Abstract

Across many low- and lower middle-income countries, aid donors are promoting results-based financing approaches as a means to link their funding directly with development outcomes. In this paper, we explore one such approach, the Programme for Results (PforR) financing approach in support of Ethiopia’s large-scale education quality reform. We assess whether the PforR approach is fit for purpose, drawing on interviews with 72 key donor and government stakeholders. Our findings suggest that the ability of the approach to achieve its stated goals of building capacity and strengthening the system for equitable learning is limited in this context. While the approach is helping to reorient attention from inputs to results, questions remain as to whether the focus is on the right results. Our findings highlight the need for the careful design of such approaches that take account of the context including with respect to ensuring that necessary preconditions are in place prior to implementation.

Introduction

In recent times, aid donors have introduced results-based financing approaches as a means of attributing outcomes directly to their funding. Results-based financing broadly refers to ‘…any programme that rewards the delivery of one or more outputs or outcomes by one or more incentives, financial or otherwise, upon verification that the agreed-upon result has actually been delivered…’ (World Bank Citation2015b, 4). One example, which we explore in this paper, is the introduction in 2018 of Programme for Results (PforR) financing led by the World Bank in Ethiopia’s quality education reform. This was in support of the third phase of the government’s General Education Quality Improvement Programme for Equity (GEQIP-E), funded by a consortium of donors and implemented by the government. In contrast to the two previous phases of the programme, where funds were released at the beginning of the programme and the focus was on inputs and processes, the introduction of this new financing tool means that the release of the funds is contingent on the achievement and verification of a predefined set of results. The idea underpinning this new approach is that it can help to strengthen the education system and align stakeholders around the goal of learning. In line with the principles of such results-based financing approaches, this in turn would be expected to help build capacity and deliver results (Holland and Lee Citation2018; World Bank Citation2015b).

A reason for the shift to results-based financing approaches in education is related to the recognition that, in many low- and lower middle-income contexts, enrolment has expanded rapidly but learning outcomes have remained extremely low (UNESCO Citation2014; World Bank Citation2018). This pattern is apparent in Ethiopia, where access to education has increased threefold over the past two and a half decades, yet many students are leaving school without even basic skills in numeracy and literacy, especially those who are most marginalised (Iyer et al. Citation2020; Woldehanna and Gebremedhin Citation2016; Yorke, Rose, and Pankhurst Citation2021). PforR was introduced as part of the GEQIP-E reform for this reason, with the expectation that results would focus on improvement in learning outcomes through the GEQIP-E reform.

Although this is the first time that such an approach has been introduced at scale in Ethiopia’s education system, it has been used at scale in other sectors in the country, such as health and energy. Eleven World Bank programmes using PforR financing are currently in operation in Ethiopia, including GEQIP-E.Footnote1 The approach has also been used in education systems in other sub-Saharan African countries, including the ‘Big Results Now in Education Programme’ in Tanzania initiated in 2013 and, more recently, the ‘Better Education Service Delivery for All’ in Nigeria in 2017. Nevertheless, despite the increased focus on results-based financing approaches in low- and lower middle-income countries, there have been relatively few evaluations of its effectiveness, especially within education systems.

In this paper, we explore the design and uptake of PforR financing at scale within Ethiopia’s education system from the perspectives of government and donor stakeholders, focussing on three research questions:

What led to the introduction of PforR financing as part of the GEQIP-E programme?

What results were identified for linking with payments, and why were these results selected?

How prepared were stakeholders at different levels of the education system for the introduction of PforR?

To respond to these questions, we draw on data collected in 2018 during the first year of the GEQIP-E programme as part of the Research on Improving Systems of Education (RISE) Ethiopia study. This included interviews with 72 government and donor stakeholders. In analysing these data, we utilise the domains of power framework (Hickey and Hossain Citation2019). This provides a conceptual framework for understanding the range of influences on education reforms at different levels of the system. We focus on the role of different stakeholders at the international, national, sub-national and local level in the design, uptake and implementation of this approach.

In the next section we outline perspectives in the existing literature regarding the appropriateness of results-based financing, particularly with respect to PforR. We then discuss the context of Ethiopia’s ongoing education reforms, including the different factors that could have influenced the introduction of PforR financing in the education system in Ethiopia. This sets the context for our analysis of the PforR approach that follows, drawing on data from the interviews with key government and donor stakeholders to respond to the three research questions. We conclude by highlighting key implications for PforR approaches arising from our analysis.

Literature review: the shift to results-based financing

Results-based financing approaches have increasingly been adopted in Ethiopia and other low- and lower middle-income countries in recent times with the overarching aim of linking financing with outcomes. Results-based financing is an umbrella term for a range of related approaches being adopted in different contexts. The intention of some results-based financing approaches is to advance the aid effectiveness of development efforts in delivering sustainable results and contributing to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) through the creation of more equal and empowered partnerships, with a focus on results, inclusive development partnerships, transparency and mutual accountability (GPEDC Citation2016). These approaches have been particularly championed by the World Bank, often with the support of other aid donors (Cormier Citation2016). Specifically, PforR financing is one type of results-based financing that aims to improve the systems for service delivery, with support provided through government systems (Gelb and Hashmi Citation2014). The PforR approach is associated with four objectives: (1) aligning the system around results that matter; (2) ensuring sustained attention to results over time; (3) the use of government systems for implementation to strengthen the system and achieve sustainable results beyond the programme; and (4) incentivising stakeholders to achieve results (Holland and Lee Citation2018).

Promoting aid effectiveness through PforR?

There are mixed views in the literature on the appropriateness of PforR and other related results-based approaches for achieving their intended aims. Some argue that improved incentives, accountability, monitoring and recipient autonomy and discretion will lead to an improvement in results. Others point out that the approaches may undermine the goal of making aid more predictable, with potential adverse consequences for sustained results. Some further suggest that the approaches risk promoting a different type of aid conditionality through the definition of specific goals at the beginning of the programme (Clist Citation2016; Holzapfel and Janus Citation2015; UNESCO Citation2018).

According to the World Bank, PforR programmes have so far been largely successful, and there is now increasing demand from recipient governments to use this approach (World Bank Citation2015a). However, this claim should be considered with caution given that the World Bank has championed the approach. It also has significant influence on the adoption of results-based approaches given the amount of its lending to some countries.

There are relatively few independent evaluations of PforR approaches, including for education specifically, despite its increasing popularity. One evaluation of a pilot programme in education trialled by the UK Department for International Development (now the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO)) in Ethiopia found that it was not possible to detect evidence that the results-based approach improved students’ educational performance based on financing provided for the number of students who sat and passed exams. The evaluation notes that the reasons for this were difficult to identify, but indicated that the approach was not clearly communicated to the regions in time, and that there were problems with the learning outcome measures identified to determine whether results had been achieved (Cambridge Education Citation2015). A recent assessment commissioned by the World Bank of the design, implementation and impact of three different results-based programmes in Tanzania, Mozambique and Nepal concluded that results-based financing is not a magic bullet (Dom et al. Citation2021). The authors offered a number of recommendations including the need for programmes to be embedded within education systems, to be aligned with government priorities and to take account of the broader context.

Aligning the education system around results that matter?

PforR programmes seek to align the system around results that matter and ensure sustained attention to results over time (Holland and Lee Citation2018). The release of funding depends on the achievement and verification of disbursement-linked indicators (DLIs), which are a predefined set of results that vary across different countries and programmes. Consequently, the identification and agreement of results and indicators is seen as a central part of the PforR approach. However, identifying and agreeing on results is not a straightforward process, especially within education systems.

For results-based financing approaches seeking to improve learning outcomes, a fundamental challenge is that there is not a linear link from inputs to outcomes. It may also take a longer time than the period of a programme for interventions to achieve improvements in learning (UNESCO Citation2018).

A wide range of contextual factors beyond the influence of the education system may also influence these efforts. For instance, conflict can have negative effects on education outcomes due to, for example, increasing economic hardships on families. In seeking to improve equity in the education system, there is also a risk of unintended consequences, whereby a focus on narrow indicators and the linking of payments to results endangers the diversion of attention to short-term and more easily attainable results (Clist Citation2016; Clist and Verschoor Citation2014; Holzapfel and Janus Citation2015; UNESCO Citation2018). Within education systems, this could lead to a focus on those who are relatively easy to reach rather than addressing structural challenges within the system that potentially limit education for those who are most marginalised (Holzapfel and Janus Citation2015).

Building capacity and strengthening the education system?

Another feature of PforR programmes is the focus on strengthening the system and incentivising stakeholders to achieve sustainable results (Holland and Lee Citation2018). Accordingly, borrower ownership is a core feature of PforR financing, with programmes intended to be aligned around country needs and contexts and to be country-led (Cormier Citation2016). However, the World Bank still often plays an important and active role at various stages of the process (Cormier Citation2016). While this does not necessarily compromise borrower ownership, the level of genuine ownership of governments might be limited in practice. Beyond the level of influence that the government has in implementing the programme, other system-level challenges that could limit the success of results-based approaches include the availability of timely and quality data and the system-level capacity to achieve results (UNESCO Citation2018).

Having outlined some of the perspectives regarding results-based financing approaches, in the sections that follow we consider the introduction of PforR in Ethiopia’s education system and the factors that may have influenced its introduction and uptake.

The introduction of PforR in Ethiopia’s education system

Over the past 20 years, Ethiopia has experienced a rapid expansion in primary education enrolment (MoE Citation2020). However, improvements in the quality of education have not kept pace with the rapid expansion in access, with progress being slow for girls, students from poor households, children with disabilities, and those living in rural areas, for example (Iyer et al. Citation2020; Woldehanna and Gebremedhin Citation2016; Yorke, Rose, and Pankhurst Citation2021). As a result, many children fail to acquire even basic skills in reading, writing and numeracy when they are in school, while many students leave early, before completing a full cycle of primary education.

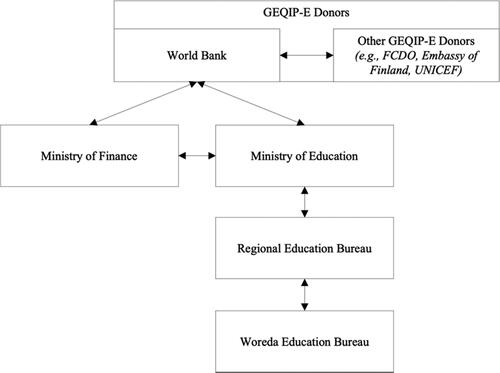

In the context of slow progress towards improving learning outcomes in Ethiopia, GEQIP was introduced in 2008 to improve education quality and learning. GEQIP is closely aligned with the government’s existing plans and policies, notably the government’s Education Sector Development Plans (Yorke, Rose, and Pankhurst Citation2021). GEQIP is a pooled fund supported by a consortium of donors. It is led by the World Bank with funding also from other donors including the FCDO, the Embassy of Finland, the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) and the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). GEQIP is designed in collaboration with government, who is the main implementor. The Ethiopian Ministry of Education (MoE) is responsible for the overall coordination of the programme, while the Ministry of Finance (MoF) is responsible for its financial coordination. Regional and woreda (district) stakeholders are responsible for the co-ordination and implementation of the programme at their respective levels. Asgedom, Carvalho, and Rose (Citation2021) found that the design of the reforms was largely collaborative between the national government and donors, with the national government maintaining control over policy priorities and final design, and international donors influencing specific reform features through financial commitments and technical expertise. As such, the GEQIP programme is intended to provide a harmonised aid framework that has facilitated successful collaboration between donors and the government for almost a decade (World Bank Citation2017).

Over the course of the first two phases of GEQIP (2008–2018), the reform focussed on the provision of inputs and essential resources to the education system (such as improving the supply and deployment of teachers, teacher training, textbook and learning materials and a school grant). However, towards the end of its second phase, government and donors agreed that existing approaches were not achieving their intended results in terms of improved learning, and so a new approach to improving education quality was needed (MoE Citation2015; World Bank Citation2017). PforR was introduced in the third phase (GEQIP-E) with the aim of addressing these identified shortcomings. Its introduction meant that financing would now be disbursed on achievement of an agreed set of results, in contrast to the first two phases of the GEQIP programme when disbursement of financing was made in advance.

Factors influencing the introduction of results-based financing

At the national level, a number of factors are likely to have influenced the introduction of PforR for the GEQIP-E programme. First, education has been a high priority of the government for more than two and a half decades and is seen as playing a central role in achieving the political priorities of the government, including the establishment of peace and stability, reducing poverty, and expanding social and physical infrastructure, and is key to the overall development strategy (Clapham Citation2019; Rekiso Citation2019). For example, rapid economic growth is at the core of the government’s development strategy. Within this context, education is seen as critical for producing the human capital needed to contribute to the labour economy and move the country towards its goal of lower middle-income status by 2025 (Clapham Citation2019; Hagmann and Abbink Citation2011; Woldehanna and Araya Citation2019). Given the importance of education to these wider development objectives, improving the quality of the education system is an important priority.

Second, the need to demonstrate results, which is at the heart of the PforR approach, has great political significance for the government’s priority towards achieving ‘double-digit’ growth (Clapham Citation2018, Citation2019; Hagmann and Abbink Citation2011). While the government are generally open to new ideas, and at times have sought to emulate best practices adopted from other similar contexts, at the same time, policies that do not align with the government’s overall approach are unlikely to be introduced (Clapham Citation2006, Citation2018, Citation2019; Fourie Citation2011; Hagmann and Abbink Citation2011). This is illustrated by the fact that while Ethiopia receives a significant amount of international aid, it has maintained strong negotiating power with donors and aid tends to be closely aligned with Ethiopia’s domestic agenda (Clapham Citation2019; Fantini and Puddu Citation2016; Furtado and Smith Citation2007). Therefore, the fact that the focus on results in the PforR programme links with the government’s overall development approach is important.

Thirdly, the limited capacity of stakeholders working within the education system is identified as a consistent challenge within the education plans and is identified as a barrier to effective service delivery (eg Education Sector Development Plan V, MoE, Citation2015). For this reason, the attention on strengthening the education system and building stakeholder capacity within the PforR programme could be an important consideration in the introduction of this approach.

Research design

Research questions and conceptual framework

Ultimately, a range of factors may have influenced the uptake of the PforR approach in Ethiopia’s national quality education reform. It is therefore important to consider its design and uptake from the perspectives of government and donor stakeholders. To address this, in our analysis, drawing on the perspectives of 72 donor and government stakeholders working at different levels of the system, we explore the following research questions:

What led to the introduction of PforR financing as part of the GEQIP-E programme?

What results were identified for linking with payments, and why were these results selected?

How prepared were stakeholders at different levels of the education system for the introduction of PforR?

Our study is guided by the domains of power framework (Hickey and Hossain Citation2019). This facilitates an analysis to understand the influences on the design and uptake of education reforms. It provides a framing for us to conceptualise the range of stakeholders at different levels of the education system (federal, regional and woreda) and their role in relation to the design and uptake of GEQIP-E reforms. In addition to interaction between different layers of government, we extend the framework to include international actors – given the potential role of donors in the uptake of results-based approaches, notably in this case the World Bank, which plays a key role in these approaches ().

Figure 1. Conceptual framework for analysing the actors and relationships for Programme for Results (PforR) financing in Ethiopia’s General Education Quality Improvement Programme for Equity (GEQIP-E) reform (adapted from Hickey and Hossain Citation2019).

Data

The data analysed in this paper were based on key informant interviews with stakeholders undertaken as part of the RISE Ethiopia research study. As part of this wider study, a system diagnostic of the education system was undertaken. In particular, the system diagnostic included document analysis of government policy and plans and an actor mapping to identify key government and donor stakeholders associated with the ongoing GEQIP reforms. This led to interviews with key stakeholders identified through this process (see Asgedom et al. Citation2019). Donors included those who were providing technical and/or financial assistance to the GEQIP programme at the time of data collection. Government stakeholders included those who were responsible for the overall and financial coordination of the GEQIP programme at the federal level and those who were responsible for coordinating and implementing the programme. The semi-structured interviews examined the roles and responsibilities of the different stakeholders and their views on the design, implementation and impact of the GEIQP-E programme across a range of topics, depending on their areas of expertise. This included their perspectives towards the introduction of PforR, where relevant to their role and responsibilities.

The data analysed in this paper are drawn from interviews with 72 donor and government stakeholders who were informed about the PforR financing modality. These stakeholders included individuals at the federal, regional and woreda level across seven regional states in both rural and urban locations: Addis Ababa, Amhara, Benishangul Gumuz, Oromia, Southern Nations Nationalities and Peoples (SNNP), Somali and Tigray (). The selection of regions was related to the wider RISE Ethiopia research approach (Hoddinot et al. Citation2019).

Table 1. Stakeholders included in the Research for Improving Systems of Education (RISE) Ethiopia system diagnostic.

The interviews were carried out in person by the RISE Ethiopia team using a semi-structured interview schedule. Questions included ones related to the perspectives of interviewees towards the introduction of the PforR approach as part of the GEQIP-E programme, including with respect to its design and uptake. Interviewees were asked to discuss the differences they perceived between the previous and new financing approaches, including what they believed the potential benefits and challenges would be of the PforR approach. Interviews were conducted in the preferred language of the interviewees where possible. All interviews were recorded with permission of the interviewees. They were translated into English where necessary and transcribed.

The data analysis was facilitated by NVivo software. Thematic analysis was used to code the data (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). This allowed a flexible approach for analysing data and involved a process of generating initial codes and themes through an inductive process, with codes and themes emerging from the data. The data were then organised into broader themes guided by the research questions and our conceptual framework described above. Throughout this process we engaged in reflexive dialogue, including thoroughly discussing our findings with the wider team.

Initial findings were presented in a series of workshops to a number of donor and government stakeholders who participated in the data collection. This provided the opportunity to triangulate the findings from the interviews, and to supplement and refine our analysis based on their feedback, thereby increasing the validity of the research findings.

To preserve the interviewees’ anonymity, we removed the names of participants and their specific roles in relation to the GEQIP-E programme, classifying the participants by type (ie government, donor) and the level of the system at which they were working at the time of the interview (ie federal, regional, woreda).

Findings

In this section, we analyse the perspectives of government and donor stakeholders involved in the design and uptake of the GEQIP-E programme with respect to our three research questions. We first consider the factors that led to the introduction and uptake of this approach. Second, we review the results that were identified for linking with payments, and why these results were selected. Thirdly, we explore how prepared stakeholders at different levels of the system were for the introduction of PforR.

The introduction of PforR financing

To respond to the first research question on what led to the introduction of PforR financing as part of the GEQIP-E programme, we consider the perspectives of different stakeholders involved, and assess their level of influence and their motivations for introducing this new approach.

‘A three-way negotiation’

Government and donor stakeholders held different views as to who they believed initiated the shift to PforR in the GEQIP-E programme: donors were more likely to regard the introduction of PforR financing as donor-led, while government stakeholders were more likely to see it as government-led. One federal-level government official described the negotiation process as a ‘three-way negotiation’ among the MoF, MoE and the World Bank. The MoF was understood by a large proportion of donor and government stakeholders as having more influence than the MoE in the negotiation process, even though it was the MoE that would be implementing the programme. One official from the MoF even suggested that they had first recommended the use of PforR financing in the education system:

[The shift to PforR] was a joint decision. Actually I was the one who recommended that. Look, the Ethiopian system, it is more or less based on results in time. You can start from the [Growth and Transformation Plan] … it talks about what we to do in education, in health, it is mostly results in our country.

From the perspectives of MoF officials, they had a strong sense of ownership over the introduction of this new approach and viewed the PforR approach as compatible with the government’s overall development strategy, especially as the government had already been implementing PforR in other sectors.

The need to focus on results

A substantial number of donors and MoE and MoF stakeholders held similar opinions on the importance of focussing on results given that previous phases of the programme had not brought about the desired results. MoE and MoF officials also agreed that this approach was not new for Ethiopia as it has been used within other sectors. Linking with the strong focus of the government on results throughout its policy and plans, a large number of MoE officials described how the introduction of PforR would help to bring about the much-needed shift from inputs to results and therefore help to achieve greater aid effectiveness, as captured by one MoE official:

Since the Millennium Development Goals in 2000, donors are helping developing countries, but the learning outcome is declining. That is just like pouring water into a leaking container. So [donors] are keen to demonstrate the effective use of aid or development assistance. The government of Ethiopia also wanted that, so all are on the same page.

The fact that the introduction of PforR represented a new way of doing things and shifted the focus from inputs to results was therefore an important factor in the uptake of this new approach amongst both donors and government officials. However, some donors discussed how a few MoE officials had to be ‘convinced’ of the need for this new financing tool. According to one donor:

[Donors] took a lot of time to convince [the government] that they have to focus on results … instead of just putting a lot of money in without having the targeted learning outcomes … [donors] are also not happy with putting money in without seeing results. So it is best convincing [the government] that their focus should be accountable, but also pressuring them. Otherwise, we might not be able to support [the programme].

As indicated by the above quote, there was a suggestion that if the government did not agree to this new approach, donors might not be able to continue support the programme. However, it appears that good relationships and the established level of trust between donors and the government were crucial in persuading the government of the need for this new approach, an important factor that has been highlighted by other authors (Gibbs et al. Citation2021). For instance, the fact that some specific donors had longstanding and positive relationships with the government and had already been using results-based approaches in Ethiopia provided greater legitimacy for the introduction of PforR in the education system.

Government ownership and aid coordination

Most donors supported the shift to PforR financing, especially those who had already been implementing results-based approaches in Ethiopia. For donors, in addition to the need to demonstrate results, the ideas of government ownership and aid coordination provided an important rationale for its introduction. In terms of government ownership, the fact that PforR had not changed the content of the GEQIP programme, which continued to be aligned with the government’s on-going Education Sector Development Programme (ESDP), was important for some donors. One donor suggested that the GEQIP-E programme was even more aligned with the ESDP than previous phases of the programme. Another donor, who held less favourable views towards the introduction of PforR financing, explained that even though they did not fully support the introduction of PforR, they would continue to support the programme. The reason given was that the only alternative would be to set up a separate channel of financing, which would lead to aid fragmentation. For this donor, the reason for their support for GEQIP-E was therefore aid coordination through the pooled nature of the programme rather than the introduction of results-based financing.

Summary

Throughout the interviews, the need to demonstrate results emerged as the most important motivation underpinning the introduction of this new approach. This was potentially the case for donors, who otherwise might not be able to continue funding the programme. For government stakeholders, particularly those within the MoF, the focus on results aligned well with the government’s results orientation in other sectors, leading to a strong sense of government ownership. In ‘convincing’ stakeholders who were less favourable towards this new approach, the established level of trust between donors and government stakeholders was important.

While there was a suggestion that some donors could not fund the programme without this focus on results, it is unlikely that this new approach would have been introduced without the support of the MoF – the most influential government stakeholder in the negotiation process. As other authors have noted in the context of Ethiopia, the government retains strong negotiating power with donors, which means that programmes that are not aligned with the government’s priorities do not get implemented (Clapham Citation2018, Citation2019; Hagmann and Abbink Citation2011). At the same time, while stakeholders within the MoF were found to have a significant level of influence in the uptake of PforR financing within the education system, it is important to recognise that they may be less familiar with what is needed to strengthen the education system and improve learning.

Focussing on the right results?

The PforR approach seeks to align the system around results that matter and ensure sustained attention to results over time (Holland and Lee Citation2018). In this regard, we now turn to answering the question of what results were identified to be linked with payments, and why these results were selected.

Identifying indicators for measuring results

To identify whether results have been achieved, PforR approaches commonly include DLIs and key performance indicators (KPIs) linked with identified results areas (RAs). Those identified for the GEQIP-E programme are included in the World Bank Program Appraisal Document (World Bank Citation2018).

While the intention of GEQIP-E is to shift the focus from access and inputs to results associated with learning outcomes, the indicators selected overall do not fully reflect this shift. Notably, only 40% of the financing is linked to improved quality (RA3). The KPIs associated with learning for RA3 are related to academic outcomes in grades 2 and 8 (the latter being the final grade of primary school). The focus is also only on specific schools that have been identified as part of the GEQIP-E process to receive enhanced support in the first phase of the programme. There are only around 2000 of these ‘Phase 1 schools’,Footnote2 out of a total of over 37,000 schools nationwide. In this regard, donors viewed some indicators as inconsistent with the overall objectives of the GEQIP-E programme. For example, one donor suggested that the indicators used to measure progress in learning were not ambitious enough:

Perhaps because of that we feel that the [indicators] are a bit soft, they are not as hard on learning. It is more to do with process. The danger is that if you make if too hard then you might set up for failure.

However, as acknowledged by this donor, a competing concern was that if the targets were too hard then this might set the programme up for failure.

In relation to equity, which is also a core focus of GEQIP-E, all the relevant KPIs are disaggregated by gender. There is also an explicit focus on equity in RA2. However, this focus is only on gender parity in educational access (not on learning outcomes) and is limited to specific regions. Disaggregating the indicators only by gender overlooks other important markers of difference, notably disability, which is one of the core areas of focus of GEQIP-E. In addition, it does not link with progress in narrowing gaps by location or income status, which remain wide for both access and learning – and which interact with gender. While this disaggregation could be missing due to the lack of reliable data in these areas, it might lead to a focus on those who are relatively easier to reach given the link with payments. Therefore, those who are most marginalised, including, for example, the poorest girls, children with disabilities, and the poorest households living in rural communities, could be missed.

Issues related to the shortcomings in attention to equity in the indicators were raised by both government and donor stakeholders. With respect to supporting the education of children with disabilities specifically, experts within the MoE felt that a more expansive approach was needed. Specifically, the provision of the additional school grant (DLI4, ) was intended to increase the number of Inclusive Education Resource Centres from 113 to 800. This would still only reach less than 10% of schools even if the target was achieved. It would mean that only a small percentage of teachers would receive training on inclusive education, and a minority of children with disabilities would be supported. It seems that requests from within the MoE for a more comprehensive approach to support children with disabilities had not been considered, as one MoE official noted:

Well, [the World Bank] brought the draft and we gave our ideas and suggestions on the draft, but … the final document came and what we had suggested is not included …. For example … one of the indicators is that the [Inclusive Education] Resource Centre must have 35 children with disabilities … they decreased it from 50 to 35 [children] … and the other [challenge] is they said that only two teachers will be trained in inclusive education issues … it is better than nothing but still not satisfactory.

Table 2. Result areas and disbursement linked indicators (Source: World Bank Citation2018).

In a related manner, some donor and government stakeholders, including a number of regional-level government officials, criticised the fact that the PforR approach did not take account of the priorities of the different regional states. One donor argued that the approach taken was one based on an ‘Ethiopian sense of equity’ which involved ‘doing the same in all regions’ rather than giving to those who needed the most support. Similarly, one regional-level stakeholder discussed how ‘priority at the regional level should be identified as they vary from region to region’. Although some of the indicators are focussed on specific regions – for example gender parity in the Afar, Somali and Benishangul Gumuz regions (ie ‘emerging less-developed regions) – more generally the programme was not viewed as able to be sufficiently flexible to take account of the different priorities across regions. As other authors have noted, political priorities have meant that the government has tended to focus on doing the same in each region rather than focussing attention on where it is needed most (Hagmann and Abbink Citation2011; Woldehanna and Araya Citation2019).

Overall, while many stakeholders suggested that the targeted focus on equity was one of the biggest achievements of this phase of GEQIP (Asgedom, Carvalho, and Rose Citation2021), there are concerns that this has not been sufficiently prioritised in the measurement of the results. As such, there is a concern whether the PforR approach will undermine GEQIP-E’s aim related to equity.

Ability to monitor results

A key concern raised by many donor and government stakeholders, including both federal and regional stakeholders, was the ability of the government to monitor progress and verify results given the unreliability of the data system. Issues discussed during the interviews included problems such as the limited availability of quality and timely data and information, the lack of official frameworks, the fragmented nature of data and limited coordination, the poor quality of data collected, and the limited use of data for planning and decision-making purposes, particularly at the local level.

Although improved data collection and analysis for planning and decision-making purposes is one of the key elements of the GEQIP-E programme, and improvement is identified as one of the results on which payment would be made (DLI7, ), one donor suggested that it would have been more appropriate to first strengthen the data system before implementing the PforR approach. The absence of a robust data system could have affected the selection of indicators, limiting them to data that are available, and so limiting the focus on GEQIP-E’s aims of improving learning outcomes across different dimensions of equity, as discussed above.

In addition, improving the accuracy of data could result in perverse outcomes such as the false reporting of data, a concern raised by one regional stakeholder. It is generally viewed that enrolment rates are inflated in the way they are currently recorded using administrative data, including because the census data on which the school-aged population is based is outdated (UNESCO Institute of Statistics Citation2017). Improving the accuracy of data as intended as part of GEQIP-E is likely to result in a lowering of reported enrolment rates, which will mean other targets could appear not to be met (even if progress is being made).

‘An outdated model’?

Some donors criticised the type of PforR that was being used, which was described as an ‘outdated model’ characterised by being very rigid and having very little flexibility: either the results are achieved and funds are released, or the results are not achieved and funds are not released. Given these concerns, a few donor and government stakeholders believed that a more flexible PforR approach should be adopted that could take account of the considerable diversity within the country and could respond to challenges as they emerged.

The limits of this rigid approach to PforR became apparent at the end of the first year of the programme, after several results were not achieved. Subsequently, the GEQIP-E programme underwent a restructuring process that involved a lighter-touch PforR approach that allowed more flexibility, including the scalability of all DLIs (see Gibbs et al. Citation2021). It is a reassuring sign that greater flexibility became apparent, even though this was only after considerable negotiations amongst donors. And whether this fully resolves the problems remains to be seen.

Summary

Together, these findings raise important questions as to whether the programme is focussed on the right results and how this might impact the implementation of the programme. Although a stated aim of the PforR approach is to shift the focus from inputs to outcomes, this is not fully reflected in the indicators. From the perspectives of some donor and government stakeholders interviewed, identifying and agreeing on results was a difficult and drawn-out process. Concerns emerge in relation to the equity focus of the GEQIP-E programme, including the fact that data are disaggregated across gender, but miss other important aspects, notably disability, which is a stated focus of GEQIP. The limited scope of some of the indicators raises the question of whether this may lead to perverse incentives, whereby those responsible for implementing the programme focus on what is more easily achievable (see also Clist Citation2016; Holzapfel and Janus Citation2015). The shortcomings of the data system, which limit the ability to monitor progress within the system, have also been raised as a cause for concern. Given that the PforR approach creates incentives for what is prioritised, these findings bring into doubt whether the Ethiopian education system was ready for the PforR approach, or if it would have been better to sequence the process by first ensuring the data system was fit for purpose.

Stakeholder preparedness for the introduction of PforR

A core objective of the PforR financing approach is to incentivise stakeholders to achieve results (Holland and Lee Citation2018). However, this depends on all stakeholders having sufficient information and knowledge of this new approach. A previous evaluation of a pilot results-based financing programme in Ethiopia noted difficulty in communicating the objectives to stakeholders through the education system (Cambridge Education Citation2015). To consider this in the context of the nationwide GEQIP-E programme, we turn to our third research question, namely how prepared stakeholders at different levels of the education system were for the introduction of PforR.

Local level of information and knowledge of PforR

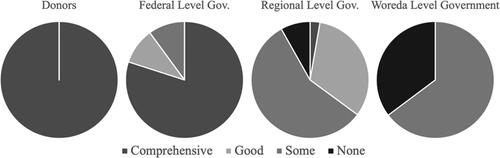

Stakeholders included in our interviews – especially those at the regional level – stressed the importance of ensuring that all stakeholders within the system were aware of the new PforR financing approach and what it entails. They emphasised that the success of GEQIP-E required sufficient communication and coordination amongst stakeholders at multiple levels of the system, as captured by one government official from the Somali Regional Education Bureau: ‘The challenge may be not having a common understanding. For instance, if there is difference in the feelings of donors, MoE and Regional Education Boards, then this will be a challenge’. However, as illustrated in , our analysis revealed that all donors and most federal government officials were aware of the PforR approach. However, there was a significant gap in knowledge of its existence amongst many regional and a majority of woreda officials. Given these officials are responsible for the implementation of the GEQIP-E interventions associated with the PforR approach, their limited knowledge of it may undermine success in achieving its targeted aims.Footnote3

Figure 2. Level of knowledge of PforR amongst stakeholders interviewed (compiled from analysis of interviews with donor and government stakeholders).

Drawing on the data from the interviews, we developed a classification of the level of knowledge that stakeholders in our interviews had of the GEQIP-E reforms. We identified four categories: ‘comprehensive’, ‘good’, ‘some’ and ‘none’ (). Those who had either ‘comprehensive’ or ‘good’ levels of knowledge were generally found at the federal or regional level. They usually understood the details and the potential benefits and challenges of this new approach to financing, albeit to varying degrees. Those who had ‘some’ level of knowledge about PforR financing were generally found at the regional or woreda level. They usually had heard of the programme but did not have details of what the approach entailed. For example, one regional stakeholder in Benishangul Gumuz explained that he had ‘no clear understanding, but he had heard that PforR means Programme for Result’, while another regional stakeholder in Amhara explained, ‘I informally heard about it. I heard that the next [phase of] GEQIP will be results-orientated’. ‘None’ referred to those who had not heard of the programme or any changes to the financing approach and included a minority of regional and woreda stakeholders.

Table 3. Level of information and knowledge amongst stakeholders regarding the shift to PforR.

An over-reliance on a cascade flow of information

The limited information that some stakeholders had about the PforR approach was largely due to an over-reliance on a cascade flow of information, whereby information at the federal level is expected to flow down to regions and then on to woredas. In this context, many regional government stakeholders indicated that information was communicated indirectly and in an informal manner. For example, one regional stakeholder in the Amhara region explained: ‘I informally heard about it. I heard that the next GEQIP will be result-oriented. The information has not been communicated very well in the region’.

Many regional-level stakeholders indicated that they first heard about this new approach while attending workshops for other issues, usually after the details of the GEQIP-E programme had been finalised. The communication of information was even less reliable at the woreda level, where stakeholders spoke of hearing rumours that a new type of financing would be introduced: ‘There is a rumour which says that the school grant is to be changed to [PforR], but I am not sure of that’. As other research in Ethiopia has demonstrated, the sequential chain of command through which strategies are implemented results in significant knowledge gaps at lower levels of the education system (Asgedom et al. Citation2019; Gibbs et al. Citation2021; Yorke, Rose, and Pankhurst Citation2021).

The fact that many stakeholders had limited information of what the programme entailed, while a minority of stakeholders had not even heard of this new approach, raises concerns for the implementation of this new approach and the achievement of the results.

A sustainable approach?

In addition to the limited information that many stakeholders, particularly at regional and woreda levels, had about this approach, some donors felt that the government did not fully appreciate the details of this new programme. For example, one donor suggested that some government officials believed that they could spend the money on whatever they wished:

… some senior people in the [MoE] … they were telling me: ‘Ok, Fine let [the donors] commit the money. We will commit to achieving these results … but once we collect the money, we will spend it on things we would like’.

However, another donor explained that while in principle the government could do what it wishes as long as it achieves the results, in practice the official documentation outlined a specific chain of results that the government would be required to follow. One donor suggested that those implementing the programme would focus on short-term gains rather than on long-term sustainability:

I think may be that trade-off between achieving target and building capacity. I think that the whole implementation has been driven by ticking boxes and identifying targets and I don’t think it necessarily balanced that with building capacity for the longer term.

Federal-level government officials shared similar views, questioning whether the results achieved would be long lasting: ‘It will work for a period of time, but I don’t know whether it will be long lasting or not … if a person is committed then the job will be done … so commitment is very important’. As such, even if results were achieved, it was questioned whether the results would be sustainable.

Given the range of identified challenges, concerns were raised – especially amongst regional- and woreda-level stakeholders – about what would happen if the results were not achieved, or were only partially achieved, and funds were not released. Government stakeholders discussed how achieving results was not straightforward and it would not be possible to ‘achieve results overnight’. Some regional and woreda stakeholders suggested that this would lead to a ‘financial crisis’ for schools. If this was to be the case, then the introduction of PforR financing would potentially undermine one of the very reasons for which GEQIP was originally devised: to secure the flow of funds into the system.

Summary

These findings suggest that stakeholders may not be adequately prepared for the introduction of this new approach, especially those at the regional and woreda level. The significant knowledge gap, especially amongst those responsible for the implementation of the programme locally, emerged as a significant challenge that would likely have an impact the achievement of results. Our findings further suggest that the ability of the PforR programme to incentivise stakeholders to achieve results may therefore be limited, especially due to the overreliance on the cascade flow of information in the system. Given this gap, we are thus left with the question as to what will happen if results are not achieved, and funds are not released, with our findings suggesting that it may be school-level stakeholders who are most likely to be adversely affected. Given these challenges, there is a concern that the PforR approach in the GEQIP-E programme could undermine the predictability of aid.

Conclusion

Our analysis has explored the design and uptake of PforR financing at scale within the education system in Ethiopia from the perspectives of 72 donor and government stakeholders. The domains of power approach (Hickey and Hossain Citation2019) provided a useful framework for conceptualising the range of stakeholders at different levels of the education system (international, federal, regional and woreda) and their role in relation to the design and uptake of the GEQIP-E reforms. An important contribution of our study has been the inclusion of the perspectives of these different stakeholders in relation to the uptake of this new financing approach.

In considering what led to the introduction of PforR financing, we find that the process involved a range of government and donor stakeholders who had varying levels of influence and different motivations for introducing this new approach. The need to demonstrate results was identified as the most important motivation underpinning its introduction, which was viewed as being closely aligned with the government’s overall development strategy. We also find that without the support of the MoF, viewed as the most influential government stakeholder, it is likely that this new approach would not have been introduced.

In terms of the results selected, we find that their identification was seen as a difficult and drawn-out process. The results selected do not adequately reflect the transformative aims of the GEQIP-E programme with respect to both learning and equity. Our findings also indicate that stakeholders at different levels of the system were not prepared for the introduction of PforR and had limited knowledge and information about this approach. Taken together, our findings suggest that the ability of the PforR programme to strengthen the education system and improve learning may be limited. Ultimately, our findings support a recent evaluation which concludes that results-based financing cannot be considered a magic bullet (Dom et al. Citation2021).

Our findings also raise the important issue of ensuring that stakeholders who are responsible for implementing the programme have sufficient information and knowledge about this new approach. Therefore, we suggest that greater consideration and planning should centre on the preconditions needed to ensure that the results can be achieved, including reliable data systems and the adequate flow of information within the system, particularly to lower levels responsible for its implementation.

As our study took place in the initial year of the GEQIP-E programme, we were unable to provide information on the implementation of the programme. Further evidence of the implementation and impact of this programme from the perspectives of key stakeholders would therefore be worthwhile.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants who gave their valuable time to participate in this research. We also thank the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Louise Yorke

Louise Yorke is Senior Research Associate at the Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre in the Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge as part of the RISE Ethiopia research project. Her PhD, from the School of Social Work and Social Policy, Trinity College Dublin, focussed on female rural–urban migration for secondary education in southern Ethiopia. Her current research interests include education systems analysis, the politics of education, equity in education and gender equality.

Amare Asegdom

Amare Asgedom is a Professor of education at Addis Ababa University. He earned his PhD in education from the School of Education and Lifelong Learning at the University of East Anglia in 2007. He is currently a member of the RISE Ethiopia research team. He served as a Team Leader and Deputy Project Head of the Ethiopian Education Roadmap (2016–2030). His research interest is in quality of education, focussing on curriculum, teaching, and learning and higher education. Previously he served as Director of the Institute of Educational Research, Addis Ababa University; Director of MERA (Monitoring, Evaluation, Research and Assessment) of the USAID/IQPEP Project; and Chairperson of the Department of Curriculum and Instruction at Addis Ababa University. He has over 65 publications – journal articles, chapters in books and proceedings, and books. He served as Editor-in-Chief and Editor of several peer-reviewed journals including the Ethiopian Journal of Higher Education: The Ethiopian Journal of Education and IER-FLAMBEAU.

Belay Hagos Hailu

Belay Hagos Hailu is Associate Professor of education. He received his PhD in special needs education from Addis Ababa University in 2012. He is currently the Director of the Institute of Educational Research at Addis Ababa University and Team Leader on the RISE Ethiopia team. His research areas of interest are educational assessment, systems of education and early childhood education. He was a research team member of the National Education Development Roadmap of Ethiopia (for 2016–2030); a research team member of the study on Early Learning Partnership in Ethiopia commissioned by the World Bank; and a team member of the research on Accelerated School Readiness (ASR) led by the American Institute for Research (commissioned by UNICEF). He is also a research team member of the thematic research on Teacher Professional Identity in Ethiopia supported by Addis Ababa University.

Pauline Rose

Pauline Rose is a Professor of international education at the University of Cambridge, where she is Director of the Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre in the Faculty of Education. Prior to joining Cambridge, She was Director of UNESCO’s Education for All Global Monitoring Report. She is the author of numerous publications on issues that examine educational policy and practice, including in relation to inequality, financing and governance, and the role of international aid. She has worked on large collaborative research programmes with teams in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia examining these issues. In 2022, she was awarded an OBE for services to girls’ education internationally.

Notes

1 https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/program-for-results-financing#2 [accessed 17th December 2021]

2 Some of the interventions are rolled out in a phased manner: Phase 1 covers 5% of woredas (2000 schools), Phase 2 was intended to cover another 25% of woredas (about 9000 schools) and Phase 3 would cover 20% of additional woredas (about 7000 schools).

3 It is important to note that our interviews were carried out during the first year of the implementation of the GEQIP-E programme. As such, while we did not expect all stakeholders to have comprehensive knowledge of the PforR financing approach, we did expect that stakeholders would be at least aware of it.

Bibliography

- Asgedom, A., B. Hagos, G. Lemma, P. Rose, T. Teferra, D. Wole, and L. Yorke. 2019. “Whose Influence and Whose Priorities? Insights from Government and Donor Stakeholders on the Design of the Ethiopian General Education Quality Improvement for Equity (GEQIP-E) Programme.” RISE Insight Series. doi:https://doi.org/10.35489/BSG-RISE-RI_2019/012.

- Asgedom, A., S. Carvalho, and P. Rose. 2021. “Negotiating Equity: Examining Priorities, Ownership, and Politics Shaping Ethiopia’s Large-Scale Education Reforms for Equitable Learning.” RISE Working Paper Series. 21/067. doi:https://doi.org/10.35489/BSG-RISE-WP_2021/067.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Cambridge Education. 2015. Evaluation of the Pilot Project of Results-Based Aid in the Education Sector in Ethiopia. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Education. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/576168/Eval-pilot-project-result-based-aid-Education-Ethiopia.pdf.

- Clapham, C. 2006. “Ethiopian Development: The Politics of Emulation.” Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 44 (1): 137–150. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14662040600624536.

- Clapham, C. 2018. “The Ethiopian Developmental State.” Third World Quarterly 39 (6): 1151–1165. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2017.1328982.

- Clist, P. 2016. “Payment by Results in Development Aid: All That Glitters Is Not Gold.” The World Bank Research Observer 31 (2): 290–319. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lkw005.

- Clist, P., and A. Verschoor. 2014. The Conceptual Basis of Payment by Results. London: DFID. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a089bb40f0b64974000230/61214-The_Conceptual_Basis_of_Payment_by_Results_FinalReport_P1.pdf.

- Cormier, B. 2016. “Empowered Borrowers? Tracking the World Bank’s Program-for-Results.” Third World Quarterly 37 (2): 209–226. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.1108828.

- Dom, C., A. Fraser, J. Patch, and J. Holden. 2021. Results-Based Financing in the Education Sector: Country-Level Analysis. Final synthesis report. Submitted to the REACH Program at the World Bank by Mokoro Ltd. Report Number 166157.

- Fantini, E., and L. Puddu. 2016. “Ethiopia and International Aid: Development between High Modernism and Exceptional Measures.” In Tobias Hagmann & Filip Reyntjens (Eds.) Aid and Authoritarianism in Africa: Development without Democracy, 91–118. Zed Books. London.doi:https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350218369.ch-004.

- Fourie, E. 2011. Ethiopia and the Search for Alternative Exemplars of Development. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto. https://www.open.ac.uk/socialsciences/bisa-africa/files/bisa-2011-fourie.pdf

- Furtado, X., and J. Smith. 2007. “Ethiopia: Aid, Ownership, and Sovereignty.” GEG Working Paper. No. 2007/28. https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/196291/1/GEG-WP-028.pdf

- Gelb, A., and N. Hashmi. 2014. “The Anatomy of Program-for-Results: An Approach to Results-Based Aid.” Center for Global Development Working Paper, (374). doi:https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2466657.

- Gibbs, E., C. Jones, J. Atkinson, I. Attfield, R. Bronwin, R. Hinton, A. Potter, and L. Savage. 2021. “Scaling and ‘Systems Thinking’ in Education: Reflections from UK Aid Professionals.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 51 (1): 137–156. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2020.1784552.

- Global Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation [GPEDC]. 2016. Nairobi Outcome Document. Global Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation. Nairobi, Kenya. https://www.effectivecooperation.org/system/files/2020-05/Nairobi-Outcome-Document-English.pdf

- Hagmann, T., and J. Abbink. 2011. “Twenty Years of Revolutionary Democratic Ethiopia, 1991 to 2011.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 5 (4): 579–595. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2011.642515.

- Hickey, S., and N. Hossain. 2019. Politics of Education in Developing Countries: From Schooling to Learning. Oxford University Press. Oxford, United Kingdom. https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/37376/9780198835684.pdf?sequence=1

- Hoddinot, J., P. Iyer, R. Sabates, and T. Woldehanna. 2019. “Evaluating Large-Scale Education Reforms in Ethiopia.” RISE Working Paper Series. 19/034. doi:https://doi.org/10.35489/BSG-RISE-WP_2019/034.

- Holland, P. A., and J. D. Lee. 2018. “Results Based Financing in Education: Financing Results to Strengthen Systems.” Washington, DC: World Bank Group. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/26268/113265-REVISED-RBF-Approach-Final-Digital.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Holzapfel, S., and H. Janus. 2015. Improving Education Outcomes by Linking Payments to Results-An Assessment of Disbursement-Linked Indicators in Five Results-Based Approaches. Bonn: German Development Institute. https://www.die-gdi.de/uploads/media/DP_2.2015.pdf

- lapham, C. 2019. “The Political Economy of Ethiopia from the Imperial Period to the Present.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Ethiopian Economy, edited by F. Cheru, C. Cramer, and A. Oqubay. pp. 33–47, Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198814986.013.6.

- Iyer, P., C. Rolleston, P. Rose, and T. Woldehanna. 2020. “A Rising Tide of Access: What Consequences for Equitable Learning in Ethiopia?” Oxford Review of Education 46 (5): 601–618. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2020.1741343.

- Ministry of Education [MoE]. 2015. “Education Sector Development Programme V (ESDP V).” 2008-2012 E.C., 2015/16-2019/20 G.C. Ministry of Education. Addis Ababa. https://planipolis.iiep.unesco.org/en/2015/education-sector-development-programme-v-esdp-v-2008-2012-ec-201516-201920-gc-programme-action

- Ministry of Education [MoE]. 2020. Education Statistics Annual Abstract: September 2019-March 2020. Addis Ababa: Ministry of Education.

- Rekiso, Z. S. 2019. “Education and Economic Development in Ethiopia, 1991–2017.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Ethiopian Economy, edited by F. Cheru, C. Cramer, and A. Oqubay. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198814986.013.23

- UNESCO. 2014. Teaching and Learning: Achieving Quality for All; EFA Global Monitoring Report, 2013–2014. Global Education Monitoring Report. UNESCO, Paris. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000225660

- UNESCO. 2018. “Walk before You Run: The Challenges of Results-Based Payments in Aid to Education.” UNESCO policy paper 33. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000261149

- UNESCO Institute of Statistics. 2017. “Estimation of the Numbers and Rates of out-of-School Children and Adolescents Using Administrative and Household Survey Data.” UNESCO Institute for Statistics Information Paper N.35. UNESCO: Canada. http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/ip35-estimation-numbers-rates-out-of-school-children-adolescents-household-2017-en.pdf

- Woldehanna, T., and M. W. Araya. 2019. “Poverty and Inequality in Ethiopia.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Ethiopian Economy, edited by F. Cheru, C. Cramer, and A. Oqubay. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198814986.013.17

- Woldehanna, T., and A. T. Gebremedhin. 2016. “Learning Outcomes of Children Aged 12 in Ethiopia: A Comparison of Two Cohorts.” Young Lives Working Paper 152, Young Lives, Oxford. https://www.younglives.org.uk/sites/www.younglives.org.uk/files/YL-WP152-Learning%20outcomes%20in%20Ethiopia.pdf

- World Bank. 2015a. “Program for Results: Two-Year Review.” Washington, DC: World Bank Group. https://www-wds.worldbank.org/external/default/WDSContentServer/WDSP/IB/2015/03/19/000477144_20150319141327/Rendered/PDF/951230BR0R2015020Box385454B00OUO090.pdf

- World Bank. 2015b. “The Rise of Results-Based Financing in Education.” Education Global Practice Brief. Washington, DC: World Bank Group. http://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/Brief/Education/RBF_ResultsBasedFinancing_v9_web.pdf

- World Bank. 2017. “Concept Note: General Education Quality Improvement Program for Equity (GEQIP-E).” Washington, DC: World Bank. http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/580961492110426813/pdf/Ethiopia-Education-PforR-PID-20170405.pdf

- World Bank. 2018. “General Education Quality Improvement Program for Equity (GEQIP-E): Program Appraisal Document.” Washington, DC: The World Bank. http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/128401513911659858/pdf/ETHIOPIA-EDUC-PAD-11302017.pdf

- Yorke, L., P. Rose, and A. Pankhurst. 2021. “The Influence of Politics on Girls’ Education in Ethiopia.” In Rose, P., Arnot, M., Jeffrey, R. & Singal, N. Reforming Education and Challenging Inequalities in Southern Contexts. Research and Policy in International Development, 98–119. Routeldege. London and New Yorke. doi:https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.64900.