Abstract

Taking as a starting point the conviction that everyday interactions carry the potential to be either conflictual or peaceful, this article examines people’s everyday behaviour in the deeply divided city of Kirkuk, Iraq. Using the historic bazaar in Kirkuk city as a site of analysis, and through a research survey of 511 people, it focuses on interactions between Kurds, Arabs and Turkmen. The article draws on Bourdieu’s theory of symbolic capital and takes an intersectional approach to analyse the everyday interactions in the bazaar to create a better understanding of the role of space and privilege. The results demonstrate that for the most part, at the everyday level people carry out acts of everyday peace rather than conflict. However, when everyday conflict does occur, those with the highest symbolic capital are the most likely actors. Additionally, although gender does influence people’s actions, ethnosectarian identity has greater influence in many areas related to everyday peace and conflict. On a practical level, the article argues that such an understanding can connect better to policymaking and peacebuilding as it can point to where and how peacebuilders should focus their attention in order to promote and enhance peace within people’s everyday lives.

Introduction

Peace and conflict do not happen in isolation; rather, in times of peace there are acts of conflict and during times of conflict there are acts of peace, both which often happen at the most mundane level. In examining post-peace accord and stalled peace process societies, Mac Ginty (Citation2006) refers to the continuity between peace and conflict as ‘no war, no peace’. In a deeply divided society not involved in a civil war, peace and conflict are constantly being negotiated without full-blown violence breaking out. In their everyday lives, people in deeply divided societies witness, or carry out, acts of both everyday peace and everyday conflict. This article seeks to understand people’s behaviour, and the dynamics that influence it, in relation to interactions being either conflictual or peaceful in the deeply divided city of Kirkuk, Iraq. It argues that such an understanding allows for academic analysis to connect better with policymaking and peacebuilding, as through understanding the dynamics that lead to either peace or conflict in everyday interactions, interventions can focus on limiting the drivers of conflict and enhancing the drivers of peace.

Everyday conflict refers to practices through which people enact separation in the context of their everyday lives (Fox and Miller-Idriss Citation2008). In a deeply divided society this often involves practices that ‘other’ the rival community and, by extension, damage the process of social cohesion. Closely linked but on the opposite side of the spectrum, everyday peace is concerned with the often-hidden everyday interactions between communities that enact processes of conflict avoidance and/or conflict minimising (Mac Ginty Citation2014). Both constitute forms of agency, and a push and pull between the two is common. On the one hand, everyday conflict inhibits everyday peace through politicising everyday life and making interaction a more fraught process. On the other hand, everyday peace discourages overtly displaying otherness by moving beyond symbols that separate communities.

Kirkuk is a historically multi-ethnic city where conflict has emerged over ownership since the establishment of Iraq. Kurds, Arabs and Turkmen are all competing for positions of power, whilst Assyrians are trying to avoid further political marginalisation. Moreover, with Kirkuk’s significant hydrocarbon reserves and infrastructure to both extract and export oil and gas, there is a substantial financial incentive for control of the province. Consequently, the stakes are high, and Kirkuk has witnessed conflict over its political control (O’Driscoll Citation2018). Nonetheless, the conflict in Kirkuk has received limited academic attention – this is despite its relevance to the wider conflict in Iraq – and the scholarship that does address the subject focuses on top-down and institutional analyses (see Anderson and Stansfield Citation2009; O’Driscoll Citation2018; Romano Citation2007; Wolff Citation2010). The literature on Kirkuk ignores the local turn in the study of peacebuilding,Footnote1 which has been identified as necessary to understand the conditions for peace and to connect with elite-led institutionalised peace initiatives (Mac Ginty and Richmond Citation2013). Moreover, international interventions in Kirkuk, and more generally, tend to focus on top-down and institutional peace and ignore local peacebuilding opportunities (Mac Ginty Citation2010; Mac Ginty and Richmond Citation2013; Paffenholz Citation2015). Liberal peace actors claim to help implement, or at least encourage, peace through their interventions, but the processes they are involved in seldom bring about much change in the everyday lives of people (Björkdahl and Kappler Citation2017; Mac Ginty and Richmond Citation2013). There is often a lack of understanding of how conflict and non-conflict are negotiated on the ground. At the same time, bottom-up peacebuilding is not a panacea for all issues of conflict. Deals between elites are still needed to end conflict. However, bottom-up peacebuilding can improve interactions at the everyday level until such a time as an elite deal is reached (and create pressure on elites to reach a deal) and when a deal is reached it is intrinsic to also address issues that exist at the everyday level. Through creating a better understanding of dynamics that influence interactions and lead to actions of either everyday peace or everyday conflict in Kirkuk, this article aims not only to situate Kirkuk within the local turn in peacebuilding studies, addressing a key gap in the literature, but also to demonstrate opportunities for peacebuilding and policymaking that arise from it.

In order to understand people’s behaviour in relation to acts of everyday peace and everyday conflict, this article utilises Bourdieu’s (Citation2013) theory of symbolic capital, to theorise privilege. It also takes an intersectional approach, as developed by Crenshaw (Citation1989, Citation1991) and Collins (Citation1998), to highlight how layers of privilege impact people’s agency with regards to acts of everyday peace or conflict. The article argues that understanding these dynamics is of importance if interventions are to be specifically targeted to encourage peace within people’s everyday lives.

Within the local turn, there is a growing body of work examining everyday indicators of what peace means to the local population (Firchow Citation2018; Firchow and Mac Ginty Citation2017; Mac Ginty Citation2013). This paper can be seen as complementary to this research stream, but it is also distinctly different, as it looks at behaviour rather than perceptions. An understanding of people’s behaviour in relation to acts of everyday peace and conflict is essential not only to improve interactions, but also to enable interventions to develop policies that limit the drivers of everyday conflict and enhance the drivers of everyday peace. Therefore, this paper examines behaviour, rather than perceptions (where there is already an established body of literature), and although it is seen as a standalone body of research, it can act to complement perceptions-based research from a policy and peacebuilding perspective.

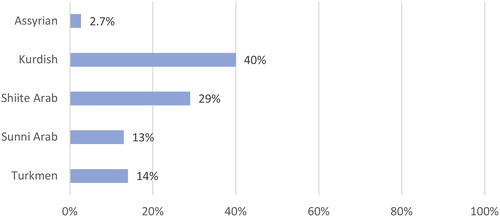

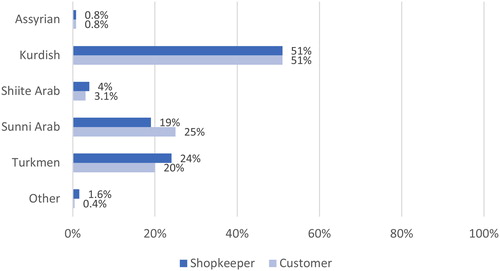

A total of 511 surveys were carried out in the Kirkuk bazaar in early March 2019 for the purposes of this paper. Surveys were carried out using the Mobenzi platform by four local multilingual enumerators (two men and two women) who were hired through the civil society organisation Kokar and who were given full training. Surveys were divided between shopkeepers (n = 253) – in order to understand the role economics plays in interactions – and customers (n = 258). The gender balance in the customer survey was 48.1% women and 51.9% men, whereas (reflecting the fact that there are significantly fewer women shopkeepers) the balance for shopkeepers was 93.7% men and only 6.3% women. The ethnosectarian makeup of both surveys is fairly representative of Kirkuk (see ), based on the election results.Footnote2

Figure 1. Ethnic breakdown of survey participants.Footnote3

Customers were approached as they passed by, whilst shopkeepers were approached on a shop-by-shop basis; as all communities use the bazaar and work or own shops, this method is believed to have prevented selection bias.

The survey format was chosen for its anonymity, since by guaranteeing the participants complete anonymity, in what can be considered a contentious subject in Kirkuk, their answers are more likely to be honest. For this reason, surveys were conducted on a tablet with all three languages (Kurdish, Arabic and Turkmen) available, which the participant was able to use without having to identify their ethnicity to the person carrying out the survey. However, multiple fields of difference – such as ethnosectarian group, income level, gender, education, age and so on – were marked on the survey in order to analyse the findings with regards to the role of gender, ethnosectarian and socio-economic privilege. Survey research was also chosen because it can be useful in understanding the many ways people understand themselves, their social dynamics, and the nature of conflict (Fox and Miller-Idriss Citation2008). Additionally, this article is influenced by observations made by the author through multiple trips to Kirkuk over a 10-year period, which are of importance because through participating in everyday practices one can observe the ongoing work of both conflict and peace on the ground (Wedeen Citation2009).

The next section of this article contextualises ethnosectarian interactions in Kirkuk to better highlight the conflict dynamics and layers of privilege. It then connects the study to the existing literature, before addressing some methodological considerations. This knowledge is then utilised in presenting the results of the study. Finally, the significance of the results and how they can connect to peacebuilding in Kirkuk is argued in the conclusion.

Contextualising ethno(sectarian) interactions in Kirkuk

Kirkuk is home to four main ethnicities – Arabs, Assyrians, Kurds and Turkmen – who all have a historical connection to the city and province dating back hundreds of years. At the time of World War I, Kirkuk was a functioning multiethnic community. However, following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the later creation of Iraq and the installation of the Hashemite monarchy to rule over the country, Arab ascendency began. The Hashemites gave nomadic Arab tribes grants as well as land to farm, whilst Arabs, Assyrians and Armenians were brought to Kirkuk to work in the oil industry. This Arabisation process escalated with the formation of the Republic of Iraq, when Kurds were excluded entirely from the oil industry. At the same time, Kurds were expelled from the region whilst Arabs were enticed with special privileges and bonuses (O’Driscoll Citation2018).

Saddam Hussein increased the Arabisation process by changing Kirkuk’s borders to replace Kurdish-majority rural areas with Arab ones. Additionally, in his Anfal campaign, thousands of Kurds from the Kirkuk region were killed through the use of chemical weapons. Following Operation Desert Storm in 1991, in which the US-led coalition forces expelled Iraqi troops from Kuwait, the Kurds took advantage of the chaos and managed to seize Kirkuk. This victory was, however, short lived, and the Iraqi forces soon regrouped and recaptured it. Despite the loss, Kurds did manage to effectively create an autonomous Kurdish region in the Kurdish provinces of northern Iraq, due to the creation of a no-fly zone by the coalition forces. With the threat this newly created Kurdish region posed to the oil wealth of Kirkuk, Saddam once again increased the Arabisation process in order to maintain his hold over Kirkuk. Through the long process of Arabisation, the numbers of Kurds and Turkmen in Kirkuk drastically decreased, whilst at the same time the number of Arabs increased (Anderson and Stansfield Citation2009).

Since the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, there has been an intensification of the battle between the rival ethnonationalisms for the control of Kirkuk city and province. Turkmen see Kirkuk as a symbol of their position as a significant ethnicity in Iraq. Many Kurds, for their part, see Kirkuk as their ‘Jerusalem’, and there have been calls from some quarters for the city to be made the capital of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) (Hussein Citation2011). At the same time, having Kirkuk under Baghdad’s control is an important part of Iraqi nationalism for many of the Arab population. These varied views and aims demonstrate the large stake that all factions in Kirkuk have in gaining as much control as possible, and for this reason conflict has emerged over the political control of Kirkuk. Furthermore, the Kurdish desire for Kirkuk to join the KRI has caused conflict as the majority of Arabs and Turkmen are against it, for in their opinion it would result in complete Kurdish control of Kirkuk (Agence France-Presse Citation2009). Moreover, the other ethnosectarian groups and neighbouring countries believe the Kurds would use Kirkuk’s hydrocarbon wealth to secede from Iraq (Su’edi Citation2012). The history of Arabisation and the lack of a valid census have made the issue of resolving the political situation in Kirkuk a difficult one, as the presence that each ethnicity claims in Kirkuk can easily be contested. Although a process was developed (Article 58 of the Transitional Administrative Law and Article 140 of the Constitution) to deal with the status of Kirkuk, successive governments have intentionally blocked its implementation.Footnote4 Additionally, the deadline of Article 140 was missed and as a result was extended at the proposal of the United Nations (UN) special envoy to Iraq at the time, Stefan De Mistura, and was approved by the federal supreme court, rather than voted for by the parliament, where it would have clearly failed due to the lack of support from non-Kurds – thus allowing non-Kurds to question the legitimacy of Article 140 (Anderson and Stansfield Citation2009).

Until 2014 the Kurdish Peshmerga and the Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) jointly controlled security in Kirkuk. However, as the Islamic State took control of large swathes of Iraqi territory, the ISF withdrew from Kirkuk to join the battle, in turn allowing the Kurds, and the Peshmerga, to take full control of the city and most of the province (O’Driscoll Citation2018). Once again, this intensified other ethnosectarian groups’ fears that the Kurds were planning to take Kirkuk by force. This fear increased in June 2017 when the president of the KRI, Masoud Barzani (2005–2017), announced a referendum on the KRI’s independence (which included Kirkuk). As a result, the Iraqi Parliament voted to remove the governor of Kirkuk, Najmiddin Karim, a Kurd, who was later replaced by Rakan al-Jabouri, a Sunni Arab, as acting governor. The referendum, held on 25 September, showed overwhelming (just under 93%) support for independence. However, this actually had the result of reducing Kurdish control of Kirkuk. The Iraqi prime minister at the time, Haider al-Abadi (2014–2018), declared the referendum unconstitutional, and the Iraqi Parliament voted to send troops to the disputed territories and impose a host of sanctions against the KRI. In October 2017, Abadi sent in the ISF and the Popular Mobilisation Forces to take control of Kirkuk and other disputed territories, as well as the oil fields within them (O’Driscoll and Baser Citation2019). Due to an agreement with elements of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), most of the PUK-controlled faction of the Peshmerga withdrew to the KRI, and the central government was able to take control of Kirkuk relatively easily, with minimal fighting, before the rest of the Peshmerga in Kirkuk also withdrew to the KRI. As a result, the Kurds’ position in Kirkuk has been significantly weakened since October 2019 (Hasan Hama and Hassan Abdulla Citation2019).

However, the central government’s success did not create a lasting solution to elite-level conflict in Kirkuk, and political battles for control continue. Although the Provincial Council in Kirkuk is made up of members of all groups, the political parties work against each other and often block or prevent political agreements in relation to governance and security in Kirkuk. Even those aligned together in the same political bloc have often failed to work together, such as the failure of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and PUK to agree on the nomination for a candidate for governor. Nonetheless, despite elite competition, Kirkukis carry on their lives with both conflict and, more importantly, peace emerging daily, and it is these everyday interactions in which this article is most interested.

Everyday peace and conflict and the impact of privilege

This section covers the literature that informed the design of the survey and the analysis of the results; it includes literature on everyday peace and conflict, symbolic capital and theories of intersectionality.

There are no rules for everyday peace and conflict; rather, they are driven by context, space, time and individuals. Everyday peace operates within the boundaries of the social contract, as conflict is avoided through sensitive perception, avoidance (both physical and of contentious topics) and concealment (Mac Ginty Citation2014). Mac Ginty (Citation2014, 556) highlights five types of everyday peace: avoidance, ambiguity, ritualised politeness, telling and blame deferring. In the context of the Kirkuk bazaar, this can be actualised by using the native language of the person you talk to; going to shops of people of the same ethnicity; avoiding contentious topics; avoiding highlighting what part of Kirkuk you are from (or asking where the other person is from); not displaying/wearing items or other signifiers that link to your ethnosectarian group; ‘not seeing’ acts of everyday conflict; exhibiting reserved politeness; blaming conflict on minorities within your own group; and so on.

Everyday conflict crosses these socially constructed boundaries and overtly displays otherness and, within the context of a deeply divided society, forms of it can antagonise the out-group (Knott Citation2015). Through the lens of nationalism, Fox and Miller-Idriss (Citation2008, 537–538) put forward four ways in which this othering can be (re)produced within the everyday: talking the nation, choosing the nation, performing the nation and consuming the nation. In the context of the Kirkuk bazaar, this can be performed through the clothes worn; flags, badges, murals or images; insisting on speaking your own language; talking about your nation and about linked, contentious subjects; asking probing questions; and so on. Key here are processes that other based on ethnosectarian identity.

Additionally, everyday consumption habits also become a site in which everyday conflict and everyday peace are enacted. Although avoiding shops owned by members of the other ethno(sectarian) groups can be a process of everyday peace or conflict avoidance, the reasoning behind the action also needs to be taken into account. Only going to shops of people from the same ethnic group can be part of what Fox and Miller-Idriss (Citation2008, 542) label ‘choosing the nation’ if the objective is to support, and interact only with, those from your ethno(sectarian) group. Public spaces can also take on meaning through the everyday consumption practices of their clientele. Cafés, teahouses, kebab shops and social clubs can become exclusive hangouts, and crossing of this boundary by an out-group member can be considered a form of aggression. However, beyond these dynamics, privilege plays an important role in influencing people’s behaviour.

Even in a place such as the bazaar, which is open to all and where interaction is encouraged, structural inequalities persist and are reproduced, which in turn impacts on people’s agency to carry out acts of everyday conflict and everyday peace. In understanding people’s behaviour, the way structural power relations are reinforced, and at times resisted, is important. However, it is important here to acknowledge that people’s agency is not erased, albeit it might be constrained through structural inequalities. Even in the most deeply divided societies people do have a fair amount of autonomy in their actions (Selimovic Citation2019). Nonetheless, wider structural inequalities, power relations and hierarchies influence people’s decisions about their actions, as the repercussions of acts of everyday conflict are greater for some than for others. In the context of actions of everyday conflict, those with more privilege in society are more empowered than others, making it easier for them to carry out these actions, whilst for those who are disempowered it may be a necessity for them to carry out actions of everyday peace. As argued by Björkdahl and Kappler (Citation2017, 17), agency is not uniform and is marked by ‘ethnic, class or gender differences’, and thus ‘such dimensions of agency need to be brought to the fore since they drive marginalisation and oppression in post-conflict societies’. Thus, privilege, and the symbolic power that goes with it, can make it more likely for someone to carry out un/conscious actions that are seen here as acts of everyday conflict.

Bourdieu’s (Citation1989) theorisations on symbolic capital allow for an understanding of the way privilege can influence interactions. Symbolic capital refers to the conversion of the other forms of capital (economic, cultural and social) to the most recognised and legitimate form. In short, it refers to the form of capital, ’or accumulation of capitals,’ that transfers to the highest privilege in the situation. As argued by Bourdieu (Citation2013), space is important when looking at cultural or symbolic injustice of privilege. For this reason, it is important to examine behaviour in relation to everyday peace and everyday conflict in a physical space, such as the bazaar, where interaction happens between people who are often from different social spaces and would not interact otherwise. The way space is occupied means that some groups of people experience a stronger sense of entitlement to it than others, who are as a result treated as inferior in these spaces. This process of undermining their legitimacy can be considered an act of symbolic violence. In conflict settings this has a greater impact, as the subtle actions and domination of space that connect to privilege can be seen as acts of everyday conflict or domination of one group over others.

In Kirkuk, as in many other deeply divided societies, privilege is linked to ethnosectarian identity, as Kurds are privileged over others in how they can act within social spaces. Since 2003, Kurds have taken control of key positions within the local government and, more importantly, have a monopoly over security provision. Therefore, Kurds in Kirkuk, through social capital connected to being Kurdish, are privileged over other ethnic groups, and this is reflected in the way in which they use social space, as highlighted in the analysis section of this paper. The security element is an important factor, as Kurds received preferential treatment due to their dominance of the sector, particularly when compared with Sunni Arabs. Social capital is particularly relevant in the regional context where wastaFootnote5 plays a significant role in daily life. However, as already highlighted, the dynamics of Kurdish control did change in October 2017, which has lessened Kurdish privilege, and another aim of the survey is to highlight the extent to which that happened.

At the same time, due to the lasting impact of the Ottoman Empire, historically, Turkmen are privileged with regards to land and business ownership and civil service employment – making them the economic capital-owning class. Ethnicity thus delineates symbolic capital and, in the case of Kirkuk, social capital (of which the Kurds have arguably the most) is a marker stronger than economic capital (of which Turkmen have more) (Bourdieu Citation2008). Correspondingly, linguistic capital is not connected to education and class, as in Bourdieu’s (Citation1991) original analysis, but rather native or non-native proficiency in the language with the highest social capital in the circumstances – for instance, being considered a native Kurd. Although the conversion from capital/s to symbolic capital is case-specific, I would argue that in deeply divided societies, due to the role that ethno(sectarian) identity plays, social capital is more likely to convert to symbolic capital, as no matter how much economic or cultural capital a person has it will not lead to them to becoming a member of the dominant ethno(sectarian) group.

Therefore, in order to understand how privilege, or a lack thereof, influences behaviour it is important to include the role of symbolic capital in the analysis. In a deeply divided society such as Kirkuk, conflict is commonplace, yet not all actors are equally likely to engage in everyday conflict to the same extent, and symbolic capital offers a useful tool to understand the existing variations. This poses a number of questions, such as what role symbolic capital plays in everyday conflict and peace and how the limited symbolic capital of Arabs, particularly Sunnis, affects their agency in the process of everyday peace and conflict, both of which will be addressed later.

It is crucial to note here that although this paper argues that Bourdieu’s theory of capitals should be utilised to better understand agency in relation to everyday peace and conflict, the focus is on privilege connected to ethnicity/sect and not on economic class; thus, the concept of symbolic capital becomes central. This is key because, whilst using elements of Bourdieu’s work to theorise social hierarchies and privilege, this article also acknowledges the limits of his theorisations of class that do not translate easily and meaningfully onto the socio-economic context of deeply divided societies. That said, ethno(sectarian) groups are not homogeneous, and although ethnicity/sect can link directly to symbolic capital, other factors – such as gender, tribe, age, ability and so on – come into play, leading to a hierarchal distribution of capital also within each group. Additionally, it is within a group hierarchy that cultural capital is negotiated, making culture a site of struggle for privilege, as those with demonstrably higher cultural capital are treated differently within each ethnic group (Skeggs Citation2004). Thus, an intersectional approach must be applied to understand how ethnicity, sect, gender, tribe and so on impact on the individual’s symbolic capital and the hierarchy this creates within an already hierarchical ethnic division of capital, and the way these overlap (Anthias Citation2005, 45). Consequently, an intersectional approach addresses the critique that the everyday analysis of ‘ordinary people’ considers these people to be ‘undifferentiated’ and overlooks hierarchies within groups (Smith Citation2008).

Intersectional analysis was developed from the work of Spelman (Citation1988) and black feminists in the US, such as Crenshaw (Citation1989, Citation1991) and Collins (Citation1998). It originates from the need to understand how complex inequalities influence power relations with an early focus on what it means to be both a woman and a person of colour. It has since grown as an analytical tool to examine a number of complex inequalities and the influence these have on power relations. Feminist peace and conflict scholars see intersectionality as central, as they aim to analyse ‘gender, sexuality, race, and class relations as power structures within any given empirical setting’ in order to understand marginalised people’s accounts of alternatives to violence (Wibben et al. Citation2019, 87, 89). Due to the important role that privilege and inequality play in people’s agency in deeply divided societies, I would argue that an intersectional lens should be standard practice for all peace and conflict scholars, not just those who identify as feminist peace and conflict scholars.

An intersectional analysis is extremely important for this study, as in Kirkuk there are a number of axes, or fields – given the experiences of any given characteristic are not uniform – of difference, beyond the ethnosectarian group, that need to be taken into account to understand who is likely to engage in actions of everyday peace and who is likely to engage in actions of everyday conflict, or both, and to what degree. For example, the analysis of the interaction between everyday conflict and peace in Kirkuk needs to take into consideration that an unmarried, younger, Arab woman is unlikely to occupy space and engage with everyday practices in the same way as a married, middle-aged, Arab man – let alone a Kurdish (seen to have the highest symbolic capital), middle-aged man with strong political links.

The example above demonstrates the importance that gender can play within the hierarchical division of capital. It also points to the need for intersectional analysis of the local. This is further discussed by Sadiqi and Ennaji (Citation2006, 88) in the context of Morocco, where they argue that ‘women can be in some public spaces – for example, on the street – but cannot stay there as men are encouraged to. Rather, women must do their business and move on’. They go on to argue that ‘although the public space has been unliberating for the poorer sections of women, it has empowered the socially privileged’, reinforcing the existing hierarchies (Sadiqi and Ennaji Citation2006, 95). However, as already highlighted, in a deeply divided society, ethnosectarian identity is a marker that carries more weight than economic capital, although class still exists within each group. Nonetheless, multiple layers of negative capital and symbolic violence can also lead to the invisibilisation of the individual as they are not recognised as legitimate (McKenzie Citation2015). This puts forward a number of further questions that need to be posed, such as: Is the capital of Kurdish women high enough to privilege them over both men and women of other groups, or does it constrain their agency in the processes of everyday conflict? How do the multiple fields of difference that create people’s intersectional identities impact upon the way in which they interact and are treated by others? And, finally, how do those with the lowest capital (Sunni Arab women) negotiate this? Whilst in such an analysis, people’s agency in undertaking acts of everyday conflict still has to be taken into account, it is acknowledged that limited symbolic capital may influence an individual to enact some elements of everyday peace or conflict avoidance, as the repercussions of conflict are likely to be higher for individuals who occupy lower recognition within the society.

The everyday and the bazaar as the site of analysis

Feminist scholars have long pointed to how the mundane and everyday are sites that are political and thus deserving of analytical attention. This article uses the everyday as a methodological entry point to examine people’s behaviour in relation to peace and conflict in the deeply divided society of Kirkuk. For Enloe (Citation2011, 447) the everyday is a useful analytical site, as power is deeply at work where it is least apparent and thus ‘the kinds of power … created and wielded – and legitimized – in these seemingly “private” sites … [are] causally connected to the forms of power created, wielded and legitimized in the national and inter-state public spheres’. Similarly Dyck (Citation2005, 234) also connects the everyday to power and believes that

taking a route through the routine, taken-for-granted activity of everyday life in homes, neighbourhoods and communities can tell us much about its role in supporting social, cultural and economic shifts – as well as helping us see how the ‘local’ is structured by wider processes and relations of power.

Therefore, the everyday is useful to understand power (im)balances, which is particularly important in deeply divided societies, and in order to analyse these (im)balances better, Bourdieu’s theory of symbolic capital and theories of intersectionality are utilised.

Davies and Niemann (Citation2002) argue that the recognition that there is a contradiction between hegemonic claims about life by elites and the actual reality of everyday life can lead to transformation within society. For them it is important to examine how international relations are produced in people’s everyday lives rather than there being a predominant focus on elites. Thus, the everyday can be used as a lens to demystify the conflict in order to understand the difference between the appearance (which is gauged through a distant focus on political elites) and the reality of lived experiences. The everyday is also a site of individual habits as well as localised and individualised forms of resistance, and it is the connection between these two that is highly relevant for understanding behaviour in relation to acts of everyday peace and everyday conflict (Elias and Roberts (Citation2016, 788).

Moving on to understandings of the everyday in peace and conflict studies, for Mac Ginty (Citation2014, 550), ‘the everyday is regarded as the normal habitus for individuals and groups, even if what passed as “normal” in a conflict-affected society would be abnormal elsewhere’. Whereas, for Jones and Merriman (Citation2009, 166), ‘in addition to being a place of banal and mundane processes’, the everyday ‘may also incorporate a variety of hotter “differences and conflicts” that affect people’s lives on a habitual basis’. For this article, the everyday is seen as the mundane and trivial practices of everyday life where acts of localised or individualised resistance or compliance are carried out, where actors routinely carry out small acts of symbolic aggression or sometimes demonstrate extraordinary malleability in avoiding aggression. All of these are influenced by power imbalances reflecting the local political order, thus making the everyday a useful lens through which to examine the drivers of both peace and conflict and to demystify the conflict in order to understand the difference between that portrayed at the elite level and the reality on the ground.

When examining the everyday with the aim of understanding the dynamics that influence people’s interactions in deeply divided societies, the choice of space becomes important, as space itself impacts behaviour. As Gusic (Citation2019, 49) states, ‘society is fundamentally spatial in the sense that everyday life, protests, violence, war, and peace all play out in space … therefore that what exists in space will affect how society plays out’. In deeply divided societies, identities often merge with territory to create exclusive spaces through acts of everyday conflict, and such spaces would not be suitable to understand interactions, as ‘space is shaped by social interactions and at the same time it shapes these interactions’ (Björkdahl and Buckley-Zistel Citation2016, 3). Thus, space has a direct impact on the way in which everyday peace and everyday conflict can be negotiated, making the choice of site for analysis extremely important. It needs to be sufficiently ‘neutral’ so that the existing power structures within society are represented and so that the space is not misrepresentative by favouring one group (outside of the power structures that already exist within the society) and thus giving a skewed picture of the realities of the society. However, it is important that the neutrality refers to spaces open to all, rather than so-called ‘peace spaces’ where peacebuilding is encouraged, as these spaces do not mirror the power structures within the society (Lepp Citation2018; Vogel Citation2018).

For the above reasons, the historic old bazaar beneath the ancient citadel in Kirkuk has been chosen as a site through which to examine this interaction, as this is a traditional place of meeting in Kirkuk. Given its large number of shops, variety of goods and relatively low prices, it attracts a large percentage of Kirkuk’s population. Additionally, in bazaars, social, political and spatial hierarchies can be observed, as different social classes and ethnosectarian groups interact. Bazaars are more than just places of economic exchange; they are also ‘centers of civic participation where diverse social, economic, ethnic, and cultural groups combine, collide, cooperate, collude, compete, and clash’ (Bestor Citation2001, 9227). Moreover, communication is enhanced through practices such as haggling; the lack of price tags and the fact that the buyer wants the lowest possible price whilst the seller wants the highest possible price mean that interaction is increased. The unknown element of both quality and price means that buyers either go in search of information, increasing the level of interaction and the time spent in the bazaar, or they form established relationships with selected stallholders whom they constantly return to. The fact that trades are usually ethnically specialised and that they are also spatially located encourages ethnic interaction between the sellers and the buyers (Geertz Citation1978). Additionally, the urban space and the market architecture itself influences human behaviour, and the chaotic nature of the bazaar can create a dimension with its own peculiar rules and regulations (Foucault and Miskowiec Citation1986).

Everyday peace and conflict in Kirkuk

This section utilises the survey data to understand the impact of everyday peace and everyday conflict in the bazaar in Kirkuk and the impact that privilege has on such behaviour.

Privilege

Privilege, and local understandings thereof, is important to understand in order to analyse behaviour in relation to acts of everyday peace and conflict. The survey results suggest that despite the decrease in Kurds’ power in Kirkuk since October 2017, Kurds are still seen by all communities to have the most overall influence in the society (see ). Assyrians, with their low numbers, are seen to have the least influence, followed by Sunni Arabs. Arab Shiites are seen to have relatively high influence; however, this can be seen to be closely connected to the security changes since October 2017.

The fact that the majority of those who responded to the survey were Kurdish (51%) also has to be taken into account, as people are less likely to acknowledge their own privilege. Although Kurdish influence is less than it would have been prior to October 2017, the structural legacies still remain. A couple of other factors are relevant here; firstly, the Kurds have the ability to select a new governor due to their numerical advantage in the provincial council, which they have yet to do due to internal competition between the two main Kurdish parties. The governor of Kirkuk has considerable power and is thus able to (and generally does) further privilege their own group. Thus, there is an expectation from the population that a new Kurdish governor could be chosen at any time. Secondly, there are constant rumours in Kirkuk and Iraq that deals will be/have been made for the return of the Peshmerga, which would further privilege the Kurds. These factors are important, as past behaviour influences the current behaviour of groups, but – most importantly – so do perceptions of the future (Read and Mac Ginty Citation2017). Thus, the expectations surrounding these two events influence people’s behaviour and impact on privilege. Therefore, if the survey had been conducted prior to October 2017, or if any of the changes mentioned above were to be implemented, it is likely that Kurdish privilege would be higher and so, in turn, could the number of acts of everyday conflict by Kurds. At the same time, the more time passes without these changes being implemented, the more likely it is that Kurdish privilege will decrease.

Privilege, conflict avoidance and space

The understanding of such privilege is important as it impacts on how people occupy space and carry out acts of both everyday peace and everyday conflict, as some people face fewer repercussions than others for their actions due to their symbolic capital. At the same time, those with less privilege are more likely to witness acts of symbolic violence and are less likely to report the same. Consequently, the survey results show that Kurds are the least likely to avoid topics that may cause conflict, with 60% highlighting that they avoid topics that may cause conflict, in comparison to 72% of Sunni Arabs and 75% of Turkmen. Additionally, Kurds are the most likely to discuss the contentious subject of the political situation in the city (21%) with members of other groups, in comparison to only 6.3% of Sunni Arabs and 9.6% of Turkmen. Highlighting the gendered aspect of privilege, 77% of women avoid topics that may cause conflict, in comparison to 56% of men. Privilege also impacts on how free people feel in the bazaar, with Kurdish customers feeling freer to carry out a number of actions than either Sunni Arabs or Turkmen. In particular, 44% feel free to relax and socialise in the bazaar in comparison to 28% of Sunni Arabs and 35% of Turkmen. What this demonstrates is that the elite power dynamics are reproduced at the local level and have a significant impact on behaviour even within the everyday; Kurds are the most comfortable in how they occupy space, which directly connects to privilege.

Responding to insults

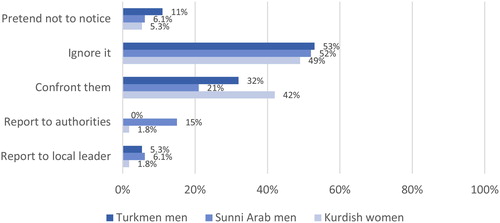

The reaction to insults is a good indicator to examine the impact of privilege, as it can identify whether people carry out acts of everyday peace (by avoiding conflict), or acts of everyday conflict (by confronting it). Kurds are the most likely (41%) to confront someone from another group who insults them in the bazaar and the least likely to carry out acts of conflict avoidance by either pretending they did not see/hear the insult or ignoring it (54%). Sunni Arabs are the most likely to carry out acts of conflict avoidance (69%) and the least likely to confront those who insult them (20%). This is closely followed by Turkmen, with 65% carrying out acts of conflict avoidance.

Sunni Arab women are the most likely group to carry out acts of conflict avoidance (81%) and the least likely to confront the person insulting them (19%). This is a significant difference in comparison to Kurdish women, with 54% signalling that they would carry out acts of conflict avoidance and 42% signalling that they would confront the person. From the intersectional perspective of relating ethnosectarian identity and gender to privilege, Kurdish women were less likely (54%) to carry out acts of conflict avoidance than both Sunni Arab men (58%) and Turkmen men (63%). Kurdish women are also more likely (42%) to confront the person than both Sunni Arab men (21%) and Turkmen men (32%) (see ). This demonstrates how in Kirkuk structural power dynamics directly impact actions of peace and conflict at the everyday level. Therefore, concerning privilege in relation to direct confrontations, ethnosectarian identity is more influential than gender.

Wearing and celebrating privilege

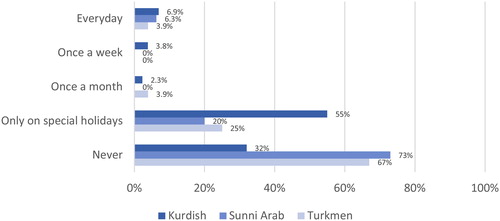

Wearing ethnosectarian identity signifiers in public can be perceived by some as an act of everyday conflict, as the person is ‘performing the nation’ through overtly displaying otherness (Fox and Miller-Idriss Citation2008). This can lead to antagonising relations with members of other groups. This is not to say that people should not wear identity signifiers, as it comes down more to understanding what these may mean, or to a more complex accumulation of factors including group behaviour. Signifiers by themselves are less likely to lead to conflict, but when they are paired with other divisive behaviour the accumulation of factors can lead to others feeling under threat. Although daily use is limited, there is an increase around special holidays, and again Kurds are the most likely to wear identity signifiers, with 55% wearing them on special holidays (see ).

Figure 4. Kurdish, Sunni Arab and Turkmen customers’ regularity in wearing items that identify their ethnosectarian group.

Generally, women are less likely than men to wear items that identify their ethnosectarian identity, with 73% of Turkmen women and 84% of Sunni Arab women never wearing identity signifiers, in comparison to 58% of Turkmen men and 64% of Sunni Arab men. However, Kurdish women are the most likely group across the whole society to wear identity signifiers, with only 28% never wearing them and 63% wearing them on special holidays.

Kirkukis’ perceptions of when tensions arise are closely connected to identity signifiers, as many highlight occasions when people are more likely to wear identity signifiers, such as the Kurdish holiday of Nawroz,Footnote6 Kurdish Clothes Day, elections, or anniversaries of historical events, as marked by increased tensions. It is important to note that it is not the identity signifiers alone, or the occasions alone, but rather the nexus of factors that increase the level of acts of everyday conflict from one community that is viewed as threatening and/or antagonistic by other communities. There is minimal difference between the perceptions of tensions between groups. However, shopkeepers tend to notice tensions more than customers, which could be linked to them being in the middle of the city all day.

How people celebrate holidays can also be connected to identity markers and tensions, as celebrating them in public becomes part of the nexus that leads to heightened perceptions of dominance by one group over another. Kurds are the most likely to celebrate holidays such as Eid or Nawroz (which is traditionally celebrated outdoors) in public (58%), whereas Turkmen are the most likely to celebrate holidays at home (71%). Kurdish use of public spaces to celebrate is more connected to privilege in how they can, and feel they can, occupy space. As tensions are said to increase during special holidays, such as Nawroz, and Kurds are more likely to wear identity signifiers and celebrate in public, all these factors are connected to how conflict between communities plays out at the local everyday level and how it increases at specific times. Nonetheless, as part of an inclusive multicultural society, it is important that the cultures and traditions of all groups are respected. However, at the same time, there is currently the perception that the culture of one group (Kurds) dominates public space, which is possible due to their privilege, and this in turn creates tension at the everyday level.

Gendered use of the space

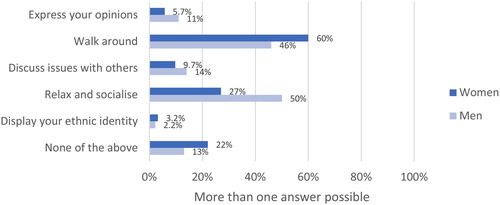

Although ethnosectarian identity and the amount of symbolic capital connected to it can influence actions, it is important to acknowledge the gendered aspects of utilising the bazaar. Although women feel freer than men to walk around the bazaar, this comes down to how space is occupied, as it is normal for women to go to the bazaar for the set purpose of shopping. More telling is that only 27% of women feel free to relax and socialise in the bazaar, in comparison to 50% of men (see ). This connects directly to gender equality, as women do not have the same privileges as men in how they can occupy the space. Sadiqi and Ennaji (Citation2006) argue that in many spaces such as the bazaar, women are expected to go about their business and then leave, whilst men do not need a purpose and can hang around such spaces. As the majority of Iraqi women do not work (circa 87% in 2020),Footnote7 having spaces to relax and socialise outside of the home is extremely important.

Figure 5. Female and male customers’ freedom of actions. Note: It was possible for respondents to select more than one answer.

Additionally, both women (60%) and men (56%) customers agree that women are not treated equally in the bazaar. However, 71% of Sunni Arab women feel that women are not treated equally, which correlates with the other survey questions that point to them being the most marginalised group. The difference between the groups in terms of feeling safe in the bazaar is not huge; however, this changes with gender, with 19% of men often feeling unsafe or never feeling safe at all, in comparison to 39% of women. Therefore, gender equality, women’s socialising in the bazaar, and women’s safety are all interconnected issues relating to how women can utilise, and feel comfortable utilising, the space in the bazaar. However, as has been highlighted, factors such as ethnosectarian identity still come into play in how different women can occupy space, which is important knowledge for policymaking.

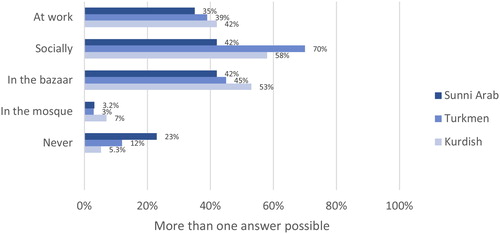

Interacting with other groups

There is minimal difference between men and women in the level of social interaction with other ethnosectarian groups; however, 11% of women never interact with members of other ethnosectarian groups, in comparison to 3% of men. This may be connected to the fact that women are less likely to interact with other group members in the mosque and at work. Sunni Arab women are the least likely group to interact with other groups socially, with only 42% doing so, in comparison to 58% of Kurdish women and 70% of Turkmen women (see ). Additionally, 23% of Sunni Arab women never socialise with members of other groups, as opposed to 5.3% of Kurdish women and 12% of Turkmen women. This connects to the wider Sunni Arab isolation in Kirkuk, which is an important issue that needs to be addressed to enhance localised peacebuilding. However, as Sunni Arabs are less multilingual than Kurds and Turkmen, some of this isolation is also connected to their limited knowledge of the others’ languages, which again has historic connections to the Saddam era. Again, this is an issue that can be tackled through policymaking.

Figure 6. Sunni Arab, Kurdish and Turkmen women customers’ interactions with members of other groups. Note: It was possible for respondents to select more than one answer.

Although this section has demonstrated that privilege influences how people act in the bazaar, it is important to note that conflict avoidance is the action of the majority of people, demonstrating that everyday peace is more common than everyday conflict. Moreover, when customers were asked the leading factors that they considered when choosing shops, quality and price were most common and ethnosectarian group hardly featured, with only 1.9% of people taking the latter into consideration. At the same time, although more pronounced, ethnosectarian identity is also a limited factor for shopkeepers when negotiating price, with 12% of shopkeepers taking this into consideration, and how well they know the customer was the leading factor in negotiations.

Conclusion

The findings in this article directly connect privilege to the increase in acts of everyday conflict. However, although because of their privilege Kurds are more likely to engage in acts of everyday conflict, and because of their lack of privilege Turkmen and Sunni Arabs are more likely to engage in acts of everyday peace, for the most part people (including Kurds) seek to avoid conflict and go about their daily lives. This highlights the opportunity for peacebuilders in Kirkuk to focus on bottom-up peacebuilding whilst political stalemate persists. This could in turn build pressure from below for agreements above, as both are necessary for peace. However, although conflict avoidance dominates at the everyday level, conflict does emerge, and privilege plays a significant role in this. Thus, this article demonstrates that symbolic capital is a useful lens through which to examine how privilege can impact on both behaviour and agency in deeply divided societies. However, as groups are not homogeneous, it is important that this analysis goes one step further, and therefore an intersectional lens is also suggested in order to understand how the various fields of difference impact on behaviour within, and across, each group.

Additionally, an examination of the everyday demonstrates how privilege connects to the past and the future, and although Kurds lost significant power in Kirkuk in October 2017, they are still the most privileged group in practice. This may be a surprising finding for many who only base their understanding of the local dynamic on current institutional divisions of power; this therefore demonstrates the benefit of a bottom-up analysis. From a policy perspective this is of value, as power dynamics are important on the ground. Moreover, as privilege, and the lack thereof, connects to practices of everyday conflict and peace, such an understanding can help build the drivers of peace and limit the drivers of conflict, and thus improve localised peacebuilding. For instance, this research demonstrates the need to address certain holidays being seen as flashpoints, which can be done through cultural education in schools, training community leaders on the importance of inclusive cultural experiences, providing spaces outside of the city centre to celebrate such occasions, and so on. It also demonstrates the value of the bazaar as a space of interaction and how it can be utilised to create relationships across community lines and so on.Footnote8 There are a number of international organisations that work on peacebuilding in Iraq (or closely connected development issues), and through evidence-based programming that focuses on understanding the dynamics through which everyday peace and everyday conflict emerge, interventions can be better placed to focus on specific areas that can encourage peace at the everyday level. At the same time, there are local organisations working to improve relations between communities; however, their programming often mirrors that of the international organisations that fund them, thus a shift to focus on behaviour would also benefit them.

In summary, this paper has demonstrated that through developing an understanding of when and why acts of everyday conflict may emerge, and who is likely to instigate them, interventions can focus on preventing conflict in a more targeted and locally sensitive way. At the same time, an understanding of when and why acts of everyday peace emerge, and who is likely to engage in them, can help interventions to build on these existing dynamics.

Acknowledgements

This article builds on the author’s earlier SIPRI policy paper ‘Building Everyday Peace in Kirkuk, Iraq: The Potential of Locally Focused Interventions’. The author thanks Dr Birte Vogel, Dr Magdalena Mikulak, Khogir Wirya, and Shivan Fazil for their feedback, as well as Kokar for their assistance in conducting the survey. All errors remain the author’s responsibility alone.

Funding

This research is a publication of the Conflict Research Programme hosted at the London School of Economics. This material was funded by UK aid from the UK government through the Conflict Research Fellowship, managed by the Social Science Research Council; however, the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s views and/or official policies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Dylan O’Driscoll

Dylan O’Driscoll is Senior Researcher and Director of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) Programme at the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI).

Notes

1 With the exception of O’Flynn et al. (Citation2019), who examine deliberation between university students in Kirkuk.

2 The ethnosectarian makeup of Kirkuk is largely contested, and as a census has been blocked for political reasons relating to Article 140, it is difficult to discuss the numbers with any certainty.

3 Percentages in all figures may not add up to or may exceed 100% due to rounding.

4 Article 58 of the Transitional Administrative Law (TAL) called for the normalisation of the disputed territories of Iraq, followed by a census and then a referendum on the future constitutional status (in Kirkuk’s case, whether it would join the KRI or not). Article 140 of the Iraqi Constitution called for the implementation of Article 58 of the TAL by 31 December 2007.

5 Wasta refers to using family or social connections to achieve your objective.

6 Nawroz marks the arrival of spring. Although a number of groups in Asia celebrate Nawroz, it is the most important Kurdish holiday and has also taken on political significance as it has become a symbol of Kurdish resistance to oppression.

7 According to World Bank data from 2020, only 12.4% of the population of women ages 15–64 participate in the labour force. See https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.ACTI.FE.ZS?locations=IQ

8 For a more detailed example of how the understandings developed through this research can be transformed into policymaking, see O’Driscoll (Citation2019).

Bibliography

- Agence France-Presse. 2009. “Turkmen join Arabs to stop Referendum in Kirkuk.” Hurriyet. August 17. http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/default.aspx?pageid=438&n=turkmen-join-arabs-to-stop-referendum-in-kirkuk-2009-08-17

- Anderson, L., and G. Stansfield. 2009. Crisis in Kirkuk: The Ethnopolitics of Conflict and Compromise. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Anthias, F. 2005. “Social Stratification and Social Inequality: Models of Intersectionality and Identity.” In Rethinking Class: Culture, Identities and Lifestyle, edited by F. Devine, M. Savage, J. Scott, and R. Crompton, 24–45. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bestor, T. C. 2001. “Markets: Anthropological Aspects.” International Encyclopedia of Social and Behavioral Sciences: 9227–9231. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-08-043076-7/00907-4

- Björkdahl, A., and S. Buckley-Zistel, eds. 2016. Spatialising Peace and Conflict: Mapping the Production of Places, Sites and Scales of Violence. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Björkdahl, A., and S. Kappler. 2017. Peacebuilding and Spatial Transformation: Peace, Space and Place. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Bourdieu, P. 1989. “Social Space and Symbolic Power.” Sociological Theory 7 (1): 14–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/202060.

- Bourdieu, P. 1991. Language and Symbolic Power. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. 2008. “The Forms of Capital.” In Readings in Economic Sociology, edited by N. W. Biggart, 280–291. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Inc.

- Bourdieu, P. 2013. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. New ed. London: Routledge.

- Collins, P. H. 1998. “It’s All in the Family: Intersections of Gender, Race, and Nation.” Hypatia 13 (3): 62–82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.1998.tb01370.x.

- Crenshaw, K. 1989. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” The University of Chicago Legal Forum 140: 139–167.

- Crenshaw, K. 1991. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review 43 (6): 1241–1299. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039.

- Davies, M., and M. Niemann. 2002. “The Everyday Spaces of Global Politics: Work, Leisure, Family.” New Political Science 24 (4): 557–577. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0739314022000025390.

- Dyck, I. 2005. “Feminist Geography, the ‘Everyday’, and Local–Global Relations: hidden Spaces of Place-Making*.” Canadian Geographer / Le Géographe Canadien 49 (3): 233–243. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0008-3658.2005.00092.x.

- Elias, J., and A. Roberts. 2016. “Feminist Global Political Economies of the Everyday: From Bananas to Bingo.” Globalizations 13 (6): 787–800. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2016.1155797.

- Enloe, C. 2011. “The Mundane Matters.” International Political Sociology 5 (4): 447–450. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-5687.2011.00145_2.x.

- Firchow, P. 2018. Reclaiming Everyday Peace: Local Voices in Measurement and Evaluation after War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Firchow, P., and R. Mac Ginty. 2017. “Measuring Peace: Comparability, Commensurability, and Complementarity Using Bottom-Up Indicators.” International Studies Review 19 (1): 6–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/isr/vix001.

- Foucault, M., and J. Miskowiec. 1986. “Of Other Spaces.” Diacritics 16 (1): 22–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/464648.

- Fox, J. E., and C. Miller-Idriss. 2008. “Everyday Nationhood.” Ethnicities 8 (4): 536–563. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796808088925.

- Geertz, C. 1978. “The Bazaar Economy: Information and Search in Peasant Marketing.” The American Economic Review 68 (2): 28–32.

- Gusic, I. 2019. “The Relational Spatiality of the Postwar Condition: A Study of the City of Mitrovica.” Political Geography 71: 47–55. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2019.02.009.

- Hasan Hama, H., and F. Hassan Abdulla. 2019. “Kurdistan’s Referendum: The Withdrawal of the Kurdish Forces in Kirkuk.” Asian Affairs 50 (3): 364–383. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03068374.2019.1636522.

- Hussein, A. 2011. “MPs collecting signatures to question Talabani.” Iraqi News. March 12. http://www.iraqinews.com/baghdad-politics/mps-collecting-signatures-to-question-talabani/

- Jones, R., and P. Merriman. 2009. “Hot, Banal and Everyday Nationalism: Bilingual Road Signs in Wales.” Political Geography 28 (3): 164–173. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2009.03.002.

- Knott, E. 2015. “Everyday Nationalism: A Review of the Literature.” Studies on National Movements 3: 1–16.

- Lepp, E. 2018. “Division on Ice: Shared Space and Civility in Belfast.” Journal of Peacebuilding & Development 13 (1): 32–45. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15423166.2018.1427135.

- Mac Ginty, R. 2006. No War, No Peace: The Rejuvenation of Stalled Peace Processes and Peace Accords. Baskingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mac Ginty, R. 2010. “Hybrid Peace: The Interaction between Top-Down and Bottom-Up Peace.” Security Dialogue 41 (4): 391–412. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010610374312.

- Mac Ginty, R. 2013. “Indicators+: A Proposal for Everyday Peace Indicators.” Evaluation and Program Planning 36 (1): 56–63. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2012.07.001.

- Mac Ginty, R. 2014. “Everyday Peace: Bottom-up and Local Agency in Conflict-Affected Societies.” Security Dialogue 45 (6): 548–564. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010614550899.

- Mac Ginty, R., and O. P. Richmond. 2013. “The Local Turn in Peace Building: A Critical Agenda for Peace.” Third World Quarterly 34 (5): 763–783. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2013.800750.

- McKenzie, L. 2015. Getting by: Estates, Class and Culture in Austerity Britain. Bristol: Policy Press.

- O’Driscoll, D. 2018. “Conflict in Kirkuk: A Comparative Perspective of Cross-Regional Self-Determination Disputes.” Ethnopolitics 17 (1): 37–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17449057.2017.1401789.

- O’Driscoll, D. 2019. “Building Everyday Peace in Kirkuk, Iraq: The Potential of Locally Focused Interventions.” SIPRI Policy Paper 54: 1–43.

- O’Driscoll, D., and B. Baser. 2019. “Independence Referendums and Nationalist Rhetoric: The Kurdistan Region of Iraq.” Third World Quarterly 40 (11): 2016–2034. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2019.1617631.

- O’Flynn, I., G. Sood, J. Mistaffa, and N. Saeed. 2019. “What Future for Kirkuk? Evidence from a Deliberative Intervention.” Democratization 26 (7): 1299–1317. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2019.1629906.

- Paffenholz, T. 2015. “Unpacking the Local Turn in Peacebuilding: A Critical Assessment towards an Agenda for Future Research.” Third World Quarterly 36 (5): 857–874. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.1029908.

- Read, R., and R. Mac Ginty. 2017. “The Temporal Dimension in Accounts of Violent Conflict: A Case Study from Darfur.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 11 (2): 147–165. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17502977.2017.1314405.

- Romano, D. 2007. “The Future of Kirkuk.” Ethnopolitics 6 (2): 265–283. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17449050701345033.

- Sadiqi, F., and M. Ennaji. 2006. “The Feminization of Public Space: Women’s Activism, the Family Law, and Social Change in Morocco.” Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies 2 (2): 86–114. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/jmw.2006.0022.

- Selimovic, J. M. 2019. “Everyday Agency and Transformation: Place, Body and Story in the Divided City.” Cooperation and Conflict 54 (2): 131–148. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0010836718807510.

- Skeggs, B. 2004. Class, Self, Culture. London: Routledge.

- Smith, A. 2008. “The Limits of Everyday Nationhood.” Ethnicities 8 (4): 563–573. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/14687968080080040102.

- Spelman, E. V. 1988. Inessential Woman: Problems of Exclusion in Feminist Thought. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Su’edi, A. 2012. “Kirkuk, a conflict point between Baghdad and Erbil.” Kirkuk Now. May 01. http://kirkuknow.com/english/index.php/2012/05/kirkuk-a-conflict-point-between-baghdad-and-erbil/

- Vogel, B. 2018. “Understanding the Impact of Geographies and Space on the Possibilities of Peace Activism.” Cooperation and Conflict 53 (4): 431–448. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0010836717750202.

- Wedeen, L. 2009. “Ethnography as Interpretive Enterprise.” In Political Ethnography: What Immersion Contributes to the Study of Power, edited by E. Schatz, 75–94. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Wibben, A. T. R., C. C. Confortini, S. Roohi, S. B. Aharoni, L. Vastapuu, and T. Vaittinen. 2019. “Collective Discussion: Piecing-Up Feminist Peace Research.” International Political Sociology 13 (1): 86–107. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ips/oly034.

- Wolff, S. 2010. “Governing (in) Kirkuk: Resolving the Status of a Disputed Territory in post-American Iraq.” International Affairs 86 (6): 1361–1379. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2346.2010.00948.x.