaca (SRE-SEGOB 2018). Unfortunately, there is little, if any, information about whether immigrants actually signed up for the programme. However, it is very unlikely that many Central American immigrants signed up, as most intended to reach the US. Moreover, the possibility for immigrants to participate in the PET was limited as the programme terminated at the end of 2018, when president Peña Nieto left office. This meant that they had less than a month to register and be accepted in the PET before the fiscal year closed.

In January of 2019, the new AMLO administration increased the number of humanitarian visas handed out at Mexico’s southern border, but these were now considered a requirement for entering the country. Numbers skyrocketed, as more than 15,000 visas were handed out in just a month’s time (see ). As the INM officer commented: ‘I was there in Chiapas, in Ciudad Hidalgo, at the border. We gave 15,000 visas for humanitarian reasons’ (Interview March 24, 2019). The INM officer details the issuing of humanitarian visas at the border, recalling the questions that were asked, how immigrants were responding and his personal perceptions about the way things were handled at the border:

Q: Why are you fleeing from your country?

A: Because of the violence in Honduras, Salvador, Guatemala.

The three [immigrants originating from these countries] gave you the same answer.

Q: And for what are you coming?

A: And they all tell you that they come to work in Mexico and they don’t tell you that they want to go to the USA.

Look, of the 15,000 humanitarian visas [handed to the people] who said that they were coming to work, of the 15,000, they did not fill a single truck of a company that offered work, a good job, with housing, medical services, a very good company. Not a single truck for 40 people was filled from the 15,000.

But there are people who have tattoos from the Mara Calle 13, so it is known that it is a criminal. For them they [usually] request an international police alert. But in the situation of the 15,000 that was not done. (Interview INM officer March 24, 2019; translation by the author)

It is clear that the INM officer I interviewed did not feel comfortable with the way the situation was handled at the border. He summarises his perceptions as follows:

It is bad, because they are lying to me from the beginning. They want you to fill out everything [the forms] and they declare that they cannot write. There is no time to really check whether they know or not [how to write]. So, everyone crosses the border, whoever they are. So, there was no real data control or verification [….]. They gave thousands of visas because of a political strategy, because I don’t see a logical migratory strategy. (Interview INM officer, March 24, 2019; translation by the author)

While the federal authorities were designing their own strategies in dealing with the CMs, municipal and state governments were also put to the task of having to deal with the flow of people coming through their communities, a task that overwhelmed many of them and generated different responses. For instance, as was already mentioned, the state of Veracruz provided buses to migrants to continue on their way north. The governor of Puebla, Tony Gali, said in an interview: ‘We have to open doors. Puebla has always been an open city, a city without walls, a city that receives visitors, in this case migrants, with open arms’. He also added that ‘they will be given the necessary attention, such as food and health care’ (quoted in De la Luz Citation2018; translation by the author).

Although many of the local authorities were well-intentioned, in particular because of large-scale media attention and being under the watchful eye of observers from the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH), the UNHCR, COMAR and human rights organisations such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, their actions were mostly improvised. The INM officer describes this situation as follows:

So, the technique was that I, municipal president, was here at the highway [between] Chiapas, Tijuana, [or] Cd. Juárez. Everyone who comes through here is part of the Caravan and in the small towns they are organising a party for them, they even give them water so they can bathe. And the next day they take them to the next one [town] in cargo trucks, even in the municipal president’s van, if necessary. And they send them again onward. It is a chain. (Interview INM officer, March 24, 2019; translation by the author)

Incapable of dealing with the CMs by themselves, local authorities collaborated increasingly with migrant shelters and migrant activists or defenders of migrants’ rights. According to Padre Gustavo, this entailed a significant change in the relations between state authorities and migrant shelters, as before he had been under surveillance by the authorities and even received serious threats. To deal with the CMs in Puebla, state authorities set up a temporary shelter at the edge of town that could receive more than 1000 people at a time (Interview with state official, November 7, 2019). State officials coordinated with the shelters run by the Catholic church, providing basic necessities for immigrants such as hygiene kits, medical services and some food supplies. At the same time, they were also registering and gathering data on the immigrants. As both the shelters and local governments were not really prepared for the large groups of people coming through, an ad hoc collaboration emerged between the two parties. While the shelters had the advantage of having considerable experience in attending the needs of migrants in transit, the authorities could access more resources to cover the basic needs of the people in the CMs.

With the issuing of thousands of humanitarian visas, the Peña Nieto and AMLO administrations reverted to basic techniques of biopolitics. Federal, state and local state apparatuses used different techniques to manage the flow of migrants. The main intent was to spatially control the CMs by having people move steadily across Mexican territory to the northern border and eventually cross into the US. As it became increasingly clear that the situation at the northern border was untenable, because the US introduced the Remain in Mexico programme and would only schedule a few interviews at a time with Central American asylum seekers, Mexican authorities resorted to a range of ad hoc measures to manage the flow of people in its territory. The PET is one of the more interesting but also ‘hollow’ examples of such measures, because few migrants benefitted from the programme. As migrants were to be paid less than Mexican workers under the PET, the Mexican state also resorted to what Claudia Arauda and Martina Tazzioli (Aradau and Tazzioli Citation2020) have called ‘extractive biopolitics’. For Arauda and Tazzioli, extractive biopolitics refers to the ‘modes of value extraction from migrants’ mobility’ (Aradau and Tazzioli Citation2020, 203). The PET performed such extractivism on Central American migrant bodies, targeting them for public works (but paying less than the minimum wage).

The extractive techniques applied by Mexican authorities were not as well-developed as the ones used by their Greek counterparts in dealing with massive migrant or refugee flows. In Greece, Syrian refugees were handed prepaid cards by UNHCR linking them to the digital economy. As Aradau and Tazzioli argue, these ‘new modes of cash assistance and debit card use in governing migration can be read as extractive technologies that datafy refugees’ movements and enable access to the material infrastructures of digital economy’ (Aradau and Tazzioli Citation2020, 219–220). While in Mexico the registration of migrants did not involve issuing debit cards, assigning a CURP to migrants and asylum seekers receiving a humanitarian visa allowed for their datafication.

In sum, during the period of 2018–2019, temporary, unstable assemblages, such as the collaboration between the shelters and authorities in the state of Puebla, were created. These involved changes in the biopolitical techniques applied to migrants: from an attitude of relative neglect towards transit migrants to biopolitical techniques intended to control and channel the CMs in Mexican territory.

Non-state actors engaging in a biopolitics ‘from below’?

Usually, non-state actors’ involvement in biopolitics or the administration of life amounts to what is described in the previous section: supporting the overall biopolitical designs of the state. Yet in the case of the CMs, different groups have engaged in what I will call a biopolitics from below. Three such non-state actors involved in the organisation and managing of CMs or migrants in transit are non-religious organisations defending migrants’ rights, religious networks managing migrant shelters, and smugglers.

Organisations defending migrants’ rights, such as PSF, constitute an important group of actors involved in the managing of migrants moving across Mexican territory. With the organisation of the CMs, PSF had a dual objective: the first was to provide protection to Central American migrants who intended to cross Mexico in order to get to the US; secondly, they pursued a political strategy directed at the Trump administration which consisted of demonstrating that the anti-immigrant policies of the administration would lead to a humanitarian crisis. One of the biopolitical techniques applied was to convince migrants to continue their trek north and not stay behind or rest too long on the way. There is anecdotal evidence that PSF would tell migrants not to stay in certain shelters or consider the option of applying for asylum in Mexico (Padre Gustavo 2019b, Interview March 22). As explained before, this is one of the reasons why Mexican migrant activists, such as Padre Solalinde, distanced themselves from PSF, arguing that the organisation was using migrants for its own political strategies. These two positions towards the CMs put into perspective Fassin’s argument about humanitarianism as a politics of life: while the religious networks involved in sheltering reflected Fassin’s position, PSF, as exponent of the non-religious migrants’ rights activist networks, was applying biopolitical techniques of power directed at the state (Fassin Citation2007; see also Varela Huerta and McLean Citation2019).

Religious networks in charge of migrant sheltering in Mexico constitute a second group of non-state actors. They were the ones who locally organised the reception of migrants, providing them with basic needs such as food, clean clothes, toiletries and a shower, some medical attention and clinics to inform them of their rights and asylum procedures. As documented in the article by Merlín-Escorza, Davids, and Schapendonk (Citation2020) in this volume, the shelters have set up elaborate procedures for the intake of migrants, establishing rules of behaviour and assuring the security of both migrants and volunteers working at the shelters.

Particularly in the case of Puebla, many young people, who had been mobilised in the aftermath of the earthquake of September 2017, now became involved in attending the migrants who passed through (Padre Gustavo, 2019b, Interview March 22). According to Padre Gustavo, their involvement really helped with raising consciousness among the general population. During the first wave of CMs, the general public’s opinion in Puebla towards the CMs was relatively positive and many people donated food, clothing and other necessities. But this attitude started to change with subsequent CMs. Also, some volunteers at the migrant shelter voiced concerns about the behaviour of a few migrants in subsequent CMs.

Smugglers or polleros make up another group of non-state actors involved in applying biopolitical techniques to the CMs. They copied techniques used by PSF in methodically organising the CMs: starting with small groups of five people, then bringing 10 of these together into larger 50-person groups, and so on. This was done so that migrants could keep track of each other. Different groups were responsible for different tasks, including providing security for those participating in the CMs (Padre Gustavo 2019b, Interview March 22). However, the role of the smugglers was controversial. As mentioned before, the smugglers benefitted from the shelters as the latter provided basic necessities to the migrants for which the smugglers did not have to pay. While the large majority of migrants were grateful for this support, a few of them travelling with the subsequent CMs were asking for brand-name clothes. This clearly upset some of the volunteers at the shelter run by Padre Gustavo. The volunteers suspected that these migrants were in fact smugglers (Padre Gustavo 2019b, Interview March 22). Other observers appear to corroborate that smugglers were travelling with and organising the CMs. According to a state official who was working for the Puebla Institute for the Attention to Migrants (IPAM).Footnote 8

We could detect that many leaders that were bringing them from their home countries had to reunite in Mexico City with other leaders.

Interviewer: Or smugglers?

State official: I would not dare to call them smugglers because we are talking multitudes, and we heard the rumor that migrant groups from San Diego, Los Angeles, in Oregon were economically sponsoring these Caravans. It is curious, including it could be a coincidence, because many women, men, young people had iPhones!

They were bringing their cables to charge them and they would fight to connect their phones to the extensions, and many asked us to help them to get their dollars from the OXXO [convenience] stores. So, the rumor that they were sponsored from the United States makes sense.

And it was very curious because many of them did not want to eat canned tuna, beans, bread rolls or sandwiches anymore. They now asked for a meal, different types of meals, and it was very visible the fact how these migrants travelled, compared to the migrants that travel on La Bestia. The migrant who travels on La Bestia is a migrant who has not bathed in at least a month, who has suffered extreme conditions in terms of cold [temperatures], water, food, including violence from the networks that circulate around the railroads and the criminal groups who are also taking advantage of this …. They are persons who come very worn out, their appearance and odor are highly perceptible. And it was not the same in the CMs, because even mothers with strollers came … Mothers came with a stroller to the shelter. What are we talking about? A mother who is bringing a baby in a stroller cannot bring him walking from Chiapas to here. (State official, Interview, November 7, 2019; translation by the author)

While the official did not want to confirm that some of migrants in the CMs were in fact smugglers, he did acknowledge that there were some changes in the attitudes and behaviour of the migrants in the CMs. His comparison with migrants who travel on the train La Bestia suggests that, in his view, there are some migrants who are truly in need of attention by the authorities or shelters and others who seem to take advantage of the situation.

As already mentioned, the smugglers also managed the CMs by moving them along previously defined trajectories, sometimes not allowing migrants to go to rest in certain shelters and also discouraging them from applying for asylum in Mexico. However, unlike PSF, the smugglers were apparently not interested in amassing migrants in a few border towns, particularly in Tijuana, so as to make a political statement. Instead, they channelled people to other border towns, such as Piedras Negras. And when the large-scale CMs suddenly ended in June 2019 because of the agreement between the AMLO and Trump administrations, the smugglers quickly changed their modus operandi, and migrants started to travel in small groups again and on La Bestia (Padre Gustavo 2019a, Communication, November 13). In other words, the smugglers were quite flexible in adapting their biopolitical techniques to changing circumstances.

Why consider these activities by migrant shelters and migrant rights’ activists as well as smugglers a form of biopolitics from below? The activities of the different non-state actors described in this section involve the administering of migrants’ lives through the mobilisation of flows of people across Mexican territory. These different actors may well have different purposes for so doing, ranging from political motivations in the case of PSF to humanitarian reasons for the shelters and migrant activists, to economic gain in the case of the smugglers.

Interestingly, each of these non-state actors is creating a productive population in line with their objectives, and often in opposition to the biopolitics of either the Mexican or the US state. PSF was interested in protecting Central American migrants from the violence perpetrated by organised crime and Mexican authorities. According to most accounts, its other main objective was to create a crisis for the Trump administration at the US–Mexico border and challenging its restrictive migration policies, including building a wall along the border.

The religious networks related to the shelters focussed primarily on humanitarian activities. On one side, they coincided with PSF in developing biopolitical strategies to protect migrants, by providing basic needs and legal support. On the other, they collaborated with Mexican authorities in managing the CMs. Over the years, the shelters have also developed practices to ensure that they remain safe places for migrants, by keeping out those whom they consider potential troublemakers, such as gang members, smugglers, drug addicts and migrants manifesting violent behaviour. As many shelters are now organised in networks, information about such potential troublemakers is passed along (Padre Gustavo 2019b, Interview, March 22; see also Merlín-Escorza, Davids, and Schapendonk Citation2020). These practices amount to basic biopolitical techniques of separating desirable from undesirable population groups. In sum, the shelter-related religious networks are in line with Fassin’s (Citation2007) concept of the ‘politics of life’.

The role of the polleros or coyotes in the CMs is similar to that of PSF, as they copied some of its techniques in organising the CMs. Yet their motivation is quite different, because their main objective is economic gain. So, at a basic level, these polleros or coyotes have a general interest in speedily moving migrants across Mexican territory at the highest possible gain, by not having to pay for their food, shelter, transportation and other basic necessities. Their biopolitical strategy consists of managing flows of people and generating a productive population that will guarantee their smuggler’s fee.

Conclusion

The main argument of this article is that the state is not the only actor engaging in a biopolitics directed at transmigrants. In analysing the events around the CMs it argues that, in the words of Arauda and Tazzioli (Citation2020), a ‘biopolitics multiple’ has emerged, with non-state actors also developing biopolitical strategies concerning the CMs. Non-state biopolitics may collude with the biopolitical objectives of the state, but they occasionally undermine or challenge these. While Aradau and Tazzioli do not directly discuss the role of non-state actors in biopolitics towards migrants, their dual concept of extractive and subtractive biopolitics opens up space for including biopolitical practices by actors other than the state.

In the case of the CMs that crossed Mexican territory between the spring of 2018 and June of 2019, different actors have engaged in a biopolitics directed at transmigrants. Some of their activities amounted to biopolitical contestations between the different groups involved; others were articulated as part of emerging, but rather unstable constellations. Based on my analysis, I find at least three such constellations. The first is created between local governments and religion-based shelter networks. The main objective of this alliance was to provide basic needs to large groups of migrants as they came through. This alliance was rather unlikely a few years ago, when local authorities would often threaten the activists working at the shelters. However, the constellation is rather unstable, as changes in the politics of local governments are quite frequent and unpredictable.

The second constellation occurred around the actual organising of the CMs, and includes PSF, as exponent of migrants’ rights activists; religious activists involved with the shelters; migrant smugglers; and migrants themselves. While it brings together different interests and objectives, it shares the overall objective of protecting Central American migrants. Two phases can be distinguished in this constellation. During the first phase, lasting all of 2018, PSF was mostly in charge of organising the CMs. However, the diverging objectives between PSF and the religious networks around the shelters strained their relations.

During the second phase, from January to June 2019, migrant smugglers appear to have taken over the role of PSF in organising the CMs, collaborating with Central American migrants based in Honduras and elsewhere. While this constellation involves the shelters, some of the shelters’ volunteers voiced concerns about the role of the smugglers. In sum, this constellation is plagued by internal rifts created by PSF’s biopolitics for political gain, the smugglers’ biopolitical interests in economic gain and the religious networks’ politics of life.

The third constellation was made up of different branches of the Mexican federal government, in particular the INM, COMAR and CNDH, with a supporting role for the UNHCR as well as other international organisations. The overall shared objective was the issuance of humanitarian visas and providing the option to request asylum in Mexico. For the Mexican authorities, these humanitarian visas allowed them to track the whereabouts of the migrants. For the UNHCR, which was working closely with COMAR, the humanitarian visas ensured temporary legal status and human rights protection in Mexico to Central American migrants. The US government actually opposed the issuance of humanitarian visas at Mexico’s southern border, arguing that this would facilitate the mobility of transmigrants across Mexican territory. Yet it benefitted from their issuance, as Central American migrants increasingly considered applying for asylum in Mexico, thus indirectly making the US government part of the constellation.

When migrants continued to show up at the US–Mexico border in the spring of 2019, the Trump administration put additional pressure on the Mexican government. As a result, the Mexican government deployed the National Guard, leading to an increased militarisation of its southern border. At the same time, it accepted the so-called Migrant Protection Protocols or Remain in Mexico programme, which meant that Central American migrants had to wait at Mexico’s northern border for their asylum claim in the US to be processed.

While these three constellations are unstable and may change due to the volatile situation, there is also a possibility that these alliances will transform into more or less stable assemblages, in particular when accompanied by, or linked to, physical or programmatic infrastructures. What the present article shows is that biopolitics is not just emanating from the state or supporting states’ objectives. In the case of the migrant caravans, we need to entertain the idea that non-state actors are pursuing their own biopolitics, which may diverge from those of the state. As such, these divergent, non-state biopolitics add a new dimension to migration governance architectures and may even undermine them (see the introduction to this special issue).

Acknowledgements

I want to thank the Käte Hamburger Kolleg/Centre for Global Cooperation Research, University of Duisburg-Essen, for its generous support. Moreover, I want to thank my colleagues Guy Emerson and Leandro Rodriguez Medina for engaging/discussing with me the topic of extending the concept of biopolitics to non-state actors. Finally, my thanks go to my research students Mariana Granados Carranza, Elba Alejandra Pérez López, and Samantha Leticia Tapia Lozano for their research support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Marianne H. Marchand

Marianne H. Marchand holds a Chair in International Relations in the Department of International Relations and Political Science at the Universidad de las Américas Puebla (Mexico). She is also an Associate Senior Fellow at the Käte Hamburger Kolleg/Centre for Global Cooperation Research, University of Duisburg-Essen. Her research focuses on migration and borders, worlding cities in the Global South, and gender and global restructuring.

Notes

1 CMCMD – Caravans of Central American Mothers of Disappeared Migrants.

2 AMIREDIS – Association of Returned Migrants with Disabilities.

3 The terms pollero and coyote are often used interchangeably, both referring to migrant smugglers. However, sometimes migrants make a distinction between the two: a pollero is the person who brings people from their hometowns to the border and the coyote is the person who takes them across the border.

4 This happened more in the fall of 2018 when, for instance, the state of Veracruz provided autobuses to transport migrants across its territory.

5 The presidency of AMLO was initiated on 1 December 2018.

6 For a more detailed account, see my research on Mexican governmentalities, migration and border crossings (Marchand Citation2017a, Citation2017b).

7 In Mexico politicians cannot be re-elected, which means that the outgoing president and the cabinet are left with relatively little power in the last year of being in office. Moreover, in the months leading up to elections, government spending on a wide range of social programmes is prohibited by law, giving the authorities little room for manoeuvre.

8 In Spanish: Instituto Poblano de Atención a Migrantes.

Bibliography

- Aradau, Claudia , and Martina Tazzioli . 2020. “Biopolitics Multiple: Migration, Extraction, Subtraction.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 48 (2): 198–220. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0305829819889139.

- Centro de Apoyo Marista al Migrante (CAMMI) . 2018. “Caravana 2018, Viacrucis Migrantes en Lucha.” Comunicado, April 19. https://www.facebook.com/cammigrante/photos/a.1474187436185548/2050679868536299.

- De la Luz, Verónica . 2018. “En Caravana, pasan por Puebla alrededor de mil 200 migrantes.” El Sol de Puebla, November 4. https://www.elsoldepuebla.com.mx/local/en-caravana-pasan-por-puebla-alrededor-de-mil-200-migrantes-2615242.html.

- Epstein, Charlotte . 2007. “Guilty Bodies, Productive Bodies, Destructive Bodies: Crossing the Biometric Borders.” International Political Sociology 1 (2): 149–164. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-5687.2007.00010.x.

- Estévez, Ariadna . 2018. “Biopolítica y Necropolítica: ¿Constitutivos u Opuestos?” Espiral Estudios Sobre Estado y Sociedad 25 (73): 9–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.32870/espiral.v25i73.7017.g6149.

- Estévez, Ariadna . 2014. “The Politics of Death and Asylum Discourse: Constituting Migration Biopolitics from the Periphery.” Alternatives: Global, Local, Political 39 (2): 75–89. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0304375414560465.

- Fassin, Didier . 2007. “Humanitarianism as a Politics of Life.” Public Culture 19 (3): 499–520. doi:https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-2007-007.

- Foucault, Michel . 1991. “Governmentality.” In The Foucault Effect: Studies in Governmentality , edited by G. Burchell , C. Gordon & P. Miller , 87–104. Hemel Hempstead: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

- Freedom for Immigrants . 2018. “Pueblo Sin Fronteras/Stand with the Central American Migrant Caravan! (Crowd Funding).” October 25. https://charity.gofundme.com/o/en/campaign/support-the-migrant-caravan.

- Gammeltoft-Hansen, Thomas , and Ninna Nyberg Sørensen . 2013. “Introduction.” In The Migration Industry and the Commercialization of International Migration , edited by T. Gammeltoft-Hansen and N. Nyberg Sørensen , 1–23. London: Routledge.

- Holpuch, Amanda . 2019. “Amnesty Leaders Condemn US’s Remain in Mexico Policy as ‘Disgrace’.” The Guardian, October 25. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/oct/25/amnesty-international-us-immigration-mexico-international-disgrace.

- Lemke, Thomas . 2001. “The Birth of Bio-Politics: Michel Foucault’s Lecture at the Collège De France on Neo-Liberal Governmentality.” Economy and Society 30 (2): 190–207. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03085140120042271.

- Linthicum, Kate . 2018. “Pueblo Sin Fronteras Uses Caravans to Shine Light on the Plight of Migrants — But has that Backfired?” Los Angeles Times, December 6. https://www.latimes.com/world/mexico-americas/la-fg-mexico-caravan-leaders-20181206-story.html.

- Marchand, Marianne H . 2017a. “Crossing Borders in North America after 9/11: ‘Regular’ Travellers’ Narratives of Securitisations and Contestations.” Third World Quarterly 38 (6): 1232–1248. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2016.1256764.

- Marchand, Marianne H . 2017b. “Crossing Borders: Mexican State Practices, Managing Migration and the Construction of “Un-Safe Travelers.” Latin American Policy 8 (1): 5–26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/lamp.12118.

- Marchand, Marianne H. , and Adriana Sletza Ortega Ramírez . 2019. “Globalising Cities at the Crossroads of Migration: Puebla, Tijuana and Monterrey.” Third World Quarterly 40 (3): 612–632. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2018.1540274.

- Martínez Hernández-Mejía, Iliana . 2018. “Reflexiones Sobre la Caravana Migrante.” Análisis Plural 2018 (5): 231–239. https://rei.iteso.mx/bitstream/handle/11117/5616/S3%20Reflexiones%20sobre%20la%20caravana%20migrante.pdf?sequence=2.

- Mbembe, Achille . 2003. “Necropolitics.” Public Culture 15 (1): 11–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-15-1-11.

- Merlín-Escorza, César E. , Tine Davids , and Joris Schapendonk . 2020. “Sheltering as a Destabilising and Perpetuating Practice in the Migration Management Architecture in Mexico.” Third World Quarterly . doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2020.1794806.

- Noticias de América Latina y el Caribe (NODAL) . 2019. “Caravana de Madres Centroamericanas de Migrantes Desaparecidos finalizan recorrido por México.” December 4. https://www.nodal.am/2019/12/caravana-de-madres-centroamericanas-de-migrantes-desaparecidos-finalizan-recorrido-por-mexico/.

- @PuebloSF . 2018. https://www.facebook.com/page/214556975237678/search/?q=caravana%20migrantes%20en%20la%20lucha.

- Pueblo Sin Fronteras. 2020. https://www.pueblosinfronteras.org/viacrucis.html.

- Pueblo Sin Fronteras. 2018. Statement . November 26. https://www.facebook.com/PuebloSF/posts/24717023628564509.

- Riemsdijk, Micheline van , Marianne H. Marchand , and Volker Heins . 2020. “New Actors and Contested Architectures in Global Migration Governance: An Introduction.” Third World Quarterly .

- Rygiel, Kim . 2012. “Governing Mobility and Rights to Movement Post 9/11: Managing Irregular and Refugee Migration through Detention.” Review of Constitutional Studies/Revue D’études Constitutionnelles 16 (2): 211–241.

- Salter, Mark B . 2007. “Governmentalities of an Airport: Heterotopia and Confession.” International Political Sociology 1 (1): 49–66.

- Salter, Mark B . 2013. “To Make Move and Let Stop: Mobility and the Assemblage of Circulation.” Mobilities 8 (1): 7–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2012.747779.

- Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores and Secretaría de Gobernación (SRE-SEGOB) . 2018. “El Presidente Enrique Peña Nieto Anuncia el Plan “Estás en tu Casa” en Apoyo a los Migrantes Centroamericanos que se Encuentran en México.” Comunicado Conjunto No. 7 SRE-SEGOB, October 26. https://www.gob.mx/sre/prensa/el-presidente-enrique-pena-nieto-anuncia-el-plan-estas-en-tu-casa-en-apoyo-a-los-migrantes-centroamericanos-que-se-encuentran-en-mexico?idiom=es

- Shear, Michael D. , and Maggie Haberman . 2019. “Mexico Agreed to Take Border Actions Months Before Trump Announced Tariff Deal.” New York Times, June 8. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/08/us/politics/trump-mexico-deal-tariffs.html.

- Trump, Donald [realDonaldTrump] . 2018a, April 1. “Border Patrol Agents are not Allowed to Properly do their Job at the Border because of Ridiculous Liberal (Democrat) Laws like Catch & Release. Getting More Dangerous. “Caravans” Coming. Republicans must go to Nuclear Option to pass tough laws NOW. NO MORE DACA DEAL! [Tweet].” https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/980443810529533952.

- Trump, Donald [realDonaldTrump] . 2018b, April 1. “Mexico is doing very little, if not NOTHING, at stopping people from flowing into Mexico through their Southern Border, and then into the U.S. They Laugh at our Dumb Immigration Laws. They must stop the Big Drug and People Flows, or I will Stop their Cash Cow, NAFTA. NEED WALL! [Tweet].” https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/980451155548491777.

- Unidad Política Migratoria, Secretaría de Gobernación . 2018. “Boletín Mensual de Estadísticas Migratorias.” http://www.politicamigratoria.gob.mx/work/models/PoliticaMigratoria/CEM/Estadisticas/Boletines_Estadisticos/2018/Boletin_2018.pdf.

- Unidad Política Migratoria, Secretaría de Gobernación . 2019. “Boletín Mensual de Estadísticas Migratorias.” http://www.politicamigratoria.gob.mx/work/models/PoliticaMigratoria/CEM/Estadisticas/Boletines_Estadisticos/2019/Boletin_2019.pdf.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees . 2019. “Factsheet Mexico, April.” https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/UNHCR%20Factsheet%20Mexico%20-%20April%202019.pdf.

- Valencia, Sayek . 2010. Capitalismo Gore . Barcelona: Editorial Melusina.

- Varela Huerta, Amarela , and Lisa McLean . 2019. “Caravanas de Migrantes en México: Nueva Forma de Autodefensa y Transmigración.” Revista CIDOB D’Afers Internacionals 122: 163–185. https://www.cidob.org/es/articulos/revista_cidob_d_afers_internacionals/122/caravana_de_migrantes_en_mexico_nueva_forma_de_autodefensa_y_transmigracion.

- Vargas Carrasco, Felipe de Jesús . 2018. “El Vía Crucis Del Migrante: Demandas y Membresía.” Revista Trace 73 (73): 117–133. http://trace.org.mx/index.php/trace/article/view/88/pdf. doi:https://doi.org/10.22134/trace.73.2018.88.

- Web Radio Migrantes-Español . 2018. “Caravana de Madres Centroamericanas de Migrantes Desaparecidos. October 16. http://www.radiomigrantes-es.net/noticias/general-1/16-10-2018/caravana-de-madres-centroamericanas-de-migrantes-desaparecidos.

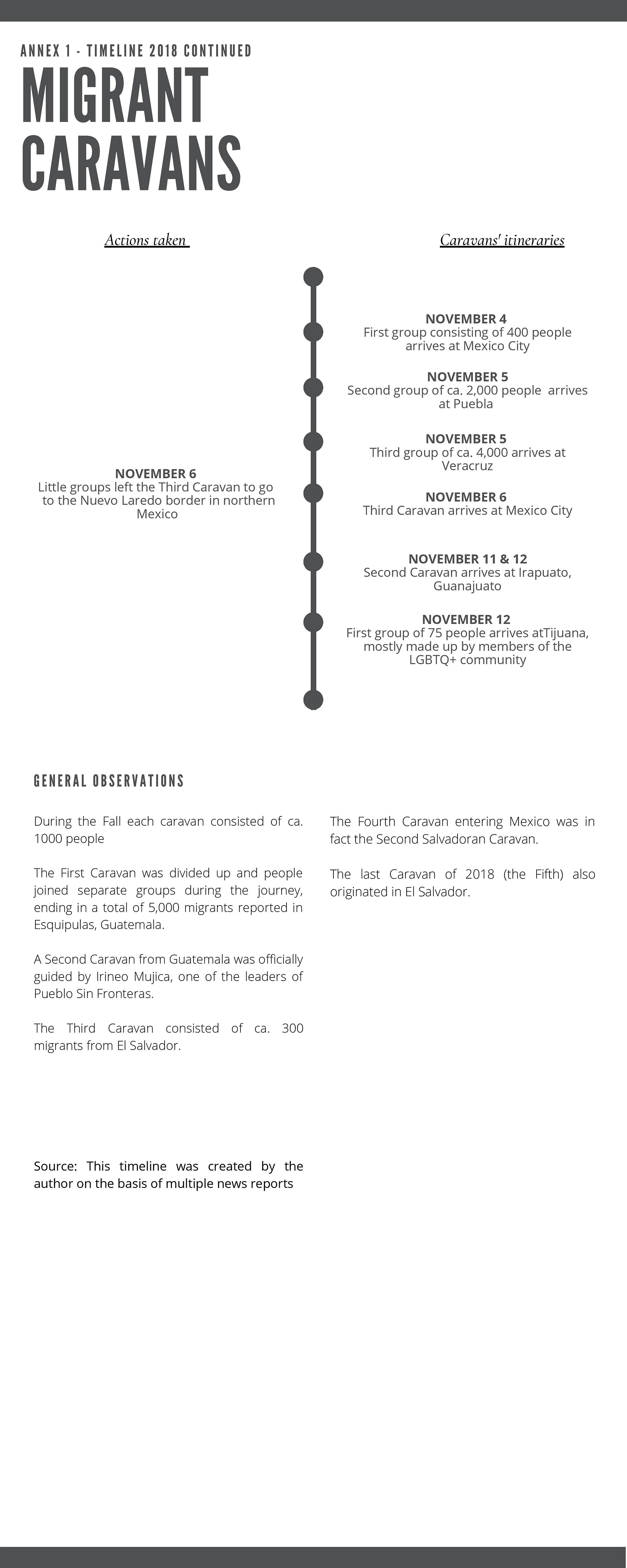

Annexe 1

Annexe 2