Abstract

This paper analyses how affect and emotions are activated and embodied by the state in post-disaster rebuilding. It focuses on the reconstruction of Tacloban City, Philippines, which was devastated by typhoon Yolanda in 2013. I introduce the concept of benevolent discipline to characterise a mode of governing that is animated by the state’s narratives and performances of ‘benevolence’ as a way of regulating the conduct of constituents towards its aspirations for recovery. I show how the discourse of safety – used to justify the relocation of informal settlers from the city’s danger zones – coalesces with disciplinary techniques targeting the affective life of the urban poor to produce ‘governable’ subjects for the reconstructed city. I show that the state’s altruistic performances in this regard and the mobilisation of affect and emotions constitute mechanisms of power that serve to dispossess and marginalise displaced communities. I argue that affect and emotions play a critical role in the everyday experiences of recovery. A focus on affective dimensions of post-disaster governance helps expose the potentialities of power previously obscured in studies of disaster reconstruction.

Introduction

In November 2013, typhoon Yolanda (internationally known as Haiyan) struck the Philippines. Recognised as the most powerful storm to make landfall on record (Bankoff and Borrinaga Citation2016; Mullen Citation2013), Yolanda devastated central Philippines: there were over 6000 fatalities, a million homes destroyed, and about four million displaced (NDRRMC Citation2013). Tacloban, a highly urbanised city populated by over 200,000 (Ong et al. Citation2016), bore its brunt. Storm surges up to seven metres (Jenner Citation2013) destroyed settlements and infrastructure along the coast, killing thousands mostly from urban poor communities. Following this catastrophe, a dream to rebuild Tacloban as a ‘model resilient city’ (TACDEV Citation2014) was galvanised, encapsulated by the slogan Diri la bangon – better! (Not only to recover – [but be] better!).

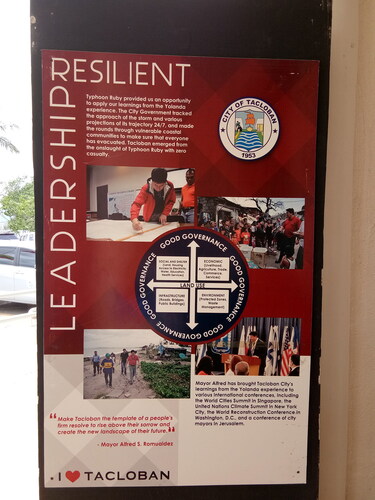

When I first visited the Tacloban City Hall in 2017 to commence research on post-Yolanda reconstruction, I noticed posters plastered across the entrance. These communicated the new vision of post-Yolanda Tacloban: ‘to become resilient, liveable, and vibrant’. One poster provided a master plan for reconstruction (), showcasing modern infrastructure. Another highlighted ‘Resilient Leadership’ (), showing the city mayor speaking publicly, interacting with ordinary citizens and personally visiting coastal areas labelled as ‘danger zones’. The bottom of the poster reads: ‘Make Tacloban the template of a people’s resolve to rise above their sorrow and create the new landscape of their future’.

I was initially struck by the discourse of resilience pervading the narratives of reconstruction. Yet after many conversations with city officials and community members – who often spoke about their encounters with each other in affective terms, and who responded to reconstruction plans, programmes and their representations (eg warning signs, maps and posters) with emotional intensity – I would go back to these posters and see something more.

Along with the discourse of ‘resilient’ recovery, the posters depicted the state as embodied, tangible and outwardly ‘benevolent’, especially towards people whom it considered ‘vulnerable’. This state seemingly recognised people’s ‘sorrows’ and framed rebuilding as an act of collectively ‘rising above’ these sorrows. I realised that the affective qualities displayed by the state here were not simply epiphenomenal to the politics of reconstruction – but rather lay at the heart of it.

Following this observation, this paper analyses how affect and emotions are activated and embodied by the state in rebuilding post-Yolanda Tacloban. Instead of seeing the state as a disembodied entity with rational governing practices, I present it as an active ‘social subject’ (Laszczkowski and Reeves Citation2015; Aretxaga Citation2003) intimately implicated and constantly encountered in the ‘minute texture of everyday life’ (Gupta Citation2012, 75). On one hand, it discharged its duties through bureaucratic processes; on the other, it demonstrated the capability to harbour desires, and to elicit and inculcate emotions among those it governed and endeavoured to make ‘better’. I argue that these qualities play a critical role in the everyday experiences of recovery. A focus on such qualities helps expose the potentialities of power previously obscured in disaster reconstruction studies (see Barrios Citation2017).

Inspired by Foucault’s ideas on governmentality and disciplinary power (1995, 1991), I introduce the concept of benevolent discipline to characterise a mode of governing animated by the state’s narratives and performances of ‘benevolence’ as a way of regulating its constituents’ thoughts, behaviours and feelings towards visions and strategies for disaster recovery. The term ‘benevolence’ here refers to a mechanism of power activated through the appropriation of care in the state’s governing practices, embedded in affective relations. I demonstrate how the state ‘acquires a tangible, affective, and spatial reality’ (Laszczkowski and Reeves Citation2015, 6) to move people towards certain subjective, affective and ethical formations. I argue that benevolent discipline is a novel way of characterising post-disaster governance. It shows how the rhetoric of altruism and the mobilisation of affect coalesce and consequently act as mechanisms of dispossession and marginalisation (see Alvarez Citation2019).

Critical scholars use the lens of governmentality to demonstrate how states manage populations affected by disasters (eg Ghosh and Boyd Citation2019; Sökefeld Citation2020; Hedman Citation2009). They reveal how reconstruction is often legitimated by discourses of risk, resilience, and (modernist) development with a state that ‘governs from a distance’ (Lawrence and Wiebe Citation2018; Rose Citation2000, Citation1999). Benevolent discipline extends understandings of governmentality by showing how post-disaster governance involves the management not only of movement, activities, and spatial arrangements of the body politic, but also the ‘management of the heart’ (Rudnyckyj Citation2011) – that is, the cultivation of affective responses to visions and initiatives for recovery (Barrios Citation2017). Moreover, benevolent discipline offers a reconceptualisation of conventional understandings of the state. While the state in its multiple manifestations may indeed govern from a distance, it is also ‘intimately engaged’ in, and itself exudes, affective qualities (High Citation2014).

With the increasing visibility of disasters globally, managing and reducing their risks as well as ‘building back better’ from them have generated growing attention. Indeed, reconstruction efforts cannot be disentangled from the project of, or from forces that shape, development (Blaikie et al. Citation2004; Collins Citation2009; Pelling Citation2003). This paper contributes to this special issue on Emotions, Affect and Power in Development Studies by showing how the inculcation of ‘biopolitical affections’ (Barrios Citation2017) is a critical part of governing. While illuminating processes of producing the subjects of development (ie disaster survivors), it also demonstrates how disciplinary processes create affective frictions between the state and displaced communities that generate potentials for different practices of recovery.

Below, I first present my methodology. Next, I review the literature regarding how the state governs and how affect is a critical dimension of post-disaster governance. Focusing on the case of Tacloban, I show how benevolent discipline is enacted by the state through the agents of the city government, and situate the discussion within the historical affective relations between the state and the informal settlers who are the objects of state ‘benevolence’. I highlight how the construction of benevolence is framed by the discourse of safety, employed as a rationale for relocating informal settlers from coastal areas to the city’s northern fringes. I then identify mechanisms employed for ‘disciplining’ affective life – technologies that amplified trauma and loss, and those that generated desires and aspirations along the state’s modernist visions for recovery. Finally, I show how dissonances between prescribed visions for recovery and survivors’ embodied experiences may inspire different practices of recovery.

Methodology

My interest in post-Yolanda reconstruction stemmed from personal experience of the storm and subsequent involvement in disaster-response initiatives. Having worked for over 15 years with grassroots organisations, I was motivated to better understand disaster recovery from the standpoint of marginalised groups often excluded from decision-making regarding their own lives after a disaster. My involvement in post-Yolanda response made me reflect on the complexities of reconstruction and the negotiations between continuity and change, leading me to pursue this study.

My analysis draws on fieldwork conducted over 6 months between 2017 and 2018 in Tacloban as part of a PhD project that examined post-Yolanda reconstruction through women’s eyes. I observed government activities, official meetings and community-based activities. I interviewed 22 key informants: local officials, social workers, barangay (village) leaders, government agents and representatives of non-governmental organisations. I also reviewed reconstruction plans, policies and reports.

As my primary research approach, I employed a feminist method called PhotoKwento (telling stories with photographs) involving the use of participant-generated images in interviews and co-constructing narratives of recovery. This entailed having a group of women in researched communities take photographs of their everyday lives after Yolanda and collaboratively put together a photo album representing their experiences. This album was used as a tool to interview other women (not involved in producing photographs) in selected study sites. Hence, instead of employing conventional word-based instruments, photographs were used to prompt one-on-one conversations with women regarding their experiences of disaster recovery (see Alburo-Cañete (Citation2021) for a full description). Studies have shown that using images in research aids in capturing the complexities of human experiences including embodied practices and emotions (Bunster and Chaney Citation1989; Harper Citation2002; Alburo-Cañete Citation2021). In adherence to ethical commitments in feminist research, PhotoKwento aimed to enable co-production of knowledge with study participants.

Using feminist standpoint theory, women’s narratives were regarded as a starting point for investigating organised practices through which disaster-affected populations were being governed. My interest, therefore, lay not only in revealing how women experienced recovery but also, starting from women’s embodied knowledge and practices, in what one might learn (or need to unlearn) from the ways that communities are ‘rebuilt’ after a disaster. As I highlight elsewhere (Alburo-Cañete Citation2021, 891–892), the research objective was ‘not to generalise about the group of women interviewed’ but rather ‘to analyse their diverse narratives so as to uncover and examine the social–political processes embedded in disaster reconstruction that produce generalising effects’ (The emphasis is in the original).

PhotoKwento involved 42 womenFootnote1 from three resettlement communities: Ridge View Park, Cawayanville and Pope Francis Village.Footnote2 They were informal settlers displaced by the storm surges. Participant selection considered differences such as age, civil status, disability, educational attainment, household headship and sexuality.

The data collected – interview transcripts, documents and field notes – were coded and categorised thematically for data interpretation. Although my study highlighted women’s narratives of recovery to help us understand broader institutional processes of disaster reconstruction, this paper focuses on the affective governance practices revealed through engagement with field data.

‘Feeling’ like a state

This section reviews the literature on affect and the state that is instructive for framing benevolent discipline. In Affective States, Stoler (Citation2007) challenges the notion of the state as mainly rational and bureaucratically driven, arguing that such ‘political rationalities’ are in fact grounded in the management of affect. She compels us to rethink conceptions of the emotively neutral state and instead recognise how state bureaucracies function through the production and circulation of emotions – fear, disgust, hope, pride, etc. As Gupta (Citation2012, 113) affirms, ‘affect needs to be seen as one of the constitutive conditions of state formation’ given the extent to which emotions are ‘embedded in the narratives and actions’ of the state through its various agents. Here I regard the state not as a coherent entity (Gupta Citation2012; Navaro-Yashin Citation2012) but as an assemblage of institutions, processes and (embodied) practices (Trouillot Citation2001) working at different levels, and reified in and through everyday encounters ‘between citizens, state agents, and the dispersed material traces of state power’ (Laszczkowski and Reeves Citation2015, 3).

But what is affect, and how is it here associated with ‘emotion’? Affect is sometimes regarded as an unqualified ‘pre-social’ intensity felt by the body but not necessarily recognised, articulated or named. In contrast, emotion is understood as an intensity with subjective content and brought into the ambit of the social – feelings like love, happiness or grief (Massumi Citation1995; Thrift Citation2008). Drawing from feminist theory, however, I resist the tendency to view affect and emotion in a dualistic way. Rather, I draw insight from Ahmed’s (Citation2014, 210) analogy of the (yolk and white of an) egg: ‘That they can be separated, does not mean that they are separate’. Thus, affect here is the embodied, sensorial way of being produced in and through human practices as well as within human (and more-than-human) interactions (see Navaro-Yashin Citation2012). Emotion is an ‘affective experience’ which is narrativised by people within a particular social-cultural milieu (Barrios Citation2017). Affect, then, is not disentangled from emotion and the creation of meaning (or discourse), nor from its relations to social and non-human environments.

Post-disaster situations are undeniably affectively charged. In various experiences, it is not uncommon for states to assume a posturing of care for affected populations, and invoke solidarity in shared suffering and hopes for recovery – even if such posturing has been challenged by the very ‘objects’ of the state’s affections (see Parson Citation2016; Schuller Citation2016; Alvarez Citation2019). To explore the affective dimensions of state practice in such situations, I set out three interrelated ways of thinking about the state’s affective qualities that inform my conceptualisation of benevolent discipline.

Affect as the state’s object-target

In Encountering Affect, Anderson (Citation2014) draws on Michel Foucault’s concept of apparatus – a ‘heterogenous ensemble’ of discursive and non-discursive elements, ie built forms, institutions, laws, administrative processes, statistics, maps, speeches, etc. – to demonstrate how affective life is dynamically related to diverse power modalities. Anderson presents affect as an object-target of such apparatuses, with affective life being an object of power and a target for intervention.

Linking affect as object-target to state practices in disaster contexts, we find that eliciting specific forms of emotions and affective responses towards recovery and reconstruction projects can be a powerful mode of governing. Two examples demonstrate this point. In Capitalizing on Catastrophe, Alex de Waal (Citation2008, x) observes, ‘[w]henever a community is “reconstructed” after a disaster, it is a chance for a bureaucracy to register people, and bring them more directly into its embrace’. Registering ‘beneficiaries’ for government aid exemplifies what Scott (Citation1998) refers to as legibility practices – ‘rendering technical’ (Li Citation2007) aspects of life in order to make them calculable, measurable and manageable. However, registration as a legibility practice can also engender feelings of hope and gratitude – or, conversely, anxiety – among survivors whose access to much-needed aid depends on their being listed as beneficiaries (see also Ong, Flores, and Combinido Citation2015 on gratitude in the Yolanda context). Capitalising on such feelings grants the state power to demand compliance to conditions for becoming a ‘beneficiary’.

The second example demonstrates the relationship between affect and planning. In a study of recovery planning in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, Barrios (Citation2017) explores how planners sought to persuade residents to accept plans for reconstructing a specific area of the city as a new space for capital investment. The plans used bright colours and texture – a boulevard lined with trees, cafes, shops and grocery stores suggesting a cosmopolitan lifestyle – to elicit responses of pleasure and desire among residents. Thus, by appropriating visual and tactile aesthetics, planners aimed to generate affective investments in the vision for reconstruction to lend it legitimacy.

These examples show that recovery and reconstruction activities, while entrenched in administrative processes, are grounded in the careful cultivation, manipulation and re-patterning of emotions (Barrios Citation2017). This demonstrates a facet of the ‘affective state’ which regards affects and emotions as object-targets of its power to attain specific goals – such as advancing a modernist/capitalist agenda through disaster reconstruction as in the case of New Orleans and elsewhere (see Klein Citation2007).

The state as an object of affect and emotions

Recent studies explore the state itself as a site of affective investments (Laszczkowski and Reeves Citation2015). The yearning for a ‘good paternalistic state’ (Aretxaga Citation2003, 396), caring and feeling responsible for citizens’ welfare, is often contrasted with narratives of state corruption, abandonment, neglect and terror (Aretxaga Citation2000; Davies Citation2013; Gupta Citation2012; High Citation2014). Ideals of how the state should be generate a range of emotions – often ambivalent, many intense – that animate people’s relations with the state. In disaster contexts, the role of the state as primary responder, relief provider and source of refuge cannot be understated.

Examining the aftermath of the 2010 Chilean earthquake, for example, Parson (Citation2016) narrates that low-income communities, dissatisfied over the state’s inability to provide for their needs, labelled their conditions as ‘mistreatment’ and such apparent neglect a ‘moral earthquake’ (Parson Citation2016, 101). This discontent sparked a movement to compel the state to provide dignified housing and other services to displaced communities. Parson’s findings resonate with my own research in Iligan City, Philippines, among people in emergency camps following Tropical Storm Washi in 2012. Feelings of resentment were exhibited towards the state over the perceived failure to fast-track provision of permanent shelters and to address harsh conditions in emergency camps (Alburo-Cañete Citation2014).

Above, the state is at the receiving end of people’s (adverse) sentiments. However, the state can become an object simultaneously of ‘mixed emotions’ (Steinmuller Citation2015) like resentment and hope (Curato Citation2016; High Citation2014; Jansen Citation2014). Underscored here is the importance of the state’s ability to project a posturing of care especially in disaster contexts – and to have that posturing affectively resonate with people – to maintain the legitimacy of its operations. While legitimacy is not solely contingent on the state’s ability to perform ‘care’ – indeed, others have addressed crises with abandonment and neglect (see Davies Citation2013 on Chernobyl) – affective investments in the state aids in legitimising recovery initiatives.

The state as affective social subject

While the state is an object of affect and governs through interventions targeting affective life, it also has a subjective life. Indeed, having an affective relationship with people means that the state materialises and ‘acts’ in multiple and often intimate ways in everyday life (Laszczkowski and Reeves Citation2015). Although the impact of state power is uneven, locally such power is encountered ‘close to the skin’ and ‘embodied in well-known local officials’ and state agents operating on the ground (Aretxaga Citation2003, 396; see also Jakimow Citation2018). Thus the state acquires a tangible character, unlocatable at any single site of power but actively ever-present and recognisable through its multiple effects (Trouillot Citation2001). As a ‘phenomenological reality’ (Aretxaga Citation2003), the state impresses upon bodies various affective energies and discursive practices, as well as enactments of its own fantasies and desires (Siegel Citation1998), as it is reified in everyday encounters and discourse (Navaro-Yashin Citation2002).

This ‘subjective dynamic’ (Aretxaga Citation2003) between people and those embodying the state becomes apparent in disaster settings. Loss and devastation give way to heightened affective engagements with the state and bring to life powerful encounters in determining ways forward and negotiating – figuratively and literally – life and death. As an affective social subject, the state often displays contradictory qualities – coercive and ‘caring’, cruel and benevolent – played out in everyday engagements with people, aid organisations and other social institutions. The state can be chastised for ‘inattentiveness’ and incompetence in managing emergency situations, or praised for its ‘sympathy’ towards disaster survivors. These engagements eventually shape state responses to such situations and its (re)positioning. State agents can also act out feelings of hope, frustration, pity or contempt while performing their roles. Thus, the state possesses the capacity to affect as well as the susceptibility to be affected (Anderson Citation2014; Jakimow Citation2020).

Consideration of the state’s affective qualities tempers conceptualisations of ‘statecraft’ that construct the state as an unfeeling ‘machine’ which simply manipulates people to achieve its aims for improvement (see Kapoor Citation2017). In Tania Li’s (Citation2007, 5) account of encounters with officials, bureaucrats and other development actors (or ‘trustees’), she observes how intentions are often ‘benevolent’, ‘utopian’ and concerned with achieving a ‘higher good’. A ‘trustee’, according to Li (Citation2007, 4), is defined by ‘the claim to know how others should live, what is best for them, to know what they need’. And yet the application of the trustee’s expertise to determine which sorts of lives are worth living is also driven by a desire to make the world better (Li Citation2007), according to specific ways of thinking about ‘improvement’. This reflection demonstrates that (state) power is never impersonal but rather ‘always passionately invested’ (Kapoor Citation2017, 2667). These passions are qualified and politicised through discourse (Navaro-Yashin Citation2012), which in turn generates ‘embodied and sensual effects’ (Aretxaga Citation2003, 403).

The city government of Tacloban, I argue, embodies these affective qualities that enable it to pursue its fantasies of becoming a modern/resilient city. Below, I show how the state, through the local government, casts itself as a ‘benevolent authority’ in carrying out large-scale resettlement. The city government thus invites positive feelings towards itself and the modernist rationalities underpinning its ‘build back better’ reconstruction. The concept of benevolent discipline can help us understand how the plans of carrying out ‘improvements’ greatly involve instituting ways of thinking, feeling and behaving around changes in socio-spatial arrangements and community life. Here, affect and discourse are together mobilised to inscribe state fantasies of resilience, modernity and moral development onto ‘vulnerable’ bodies.

Workings of the ‘benevolent’ state

A city official interviewed in 2017 dwelt on the intractable issue of housing and resettlement of nearly 90,000 people from the coastal areas to Tacloban North. The city government, she said, wanted everyone moved to safer ground. ‘Why did the city decide that?’ I asked. She answered:

Anywhere in the world, there’s no such thing as a safe place. You just have to choose which option is the lesser evil … why is it safe in the North? Because … this is the only area located 10 metres above sea level. Where are these displaced people from? All of them are from coastal areas …. So first of all, you need to know your non-negotiables. Lives are non-negotiable, livelihoods can come later …. People are complaining at the moment because there is still a lack of livelihood [in the north]. But the city is providing them with the support services they need …. You know, the city government had originally intended for that relocation site to be an economic zone. So the city sacrificed [that plan] in order to prioritise resettlement … the city must prioritise protection of people’s lives, protection of people’s properties. (emphasis added)

I then asked, ‘how did you convince people to move?’ She replied, ‘people had just experienced the disaster, they were afraid. We did not have difficulties convincing people to move’.

A striking aspect of that exchange is how the state’s narrative regarding resettlement is imbued with paternalistic hues. Encoded in all the reconstruction and development plans in response to the Yolanda disaster, this narrative highlights the city’s ‘sacrifice’ in prioritising resettlement over the development of an economic zone and articulates a point: that a ‘benevolent’ state was pursuing reconstruction with the ‘best interests’ of its citizens at heart.

This encounter reveals how rebuilding Tacloban is structured by affective engagements between the state and its citizens and is framed by altruistic representations of its disaster reconstruction initiatives. The state can thus manage emotions such as fear and gratitude as a technique and condition for making people comply with its plans for urban re-design.

To understand how benevolent discipline operates, we should view recovery and reconstruction as sites where discursive practices and affective work are constantly performed. These practices aim not simply to rebuild from destruction and govern life after disaster but to produce new life-worlds that alter people’s relation to themselves, others and their environment. Such practices constitute what Foucault (Citation1995, Citation1978) calls disciplinary techniques operating on ‘the capacities and desires of individual bodies’ (Grove Citation2014, 247) in order to shape them into amenable subjects of the new socio-spatial order. Governing such bodies needs the circulation of certain ‘truths’ to set the parameters for thinking and action (Foucault Citation1980). Consequently, the legitimation of truths comes together with managing affective life – mobilising sentiments, ‘educating desires and configuring habits, aspirations and beliefs’ (Li Citation2007, 5) – of those whom the state seeks to ‘improve’. In Tacloban, as demonstrated below, the state operates on affective life and relations as objects of disciplinary actions, and also directs affective attachments to itself by emulating qualities of ‘benevolence’ to sustain legitimacy of its rebuilding efforts.

Thus, ‘rebuilding better’ becomes an effect of embodied meaning-making and of disciplinary techniques. These elevate a form of ‘valued life’ that the state considers productive and desirable (Anderson Citation2012, 30), set in contrast to a devalued form of life countering the state’s logics of resilience-building. The act of disciplining, therefore, requires a referent object, usually ‘defective’ groups regarded as needing correction (Li Citation2007). The discourse of safety employed by the city government involves understanding what constitutes disaster vulnerability and who is considered ‘vulnerable’. In this regard, I show how informal settlers populating Tacloban’s ‘dangerous coasts’ become the objects of benevolent discipline. I then identify mechanisms through which the state governs through affect.

Informal settlers and the city

Tacloban’s central role as an economic hub had produced intense competition for urban space even before the onset of Yolanda (Atienza, Eadie, and Tan-Mullins Citation2019). The city’s rapid urbanisation and the economic opportunities this presented have attracted migrants from neighbouring towns and provinces.

However, the contradiction of unaffordable property values and the need to access centrally located urban space (see Shatkin Citation2004) have resulted in the growth of informal settlements. Although informal settlers and workers are often represented as messy, chaotic and undesirable, they form a vital part of local economies that rely on cheap labour for crucial services. They have formed an ‘ambiguous relation’ with state power through time. On one hand, they are recognised for contributing to the local economy and being a source of electoral votes. On the other, they are often perceived as ‘squatters’, a generalised, undesirable and dangerous ‘other’ (Sibley Citation1995; Kusno Citation2016). This perception is evident in the city’s socio-spatial organisation, wherein such communities often occupy ‘hazard-prone’ spaces least serviced by the state (Atienza, Eadie, and Tan-Mullins Citation2019). Consequently, the city government’s stance towards informal settlers has vacillated in the last few years, before and after Yolanda.

Aspirations of becoming a ‘globally competitive city’ (TCPDO Citation2017) had compelled investment in urban redevelopment and spatial transformations. The creation of the Tacloban City Astrodome, an East-North coastal road, a recreational boardwalk and the expansion of the airport were among Tacloban’s priorities for infrastructure development since the early 2000s. In pursuit of these, however, the city government eventually forged antagonistic relationships with informal settlers who faced eviction because of these projects (Barbosa Citation2009; Japzon Citation2004).

While the city government managed to negotiate with and move some informal settler families to resettlement sites north of the city centre, it could not completely remove urban poor communities from project sites. An anti-demolition alliance among informal settlers resisted relocation (Japzon Citation2004), and evictions sometimes led to violent confrontations, wherein the government forcibly demolished houses (Barbosa Citation2009). During these moments, groups of informal settlers considered government callous and insensitive to their plight (Japzon Citation2004).

The question of relocating informal settlers from coastal areas, then, precedes Yolanda. The premise of urban development did not sit well with communities who faced displacement from their environment, which had constituted their ways of life and identity. Many had relied on the sea for a living, and many more were engaged in waged and informal work nearby. The precarity that such communities faced did not necessarily emanate from living in ‘dangerous’ environments, but from insecure tenurial arrangements, state policies and urban planning rationalities aiming to ‘sweep away the poor’ in favour of ‘development’, a common trend in urban planning practices in the Global South (Watson Citation2009). However, the Yolanda disaster shifted the discourse of relocation-for-development to that of relocation-for-safety, which served to reconfigure affective positionings between the state and informal settlers, as I discuss below.

Framing informality as vulnerability

On the surface, the discourse of safety adheres to universal calls for greater preparedness and precautions in anticipation of natural hazards, especially in the context of climate change (United Nations Citation2015). This is supported by urban planning logics that re-code disaster vulnerabilities into technical spatial frameworks, which categorise areas as ‘safe’ or ‘unsafe’. The Tacloban Recovery and Rehabilitation Plan (TRRP) describes its policy action in Safety of the Population (TACDEV Citation2014, 15):

Inadequate preparation and habitation of vulnerable areas were the conditions that contributed to the losses in lives and destruction to property when Yolanda hit. Now that the city has a clearer idea of the ‘reach’ and behaviour of a super typhoon, redevelopment policies can thus direct growth to the proven safer (higher) areas of the city. Meanwhile, disaster-resilient rebuilding policies can prescribe the effective architecture and engineering provisions for future construction.

The imperative for moving populations to safety is seen to reduce people’s exposure to natural hazards. The TRRP seems to concern the general city population, but the following passage reveals which populations are to be ushered to safety (TACDEV Citation2014, 8):

Majority of the city’s informal settler families occupy the city’s high risk areas and roughly 10,000 of the totally damaged houses from the typhoon belong to the urban poor. Given the damages and the city’s hazardscape, this plan was formulated taking into account the shelter needs of the survivors as well as their safety from future disasters. (emphasis added)

The concern over moving informal settlers to safety is echoed in other documents developed in response to the impacts of Yolanda, like the Comprehensive Land Use Plan, the City Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Plan and the Tacloban North Integrated Development Plan (CDRRM Council Citation2016; TCPDO Citation2017, Citation2016). These espouse the reduction of informal settlers’ exposure to future risk and, if necessary, sacrifice ‘short-term individual gains’ for ‘long-term city benefits’ (CDRRM Council Citation2016, 79). In short, these assert that while resettlement might produce discomfort, relocation will ultimately be ‘beneficial’ in ensuring citizens’ safety.

Informality of human settlements thus became conflated with highly technical understandings of vulnerability: flimsy housing materials, exposure to hazards, lack of sanitation and of education about hazards. These are identified in Tacloban’s reconstruction and development plans, which present inadequate preparedness, habitation of high-risk areas and the implied insubstantiality of housing materials as reasons for vulnerability. By regarding informality as a form of vulnerability, relocation and regularisation/formalisation of housing, as well as the ‘education’ of informal settlers, became legitimate interventions for disaster risk reduction.

While relocation of urban poor communities in the Philippines is generally laden with stigmatising rhetoric (Ramalho Citation2019), the (overt) pervading narrative in post-Yolanda Tacloban is one of ‘concern’ for safety. The city government has shifted its stance towards these communities from ‘hostile’ to ‘benevolent’. Presenting disaster resettlement as mainly hazard avoidance has served to re-structure affective engagements between the state and displaced/informal communities. As initial displacement after Yolanda was viewed to result from ‘natural’ causes, the safety discourse deflected politically charged notions of resettlement. Resettlement therefore became framed as a compassionate act.Footnote3 This emotive stance is often embedded in the narratives of state agents at the frontline of recovery initiatives. As one barangay (village) official expressed,

their conditions at the relocation sites are nakakaawa [pitiful]. It was better for them when they were still here [in their original community] … but for me, I do not want harm to come to them … I convinced them to relocate because I don’t want [the disaster] to be repeated. I will be haunted by my conscience. So many people died.

I have shown above how the framing of informality-as-vulnerability allowed the state to represent its relationship with informal settlers as benevolent. By focusing on technical aspects of vulnerability, the state, through the discourse of safety, depoliticised the extant insecurities and structural inequalities experienced by informal settlers as they struggled for a place in the city. ‘Building back better’ hence became an opportunity to transform the ‘unruly’ urban poor into governable subjects.

Disciplining affective life

The discourse of safety also aimed to alter people’s relationship to their environment and way of life: the sea no longer seemed a source of life but a bringer of death; houses of ‘light materials’ were no longer regarded as home but as some-thing that could be washed away. Re-coding environments and objects as ‘dangerous’ or ‘safe’ provoked emotional responses that help create risk-averse subjects.

Reworking values and sentiments, however, requires strategies and tools that allow the exercise of disciplinary power. I categorise affective technologies along two main themes: risk-aversive and aspirational. The risk-aversive are those that elicit and reinforce negative emotive responses towards conditions, places and objects deemed ‘dangerous’; the aspirational cultivate desires for a valued kind of life and conditions for living.

Risk-aversive affective technologies

I highlight here three risk-aversive technologies: spatial classification, hazard maps and storm-surge warning signs. All capitalise on fear, trauma and insecurity, and aim to modify people’s attachments to their environment and validate the need for relocation.

Spatial classifications have a powerful effect on how people connect with their environment. Labels attached to coastal areas affected by the storm surges evolved throughout the process of post-disaster recovery. ‘No Build Zone’ was first used, and later ‘No Dwelling Zone’ to allow building of commercial and tourism infrastructures in ‘risk-prone’ coastal areas (Yee Citation2017). However, in my interviews with officials, the term ‘danger zone’ was more widely employed.Footnote4 Observably, resettled survivors continued to talk about their fear of storm surges, adding the term ‘danger zone’ to their everyday vocabulary. ‘After Yolanda, I had a difficult time sleeping while I was staying at the danger zone, especially when it rained and the winds were strong. I still remember the water rising and sweeping away our home’, a study participant said.

Current analyses of the application of classifications such as No Build Zone or No Dwelling Zone focus on their political, economic and territorial/legal implications (Fitzpatrick and Compton Citation2018; Yee Citation2017). However, not much attention is paid to how emotions engendered by the language used in such classifications serve to diminish or lend potency to state interventions and animate decisions regarding relocation. The prohibitive language of No Build or No Dwelling zones elicited emotive responses that moved people to defend their ‘home’, but shifting to ‘danger zone’ impressed the need to seek safety for their own good. After all, it was supposedly nature, and not the state, that had caused their displacement. The term ‘danger’, then, activated emotions of fear and insecurity which bore upon people’s settlement decisions after the disaster.

Supporting danger-zone classification is the production of hazard maps, which graphically represent hazards affecting a specific geographic area. Levels of risk are represented through colours, with red often used for high-risk areas. After Yolanda, the state invested in re-assessing disaster risks of storm surges, and in updating existing hazard maps, which have been disseminated through government websites and posters in public areas.

Maps can define categories and boundaries of spaces, their respective utility and, consequently, the people and things therein. However, as Navaro-Yashin (Citation2012) argues, such documents are not ideologically and emotively neutral objects but can have affective relationships with people. What effect could a hazard map – which depicts one’s home environment in bright red – have on communities who recently survived a deluge? Drawing on recent trauma and continuing fear of another typhoon, hazard maps operate at both cognitive and affective levels by enabling people to visualise and thereby re-live emotions around residing in a ‘danger zone’.

Reinforcing spatial classifications and hazard maps, storm-surge warning signs are posted across danger zones (see ), constant reminders of danger that help create an atmosphere of insecurity and fear by driving home the point: this is not a safe place to live in. A woman I interviewed said, ‘We really needed to move because, as you see [pointing to the photo below], it is not a safe place … I liked living there, but I am also afraid to go back’.

Figure 3. Storm surge warning sign in the danger zone. Image by a PhotoKwento participant, used with permission.

Risk-aversive affective technologies, then, functioned to ‘fold in’ people’s memories of trauma and devastating experiences of loss during typhoon Yolanda to their ‘everyday socioecological relations’ (Grove Citation2014, 248). As the government told occupants of the dangers of staying put, it capitalised on the fear of ‘another Yolanda’ and utilised expert knowledge to affirm the need to relocate, such that moving to ‘safer ground’ sounded both rational and appealing. However, producing risk-averse subjects only partially fulfils the objectives of benevolent discipline. To make citizens ‘resilient’, their aspirations must be moulded towards specific visions and embodiments of a ‘better’ post-Yolanda future.

Aspirational affective technologies

While risk-aversive technologies re-inscribed environments as sites of tragedy and potential future threat, aspirational technologies facilitated the investment of hope and desire in places, objects and ways of being valued by the state. Here, two mechanisms figured prominently in my study: infrastructure and values formation programmes.

The rapid rise of concrete infrastructure all over Tacloban stirred feelings of pride and hope among study participants that Tacloban had indeed recovered and become ‘better’. ‘What changes have you seen in Tacloban since Yolanda?,’ I asked. To this, one replied, ‘there are many improvements now in Tacloban … wider roads, two Robinsons malls, Savemore and PureGold [supermarkets], and many more buildings and hotels. It’s cleaner, it’s now better’. Many others agreed that Tacloban was ‘progressing’. Although they rarely encountered sites of ‘improvements’, being mainly confined to remote resettlement sites (and such establishments catered to a different class of clientele), witnessing these ‘concrete’ transformations nonetheless evoked a sense of pleasure.

The power of infrastructure to generate desires for modernity and ‘progress’ (Harvey Citation2010; Archambault Citation2018) is best demonstrated in the provision of balay nga bato (concrete houses) by the government and other humanitarian/non-government organisations to displaced families. Balay nga bato was presented as more ‘resilient’ and typhoon-resistant than informal structures. However, beyond acquiring ‘resilient’ dwelling, many participants admitted to being at first excited to live in a ‘subdivision-style’ settlement because it represented a modern lifestyle. Prior to resettlement, they were allowed to tour the sites and view a model house. They were promised indoor plumbing, private toilets and individual electrical connection, as well as access to transportation ().

Figure 4. A view of Cawayanville, a resettlement site in Barangay Cawayan, Tacloban North. Image by a PhotoKwento participant, used with permission.

Hence, along with the development of aversive feelings is the redirection of emotional attachments towards orderly, standardised houses. Although many expectations regarding the housing projects would be unmet, the provision of concrete houses had intimately woven together the discourse of safety, the narrative of the state’s benevolence and fantasies of modernity. One official commented, ‘many of these people have never lived in a concrete house. They have never even had houses of their own. They are very lucky to be provided houses by the government’.

To facilitate resettlement, housing ‘beneficiaries’ had to undergo social preparation for life in relocation sites. Fundamental to preparation was the values formation programme. Under it, beneficiaries attended lecture-seminars aimed at ‘changing their mindsets’ and teaching them how to be ‘better’ members of their new communities. Maintaining amity and cooperation among neighbours, cleanliness of surroundings and compliance with rules were emphasised. A study participant stated, ‘we were taught to leave our old selves behind … we should not bring our negative attitudes and practices to our new communities’.

Housing beneficiaries were presumed to need to learn a particular ethic emphasising responsibility for self and community. ‘Squatters’ were often described by officials as having unsanitary habits and unsuitable social decorum. Thus, values formation operated along two affective and moral registers. Not only did it instil the desire to become a ‘good’, ‘responsible’ and ‘hygienic’ citizen; it also helped circulate aversion to the idea of ‘who they used to be’. The programme extended to Family Development Sessions (FDS), a monthly seminar for beneficiaries of the government’s conditional cash transfer programmes, the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino and the Modified Conditional Cash Transfer (MCCT); and community-based women’s seminars in resettlement areas.

Thus, affective technologies worked in two distinctive ways: instilling risk-aversive dispositions and shaping aspirations for a valued form of life. These technologies, however, are not mutually exclusive, as fostering aversions to forms of risk can simultaneously be activated by the inculcation of certain types of aspirations, and vice versa.

With these technologies, framed and employed through the rhetoric of ‘saving lives’, the state has mobilised affect and emotions to produce governable subjects. However, governmental practices are never totalising. As argued in the introduction to this special issue, affect and emotions may augment the state’s power, but these are not reducible to power’s effects. Thus, the final section of this paper shows how affective engagements between the state and urban poor communities have also resulted in affective frictions when aspirations, desires and feelings of recovery do not resonate neatly with dominant prescriptions for ‘resilient’ post-disaster futures.

Affective frictions

Friction, a metaphor from Tsing (Citation2005), produces contingent and unpredictable movement, responses and actions that allow generative moments belying people’s ‘docility’. In Tacloban, attempts to mobilise emotions of fear and inculcate aspirations for ‘resilient’ infrastructure have not constantly generated the responses expected.

Despite the promise of a ‘good life’, those resettled faced a harsh reality: lack of livelihoods, long expensive commutes, no running water and the breakdown of community ties. ‘We are always hungry’, said a widowed woman raising four children. ‘We have a concrete house, but we cannot eat it’.

Concrete houses also elicited feelings of loneliness; as one participant said:

I am thankful that we are given a concrete house but [pauses] … I am not happy here. I was happier with my old house … I used to live close to my family and relatives but now we are separated. I feel lonely here.

Housing beneficiaries received housing units at random through lottery, so they were commonly relocated far from kin and former neighbours. This led to the fragmentation of existing social support systems, which are vital for disaster recovery (Oliver-Smith Citation1999; Aldrich Citation2012; Nakagawa and Shaw Citation2004).

Moreover, while many feared another storm surge, they also longed to return to the coastal areas where their livelihoods were rooted and where they had cultivated a sense of place, as one participant expressed:

It is more difficult here in the north …. Livelihood is difficult here. There [referring to coastal area], if we have no food, we can easily get vegetables from our surroundings. But since we came here, it has been very hard. Sometimes we just have to eat salt with our rice. Because we can’t have vegetables grow on concrete.

In many cases, people endeavoured to preserve attachments to normative constructs of modernity and the ‘good life’ regardless of the adverse impacts brought by relocation. However, affective frictions have also spurred actions countering the state’s logics of resettlement. Some survivors established ‘dual residences’ (one at the resettlement site, another at the ‘danger zone’). Reinterpreting the notion of safety, some regarded their concrete houses as ‘evacuation sites’ for use during calamity, preferring to remain at the coast. A few communities refused relocation, saying they feared hunger more than a typhoon.

Hence, notwithstanding this paper’s focus on analysing governing practices of benevolent discipline, we should recognise that people have responded to relocation in different (affective) ways. While many accepted resettlement because of fear and aspirations for modernity and security, others re-appropriated notions of safety and risk, and a few contested resettlement, opting for ways of being that made them feel more at ease.

Conclusion: building back better?

This paper has demonstrated how emotions are mobilised as a means of governing. Focus on the state as an affective social subject rather than as an emotively neutral and rational institution drew attention to a novel mode of governing: benevolent discipline. An analysis of how the city government of Tacloban enacts benevolent discipline reveals how ‘building back better’ is not only a prescription for ‘resilient’ reconstruction and development but also an affectively charged moral endeavour aimed at regulating and reforming the objects of its benevolence.

Analysing post-disaster governance through the lens of benevolent discipline meshes well with critical analyses of the various governmental practices deployed in post-disaster settings seeking to create subjects responsible for their own survival, often underpinned by neoliberal/modernist/capitalist logics and interests (Barrios Citation2016; Bracke Citation2016; Chandler Citation2013; Joseph Citation2013; Klein Citation2007). The precarity, insecurity and vulnerability that characterise experiences of informal settlers are depoliticised by framing resettlement as hazard avoidance coupled with state paternalism. These affective-discursive practices also mask a more insidious side of rebuilding ‘better’: that of dispossesion and the further marginalisation of displaced urban poor communities.

A growing number of critiques have aptly highlighted how Tacloban’s ‘build back better’ reconstruction has in fact increased hardships and disempowerment among survivors (eg Curato and Su Citation2018; Su and Le Dé Citation2020; IBON Foundation Citation2015). My study offers a different dimension for analysis: the central role of affect and emotions in post-disaster governing practices and relations.

The relevance of benevolent discipline in understanding disaster governance extends beyond Tacloban. Across many Philippine cities, we see more evictions of informal settlers in the name of building resilient cities and risk reduction (Alvarez and Cardenas Citation2019; Ramalho Citation2019). Resonating with my findings, a pattern has also emerged: evictions are being framed as an act of state benevolence (Alvarez Citation2019). Rather than dismiss such performances of care and compassion as mere rhetoric, it is more productive to take seriously how the circulation of affect and emotion in these instances shapes engagements and encounters between the state and informal settlers. As argued earlier, a focus on affect and emotion helps us rethink the nature and operation of power. By using the notion of benevolent discipline, we can gain more ‘textured’ insights regarding how such power operates and how it might be disrupted or transformed.

Acknowledgements

I thank Associate Prof. Tanya Jakimow, Prof. Anthony Zwi and Dr Kim Spurway for their guidance throughout my research and in the writing of this manuscript. Moreover, I thank Dr Erlinda Alburo for valuable inputs on an earlier draft. I acknowledge the contributions of Janella Balboa, Pearl Madeloso, Joli Torella, Rey Cruz and Marlon Llovido for their assistance at various stages of my field research. Most importantly, I extend my deepest gratitude to all my study participants for their time, efforts and valuable insights. Lastly, I thank Sarah Homan and the anonymous reviewers for their feedback on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Funding

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kaira Zoe Alburo-Cañete

Kaira Zoe Alburo-Cañete is Postdoctoral Researcher for the Humanitarian Governance Project at the International Institute of Social Studies Erasmus University Rotterdam (2022–2024). She completed her PhD at the University of New South Wales. Her doctoral research critically examined disaster reconstruction in post-Haiyan Tacloban City, Philippines, through women’s eyes and won the UNSW Dean’s Award for Outstanding PhD Thesis.

Notes

1 A minimum sample size of 25–30 is recommended for in-depth qualitative interviews (Dworkin 2012).

2 These sites represented three approaches to housing and resettlement observed in Tacloban: contractor-driven, donor-partnered and community-focused/’people-driven’.

3 This does not imply a lack of resistance to the planned relocation. There was such when the state declared coastal areas ‘No Build Zones’ and barred displaced communities from returning there (see Curato, Ong, and Longboan 2016; Yee Citation2017). Communities also expressed dissatisfaction with conditions in resettlement sites at the time of writing, but the discourse of safety remains a hegemonic justification for relocation.

4 ‘Danger area’ is officially used under the Urban Development and Housing Act of the Philippines.

Bibliography

- Ahmed, S. 2014. The Cultural Politics of Emotion, 204–233. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Alburo-Cañete, K. Z. K. 2014. “Bodies at Risk: “Managing” Sexuality and Reproduction in the Aftermath of Disaster in the Philippines.” Gender, Technology and Development 18 (1): 33–51. doi:10.1177/0971852413515356.

- Alburo-Cañete. K. Z. 2021. “PhotoKwento: Co‐Constructing Women’s Narratives of Disaster Recovery.” Disasters 45 (4): 887–912. doi:10.1111/disa.12448.

- Aldrich, D. P. (2012). Building Resilience : Social Capital in Post-disaster Recovery. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Alvarez, M. K. 2019. “Benevolent Evictions and Cooperative Housing Models in post-Ondoy Manila.” Radical Housing Journal 1: 49–68.

- Alvarez, M. K., and K. Cardenas. 2019. “Evicting Slums, ‘Building Back Better’: Resiliency Revanchism and Disaster Risk Management in Manila.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 43 (2): 227–249. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12757.

- Anderson, B. 2012. “Affect and Biopower: Towards a Politics of Life.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 37 (1): 28–43. doi:10.1111/j.1475-5661.2011.00441.x.

- Anderson, B. 2014. Encountering Affect. London: Routledge.

- Archambault, J. S. (2018) ‘“One Beer, One Block”: Concrete Aspiration and the Stuff of Transformation in a Mozambican Suburb’, Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 24(4), pp. 692–708. doi: 10.1111/1467-9655.12912.

- Aretxaga, B. 2000. “A Fictional Reality: Paramilitary Death Squads and the Construction of State Terror in Spain.” In Death Squad: The Anthropology of State Terror, edited by J. Sluka, 46–69. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Aretxaga, B. 2003. “Maddening States.” Annual Review of Anthropology 32 (1): 393–410. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.32.061002.093341.

- Atienza, M. E., P. Eadie, and M. Tan-Mullins. 2019. Urban Poverty in the Wake of Environmental Disaster: Rehabilitation, Resilience and Typhoon Haiyan (Yolanda). London: Routledge.

- Bankoff, G., and G. E. Borrinaga. 2016. “Whethering the Storm: The Twin Natures of Typhoons Haiyan and Yolanda.” In Contextualizing Disaster, edited by G. Button and M. Schuller, 44–65. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Barbosa, A. 2009. “Urbanization among the Waray Squatters of Tacloban City, Leyte, Philippines.” In Urbanization and Formation of Ethnicity in Southeast Asia, edited by T. Goda, 288. Quezon City: New Day Publishers.

- Barrios, R. E. 2016. “Expert Knowledge and the Ethnography of Disaster Reconstruction.” In Contextualizing Disaster, edited by G. Button and M. Schuller, 134–152. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Barrios, R. E. 2017. Governing Affect: Neoliberalism and Disaster Reconstruction. Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press.

- Blaikie, B., T. Cannon, I. Davis, and P. Wisner. 2004. At Risk: Natural Hazards, People’s Vulnerability and Disasters, 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

- Bracke, S. 2016. “Is the Subaltern Resilient? Notes on Agency and Neoliberal Subjects.” Cultural Studies 30 (5): 839–855. doi:10.1080/09502386.2016.1168115.

- Bunster, X., and E. M. Chaney. 1989. Sellers & Servants: Working Women in Lima, Peru, 217–233. Granby, MA: Burgin & Garvey.

- CDRRM Council 2016. ‘Comprehensive Disaster Risk and Management Plan Tacloban City 2016-2022’, City Government of Tacloban, Tacloban City.

- Chandler, D. 2013. “Resilience Ethics: Responsibility and the Globally Embedded Subject.” Ethics & Global Politics 6 (3): 175–194. doi:10.3402/egp.v6i3.21695.

- Collins, A. 2009. Disaster and Development. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Curato, N. 2016. “Politics of Anxiety, Politics of Hope: Penal Populism and Duterte’s Rise to Power.” Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs 35 (3): 91–109. doi:10.1177/186810341603500305.

- Curato, N., J. C. Ong, and L. Longboan. 2016. Protest as Interruption of the Disaster Imaginary: Overcoming Voice-Denying Rationalities in Post-Haiyan Philippines. in M Rovisco & J Ong (eds), Taking the square: mediated dissent and occupations of public space. 1 edn, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, London, pp. 77–96.

- Curato, N., and Y. Su. 2018. “Build Back Bitter? Five Lessons Five Years after Typhoon Haiyan – New Mandala [WWW Document].” Accessed June 20, 2021. https://www.newmandala.org/build-back-bitter-five-lessons-five-years-after-typhoon-haiyan/

- Davies, T. 2013. “A Visual Geography of Chernobyl: Double Exposure.” International Labor and Working-Class History, 84: 116–139. doi:10.1017/S0147547913000379.

- de Waal, A. 2008. “Foreword.” In Capitalizing on Catastrophe, edited by N. Gunewardena and M. Schuller, ix–xiv. Plymouth, UK: AltaMira Press.

- Dworkin, S. L. 2012. “Sample Size Policy for Qualitative Studies Using in-Depth Interviews.” Archives of Sexual Behavior 41: 1319–1320.

- Fitzpatrick, D., and C. Compton. 2018. “Seeing Like a State: Land Law and Human Mobility after Super Typhoon Haiyan.” New York University Journal of International Law and Politics, 50: 719–787.

- Foucault, M. 1978. The History of Sexuality. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Foucault, M. 1980. Power/Knowledge : Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–1977. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Foucault, M. 1991. “Governmentality.” In The Foucault Effect: Studies in Governmentality, edited by G. Burchell, C. Gordon, and P. Miller, 87–104. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Foucault, M. 1995. Discipline and Punish : The Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage Books.

- Ghosh, A., and E. Boyd. 2019. “Unlocking Knowledge-Policy Action Gaps in Disaster-Recovery-Risk Governance Cycle: A Governmentality Approach.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 39: 1–15.

- Grove, K. 2014. “Agency, Affect, and the Immunological Politics of Disaster Resilience.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 32 (2): 240–256. doi:10.1068/d4813.

- Gupta, A. 2012. Red Tape: Bureaucracy, Structural Violence, and Poverty in India. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Harper, D. 2002. “Talking about Pictures: A Case for Photo Elicitation Talking about Pictures: A Case for Photo Elicitation.” Visual Studies 17: 13–26.

- Harvey, P. (2010) ‘Cementing Relations: The Materiality of Roads and Public Spaces in Provincial Peru’, Social Analysis, 54(2), pp. 28–46. doi:10.3167/sa.2010.540203.

- Hedman, E.-L. E. 2009. “Deconstructing Reconstruction in Post-Tsunami Aceh: Governmentality, Displacement and Politics Deconstructing Reconstruction in Post-Tsunami Aceh: Governmentality, Displacement and Politics.” Oxford Development Studies 37 (1): 63–76. doi:10.1080/13600810802695964.

- High, H. 2014. Fields of Desire: Poverty and Policy in Laos. Singapore: NUS Press.

- IBON Foundation. 2015. Disaster upon Disaster: Lessons beyond Yolanda. Quezon City. Quezon City: IBON Foundation Inc.

- Jakimow, T. 2020. Susceptibility in Development: Micropolitics of Local Development in India and Indonesia. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Jakimow, T. 2018. “The Familiar Face of the State: Affect, Emotion and Citizen Entitlements in Dehradun, India.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 44 (3): 429–446. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12714.

- Jansen, S. 2014. “Hope for/against the State: Gridding in a Besieged Sarajevo Suburb.” Ethnos 79 (2): 238–260. doi:10.1080/00141844.2012.743469.

- Japzon, M. 2004. “Demolitions Threaten Tacloban’s Urban Poor [WWW Document].” Bulatlat.com. Accessed September 30, 2019. https://www.bulatlat.com/news/4-34/4-34-demolitions.html

- Jenner, L. 2013. “Haiyan (Northwestern Pacific Ocean): Evidence of Destruction in Tacloban, Philippines.” https://www.nasa.gov/content/goddard/haiyan-northwestern-pacific-oean/ date accessed: 1 January 2018

- Joseph, J. 2013. “Resilience as Embedded Neoliberalism: A Governmentality Approach.” Resilience 1 (1): 38–52. doi:10.1080/21693293.2013.765741.

- Kapoor, I. 2017. “Cold Critique, Faint Passion, Bleak Future: Post-Development’s Surrender to Global Capitalism.” Third World Quarterly 38 (12): 2664–2683. doi:10.1080/01436597.2017.1334543.

- Klein, N. 2007. The Shock Doctrine : The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. New York: Metropolitan Books/Henry Holt.

- Kusno, A. (2016) ‘The Order of Messiness: Notes from an Indonesian City’, in Messy Urbanism. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, pp. 41–59.

- Laszczkowski, M., and M. Reeves. 2015. “Introduction: Affective States – Entanglements.” Social Analysis 59 (4): 1–14. doi:10.3167/sa.2015.590401.

- Lawrence, J., and S. M. Wiebe, eds. 2018. Biopolitical Disaster. London: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Li, T. 2007. The Will to Improve : Governmentality, Development, and the Practice of Politics. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Massumi, B. 1995. “The Autonomy of Affect.” Cultural Critique 83 (31): 83–109. doi:10.2307/1354446.

- Mullen, J. 2013. “Super Typhoon Haiyan, Strongest Storm of 2013, Hits Philippines [WWW Document].” CNN. Accessed February 1, 2019. http://edition.cnn.com/2013/11/07/world/asia/philippines-typhoon-haiyan/index.html

- Nakagawa, Y. and Shaw, R. (2004) ‘Social Capital: A Missing Link to Disaster Recovery’, International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters, 22(1), pp. 5–34.

- Navaro-Yashin, Y. 2002. Faces of the State : Secularism and Public Life in Turkey. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Navaro-Yashin, Y. 2012. The Make-Believe Space: Affective Geography in a Postwar Polity. Durham: Duke University Press.

- NDRRMC. 2013. “Final Report Re Effects of Typhoon Yolanda (Haiyan).” National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council, Quezon City. URL: http://ndrrmc.gov.ph/attachments/article/1329/FINAL_REPORT_re_Effects_of_Typhoon_YOLANDA_(HAIYAN)_06-09NOV2013.pdf Date accessed: 3 November 2016.

- Oliver-Smith, A. (1999) ‘The Brotherhood of Pain: Theoretical and Applied Perspectives on Post-Disaster Solidarity’, in Oliver-Smith, A. and Hoffman, S. M. (eds) The Angry Earth: Disaster in Antrhopological Perspective. New York: Routledge, pp. 156–172.

- Ong, J. C., J. M. Flores, and P. Combinido. 2015. “Obliged to Be Grateful: How Local Communities Experienced Humanitarian Actors in the Haiyan Response.” Research report, Plan International. URL: https://www.alnap.org/help-library/obliged-to-be-grateful-how-local-communities-experienced-humanitarian-actors-in-the date accessed: 3 November 2016.

- Ong, J. M., M. L. Jamero, M. Esteban, R. Honda, and M. Onuki. 2016. “Challenges in Build-Back-Better Housing Reconstruction Programs for Coastal Disaster Management: Case of Tacloban City, Philippines.” Coastal Engineering Journal 58: 1640010.

- Parson, N. 2016. “Contested Narratives: Challenging the State’s Neoliberal Authority in the Aftermath of the Chilean Earthquake.” In Contextualizing Disaster, edited by G. Button and M. Schuller, 89–111. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Pelling, M. 2003. Natural Disasters and Development in a Globalizing World. London: Routledge.

- Ramalho, J. 2019. “Worlding Aspirations and Resilient Futures: Framings of Risk and Contemporary City-Making in Metro Cebu, the Philippines.” Asia Pacific Viewpoint 60 (1): 24–36. doi:10.1111/apv.12208.

- Rose, N. 1999. Powers of Freedom, Powers of Freedom. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Rose, N. 2000. “Governing Cities, Governing Citizens.” In Democracy, Citizenship, and the City: Rights to the Global City, edited by E. Isin, 95–109. London: Routledge.

- Rudnyckyj, D. 2011. “Circulating Tears and Managing Hearts: Governing through Affect in an Indonesian Steel Factory.” Anthropological Theory 11 (1): 63–87. doi:10.1177/1463499610395444.

- Schuller, M. 2016. ““The Tremors Felt Round the World”: Haiti’s Earthquake as a Global Imagined Community.” In Contextualizing Disaster, edited by G. Button and M. Schuller, 66–88. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Scott, J. 1998. Seeing Like a State : How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Shatkin, G. 2004. “Planning to Forget: Informal Settlements as “Forgotten Places” in Globalising Metro Manila.” Urban Studies 41 (12): 2469–2484. doi:10.1080/00420980412331297636.

- Sibley, D. (1995) Geographies of Exclusion: Society and Difference in the West. London and New York: Routledge.

- Siegel, J. T. 1998. A New Criminal Type in Jakarta : Counter-Revolution Today. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Sökefeld, M. 2020. “The Power of Lists: IDPs and Disaster Governmentality after the Attabad Landslide in Northern Pakistan.” Ethnos, 85: 1–19. doi:10.1080/00141844.2020.1765833.

- Steinmuller, H. 2015. “Father Mao and the Country-Family: Mixed Emotions for Fathers, Officials, and Leaders in China.” Social Analysis: The International Journal of Social and Cultural Practice 59: 1–19.

- Stoler, A. L. 2007. “Affective States.” In A Companion to the Anthropology of Politics, edited by D. Nugent and J. Vincent, 4–20. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

- Su, Y., and L. Le Dé. 2020. “Whose Views Matter in Post-Disaster Recovery? A Case Study of “Build Back Better” in Tacloban City after Typhoon Haiyan.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 51: 101786. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101786.

- TACDEV. 2014. “Tacloban Rehabilitation and Recovery Plan.” Government plan. Tacloba: the City Government of Tacloban, Philippines.

- TCPDO. 2016. “Tacloban North Integrated Development Plan.” Government plan. Tacloban: the City Government of Tacloban, Philippines.

- TCPDO. 2017. “The Comprehensive Land Use Plan Tacloban City 2017-2025.” Government plan. Tacloban: the City Government of Tacloban, Philippines.

- Thrift, N. 2008. Non-Representational Theory: Space, Politics, Affect. London: CRC Press Book. Routledge.

- Trouillot, M.-R. 2001. “The Anthropology of the State in the Age of Globalization: Close Encounters of the Deceptive Kind.” Current Anthropology 42 (1): 125–138. doi:10.1086/318437.

- Tsing, A. L. 2005. Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. http://www.preventionweb.net/files/43291_sendaiframeworkfordrren.pdf date accessed: April 4, 2016.

- United Nations. 2015. “The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030.” http://www.preventionweb.net/files/43291_sendaiframeworkfordrren.pdf date accessed: April 4, 2016.

- Watson, V. 2009. “‘The Planned City Sweeps the Poor Away…’: Urban Planning and 21st Century Urbanisation.” Progress in Planning 72 (3): 151–193. doi:10.1016/j.progress.2009.06.002.

- Yee, D. 2017. “Constructing Reconstruction, Territorializing Risk: Imposing “No-Build Zones” in Post-Disaster Reconstruction in Tacloban City, Philippines.” Critical Asian Studies, 50: 1–19.