Abstract

The international community is a key actor in fostering, establishing and maintaining peace in conflict-affected regions through multiple forms of cooperation. Official development assistance (ODA), for example, is one of them. It encompasses peacebuilding initiatives and includes diverse actors and partnerships. This paper provides a better understanding of such stakeholders’ relationships by analysing 85 successful peacebuilding ODA projects that donors have implemented in Colombia. Together with international donors, we examined the projects’ databases to classify the modality of cooperation, based on whether it focussed on development assistance, humanitarian aid or transition and on the way in which the key actors’ involvement varied, depending on the projects and modalities. We bridge multidisciplinary findings from peacebuilding and international cooperation literature in light of the Colombian case. Using empirical and theoretical evidence, we found that non-governmental organisations and civil society are key actors in most of the projects; and that, with Colombia holding a middle-income country (MIC) status, donors do not avoid cooperating with the government, as they do with low-income countries (LIC), which lack governmental capacities. The private sector was not recognised as a key actor by the donors, who question its role in international peacebuilding-oriented assistance.

Introduction

In recent decades, academics and practitioners’ interest in foreign aid, conflict resolution and peacebuilding has increased significantly. While some outcomes have focussed on peacebuilding interventions and the effectiveness of their planning and evaluation (Reychler and Paffenholz Citation2001; Anderson and Olson Citation2003; Paffenholz and Reychler Citation2007), others have conceptualised and analysed different stakeholders’ roles in peacebuilding (Lederach Citation1997; Ford Citation2015; Kolk and Lenfant Citation2015a, Citation2015b). A variety of international donors, including development agencies, governments, international non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and multilateral organisations, have included peacebuilding and conflict prevention in the development agenda (Paffenholz Citation2009). However, foreign aid for peacebuilding still faces major challenges, especially from a multi-stakeholder approach (Paffenholz Citation2015), and other authors have questioned which combination of stakeholders would be best to ensure social stability and conflict reduction (Westermann-Behaylo, Rehbein, and Fort Citation2015).

Because international cooperation (IC) embraces different concepts and definitions, we will focus on official development assistance (ODA), defined by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) as economic flows aimed at development goals and humanitarian aid (Global Humanitarian Aid Citation2018). The differences between cooperation modalities lie in their principles, scope and purpose, which will be analysed in greater detail in this article. In relation to peacebuilding and ODA, the Development Assistance Committee (DAC), part of the OECD, maintains that peace and security are key aspects to consider in channelling assistance and focussing on development strategies (OECD Citation2012a; Citation2018). Donors have made efforts to prioritise the provision of assistance to the increasing situations of global conflict, especially in fragile states (Findley Citation2018). Nevertheless, in 2016, according to an OECD report (2018), only 2% of ODA to fragile contexts went to conflict prevention, and 10% went to peacebuilding. Likewise, the humanitarian assistance modality increased by 144% between 2009 and 2016, as opposed to long-term development, which envisions peacebuilding actions (OECD Citation2018). This transpires as a consequence of the occurrence of emergencies in situations of conflict that prevent intervention, and of scenarios, such as those of post-conflict, that are aimed at development interventions and long-term peacebuilding. Related to this issue is the incompatibility between the humanitarian and development aid modalities, which has been a part of the research agenda and is one of the challenges donors face with respect to peacebuilding and IC paradigms (Otto and Weingärtner Citation2013).

By analysing the Colombian case in this article, our purpose is to provide a better understanding of what actors are present in ODA and which of them aim towards peacebuilding in each assistance modality. Three cooperation modalities were identified and used as part of the main analysis: (1) humanitarian, (2) development, and (3) transitional. Each assistance modality is guided by different motivations, and stakeholders’ engagement and partnership might also differ, as their procedures are ruled by different principles (Goodhand and Walton Citation2011). Hence, several questions about these differences and their dynamics remain unresolved or may not even have been formulated. Who are the stakeholders in each peacebuilding cooperation modality? Are stakeholders’ partnerships different in relief, development and transition projects? What particularities are there between key actors in IC and their relationships with a middle-income country (MIC) like Colombia?

Colombia has received a significant amount of ODA in the region, mostly to address the causes and consequences of the country’s 50-year internal armed conflict. As a particular case, its status as a MIC stands out, according to the classification of the World Bank, and it continues to receive financial support from donors. Colombia has received around 500 million dollars since 2000.Footnote1 However, the aid does not surpass the percentage point of its gross domestic product (GDP) (Agencia Presidencial de Cooperación de Colombia Citation2015), making it evident that there is no national budget dependence on foreign aid.

We address the questions presented above by characterising a data set that contains information on stakeholders’ engagement in 85 ODA peacebuilding projects, implemented in Colombia between 1995 and 2015. We asked the donors to classify their projects according to the type of modality and to highlight the key actors and partnerships in each project. This paper is divided into four sections. The first one frames the existing literature concerning IC in MICs, followed by a review of the link between humanitarian aid and development modalities and, finally, an overview of the stakeholders’ involvement in peacebuilding. The second section explains the research methodology and data classification. The third provides a brief historic panorama of Colombia’s armed conflict and ODA. The fourth section contains our findings and analysis of the modalities and their stakeholders’ partnerships through empirical and theoretical approaches. The fifth and final section presents conclusions, key considerations regarding future research, implications and threats to the validity of this study (eg Collier and Mahoney Citation1996).

Literature review

International cooperation in middle-income countries

The debate around the role of MICs in the IC system tends to be twofold. On the one hand, several developing countries are now described as MICs, as they have crossed the established income threshold of the World Bank’s classification systemFootnote2 (Alonso, Glennie, and Sumner Citation2014). In contrast to what happens to low-income countries (LICs) (Eyben and Ferguson Citation2004; Severino and Ray Citation2010), as MICs become richer, the role of IC plays a marginal role in their GDP; thus, under the assumption that MICs can finance their own development projects, the transfer of ODA is reconsidered and questioned (Constantine and Shankland Citation2017). Furthermore, some developing countries have emerged as potential donors among the MICs beyond economic flows, by exchanging resources, knowledge, technology and governance practices (Gray and Gills Citation2016).

Some scholars have noticed that the rise in MICs generates a global poverty problem, as most of the world’s poor live in countries that have gone from being LICs to MICs (Sumner Citation2010, Citation2011). In addition to poverty, ODA to MICs is also subject to problems related to situations of conflict, such as the Colombian armed conflict (Rohwerder Citation2016) and the Turkish refugee crisis due to the massive Syrian migration (Akgündüz, Van den Berg, and Hassink Citation2015). According to the Global Humanitarian Assistance Report (Global Humanitarian Aid Citation2018), in 2017, 70% of the world’s displaced population was located in MICs (Colombia ranked number two). As a result, the international community announced the diversification of cooperation tools, beyond the humanitarian response in conflict-affected regions and beyond their economic classification.

One of the most recognised challenges when channelling aid to MICs is related to the stakeholders’ interference, in particular with host country governmental institutions. In comparison with LICs, MICs already have a national response capacity, resources and greater institutional strengthening (Rohwerder Citation2016). In terms of humanitarian aid, for example, Ramalingam and Mitchell (Citation2014) defined two models of intervention, which focussed on MICs. The first is a complementary or collaborative model, where international response plays a supportive role in working together to enhance existing domestic capacities (Ramalingam and Mitchell Citation2014; Poole Citation2015). The second is conceived as a consultative model, mainly in MICs and high-income countries (HICs), where international humanitarian assistance might be requested to attend to a specific issue or niche (Ramalingam and Mitchell Citation2014). About other actors’ engagement, the scope of partnerships is wider in MICs, especially with local NGOs and civil society organisations (Crisp et al. Citation2009). Likewise, the private sector has been called on to become more involved with MICs, so as to cooperate and support long-term economic goals by making humanitarian response quicker and more effective (Alonso, Glennie, and Sumner Citation2014).

Official development assistance towards peacebuilding: humanitarian aid, development and transition

Among several development challenges, a key issue that IC has attempted to tackle is peacebuilding. Goodhand and Walton (Citation2011) highlight the internationalisation of post-Cold War peacebuilding as a consequence of the international community’s awareness. This led to conflict prevention and peacebuilding becoming relevant to international donors such as the United Nations, as shown in the Agenda for Peace report, written in 1992 (Boutros-Ghali Citation1992), and A Framework for World Bank Engagement in Post-Conflict Reconstruction, conceived by the World Bank in 1998 (Kreimer et al. Citation1998), among others.

Moreover, the debates on the modality of aid, in terms of IC, find impartialities and gaps when it comes to adequately classifying whether it is humanitarian aid or development assistance (Sollis Citation1994; OECD Citation2012a; Hinds Citation2015). Humanitarian aid has been defined as the action taken to attend a crisis by saving lives, alleviation of suffering, maintenance of human dignity, and building resilience at social and political levels (OCHA Citation2011). Development aid, on the other hand, responds to problems of a structural or systemic nature, such as poverty, which can be an impediment to full socioeconomic development (OECD Citation2018). However, attempts have been made to bridge the two modalities by designing other types of aid responses, focussing attention on countries in transition to peace- and state-building processes (Stoddard and Harmer Citation2005).

Activities to be implemented in the short term must be integrated with those implemented to reduce poverty or with those whose implementation period and achievements are tangible in the long term (Audet Citation2015). In academia, this need was addressed through a proposal to begin a continuum of aid action (Ross, Maxwell, and Buchanan-Smith Citation1994; Smillie Citation1998; Estermann Citation2014) involving the organisation of assistance to be distributed in stages, where, first, humanitarian workers attended life situations, followed by development actors who then entered to implement economic growth initiatives for conflict-affected populations. The lack of articulation justifies the need for an adequate union between these types of aid (development and peacebuilding). Richmond and Mitchell (Citation2011) argue that such a union should begin by sensitising the development actors to the conflict and extending this exercise to all levels where ODA is involved (local, regional and national levels), to generate greater awareness of the impact of the actions in each stage.Footnote3

Even today, no consensus has been reached on this discussion that establishes an effective union between ways of cooperating. Other conceptualisations, such as resilience, have been studied and proposed as an alternative way to address peacebuilding (Geneva Peacebuilding Platform Citation2015; Schilling et al. Citation2017; Juncos Citation2018), although its definition may be too holistic and not very coherent (De Coning Citation2016) – and because different stakeholders have tried to define it under diverse fields (Menkhaus Citation2013).

Other actors in international cooperation for peacebuilding

Peacebuilding is a complex process where different actors must be involved and shape different leadership positions (Lederach Citation1997; Reychler and Paffenholz Citation2001). Other authors have emphasised the need for actors to integrate organisational collaborative work at different levels, given the complexity of peacebuilding (Ricigliano Citation2003; De Coning Citation2009; Hofmann and Schneckener Citation2011). This includes the participation of government entities, international and local NGOs, multilateral and international organisations, local communities and the private sector, among others.

Local actors

More recently, the need to turn to local peacebuilding has led society to rethink the role of the international community in conflict intervention and peacebuilding (Donais Citation2009). Some authors argue the need for donors and external actors to identify the local-level dynamics, needs and desires, instead of favouring their own (De Coning Citation2013). Part of this criticism arises from the narrative and interpretation of the liberal peacebuilding concept, which promotes democratisation, marketisation and human rights from international actors and policies through a top-down implementation strategy (Leonardsson and Rudd Citation2015).

The relationship between civil society and peacebuilding has been studied thoroughly by Paffenholz and Spurk (Citation2010), who described seven functions of civil society in peacebuilding and designed a comprehensive analytical framework. Using these analytical tools, they structured a theoretical base to inquire about civil society’s peacebuilding activities in different contexts and phases of conflict (Paffenholz and Spurk Citation2010, 65).

The private sector

Multidisciplinary approaches emerged from diverse study fields in business management, unpacking the potential of business participation in peacebuilding (eg Kolk and Lenfant Citation2015a, Citation2015b; Abramov Citation2009; Oetzel et al. Citation2009). Scholars have directed their analyses to systems and processes, studying the relationships between business and society to acknowledge business actions in conflict (Miklian and Rettberg Citation2017). The first business intervention typologies in conflict resolution and peacebuilding were described and complemented among peace researchers (Fort and Schipani Citation2004; Fort Citation2009; Oetzel, Getz, and Ladek Citation2007). Others contributed with case studies, such as Katsos and Forrer (Citation2014), who documented successful business contributions during the Cyprus peacebuilding process. Jamali and Mirshak (Citation2010) have examined linkages between multinational corporations (MNCs)’ interventions in conflict contexts and corporate social responsibility (CSR). These contributions remain important; hence the call for businesses and the private sector itself to become more actively involved in peacebuilding processes (Ford Citation2015; Iff and Alluri Citation2016; Miklian and Rettberg Citation2017).

Kolk and Lenfant (Citation2013) studied partnership arrangements in fragile contexts affected by conflict. Among their findings, local business and non-profit organisations opted to collaborate with international firms and NGOs, and even with governmental donor agencies, but excluded the local state institutions (Kolk and Lenfant Citation2015b). In contrast, the business–government relationship in other contexts, such as Colombia, has been inclusive and collaborativeFootnote4 (Rettberg Citation2003, Citation2005; Miklian and Rettberg Citation2017). Colombian governmental efforts to integrate business in the peace agenda include the reintegration of ex-combatants and victims into the labour force, training programmes, and investment incentives in conflict-affected regions (Rettberg Citation2009; Duque and Fajardo Citation2019). From a more strategic and business theory perspective, Andonova and García (Citation2018) evaluated Colombian MNCs interventions in peacebuilding and how they enhance their competitiveness.

Methodology

In 2013, the group of donors in Colombia, under the leadership of the European Union and with the support of Uniandes, carried out a first effort to map international cooperation, with the aim of identifying the alignment of the cooperation projects with the Havana Peace negotiating points and the intention to seek a coordination to be able to support Colombia in what would be the implementation of a possible peace agreement.

After this effort, Uniandes helped the Colombian government, through the Post-Conflict Ministry and the Colombian Agency for International Cooperation, to identify, together with donors, successful cooperation projects that could be replicated for a rapid response stage, after signing the agreement. As a result, we identified 85 IC projects carried out in the country between 1995 and 2015, which were selected as a purposeful sample for the present study. By selecting successful projects (purposeful sampling), we were able to study information-rich cases to provide a better understanding of the phenomenon of interest (Palinkas et al. Citation2015), instead of generalising findings (Patton Citation2002, 230). A similar criterion of study was previously applied in the study of peacebuilding and stakeholder engagements (see Jamali and Mirshak Citation2010). The criteria defined for the research were useful for the replicability of the projects in the rapid response phase after signing the peace agreement and were considered successful due to their impact indicators (nine criteriaFootnote5 to determine whether or not a project has been successful). Likewise, we designed a survey to be completed by each of the donors and conducted in-depth elite interviews to complete the information and obtain more specific details of the projects. SixteenFootnote6 representatives were interviewed to complement the data with qualitative information. Thus, our research objective was to identify successful ODA projects through such elite interviews and consensus. According to Strauss and Corbin (Citation1990), these approaches are valuable when the research involves complex interactions, processes, beliefs and perceptions (Harvey Citation2011). Both purposeful sampling and elite interviews, later complemented with the survey-collected data, provided robustness to the project classification and dismissed the threat of possible selection bias.

For this research, and to begin with, our empirical results from this characterisation were analysed in the light of existing literature precepts, using a more qualitative approach by linking practical and theoretical evidence. These projects and their selection become an important and unique database that serves to look for findings on how IC has worked in a MIC like Colombia in the search for peace.

To fulfil the research goals, three main characteristics were identified for each project: (1) the cooperation modality to which the project corresponds; (2) the key actors that are involved in the project; and (3) the project’s thematic field. It is important to highlight that the modality and key actors–characteristics (1) and (2) were identified by donors during data collection. Each characteristic is theoretically supported as indicated in .

Table 1. Three main cooperation modalities.

Actors’ classification

Since 2004, the OECD has collected information on the type of aid delivery channels (Dietrich Citation2013). In the most general scheme, five channel categories are defined and classified into bilateral- and multilateral-type channels. The first one includes the public sector, non-governmental, public–private partnership and other (for-profit) actors. The multilateral aid channel only considers multilateral organisations (intergovernmental institutions) (OECD Citation2012b).

Our project does not focus exclusively on the delivery channel; it encompasses a wider set of key actors involved in project execution. According to the information contained in the database and the donors’ arguments for classification, we divided the actors into four main groups: (1) public-sector institutionsFootnote7; (2) NGOs and civil society;Footnote8 (3) the private sector; and (4) other donors.Footnote9

Classification of development fields

Since peacebuilding comprises so many fields of development, different sets of actors would be more or less engaged, depending on the type of peace initiative and the phase of the conflict. As such, we assigned a thematic development field to each project, according to the issue it dealt with. Three of these fields were identified in Leonhardt’s (Citation2000) framework of aid and peacebuilding cooperation: governance, economics and sociocultural factors (Leonhardt Citation2001, 240). These were considered development fields, instead of humanitarian aid initiatives, and were framed as relief.

Context of the ODA in Colombia

Fostering international cooperation for peace

The reception of IC in Colombia has been historically linked to three factors: (1) the ideological orientation of its leaders; (2) its diplomatic position; and (3) the over 50-year-long armed conflict (Bergamashi, García, and Santacruz Citation2017), the longest running armed conflict in the Western Hemisphere. The search for IC for armed conflict alleviation and actions towards peacebuilding dates back to the late 1990s, under the foreign policy of former President Andrés Pastrana’s Diplomacy for Peace, when the country increased its reception of 100 million dollars per year to 500 million on average, to date, under the figure of ODA (Bergamashi, García, and Santacruz Citation2017).

International cooperation between 2002 and 2010

In 2002, the country positioned Alvaro Uribe as the new president, who brought with him an agenda focussed on security and the fight against illegal armed groups by military means (Castañeda Citation2014). Uribe’s administration defined IC as the governmental political and economic support (García Citation2014), increasing donors’ connection with the presidential agency in charge of receiving cooperation, in an attempt to articulate the resources with government programmes, and centralising decisions. The Colombian International Cooperation Agency, formerly part of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, was attached to the Administrative Department of the Presidency and, later, in 2005, the Presidential Agency for Social Action was created.

International cooperation from 2010 to 2015: the path to the end of the conflict

In 2010, Juan Manuel Santos was elected president, and soon implemented an agenda very different from that of his predecessor. While Uribe prioritised the military dimension of internationalisation and limited foreign interference whenever a negotiated solution to the conflict was promoted, Santos’ strategy addressed IC as a tool for the success of an anticipated post-conflict scenario: the peace negotiations that began in 2012, in Havana, Cuba. With the change of command, in 2010, and the negotiations of the government of Juan Manuel Santos with the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia - Ejército del Pueblo (FARC-EP), the dialogue with donors shifted its orientation towards support for the negotiations, the peace process and the subsequent post-conflict period in Colombia.

Findings

Cooperation modalities

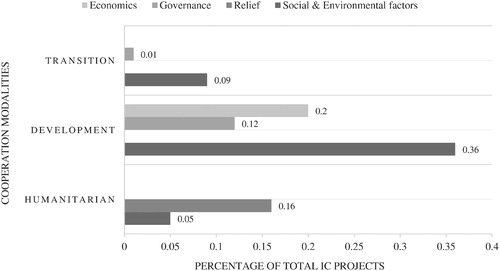

Among the three cooperation modalities, most of the projects – 68% of the total – were classified under development, followed by humanitarian and transitional aid, with 21% and 11%, respectively (see ). Not surprisingly, most of the cooperation has come under the development modality; we believe this is because of two important aspects. The first is that in the development modality, the characterisation comprised not only projects focussing on the economic dimension, but also included other fields, such as social development, political inclusion and environmental protection. Likewise, this modality encompasses projects that encouraged political participation, educational programmes, guarantee of human rights and economic development. These findings are related to the propositions laid out by Arreaza and Mason (Citation2012), who highlight the internationalisation of the Colombian peacebuilding process (the call for the external actors), which in turn brought other non-conventional fields of cooperation, such as gender, race, and social rights, corroborating that partnerships in development initiatives sought not only economic returns, but also fostered social capital (Elder, Zerriffi, and Le Billon Citation2012; Kolk and Lenfant Citation2015a). Second, important donors like the European Union and the United Nations Development Programme designed intervention strategies that sought to transform root causes of conflict, structuring development and socioeconomic initiatives.

Moreover, we found that humanitarian aid projects were focussed on relief efforts that provided healthcare and sanitation, and ensured food security in conflict-affected regions and urban areas. Such humanitarian assistance in a MIC like Colombia, at 21% in our study, has focussed on supplying basic needs and attending displacement issues, among others. The need for this type of modality in conflict-affected regions derives from the lack and weakness of the state institutions’ presence at different levels, which is also highlighted by Lemaitre (Citation2018).

The transition modality was covered in a lower proportion: 11% of the total sample. We argue that this modality was not frequently employed, based on the fact that the initiatives took place when the conflict was still latent and had not yet reached resolution, and because establishing transition initiatives in unstable socioeconomic and political environments is difficult, as this requires efforts from external actors to adapt and promote different rationales in edifying new social dynamics (Soto and Del Castillo, Citation2016). Nonetheless, the call for transitioning from humanitarian aid to development-focussed programmes in Colombia has been part of the discussion (Carrillo Citation2009), especially insofar as the internally displaced population is located in urban areas (Sandvik and Lemaitre Citation2013). Albuja and Ceballos (Citation2010) have highlighted the need for long-run development projects in cities where most of the displaced population has settled, instead of short-term humanitarian assistance. Given the low rate of transitioning projects and the importance of this cooperation modality in improving socioeconomic conditions, the private sector must design an adequate strategic involvement. Miklian and Rettberg (Citation2017, 21) identified the necessity to understand firms’ transition interventions in peacebuilding at different organisational levels of analysis. We add to that claim by arguing that, given the lack of the private sector’s involvement in transitioning peacebuilding programmes, joint development strategies with international cooperation dynamics should be explored.

Actors involved

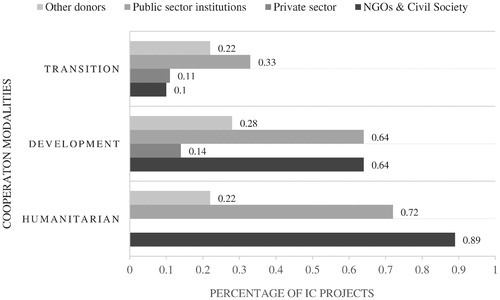

As for the stakeholders’ engagement, four main actors have been identified by the donors’ key partnerships in project execution. Although all of the actors interacted with each other at some level, shows the percentage of their participation in the total of projects for each modality. We found that participation by NGOs and civil society stands out, especially in humanitarian aid and transitional initiatives. NGOs and civil society encompass a broad set of actors, including international, national and local NGOs, grassroots organisations, and education and research institutions, as well as the Catholic Church. In the Colombian case, the NGOs and the church fulfilled multiple functions, such as intermediation in conflict and support to civil society, in situations where there was no presence of local or national government (Sanford Citation2003). This level of engagement and capacity to operate in conflict-affected regions gave the NGOs political and moral authority as well as recognition by the civil society and the state (Mason Citation2005). Their actions focussed on empowering the vulnerable population and providing them with the tools to create their sociopolitical identity, always framed within the principles of neutrality, negotiation and human rights (Arreaza and Mason Citation2012). The promotion of sociopolitical engagement has been recognised among humanitarian aid assistance projects in MICs, including in the Colombian case (see Lemaitre Citation2018). Nevertheless, initiatives that require high involvement with political settings must be aware of the so-called ‘institutionalization of peacebuilding’, which is more likely promoted by multilateral organisations and cooperation agencies (Mac Ginty Citation2013, 6).

Figure 2. Percentage of each actor’s involvement over the total projects by modality (eg NGOs and civil society were key actors in 89% of the total humanitarian aid projects).

Note: NGOs & CS: non-governmental organisations and civil society; PS: private sector; PSI: public sector institutions; OD: other donors.

Public-sector institutions were involved as key partners in most of the projects and modalities, especially in humanitarian aid and development projects, with 72% and 64% of the total, respectively (see ). The establishment of alliances with the state has two implications; first, it transmits a message of support to the national institutions and demonstrates commitment to the political solutions that it undertook to implement, echoing the words of Woodrow and Chigas (Citation2009). The danger of this joint work between donors and governments is the potential politicisation of aid (Volberg Citation2007) and its subsequent questioning by beneficiaries and international agencies. However, in contrast to fragile states and LICs, where local institutions and the rule of law are weak, Colombia is a MIC with relatively well-functioning state institutions (Wong Citation2008). Since 2003, the Colombian government has been working with donors on the International Cooperation Strategy, which focuses on national priorities, including those related to peacebuilding. Different strategic plans have been developed since, by means of a multi-stakeholder engagement, in which the government plays a fundamental role in formulating public policies, channelling ODA, executing and monitoring programmes.

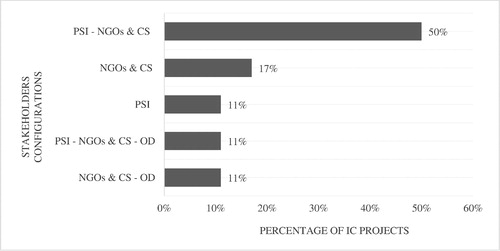

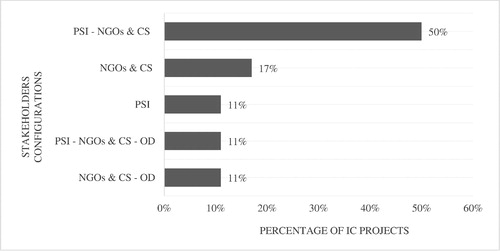

Government intervention has always been followed by the support, guidance and supervision of multiple international actors (Sanford Citation2003). Such close relationships between donors and the government in peacebuilding demonstrates the peculiarity of the Colombian case as a medium-high income country and recipient of ODA. Nonetheless, a lack of adequate coordination mechanisms between international and local actors has been identified. For instance, Buchelli and Gomez (Citation2007) attributed to this issue the absence of governmental leadership and the creation of alternative spaces for international actors’ involvement (McGee and García Heredia Citation2010). We also found a strong partnership between public-sector institutions and NGOs and civil society, as they were key partners in 50% of the total humanitarian aid projects (see ). Another important partnership was found among public-sector institutions, NGOs, civil society and other donors (11% – see ). Such findings on partnership support the idea that NGOs and local- and national-level governments are key partners in delivering aid when humanitarian aid response is required (Gavidia Citation2017).

Figure 3. Percentage of key actors’ partnerships over all humanitarian aid modality projects. Note: NGOs & CS: non-governmental organisations and civil society; PS: private sector; PSI: public sector institutions; OD: other donors.

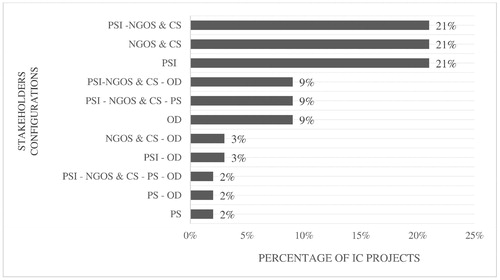

In a similar proportion, other donors’ partnership with NGOs and civil society accounted for 11% of the total humanitarian aid projects. A reason for such a partnership might be that the donors gain an advantage by working hand in hand with the NGOs and local communities, as they can support the intervention, impact and approach by providing valuable conflict context knowledge (Abozaglo Citation2009). This is strongly related to the findings exposed by Lemaitre (Citation2018) upon analysing the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) peacebuilding interventions in Colombia. The NRC experience emphasised the importance of a selective process when choosing partners among state institutions and international funders (Lemaitre Citation2018). Usually, donors and NGOs supported each other’s humanitarian aid interventions, especially when there was no state presence in conflict-affected regions or the institutional response was not efficient (eg Lederach Citation2019). As for development modality projects, the key actors’ partnerships were very similar to those of the humanitarian aid case, as the public-sector institutions’ partnership with NGOs and civil society was the most prevalent, accounting for 21% of the total number of development projects (see ). Similarly, NGO and civil society partnerships accounted for 21% of the projects, and public-sector institutions, also without partners, accounted for the same percentage (see ). It is not surprising that government actors, NGOs and civil society are the main stakeholders in this modality. A closer look at the thematic areas on which the development projects focussed shows that the factors mostly addressed were social and environmental and related to governance issues (see ), representing 48% of all projects. Meanwhile, 20% of the total focussed on economic development. In line with their partnership and high levels of participation, the government, NGOs and locals play a key role in these development fields (see and ).

Figure 4. Percentage of key actors’ partnerships over all development assistance modality projects. Note: NGOs & CS: non-governmental organisations and civil society; PS: private sector; PSI: public sector institutions; OD: other donors.

Figure 5. Percentage of thematic fields by modality, over the total sample (eg 9% out of the total projects corresponded to social and environmental factors in the transitional modality).

Nonetheless, we believe that the private sector’s involvement was relatively low. To successfully engage the private sector in peacebuilding development initiatives, governments need to understand the firms’ opportunities, obstacles and concerns of engagement. In this way, economic development can also support political processes (see Bray Citation2009). In Colombia, the private sector has played an active and participatory role, from the involvement in negotiation agendas between the guerrillas and the government to local development plans in conflict-affected regions (Rettberg and Rivas 2012). According to the donors interviewed, the private sector was a key partner in the development and transitional modalities. However, the percentage shows little involvement, engaged in 14% of the development initiatives and 11% of the total, classified as humanitarian (see ). Yet the private sector’s key role in humanitarian aid and relief actions was not highlighted, which raises a question about the effectiveness of the aid, its response, and why it was not considered under the multi-stakeholder approach. We already explored how actors such as the state played a fundamental role in assisting humanitarian aid, beyond creating a favourable environment for the supply of aid. However, it remains unclear why the private sector was not fully engaged, and why the key actor value was not attributed. One possible cause may be the lack of interaction between organisations dealing with humanitarian situations and the private sector (Rettberg Citation2016).

In the development modality, the private sector proved to play a more active role, especially when partnering with public-sector institutions, NGOs and civil society (see ). The importance of these actors’ joint work lies in the efforts made to complement each other’s actions and knowledge-sharing process. One of the greatest efforts to be made in this case is that the government, the NGOs and the donors should understand the businesses’ operational and financial limitations (Rettberg and Rivas Citation2012), as well as the risks and opportunities of contributing to peacebuilding (Ford Citation2015, 339). For instance, there is still little knowledge about how policy initiatives may stimulate (or not) the private sector’s involvement in peacebuilding (Ford Citation2015). Echoing such claims, future empirical and qualitative research may provide valuable insights for practitioners and policymakers. For example, García and Barrios (2019) explored firms’ strategies in hiring ex-combatants in Colombia by working under governmental guidance and reintegration initiatives. For businesses, the support of other actors must include the recognition of the firms’ interests, size and capacities, as well as the sector and geographic locations in which they operate (Schneider Citation2004). Likewise, companies must identify the social dynamics at work in the peacebuilding context in which they participate by being aware of the different intervention dynamics, in order to co-create value with other intervention actors. This means changing the way in which business as usual is carried out (Jamali and Mirshak Citation2010).

Conclusions and further discussion

Upon analysing the IC modalities for peacebuilding, we found that it was very important for most projects to go through the development modality because peacebuilding projects, while they may have some humanitarian responses, should be considered in the longer term. However, there is no formula to effectively determine which cooperation modality is more important or what kind of balance there may be between them. Donors may use one instead of the other depending on the given context and/or result of the strategic analysis of the conflict. Likewise, based on the results of the characterisation, we found that development not only comprised economic actions, but also included other valuable fields, such as social and environmental aspects, including human rights, political participation and empowerment, gender issues and education. The most important contributions that we derive from the Colombian case and the present study are those regarding cooperation modalities, thematic fields and key actors’ partnerships. The Colombian case shows the relevance of articulating various actors in peacebuilding. In a political sense, it is important for the governments of countries in conflict or transition to call on the international community to cooperate through development and peacebuilding narratives and projects. International organisations must be called upon to become agents of complementarity in the processes of stabilisation and to support local improvements by providing resources, among other things, in accordance with the priorities defined by the local government. Consequently, strategic peacebuilding integrates within its policies and practices both national and international processes as they overlap and are interdependent (Chesterman Citation2010, 137).

As for the actors, we highlight the significant participation of public-sector institutions in all cooperation modalities. This, on the one hand, demonstrates and confirms that, in states with relatively strong, legitimate and solid institutions, there may be positive state intervention that also serves as a bridge between donors and beneficiaries. In Colombia, the state has also established agreements to co-finance initiatives together with other donors, such as the Peace Laboratories of the European Union (see Castañeda Citation2012). The opposite happens in LICs, where correctness and transparency in allocating the funds is more at risk than in MICs due to their cooperation with public-sector institutions, including the politicisation of the aid, which is also seen as a threat (Kanbur and Sumner Citation2012). The latter is especially preventable in humanitarian aid because of the principles it professes to follow (Volberg Citation2007). Also noteworthy is the involvement of NGOs and civil society, which shows a high level of participation of key local entities that have been involved in project implementation. Such participation strengthens relationships with other actors, such as other donors and the state, creating collaborative partnerships following complementary top-down and bottom-up strategies (Paffenholz Citation2015).

We were surprised by the fact that the private sector was not one of the key actors in the projects. This raises new questions concerning what motivates these organisations to cooperate (or not) in peacebuilding, particularly in projects with international intervention. We propose, however, that all partnerships should be subject to effectiveness evaluations according to the particular context. In this regard, future research could examine the causal interest and motivations that lead to these partnerships and whether certain patterns lie behind the dynamics of the conflict and its stage in the transition to peace.

A database of 85 projects carried out over time shows how donors have worked on peacebuilding in a MIC. Despite certain limitations (described below), this study is a good starting point for understanding the role and scope of IC in peacebuilding. Indeed, the ideas and approaches laid out in this paper have a set of limitations that should be contemplated in future studies pursuing replicability. Firstly, the identification of patterns of success applied to the selection of the projects was conducted according to the criteria established by the Universidad de los Andes research team and the government. Thus, projects without the desired characteristics were not taken into account. This suggests that other comparative studies may be designed on the basis of different data set configurations, so as to analyse either the actors and partnerships or other factors that might influence the dynamics and modalities of IC and ODA. Secondly, the main sources of information about the projects and the interviews came from donors. Hence, the arguments and discussions were not corroborated or refuted by other important actors who may have participated in the projects as beneficiaries. Thirdly, this was a cross-sectional study, since the sample included projects carried out over a 20-year period, without a time series analysis that could sort out the existence of causal effects and interactions across time. Therefore, quantitative studies could be conducted to identify other types of approaches and conclusions that may complement those here described.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the support and cooperation of the Ministry of Post-conflict of the Colombian government, the Colombian Cooperation Agency and the interviewed donors, as their knowledge and the information provided were crucial in the creation of this paper. Likewise, we are grateful to Dr Isaline Bergamashi and the research assistants Paola Godoy and Juan D. Martínez, for their valuable contributions and collaboration in the data collection process to make the final report, ‘Sin el corto plazo, no hay largo plazo’ / Identification of International Cooperation Actions for the post-conflict in 2017.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Juana García Duque

Juana García Duque is Associate Professor at the Business School from Universidad de los Andes, Colombia, and a Visiting Scholar at DRCLAS, David Rockefeller Centre for Latin American Studies at Harvard. Her research activity in international development includes: (1) the role of international cooperation and the private sector in peacebuilding processes, and the study of (2) internationalisation and emerging economies. She is part of the Academic Committee of the MA degree in peacebuilding, and coordinates several of the projects of the university regarding peace. She is a member of the Microeconomics of Competitiveness (MOC) led by Professor Michael Porter at the Institute for Strategy and Competitiveness at Harvard and of the EMRN Emerging Markets Research Network.

Juan Pablo Casadiego

Juan Pablo Casadiego is a PhD candidate in sustainable management at ESADE Business School. The focus of his doctoral research is on regenerative business models and sustainable entrepreneurship. His research interest also encompasses development studies, international cooperation and peacebuilding. He has been Research Assistant at the School of Management of Universidad de los Andes, the Sustainable Development Solutions Network and the Emerging Markets Institute at Cornell University.

Notes

1 In 2015, it received the largest allocation of ODA in its history, reaching $511 million. See Agencia Presidencial de Cooperación de Colombia (Citation2015).

2 As of July 2018, the World Bank updated the world’s economies classification into four income groups, according to their GNI per capita. The new thresholds are (values in current US dollars): low income (<=1,025), lower-middle income (1,026-3,995), upper-middle income (3896–12,055), high-income (>=12,376) (Beer Prydz and Wadhwa Citation2019).

3 Following the model outlined by Dugan (Citation1996) and Lederach Citation1997.

4 According to the World Bank (Citation2019), Colombia holds an upper-middle-income country status, also known as a MIC.

5 The parameters are: alignment; feasibility; high impact and satisfaction of strategic economic, social and cultural rights (ESCR); sensitivity to social conflict; protection of and increase in security; symbolic and psychosocial alleviation. The La Agencia Presidencial de Cooperación Internacional de Colombia, APC-Colombia added implementation time.

6 The interviewed donors were: United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Office of Humanitarian Aid of the European Union (ECHO), Delegation of the European Union in Colombia (EU), Spanish Agency for International Development Cooperation (AECID), Embassy of Switzerland, Embassy of Sweden, Embassy of Canada, Embassy of Germany, Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA), Embassy of the Netherlands, Embassy of Norway, International Organization for Migration (IOM), Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), and United Nations Development Programme (UNDP).

7 In this category, public institutions include local and national government and other institutions that are part of the central government.

8 The Creditor Reporting System (CRS) is a mechanism for sharing development flow information, statistics and analyses. It recognises ODA channeled through NGOs and civil society (OECD Citation2018).

9 ‘Other donors’ includes those donors who participated in other projects, including multilateral and bilateral cooperation agencies, and embassies.

Bibliography

- Abozaglo, P. 2009. “The Role of NGOs in Peacebuilding in Colombia.” Research and Perspectives on Development Practice : 9. https://mural.maynoothuniversity.ie/9959/

- Abramov, I. 2009. “Building Peace in Fragile States – Building Trust is Essential for Effective Public–Private Partnerships.” Journal of Business Ethics 89 (S4): 481–494. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0402-8.

- Agencia Presidencial de Cooperación de Colombia. 2015. Informe de gestión APC-Colombia 2015 [Report]. https://www.apccolombia.gov.co/sites/default/files/archivos_usuario/2016/07/informe-de-gestion-apc-colombia-2015_0.pdf

- Akgündüz, Y., M. Van den Berg, and W. H. Hassink. 2015. The impact of Refugee Crises on Host Labor Markets: The Case of the Syrian Refugee Crisis in Turkey (IZA Discussion Paper No: 8841). IZA - Institute of Labor Economics. http://repec.iza.org/dp8841.pdf

- Albuja, S., and M. Ceballos. 2010. Urban displacement and migration in colombia. Forced Migration Review, 34: 10–11.

- Alonso, J. A., J. Glennie, and A. Sumner. 2014. Recipients and Contributors: Middle Income Countries and the Future of Development Cooperation (DESA Working Paper No. 135). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. https://www.un.org/esa/desa/papers/2014/wp135_2014.pdf

- Anderson, M. B., and L. Olson. 2003. Confronting War: Critical Lessons for Peace Practitioners. The Collaborative for Development Action. CDA Collaborative Learning Projects. https://www.cdacollaborative.org/publication/confronting-war-critical-lessons-for-peace-practitioners/

- Andonova, V., and J. García. 2018. “How Can EMNCs Enhance Their Global Competitive Advantage by Engaging in Domestic Peacebuilding? The Case of Colombia.” Transnational Corporations Review 10 (4): 370–385. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19186444.2018.1556520.

- Arreaza, C., and A. Mason. 2012. “Los actores internacionales y la construcción de paz en Colombia.” In Construcción de paz en Colombia, edited by A. Rettburg, 463–491. Bogotá, Colombia: Ediciones Uniandes. doi:https://doi.org/10.7440/2012.23.

- Audet, F. 2015. “From Disaster Relief to Development Assistance: Why Simple Solutions Don’t Work.” International Journal: Canada’s Journal of Global Policy Analysis 70 (1): 110–118. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0020702014562595.

- Beer Prydz, E., and D. Wadhwa. 2019. Classifying Countries by Income. The World Bank. https://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/stories/the-classification-of-countries-by-income.html

- Bergamashi, I., J. García, and C. Santacruz. 2017. “Colombia como oferente y receptor de cooperación internacional: apropiación, liderazgo y dualidad.” In Nuevos enfoques Para el estudio de las relaciones internacionales de Colombia, edited by A. B. Tickner and S. Bitar, 331–360. Bogotá, Colombia: Ediciones Uniandes.

- Boutros-Ghali, B. 1992. “An Agenda for Peace: Preventive Diplomacy, Peacemaking and Peace-Keeping.” International Relations 11 (3): 201–218. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/004711789201100302.

- Bray, J. 2009. “The Role of Private Sector Actors in Post-Conflict Recovery.” Analysis. Conflict, Security & Development 9 (1): 1–26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14678800802704895.

- Buchelli, Juan Fernando, and Gomez Viviana. 2007. ‘Aid Coordination in Colombia: Approach, Routes and Effective Leadership: Analysis of the consequences for Colombia’s aid policy of adherence to the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness’. Unpublished Working Paper, May.

- Carrillo, A. C. 2009. “Internal Displacement in Colombia: Humanitarian, Economic and Social Consequences in Urban Settings and Current Challenges.” International Review of the Red Cross 91 (875): 527–546. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1816383109990427.

- Castañeda, D. 2012. The European Union in Colombia: Learning How to Be a Peace Actor (Paris Papers 3/2012). L’Institut de Recherche Stratégique de l’École Militaire. https://www.defense.gouv.fr/content/download/158084/1625311/file/Paris%20Paper%20n%C2%B03.pdf

- Castañeda, D. 2014. The European Approach to Peacebuilding: Civilian Tools for Peace in Colombia and Beyond. Washington DC.: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137357311.

- Chesterman, S. 2010. “Whose Strategy, Whose Peace? The Role of International Institutions in Strategic Peacebuilding.” In Strategies of Peace, edited by D. Philpott and G. Powers, 119–140. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Collier, D., and J. Mahoney. 1996. “Insights and Pitfalls: Selection Bias in Qualitative Research.” World Politics 49 (1): 56–91. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/wp.1996.0023.

- Constantine, J. and A. Shankland. 2017. “From Policy Transfer to Mutual Learning? Political Recognition, Power and Process in the Emerging Landscape of International Development Cooperation.” Novos Estudos - CEBRAP 36 (01): 99–122. doi:https://doi.org/10.25091/S0101-3300201700010005.

- Crisp, J., J. Janz, J. Riera, and S. Samy. 2009. Surviving in the City: A Review of UNHCR’s Operation for Iraqi Refugees in Urban Areas of Jordan, Lebanon and Syria [Report]. UNHCR. https://www.unhcr.org/research/evalreports/4a69ad639/surviving-city-review-unhcrs-operation-iraqi-refugees-urban-areas-jordan.html

- De Coning, C. 2009. “The Coherence Dilemma in Peacebuilding and Post-Conflict Reconstruction Systems.” African Journal on Conflict Resolution 8 (3): 85–110. doi:https://doi.org/10.4314/ajcr.v8i3.39432.

- De Coning, C. 2013. “Understanding Peacebuilding as Essentially Local.” Stability: International Journal of Security and Development 2 (1): 6–6. doi:https://doi.org/10.5334/sta.as.

- De Coning, C. 2016. “From Peacebuilding to Sustaining Peace: Implications of Complexity for Resilience and Sustainability.” Resilience 4 (3): 166–181. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21693293.2016.1153773.

- De Soto, A., and G. Del Castillo. 2016. “Obstacles to Peacebuilding Revisited.” Global Governance 22 (2): 209–227. doi:https://doi.org/10.1163/19426720-02202003.

- Dietrich, S. 2013. “Bypass or Engage? Explaining Donor Delivery Tactics in Foreign Aid Allocation.” International Studies Quarterly 57 (4): 698–712. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/isqu.12041.

- Donais, T. 2009. “Empowerment or Imposition? Dilemmas of Local Ownership in Post-Conflict Peacebuilding Processes.” Peace & Change 34 (1): 3–26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0130.2009.00531.x.

- Dugan, M. 1996. “A Nested Theory of Conflict.” Women in Leadership 1 (1): 9–20. https://emu.edu/cjp/docs/Dugan_Maire_Nested-Model-Original.pdf.

- Duque, J., and A. Fajardo. (Eds.). 2019. Construcción de paz: Las empresas en la reintegración de excombatientes. Bogotá, D. C., Colombia: Universidad de los Andes, Colombia. Retrieved August 11, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7440/j.ctv14t47gf

- Elder, S. D., H. Zerriffi, and P. Le Billon. 2012. “Effects of Fair Trade Certification on Social Capital: The Case of Rwandan Coffee Producers.” World Development 40 (11): 2355–2367. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.06.010.

- Estermann, J. 2014. Towards a Convergence of Humanitarian and Development Assistance through Cash Transfers to Host Communities (CERAH Working Paper 22). CERAH Genève. https://www.cerahgeneve.ch/files/8514/6622/7068/WP22-convergance-humanitarian-development-assistance.pdf

- Eyben, R., and C. Ferguson. 2004. “How Can Donors Become More Accountable to Poor People?.” In Inclusive Aid: Changing Power and Relationships in International Development, edited by L. Groves and R. Hinton, 57–75. Washington DC.: Earthscan.

- Findley, M. G. 2018. “Does Foreign Aid Build Peace?” Annual Review of Political Science 21 (1): 359–384. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-041916-015516.

- Ford, J. 2015. “Perspectives on the Evolving “Business and Peace” Debate.” Academy of Management Perspectives 29 (4): 451–460. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2015.0142.

- Fort, T. L. 2009. “Peace through Commerce: A Multisectoral Approach.” Journal of Business Ethics 89 (S4): 347–350. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0413-5.

- Fort, T. L., and C. A. Schipani. 2004. The Role of Business in Fostering Peaceful Societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- García, J. 2014. “Análisis Comparado de Las Agendas de Cooperación y Ayuda al Desarrollo en Colombia: Diferencias Entre Los Modelos de Estados Unidos y la Unión Europea 1998–2006.” PhD thesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid. https://eprints.ucm.es/25086/1/T35307.pdf.

- Gavidia, J. V. 2017. “A Model for Enterprise Resource Planning in Emergency Humanitarian Logistics.” Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management 7 (3): 246–265. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/JHLSCM-02-2017-0004.

- Geneva Peacebuilding Platform. 2015. White Paper on Peacebuilding. Geneva Peacebuilding Platform. https://www.gpplatform.ch/sites/default/files/White%20Paper%20on%20Peacebuilding.pdf

- Global Humanitarian Aid. 2018. Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2018. Development Initiatives. http://devinit.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/GHA-Report-2018.pdf

- Goodhand, J., and O. Walton. 2012. Public versus private power: non-governmental organisations and international security. In Routledge Handbook of Diplomacy and Statecraft, (pp. 462–474). Abingdon. Routledge.

- Gray, K., and B. K. Gills. 2016. “South–South Cooperation and the Rise of the Global South.” Third World Quarterly 37 (4): 557–574. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.1128817.

- Harvey, W. S. 2011. “Strategies for Conducting Elite Interviews.” Qualitative Research 11 (4): 431–441. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794111404329.

- Hinds, R. 2015. Relationship between Humanitarian and Development Aid (GSDRC Helpdesk Research Report 1185). Governance and Social Development Resource Centre. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/HDQ1185.pdf

- Hofmann, C., and U. Schneckener. 2011. “Engaging Non-State Armed Actors in State-and Peace-Building: Options and Strategies.” International Review of the Red Cross 93 (883): 603–621. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1816383112000148.

- Iff, A., and R. M. Alluri. 2016. “Business Actors in Peace Mediation Processes.” Business and Society Review 121 (2): 187–215. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/basr.12085.

- Jamali, D., and R. Mirshak. 2010. “Business-Conflict Linkages: Revisiting MNCs, CSR, and Conflict.” Journal of Business Ethics 93 (3): 443–464. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0232-8.

- Juncos, A. E. 2018. “Resilience in Peacebuilding: Contesting Uncertainty, Ambiguity, and Complexity.” Contemporary Security Policy 39 (4): 559–574. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2018.1491742.

- Kanbur, R., and A. Sumner. 2012. “Poor Countries or Poor People? Development Assistance and the New Geography of Global Poverty.” Journal of International Development 24 (6): 686–695. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.2861.

- Katsos, J. E., and J. Forrer. 2014. “Business Practices and Peace in Post-Conflict Zones: Lessons from Cyprus.” Business Ethics: A European Review 23 (2): 154–168. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12044.

- Kolk, A., and F. Lenfant. 2013. “Multinationals, CSR and Partnerships in Central African Conflict Countries.” Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 20 (1): 43–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1277.

- Kolk, A., and F. Lenfant. 2015a. “Cross-Sector Collaboration, Institutional Gaps, and Fragility: The Role of Social Innovation Partnerships in a Conflict-Affected Region.” Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 34 (2): 287–303. doi:https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.14.157.

- Kolk, A., and F. Lenfant. 2015b. “Partnerships for Peace and Development in Fragile States: Identifying Missing Links.” Academy of Management Perspectives 29 (4): 422–437. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2013.0122.

- Kreimer, A., J. Eriksson, R. Muscat, M. Arnold, and C. Scott. 1998. The World Bank’s Experience with Post-Conflict Reconstruction. The World Bank. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/666021468766536253/The-World-Banks-experience-with-post-conflict-reconstruction

- Lederach, J. 1997. Building Peace: Sustainable Reconciliation in Divided Societies. Washington DC: United States Institute of Peace Press.

- Lederach, A. J. 2019. ““Feel the Grass Grow”: The Practices and Politics of Slow Peace in Colombia.” Doctoral diss., University of Notre Dame.

- Lemaitre, J. 2018. “Humanitarian Aid and Host State Capacity: The Challenges of the Norwegian Refugee Council in Colombia.” Third World Quarterly 39 (3): 544–559. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2017.1368381.

- Leonardsson, H., and G. Rudd. 2015. “The ‘Local Turn’ in Peacebuilding: A Literature Review of Effective and Emancipatory Local Peacebuilding.” Third World Quarterly 36 (5): 825–839. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.1029905.

- Leonhardt, M. 2000. Conflict Impact Assessment of EU Development Co-Operation with ACP Countries: A Review of Literature and Practice. The Hague, Netherlands: International Alert.

- Leonhardt, M. 2001. “The Challenge of Linking Aid and Peacebuilding.” In Peacebuilding: A Field Guide, edited by L. Reychler and T. Paffenholz, 240–245. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

- Mac Ginty, R. (Ed.). 2013. Routledge handbook of peacebuilding. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Mason, A. C. 2005. “Constructing Authority Alternatives on the Periphery: Vignettes from Colombia.” International Political Science Review 26 (1): 37–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512105047895.

- McGee, R., and I. García Heredia. 2010. “Paris in Bogota: Applying the Aid Effectiveness Agenda in Colombia.” IDS Working Papers 2010 (342): 1–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2040-0209.2010.00342_2.x.

- Menkhaus, K. 2013. Making Sense of Resilience in Peacebuilding Contexts: Approaches, Applications, Implications (Paper No.6). Geneva Peacebuilding Platform. https://www.gpplatform.ch/sites/default/files/PP%2006%20-%20Resilience%20to%20Transformation%20-%20Jan.%202013_2.pdf

- Miklian, J., and A. Rettberg. 2017. “From War-Torn to Peace-Torn? Mapping Business Strategies in Transition from Conflict to Peace in Colombia.” In Mapping Business Strategies in Transition from Conflict to Peace in Colombia, edited by J. Miklian, R. M. Alluri, and J. E. Katsos, 110–128. London: Routledge. doi:https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2925244.

- Oetzel, J., K. A. Getz, and S. Ladek. 2007. “The Role of Multinational Enterprises in Responding to Violent Conflict: A Conceptual Model and Framework for Research.” American Business Law Journal 44 (2): 331–358. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-1714.2007.00039.x.

- Oetzel, J., M. Westermann-Behaylo, C. Koerber, T. L. Fort, and J. Rivera. 2009. “Business and Peace: Sketching the Terrain.” Journal of Business Ethics 89 (S4): 351–373. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0411-7.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2010. International Support to Statebuilding in Situations of Fragility and Conflict (DCD/DAC(2010)37). OECD. http://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=DCD/DAC%282010%2937&docLanguage=En

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2012a. International Support to Post-Conflict Transition: Rethinking Policy, Changing Practice. OECD. doi:https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264168336-en.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2012b. Partnering with Civil Society: 12 Lessons from DAC Peer Reviews. OECD. https://www.oecd.org/dac/peer-reviews/12%20Lessons%20Partnering%20with%20Civil%20Society.pdf

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2018. Development Co-operation Report: Joining Forces to Leave No One Behind. OECD. doi:https://doi.org/10.1787/dcr-2018-en.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2019. What Is ODA? OECD. http://www.oecd.org/dac/stats/What-is-ODA.pdf

- Otto, R., and L. Weingärtner. 2013. Linking Relief and Development: More than Old Solutions for Old Problems (IOB Study, 380). Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands. https://www.government.nl/documents/reports/2013/05/01/iob-study-linking-relief-and-development-more-than-old-solutions-for-old-problems

- Paffenholz, T. 2009. Civil Society and Peacebuilding (CCDP Working Paper No. 4). The Centre on Conflict, Development and Peacebuilding. https://www.sfcg.org/events/pdf/CCDP_Working_Paper_4-1%20a.pdf

- Paffenholz, T. 2015. “Unpacking the Local Turn in Peacebuilding: A Critical Assessment towards an Agenda for Future Research.” Third World Quarterly 36 (5): 857–874. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.1029908.

- Paffenholz, T., and L. Reychler. 2007. Aid for Peace: A Guide to Planning and Evaluation for Conflict Zones. Baden-Baden, Germany: Nomos.

- Paffenholz, T., and C. Spurk. 2010. “A Comprehensive Analytical Framework.” In Civil Society and Peacebuilding: A Critical Assessment, edited by T. Paffenholz, 65–76. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

- Palinkas, L. A., S. M. Horwitz, C. A. Green, J. P. Wisdom, N. Duan, and K. Hoagwood. 2015. “Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research.” Administration and Policy in Mental Health 42 (5): 533–544. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y.

- Patton, M. Q. 2002. Qualitative Researchandevaluation Methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

- Poole, L. 2015. Looking Beyond the Crisis [Report]. Future Humanitarian Financing Initiative: CAFOD, FAO, World Vision. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/FHF_Main_Report%20%282%29.pdf

- Ramalingam, B., and J. Mitchell. 2014. Responding to Changing Needs? Challenges and Opportunities for Humanitarian Agencies. Montreux XIII Meeting Paper. Active Learning Network for Accountability and Performance in Humanitarian Action (ALNAP). https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/alnap-responding-to-changing-needs-montreux-xiii-paper.pdf

- Rettberg, A. 2003. Cacaos y tigres de papel: el gobierno de Samper y los empresarios colombianos. Bogotá, Colombia: Ediciones Uniandes.

- Rettberg, A. 2005. “Business versus Business? Grupos and Business Associations in Colombia.” Latin American Politics and Society 47 (1): 31–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-2456.2005.tb00300.x.

- Rettberg, A. 2009. “Business and Peace in Colombia: Responses, Challenges, and Achievements.” In Colombia: Building Peace in a Time of War, edited by V. M. Bouvier, 191–204. Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace.

- Rettberg, A. 2016. “Need, Creed, and Greed: Understanding Why Business Leaders Focus on Issues of Peace.” Business Horizons 59 (5): 481–492. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2016.03.012.

- Rettberg, A., and A. Rivas. 2012. “El sector empresarial y la construcción de paz en Colombia: entre el optimismo y el desencanto.” In Construcción de paz en Colombia, edited by A. Rettburg, 305–348. Bogotá, Colombia: Ediciones Uniandes. doi:https://doi.org/10.7440/2012.23.

- Reychler, L., and T. Paffenholz, eds. 2001. Peacebuilding: A Field Guide. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

- Richmond, O. P., and A. Mitchell. 2011. “Peacebuilding and Critical Forms of Agency: From Resistance to Subsistence.” Alternatives: Global, Local, Political 36 (4): 326–344. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0304375411432099.

- Ricigliano, R. 2003. “Networks of Effective Action: Implementing an Integrated Approach to Peacebuilding.” Security Dialogue 34 (4): 445–462. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010603344005.

- Rohwerder, B. 2016. Humanitarian Response in Middle-Income Countries (GSDRC Helpdesk Research Report 1362). Governance and Social Development Resource Centre (GSDRC). http://www.gsdrc.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/HDQ1362.pdf

- Ross, J., S. Maxwell, and M. Buchanan-Smith. 1994. Linking Relief and Development [Discussion Paper]. Institute for Development, University of Sussex. https://www.ids.ac.uk/download.php?file=files/dmfile/DP344.pdf

- Sandvik, K., and J. Lemaitre. 2013. “Internally Displaced Women as Knowledge Producers and Users in Humanitarian Action: The View from Colombia.” Disasters 37: S36–S50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12011.

- Sanford, V. 2003. “Eyewitness: Peacebuilding in a War Zone: The Case of Colombian Peace Communities.” International Peacekeeping 10 (2): 107–118. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/714002455.

- Schilling, J., S. L. Nash, T. Ide, J. Scheffran, R. Froese, and P. von Prondzinski. 2017. “Resilience and Environmental Security: Towards Joint Application in Peacebuilding.” Global Change, Peace & Security 29 (2): 107–127. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14781158.2017.1305347.

- Schneider, B. R. 2004. Business Politics and the State in Twentieth-Century Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Severino, J.-M., and O. Ray. 2010. The End of ODA (II): The Birth of Hypercollective Action (Working Paper 218). Center for Global Development. https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/1424253_file_The_End_of_ODA_II_FINAL.pdf

- Smillie, I. 1998. Relief and Development: The Struggle for Synergy (Occasional Paper No.33). The Thomas J. Watson Jr. Institute for International Studies. http://www2.hhh.umn.edu/uthinkcache/gpa/globalnotes/Smillie_Relief%20and%20Development.pdf

- Sollis, P. 1994. “The Relief-Development Continuum: Some Notes on Rethinking Assistance for Civilian Victims of Conflict.” Journal of International Affairs 47 (2): 451–471.

- Stoddard, A., and A. Harmer. 2005. Room to Manoeuvre: Challenges of Linking Humanitarian Action and Post-Conflict Recovery in the New Global Security Environment (Human Development Report Occasional Paper 2005/23). United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/hdr2005_stoddard_abby_and_adele_harmer_23.pdf

- Strauss, A., and J. Corbin. 1990. Basics of Qualitative Research. Washington DC: Sage Publications.

- Sumner, A. 2010. “Global Poverty and the New Bottom Billion: What If Three-Quarters of the World’s Poor Live in Middle-Income Countries?” IDS Working Papers 2010 (349): 1–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2040-0209.2010.00349_2.x.

- Sumner, A. 2011. The New Bottom Billion: What If Most of the World’s Poor Live in Middle-Income Countries? (Policy Brief). Center for Global Development. https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/1424922_file_Sumner_brief_MIC_poor_FINAL.pdf

- [OCHA] United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. 2011. Peacebuilding and Linkages with Humanitarian Action: Key Emerging Trends and Challenges (Occasional Policy Briefing No. 7). OCHA. https://docs.unocha.org/sites/dms/Documents/Occasional%20paper%20Peacebuilding.pdf

- Volberg, T. 2007. The Politicization of Humanitarian Aid and Its Effect on the Principles of Humanity, Impartiality and Neutrality. Bochum, Germany: Diplom.de.

- Westermann-Behaylo, M. K., K. Rehbein, and T. Fort. 2015. “Enhancing the Concept of Corporate Diplomacy: Encompassing Political Corporate Social Responsibility, International Relations, and Peace through Commerce.” Academy of Management Perspectives 29 (4): 387–404. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2013.0133.

- Wong, K. 2008. Colombia: A Case Study in the Role of the Affected State in Humanitarian Action (HPG Working Paper). Humanitarian Policy Group (HPG). https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/3419.pdf

- Woodrow, P., and D. Chigas. 2009. A Distinction with a Difference: Conflict Sensitivity and Peacebuilding. CDA Collaborative Learning Projects. https://www.cdacollaborative.org/publication/a-distinction-swith-a-difference-conflict-sensitivity-and-peacebuilding/

- World Bank. 2019. The World Bank in Middle Income Countries. Washington DC: World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/mic/overview.