Abstract

This introductory contribution examines the ‘Global South’ as a meta category in the study of world politics. Against the backdrop of a steep rise in references to the ‘Global South’ across academic publications, we ask whether and how the North–South binary in general, and the ‘(Global) South’ in particular, can be put to use analytically. Building on meta categories as tools for the classification of global space, we discuss the increasing prominence of the ‘Global South’ and then outline different understandings attached to it, notably socio-economic marginality, multilateral alliance-building and resistance against global hegemonic power. Following an overview of individual contributions to this volume, we reflect on the analytical implications for using the ‘Global South’ category in academic research. Insights from China, the Caribbean, international negotiations or academic knowledge production itself not only point to patterns of shared experiences but also highlight the heterogeneity of ‘Southern’ realities and increasing levels of complexity that cut across the North–South divide. Overall, we argue for an issue-based and field-specific use of the ‘Global South’ as part of a broader commitment to a more deliberate, explicit and differentiated engagement with taken-for-granted categories.

Introduction

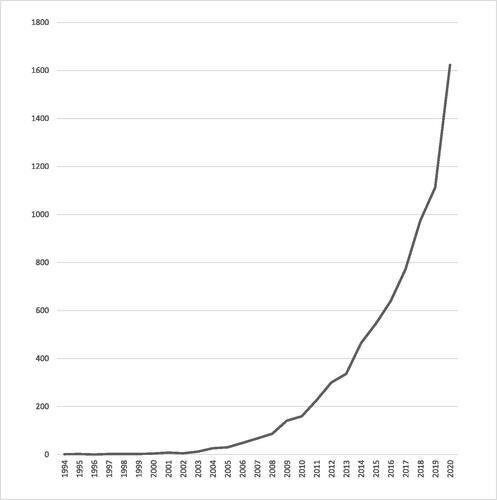

The ‘Global South’ has been on the rise – at least in academic scholarship. According to the abstract and citation database Scopus, references to the ‘Global South’ in publications across disciplines have grown almost exponentially since the 1990s, with a particularly steep increase over the last 15 years.Footnote1 Relative to this expanding popularity, however, there has only been a limited engagement with explicit definitions and de facto understandings.Footnote2 By and large, ‘South’-related terminology has been used as a shorthand for Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, and parts of Asia and Oceania, with contours often remaining blurred.Footnote3 Most publications framing research as focussing on the ‘Global South’ also have surprisingly little to say about the analytical value of this meta category for making sense of empirical phenomena.Footnote4 Although there are a number of contributions discussing concepts and dynamics behind the notion of the ‘(Global) South’ across the humanities and social sciences,Footnote5 detailed discussions have not reached the mainstream of academic engagement.

This volume builds on different disciplinary strands in order to investigate the analytical value of the ‘Global South’ category for research on world politics. We understand the study of world politics as a key subject of political science and international relations that is also covered by other social science disciplines, such as sociology, economics, geography and anthropology, when they focus on questions of governance and institutional power at regional and global levels. While this approach includes a wide range of actors and structures, the study of world politics has traditionally focussed on nation states and international organisations, with subnational and transnational dynamics added to the mix in accord with changes in the international system. All along, meta categories inspired by cardinal points have been popular frames for (the analysis of) international and transnational affairs. References to ‘East’ and ‘West’, in particular, build on a trajectory as socio-cultural categories leading back to a period well before they came to signify ideological division during the Cold War.Footnote6 Whereas ‘North’ and ‘South’ framings were popularised with decolonisation processes across Africa and Asia, the steep rise in references to the ‘Global South’ in the analysis of world politics is a rather recent phenomenon and warrants a more detailed look at empirical foundations and conceptual implications.

As a whole, this volume focuses on the extent to which the ‘Global South’ is a helpful conceptual tool for studying world politics, and how it can be put to use analytically. Individual contributions employ the ‘Global South’ category from the perspective of different sub-fields of inquiry, from global governance to transnational sociology and urban studies. In what follows, we elaborate on the increasing prominence of the ‘Global South’ as a meta category and discuss different understandings of what the ‘Global South’ has come to stand for. Building on an overview of individual contributions, we then reflect on the implications of their findings for using the ‘Global South’ in academic research. A central motivation behind this collection is to connect detailed empirical work with broader conceptual reflections. Beyond the diversity of evidence discussed across its pages, the volume aims at contributing to a more deliberate, explicit and differentiated engagement with taken-for-granted meta categories.

The ‘Global South’: a booming meta category

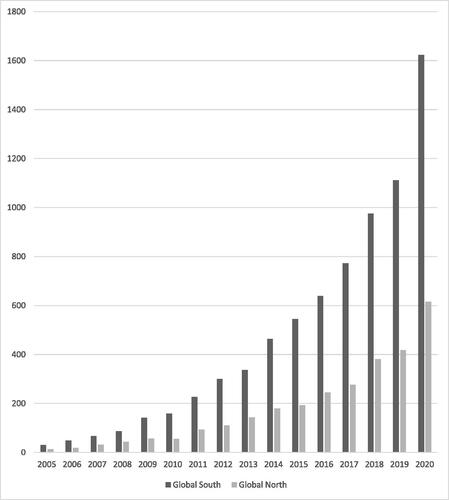

Across disciplines and academic outlets, the notion of the ‘Global South’ has become a popular device for framing research. While the use of ‘South’-related terminology has expanded across the board, Elsevier’s Scopus database provides a helpful proxy for mapping the evolution of this trend in peer-reviewed Anglophone publications over the last decades.Footnote7 It suggests that references to the ‘Global South’ in titles, abstracts and keywords have particularly expanded over the last few years, with one registered publication mentioning the term in 1994, 30 in 2005 and more than 1600 in 2020 (). The increase is no less substantial when put in relation to the overall rise of registered publications, meaning that there has been both an absolute and a relative growth in research centring around ‘Global South’ framings.Footnote8 This ‘boom’Footnote9 has been a general one across thematic areas and disciplines, and it has – not unexpectedly – been closely connected to publishing outlets that focus on the ‘developing world’, notably Third World Quarterly.Footnote10

Figure 1. The rise of the ‘Global South’ in academic publications: Number of publications in Scopus mentioning the term “Global South” in their title, abstract and/or keywords (1994-2020).Source: Authors’ own elaboration based on data in Scopus, ‘Keyword Search’.

This substantial upsurge in usage, however, has not contributed to an overall more systematic engagement with the notion of the ‘Global South’. Rather to the contrary: A cursory look at recently published articles suggests that most publications containing references to the ‘Global South’ take the category as a given, without explicitly defining what the ‘Global South’ stands for, or – perhaps even more importantly – to what extent a ‘Global South’ framing actually adds to their analytical discussion.Footnote11 There has been a tendency to frame all kinds of research on empirical phenomena within vast sets of spaces otherwise, or simultaneously, referred to as ‘Third World’, ‘developing world’ or ‘non-Western’Footnote12 as ‘research on the Global South’,Footnote13 while a systematic engagement with actual links across sites and the category itself is often missing.Footnote14

Categories, broadly defined, are classes of phenomena regarded as sharing a specific set of characteristics. In order to make the ‘metageographies’Footnote15 of world politics comprehensible, meta categories – as contingent and/or ill conceived as they might turn out to be – are tools for classifying global space.Footnote16 In a way, meta categories help to categorise categories: They offer a framework for making the world at large palpable, and thus provide a reference for other attempts to classify and categorise.Footnote17 For centuries, politico-geographical meta categories have shaped imaginaries of global space. Many of these categories have centred around binaries such as East/West, Orient/Occident or primitive/advanced, connected to the fundamental distinction between Self and Other.Footnote18 The North–South dyad builds on this trajectory of attempts at ordering the world via the ‘allegorical application’Footnote19 of binary frames; and the ‘(Global) South’, in particular, has entered the basic vocabulary for meaning-making across academic and policy circles.Footnote20

The use of the ‘Global South’ as a shorthand for various phenomena unfolding outside the ‘Western-Northern’ world is thus a rather recent phenomenon, but academic practices suggest that it has already become a staple for research on world politics. Not only the number of publications that frame their research with reference to the ‘Global South’ has risen exponentially, but there has also been a marked increase in university institutes, projects or professorships – notably across ‘Northern-Western’ academiaFootnote21 – that carry the ‘Global South’ in their title.Footnote22 On the one hand, this increase in references to the ‘Global South’ can be qualified as an important step towards including empirical phenomena that had long been excluded from the mainstream study of world politics.Footnote23 Borrowing a term from Manuela Boatcă’s contribution to this volume, this development carries the potential of adding a ‘Southern’ to the so far dominant – and often implicit – ‘Northern’ lens of academic inquiry. Within an academic landscape that has been dominated by researchers and funding bodies based in Europe and North America, the ‘Global South’ framing can serve the purpose of acknowledging actors and spaces that have long been neglected by mainstream social science research.Footnote24

On the other hand, however, a closer look at how North–South meta categories have been used reveals a curious and telling one-sidedness. If we assume that the ‘Global South’ needs to have meaning as a category juxtaposed to the ‘Global North’, it is noteworthy that although references to the former have risen exponentially, those to the latter have remained considerably less prominent (). Whereas hardly anyone would think about framing studies on, say, US politics, French bureaucracy or Brexit negotiations as ‘Global North’ research, an increasing body of work on phenomena within and across Asia, Africa and Latin America is indeed labelled as ‘research on the Global South’, often without a consideration of what this framing implies. This asks for a more detailed examination of how the ‘Global South’ is used, and what it is taken to stand for. As a meta category in the analysis of world politics, it suggests a certain level of homogeneity, or at least a common denominator among ‘Southern’ countries and regions. More often than not, however, this – usually implicit – assumption is not substantiated. The central characteristics that arguably define actors and spaces as belonging to the ‘Global South’ are not explicitly addressed, and the ‘Global South’ is instead used as a trope for research done in or on what is otherwise referred to as ‘developing countries’.Footnote25 Beyond a relatively small set of publications that explicitly focus on and problematise ‘South’ or ‘South–South’ assignations, the ‘Global South’ has largely become a taken-for-granted category:Footnote26 Most use the term without further explanation and assume that others know what is meant by it.

Who, what and/or where is the ‘Global South’ thought to be?

What does the category ‘Global South’ stand for? Where is the ‘Global South’ thought to be, and who is seen as embodying and/or speaking for it? In social science literature, ‘South’-related terminology has mostly been used not simply as a reference to the strictly defined hemispheric south – landmasses and waters south of the equator – but as a general rubric for the decolonised nations located roughly, but not exclusively, south of the old colonial centres of power.Footnote27 The geographic imaginary evoked by the ‘(Global) South’ and related questions of agency have been connected with, and enhanced through, a reference to global relationality, focussing on people, institutions and spaces outside the ‘Northern–Western’ core of political and economic interactions within the international system. More or less explicitly, the ‘Global South’ has been used to discuss not only systemic inequalities stemming from the ‘colonial encounter’ and the continuing reverberations of (mostly) European colonialism and imperialismFootnote28 but also the potential of alternative sources of power and knowledge.Footnote29

While ‘developing/underdeveloped world’ and ‘Third World’ (designating places beyond the two superpowers of the Cold War) had become dominant frames in debates about international inequalities and multilateral dynamics during the first few decades following the Second World War, ‘South’-related terminology was initially far less prominent.Footnote30 According to Nour Dados and Raewyn Connell, the notion of the ‘South’ being connected to patterns of politico-economic difference goes back to Antonio Gramsci’s reflections on how southern Italy had been colonised by northern Italy, and it later merged with debates about core–periphery dynamics in international trade and development.Footnote31 Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, and particularly with the end of the Cold War, the ‘South’ became, as Jacqueline Braveboy-Wagner has argued, ‘an acceptable overarching term for referencing former Third World countries and identifying the uniqueness of the many socioeconomic and environmental issues affecting them’.Footnote32

In this context, the qualifier ‘Global’ as an add-on to the ‘South’ has carried at least two broad connotations.Footnote33 First, it has served as a means to underline the increasing interconnectedness of social relations that place questions about ‘North’ and ‘South’, rich and poor, colonisers and colonised, developed and developing in a global(ised) context.Footnote34 Second, it has been used to adapt the North–South terminology of the 1970s in order to highlight the expanding clout of Southern players that now enjoy a reach well beyond Asia, Africa and Latin America.Footnote35 Debates about ‘emerging markets’ and ‘rising powers’ shaping the contours of what is described as an increasingly multipolar worldFootnote36 have been closely connected to the ‘rise of the South’ Footnote37 as an inherently ‘Global South’, marking ‘a shift from a central focus on development or cultural difference toward an emphasis on geopolitical relations of power’.Footnote38

While many complementary – and sometimes conflicting – meanings have been attached to the ‘Global South’ category, we briefly point to three understandings that have been particularly prevalent in the analysis of world politics.Footnote39 First, the ‘Global South’ has been taken to refer to poor and/or socio-economically marginalised parts of the world, usually from a country-based perspective.Footnote40 Country classifications, such as the one by the World Bank focussing on income per capita, have been popular devices attempting to map socio-economic development at aggregate levels, and to compare countries or regions over time.Footnote41 The Human Development Index, issued by the United Nations (UN) Development Programme, has been another important proxy listing countries according to quantifiable data, with reference to life expectancy, education and, again, income.Footnote42 Although most multilateral organisations do not rely on North–South language when presenting their classifications, many across both academic and policy circles in fact follow the logic of their indices when assuming that the ‘Global South’ comprises all countries outside the ‘high-income’, ‘advanced economies’ or ‘very high human development’ strata.Footnote43 The ensuing global mappings are reminiscent of the so-called Brandt Line, which, in the 1980 report of the Independent Commission on International Development Issues, suggested that North/South was vaguely synonymous with international divisions of rich/poor or developed/developing.Footnote44 Labels that stem from this logic have become an integral part of international classifications, such as the notion of least developed countries at the UN or the list of countries eligible for official development assistance, as defined by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.Footnote45 Narrow sets of material dynamics have stood at the centre of this understanding, with the ‘Global South’ often taken as a shorthand for spaces socio-economically less advantaged than those at the core of the world economy.Footnote46

Second – and often with implicit or explicit references to the first understanding – the ‘Global South’ has stood for different sets of cross-regional and multilateral alliances: a tricontinental policy space that, since the first few decades following the setting-up of the UN in 1945, has provided a framework and reference point for the development of ideas about, and concrete steps towards, platforms and cooperation practices beyond those dominated by former colonial powers and their allies.Footnote47 Building on the 1955 Bandung Conference, the Non-Aligned Movement and the idea of ‘Southern’ solidarity, this understanding of the ‘Global South’ has been closely associated with formerly colonised countries, or, more generally, countries that have evolved in the peripheries of the international system.Footnote48 For representatives of countries referred to (or self-referring) as ‘developing’, notably members of the Group of 77 (G77) at the UN, North–South language has remained an important reference in multilateral negotiations.Footnote49 Repeatedly challenging the structural privilege of ‘Northern’ states, G77 countries have been key players in the empirical processes informing the burgeoning debate about South–South cooperation across academic and policy circles.Footnote50 Despite increasing levels of heterogeneity among its 134 members, the G77 continues to co-shape debates about North–South issues in multilateral affairs, notably with regard to international cooperation and development finance.Footnote51

Third, the ‘Global South’ has been presented as a space of resistance against not only ‘Northern’ dominance in multilateral settings but also neoliberal capitalism and other forms of global hegemonic power more generally. From the tricontinental movement to the Zapatista revolt and the World Social Forum, this understanding has been closely connected to post-colonial – and increasingly also decolonial – projects focussing on the persistence of racial inequalities and systemic domination across the globe.Footnote52 In line with this, both activists and academics have suggested that the ‘Global South’ can be potentially anywhere but, as an alternative space, is always also connected to both specific local contexts and global power structures.Footnote53 This understanding has made an explicit move beyond state-based understandings by highlighting that domination, and resistance to it, do not unfold only along national borders, and that a fruitful take on the notion of the ‘Global South’ thus consists in reframing the category as a marker for concrete instances of anti-hegemonic engagement, also and particularly through transnational social spaces.Footnote54 Whereas, in line with the first two understandings outlined above, the ‘Global North’ is usually taken to refer to concrete sets of states such as ‘traditional donors’ or ‘industrialised economies’, here it is not limited to specific countries. Instead, the ‘Global North’ appears as a general reference to hegemonic forces that dominate global social structures through economic flows, powerful forms of meaning-making and/or explicit coercive measures.

While there are many potential ways of filling the ‘Global South’ with meaning, most accounts implicitly or explicitly make reference to one or several of the three understandings outlined here.Footnote55 Some, such as in Vijay Prashad’s work, also combine all three, making the case for a transnational movement building on the multilateral trajectory of post-colonial and/or developing countries to formulate alternatives to the capitalist status quo.Footnote56 Given the variety of meanings attached to ‘South’ and ‘North’, and potentially significant shifts over time,Footnote57 questions about the contours and whereabouts of the ‘Global South’ can arguably only be answered with reference to the subject matter, policy field and context in which they are asked. Contributions to the study of world politics that frame their research via the ‘Global South’ have tended – with or without explicit definitions – to rely on a state-centred combination of socio-economic marginality, on the one hand, and multilateral alliances at least partly stemming from these rather marginal international positionalities, on the other.

In discussions about international relations, global development or multilateral negotiations, G77 membership has been a prominent proxy for mapping what the ‘Global South’ is often meant to stand for. Some have indeed made an explicit argument in favour of the analytical relevance of the ‘Global South’ category, arguing that there is still a meaningful level of commonality among countries from the ‘Global South’ in terms of their roles and positions in international affairs that warrants the use of the meta category for examining foreign policies.Footnote58 Others, such as Amitav Acharya, have highlighted the growing differentiation among ‘Southern’ countries, suggesting an increasing divide between Poor vs. Power South, First vs. Second South or the two poles of a ‘two-track South’.Footnote59 The latter contributions underline that the ‘rise of the South’ has affected countries and societies differently, and that the expanding clout of India and China has very little to do with the realities facing a large number of countries in Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.Footnote60

Contributions to this volume

With reference to the rise of the ‘Global South’ in academic publications, the relative lack of detailed engagement with it across mainstream accounts, as well as existing attempts to discuss its potential and limits, this volume asks how, and to what extent, the ‘Global South’ can be a helpful meta category for studying different aspects of world politics. Building on previous questionings of politico-geographical terminologies,Footnote61 the volume offers a contemporary analysis set around and engaging with present-day pluralities. It goes back to a conference hosted in Berlin in 2018 whose purpose was not only to connect academics based in Germany with global debates about South–North relations but also, and more specifically, to take a critical look at the increasingly popular category of the ‘Global South’ itself. Participants were invited to submit accounts that centre around the ‘Global South’ as a meta category and examine whether, and to what extent, it is analytically useful, how it should be studied, and what it has to contribute to the investigation of empirical phenomena. Contributions that have made it into this volume are not representative of voices on or disciplinary debates about ‘North’ and ‘South’;Footnote62 they instead offer different approaches towards an explicit take on the ‘Global South’ as a phenomenon in its own right, and thus join a growing body of work on South–North relations, South–South cooperation and, more generally, frames used to make sense of global social space.Footnote63

In line with the strong emphasis on so-called rising powers from the ‘South’ in academic debates over the last decade, the volume’s main part opens with Andrew Cooper’s piece on Indian and Chinese engagement in global governance fora.Footnote64 Cooper examines how the two powerhouses, respectively, have positioned themselves with reference to their global power aspirations, on the one hand, and questions of solidarity with (the rest of) the ‘Global South’, on the other. With reference to the Group of 20 (G20) and the Brazil-Russia-India-China-South Africa (BRICS) alliance, he shows how the ‘Global South’ – understood as a multilateral grouping of developing countries – offers a helpful reference to locate and compare Chinese and Indian engagement patterns. Whereas India has often struggled with its ambivalent standing, Cooper argues, China has been quite successful in manoeuvring both inside and outside spaces traditionally associated with the multilateral ‘South’.

China’s particularities also take centre stage in the contribution by Paul Kohlenberg and Nadine Godehardt.Footnote65 They show that, in official Chinese sources, the ‘South’ has been increasingly defined not as a fixed or absolute category but through its relationship with China’s own initiatives. From that perspective, the ‘South’ as a cooperative space is not limited to Africa, Asia and Latin America but may well reach as far as Central and Eastern Europe. More generally, Kohlenberg and Godehardt argue, Chinese accounts have assigned less relevance to the binary divisions between ‘North’ vs. ‘South’ or developed vs. developing countries. Instead, regional platforms and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), in particular, have created ‘China + X’ arrangements that frame global positions primarily with reference to China itself.

The historical force and continuing impact of North–South fault lines, in turn, are at the heart of Manuela Boatcă’s piece.Footnote66 With reference to citizenship, Boatcă examines the inherent link between ‘Northern’-focussed tales of enlightened emancipation and exclusions from it, as well as ‘Southern’ attempts to challenge and/or subvert hegemonic forces. Seen through a ‘Southern lens’, she argues, mainstream accounts that centre around the French and US revolutions in the late eighteenth century tell a biased story, one that operates through a ‘Northern lens’ and ignores the many ways in which colonial and post-colonial subjects have remained at the margins of, or have been explicitly excluded from, the promise of citizenship. Moving from the Haitian revolution all the way to present-day attempts by Caribbean states to commodify their citizenship rights, Boatcă holds that although ‘Southern’ constituencies still experience marginality in terms of mobility and passport access, ‘Southern’ agency was and continues to be a substantial force in altering and subverting ‘Northern’-dominated citizenship accounts.

Continuing reverberations of relations between colonising forces from the ‘North’ and colonised spaces in the ‘South’ also stand at the centre of Tobias Berger’s contribution.Footnote67 The unequal entanglements between ‘Northern’ colonisers and ‘Southern’ colonised societies, Berger argues, have conditioned the development of a particular kind of legal pluralism characterised by the state being only one among many possible sources of legal reasoning. With reference to multilateral organisations’ support for village courts in Bangladesh, he shows that informal elements in ‘Southern’ legal systems, although often depicted as pre-colonial, can indeed be the co-product of continuing ‘Northern’ influence. While the representatives of ‘Southern’ societies continue to face the challenges of globally marginalised positionalities, including with regard to their ‘own’ traditions, Berger agrees with Boatcă in arguing that ‘Southern’ players indeed have a meaningful – if often unacknowledged – level of agency in co-shaping and/or subverting the outcome of North–South encounters.

The very contours of the ‘Global South’ take centre stage in Sebastian Haug’s contribution.Footnote68 With reference to Mexico and Turkey, he suggests to explicitly focus on the empirical boundaries between North–South designations in order to better grasp the complexities inherent in the ‘Global South’ category. Building on Edward Soja’s trialectics of Firstspace, Secondspace and Thirdspace, Haug outlines the material, ideational and lived realities connected to the ‘Global South’ and examines each dimension with reference to insights from Mexico and Turkey. In terms of spatial mappings provided by development indices and multilateral alliances, he argues that both countries appear as sets of actors and spaces that can be described as both ‘Southern’ and ‘Northern’, or neither ‘Southern’ nor ‘Northern’. The life-worlds of Mexican and Turkish officials, in particular, highlight the complexities stemming from binary mappings in general and the idea of the ‘Global South’, in particular.

Siddharth Tripathi’s contribution takes this focus on concrete life-worlds as a backdrop for engaging with the epistemic hierarchies that characterise current patterns of academic knowledge-production itself.Footnote69 With reference to the discipline of international relations, Tripathi argues that the North–South divide is a visible feature across institutions and outlets focussing on academic engagement with international studies. Disciplinary debates about the very concept of the ‘Global South’, he suggests, provide illustrative insights into the extent to which researchers and students in ‘South’-based institutions have remained at the margins. Drawing on Paulo Freire’s work and participatory action research methodology, Tripathi outlines ways to address current biases. Dialogic encounters, he argues, are one tool for expanding inclusion, requiring a substantial commitment to self-reflexivity on behalf of all those involved as well as a focus on material factors that limit or enable participation.

Florian Koch translates the general motivation behind this volume into a review of the tendency in urban studies to employ ‘cities of the Global South’ terminology.Footnote70 Koch argues that, by and large, urban studies research often fails to address the conceptual implications of the ‘Global South’ category. With reference to cities’ transnational engagement, Koch examines basic differences between ‘Southern’ and ‘Northern’ urban spaces when it comes to acting on climate change and highlights that research on cities as transnational actors needs to take these structural patterns into account. At the same time, however, his analysis stresses that North–South dynamics are only one factor among many. While simplistic ‘Global South’ or ‘Global North’ assignations are necessarily of limited analytical value, Koch concludes, a focus on North–South divergences as one perspective among others is a helpful tool for understanding current urban realities.

Adriana Abdenur takes up both Koch’s focus on climate change and a differentiated use of North–South framings in her viewpoint discussion of the Climate and Security agenda at the UN.Footnote71 She shows that the diversification of interests among G77 member states has rendered the ‘Global South’ category a rather unproductive tool for analysing multilateral positions on the climate–security nexus. At the same time, however, she argues that references to ‘North’ and ‘South’ that acknowledge heterogeneity still help to highlight underlying historical-structural features that condition the engagement of both state and non-state actors with UN agenda-setting processes, notably with regard to the availability of financial and human resources for producing knowledge and shaping multilateral deliberations.

In the final contribution to this volume, Laura Trajber Waisbich, Supriya Roychoudhury and Sebastian Haug take inspiration from Chimamanda Ngozie Adichie’s caveat against single stories.Footnote72 Focussing on questions of agency and positionality, they discuss some of the unease connected to using North–South framings as well as the plurality of evolving understandings of what the ‘Global South’ stands for, and who belongs to it. With reference to the notion of polyphony, they argue for combining a focus on specific meanings and their implications with a broader and more self-reflexive take on the inherent complexities of meta categories.

The ‘Global South’ as a meta category for studying world politics

The considerable array of empirical dynamics and conceptual issues discussed in this volume provide a rich set of insights into the potentials and limits of North–South dichotomies for the analysis of world politics. Individual contributions highlight the extent to which attributions such as ‘Southern powers’ contain a simplistic classification that often falls short of not only accounting for the complexities that all empirical evidence necessarily contains but also contributing a meaningful analytical perspective. More generally, they suggest that cursory applications of politico-geographical meta categories, notably when transformed into singular labels, are inherently limited and often hide more than they reveal.

The grand potential of meta categories, in turn, consists not only of making the world at large palpable – as part of a necessary reduction of complexity – but also of pointing to empirical patterns that require more detailed attention. The analysis of continuing reverberations of colonial and imperial domination, long-standing socio-economic cleavages or evolving practices of multilateral negotiations requires meta categories to make sense of complex entanglements and link broad dynamics to concrete experiences. This is where the ‘Global South’, in Berger’s words, can be helpful as ‘a relational category that sensitises us for the historically grown marginalisations within international hierarchies and their epistemological implications’. As Koch highlights, questions about ‘North’ and ‘South’ are necessarily one among many potential perspectives on empirical phenomena in the study of world politics. The question is thus how North–South categories fit into the specific research focus at hand, and to what extent they help to embed or sharpen the analysis.

As this volume argues for a more explicit and nuanced – issue-based and field-specific – use of the ‘Global South’ category, the deliberate engagement with definitions is a first step. Depending on the issue under investigation, ‘Global South’ terminology can mean different things to different people, and different subfields of academic inquiry or research communities might have different implicit understandings of what the ‘Global South’ is supposed to stand for. Individual contributions illustrate this diversity by touching upon all three understandings of the ‘Global South’ outlined above, with reference to socio-economic marginality being closely related to (post-)colonial dynamics (eg Tripathi), multilateral alliances (eg Abdenur) and/or counter-hegemonic agency (eg Boatcă). Attempts at devising a widely accepted and clear-cut definition of the ‘Global South’ would not only fail in light of the existing proliferation of understandings but also neglect the potential fruitfulness of acknowledging the evolving and heterogeneous nature of an increasingly popular meta category. Instead, we suggest that taking the ‘Global South’ seriously, as a category in its own right, would improve the ways in which scholars make sense of world politics. In addition to making definitions or assumptions explicit, this also entails a deliberate reflection on what the category helps to discuss, understand, explain or uncover, and to acknowledge where it ceases to be a helpful device for inquiry. Here, the question of scale is only one among many: The ‘Global South’ as a meta category can potentially be as helpful for investigating multilateral power structures as for the analysis of organisational processes within ministerial bureaucracies or individual life-worlds, as long as the link to the meaning(s) ascribed to the ‘Global South’ remains an integral part of the analysis.Footnote73

With regard to empirical complexities, this volume shows that the ‘Global South’ can be used to produce a range of rather different – if complementary – accounts about phenomena that connect concrete experiences to global macro dynamics. Beyond often abstract institutional processes, this is also, and importantly, about people’s everyday practices. Haug’s use of Soja’s Thirdspace heuristic offers a framework for a systematic assessment of meta categories that moves from material to ideational phenomena and finally centres around the lived experiences of individuals and groups in how meaning-making unfolds, within and across country borders. Here, concrete life-worlds appear as the foremost spaces where otherwise rather abstract categories take on palpable – if shifting – contours. Tripathi directs this focus on individual experiences at those who think, write and speak about world politics as part of their professional endeavours. With Freire’s participatory action research, he offers a concrete suggestion for how to broaden ‘Global South’-related discussions, include the voices of individuals who often remain excluded from intra-disciplinary debates and engage more explicitly with the dialogical potential between different positions and viewpoints.Footnote74 By and large, contributions to this volume agree that a focus on relationality is key for making sense of the ‘Global South’ as part of a duality that always carries at least implicit references to (individuals and institutions in) the ‘Global North’ as its Other. Whether the ‘Global South’ is a site of marginalisation, an agent of emancipation, both, or something different altogether depends on the issue under investigation; and it is individual people who embody the concrete contours of what is then subsumed to belong to the study of world politics.

This points to another key issue when studying the ‘Global South’: the choice of empirical material for investigating and reflecting on ‘South’-related phenomena. Since the first decade of the 2000s, a strong focus has been placed on the role of so-called rising or emerging powers from the ‘Global South’.Footnote75 The related expansion of references to South–South cooperation across policy and academic circles has taken a somewhat broader approach, but a strong focus has always been directed at Brazil, China and India as the ‘locomotives of the South’.Footnote76 In this volume, all contributions engaging with states often grouped as G20 ‘rising powers’ highlight the evolving ambiguities of North–South assignations.Footnote77 The ambivalence of Brazil’s and India’s evolving positioning vis-à-vis ‘South’ framings alluded to by Waisbich, Roychoudhury and Haug as well as Abdenur resonates with China’s idiosyncratic approach discussed by Kohlenberg and Godehardt and Haug’s discussion of Mexico and Turkey as players at the margin of the ‘Global South’. Cooper’s focus on the ambivalent oscillation between or proactive attempts to combine ‘Southern’ solidarity and an expanding global clout captures dynamics set to condition the future development of multilateral and minilateral global governance fora. Beyond a focus on economic and political powerhouses, Berger’s engagement with Bangladesh and Boatcă’s emphasis on the relevance of the Caribbean highlight that a detailed understanding of ongoing relations between ‘Global South’ and ‘Global North’ requires an engagement with spaces that – like Haiti – often fall off the radar as agents of change but have played, and often still play, key roles in the relationally connected processes of world politics.

The most far-reaching reverberations in terms of the empirical processes under investigation in this volume, however, might well affect the positional framings of all countries, big and small, in rather unprecedented ways. According to Kohlenberg and Godehardt’s analysis, China’s growing clout in world politics seriously undermines the very relevance of ‘South’ and ‘North’ as meta categories. If, as they argue, China’s expanding engagement is in the process of reorganising positionalities so as to replace traditional binaries with relationality towards China itself, North–South assignations – with the baggage of related binaries – might soon lose (some of) their purchase. Attempts at accounting for ‘intra-South’ heterogeneity in terminological terms are unlikely to hold in the face of a global meta geography co-shaped by an increasingly dominant China. Future sets of categories for world ordering – such as positionings vis-à-vis BRI, for instance – are likely to incrementally replace and/or fuse with references to ‘North’ and ‘South’.

Conclusion

The increasing prominence of the ‘Global South’ as a meta category in the study of world politics – combined with the general vagueness of, and multiple understandings attached to, ‘South’-related terminology – has provided the starting point for this volume. While empirical realities have always been considerably more complex than binary frames suggest, individual contributions demonstrate that North–South heuristics can be put to analytical use in a variety of ways to investigate macro dynamics that continue to shape (the perception of) different segments of world politics. They also highlight that, although recent shifts in power and wealth – also but not only related to China – undoubtedly pose an additional challenge to the persuasiveness of North–South framings,Footnote78 these shifts by no means foreclose the necessity to critically engage with classifications and analytical tools. To the contrary, the focus on the ‘Global South’ highlights the enduring need to reflect on, and make sense of, meta categories, including ‘South’ and ‘North’, ‘West’ and ‘East’ or, say, the division between BRI and non-BRI countries.

Overall, this volume contributes to the discussion of why it matters to focus on meta categories whose meaning is often taken for granted, and it offers insights into approaches and conceptual instruments – such as polyphonies, Freire’s dialogic encounters, Soja’s Thirdspace or the distinction between Southern and Northern lenses – that can help to unpack them. Across academic traditions and disciplines, the explicit definitions and implicit meanings of meta categories shape the ways in which the world is examined and written about. The deliberate engagement with the ‘Global South’ that individual contributions in this collection argue for reflects a broader and more conscious approach towards the terms we use to frame research questions and position ourselves in a rapidly evolving landscape of scholarly inquiry. This volume thus aims to provide not only insights into the benefits and limits of using the ‘Global South’ as an analytical tool but also a space for reflection on, and inspiration for, how to engage with meta categories in academic inquiry.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to all Special Issue contributors as well as those who were part of the initial steps of this project, including Élodie Brun, Éric Degila, Harald Fuhr, Christine Hackenesch, Ottilia Anna Maunganidze, Melanie Müller, Ruhee Neog, Philipp Schönrock, Matthew Stephen, Christina Stolte, Hannes Warnecke-Berger, Annette Weber, Silke Weinlich and Claudia Zilla. The Fritz Thyssen Foundation provided financial resources, and the German Institute for International and Security Affairs/SWP provided in-kind and administrative support. We are also grateful to Heike Großer and Lara Hammersen for their research assistance; the team at Third World Quarterly – particularly Madeleine Hatfield, Siri Nylund, Emma Smith and Jeremy Brown – for their logistical and editorial support; and Max-Otto Baumann, Manuela Boatcă, Élodie Brun, Aline Burni, Johanna Chovanec, Christine Hackenesch, Heiner Janus, Cynthia Kamwengo, Laura Trajber Waisbich and Claudia Zilla for feedback on earlier versions of this paper. Finally, we are also indebted to our reviewers as well as more than 40 colleagues from five continents who supported the extensive Special Issue peer-review process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sebastian Haug

Sebastian Haug is Post-Doctoral Researcher at the German Development Institute/Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), where he focuses on the United Nations, South–North relations and the ‘in-between’. He has published on international cooperation and multilateral politics in Global Governance, Third World Quarterly and Rising Powers Quarterly. Sebastian used to work for the United Nations in China and Mexico and has been a visiting scholar at New York University, El Colegio de México and the Istanbul Policy Center. He holds a Master of Science from the University of Oxford and a PhD from the University of Cambridge, where he is an associate researcher. In 2021/2022, Sebastian is also an Ernst Mach Fellow at the Institute for Human Sciences (IWM) in Vienna.

Jacqueline Braveboy-Wagner

Jacqueline Braveboy-Wagner is Professor of political science in the Graduate School of the City University of New York as well as in the Colin Powell School of Civic and Global Leadership at the City College of New York. She is a specialist in foreign policy, diplomacy and global development, particularly with respect to small states (and specifically Caribbean states) as well as the nations of the Global South in general. Jacqueline has authored or edited 11 books, including Diplomatic Strategies of Leading Nations in the Global South (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016); Institutions of the Global South (Routledge, 2009/2010); and The Foreign Policies of the Global South: Rethinking Conceptual Frameworks (Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2003). She is the founder of the Global South Caucus of the International Studies Association.

Günther Maihold

Günther Maihold has been Deputy Director of the German Institute for International and Security Affairs/Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP) and a Professor of political science at Freie Universität Berlin since 2004. His current research focuses on governance in international relations, organised crime and sustainability in global supply chains. From 2011 to 2015 he was on leave to assume the Wilhelm and Alexander von Humboldt Chair at El Colegio de México and Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México in Mexico City. Günther serves as Principal Investigator of the Graduate School for East Asian Studies at Freie Universität Berlin and studied sociology and political science at the University of Regensburg, where he also received his PhD.

Notes

1 Most relevant publications come from the social sciences: see Scopus, “Keyword Search”; see also Pagel et al., “Use of the Concept ‘Global South’”; Kleinschmidt, “Differentiation Theory and the Global South.” For recent examples, see Barrowclough, Gallagher, and Kozul-Wright, Southern-led Development Finance; Bieler and Nowak, “Labour Conflicts in the Global South.”

2 See below for a discussion of this lack of engagement. For contributions related to the analysis of world politics that do include explicit discussions of the ‘(Global) South’ and/or South–South cooperation, see Alden, Morphet, and Vieira, The South in World Politics; Prashad, Poorer Nations; Tickner, “Core, Periphery and (Neo)Imperialist International Relations”; Brun, Dumont, and Forite, “Relations Sud–Sud”; Wolvers et al., Concepts of the Global South; Braveboy-Wagner, Diplomatic Strategies of Nations in the Global South; Wagner, Moral Mappings of South and North; Kleinschmidt, “Differentiation Theory and the Global South”; Fiddian-Qasmiyeh and Daley, Routledge Handbook of South–South Relations; Horner and Carmody, “Global North/South”; Mawdsley, “South–South Cooperation 3.0”; Mawdsley, Fourie, and Nauta, Researching South–South Development Cooperation; Tickner and Smith, International Relations from the Global South.

3 See Dados and Connell, “Global South.” This general vagueness is not necessarily problematic, but the lack of explicit engagement arguably undermines meaningful exchange (see below).

4 Academic debates have had a tendency to focus on actors framed as ‘Southern’ rather than the analytical value of the ‘Global South’ as such.

5 See Santos, Conocer desde el Sur; Connell, Southern Theory; Levander and Mignolo, “Introduction: The Global South and World Dis/Order”; for a helpful overview, see Mahler, “Global South.”

6 Said, Orientalism; Dirlik, “Chinese History and the Question of Orientalism”; Ferguson, Civilisation: The West and the Rest; Mahbubani, Has the West Lost It?; Zarakol, Before the West.

7 On the expansion of references to the ‘Global South’ in Spanish, Portuguese and German, see Kleinschmidt, “Differentiation Theory and the Global South”; on the ‘South’ in Chinese policy discussions see Kohlenberg and Godehardt, “Locating the ‘South’ in China’s Connectivity Politics”; see also Pagel et al., “Use of the Concept ‘Global South.’” As the Scopus database relies primarily on Anglophone sources, further research should engage more systematically with the use of ‘South’-related terminology across linguistic communities.

8 The analysis of the absolute and relative increase in references to the ‘Global South’ is based on calculations with data in Scopus, “Keyword Search.”

9 On ‘booms’ of literature originating in different parts of the ‘Global South’, see Kantor, “Booms in Literatures of the Global South.”

10 According to Scopus, Third World Quarterly has been the foremost platform for academic debates related to the ‘Global South’: The first publications in the database mentioning the term in the 1990s (see eg Korany, “End of History”) and the majority of articles making references to the ‘Global South’ today have been published by TWQ.

11 For examples, see Nawyn et al., “Human Trafficking and Migration Management”; Kshetri, “Will Blockchain Emerge as a Tool”; Schia, “Cyber Frontier and Digital Pitfalls”; Singh and Ovadia, “Theory and Practice of Building Developmental States.” On comparative work that uses the ‘Global South’ as a broad reference, see Ramanzini Júnior and Luciano, “Regionalism in the Global South”; Offutt, “Evangelicals and Governance in the Global South.”

12 Although the use of ‘Third World’ has somewhat decreased, it still features prominently across publications; and the term ‘developing world’ continues to be employed far more often than both ‘Third World’ and ‘Global South’; see Scopus, “Keyword Search.” On the ‘non-West’, see Shilliam, International Relations and Non-Western Thought.

13 Ryan, “To Do Better Research.”

14 For an example regarding the gap between title and content, see Woertz, Reconfiguration of the Global South. Overall, the rise of references to the ‘Global South’ is thus arguably more a reflection of shifts in framing than an indication of the emergence of a separate research paradigm.

15 Lewis and Wigen, Myth of Continents.

16 See Kleinschmidt, “Differentiation Theory and the Global South.”

17 On classification, see Bailey, “Typologies and Taxonomies in Social Science.”

18 See Said, Orientalism; Dirlik, “Chinese History and the Question of Orientalism”; Dados and Connell, “Global South”; Wagner, Moral Mappings of South and North.

19 Dados and Connell, “Global South,” 13; see Wagner, Moral Mappings of South and North.

20 For policy-related discussions, see UNDP, Rise of the South; OECD, “Beyond Shifting Wealth”; UNCTAD, Forging a Path beyond Borders; Tricontinental, “About Tricontinental”; see also Haug, “Mainstreaming South–South and Triangular Cooperation.”

21 A comprehensive cross-regional and cross-lingual database would provide more substantial insights into whether North–South framings are indeed mostly employed by Northern academia. In the Scopus database, with its bias towards English-language sources, three South African universities rank among the most prolific institutions regarding research outputs framed via the ‘Global South’; see Scopus, “Keyword Search.” For a brief discussion of usage, agency and related motivations, see Waisbich, Roychoudhury, and Haug, “Beyond the Single Story.”

22 For examples, see units, projects and/or professorships at Freie Universität Berlin, the London School of Economics and Political Science, Lund University, the University of Cambridge, the University of Cologne or the University of Virginia. For a journal that, primarily embedded in literary and culture studies, explicitly centres around the notion of the ‘Global South’, see Duck, Global South.

23 See Braveboy-Wagner, “Idea of the Global South.”

24 On the importance of often-neglected ‘non-Western’ sources for research on world politics, see Shilliam, International Relations and Non-Western Thought.

25 For examples see note 11. This trend across academic and policy circles has also been corroborated by interviews conducted with United Nations officials and scholars working on world politics between 2016 and 2018; see Haug, “Thirding North/South.”

26 On background ideas, see Kornprobst and Senn, “Introduction: Background Ideas.”

27 Note the ambiguous positionalities of the United States and Canada in that regard.

28 See Quijano, “Coloniality and Modernity/Rationality”; Grovogui, “Revolution Nonetheless.”

29 See seminal contributions by Santos, Conocer desde el Sur; Connell, Southern Theory; Comaroff and Comaroff, “Theory from the South.”

30 On the ‘Third World’ as well as notions of ‘underdeveloped’ and ‘developing’, see Escobar, Encountering Development. On initial references to the ‘South’ in multilateral debates, particularly at the United Nations, see Haug, “Mainstreaming South–South and Triangular Cooperation.”

31 See Dados and Connell, “Global South.” On core–periphery dynamics, see Wallerstein, World-Systems Analysis; Rama and Hall, “Raúl Prebisch.”

32 Braveboy-Wagner, “Idea of the Global South.”

33 The ‘South’ without the qualifier ‘global’ has enjoyed more popularity in seminal contributions on North–South dynamics outside the study of world politics; see Connell, Southern Theory; Comaroff and Comaroff, “Theory from the South.”

34 See Rigg, Everyday Geography of the Global South.

35 See Gray and Gills, “South–South Cooperation and the Rise”; see also UNDP, Rise of the South; UNCTAD, Forging a Path beyond Borders.

36 On multipolarity and the multiplex order, see Acharya, “IR for the Global South”; Cooper and Flemes, “Foreign Policy Strategies of Emerging Powers”; see also Maihold, “Mexico: Leader in Search of Like-Minded Peers.”

37 UNDP, Rise of the South.

38 Dados and Connell, “Global South,” 12.

39 These understandings are not mutually exclusive but capture dominant strands of how the ‘Global South’ has been used. For an alternative presentation of definitions and meanings, primarily but not only with reference to literary and cultural studies, see Mahler, “Global South,” and Mahler, “What/Where Is the Global South?”

40 See Dados and Connell, “Global South”; this often, but not necessarily, includes cursory references to (post)colonial trajectories.

41 See Serajuddin and Hamadeh, “New World Bank Country Classifications.”

42 UNDP, Human Development Index.

43 For a recent example, see Hickel, Sullivan, and Zoomkawala, “Plunder in the Post-Colonial Era.” See also Fuhr, “Rise of the ‘South.’”

44 ICIDI, North–South, a Programme for Survival.

45 UN, “Least Developed Countries”; OECD, “DAC List of ODA Recipients”; see also Schwarz, “Global South … before I Learned.”

46 On current North–South cleavages regarding income and asset ownership, see Horner and Carmody, “Global North/South.”

47 On ‘Southern’ institutions, see Braveboy-Wagner, Institutions of the Global South; on tricontinental dynamics see Prashad, Poorer Nations; Mahler, From the Tricontinental to the Global South.

48 Including, for instance, Thailand and Turkey; see Zarakol, “Revisiting Second Image Reversed.” On Turkey’s complex relationship with the ‘Global South’, see Haug, “A Thirdspace Approach to the ‘Global South’”; Haug, “Thirding North/South.”

49 Weiss, “Moving beyond North–South Theatre”; Baumann, “Forever North–South?” On the G77, see Toye, “Assessing the G77”; on North–South language, see Haug, “Mainstreaming South–South and Triangular Cooperation.”

50 See UNDP, Rise of the South; Gosovic, “Resurgence of South–South Cooperation”; UNCTAD, Forging a Path beyond Borders; Mawdsley, “South–South Cooperation 3.0.”

51 Toye, “Assessing the G77”; Muchhala, “From New York to Addis Ababa”; Baumann, “Forever North–South?”

52 See Mahler, From the Tricontinental to the Global South; PACHA, “About the Journal”; Tricontinental, “About Tricontinental.” See also Sparke, “Everywhere but Always Somewhere”; Dados and Connell, “Global South.” For tensions between post-colonial research and “Global South” approaches, see Mahler, “Global South,” see Mahler, “Global South.”

53 Sparke, “Everywhere but Always Somewhere.”

54 For the ‘Global South’ as a reference for an ‘alternative global alliance’ among academics and activists, or activist-academics, see Dirlik, “Global South: Predicament and Promise.” For Global South Studies as a critical academic approach, see Mahler, “What/Where Is the Global South?”

55 This includes those who see the ‘South’ as a potential source for alternative forms of knowledge. For a detailed overview of different dimensions of ‘Global South’-related research and intellectual approaches, see Mahler, “Global South.”

56 Prashad, Poorer Nations; see Tricontinental, “About Tricontinental.” Although the ‘Global South’ has been particularly prominent among forces framed as ‘leftist’ or ‘progressive’, it has also been used in other contexts and for other purposes; see Kleinschmidt, “Differentiation Theory and the Global South,” 73; Mahler, “Global South in the Belly of the Beast.”

57 Such as with reference to multilateral alliances and, particularly, socio-economic proxies; see Dirlik, “Global South: Predicament and Promise.”

58 See Braveboy-Wagner, Diplomatic Strategies of Nations in the Global South; Braveboy-Wagner, “Idea of the Global South.”

59 See, respectively, Acharya, “Global International Relations (IR) and Regional Worlds”; Eyben and Savage, “Emerging and Submerging Powers”; and Alden, Morphet, and Vieira, The South in World Politics.

60 On the unease and potential controversies centring around ‘Global South’ designations, see Waisbich, Roychoudhury, and Haug, “Beyond the Single Story.”

61 See, for example, Harris, “End of the ‘Third World’?”

62 Although attempts were made to broaden participation throughout the duration of the project, a range of factors – including job insecurity, caring responsibilities and the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic – have meant that a number of conference participants were unable to submit and/or finalise manuscripts. This is unfortunate, particularly because it has disproportionately affected female scholars and participants from outside Germany.

63 On the main threads that connect individual contributions, as well as our take on the diversity of approaches and understandings, see the next section. See also Waisbich, Roychoudhury, and Haug, “Beyond the Single Story.”

64 Cooper, “China, India and the Pattern.”

65 Kohlenberg and Godehardt, “Locating the ‘South’ in China’s Connectivity Politics.”

66 Boatcă, “Unequal Institutions in the Longue Durée.”

67 Berger, “‘Global South’ as a Relational Category.”

68 Haug, “A Thirdspace Approach to the ‘Global South.’” Turkey, in particular, has had a complex position with regard to North–South framings; see Donelli and Gonzalez Levaggi, “Becoming Global Actor”; Haug, “Flamingo’s Neck.”

69 Tripathi, “International Relations and the ‘Global South.’”

70 Koch, “Cities as Transnational Climate Change Actors.”

71 Abdenur, “Climate and Security.”

72 Waisbich, Roychoudhury, and Haug, “Beyond the Single Story.”

73 On transnational economies, see Warnecke-Berger, “Dynamics of Global Asymmetries.”

74 For recent volumes that explicitly address (challenges connected to) the representation of voices from outside ‘Northern–Western’ academia in ‘Global South’-related research, see Salahub, Gottsbacher, and de Boer, Social Theories of Urban Violence; Mawdsley, Fourie, and Nauta, Researching South–South Development Cooperation; see also Salazar, “Transfers at a Crossroads.” Contributions in Braveboy-Wagner’s Diplomatic Strategies of Nations in the Global South are devoted to bringing ‘Southern’ voices to the mainstream, and the Global South Caucus of the International Studies Association was set up to provide a forum for dialogue on these issues.

75 See Gray and Gills, “South–South Cooperation and the Rise.” For contributions that explicitly engage with (sub)regional leading states in the ‘Global South’, see Braveboy-Wagner, Diplomatic Strategies of Nations in the Global South.

76 Prashad, Poorer Nations; and South Commission, Challenge to the South; see Gray and Gills, “South–South Cooperation and the Rise”; Mawdsley, “South–South Cooperation 3.0”; Fiddian-Qasmiyeh and Daley, Routledge Handbook of South–South Relations; Haug, “Mainstreaming South–South and Triangular Cooperation.”

77 On G20 rising powers, see Cooper, “G20 and Rising Powers.”

78 For a discussion with reference to recent shifts in international development, see Horner, “Towards a New Paradigm of Global Development.”

Bibliography

- Abdenur, Adriana. “Climate and Security: UN Agenda-Setting and the ‘Global South.’” Third World Quarterly (2021). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2021.1951609

- Acharya, Amitav. “Global International Relations (IR) and Regional Worlds: A New Agenda for International Studies.” International Studies Quarterly 58, no. 4 (2014): 647–659. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/isqu.12171.

- Acharya, Amitav. “An IR for the Global South or a Global IR?” Global South Review 2, no. 2 (2017): 175–178. doi:https://doi.org/10.22146/globalsouth.28874.

- Alden, Chris, Sally Morphet, and, and Marco Vieira. The South in World Politics. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

- Bailey, Kenneth. “Typologies and Taxonomies in Social Science.” In Typologies and Taxonomies, 1–16. London: SAGE, 1994.

- Barrowclough, Diana, Kevin Gallagher, and Richard Kozul-Wright, eds. Southern-Led Development Finance: Solutions from the Global South. London: Routledge, 2021.

- Baumann, Max-Otto. “Forever North–South? The Political Challenges of Reforming the UN Development System.” Third World Quarterly 39, no. 4 (2018): 626–641. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2017.1408405.

- Berger, Tobias. “The ‘Global South’ as a Relational Category: Global Hierarchies in the Production of Law and Legal Pluralism.” Third World Quarterly (2020): 1–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2020.1827948.

- Bieler, Andreas, and Jörg Nowak. “Labour Conflicts in the Global South: An Introduction.” Globalizations (2021). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2021.1884331.

- Boatcă, Manuela. “Unequal Institutions in the Longue Durée: Citizenship through a Southern Lens.” Third World Quarterly (2021): 1–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2021.1923398.

- Braveboy-Wagner, Jacqueline, ed. Diplomatic Strategies of Nations in the Global South: The Search for Leadership. New York, NY: Springer, 2016.

- Braveboy-Wagner, Jacqueline. “The Idea of the Global South: The Limits of the Material and the Need for Imagination.” Working Paper, 2018. 1–18. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325882933.

- Braveboy-Wagner, Jacqueline. Institutions of the Global South. London: Routledge, 2009.

- Brun, Élodie, Juliette Dumont, and Camille Forite. “Les relations Sud–Sud: culture et diplomatie.” Cahiers des Amériques latines 80 (2015): 15–29. doi:https://doi.org/10.4000/cal.4132.

- Comaroff, Jean, and John Comaroff. “Theory from the South: Or, How Euro-America Is Evolving toward Africa.” Anthropological Forum 22, no. 2 (2012): 113–131. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00664677.2012.694169.

- Connell, Raewyn. Southern Theory. Cambridge: Polity, 2007.

- Cooper, Andrew. “China, India and the Pattern of G20/BRICS Engagement: Differentiated Ambivalence between ‘Rising’ Power Status and Solidarity with the Global South.” Third World Quarterly (2020): 1–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2020.1829464.

- Cooper, Andrew. “The G20 and Rising Powers: An Innovative but Awkward Form of Multilateralism.” In Rising Powers and Multilateral Institutions, edited by D. Lesage and T. Van de Graaf, 280–294. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

- Cooper, Andrew, and Daniel Flemes. “Foreign Policy Strategies of Emerging Powers in a Multipolar World: An Introductory Review.” Third World Quarterly 34, no. 6 (2013): 943–962. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2013.802501.

- Dados, Nour, and Raewyn Connell. “The Global South.” Contexts 11, no. 1 (2012): 12–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1536504212436479.

- Dirlik, Arif. “Chinese History and the Question of Orientalism.” History and Theory 35, no. 4 (1996): 96–118. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2505446.

- Dirlik, Arif. “Global South: Predicament and Promise.” The Global South 1, no. 1 (2007): 12–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.2979/GSO.2007.1.1.12.

- Donelli, Federico, and Ariel Gonzalez Levaggi. “Becoming Global Actor: The Turkish Agenda for the Global South.” Rising Powers Quarterly 1, no. 2 (2016): 93–115.

- Duck, Leigh, ed. The Global South. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, n.d. https://iupress.org/journals/globalsouth/.

- Escobar, Arturo. Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011.

- Eyben, Rosalind, and Laura Savage. “Emerging and Submerging Powers: Imagined Geographies in the New Development Partnership at the Busan Fourth High Level Forum.” The Journal of Development Studies 49, no. 4 (2013): 457–469. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2012.733372.

- Ferguson, Niall. Civilisation: The West and the Rest. London: Allen Lane, 2011.

- Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, Elena, and Patricia Daley, eds. Routledge Handbook of South–South Relations. London: Routledge, 2019.

- Fuhr, Harald. “The Rise of the ‘South’ and the Rise in Carbon Emissions.” Third World Quarterly (2021). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2021.1954901

- Gosovic, Branislav. “The Resurgence of South–South Cooperation.” Third World Quarterly 37, no. 4 (2016): 733–743. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.1127155.

- Gray, Kevin, and Barry Gills. “South–South Cooperation and the Rise of the Global South.” Third World Quarterly 37, no. 4 (2016): 557–574. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.1128817.

- Grovogui, Siba. “A Revolution Nonetheless: The Global South in International Relations.” The Global South 5, no. 1 (2011): 175–190. doi:https://doi.org/10.2979/globalsouth.5.1.175.

- Harris, Nigel. “The End of the ‘Third World’?”Habitat International 11, no. 1 (1987): 119–132. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-3975(87)90042-7.

- Haug, Sebastian. “A Thirdspace Approach to the ‘Global South’: Insights from the Margins of a Popular Category.” Third World Quarterly (2020): 1–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2020.1712999.

- Haug, Sebastian. “The Flamingo’s Neck: Exploring Sustainable Development Realities in Turkey.” In Türkeiforschung im Deutschsprachigen Raum, edited by J. Chovanec, G. Cloeters, O. Inal, C. Joppien, and U. Woźniak, 93–115. New York: Springer, 2020.

- Haug, Sebastian. “Mainstreaming South–South and Triangular Cooperation: Work in Progress at the United Nations.” DIE Discussion Paper 15/2021, 2021. https://www.die-gdi.de/uploads/media/DP_15.2021.pdf

- Haug, Sebastian. “Thirding North/South: Mexico and Turkey in International Development Politics.” PhD diss., University of Cambridge, 2020.

- Hickel, Jason, Dylan Sullivan, and Huzaifa Zoomkawala. “Plunder in the Post-Colonial Era: Quantifying Drain from the Global South through Unequal Exchange, 1960–2018.” New Political Economy (2021): 1–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2021.1899153. See https://www.tandfonline.com/action/showCitFormats?doi=10.1080%2F13563467.2021.1899153&area=0000000000000001.

- Horner, Rory. “Towards a New Paradigm of Global Development? Beyond the Limits of International Development.” Progress in Human Geography 44, no. 3 (2020): 415–436. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519836158.

- Horner, Rory, and Pádraig Carmody. “Global North/South.” In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, edited by Audrey Kobayashi, 181–187. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2019.

- ICIDI [Independent Commission on International Development Issues]. North–South, a Programme for Survival: The Report of the Independent Commission on International Development Issues. London: Pan Books, 1980.

- Kantor, Roanne. “Booms in Literatures of the Global South.” Global South Studies: A Collective Publication with the Global South, 2018. https://globalsouthstudies.as.virginia.edu/key-issues/booms-literatures-global-south

- Kleinschmidt, Jochen. “Differentiation Theory and the Global South as a Metageography of International Relations.” Alternatives: Global, Local, Political 43, no. 2 (2018): 59–80. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0304375418811191.

- Koch, Florian. “Cities as Transnational Climate Change Actors: Applying a Global South Perspective.” Third World Quarterly (2020): 1–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2020.1789964.

- Kohlenberg, Paul, and Nadine Godehardt. “Locating the ‘South’ in China’sConnectivity Politics.” Third World Quarterly (2020): 1–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2020.1780909.

- Korany, Bahgat. “End of History, or Its Continuation and Accentuation? The Global South and the ‘New Transformation’ Literature.” Third World Quarterly 15, no. 1 (1994): 7–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436599408420360.

- Kornprobst, Markus, and Martin Senn. “Introduction: Background Ideas in International Relations.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 18, no. 2 (2016): 273–281. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148115613663.

- Kshetri, Nir. “Will Blockchain Emerge as a Tool to Break the Poverty Chain in the Global South?” Third World Quarterly 38, no. 8 (2017): 1710–1732. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2017.1298438.

- Levander, Caroline, and Walter Mignolo. “Introduction: The Global South and World Dis/Order.” The Global South 5, no. 1 (2011): 1–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.2979/globalsouth.5.1.1.

- Lewis, Martin, and Kären Wigen. The Myth of Continents: A Critique of Metageography. Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 1997.

- Mahbubani, Kishore. Has the West Lost It? A Provocation. London: Penguin Books, 2018.

- Mahler, Anne. From the Tricontinental to the Global South: Race, Radicalism, and Transnational Solidarity. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018.

- Mahler, Anne. “Global South.” In Bibliographies in Literary and Critical Theory, edited by Eugene O’Brien, 1–2. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2017.

- Mahler, Anne. “The Global South in the Belly of the Beast: Viewing African-American Civil Rights through a Tricontinental Lens.” Latin American Research Review 50, no. 1 (2015): 95–116. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/lar.2015.0007.

- Mahler, Anne. “What/Where Is the Global South?” 2017. https://globalsouthstudies.as.virginia.edu/what-is-global-south

- Maihold, Günther. “Mexico: A Leader in Search of Like-Minded Peers.” International Journal: Canada’s Journal of Global Policy Analysis 71, no. 4 (2016): 545–562. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0020702016687336.

- Mawdsley, Emma. “South–South Cooperation 3.0? Managing the Consequences of Success in the Decade Ahead.” Oxford Development Studies 47, no. 3 (2019): 259–274. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13600818.2019.1585792.

- Mawdsley, Emma, Elsje Fourie, and Wiebe Nauta, eds. Researching South–South Development Cooperation: The Politics of Knowledge Production. London: Routledge, 2019.

- Muchhala, Bhumika. “From New York to Addis Ababa: Financing for Development on Life Support.” Inter Press Service, July 10, 2015. http://www.ipsnews.net/2015/07/opinion-from-new-york-to-addis-ababa-financing-for-development-on-life-support-part-two/

- Nawyn, Stephanie, Nur Banu Kavakli, Tuba Demirci-Yılmaz, and Vanja Pantic Oflazoğlu. “Human Trafficking and Migration Management in the Global South.” International Journal of Sociology 46, no. 3 (2016): 189–204. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00207659.2016.1197724.

- OECD [Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development]. “Beyond Shifting Wealth.” 2017. https://www.oecd.org/publications/beyond-shifting-wealth-9789264273153-en.htm

- OECD [Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development]. “DAC List of ODA Recipients.” 2021. http://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-standards/daclist.htm

- Offutt, Stephen. “Evangelicals and Governance in the Global South.” The Review of Faith & International Affairs 18, no. 3 (2020): 76–86. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15570274.2020.1795415.

- PACHA. “About the Journal: PACHA. Revista de Estudios Contemporáneos del Sur Global.” 2020. http://revistapacha.religacion.com/index.php/about/about

- Pagel, Heike, Karen Ranke, Fabian Hempel, and Jonas Köhler. “The Use of the Concept ‘Global South’ in Social Science & Humanities.” Presentation. Berlin: Humboldt University, 2014.

- Prashad, Vijay. The Poorer Nations: A Possible History of the Global South. New York, NY: Verso, 2012.

- Quijano, Aníbal. “Coloniality and Modernity/Rationality.” Cultural Studies 21, no. 2–3 (2007): 168–178. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601164353.

- Rama, Jonas, and John Hall. “Raúl Prebisch and the Evolving Uses of ‘Centre–Periphery’ in Economic Analysis.” Review of Evolutionary Political Economy (2021). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s43253-021-00036-5. .

- Ramanzini Júnior, Haroldo, and Bruno Luciano. “Regionalism in the Global South: Mercosur and ECOWAS in Trade and Democracy Protection.” Third World Quarterly 41, no. 9 (2020): 1498–1517. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2020.1723413.

- Rigg, Jonathan. An Everyday Geography of the Global South. London: Routledge, 2007.

- Ryan, Caitlin. “To Do Better Research on the Global South We Must Start Failing Forward.” LSE Blogs. January 31, 2020. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/africaatlse/2020/01/31/better-research-fieldwork-global-south-start-failing-forward/

- Said, Edward. Orientalism: Western Concepts of the Orient. London: Penguin Books, 1995.

- Salahub, Jennifer, Markus Gottsbacher, and John de Boer, eds. Social Theories of Urban Violence in the Global South: Towards Safe and Inclusive Cities. London: Routledge, 2018.

- Salazar, Noel. “Transfers at a Crossroads: An Anthropological Perspective.” Transfers 10, no. 1 (2020): 66–73. doi:https://doi.org/10.3167/TRANS.2020.100108.

- Santos, Boaventura de Sousa. Conocer desde el Sur: Para una cultura política emancipatoria. Lima: National University of San Marcos, 2006.

- Schia, Niels Nagelhus. “The Cyber Frontier and Digital Pitfalls in the Global South.” Third World Quarterly 39, no. 5 (2018): 821–837. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2017.1408403.

- Schwarz, Tobias. “Global South … before I Learned How the Mainstream Uses It.”Concepts of the Global South, 2015, 11–12. https://kups.ub.uni-koeln.de/6399/1/voices012015_concepts_of_the_global_south.pdf

- Scopus. “Keyword Search.” 2021. https://www.scopus.com/home.uri

- Serajuddin, Umar, and Nada Hamadeh. “New World Bank Country Classifications by Income Level: 2020–2021.” 2020. https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/new-world-bank-country-classifications-income-level-2020-2021

- Shilliam, Robbie, ed. International Relations and Non-Western Thought: Imperialism, Colonialism and Investigations of Global Modernity. London: Routledge, 2011.

- Singh, Jewellord, and Jesse Ovadia. “The Theory and Practice of Building Developmental States in the Global South.” Third World Quarterly 39, no. 6 (2018): 1033–1055. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2018.1455143.

- South Commission. The Challenge to the South. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.

- Sparke, Matthew. “Everywhere but Always Somewhere: Critical Geographies of the Global South.” The Global South 1, no. 1 (2007): 117–126. doi:https://doi.org/10.2979/GSO.2007.1.1.117.

- Tickner, Arlene. “Core, Periphery and (Neo)Imperialist International Relations.” European Journal of International Relations 19, no. 3 (2013): 627–646. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066113494323.

- Tickner, Arlene, and Karen Smith. International Relations from the Global South: Worlds of Difference. London: Routledge, 2020.

- Toye, John. “Assessing the G77: 50 Years after UNCTAD and 40 Years after the NIEO.” Third World Quarterly 35, no. 10 (2014): 1759–1774. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2014.971589.

- Tricontinental. “About Tricontinental.” Tricontinental: The Institute for Social Research, 2021. https://thetricontinental.org/about/

- Tripathi, Siddharth. “International Relations and the ‘Global South’: From Epistemic Hierarchies to Dialogic Encounters.” Third World Quarterly (2021).

- UN [United Nations]. “Least Developed Countries.” New York, NY: United Nations, n.d. https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/least-developed-country-category.html

- UNCTAD [United Nations Conference on Trade and Development]. Forging a Path beyond Borders. Geneva: UNCTAD, 2018. https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/osg2018d1_en.pdf

- UNDP [United Nations Development Programme]. Human Development Index. New York, NY: UNDP, 2020. http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-index-hdi

- UNDP [United Nations Development Programme]. The Rise of the South. Human Development Report. New York, NY: UNDP, 2013.

- Wagner, Peter. The Moral Mappings of South and North. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2017.

- Waisbich, Laura Trajber, Supriya Roychoudhury, and Sebastian Haug. “Beyond the Single Story: ‘Global South’ Polyphonies.” Third World Quarterly (2021). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2021.1948832

- Wallerstein, Immanuel. World-Systems Analysis. An Introduction. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004.

- Warnecke-Berger, Hannes. “Dynamics of Global Asymmetries: How Migrant Remittances Shape North–South Relations.” Third World Quarterly (2021). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2021.1954501.

- Weiss, Thomas. “Moving beyond North–South Theatre.” Third World Quarterly 30, no. 2 (2009): 271–284. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436590802681033.

- Woertz, Eckart, ed. Reconfiguration of the Global South: Africa and Latin America and the “Asian Century.” London: Routledge, 2016.

- Wolvers, Andrea, Oliver Tappe, Tijo Salverda, and Tobias Schwarz. Concepts of the Global South – Voices from around the World. Cologne: Global South Studies Center, University of Cologne, 2015. https://kups.ub.uni-koeln.de/6399/1/voices012015_concepts_of_the_global_south.pdf

- Zarakol, Ayse. Before the West: The Rise and Fall of Eurasian World Orders. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, forthcoming.