Abstract

Could aquaculture lift farmers out of poverty and provide stability and an alternative livelihood to coca farming? Currently, aquaculture is pursued on a moderate scale, with the involvement of around 1500 small-scale farmers, in Caquetá, a department located in the Amazonian bioregion of Colombia. Some 400 farmers are organised in a grassroots non-governmental organisation (NGO) called Acuica. Cultivation and sale of fish provide a means for local fish farmers to move away from coca production and diversify their economic activities beyond cattle ranching and dairy production. In this article, we analyse the relationships among fish farmers, the state and Acuica. We argue that NGO success in securing donor funding can be underpinned by an NGO developmentalist gaze that homogenises its constituencies, which in the case of Acuica obscures different logics of fish production. This not only helps explain the mixed results in achieving development objectives but also suggests that initiatives that are intended to help farmers can imperil those who are already vulnerable. On the other hand, we argue that farmers’ strategic dependency on development initiatives displays their complex agency, as they are active consumers both engaging with and resisting the state’s NGO-mediated project of development.

Introduction

The fish harvest starts early in the day. Roberto’s farm is on a slope where the Amazon rainforest meets the Andean foothills, in the department of Caquetá in Colombia’s South. For Roberto, the prospect of a successful harvest, however remote, is tantalising. Not only is this his first fish harvest, but also it is the first time he has ventured into this activity. Decades of armed conflict put an end to his desire to make his dream of economic development become a reality. This territory was previously a centre of operations for FARC (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia). Business owners and farmers were summoned to this place to pay a ‘tax’ known as vacuna.Footnote1 Now, however, following the 2016 Peace Agreement, FARC’s presence in this area is a thing of the past. It takes us over two hours off road to get to Roberto’s farm. We drive across riverbeds and through several other estates to reach his farm where the harvesting will soon happen. We are left to wonder, what is driving the push for fish farming in such remote and virtually inaccessible locations?

The answer to this question is interwoven with the state’s and international donors’ push to fund development initiatives that provide farmers with alternative livelihoods to coca farming. In the department, 400 of the 1500 fish farmers are affiliated with Asociación de Acuicultores de Caquetá (Acuica) – Fish Farmers Association of Caquetá, a non-governmental organisation (NGO) that since its inception in 1995 has actively promoted and supported smallholder involvement in the sustainable production of Amazonian fish. Acuica is a unique organisation in Colombia’s fish-farming sector that hybridises grassroots membership-based characteristics with those of a development NGO seeking to address poverty and improve local livelihoods. This NGO singlehandedly spearheaded the establishment of the fish production network in Caquetá by conducting applied research, technology transfer to the farmers and the marketing of native Amazonian fish. This success, however, is built on a long history of developmentalism in the region that permeates farmers’ tense involvement with Acuica.

In this article, we analyse the relationships among fish farmers, the state and Acuica. Our findings are twofold. First, we find that Acuica’s technology-driven success in setting up fish production in the region through securing development funding involves what we call the ‘developmentalist gaze’ to signal the homogenisation of its constituency (cf. Andrews Citation2014; van Zyl, Claeyé, and Flambard Citation2019), which seems detrimental to the most vulnerable and precarious farmers (see Ferguson Citation2015; Levien Citation2018). Second, we find that farmers display a complex subjectivity in which they are selective consumers of the many development initiatives present in the region – which, we argue, allows them to selectively engage with or reject the state’s project of development. In short, we contribute to the extant literature on NGO-mediated development and NGO accountability (see eg Andrews Citation2014; Harsh, Mbatia, and Shrum Citation2010; van Zyl, Claeyé, and Flambard Citation2019; White Citation1999), by bringing attention to the problematic ways in which NGOs relate to their constituencies and by highlighting the role of local subjectivities in explaining people’s engagement, or not, with development.

We begin by discussing the key debates that inform our study in order to elaborate two propositions: first, that the ‘developmentalist gaze’ of NGOs is part of development’s technological rationality; and, second, that development recipients are active and selective consumers in a market of development initiatives in what we call ‘strategic dependency’. This is followed by the presentation of our case study, where we focus on two different development interventions to show farmers’ complex subjectivity. In our analysis, we demonstrate that not only farmers’ strategic dependency but also Acuica’s developmentalist gaze complicates any development interventions in the area. We conclude by arguing that NGOs’ mediation in development must account for the diversity amongst farmers as well as for farmers’ multiple engagements with and dependence on development initiatives.

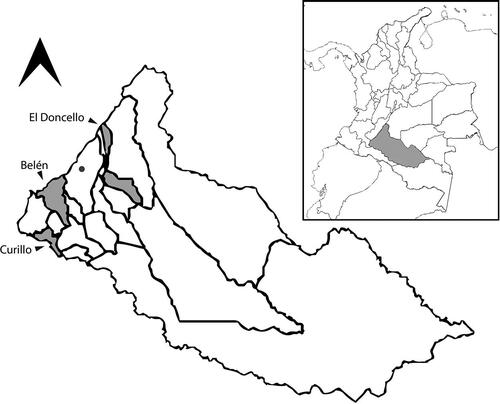

Arguments presented here are based on fieldwork carried out in Caquetá in three stages in 2018–2020. During the first stage, 16 interviews were conducted with stakeholders across the department, and observations were made of fish-farming practices. In the second stage, 91 farmers (nearly a quarter of Acuica’s members) from three municipalities (El Doncello, Curillo and Belén de los Andaquíes) were surveyed on all aspects of farming livelihoods (). Municipalities were selected on the basis of the presence of active Acuica committees and their relative peacefulness since the FARC agreement, which allowed us access to the farms. In addition, eight interviews with retailers and traders were conducted, as well as 15 follow-up interviews with farmers from El Doncello. In the final stage, we presented our findings to the farmers (El Doncello, n = 15; Curillo, n = 50; and Belén, n = 18) in participatory workshops that allowed us to compare and corroborate some of our insights. For confidentiality, we use pseudonyms and omit identifying characteristics of key participants. All interviews and conversations took place in Spanish; direct quotes were translated into English by the first author, fluent in both languages.

NGO-mediated development

The term ‘NGO’ can cover a variety of organisations that at least share the fact that they are neither for profit nor part of the government. While there have been extensive efforts made towards classifying and distinguishing the manifold arrangements in which NGOs perform their work (see eg Banks, Hulme, and Edwards Citation2015; Vakil Citation1997), here we focus on a hybrid organisation, Acuica, that combines grassroots membership-based characteristics with those of a development NGO that is seeking to address poverty and improve local livelihoods. The fact that Acuica intentionally drives both structural change and poverty alleviation allows us to flesh out some of the fundamental aspects of development policy and practice.

According to Mosse (Citation2004), two views predominate within the debates on development policy and practice: an instrumental view, which sees development as rational problem solving; and a critical viewFootnote2 that sees development as a rationalising discourse that legitimises neo-colonialism, mobilises particular knowledge and representations of the social world, and has implied increased inequality and experiences of exclusion. We cannot do justice to the complexity of these debates in this article; however, we can discuss some aspects relevant to the study of NGO-mediated development.

The first view concerns instrumental adjustments for shaping and improving the way development is done. This has been supported in part by the notions that NGOs can provide services to communities that the state cannot (Korten Citation1990), that NGOs embody civil society and are hence able to facilitate political reform (White Citation1999), or that by being less prone to corruption, NGOs have a comparative advantage in alleviating poverty (Edwards and Hulme Citation1996). Within this view, the literature’s focus is on finding ways to improve the existing development apparatus (ie service provision, markets, state policies, NGO performance). For example, researchers have looked at whether NGO involvement in service provision reduces government responsiveness (Cook, Wright, and Andersson Citation2017) and spending (Torpey-Saboe Citation2015). Concerning NGOs’ development politics, the focus has been on whether NGOs are accountable to their donors or their constituencies (Aldashev and Vallino Citation2019; Brett Citation2003), or whether the place where NGOs have their base of operations affects their performance in terms of accountability (Fruttero and Gauri Citation2005; van Zyl, Claeyé, and Flambard Citation2019).

An important aspect of this first view of development is how NGOs tap into the development apparatus to alleviate poverty by claiming to provide a ‘better’ version of economic development and social services than the one provided by the state and the private sector. The success (or not) of an NGO depends on how it manages the interests of donors and constituencies alike (Andrews Citation2014; Burger and Owens Citation2013). While attempting to drive the kind of development that meets donor expectations, creates conditions for structural change and fulfils, to some extent, the desires of their constituencies, NGOs can also get caught up in the development apparatus (Matthews Citation2017) – that is, in uncritically advancing interventions, both for the sake of the NGO’s survival as an organisation (Burger and Owens Citation2013) and to meet the expectations of its constituencies that demand action. Furthermore, development recipients do not necessarily benefit from interventions in an equal manner, yet in the process of designing programmes and plans they are all depicted as ‘people in need of development’ – thereby erasing their subjective characteristics. We call this homogenising representation a developmentalist gaze. In their daily operation, NGOs’ developmentalist gaze measures the social, economic and cultural aspects of people according to donors’ requirements. Thereby, NGOs erase differences among those same people, and also repackage and relabel previous participants, so that they fit into development’s apparatus.Footnote3 In terms of development interventions, this is problematic as not all people relate to the capitalist economy in the same way, and one-size-fits-all interventions may cause more harm than good.

The second view questions the entire framing of development, looking into its historical roots and relations of power. Development is portrayed as an ideology that conceals the ulterior motives of advancing power, dominance and markets (Escobar Citation1995; Ferguson Citation1994). Despite the possibility of NGOs working as grassroots-oriented ‘democratizers of development’ (Bebbington Citation2005, 937), critical observers argue that NGOs can also be part of dominant structures with only a marginal contribution to poverty relief (Manji and O’Coill Citation2002). This is the case because, at least in some instances, NGOs have weak roots in civil society and have had their scope and reach narrowed to service delivery and the promotion of democracy (Banks, Hulme, and Edwards Citation2015). Interventions, such as those carried out by NGOs, mobilise particular knowledge and representations of the world with implicit claims of the ways other people should live and the ways their lives could be improved (Li Citation2007; Ziai Citation2017). While often avoiding the romanticisation of poverty, this line of critique runs against the idea of European universalism that devalues local and indigenous experience (Escobar Citation1999; Law Citation2015).

In this critical view of development, scholars have also focused on the ways in which people on the receiving end of development oppose the neoliberal governmentality of development through social protests and mobilisations (eg Igoe Citation2003; McNeish Citation2017), resist in quiet everyday forms (eg Scott Citation1990), or even embrace it (Rangan Citation1996). In particular, some critical scholars point to the difficulty in navigating analytically people’s desire for development on the ground (Matthews Citation2017; Wainwright Citation2008). This seeming ‘acceptance’ of development, however, reflects a complex subjectivity of development recipients. In order to access it analytically, we build on Acosta García and Farrell’s (Citation2019) theorisation of development as a ‘gift’. Drawing on Mauss’ (Citation2002 [1925]) classic The Gift and Marcuse’s (Citation1964, Citation1969) critical theory, they argue that accepting the gift of development gives rise to obligations, including that of subordination to ‘technological rationality’. In particular, they note that it is possible to accept the gift of development yet refuse, at least to some extent, the social obligations associated with that acceptance.

Our interest here lies in the ways fish farmers in Caquetá depend upon development initiatives for their incomes, yet refuse to accept the social obligations that accompany their participation, such as repaying loans or sustaining infrastructure. Hence, we attempt to understand farmers’ agency in these complex situations, while avoiding a paternalistic view that somehow defines how they should live their lives (Escobar Citation1995, 215). As we will describe below, farmers are not only constrained by the department’s historically precarious and violent conditions; they are also influenced by disillusion with and distrust of the Colombian state. Yet they are able to show a degree of agency by being active consumers in the market for development grants and projects that are available to them. Within this narrow space, we define ‘strategic dependency’ as the capacity farmers have to choose to engage with development initiatives while refusing, to some extent, the obligations implied in participating in them. By employing strategic dependency as a conceptual lens, we can explore the nuances implicated in the ways in which (some) farmers engage with and reject the state’s NGO-mediated project of development.

Making an NGO through small-scale aquaculture

Acuica is a grassroots membership-based organisation that combines roles similar to that of a trade union, a development NGO, a research institute, and a strategic input supplier (of fingerlings). In the Colombian fish industry, there is no other organisation that provides such comprehensive services. The main purpose of Acuica, as founding member and former director Emilia explained, is to ‘develop research that could reach and be applied by small-scale farmers, with a social well-being philosophy, intended to improve the quality of life … or [even] to dignify the quality of life of the small-farmers’.

Acuica’s work is focused on Caquetá – an administrative region (department) located in the country’s southern Amazonian region. The department encompasses over 89,000 km2, with several rivers flowing from the Andes into the Amazon River. Caquetá’s political economy has followed successive cycles of the boom and bust of commodity production (ie quinine, rubber, cattle, cocaine, milk) since the mid-nineteenth century, leaving a history and legacy of conflict (Domínguez Citation2005; Reyes Citation2009; Sinchi Citation2000). The area has also witnessed the country’s armed conflict, with a significant presence of left-wing guerrilla groups, right-wing paramilitary groups, drug-traffickers and the Colombian military, often leaving farmers caught in the middle (Carroll Citation2011; Vásquez Delgado Citation2015).

Acuica’s activities started in 1995 through the joint efforts of a few farmers and a group of young professionals from the local university, who wanted a different development trajectory for the region than that which was dependent on cattle, dairy and coca farming. They wanted to use Caquetá’s geographical features, including high rainfall, an abundance of water, warm temperatures and clay soils suitable for building open ponds with minimal investment. Additionally, Amazonian biodiversity, with over 500 reported species of fish, remained untapped as regards the production of fish for either consumption or ornamental purposes (Bogotá-Gregory and Maldonado-Ocampo Citation2006).

Today, Acuica reaches seven of Caquetá’s 16 municipalities. In each of them, fish farmers are organised in grassroots associations referred to as ‘local committees’. Added together, Acuica represents around 400 of the estimated 1500 fish farmers in Caquetá. Our survey data indicate that farmers combine a host of livelihoods, alternating and cross-financing the production of cattle, dairy, poultry, agriculture and aquaculture – with nearly half of them reporting aquaculture as their main source of income (see ). Notably, farmers rely on dairy production to afford fish feed, which, according to our survey data, accounts for 80% of the production costs of aquaculture activities. In turn, aquaculture serves as a way to accumulate capital, which is monetarised at harvest time when farmers sell all the fish in their ponds to wholesalers or on an ongoing basis to retailers in the villages. These two practices constitute a crucial distinction between different producers and point to their socio-economic diversity, the consequences of which we will come back to.

Table 1. Descriptive data on surveyed farmers.

To begin production, farmers require ponds, fingerlings and fish feed. Ponds are the greatest entry barrier. Farmers resort to building ponds themselves or contracting builders to do so, but in both cases, they reported dykes collapsing during rain events. More than 90% of the farmers in the survey have several ponds, but around 80% have an aggregated pond area of less than a hectare, falling into what Acuica considers small-scale fish farmers (see ). In general, fish farmers report beginning their activity by buying a farm with ponds or reservoirs (82% are landowners), seeing their neighbours build ponds or being invited to participate in an aquaculture development initiative led by Acuica.

Strategic dependency in aquaculture development projects

Tapping into local, national and international funds, Acuica has implemented a series of development initiatives that have enabled the setting up of a (small) aquaculture industry in Caquetá (). Implementing the initiatives on the one hand has ensured Acuica’s organisational survival and consolidation, while on the other hand it has also pushed Acuica to buy into development’s technological rationality (Acosta García and Farrell Citation2019; Marcuse Citation1964), and the deployment of a developmentalist gaze upon those it intends to represent and help. To illustrate our point regarding farmers’ strategic dependency and complex subjectivity, we focus here on the implementation of two key initiatives: PLANTE and Alianzas Productivas (Productive Alliances). The first one covers some of the initial years and the gradual consolidation of Acuica through external funding from the state’s programmes against drug production. Then, we go into detail concerning the second initiative covering the most recent period characterised by a broad-based scaling up of production.

Table 2. Acuica’s main development initiatives.

First initiative: PLANTE

Since the late 1990s, Acuica promoted the expansion of fish production in the region by tapping into state funds intended to curb coca production. According to reports at the time (ElTiempo Citation1995; Sinchi, Citation2000), 80% of Caquetá’s population made a living from coca farming in the 1990s. The government implemented Plan Nacional de Desarrollo Alternativo (PLANTE) – the National plan for alternative development – as a ‘contingency strategy’ to complement Colombia’s military efforts against the drug cartels (CONPES 2734 Citation1994). The programme aimed to diversify farmers’ incomes in the short term by ‘alleviating the unstable working and income conditions that farmers would be put under once the illicit economy disappears or becomes drastically controlled’ (CONPES 2835 Citation1996, 3). As Acuica was promoting an alternative livelihood to coca production, it qualified to receive funding from PLANTE, which seeded the organisation and became its main source of funding for several years. From 1998 to 2000, PLANTE funded several projects focusing on researching, developing and transferring technology for the production of fingerlings, providing extension services, improving Acuica’s facilities, and establishing processing facilities. The projects had mixed results, as Julio, a farmer from El Doncello involved in the direction of the local committee, recalls:

Plante gave us a collection centre and a seed capital. We had a cold storage room, display cabinets … technical personnel visited the farms and told farmers you can cultivate here or there …. But when harvest time came, no one harvested! Because they ate the fish, they sold them [to other people] and they didn’t pay [the committee] back … we would call them, and they would say: this is from the government, why are you charging us? Do you want to steal it for yourself? From those people, only one person paid back. The programme was a loan …. They would get the fish feed, and we would receive the fish [to sell in the display cabinets]. It didn’t work.

Despite its seeming failure, PLANTE was of key importance for Acuica. First, it enabled them to create regional autonomy in fingerling production. Previously, fingerlings were produced twice a year in the Llanos region and flown to Caquetá at a high cost. Acuica’s research on cachama (Colossoma macropomum) reproduction and farming for meat production allowed it to begin producing and selling fingerlings, as well as training farmers in reproductive technologies. Shortly afterwards, five farmers also established separate companies focusing on fingerling production.

Secondly, PLANTE also funded the first effort to scale up and diversify production. Cold-storage collection centres were built in five municipalities in order to process and sell higher value fish products such as fish sausages, hamburger patties and croquettes. Despite the failure of many farmers to meet the regulations for processed foods, the five centres changed consumer preferences and improved the overall quality of the fish sold in the market place. Unfortunately, the armed conflict in the mid-noughties severely affected Caquetá, and some of the cold-storage facilities were sold, while others were ‘lost’ to armed actors. Production of fish also came to a halt; in San Vincente, FARC asked farmers to stop cultivating fish, as it was perceived as a governmental strategy to erode their grip. However, it was not only armed conflict that affected Acuica’s plan for cachama expansion into the domestic market: consumers see cachama as a ‘poor people’s food’ and prefer tilapia, as it has fewer bones. Moreover, the Llanos region and neighbouring Huila, the country’s largest fish producer (OECD Citation2016), also farm cachama and are closer to the big cities, giving them a competitive edge. Hence, it was necessary for Acuica to look for other avenues with a potential for expansion.

Second initiative: Productive Alliances

In 2012 and in 2016, Acuica sought funding from the government programme called Alianzas Productivas (Productive Alliances) to increase fish production. This World Bank-sponsored programmeFootnote4 began in 2002 to ‘generate incomes, create employment and promote the social cohesion of poor rural communities in an economic and environmentally sustainable manner’ (CONPES 3467 Citation2007, 3). The rationale of the programme was that the Alianzas initiative should address a series of constraints that farmers were facing (World Bank Citation2001).Footnote5 These would be overcome by providing seed capital (through grants and loans repaid into a revolving fund) to farmers and by creating agreements linking associations of small-scale farmers with traders, thereby giving the former access to export markets.Footnote6 The official assessment of the programme was favourable (CONPES 3467 Citation2007; World Bank Citation2015, 13) and Acuica became quite heavily involved in the programme, which marks a considerable expansion in its activities. The first project in 2012 focused on the production of ornamental fingerlings (arowana)Footnote7 for export at El Doncello; the second focused on meat production and included El Doncello as well as other four municipalities. José, a member of Acuica’s technical personnel who had been involved in the process since 2011, explained to us:

In January 2013 an Alianza Productiva project started. The first project executed by Acuica was with arowana. Back then, we were trying to move forward with the ornamental [farming] part so that people could see that they have more options, because often they close themselves off from other possibilities, claiming that ‘cachama is too cheap’, ‘that [traders from] Huila bring cachama at a lower price than I can produce it’, and ‘then I do not have a place to sell, and if it is not cachama, what else [can it be]’. That Alianza was in the municipality of El Doncello, and we thought of El Doncello because first, they had a strong [local] committee, and second, Acuica’s research was centred in that municipality.

For an Alianza to get funded, a local committee had to put forward a list of at least 30 farmers, who had to meet some basic requirements.Footnote8 As it was difficult to find enough farmers who met them, often a farm that had several ponds could lease some of them to others so that they too could enter the scheme. Hence, in reality, one farm could have several people, often related, benefitting from the scheme.

Each Alianza funded several jobs in a local committee intended to create technological rationality (Acosta García and Farrell Citation2019; Marcuse Citation1964): first, a manager for a newly created revolving fund;Footnote9 second, a social-business professional who, by visiting farmers, would help them develop entrepreneurial skills and organise the revolving fund; and, third, a technical professional who would help farmers improve their technical capacities and solve any issues that might arise. In addition to personnel, funds were used to pay for pond improvements, fish feed, fingerlings, fertilisers and medicines. Each Alianza provided funding for one harvest, including a subsidy of a third of the production costs of one harvestFootnote10 and the rest as a loan. After the first harvest, famers had to repay the loan portion of the programme to a revolving fund, from which they could request subsequent funding.

The first project in El Doncello succeeded in increasing the number of farmers by 100. However, the setting up of the fund and its management has not been without issues, as some farmers struggle to pay back the loans. Farmers with whom we spoke acknowledge that while the fund is still working and some have received additional funding from it, others have decided either not to pay back the loan or to drop out entirely and claim they will pay back in other ways, such as through the selling of cattle. Moreover, in securing funding, Acuica’s leadership seemed to create relationships with the farmers that were akin to client–patron,Footnote11 as farmers expected Acuica to develop a more active role in maintaining their profits. As one farmer pointed out, Acuica has not always kept its commitment to purchase farmed fingerlings. Additionally, several farmers complained that the international unit price for fingerlings has dropped in recent years and that exceptionally cold weather in 2019 hampered their production, complicating their ability to stay in business. Some farmers have dropped out of the scheme and have said to Acuica ‘take back your fish’.

The second project, in 2016, provided Acuica with funding for five additional Alianzas Productivas for members of equal number of municipal committees. In order to reduce the length of farmers’ production cycles, farmers were linked with a trader who would buy the entire harvest all at once. As already mentioned, many farmers fished their ponds over several weeks, selling to neighbours or retailers in the towns. Consequently, they were unable to start a new production cycle. The second Alianzas encountered difficulties during the transition to a new government in late 2018, as the Ministry of Agriculture froze all payments. Farmers did not receive the promised fish feed, for which many held Acuica accountable as a proxy for the government’s inefficiency. Several farmers expressed their discontent and intention to drop out of the scheme. Additionally, many farmers delayed the harvest, leading to underfinancing of the revolving funds. Others were simply not regularly feeding the fish provided by the initiative, as they could not cover the costs of the fish feed. That said, several farmers had already harvested, yet many of them delayed their decision to repay the fund, claiming that the government’s debt to them should offset their repayments. However, several farmers described the programme as successful in terms of the knowledge they have accrued and the improvements to their entrepreneurial fish-farming skills.

Small-scale aquaculture: heterogeneous constituencies in markets of development initiatives

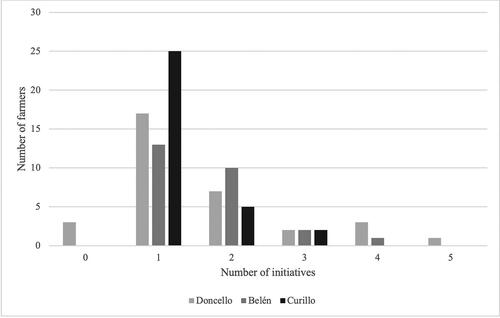

Since the final years of the implementation of Alianzas coincided with our fieldwork, we were able to capture the diversity of farmers participating in this initiative in our field data (), which includes survey data on farmers’ production and sales of all farming activities (including crops and livestock), observations of fish-farming practices and interviews on how farmers navigated through all these development initiatives. While the difficulties the Alianzas have run into can be explained by many factors, one of their main problems appears to be the design of the type of development intervention itself, which requires a minimum of 30 farmers per municipality in order to receive state funds. Thus, by examining closely both the farmers and the conditions in which they are producing fish, we argue that, to secure funding, Acuica’s developmentalist gaze homogenised an otherwise heterogeneous group of farmers and did not consider farmers’ multiple engagements (see ). Data suggest that farmers in general follow two production logics that enjoy some degree of overlapFootnote12: capitalist production and petty commodity production. These two analytical categories were validated in the field during workshops in each of the three municipalities.Footnote13

Capitalist farmers strive to run distinctive production cycles in order to harvest sequentially and exploit economies of scale. Farmers can afford to feed the fish without interruption and plan for expansion, investing in technologies that are more complex and building more infrastructure for fish farming.Footnote14

Petty commodity producers, in contrast, barely engage with the capitalist economy. Farmers’ access to the cash economy relies on their ability to monetise surplus farm products that are not used for subsistence. These farmers participate in development initiatives, though with poor results and with many dropping out.Footnote15

Both capitalist and petty commodity producers, with their complex subjectivity, navigate through the different development initiatives with varying degrees of success, some actively embracing and succeeding in them, others wanting to succeed but unable to do so, and still others explicitly rejecting them. In particular, NGOs as providers of services aligned with the state’s objectives are affected by state distrust, disenfranchisement and poverty. Moreover, NGOs rely on people’s trust and acceptance to be able to fulfil their objectives (Deng and O’Brien Citation2020). These complex dynamics are reflected in material and symbolic terms, for example in farmers’ refusal to continue participating in the initiatives or in their demands directed at Acuica to ‘take back your fish’, despite that organisation merely being an intermediary in the purchase.

Most small-scale farmers thus appear to accept the gift of development but reject the social relations implied in receiving it (Acosta García and Farrell Citation2019). While this may reflect farmers’ complex subjectivity and deep distrust in the government, exemplified by the government’s indiscriminate aerial spraying of crops and in treating farmers as potential guerrillas (Hough Citation2011; Vásquez Delgado Citation2015), it could also be explained in terms of strategic dependency, where farmers are active consumers in a market of development projects (see ). The myriad of development initiatives available to farmers has had the unintended consequence that farmers have acquired skills in supporting their livelihoods by learning how to navigate development projects, joining in and dropping out of schemes at different times – in other words, learning how to be strategic with their involvement. This multitude of engagements, which includes farmers participating in up to five initiatives at a given time (see ), also means that to a certain degree there is a crowding out of farmers’ involvement in the initiatives in which they participate. Some farmers simply do not have the time to participate in project meetings intended for community building and dealing with internal affairs, such as the handling of revolving funds. In the words of Acuica’s personnel, ‘farmers only come to the meetings when they can sign up to new projects’, thus highlighting the tension between the NGO and its constituency.

Table 3. Types of initiatives and farmer participation.

To explore the complexities involved in the relationship between the NGO and its constituency, we need to look closer at Acuica’s developmentalist gaze as deployed in the category of ‘small-scale farmers’ they claim to represent. Not accounting for the difference among the farmers who pursue the two distinct logics of production (capitalist and petty commodity producers) accounts for a substantial part of the failure of the different fish-farming projects. This is particularly the case for those projects that require relatively advanced technical ability, access to capital and compliance with the conditions of market-oriented production (ie batch production and harvesting rather than occasional sales to cover cash needs). Homogenising its constituency as ‘small-scale’ has proved a successful strategy in terms of Acuica securing repeated funding to survive as an organisation (cf. Burger and Owens Citation2013), but at the same time the NGO is also caught up in its own strategic dependency on the development apparatus. What appears to be lacking is the uncoupling of the design of development interventions, including researching and transferring technologies, from their dependence on the market,Footnote16 and a differential treatment for the many kinds of farmers.

As has been discussed by development studies scholars (Escobar Citation1995; Ferguson Citation1994), interventions often appear as what Levien (Citation2018) calls ‘dispossession without development’, where the ultimate goal has been to create livelihoods that sustain profits in new markets. Hence, the malfunctioning of the revolving funds makes sense as a symptom of exposing precarious and vulnerable farmers to an economic activity that requires a constant cash influx, signalling the underlying logic within development that is intended to create profits for corporations and not for the majority of the people (Ziai Citation2017). Such a rationale could well apply here, with fish-farming initiatives creating additional customers for the multinational fish feed providers present in Caquetá; after all, fish feed accounts for 80% of production costs, and many farmers depend on subsidies and development initiatives to be able to kick-start their production and even to sustain it. This, however, seems to be an inappropriate and unfair way to account for Acuica’s role in working for and with the farmers in order to develop and transfer technology to them. Nevertheless, it seems clear that some of the interventions (ie those promoting farming of new – ornamental – fish species) involve a high degree of risk, which is then transferred to the small-scale farmers, many whom are petty commodity producers and end up being part of the experiment in setting up a completely new value chain. Hence, unlike Andrew’s (Citation2014) view that beneficiaries rarely question NGOs, it was predictable here that small-scale farmers would ask Acuica to bear some of the responsibility when things went wrong.

Analysing Acuica’s relationship with its constituency, at least three main points emerge. First, as with other rocky relationships between NGOs and their constituencies, values (Deng and O’Brien Citation2020), views and desires for development (Andrews Citation2014; Matthews Citation2017), as well as farmers’ complex subjectivity, come into play. Farmers here can pick and choose the best development project in the market as well as which obligations they wish to fulfil. Second, NGO dependence on donor funding combined with a developmentalist gaze does not leave much space to raise questions of distribution (Does everyone benefit from the intervention?) and equity (Does everyone want to commit?). This is not unique to our case; as Mohan (Citation2002) observed in Ghana, NGOs can profit from fragmented constituencies. Moreover, this raises questions regarding who the NGO is accountable to and whether it is fulfilling its mission in the best possible way (van Zyl, Claeyé, and Flambard Citation2019). Third, if NGOs decoupled their interventions from their orientation towards market dependency, expert knowledge and constant technological change, even ever so slightly, as Escobar (Citation2018) argues in relation to development, the alternatives to development could become a reality. However, as we have shown in this article, the question remains whether NGOs that are part and parcel of the development apparatus can operate without their technological rationality (Acosta García and Farrell Citation2019; Marcuse Citation1964). Acuica’s mixed role in creating alternative trajectories while at the same time being caught up with its own dependence shows that this is a far from simple task. A conscious understanding of local contexts, of NGOs’ constituencies and of the orientation of technological innovation could perhaps point towards the goal of truly democratising development (Bebbington Citation2005).

Conclusion

In this article, we have shown the complex reality of Acuica in its attempts to create an alternative development path for Caquetá, other than cattle ranching or coca farming. We have traced the variegated history of this organisation in its struggle to create a grassroots social base while taking advantage of development funds available in the region. Our focus on two particular examples of its many development interventions allowed us to theorise both the NGO’s relation to its constituencies and the relationship of the farmers with the many NGOs present in the area. We have argued that instead of approaching farmers’ apparent desire for development as contradictory to the post-development discourse, farmers’ participation in development need not mean uncritical acceptance. On the other hand, we have shown that an NGO’s particular ways of working with its constituency can be problematic if it is not attentive to people’s particular circumstances.

An important aspect of NGOs’ desire to help their constituencies is to accommodate donors’ requirements concerning the commercialisation of local livelihoods. However, as we have documented in this case study, even well-intentioned interventions may result in putting some of those constituencies in peril. This is not to say that NGO assistance and support to farmers in the broad sense of the word is not needed, especially in regions and countries where a slow and fragile transition towards peace is taking place. In this sense, we have elaborated two propositions: first, NGOs with their ‘developmentalist gaze’ overlook the possibility that while some farmers fully engage with the market economy and have the disposable income needed to maintain their participation in a certain initiative (eg via fish feed) without endangering their food security, others are in a more precarious situation, being simultaneously inside and outside capitalist relations. Second, development recipients are not passive subjects, and in fact they display a complex subjectivity. This is reflected in the notion of ‘strategic dependence’ that signals farmers’ active role in selecting and participating in a market of development initiatives available to them.

Our results raise questions concerning the further marginalisation and impoverishment of already precarious farmers by those same initiatives that are intended to create incomes for them. Development interventions need to account for farmers’ multiple engagements with other initiatives and to find ways to provide assistance to those who are not fully engaged in capitalist relations, not by creating marketable livelihoods, but instead by creating genuine alternatives to development. This is especially the case where farmers, like those in Caquetá, already have to contend with armed conflict, structural marginalisation, distrust of the state and the overall risks of small-scale farming in rural areas of the Global South.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the farmers of Caquetá and to Acuica’s personnel for participating in this study. Also, we are grateful to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark for providing the funding for this research.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nicolás Acosta García

Nicolás Acosta García is a cultural anthropologist. His work focuses on the political ecology of development, ecotourism and biodiversity conservation on local, Afrodescendant and indigenous peoples. He received his doctorate from the University of Oulu, Finland, and currently is a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Postdoctoral Fellow at the School of Global Studies at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden.

Niels Fold

Niels Fold is a professor in development geography at the University of Copenhagen. His research interests include globalisation and industrial development, regional growth centres and spatial restructuring, rural–urban dynamics, agro-industrial linkages and organisation of global value chains based on agricultural crops.

Notes

1 This word’s most common usage in modern Spanish is ‘vaccination’, implying that people protect themselves against some kind of harm. But it also related to ‘cow’ (vaca) and in this context refers to tax levied per cow.

2 See Ziai (Citation2017) for a recent summary of the main arguments of this view of development.

3 See Mohan and Stokke (Citation2000) for a critique on the essentialism of development ‘recipients’.

4 The programme had two phases, both deemed ‘satisfactory’ by the World Bank and the Colombian government. The first phase (2002–2008) was financed by a World Bank loan of US$32 million and US$20 million as a set-off from Colombia’s government (World Bank Citation2001). The second (2007–2015) was also financed by the World Bank through a loan of US$30 million with a set-off of US$310 million from the Colombian government (World Bank Citation2015).

5 According to the World Bank’s (2012) assessment, the programme intended to provide seed capital, supporting cooperatives, offering technical assistance through private firms, reactivating abandoned land via purchase negotiations, ensuring access to markets and stimulating partnership building. Notably, the crucial element – assisting farmers to buy land (thus leaving landless farmers, who are the poorest segment of the rural population, out of the programme) – was removed, and grants were changed into loans, to be repaid into a revolving fund.

6 See Ballvé (Citation2020) for a rich study on paramilitary groups subverting this policy in northern Colombia.

7 Arowana is one of the most popular and expensive species of ornamental fish. Worldwide there are seven species, all of which are kept as pets (Joseph et al. Citation1986). Young arowanas can fetch hundreds of dollars in Asian wholesale markets, with rare breeds selling for up to US$70,000 (The Economist Citation2018). The silver and blue kinds (Osteoglossum bicirrhosum and Osteoglossum ferreirai, respectively) found in South America are of less commercial value in comparison to their Asian counterparts, but there is still a growing demand for them.

8 Participation requirements included: being literate (or at least having a literate family member), having been a farmer for at least the previous three years, having family capital that does not exceed 196 million pesos (284 minimum salaries, ca. US$63,000), earning a monthly income of less than two minimum salaries (ca. US$450) and owning less than 150 ha of land. The land requirement is less than two Unidad Agrícola Familiar (UAF) – Family Farm Unit. One UAF is used as a reference for land reform and corresponds to the theoretical number of hectares needed to support a single family, which varies depending on a series of soil parameters.

9 The idea was to train a person so that once the grant support was removed, they would continue managing the revolving fund. This included skills such as accounting, negotiating with traders and keeping up the paperwork.

10 Around COP7 million per farmer (ca. US$2200).

11 Lewis (Citation2017) provides a similar and magnified account in Bangladeshi NGO-mediated development.

12 In addition to the two categories, we found one group of farmers who fell between the two logics of production. These farmers have an average of 5.5 ponds, which add up to an average of 0.7 ha of pond area. Their average production per farm is 2.3 tonnes of fish per year. Farmers usually have other incomes from dairy and agriculture, which allow them to cross-finance aquaculture. However, production is not at full capacity, as farmers face various restrictions. First, some farmers report not having sufficient capital to invest in fish feed or fingerlings in order to make their ponds produce at full capacity. Second, some farmers are either learning how to farm fish or divesting, dedicating their time to other activities. Farmers in this category tend to sell their harvest to both retailers and traders.

13 As ‘capitalist’ and ‘petty commodity production’ belong to academic jargon, we used as proxy categories ‘intensive and fast farming’ to refer to capitalist production, and ‘extensive and slow farming’ to refer to petty commodity production. While at this stage in our research we are unable to chart each of these farmers’ production logics in detail, what is important here is that farmers acknowledged the two production logics as valid and were able to place themselves within one of them according to the way in which they produced their fish.

14 According to our data these farmers have an average of 16 ponds, with at least one dedicated to raising fingerlings to juveniles. The ponds add up to an average of 2.4 ha per farmer, with average production of 4.5 tonnes per year. Additionally, they tend to sell their large-scale harvests to traders and rarely to retailers.

15 According to our data these farmers have an average of 4.1 ponds, which add up to an average of 0.4 ha in pond area. On average, the farms produce 0.7 tonnes of fish per year. The production of these farms, including fish farming, is predominantly for subsistence. For example, most farmers produce less than 20 L of milk a day (COP20,000 – ca. US$6.2) and sell crops in small quantities, such as plantain, cassava, sugarcane, and sown pasture to local retailers. For most of these farms, incomes are around the country’s poverty line (COP257,433 – ca. US$80.3). These farmers can barely afford fish feed, and their fish grow at a slow pace and risk becoming ill. These farmers participate in development initiatives, though with poor results and with many dropping out. Most farmers primarily sell their harvest to neighbours and retailers over extended periods of time (1–2 months), and only a few sell in larger batches to traders.

16 See Escobar (Citation2018) for theoretical approaches to design in development contexts.

Bibliography

- Acosta García, N., and K. N. Farrell. 2019. “Crafting Electricity through Social Protest: Afro-Descendant and Indigenous Embera Communities Protesting for Hydroelectric Infrastructure in Utría National Park, Colombia.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 37 (2): 236–254. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775818810230.

- Aldashev, G., and E. Vallino. 2019. “The Dilemma of NGOs and Participatory Conservation.” World Development 123: 104615. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104615.

- Andrews, A. 2014. “Downward Accountability in Unequal Alliances: Explaining NGO Responses to Zapatista Demands.” World Development 54: 99–113. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.07.009.

- Ballvé, T. 2020. The Frontier Effect: State Formation and Violence in Colombia. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press.

- Banks, N., D. Hulme, and M. Edwards. 2015. “NGOs, States, and Donors Revisited: Still Too Close for Comfort?” World Development 66: 707–718. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.09.028.

- Bebbington, A. 2005. “Donor-NGO Relations and Representations of Livelihood in Nongovernmental Aid Chains.” World Development 33 (6): 937–950. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2004.09.017.

- Bogotá-Gregory, J. D., and J. A. Maldonado-Ocampo. 2006. “Peces de la Zona Hidrográfica de la Amazonía, Colombia. Biota Colombiana 7 (1): 55–94.

- Brett, E. A. 2003. “Participation and Accountability in Development Management.” The Journal of Development Studies 40 (2): 1–29. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380412331293747.

- Burger, R., and T. Owens. 2013. “Receive Grants or Perish? The Survival Prospects of Ugandan Non-Governmental Organisations.” Journal of Development Studies 49 (9): 1284–1298. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2012.754430.

- Carroll, L. A. 2011. Violent Democratization: Social Movements, Elites, and Politics in Colombia’s Rural War Zones, 1984-2008. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

- Cook, N. J., G. D. Wright, and K. P. Andersson. 2017. “Local Politics of Forest Governance: Why NGO Support Can Reduce Local Government Responsiveness.” World Development 92: 203–214. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.12.005.

- Deng, Y., and K. J. O’Brien. 2020. “Value Clashes, Power Competition and Community Trust: Why an NGO’s Earthquake Recovery Program Faltered in Rural China.” Journal of Peasant Studies 48: 1187–1206. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2019.1690470.

- Consejo Nacional de Política Económica y Social [CONPES]. 1994. Documento Conpes 2734: Plan Nacional de Desarrollo Alternativo PLANTE. Bogotá: Departamento Nacional de Planeación, República de Colombia.

- Consejo Nacional de Política Económica y Social [CONPES]. 1996. Documento Conpes 2835: Plan Nacional de Desarrollo Alternativo PLANTE – Documento de evaluación: problemas y soluciones. Bogotá: Departamento Nacional de Planeación, República de Colombia.

- Consejo Nacional de Política Económica y Social [CONPES]. 2007. Documento Conpes 3467: Concepto favorable a la nación para contratar un empréstito externo con la banca multilateral por un valor de hasta US $30 millones o su equivalente en otras monedas, para financiar parcialmente el proyecto “Apoyo a Alianzas Productivas Fase II”. Bogotá: Departamento Nacional de Planeación, República de Colombia.

- Domínguez, C. 2005. Amazonía colombiana: Economía y poblamiento. Bogotá: Universidad Externado de Colombia.

- Edwards, M., and D. Hulme. 1996. “Too Close for Comfort? The Impact of Official Aid on Nongovernmental Organizations.” World Development 24 (6): 961–973. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(96)00019-8.

- ElTiempo. 1995. “El plante llega a caquetá.” ElTiempo. https://www.eltiempo.com/archivo/documento/MAM-465006

- Escobar, A. 1995. “Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World through Development.” Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/mind/102.405.1.

- Escobar, A. 1999. “After nature: Steps to an antiessentialist political ecology.” Current Anthropology 40 (1): 1–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/515799.

- Escobar, A. 2018. Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy and the Making of Worlds. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Ferguson, J. 1994. The Anti-Politics Machine: “Development,” Depoliticization, and Bureaucratic Power in Lesotho. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Ferguson, J. 2015. “Give a Man a Fish: Reflections on the New Politics of Redistribution.” Minneapolis, MN: Duke University Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822375524-002.

- Fruttero, A., and V. Gauri. 2005. “The Strategic Choices of NGOS: Location Decisions in Rural Bangladesh.” Journal of Development Studies 41 (5): 759–787. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380500145289.

- Joseph, J. D. Evans, and S. Broad. 1986. “International Trade in Asian Bonytongues.” TRAFFIC Bulletin 3 (5): 73–76.

- Harsh, M., P. Mbatia, and W. Shrum. 2010. “Accountability and Inaction: NGOs and Resource Lodging in Development.” Development and Change 41 (2): 253–278. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2010.01641.x.

- Hough, P. A. 2011. “Disarticulations and Commodity Chains: Cattle, Coca, and Capital Accumulation along Colombia’s Agricultural Frontier.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 43 (5): 1016–1034. doi:https://doi.org/10.1068/a4380.

- Igoe, J. 2003. “Scaling up Civil Society: Donor Money, NGOs and the Pastoralist Land Rights Movement in Tanzania.” Development and Change 34 (5): 863–885. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2003.00332.x.

- Korten, D. C. 1990. Getting to the 21st Century: Voluntary Development Action and the Global Agenda. West Hartford, CT: Kumarian Press.

- Law, J. 2015. “What’s Wrong with a One-World World?” Distinktion: Journal of Social Theory 16 (1): 126–139. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1600910X.2015.1020066.

- Levien, M. 2018. Dispossession without Development: Land Grabs in Neoliberal India. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Lewis, D. 2017. “Organising and Representing the Poor in a Clientelistic Democracy: The Decline of Radical NGOs in Bangladesh.” The Journal of Development Studies 53 (10): 1545–1567. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2017.1279732.

- Li, T. 2007. The Will to Improve: Governmentality, Development, and the Practice of Politics. Boston, MA: Duke University Press.

- Manji, F., and C. O’Coill. 2002. “The Missionary Position: NGOs and Development in Africa.” International Affairs 78 (3): 567–583. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.00267.

- Marcuse, H. 1964. One-Dimensional Man: Studies in the Ideology of Advanced Industrial Society. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Marcuse, H. 1969. An Essay on Liberation. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Matthews, S. 2017. “Colonised Minds? Post-Development Theory and the Desirability of Development in Africa.” Third World Quarterly 38 (12): 2650–2663. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2017.1279540.

- Mauss, M. 2002 [1925]. The Gift: The Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies. London and New York: Routledge. doi:https://doi.org/10.4324/9781912281008.

- McNeish, J. A. 2017. “A Vote to Derail Extraction: Popular Consultation and Resource Sovereignty in Tolima, Colombia.” Third World Quarterly 38 (5): 1128–1145. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2017.1283980.

- Mohan, G. 2002. “The Disappointments of Civil Society: The Politics of NGO Intervention in Northern Ghana.” Political Geography 21 (1): 125–154. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0962-6298(01)00072-5.

- Mohan, G., and K. Stokke. 2000. “Participatory Development and Empowerment : The Dangers of Localism Angers of Localism.” Third World Quarterly 21 (2): 247–268. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436590050004346.

- Mosse, D. 2004. “Is Good Policy Unimplementable? Reflections on the Ethnography of Aid Policy and Practice.” Development and Change 35 (4): 639–671. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0012-155X.2004.00374.x.

- OECD. 2016. “Fisheries and Aquaculture in Colombia.” http://www.oecd.org/colombia/Fisheries_Colombia_2016.pdf

- Rangan, H. 1996. “From Chipko to Uttaranchal: Development, Environment, and Social Protest.” In Liberation Ecology: Environment, Development, Social Movements, edited by R. Peet and M. Watts, 205–226. London and New York: Routledge.

- Reyes, A. 2009. Guerreros y campesinos: el despojo de la tierra en Colombia. Bogotá: Grupo Editorial Norma.

- Scott, J. C. 1990. “Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts.” New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- Instituto Amazónico de Investigaciones Científicas (Sinchi). 2000. Caquetá: Construcción de un territorio Amazónico en el siglo XX. Bogotá: Instituto Amazónico de Investigaciones Científicas.

- The Economist. 2018. ‘Economies of Scale: Why Asia Is Obsessed with Arowanas–Fishy Business’, The Economist https://www.economist.com/asia/2018/09/13/economies-of-scale-why-asia-is-obsessed-with-arowanas?fsrc=scn/fb/te/bl/ed/economiesofscalewhyasiaisobsessedwitharowanasfishybusiness (accessed 1 November 2021).

- Torpey-Saboe, N. 2015. “Does NGO Presence Decrease Government Spending? A Look at Municipal Spending on Social Services in Brazil.” World Development 74: 479–488. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.06.001.

- Vakil, A. C. 1997. “Confronting the Classification Problem: Toward a Taxonomy of NGOs.” World Development 25 (12): 2057–2070. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(97)00098-3.

- van Zyl, W. H., F. Claeyé, and V. Flambard. 2019. “Money, People or Mission? Accountability in Local and Non-Local NGOs.” Third World Quarterly 40 (1): 53–73. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2018.1535893.

- Vásquez Delgado, T. 2015. Territorios, conflicto armado y política en el Caquetá 1900–2010. Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes.

- Wainwright, J. 2008. “Decolonizing Development.” In Decolonizing Development: Colonial Power and the Maya. Maiden, Oxford and Carlton. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470712955.

- White, S. C. 1999. “NGOs, Civil Society, and the State of Bangladesh: The Politics of Representing the Poor.” Development and Change 30 (2): 307–326. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7660.00119.

- World Bank. 2001. Project Appraisal Document on a Proposed Loan in the Amount of US$32 Million to the Republic of Colombia for a Productive Partnerships Support Project.

- World Bank. 2015. Implementation Completion and Results Report (IBRD-74840) On a Loan in the Amoung of US$30.0 Million to the Republic of Colombia for a Second Rural Productive Partnships Project.

- Ziai, A. 2017. “‘I Am Not a Post-Developmentalist, but…’ the Influence of Post-Development on Development Studies.” Third World Quarterly 38 (12): 2719–2734. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2017.1328981.